- 1School of International Service, American University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2National Seed Association of India, New Dehli, India

- 3Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, Springfield, IL, United States

- 4Family Farm Defenders, Churdan, IW, United States

- 5Carver Integrative Sustainability Center, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, AL, United States

Rather than treating symptoms of a destructive agri-food system, agricultural policy, research, and advocacy need both to address the root causes of dysfunction and to learn from longstanding interventions to counter it. Specifically, this paper focuses on agricultural parity policies – farmer-led, government-enacted programs to secure a price floor and manage supply to prevent the economic and ecological devastation of unfettered corporate agro-capitalism. Though these programs remain off the radar in dominant policy, scholarship, and civil society activism, but in the past few years, vast swaths of humanity have mobilized in India to call for agri-food systems transformation through farmgate pricing and market protections. This paper asks what constitutes true farm justice and how it could be updated and expanded as an avenue for radically reimagining agriculture and thus food systems at large. Parity refers to both a pricing ratio to ensure livelihood, but also a broader farm justice movement built on principles of fair farmgate prices and cooperatively coordinated supply management. The programs and principles are now mostly considered “radical,” deemed inefficient, irrelevant, obsolete, and grievous government overeach—but from the vantage, we argue, of a system that profits from commodity crop overproduction and agroindustry consolidation. However, by examining parity through a producer-centric lens cognizant of farmers‘ ability, desire, and need to care for the land, ideas of price protection and supply coordination become foundational, so that farmers can make a dignified livelihood stewarding land and water while producing nourishing food. This paradox—that an agricultural governance principle can seem both radical and common sense, far-fetched and pragmatic—deserves attention and analysis. As overall numbers of farmers decline in Global North contexts, their voices dwindle from these conversations, leaving space for worldviews favoring de-agrarianization altogether. In Global South contexts maintaining robust farming populations, such policies for deliberate de-agrarianization bely an aggression toward rural and peasant ways of life and land tenure. Alongside the history of parity programs, principles, and movements in U.S., the paper will examine a vast version of a parity program in India – the Minimum Support Price (MSP) system, which Indian farmers defended and now struggle to expand into a legal right. From East India to the plains of the United States and beyond, parity principles and programs have the potential to offer a pragmatic direction for countering global agro-industrial corporate capture, along with its de-agrarianization, and environmental destruction. The paper explores what and why of parity programs and movements, even as it addresses the complexity of how international parity agreements would unfold. It ends with the need for global supply coordination grounded in food sovereignty and solidarity, and thus the methodological urgency of centering farm justice and agrarian expertise.

Introduction

Though globalized food and agricultural systems have been intentionally packaged as a natural and self-regulating “global food system,” cracks reveal themselves as crushing ecological and health externalities, chronic agrarian and labor crises, and unprecedented agro-consolidation, as described by the United Nations and countless others (IAASTD, 2009; UNCTAD, 2013; IPES-Food, 2022; McGreevy et al., 2022). While dominant agri-food public, private, and philanthropy sectors' responses remain neoliberal and agro-corporate-led, diverse agrarian movements around the world tenaciously cultivate and clamor for alternatives to survive. Organizing around fair farmgate prices and cooperatively coordinated supply management—a combination deemed “parity” by U.S. farm justice movements—these pillars protect agrarian livelihoods, land retention, and evasion of agro-corporate dominance. U.S.-based farm justice movements effectively transformed farm policy into a mechanism of staving off agro-industry capture of value, demanding programs to prevent the pitting of farmers against each other in a race to bottom of farmgate prices, regionally, domestically, and internationally.

Recently, the food price problem, wherein consumers and import-dependent countries cannot afford nourishing food, has garnered necessary attention and alarm. Yet, subsequent interventions often compound the parallel, but largely invisible, farmgate price problem. From the vantage of neoliberal logic, interventions toward “parity” seem a radical disruption of a naturalized, freed, self-regulated market. From many sectors, perspectives, and fields, agricultural parity policies and principles seem preposterous (Graddy-Lovelace and Diamond, 2017). The paper concurrently explores the flip side of this antipodal subject: how farmers across many places and times demand their agricultural products be valued fairly at markets. Senior co-authors Naylor, Edwardson Naylor, and Wilson provide a grassroots farmer analysis of the disconnect between what a farmer must pay for her purchases vs.s the prices she receives for her produce.

Technically speaking, calculated by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), the parity ratio is the relationship between “prices received vs. prices paid” for domestic farmers. Though the current dominant agricultural economic expectation is that farmers can garner income from increased exports, this paper explores how managing markets, like all big industries, is especially needed for farms. Otherwise, the secular downward pressure on farmgate prices leads to bankruptcy, land loss, rural outmigration, land concentration, and market consolidation for those trying to make a living from farming itself. At an international scale, the regulatory mechanisms of the World Trade Organization (WTO) continue to relegate price discovery to international supply and demand as determined by the speculative trading of futures contracts and eliminating tariff measures to protect domestic systems of agriculture. This penalizes domestic governance support for “parity” (price floors, supply management, quotas, grain reserves). For countries other than the dominant grain exporters, WTO governance has fostered dependencies on surplus commodity crop imports–just as farmers around the world warned in their decades of protests. The current global food crisis, reeling from disrupted supply chains, demonstrates the risky consequences of acute import dependence. From dominant agro-economic perspectives of market self-regulation, parity policies and orientations seem radical.

Methodologically, this article chronicles and contextualizes farm justice movements through community-led action-research projects with esteemed, grassroots agrarian organizations, elders, and community leaders. Durable agricultural policy requires research methodologies that are led by agrarian practitioners and coalitions struggling for social, ecological, and economic wellbeing for those working in agriculture or living in rural communities. From the vantage of those cultivating food and stewarding land, governmental interventions into the agri-food system have long been pervasive. In fact, most of these interventions over the past 70 years have favored and enabled agro-corporate consolidation that now undergirds the current extractive nature of agri-food systems. As rural economies become de-capitalized, the fabric of society begins to tear in these areas and beyond. Considering this grand tendency, of agro-capitalism unchecked driving industry consolidation, parity principles and programs—updated for racial and gender equity and climate resilience—become imperative, and from the perspective of diverse farmer livelihoods: common sense.

Shared imaginaries have been a consistent element throughout the long history of the farm justice movement. Historically, the voices of powerful figures have framed historical narratives that exclude and marginalize key activists, practitioners, and knowledge-holders who are not in positions of power. This paper seeks to shed light on the histories that have strengthened dominant hegemonies and raise awareness about the deeply entrenched inequalities and inefficiencies of dominant food systems. By educating scholars and activists about the way parity once served farmers and strengthened domestic food systems, and by connecting these histories to India's case, this research serves as an antecedent to policy action.

The interconnected agrarian histories described in this paper impact and continue to form each other, regardless of geographic distance. Policymakers have become disconnected from those who are working the land and “feeding the world”. Proposed solutions distract consumers, policymakers, and the public from the root causes of overproduction, unfair wages, and large-scale disconnect from the land. For example, shaming consumers to take individual action by shopping local, supporting small growers, visiting farmers markets, and only buying organic produce disguises the underlying issues. These individual-targeted approaches offer a solution which only wealthy individuals can access, perpetuating a culture of food waste and further cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, parity principles are inherently rooted in principles of social justice and benefit both producers and consumers. Unlike consumer-focused solutions, supply management levels the playing field and addresses inequality of access to nutritious foods. Parity is class-conscious and in solidarity with consumers, but actualizing these principles will require a structural rethinking of food systems.

Parity principles are parallel to and inextricable from the urgent need for a living minimum wage for workers at large. In a transformed agri-food system, the worker is guaranteed a fair wage, while the farmer earns and is guaranteed a fair price, thereby “lifting everyone up” (Chappell, 2020). Importantly, the cost of a fair farmgate price floor would be shouldered primarily by dominant agro-food purchasers—nearly all of whom are corporations with ample resources to remunerate farmers, and their employees, fairly. The dominant agri-food model pits farmers against consumers, but the parity movement has long asserted solidarity with workers' struggles—a key tenet of the 1980s farm justice movement and a core tenet of current iterations of parity advocacy, such as Patti Naylor's recent local op-ed (Naylor, 2022).

Parity itself remains surprisingly simple as a concept and policy orientation: minimum support price (adjusted for inflation), supply management, grain reserves. However, the logistics of its implementation must be updated for the twentifirst century, keeping in mind agrobiodiversity, climate resilience, and racial, gender and labor equity, which requires teams of skilled people coordinating quotas, grain reserves, non-recourse loans, trade parameters, and farmer outreach. Research and extension are needed for analyzing, implementing, honing, and actualizing parity at multiple scales, for multiple crops, landscapes, and agricultural contexts across the U.S. and beyond.

From an economic perspective, without a parity safeguard, agro-corporate buyers inevitably drive farmgate prices down, farmers go bankrupt, and those desperate to remain on land degrade it with overproduction. Industrial agriculture wreaks ecological havoc, so an environmental movement not unpacking root causes of agricultural overproduction misunderstands the situation: industrial agriculture is the logical result of letting markets organize agriculture. The urgency of parity is in the exporting countries. Relatedly, it is also a question of if and how countries have the right to block cheap imports to safeguard their own producers, farmers, fishers, and rural communities. Currently, an historic convergence grows around critical food studies—from environmental to labor, racial justice to climate, health, civil society, and policymaking. This paper aims to facilitate dialogue with these movements to show the primary contradiction of agriculture, which undergirds the myriad salient secondary contradictions. It describes the generations of historical grassroots agrarian movements and subsequent governmental programs that arose to address the primary contradiction of industrial agriculture's wreckage of livelihood and land.

The paper begins by defining parity, its origins, and its implementation in the cases of the United States and India, with attention to their interconnected roots. The following section explains why supply management is needed for agricultural goods, particularly given environmental and social justice impacts of the status quo, including issues of wasted food, soil degradation, hunger, and overproduction. A description of the methodological development of the community-led research agenda continues to inform broader advocacy involvement and calls for future research. The paper then outlines the role of multilateral institutions like the World Trade Organization in the erasure of parity in pursuit of market liberalization, and the direct consequences for farmers globally. A historical overview of the rise and fall of parity programs follows, describing the marginalized farmer-led advocacy and coalition building that emerged in response. These movements inform an analysis of the reliance on subsidies, helping to distinguish between holistic supply management and direct payments, which have compounded consolidation and commodity overproduction and further marginalized small, medium, and BIPOC farmers. Ultimately, the paper concludes by linking the movements through the shared threads of justice, dignity, and radical imaginaries.

The urgency of food system transformation

Agricultural parity–as a suite of programs or even as a set of principles–comprised a central tenet of the U.S Farm Bill but is currently absent from most federal or state government farm policies or goals. When vestiges of it do persist–in the case of sugar or cotton tariffs for instance (Powell and Schmitz, 2005; Beckert, 2015); – it is usually convoluted and even corrupted from the original context of countering unfettered agro-capitalism. Farmgate price floors seem peripheral in the face of worldwide monumental crises, but a deep look at global catastrophes reveals their convergence in the environmental, social, economic, and political externalities of high-input, corporate-dominated, industrialized monocultural commodity crop (over)production. An even deeper look shows how agrarian crisis drives, results from, and exacerbates these externalities.

Most notably, in 2021, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change declared a ‘code red for humanity’ demanding immediate action and attention toward our planetary boundaries. 2022 was characterized by the continuation of a global pandemic, coupled with record amounts of unpredictable severe weather events, extreme heat, and momentous soil degradation (IPCC, 2022). The globalized food system is deeply intertwined within these climate and public health intersections, making it a critical nexus for radical transformation. Global industrial monocropping and markets contribute massively to climate change, and at the same time, are extremely vulnerable to its impacts. While dominant agri-food policies often assume and champion limited government intervention, it is pertinent to note how much calculated action and protective measures tend to uphold the agro-corporate-serving status quo, both in the United States and globally.

India serves as a real-time case study of the tussle between the forces of agro-capitalism and farmers. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) system is the sole safeguard for farmers, which offers economic dignity through fair prices. While farmers want fair price/MSP systems to be written into law, corporations are lobbying through three farms laws, to push for tax-free corporate markets, farmgate sales to corporations, the end of grain stocking limits, and the expansion of contract farming. They hoped to dismantle grain reserves and MSP, while simultaneously pushing for further market liberalizations. The MSP system, borne out of USAID (United States Agency for International Development) as a mechanism to safeguard farmers from predatory capitalism and the promotion of Green Revolution technologies, has been a cornerstone of Indian agricultural policy (Damodaran, 2020). Centuries of British exploitation destroyed India's economic and agrarian resilience. Indian farmers were forced to grow commodities like indigo, cotton, opium, and tea for British markets, which left less land for food crops. The colonial policies are directly responsible for over 30 famines during the British Raj. By the time India achieved Independence, much of its rural agrarian resources had been enervated, and the Indian government needed food aid: wheat and paddy, to ensure food security. Meanwhile, the US government had been monitoring Indian weather and crop patterns and used the PL-480 food assistance program as food diplomacy.

The program provided critical famine aid to India, providing a temporary solution to the lack of food security in the country. The aid was on a limited basis, however, as the US government used its food aid as leverage to coerce the Indian government to implement agricultural reforms that would lay the foundation for the Green Revolution. It began by funding agricultural research, setting protocols for agrarian legislation, and then introduced agrichemicals and Green Revolution seeds. Punjab was the first state to undergo this US-backed project of industrial agriculture. Agrichemicals were freely spread over the region, sometimes by fly-by-night operators (Shiva, 1989). Traditionally, farmers in Punjab grew native long stock wheat in certain areas, while rice/paddy was rare. When irrigation technology was introduced through the Green Revolution, however, Punjabi farmers were persuaded to grow paddy on a mass scale.

Minimum support prices were offered for wheat and paddy through government regulated market yards (APMC mandis) because Punjab did not have buyers for paddy and the new varieties of foreign wheat. Paddy/rice was not part of the Punjabi diet and was agronomically not suited to Punjab. It is only with the advent of electricity, tube wells and canals, that paddy cultivation was possible in Punjab. Once the MSP was set, the government stepped in as a buyer. It bought most of the produce for its food reserves and public distribution system. As years passed, food production in India increased and the food prices especially for MSP crops like wheat and rice started to fall. The case of paddy and wheat are important because they began to be grown by farmers in other parts of the country as well.

Over time, millions of Indian farming families have benefitted from this scheme. In 2022, Indian states of Punjab and Haryana where the MSP program and government grain procurement are still active, have the highest per-capita agrarian incomes (Tribune News Service, 2022). But just as corporations dismantled the parity program in the U.S., new attempts are being made to erase its living memory too. The three farm laws were one such attempt.

Within the U.S. context, Farm Bills consistently eroded market management, following pressures from WTO, and shifted price supports to subsidies, most often to the wealthiest and largest farm owners, thereby exacerbating racial and class disparities among landowners. Through chronically low global commodity crop prices, coupled with rising costs of production, farmers are pressured to “get big or get out.” Many have been forced out of agriculture altogether, while others must produce more and more just to stay afloat. This system pollutes ecosystems, destroys rural communities, and contributes to food waste, but benefits corporate agri-business. Massive corporations can cheaply buy feed grains to funnel into feedlots and Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), thereby further contributing to overproduction of meat within the U.S. and crushing more sustainable methods of livestock production through subsequent cheap pricing. Treating food as a commodity overlooks the coercive nature of market forces guided by corporate interests.

In their argument for an updated version of supply management and parity pricing, Schaffer and Ray (2018) describe the economic characteristics of food that distinguish it from other commodities operating in a deregulated free market system. The balance of supply and demand are skewed in the case of agricultural goods because of people's fundamental need to consume them. In other words, consumer demand for food is inelastic, meaning the cost has little impact on the decision to buy. If prices decline, demand will remain relatively steady. In a free-market system guided by neoliberal priorities, downward pressure on prices leaves farmers unable to cover production costs and deprived of a decent standard of living. In the case of manufactured commodities, corporations can respond to mismatched supply and demand by reducing production, idling capital, and laying off workers, or increase demand for their products by intensifying their marketing efforts or buying up their competitors. However, a low-price elasticity of total agricultural crop supply leads farmers to respond to falling prices by producing more, to cover their fixed costs. As a result, producers flood the market and further depress prices. Supply coordination would not only allow farmers, both domestically and globally, to capture fair prices, it would reduce surplus production and supply-demand mismatch.

Overproduction coupled with little to no supply management policies also plays a significant but largely un-analyzed role in the notorious problem of wasted food. The USDA calculates that nearly 40% of the national food supply turns into waste (USDA-Food Waste, 2022). On an international scale, studies conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2022) conclude that up to one-third of food is lost or wasted at some point in its journey from field to plate (FAO, 2022). Greater social and political consciousness surrounding the ecological impacts of discarded organic matter emitting methane from landfills, or imperfect produce never reaching supermarket shelves for aesthetic reasons, has led to consumer-side interventions that place the burden on the individual. To combat this misplaced responsibility, Gascón (2018) points to the power imbalances inherent in the “hegemonic agri-food model”. In doing so, the author shifts food waste responsibility toward a system controlled by corporate interests that marginalize producers. This is a key analytic step, but going one step further, a parity history elaborates how farm policies to curb commodity crop glut and supply-demand mismatch have been eroded, penalized, and forgotten. Interventions to reduce wasted food that overlook the systemic injustice may inadvertently perpetuate cycles of overproduction. Agricultural parity suggests policy interventions aimed at eliminating root causes of wasted food, rather than simply treating the symptoms of a wasteful and extractive food system.

Additionally, although the U.S. and India are at different levels of economic development, farmers in both countries face similar consequences of broken agro-food systems. In India, farmers struggle with rising debt, falling incomes, suicide, drug addiction, and domestic violence as a by-product of faulty economic policies (Singh, 2022). In the U.S., rural sociologists and a few journalists and analysts have chronicled the devastating social impacts of the farm crisis on rural communities (Loboa and Meyer, 2001; Walters, 2003; Chrisman, 2019; Scheyett and Bayakly, 2019), and chronicle “hollowed out heartlands” (Edelman, 2021). But more investigation is needed on how decades of farmers' financial fallout led to a cascade of land loss, unemployment, hospital closures, mental health crises, and addiction. (Naylor P. E., 2017) Iowa op-ed laments the crushing experience of farmers who cannot “make it in the game,” to quote a USDA official. Parity—as a set of principles and programs–offers an intervention to both cases of wrenching rural decline.

Methodology

This piece is informed through a decade-long practicum with graduate researchers, agri-food experts, and agrarian justice leaders at American University's School of International Service. This practicum, now in its ninth year, has generated dozens of mixed-methods, multimedia, multi-disciplinary deliverables. From documentary shorts to statistical analysis, from congressional briefings to ArcGIS maps, the practicum has also informed analyses about community-based research methodologies (Orozco et al., 2018; Fagundes, 2020; Montenegro et al., 2021; Watson and Wilson, 2021; Auerbach et al., 2022). In 2022, AU SIS “Agricultural Policy and Agrarian Justice” practicum researchers visited leaders and members of The Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund (FSC/LAF) in Alabama and Mississippi, farm justice leaders of the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC) in rural Iowa, and Rural Coalition's member organization World Farmers, a refugee and immigrant farming group in Massachusetts. Using these methodologies as a baseline, three students, including co-author Andrea Jewett, traveled with Graddy-Lovelace (2021b) to Alabama and Mississippi to work with and learn from the FSC/LAF (O'Brien, 2017). Discussions of parity pricing and supply coordination served as throughlines of the discussions of member outreach and ground-level implementation of Farm Bill policies. Cooperative organization plays a key role in ensuring that Black farmers capture fair prices when deprived of federal assistance.

Simultaneously, Graddy-Lovelace and three student researchers, including co-author Jacqueline Krikorian, traveled to Lancaster, Massachusetts to visit Flat Mentors Farm and learn from World Farmer's founder Maria Moriera, Executive Director Henrietta Isaboke, and Policy Director Jessy Gill, with the objective of honing market-based research for program farmers to better support small farm businesses. Finally, four students, including co-authors Avinash Vivekanandan and Katherine Stahl, traveled across Iowa, and conducted interviews with farm justice leaders, including George and Patti Naylor, Brad Wilson, and Larry Ginter. These humbling and inspiring conversations with lifelong activists shed light on the socioeconomic decline of rural and small-town America, the deep pain of losing the family farm, and how parity offers a chance at a more holistic and healing farming future. In addition, India agricultural policy expert Devinder Sharma spoke on the fight for a minimum support price (MSP) in India (Sharma, 2021), bringing an international perspective for the global fight for farm justice. Together with the valuable guidance, support, and editing expertise of community partner and co-author Indra Shekhar Singh, the Iowa research team produced a 42-min documentary intended to make the story and economic underpinnings of parity more broadly accessible to all, rather than just those in academia. Included are first-hand accounts of the environmental impacts exacerbated by the “get big or get out” mindset farmers had to adopt as price floors fell and eventually disappeared altogether (Naylor G., 2017). Parity, as discussed in the film, emerges not as a utopian vision, but as a pragmatic and precedented policy alternative with the potential to reduce rural poverty by revitalizing farming communities, reverse biodiversity loss stemming from fencerow-to-fencerow farming of GM crops, reduce agriculture-related environmental pollution, and bring people back to the land.

This article is most closely influenced by the lessons and histories passed down from farm justice leaders and legends and exists within the broader context of the decade-long research. Their commitment to the movement, tenacity to work the land, and selfless leadership informs understandings of intersectional agricultural policy. Importantly, resistance to the global food system has not historically been documented with plentiful or honest visibility. As a result, oral histories, historical archival analyses, and intuitive learning through relationship with land can support the formation of intersectional agricultural policy. Most of the knowledge that practitioners have is stored within their own selves and shelves, in their lived experiences, movement-held home and office archives, and communal oral histories rather than written, published literature (Riley and Harvey, 2007). Faced with a system that has commonly discouraged the participation and value, BIPOC, immigrant, and marginalized farmers worldwide have grown distrustful of agri-food systems to provide them with fair and dignified treatment. Researchers, farmers, practitioners, and experts have come together to co-design and co-author this open access article, despite differences in perspectives and experience. This paper represents months of dialogue and co-creation which has converged as an antecedent to largescale policy research and design, rooted in pillars of agro-economic justice.

Farm justice in a globalizing world

With fair wages for farmers being a seemingly ‘common sense’ solution, what obstacles lie between its implementations? For one, parity principles of supply management and price floors are effectively criminalized by the WTO. These measures are considered highly trade-distorting, and as such, are subject to reduction. The world price is “sacred” for the WTO, as domestic price floors set too high above the world price must be reduced in accordance with Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) regulations. Importantly, the world price is effectively set by massive agricultural corporations, and this control generally keeps the world price for products at a level below the cost of production (Ritchie and Dawkins, 1999, 2000). AoA regulation prevents nations from implementing domestic price floors at parity levels, hampering the ability of domestic policy to adequately support small and family farmers. Supply management programs are also considered market distortion by the WTO, and the last vestiges of US supply management were eliminated in the 1996 Farm Bill to be in line with WTO regulations (Murphy et al., 2005). The result has been US farm policy that hurts both US and non-US farmers alike. As Murphy et al. (2005) explain, this result occurs because supply management programs “helped to correct a structural flaw in agricultural markets:” too many sellers and not enough buyers – commodity buyers hold too much power, and sellers (farmers) too little. In 1996, agribusiness lobbyists (and neoliberal economic philosophy) were finally successful in eliminating government intervention, which had helped foster an allegedly free market. Following this, “US agricultural prices went into free fall,” creating a situation where commodity buyers could purchase products under the cost of production. Since the mid-twenteeth century, the U.S. has been accused of commodity crop ‘dumping’: exporting surplus commodity crops below cost of production and/or below farmgate prices of importing countries; undermining small-scale farmer viability globally. Since the 1996 Farm Bill, levels of dumping have risen across the board, harming producers around the world (Murphy et al., 2005; Murphy and Hansen-Kuhn, 2020). Only growers with large economies of scale garner reliable income from export markets, and the profit margin remains razor-thin and vulnerable to trade stand-offs.

Problematically, the WTO similarly discourages grain reserves through its insistence that domestic support does not distort trade. Grain reserves pull excess supply off the market to prevent prices from falling too low, and release supply into the market when prices rise too high. Reserves are an important tool to combat food shortages and protect human health; a mechanism to ensure more stable commodity prices, thereby benefiting consumers and producers; and a means to limit private sector control of agriculture (Murphy, 2009). A lack of reserves can exacerbate country-level vulnerability to supply chain disruptions, volatile commodity prices, and climate shocks that affect crop yield (Wright, 2009). The logic behind reserves is ancient, and the idea of stockpiling supply in good crop years, to safeguard against famine in bad years, is seen across ancient civilizations (Murphy, 2009). However, WTO regulations make public reserves difficult to establish and operate. Although the WTO does not outright ban reserves, it makes them tricky to even conceptualize. Reserves are key for effective price supports (Murphy, 2010; Murphy and Lilliston, 2017), exemplified by India's case. Cutting production without reserves places societies in vulnerable positions, heightening food insecurity. The WTO is not the only barrier to public grain reserve success – grain reserves require the public to place a great deal of trust in their government's ability to manage them adequately and equitably, and that trust is often, for good reason (authoritarian regimes, state-sanctioned racism, corporate corruption), lacking. More research is needed on reserve viability given this lack of trust.

Although the AoA fails to benefit farmers in the U.S. and abroad while pouring benefits upon wealthy multinational corporations, the WTO heavily favors highly industrialized nations of the Global North (Díaz-Bonilla et al., 2003; Clapp, 2006; Wise, 2009; Burnett and Murphy, 2014). Structural Adjustment Programs, introduced by International Financial Institutions, encouraged the production of commodity crops for export, neglecting local food baskets, and “made poor countries dependent on a volatile global market for their food” (Shattuck and Holt-Gimenez, 2010). Economically poor countries evolved from net food exporters to net food importers because of SAPs and influxes of low-priced Northern foodstuffs (Joseph, 2011).

Although all member nations were required to reduce “trade-distorting” support (by 20% for developed countries or 13% for developing), reduction commitments were tied to support levels between 1986 and 1988 – a period when US and EU farm support was very high compared to the rest of the world. Thus, developed nations account for 95% of current global “total aggregate measure of support” (AMS) entitlement, creating an artificial comparative advantage for developed country agricultural producers, and displacing farmers in developing countries (Sharma et al., 2021).

It is pertinent to note that farmers and peasants in the global movement La Via Campesina (LVC) have been calling for the WTO to get out of agriculture altogether, to dismantle the Agreement on Agriculture, and to remove agriculture from all Free Trade Agreements. Food production must meet the needs of local and territorial consumption first, protecting farmer livelihoods and the natural environment. LVC calls for governments “to build public food stocks procured from peasants and small-scale food producers at a support price that is just, legally guaranteed and viable for the producers,” reflecting the principles of parity (LVC, 2022). Importantly, the WTO is not part of the United Nations system. It has emerged as an unduly powerful global institution, yet unaccountable to governments, elected officials, or democratically selected representative bodies. Rather, governments must adhere to WTO regulations or face steep punitive retribution. Updating agricultural parity policies requires multi-scalar, integrative, and responsive international supply, pricing, and trade coordination, aiming for agrarian wellbeing and diversity among all trading partners, as well as agroecological, labor, and health safeguards (Fakhri, 2020). In short, international parity policies, be they bilateral, multilateral, or regional, would need to be grounded in agrarian solidarity (Graddy-Lovelace and Naylor, 2021).

Although the stated intention of the AoA is to allow countries flexibility in designing and implementing domestic agricultural policies, the reality is a system that favors big agribusiness and highly industrialized countries. Family and smallholder farmers across the globe, including in the U.S., fail to benefit from domestic policies that offer a band-aid, rather than a solution, to the problem of low commodity prices (as explained by such agricultural policy analysts as Ritchie and Ristau (1987) in their “Crisis by Design” report in 1987). Despite well documented rising farmer debt, for decades U.S. farm policy has “patched together emergency fixes” (Hansen-Kuhn, 2020) while upholding the status quo. Fair prices for agricultural products, reliably maintained at a level above the cost of production, have the potential to radically change our global food system. For parity pricing to occur, however, the regulations of the AoA need updating to reflect how markets fail farmers and consumers through encouraging over-production and environmental externalities, prices that routinely fall below the cost of production, and relatively cheaper Northern products outcompeting local goods in foreign markets. Farm parity policies, in all their diversity, have the potential to offer alternatives to the dominant neoliberal paradigm. In the case of agriculture, the pressure for countries to submit to an allegedly self-regulating “free” market forces producers to sacrifice ecosystems and rural communities for the sake of global competitiveness. On a micro-scale, this hegemonic paradigm requires that farmers reject their personal belief systems just to maintain their livelihood.

Our global system and the many powerful multilateral institutions and entrenched belief systems that uphold it create an obvious barrier to parity principles being incorporated in domestic agricultural policy. Less obvious, however, is the unintentional role that even environmental movements for agri-food systems reform can play in upholding the status quo. These movements often frame farmers as the rich and powerful beneficiaries of massive subsidies, bank-rolled by the poor American taxpayer. In doing so, these movements turn the public against farmers and obfuscate the truth: farmers are not “subsidized”. Rather, massive multinational agro-corporations are subsidized and profit greatly from the entire system that has made subsidies necessary in the first place. Many food and environmental movements pin the blame for overproduction on U.S. agricultural subsidies, which also creates the illusion that farmers actively choose to overproduce and engage in farming practices with significant ecological externalities. This framing falls short analytically. Many scholars are following the lead of civil society, which follows the lead of frontline communities in lambasting agro-corporate consolidation and impunity. For instance, Davis Stone Glenn (2022) recent book describes the agri-food corporations' systemic appropriation of value (2022). Going further, however, a farmer-centric perspective reveals how “subsidies” remain symptoms of the political economic problem. Getting rid of subsidies is frequently framed as a fix-all but fails to address the root cause of so many agriculture-related issues: chronically low prices upheld by a global regime of corporate behemoths. Fixing the multitude of issues within our global agri-food system will require radical solidarity within and between various movements, and it is critical for these movements to advocate for policy solutions that will support and diversify farmers – and a whole new generation of growers, agricultural cooperatives, and coalitions.

US farm justice through parity

Prior to the invention of the parity market management programs in the 1930s, there were six decades of market failure and cheap farm prices, with occasional brief exceptions (Schaffer and Ray, 2006). The failure to protect farmer livelihoods spurred widespread mobilization from coalitions of family farmers, especially in the Midwestern United States, who coordinated advocacy efforts, political mobilization, and built alternative systems (Schutz, 1986; Krebs, 1992). Importantly, the Farmers' Alliance rose in the 1880's, and shortly after welcomed women members, supporting the creation of the Colored Farmers' National Alliance by African American farmers in the South (Ness, 2004), signaling the beginning of inter-racial collaboration and a broader social movement. In addition, one of the major proposals of the Farmers' Alliance and the People's Party was the Subtreasury Plan, which would set up government warehouses to store a farmer's crop on which 80% of its value could be borrowed from the government to be paid back within a year (Ness, 2004). This would avoid having to sell at the disastrously low prices at harvest. The Subtreasury Plan provided a model for subsequent Non-Recourse Loan price support mechanisms of the New Deal. The groups also formed cooperatives for self-help, a strategy that continues to strengthen rural communities today. After the turn of the century, farmers formed the National Farmers Union, the Non-Partisan League, and the Farmers Holiday Association, which confronted Congress and the President on the need for fair prices (Graddy-Lovelace, 2019).

U.S. parity programs were designed to address a chronic failure of markets: “the lack of price responsiveness” of both the supply and the demand for aggregate agriculture (Schaffer and Ray, 2006). The programs managed farm markets through two main mechanisms: minimum farm price floors, backed up by supply reductions as needed, and maximum price ceilings, which triggered the release of strategic reserve supplies, balancing supply and demand (Ray, 2004). Chronically low prices were not just a problem during the Great Depression, when the programs were invented, but had occurred, with occasional exceptions, for six decades prior (Schaffer and Ray, 2006). The lack of price responsiveness for agricultural products has continued with few exceptions ever since (Schaffer and Ray, 2005), and the USDA and the Congressional Budget Office project continuations of low farm prices for another 10 years (USDA-Office of Chief Economist, 2022).

The parity programs achieved fair farmgate prices and reduced overproduction when well managed. The peak of the program occurred from 1942 to 1952, when price floors for “basic” and “nonbasic commodities” were set at 90 or 85% of parity (Bowers and Rasmussen, 1984). U.S. agriculture achieved 100% or more of the parity standard, also known as the parity ratio, calculated by dividing prices received by prices paid (USDA-NASS, 1955). During these years 100% of parity prices were generally achieved for most of the crops covered, including fruits and vegetables (USDA-NASS, 2022).

The following metrics further showcase how parity programs supported farmers and increased their chances of success. Farm sector debt, which peaked at $185 billion in 1932, was cut in half (down to $89 billion) by 1952. National net farm income rose from $35 billion in 1932 to $129 billion in 1952 (USDA-ERS, 2022e). Return on equity, measured as net farm income divided by equity, increased from 6% in 1932 to 12% in 1952 (USDA-ERS “Value Added”, US Census, 1949 and Gardner, 2006a,b). This brought it more in line with that of other industries, such as farm implement manufacturers, food processors, food chains, restaurants, and tobacco and beverage companies, each of which also tended to be in the double digits (Letter, 1958). Average cash receipts for food grains, feed crops, and oil crops increased by 133% (1920-32 average vs. 1942-52 average, adjusted for inflation in 2020 dollars). Fruit, vegetable, melon, and nut cash receipts increased by 99%. Livestock, poultry, and related products cash receipts increased by 136% (USDA-ERS, 2022b). Between 1940 and 1950, the percentage of full and part owner farms also increased by 6% nationwide (USDA-NASS, 1969). For nonwhite farms in the South the increase was 12%, and this was the only increase in ownership between 1920 and the 1990s (USDA-NASS, 1969).

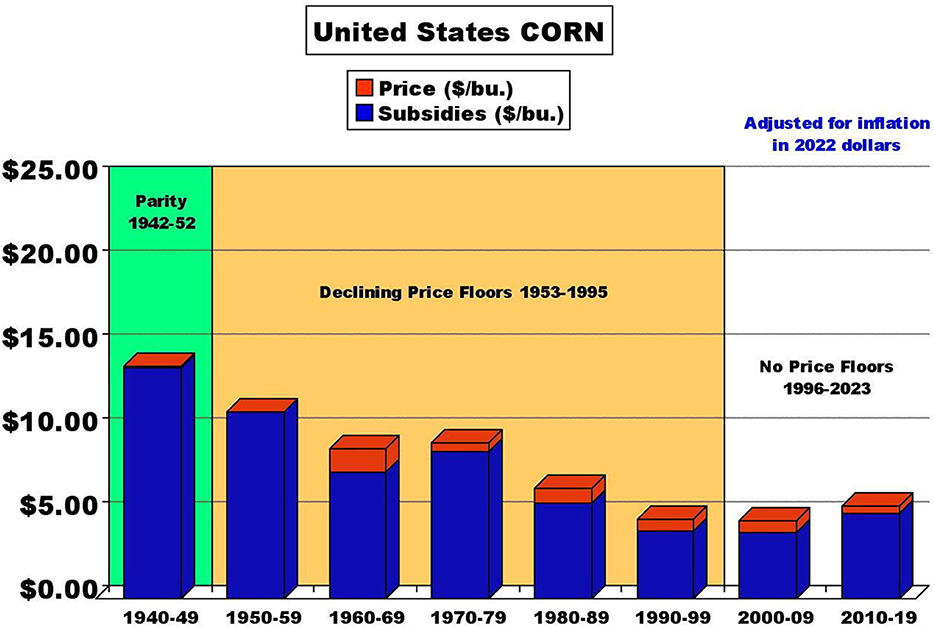

Tragically, the rise to the parity years was followed by a 40-year period of lowering minimum farm price floors (“loan rates”), after which the programs were eliminated (Ward, 1976 and Ray, 2004). For example, price floors for corn were lowered incrementally, from 90% of parity in 1942 to just 31% in 1995, after which they were totally dismantled (Sumner, 2006) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. As parity eroded, price floors for corn were gradually reduced until finally being eliminated in 1996. This graph shows declining prices for corn, as they relate to declining government support.

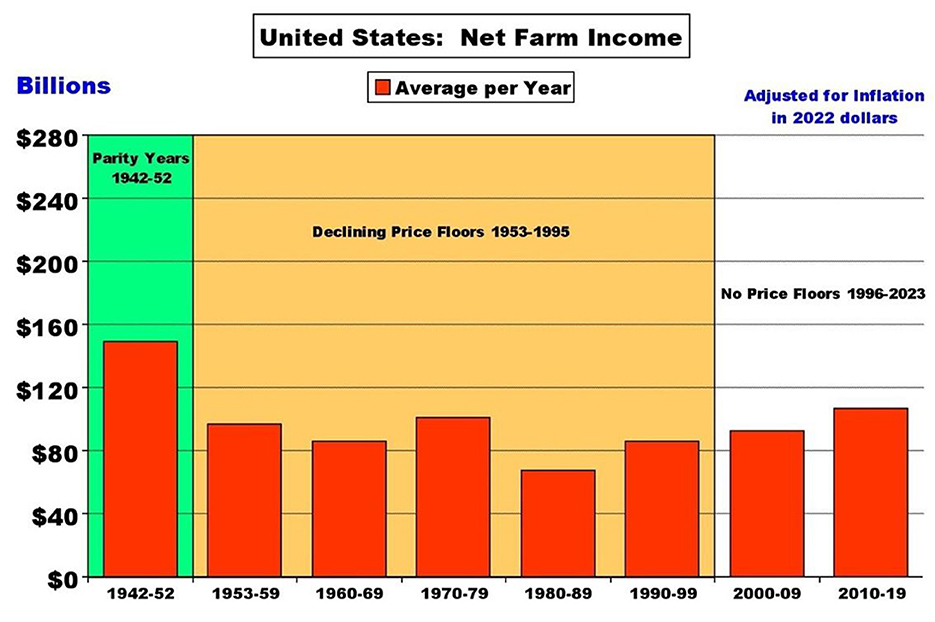

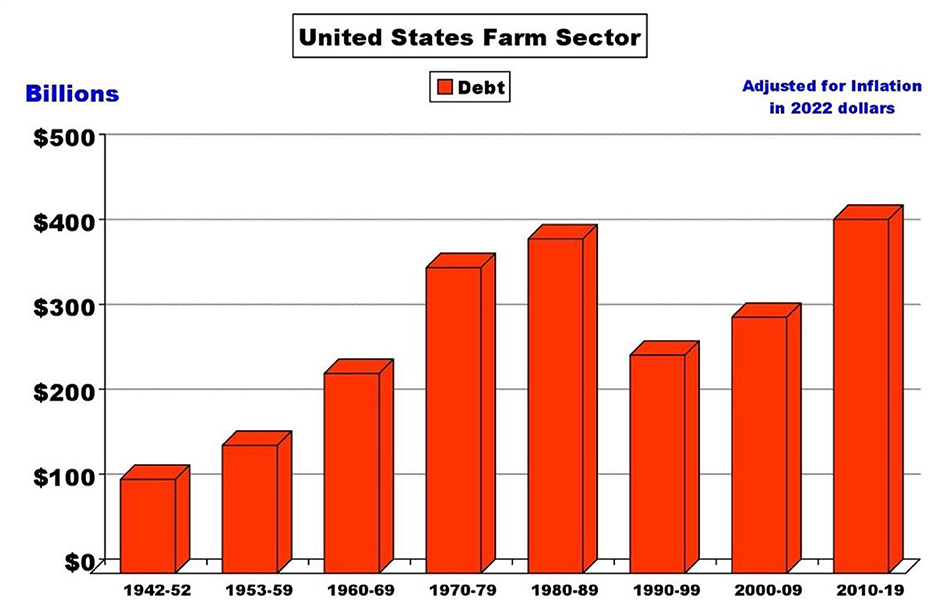

The erosion of parity resulted in decades of socioeconomic decline for US farmers and rural communities. The progress shown above by major economic indicators was quickly reversed. Farm market prices closely followed the drops in price floors (USDA-NASS, 2022). The combined market income from 8 major crops fell below full economic costs every year but one from 1981 through 2005 (USDA-ERS, 2022a “Commodity Costs”, USDA-NASS, 2022 “Historical Track Record”). Critically, although yields increased dramatically over these years, annual net farm income quickly dropped and generally remained low (Figure 2). With lower net farm income and greater debt (Figure 3), return on equity from current income quickly fell, from 22% during the parity years to just 3.7% as of 2019 (USDA-ERS, 2022c “Balance Sheet” and “Value added”). As farm prices fell, profitability rose for the agribusiness buyers of farm products, U.S. and foreign, who were buying below full costs. Return on equity for food processing companies and food chains rose to double and triple the rate for farmers (Krebs, 1992). For example, by the 1980s Ralston Purina and Kellogg's averaged 33.6% and 38.9% returns on equity, and each had five-year averages of 43% or more (Krebs, 1992). Meanwhile total return on equity for U.S. farmers fell below zero for 5 years in a row, and for the corn belt, double digits below zero for 6 years (USDA-ERS, 2022d “Farm sector financial ratios”).

Figure 2. Average net farm income throughout decline from parity. As price floors were gradually reduced, net farm income generally fell (USDA, ERS, Income and Wealth Statistics).

Figure 3. As parity was gradually eroded through agricultural policy changes, US farm sector debt rose, and currently farm sector debt is over $400 billion (USDA-ERS, Balance Sheet).

While farmers received cheap prices for feed grains, livestock and poultry CAFOs buying those grains profited, both from the ability to cheaply raise huge numbers of livestock, and from the subsequent comparatively cheap sale of that meat. Farmers raising livestock sustainably on pasture were unable to compete with CAFOs and so lost their value-added livestock. This loss led to a massive decline of farms with a diversity of sustainable livestock crops: grass pastures, hay, and oats. For example, in the five corn belt states (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and Ohio) while 61% of farms were lost between the 1950 and 2017 Censuses of Agriculture, 84% of farms with cattle were lost, 98% of hog farms, 99% of farms with dairy sales, and 97% of farms with poultry sales (USDA-NASS Census of Agriculture, 1954). With the loss of livestock diversity, crop sustainability patterns followed suit: 76% of farms with hay were lost, 95% of farms with pasture on cropland, and 99% of farms with oats (USDA-NASS Census of Agriculture, 1954), signaling broad trends of biodiversity loss and ecological destruction.

The long history of mass activism from family farmers, while oft overlooked and untold, speaks to the persistence of discontent. Importantly, this historical analysis requires layers of international contextualization, starting with how tribal and Indigenous nations were excluded from the programs, and moving on to how such federal farm policy excluded growers in the territories and neo-colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, Mariana Islands and elsewhere. This international contextualization would also situate U.S. Farm Bills and farm justice movements within Cold War geopolitics and amidst the liberatory but convoluted dynamics of decolonialization. For instance, PL-480 provided an outlet for the vast surpluses in the post-World War II excesses of production. Over time PL-480 became a powerful agro-economic tool (Ruttan, 1993; Diven, 2001; Clapp, 2012; McMichael, 2021), reaching to India and beyond, that helped to achieve U.S. foreign policy goals. U.S. wheat, corn, rice have been as critical as the military in spreading U.S. hegemony across the world (Morgan, 1979). Further research is needed to uncover deeper relationships between supply management, surplus disposal, and PL-480 food aid programs. Throughout the 1900s, farmers formed new national and state organizations and alliances (Wilson, 2016). In 1955 the National Farmers Organization (NFO) was formed, eventually forming state organizations in 48 states. During the 1960s, NFO rallies reached 10,000, then 20,000, to an overflow crowd of 34,400 farmers (Krebs, 1992; Rowell, 1993). NFO protests were often geared toward collective bargaining, fighting against withholding actions such as milk dumping. At one point, NFO mobilized a million farmers to come to meetings in 19 states within a six-month period (NFO Reporter, 1963). As the decline from parity continued, the American Agriculture Movement (AAM) rose up vigorously during the 1970s, “with some 600 offices scattered throughout the United States, and with rallies of tens of thousands of farmers, and “tractorcades,” including one in which farmers planted themselves on the National Mall in Washington D.C. for months, with tractors (De Graaf et al., 1982; Krebs, 1992). The Farmers Union (NFU) also played a major role. During the 1980s, the abovementioned groups and others formed alliances at state, national and international levels, with additional support from labor and church groups (North American Farmer, various issues). They all came together in support of proposals for restoration of parity farm programs, for example, at the United Farmer and Rancher Congress of 1986 (Naylor, 1986). The National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC) and NFU each developed proposals for restoration of price floor programs (NFFC, 2007, 2021; Schaffer et al., 2012; Wilson, 2012).

Overall, few scholars have addressed agricultural parity programs, though the topic merits substantial multidisciplinary, mixed-methods investigation, from archival history to agricultural economic statistical regression. Winders (2009) analysis focuses largely on the way different commodity associations lobbied Congress, with important historical and geographic descriptions. Yet, the claim of differences among corn, cotton, wheat, and other major commodity crop growers, based on Congressional records, conflates lobbying with what happens on the ground for farmers themselves: largely two separate realities. For example, Congress reduced core farm program benefits in every Farm Bill from the early 1950s until the programs ended in 1996 (Hansen-Kuhn, 2020), and yet those voting for those reductions referred to these Farm Bills as good for farmers. Despite geographical and agricultural differences among corn, cotton, and wheat farmers, these producers forged improbable but important coalitions throughout the twentieth century based on the shared struggle for fair farmgate prices, such as during the United Farmer and Rancher Congress in the 1980s, which united farm justice demands from more than 1,000 delegates representing all the lower 48 states (Naylor, 1986). The price issue was the top priority, affecting most other issues in major ways.

The Family Farm Movement, like any movement, was not monolithic. Indeed, what makes it historic was that such divergent constituents comprised it, following intensive and extensive outreach, pre-internet knowledge sharing, political education, pre-cell phone communications, dialogue, debate, consensus-building, community organizing, and travel—to rural places across the Midwest as well as to D.C., by tractor no less. This movement deserves its own paper, books, and documentaries, well beyond the scope of this paper, which aims merely to introduce the topic and instigate such research. Of note, Jesse Jackson and the broader Rainbow Coalition featured prominently in these farm justice movements, as did the leadership of Ralph Paige and other Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund leaders and members, who deliberately united racial justice, farm justice, labor justice, and land justice movements (Slotnik, 2018). Drawing upon her 2017 Practicum research trip to Iowa to study home archives of the family farm movement, Tracy Watson co-authored with Brad Wilson “Two hidden histories of rural racial solidarity movements” (Watson and Wilson, 2021), chronicling how Black farmers and community leaders worked with white counterparts to stop racist militias feeding off the 1980s rural farm crisis.

Farm justice movements have largely dwindled, alongside the overall percentage of the population who farms for a living. Yet, vestiges remain and are merging and growing, through such projects as Disparity to Parity. In 2019, drawing on 7 years of collaboration with National Family Farm Coalition and member and ally farm justice organizations, and in the wake of NFFC director Kathy Ozer's and Federation's director Ralph Paige's untimely deaths, Graddy-Lovelace co-initiated a public research project to archive and pool farmer knowledge on parity policies. Working with NFFC, as well as FSC/LAF, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, Food and Water Watch, Farm Aid, and others, this expanded to become Disparity to Parity (D2P) (disparitytoparity.org), a community-led action research collaboration to recenter parity and to update it for racial/gender equity and ecological resilience. Nevertheless, many food, environment, and agricultural groups do not focus on or even mention market management, yet. While advancing alternative agri-food systems remains vital, reforming—and even transforming—the dominant agricultural system remains foundational to human and planetary survival.

Parity for whom? Rethinking supply management through a racial justice lens

Between the parity years of the 1940s and the ensuing decline from parity in the following decades, the number of farm owners changed dramatically. After the increases described above, the number of farm owners dropped 26 and 20% for the 1950s and 1960s (USDA-NASS, Census of Agriculture, various years). The reversal from the parity years was more impactful for nonwhite farm owners in the South, where 37 and 48% were lost in the 1950s and 1960s. The loss of tenant farmers increased dramatically as well, with an 85% reduction between 1950 and 1990, and, unlike the parity years, these reductions did not lead to an increase in the number of owners. For nonwhite tenants in the South, 96% of those surviving to 1950 were lost by 1970. The following subsection will describe some experiences of Black and immigrant farmers throughout parity years and beyond, highlighting the need for more inclusive supply management policy, the resilience of rural communities, and the power of agrarian voices.

Internationally, the US was emerging as an agricultural technology leader. Green Revolution technology created higher surpluses in the US, causing a central contradiction in US policy: on one hand managing supply to prevent glut, on the other hand disposing of that surplus for geopolitical gain. As parity systems were active, most farmers growing parity crops received price supports. A historical overview of Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) programs examines the inequitable distribution of benefits in the U.S. South (Pennick, 2011). Non-recourse loans, price supports, grain reserves, and acreage set-asides, outlined above, were implemented throughout the region. However, these programs were tailored to white landowners and systematically excluded Black farmers (Sligh, 2021). In the face of institutional racism and subjugation by white officials, the collective mindset allowed Black families and cooperatives to strengthen rural communities and pursue land and farm-based economic development (White, 2018). However, the continuing farm justice movement in the South persists only because of the steadfast commitment of our community partners and countless others (Barnes, 1987). Cornelius Blanding, Executive Director of the Federation, argues that although the concept of fair prices is an urgent priority.

The word [parity] does not speak to the needs and lived experiences of our members. For a select few farm elders who recall the cotton, peanut, or tobacco quota programs from a generation or two ago, like Mr. Ben Burkett, the concept of price-floors and supply management make sense. But for middle-age or younger farmers, the concept is historic and improbable. Moreover, for those struggling to hold on to land, or who have suffered the trauma of racist dispossession, “parity” seems too abstract and removed from the urgency at hand. They are ready, however, to resume prior activism around fair prices—alongside the struggle against broader racisms in agriculture and land policies (Blanding, 2020).

Jerry Pennick chronicles the racism of this injunction amidst the long history of USDA anti-Blackness, from slavery and sharecropping to Jim Crow racial terrorism and coordinated land dispossession (Banks, 1986): “let us put to rest the argument that the Black farmers' [Pigford] discrimination settlement against the USDA should be enough. That argument too is steeped in racism. The fact is that, even though the USDA admitted that it actually did discriminate based on race, the Black farmers who could individually prove that they experienced race-based discrimination, on average received < $50K from the settlement—or even enough to buy a good tractor and no Black farmer was made whole” (Grant et al., 2012; Tyler and Moore, 2013; Pennick, 2021 on Pigford civil rights class action lawsuit against the USDA). This trend continued into 2022, when the Inflation Reduction Act included $2.2B to farmers and ranchers who have faced “discrimination” and $3.1B for debt relief to “disadvantaged” growers; but this casts too broad a net to ensure restitution for Black farmers, who have, as documented extensively, faced acutest bias (Pennick, 2021; Rappeport, 2022).

Ben Burkett remembers growing up during parity years and farming with his father on their land in Petal, Mississippi. He explains that cotton allotments regulated how much each farmer could plant, which helped manage supply and reduce overproduction. However, the system favored larger landowners, most of which were white (Burkett, 2021). According to census data from the USDA, Black farmers have for the last few decades operated about one third of the national average of acres farmed, and this number may have declined since the most recent 2017 census, given rising farm debt and land loss for African Americans (Economic Research Service, 1986 and National Agriculture Statistics Service 2019). Despite the racist implementation of allotment and other supply management programs, Black farmers did benefit from solid price floors. For small and medium-sized farmers, a guaranteed fair price might determine whether they can cover their costs of production. With the erasure of supply coordination, farmers are unable to predict or prepare for rock-bottom farmgate prices.

While acknowledging the inequity ingrained in New Deal AAA programs, Pennick and Gray (2006) also conducted interviews with Black farmers about their experience with cotton programs in post-parity years (in the early 2000s). The cotton program discussed in the text involved counter-cyclical payments (often called subsidies) (USDA, Farm Service Agency, 2003), which supplement farmer income given low global cotton prices. Black farmers in the program acknowledged their dependence on the payments to continue farming, though they still struggled to cover the rising costs of production (Pennick and Gray, 2006). Respondents also revealed that they consistently received less money than neighboring white farmers. One participant stated, “The government should investigate those agencies on how the price support programs are determined. Whereas, whites get a high base on land, when blacks lease the same land their payments are lower” (Pennick and Gray, 2006). Finally, when asked about the impact of cotton prices on the producer experience, “in virtually every instance they said that a fair price would solve the problem and the cotton subsidies, therefore, would not be necessary (Pennick and Gray, 2006). To conflate counter-cyclical payments as in this study with price supports is incorrect: subsidies reinforce farmer vulnerability and dependence, while well-designed, just, and equitable supply management policy guarantees a fair price and a stable income.

The Federation, along with ally organizations and coalitions across the US and around the world, works to ensure secure markets and fair prices for their products to revitalize rural communities. Blanding explains that cooperatives allow small-scale farmers to aggregate not only tools and resources but production: “farmers with limited resources. Can buy collectively and gain economies of scale, then lower the costs of production. And the more you can lower the cost of production, the easier it becomes to get to that fair price” (Blanding, 2020). The Federation brings together cooperative networks and state cooperative associations to broaden the impact of aggregation and knowledge-sharing. Additionally, alternative systems are bolstered by activities such as institutional purchasing from facilities like schools and hospitals, which secure fair prices and reliable demand in the absence of mandated price floors. The work of Black farming cooperatives in the South does not stand alone. The following case shares an ethos of survival within an exclusionary agro-industrial system and offers crucial lessons in the power of practitioner-led solutions to structural problems.

Given the volatility of largescale policy initiatives within shifting administrations, changes in farm policy tend to fall short of systemic reevaluation. Fostering a cooperative mindset as a core principle of alternative systems facilitates locally controlled supply management as a tool of survival. Coalition-building among farmers is offering an alternative to the exploitative culture of competition and racism while reimagining the country's traditional agrarianism. We see this principle come to life when factoring in the experiences of Rural Coalition's member organization World Farmers. Based in rural Massachusetts, their mission is to honor the dignity and passion of immigrant and refugee farmers to grow food vital to their culture and communities, and to provide support to each farmer in their endeavors to do so (Krikorian et al., 2022). Their programming first began because of the bravery of a refugee farmer in asking for land when her family and community had a great need, and the kindness of an immigrant farmer who offered land because they knew what it was like to lack (Freedoms Way 2020). That land became known as Flats Mentor Farm (Cox and Krikorian, 2022). Now, World Farmers supports farmers along every step of the learning process, facilitating mentorship spaces across farmers and cultures, cultivating a shared space among individuals of like-backgrounds so that farmers can learn together and from each other, and can be inspired by those who have come before them. The Flats Mentor Farm land site serves as an example of this, where seeds are shared across cultures, produce grown without boundaries, and families made from differing mother tongues and traditions.

Unfortunately, organizations like Rural Coalition members groups and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, who aim to support small Black and immigrant farmers at the community level, work within a vacuum of established supports for growers of color. With a majority of dominant food system tailored to large corporate interests, rural communities continue to band together around what could be seen as basic principles of parity through supply coordination, collective bargaining, and market control on small levels, even when national policies disempower and discourage them to continue farming (Ray et al., 2003; White, 2018). With USDA's goals focused on all-out production for the benefit of agribusiness input sellers and grocery buyers, federal farm support remains inadequate and counterproductive. These programs are typically underfunded, understaffed, unequipped and often misguided. Thus, communities that should benefit from real agrarian policies must rely on each other for support. Especially as history has brutally misrepresented and excluded immigrant farmers and farmers of color, a growing distrust in the institutions makes learning from grassroots practitioners even more crucial.

On a macro-level, learning from immigrant and Black farmers is crucial to redefining our understanding of agricultural policy here in the United States. The United States global food system is informed, upheld, and led by the work of BIPOC and immigrant farmers who have contributed to a system that does not value, acknowledge, or support them often enough. The use of confusing, roundabout diction and policy is intentional to keep the white-focused status quo (Conrad, 2020). However, as discussed throughout this article, we must center diverse agrarian voices, as they have continuously paved the way for revolution and agrarian viability throughout a (neo)colonial oppressive state (White, 2018). In the work of updating parity programs and expanding them explicitly for racial justice, this would also require centering Black leadership in agricultural policies of supply management, quota governance, farmgate price calculations, outreach to farmers, program assessment and evaluation, and which crops to prioritize.

This direction would also require an anti-racist international agricultural policy orientation and commitment—moving from racialized feed-the-world geopolitics or a competitive farmer-vs-farmer zero-sum game paradigm to a transnational solidarity with farmers around the world.

India farmer uprising

The historical import of the India Farmer Uprising eluded U.S. journalism, scholarship, and even food and agricultural civil society, for many reasons: from media urban bias to a misunderstanding of the crux role of farmgate prices, to, we argue, a geopolitical racial bias. India has twice the population of the continent of Europe, and over five times the linguistic and (agri)cultural diversity. If the same numbers of people were occupying the capital city in Europe for over a year, it would have dominated the news. Accordingly, we position the Indian Farmers Movement (called a Revolution on the ground in India) as of world-historical importance, both for the scale and diversity of its mobilization and due to its content: the universal need for fair farmgate price floors so farmers can live and grow on the land.

After years of agrarian distress, falling incomes, growing rural debt, and landlessness that had taken the lives of over 300,000 farmers (Thomas and De Tavernier, 2017) farmers throughout India were hit by a global pandemic and subsequently, large-scale lockdowns. The restrictions crippled a majority of the agricultural sector as many small to medium sized farmers lost access to crucial food markets. Subsequently, three farm laws were introduced by the Indian government in 2020 during the lockdowns to forcefully open the previously protected agriculture sector to privatization and corporate takeover, referred to by the government as “agricultural marketing reforms.” These laws aimed to end stocking limits for agro-processors, allowed corporations to create tax-free market-yards, and gave legal validity to corporate contract farming. The claim made by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its Prime Minister Narendra Modi was that these reforms would increase farmer incomes, broaden their marketing choices, spur technological investment that improved farm productivity, and attract foreign direct investments to Indian agriculture (Agarwal, 2020; Varghese, 2020, 2021).

However, farmer unions in Punjab and Haryana–the two main breadbasket regions of the country – expressed fears that the laws threaten to dismantle the existing minimum support price (MSP) system that provides farmers with price floors for twenty-three crops. Their fears were justified, as the government had a detailed plan to create tax-free corporate market-yards to procure grains while the government owned market yards–also known as mandis–were taxed. This naturally favored corporate buyers who could now procure the grain below market price without taxation. What concerned the farmers was the fact that similar reforms were introduced in the Indian state of Bihar in 2006 and had failed miserably (Januzzi, 2011). Instead of investment, corporations and big traders used the laws to squeeze farmers, significantly reducing the incomes of farmers well below the state average. Meanwhile Bihari farmers' grain, wheat, and rice were being carted to Punjab and Haryana by traders and corporations to be sold in government mandis (market-yards) at minimum support price (MSP) rates.

Many argued that dampening the influence of the MSP over the market would allow for increased corporate expansion through market liberalization–which has been creeping into India since the early 1990s through neoliberal policies pushed through the implementation of the New Economic Policy in 1991 (Martin, 2017).

Beginning in November 2020, over 250 million workers across 10 central trade unions joined farmers in protesting the anti-farm laws. Thousands of Indian farmers made the difficult, yet brave decision to leave behind their precious land and march to Delhi's borders to voice their concerns to the central government. It was an arduous journey, as many farmers had to endure water cannons, baton charges and roadblocks (Singh, 2021). Despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, however, most farmers managed to not only set up camp near Delhi, but established fully functioning communities within them (Sud, 2021). Through collaborative efforts, the encampments transformed into mini-temporary cities that were supplied with food, milk, water, and other necessities by the neighboring villages. The various camps had also established regular supply lines for villages deep in the hinterlands of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh.

Meanwhile the police and paramilitary guarding the roads were supplied with assault rifles, tear-gas, and surveillance drones, to keep the farmers in-check. At various times during the year, the government utilized disinformation campaigns to smear the movement—labeling farmers as insurgents and terrorists, slapping fake cases on protesters and using police intimidation to break up the encampments. Farmers persisted, and eventually formed the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM), a coalition made up of over 500 organizations including farmers unions and workers unions across a spectrum of differing ideologies. After almost a year and a half of struggle, the movement broke ground as the central government announced the repeal of the controversial laws.

Although there were celebrations to be had, farmers also understood that the repeal of the three laws was incomplete without the implementation of a parity price system for crops. Currently, the movement is demanding that the government enforce the MSP for 23 crops as a legal right for farmers (Agarwal, 2022). This would mean that no buyer, whether government or private, would be allowed to buy below the regulated sale price, thereby ensuring that the MSP would then become the minimum, not the maximum support price. Increasingly, more farmers are resonating with the message of parity amid falling incomes, rising debt, and a price-cost squeeze that has pushed the small farmers toward destitution.

The success of the Indian Farmers' Uprising has become a convergence point for agro-justice, proving to be a pivotal point in the fight for parity in India. Importantly, the movement's success sets a precedent for international agricultural policy's future. Amid a broader neoliberal push for the removal of key price supports in the Global South, the victory of the Indian farmers and their push for a parity price system provides a strong foundation for the reinvigoration of farm justice movements globally (Soni, 2022).

Analysis of parity amnesia: Subsidy conflations and distractions

For whom and in what contexts are parity policies illogical—not just improbable, but not even worth struggling for? When, where, and by whom have fair farmgate prices been a central rallying cry? When, where, and by whom have they been considered irrelevant? This paper makes room for these questions, so instrumental to agricultural governance and agri-food systems, and yet so rarely asked.

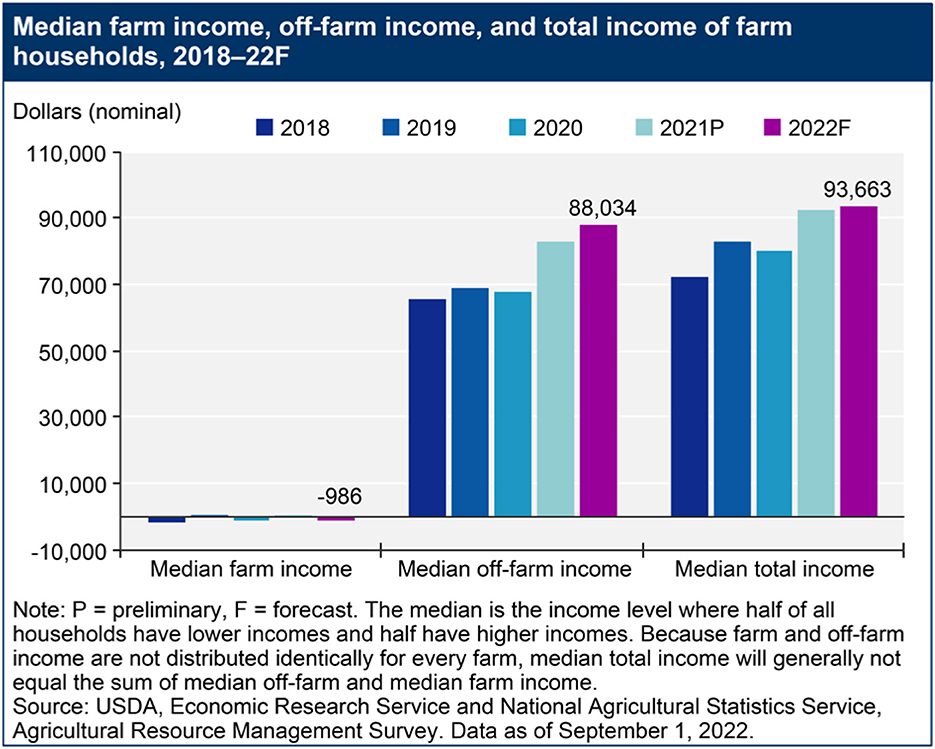

The allegedly free market depends upon governmental deregulation of industry, regulation of supports, and multiple enabling state-infrastructures that work to subsidize the profits and stability of industry, particularly in the agri-food sector. The inquiries guiding this research reveal an overall erasure of the very histories, movements and programs falling under the umbrella of parity and supply management. Most of those who have survived the gauntlet of chronic agrarian crisis and continue to farm earn their livelihood not from farming but from off-farm income (Figure 4) and/or assets of land ownership—and from payments from the government, deemed “subsidies,” such as Direct Payments, Countercyclical Payments, or Trade Payments. Confusingly, the term used to describe these checks from USDA, “subsidies,” has been conflated with price floor, supply management, and parity programs, in the absence of which such payments are needed. There is understandable social and political frustration that these checks-from-the-government flow to the richest, whitest, most landed farm owners. Yet, this frustration has further compounded the misrepresentations of this slippery term, “subsidy.”

Figure 4. Farm households typically receive income from both farm and off-farm sources. Median farm income earned by farm households is estimated to increase in 2021 to $210 from - $1,198 in 2020, and then forecast to decline to -$986 in 2022. Many farm households primarily rely on off-farm income: median off-farm income in 2021 is estimated at $82,809, an increase of 22 percent from $67,873 in 2020, and to continue increasing by 6.3 percent to $88,034 in 2022. The increase in 2021 was mainly due to higher earned income—income from wages, salary, and nonfarm businesses—which rose 54 percent from $32,428 in 2020 to $50,000 in 2021. Unearned income—income from interest, investments, pension and retirement accounts, unemployment compensation and other public transfers—also increased by 7.2% between 2020 and 2021. Since farm and off-farm income are not distributed identically for every farm, median total income will generally not equal the sum of median off-farm and median farm income (USDA ERS 2022).

“Subsidies” have become the nemesis of agri-food policy analysts, from civil society, from climate activists to public health officials, from the WTO itself, to biodiversity accords seeking to just switch “environmentally harmful subsidies” (complete with their own acronym EHS) to environmentally helpful subsidies. As co-authors in this paper have researched, explained (Naylor P. E., 2017; Wilson, 2018), and experienced, this conflation leads to a large-scale distraction from the reality that systemic commodity crop overproduction itself subsidizes the agro-corporate buyers, who profit mightily off the falsely cheap glut, be it feed for industrial livestock or flex crops for ethanol production or other industrial agri-food stuffs (palm oil, soy, etc.). Here the broader trend of capitalism unfettered to cheapen commodified goods, products, services, labor (Patel and Moore, 2018) applies directly to agricultural farmgate prices. This phenomenon has had cascading detrimental effects, particularly for farmers of color, who face this chronic agrarian crisis atop viciousness of systemic racism—particularly anti-Black discrimination in USDA lending, programs, and overall agri-food sector. Black-owned farmland plummeted in the second half of the twenteeth century, even faster than it did for mid-size white farmers. Concurrently, farms grew in size and became more “specialized,” with larger and more monocultural fields of one crop. The number of farms with livestock and poultry fell faster than the loss of farmers themselves, even as number and scale of CAFOs grows exponentially with their feed grain input so cheap and plentiful.