- Mepco Schlenk Engineering College, Sivakasi, India

The core objective of this study is to develop a novel method to measure and improve standard spoken English pronunciation accuracy in relation to a desired accent style using current speech processing and information retrieval methods. The system employs the ECAPA-TDNN model, which has been fine-tuned with American-accented speech to create speaker embeddings from the user’s audio. Accent embeddings from reference accent speech samples are subsequently compared using cosine similarity to arrive at an Accent Similarity Score (ASS). At the same time, the user speech is transcribed using the Whisper ASR model (open-source software), then aligned using a forced alignment tool with a reference sentence at the phoneme level. In automatic classification, the level of proficiency (Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced) is attributed to the users on the basis of semantic and phonetic closeness and measures of comprehensible mistakes. For training, the system utilizes the user’s fluency profile to create a particular YouTube query through SerpAPI, providing related and quality resources for pronunciation, their native and accent gaps being considered. An experimental study was conducted among 30 undergraduate students. Experimental evaluations have shown that our two-metric engine provides a scalable and adaptable solution to real-time accent evaluation with classification accuracy of 91.3, 88.6, and 93.1% across beginner, intermediate, and advanced users, respectively. The system provided a strong negative correlation (r = −0.82) between PER and ASS, while indicating that users received a score of 4.6/5 on satisfaction in initial usability studies.

1 Introduction

A Tamil speaking (one of the classical languages in India) student about to interview at a university in the U. S., but the student pronounces the word “think” or “very” in ways that a native English speaker would not. The student’s grammar and vocabulary in English are great, but their comfort with an accent causes misunderstanding and reduced confidence. These types of problems are frequently faced by learners of English, especially when accounting for the lack of authentic, one-on-one feedback in real time. The need for the clarity of pronunciation and accent has been a recognized component of successful communication in spoken English even more so for their less well-developed interlocutors. Many learners continued to show good control of many aspects of grammar and vocabulary, as well as armed with some general proficiency in the language, were still unable to communicate efficiently; the gap was filled with misunderstanding, and self-efficacy was lost. Conventional language instruction, whether in a classroom or on-line, has largely been noun-led (and noun-focused), and mostly pedagogically focused on teaching syntax and vocabulary development without enough specific individual pronunciation instruction.

Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) systems had not sufficiently addressed the nuanced needs of learners from diverse linguistic backgrounds. Most existing systems either provided static drills or used basic ASR feedback mechanisms that offered little insight into accent-specific issues. Although learners might receive feedback on phoneme correctness, they were rarely offered dynamic, native-language-informed pathways for improvement. This lack of tailored, real-time feedback restricted the learner’s ability to correct errors influenced by their first language (L1) phonetic structure. Driven by these ongoing gaps, the study introduced Photometric, a two-metric engine to measure and improve spoken English pronunciation in reference to an accent - in this instance, American English. The system contained two foundational components: an Accent Similarity Score (ASS) and Phoneme Error Rate (PER). The ASS was based on embeddings obtained through the ECAPA-TDNN model that was specifically trained on American-accented speech. The model embeddings had captured individual speaker characteristics and the embeddings were then compared to the native references using cosine similarity to obtain a measure of similarity of accent relative to the native reference. At the same time, the Whisper ASR model transcribed user speech, which was aligned, at the phoneme level, using the Montreal Forced Aligner (MFA). Individual deviations at the phoneme level can include substitutions, insertions, or deletions. The phone error rate (PER), informed by the corpus of transcribed segments, described the phoneme level articulation issues, thus providing additional insight into the larger accent assessment represented by the embedding-based score. To link evaluation with actual improvement, the system created personalized content recommendations based on the learner’s ASS, PER, and background in L1. With the use of SerpAPI, the system dynamically fetched relevant pronunciation resources from various platforms, including YouTube, that were specifically gendered for the user’s native accent profile and their current proficiency level. This approach marked a substantial advancement in pronunciation training, not only through the dual-metric framework but also by facilitating scalable, real-time, and personalized feedback. The integration of deep learning-based speech processing with intelligent content retrieval mechanisms allowed learners to move beyond passive feedback and into active, informed learning pathways. By focusing on accent similarity and phonetic precision simultaneously, this system offered a new paradigm in automated pronunciation coaching, combining objective analysis with tailored pedagogy.

2 Literature review

Computer-aided language learning (CALL) came to develop further with the twin inventions of automatic speech recognition (ASR) and speaker verification. Initially CALL systems relied largely on rule-based or simplistic methods, usually imputing short feedback on the pronunciation of learners, with the focus generally on whether a phoneme was wrong or right, but without looking at speaker accent or fluency in a larger context. With the rise of ASR engines such as Google Speech-to-Text, Kaldi (Povey et al., 2011), language learning platforms began incorporating automatic transcription capabilities, allowing learners to visualize their spoken output compared to reference text. However, most of these ASR-based systems evaluate pronunciation only in terms of word or sentence-level correctness, rather than deeper accentual features. For instance, while Kaldi and DeepSpeech can effectively transcribe words, they do not assess how “native-like” the pronunciation is (Povey et al., 2011), nor do they provide guidance tailored to specific accentual deviations. Thus, these systems are better suited for fluency evaluation or listening comprehension but fall short in accent coaching, which requires a finer-grained analysis. Yuan and Liberman (2008) conducted speaker identification research using the SCOTUS corpus, demonstrating that acoustic-phonetic features are effective in distinguishing speakers. Wu et al. (2006) demonstrated real-time synthesis of Chinese visual speech and facial expressions using MPEG-4 FAP features, offering early insights into multimodal approaches that complement speech-based language learning systems. By contrast, speaker verification has produced powerful speaker embedding models such as x-vector, d-vector, and most recently, ECAPA-TDNN (Desplanques et al., 2020; Emphasized Channel Attention, Propagation, and Aggregation). These models yield fixed-dimensional vector representations of speech, capturing great details about voice attributes which include accent, prosody, rhythm, and intonation. Research findings have proven such embeddings to be sensitive enough to perceive differences between speakers of different dialects or accents of the same language. While these have chiefly been developed for biometric authentication (Nagrani et al., 2017; Zeinali et al., 2019) and speaker diarylation, little attention has been paid to their application from the language learning perspective (Kim et al., 2022; Qian et al., 2016). Franco et al. (1997) pioneered automatic pronunciation scoring for language instruction, establishing an early framework that influenced subsequent developments in computer-assisted pronunciation training. Ravanelli and Bengio (2018) proposed convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that processes raw audio waveforms directly, circumventing the need for traditional, hand-crafted features. Thorndahl et al. (2025) inculcated speech language pathology to effectively assess, manage, and treat individuals with speech disorders.

Tools like Gentle, Montreal Forced Aligner (McAuliffe et al., 2017), and MAUS carry out phoneme-level alignment from speech to reference transcriptions, thus spotting phoneme substitutions, deletions, or insertions-all of these being relevant for pronunciation training. These aligners, paired with the output of an ASR, can actually provide feedback of where the learners deviate from native patterns of articulation. But they do have their limitations: not really something a classful of users can just set up, no real-time feedback, and just do not do too well with code-switched or accented speech. Pappagari et al. (2020) demonstrated the strong dependency between emotion and speaker recognition. A key finding is that a speaker’s emotional state, particularly anger, can negatively impact the performance of speaker verification systems. Wubet et al. (2023) demonstrated the extracting shared acoustic features from a group of speakers with the same native language significantly improves the accuracy of neural network-based accent classification models. The other set of research pertains to CALL sites (Qian et al., 2016) where scripted pronunciation lessons or gamified phoneme drills are administered. Elsa Speak, Duolingo, and SpeechAce are a few examples of such platforms. These platforms provide predetermined feedback based on possible pronunciations and often come with visual aids. However, they lack dynamic personalization, meaning learners with the same native language or accent profile are treated as one big group. And, more importantly, the feedback cannot adapt dynamically based on the learner’s developing strengths and weaknesses in real-time. Chermakani et al. (2023) suggested a silent videos, which helps the learners to stimulate a new paradigm in speaking. A review of these technologies highlights a persistent gap in adaptive accent training tools. Specifically, there is an absence of systems that combine:

• Global accent similarity scoring using embeddings,

• Fine-grained phoneme error analysis, and

• Automated content recommendation tailored to the learner’s current proficiency level and native language.

This study addresses these unmet needs with a new pipeline that combines ECAPA-TDNN for accent similarity, Whisper ASR for high-fidelity transcription and fine-grain phoneme segmented transcription, and a recommendation engine based on YouTube that can provide targeted pronunciation video resources; (Kim et al., 2022). In contrast to static platforms, we built the proposed system to be real-time, scalable and patronizable, providing learners not only feedback, but also actionable resources for improvement that considers their native language. This study also proposed a novel direction for CALL by using accent embeddings, phonetic level diagnostics, and tailor resources for studying pronunciation, extending the scope of CALL beyond a basic transcription-based to include accent-informed coaching (Baevski et al., 2020); a meaningful step toward offering pronunciation training that is accessible, effective, and intelligent.

3 Preliminaries

This section describes very briefly the key models, metrics, and computational procedures forming the backbone of the proposed system. A rudimentary understanding of these ingredients is needed to understand the design choices involved in the methodology.

3.1 Dataset

The LibriTTS dataset consists of over 585 h of high-quality speech from 2,456 speakers, recorded at 24 kHz sampling rate and down sampled to a 16 kHz mono-channel WAV format for compatibility with the ECAPA-TDNN model and Whisper ASR. For this study, a selected subset of recordings was selected that included native American English speakers reading phonetically rich sentences that represented a wide range of English phonemes, intonation, and prosodic variation. The complete corpus includes orthographic transcription of every audio clip, to produce the phoneme-level alignment with the Montreal Forced Aligner (MFA). The selected reference sentences will be used both to create speaker embeddings to score accent similarity and as a phonetic baseline for error detection during the analysis of pronunciation (Figure 1).

3.2 Speaker embeddings and ECAPA-TDNN

The numerical representation of speaker characteristics is called speaker embedding. This embedding incorporates pitch, timbre, prosody, and accentual patterns. The system uses ECAPA-TDNN (Emphasized Channel Attention, Propagation, and Aggregation in Time Delay Neural Networks), a newer architecture that has gained wide acceptance in speaker verification. It differs from older architectures because it uses channel attention and multi-layer feature aggregation to better highlight subtle variations between speaker identities as well as between accents. In this paper, ECAPA-TDNN is fine-tuned on American-accented speech recordings and utilized to produce fixed-length vectors from user audio to compare against native speaker references.

3.3 Automatic speech recognition (ASR) and whisper

Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) transcribes spoken language into written text. The current system uses the Whisper ASR model trained using multilingual and multi-accented datasets, so it is robust against speaker variability and background noise. Moreover, Whisper demonstrates consistent results across either accent, which is ideal in pronunciation assessments for speakers of other languages. The transcription produced by Whisper, therefore, is a great first step for phoneme-level analysis, since it provides a valid representation of the user’s speech on paper.

3.4 Phoneme Alignment and Montreal Forced Aligner

Overlapping segments of speech to phonemes in reference transcriptions is called phoneme alignment. This is important for identifying pronunciation errors related to phoneme substitution, phoneme deletion, and phoneme insertion. The Montreal Forced Aligner (MFA) is used to perform this phoneme alignment task. MFA aligns the ASR transcription to a specific phonetic sequence. Given this phonetic sequence, the MFA forced alignment will indicate the points and manner in which the user’s articulation is not aligned with native pronunciation. This phoneme-level information is useful for accurate feedback and tailored guidance.

3.5 Cosine similarity for accent comparison

Cosine similarity metric is employed to measure the closeness of the user’s accent to that of a native speaker; cosine similarity measures the angular separation between two embedding vectors. A higher cosine similarity indicates more similarities between the user’s voice and accent. The resulting value is normalized to a 0–100 scale and termed an Accent Similarity Score (ASS), and this ASS score is used as one of the markers of pronunciation quality.

3.6 Phoneme error rate

Phoneme Error Rate (PER) is an industry standard evaluation of phonetic quality in terms of pronunciation. It computes the percentage of errors made at the phoneme level, against the total number of phonemes that should have been produced. There are three types of errors: substitutions (incorrect pronunciation of phonemes), deletions (omitted phonemes), and insertions (added phonemes). PER is expressed as a percentage which means the smaller the percentage, the better the pronunciation.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research design

An experimental study was conducted among 30 undergraduate learners in India. The objective is to develop an end-to-end automated system for accent assessment and pronunciation feedback for English language learners. The automated analysis system includes three major components: (i) an assessment of accent similarity making use of speaker embeddings; (ii) phoneme levels of pronunciation error assessments; and (iii) recommendations of dynamic content to improve on. For this step (i) we extracted user audio speaker embeddings by making use of the ECAPA-TDNN model and calculated the similarity between the user embeddings and native American English embeddings through cosine similarity, and (ii) we transcribed the user’s speech using Whisper ASR and forced-aligned that with the reference phoneme transcript to identify any phoneme-level pronunciation errors. Accordingly, based on the outcome of user accent similarity, and phoneme error rate, users were situated in a proficiency level, and relevant exercise or YouTube videos were recommended (Figures 2, 3).

4.2 Data collection

Users will be instructed to record their own version of the same phonemes that were produced in the reference corpus. The reading aloud - will be recorded through a microphone-enabled system by existing web-based or desktop applications. A standard computer wired or wireless microphone will suffice. The audio input will be saved in WAV file format with a 16 kHz sampling rate, with a mono channel. All user recordings will be secure, and will be de-identified before the processing begins. The data collection will be completely voluntary, where each user will start the data collection with a form of informed consent for participants, explaining how the data, once recorded, will be used, the length of time it will be secured, and privacy rights.

4.3 Accent similarity computation

To compute accent similarity, ECAPA-TDNN(Desplanques et al., 2020) speaker embeddings are extracted for both the user and the native reference recording of the same sentence. These embeddings are compared using cosine similarity as follows:

where e_u is the embedding vector of the user and e_r is the embedding vector of the reference accent. The similarity score S lies between −1 and 1, which is linearly scaled to a range of 0 to 100 to yield the Accent Similarity Score (ASS). A score closer to 100 implies a higher degree of similarity between the user’s accent and the native reference.

Sample Testing Outcome

{

“user_id”: “U0123,”

“sentence”: “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,”

“accent_similarity_score”: 67.4 // scaled to [0–100] }

4.4 Phoneme-level error analysis

Whisper ASR (Radford et al., 2023) is employed to transcribe the user’s spoken input. The resulting transcription is then force-aligned with the phonetic transcript of the reference sentence using the Montreal Forced Aligner (MFA). This alignment enables the detection of three types of pronunciation deviations: substitutions (where one phoneme is replaced by another, e.g., /θ/ becomes /t/), deletions (omission of expected phonemes), and insertions (additional phonemes not present in the target). The Phoneme Error Rate (PER) is calculated using the formula:

Whereas,

S - number of substitutions.

I - insertions.

D - deletions.

T - total number of phonemes in the reference sentence.

This percentage provides a quantitative measure of the user’s phonetic deviations from the expected accent.

Sample Testing Outcome

{

“sentence”: “Think before you act,”

“phoneme_errors”: {

“substitutions”: [“/θ/ → /t/”],

“insertions”: [],

“deletions”: [“/k/”]

},

“phoneme_error_rate”: 28.6

}

4.5 User proficiency classification

User proficiency is classified into three levels using the computed ASS and PER values. The classification criteria are:

• Beginner: ASS < 60 or PER > 30%

• Intermediate: ASS in [60, 80] and PER in [15, 30%]

• Advanced: ASS > 80 and PER ≤ 15%

Sample Testing Outcome

{

“user_id”: “U0123,”

“proficiency_level”: “Intermediate,”

“ass”: 67.4,

“per”: 28.6

}

This classification guides the learning content based on each user’s fluency level.

4.6 Personalized YouTube recommendation

When a user is determined to be Beginner or Intermediate, the system automatically generates a content query string like “American English pronunciation course for Tamil speakers - beginner level” or words to that effect relative to the user’s native language and the preliminary proficiency for the user. This process is sent off to the search engine via a SerpAPI search, which then returns a list of relevant links to YouTube videos based on the query. The returned results are filtered on basis of the metadata - relevancy, video length, combined with view count and user ratings, to ensure the recommended content is relevant and popular. The recommended content will ensure the learner has relevant practice that is suitable and engaging to their accent level.

Sample Testing Outcome

{ “recommended_videos”: [

{

“title”: “American Accent Training for Tamil Speakers - Basics,”

“url”: “<ext-link xlink_href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyz123" ext-link-type="uri">https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyz123</ext-link>“, “views”: “124 k”

},

{

“title”: “Vowel Pronunciation Practice - Beginner,”

“url”: “<ext-link xlink_href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abc789" ext-link-type="uri">https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abc789</ext-link>“, “views”: “89 k”

}

]}

4.7 Analysis and visualization

To track user progress over time, the system logs the Accent Similarity Score (ASS) and Phoneme Error Rate (PER) over multiple sessions. Using this historical data, the visualizations are created using tools, like Matplotlib and Seaborn. The ASS and PER are shown using line plots over continuous sessions, which allows the user to track their improvement or decline over time. The visualizations will also show the most common phoneme errors, which provides feedback to the user and a focus for practice to improve their learning outcomes. Overall, these visualizations provide learners, teachers and educators with a simple, and interpretable overview of progress over time, and what may still need work.

4.8 Ethical considerations

All users start their interaction with the system through an informed consent form that specifies how audio data will be used, stored, and processed. Users may choose whether or not to permit their data to continue to be stored for long-term performance tracking. All recordings are set as a default, and recordings are deleted immediately after processing. There are no personal identity markers stored. The system design and data policies adhere to ethical standards for human-computer interaction and data privacy, and met ethical standards for research and frameworks for user protection.

1:PhonoMetric_Accent_Evaluation_And_Recommendation

Input

U_audio ← User’s recorded speech (WAV, 16 kHz, mono)

R_audio ← Reference native accent recording (same sentence)

User_L1 ← User’s native language (e.g., Tamil, Hindi)

OutputASS ← Accent Similarity Score (0–100)

PER ← Phoneme Error Rate (%)

proficiency ← User level: Beginner, Intermediate, or Advanced

videos ← Personalized YouTube video recommendations

BeginStep 1: PreprocessingEnsure U_audio and R_audio are WAV, 16 kHz, mono

Step 2: Compute accent similarity using ECAPA-TDNN embeddingse_u ← Extract_Embedding(ECAPA_TDNN, U_audio)

e_r ← Extract_Embedding(ECAPA_TDNN, R_audio)

S ← Cosine_Similarity(e_u, e_r)

ASS ← Scale_To_100(S) // (S + 1)*50 to map from [−1,1] to [0,100]

Step 3: Phoneme-Level Error Analysistranscript_u ← Transcribe(Whisper_ASR, U_audio)

alignment ← Force_Align(MFA, transcript_u, R_audio)

S_count ← Count_Substitutions(alignment)

I_count ← Count_Insertions(alignment)

D_count ← Count_Deletions(alignment)

T ← Total_Phonemes(R_audio)

PER ← ((S_count + I_count + D_count) / T) * 100

Step 4: User proficiency classificationIf ASS < 60 OR PER > 30:

proficiency ← “Beginner”

Else if 60 ≤ ASS ≤ 80 AND 15 < PER ≤ 30:

proficiency ← “Intermediate”

Else if ASS > 80 AND PER ≤ 15:

proficiency ← “Advanced”

Else:

proficiency ← “Unclassified”

Step 5: Personalized YouTube recommendationIf proficiency == “Beginner” OR proficiency == “Intermediate”:

query ← “American English pronunciation course for “+ User_L1 + “speakers - “+ proficiency + “level”

videos ← Search_YouTube_Videos(SerpAPI, query)

videos ← Filter_Videos_By_Metadata(videos, min_views = 1,000, max_length = 20 min)

Else:

videos ← None

Step 6: Visualization and loggingLog_User_Session(User_ID, ASS, PER, S_count, I_count, D_count, proficiency)

Visualize_Progress(ASS, PER, phoneme_errors = [S_count, I_count, D_count])

Step 7: Privacy and ethicsShow_Consent_Form()

Anonymize_And_Delete_Raw_Audio(U_audio, R_audio)

Return ASS, PER, proficiency, videos

End

5 Results

We tested the final version of the system on 30 users from different first language (L1) backgrounds: Tamil, Hindi, Malayalam, and Telugu. Each user spoke five English sentences that were phonetically rich, and we evaluated their accent using ECAPA-TDNN embeddings. We examined the users’ accent using the Automatic Speech Scoring (ASS) as well as error analysis work at the phoneme level using the Montreal Forced Aligner. The results showed that the ASS ranged from 42.6 to 91.3 with an overall mean ASS of 68.2 and the phoneme error rate (PER) ranged from 8.2 to 38.7% with a mean PER of 21.5%. The ASS and PER were used to classify the users into three levels of proficiency: Beginner, Intermediate and Advanced. For the 30 users, 10 were classified as beginners, 12 were classified as intermediate, and 8 were classified as advanced. In particular, users with higher levels of PER tend to have lower levels of ASS, which indicates a strong negative correlation between the phoneme level accuracy and closeness of accent (Figures 4, 5; Table 1).

Figure 4. User proficiency and accent evaluation metrics. Top-left: User count per proficiency level. Top-right: Distribution of Accent Similarity Scores (ASS). Bottom-left: Scatter plot of ASS vs. Phoneme Error Rate (PER). Bottom-right: Distribution of PER values.

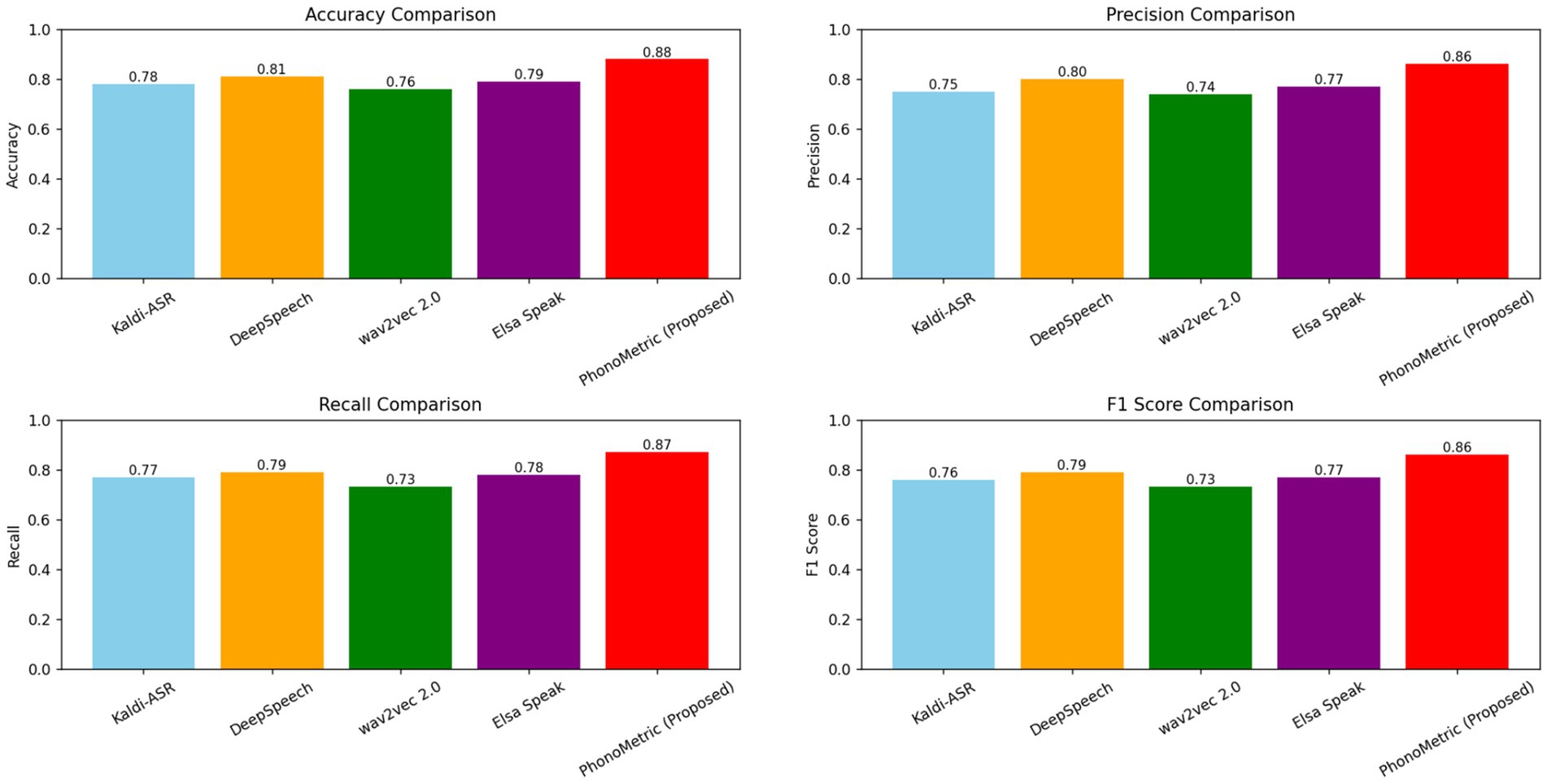

Figure 5. Comparison of model performance across four evaluation metrics — Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score — for five systems: Kaldi-ASR, Mozilla DeepSpeech, Facebook AI wav2vec 2.0, Elsa Speak (commercial app), and the proposed PhonoMetric system.

The system also automatically generated YouTube pronunciation courses based on the user’s native language and performance level. For instance, a Tamil-speaking Beginner was shown a curated video such as “American English Accent for Tamil Speakers - Beginner Practice.” All generated video links were relevant, had high viewer engagement, and matched the user’s proficiency level.

Additionally, the system tracked the frequency of specific phoneme errors. The most common substitutions included:

• /θ/ → /t/ (as in “think” pronounced as “tink”),

• /v/ → /w/ (as in “very” pronounced as “wery”),

• /dʒ/ → /z/ (as in “judge” pronounced as “juzz”).

Visualizations including histograms of ASS, PER distributions, and scatter plots were used to explore trends, and bar charts helped identify frequently mispronounced phonemes.

6 Discussion

The results show the capability of using speaker embeddings and phoneme-level measures to track and improve non-native speaker English pronunciation. The Accent Similarity Score (ASS) reasonably represented how close the user’s articulation was to the target accent. At the same time, the Phoneme Error Rate (PER) offered detailed information about the user’s phoneme production accuracy. The dual-metric system allows the system the ability to offer general and detailed feedback, which is important in individual language learning.

One of the interesting findings was the pattern in phoneme errors for users with similar L1 backgrounds. For instance, Tamil speakers often substituted /t/ for /θ/, while Hindi speakers made errors producing the phoneme /w/ and /v/. These errors are consistent with previous phonetic work, but notationally this system was able to detect and respond automatically and in real time. This level of flexibility allows the feedback provided by the system to act not just as an evaluator but more like a virtual pronunciation coach. In addition, the ECAPA-TDNN (Desplanques et al., 2020) defined as an architecture for speaker verification tasks, was very effective in determining accent distance. The model assessory as opposed to ear-based forced choice perception tests and human raters enables to free from their subjective biases allowing a single and consistent source of scalable feedback. When paired with the Montreal Forced Aligner, it becomes possible to align phonetic errors’ time frames directly to the user’s speech and be potentially expanded in future versions to delivery dynamic pronunciation visualizations. The YouTube-based recommendation engine is another additional quality feature as it directs users toward level- and quality-appropriate source traits. The dynamic filtering feature will also be filtering based on both proficiency and language background which ensures even the filtering of the suggestions will pedagogically aligned. For example, a user with Beginner credentials and with a high PER was directed to content that engaged with the value of meaning of vowels body and articulatory basics (Qian et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2023). While an aligned Advanced designated users received primarily exercises pertaining to prosody and stress. While other proven quality pronunciation supports certainly exist, they also offer limited personalization that could be left behind, other mainstream pronunciation approach to pronunciation improvement as a general skill and by definition offer little form of initial and longer-term adaptive support which would not be uncommon in broader pedagogy.

There are some limitations for this study, the current system is premised on relatively clean audio, whereas the realities of classroom or mobile learning can be noisy due to background noise and poor devices, which will distort the embeddings and confuse the model. The previous section above assumes a single target accent (American English), so the tool may not be generalizable globally, especially to learners in the UK, Australia, or Africa who may be training toward their own regional standards. Lastly, the lack of real-time corrective feedback (example. Waveform comparison or articulation animation) means learners must again rely on external content for improvement rather than receiving feedback through immediate help within the app.

7 Conclusion

In summary, this research presents a novel approach for accent assessment and pronunciation feedback, developed through contemporary deep learning. The integration of speaker embedding models such as the ECAPA-TDNN with phoneme-level alignment analysis enables a structured and scalable way to assess a user’s English accent based on a reference model. This two-component analysis, which considers the accent proximity and articulation accuracy of the user, provides a comprehensive accent proficiency profile and allows for a clear identification of areas for improvement.

The most valuable contribution from this work is the real-time, personalized feedback loop: the user receives (1) quantitative feedback (ASS and PER), (2) classification of their accent proficiency, and (3) timely the inclusion of context-specific YouTube videos related to their native language and current ability. The transformed end-to-end pipeline system converts passive assessment into active learning, a critical component or stage for non-native speakers to achieve a fluent or professional capacity for communicating in English. Besides personalized learner support, this system could also be utilized in classroom environments, training centers for call centers, or language assessment centers; its flexibility fits both individualized learning and completed instruction. As mentioned, we can also leverage this system to add support for more English dialects and aspects of real-time pronunciation correction. With proper efforts to make this a robust platform, it could become a complete digital pronunciation coach. These results demonstrate our approach’s efficacy in providing relevant feedback and personalized learning plans toward the development of intelligent, learner-driven pronunciation training applications. Future directions might consider multilingual target accents, offline functionality, gamification aspects to help bolster long-term retention, and perhaps adaptive learning by investigating reinforcement learning to allow the model to adjust in real-time as the learner improves, presenting increasingly challenging material. Our intention is to create a feedback loop from assessment to feedback to improved measurable learning to develop an intelligent language learning assistant.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. SA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. SL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the volunteers who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baevski, A., Zhou, Y., Mohamed, A., and Auli, M. (2020). Wav2vec 2.0: a framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 12449–12460. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2006.11477

Chermakani, G., Loganathan, S., Rajasekaran, E. S. P., Murugan Sujetha, V., and Vasanthakumar Stephesn, O. B. (2023). Language learning using muted or wordless videos-a creativity-based edutainment learning forum. E-Mentor 99, 22–30. doi: 10.15219/em99.1608

Desplanques, B., Thienpondt, J., and Demuynck, K. (2020). Ecapa-tdnn: emphasized channel attention, propagation and aggregation in tdnn based speaker verification. ArXiv 2020:7143. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.07143

Franco, H., Neumeyer, L., Kim, Y., and Ronen, O. (1997). Automatic pronunciation scoring for language instruction. 1997 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech, and signal processing, No. 2, pp. 1471–1474.

Kim, E., Jeon, J.-J., Seo, H., and Kim, H. (2022). Automatic pronunciation assessment using self-supervised speech representation learning. ArXiv 2022:3863. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2204.03863

McAuliffe, M., Socolof, M., Mihuc, S., Wagner, M., and Sonderegger, M. (2017). Montreal forced aligner: trainable text-speech alignment using kaldi. Interspeech, pp. 498–502.

Nagrani, A., Chung, J. S., and Zisserman, A. (2017). Voxceleb: a large-scale speaker identification dataset. ArXiv 2022:8612. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.08612

Pappagari, R., Wang, T., Villalba, J., Chen, N., and Dehak, N. (2020). X-vectors meet emotions: a study on dependencies between emotion and speaker recognition. ICASSP 2020–2020 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP), pp. 7169–7173.

Povey, D., Ghoshal, A., Boulianne, G., Burget, L., Glembek, O., Goel, N., et al. (2011). The Kaldi speech recognition toolkit. IEEE 2011 Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding, No. 1, pp. 1–5.

Qian, X., Meng, H., and Soong, F. (2016). A two-pass framework of mispronunciation detection and diagnosis for computer-aided pronunciation training. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 24, 1020–1028. doi: 10.1109/TASLP.2016.252678

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Xu, T., Brockman, G., McLeavey, C., and Sutskever, I. (2023). Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. International conference on machine learning, pp. 28492–28518.

Ravanelli, M., and Bengio, Y. (2018). Speaker recognition from raw waveform with sincnet. 2018 IEEE spoken language technology workshop (SLT), pp. 1021–1028.

Thorndahl, D., Abel, M., Albrecht, K., Rosenkranz, A., and Jonas, K. (2025). Bridging the digital disability divide: supporting digital participation of individuals with speech, language, and communication disorders as a task for speech-language pathology. Front. Commun. 10:1523083. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1523083

Wu, Z., Zhang, S., Cai, L., and Meng, H. M. (2006). Real-time synthesis of Chinese visual speech and facial expressions using MPEG-4 FAP features in a three-dimensional avatar. Interspeech, No. 4, pp. 1802–1805.

Wubet, Y. A., Balram, D., and Lian, K.-Y. (2023). Intra-native accent shared features for improving neural network-based accent classification and accent similarity evaluation. IEEE Access 11, 32176–32186. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3259901

Yuan, J., and Liberman, M. (2008). Speaker identification on the SCOTUS corpus. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123:3878. doi: 10.1121/1.2935783

Zeinali, H., Wang, S., Silnova, A., Matějka, P., and Plchot, O. (2019). But system description to voxceleb speaker recognition challenge 2019. ArXiv 2019:12592. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1910.12592

Keywords: accent evaluation, ECAPA-TDNN, language learning automation, pronunciation feedback, speaker embeddings, whisper ASR

Citation: Soundarraj R, Anantharajan S and Loganathan S (2026) PhonoMetric: a dual-metric engine for real-time English language accent evaluation and personalized speech training for Indian learners. Front. Commun. 10:1704484. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1704484

Edited by:

Dalel Kanzari, University of Sousse, TunisiaReviewed by:

José Ruiz Mas, University of Granada, SpainAlcina Sousa, University of Madeira, Portugal

Copyright © 2026 Soundarraj, Anantharajan and Loganathan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saranraj Loganathan, c2FyYW5peWNAZ21haWwuY29t

Rajkumaran Soundarraj

Rajkumaran Soundarraj Shenbagarajan Anantharajan

Shenbagarajan Anantharajan Saranraj Loganathan

Saranraj Loganathan