- Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

Analyzing the myriad ways in which structural racism systemically generates health inequities requires engaging with the profound challenges of conceptualizing, operationalizing, and analyzing the very data deployed—i. e., racialized categories—to document racialized health inequities. This essay, written in the aftermath of the January 6, 2021 vigilante anti-democratic white supremacist assault on the US Capitol, calls attention to the two-edged sword of data at play, reflecting long histories of support for and opposition to white supremacy and scientific racism. As illustrated by both past and present examples, including COVID-19, at issue are both the non-use (Edge #1) and problematic use (Edge #2) of data on racialized groups. Recognizing that structural problems require structural solutions, in this essay I propose a new two-part institutional mandate regarding the reporting and analysis of publicly-funded work involving racialized groups and health data and documentation as to why the proposed mandates are feasible. Proposal/part 1 is to implement enforceable requirements that all US health data sets and research projects supported by government funds must explicitly explain and justify their conceptualization of racialized groups and the metrics used to categorize them. Proposal/part 2 is that any individual-level health data by membership in racialized groups must also be analyzed in relation to relevant data about racialized societal inequities. A new opportunity arises as US government agencies re-engage with their work, out of the shadow of white grievance politics cast by the Trump Administration, to move forward with this structural proposal to aid the work for health equity.

Introduction

Analyzing the myriad ways in which structural racism systemically generates health inequities (1–7)—that is, differences in health status across social groups that are unjust, avoidable, and in principle preventable (8–10)—requires scientific theory, hypotheses, data, and methods. This is standard science (11–13). What could be more obvious?

But when it comes to racialized health inequities, what appears obvious is rarely simple. Any attempt to analyze empirically—and provide evidence to alter—the causal processes by which structural racism produces health inequities, including by shaping discriminatory practices and policies of institutions and actions of individuals—must engage with the profound challenges of conceptualizing, operationalizing, and analyzing the very data deployed—i.e., racialized categories—to document racialized health inequities (1, 14–18).

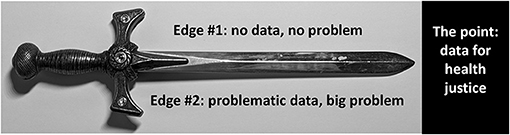

In this brief perspective, I accordingly call attention to the two-edged sword of data when it comes to racial justice and health (Figure 1). At issue are both the non-use (Edge #1) and problematic use (Edge #2) of data on racialized groups. To avoid being cut by either edge, my proposal – informed by the ecosocial theory of disease distribution and its constructs of embodying injustice along with accountability and agency for documenting and analyzing this causal process (1, 11, 17–20)—is to recognize that structural problems require structural solutions, including for racialized data.

Figure 1. Structural injustice and the two-edged sword of data: (1) Edge #1: preventing documentation that injustice exists, (2) Edge #2: using problematic data in harmful ways that further entrench justice, vs. (3) looking instead to the point: data for health justice. [Note: the author created the figure and took the photo used; NO copyright issues are involved].

Underscoring the urgency of these issues is the context in which I have prepared this essay. I began writing on January 8, 2021, 2 days after the flagrant violent assault on the US Capitol led by vigilante anti-democratic white supremacist, white nationalist (including white Christian nationalist), alt-right, and neo-Nazi groups, who sought to thwart a fair election and the peaceful transition of Presidential power (21–24). Unifying these groups is a belief in essentialist notion of “race,” a fear what they call “demographic replacement” (i.e., becoming white “minorities” in a multi-ethnic/racial society), and the politics of white grievance (whereby any attempts to name or limit white privilege are deemed anti-white racism) (25–30). More mainstream enablers have been seeking to cement conservative white minority rule, using the strategies of voter suppression and gerrymandering, while preserving the veneer of democratic governance (31–34). Also germane are wealthy supporters of an extreme “free market” political agenda and philosophy that holds government exists solely to defend private property—and jointly oppose government regulations (including to protect the public's health, e.g., protect against pollution, climate change, and environmental racism) and taxes to support government programs (especially if to rectify racial and economic injustice) (2, 33–38).

In such a context, how can an anti-racist science for health equity employ data on racialized groups? This is not a new question (15, 16, 30, 39–45)—indeed, in the US, these issues have been posed and debated in medical and public health literature for over 300 years (16, 39–45).

Data Never Speak for Themselves

A crucial first point is that, contrary to its etymology, “data” is never a “given” (11, 16). Despite being the past participle of the Latin verb “dare,” i.e., “to give” (46), data instead are always produced by people, out of what they observe, fail to see, or suppress in the world in which they live (11–13, 47, 48). A corollary, in the case of people, is that a hallmark of privilege is who and what one can afford to ignore (49, 50). Translated to the realm of science, this means it is imperative to ask: who produces and controls the data? To what end? And engaging with what history? (11–13, 47–50).

Within the US, histories of the contested production and use of racialized data extend back to its origins as slave republic and settler-colonial nation (40, 43–45, 51–53). In the eighteenth century CE, racialized data were primarily produced and used to entrench injustice by the enfranchised minority of white men with property (52–54). These data characterized who was enslaved vs. free, and which Indigenous tribes and nations were vs. were not under colonial and then federal jurisdiction (51–54). Indeed, these data underpinned the first-ever decennial census in 1790, the first-ever census to be constitutionally mandated by a government anywhere (51–53), and which was designed to apportion political representation, allocate resources, and power, deeply marked by infamous 3/5 compromise that allowed slave-holding states partial counts of their enslaved but disenfranchised populations (52, 53). In this context, dominant white physicians held that racialized differences in health status, including the poorer health of enslaved persons and decimation of Indigenous peoples by colonial diseases, reflected the natural order of the world (6, 39, 40, 43–45, 55).

In the nineteenth century CE, the rise of the abolition movement, both Black- and white-led (56, 57), triggered a shift in use of racialized data (40, 43, 45). Thus, these abolitionists—including the first generation of credentialed African American physicians—began using racialized data, including on health status, to challenge the abominations of slavery, while supporters of slavery—including many physicians and scientists who embraced scientific racism—sought to use these same data to uphold the doctrine of white supremacy (40, 43, 45, 55–62). Then as now the debates turned on whether the racialized categories were constructed by people, to justify injustice, vs. so-called “natural” categories, reflecting innate or a priori differences; for health, the crux of the argument was whether racism vs. “race” accounted for observed differences in health status across racialized groups (30, 40, 43–45, 58–62).

Then as now key debates also concerned what additional data were required, beyond “race,” to contextualize the racialized health data. For example, Dr. James McCune Smith (1813–1865), the first credentialed Black American physician in the US (who received his medical degree in Scotland since no US medical school would admit Black students), in 1859 famously compared the similarly high prevalence of rickets among the enslaved Black population in the US South to destitute peasants in Ireland (45, 59, 60). By contrast, Dr. Samuel Cartwright (1793–1863), a prolific white pro-slavery physician, authored tract after tract about the biological “peculiarities” of Black persons that rendered them fit only to be slaves, without ever including any economic data (43–45, 62). Exemplifying the political salience of scientific racism was the inclusion of an essay by Cartwright (63) in the first print edition of the infamous US Supreme Court 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared that Black Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect …” (64–66).

In early the twentieth century CE, the same sorts of schisms existed, updated in relation to challenging vs. upholding Jim Crow, a multifaceted regime of legalized racial segregation, upheld by terror, and imposed in the 1880s, fueled by white Southern backlash to losing the Civil War and their enslaved workforce, plus opposition to civil rights gains won during Reconstruction (67–69). Kindred debates occurred over eugenics, with the latter strongly upheld by the US Supreme Court and leading scientists, University presidents, and more, who ushered in the passage of eugenic sterilization laws in 32 US states and also the eugenic-fostered federal Immigration Restriction Acts of 1924 and 1927 (30, 70–74).

Subsequently, during the 1950s and 1960s, racial/ethnic data featured prominently in fights for vs. against civil rights and for vs. against overturning the eugenic-era immigration restrictions (14, 30, 70–76). In the wake of major federal legislation passed in 1964 and 1965 which afforded new protection of civil rights and expanded immigration, official government racial/ethnic data was widely used to provide evidence of injustice, as opposed to justifying it (14, 51, 77–79). However, the successful civil rights strategy of using racialized data to demonstrate the existence of—and support alleviation of—what was termed “statistical discrimination” (or “disparate impact”) not surprisingly sparked conservative backlash, leading to two types of resistance (26, 32–34, 78–81).

• One was to try to suppress use of racial/ethnic data, thereby removing any evidence of harm requiring redress, as per the unsuccessful campaign of Proposition 54 in California in 2003 (82, 83). Deceptively dubbed the “Racial Privacy Initiative,” it sought to prohibit the state from recording or using any racial or ethnic data—and was defeated in part due to public health concerns about harms caused by concealment of data (83–87).

• The other approach was to require evidence of motivation, not just disparate impact (78, 79). The latest example is the outgoing Trump Administration's bid to require the Department of Justice to “narrowly enforce” Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, i.e., only “in cases where it could prove intentional discrimination, but no longer in instances where a policy or practice at issue had a “disparate impact” on minority or other groups” (88).

Concomitantly, groups concerned about racial justice have repeatedly expressed their concerns about how racialized data have repeatedly been deployed by those with power to stereotype and victim-blame, blaming allegedly “innate” biology and “chosen” cultures for health woes, starting with infant mortality and extending across the lifecourse, and newly including COVID-19 (1–7, 40, 42, 44, 89–92). The tension is real: both use and non-use of racialized data can wreak woes.

The Two-Edged Sword of Data in Action: the Case of COVID-19 in the us

The problem of racialized health inequities and the two-edged sword of data is not unique to the US. Similar issues arise in other countries home to social inequities involving racialized groups, including but not limited to France, Portugal, Brazil, Mexico, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada—all countries whose histories are in differing ways bound up with legacies of colonialism, settler-colonialism, and slavery (15, 93–95). That said, because I am a US person, I offer an example of the two-edged sword in action in my country, in relation to a current calamity: COVID-19.

It is way too early to know how reporting of COVID-19 data by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), including in relation to racialized groups, has been affected by political interference by the Trump administration, given emerging evidence of politically-motivated data suppression and distortion (96–99). That said, both edges of the sword were—and are still—in full view.

Early on in the pandemic, government data on COVID-19 data by racialized group was missing in action (100–103), despite federal health agencies routinely including racial/ethnic data for just about every disease and mortality outcome (16, 103–106). Instead, tallies and accounts of the burden of COVID-19 among racialized groups came mainly from investigative journalism and web-based data trackers created on the fly (107–116). In early June, propelled by the advocacy of racial justice activists who wanted these data to raise awareness and obtain resources for prevention for their communities, new Congressional legislation mandated the inclusion and reporting of COVID-19 data by race/ethnicity, to be fully implemented by no later than August 1, 2020 (112, 117, 118). This requirement, however, had no teeth: my team documented that between August 28 and September 16, 2020 fully 43% of the new COVID-19 cases added to the CDC roster were still missing racial/ethnic data (119). Welcome to Edge #1 of the sword.

Edge #2 cut when CDC reported what limited data it had stratified by race/ethnicity. Their focus initially was on counts (rather than rates) and concerned differences in the racial/ethnic composition of COVID-19 deaths vs. the total population (120). At the outset, the data for the deaths were on one website, and the data for the total population were on another, making it difficult to discern if the proportions differed (120). Worse, closer inspection of these data revealed a curious finding: contrary to reports coming from the field, the CDC's data in May 2020 indicated that white non-Hispanics were overrepresented, and Black Americans underrepresented, among COVID-19 deaths. Several of us worked to unravel this puzzle, and we soon determined the CDC had committed a classic Type III error: right answer to the wrong question (121). In brief, the CDC weighted the denominators for the US counties by the percent of total COVID-19 deaths occurring in that county within the state (120). Given who was hardest hit by COVID-19, the net effect was to deflate the denominators for the white non-Hispanic population and inflate the denominators for the other populations of color, thus inflating risk for the former and deflating risk for the latter (121). Why did the CDC do this? The stated reason was that they were concerned that the racial/ethnic composition of the places initially hit hard by COVID-19, especially NYC, differed from that of areas hit less hard—and their weighting procedure sought to “correct” this problem (120).

But: to ask and answer the question: how does racial/ethnic risk for COVID-19 mortality vary apart from how racial segregation affects who lives where is to ask and answer the entirely wrong question. By treating place and the lived experiences and impacts of residential segregation as nuisance factors, to be “corrected” for by weighting, the CDC reached the entirely wrong conclusion (121). It will be a task for future historians to establish the decisions, and likely politics, influencing the CDC's approach to data presentation on COVID-19 and racialized groups.

Structural Racism, Data Needs, and Data Governance: Structural Solutions to Structural Problems

What then about the point of the sword: data for health equity? My structural suggestion: a two-part proposal to up the ante and create institutional mandates regarding publicly-supported work with racialized health data—whether public health monitoring, grant applications, or publications. The proposed steps are directly informed by ecosocial theory's emphasis on being explicit about agency and accountability at multiple levels, including both institutional and individual (17–20).

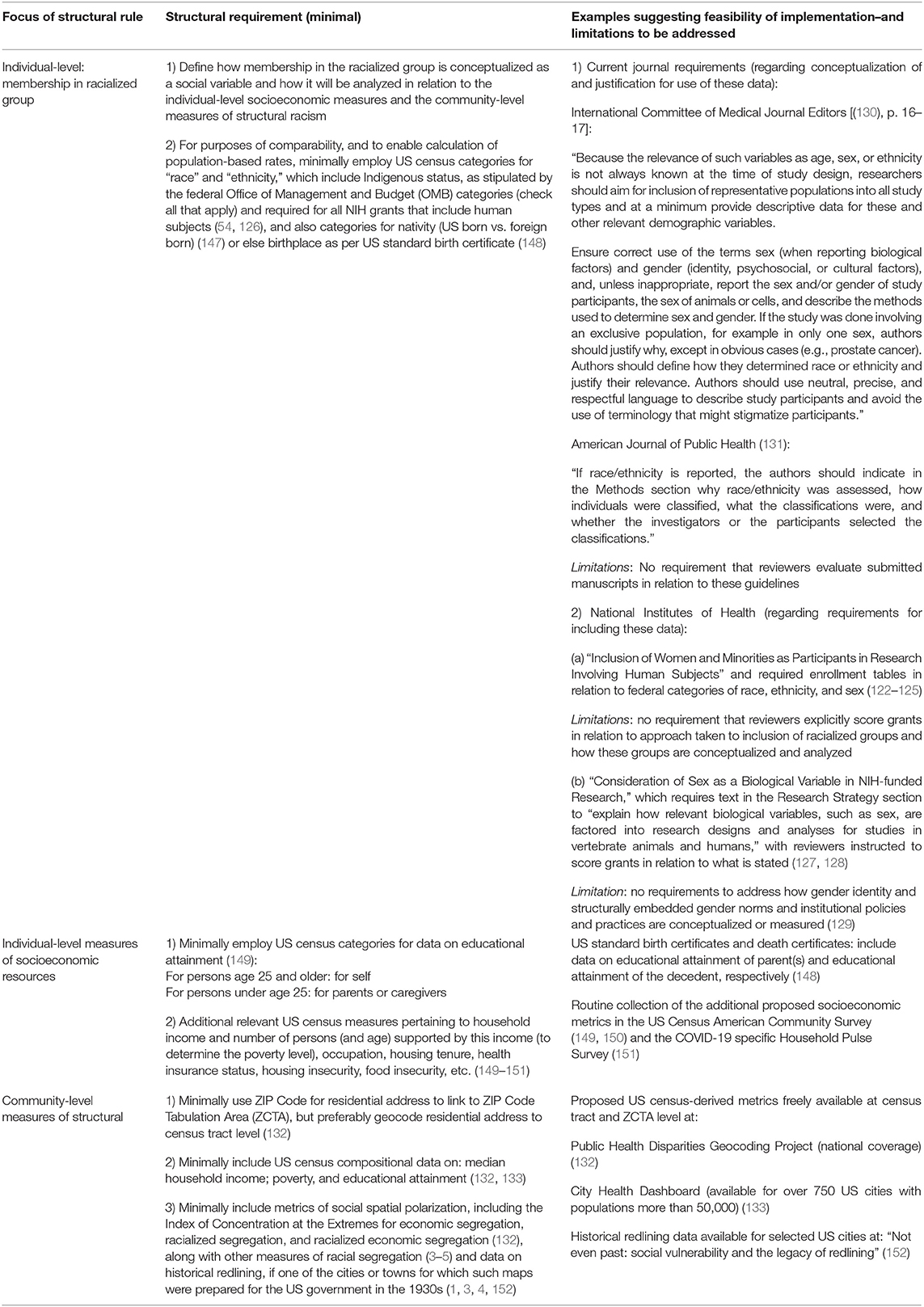

Proposal/part 1 is to implement enforceable requirements that all US health data sets and research projects supported by government funds must explicitly explain and justify their conceptualization of racialized groups and the metrics used to categorize them. As shown in Table 1, there is precedent, admittedly weak, but a basis on which to build. Thus, since 1994 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has required—with little enforcement—that grants report on and justify the number of “women and minorities” included, with “minorities” delimited using the US Office of Management and Budget categories (122–126). Moreover, since 2014, the new NIH policy on “Sex as a Biological Variable” (SABV) requires that reviewers rate all NIH grants' explanation of their approach to including “sex” as biological variable (127, 128)—albeit with no analogous requirements about how gender is conceptualized and analyzed (129). Numerous leading journals likewise proffer suggested—not mandatory—author guidelines regarding the use and interpretation of data on racialized groups (130, 131), albeit without analogous explicit instructions for reviewers (see Table 1). Hence, while none of these current institutional measures are sufficient, they do provide precedent for implementing structural steps to ensure that health agencies, organizations, and researchers must explicitly justify their conceptualization and analysis of racialized health data, and face consequences for not doing so.

Table 1. Structural solutions to the problems of structural racism and the two-edged sword of data so that it can point to health justice: proposed minimal data requirements for any health agencies, data systems, grant recipients, or journals receiving government support.

But inclusion and reporting of racialized health data, as such, is only a first step. Proposal/part 2 is that any individual-level health data by membership in racialized groups must also be analyzed in relation to relevant data about racialized societal inequities. As suggested in Table 1, this minimally means including both diverse metrics for socioeconomic position (at the individual- and community- levels) and exposure to structural racism (1–7, 18, 132–135). The latter can include explicit rule-based policies (e.g., involving voter suppression, or denial of Social Security benefits to domestic workers and agricultural workers) and also area-based or institutional measures that reflect racialized disparate impacts but not the rules per se (e.g., measures of racialized economic residential or occupational segregation, or racialized gaps in socioeconomic resources, incarceration rates, political representation, etc.) (1, 3, 135). Suggesting such steps are feasible, even in the midst of a fast-moving fearsome pandemic, scientific studies and data dashboards have generated striking evidence of the societal structuring of COVID-19 risks of exposure, illness, and death, using diverse metrics of residential segregation and racialized inequities in income, sick pay, and crowded housing (132, 136–143).

Granted, this two-part proposal for data justice is only one small step. Also needed is equity-oriented work on data governance, i.e., who has input into making the decisions about which data are required, informed by the tandem expertise of health equity researchers and other members of the communities whose data are at stake, affording the expertise of lived experience (2, 6, 47, 91, 92). Bringing a structural perspective to the data needs for data justice provides a start to the work at hand. Justifying implementation, continuing with the status quo and the harms produced is not acceptable.

Final Reflections: Reckoning With Structural Racism and Data for Health Justice

On January 7, 2021, the day after the vigilante white supremacist anti-democratic assault on the US Capitol, the University College London (UCL) notably issued its first-ever institutional apology for its critical role in legitimizing the rise of eugenics and the horrors it has unleashed world-wide (144, 145). As prelude, the UCL last year stripped their buildings of the names of Francis Galton (1822–1911), who coined the term “eugenics,” and also his seminal field-building statistical disciples Karl Pearson (1857–1936) and Ronald Fisher (189–1962), who were, respectively, the first and second Professor of Eugenics at UCL (145, 146). The new apology minces no words, with the first two paragraphs stating (144):

UCL acknowledges with deep regret that it played a fundamental role in the development, propagation and legitimization of eugenics. This dangerous ideology cemented the spurious idea that varieties of human life could be assigned different value. It provided justification for some of the most appalling crimes in human history: genocide, forced euthanasia, colonialism and other forms of mass murder and oppression based on racial and ableist hierarchy.

The legacies and consequences of eugenics still cause direct harm through the racism, antisemitism, ableism and other harmful stereotyping that they feed. These continue to impact on people's lives directly, driving discrimination and denying opportunity, access and representation.

As this statement attests, the wounds cut by the two-edged sword of wrongly conceptualized and wrongly employed data on racialized groups not only have not healed—they continue to be cut anew.

A new opportunity arises as US government agencies re-engage with their work, out of the shadow of white grievance politics cast by the Trump Administration. It is time, long past time, to delineate new structural requirements for publicly-funded work using racialized health data, so that the point is clear: to expose the harmful impacts of structural racism on health and assess the beneficial impacts of anti-racist policies.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor Award to NK.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Krieger N. Measures of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and gender binarism for health equity research: from structural injustice to embodied harm-an ecosocial analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. (2020) 41:37–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094017

2. Krieger N. ENOUGH: COVID-19, structural racism, police brutality, plutocracy, climate change-and time for health justice, democratic governance, and an equitable, sustainable future. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1620–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305886

3. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works - racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. (2020) 384:768–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396

4. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. (2017) 389:1453–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

5. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. (2019) 40:105–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

6. Greenwood M, De Leeuw S, Lindsay NM. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples' Health. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press (2018).

7. Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. (2011) 8:115–32. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130

8. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int. (1991) 6:217–28. doi: 10.1093/heapro/6.3.217

9. Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57:254–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254

10. World Health Organization. Equity. Available online at: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

11. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People's Health: Theory and Context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2011).

13. Ziman J. Real Science: What it Is, and What it Means. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press (2000).

14. Simon P. The measurement of racial discrimination: the policy use of statistics. Int Soc Sci J. (2005) 57:9–25. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-8701.2005.00528.x

15. Simon P, Piché V, Gagnon A editors. Social Statistics and Ethnic Diversity: Cross-National Perspectives in Classifications and Identity Politics. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2015).

16. Krieger N. The making of public health data: paradigms, politics, and policy. J Public Health Policy. (1992) 13:412–27. doi: 10.2307/3342531

17. Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. (1999) 29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q

18. Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:936–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544

19. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. (1994) 39:887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-X

20. Krieger N. Got theory? On the 21st c. CE rise of explicit use of epidemiologic theories of disease distribution: a review and ecosocial analysis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. (2014) 1:45–56. doi: 10.1007/s40471-013-0001-1

21. Borger J. Insurrection: the day white supremacist terror came to the us capitol. The Guardian (2021). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/09/us-capitol-insurrection-white-supremacist-terror (accessed January 18, 2021).

22. Beckett L. From charlottesville to the capitol: how rightwing impunity fueled the pro-trump mob. The Guardian (2021). Available online athttps://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/07/capitol-mob-attack-rightwing-rallies-trump (accessed January 18, 2021).

23. Quito A. Decoding the pro-trump insurrectionist flags and banners. Quartz (2021). Available online at: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/decoding-the-pro-trump-insurrectionist-flags-and-banners/ar-BB1cyVFe (accessed January 18, 2021).

24. Kirkpatrick DD, McIntire M, Triebert C. Before the capitol riot, calls for cash and talk of revolution. New York Times (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/16/us/capitol-riot-funding.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

25. Stern A. Proud Boys and the White Ethnostate: How the Alt-Right is Warping the American Imagination. Boston, MA: Beacon Press (2019).

26. Berlet C editors. Trumping Democracy: From Reagan to the Alt-Right. London: Routledge (2019). doi: 10.4324/9781315438412

27. Whitehead AL, Perry SL. Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2020) doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190057886.001.0001

28. Dies E, Graham R. How white evangelical christians fused with trump extremism. New York Times (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/us/how-white-evangelical-christians-fused-with-trump-extremism.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

29. Fernandes D, Moore D. Historians and academic warn that while the capitol riot may be unprecedented, white extremist groups are growing. Boston Globe (2021). Available online at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/09/metro/historians-academics-warn-that-while-capitol-riot-may-be-unprecedented-white-extremist-groups-are-growing/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

30. Rattansi A. Racism: A Very Short Introduction. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2020). doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780198834793.001.0001

31. Snyder T. The American abyss: a historian of fascism and political atrocity on Trump, the mob and what comes next. New York Times Magazine (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/magazine/trump-coup.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

32. Anderson C. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying Our Democracy. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing (2018).

33. Mayer J. Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. New York, NY: Doubleday (2016).

34. Hertel-Fernandez A. State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Businesses, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States–and the Nation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2018).

35. Sorkin AR, Karaian J, de la Merced MJ, Hirsch L, Livni E. What about the enablers? business is about accountability. New York Times (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/business/dealbook/capitol-mob-enablers.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

36. Collins C, Ocampo O. Trump and his many billionaire enablers. Inequality.org (2021). Available online at: https://inequality.org/great-divide/trump-many-billionaire-enablers/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

37. Cunningham-Cook M. Arizona GOP chair urged violence at the capitol. The Mercers spent $1.5 million supporting her. The Intercept (2021). Available online at: https://theintercept.com/2021/01/14/capitol-riot-mercers-election-unrest/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

38. Krieger N. Climate crisis, health equity, and democratic governance: the need to act together. J Public Health Policy. (2020) 41:4–10. doi: 10.1057/s41271-019-00209-x

40. Hammonds E, Herzig R. The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race in the United States From Jefferson to Genomics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2008).

41. Yudell M. Race Unmasked: Biology and Race in the Twentieth Century. New York, NY: Columbia University Press (2014). doi: 10.7312/columbia/9780231168748.001.0001

43. Byrd WM, Clayton LA. An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race: Beginnings to 1900. New York, NY: Routledge. (2000).

44. Kendi I. Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York, NY: Bold Type Books (2016).

45. Krieger N. Shades of difference: theoretical underpinnings of the medical controversy on black/white differences in the United States, 1830-1870. Int J Health Serv. (1987) 17:259–78. doi: 10.2190/DBY6-VDQ8-HME8-ME3R

46. OED. “datum, n.” OED; Oxford University Press (2020). Available online at: www.oed.com/view/Entry/47434 (accessed 18 January, 2021).

47. Jasanoff S editor. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. Abingdon: Routledge (2004). doi: 10.4324/9780203413845

48. Felt U, Fouché R, Miller CA, Smith-Doerr L editors. The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. 4th ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press (2017).

49. Krieger N. Researching critical questions on social justice and public health: an ecosocial perspective. In: Levy BS, Sidel VW, editors. Social Injustice and Health. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2013). p. 465–84. doi: 10.1093/med/9780199939220.003.0026

50. Krieger N. Public health, embodied history, and social justice: looking forward. Int J Health Serv. (2015) 45:587–600. doi: 10.1177/0020731415595549

51. Krieger N. The US Census and the people's health: public health engagement from enslavement and “Indians not taxed” to census tracts and health equity (1790–2018). Am J Public Health. (2019) 109:1092–100. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305017

52. Anderson MJ. The American Census: A Social History. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press (2015).

53. Emigh RJ, Riley D, Ahmed P. The racialization of legal categories in the first U.S. census. Soc Sci Hist. (2015) 39:485–519. doi: 10.1017/ssh.2015.69

54. US Census Bureau. Measuring Race Ethnicity Across the Decades: 1790-2010, Mapped to 1997 U.S. Office of Management and Budget Classification Standards. (2015). Available online at: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/race/MREAD_1790_2010.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

55. Hogarth RA. Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press (2017).

56. Newman RS. Abolitionism: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2018). doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780190213220.001.0001

57. Sinha M. The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press (2016).

58. Seth S. Difference and Disease: Medicine, Race, and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2018) doi: 10.1017/9781108289726

60. Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. First African-American to hold a medical degree: brief history of James McCune Smith, abolitionist, educator, and physician. Adv Physiol Educ. (2019) 43:134–9. doi: 10.1152/advan.00119.2018

61. Butler PM. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (1808-82): American physician, public health advocate and social reformer. J Med Biogr. (2011) 19:145–50. doi: 10.1258/jmb.2010.010027

62. Guillory JD. The Pro-Slavery Arguments of Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright. Louisiana History (1968) 9:209–227.

63. Cartwright SA. Natural history of the prognathous race of mankind, originally written for the New York day-book (appendix). In: Taney RB, editor The Dred Scott decision. Opinion of Chief Justice Taney, With an Introduction by Dr. J.H. Van Evrie. New York, NY: Van Evrie, Horton & Co (1860). p. 45–8.

64. Taney RB. The Dred Scott Decision. Opinion of Chief Justice Taney, With an Introduction by Dr. J.H. Van Evrie. Also, an Appendix, Containing an Essay on the Natural History of the Prognathous Race of Mankind, Originally Written for the New York Day-Book, by Dr. S.A. Cartwright. New York, NY: Van Evrie, Horton & Co (1860).

65. Konig DT, Finkelman P, Bracey CA editors. The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Athens: Ohio University Press (2010). doi: 10.1353/book.2344

66. Finkelman P. Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation's Highest Court. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2018). doi: 10.4159/9780674982079

67. Gates H. Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow. New York, NY: Penguin Press (2019).

68. Packard J. American Nightmare: The History of Jim Crow. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press (2002).

69. Niedermeier S. The Color of the Third Degree: Racism, Police Torture, and Civil Rights in the American South, 1930-1955. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press (2019).

71. Stern AM. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (2016). doi: 10.1525/california/9780520285064.003.0001

72. Leonard TC. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2016) doi: 10.2307/j.ctvc77cqn

73. Bashford A, Levine P editors. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2010).

74. Levine P. Eugenics: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2017) doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780199385904.001.0001

76. Gerber DA. American Immigration: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2011). doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780195331783.001.0001

77. Belton R. Title VII at forty: a brief look at the birth, death, and resurrection of the disparate impact theory of discrimination. Hofstra Labor Employment Law J. (2004) 22:431–72. Available online at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol22/iss2/4

78. Tobia K. Disparate statistics. Yale Law J. (2017) 126:2382–420. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45223096

79. Siegel RB. Blind justice: why the court refused to accept statistical evidence of discriminatory purpose in McCleskey v. Kemp - and some pathways for charge. Northwest U Law Rev. (2017) 112:1269–92. Available online at: https://perma.cc/JTX8-DTAY

80. Laham N. The Reagan Presidency and the Politics of Race: In Pursuit of Colorblind Justice and Limited Government. Westport, CT: Praeger (1998).

81. Avery M, McLaughlin D. The Federalist Society: How Conservatives Took the Law Back From Liberals. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press (2013). doi: 10.2307/j.ctv16754zd

82. California Republic. Proposition 54, Prohibit State Classification Based on Race in Education, Employment, and Contracting Initiative (October 2003). Available online at: https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_54,_Prohibit_State_Classification_Based_on_Race_in_Education,_Employment,_and_Contracting_Initiative_(October_2003) (accessed January 16, 2021).

83. HoSang D. Racial Propositions: Ballot Initiatives and the Making of Postwar California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (2010). doi: 10.1525/9780520947719

84. California Health Care Foundation. Racial and Ethnic Data Collection and Use in Health Care: Examples of Projects that Might be Affected by Proposition 54. (2003). Available online at: https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-RacialAndEthnicDataCollection.pdf (accessed January 18, 2021).

85. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Proposition 54. Media (2003). Available online at: https://civilrights.org/resource/proposition-54/# (accessed January 18, 2021).

86. Parks S. No on Proposition 54, part 1. ScienceMag.org (2003). Available online at: https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2003/10/no-proposition-54-part-1 (accessed January 18, 2021).

87. Clemmons S. The racial privacy initiative. ScienceMag.org (2003). Available online at: https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2003/08/racial-privacy-initiative (accessed January 18, 2021).

88. Benner K, Green EL. Justice dept. seeks to pare back civil rights protections for minorities. New York Times (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/05/us/politics/justice-department-disparate-impact.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

89. Kendi IX. Stop blaming black people for dying of the coronavirus. The Atlantic (2020). Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/race-and-blame/609946/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

90. Chowkwanyun M, Reed AL Jr. Racial health disparities and COVID-19 – caution and context. New Engl J Med. (2020) 383:201–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2012910

91. Prescod C, Gebremikael L, Ahmed S. Toronto urgently needs a black health strategy to address COVID-19's impact. Toronto Star (2020). Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2020/12/09/toronto-urgently-needs-a-black-health-strategy-to-address-covid-19s-impact.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

92. Michener L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alberti PM, Castaneda MJ, Castrucci BC, Harrison LM, et al. Engaging with communities - lessons (re)learned from COVID-19. Prev Chronic Dis. (2020) 17:E65. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200250

94. Nobles M. Shades of Citizenship: Race and the Census in Modern Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2000).

95. Loveman M. National Colors: Racial Classification and the State in Latin America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2014). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199337354.001.0001

96. Diamond D. Trump officials interfered with CDC reports on COVID-19. Politico (2020). Available online at: https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/11/exclusive-trump-officials-interfered-with-cdc-reports-on-covid-19-412809 (accessed January 18, 2021).

97. Weixel N. House democrats launch investigation of political interference in CDC science publications. The Hill (2020). Available online at: https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/516300-house-democrats-launch-investigation-of-political-interference-in-cdc (accessed January 18, 2021).

98. Stolberg SG. A CDC official says she was ordered to destroy an email showing a trump appointee interfering with a report's publication. New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2020/12/10/world/covid-19-coronavirus#a-cdc-official-says-she-was-ordered-to-destroy-an-email-showing-a-trump-appointee-interfering-with-a-reports-publication (accessed January 18, 2021).

99. Weiland N. Here's how the Trump administration crushed the C.D.C., according to two who were there. New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/16/world/heres-how-the-trump-administration-crushed-the-cdc-according-to-two-who-were-there.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

100. Kendi IX. Why don't we know who the coronavirus victims are? The Atlantic (2020). Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/stop-looking-away-race-covid-19-victims/609250/ (accessed January 16, 2021).

101. Maybank A. Why racial and ethnic data on COVID-19's impact is badly needed. AMA (2020). Available online at: https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/why-racial-and-ethnic-data-covid-19-s-impact-badly-needed (accessed January 18, 2021).

102. Krieger N, Gonsalves G, Bassett MT, Hanage W, Krumholz HM. The fierce urgency of now: closing glaring gaps in US surveillance data on COVID-19. Health Affairs Blog (2020). Available online at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200414.238084/full/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

103. Krieger N. COVID-19, data, and health justice. Commonwealth Foundation (2020). Available online at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/covid-19-data-and-health-justice (accessed January 18, 2021).

104. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/index.htm (accessed January 18, 2021).

105. National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD. (2021). Available online at: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

106. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Leading Health Indicators 2030: Advancing Health, Equity, and Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2020).

107. Branigan A. Black communities are on the “frontline” of the COVID-19 pandemic. here's why. The Root (2020). Available online at: https://www.theroot.com/black-communities-are-on-the-frontline-of-the-covid-19-1842404824 (accessed January 18, 2021).

108. Blow C. The racial time bomb in the COVID-19 crisis. New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/opinion/coronavirus-black-people.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

109. Kendi IX. What the racial data show. The Atlantic (2020). Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/coronavirus-exposing-our-racial-divides/609526/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

110. Eligon J, Burch ADS, Searcey D, Oppel RA Jr. Black Americans face alarming rates of coronavirus infection in some states. New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/us/coronavirus-race.html (accessed January 16, 2021).

111. Haslett C. CDC releases new data as debate over racial disparities in coronavirus deaths. ABC News (2020). Available online at: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/cdc-releases-data-debate-grows-racial-disparities-coronavirus/story?id=70041803 (accessed January 18, 2021).

112. Haslett C. Warren, Pressley renew calls for trove of national data on race and coronavirus, this time aimed at medicare. ABC News (2020). Available online at: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/warren-pressley-renew-call-trove-national-data-race/story?id=70074841 (accessed January 18, 2021).

113. The COVID Tracking Project at the Atlantic. The COVID Racial Data Tracker. Available online at: https://covidtracking.com/race/about (accessed January 16, 2021).

114. Egbert A, Liao K. The color of coronavirus: 2020 year in review. APM Research Lab (2020). Available online at: https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-2020-review (accessed January 18, 2021).

115. New York Times. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data in the United States. Available online at: https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data (accessed January 18, 2021).

116. New York Times. U.S. Coronavirus Data: Frequently Asked Questions. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/about-coronavirus-data-maps.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

117. Weiland N, Mandavalli A. Trump administration sets demographic requirements for coronavirus reports. New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/us/politics/coronavirus-infection-demographics.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

118. US Dept of Health and Human Services. COVID-19 Pandemic Response, Laboratory Data: CARES Act Section 18115. (2020). Available online at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/covid-19-laboratory-data-reporting-guidance.pdf (accessed January 18, 2021).

119. Krieger N, Testa C, Hanage WP, Chen JT. US racial and ethnic data for COVID-19 cases: still missing-in-action. Lancet. (2020) 396:E81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32220-0

120. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Disparities: Race and Hispanic Origin. Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Table 1. Count and Percent Distribution of Deaths Involving Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) With Distribution of the Weighted and Unweighted Percent Population by Race and HISPANIC Origin Group, for the United States and Jurisdictions with More Than 100 Deaths Available for Analysis. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm (accessed January 18, 2021).

121. Cowger TL, Davis BA, Etkins OS, Makofane K, Lawrence JA, Bassett MT, et al. Comparison of weighted and unweighted population data to assess inequities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 deaths by race/ethnicity reported by the US centers for disease control and prevention. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2016933. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16933

122. National Institutes of Health. NIH Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. NOT94-100. NIH Guide (1994). Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not94-100.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

123. National Institutes of Health. NIH Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. NOT-OD-048. (2000). Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-00-048.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

124. National Institutes of Health. NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. NOT-OD-02-001 (2001). Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm (accessed January 18, 2021).

125. National Institutes of Health. Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Participants in Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities (accessed January 10, 2021).

126. Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Reg. (1997) 62:58782–90. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1997-10-30/pdf/97-28653.pdf [accessed January 18, 2021).

127. National Institutes of Health. Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-FUNDED research, NOT-OD-15-102. (2015). Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-102.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

128. National Institutes of Health. Guidelines for “Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-funded research”. (2015). Available online at: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/NOT-OD-15-102_Guidance.pdf (accessed January 18, 2021).

129. Shattuck-Heidorn H, Richardson SR. Sex/gender and the biosocial turn. The Scholar & Feminist Online (2019). Available online at: http://sfonline.barnard.edu/neurogenderings/sex-gender-and-the-biosocial-turn/# (Accessed January 18, 2021).

130. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. (2019). Available online at: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf (accessed January 18, 2021).

131. American Journal of Public Health. Editorial Policies, Non-Discriminatory Language. Available online at: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/authorinstructions/editorial-policies (accessed January 18, 2021).

132. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Using the methods of the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project to Monitor COVID-19 Inequities and Guide Action for Health Justice. (2020). Available online at: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/thegeocodingproject/covid-19-resources/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

133. NYU Langone Health. City Health Dashboard. Metrics: Social and Economic Factors. Available online at: https://www.cityhealthdashboard.com/metrics (accessed January 18, 2021).

134. PhenX Toolkit. Social Determinants of Health Collection: Core, Individual, Structural. RTI International (2020). Available online at: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/collections/view/6 (accessed January 18, 2021).

135. Beckfield J. Political Sociology and the People's Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2018). doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190492472.001.0001

136. Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT. COVID-19 and overall mortality inequities in the surge in death rates by ZIP Code characteristics: Massachusetts, January 1 to May 19, 2020. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1850–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305913

137. Chen JT, Krieger N. Revealing the unequal burden of COVID-19 by income, race/ethnicity, and household crowding: us county versus ZIP code analyses. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2021) 27 (Suppl. 1):S43–56. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001263

138. Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, Baral S, Mercer L, Beyrer C, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. (2020) 47:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003

139. Benitez J, Courtemanche C, Yelowitz A. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19: evidence from six large cities. J Econ Race Policy. (2020) 3:243–61 doi: 10.1007/s41996-020-00068-9

140. Cordes J, Castro MC. Spatial analysis of COVID-19 clusters and contextual factors in New York City. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. (2020) 34:100355. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2020.100355

141. Scannell Bryan M, Sun J, Jagai J, Horton DE, Montgomery A, Sargis R, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality and neighborhood characteristics in Chicago. Ann Epidemiology. (2020) 56:47–54.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.10.011

142. Adhikari S, Pantaleo NP, Feldman JM, Ogedegbe O, Thorpe L, Troxel AB. Assessment of community-level disparities in Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections and deaths in large US Metropolitan Areas. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2016938. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16938

143. Seto E, Min E, Ingram C, Cummings BJ, Farquhar SA. Community-level factors associated with COVID-19 Cases and testing equity in King County, Washington. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:9516. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249516

144. University College London. UCL Makes Formal Apology for its History and Legacy of Eugenics. (2021). Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2021/jan/ucl-makes-formal-public-apology-its-history-and-legacy-eugenics (accessed January 18, 2021).

145. Adams R. University College London apologises for role in promoting eugenics: links to early eugenicists such as Francis Galton a source of ‘Deep Regret' to institution. The Guardian (2021). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jan/07/university-college-london-apologises-for-role-in-promoting-eugenics (Accessed January 18, 2021).

146. University College London. UCL Denames Buildings Named After Eugenicists. (2020). Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2020/jun/ucl-denames-buildings-named-after-eugenicists (accessed January 18, 2021).

147. US Census Bureau. Foreign Born: About (2020). Available online at: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/foreign-born/about.html#par_textimage (accessed January 18, 2021).

148. National Center for Health Certificates. Revisions of the U.S. Standard Certificates and Reports. (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/revisions-of-the-us-standard-certificates-and-reports.htm (accessed January 18, 2021).

149. US Census. Educational Attainment: About. (2020). Available online at: https://www.census.gov/topics/education/educational-attainment/about.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

150. US Census. American Community Survey. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

151. US Census. Household Pulse Survey: Measuring Social and Economic Impacts During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

152. University of Richmond's Digital Scholarship Lab and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Not Even Past: Social Vulnerability and the Legacy of Redlining. Available online at: https://dsl.richmond.edu/socialvulnerability/ (accessed January 18, 2021).

Keywords: anti-racism, data governance, ecosocial theory of disease distribution, health equity, population health, politics of public health data, public health monitoring, structural racism

Citation: Krieger N (2021) Structural Racism, Health Inequities, and the Two-Edged Sword of Data: Structural Problems Require Structural Solutions. Front. Public Health 9:655447. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.655447

Received: 18 January 2021; Accepted: 09 March 2021;

Published: 15 April 2021.

Edited by:

Regina Davis Moss, American Public Health Association, United StatesReviewed by:

Rachel Hardeman, University of Minnesota, United StatesHuabin Luo, East Carolina University, United States

Derek M. Griffith, Vanderbilt University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Krieger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nancy Krieger, bmtyaWVnZXJAaHNwaC5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==

Nancy Krieger

Nancy Krieger