- 1UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, Population, Policy and Practice Research and Teaching Department, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2UCL Institute of Education, Social Research Institute, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3UCL Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4The Evidence Based Practice Unit, University College London and Anna Freud Centre for Children and Families, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Absence from school is more frequent for children with chronic health conditions (CHCs) than their peers and may be one reason why average academic attainment scores are lower among children with CHCs.

Methods: We determined whether school absence explains the association between CHCs and academic attainment through a systematic review of systematic reviews of comparative studies involving children with or without CHCs and academic attainment. We extracted results from any studies that tested whether school absence mediated the association between CHCs and academic attainment.

Results: We identified 27 systematic reviews which included 441 unique studies of 7, 549, 267 children from 47 jurisdictions. Reviews either covered CHCs generally or were condition-specific (e.g., chronic pain, depression, or asthma). Whereas reviews found an association between a range of CHCs (CHCs generally, cystic fibrosis, hemophilia A, end-stage renal disease (pre-transplant), end-stage kidney disease (pre-transplant), spina bifida, congenital heart disease, orofacial clefts, mental disorders, depression, and chronic pain) and academic attainment, and though it was widely hypothesized that absence was a mediator in these associations, only 7 of 441 studies tested this, and all findings show no evidence of absence mediation.

Conclusion: CHCs are associated with lower academic attainment, but we found limited evidence of whether school absence mediates this association. Policies that focus solely on reducing school absence, without adequate additional support, are unlikely to benefit children with CHCs.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=285031, identifier: CRD42021285031.

1. Introduction

On average, children with chronic health conditions (CHCs) are less likely to perform well in school exams than their healthy peers (1–4), a factor which is a particular concern for children and young people (5), their parents (6), teachers (7, 8) and policymakers alike (9–11). One possible mechanism that explains poorer average academic attainment among such children is absence from school related to their CHC. Although school absence is extremely common, it is particularly prevalent among children with CHCs (3), who are more likely to be absent due to illness and healthcare usage (4). Absence from school is assumed to cause lower attainment partly due to the strong association reported in a national analysis by the UK Department for Education (12), which found that every extra day missed from school was associated with lower attainment (13).

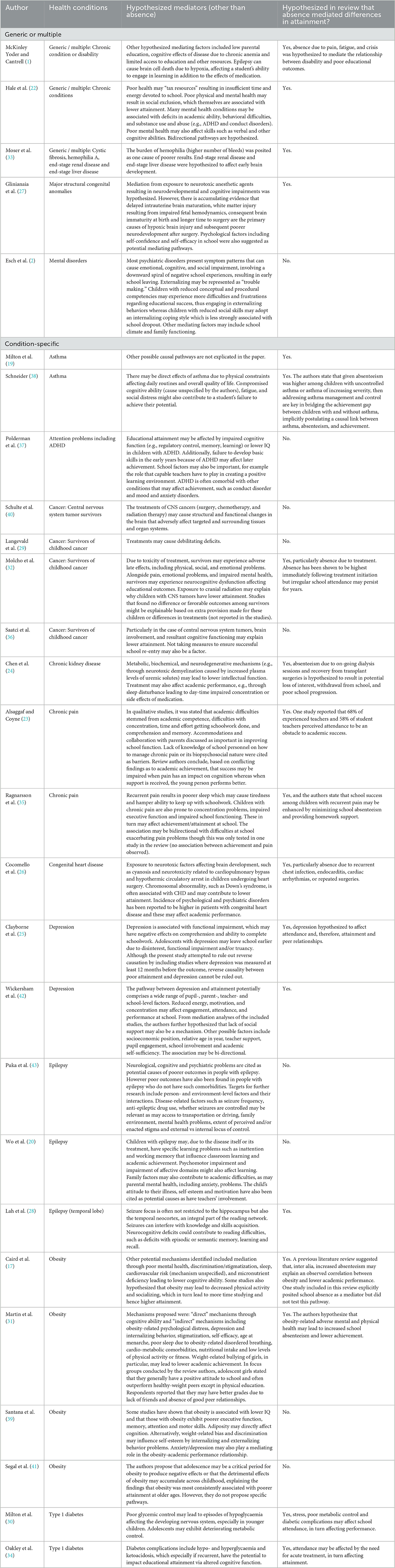

Evidence that absence causes lower attainment is critical to guide how schools respond to absence among children with CHCs. CHCs are common: Van Cleave et al. (14) estimated that, between ages 8 and 14 years, the cumulative prevalence of having a parent-reported CHC was between 13% and 27% depending on the year of birth and case definition. The Department for Education study did not explore whether absence caused low attainment, particularly among children with CHCs. Analyses that distinguish whether absence mediates the effect of CHCs on school attainment need to take into account common causes of CHCs, increased absence, and reduced attainment (Figure 1). For example, the health condition itself, or its clinical management, may be a cause of school absence, especially symptom-related absence, and independently, a cause of reduced attainment, particularly for conditions linked to cognitive or behavioral deficits. Socioeconomic factors may also be a common cause of CHCs, absence, and attainment given well-known links between poorer socioeconomic status and health as well as school absence (15) and lower attainment (16).

Figure 1. Simplified directed acyclic graph showing hypothesized relationships between chronic health conditions, school absence, socioeconomic confounders, and academic attainment.

In England, the Children's Commissioner, an influential official responsible for promoting the views and interests of children, has called for a reduction of school absence to zero percent (11). Official government guidance, reflecting statutory provisions, does not mandate a reduction of absence to zero but instead emphasizes the legal duty incumbent on parents to ensure that their child, when enrolled in a school, attends school every day. The guidance also recognizes that children with long-term health conditions face additional barriers to attendance which must be addressed to ensure that they can enjoy their right to full-time education (13). Policies aimed at reducing absence to zero could benefit children with CHCs if school absence is the mechanism, or mediator, through which CHCs reduce academic attainment. However, if the relationship between absence and attainment is because CHCs, or other factors linked to CHCs (such as socioeconomic circumstances), are a common cause of increased absence and reduced attainment, then focusing on reducing absence may not be helpful and could be harmful, especially if not accompanied by adequate resources to meet the needs of children with CHCs in schools.

Policies that focus on reducing absence can have adverse consequences for children and young people with a CHC. In preparation for our programme of work on CHCs and education, we consulted a group of 22 children and young people with and without CHCs (November 2021) and a separate group of six parents of affected children (May 2022). Some reported feeling alienated by school practices around attendance and discipline, such as strict behavior policies and parents and children being labeled a “problem” in relation to frequent absence. Others mentioned the pressure to explain and justify their illness, evidence a diagnosis, which is sometimes not possible, and to return to school before full recovery. Some students and parents felt there was inflexibility from the school, such as setting arbitrary attendance targets, and lack of understanding of learner needs leading to difficulties in the classroom. These potential harms underline the need for clear evidence of the benefit of absence reduction policies on student attainment, health, and wellbeing.

This umbrella review (i.e., a systematic review of systematic reviews) aimed to inform policy responses to school absence by reviewing the evidence for absence being the mechanism mediating the association between CHCs and academic attainment. We (a) reviewed evidence from systematic reviews that presented evidence of an association between CHCs and academic attainment and (b) we examined the subset of studies that tested whether absence mediated the association between CHCs and academic attainment by exploring what the results were and how the studies accounted for confounding. We report results separately for different CHCs because the causes, treatments, and effects on academic attainment may differ. For example, some conditions or treatments may cause direct cognitive impairments such as central nervous system tumors and their treatment, whereas other conditions, such as asthma, would not.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protocol registration

We, a priori, developed a protocol and registered it with the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews (CRD42021285031). This review is reported according to the PRISMA statement (Supplementary File 1).

2.2. Inclusion criteria

We included any systematic review of comparative, quantitative studies of any design that quantified the association between a CHC in childhood and academic attainment. CHC status (different types or levels of severity or CHC vs. none) had to be considered as the exposure and a measure of academic attainment as the outcome. Academic attainment could be measured based on these factors: school grades, administered standardized tests of, for example, reading or mathematical ability, whether children graduated from compulsory schooling, or whether they experienced grade retention (i.e., “held back” a year). We included these measures whether they were labeled as academic attainment, achievement, or some other construct but refer to them in this study collectively as academic attainment. Reviews were excluded if they were not a published systematic review (e.g., a narrative review or conference abstract only and no associated, published systematic review could be found and the authors could not be reached) or the review was not peer-reviewed.

2.3. Information sources and search strategy

On 27 September 2021, one author (MAJ) searched MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO via Ovid. MAJ also searched the Education Resource Information Center (ERIC) and the Education Database, both via ProQuest, on 14 October 2021. On 22 March 2022, MAJ further searched all the above databases for reviews related to chronic gastroenterological conditions as keywords for these were omitted from our initial searches. Full search terms and numbers of hits are available in Supplementary File 2. In summary, titles and abstracts were searched for keywords first relating to CHCs (using both generic terms such as “chronic condition*” and specific conditions such as “asthma”) combined with a detailed list of terms for educational outcomes adapted from Caird et al. (17). MAJ and another author (DSE) also scanned reference lists of included reviews for further eligible systematic reviews, and we used Google Scholar to search for systematic reviews citing the systematic reviews included. No language, country, or date limitations were specified.

2.4. Selection process

The results from the database searches were downloaded as *.RIS files and imported into the Mendeley reference management software. Using a Google Form, which was piloted on the first 50 records, two authors (MJ and DS-E) independently screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility. The same two authors then independently screened the full texts of potentially eligible studies, including those identified from the reference list and Google Scholar searches. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with reference to a third reviewer (RG) necessary in one instance.

2.5. Data extraction and effect measures

One author (MJ) examined all included studies and extracted into Microsoft Excel the following information about each review: its authors, year of publication, outcomes studied, language and year limits, inclusion criteria, the number of studies examining academic attainment out of the total number of studies included, whether the review authors hypothesized or assumed that absence was a mediator in any association between CHCs and academic attainment, and any other hypothesized mediators. Whether a particular factor was considered a mediator by the review authors was determined from the language used throughout each manuscript indicating a hypothesized or assumed causal relationship among the CHC, absence, and academic attainment. The review authors did not have to use terms such as “mediator” or “mediation.”

From each review, the following were also extracted for the subset of studies examining academic attainment (i.e., ignoring studies included in the review that examined other outcomes, such as receipt of special educational services): sample sizes of the studies, their countries, comparison groups, overall results on academic attainment, whether the study empirically tested whether the absence was a mediator and, if so, the results of that test. Where mediation was analyzed, we also collected details about the analysis used including statistical methods used, and whether the analyses were adjusted for confounding variables (and, if so, which variables).

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (MJ and DS-E) both independently used the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool to assess the risk of bias in the reviews. The ROBIS assesses systematic reviews on four domains (study eligibility criteria, identification and selection of studies, data collection and study appraisal, and synthesis and findings) and results in an overall assessment of the risk of bias. For each domain and the overall assessment, a review can be rated as low, high, or unclear risk. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

2.7. Synthesis

The systematic reviews were described narratively in terms of target conditions, outcomes, language and year limits, inclusion criteria, number of studies included, sample sizes of included studies, comparison groups, overall results on attainment, and risk of bias. The individual studies within the reviews were described quantitatively in terms of the conditions studied, countries, years, and whether the sample was drawn from a clinical or community population. As some individual studies were included in more than one review, it was necessary to deduplicate the database of individual studies prior to analysis. A study was only considered a duplicate if it was cited in more than one systematic review for the same condition. For example, the individual study by Austin et al. (18), which examined asthma and epilepsy, was cited by both Milton et al. (19) (on asthma) and Wo et al. (20) (on epilepsy). Since different analyses were used in reviews of different conditions, this was not considered a duplicate. Where a study was cited by a review of CHCs generally and by a more specific review (e.g., Fletcher (21), which was cited by Esch et al. (2) (mental disorders) and Hale et al. (22) and McKinley Yoder and Cantrell (1) (both of CHCs generally), the study was counted under the more specific condition.

Finally, we identified the hypothesized causal mechanisms proposed by the review authors. We calculated the number and proportion of reviews within which school absence was a hypothesized or assumed mediator. We calculated the number and proportion of individual studies within which absence mediation was empirically tested, and we present the results of these analyses separately as well as their strengths and limitations in relation to study design and statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Review selection

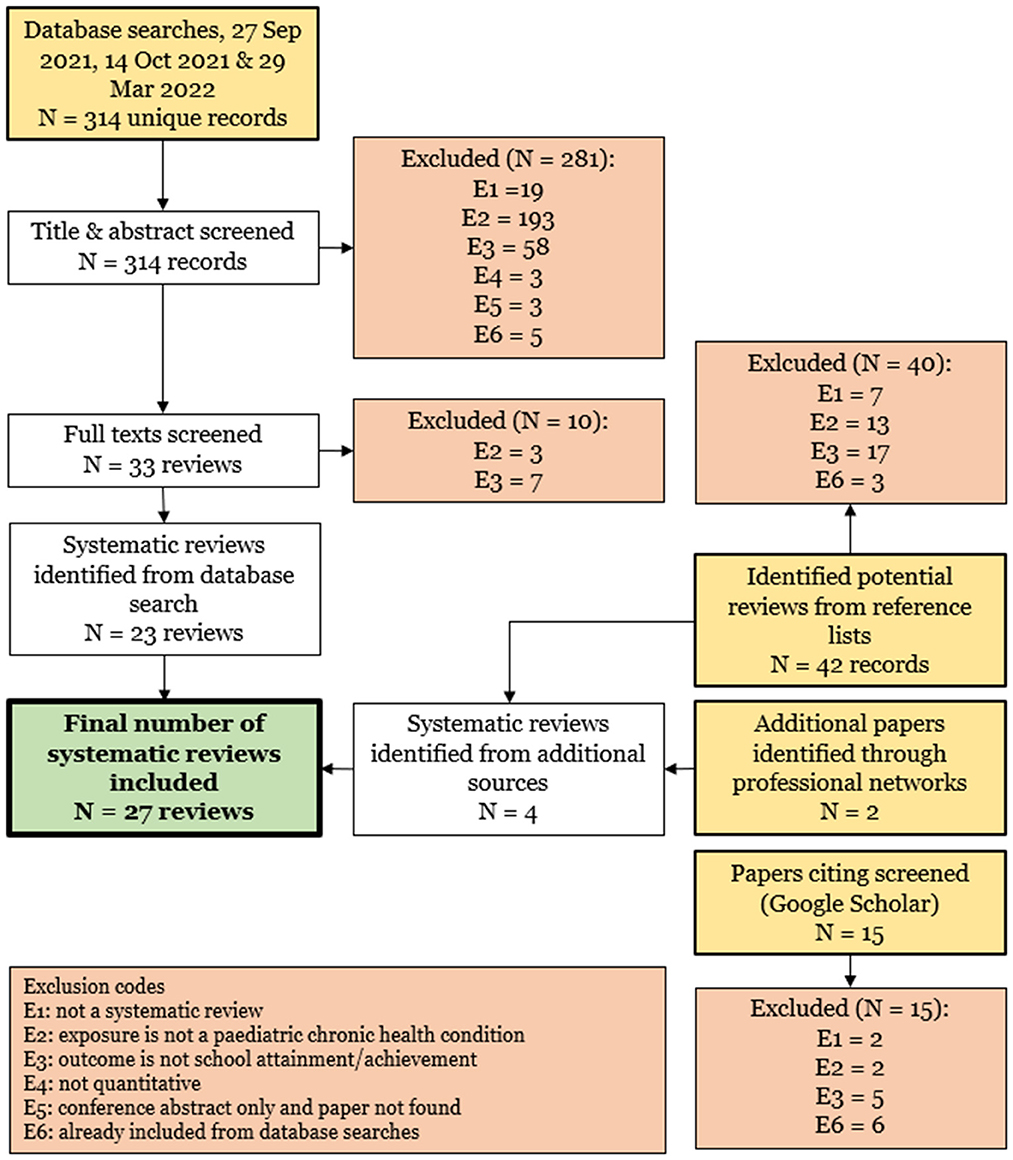

Our database searches identified 314 unique records, of which 281 were excluded by initial screening (Figure 2). Of the 33 full texts screened, 10 were excluded, resulting in 23 reviews identified from database searches. An additional four reviews were identified from reference lists (two reviews) and professional networks (two reviews). No additional reviews were identified from Google Scholar forward citation searches. The final number of reviews included was therefore 27 (1, 2, 17, 19, 20, 22–43).

3.2. Characteristics of reviews and studies

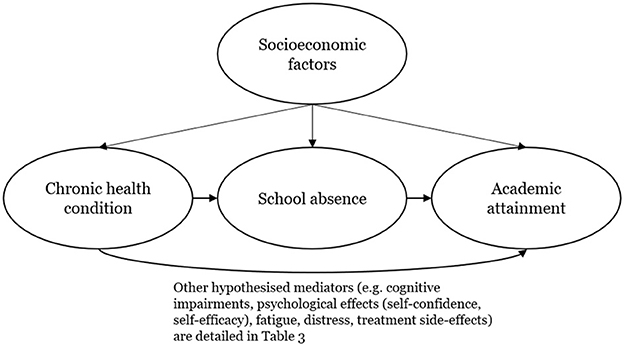

An overview of the reviews, their results on academic attainment, and the results on absence mediation are given in Table 1. Further details on the reviews (health conditions, outcomes, language limits, years covered, inclusion criteria, number of studies, countries, sample sizes, comparison groups, and overall results) are given in Supplementary File 3. Further information on absence mediation is presented below.

Table 1. Overview of reviews and studies on chronic health conditions, school absence, and school achievement or attainment.

Five reviews focused on CHCs in general or multiple CHCs (2, 22, 27, 33). Two of these included any chronic condition (1, 22), one included studies on cystic fibrosis, hemophilia A, end-stage renal disease, or end-stage liver disease (33), one included various major structural congenital anomalies (27), and one included mental disorders (2). The remaining 22 reviews were condition-specific covering asthma (19, 38), attention problems (37), cancer (29, 32, 36, 40), chronic kidney disease (24), chronic pain (23, 35), congenital heart disease (26), depression (25, 42), epilepsy (20, 28, 43), obesity (17, 31, 39, 41), and type 1 diabetes (30, 34). Most reviews (n = 21) only included studies written in English (1, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 27–34, 38–43). One included studies in English, French, or German (2), one included studies in English or Swedish (35), and four specified no language limits (24, 26, 36, 37). Supplementary File 3 also shows year limits imposed by the reviews, study inclusion criteria, number of studies included per review, their sample sizes, and comparison groups. In some instances, reviews required a healthy comparison group though this was not universal, and some reviews included studies with population norms as the comparator or children with different stages of disease (e.g., children on renal dialysis vs. those who had received a renal transplant).

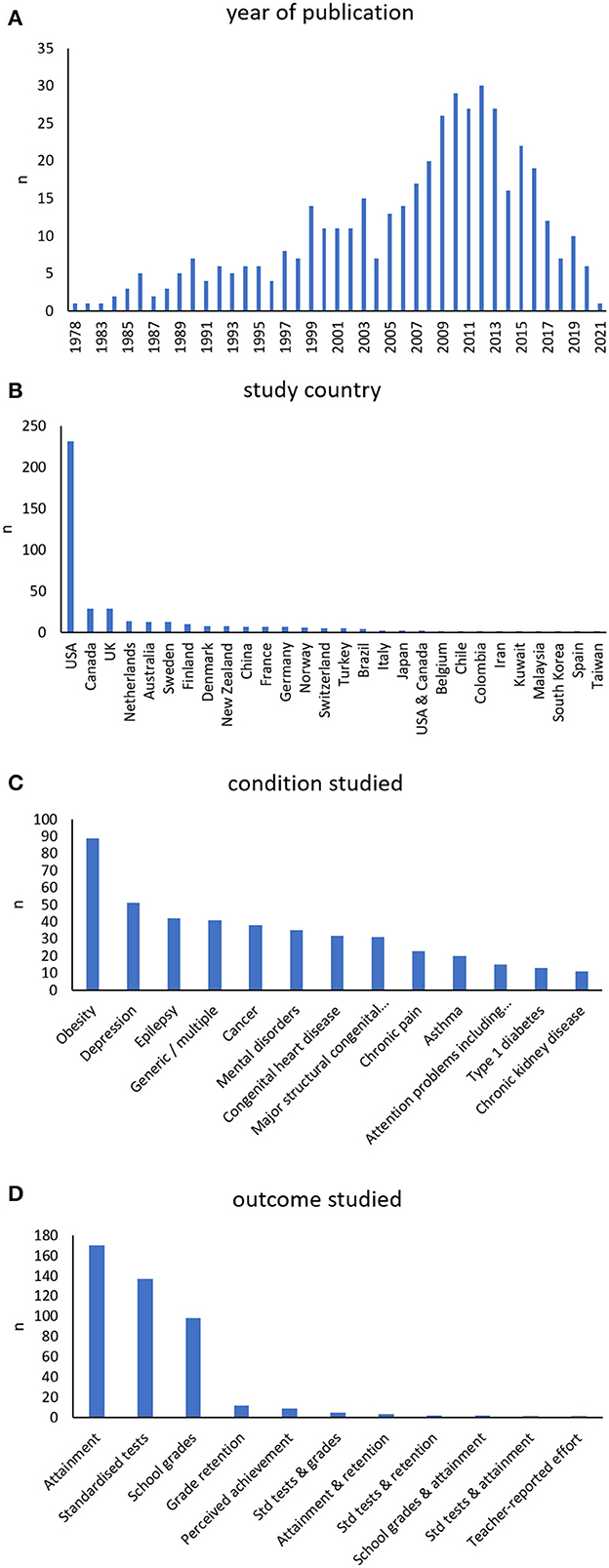

Before deduplication, the 27 reviews included 472 studies. After deduplication, there were 441 studies covering a total of 7, 549, 267 children from 47 regions. Of the 441 studies, 268 (61%) drew their samples from community populations (or were analyses of whole-population administrative data or registries) and the remaining 173 studies (39%) used clinical samples. The years of publication of the individual studies, as well as their countries, conditions studied, and outcome measures are shown in Figure 3. Most of the included research was published since the turn of the millennium (Figure 3A) and research from the USA dominated, with 231 (52%) studies from that country (Figure 3B). The top five conditions studied the most were obesity in 89 (20%) studies, followed by depression, epilepsy, chronic conditions generally, and cancer (Figure 3C). Studies used a range of educational measures, most commonly attainment of a particular level of education (170 studies, 39%), followed by administration of standardized tests (137 studies, 31%) and school grades (98 studies, 22%) as shown in Figure 3D. Twelve studies examined grade retention, nine examined perceived achievement, and one used a teacher-reported effort score. The rest of the studies used a mix of attainment, grades, grade retention, and standardized tests.

Figure 3. The year of publication (A), study country (B), condition studied (C), and outcome measure used (D) in each of the 441 studies included in the systematic reviews. In panel (B), only regions with at least two studies are shown. Regions omitted from the graph with only one study were Austria, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Jamaica, South Korea, Malta, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. There were also single studies covering multiple regions: Finland and Sweden, Australia and New Zealand, several high-income countries, Scandinavia, the USA, the UK, and Canada, and the World Mental Health Survey.

3.3. Risk of bias assessment of reviews

The results from the risk of bias analysis using the ROBIS tool are presented in Supplementary File 4.

3.4. Results on achievement or attainment

Most reviews concluded that CHCs were associated with lower academic attainment (Table 1 and Supplementary File 3). Associations between having a CHC and lower academic attainment were reported for CHCs generally, cystic fibrosis, hemophilia A, end-stage renal disease (pre-transplant), end-stage kidney disease (pre-transplant), spina bifida, congenital heart disease, orofacial clefts, mental disorders, depression, and chronic pain (1, 2, 22–27, 33, 35, 42). The results for asthma were mixed with one review (19) concluding that asthma was not associated with lower academic attainment, except possibly severe asthma, whereas in another review (38), five out of eight studies found lower academic attainment in children with asthma. In terms of cancer, association with central nervous system tumors was most persistently observed (29, 32, 36, 40). Evidence for poorer academic attainment among survivors of other cancers was mixed and weaker. Similarly, evidence as to epilepsy was mixed (20, 28, 43) though children with epilepsy with poor prognosis had significantly poorer results in one review (43). Conclusions from the reviews of obesity were that, if there is an association, it is likely not of clinical significance (17, 31, 39, 41). Evidence for type 1 diabetes was mixed and weak (30, 34). Finally, attention problems were associated with lower academic attainment in a review of 15 studies (37), but in 2 studies at low risk of bias, there was no association once IQ and socioeconomic status were adjusted for.

3.5. Absence mediation

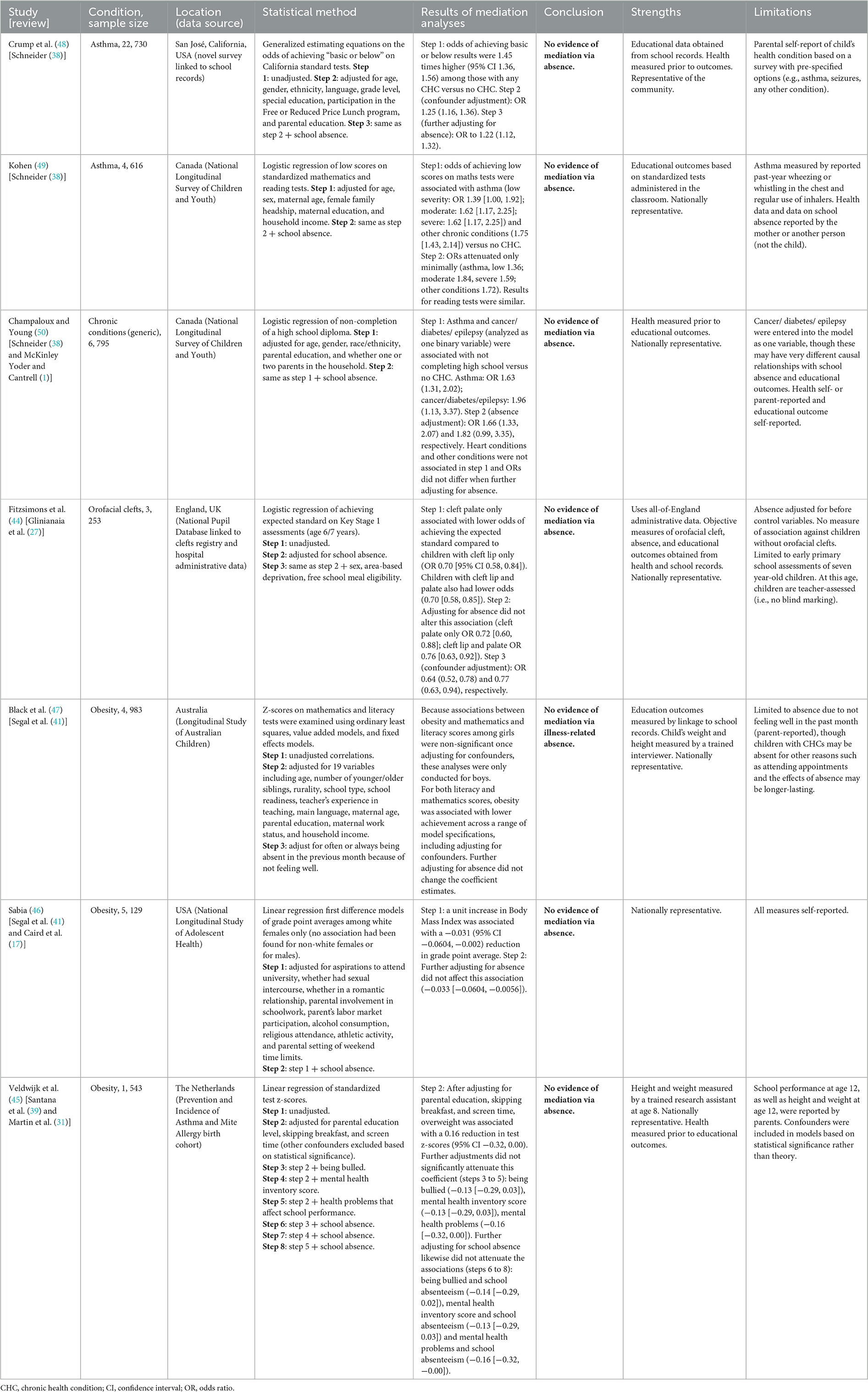

Table 1 shows that in 18 of the 27 reviews (67%), it was hypothesized that school absence was a mediator. However, this was tested in only 7 of 441 studies (2%) (44–50). Details for these studies, which examined asthma, obesity, orofacial clefts, and cancer/diabetes/epilepsy (analyzed as one, binary variable), on the one hand, and academic attainment, on the other, are shown in detail in Table 2. Comparisons, as detailed in Table 2, were either with children without CHCs or between different levels of severity of CHCs. In six of the seven studies (45–50), multiple regression modeling was used to first adjust for confounding factors, and then additionally adjust for school absence. In all six studies, there was no evidence that school absence was a mediator in the association between each CHC and academic attainment. In the seventh study of orofacial clefts (44), multiple regression was also used, but school absence was adjusted for first, and then confounders were entered into the model. In both steps, the model coefficients were the same. Therefore, from all seven studies, no evidence of absence mediation was found.

Table 2. Results of analyses of school absence mediation in the association between chronic health conditions and school achievement or attainment.

These seven studies were all affected by limitations (Table 2). Most commonly, the studies relied on self- or parent-reported measures of health or educational outcomes (or both) and so may have been affected by recall or social desirability bias in addition to selection and attrition bias inherent in longitudinal surveys. Only one study (of orofacial clefts) used measures of health and education not reported by participants or parents (44). This study instead used data from administrative health and education records linked to a national cleft registry (comparing children with cleft palate or cleft lip and palate with cleft lip only), thereby also limiting the risk of selection or attrition bias. However, this study was limited to children with orofacial clefts, and it did not include a non-symptomatic control group.

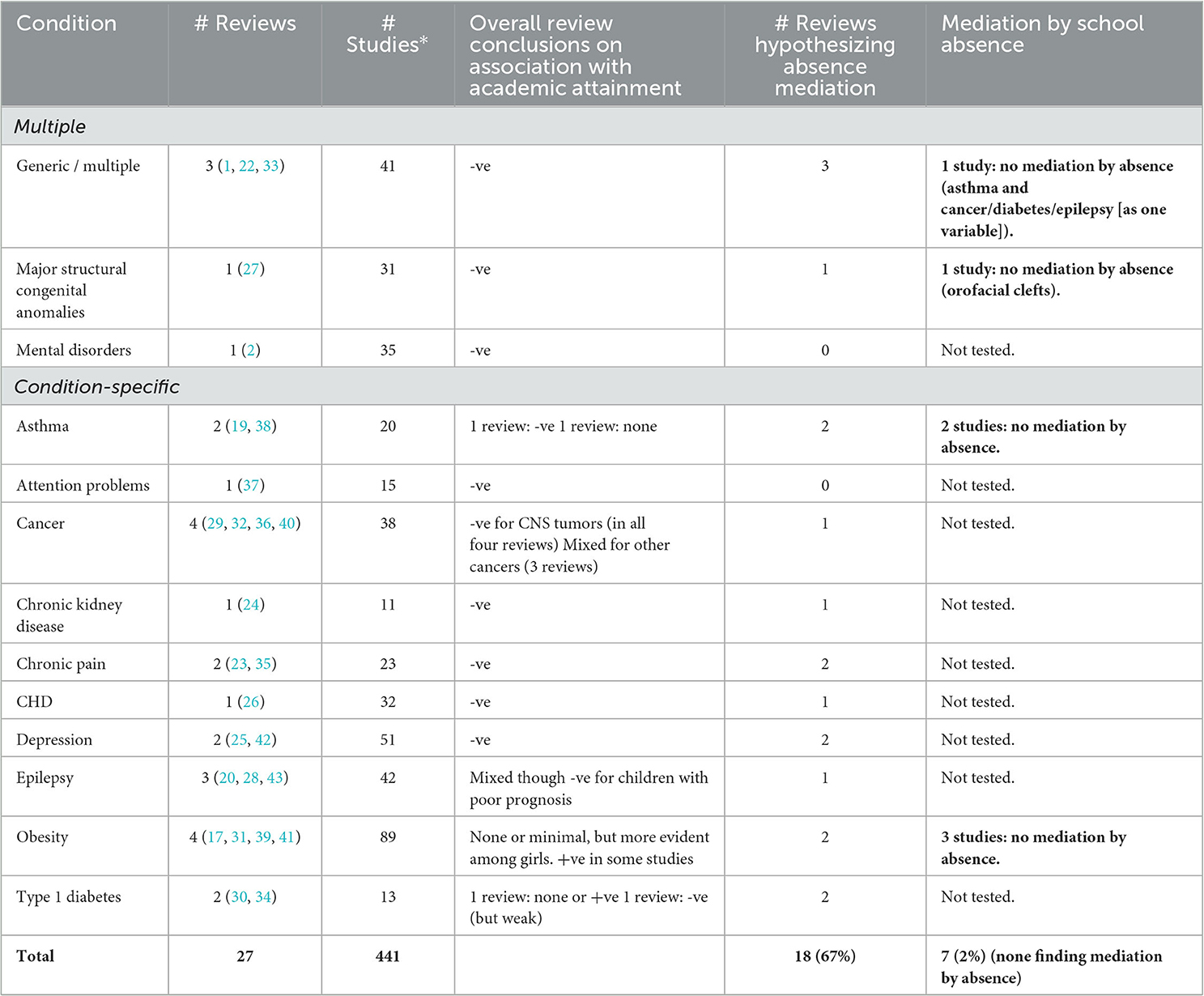

Details of other mediators hypothesized by review authors, many of which are condition-specific, are given in Table 3.

4. Discussion

We found evidence of strong associations between CHCs and educational attainment but a lack of evidence that this association is mediated by school absence. Our umbrella review of 27 systematic reviews (1, 2, 17, 19, 20, 22–43), covering 441 unique research studies of 7.5 million participants from 47 regions, found evidence that children with CHCs generally, or with major structural congenital anomalies, mental disorders, attention problems, central nervous system tumors, chronic kidney disease, chronic pain, congenital heart disease, and depression, were more likely than peers without the relevant CHCs to have lower academic attainment. Evidence for children with asthma, epilepsy, and obesity was mixed with studies finding either very weak associations with lower academic attainment, no associations, or even associations with higher academic attainment.

Only 7 of 441 studies (2%) empirically tested the hypothesis that absence from school is a mediator in this relationship (44–50). Of these seven, which included analyses of asthma, obesity, orofacial clefts, and cancer/diabetes/epilepsy (as one variable), none found any evidence that absence was a mediator. We, therefore, conclude that whereas there is strong evidence that a range of CHCs is associated with lower academic attainment, the hypothesized mediating pathway between CHCs, school absence, and academic attainment (Figure 1) currently has no strong empirical foundation in either direction.

The strengths of our umbrella review are the broad search and inclusion of a large number of studies. Although many of the reviews only included English-language studies, our finding that only 2% of 441 studies explored the extent to which absence mediates the association between CHCs and academic attainment shows a clear gap in the evidence about the mechanism through which CHCs might lead to lower attainment. A limitation is the varied types of comparator groups and varied adjustments for confounding factors. The wide range of conditions and study designs meant that meta-analysis was inappropriate; however, qualitatively, there were consistent findings on the associations between a range of CHCs (vs. none or different levels of CHC severity) and academic attainment. Additionally, our review did not aim to examine whether other possible mediators (such as those documented in Table 3) do in fact mediate the association between CHCs and academic attainment. Given the heterogeneous nature of the conditions under study, future CHC-specific studies will be required to further elucidate these factors.

Intervening to improve the educational outcomes of children with CHCs requires understanding the root causes of absence in these children, which likely differ between different CHCs and among children without CHCs. CHCs are very common, affecting up to 27% of young people in early adolescence (14). In England, absence from school is also common and, of all absences, the majority (73% in 2018/19) are authorized and, of these, 63% are due to either illness or needing to attend healthcare services (51). Among children with CHCs, the root causes of absence may relate to the condition itself, its management, or the need to attend healthcare appointments. There may be a common cause, for example, times of acute illness may prevent school attendance while also undermining cognitive function. School attendance and absence policies should therefore view absence as a potential health issue and respond flexibly, in accordance with equalities legislation, and provide sufficient resources to enable the affected young person to stay engaged with education both in and out of school.

The findings from this review have implications for policy and research. First, policies that solely target reductions in absence might not improve attainment and could be harmful to children with CHCs. However, operating different policies for children with and without CHCs would require asking questions of children and their parents about their health conditions. This could be experienced as intrusive and stigmatizing and undermine relationships with school staff. Identification of CHCs could also drive demand for unnecessary health investigations or evidence from medical staff, which could breach patient confidentiality. The implication for policy is that any efforts that address the common causes, whether rooted in health or social needs, may be more effective for increasing participation in school, in turn improving attainment and wellbeing, and avoid alienation and stress, particularly for children with CHCs.

More research is needed to identify potential interventions to support participation in education and attainment of children with CHCs. Studies using administrative data can help to plug the current evidence gap (52), including comparisons between jurisdictions with different approaches in schools and/or healthcare. There is an urgent need for randomized-controlled trials of interventions, developed with the input of children and young people and their families, within education and/or healthcare services, to identify approaches that promote child wellbeing and improve participation in education and attainment among children with CHCs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MJ designed the study to which all authors contributed and deduplicated the articles and carried out initial synthesis and article drafting to which all the authors contributed. MJ and DS-E carried out article eligibility assessment and data extraction as documented in the methods section of this manuscript. All the authors contributed to the manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health and Social Care Research (NIHR) through the Children and Families Policy Research Unit. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. RB is supported by a UK Research and Innovation Fellowship funded by grant MR/S003797/1 from the Medical Research Council.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1122769/full#supplementary-material

References

1. McKinley Yoder CL, Cantrell MA. Childhood Disability and educational outcomes: a systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. (2019) 45:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.01.003

2. Esch P, Bocquet V, Pull C, Couffignal S, Lehnert T, Graas M, et al. The downward spiral of mental disorders and educational attainment: a systematic review on early school leaving. BMC Psychiatry. (2014) 14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0237-4

3. Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch Dis Child. (2004) 89:938–42. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.045369

4. Lum A, Wakefield CE, Donnan B, Burns MA, Fardell JE, Marshall GM. Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: a systematic meta-review. Child Care Health Dev. (2017) 43:645–62. doi: 10.1111/cch.12475

5. Children's Commissioner. The Big Answer. (2022). Available online at: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/the-big-answer/ (accessed October 27, 2022)

6. Dalziel D, Henthorne K. Parents'/carers' Attitudes Towards School Attendance. (2005). Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/5548/1/RR618.pdf (accessed September 12, 2022).

7. Reid K. The views of head teachers and teachers on attendance issues in primary schools: Res Educ. (2004) 72:60–76. doi: 10.7227/RIE.72.5

8. Reid K. An evaluation of the views of secondary staff towards school attendance issues. Oxf Rev Educ. (2006) 32:303–24. doi: 10.1080/03054980600775557

9. Department for Education. School attendance: guidance for schools. (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-attendance (accessed February 17, 2020).

10. Ofsted. Securing Good Attendance and Tackling Persistent Absence. (2022). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/securing-good-attendance-and-tackling-persistent-absence/securing-good-attendance-and-tackling-persistent-absence (accessed September 12, 2022).

11. Children's Commissioner. Back Into School: New Insights Into School Absence. (2022). Available online at: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/cc-new-insights-into-school-absence.pdf (accessed October 27, 2022).

12. Department for Education. The Link Between Absence Attainment at KS2 KS4 2013/14 Academic Year. (2016). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/509679/The-link-between-absence-and-attainment-at-KS2-and-KS4-2013-to-2014-academic-year.pdf (accessed September 12, 2022).

13. Department for Education. Working Together to Improve School Attendance: Guidance for Maintained Schools, Academies, Independent Schools, Local Authorities. (2022). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-improve-school-attendance [Accessed November 22, 2022]

14. van Cleave J, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. Dynamics of obesity and chronic health conditions among children and youth. JAMA. (2010) 303:623–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.104

15. Sosu EM, Dare S, Goodfellow C, Klein M. Socioeconomic status and school absenteeism: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Rev. Educ. (2021) 9:e3291. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3291

16. Sirin SR. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review of research. Rev Educ Res. (2016) 75:417–53. doi: 10.3102/00346543075003417

17. Caird J, Kavanagh J, O'Mara-Eves A, Oliver K, Oliver S, Stansfield C, et al. Does being overweight impede academic attainment? A systematic review. Health Educ J. (2014) 73:497. doi: 10.1177/0017896913489289

18. Austin JK, Huberty TJ, Huster GA, Dunn DW. Academic achievement in children with epilepsy or asthma. Dev Med Child Neurol. (1998) 40:248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15457.x

19. Milton B, Whitehead M, Holland P, Hamilton V. The social and economic consequences of childhood asthma across the lifecourse: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. (2004) 30:711–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00486.x

20. Wo SW, Ong LC, Low WY, Lai PSM. The impact of epilepsy on academic achievement in children with normal intelligence and without major comorbidities: a systematic review. Epilepsy Res. (2017) 136:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.07.009

21. Fletcher JM. Adolescent depression: diagnosis, treatment, and educational attainment. Health Econ. (2008) 17:1215–35. doi: 10.1002/hec.1319

22. Hale DR, Bevilacqua L, Viner RM. Adolescent health and adult education and employment: a systematic review. Pediatrics. (2015) 136:128–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2105

23. Alsaggaf F, Fatimah C, Imelda AI, A. systematic review of the impact of chronic pain on adolescents' school functioning and school personnel responses to managing pain in the schools. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:2005–22. doi: 10.1111/jan.14404

24. Chen K, Didsbury M, van Zwieten A, Howell M, Kim S, Tong A, et al. Neurocognitive and educational outcomes in children and adolescents with CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2018) 13:387–97. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09650917

25. Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896

26. Cocomello L, Dimagli A, Biglino G, Cornish R, Caputo M, Lawlor DA. Educational attainment in patients with congenital heart disease: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2021) 21:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-02349-z

27. Glinianaia S, McLean A, Moffat M, Shenfine R, Armaroli A, Rankin J. Academic achievement and needs of school-aged children born with selected congenital anomalies: A systematic review and meta-analysis Birth Defects Res. (2021) 113:1431–62. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1961

28. Lah S, Castles A, Smith M. Reading in children with temporal lobe epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. (2017) 68:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.12.021

29. Langeveld NE, Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2002) 10:579–600. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0388-6

30. Milton B, Holland P, Whitehead M. The social and economic consequences of childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes mellitus across the lifecourse: a systematic review. Diabetic Medicine. (2006) 23:821–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01796.x

31. Martin A, Booth JN, McGeown S, Niven A, Sproule J, Saunders DH, et al. Longitudinal associations between childhood obesity and academic achievement: systematic review with focus group data. Curr Obes Rep. (2017) 6:297–313. doi: 10.1007/s13679-017-0272-9

32. Molcho M, D'Eath M, Alforque Thomas A, Sharp L. Educational attainment of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancer Med. (2019) 8:3182–95. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2154

33. Moser JJ, Veale PM, McAllister DL, Archer DP, A. systematic review and quantitative analysis of neurocognitive outcomes in children with four chronic illnesses. Paediatr Anaesth. (2013) 23:1084–96. doi: 10.1111/pan.12255

34. Oakley NJ, Gregory JW, Kneale D, Mann M, Hilliar M, Dayan C, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and educational attainment in childhood: A systematic review. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e033215. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033215

35. Ragnarsson S, Myleus A, Hurtig A-K, Sjoberg G, Rosvall P-A, Petersen S. Recurrent pain and academic achievement in school-aged children: a systematic review. J Sch Nurs. (2020) 36:61–78. doi: 10.1177/1059840519828057

36. Saatci D, Thomas A, Botting B, Sutcliffe A. Educational attainment in childhood cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 105:339–46. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317594

37. Polderman TJC, Boomsma DI, Bartels M, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC, A. systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2010) 122:271–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01568.x

38. Schneider T. Asthma and academic performance among children and youth in north america: a systematic review. J Sch Health. (2020) 90:319–42. doi: 10.1111/josh.12877

39. Santana CCA, Hill JO, Azevedo LB, Gunnarsdottir T, Prado WL. The association between obesity and academic performance in youth: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2017) 18:1191–9. doi: 10.1111/obr.12582

40. Schulte F, Kunin-Batson AS, Olson-Bullis BA, Banerjee P, Hocking MC, Janzen L, et al. Social attainment in survivors of pediatric central nervous system tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the Children's Oncology Group. J Cancer Surviv. (2019) 13:921–31. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00808-3

41. Segal AB, Huerta MC, Aurino E, Sassi F. The impact of childhood obesity on human capital in high-income countries: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. (2021) 22:e13104. doi: 10.1111/obr.13104

42. Wickersham A, Sugg HVR, Epstein S, Stewart R, Ford T, Downs J. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the association between child and adolescent depression and later educational attainment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 60:105–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.10.008

43. Puka K, Tavares TP, Speechley KN. Social outcomes for adults with a history of childhood-onset epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy and Behavior. (2019) 92:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.01.012

44. Fitzsimons KJ, Deacon SA, Copley LP, Park MH, Medina J, van der Meulen JH. School absence and achievement in children with isolated orofacial clefts. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:154–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319123

45. Veldwijk J, Fries MCE, Bemelmans WJE, Haveman-Nies A, Smit HA, Koppelman GH, et al. Overweight and school performance among primary school children: the PIAMA Birth cohort study. Obesity. (2012) 20:590–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.327

46. Sabia J. The effect of body weight on adolescent academic performance. South Econ J. (2007) 73:871–900. doi: 10.1002/j.2325-8012.2007.tb00809.x

47. Black N, Johnston DW, Peeters A. Childhood obesity and cognitive achievement. Health Econ. (2015) 24:1082–100. doi: 10.1002/hec.3211

48. Crump C, Rivera D, London R, Landau M, Erlendson B, Rodriguez E. Chronic health conditions and school performance among children and youth. Ann Epidemiol. (2013) 23:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.01.001

49. Kohen DE. Asthma and school functioning. Health Rep. (2010) 21:35–45. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2010004/article/11363-eng.pdf

50. Champaloux SW, Young DR. Childhood chronic health conditions and educational attainment: a social ecological approach. J Adol Health. (2015) 56:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.016

51. Department for Education. Pupil absence in schools in England: autumn 2018 spring 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england-autumn-2018-and-spring-2019 (accessed October 27, 2022).

52. UCL. Chronic health conditions, school absence and attainment. (2022). Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/children-policy-research/projects/chronic-health-conditions-school-absence-and-attainment (accessed November 7, 2022).

Keywords: chronic health conditions, school absence, academic attainment, academic achievement, mediation, meta-review

Citation: Jay MA, Sanders-Ellis D, Blackburn R, Deighton J and Gilbert R (2023) Umbrella systematic review finds limited evidence that school absence explains the association between chronic health conditions and lower academic attainment. Front. Public Health 11:1122769. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1122769

Received: 13 December 2022; Accepted: 12 May 2023;

Published: 09 June 2023.

Edited by:

Carolyn Gentle-Genitty, Indiana University Bloomington, United StatesReviewed by:

Gianluca Serafini, San Martino Hospital (IRCCS), ItalySaahoon Hong, Purdue University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Jay, Sanders-Ellis, Blackburn, Deighton and Gilbert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew A. Jay, bWF0dGhldy5qYXlAdWNsLmFjLnVr

Matthew A. Jay

Matthew A. Jay David Sanders-Ellis2

David Sanders-Ellis2