- 1Department of Computer, Control and Management Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Industrial and Information Engineering and Economics, University of L‘Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy

- 3Independent Researcher, Rome, Italy

- 4Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Urban forestry is recognized as a strategic lever for addressing the environmental and social challenges of cities, improving quality of life and promoting sustainable regeneration processes. This paper aims to investigate how urban forestry and the use of wood biomass are perceived by citizens, assessing their role in terms of collective wellbeing, environmental sustainability and territorial regeneration, with particular attention to differences related to gender, age, and value orientations. The research is conducted through an online survey carried out in Italy, aimed at gathering the opinions and perceptions of the population on the subject. The results show broad consensus, with generally very positive assessments, but with interesting differences: women and young people are more sensitive to behavioral aspects and more willing to financially support forestry initiatives, while men and older people favor structural and collective benefits. The analysis also identified two main profiles: a pragmatic cluster, oriented toward tangible and immediate interventions, and a value-based cluster, more attentive to widespread benefits and everyday sustainability practices. The findings highlight the need for differentiated communication and governance strategies. Interventions targeting more pragmatic citizen groups should prioritize communicating tangible local benefits, such as visible improvements in urban quality, environmental mitigation and direct improvements in everyday life. Conversely, strategies targeting value-oriented groups should emphasize collective responsibility, long-term environmental stewardship, and the integration of sustainable practices into daily routines, ensuring that policy narratives are aligned with citizens' normative commitments. Overall, the study provides actionable and context-sensitive insights for designing participatory frameworks that can strengthen institutional trust and promote a just, inclusive, circular, and effective green transition.

1 Introduction

Green entrepreneurship is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone for the advancement of the circular economy and sustainable development. Its relevance lies in its ability to stimulate innovation, create new business models, and promote local resilience by transforming environmental challenges into entrepreneurial opportunities. Scholars emphasize that green entrepreneurship fosters collaboration, improves regulatory compliance, and strengthens sustainable ecosystem management (Mondal et al., 2025a). However, although its potential is widely recognized, the concrete contribution of green entrepreneurship to cleaner production and circular economy practices remains under-explored (Mondal et al., 2025b). This gap in empirical validation reduces the ability to fully assess how entrepreneurial activities can translate sustainability imaginations into effective practices within cities.

At the same time, the issue of food waste has been shown to play a critical role for both the economy and the environment (Kostakis et al., 2024). Its proper management is directly linked to circular strategies and the achievement of the SDGs 7, 11 e 12. For this reason, systemic and systematic integration into educational programmes is essential (Kostakis and Tsagarakis, 2022), along with policies that promote entrepreneurship, innovation, and equitable socio-economic development (Kosta et al., 2025).

At the same time, the management of organic waste has emerged as a crucial component of urban sustainability, as it concerns a broader set of biodegradable flows that can be reintegrated into local bio-based cycles. Recent studies highlight how organic waste management plays a critical role for both the economy and the environment (Kostakis et al., 2024), and its valorization is directly connected to circular economy strategies and the achievement of key SDGs related to clean energy, sustainable cities and responsible consumption (SDGs 7, 11 and 12). The theme of SDGs is cross-cutting (Ikram and Boudraa, 2025; Ikram and Nahdi, 2025; Keskin, 2025), involving various stakeholders, and the literature focuses on green behavior interaction (Abdou, 2025; Saqib et al., 2025). However, analyses cannot ignore aspects related to social-culture aspects (Settembre Blundo et al., 2014; Kostakis et al., 2025).

This broader framing aligns with evidence suggesting that effective circular practices require not only technological solutions but also systemic and systematic integration into educational programmes to strengthen environmental awareness and long-term behavioral change (Kostakis and Tsagarakis, 2022). Furthermore, the implementation of circular and bio-based strategies relies significantly on institutional trust. When citizens perceive local authorities as transparent and competent, they are more inclined to support policies promoting innovation, entrepreneurship and equitable socio-economic development (Kosta et al., 2025), as well as participate in initiatives related to biomass valorization and urban forestry.

Business strategies also aim to combine the green and digital transition mix in different areas (Byrne et al., 2024; Colasante et al., 2025). Furthermore, the implementation of circular and bio-based strategies relies significantly on institutional trust. When citizens perceive local authorities as transparent and competent, they are more inclined to support policies promoting innovation, entrepreneurship and equitable socio-economic development (Kosta et al., 2025), as well as participate in initiatives related to biomass valorization and urban forestry. Conversely, low institutional trust can hinder participation and reduce the perceived legitimacy of environmental interventions.

Waste management pricing systems, if designed correctly, can strengthen citizen involvement (Di Foggia and Beccarello, 2023), while reducing disparities in resource distribution. However, unresolved tensions remain: the benefits are often perceived as unevenly distributed (Bourdin and Chassy, 2023) and negative perceptions continue to arise near production sites, often associated with the NIMBY phenomenon (Mazzanti et al., 2021).

The importance of integrating renewable energy in this context is particularly high. Local renewable energy production improves the energy autonomy of the territory (Lyytimäki et al., 2021) and, when combined with active community participation, generates significant economic and environmental benefits, such as reduced energy costs in energy communities (Gomes and Vale, 2024). However, inclusive governance and effective consultation are necessary to foster societal acceptance (Bourdin and Delcayre, 2024). Tax incentives and policies geared toward socio-political dynamics further increase public support for sustainable mobility and tourism (Gould et al., 2024). Despite this advance, participation in energy transition research remains limited at all stages (Huttunen et al., 2022), hampered by rigid institutional frameworks and a lack of trust among key actors (Kiss et al., 2022). Restoring trust in institutions and businesses therefore becomes a prerequisite for progress (Huntjens and Kemp, 2022).

Urban transitions toward smart and sustainable cities are also highly relevant to the circular economy. Scholars agree that neighborhoods are the basic unit of transformation (Allam and Jones, 2021). Civic participation is essential for tackling the climate crisis through inclusive and equitable strategies (Galende-Sánchez and Sorman, 2021) and highlights the need to balance innovation with social equity (Radtke, 2025). City self-assessments reveal barriers to circular approaches and inform local governance frameworks (Möslinger et al., 2023). Public engagement and the dissemination of knowledge about green technologies are fundamental to sustainable learning (Basilico et al., 2025b), particularly when integrating social and environmental justice into smart city governance (Sengupta and Sengupta, 2022). Neighborhoods are the fundamental scale of urban transformation, where sufficiency, housing regeneration, and stakeholder perceptions drive adaptive planning and SDG implementation (Winston, 2022; Kim and Feng, 2024).

In this context, sustainable neighborhoods are often analyzed through the lenses of energy justice, participatory governance and resource autonomy (Benjumea Mejia et al., 2024; Wenander, 2024). Energy communities, in particular, are promoted by the European Union as a targeted strategy for renewable energy production, energy independence, and participatory governance (López et al., 2024; Lazaroiu et al., 2025). They strengthen local democracy and provide tangible economic benefits to prosumers, contributing to collective wellbeing (Basilico et al., 2025a).

Despite the widespread recognition of these benefits, a significant gap in research remains. While renewable energy in general, and energy communities in particular, have received considerable attention from scholars, the specific dimension of citizen acceptance of biomass use in urban contexts has not been sufficiently examined (Jozay et al., 2024; Mashhadi et al., 2024; D'Adamo et al., 2025). Biomass is pivotal for circular strategies, but without clearer insights into citizens' acceptance in urban contexts, its potential may be undermined by social resistance.

The work aims to fill this gap by investigating how citizens perceive urban forestry and the use of wood biomass, analyzing the value attributed to it in terms of quality of life, urban regeneration and environmental sustainability. The objective is to understand how these perceptions vary according to socio-demographic factors and value orientations, identifying distinct profiles of citizens and assessing the strategic implications for policies and practices of communication, participation, and sustainable resource management.

2 Literature review

Interest in urban green spaces is growing rapidly. For this study, before conducting a systematic literature review (SLR) aimed at the objective of the article, the Scopus database was consulted, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and the procedures adopted in recent studies (Basilico et al., 2025a; Bitzenis et al., 2025). The search was carried out on 21 September 2025, using the following query:

“Circular Economy” AND “Urban” AND “Biomass” AND “Sustainability” within Article title, Abstract, Keywords. Two exclusion criteria were applied—Figure 1:

• E1 - The publication was not in English.

• E2 - The publication was not an article or review.

A total of 30 works were identified, showing a trend that peaks in 2025 with 9 articles. No author has more than one article. Sustainability is the leading journal with 4 works, followed by the Journal of Cleaner Production with 3 works. The geographical concentration shows a predominance of European countries: Spain (6) followed by Portugal (5) and Italy (4).

To highlight the main recurring themes that emerged from the Scopus query, a thematic map was created using the R programming language (Figure 2). When reading the map, the vertical axis indicates the relative importance of the themes, while the horizontal axis represents their level of development.

The thematic map confirms the presence of four distinct research areas. Themes located in the upper-right quadrant represent well-developed and highly central topics, such as urban sustainability and circular practices, indicating their consolidated role in literature. Conversely, themes in the lower-right quadrant are conceptually central but less developed, suggesting emerging lines of inquiry, particularly regarding the integration of biomass valorization into urban strategies. The upper-left quadrant contains well-developed but more peripheral themes, while the lower-left quadrant shows niche topics that are still evolving. Overall, the map highlights how urban forestry, circular economy and biomass use intersect in a growing research space, supporting the relevance of exploring citizens' perceptions within this framework.

A third exclusion criterion was applied:

• E3 - Topic not aligned with the study focus.

This additional filter determines the more detailed analysis of 15 works. Sustainable management of urban and agricultural waste is a complex challenge for cities and rural communities. At the same time, it offers significant opportunities to promote the circular economy and environmental resilience. Some optimal solutions include adopting pilot projects, collaborating with the private sector, and overcoming technological barriers to ensure long-term sustainability in wood waste management (Mojtahezadeh et al., 2025). Adding biochar to compost boosts nutrient retention, cuts phosphorus and nitrogen losses, and provides a safe, sustainable alternative to peat for urban and home gardening (Veliu et al., 2025). The integration of green energy supply chains and urban and agricultural waste recovery processes is proving to be an enabling factor for regional sustainability. This approach promotes scalable processes, efficiency in material recovery and long-term industrial synergies (Filho et al., 2025).

Integrated systems, combining biomass recovery, wind energy, fuel production and drinking water through desalination, can be evaluated to assess the energy and environmental sustainability of urban and rural systems (Ayub et al., 2025). The adoption of hierarchies for biomass utilization processes allows for the optimisation of its use from agricultural, urban and industrial residues. In this way, carbon neutrality and compliance with the principles of the circular economy are promoted (Cansado et al., 2025).

Governance, safety, and end-of-life management aspects are crucial for the sustainability of bio-based materials. Optimized wastewater treatment and urban waste recovery practices reduce environmental and health risks, promoting circular and resilient systems (Sgarbi et al., 2023; Muniz Sacco et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024; Assies et al., 2025). The use of microalgae and phytotoxic waste can increase agricultural productivity and reduce the use of chemical herbicides. At the same time, the integration of bioenergy, sustainable materials and sensory technologies supports circular horticultural production (Salinas-Velandia et al., 2022; Álvarez-González et al., 2023; Duarte et al., 2023). In addition, integrated hubs for marine resource management, urban waste and renewable energy production, including green hydrogen generation, strengthen local food security, reduce emissions and foster industrial synergies. These solutions offer a model for the transition to resilient cities and extended circular economy systems (Sadhukhan et al., 2018; Song et al., 2021; Sajna et al., 2024). Overall, evidence shows that urban and rural sustainability requires integrated approaches, combining technological innovation, effective governance, cross-sector collaboration and biomass valorization.

3 Methodology

The literature highlights how the direct involvement of communities and consideration of individual perceptions are fundamental elements for the success of urban regeneration policies (Atiqul Haq et al., 2021; Dmitrović et al., 2025).

3.1 Survey on-line

In this context, the online survey method has proven to be an effective tool both for recruiting participants and for collecting data, thanks to the possibility of using diversified measurement tools and reaching a large and geographically varied sample. This methodology has also been widely applied in studies examining sustainable consumption behaviors, confirming its validity and versatility in various fields of research (Otaki and Kyono, 2022; Colasante et al., 2025; Ruiz-Navarro et al., 2025).

Comparative studies report that many psychometric scales show internal consistency and comparable measurement properties between web and traditional methods, making web surveys suitable for advanced analysis (Fang et al., 2021). This approach therefore allows for an in-depth exploration of citizens' opinions and attitudes, proving particularly useful for analyzing the factors that influence their willingness to support environmental and social initiatives (Ponto, 2015).

The survey was disseminated through multiple digital channels—including Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn—in order to maximize outreach and engage a diverse audience. As with all voluntary online surveys, some degree of self-selection bias cannot be entirely excluded. Respondents who are more interested in environmental topics may have been slightly more inclined to participate. Nevertheless, steps were taken to mitigate this issue by distributing the questionnaire across multiple platforms with different user profiles and by designing the survey to be easily accessible also to less engaged individuals. This multi-platform approach helped to overcome some of the typical limitations of online data collection (Menegaki et al., 2016) by capitalizing on the specific engagement dynamics and user profiles of each platform (Albert and Smilek, 2023).

Despite some critical issues that may arise in the use of online questionnaires, this methodology is consistent with the research objectives, as it allows for rapid, widespread and cost-effective data collection (Regmi et al., 2017). Other advantages of electronic surveys include speed, cost, convenience, flexibility, ease of analysis, global reach, reduction of errors, and diversity of questions (Keith et al., 2023).

The questionnaire was administered online via Google Forms in May 2025 and was completed by 435 participants. It consists of a total of 21 questions, organized into several thematic sections. Section I (socio-demographic) collects basic information (age, gender, income). The second section (perception of urban forestry) investigates perceptions of clean energy, land redevelopment, wellbeing and everyday actions using a Likert scale. The third section (perception of the use of wood biomass) collects opinions on perceived risks and benefits, recorded both before and after a brief technical briefing. The fourth (risk assessment) and fifth (benefit assessment) sections explore separately perceived risks (costs, dust, fires, etc.) and benefits (clean energy, emission reduction, waste recovery, innovation). Finally, the sixth section [willingness to pay (WTP)] explores citizens' economic propensity for planting in private and public areas. Monetary variables such as the WTP are typically right skewed and sensitive to extreme values. For this reason, the study assessed their distribution and applied log transformations when appropriate, while also considering median values and interquartile ranges to ensure robustness against outliers. These steps help reduce distortions and improve the reliability of subsequent comparisons.

The analysis of the collected data was conducted using an integrated approach that initially involved a statistical-descriptive phase, followed by an exploratory segmentation phase using cluster analysis.

Various tests were applied to verify statistical significance: t-tests, Friedman tests, Wilcoxon post-hoc tests, Kruskal–Wallis tests, and t-tests for independent samples.

To identify homogeneous respondent profiles, the K-Means clustering algorithm was used to identify homogeneous profiles based on perceptions, risks, benefits, and economic availability. The choice of K = 2 was primarily guided by the analysis of inertia, which showed a clear drop between the first and second partition. However, it is acknowledged that more complex structures may also exist. For this reason, the Silhouette Index was additionally examined to verify the internal coherence of the clustering solution, which confirmed that the two-cluster configuration offers a good balance between interpretability and statistical quality. The Likert data were transformed into weighted averages; the monetary variables were log-transformed and then standardized using z-scores. After testing several solutions, the optimal number was found to be k = 2 according to the Elbow Method, which compares different values of k based on the trend of the function, comparing the inertia for each configuration. Figure 3 describes the methodological framework used in this work. This method is used in literature to assess sustainability prospects (D'Adamo et al., 2024; Detrinidad and López-Ruiz, 2024; Facendola et al., 2024).

3.2 Multi-criteria decision analysis

The strategic analysis was conducted using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA), with the aim of establishing a ranking of priorities among nine criteria relating to urban forestry and the use of wood biomass. Three MCDA methods widely recognized in the literature were applied: (i) Weighted Sum Model (WSM), (ii) TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution), and (iii) VIKOR (VlseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje). These approaches are well established in the literature (Abdul et al., 2022; Iç et al., 2022; Soltanifar et al., 2023; Ahmed et al., 2024).

The WSM calculates a weighted sum of the experts' assessments for each criterion. In the case in question, equal weights were used for all experts, so that the final score coincides with the arithmetic mean of the normalized evaluations. TOPSIS is based on the idea that the best criterion should be as close as possible to the ideal positive solution and as far as possible from the negative one. VIKOR aims to identify a compromise solution, taking into account both the aggregate distance from the ideal situation and the maximum deviation. A parameter v = 0.5 is used. Each method produces an independent ranking of the criteria; the results are then combined through rank aggregation (average ranking) and verified using a correlation matrix (Spearman's coefficient) to check the consistency between the different rankings.

Ten experts were selected from among academics, environmental consultants, environmental technicians, and spatial planners. The composition of the panel is also balanced in terms of gender (40%) and professional background (all with at least 10 years of experience and 5 years for consultants), ensuring judgements that are both theoretically and practically sound.

The nine criteria represent the main strategic dimensions related to urban forestry and woody biomass and were pre-validated by two academics before being used in the strategic analysis:

• C1 – Area enhancement. The extent to which urban forestry interventions contribute to the enhancement of urban areas. This concerns territorial regeneration, urban quality, and the redevelopment of spaces.

• C2 – Healthcare costs. The extent to which urban forestry can reduce healthcare costs related to air pollution. Economic and healthcare dimension, linked to public health benefits.

• C3 – Employment. The potential of urban forestry to generate new jobs and dedicated professional skills. Green work/employment dimension.

• C4 – Environmental impact. The ability of urban forestry to reduce overall environmental impact. Includes CO2 absorption, heat island mitigation and air quality improvement.

• C5 – Attracting funds. The effectiveness of urban forestry as a lever for attracting European or national funds for ecological transition. Links local projects to funding programmes.

• C6 – Technologies. Adequacy of available technologies to implement urban forestry interventions. Considers technological maturity, replicability and reliability of solutions.

• C7 – Sustainable biomass. Perception of wood biomass as a sustainable energy source compared to other renewables. Concerns environmental impacts, supply chain and overall sustainability.

• C8 – Energy independence. Contribution of the wood biomass supply chain to reducing energy dependence on foreign countries. Strategic energy dimension.

• C9 – Circular economy. Integration of wood biomass into a circular economy strategy, maximizing material reuse and waste reduction.

4 Results

The sample analyzed consists of 435 respondents. In terms of gender, the respondents are evenly divided, with 54.5% men and 45.3% women. In terms of age, the majority of participants are under 40 (57.7%), while the remaining 42.3% are over 40. The average age is 37.6 years. In terms of income, almost half of the sample (46.4%) reported an income of up to 20,000 €, followed by a significant 31.5% with an income between 20,001 € and 40,000 €; with lower percentages in the medium-high brackets: 40,001–60,000 € (11.7%) and >60,000 € (10.3%). The sample is similar to others in terms of gender, income (Basilico et al., 2025a) and age (Colasante et al., 2025).

4.1 Perception of urban forestry

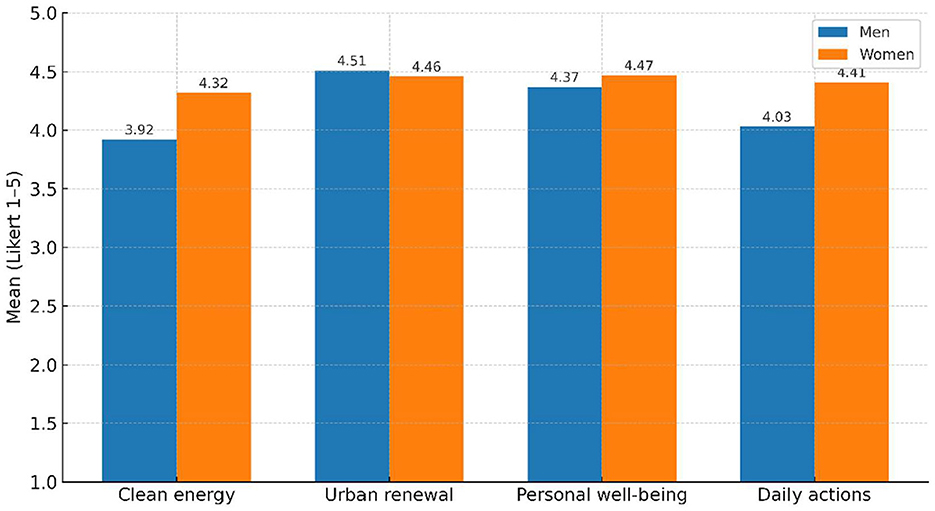

The second section evaluates attitudes and perceptions toward the concept and, more specifically, the idea of afforestation under the headings Clean Energy, Land Redevelopment, Personal Wellbeing and Everyday Actions—Figure 4. All averages are above 4, indicating a strongly positive attitude toward afforestation and suggesting that respondents do not perceive the issue as marginal, but as a relevant factor for everyday life and the urban context. These high values may partly reflect a social desirability bias, a well-known mechanism in self-reported environmental surveys in which individuals tend to overestimate their pro-environmental attitudes to appear responsible or socially conscious. This tendency can amplify already positive evaluations.

In particular, land redevelopment obtained the highest score (4.5 on a Likert scale of 1–5), followed by personal wellbeing (4.4). It should also be noted that the use of a 1–5 Likert scale may compress the distribution of responses, especially for socially desirable topics such as environmental protection, reducing dispersion and creating high, clustered scores. This highlights how afforestation is perceived not only as a tool for environmental sustainability, but also as an opportunity for urban regeneration and improvement of individual quality of life. The variability (standard deviation of 0.71 and 0.84, respectively) is limited, suggesting a considerable convergence of opinion: the majority of respondents give medium-high scores to these dimensions, with no significant differences between individuals.

Clean energy ranks lowest (4.1), although it is still well regarded. This pattern aligns with established findings in environmental psychology, which show that men tend to prioritize structural and context-oriented aspects of sustainability, whereas women more frequently emphasize ecological, relational and behavior-oriented dimensions. These gendered orientations have been repeatedly documented in the literature (Hunter et al., 2004), offering a useful interpretative framework for the differences observed in our sample. It is also important to note that the present sample is not statistically representative of the national population; therefore, these differences should be interpreted as indicative rather than generalizable to all citizens. This slightly lower evaluation is likely not due to a lack of interest in clean energy, but rather to limited ecological knowledge regarding the relationship between afforestation, biomass use and energy production. Benefits that are less visible or less intuitive for the public often receive more cautious assessments. This result can be interpreted as a sign of a less direct perception of the connection between afforestation and energy production: respondents recognize the environmental value of the action, but are less immediately aware of its impact on energy generation. Finally, everyday actions (4.2) rank slightly higher, but with greater variability (standard deviation = 0.91), indicating that there is greater diversity of opinion on this point: some respondents attribute a crucial role to individual commitment, others less so.

To confirm that the differences between the four dimensions considered are statistically significant, the Friedman test [χ2(3) = 86.34, p < 0.001] was applied, confirming that the ratings attributed to the four dimensions are not equivalent. In particular, respondents gave significantly higher ratings for land redevelopment and personal wellbeing than for clean energy and everyday actions. The presence of systematic differences confirms the heterogeneity of perceptions within the sample and reinforces the hypothesis of greater social and territorial relevance of afforestation.

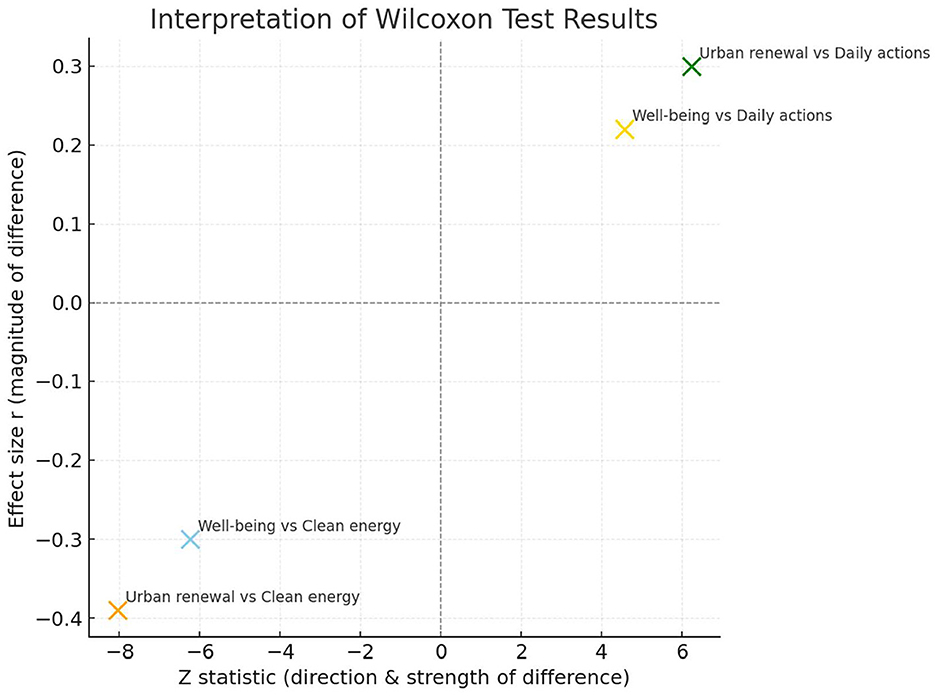

To identify which pairs of dimensions, differ from each other, post-hoc comparison tests were performed, specifically Wilcoxon tests for paired measures on all pairs, in order to obtain six comparisons, with Holm correction for the control of the overall type I error. The post-hoc results reveal some relevant evidence, where Z represents the statistical value of the test, indicating the intensity and direction of the difference observed between two dimensions, and r represents the size of the effect—Figure 5.

The most marked differences are observed between land redevelopment and clean energy (p < 0.001) and between personal wellbeing and clean energy (p < 0.001), showing that participants attribute much greater value to urban regeneration and wellbeing than to energy impacts. Significant differences also emerge between land redevelopment and everyday actions (p < 0.001) and between personal wellbeing and everyday actions (p < 0.001), suggesting that forestation is perceived more as a structural policy and a factor of collective wellbeing than as an individual responsibility. Conversely, there are no significant differences between clean energy and everyday actions or between land redevelopment and personal wellbeing, highlighting a similar perception within each pair: the first two dimensions represent the lower end of perceived priorities, while the latter are at the higher end.

Overall, the data confirm that respondents recognize more strongly the value of afforestation in terms of urban regeneration and improved wellbeing than its impact on energy or the contribution of individual daily behaviors. Although some of the differences between dimensions are statistically significant, their practical magnitude remains small. All average values fall within a narrow, high range, indicating that respondents generally agree on the benefits of afforestation, even if for different underlying reasons. Therefore, statistical significance should be interpreted with caution. The observed effect sizes (r between 0.22 and 0.39) correspond to small-moderate intensities, but are nevertheless consistent and significant from an interpretative point of view.

After analyzing the overall sample, the data was disaggregated by gender to observe any significant differences in perceptions. To this end, a comparison test between averages disaggregated by gender was conducted, considering men and women separately (Figure 6).

Firstly, it should be noted that in both groups the ratings remain very high (all averages are above 4), confirming a general consensus on the importance of forestry. However, the disaggregated analysis highlights some significant differences. As far as men are concerned, the highest scores are attributed to land redevelopment and personal wellbeing. This indicates greater attention to the structural and collective dimensions of the phenomenon, i.e., linked to improving urban quality and the perception of widespread wellbeing. Women, while confirming the same orientation, show slightly higher sensitivity to other dimensions. In particular, women assign higher values to clean energy and everyday actions. Overall, the female component of the sample tends to recognize more strongly both the link between forestry and sustainable energy and the role of individual practices and everyday responsibilities in promoting sustainability. In direct comparison, therefore, two complementary orientations emerge:

• Men favor aspects of urban transformation and collective wellbeing, scoring slightly higher on structural dimensions.

• Women show greater attention to energy and behavioral aspects, emphasizing the link between afforestation, clean energy production and sustainable daily practices.

Overall, the disaggregated data indicate that, despite widespread agreement on the importance of forestation, there are gender differences that reflect different sensibilities: more practical and every day in the case of women, more focused on aspects of urban regeneration and widespread wellbeing in the case of men. This evidence offers useful insights for interpreting social perceptions and calibrating any communication strategies or intervention policies, taking into account the nuances that characterize the different subgroups.

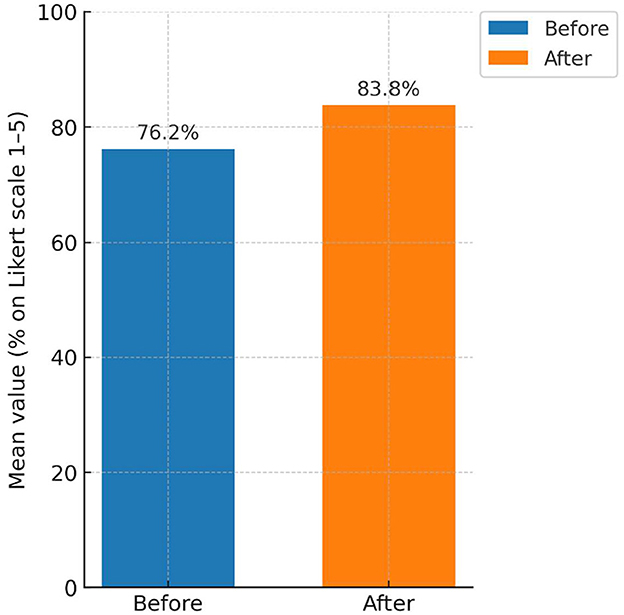

4.2 Informational impact on the perception of biomass

The third section is dedicated to the evaluation of woody biomass, before and after reading the descriptive information, highlighted a significant improvement in respondents' perception. The overall mean score increased from 3.81 to 4.19 on a 1–5 Likert scale, corresponding to an increase from 76.2% to 83.8% of the maximum scale (Figure 7). The improvement was observed across all subpopulations analyzed: age group 18–40 years (from 3.85 to 4.23), age group 41–80 years (from 3.77 to 4.14), women (from 3.80 to 4.16), and men (from 3.83 to 4.21). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirms that these differences are statistically significant in all cases (p < 0.001)—Table 1.

Figure 7. Overall average evaluation of woody biomass before and after the descriptive information (Likert scale 1–5, reported as percentage).

Table 1. Descriptive results and Wilcoxon test for the evaluation of woody biomass before and after the descriptive information.

From a statistical perspective, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test returned extremely low p-values (p < 0.001) both in the overall sample and in all the subgroups considered. This implies that the probability that the differences observed between the “before” and “after” evaluations are due to chance is practically null. In other words, this is not a simple random fluctuation, but a real and systematic change induced by the informational intervention. This result suggests that even a brief, clear technical explanation is sufficient to improve public acceptance of biomass-related interventions. Providing accessible information reduces misconceptions and increases familiarity with the topic, which is known to be a key determinant of positive environmental attitudes in the literature on public perception of bioenergy systems. The increase observed after the informational treatment is statistically significant across all subsamples (p < 0.05), confirming that the change in perception is not due to random variation but emerges consistently among age and gender groups. The pattern also indicates that citizens tend to respond more readily to benefits that are concrete and easy to visualize—such as air quality improvement or cost reduction—while more systemic or indirect aspects remain less salient. The absence of negative shifts and the generally positive trend suggest that biomass is not associated with fear or rejection, but rather with a form of informed caution that can be reduced through targeted communication.

This result is also clearly shown in Figure 8, where the columns referring to the “after” evaluations are consistently higher than those referring to the “before” evaluations across all analyzed categories (age groups, gender, and overall mean). The uniform increase in averages confirms that the informational effect had a positive and transversal impact, regardless of the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

Figure 8. Average evaluations of the perception of woody biomass before and after the descriptive information, broken down by age group and gender (Likert scale 1–5, reported as percentage).

4.3 Risks and benefits of using wood biomass

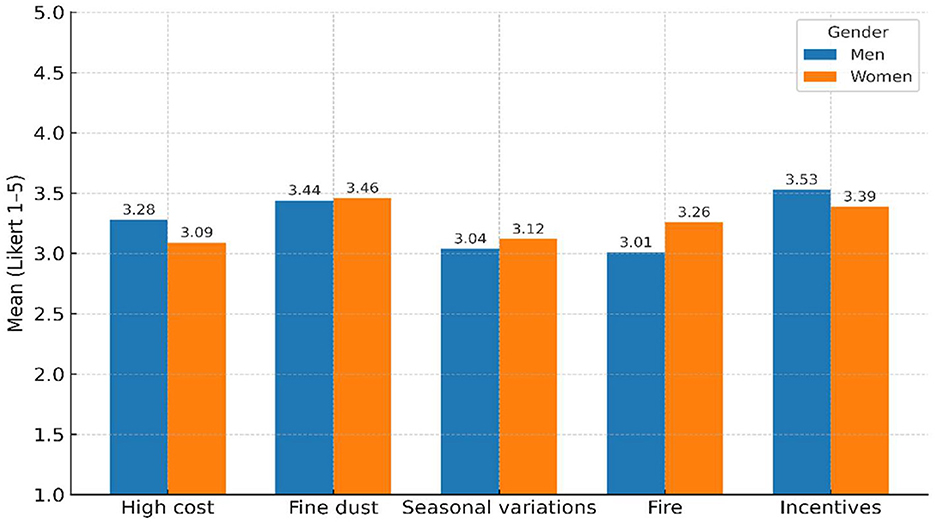

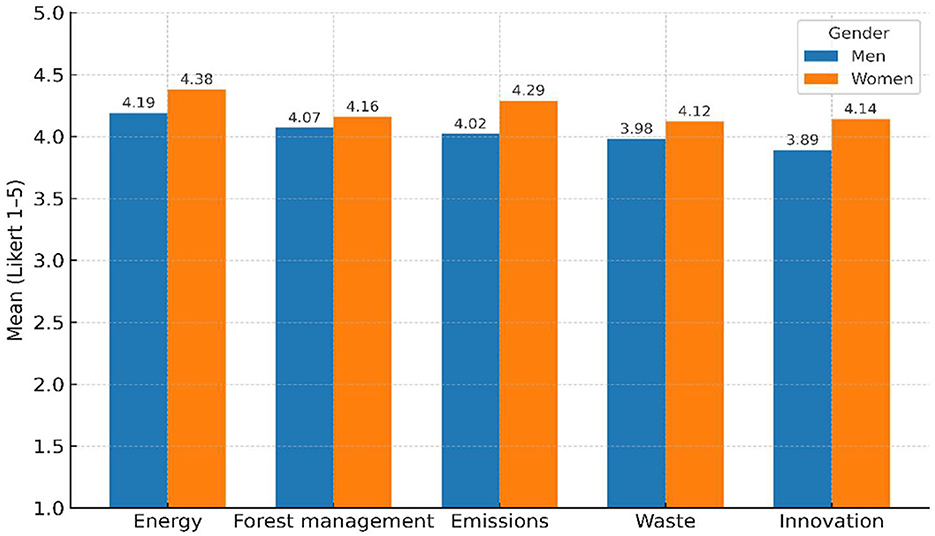

Sections four and five of the questionnaire analyse the risks and benefits of using woody biomass. This phase of the analysis aims to understand whether the assessments expressed on the potential negative and positive impacts are consistent among respondents or whether they vary significantly according to gender and age (Figures 9–11).

The distribution of responses shown in Figure 12 indicates that citizens tend to focus primarily on the most tangible and immediately perceptible benefits of biomass, such as improvements in air quality and potential cost reductions. In contrast, more systemic or long-term benefits—such as contributions to climate mitigation or circular bioeconomy processes—receive comparatively lower salience. The absence of strong negative evaluations suggests that woody biomass is not perceived as a risky or threatening option; instead, respondents express a form of informed caution, characterized by generally positive attitudes accompanied by a desire for clarity and reassurance. Statistical tests confirm the robustness of these patterns, with significant differences across the dimensions assessed (p < 0.05), indicating that public perceptions exhibit a consistent structure across the sample. Taken together, these results indicate that the socio-demographic differences observed across Sections 4.1 and 4.2 should not be interpreted as rigid divisions between groups, but rather as distinct cognitive orientations. Some respondents appear more focused on the concrete, visible outcomes of environmental interventions (“what” the action produces), while others evaluate sustainability through broader value-based or procedural considerations (“how” the action is implemented). These complementary interpretative frames help explain why overall consensus coexists with differentiated patterns of emphasis across the sample.

The average risk scores range between 3.2 and 3.7, confirming a moderate perception: citizens recognize the existence of critical issues, but without attributing them predominant importance. In particular, the most pressing risks are fine particulate matter (average 3.7) and the high cost of collection and transport (3.6), while dependence on public incentives is considered less relevant (3.2). A comparison by gender reveals significant differences using the Kruskal–Wallis test: women give higher scores to both high cost [χ(2) = 5.29, p = 0.021] and the risk of fire in storage [χ(2) = 5.74, p = 0.017]. In relation to age, the most marked difference concerns fine particulate matter, which is of significantly greater concern to the over −40 s [χ(2) = 18.11, p < 0.001].

The benefits scored much higher, all between 4.3 and 4.6, indicating widespread consensus on the usefulness of biomass. The most appreciated benefit is the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (average 4.6), followed by clean energy (4.5) and sustainable forest management (4.4). From a gender perspective, women give significantly higher scores to clean energy [χ(2) = 14.45, p < 0.001], emission reduction [χ(2) = 18.01, p < 0.001] and green technological innovation [χ(2) = 4.11, p = 0.043]. In terms of age groups, those over 40 place greater emphasis on structural and collective benefits, assigning higher values to clean energy [χ(2) = 46.27, p < 0.001], forest management [χ(2) = 33.53, p < 0.001] and emissions reduction [χ(2) = 35.06, p < 0.001], while younger people still maintain high scores but show a relatively greater sensitivity toward green technological innovation.

Overall, the results highlight how, despite a general consensus, there are socio-demographic differences that reflect different sensitivities: women and those over 40 tend to value stability, security and structural benefits, while men and younger people appear more oriented toward concrete and innovative aspects. Quantitative evidence and statistical tests therefore confirm that perceptions of biomass are not uniform, but vary in nuances that can guide targeted communication and policy strategies. This heterogeneity paves the way for more in-depth analysis. Statistical tests have confirmed the existence of significant differences, but at the same time have shown the limitations of an interpretation that stops at socio-demographic comparisons alone.

4.4 Willingness to pay

In order to fully grasp the combinations of variables and the more complex relationships between risks, benefits, attitudes and economic availability, an exploratory approach capable of identifying homogeneous groups of respondents is necessary. The sixth section of the questionnaire investigates the WTP of respondents, assessing the monetary amount they would be willing to pay:

• to have a tree on their property (garden or land);

• to have a tree in public areas near their residence, knowing that the biomass resulting from pruning would be reused in wood biomass plants.

To assess the existence of significant differences based on socio-demographic variables, an independent sample t-test was applied—Table 2.

The results show that, despite some significant average differences, none of them are statistically significant in the tests conducted. It should be noted that monetary variables such as WTP typically exhibit skewness and non-normal distributions, which may reduce the power of parametric tests such as the t-test. The absence of statistically significant differences between groups may therefore be partly attributable to high within-group variance and the presence of a few highly generous respondents who shift the mean upwards. Future analyses could benefit from applying log-transformed models or using non-parametric regression approaches (e.g., quantile regression) to account for distributional asymmetries and better isolate the role of age, gender and environmental attitudes. Excluding extreme outliers may also help stabilize the estimates and support a more precise comparison across groups. In addition, respondents often report higher WTP when their answers are not tied to real economic consequences (Cascavilla et al., 2025).

From a descriptive point of view, women report a higher willingness to have a tree in their home (140 € compared to 67 € for men), while for public areas the differences are considerably smaller (56 € compared to 52 €). With regard to age, those under 40 report a higher average willingness to pay for both private planting (138 € compared to 65 € for those over 40) and public planting (59 € compared to 49 €).

The results indicate that willingness to pay does not differ significantly between genders or age groups. However, they suggest some interesting trends: women and the under- s appear to be more inclined to financially support forestry initiatives, both in the private and public spheres. This relative homogeneity, combined with slight differences between subgroups, provides useful insights for targeting awareness campaigns and policies, taking into account different socio-demographic propensities.

This is the focus of the Cluster Analysis, which will allow us to outline distinct profiles of citizens, going beyond simple categories of gender or age and offering a richer and more useful interpretative tool in terms of application.

4.5 Cluster analysis

K-means analysis was used to identify homogeneous segments of respondents based on quantitative variables (Likert averages, perception of risks/benefits, economic availability), in order to profile groups with different attitudes/propensities and derive targeted actions.

The data sample analyzed consists of 435 respondents. The data structure is organized into two-dimensional matrices, with a unifying and fixed variable, represented by age group, which is divided into two groups: 18–40 years and 41–80 years. The tables collected differ in terms of the variable on the x-axis, where Likert scales from 1 to 5 were used, weighted averages of Likert scale values for risk and benefit areas, and economic availability expressed in euros. Based on the data collected in the questionnaire, raw cumulative tables were created, which will serve as a basis for the subsequent stages, as indicated in Appendix B. For the sake of transparency and replicability, the entire code developed is reported in Appendix C. Below is an example related to the first category, “Afforestation and Sensitivity” (Table 3).

For the purposes of cluster analysis, a single matrix of characteristics was constructed. Each row represents a respondent and each column a variable in order to proceed with a single, comparable segmentation that also takes into account the interrelationships between the different thematic areas—Table 4.

Table 4. Matrix of average values by age group (18–40 and 41–80) on the variables proposed for analysis.

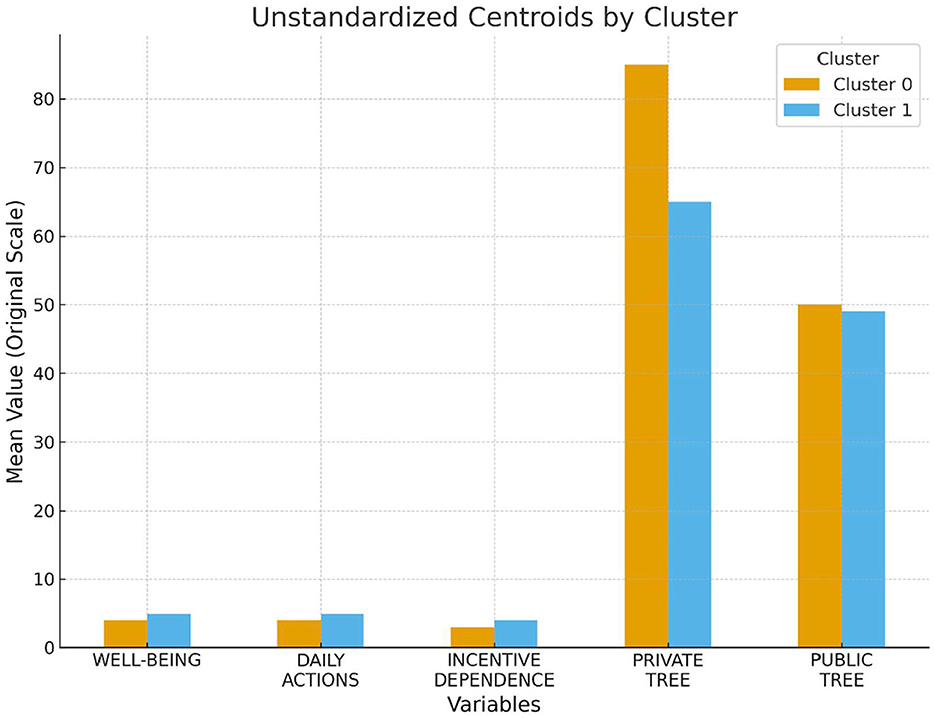

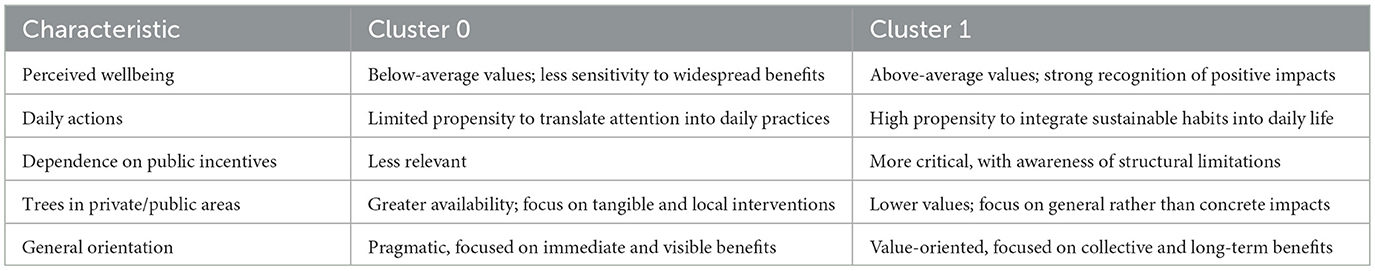

For the analysis of the sample, a series of transformations and inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure that the data used were numerical, comparable and standardisable. The clusters were compared with the age breakdown, finding that both age groups were represented in each group. This confirms that the partition identified by the algorithm reflects more complex combinations of attitudes and preferences, and is not exclusively linked to the age variable. The analysis therefore demonstrated that the two-cluster structure is robust, maintaining its consistency even when considering this distinction. The analysis of standardized centroids (Figure 13) made it possible to outline two distinct and easily interpretable profiles. The variables considered were reported in normalized form (z-score), so as to make the comparison between the groups immediate and to identify which dimensions are most relevant for each cluster. Figure 14 shows the non-standardized version.

Cluster 0 is characterized by below-average values in the dimensions relating to perceived wellbeing and everyday actions, suggesting a lower overall sensitivity to the intangible or behavioral benefits of sustainability. This group therefore appears less inclined to translate its concern for the environment into established everyday practices. On the other hand, the positive values recorded for the willingness to have trees in private or public areas indicate that this cluster recognizes the importance of concrete and tangible actions that are directly perceptible in their own living environment. In other words, Cluster 0 seems to be more oriented toward forms of sustainability that have a visible and immediate return on the quality of the living space.

Cluster 1, on the other hand, stands out for its above-average values in relation to wellbeing and everyday actions, highlighting a more marked propensity to recognize the widespread and collective benefits of sustainability. Individuals belonging to this group are more willing to integrate environmental practices into their habits and perceive a positive impact on personal and social wellbeing. However, this cluster shows lower values in relation to the presence of trees in private or public contexts, thus demonstrating an orientation that is less tied to tangible aspects and more focused on overall impacts. Furthermore, the relatively more critical assessment of dependence on public incentives indicates a greater awareness of the structural limitations of forestry and biomass projects and the need for planning that is not based exclusively on subsidies.

A comparison of the two profiles reveals two complementary approaches to sustainability (Table 5).

This segmentation offers relevant operational insights for the design of communication policies and strategies. For Cluster 0, it is effective to emphasize the tangible dimension of interventions, for example by highlighting the direct benefits of urban forestry on living comfort and quality of daily life. For Cluster 1, on the other hand, messages focused on widespread benefits, the improvement of collective wellbeing and the importance of daily choices for sustainability may be more convincing.

Looking at the objectives in terms of application, the possibility of distinguishing between these two profiles allows for the calibration of tools and incentives in a differentiated manner: on the one hand, promoting visible, local-scale interventions, and on the other, encouraging practices and awareness campaigns that enhance the role of citizens as active actors in the ecological transition.

Through the application of cluster analysis, two distinct groups have been identified: the first, more pragmatic, linked to tangible and local benefits, and the second, more value-oriented, focused on widespread benefits and everyday practices. This analysis allows the differences that have emerged to be translated into concrete intervention strategies. For the pragmatic cluster, for example, forestry initiatives that is clearly perceptible in citizens' daily lives, such as planting trees in residential areas or redeveloping local green spaces, are more effective. For the value-oriented cluster, on the other hand, actions that strengthen the sense of collective belonging, such as awareness campaigns, educational programmes and messages emphasizing the overall environmental impact, have greater resonance.

4.6 Strategic analysis

Starting from Section 3.2, the next step is to collect the ratings provided on a scale of 1–10 by the experts (Supplementary Table S8). It should be noted that one limitation of these analyses is that they do not calculate a consistency index, as is the case, for example, with the Analytical Hierarchy Process (D'Adamo et al., 2024). The WSM gives the highest relevance to criterion C4, followed by C1 and C9. TOPSIS confirms the centrality of C1 and C4, followed by C9. VIKOR sees C1 and C9 in the lead, followed by C4. Consequently, in order to obtain a single summary of the three rankings, the average rank was calculated for each criterion, starting from the WSM, TOPSIS, and VIKOR rankings—Table 6.

The average ranking clearly identifies the priorities of C1 (area enhancement), C4 (environmental impact), and C9 (circular economy). Urban forestry is therefore interpreted as a true ecological infrastructure, capable of combining territorial regeneration and environmental mitigation. This approach is consistent with the European Green Deal and EU strategies on ecological transition, which emphasize the multifunctionality of green infrastructure and the role of the circular economy in resource management. The alignment between the priorities expressed by the experts and institutional priorities reinforces the legitimacy of the conclusions.

To verify the consistency between the methods, Spearman's correlation between the WSM, TOPSIS and VIKOR rankings was calculated. The values obtained are very high (ρ between 0.95 and 0.98), with maximums of ρ = 0.983 between TOPSIS–WSM and TOPSIS–VIKOR, and ρ = 0.950 between WSM–VIKOR. From a statistical point of view, the corresponding t-statistics (e.g., t = 14.17 for ρ = 0.983 and t = 8.05 for ρ = 0.950, with 7 degrees of freedom) are highly significant (p < 0.001). This confirms that the rankings do not diverge randomly, but are highly consistent and robust.

Criteria C7 (sustainable biomass) and C8 (energy independence) are, however, systematically marginal. This does not mean that these aspects are not important, but that experts perceive them as more complex to achieve in the immediate term, due to technological and logistical challenges and the perceived sustainability of the wood supply chain. These are medium- to long-term objectives, less tangible than urban regeneration or direct reduction of environmental impact. Overall, the panel shows a strongly “environmentally-oriented” approach: the mitigation of environmental problems, the circular economy and urban quality are seen as priority strategic levers. This confirms that urban forestry is no longer perceived solely as a landscaping intervention, but as a structural tool for public policy and urban transformation.

5 Discussion

The results of the survey provide a clear picture of citizens' perceptions of urban forestry and biomass use, highlighting points of contact and differences with respect to scientific literature. Overall, respondents expressed a very positive attitude toward forestry, evaluating it mainly in relation to urban regeneration and improved personal wellbeing, while the link with energy production was less immediate (Kabisch et al., 2015). The perception of the benefits associated with biomass use confirms this positive orientation, with high scores attributed to greenhouse gas emission reduction, clean energy production, and sustainable forest management (Foley et al., 2010; Panwar et al., 2011). However, citizens also show moderate awareness of the potential risks, particularly in relation to fine particulate matter and collection and transport costs (Ribeiro et al., 2011; Saidur et al., 2011). Willingness to pay did not show statistically significant differences between socio-demographic groups, although women and young people tend to be more likely to contribute financially to afforestation initiatives (Upham et al., 2007). This indicates that the perception of social and environmental benefits carries more weight than economic considerations.

Cluster analysis identified two distinct profiles of citizens: a pragmatic cluster, oriented toward tangible and immediate benefits, and a value-oriented cluster, sensitive to collective aspects and everyday practices (Höpfl et al., 2024; Baroni et al., 2025). The cluster analysis offers a useful but non-deterministic classification. The identified groups reflect similarities in selected perceptual variables, but they should not be interpreted as discrete categories within the broader population. Given that the segmentation is based on self-reported perceptions, the clusters are better understood as psychological orientations rather than observable behavioral types. The distinction between pragmatic and value-driven respondents thus captures differences in how individuals conceptualize sustainability rather than differences in actual behavior. Nonetheless, the segmentation remains practically relevant, as it supports the design of communication and governance strategies tailored to the specific sensitivities of each orientation. This segmentation offers operational insights for calibrating policies and communication strategies, combining visible local impacts with awareness campaigns on collective benefits. In summary, the results confirm the importance of urban forestry as a tool for wellbeing and regeneration, the recognition of the environmental benefits of biomass, and awareness of the risks associated with costs and emissions.

From a governance perspective, the distinction between pragmatic and value-driven orientations suggests the need for differentiated participatory strategies. Individuals with a pragmatic profile tend to respond more strongly to concrete, visible outcomes—such as improved services, cost efficiency or measurable environmental benefits—and may therefore be more engaged through targeted information on practical impacts and implementation procedures. Conversely, respondents with a value-driven orientation appear more sensitive to long-term sustainability principles, fairness, and collective responsibility, implying that participatory approaches for this group should emphasize co-creation, transparency, and inclusiveness. Designing communication and engagement strategies that address both orientations is essential to ensure broad-based support for urban forestry and biomass-related interventions. It is also important to interpret these segments as dynamic orientations rather than fixed categories. Individuals may shift between pragmatic and value-driven perspectives depending on the type of environmental intervention, their level of information, or the perceived proximity of the benefits. These orientations therefore represent flexible cognitive frames that evolve over time, highlighting the importance of continuous engagement and adaptive communication strategies to maintain public support. Original elements also emerge, such as differences by gender and age group and the segmentation between pragmatic and value clusters, suggesting the need for diversified policies that combine concrete actions and participatory tools (Ribeiro et al., 2011; Höpfl et al., 2024; Baroni et al., 2025).

The sustainable management of biomass and urban resources is a strategic lever for promoting environmental resilience and circularity (Mojtahezadeh et al., 2025). The integration of residues and efficiency models leads to more sustainable systems (Veliu et al., 2025). At the same time, social perceptions of urban forestry require attention (Kabisch et al., 2015). The adoption of integrated strategies, combining technological innovation, effective governance and citizen involvement, is essential to promote urban and rural sustainability (Sadhukhan et al., 2018). Sustainable choices in other sectors can also be made when a model of sustainable community is achieved, not only from an energy perspective but also in the sphere covering social and human aspects (Basilico et al., 2025a; D'Adamo et al., 2025). In this context, policies must consider both tangible and immediate aspects and values and social aspects, in order to strengthen public confidence and encourage the transition to circular and resilient practices.

6 Conclusions

This work highlights how urban forestry and the use of woody biomass are perceived positively and as highly relevant for improving quality of life, regenerating the urban fabric, and promoting environmental sustainability. The data collected show broad consensus: all dimensions considered score above 4 out of 5, a clear sign that the issue is far from marginal. Nevertheless, behind this general agreement lie interesting differences linked to gender, age, and, above all, to the value orientations of respondents.

Urban forestry is primarily perceived as a tool for territorial regeneration and collective wellbeing, while its connection to clean energy and everyday practices appears less immediate, although still evaluated positively. Women and younger respondents show greater sensitivity to behavioral aspects and a higher willingness to financially support forestry initiatives, whereas men and older respondents place more emphasis on structural aspects, stability, and collective benefits. Perceptions of biomass follow a similar pattern: its benefits, especially emission reductions and renewable energy production, are strongly acknowledged, but concerns remain regarding environmental and economic risks, particularly among women and older respondents.

The cluster analysis allowed us to go beyond socio-demographic categories, revealing the presence of two distinct profiles. On one hand, there is a pragmatic group, less sensitive to diffuse and intangible benefits but more inclined to value concrete and tangible interventions, such as planting trees in private areas or neighborhood spaces. On the other hand, there is a value-oriented cluster, characterized by greater attention to collective benefits, wellbeing, and daily sustainability practices, but less focused on tangible and immediate aspects.

These findings have significant policy and strategic implications. First, communication needs to be differentiated. For more pragmatic citizens, it is essential to stress the concrete and visible advantages of urban forestry, such as improved urban comfort, shading, and air quality. For value-oriented citizens, on the other hand, communication strategies should emphasize collective benefits, the reduction of environmental impacts, and the role of everyday practices. At the same time, policies should follow dual track: on the one hand, implementing local interventions capable of producing perceptible results in daily life; on the other, promoting awareness and education campaigns that reinforce a sense of shared responsibility and highlight overall benefits.

Special attention should be paid to the management of woody biomass which, while generally viewed positively, raises concerns related to particulate emissions, costs, and fire risks. Addressing these issues requires transparent responses and the adoption of innovative technological solutions—such as advanced filtration systems, sensor technologies for real-time emissions monitoring, and the use of short-supply-chain biomass—that can ensure both safety and efficiency while reducing dependence on public subsidies. Only in this way will it be possible to strengthen citizens' trust and ensure the long-term sustainability of projects.

Finally, the differences that emerged by gender and age suggest the importance of actively engaging women and younger respondents as promoters of sustainable practices, recognizing their role as key actors in the ecological transition, while also valuing the more structural orientation of older respondents by linking it to long-term, collective projects.

Overall, the results demonstrate that urban forestry and biomass valorization represent not only an environmental lever but also a strategic tool for urban and social policy. Institutions therefore could tailor their actions through differentiated approaches that respond to diverse sensitivities, integrating tangible, local interventions with broad-based educational and communication strategies. Only through this dual strategy will it be possible to strengthen citizen engagement and turn urban forestry into a shared practice, widely recognized as a common good. This work has some limitations. The analyses could be replicated in other geographical contexts and with different samples. Similarly, other analytical methodologies could be calculated and include environmental and economic assessments. In particular, these concepts could be explored within the growing theme of sustainable communities. Several technological and operational innovations could help address the critical aspects highlighted by respondents. Advanced particulate filtration systems can substantially reduce emissions during biomass combustion, while real-time monitoring sensors allow continuous tracking of air quality and plant performance, increasing transparency and institutional trust. Furthermore, the adoption of short, locally integrated biomass supply chains can minimize transportation impacts and reinforce the environmental sustainability of the entire process. Integrating these innovations into urban forestry and bioenergy initiatives may therefore enhance both the technical robustness and the social acceptability of future interventions.

This work contributes to SDGs 7, 11, and 12 by showing how sustainably managed biomass can support the transition to clean energy, how urban forests improve the resilience and liveability of cities, and how the circular integration of green space management and waste recovery promotes more responsible consumption and production. Ensuring a truly sustainable and socially supported green transition ultimately depends on citizen engagement and trust.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ID: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The present study was conducted as part of the PEACE (“Protecting the Environment: Advances in Circular Economy”) study, funded by the “Fund for the National Research Program and Projects of Significant National Interest (PRIN)” under investment M4.C2. 1.1-D.D. 104.02-02-2022, 2022ZFBMA4, supported by the European Union–Next Generation EU.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The manuscript reflects solely the views and opinions of the authors, who bear full responsibility for the findings and conclusions.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1712630/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdou, A. H. (2025). Servant leadership for hospitality sustainability: green psychological capital as a pathway to environmental citizenship behavior. Front. Sustain. 6:1535809. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1535809

Abdul, D., Wenqi, J., and Tanveer, A. (2022). Prioritization of renewable energy source for electricity generation through AHP-VIKOR integrated methodology. Renew. Energy 184, 1018–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.10.082

Ahmed, T., Ahsan, A., Khan, M. H. R. B., Nahian, T. K., Antar, R. H., Hasan, A., et al. (2024). Comprehensive study on the selection and performance of the best electrode pair for electrocoagulation of textile wastewater using multi-criteria decision-making methods (TOPSIS, VIKOR and PROMETHEE II). J. Environ. Manage. 363:121337. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121337

Albert, D. A., and Smilek, D. (2023). Comparing attentional disengagement between Prolific and MTurk samples. Sci. Rep. 13:20574. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-46048-5

Allam, Z., and Jones, D. S. (2021). Future (post-COVID) digital, smart and sustainable cities in the wake of 6G: digital twins, immersive realities and new urban economies. Land Use Policy 101:105201. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105201

Álvarez-González, A., Greque de Morais, E., Planas-Carbonell, A., and Uggetti, E. (2023). Enhancing sustainability through microalgae cultivation in urban wastewater for biostimulant production and nutrient recovery. Sci. Total Environ. 904:166878. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166878

Assies, F., Messmann, L., Thorenz, A., and Tuma, A. (2025). Life cycle sustainability assessment of substituting fossil based with biogenic materials: a German case study on drinking cups and insulation boxes. J. Ind. Ecol. 29, 1551–1567. doi: 10.1111/jiec.70067

Atiqul Haq, S. M., Islam, M. N., Siddhanta, A., Ahmed, K. J., and Chowdhury, M. T. A. (2021). Public perceptions of urban green spaces: convergences and divergences. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:755313. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.755313

Ayub, Y., Ren, J., and He, C. (2025). Biomass waste upcycling by synergistic integration of gasification, wind energy, and power-to-fuel production for sustainable cities. Energy 324:135978. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2025.135978

Baroni, M., Valdrighi, G., Guazzini, A., and Duradoni, M. (2025). Eco-sensitive minds: clustering readiness to change and environmental sensitivity for sustainable engagement. Sustainability 17:5662. doi: 10.3390/su17125662

Basilico, P., Biancardi, A., D'Adamo, I., Gastaldi, M., and Stornelli, V. (2025a). Socioeconomic dimensions of renewable energy communities: pathways to collective well-being. Util. Policy 96:102000. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2025.102000

Basilico, P., D'Adamo, I., Del Giudice, M., Di Santo, F., Gastaldi, M., Passarelli, F., et al. (2025b). Sustainable schools and knowledge management: driving urban and social transitions for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. doi: 10.1002/sd.70215

Benjumea Mejia, D. M., Chilton, J., and Rutherford, P. (2024). Collective urban green revitalisation: crime control an sustainable behaviours in lower-income neighbourhoods. World Dev. 177:106534. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106534

Bitzenis, A., Koutsoupias, N., and Nosios, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in production efficiency enhancement and sustainable development: a comprehensive bibliometric review. Front. Sustain. 5:1508647. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1508647

Bourdin, S., and Chassy, A. (2023). Are citizens ready to make an environmental effort? A study of the social acceptability of biogas in France. Environ. Manage. 71, 1228–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00267-022-01779-5

Bourdin, S., and Delcayre, H. (2024). Does size matter? The effects of biomethane project size on social acceptability. Energy Policy 195:114363. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114363

Byrne, N., Pierce, S., De Donatis, L., Kerrigan, R., and Buckley, N. (2024). Validating decarbonisation strategies of climate action plans via digital twins: a Limerick case study. Front. Sustain. Cities 6:1393798. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1393798

Cansado, I. P. D. P., Mourão, P. A. M., Castanheiro, J. E., Geraldo, P. F., Román-Suero, S. R., and Ledesma, B. L. (2025). A review of the biomass valorization hierarchy. Sustainability 17:335. doi: 10.3390/su17010335

Cascavilla, A., Caferra, R., Morone, A., and Morone, P. (2025). Experimental evidence on consumers' willingness to pay in the sustainable fashion industry. Sci. Rep. 15:38752. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-23008-9

Colasante, A., D'Adamo, I., Desideri, S., Iannilli, M., and Mangani, V. (2025). Environmental concerns in the fashion industry: a twin transition with the digital product passport. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 34, 9242–9256. doi: 10.1002/bse.70078

D'Adamo, I., Ferella, F., Fuoco, M., and Gastaldi, M. (2025). Social acceptance and economic impacts of biomethane: a resource for energy sustainability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 58, 221–236. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2025.06.021

D'Adamo, I., Gagliarducci, M., Iannilli, M., and Mangani, V. (2024). Fashion wears sustainable leather: a social and strategic analysis toward sustainable production and consumption goals. Sustainability 16:9971. doi: 10.3390/su16229971

Detrinidad, E., and López-Ruiz, V.-R. (2024). The interplay of happiness and sustainability: a multidimensional scaling and K-Means cluster approach. Sustainability 16:10068. doi: 10.3390/su162210068

Di Foggia, G., and Beccarello, M. (2023). Designing circular economy-compliant municipal solid waste management charging schemes. Util. Policy 81:101506. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2023.101506

Dmitrović, V., Ignjatijević, S., Vapa Tankosić, J., Prodanović, R., Lekić, N., Pavlović, A., et al. (2025). Sustainability of urban green spaces: a multidimensional analysis. Sustainability 17:4026. doi: 10.3390/su17094026

Duarte, D., Galhano, C., Celeste Dias, M. C., Castro, P., and Lorenzo, P. (2023). Invasive plants and agri-food waste extracts as sustainable alternatives for the pre-emergence urban weed control in Portugal Central Region. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 30, 605–619. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2023.2175737

Facendola, R., Ottomano Palmisano, G., De Boni, A., Acciani, C., and Roma, R. (2024). Determinants of the adherence to Mediterranean diet: application of the k-means cluster analysis profiling children in the Metropolitan City of Bari. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:13290909. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1329090

Fang, H., Xian, R., Ma, Z., Lu, M., and Hu, Y. (2021). Comparison of the differences between web-based and traditional questionnaire surveys in pediatrics: comparative survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e30861. doi: 10.2196/30861

Filho, J. J. D. S., Gaspar, P. D., Finisterra do Paço, A. D., and Marcelino, S. M. (2025). Governance-centred industrial symbiosis for circular economy transitions: a rural forest biomass hub framework proposal. Sustainability 17:5659. doi: 10.3390/su17125659

Foley, A. M., Ó Gallachóir, B. P., Hur, J., Baldick, R., and McKeogh, E. J. (2010). A strategic review of electricity systems models. Energy 35, 4522–4530. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2010.03.057

Galende-Sánchez, E., and Sorman, A. H. (2021). From consultation toward co-production in science and policy: a critical systematic review of participatory climate and energy initiatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 73:101907. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101907

Gomes, L., and Vale, Z. (2024). Costless renewable energy distribution model based on cooperative game theory for energy communities considering its members' active contributions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 101:105060. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2023.105060

Gould, R. K., Shrum, T. R., Ramirez Harrington, D., and Iglesias, V. (2024). Experience with extreme weather events increases willingness-to-pay for climate mitigation policy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 85:102795. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102795

Höpfl, L., Grimlitza, M., Lang, I., and Wirzberger, M. (2024). Promoting sustainable behavior: addressing user clusters through targeted incentives. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:1192. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-03581-6

Hunter, L. M., Hatch, A., and Johnson, A. (2004). Cross-national gender variation in environmental behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 85, 677–694. doi: 10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00239.x

Huntjens, P., and Kemp, R. (2022). The importance of a natural social contract and co-evolutionary governance for sustainability transitions. Sustainability 14:2976. doi: 10.3390/su14052976

Huttunen, S., Ojanen, M., Ott, A., and Saarikoski, H. (2022). What about citizens? A literature review of citizen engagement in sustainability transitions research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 91:102714. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2022.102714

Iç, Y. T., Çelik, B., Kavak, S., and Baki, B. (2022). An integrated AHP-modified VIKOR model for financial performance modeling in retail and wholesale trade companies. Decis. Anal. J. 3:100077. doi: 10.1016/j.dajour.2022.100077

Ikram, M., and Boudraa, C. (2025). The role of quality governance in achieving sustainable development goals in North Africa: an integrated decision-support system. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 6, 198–216. doi: 10.1016/j.susoc.2025.07.005

Ikram, M., and Nahdi, R. (2025). Toward sustainable development: Unfolding the nexus among exports, foreign direct investment, capital formation, natural resource rent, unemployment, and low-carbon transition in Morocco. Resour. Policy 102:105490. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2025.105490

Jozay, M., Zarei, H., Khorasaninejad, S., and Miri, T. (2024). Maximising CO2 sequestration in the city: the role of green walls in sustainable urban development. Pollutants 4, 91–116. doi: 10.3390/pollutants4010007

Kabisch, N., Qureshi, S., and Haase, D. (2015). Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces — A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 50, 25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2014.08.007

Keith, A. C., Warshawsky, N., Neff, D., Loerzel, V., and Parchment, J. (2023). Critical appraisal of electronic surveys: an integrated literature review. J. Nurs. Meas. 31, 580–594. doi: 10.1891/JNM-2021-0066

Keskin, B. (2025). Sustainable development goals performance measurement for OPEC member countries using gray relational analysis method. Front. Sustain. 6:1682731. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1682731

Kim, J. S., and Feng, Y. (2024). Understanding complex viewpoints in smart sustainable cities: the experience of Suzhou, China. Cities 147:104832. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2024.104832

Kiss, B., Sekulova, F., Hörschelmann, K., Salk, C. F., Takahashi, W., and Wamsler, C. (2022). Citizen participation in the governance of nature-based solutions. Environ. Policy Gov. 32, 247–272. doi: 10.1002/eet.1987

Kosta, A. D., Keramitsoglou, K. M., and Tsagarakis, K. P. (2025). Circular economy and sustainable development in primary education. Front. Sustain. 6:1414055. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1414055

Kostakis, I., Papadaki, S., and Malindretos, G. (2024). Analyzing the relationship between consumers' and entrepreneurs' food waste and sustainable development using a bibliometric approach. Front. Sustain. 5:13735802. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1373802

Kostakis, I., Papadas, D., Smol, M., and Tsagarakis, K. P. (2025). Circular economy policies for water and wastewater. Water Policy 27, 1141–1152. doi: 10.2166/wp.2025.077

Kostakis, I., and Tsagarakis, K. P. (2022). The role of entrepreneurship, innovation and socioeconomic development on circularity rate: Empirical evidence from selected European countries. J. Clean. Prod. 348:131267. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131267

Lazaroiu, A. C., Roscia, M., Lazaroiu, G. C., and Siano, P. (2025). Review of energy communities: definitions, regulations, topologies, and technologies. Smart Cities 8:8. doi: 10.3390/smartcities8010008

López, I., Goitia-Zabaleta, N., Milo, A., Gómez-Cornejo, J., Aranzabal, I., Gaztañaga, H., et al. (2024). European energy communities: characteristics, trends, business models and legal framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 197:114403. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2024.114403

Lyytimäki, J., Assmuth, T., Paloniemi, R., Pyysiäinen, J., Rantala, S., Rikkonen, P., et al. (2021). Two sides of biogas: review of ten dichotomous argumentation lines of sustainable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 141:110769. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.110769

Mashhadi, A. J., González, M. C. G., and Issa-Zadeh, S. B. (2024). The contribution of biomass energy on urban sustainable development: opportunities and challenges. Environ. Res. Technol. 8, 770–783. doi: 10.35208/ert.1563758