- Scientific Secretariat of the International Symposium on Surgical, Obstetric, and Anesthesia Systems Strengthening by 2030 in Africa, Mercy Ships Africa Office, Cotonou, Benin

Objective: This study aimed to engage African leaders and key stakeholders to commit themselves toward the strengthening of surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care systems by 2030 in Africa.

Methods: From research to a political commitment, a baseline assessment was performed to foster the identification of the gaps in surgical care as a first step of an inclusive process. The preliminary findings were discussed during the International Symposium on Surgical, Obstetric, and Anesthesia Systems Strengthening by 2030 in Africa. The conclusions served to draft the Dakar Declaration and its Regional Action Plan 2022–2030 to improve access to surgical care by 2030 in Africa, endorsed by Heads of State.

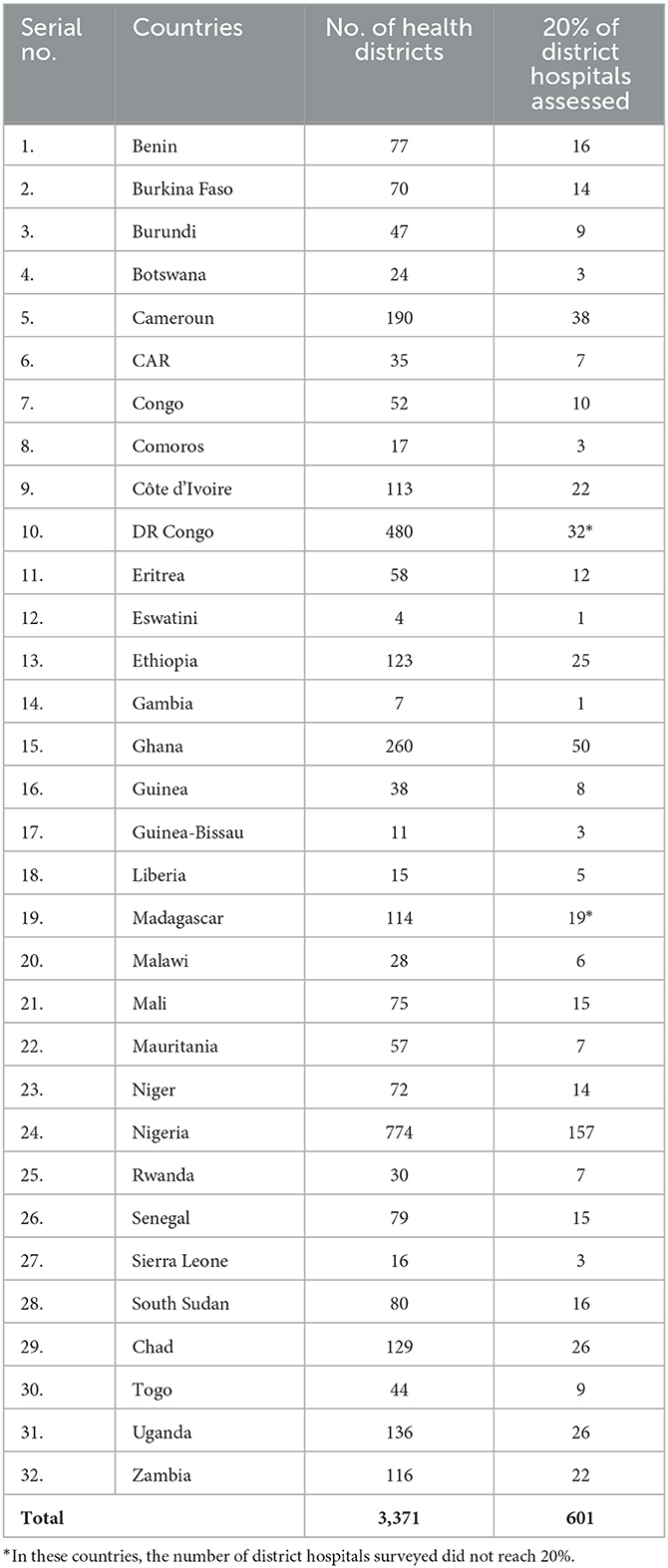

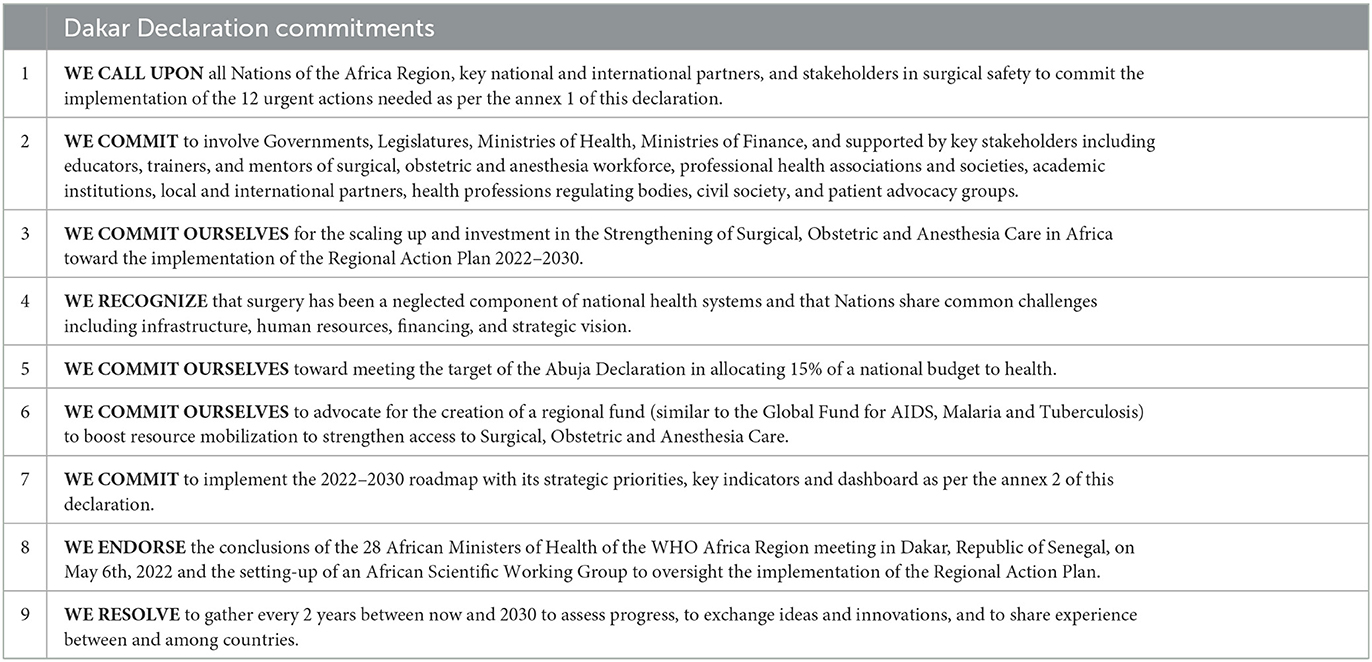

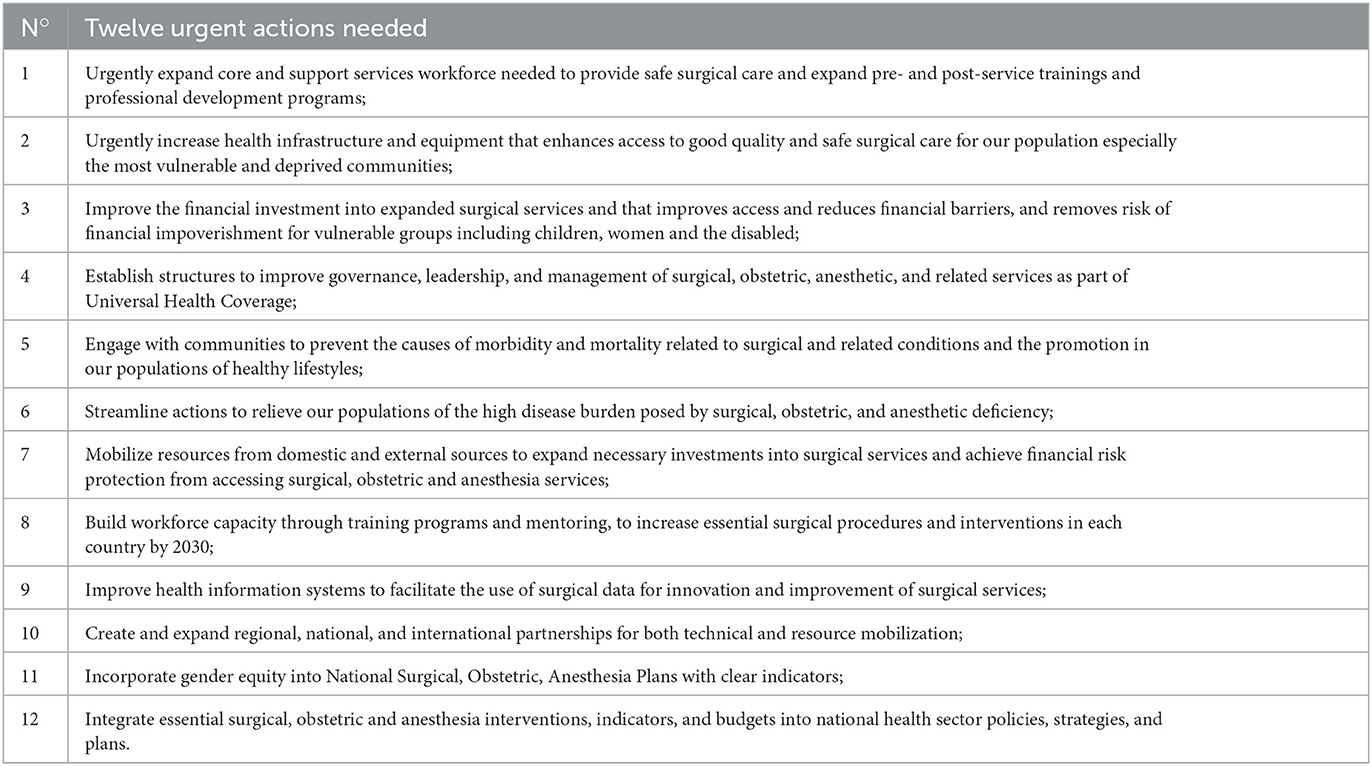

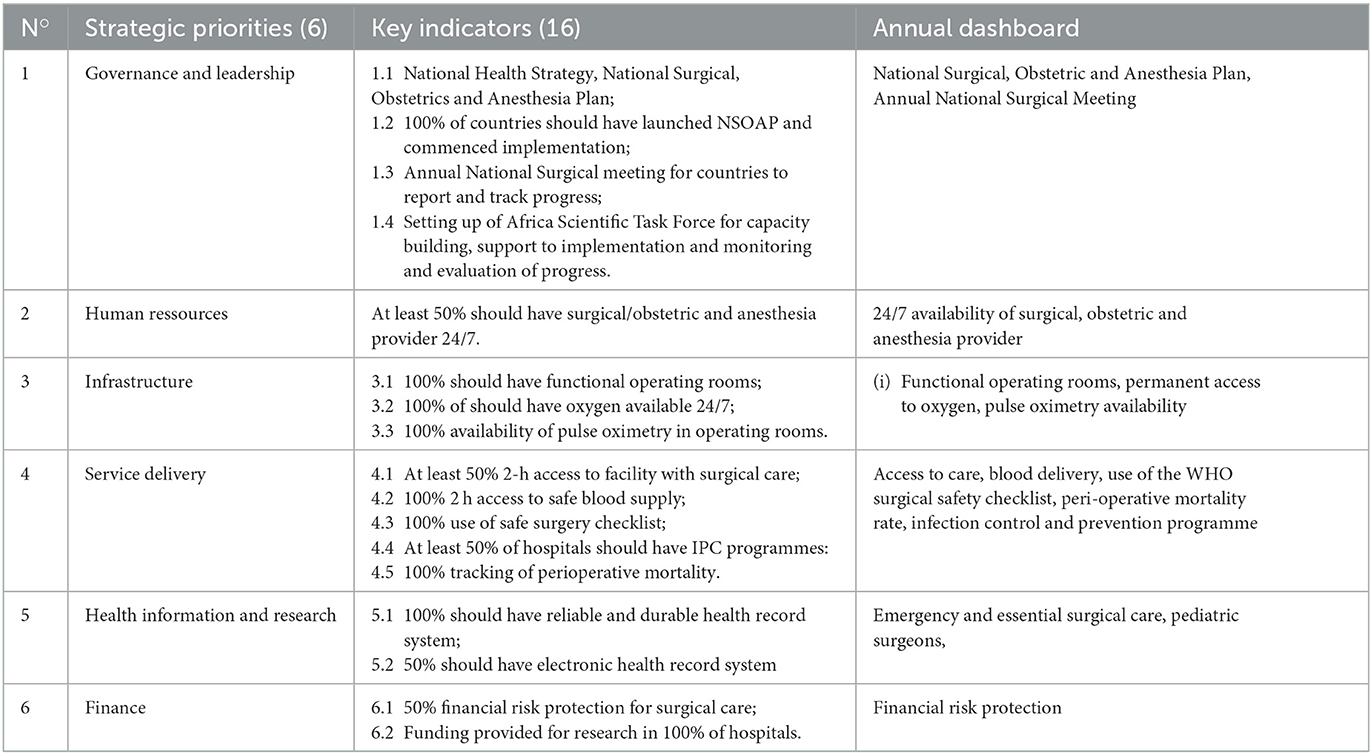

Results: The International Symposium was composed of two meetings that gathered (i) 85 scientific experts and (ii) 28 ministers of health or representatives from 28 sub-Saharan African countries. The 28 African countries represent (i) 51% of the continent's total population, (ii) 68% of the 47 African countries of the WHO Africa Region, (iii) 58% of all African Union countries, and (vi) 79% (3,371) of the WHO Africa Region's total (4,271) health districts. The International Symposium and the Heads of State Summit successfully produced the Dakar Declaration on access to equitable, affordable, and quality Surgical, Obstetric, and Anesthesia Care by 2030 in Africa and its Regional Actions Plan 2022–2030 which prioritizes 12 urgent actions needed to be implemented, six strategic priorities, 16 key indicators, and an annual dashboard to monitor progress.

Conclusion: The Dakar Declaration and its Regional Action Plan 2022–2030 are a commitment to establish quality and sustainable surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care in each African country within the ambitious framework of “The Africa we want” Agenda 2063.

Background

Over the past three decades, the African continent has made steady progress in improving public health, despite disparities between regions, countries, and within countries. Africa's exponential economic growth and development, and the additional significant contribution of global health initiatives, have facilitated this progress.

Some of the advancements in health include a 37% decline in mortality rates between 2000 and 2015 (1). Life expectancy has also grown by nearly 10 (46–56) years from 2009 to 2019 (2). However, Africa's overall performance still lags in other health indicators. These fragile gains, however, have not been matched with similar progress in health system strengthening, service integration, or hospital care, nor have they been equitably distributed among individuals of all socio-economic levels (3), mainly in the area of surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia (SOA) care.

Despite the efforts made by some Africa Union Member States with tangible achievements, the continent does not yet appear to be on track to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3: “Health for all and promotion of wellbeing for all at all ages.”

Africa alone bears 25% of the global burden of disease and one-third of the world's clinical conditions requiring emergency care and essential surgical, obstetric, and anesthetic services (EESOACSs). Despite having 17% of the world's population, the continent has only 2% of the world's doctors and 0.7 surgical specialists per 100,000 people (4).

Every year, 16.9 million people worldwide die due to lack of access to surgical care, and 93% of sub-Saharan Africa still lacks access (5). Surgery has been a neglected component of health care for people on the African continent. Equitable integration of surgical and anesthetic care remains one of the key challenges to strengthening health systems and achieving universal health coverage in Africa.

Over the years, the focus was mainly on infectious diseases, resulting in a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality from these conditions in some African countries (6).

On the occasion of the celebration of 30 years of Mercy Ships in Africa (1990/91–2021/22), Mercy Ships seized this opportunity to consolidate and strengthen its partnership with African countries and all national and international partners involved in strengthening surgical care and to mobilize policymakers and leaders to work together to integrate and scale up surgical care in national health development strategies.

Evidence has shown that investing in and strengthening surgical care within the existing healthcare system would lead to the overall strengthening and improvement of the entire healthcare system (7, 8).

As additional efforts were needed to strengthen the provision of safe, timely, and affordable emergency and essential surgical care and anesthesia, the World Health Assembly resolution 68.15 was made (9). Mercy Ships and the government of the Republic of Senegal launched a process to engage key stakeholders to commit themselves toward strengthening surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care systems by 2030 in Africa.

Methods

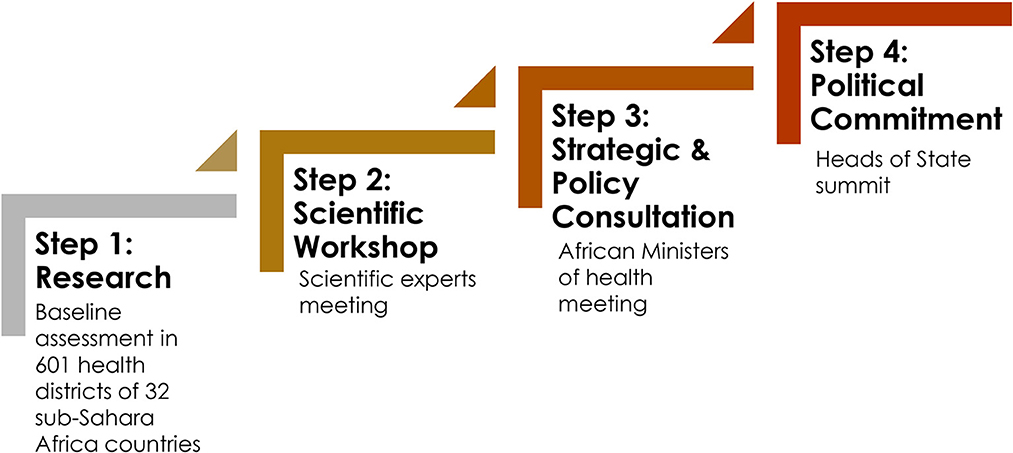

From research to political commitment, the WHO baseline assessment, which uses two simplified tools (country general information and district-hospital survey), is the first step in an inclusive process. Data were collected and analyzed using the Survey Monkey® platform. This was followed by a strategic analysis and guidance involving African experts and Ministers of Health gathered in an International Symposium. Six Heads of state then endorsed the Dakar Declaration and its Regional Action Plan to improve access to surgical care in Africa by 2030.

(i) The baseline assessment aimed to foster the identification of the gaps in surgical care. The assessment was conducted in 6 months (January–July 2022) in 601 district hospitals (Table 1) in 32 sub-Saharan African countries (Figure 1) and performed by more than 600 national investigators and coordinators from the Ministry of Health at the national level and investigators at the district-hospital level. As in similar studies or surveys, refereeing the AFRO guidelines, the sample size was set at 20% of the total number of health districts for each selected country (10). The health districts were selected from all the regions of the country to ensure representative geographical coverage with a convenient sample of 20% of district hospitals in each country. In three countries (D R Congo, Madagascar, and Botswana), the district hospitals surveyed did not reach 20% because of security issues and flooding as well as incomplete data.

Data were collected in the following areas: infrastructure, human resources, service delivery, information management, finance, impact of COVID-19 on surgery, governance, and leadership and children's surgery and uploaded into the survey monkey platform. The survey was pretested in two countries before final deployment. (ii) The International Symposium (IS) was organized by the Government of Senegal and Mercy Ships in close collaboration with the WHO Regional Office for Africa and in partnership with various international and regional organizations and African key actors of the health sector at all levels. The IS gathered participants from 28 African countries, namely, Benin, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Comoros, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Eswatini, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Malawi, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Uganda, and Togo (Figure 1), and Somaliland as an observer and was held in two phases: (a) The Experts Meeting identified and agreed on the key findings of the baseline assessment, formulated priority recommendations, proposed a roadmap 2022–2030 for scaling up and investing in the strengthening of surgical, obstetric, anesthesia, and nursing care in Africa, and developed a draft Declaration of commitment that was submitted to the Ministers of Health meeting. (b) The African Ministers of Health discussed and adopted a Declaration of commitment to access to equitable, affordable, and quality surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care in Africa, as well as a draft Regional Action Plan 2022–2030, a roadmap for the scale-up and investment in the strengthening of surgical, obstetric, anesthesia, and nursing care in Africa by 2030, including a monitoring and evaluation plan. (iii) On 30 May 2022 in Dakar, Senegal, the Heads of State Summit of six countries (Cameroon, Congo, Comoros, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Senegal) endorsed the Dakar Declaration on Access to Equitable, Affordable, and Quality Surgical, Obstetric, and Anesthesia Care in Africa by 2030, commonly referred to as “The Dakar Declaration,” and its Regional Action Plan 2022–2030 (Figure 2). President of Senegal, Macky Sall, and current Chairperson of the African Union will submit the Dakar Declaration to the African Union Heads of States ordinary summit in February 2023.

Results

The preliminary findings of the baseline assessment show that the surgical care and national health systems in the majority of the countries assessed are disorganized, weak, and fragile. Few countries have created “National Surgical, Obstetric, Anesthesia and Nursing Plans (NSOAPs)” to guide and strengthen surgical care, and most of Africa remains underserved in terms of surgical care. The baseline assessment identified the ongoing challenges to universal health coverage from deficiencies in surgical, obstetric, anesthetic, and related care due to (1) workforce deficits in the core human resources needed for surgical services, (2) significant infrastructure and equipment deficits and disparity within countries, (3) lack of service delivery due to weaknesses in the core and support services required to deliver safe, surgical care, (4) challenges of financing surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia services as part of national health strategies, (5) lack of regulation and governance structures for surgical care at all levels, (6) information, (7) inadequate health promotion and prevention efforts on the causes of morbidity and mortality from surgical and related conditions, and (8) lack of leadership and management of surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care. The Dakar Declaration contains nine key commitments (Table 2). The Regional Action Plan 2022–2030, the result of the political commitment, is an 8-year workplan for all African countries to upgrade their surgical care system by 2030. The Regional Action Plan prioritizes 12 urgent actions (Table 3), six strategic priorities, 16 key indicators, and an annual dashboard to monitor progress (Table 4).

Discussion

The current focus on health systems and service delivery is not aligned with an effective policy response in Africa (7, 11). Many priorities are still partner-driven, with limited policy or institutional buy-in. The verticalization of the efforts predominates, both for health services and health system strengthening initiatives, with limited linkages within and across the different areas. The main consequence being a fragmented service delivery without guarantee of the availability of essential services.

There is also a weak emphasis on an integrated approach to the system-strengthening efforts, which leads to duplications and, in some cases, underinvestment in critical elements needed for effective service provision.

In this context, effective leadership has paramount importance to manage new change initiatives and implement national reforms within the health sectors. Leaders have a key role to facilitate mechanisms for making policies, managing the sector, and producing as well as accounting for results from health interventions in the six building blocks of the health systems as defined by the WHO. In those conditions, the health governance area represents a scope of actions across all domains providing policies, standards, regulations, and guidance to control the use of resources and the functioning of health systems (12).

Taking forward the implementation of multiple commitments made at regional and international levels is challenging in Africa, as countries are complex and exhibit wide variations in their system focus, design, and performance. For example, the Abuja Declaration made in 2001 which aims to dedicate 15% of the national budget to the health sector is implemented only by a few African countries (13, 14). The main consequence being a fragmented service delivery without a guarantee of the availability of essential services. Therefore, the Abuja Declaration is still necessary for the successful implementation of the Dakar Declaration to upgrade and scale up all needed interventions to build strong and resilient national health systems.

The Dakar Declaration is a joint initiative bringing together the government of Senegal and Mercy Ships with the participation of key regional and international partners involved in the surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care system strengthening in Africa.

Conclusion

To solve the current surgical care crisis, African leaders must commit to significant and focused efforts to improve the availability, quality, and affordability of surgery in the continent and then within their countries.

These efforts should be supervised by heads of state and implemented by the ministries of health in close collaboration with relevant stakeholders, including, but not limited to, the private sector, the non-governmental sector, professional organizations, and not-for-profit sectors. The culmination of the efforts needed has led to a Regional Action Plan (RAP) 2022–2030 and then to national surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia plan (NSOAP) as part of the National Health Plan (NHP). Both the Regional Action Plan and the NSOAPs will guide the integration at regional and national levels into the Africa Health Strategy 2016–2030 and into the national health policy, strategy, or plan, as there is now global and regional recognition that health systems planning is incomplete if the surgical system is left unaddressed. The Dakar Declaration and its Regional Action Plan, therefore, are a commitment as a clear pathway to building quality and sustainable surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia systems in Africa and in each country within the ambitious framework of “The Africa we want” Agenda 2063 (13). In the era of the Declaration of Astana on PHC for UHC and SDGs (October 2018), the surgical service should be an integral part of its first component, which is “integrated packages of quality services and considering essential public health functions” (15). The definition of essential service packages should also include surgical services so that the health system can respond easily to the needs of the communities. As a reminder, “The Africa we want” is a shared framework for inclusive growth and sustainable development for Africa to be realized in the next 50 years. It is a continuation of the Pan-African drive over centuries, for unity, self-determination, freedom, progress, and collective prosperity pursued under the African Renaissance.

Author contributions

PM'p, JS-O, TE, JL, DD, and EA contributed to the conception, writing, and final approval of the manuscript for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mercy Ships for the funding of the entire process from the baseline assessment to the Dakar Declaration. Mercy Ships, an international non-governmental organization, uses hospital ships to provide free surgeries to transform lives and serve nations. Our special thanks to the WHO Regional Office for Africa, International NGO Smile Train, Program Global Health Surgery and Social Change Harvard University Medical School Cambridge, West African College of Surgeons, College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa, McGill University, International Organization Lifebox, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, South African Development Community Regional Collaboration Center for Surgical Healthcare, G4 Alliance for Surgical, Obstetric, Trauma and Anesthesia, Johnson and Johnson, and Royal College of Surgeons of England. Partners have committed to sustaining their technical, strategic, and funding support in the implementation of the Regional Action Plan 2022–2030.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization Africa. Atlas of African Health Statistics 2014: Health Situation Analysis of the African Region, Brazzaville. (2022). p. 205. Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-african-health-statistics-2014-health-situation-analysis-african-region (accessed October 25, 2022).

2. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Région Africaine. Suivi de la Couverture Sanitaire Universelle dans la région Africaine. (2022). p. 54.

3. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:e1196–252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

4. WHO Africa. The State of Health in the WHO African Region, Where We Are, Where We Need to Go, 2018: ISBN 978-929023409-8. (2018). Available online at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo~

5. Mullapudi B, Grabski D, Ameh E, Ozgediz D, Thangarajah H, Kling K, et al. Estimates of number of children and adolescents without access to surgical care. Bull World Health Organ. (2019) 97:254–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.216028

6. Murray CJL, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, Lim SS, Wolock TM, Roberts DA, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. (2014) 384:1005–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60844-8

7. Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. (2015) 386:569–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X

8. Christie SA, Nwomeh BC, Krishnaswami S, Yang GP, Holterman A-XL, Charles A, et al. Strengthening surgery strengthens health systems: A new paradigm and potential pathway for horizontal development in low- and middle-income countries. World J Surg. (2019) 43:736–43. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4854-9

9. World Health Assembly. Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anaesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization; (2015). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_R15-en.pdf (accessed December 9, 2020).

10. Sambo LG, Shatora RR, Goosen ESM. Tools for Assessing the Functionality of the Health Districts System. Available online at: https://1library.net/title/tools-assessing-operationality-district-health-systems (accessed October 25, 2022).

11. M'Pele P. Résultats préliminaires d'une évaluation de base des insuffisances pour l'accès aux soins chirurgicaux, obstétricaux et anesthésiques dans 32 pays en Afrique sub-saharienne. (2022).

12. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Rapport sur la santé dans le monde: financement d'une couverture universelle. (2010). p. 120.

13. Africa Union Commission. Agenda 2063, the Africa We Want, 2015 Background Note 01, ISBN: 978-92-95 104-23-5. (2015). p. 22.

14. World Health Organization. The Abuja Declaration: Ten Years On. Geneva. (2011). Available online at: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/Abuja_declaration/en/ (accessed October 25, 2022).

15. World Health Organization. Declaration of Astana: Global Conference on Primary Health Care: Astana, Kazakhstan. (2018). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328123/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.61-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed October 25, 2022).

Keywords: Africa surgical initiative, safe surgery, safe anesthesia, Dakar Declaration, Regional Action Plan

Citation: M'pele P, Seyi-Olajide JO, Elongo T, Lemvik J, Dovlo D and Ameh EA (2023) From research to a political commitment to strengthen access to surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia care in Africa by 2030. Front. Public Health 11:1168805. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1168805

Received: 21 February 2023; Accepted: 03 April 2023;

Published: 16 May 2023.

Edited by:

Ahmed Mohammed Alwan, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Hasaneen Kudhair Albadry, Alkut College University/Pharma Department, IraqHasanain A. J. Gharban, University of Wasit, Iraq

Copyright © 2023 M'pele, Seyi-Olajide, Elongo, Lemvik, Dovlo and Ameh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pierre M'pele, cGllcnJlbXBlbGVAeWFob28uY29t

Pierre M'pele*

Pierre M'pele* Tarcisse Elongo

Tarcisse Elongo Delanyo Dovlo

Delanyo Dovlo Emmanuel A. Ameh

Emmanuel A. Ameh