- Landscape Conservation and Community Participation Laboratory (@ScapesLab), College of Environmental Studies and Oceanography, National Dong Hwa University, Shoufeng Township, Taiwan

This study addresses knowledge gaps in long-term integrated landscape and seascape approaches (ILSA) by examining the facilitation of future-scaping—a participatory method for co-visioning futures and setting actionable goals—in the Xinshe “Forest–River–Farmlands–Ocean” Eco-Agriculture Initiative in eastern coastal Taiwan. Drawing on facilitator perspectives since 2016, we show how future-scaping tools helped the Dipit and pateRungan Indigenous tribes, government agencies, and the local school articulate 2026 and 2050 visions and translate them into 19 priority objectives. The process revealed shared aspirations for ecological integrity, sustainable agriculture, cultural revival, youth return, and equitable governance; fostered inclusive knowledge weaving; and enabled adaptive shifts in the initiative’s concluding phase. Lessons learned are discussed through the Problems, People, and Process dimensions of the Xinshe ILSA’s 5P + S model, emphasizing structured flexibility to bridge aspiration–implementation gaps, sustained inclusivity across knowledge systems, and facilitation as a key boundary function. As a model for rural transformation, the Xinshe ILSA affirms co-produced, iterative approaches as vital for navigating nexus challenges and advancing toward living in harmony with nature.

1 Introduction

In recent years, growing recognition of the complexity of social-ecological systems has underscored the limitations of siloed approaches to sustainability (Locatelli et al., 2025; Suit et al., 2021). This recognition reinforces the need for integrated, inclusive, and iterative strategies that can address dynamic realities across scales and contexts. At the same time, it highlights the urgency of collective action and the importance of transformative shifts in how humanity relates both to nature and to one another (O’Brien, 2021).

Rural landscapes and seascapes, often marginalized in mainstream development discourse, are uniquely positioned to inform such transformation. These areas hold deep reservoirs of ecological knowledge (including Indigenous and local knowledge, ILK), cultural heritage, and governance traditions, and they offer cultural ecosystem services (Plieninger et al., 2015; Karim et al., 2024). Integrated landscape and seascape approaches (ILSA) are increasingly recognized as promising frameworks for advancing these transformations (Karim and Lee, 2024a; Nishi and Yamazaki, 2020; Pedroza-Arceo et al., 2022; Zafra-Calvo et al., 2025). They are place-sensitive, people-centered, and process-oriented, enabling local action with real impact and scalable potential (Karim and Lee, 2024b; Waeber et al., 2023). When well-facilitated, ILSA can foster meaningful partnerships across stakeholder groups and support a shared journey toward long-term sustainability.

A key element gaining momentum within these approaches is the recognition of ILK as both a foundation for envisioning future scenarios and a guide for action (Carvalho-Ribeiro et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2023; Oteros-Rozas et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2020; Norström et al., 2020). The IPBES Indigenous and local knowledge dialogue workshop on Scenarios of the future (23–26 May 2025, Subic Bay, the Philippines), for example, emphasized the importance community-based perspectives and co-creation approaches toward future scenarios (IPBES, 2025). However, despite this growing attention, there remains a persistent gap in the availability of well-documented, long-term ILSA case studies that can serve as concrete learning examples—especially those that have progressed beyond the early phases of implementation (Karim and Lee, 2024a; Karim and Lee, 2024b; Pedroza-Arceo et al., 2022). Equally underexplored is the role of facilitators (also referred to as boundary brokers or bridging stakeholders) in operationalizing ILSA, particularly in guiding multiple stakeholders through the final stages of such initiatives (Waeber et al., 2023; Lee and Karimova, 2021).

The Xinshe “Forest–River–Farmlands–Ocean” Eco-Agriculture Initiative (hereafter, the Xinshe Initiative) is widely recognized as a leading example of a rural ILSA in Taiwan and is among the most extensively documented. Xinshe is a socio-ecological production landscape and seascape (SEPLS) located in Fengbin Township, Hualien County. The Xinshe ILSA, established in 2016 for a 10-year period to support social-ecological revitalisation, has been facilitated by our team since its inception. Our earlier work examined its foundational phases, including planning and trust-building (Lee et al., 2019), resilience assessment for monitoring and learning (Lee et al., 2020; Karimova et al., 2022; Karimova and Lee, 2023), and adaptive co-management in the short-term phase (2016–2020) (Karimova and Lee, 2022). This paper focuses on future-scaping – a participatory approach to co-visioning futures and co-setting goals for the mid-term phase of the Xinshe ILSA. Drawing on our embedded facilitator perspectives, we discuss how future-scaping tools enabled diverse stakeholders to articulate 2026 (after the end of the Xinshe ILSA) and 2050 (living in harmony with nature) visions and translate them into actionable, locally grounded priorities.

Our inquiry builds on the 5P + S elements of ILSA—Place, People, Problems, Process, Progress, and Scaling (Karimova and Lee, 2024a)—with discussion organized around its Problems, People, and Process dimensions. First, we examine how future-scaping tools helped uncover and structure the mid- and long-term visions of the Dipit and pateRungan tribes, shaping a pathway from collective dreams to concrete priority tasks (Problems). Second, we explore how the process fostered inclusive and just participation of all relevant stakeholders—including the tribes, four government agencies, and the Xinshe Primary School—and what this inclusivity meant for knowledge co-production and weaving (People). Third, we analyze how the facilitation tools contributed to the adaptive and iterative character of the Xinshe ILSA, enabling a strategic “gear shift” into the concluding phase of the initiative (Process). The dimensions of Place, Progress, and Scaling are woven throughout.

Through this empirical case study research, we hope to offer valuable lessons for practitioners, policymakers, and scholars seeking to deepen their understanding of long-term ILSA implementation, with a focus on the facilitation processes that make these approaches both resilient and transformative.

2 Methods

2.1 Case study area: the 5P + S elements of the Xinshe integrated landscape-seascape approach

2.1.1 Place

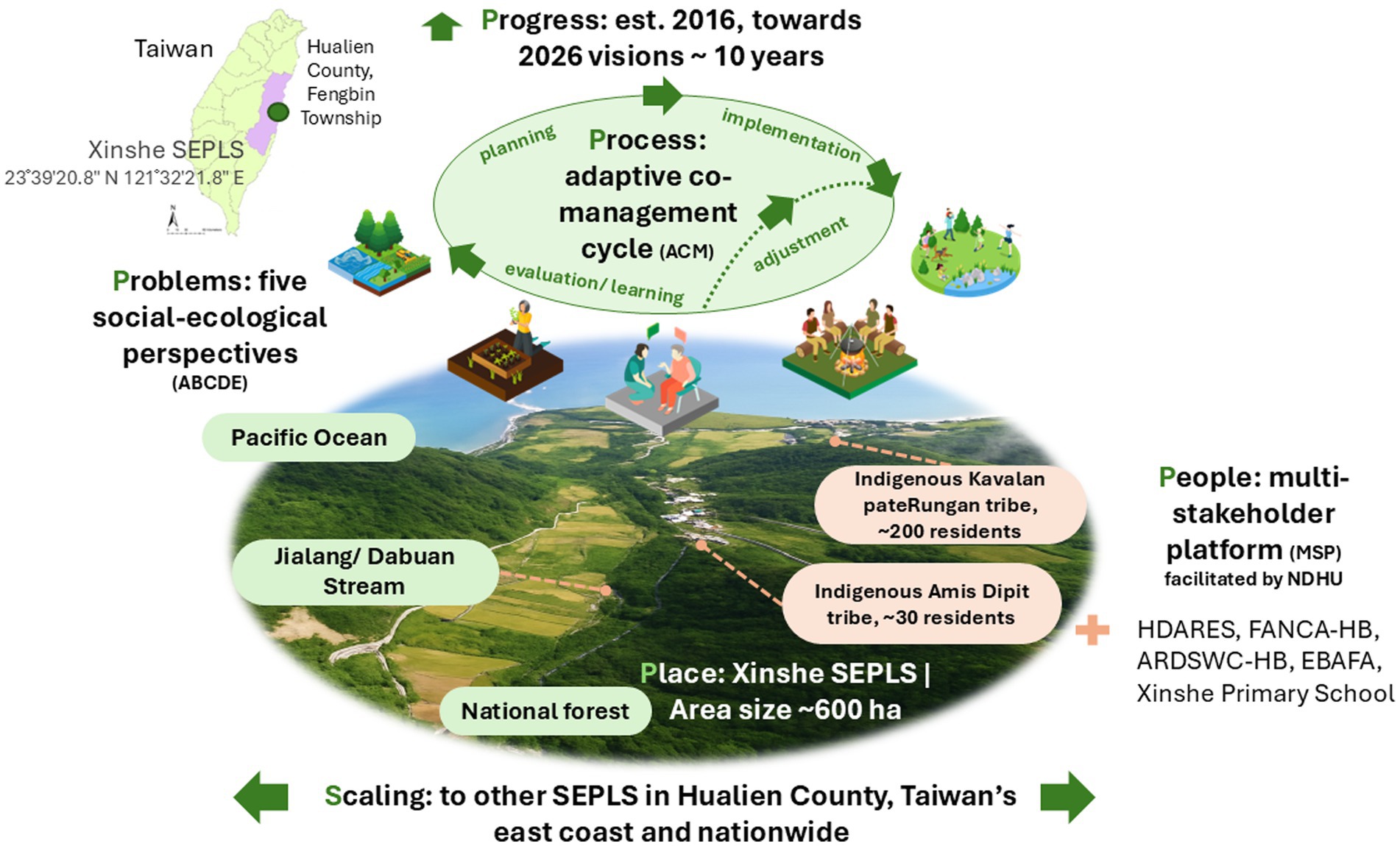

The Xinshe SEPLS spans a 600-hectare watershed of the Jialang/Dabuan River,1 forming a ridge-to-reef continuum that extends from the forested headwaters of the Coastal Mountain Range, through farmlands, to the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1). It encompasses the traditional territories of the Indigenous Amis Dipit (about 30 residents) and Kavalan pateRungan (about 200 residents) tribes. Its interconnected forest–river–farmland–ocean habitats provide essential ecosystem services and functions including freshwater, food, shelter, and climate regulation. Land and sea use practices are grounded in ILK, seasonal rituals, and cultural heritage, encompassing farming, gardening, wild plant foraging, agroforestry, hunting, fishing, handicrafts, and culinary traditions.

Figure 1. The 5P + S elements of the Xinshe integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA). SEPLS, socio-ecological production landscape-seascape; NDHU, National Dong Hwa University; HDARES, Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station; FANCA-HB, Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency- Hualien Branch; ARDSWC-HB, Agency of Rural Development and Soil and Water Conservation- Hualien Branch; EBAFA, Eastern Branch of the Agriculture and Food Agency. The Xinshe SEPLS photo credit to: Vision Way Communication Ltd.

2.1.2 Problems

The mid-term action plan for the Xinshe ILSA is conceptually guided by the five interconnected social-ecological perspectives of the Satoyama Initiative: (A) ecosystem health and connectivity, (B) sustainable use of natural resources, (C) ILK and modern science, (D) collaborative governance, and (E) sustainable local livelihoods and wellbeing. Each perspective consists of two priority themes (a total of 10) focused on “River,” “Ocean,” “Eco-agriculture,” “Native species,” “ILK documentation and transfer,” “Return of migrant youth,” “Social capital,” “multi-stakeholder platform,” “Biodiversity-based income,” and “Safety and health”.

2.1.3 People

Governance is anchored in a multi-stakeholder platform (MSP) that ensures inclusive and equitable decision-making. Sectoral composition of the core members reflects thematic perspectives of the action plan. It includes the two Indigenous tribes, four government agencies – Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station (HDARES, agricultural production), the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency- Hualien Branch (FANCA-HB, biodiversity conservation), Agency of Rural Development and Soil and Water Conservation- Hualien Branch (ARDSWC-HB, rural livelihoods and disaster risk reduction), and the Eastern Branch of the Agriculture and Food Agency (EBAFA, marketing), Xinshe Primary School (culture and ILK documentation and transfer), and National Dong Hwa University (NDHU, our team as a facilitator). Other partners get engaged on an ad-hoc basis. Without dedicated external funding, the MSP relies on coordinated government projects for financial, technical and institutional support.

2.1.4 Process

Operationalisation of the Xinshe ILSA in the short-term (October 2016–December 2020) and ongoing mid-term (January 2021–December 2026) phases follows a classic adaptive co-management (ACM) cycle of planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation, learning, and adjustment. Community-based resilience assessment workshops (RAWs) served as key tools for issue identification, monitoring, and adjustment in 2017–2018 and 2020, with a third round planned for the end of 2025.

2.1.5 Progress

The Xinshe ILSA aims to achieve local visions for socio-ecological well-being within its 10-year span (October 2016–December 2026), allowing time for Dipit and pateRungan elders to witness tangible revitalisation and for local youth to return and take up long-term management of the Xinshe SEPLS.

2.1.6 Scaling

Beyond its local context, the Xinshe ILSA shares experiences and lessons learned—including use of facilitation tools like RAWs—through national platforms such as the Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative and the Community Forestry Network. It also informs biodiversity-inclusive spatial planning under the Taiwan Ecological Network, serving as a model for other SEPLS in Taiwan (Karim and Lee, 2025).

2.2 The future-scaping facilitation tools for the Xinshe ILSA

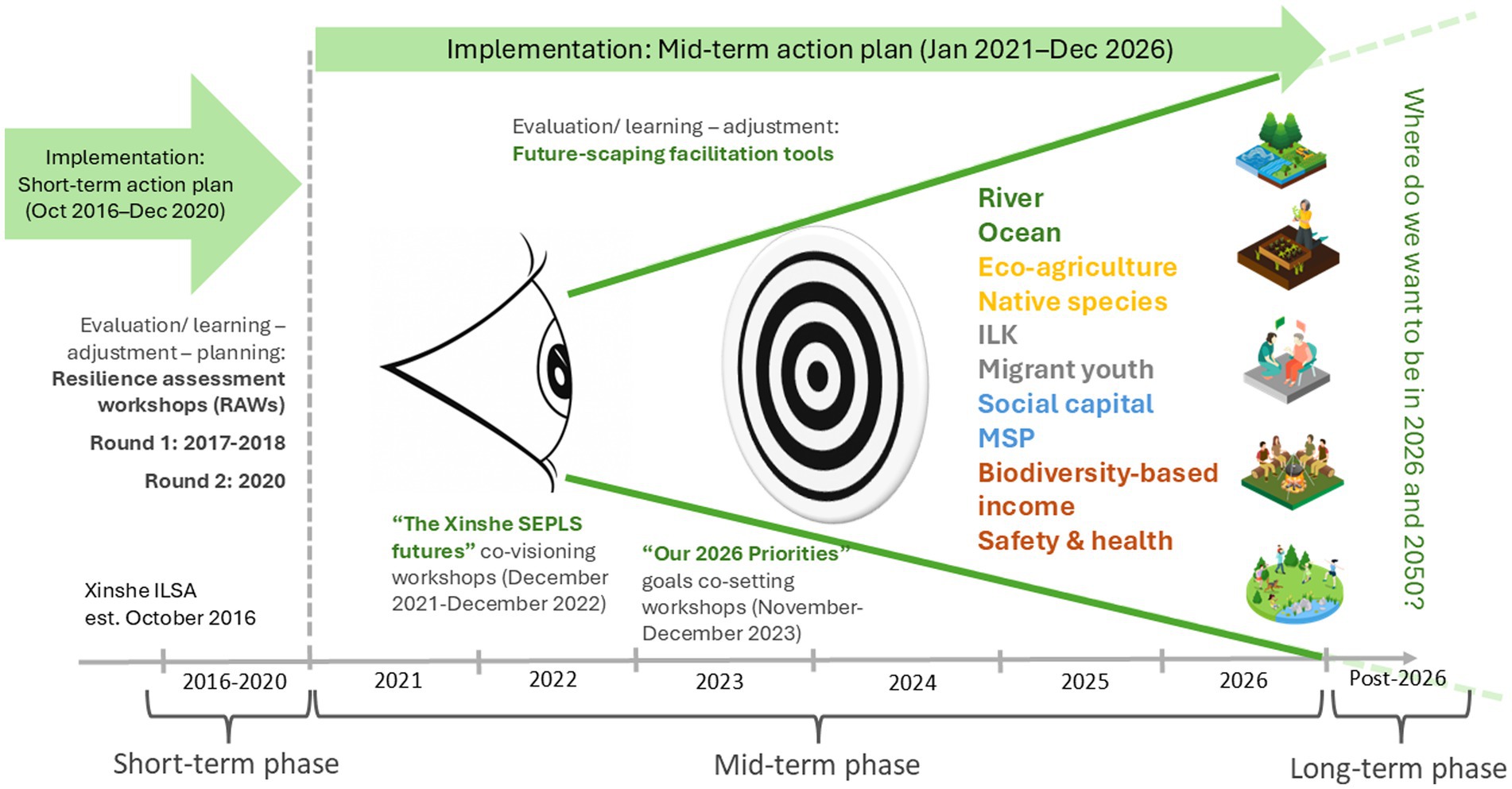

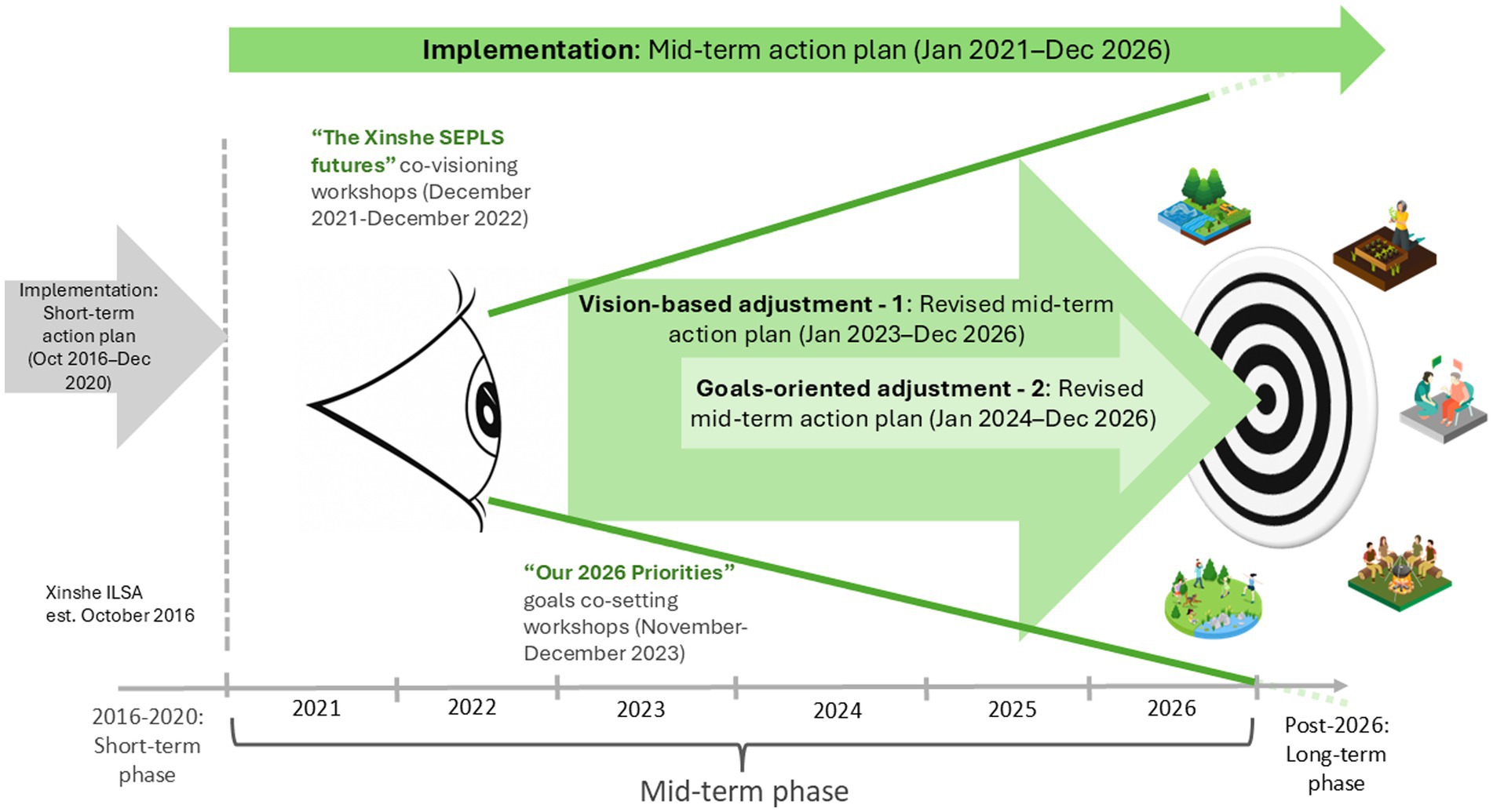

The future-scaping facilitation tools comprised a structured sequence of community-based workshops and multi-stakeholder dialoges. Figure 2 illustrates their positioning within the adaptive co-management cycle of the Xinshe ILSA, in relation to the two rounds of RAWs (2017–2018 and 2020) and the mid-term action plan. A qualitative mixed-methods approach was employed for subsequent data collection and analysis, as detailed in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2.

Figure 2. Positioning of the future-scaping facilitation tools within the timeline of adaptive co-management (ACM) process for the Xinshe integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA).

2.2.1 Data collection

From December 2021 to December 2022, “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” co-visioning workshops engaged the Dipit and pateRungan tribes in separately facilitated sessions (three workshops per tribe, two and a half hours each) followed by a joint workshop and a (MSP) meeting in November–December 2022 (Table 1). Sessions posed the guiding question, “Where do we want to be?” and explored two temporal horizons: 2050 visions structured around five perspectives (ABCDE) and 2026 visions organized under 10 thematic priorities (Figure 2). Facilitation was carried out by the authors, using printed Chinese-language versions of the Figure 2 and the action plan as workshop materials. Participants were drawn primarily from regular MSP members, representing diversity of age, gender, and length of residence in the Xinshe SEPLS: 12 participants from the Dipit tribe and 13 participants from the pateRungan tribe. Contributions from both youth and elders ensured intergenerational perspectives. Outcomes from this process informed the first vision-based adjustment of the mid-term action plan (January 2023–December 2026).

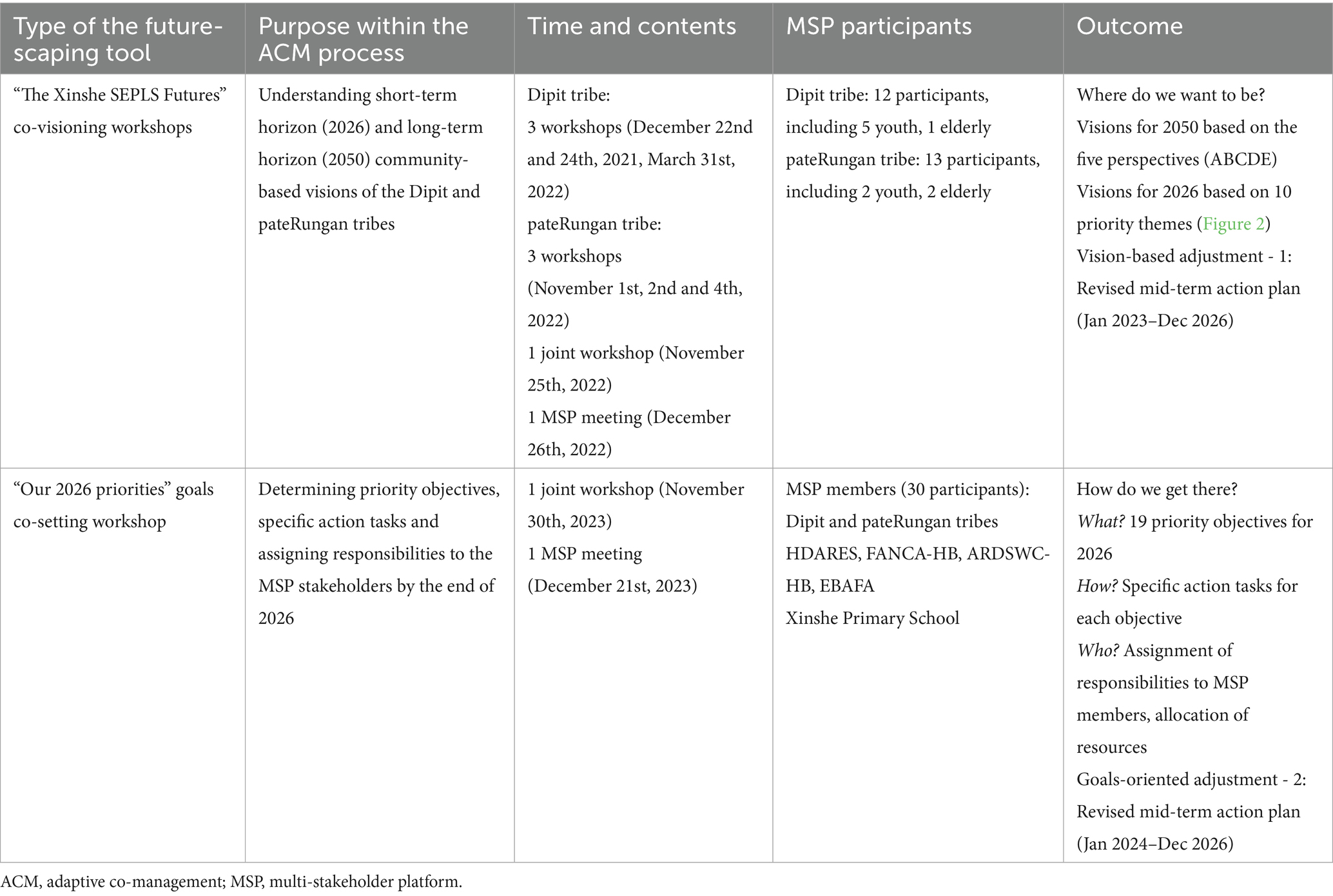

Table 1. The future-scaping facilitation tools for the Xinshe integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA) (December 2021–December 2022; November–December 2023).

The “Our 2026 Priorities” goals co-setting process shifted the focus from envisioning to implementation by asking “How do we get there?” It consisted of one five-hour workshop facilitated by the authors (November 2023), followed by a MSP meeting (December 2023). Workshop materials included a summary report of the 2050 and 2026 community-based visions and the mid-term action plan. The workshop was attended by MSP members (30 participants), including the Dipit and pateRungan tribes, HDARES, FANCA-HB, ARDSWC-HB, EBAFA, and Xinshe Primary School. This process translated visions into 19 priority objectives for 2026 and informed the second goal-oriented adjustment of the mid-term action plan (January 2024–December 2026).

2.2.2 Data analysis and research limitations

Data generated from the workshops and MSP meetings comprised facilitation notes, participant statements, audio recordings, and post-session summary reports. These qualitative materials were organized chronologically and thematically in accordance with the objectives of each future-scaping facilitation tool (“The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” and “Our 2026 Priorities”). Analysis employed a qualitative mixed-methods approach: workshop outputs were coded to identify recurring themes, and emerging priorities, with consideration of both convergent and divergent perspectives of the two tribes and their implications for the mid-term action plan. Triangulation was undertaken by cross-referencing workshop records with stakeholder feedback, official planning documents, and peer-to-peer triangulation within the facilitation team, thereby ensuring that findings were not derived from a single source or perspective.

We acknowledge several limitations of this research. As both facilitators and researchers of the Xinshe ILSA, our dual roles may have influenced the perspectives presented in this paper. To mitigate potential bias, we grounded the analysis in systematically documented processes, applied the triangulation techniques described above, and situated our reflections in relation to published evidence. In addition, the Xinshe SEPLS represents a small community with highly context-specific dynamics, which may limit the generalisability of findings beyond comparable social-ecological settings. Nevertheless, the lessons learned provide valuable guidance and contextually adaptable support for other SEPLS.

3 Results

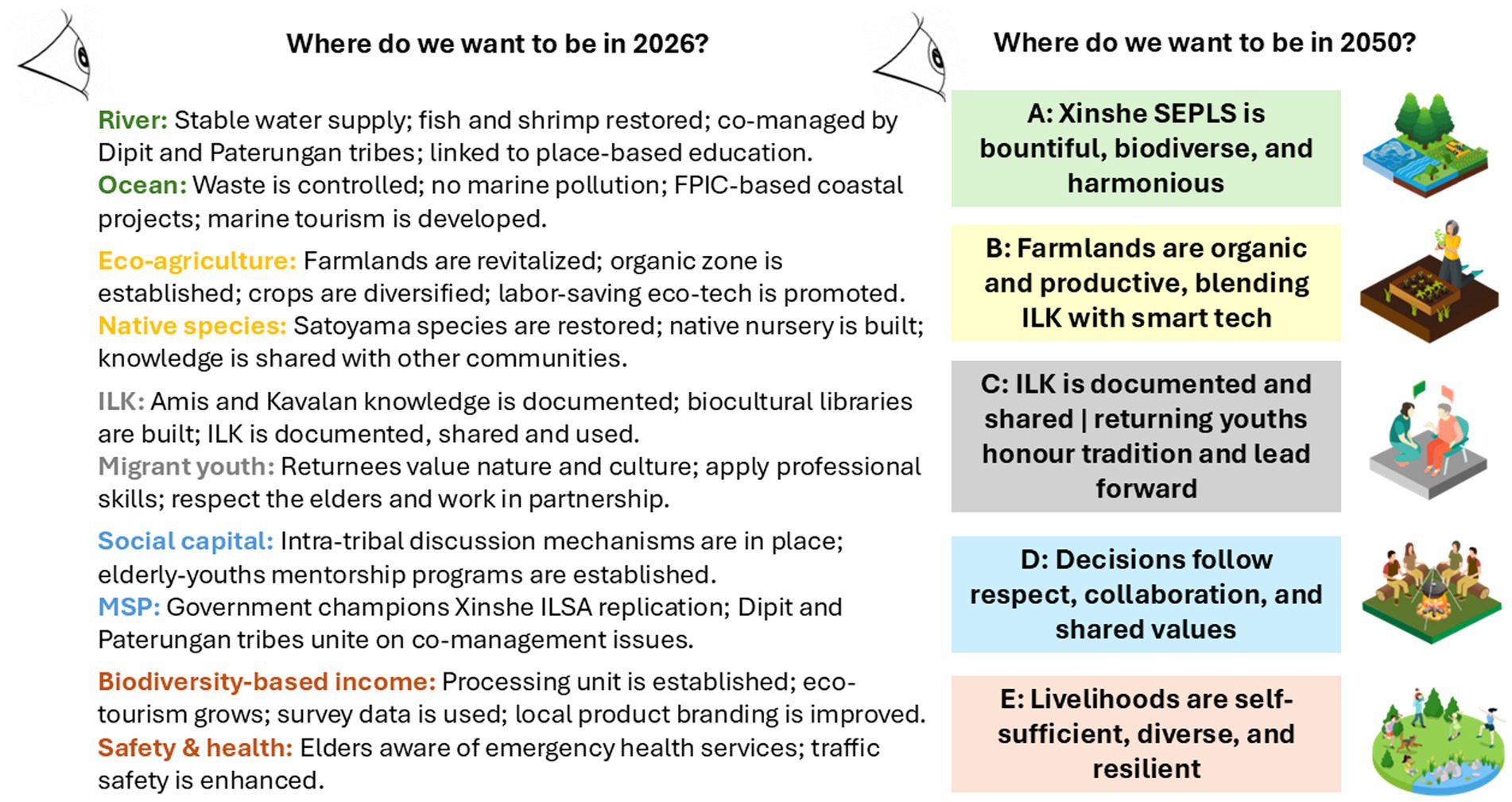

3.1 Where do we want to be?

We present results from the “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” co-visioning workshops (December 2021–November 2022), which outlined the Dipit and pateRungan tribes’ shared and distinct visions for 2050 (Section 3.1.1) and 2026 (Section 3.1.2). A full summary is provided in Supplementary material 1, with a short version in Figure 3. We intentionally use past tense to frame these visions as already achieved—by 2026 (the end of the Xinshe ILSA) or by 2050 (the global goal of living in harmony with nature). Five core aspirations unite both tribes: ecological integrity and ridge-to-reef connectivity; sustainable agriculture combining ILK and eco-technologies; revival of species and cultural traditions; youth return and intergenerational collaboration; and equitable governance (Figure 3). Differences lie in emphasis: Dipit grounds its vision in cultural memory and freshwater systems, while pateRungan prioritizes marine restoration, coastal governance, and place-based education.

Figure 3. Where do we want to be in 2050 and 2026? Community-based visions of the Dipit and pateRungan tribes. FPIC, free, prior, and informed consent; ILK, Indigenous and local knowledge; ILSA, integrated landscape and seascape approach; MSP, multi-stakeholder platform; SEPLS, socio-ecological production landscape and seascape.

3.1.1 Where do we want to be in 2050?

By 2050, both the Dipit and pateRungan tribes envision the Xinshe SEPLS as an intact, biodiverse, and thriving Home where harmful practices have ceased and the forest–river–farmlands–ocean continuum is fully reconnected. Ecological restoration and harmony between people and nature are shared goals, though each tribe emphasizes different dimensions.

For Dipit, the vision draws on cultural memory, restoring the biocultural abundance of the 1970s before Highway 11 construction and subsequent outmigration. Anchored in the Jialang/Dabuan Stream, this vision seeks a place of “healing the soul,” where clean waters invite children’s play, shrimp harvests, and flourishing freshwater and marine biodiversity. The pateRungan vision highlights marine recovery—restoring coral reefs, safeguarding coasts, and improving marine transport—sustained by abundant aquatic life and sustainable practices.

Agricultural futures converge on revitalized farmlands rooted in organic and climate-smart practices, blending ILK with modern technologies such as automation, mechanization, AI, and even 3D printing. Dipit emphasizes restoration of native Satoyama species for food and medicine. PateRungan prioritizes revitalizing hunting as Kavalan heritage, managing human-wildlife conflicts, and embedding this knowledge in place-based education.

Both tribes foresee the return of youth who respect traditions, work with elders, and bring new skills. Dipit envisions sharing the Xinshe SEPLS experience across Hualien County, while pateRungan imagines returning youth in leadership roles strengthening local livelihoods. Governance is imagined as joint management of the SEPLS, with collective decisions on land use, eco-tourism, and eco-friendly production while resisting external pressures. Dipit also links its vision to world peace and the global goal of living in harmony with nature.

Livelihoods and wellbeing are framed through eco-friendly products, eco-tourism, biodiversity-based industries, and creative enterprises, ensuring that local skills and passions sustain a prosperous future.

3.1.2 Where do we want to be in 2026?

The 2026 visions of the Dipit and pateRungan tribes mirror their 2050 aspirations but are more specific and grounded in the present, with many shared elements and distinct emphases. Ecosystem health and connectivity is a joint priority. The Dipit tribe focuses on securing reliable household water supply, conducting joint stream patrols, and preventing illegal electric fishing (A: River). The pateRungan tribe adds integrating the forest–river–farmlands–ocean SEPLS-based education into the Xinshe Primary School curriculum, developing marine tourism (e.g., diving, snorkeling), and requiring free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) for coastal projects (A: Ocean).

Visions for sustainable resource use (B) center on eco-friendly farming and native species restoration. Dipit plans to revitalize farmland for local diets, weave Amis knowledge into eco-farming, and establish a nursery for native plants (e.g., Chinese indigo Indigofera tinctoria L. for natural dyeing). The pateRungan tribe aims to create an organic promotion zone on the Xinshe Peninsula, diversify crops, adopt semi-automatic eco-farming technologies, and share native species knowledge nationally, especially with urban residents.

Weaving of ILK and modern science is central to both tribes. Dipit prioritizes a physical and online ILK database to foster respect among returning youth for traditional knowledge (C). PateRungan envisions an ILK library at Xinshe Primary School, continued documentation of local biocultural heritage, and targeted programs for returning youth to learn Indigenous Kavalan and Amis languages while applying professional skills to benefit the Xinshe SEPLS.

Collaborative governance of forest–river–farmlands–ocean resources is shared, with Dipit emphasizing internal discussion mechanisms for resource protection (e.g., community briefings after weekly lunches) and pateRungan stressing equitable task allocation and intergenerational mentorship between elders and youth (D: Social capital). Dipit seeks government policy advocacy for replicating the Xinshe ILSA nationwide (“Scaling”), while pateRungan prioritizes continued project financing aligned with local needs (D: MSP).

Livelihoods and wellbeing (E) link biodiversity-based income, eco-tourism, and improved health and emergency services. Dipit focuses on small-scale processing facilities (e.g., herbal teas, medicinal plants, dyes) and eco-tourism tied to ecological survey data, with revenues supporting elderly welfare. PateRungan envisions branding and marketing local products, eco-tourism integrating agriculture, arts, and environmental interpretation, and road safety improvements along Highway 11.

3.2 How do we get there? Priority objectives by 2026

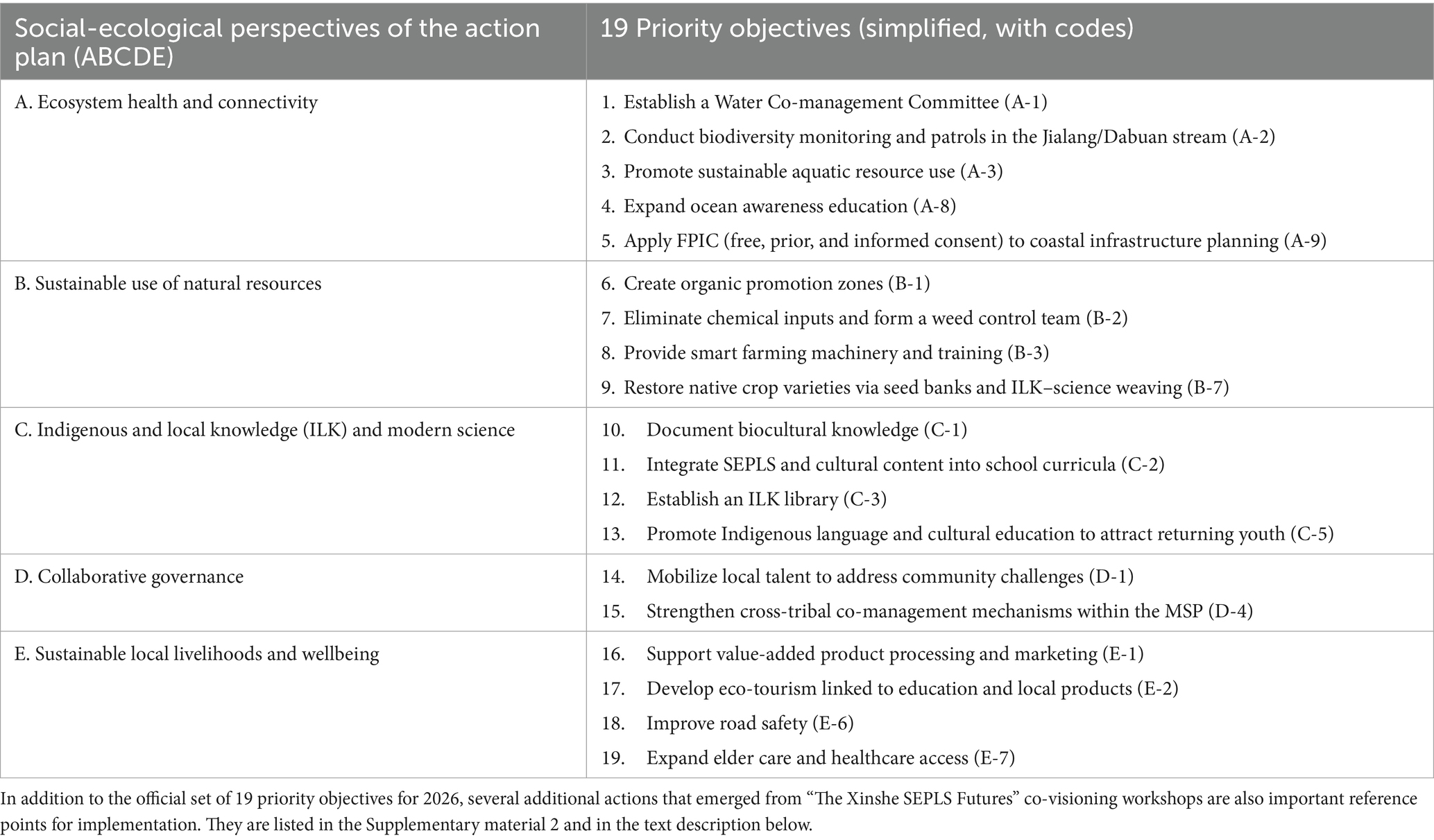

The “Our 2026 Priorities” goal co-setting workshop and its follow up MSP meeting (November–December 2023) identified 19 priority objectives across five perspectives (A–E) and 10 thematic priorities, linking community aspirations with actionable steps and clear stakeholder responsibilities. Detailed results of this future-scaping exercise are presented in Supplementary material 2, while their summary is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. How do we get there? Nineteen priority objectives for the final phase of the mid-term action plan for the Xinshe integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA) (January 2024–December 2026).

Perspective A “Ecosystem health and connectivity”: “River” and “Ocean” priority themes (A-1, A-2, A-3, A-8, A-9). Focuses on safeguarding freshwater and marine ecosystem health. Core actions include establishing a Water Co-management Committee between the two tribes, enhancing stream connectivity through patrols and biodiversity monitoring, promoting sustainable aquatic resource use, expanding ocean awareness, and applying FPIC-based eco-friendly coastal infrastructure to address erosion. Actionable measures range from installing water tanks and conducting anti-electric fishing patrols to implementing nature-based stream engineering, eco-friendly detergents, and signage. Stakeholders include the Dipit and pateRungan tribes, ARDSWC-HB, FANCA-HB, Irrigation Agency, Hualien County Government, Water Resources Agency 9th Branch, Ocean Conservation Administration, Xinshe Primary School, and Fengbin Township Office. Additional actions: research on the Satoyama freshwater indicator species (endemic shrimp) with the integration of ILK (A-5); public awareness and regulation on ocean protection (A-13).

Perspective B “Sustainable use of natural resources”: “Eco-agriculture” and “Native species” priority themes (B-1, B-2, B-3, B-7). Aims to establish organic production zones, eliminate chemical inputs through a weed control team, support labor-saving machinery and training, and restore native crops via seed banks and ILK–science weaving. Actionable steps include on-farm conservation, seed exchanges, adaptive crop rotation, and farmer training. Stakeholders include the tribes, EBAFA, HDARES, FANCA-HB, Guangfeng District Farmers Association, and Xinshe Primary School. Additional actions: documentation and transfer of ecological farming knowledge to local youth and other east coast communities in Hualien and Taitung counties (B-6).

Perspective C “ILK and modern science”: “ILK documentation and transfer” and “Return of migrant youth” priority themes (C-1, C-2, C-3, C-5). Focuses on safeguarding biocultural knowledge, integrating SEPLS and cultural content into education, establishing an ILK library, and promoting language and cultural education to attract youth. Activities include recording elders’ knowledge, organizing youth camps, producing media outputs, teaching Amis and Kavalan languages, and creating local jobs. Stakeholders are the tribes, Xinshe Primary School, Kavalan Indigenous Language Promotion Association, Xinshe Village Head Office, and FANCA-HB.

Perspective D “Collaborative governance”: “Social capital” and “MSP” priority themes (D-1, D-4). Seeks to mobilize local talent and strengthen cross-tribal co-management under the MSP. Actions involve skills mapping elders-youth mentorship programs, regular MSP meetings, and maintaining the Water Co-management Committee. Stakeholders include the tribes, Xinshe Village Head Office, local organizations, and MSP members such as NDHU. Additional actions: improved communication with government agencies (D-6); development of a skills database for youth with administrative capabilities (D-2).

Perspective E “Sustainable local livelihoods and wellbeing”: “Biodiversity-based livelihoods” and “Safety and health” priority themes (E-1, E-2, E-6, E-7). Links biodiversity conservation with economic and social wellbeing of the tribes. Priorities include marketing biodiversity-based products, developing eco-tourism, upgrading road safety, and expanding elder care and health services. Specific actions cover small-scale processing, eco-packaging, marketing networks, communal lunches, traffic safety measures, and healthcare outreach. Stakeholders include the tribes, HDARES, EBAFA, FANCA-HB, ARDSWC-HB, Xinshe Primary School, Xinshe Police Station, Department of Transportation, and Fengbin Township Office. Additional actions: cultivation of fiber dyeing plants (E-3), simplified eco-certification (E-4), and strengthened rural–urban connectivity (E-5).

4 Discussion

4.1 [Problems] translating future-scaping visions into action

A core challenge for each ILSA is tracking place- and time-specific, diverse social–ecological priorities that are central to the “Problems” element of the 5P + S framework. This section addresses our first research question: How did future-scaping tools help identify mid-term (2026) and long-term (2050) visions for the Dipit and pateRungan tribes, and translate them into actionable priorities?

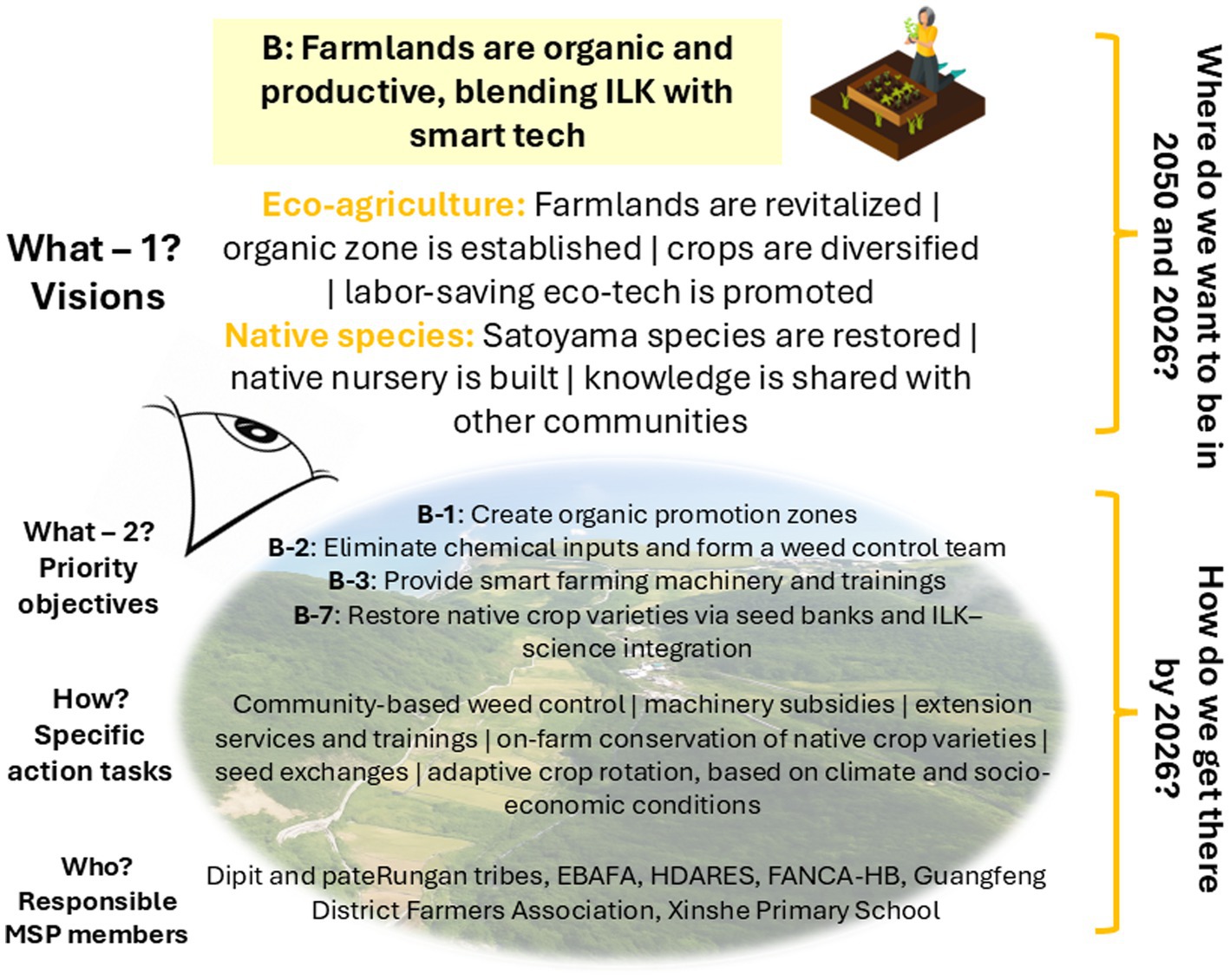

Participatory futures methods, such as visioning and back casting, are increasingly used in place-based social-ecological contexts to co-produce desired futures and chart pathways to achieve them (Ariza-Álvarez and Soria-Lara, 2024). A comparison of Figure 3 (“Where do we want to be by 2050 and 2026?”) with Table 2 (“How do we get there?”) reveals a clear vision-to-action pathway for each social–ecological perspective in the action plan (ABCDE). Perspective B “Sustainable use of natural resources” exemplifies this process, showing how community visions (What-1?) were translated into priority objectives (What-2?), concrete actions (How?), and assigned responsibilities (Who?) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Translating future-scaping visions into action: using Perspective B “Sustainable use of natural resources” as an example. EBAFA, Eastern Branch of the Agriculture and Food Agency; FANCA-HB, Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency- Hualien Branch; HDARES, Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station; ILK, Indigenous and local knowledge; MSP, multi-stakeholder platform.

During “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” co-visioning workshops, for the Perspective B, both tribes envisioned the Xinshe SEPLS in 2050 as organically farmed, productive, and healthy, with restored native crops and Satoyama species (e.g., freshwater shrimp, rattan tree and Indian daisy) and a blend of modern agricultural technologies (e.g., 3D printing of spare parts) with ILK. The 2026 visions were more specific: establish an organic promotion zone in the pateRungan tribe, create a seedling nursery in the Dipit tribe, promote technological innovation, and share these experiences with other SEPLS communities (Figure 4).

During “Our 2026 Priorities” goals co-setting workshop, these visions – refined through negotiation with the Xinshe MSP members (see more in Section 4.2) – were translated into four priority actions (B-1, B-2, B-3, B-7) with defined steps and stakeholders (Figure 4). For example, B-3 was added to support the local vision for smart farming technologies to address labor shortages and free time for ILK documentation and transfer. EBAFA was assigned to provide subsidies for organic farming machinery, while HDARES took charge of related training and extension services. This reflects best-practice back casting identified in the futures literature—for example, in Ethiopia (Jiren et al., 2023), Spain (Ariza-Álvarez and Soria-Lara, 2024), and Brazil (Carvalho-Ribeiro et al., 2024)—where long-term visions are employed to define short-term milestones and assign responsibilities.

4.1.1 Lessons learned

4.1.1.1 Linking visioning to operational planning

By connecting community-derived 2050 and 2026 visions to coded priority objectives and concrete actions, the Xinshe ILSA avoided the mismatch between aspirations and practical implementation (Freedman, 2016). The future-scaping facilitation tools complemented RAWs of 2017–2018 and 2020 by shifting the focus from assessing the present against the past (what RAWs are good for) to envisioning desired futures and mapping realistic pathways to reach them. This approach balances aspiration with feasibility, zooming in on priorities for the Xinshe ILSA’s final years, while also reflecting the principles of a place-based scenario planning in social-ecological research (Oteros-Rozas et al., 2015).

4.1.1.2 Maintaining dual time horizons

Long-term 2050 visions acted as navigational beacons, while near-term 2026 objectives anchored action in the present— a two-horizon logic recommended for sustainability transitions (Pereira et al., 2020). For example, in Perspective E “Sustainable local livelihoods and wellbeing,” 2026 actions included marketing SEPLS produce, adopting eco-friendly packaging, promoting eco-tourism, and using ecological survey data, all aligned with the 2050 goal of a self-sufficient, economically resilient SEPLS.

4.1.1.3 Integrating place-specific priorities

Keeping in mind the “Place” dimension of the 5P + S framework during the future-scaping exercise is important from the spatial connectivity perspective (Raquino et al., 2023). The revised mid-term action plan elevates the spatial vision of the Xinshe SEPLS, emphasizing ridge-to-reef connectivity (A-8), terrestrial-coastal linkages, and the preservation of scenic landscape-seascape qualities (e.g., maintaining natural beauty under B-1). This spatial grounding has strengthened community responsibility for the SEPLS’s future, ensuring that objectives are operationalized through cross-tribal and cross-ecosystem collaboration, including the establishment of a Water Co-management Committee (A-1) as a shared governance mechanism.

4.1.1.4 Embedding responsibilities and resources

Assigning clear responsibilities (“Who?”) and linking them to financing or technical support addressed implementation gaps noted in much ILSA literature (Freedman, 2016; Pedroza-Arceo et al., 2022; Suit et al., 2021). By explicitly assigning MSP responsibilities, linking them to available resources (financial, institutional, legal), and weaving ILK with modern technologies, the Xinshe ILSA addresses gaps noted in the futures literature, which often lacks detail on the follow-up implementation and monitoring (Jiren et al., 2023).

4.2 [People] co-creating inclusive processes for knowledge weaving and meaningful engagement

Ensuring inclusive, equitable engagement across stakeholders, while honoring both ILK and sectoral expertise, is central to the “People” dimension of the 5P + S framework. This is particularly important in SEPLS contexts, where knowledge weaving – the combination of ILK with scientific and technical expertise – is essential for effective planning and governance (Tengö et al., 2014; Galang et al., 2025). In this section, we examine the second research question: How did the future-scaping facilitation tools support inclusive, just, and participatory engagement among the Dipit and pateRungan tribes, four key government agencies, and Xinshe Primary School, and how did these tools contribute to knowledge weaving?

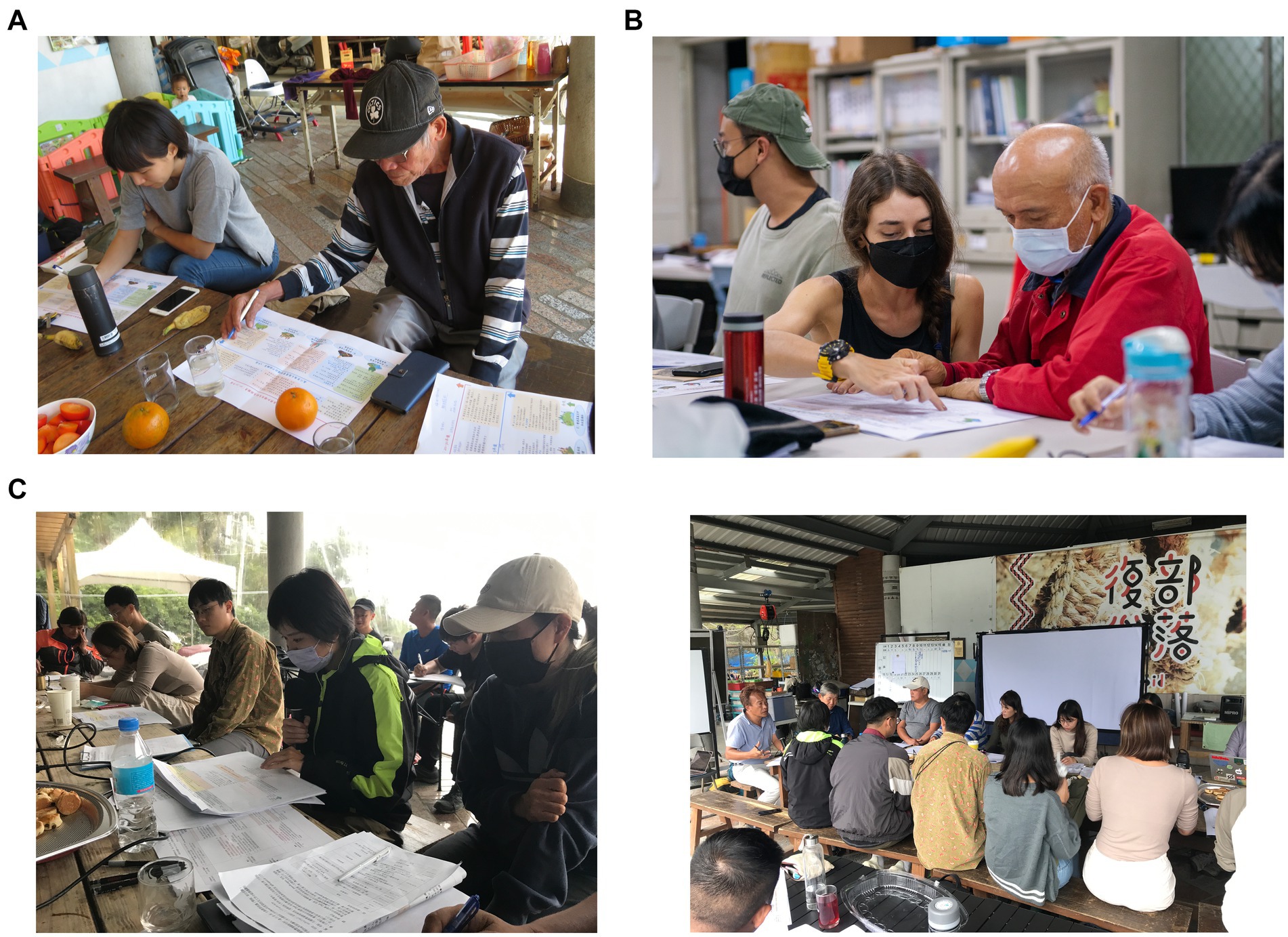

From a facilitation perspective, we applied two distinct but complementary approaches when designing the future-scaping tools: a community-based emphasis for “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” co-visioning workshops (2021–2022) and a multi-stakeholder emphasis for the “Our 2026 Priorities” goal co-setting workshop (2023) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Photos of “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” co-visioning workshops in the Dipit (A) and pateRungan (B) tribes, and “Our 2026 Priorities” goal co-setting workshop with the MSP members (C).

“The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” workshops were designed as a primarily community-based tool to elicit the unique and shared perspectives of the Dipit and pateRungan tribes regarding their 2026 and 2050 futures. This followed two guiding principles. First, vision ownership: the future visions belong to the two tribes, and it is the local people who determine what their landscape–seascape should look like in five or almost 30 years. Second, diversity of voices: participation should reflect a broad range of local perspectives, considering factors such as age, length of residency in the Xinshe SEPLS, and professional background. Such principles align with best practices for co-production processes that are context-based, pluralistic, goal-oriented, and interactive (Norström et al., 2020; Carvalho-Ribeiro et al., 2024).

The “Our 2026 Priorities” workshops shifted the emphasis toward a full MSP, bringing in four key government agencies representing different sectors and Xinshe Primary School. This shift aimed to operationalize the tribal visions in ways that leveraged the sectoral knowledge, technical expertise, and institutional capacities of the agencies, as well as the school’s cultural and educational networks. This mirrors findings from multi-actor governance research, which stress that inclusive MSP can bridge the gap between vision and implementation by aligning actors’ mandates, resources, and capacities (Felipe-Lucia et al., 2022; Jiren et al., 2023; Siangulube et al., 2023).

Perspective A “Ecosystem health and connectivity” illustrates this process. In “The Xinshe SEPLS Futures” workshops, both tribes envisioned the Xinshe SEPLS as a healthy, connected, biodiverse home where people live in harmony with nature (Figure 3). The Dipit tribe placed greater emphasis on freshwater ecosystems, particularly conserving the biotic and abiotic resources of the Jialang/Dabuan stream – recovering shrimp migration routes and ensuring stable household water supplies. The pateRungan tribe emphasized coastal and marine ecosystems, including coral reef monitoring and responsible coastal infrastructure, and envisioned developing ocean-based recreational activities such as diving and snorkeling – an aspiration particularly championed by Kavalan youth.

Building on these place-based visions, the “Our 2026 Priorities” workshops enabled MSP members to “step back to the present” and connect visions to concrete priority objectives and actionable tasks through consultative discussion. FANCA-HB, for example, proposed long-term freshwater biodiversity monitoring to enhance stream connectivity (A-2, Table 2). ARDSWC-HB prioritized nature-based solutions (NbS) to water management, such as eco-friendly stream engineering and reservoir subsidies. To address the five priority objectives (A-1, A-2, A-3, A-8, A-9), additional stakeholders were invited on an ad hoc basis, including the Irrigation Agency, Fengbin Township Office, Hualien County Government, Water Resources Agency 9th Branch, and the Ocean Conservation Administration. This illustrates the adaptive expansion of MSP membership to address emerging needs, a dynamic also highlighted in Ratner et al. (2022), who examined eight landscape-level MSPs across seven countries—Peru, Brazil, India, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

4.2.1 Lessons learned

4.2.1.1 Mindful integration of knowledge systems

Effectively weaving ILK with sectoral and scientific expertise requires tailoring facilitation tools to the knowledge types, perspectives, and priorities of different stakeholder groups (Tengö et al., 2014; Djenontin and Meadow, 2018). In the Xinshe case, the process moved from understanding unique tribal perspectives, to synthesizing joint visions, to discussing concrete actions with government agencies—each stage engaging the most relevant actors for that phase. By staging engagement in this way, we maximized inclusivity at each step, ensured relevance to both community and institutional priorities, and expanded the governance network to meet new needs (Norström et al., 2020).

4.2.1.2 Engaging new and previously marginal actors

Future-scaping catalyzed the deeper involvement of actors who had been absent or peripheral to the MSP. For example, the Ocean Conservation Administration and Fengbin Township Office became more active in implementing Perspective A actions. Similarly, Xinshe Primary School and the Kavalan Indigenous Language Promotion Association emerged as leaders in advancing the “ILK documentation and transfer” and “Return of migrant youth” priorities under Perspective C (Supplementary material 2). This demonstrates the role of futures processes as “boundary objects” that invite new partnerships and broaden coalitions (Franco-Torres et al., 2020).

4.2.1.3 Aligning different outcome expectations

Ensuring the progress of an ILSA—its continuity and impact—requires sensitivity to the varying priorities of different actor groups. For local communities, the main concern is the ecological, productive, cultural, governance, and livelihood conditions of their SEPLS. For government agencies, priorities often align with sectoral mandates and key performance indicators (KPIs). Future-scaping at the final stage of the ILSA process helped surface these distinct priorities and reconcile them in actionable plans, consistent with recommendations for equitable co-management (Felipe-Lucia et al., 2022).

4.3 [Process] co-visioning an adaptive and iterative process into the final stage of the Xinshe ILSA

A defining feature of ILSA as a response to nexus challenges in rural landscapes is its adaptive and iterative nature – ability to evolve in response to changing conditions (Herrmann et al., 2021). In this section, we address the third research question: How did future-scaping facilitation tools contribute to the adaptive co-management process, enabling it to “shift gears” into the concluding stage of the Xinshe ILSA?

To understand their value, it is useful to explore alternative scenarios: without these tools, the Xinshe ILSA would have simply continued to implement the mid-term action plan developed after the second round of RAWs (Karimova et al., 2022) for 6 years without adjustment. While functional, such an approach would have missed opportunities to refocus on the most urgent, locally defined priorities and to align near-term actions with the long-term futures envisioned by the Dipit and pateRungan tribes.

From the outset, we aimed to co-create a transferable model (not directly replicable but valuable as a reference) for other ILSA, illustrating how the mature stage can be most effectively operationalized. Feedback from the tribes and government agencies called for a sharper articulation of final-year goals and the pathways to achieve them. This provided a clear opportunity to integrate future-scaping as a strategic tool within the adaptive co-management cycle. Figure 6 situates each tool within the process timeline of the Xinshe ILSA, links them to mid-term action plan revision cycles, and highlights their targeted application in achieving the 2026 visions.

Figure 6. The adaptive and iterative outcomes of applying the future-scaping tools within the final phase of the Xinshe integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA). ILK, Indigenous and local knowledge; MSP, multi-stakeholder platform; RAWs, resilience assessment workshops; SEPLS, socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes.

4.3.1 Lessons learned

4.3.1.1 Navigating between present and future

Embedding multiple refinement points (in late 2022 and 2023) allowed objectives like A-1 (stream co-management) and B-3 (smart farming) to be re-prioritised toward the final years of the Xinshe ILSA. The process involved moving repeatedly between the current state and desired futures, narrowing the gap step by step. As in other landscape scenario planning processes (Carvalho-Ribeiro et al., 2024; Oteros-Rozas et al., 2015; Waeber et al., 2023), this “back-and-forth” maintained a balance between ambition and feasibility (Freedman, 2016). Figure 6 illustrates how each step brought the plan closer to the locally envisioned 2026 aspirations. Also, positioning future-scaping within the adaptive co-management loop ensured that future orientation was not a one-off exercise but a recurrent driver of the entire process.

4.3.1.2 Emergent and responsive facilitation

Notably, these two series of workshops were not pre-planned at the outset; they emerged “organically” as needs and opportunities arose—demonstrating the adaptive, responsive character of the process. Initially in 2021, inspired by Pereira et al. (2020), only the co-visioning workshops were intended. Yet their outputs revealed strong stakeholder appetite for more goal-oriented, implementation-focused dialogue, leading naturally to the second series (i.e., “Our 2026 Priorities”). This facilitation sensitivity and responsiveness to stakeholder momentum and demand is essential for maintaining engagement in such long-term initiatives as ILSA (Pedroza-Arceo et al., 2022).

4.3.1.3 Co-production as a thread

Throughout, the “co-” prefix—co-management, co-visioning, co-setting—signals the collaborative design, implementation, and learning embedded in each step of the adaptive co-management for the Xinshe ILSA. This aligns with the principles for high-quality knowledge co-production discussed in 4.2 and reinforces that adaptive processes benefit from inclusivity, shared ownership, and iterative adjustment (Norström et al., 2020; Tengö et al., 2014; Djenontin and Meadow, 2018). It underscores mutual respect between ILK and scientific knowledge systems, building trust and legitimacy in decision-making. Here, co-production is both process—integrating diverse perspectives to create shared meaning—and outcome—strengthening local capacity for long-term stewardship. The repeated “co-” actions act as boundary objects, bridging sectors, sustaining engagement, and grounding future visions and actions in place-specific priorities so they remain both community-led and scientifically informed.

5 Conclusion

This study of the Xinshe ILSA illustrates how long-term, place-based initiatives can harness participatory future-scaping to bridge aspirations and action. By centring ILK alongside scientific knowledge, and by embedding co-visioning and goal co-setting within the adaptive co-management cycle, the process fostered trust, legitimacy, and shared ownership among diverse stakeholders. The 2026 and 2050 visions, co-developed by the Dipit and pateRungan tribes with cross-sector partners, informed concrete, locally grounded priorities while keeping sight of broader sustainability goals.

Our findings highlight three interlinked insights. First, future-scaping offers a structured yet flexible methodology to translate collective dreams into actionable pathways, reducing the aspiration–implementation gap. Second, sustained inclusivity—across generations, governance levels, and knowledge systems—strengthens both the quality and durability of outcomes. Third, facilitation roles, often under-recognized, are critical boundary functions that bridge sectors, maintain momentum, and anchor work in place-specific priorities.

Taken together, these insights advance both theory and practice. Theoretically, they demonstrate how facilitation in ILSA can be understood as a boundary function—enabling knowledge weaving, adaptive governance, and the translation of shared visions into implementable strategies. Practically, the Xinshe experience offers transferable lessons for other SEPLS: the value of iterative and participatory visioning tools, the importance of intergenerational and cross-sector inclusion, and the need to embed community-defined priorities within adaptive cycles of planning and action. As the Xinshe ILSA enters its concluding phase, its case affirms that ILSA are not only a viable but necessary response option for navigating complex nexus challenges and realizing long-term sustainability visions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PK: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Software. K-CL: Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture (grant nos. 106AS-4.2.5-ICI1, 107AS-4.2.3-IC-I1, 108AS-4.2.2-IC-I1, and 109AS-4.2.2-IC-I1) and the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (Ministry of Agriculture) (grant nos. 110FD-09.1-HC-01, 111FD-08.1-HC-02, and 112FD-08.1-HC-29).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with gratitude a continued support of many partners for the Xinshe ILSA, in particular the Dipit and pateRungan tribes. Xinshe Primary School, and the four government agencies - HDARES. FANCA- HB, ARDSWC- HB, and EBAFA. Without them, this study would not have been possible. Also, many thanks to Bei-Bei Sun for her supervision and support during research and writing process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1685945/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The river is known by two names: Jialang, the Indigenous Amis name, and Dabuan, the Indigenous Kavalan name.

References

Ariza-Álvarez, A., and Soria-Lara, J. A. (2024). Participatory mapping in exploratory scenario planning: necessity or luxury? Futures 160:103398. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2024.103398

Carvalho-Ribeiro, S., Ferreira, E., Paula, L. G., Rodrigues, R., Drumond, M. A., Purcino, H., et al. (2024). What can be learned from using participatory landscape scenarios in Rio Doce State Park, Brazil? Landsc. Ecol. 39. doi: 10.1007/s10980-024-01860-w

Djenontin, I. N. S., and Meadow, A. M. (2018). The art of co-production of knowledge in environmental sciences and management: lessons from international practice. Environ. Manag. 61, 885–903. doi: 10.1007/s00267-018-1028-3

Felipe-Lucia, M. R., de Frutos, Á., and Comín, F. A. (2022). Modelling landscape management scenarios for equitable and sustainable futures in rural areas based on ecosystem services. Ecosyst. People 18, 76–94. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2021.2021288

Franco-Torres, M., Rogers, B. C., and Ugarelli, R. (2020). A framework to explain the role of boundary objects in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 36, 34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2020.04.010

Freedman, L. P. (2016). Implementation and aspiration gaps: whose view counts? Lancet 388, 2068–2069. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31530-6

Galang, E. I. N. E., Bennett, E. M., Hickey, G. M., Baird, J., Harvey, B., and Sherren, K. (2025). Participatory scenario planning: a social learning approach to build systems thinking and trust for sustainable environmental governance. Environ. Sci. Pol. 164:103997. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2025.103997

Herrmann, D. L., Schwarz, K., Allen, C. R., Angeler, D. G., Eason, T., and Garmestani, A. S. (2021). Iterative scenarios for social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 26, 1–9. doi: 10.5751/ES-12706-260408

IPBES (2025). Concept note for a workshop to reflect on scenarios and models to better account for different knowledge systems, including indigenous and local knowledge systems, and mother earth-centric scenarios and models. Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat.

Jiren, T. S., Abson, D. J., Schultner, J., Riechers, M., and Fischer, J. (2023). Bridging scenario planning and backcasting: a Q-analysis of divergent stakeholder priorities for future landscapes. People Nat. 5, 572–590. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10441

Karim, P. G., and Lee, K. C. (2024a). Landscape approaches for the 30×30 target: potential applications and practical recommendations. PARKS 30:30. doi: 10.2305/PARKS.2024.V30.2

Karim, P. G., and Lee, K. C. (2024b). On the role of the Satoyama initiative and integrated landscape-seascape approaches in achieving the 2050 goal of society living in harmony with nature. ICDF Dev. Focus Q. 18, 10–23.

Karim, P. G., and Lee, K. C. (2025). Conservation and adaptation go hand in hand: On the role of Taiwan ecological network in fostering resilient landscapes and seascapes. Taiwan Insight. University of Nottingham. Available online at: https://taiwaninsight.org/2025/02/19/conservation-and-adaptation-go-hand-in-hand-on-the-role-of-taiwan-ecological-network-in-fostering-resilient-landscapes-and-seascapes/.

Karim, P. G., Lee, K. C., Liao, R. Y., and Chen, M. H. (2024). “You are my mountain, I am your community: rebuilding nature–culture connectivity in Taiwan’s Lishan areas” in Mountain lexicon. eds. F. O. Sarmiento and A. Gunya, vol. 2 (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 321–330.

Karimova, P. G., and Lee, K. C. (2022). An integrated landscape-seascape approach in the making: facilitating multi-stakeholder partnership for socio-ecological revitalisation in eastern coastal Taiwan (2016–2021). Sustainability 14:4238. doi: 10.3390/su14074238

Karimova, P. G., and Lee, K. C. (2023). The many meanings of ‘one’: the concept and practice of the one health approach in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes. CABI One Health 2023:26. doi: 10.1079/cabionehealth.2023.0026

Karimova, P. G., Yan, S. Y., and Lee, K. C. (2022). “SEPLS well-being as a vision: co-managing for diversity, connectivity and adaptive capacity in Xinshe Village, Hualien County, Taiwan” in Nexus among biodiversity, health, and sustainable development in managing socioecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). eds. M. Nishi, S. M. Subramanian, and H. Gupta, vol. 7 (Singapore: Springer Nature).

Kim, H., Peterson, G. D., den Belder, E., Ferrier, S., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S., Kuiper, J. J., et al. (2023). Toward a better future for biodiversity and people: modelling nature futures. Glob. Environ. Chang. 82:102681. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102681

Lee, K.-C., and Karimova, P. G. (2021). From cultural landscape to aspiring geopark: 15 years of community-based landscape tourism in Fengnan Village, Hualien County, Taiwan (2006–2021). Geosciences 11:310. doi: 10.3390/geosciences11080310

Lee, K. C., Karimova, P. G., and Yan, S. Y. (2019). “Towards an integrated multi-stakeholder landscape approach to reconciling values and enhancing synergies: a case study in Taiwan” in Understanding the multiple values associated with sustainable use in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). ed. K. C. Lee, vol. 5 (Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability).

Lee, K. C., Karimova, P. G., Yan, S. Y., and Li, Y. S. (2020). Resilience assessment workshops: an instrument for enhancing community-based conservation and monitoring of rural landscapes. Sustainability 12:408. doi: 10.3390/su12010408

Locatelli, B., Lavorel, S., Colloff, M. J., Crouzat, E., Bruley, E., Fedele, G., et al. (2025). Intertwined people-nature relations are central to nature-based adaptation to climate change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 380:20230213. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2023.0213

Nishi, M., and Yamazaki, M. (2020). Landscape approaches for the post-2020 biodiversity agenda: Perspectives from socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (UNU-IAS Policy Brief No. 21. pp. 1–4). United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability. Available online at: https://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:8033.

Norström, A. V., Cvitanovic, C., Löf, M. F., West, S., Wyborn, C., Balvanera, P., et al. (2020). Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 3, 182–190. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2

O’Brien, K. (2021). You matter more than you think: Quantum social change for a thriving world. New York: cChange Press.

Oteros-Rozas, E., Martin-Lopez, B., Daw, T. M., Bohensky, E. L., Butler, J. R. A., Hill, R., et al. (2015). Participatory scenario planning in place-based social-ecological research: insights and experiences from 23 case studies. Ecol. Soc. 20:32. doi: 10.5751/ES-07985-200432

Pedroza-Arceo, N. M., Weber, N., and Ortega-Argueta, A. (2022). A knowledge review on integrated landscape approaches. Forests 13:312. doi: 10.3390/f13020312

Pereira, L. M., Davies, K. K., den Belder, E., Ferrier, S., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S., Kim, H., et al. (2020). Developing multiscale and integrative nature–people scenarios using the nature futures framework. People Nat. 2, 1172–1195. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10146

Plieninger, T., Bieling, C., Fagerholm, N., Byg, A., Hartel, T., Hurley, P., et al. (2015). The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 14, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.02.006

Raquino, M. E. R., Pajaro, M., Enaje, J. E., Tercero, R. B., Torio, T. G., and Watts, P. (2023). “Capacitating Philippine indigenous and local institutions and Actualising local synergies on restorative ridge-to-reef biodiversity conservation for food security and livelihoods” in Ecosystem restoration through managing socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). eds. M. Nishi and S. M. Subramanian (Berlin: Springer), 247–265.

Ratner, B. D., Larson, A. M., Sarmiento Barletti, J. P., ElDidi, H., Catacutan, D., Flintan, F., et al. (2022). Multistakeholder platforms for natural resource governance: lessons from eight landscape-level cases. Ecol. Soc. 27:202. doi: 10.5751/ES-13168-270202

Siangulube, F. S., Ros-Tonen, M. A. F., Reed, J., Moombe, K. B., and Sunderland, T. (2023). Multistakeholder platforms for integrated landscape governance: the case of Kalomo District, Zambia. Land Use Policy 135:106944. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106944

Suit, K. C., Parizat, R., Friis, A. E., Kaushik, I., Larson, D., Nash, J., et al. (2021). Toward a holistic approach to sustainable development: a guide to integrated land-use initiatives. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Tengö, M., Brondizio, E. S., Elmqvist, T., Malmer, P., and Spierenburg, M. J. (2014). Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 43, 579–591. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3

Waeber, P. O., Carmenta, R., Carmona, N. E., Garcia, C. A., Falk, T., Fellay, A., et al. (2023). Structuring the complexity of integrated landscape approaches: the ILA mixing board tool. Landsc. Res. 48, 67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2023.06.003

Keywords: integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA), future-scaping, participatory co-visioning, adaptive co-management, Indigenous and local knowledge

Citation: Karim PG and Lee K-C (2025) Future-scaping: lessons learned from co-visioning a resilient future within an integrated landscape and seascape approach (ILSA) in eastern coastal Taiwan. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1685945. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1685945

Edited by:

Pradeep K. Dubey, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Mesfin Sahle Achemo, United Nations University, JapanJacolette Adam, Exigent, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Karim and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paulina G. Karim, c2NhcGVzbGFiQGdtcy5uZGh1LmVkdS50dw==

Paulina G. Karim

Paulina G. Karim Kuang-Chung Lee

Kuang-Chung Lee