- 1Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

- 2Military Medical Academy, Belgrade, Serbia

- 3Antidoping Agency of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia

- 4University Clinical Center of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia

- 5Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

- 6Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Management, Singidunum University, Belgrade, Serbia

- 7Faculty of Medicine of the Military Medical Academy, University of Defence, Belgrade, Serbia

- 8Faculty of Sport, University “Union - Nikola Tesla”, Belgrade, Serbia

Objectives: The aim of this study was to examine the impact of anti-doping education among professional athletes on anti-doping knowledge.

Methods: A prospective cohort study was conducted on differences in knowledge toward doping among 404 professional athletes in relation to their education about doping.

Results: Participants who underwent education answered correctly significantly more often on most of the questions compared to participants without education [difference of about 20–30% in the rate of correct answers is in favor of participants with education on every question; 8.49 (SD 2.75) vs. 11.04 (SD 1.89); p < 0.001]. The majority of participants in the group with prior education against doping answered 10 or more questions correctly out of a total of 13, while the group without prior education against doping most commonly had 7 to 11 correct answers (p < 0.001). The most significant predictors of correct answers are gender, number of years of training, type of sport (individual or team sport), and prior education about doping. The largest contribution to this model comes from the variable “prior education against doping,” followed by the type of sport.

Conclusion: Our research shows that prior anti-doping education is effective and has the essential contribution on athletes’ knowledge about doping.

Highlights

• Prior anti-doping education is effective and has the essential contribution on athletes’ knowledge about doping.

• Participants who underwent anti-doping education answered correctly significantly more often on most of the questions compared to participants without education.

• More efforts should be made in the future to educate male athletes, as well as athletes in team sports, as they have shown less knowledge about doping.

Introduction

Anti-doping education has become a critical component in the fight against doping in sports, as it aims to inform athletes about the risks and consequences of doping and to foster a clean sports environment. Effective educational programs are crucial in shaping athletes’ attitudes and behaviors toward anti-doping compliance. A growing body of research emphasizes the role of education in enhancing athletes’ knowledge and decision-making processes, as well as its potential to reduce doping violations. According to Listiani et al. (1), a systematic review that aims to review athletes’ knowledge of doping in sports to provide a foundation for evaluating anti-doping measures, particularly related to anti-doping education, demonstrated that athletes could have different level of understanding regarding anti-doping and highlighted importance of comprehensive anti-doping information (1). This work highlights the importance of further research to evaluate anti-doping education programs by assessing athletes’ knowledge as a crucial step toward enhancing the effectiveness of these programs and ensuring they are responsive to the evolving landscape of sports doping.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) (2) put education in a central focus of their anti-doping strategy. In its efforts to put education as a critical component in the fight against doping WADA developed Anti-Doping Education and Learning Platform (ADEL) (3), centralized platform offering educational solutions for athletes, athlete support personnel, Anti-Doping Organization (ADO) practitioners, researchers, and other members of the clean sport community (4).

All substances or methods included on the WADA prohibited list (The Prohibited List) meet at least two of the following three criteria: it improves or has the potential to improve sport performance; it poses a real or potential health risk to the athlete; and it violates the spirit of sport; as described in the 2021 World Anti-Doping Code (the Code) (5). The Prohibited List is a mandatory International Standard as part of the World Anti-Doping Program. The aim of the World Anti-Doping Program and the Code is to protect athletes’ right to participate in sports free from doping, thus promoting health, fair play, and equality among athletes worldwide (5, 6). Moreover, it seeks to ensure coordinated, effective, and harmonized anti-doping initiatives at both the international and national levels, focusing on detection, dettering and prevention of doping. In recent years, doping in sports has increasingly attracted the attention of medical, physiological, and scientific researchers (7). According to Gucciardi and colleagues (8), while medical and physiological researchers focus on improving detection methods (such as blood, urine, and gene tests) for the use of banned substances among athletes (9) researchers in the social sciences aim to better understand the psychosocial factors (such as attitudes, social environment, and beliefs) that may be critical for developing educational programs aimed at preventing such behavior (10).

Elite athletes are often reluctant to discuss the topic of doping with researchers, even when anonymity and confidentiality are guaranteed (11). This reluctance stems from the fact that they are asked to admit behaviors that could potentially jeopardize their careers (12). Nevertheless, in recent years, there has been a significant increase in research focusing on the attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge of elite athletes regarding doping and anti-doping regulations. However, most of these studies concentrate on athletes from Western countries (7, 13–15), while research involving athletes from Serbia remains relatively scarce.

While testing and research play a central and prominent role in WADA’s anti-doping strategy, its educational program is considered crucial for developing a lasting anti-doping culture in elite sports (3). Athletes are becoming more familiar with anti-doping rules, but there is still a noticeable lack of knowledge that should be addressed through appropriate programs.

The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) / Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior (KAB) model was first developed in the 1950s. This model has been widely used in health education as a framework for understanding the mechanisms that influence changes in patients’ behavior and their health outcomes (16, 17). Since the 1990s, this research framework has been applied in the field of anti-doping (18). Findings from multiple studies consistently indicate that athletes’ positive attitudes toward doping are a significant predictor of increased susceptibility to its use. Athletes who express tolerant or justificatory views toward doping are considerably more likely to engage in risky behavior associated with the use of prohibited substances. (19–25). Furthermore, health concerns play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward doping (7). Awareness of the often negative health consequences of doping can contribute to the development of negative attitudes toward its use (26). At the same time, questions have arisen regarding the relationship between knowledge and behavior. Most anti-doping educational programs have a positive impact on increasing knowledge about doping, as well as shaping attitudes toward doping and reducing the likelihood of its use (18, 27).

The aim of this study was to examine the impact of anti-doping education among professional athletes on anti-doping knowledge.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted on differences in knowledge toward doping among professional athletes in relation to their education against doping. A total of 404 participants (or 96.65% of 418 potential participants who had to complete anti-doping education) took part in the study. The participants were recruited among scholarship athletes of The Athletics Federation of Serbia who must undergo mandatory anti-doping education.

The International Standard for Education 2021 (the ISE 2021) (2) defines high-priority groups (Registered Testing Pool (RTP) athletes and sanctioned athletes) as mandatory groups for education in the educational plan. In addition to the requirements of the International Standard, Anti-doping agency of Serbia (ADAS) defines additional mandatory groups for education in educational plan, according to Serbian national regulations. According to national regulations, athletes who receive national or city scholarships are required to pass two anti-doping educations during the financial year. Therefore, ADAS defines these groups of athletes as a high-priority group for whom anti-doping education is mandatory.

As in every year, ADAS conducted two anti-doping educations for scholarship athletes of The Athletics Federation of Serbia. The first anti-doping education was in the form of an electronic education, while the second was in person. The questionnaire, which is the subject of this research, was part of the first mandatory anti-doping education for scholarship athletes in 2023. Before the anti-doping education as the 30-min video form material, athletes were voluntarily able to fill out an anonymous survey. Anti-doping educational 30-min video material covered mandatory topics following the ISE 2021 requirements. Before listening to the video material, athletes had the opportunity to access the anti-doping questionnaire. Some athletes had the opportunity to complete anti-doping education earlier in their careers, while for a certain percentage of athletes the video material was their first anti-doping education. Athletes filled out the anonymous survey on the Moodle platform.

Based on the previous anti-doping education of the subjects, all subjects were divided into two groups: group with prior education against doping and group without prior education against doping.

The period for completing the questionnaire was from June 2023 to November 2023. Participation in this study was entirely voluntary. Completing the questionnaire indicated that the participant had given consent to participate in the research. It was emphasized that that the data collected from the study would be used solely for research purposes. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by Ethical Committee of the Anti-Doping Agency of Serbia (No decision 2025/1/1 on 22/04/2025; No administrative: 23–0422-2 on 22/04/2025).

The survey instrument was a structured questionnaire consisting of two sets of questions. The first set of questions collected sociodemographic data, such as gender, age, years of training, number of hours of weekly training, number of doping controls, level of education, level of competition, and type of sport (individual or team sport). The second set of questions analyzed the participants’ knowledge about doping through a questionnaire consisting of 13 questions.

The questionnaire used to measure knowledge created ad hoc. The internal consistency of the scale for the whole sample was α = 0.829 (good of reliability level). When looking at the Item-total Statistics, it can be seen that after deleting each of the 13 questions, Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.809 to 0.849.

The data were statistically processed using IBM SPSS, with the determination of measures of central tendency and variability. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test, Chi-square test, Student’s t-test for two independent samples, Spearman’s correlation analysis, and multivariate regression analysis were used to determine the statistical significance of the data at the p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 404 participants took part in the study (160 women or 39.6%, 242 men or 59.9%, while two did not specify their gender – 0.5%). The average age of all participants was 22 years (IQR 19–26 years). Of all the participants, 82.2% or 332 had undergone education about doping, while only 72 or 17.8% had not received any form of education against doping.

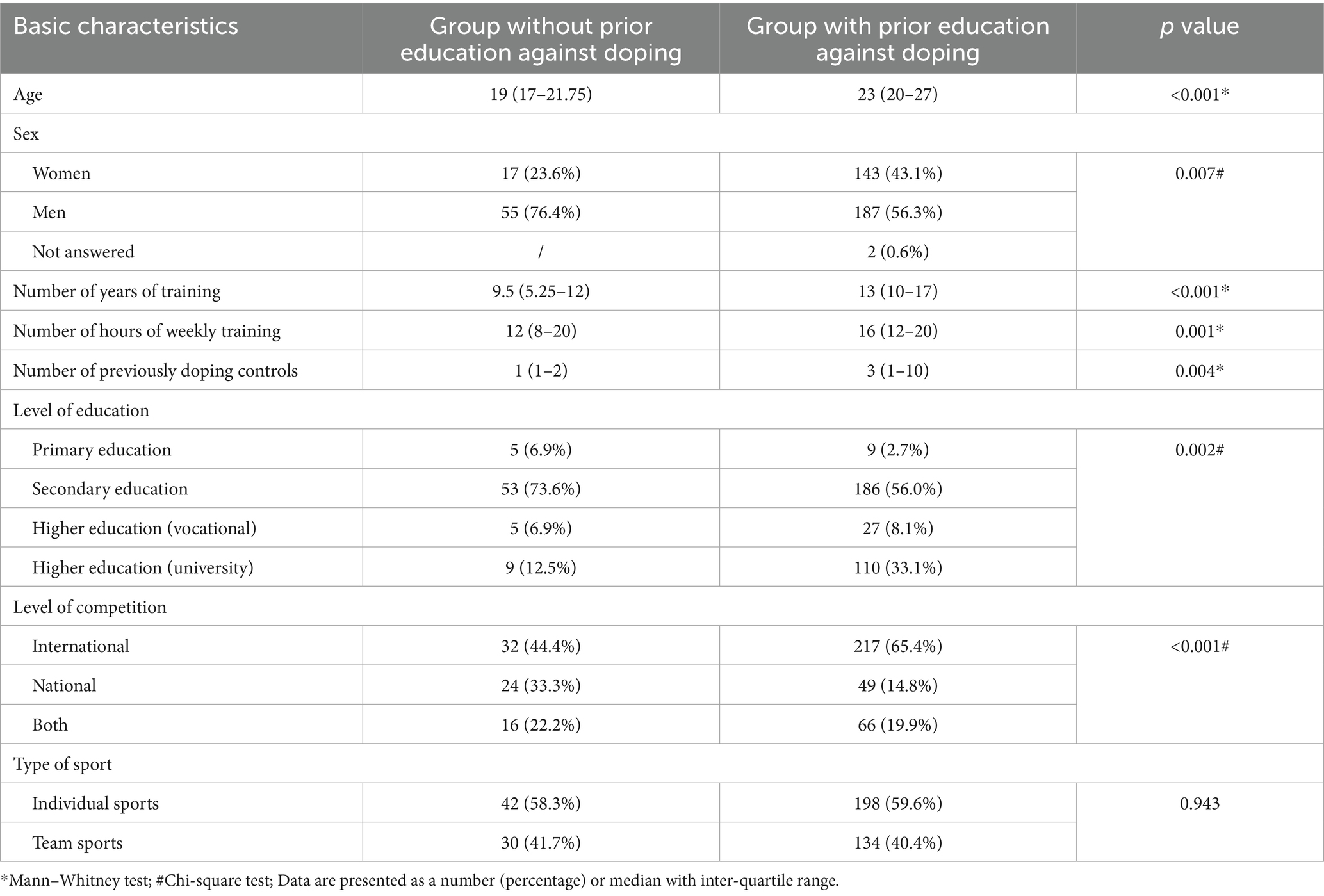

The group of participants with prior education against doping was statistically significantly older than those who had not undergone education (median: 23 vs. 19; Table 1). There were significantly more women in the group with prior education against doping (43% vs. 23%). The participants who had underwent anti-doping education had significantly longer training periods and more hours spent on weekly training. They also had significantly more doping controls compared to those who had not received education against doping (average number of previous controls 3 vs. 1). Interestingly, in the group without prior education against doping, the majority of participants had a high school education (73.6%), while in the group with prior education against doping, there were significantly fewer with a high school education (56%). Those who had some form of education against doping participated more frequently in international competitions compared to those without prior anti-doping education (65.4% vs. 44.4%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and basic information about training and competition of participants depending on prior education against doping.

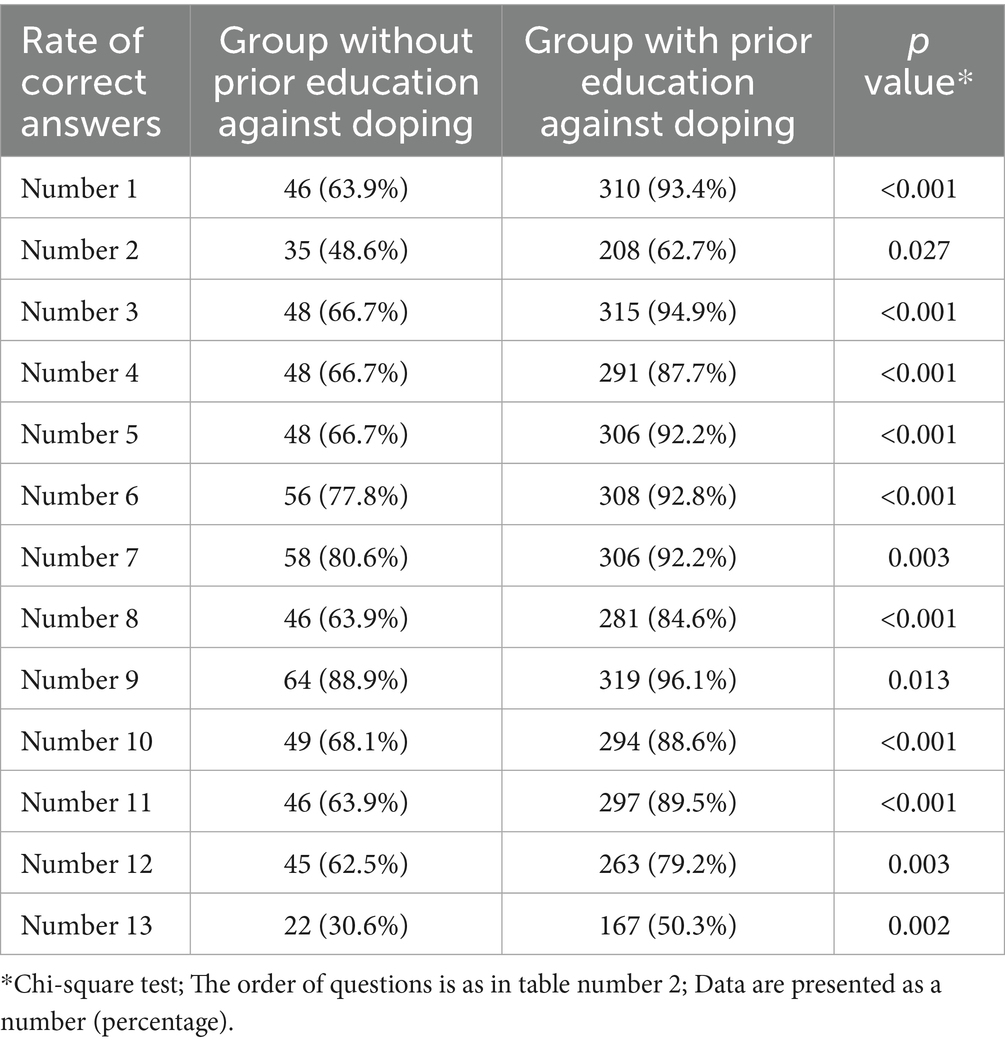

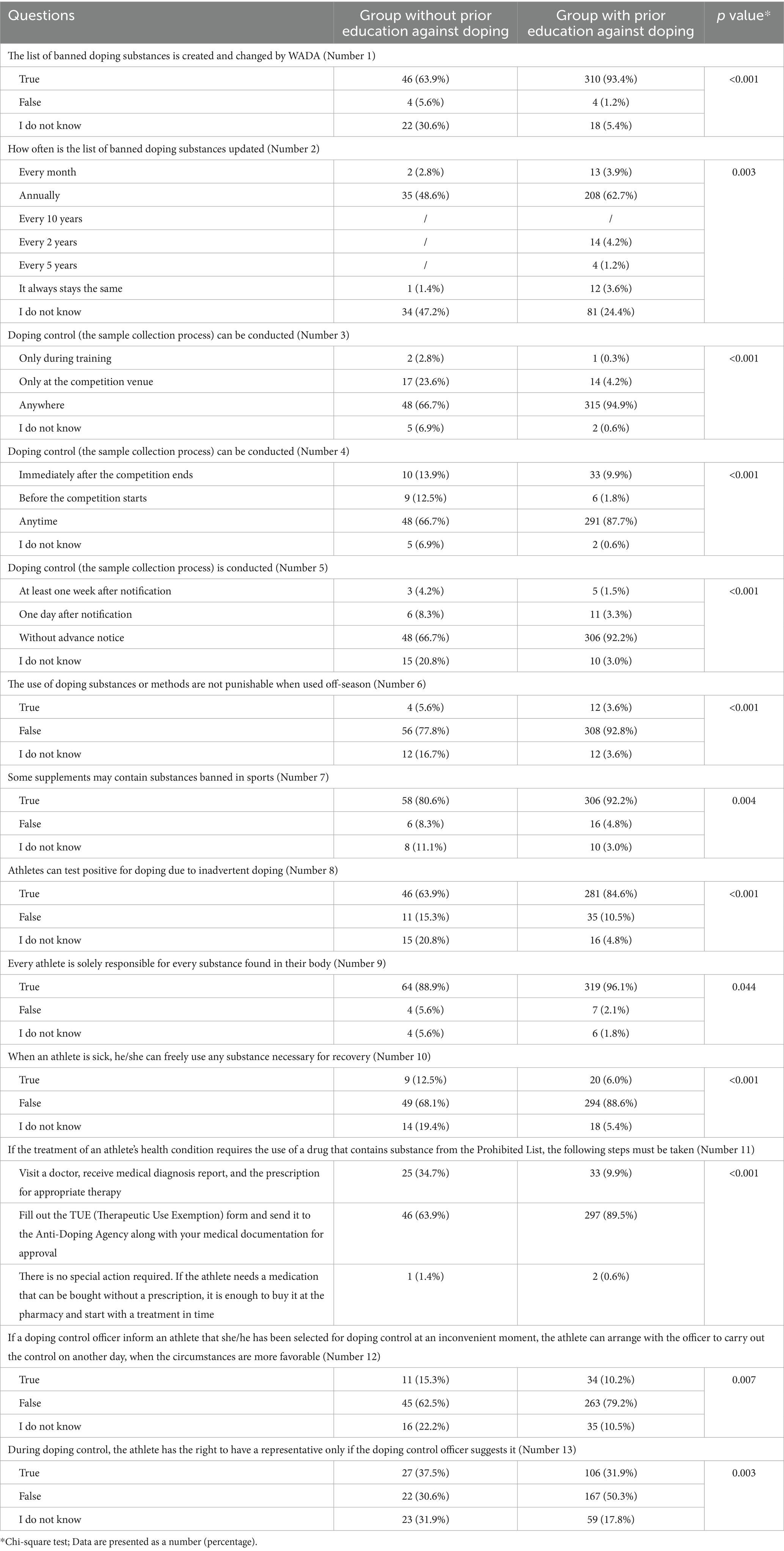

If we analyze the participants’ knowledge about doping in relation to whether they had education against doping or not (Table 2), we can see that participants who underwent education answered correctly significantly more often on most of the questions compared to participants without education. Table 3 shows the rate of correct answers, and it can be observed that the difference in the rate of correct answers is in favor of participants with education on every question, with a difference of about 20–30%. The exception is the last question, “During doping control, does the athlete have the right to have a representative only if the doping control officer suggests it?,” where the low rate of correct answers among participants without anti-doping education is 30.6%, but also among participants with education (50.3%).

Table 2. Participants’ knowledge through a 13-question questionnaire depending on prior education against doping.

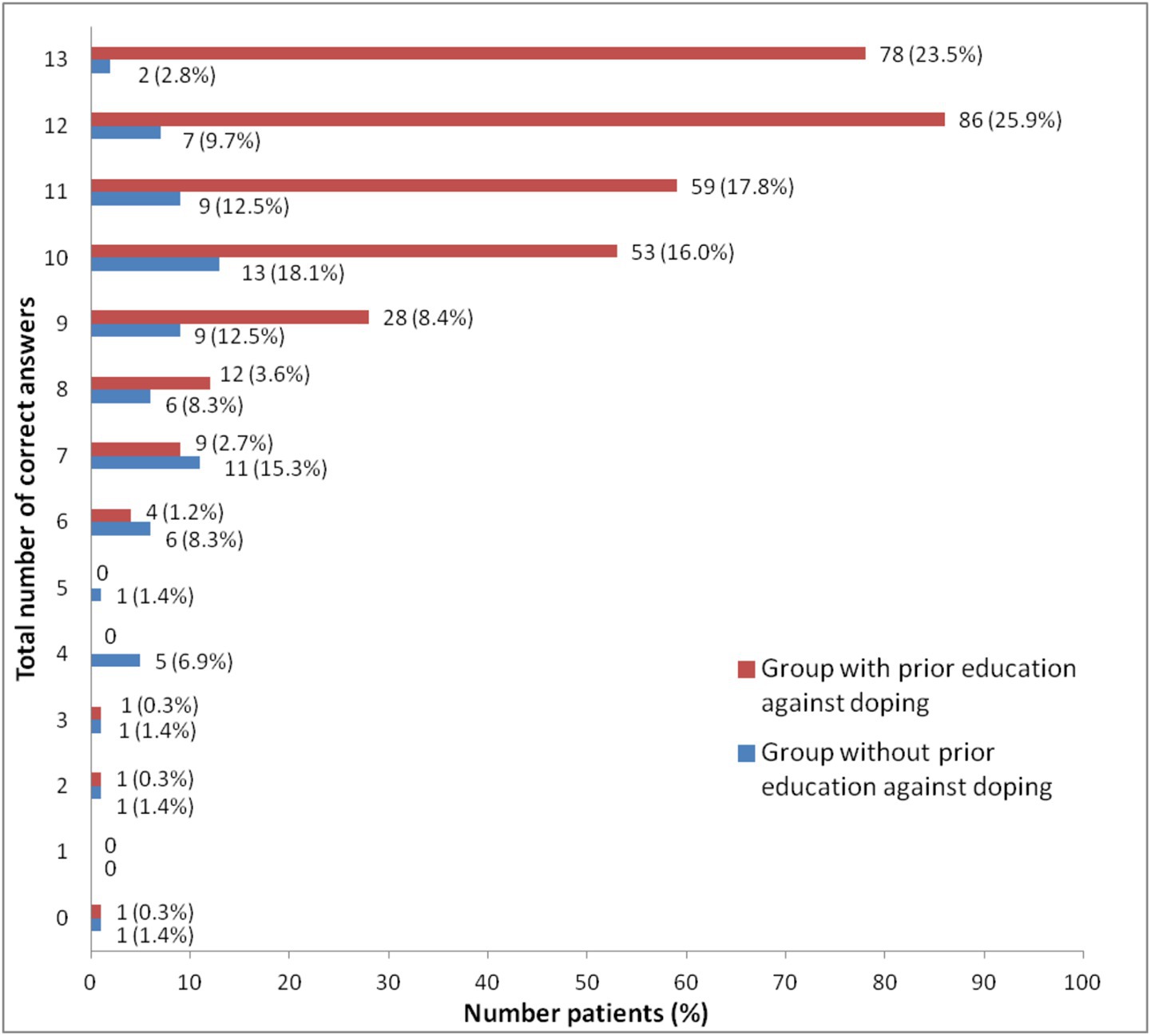

The average total number of correct answers per participant was 8.49 (SD 2.75) for the group without education, while for the group with education, it was 11.04 (SD 1.89), which is a statistically significant difference (Independent Samples Test; p < 0.001). The majority of participants in the group with prior education against doping answered 10 or more questions correctly out of a total of 13, while the group without prior education against doping most commonly had 7 to 11 correct answers (Chi-square test, p < 0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution based on the total number of correct answers. Chi-square test, p < 0.001; data are presented as a number (percentage).

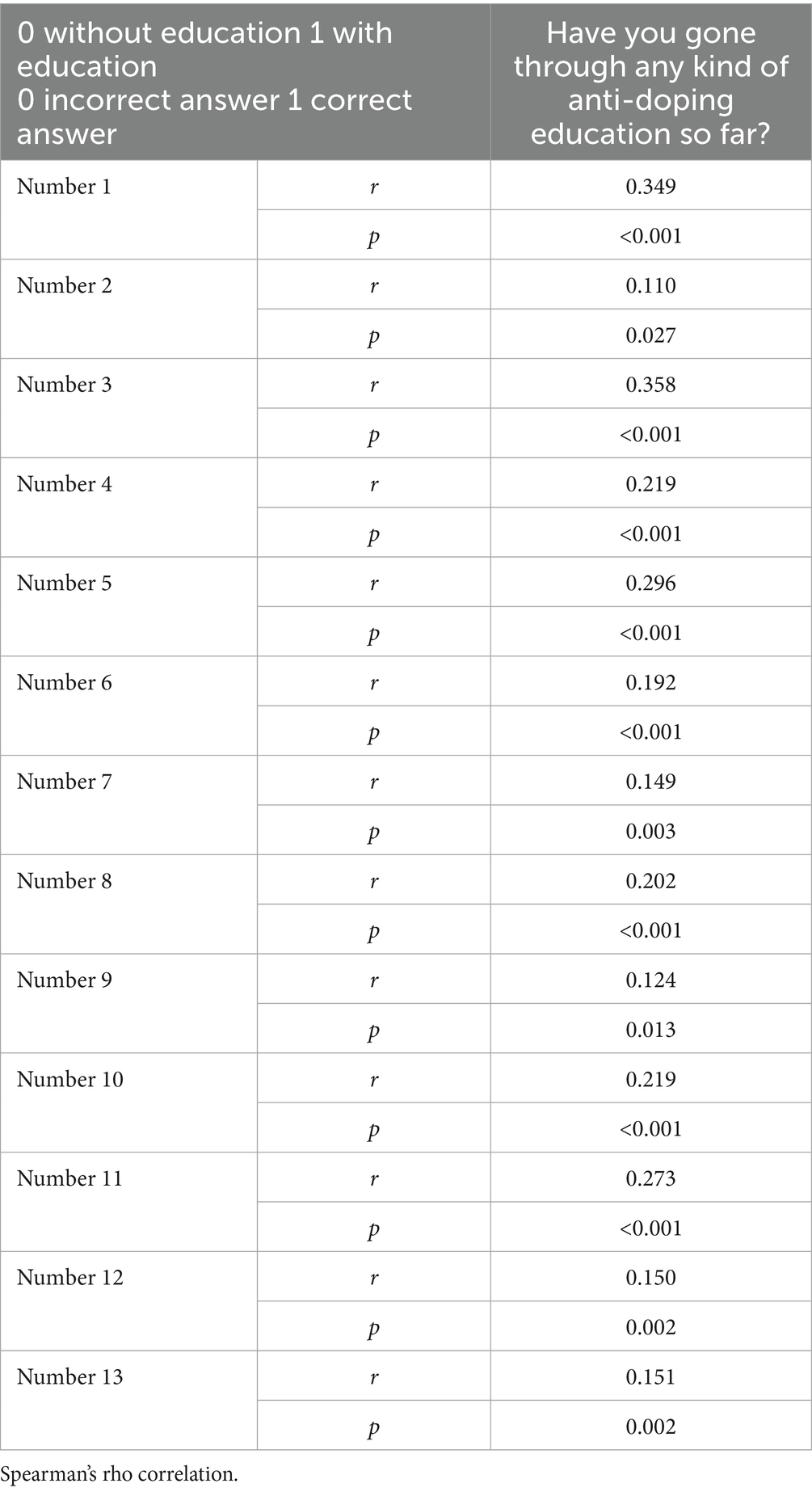

If we analyze the correlation between the answers and the questions posed (Table 4), we can see that for all questions, there is a strong positive correlation between the correct answer and attending education about doping.

Table 4. Correlation between anti-doping education and knowledge questions related to doping in sports.

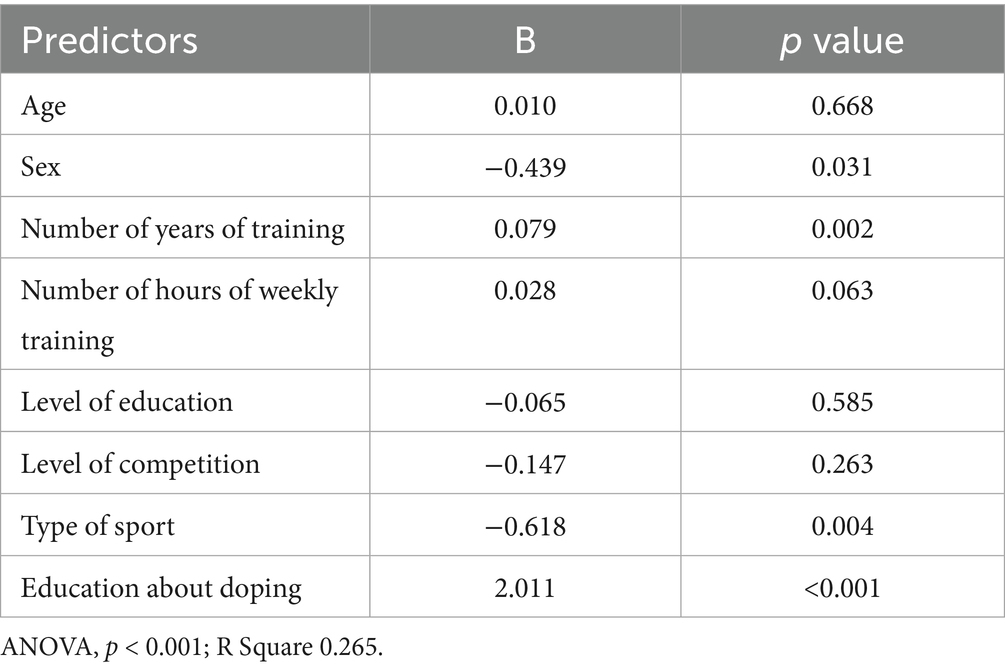

Table 5 presents the multiple regression analysis, which shows that the variability in the responses to the posed questions can be explained by the model in 26.5% of the cases. The most significant predictors of correct answers are gender, number of years of training, type of sport, and prior education against doping. The largest contribution to this model comes from the variable “prior education against doping,” that could be expected, followed by the type of sport. Those who had prior education against doping also have a higher rate of correct answers. Participants competing in individual categories have a higher rate of correct answers compared to those competing in team sports.

Discussion

Doping is undeniably one of the greatest challenges facing the world of sports today (28), as it poses significant risks to athletes’ health, undermines the integrity of sports, and damages the legitimacy of elite competitions (29). To combat this issue, international and national organizations have implemented various anti-doping educational programs aimed to prevent athletes from violating anti-doping rules. These programs address among other both intentional and unintentional doping, encouraging athletes to adopt anti-doping practices such as reporting doping incidents and verifying whether dietary supplements have undergone serial testing for regulation breaches (15).

The International Standard for Education 2021 is a mandatory International Standard developed as part of the World Anti-Doping Program. The overall goal of the ISE 2021 is to support the preservation of the spirit of sport and to help foster a clean sport environment.

Education seeks to promote behavior in line with the values of clean sport and to help prevent athletes and other persons from doping. A key underpinning principle of the ISE 2021 is that an athlete’s first experience with anti-doping should be through education rather than doping control (5). The correlation between the answers and the questions posed indicates a strong positive correlation between the correct answer and attending education against doping, which is in line with the ISE requirements that an athlete’s first experience with anti-doping should be through education.

It is recognized that most athletes wish to compete clean, have no intention to use prohibited substances or methods and have the right to a level playing field (5). In addition to athletes, recent research and educational efforts have expanded to include athlete support personnel (ASP)—coaches, doctors, trainers, and family members—who play an important role in shaping the moral climate that influences athletes’ behavior (19). Studies reveal that ASPs, particularly coaches, often share similar knowledge gaps and lack adequate resources (30, 31). This can lead to a passive approach, where performance is prioritized over the integration of anti-doping education into their responsibilities (32).

Our findings indicate that participants who received prior anti-doping education performed better in knowledge assessments than those who did not. Specifically, the group with prior education against doping had the highest proportion of participants answering 10 or more questions correctly out of 13, while the group without prior education against doping predominantly scored between 7 and 11 correct answers (p < 0.001). Additionally, the group with prior education against doping had a significantly higher proportion of women (43% vs. 23%), longer training periods, more weekly training hours, and underwent more frequent doping controls compared to the group without prior education against doping. These findings are consistent with previous research by other authors as follows.

Hurst et al. (33) assessed the effectiveness of the UK Athletics “Clean Sport” anti-doping program among junior elite athletes. The program included a single 60-min session covering the WADC, anti-doping rule violations, doping control procedures, medication checks, and risks associated with sports supplements. Three months post-program, athletes demonstrated increased familiarity with anti-doping rules and a reduced likelihood of using prohibited dietary supplements (33). Similarly, García-Martí et al. (29) evaluated the Spanish Anti-Doping Commission’s (CELAD) program among 145 sports science students. Four months after completing the program, participants showed improved knowledge of banned substances and greater degree of moral disapproval of doping (15). These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of national anti-doping programs in enhancing knowledge about doping, reducing the intent to use prohibited dietary supplements, and fostering stronger moral judgment against doping practices.

In our study, significant predictors of correct answers included gender, years of training, participation in individual versus team sports, and prior anti-doping education. Educated participants scored higher overall, and those involved in individual sports outperformed their counterparts in team sports. These findings are in agreement with Lazuras et al.’s study of 750 elite Greek athletes, which found doping use to be more prevalent among individual-sport athletes (7.4%) (34). In this study was used an integrated social cognition model to examine the predictors of doping intentions in 1075 Greek adult elite-level athletes. Analyses showed that attitudes, normative beliefs, situational temptation, and behavioral control significantly predicted doping intentions. Additionally, Morente-Sanchez et al. reviewed doping attitudes and behaviors among elite athletes, noting that differences in doping tendencies between individual and team sports may stem from variations in sport-specific federation policies or discrepancies in the number and rigor of doping controls (e.g., more frequent testing in cycling compared to football) (7). The importance of anti-doping education can be estimated based on the study by Hurst et al. (15), where it can be seen that athletes who completed measures of doping susceptibility, intention to use dietary supplements, Spirit of Sport and moral values, anti-doping knowledge and practice, and whistleblowing, had after 3 months of education decreased doping susceptibility and intention to use dietary supplements coupled with increased importance of values, anti-doping knowledge, anti-doping practice and whistleblowing. In the other study by Hurst et al. (33), was evaluating UK Athletics’ Clean Sport program in preventing doping. In participants was measured knowledge of anti-doping rules, intention to use supplements, and supplement beliefs remained, as well as doping likelihood and moral disengagement at baseline, immediately after the program, and at 3-month follow-up. Compared to baseline, immediately after the program, participants had more knowledge about anti-doping rules and lower scores for intention to use supplements, beliefs about the effectiveness of supplements, doping likelihood and doping moral disengagement. At follow-up, knowledge of anti-doping rules, intention to use supplements, and supplement beliefs remained different from baseline, whereas doping likelihood and moral disengagement returned to baseline. After attending this UK program, participants were less likely to dope unintentionally and intentionally in the short term. However, the effects on intentional doping were not maintained after 3 months. These findings suggest that the program of anti-doping education reduces intentional doping in the short term, it needs to be strengthened to sustain effects in the long term. This can be achieved through continuous education.

Limitations: Our research has some limitations. Athletes typically attend anti-doping education programs biannually in Serbia. Athletes who received anti-doping education prior to the obligatory anti-doping education for the scholars 2023, could receive education by different anti-doping organizations, since our scholars (The Athletics Federation of Serbia) are mixed of national and international athletes. Content delivered by different anti-doping organizations could differ in effectiveness. Future research could aim to investigate whether different anti-doping education programs created by different anti-doping organizations (e.g., national versus international education course) could have difference in effectiveness. A methodological limitation was that the test was not conducted after the anti-doping education, but rather we conducted the test only before the anti-doping education. In future anti-doping educations, we will conduct testing of participants before and after the implemented education, in order to assess the success of the education.

Conclusion

Our research shows that prior anti-doping education is effective and has the essential contribution on athletes’ knowledge about doping. Additionally, more efforts should be made in the future to educate male athletes, as well as athletes in team sports, as they have shown less knowledge about doping. Education programs should not only address athletes but also include coaches, physicians, and family members of athletes, as their relationship with athletes can either encourage or minimize doping behavior. Moreover, comprehensive curricula for sports education in schools should be revised to emphasize information about doping at an early stage, in order to raise awareness among amateur athletes as well.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committee of the Anti-Doping Agency of Serbia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZV: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology. JS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Software, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation. NmR: Writing – original draft, Software, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. GM: Resources, Project administration, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition. JR: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Software, Visualization. NnR: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation, Conceptualization. GP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis. DA: Visualization, Data curation, Validation, Software, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. MT: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis. SM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MV: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Serbian athletes for their time and effort.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Listiani, D, Umar, F, and Riyadi, S. Athletes’ (anti) doping knowledge: a systematic review. Retos. (2024) 56:810–6. doi: 10.47197/retos.v56.105029

2. World Anti Doping Agency. (2019) International Standard for Education (ISE). Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/world-anti-doping-code-and-international-standards/international-standard-education-ise (Accessed March 18, 2025).

3. Anti-Doping Education and Learning. (2025) ADEL. Available online at: https://adel.wada-ama.org/learn (Accessed March 25, 2025).

4. Woolf, JR. An examination of anti-doping education initiatives from an educational perspective: insights and recommendations for improved educational design. Performance Enhancement Health. (2020) 8:100178. doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2020.100178

5. World Anti Doping Agency. (2025) The World Anti-Doping Code. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/world-anti-doping-code (Accessed May 2, 2025).

6. Mottram, DR. Banned drugs in sport. Does the International Olympic Committee (IOC) list need updating? Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). (1999) 27:1–10.

7. Morente-Sánchez, J, and Zabala, M. Doping in sport: a review of elite athletes' attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). (2013) 43:395–411. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0037-x

8. Gucciardi, DF, Jalleh, G, and Donovan, RJ. An examination of the sport drug control model with elite Australian athletes. J Sci Med Sport. (2011) 14:469–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.03.009

9. Bahrke, MS, and Yesalis, C. Performance-enhancing substances in sport and exercise. Champaign, IL: Human kinetics (2002).

10. Backhouse, S., McKenna, J., Robinson, S., and Atkin, A.. (2007). International Literature Review: Attitudes, Behaviours, Knowledge and Education – Drugs in Sport: Past, Present and Future. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234838845_International_Literature_Review_Attitudes_Behaviours_Knowledge_and_Education_-_Drugs_in_Sport_Past_Present_and_Future (Accessed February 15, 2025).

11. Bloodworth, A, and McNamee, M. Clean Olympians? Doping and anti-doping: the views of talented young British athletes. Int J Drug Policy. (2010) 21:276–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.11.009

12. Petróczi, A, and Aidman, E. Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: review of the psychometric properties of the performance enhancement attitude scale. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2009) 10:390–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.11.001

13. Balk, L, Dopheide, M, Cruyff, M, Duiven, E, and de Hon, O. Doping prevalence and attitudes towards doping in Dutch elite sports. Scientific J Sport Performance. (2023) 2:132–43. doi: 10.55860/BCUQ4622

14. Davoren, AK, Rulison, K, Milroy, J, Grist, P, Fedoruk, M, Lewis, L, et al. Doping prevalence among U.S. elite athletes subject to drug testing under the world anti-doping code. Sports Med Open. (2024) 10:57. doi: 10.1186/s40798-024-00721-9

15. Hurst, P, King, A, Massey, K, Kavussanu, M, and Ring, C. A national anti-doping education programme reduces doping susceptibility in British athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2023) 69:102512. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102512

16. Bettinghaus, EP. Health promotion and the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum. Prev Med. (1986) 15:475–91. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90025-3

17. Wan, TTH, Rav-Marathe, K, and Marathe, S. A systematic review of KAP-O framework for diabetes. Med Res Arch. (2016) 3:483

18. Deng, Z, Guo, J, Wang, D, Huang, T, and Chen, Z. Effectiveness of the world anti-doping agency's e-learning programme for anti-doping education on knowledge of, explicit and implicit attitudes towards, and likelihood of doping among Chinese college athletes and non-athletes. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2022) 17:31. doi: 10.1186/s13011-022-00459-1

19. Blank, C, Kopp, M, Niedermeier, M, Schnitzer, M, and Schobersberger, W. Predictors of doping intentions, susceptibility, and behaviour of elite athletes: a meta-analytic review. Springerplus. (2016) 5:1333. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3000-0

20. Codella, R, Glad, B, Luzi, L, and La Torre, A. An Italian campaign to promote anti-doping culture in high-school students. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00534

21. García-Grimau, E, De la Vega, R, De Arce, R, and Casado, A. Attitudes toward and susceptibility to doping in Spanish elite and National-Standard Track and field athletes: an examination of the sport drug control model. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:679001. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679001

22. Nicholls, AR, Fairs, LRW, Plata-Andrés, M, Bailey, R, Cope, E, Madigan, D, et al. Feasibility randomised controlled trial examining the effects of the anti-doping values in coach education (ADVICE) mobile application on doping knowledge and attitudes towards doping among grassroots coaches. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2020) 6:e000800. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000800

23. Ntoumanis, N, Quested, E, Patterson, L, Kaffe, S, Backhouse, SH, Pavlidis, G, et al. An intervention to optimise coach-created motivational climates and reduce athlete willingness to dope (CoachMADE): a three-country cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. (2021) 55:213–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101963

24. Sagoe, D, Holden, G, Rise, ENK, Torgersen, T, Paulsen, G, Krosshaug, T, et al. Doping prevention through anti-doping education and practical strength training: the Hercules program. Performance Enhancement Health. (2016) 5:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2016.01.001

25. Wippert, PM, and Fließer, M. National doping prevention guidelines: intent, efficacy and lessons learned - a 4-year evaluation. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2016) 11:35. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0079-9

26. Rintaugu, EG, and Mwangi, FM. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions on doping among university students in physical education and sport science related degree programmes. J Hum Sport Exerc. (2020) 16:174–186. doi: 10.14198/jhse.2021.161.16

27. Murofushi, Y, Kawata, Y, Kamimura, A, Hirosawa, M, and Shibata, N. Impact of anti-doping education and doping control experience on anti-doping knowledge in Japanese university athletes: a cross-sectional study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2018) 13:44. doi: 10.1186/s13011-018-0178-x

28. Mountjoy, M, and Junge, A. The role of international sport federations in the protection of the athlete's health and promotion of sport for health of the general population. Br J Sports Med. (2013) 47:1023–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092999

29. García-Martí, C, Ospina-Betancurt, J, Asensio-Castañeda, E, and Chamorro, JL. Study of an anti-doping education program in Spanish sports sciences students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:16324. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192316324

30. Mazanov, J, Backhouse, S, Connor, J, Hemphill, D, and Quirk, F. Athlete support personnel and anti-doping: knowledge, attitudes, and ethical stance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2014) 24:846–56. doi: 10.1111/sms.12084

31. Patterson, LB, Backhouse, SH, and Duffy, PJ. Anti-doping education for coaches: qualitative insights from national and international sporting and anti-doping organisations. Sport Manage Rev. (2016) 19:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2015.12.002

32. Patterson, LB, and Backhouse, SH. “An important cog in the wheel”, but not the driver: coaches’ perceptions of their role in doping prevention. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2018) 37:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.05.004

33. Hurst, P, Ring, C, and Kavussanu, M. An evaluation of UK athletics’ clean sport programme in preventing doping in junior elite athletes. Performance Enhancement Health. (2020) 7:100155. doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2019.100155

Keywords: anti-doping education, knowledge, athletes, sport, public health

Citation: Vesic Z, Stojicevic J, Rancic N, Milovanovic G, Rasic JS, Radivojevic N, Prebeg G, Atanasov D, Todorovic M, Marjanovic S and Vesic MV (2025) Differences in anti-doping knowledge among Serbian professional athletes. Front. Public Health. 13:1625859. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1625859

Edited by:

Zbigniew Waśkiewicz, Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, PolandReviewed by:

Elena García-Grimau, Universidad San Jorge, SpainGökhan Doğukan Akarsu, Ruđer Bošković Institute, Croatia

Michael Petrou, Cyprus Anti-Doping Authority, Cyprus

Copyright © 2025 Vesic, Stojicevic, Rancic, Milovanovic, Rasic, Radivojevic, Prebeg, Atanasov, Todorovic, Marjanovic and Vesic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nemanja Rancic, bmVjZTg0QGhvdG1haWwuY29t

†These authors share first authorship

Zoran Vesic

Zoran Vesic Jelena Stojicevic2†

Jelena Stojicevic2† Nemanja Rancic

Nemanja Rancic Gorica Milovanovic

Gorica Milovanovic Jelena S. Rasic

Jelena S. Rasic Nenad Radivojevic

Nenad Radivojevic Milos Todorovic

Milos Todorovic