Abstract

Pulcherriminic acid (PA) relay is a recently discovered phenomenon in which the Bacillus subtilis employs branching biofilms to relay the antimicrobial pigment, pulcherriminic acid towards the pathogen. PA interacts with the free iron in the environment to form the reddish-pink pigment, pulcherimin, which subsequently accumulates on the pathogen depriving them of the essential iron. In Staphylococcus aureus, the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) system plays a vital role in maintaining iron homeostasis, virulence, and biofilm formation. The perspective article discusses the plausible mechanistic insights on the impact of PA relay in hampering the Fur system. Taken together, these findings highlight PA and PA-producing Bacillus species as a promising alternative for mitigating drug resistant S. aureus infections.

Role of iron in microbial pathogenesis

Iron is a crucial micronutrient essential for all microorganisms, as it facilitates their metabolic processes, enzymatic reactions, respiration, and DNA synthesis, and also serves as a cofactor in enzymes that mediate redox reactions (Hammer and Skaar, 2011; Li et al., 2021; Sheldon et al., 2016). In environments where iron is scarce, such as within human hosts or in processed food, bacteria employ sophisticated siderophore–mediated uptake systems and heme acquisition pathways to survive and establish biofilms (Saha et al., 2025; Sheldon et al., 2016; Weinberg, 2004). Robust Biofilm formation represents a major virulence strategy, enabling pathogens to persist in hostile environments and tolerate antimicrobial interventions (Charron et al., 2025), is tightly linked to iron levels, where excess iron promotes aggregation, while scarcity results in motility and reduced adherence (Conroy et al., 2019; Sheldon et al., 2016). The competition for iron between the host and pathogen has significantly influenced the evolution of both groups in this complex relationship. Hosts have developed nutritional immunity mechanisms to sequester iron and limit its availability to invading pathogens, and bacteria have countered with increasingly sophisticated iron acquisition systems (Hood and Skaar, 2012). Even small shifts in iron availability within food environments or on processing surfaces can significantly alter microbial dominance, influencing both product safety and shelf–life (Carrascosa et al., 2021). Consequently, limiting iron availability can effectively impair bacterial growth and virulence (Sheldon et al., 2016), making iron metabolism a valuable target for novel antibiofilm strategies.

Staphylococcus aureus and iron regulation

Staphylococcus aureus is a notorious food-borne pathogen whose virulence is intricately fastened to iron acquisition and biofilm formation (Lin et al., 2012, Lin et al., 2012; Paiva et al., 2021; Van Dijk et al., 2022). This bacterium is a major concern in food safety due to its capacity to spoil food products and cause food poisoning. Its virulence is driven by multiple factors, including enterotoxin production and strong biofilm formation, which enhance its tolerance to antimicrobials (Fetsch and Johler, 2018; Paiva et al., 2021; Phan et al., 2025; Sergelidis and Angelidis, 2017). S. aureus relies on multiple iron-acquisition strategies: the ferric-uptake regulator (Fur) controls high-affinity siderophores (staphyloferrin A/B), heme uptake via the Isd pathway, and the Cnt system for nickel/cobalt. These pathways are up-regulated during iron limitation (Batko et al., 2021; Ghssein and Ezzeddine, 2022). Iron availability significantly impacts S. aureus biofilm formation, toxin production, and overall virulence, highlighting the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) system as an attractive target for antimicrobial intervention (Lin et al., 2012; Van Dijk et al., 2022).

The Fur system

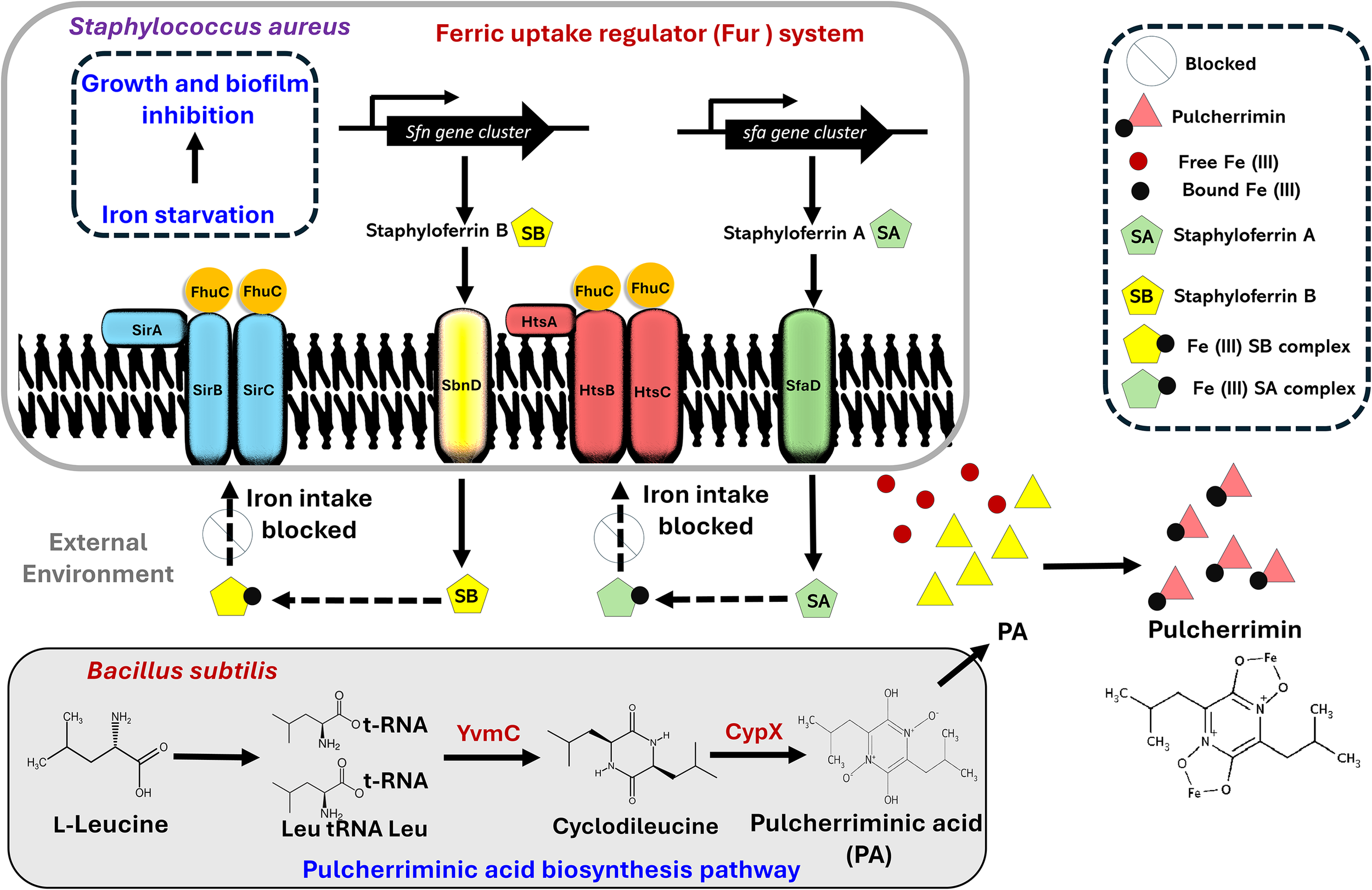

The siderophores staphyloferrin A and B are synthesized via nonribosomal peptide synthetase-independent pathways. The efficient scavenge extracellular ferric iron, which is subsequently imported through ATP-binding cassette transporters, specifically htsABC for staphyloferrin A, as well as sirABC for staphyloferrin B, frequently with the assistance of the ATPase FhuC. Regulation of these genes is mediated by the ferric uptake regulator protein (Fur), which regulates siderophore biosynthesis as well as transport to occur mostly under conditions of iron deprivation. Current studies suggest that reductases, including IruO as well as NtrA, participate in reducing as well as releasing iron in its soluble form from siderophore-iron complexes intracellularly. Furthermore, SbnI, a heme-binding regulatory protein, links siderophore biosynthesis with intracellular heme sensing, revealing a complex interplay between heme- and siderophore-mediated iron metabolism (Beasley and Heinrichs, 2010; Conroy et al., 2019; Hammer and Skaar, 2011). The concept of iron deprivation as an antimicrobial tactic has gained attention due to the integral role of iron in biofilm development and virulence expression (Sheldon et al., 2016). Iron restriction strategies aim to destabilize bacterial growth through “nutritional immunity” or exogenous chelation. Host systems naturally deploy proteins, such as transferrin and lactoferrin to deprive pathogens of this essential nutrient (Hammer and Skaar, 2011). Artificial chelating agents, including EDTA, β-thujaplicin, or deferoxamine, mimic this mechanism and effectively inhibit biofilm development by destabilizing iron homeostasis (Bereswill et al., 2022; Saha et al., 2025; Soldano et al., 2020). However, synthetic chelators often pose biocompatibility and safety concerns in food applications. This has shifted scientific interest toward microbial molecules with self-regulated eco-friendly, and food-grade iron chelating properties.

Pulcherriminic acid relay; a Bacilli route to attack pathogens

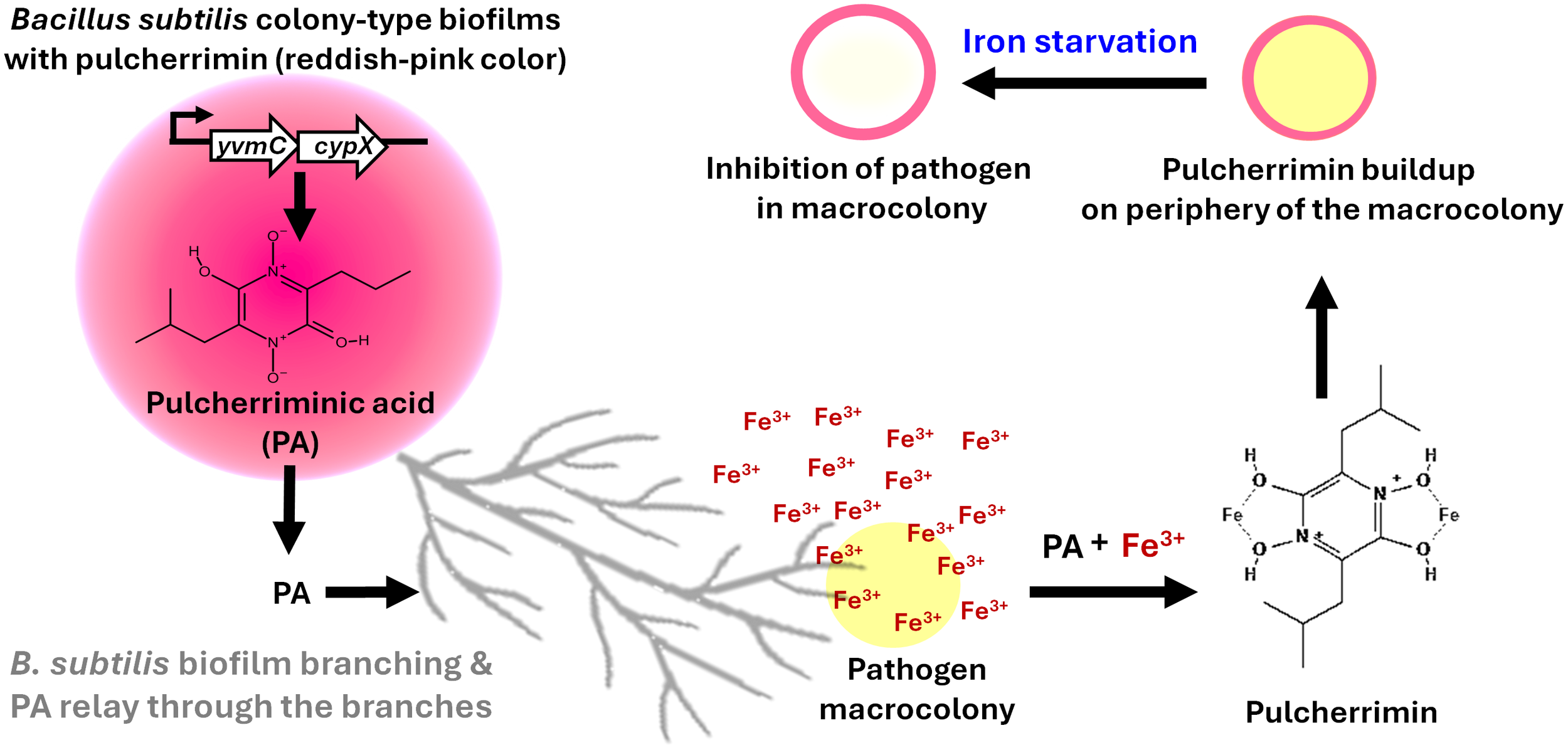

Pulcherriminic acid (PA) has emerged as a promising cyclic dipeptide with potent activity against several pathogens. The pigment is synthesized intracellularly as PA by the action of two key enzymes, YvmC and CypX, in B. subtilis cells, and PA diffuses out of the cell and complexes with free iron to form pulcherrimin (Angelini et al., 2023; Arnaouteli et al., 2019) (Figures 1, 2). Recent studies have shed light on its mechanism of action and relay, underscoring its therapeutic potential (Angelini et al., 2023; Arnaouteli et al., 2019; Charron-Lamoureux et al., 2023). Notably, B. subtilis strategically relays the pulcherrimin precursor, pulcherriminic acid, within developing antagonistic biofilms to counteract pathogens (Figure 1). The mechanism of PA relay was first shown by our group in C. albicans (Rajasekharan et al., 2025). This targeted delivery system ensures localized iron chelation precisely at the sites where the pathogen attempts to establish itself, effectively halting its growth and suppressing morphological switching (Rajasekharan et al., 2025). The core mechanism behind this involves the disruption of C. albicans iron uptake systems. By strongly binding Fe³+ ions, pulcherrimin induces a state of iron starvation. The “targeted relay” delivery mechanism offers a novel framework for optimizing pulcherrimin or precursor-based formulations in future therapeutic strategies. This finding paves the way for exploiting iron acquisition mechanisms as a therapeutic agent against other pathogens, notably S. aureus, which also reveals a similar phenomenon (data not shown). We believe that this new interaction and pigment relay is a competitive ecological strategy by B. subtilis to suppress competitors within mixed microbial communities.

Figure 1

The established concept of pulcherriminic acid relay by Bacillus subtilis for control of pathogens. B. subtilis colony-type biofilm produces pulcherriminic acid (PA) which is relayed through branching structures toward the neighbouring pathogen. PA chelates environmental ferric iron (Fe³+) in the vicinity of the pathogen, forming the insoluble reddish-pink pigment pulcherrimin at the periphery of the pathogen macrocolony. This sequestration of Fe³+ causes iron starvation within the pathogen, leading to growth inhibition.

Figure 2

Proposed model depicting the interaction between Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis. S. aureus uses the Fur system to acquire Fe (III) from the external environment via the formation of siderophore-iron (staphyloferrin A-Fe (III) and staphyloferrin B-Fe (III)) complexes. During competition with B subtilis (a strain known to secrete pulcherriminic acid (PA)), PA diffuses to the external environment, hijacks the free iron and precipitates as pulcherrimin, thus limiting the availability of iron to form the siderophore-Fe (III) complexes, thereby leading to iron starvation and inhibition of S. aureus.

Proposed model to block the Fur system

S. aureus uses the Fur system to acquire iron from the external environment via the formation of siderophore-iron complexes. Fur systems rely on high-affinity chelators staphyloferrin A and B, which are also synthesized by non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-independent routes. The siderophores scavenge extracellular ferric iron and transport via ATP-binding cassette transporters, specifically HtsABC for staphyloferrin A, as well as SirABC for staphyloferrin B, with the help of the ATPase FhuC. As illustrated in Figure 2, we suggest that the pulcherriminic acid secreted by B. subtilis is released into the external environment, where it binds the free iron to form the reddish pink pulcherrimin, thus depriving S. aureus of essential iron required for the formation of siderophore-iron complexes. Overall, the inability to form iron-siderophore complexes prevents any iron intake into the S. aureus cell, thus compromising the overall mechanistic framework, ultimately compromising cellular metabolism and viability.

PA represents the primary bioactive molecule responsible for antimicrobial activity in Bacillus species, functioning through iron chelation and subsequent nutrient deprivation. The antimicrobial efficacy of this system is therefore highly context-dependent and shaped by competitive iron-acquisition strategies within microbial communities. For instance, B. subtilis can partially overcome PA-mediated iron sequestration through the production of the high-affinity siderophore bacillibactin, enabling iron recovery from pulcherrimin complexes, whereas competing pathogens lacking comparable metallophore systems are more susceptible to iron starvation (Charron-Lamoureux et al., 2023). In addition, PA exhibits pronounced photosensitivity and undergoes light-induced degradation, a process shown to dynamically regulate iron availability and biofilm development in B. subtilis (Kobayashi et al., 2025). This property has significant implications for applied use, as light exposure during food processing, storage, or transport may reduce PA stability and limit the persistence of its antimicrobial effect. Consequently, effective deployment of PA-based biocontrol strategies must account for both microbial competition for iron and environmentally driven modulation of PA activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of Bacillus-derived pulcherriminic acid in food safety shows strong potential. As a naturally occurring, broad-spectrum antimicrobial, PA effectively targets iron-dependent pathogens and can complement conventional preservatives and antibiotics. By limiting iron availability to competing microorganisms, PA functions as a promising biocontrol agent. Its natural origin, stability, and compatibility with food systems make it an appealing candidate for sustainable and safe food protection strategies.

Statements

Author contributions

RS: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. CR: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology. TS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization. RB: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. SR: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Formal analysis, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The financial support provided to RS in the form of PhD fellowship by SRMIST is thankfully acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge SRMIST for providing the necessary infrastructure and research facilities. The authors thank SKR and RB lab members for their support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author RB declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Angelini L. L. Dos Santos R. A. C. Fox G. Paruthiyil S. Gozzi K. Shemesh M. et al . (2023). Pulcherrimin protects Bacillus subtilis against oxidative stress during biofilm development. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes.9, 50. doi: 10.1038/s41522-023-00418-z

2

Arnaouteli S. Matoz-Fernandez D. A. Porter M. Kalamara M. Abbott J. MacPhee C. E. et al . (2019). Pulcherrimin formation controls growth arrest of the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.116, 13553–13562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903982116

3

Batko I. Z. Flannagan R. S. Guariglia-Oropeza V. Sheldon J. R. Heinrichs D. E. (2021). Heme-dependent siderophore utilization promotes iron-restricted growth of the Staphylococcus aureus hemB small-colony variant. Journal of Bacteriology. 203(24), 10–1128. doi: 10.1128/jb.00458-21

4

Beasley F. C. Heinrichs D. E. (2010). Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in the staphylococci. J. Inorg. Biochem.104, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.09.011

5

Bereswill S. Mousavi S. Weschka D. Buczkowski A. Schmidt S. Heimesaat M. M. (2022). Iron deprivation by oral deferoxamine application alleviates acute campylobacteriosis in a clinical murine campylobacter jejuni infection model. Biomolecules.13, 71. doi: 10.3390/biom13010071

6

Carrascosa C. Raheem D. Ramos F. Saraiva A. Raposo A. (2021). Microbial biofilms in the food industry—A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health.18, 2014. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042014

7

Charron-Lamoureux V. Haroune L. Pomerleau M. Hall L. Orban F. Leroux J. et al . (2023). Pulcherriminic acid modulates iron availability and protects against oxidative stress during microbial interactions. Nat. Commun.14, 2536. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38222-0

8

Charron R. Lemée P. Huguet A. Minlong O. Boulanger M. Houée P. et al . (2025). Strain-dependent emergence of aminoglycoside resistance in Escherichia coli biofilms. Biofilm.9, 100273. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2025.100273

9

Conroy B. Grigg J. Kolesnikov M. Morales L. Murphy M. (2019). Staphylococcus aureus heme and siderophore-iron acquisition pathways. BioMetals.32, 409–424. doi: 10.1007/s10534-019-00188-2

10

Fetsch A. Johler S. (2018). Staphylococcus aureus as a foodborne pathogen. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep.5, 88–96. doi: 10.1007/s40588-018-0094-x

11

Ghssein G. Ezzeddine Z. (2022). The key element role of metallophores in the pathogenicity and virulence of staphylococcus aureus: A review. Biology.11, 1525. doi: 10.3390/biology11101525

12

Hammer N. Skaar E. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.65, 129–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102851

13

Hood M. I. Skaar E. P. (2012). Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen–host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.10, 525–537. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2836

14

Kobayashi K. Kurata R. Tohge T. (2025). The iron chelator pulcherriminic acid mediates the light response in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Nat. Commun.16, 5446. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-60560-4

15

Li C. Pan D. Li M. Wang Y. Song L. Yu D. et al . (2021). Aerobactin-mediated iron acquisition enhances biofilm formation, oxidative stress resistance, and virulence of yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Front. Microbiol.12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.699913

16

Lin M.-H. Shu J.-C. Huang H.-Y. Cheng Y.-C. (2012). Involvement of iron in biofilm formation by staphylococcus aureus. PloS One.7, e34388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034388

17

Paiva W. De Souza Neto F. E. Brasil-Oliveira L. Bandeira M. G. L. Paiva E. Batista A. (2021). Staphylococcus aureus: a threat to food safety. Res. Soc Dev. 10. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v10i14.22186

18

Phan A. Mijar S. Harvey C. Biswas D. (2025). Staphylococcus aureus in foodborne diseases and alternative intervention strategies to overcome antibiotic resistance by using natural antimicrobials. Microorganisms.13, 1732. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13081732

19

Rajasekharan S. K. Angelini L. L. Kroupitski Y. Mwangi E. W. Chai Y. Shemesh M. (2025). Mitigating Candida albicans virulence by targeted relay of pulcherriminic acid during antagonistic biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Biofilm. 9, 100244.

20

Saha S. RoyChowdhury D. Khan A. H. Mandal S. Sikder K. Manna D. et al . (2025). Harnessing the effect of iron deprivation to attenuate the growth of opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.69, e01689-24. doi: 10.1128/aac.01689-24

21

Sergelidis D. Angelidis A. (2017). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a controversial food-borne pathogen. Lett. Appl. Microbiol.64 (6), 409–18. doi: 10.1111/lam.12735

22

Sheldon J. R. Laakso H. A. Heinrichs D. E. (2016). Iron acquisition strategies of bacterial pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr.4, 4.2.05. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0010-2015

23

Soldano A. Yao H. Chandler J. R. Rivera M. (2020). Inhibiting iron mobilization from bacterioferritin in pseudomonas aeruginosa impairs biofilm formation irrespective of environmental iron availability. ACS Infect. Dis.6, 447–458. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00398

24

Van Dijk M. C. De Kruijff R. M. Hagedoorn P.-L. (2022). The Role of Iron in Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Human Disease: A Metal Tug of War at the Host—Microbe Interface. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.857237

25

Weinberg E. D. (2004). Suppression of bacterial biofilm formation by iron limitation. Med. Hypotheses.63, 863–865. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.04.010

Summary

Keywords

antibiofilm, B. subtilis , biofilm, fur system, pulcherrimin, S. aureus

Citation

Srinivasan R, Raorane CJ, Saravanan TS, Briandet R and Rajasekharan SK (2026) Pulcherriminic acid relay; a Bacilli route to attack pathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1740921. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1740921

Received

06 November 2025

Revised

19 December 2025

Accepted

26 December 2025

Published

20 January 2026

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

María Leyre Lavilla- Lerma, University of Jaén, Spain

Reviewed by

Vincent Charron-Lamoureux, University of California, San Diego, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Srinivasan, Raorane, Saravanan, Briandet and Rajasekharan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Romain Briandet, romain.briandet@inrae.fr; Satish Kumar Rajasekharan, satishkr2@srmist.edu.in

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.