- 1Institute of Public Health, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Institute of Gerontological Health Services and Nursing Research, Ravensburg-Weingarten University of Applied Sciences, Weingarten, Germany

- 3Research Group Work and Health, Department of Psychology, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

- 4Department of Work and Organizational Psychology, International Institute of Management and Economic Education, Europa-Universität Flensburg, Flensburg, Germany

Editorial on the Research Topic

Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Between Humor and Health: Theoretical Foundations, Empirical Evidence and Implications

Introduction

Humor is a ubiquitous phenomenon in our daily lives. People might be exposed to it at a diversity of times and places from social interactions to medial representations (1). Humor is also an integral part of aspects which are directly or indirectly related to health and well-being (2, 3).

Based on previous research, we can understand humor as a personality tendency referring to a sensation (amusement), to a behavior (laughter or smiling), to its use as a way of coping (humor as a coping mechanism), to an ability (production and creation of stimuli) and finally, to an aesthetic sense (sense of humor, appreciation of humor) (4). Having a good sense of humor is thought to be a healthy and desirable personality trait as it refers to the readiness to respond positively to serious, uncomfortable and stressful situations and may, therefore, be used as a coping strategy (5). In positive psychology, humor is viewed as a personal quality promoting resilience and well-being by means of cognitive reappraisal of stressful events (6). Humor has a broad range of effects on perceptions, attitudes, judgments, and emotions. In this regard, studies have associated humor and laughter with several physiological, psychological, sociological, and behavioral benefits for physical and mental health (2, 7–9).

Functions of Humor

Based on the positive effects on health promotion and disease prevention, the question has been raised whether humor and laughter can be used in therapeutic settings (10). For example, humorous interactions between patients and service providers can support the therapeutic relationship (11, 12), and positively influence patients' experiences (11, 13). While the relationship between humor and health has been investigated through different perspectives, some areas are still under-researched (13). Communication studies, for instance, have primarily focused on the implications of mass media. In this context, it was observed that humor in advertisements enhances attention and improved the persuasiveness of preventive messages (14, 15). Whilst preventive health campaigns appeal to negative emotions like fear in order to dissuade their audience from hazardous health behavior, the use of fear can lead to defensive reactions, such as avoidance or denial. In order to circumvent the phenomenon whereby preventive messages are perceived as a threat to an individual's attitudinal freedom, introducing humor in health warnings may open the audience for arguments in favor of health. Because counterargument appears to be one of the most effective strategies used to resist persuasion (16), it remains an open question which effect the use of humor in health messages may have (15). However, humorous messages generally have the potential to reduce health-based anxiety and, in turn, promote positive behavior (17).

Papers of the Research Topic

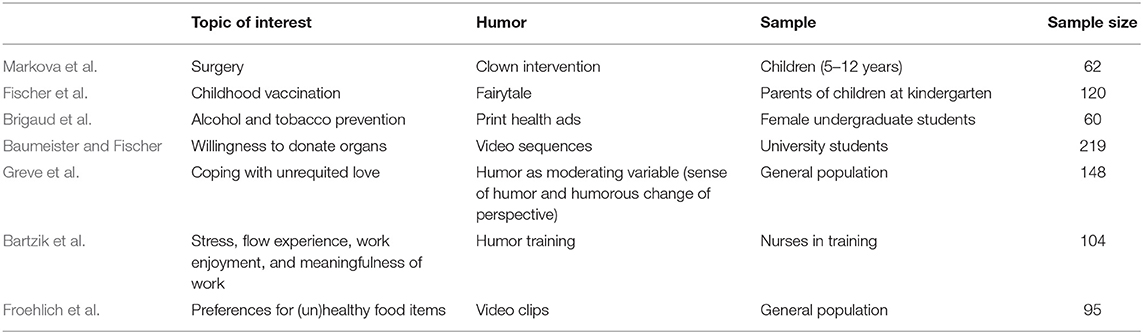

The Research Topic “Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Between Humor and Health: Theoretical Foundations, Empirical Evidence and Implications” includes perspectives on the relationship between humor and health from various scientific disciplines, covering a variety of topics and samples (Table 1). From overall seven manuscripts published in this Research Topic (Markova et al.; Fischer et al.; Brigaud et al.; Baumeister and Fischer; Greve et al.; Bartzik et al.; Froehlich et al.), six used humor in an intervention study (Markova et al.; Fischer et al.; Brigaud et al.; Baumeister and Fischer; Bartzik et al.; Froehlich et al.), whereas one investigated humor as a moderating variable (Greve et al.). Half of the intervention studies used humor in the context of health communication (Fischer et al.; Brigaud et al.; Baumeister and Fischer; Froehlich et al.).

Among all studies, a variety of topics were covered: Some of them were directly related to healthcare provision, focusing either on a clown intervention for children undergoing surgery (Markova et al.) or on a humor intervention for nurses in training to reduce stress, and increase flow experience, work enjoyment, and perceived meaningfulness of work (Bartzik et al.); others focused on health-related factors such as nutrition (Froehlich et al.), alcohol and tobacco prevention (Brigaud et al.), organ donation (Baumeister and Fischer), childhood vaccination (Fischer et al.), and one further manuscript investigated humorous coping with unrequited love (Greve et al.). The study samples consisted of children undergoing surgery (Markova et al.), female undergraduate students (Brigaud et al.), university students (Baumeister and Fischer), parents of children at kindergarten (Fischer et al.), nurses in training (Bartzik et al.), and the general population (Greve et al.; Froehlich et al.).

Future Research Directions

The short description of study characteristics shows the broad range of existing research related to humor. The well-conducted papers published in this Research Topic provide urgently needed evidence in this area and may, therefore, serve as a starting point for intensified research activities in the future. Until now, studies on humor and its implications on health are still a relatively new area of research. Thus, the current state of the art calls for greater research efforts employing careful theoretical formulations and sophisticated and rigorous methodological approaches. Despite widespread popular beliefs in the health benefits of humor and laughter, the research evidence for these effects is still quite weak, inconsistent and inconclusive (3, 18).

The major challenge for future research will be the operationalization of the complex and multidimensional construct of humor in the context of health-related activities. A clear distinction between humor, laughter and other (pleasant) emotions—and their link to health-related issues—is partially missing. Different components of humor are currently reflected in various conceptualizations. However, previous research has focused mainly on humor as a vague and oversimplified term (19), irrespective of further specifications, such as the style of humor. This may lead to biased and indistinct results when considering the effects of humor.

Further emphasis needs to be placed on the hypothesized mechanisms by which specific types of humor may affect health. It is essential to elaborate whether positive effects relate to physiological changes in the body caused by humor and laughter, effects from positive emotions (such as cheerfulness and optimism) (20), indirect effects from the alleviation of stressors or the proliferation of social support through the use of humor in interpersonal relationships (3).

We do hope that the studies published in this Research Topic provide new insights and underline the need for well-conducted studies dealing with the relationship between humor and health, going even beyond the topics, methods, and disciplinary perspectives covered in our call.

Author Contributions

FF drafted the manuscript. CP and TS revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all reviewers who spent their time to review the manuscripts submitted to our Research Topic.

References

1. Fiacconi CM, Owen AM. Using psychophysiological measures to examine the temporal profile of verbal humor elicitation. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0135902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135902

2. Martin RA. Humor, laughter, and physical health: methodological issues and research findings. Psychol Bull. (2001) 127:504–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.504

3. Martin RA. Sense of humor and physical health: theoretical issues, recent findings, and future directions. Humor. (2004) 17:1–19. doi: 10.1515/humr.2004.005

4. Hehl F-J, Ruch W. The location of sense of humor within comprehensive personality spaces: an exploratory study. Pers Indiv Differ. (1985) 6:703–15. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(85)90081-9

5. Chapman AJ, Foot HC. Humor and Laughter: Theory, Research, and Applications. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers (1996).

6. Kuiper NA. Humor and resiliency: towards a process model of coping and growth. Eur J Psychol. (2012) 8:475–91. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v8i3.464

7. Bennett MP, Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health IV. Humor and immune function. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2009) 6:159–64. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem149

8. Claxton-Oldfield S, Bhatt A. Is there a place for humor in hospice palliative care? Volunteers say “Yes”! Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2017) 34:417–22. doi: 10.1177/1049909116632214

9. Fry WF. Humor, physiology, and the aging process. In: Nahemow L, McCluskey-Fawcett KA, McGhee PE, editors, Humor and Aging. Burlington: Elsevier (2013). p. 81–98. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-513790-4.50011-X

11. Haydon G, van der Reit P, Browne G. A narrative inquiry: humour and gender differences in the therapeutic relationship between nurses and their patients. Contemp Nurse. (2015) 50:214–26. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1021436

12. Haydon G, van der Riet P. A narrative inquiry: how do nurses respond to patients' use of humour? Contemp Nurse. (2014) 46:197–205. doi: 10.5172/conu.2014.46.2.197

13. McCreaddie M, Payne S. Humour in health-care interactions: a risk worth taking. Health Expect. (2014) 17:332–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00758.x

14. Ahmed OH, Lee H, Schneiders AG, McCrory P, Sullivan SJ. Concussion and comedy: no laughing matter? PM R. (2014) 6:1071–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.08.945

15. Blanc N, Brigaud E. Humor in print health advertisements: enhanced attention, privileged recognition, and persuasiveness of preventive messages. Health Commun. (2014) 29:669–77. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.769832

16. Jacks JZ, Cameron KA. Strategies for resisting persuasion. Basic Appl Soc Psych. (2003) 25:145–61. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2502_5

17. Nabi RL. Laughing in the face of fear (of disease detection): using humor to promote cancer self-examination behavior. Health Commun. (2016) 31:873–83. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.1000479

18. Fritz HL, Russek LN, Dillon MM. Humor use moderates the relation of stressful life events with psychological distress. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2017) 43:845–59. doi: 10.1177/0146167217699583

19. Martin RA, Ford T. The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science & Technology (2018).

Keywords: health communication, mass media, prevention, emotion, positive psychology

Citation: Fischer F, Peifer C and Scheel T (2021) Editorial: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Between Humor and Health: Theoretical Foundations, Empirical Evidence and Implications. Front. Public Health 9:774353. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.774353

Received: 11 September 2021; Accepted: 05 October 2021;

Published: 25 October 2021.

Edited and reviewed by: Harshad Thakur, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, India

Copyright © 2021 Fischer, Peifer and Scheel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Florian Fischer, Zmxvcmlhbi5maXNjaGVyMUBjaGFyaXRlLmRl

Florian Fischer

Florian Fischer Corinna Peifer

Corinna Peifer Tabea Scheel

Tabea Scheel