- 1Yantai Center of Coastal Zone Geological Survey, China Geological Survey, Yantai, China

- 2Observation and Research Station of Land-Sea Interaction Field in the Yellow River Estuary, Ministry of Natural Resources, Yantai, China

- 3Observation and Research Station of South Yellow Sea Earth Multi-sphere, Ministry of Natural Resources, Yantai, China

- 4Key Laboratory of Submarine Geosciences, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China

Aiming to address under-utilized geochemical proxies in the Bohai Sea (BS) due to analytical complexity and diagenetic uncertainty, this study present a 300-kyr high-resolution geochemical and microfossils records from core DZQ01, and identified elemental proxies such as Rb/Sr, Mg/Ca, and Ni/Co ratios to quantify paleoclimate, paleosalinity, and paleoredox variabilty. Six depositional units (DU6–DU1) are identified: DU6 (300–272 cal. ka B.P.) record cold-arid fluvial deposition, and persistent suboxic conditions; DU5 (272–205 cal. ka B.P.) captures an initial shift toward warmer, more humid conditions followed by renewed cooling and arid conditions, recorded in tidal-flat to shallow-marine facies; DU4 (205–90 cal. ka B.P.): is dominated by cold and arid conditions punctuated by a short-lived warming event; DU3 (90–57 cal. ka B.P.) exhibits elevated temperatures and sea levels, fully marine conditions marked by abundant benthic foraminifera and ostracods; DU2 (57–14 cal. ka B.P.) documents cold-arid conditions, incised-valley fills, and diminished biogenic activity; and DU1 (14 cal. ka B.P. to present) reflects warm-humid climate, widespread euryhaline assemblages, and high biological productivity in intertidal to shallow-marine setting. Glacial-interglacial cycles in BS are driven by orbital forcing, greenhouse gases, and ocean-atmosphere feedbacks, with glacials cooling/expanded ice sheets and interglacials warming/reconfigured circulation.

1 Introduction

Coastal zones constitute the primary interface between terrestrial and marine systems, exerting a pivotal role control on the sedimentary response to climate change and sea-level fluctuations (Weymer et al., 2022; Barceló et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2025). The Bohai Sea (BS) has undergone sustained Cenozoic tectonic subsidence that generated >200 m of stacked, high-resolution sedimentary strata (Hu et al., 2001; Tian et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2024a). These strata archive continuous, high-fidelity records of paleoclimate, paleosalinity, and relative sea-level change, rendering the BS an exceptional natural laboratory for deciphering coastal-system evolution under variable boundary conditions (Alqahtani et al., 2015; Bentley et al., 2016; McHugh et al., 2018; Mestdagh et al., 2019; Peeters et al., 2019).

Grain-size (Yi et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2017; Lyu et al., 2020), microfossil (Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019), and palynological proxies (Chen et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019) have underpinned Quaternary paleoclimate reconstructions in the BS. Grain-size covary with monsoon intensity: fine fractions track the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM), whereas medium fractions record the East Asian Winter Monsoon (EAWM) (Qiao et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2024a). Microfossils assemblages quantify past water-mass temperature and salinity variability (Saraswat et al., 2017), and pollen spectra independently reconstruct temperature and humidity trajectories (Chevalier et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Transgressions coincide with interglacial sea-level highstand, whereas regressions typify glacials (Song et al., 2018). Core BH08 exhibits systematic fining-upward trends during Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 1 and 5 that coincide with δ18O-defined interstadials in Arctic ice cores (Stuiver et al., 1995). Grain-size and color-reflectance analyses of the same core further reveal sustained late-Pliocene–Quaternary paleoclimatic and paleoredox variability, with transgressions driven by eustatic highstands superimposed on long-term tectonic subsidence. Enhanced EASM intensity during interglacials fostered sable warm-humid conditions across eastern China, promoting widespread forest cover (Yao et al., 2012). Pollen and spore fossils from core TJC-1 demonstrate that MIS 5, 3, and 1 correspond to warm, mixed-forests interval, whereas MIS 4 and 2 are characterized by cold, herbaceous vegetation and depressed relative sea level. Geochemical proxies remain under-utilised in the BS because analytical complexity and potential diagenetic alteration introduce uncertainty (Chevalier et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2023).

To enhanced fidelity, this study integrates high-resolution elemental geochemistry with microfossils records from borehole DZQ01 in the western BS, and benchmark these results against global sea levels and climate archives aimed at: (1) identifying robust elemental proxies for paleoclimate, paleosalinity, and paleoredox variability; and (2) integrating these data with microfossil assemblages, global δ18O records and sea-level curve to reconstruct BS evolution over the last 300 kyr. This multi-proxy synthesis will refine understanding of coastal-system responses to orbital and eustatic forcing.

2 Regional setting

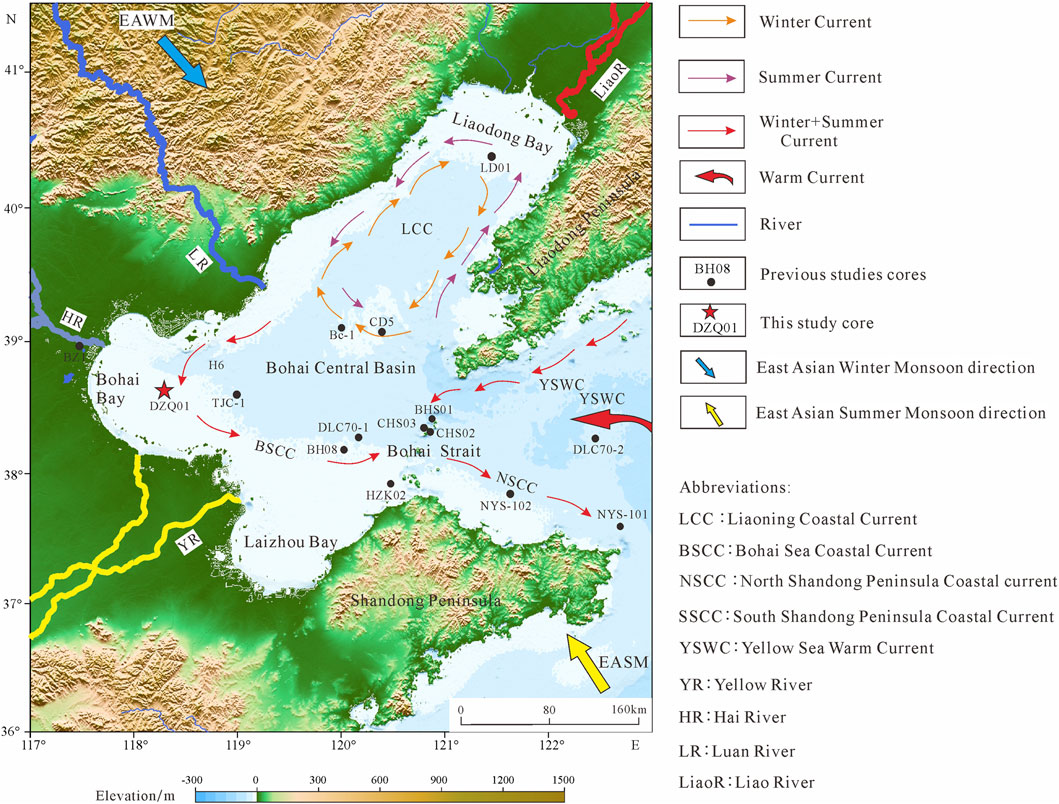

The BS is a semi-enclosed marginal continental shelf on the East China Sea (37°07′–41°00′N, 117°35′–121°10′E; ∼78,000 km2), comprises five morphological domains: Liaodong Bay, Bohai Bay, Laizhou Bay, the Bohai Strait, and the Bohai Central Basin (Figure 1). Depths are generally shallow (mean 18 m, maximum <30 m), yet tidal scouring along the Laotieshan Channel deepens the strait locally to ∼80 m (Qin et al., 1989).

Figure 1. Present schematic maps of bathymetry and regional circulation patterns in the BS (modified from (Yao et al., 2017). Red solid star denote sediment cores examined in this study, whereas black solid circles indicate previously reported cores from the BS and adjacent areas. Yellow line is the Yellow River, grey blue line is the Hai River, Bule line is the Luan River, Red line is the Liao River.

The study region receives terrigenous sediments predominantly from four major rivers: the Yellow River (YR), Hai River (HR), Luan River (LR), and Liao River (LiaoR) (Figure 1). Among these, the YR is the largest and constitutes the primary sediment source. Ranking second in China in terms of sediment load, the YR annually discharges enormous volumes of silt and sand eastward into the BS (Milliman et al., 1987) and thereby forms a critical component of the source-to-sink sedimentary system in the basin (Shi et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2020). Circulation in the BS is governed mainly by the Yellow Sea Warm Current (YSWC) and its coastal derivatives, namely, the Liaonan Coastal Current (LCC) and the Bohai Sea Coastal Current (BSCC) (Guan, 1994; Fang et al., 2000). Saline water from the North Yellow Sea (NYS) intrudes through the Bohai Strait. In winter, the YSWC gives rise to clockwise-flowing LCC; in summer, the system reconfigures into the anticlockwise-flowing BSCC (Figure 1; Guan (1994)).

The Bohai Basin is underlain predominantly by Archean-Proterozoic crystalline metamorphic rocks and Lower Paleozoic marine carbonates. Subsidence commenced in the early Cenozoic and accommodated a thick sedimentary succession composed of Paleogene, Neogene, and Quaternary strata that are dominated by terrigenous clastic rocks (Hu et al., 2001). Situated within the East Asian monsoon domain, the study area experiences warm, humid summers and cool, dry winters (Zhang and Derbyshire, 1991). Mean annual precipitation is ∼700 mm, and the mean annual temperature is 12.6 °C. July averages 25.5 °C, whereas January averages 2.3 °C. Approximately 70% of the annual rainfall occurs during July and August.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Sample collection

A 203.05-m core (DQZ01) was recovered from the western BS offshore Tangshan by the Yantai Center of Coastal Zone Geological Survey (YCGS) in July 2022. The drilling site was located at Caofeidian (38.76565°N, 118.262905°E; Figure 1), in water 23.1 m depth. Drilling operations were conducted from the coastal research vessel Haiyang 6, reaching a total depth of 203.15 m and yielding 187.63 m of sediment, corresponding to a recovery rate of 92.36%. The core was sectioned into 2-cm intervals for subsequent analysis. Microfossils identification was performed at 30-cm intervals, generating 255 samples, whereas geochemical analyses were conducted at 60-cm intervals, resulting in 147 samples.

3.2 Microfossils identification

Foraminifera and ostracod samples were initially oven-dried at 60 °C. Approximately 25 g of dried sediment was soaked in distilled water for 24 h to ensure complete disaggregation. The slurry was washed through a 63 μm brass sieve until the eluate was clear. The >63 μm residue was oven-dried at 60 °C, weighed, and transferred for taxonomic analysis. Based on fossil abundance, an aliquot was obtained by microsplitting prior to counting. Species were identified and enumerated under a compound microscope (Carl Zeiss Axio Scope A1, Germany); a minimum of 200 individuals were counted, or the entire aliquot when <200 specimens were present. Taxonomic assignments followed (Wang et al., 2023).

3.3 Age dating

The cores spans ∼110 m of strata since ∼300ka (MIS 8) to present day, as determined by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating.

AMS 14C dating was conducted at the Institute of Hydrogeology and Environmental Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (CAGS). Identified foraminiferal or molluscan shells were processed via the zinc/iron (Zn/Fe) flame-sealed tube method and analyzed using an accelerator mass spectrometer (NEC 1.5SDH-1, National Electrostatics Corporation, United States). For samples from the western BS, a regional marine reservoir correction of ΔR = −334 ± 50 years was applied (Southon et al., 2002), and the resulting marine reservoir ages were calibrated using CALIB 7.0.2 (Reimer et al., 2013) to construct a high-resolution chronological framework.

OSL dating was performed at the Laboratory Center of the Qingdao Institute of Marine Geology. In the field, homogeneous silt horizons were selected as the target horizons; samples were collected using double-light-tight polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tubes to prevent light exposure. In the laboratory, organic matter was removed using 5 mL of 30% H2O2, carbonates were dissolved with 3 mL of 10% HCl, and feldspars were removed with 40% HF. Subsequently, the samples were repeatedly rinsed to neutrality and dried; pure quartz grains (fine-grained: 4–11 μm or coarse-grained: 90–125 μm) were then extracted for equivalent dose (De) determination. OSL ages were determined using a luminescence measuring instrument (LEXSYG Research, Freiberg Instruments, Germany) and a Risø TL/OSL-DA-20 reader; analytical uncertainties were constrained within ±10%.

3.4 Major and trace element concentration measurement

All geochemical determinations were conducted at the YCGS Testing Center. Samples were oven-dried at 60 °C, powdered to<200 mesh, and subjected to a multi-step acid digestion. Digestion began with 4 mL HNO3 and 1 mL HClO4; after initial reaction, 4 mL HF and 1 mL HClO4 were added. Digestion was completed by the addition of 10 mL HNO3 to achieve total sample dissolution. Major-element abundances were determined by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (Axios; PANalytical, Almelo, Netherlands), whereas trace-element concentrations were measured by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, iCAP RQ; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States).

4 Results

4.1 Chronology

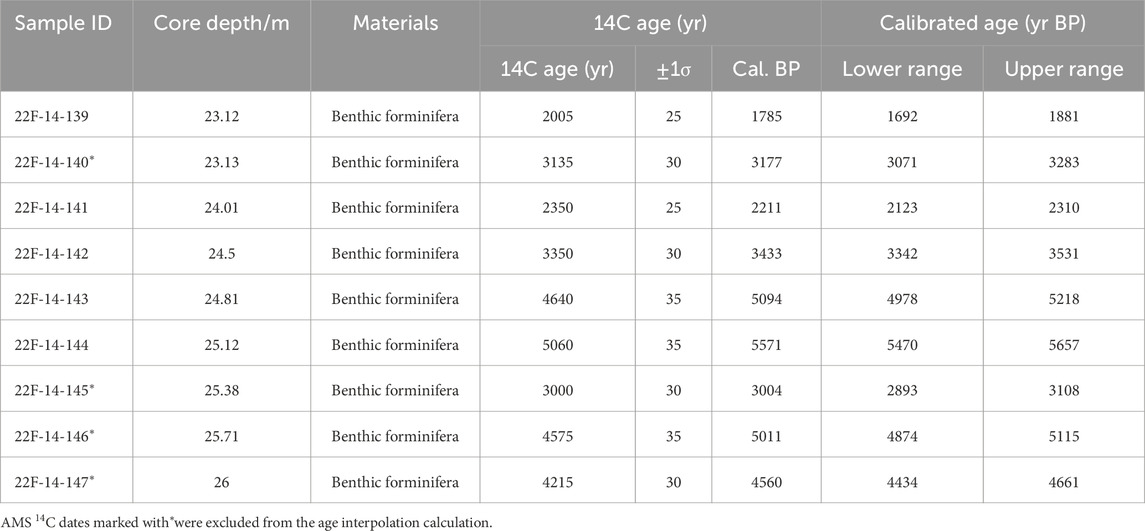

The chronostratigraphic framework of core DZQ01 established from AMS 14C and OSL dates (Table 1, 2), applying piecewise linear interpolation between the dated tie points. The calculated average linear sedimentation rates (LSRs) ranged from 28 to 71 cm/ka.

4.2 Lithology facies and microfossils assemblages

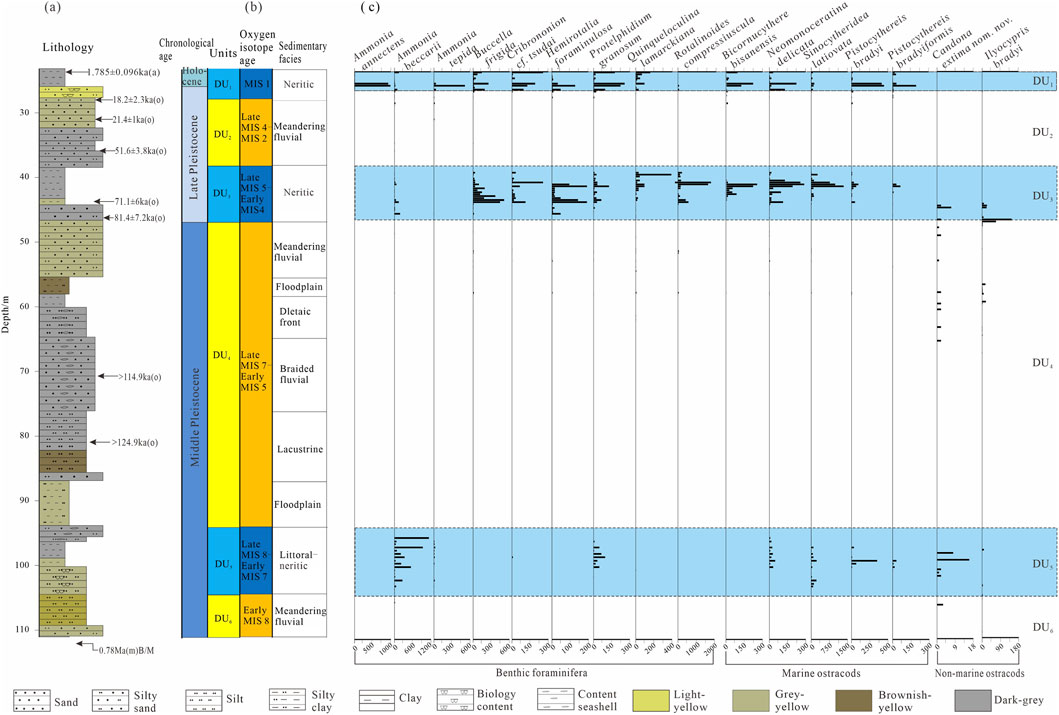

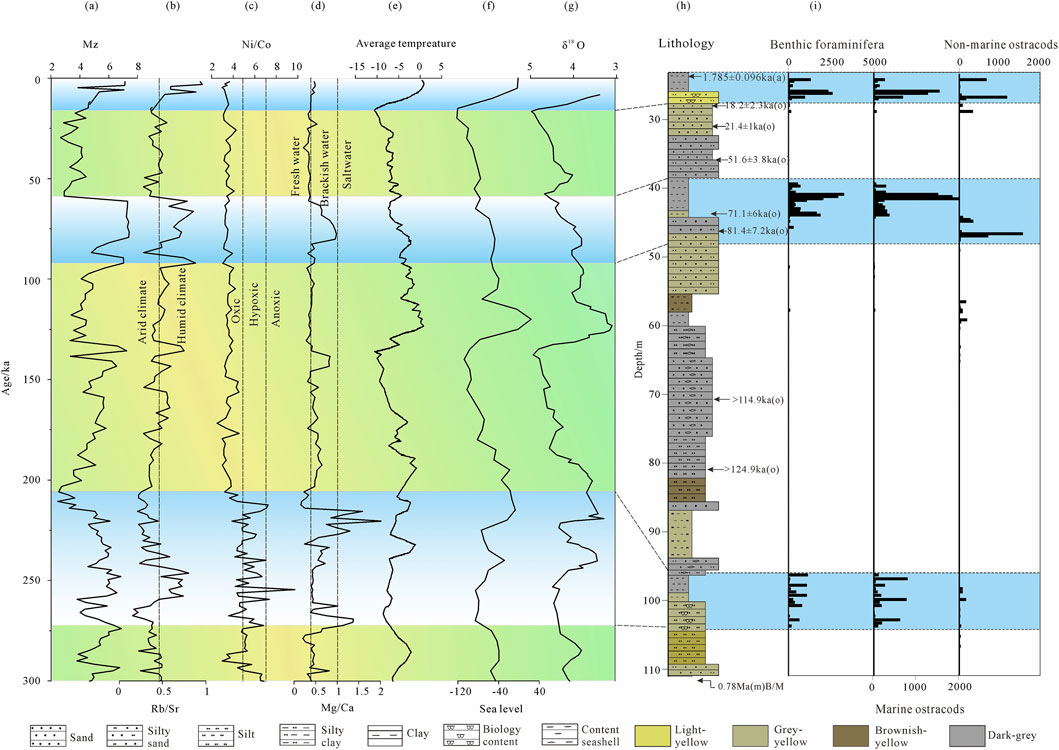

The core has been subdivided into six Depositional Units (DUs) (Figure 2B), designated DU6–DU1 from bottom to top. These units are defined by microfossils assemblages and sedimentary structures, which span the interval from the Middle Pleistocene to the present.

Figure 2. Down-core variations in sedimentological properites and microfossil assemblages of core DZQ01. (a) Lithological characteristics and chronological framework (age dating: “a” = AMS14C dating, “o” = OSL dating, “m” = paleomagnetic dating); (b) Stratigraphic age, depositional units, marine isotope stage (MIS), and sedimentary facies; (c) Microfossil aboundance and assemblages.

DU6 (104.4–111 m, Early MIS 8) is dominated by brown silty fine sand and yellow-brown sand (Figure 2a). Microfossil assemblages within this unit are sparse and exclusively non-marine, consisting of scattered, late-stage occurrences of ostracods Candona extima nom. nov. (Figure 2c). Collectively, these characteristics indicate a non-marine fluvial depositional environment.

DU5 (94–104.4 m, Late MIS 8– Early MIS 7), the lower part of DU5 comprises densely interbedded greyish-yellow silt and silty clay, displaying undulating lamination, weak bioturbation, and abundant ferric oxide mottles. The upper part is composed of dark-grey silty fine sand with millimetre-scale shell fragments, weak bioturbation, and common ferric oxide mottles (Figure 2a). Benthic foraminiferal assemblages are dominated by Ammonia beccarii and Protelphidium granosum accompanied by brackish-water ostracod (Neomonoceratina delicata, Sinocytheridea latiovata, Pistocythereis bradyi, and Pistocythereis bradyiformis). Sparse occurrences of non-marine ostracod (Candona extima nom. nov. and Ilyocypris bradyi) (Figure 2c). DU5 is interpreted as a littoral-neritic facies.

DU4 (44.4–94 m, Late MIS 7– Early MIS 5) grades upward from greyish-yellow silty clay at the base to gray fine sand at the top. Cross-bedding, moderate bioturbation, and iron-stained silty laminations are ubiquitous throughout (Figure 2a). The lower part contains abundant non-marine ostracod, including Candona extima nom. nov. and Ilyocypris bradyi). In contrast, microfossil preservation is poor in the upper interval of DU4 (51–58 m), where scattered benthic foraminifera (Buccella frigida, Hemirotalia foraminulosa, Quinqueloculina lamarckiana, and Rotalinoides compressiuscula) and marine ostracod (Neomonoceratina delicata, Sinocytheridea latiovata, and Pistocythereis bradyi) are present (Figure 2c). DU4 is interpreted as a braided-meandering fluvial system, consisting of channel, floodplain, lacustrine, and deltaic-front facies, DU3 (38.1–44.4 m, Late MIS 5– Early MIS 4), the lower interval of DU3 consists of greyish-yellow clayey silt with silty lenses and millimetre-scale laminations, intense bioturbation, localized muddy occurrences, and sparse carbonaceous flecks. The upper interval comprises of dark-grey silty clay with rich in silty lenses and laminations, moderate bioturbation, common carbonaceous specks, and scattered shell fragments (Figure 2a). Microfossil assemblages are diverse and well-preserved. Benthic foraminifera (Buccella frigida, Cribrononion cf. Tsudai, Hemirotalia foraminulosa, Protelphidium granosum, Quinqueloculina lamarckiana, and Rotalinoides compressiuscula), abundant marine ostracod (Bicornucythere bisanensis, Neomonoceratina delicata, and Sinocytheridea latiovata), together with accessory Pistocythereis bradyi and Pistocythereis bradyiformis, and sparse non-marine ostracods (Candona extima nom. nov. and Ilyocypris bradyi) restricted to the basal interval (Figure 2c). DU3 is interpreted as a neritic facies.

DU2 (26.74–38.1 m, Late MIS 4–MIS 2) is dominated by grey to grey-brown silt and sand with abundant biogenic structures, including worm burrows (Figure 2a). Microfossil assemblages rare, only between 26 and 28 m core depth do sparse benthic foraminifera (Ammonia beccarii, Ammonia tepida, and Hemirotalia foraminulosa) and scattered marine ostracods (Bicornucythere bisanensis and Pistocythereis bradyi) occur (Figure 2c). DU2 is interpreted as a meandering fluvial facies dominated by channel-fill sands.

DU1 (23.1–26.74 m, MIS 1) comprises a lower unit of light-yellow biogenic silty fine sand with weak bioturbation, overlain by dark-grey, shell-rich silty clay with scattered black carbonaceous specks and moderate bioturbation (Figure 2a). Benthic foraminiferal assemblages are dominated by Ammonia annectens, Ammonia tepida, Buccella frigida, Cribrononion cf. tsudai, Hemirotalia foraminulosa, Protelphidium granosum, and Quinqueloculina lamarckiana, euryhaline marine ostracods (Bicornucythere bisanensis, Neomonoceratina delicata, Pistocythereis bradyi, and Pistocythereis bradyiformis (Figure 2c). DU1 is interpreted as a netitic facies.

4.3 Major and trace element concentrations

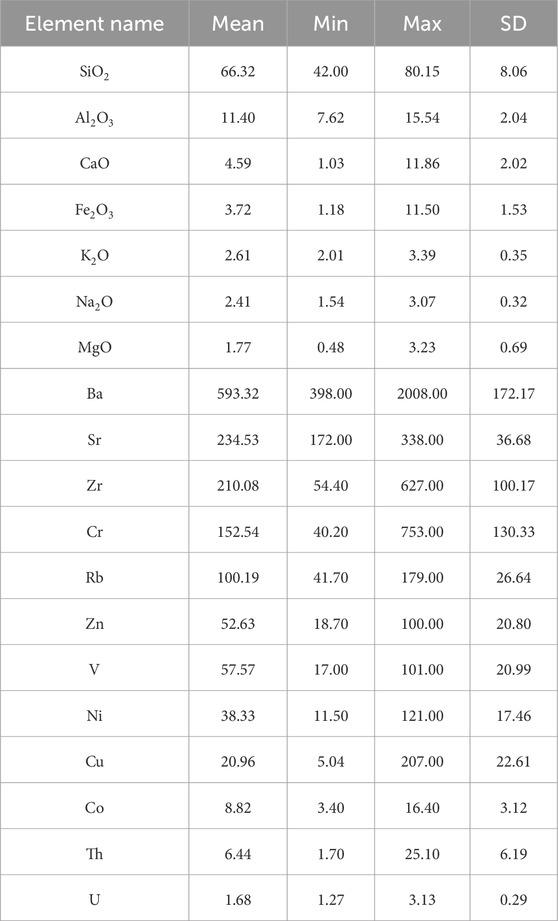

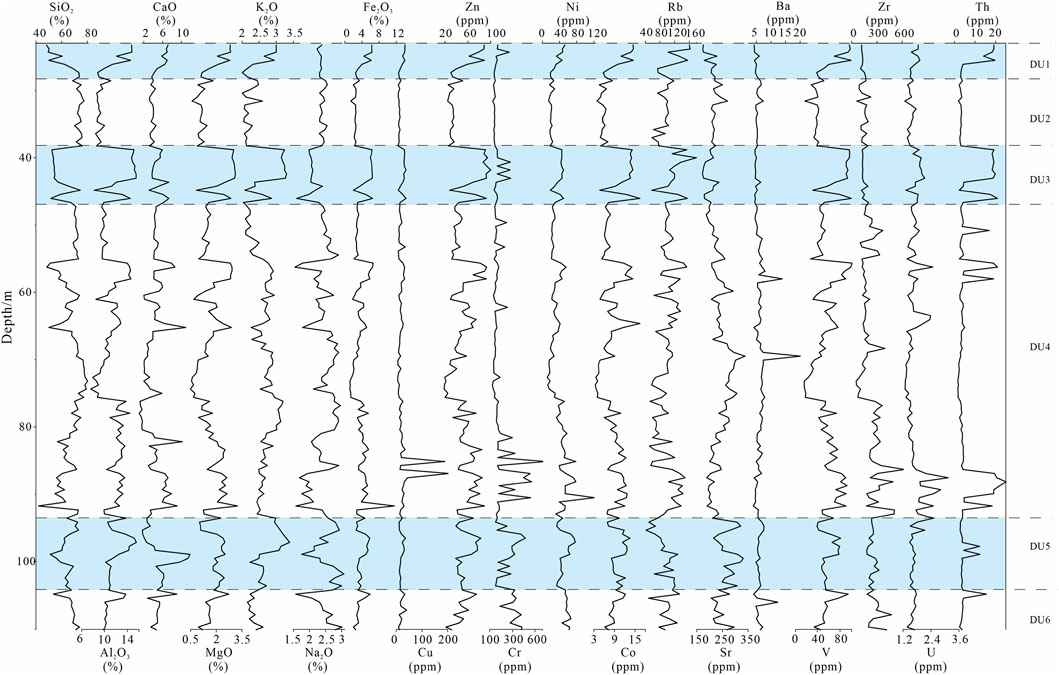

Table 3 and Figure 3 present the concentrations of major elements (as oxide weight percentages) and trace elements (as individual elemental concentrations). SiO2 is the most abundant oxide, with concentrations ranging from 42.00 to 80.15 wt%, followed by Al2O3 (7.62–15.54 wt%). Among the trace elements, Ba, Sr, Zr, Cr, and Rb exhibit the highest mean concentrations.

Table 3. Mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation (SD) of geochemical elements concentrations in drill-core DZQ01 for the interval spanning the Middle Pleistocene to present Major elements (SiO2– MgO) are reported in wt%, and trace elements (Ba–U) in ppm (μg g−1).

Figure 3. Down-core variations in major (wt%) and trace (ppm) elements of core DZQ01. The elements presented left to right are as follows: major elements (SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, MgO, K2O, Na2O, Fe2O3) and trace elements (Cu, Zn, Cr, Ni, Co, Rb, Sr, Ba, V, Zr, U, Th).

4.4 Paleoenvironmental proxies

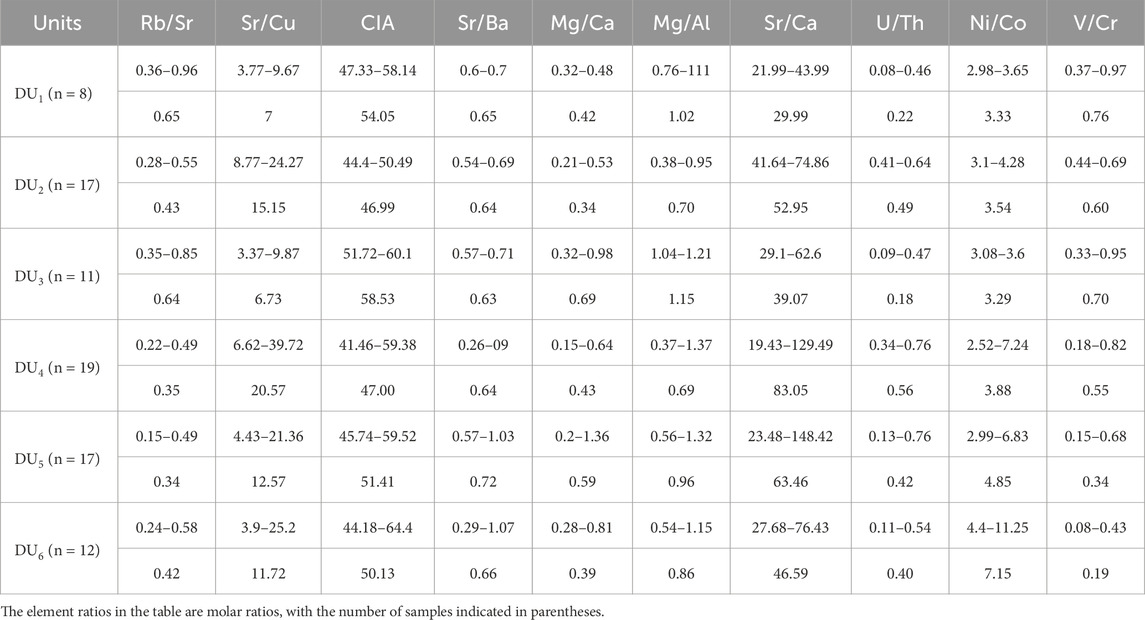

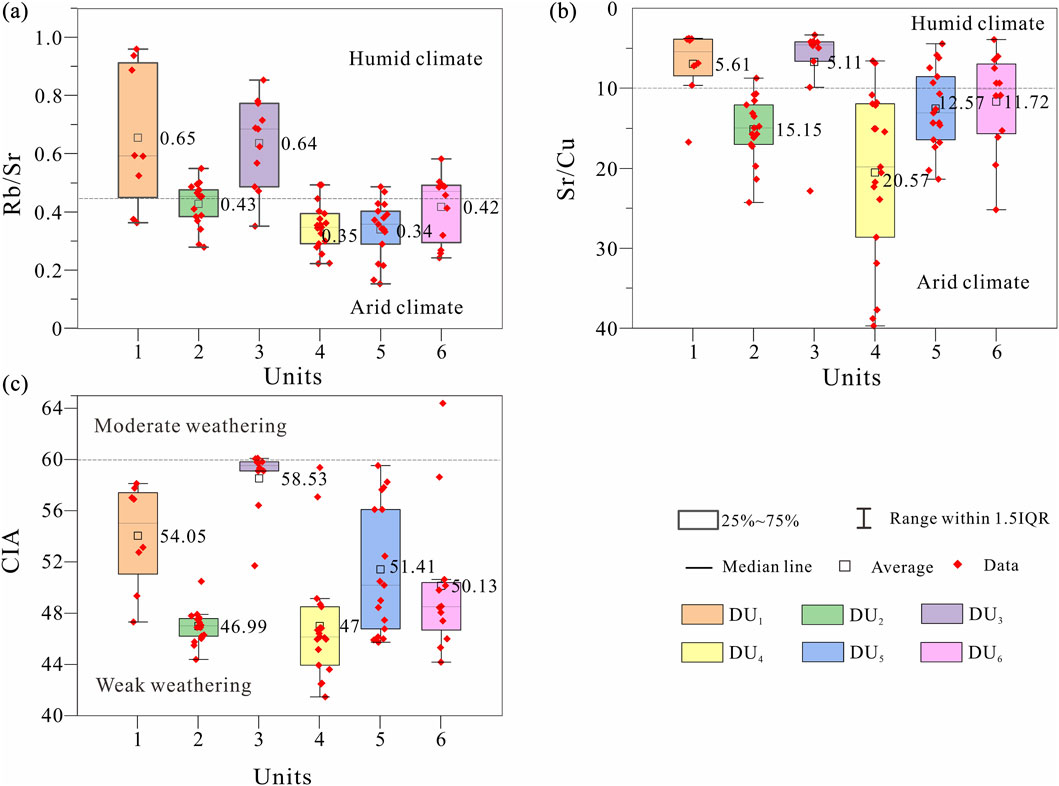

The Rb/Sr and Sr/Cu ratios and the Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA) are established proxies for paleoclimate reconstruction. Drill-core DZQ01 yield maximum mean Rb/Sr values in DU1 (0.65) and DU3 (0.64), intermediate values in DU2 (0.43) and DU6 (0.42), and minima in DU4 (0.35) and DU5 (0.34). Mean Sr/Cu ratio is lowest in DU1 (5.61) and DU3 (5.11), increases sequentially to DU6 (11.72), DU5 (12.57), and DU2 (15.15), and peaks in DU4 (20.57). Mean CIA values are highest in DU3 (58.53) and DU1 (54.05), intermediate in DU5 (51.41) and DU6 (50.13), and lowest in DU4 (47) (Table 4).

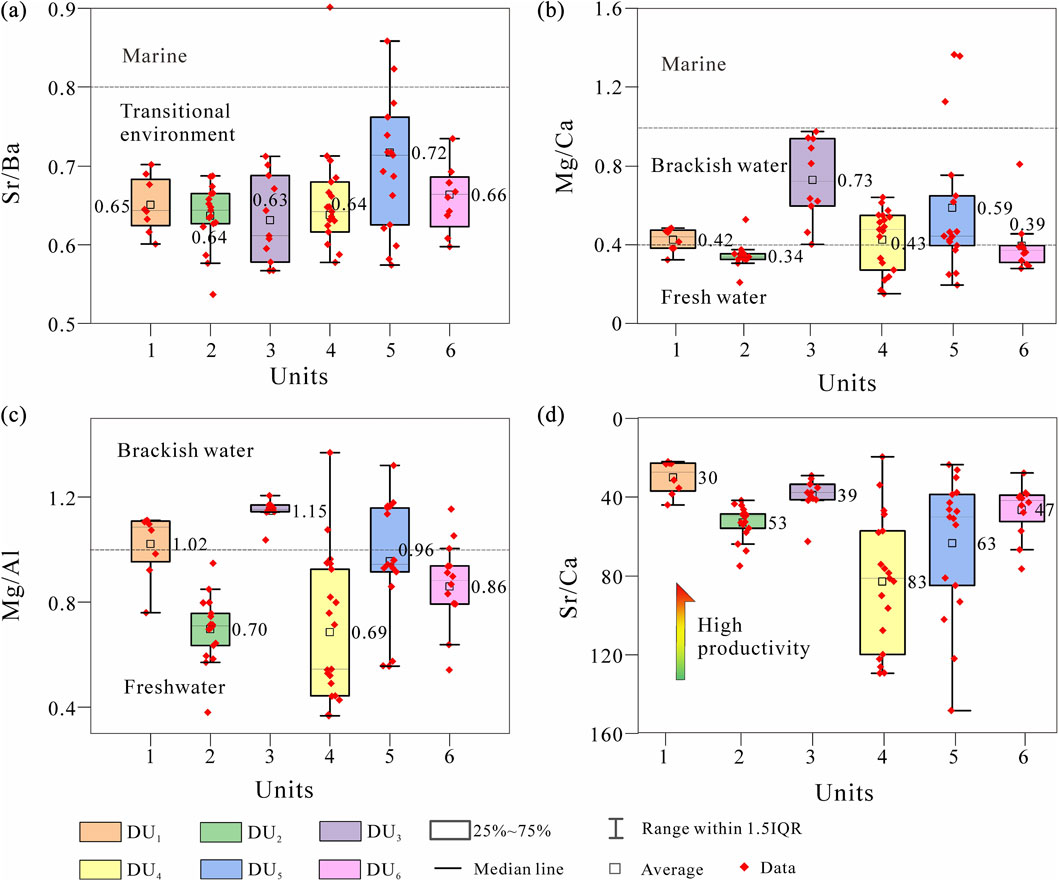

The Sr/Ba, Mg/Ca, Mg/Al, and Sr/Ca ratios are widely employed as proxies for paleosalinity variability. In dirll-core DZQ01, mean Sr/Ba peaks in DU5 (0.72) and is similar across the remaining units: DU6 (0.66), DU1 (0.65), DU2 (0.64), DU3 (0.63), and DU4 (0.64). Mean Mg/Ca reaches maxima in DU3 (0.69) and DU5 (0.59), and minima in DU4 (0.43), DU1 (0.42), DU6 (0.39), and DU2 (0.34). Mean Mg/Al displays marked variability, peaking in DU3 (1.15), DU1 (1.02), and DU5 (0.96), and decreasing toward DU6 (0.86), DU2 (0.7), and DU4 (0.69). Mean Sr/Ca is lowest in DU1 (29.99) and DU3 (39.07), increases through DU6 (46.59), DU2 (52.95), and DU5 (63.46), and culminates in DU4 (83.05) (Table 4).

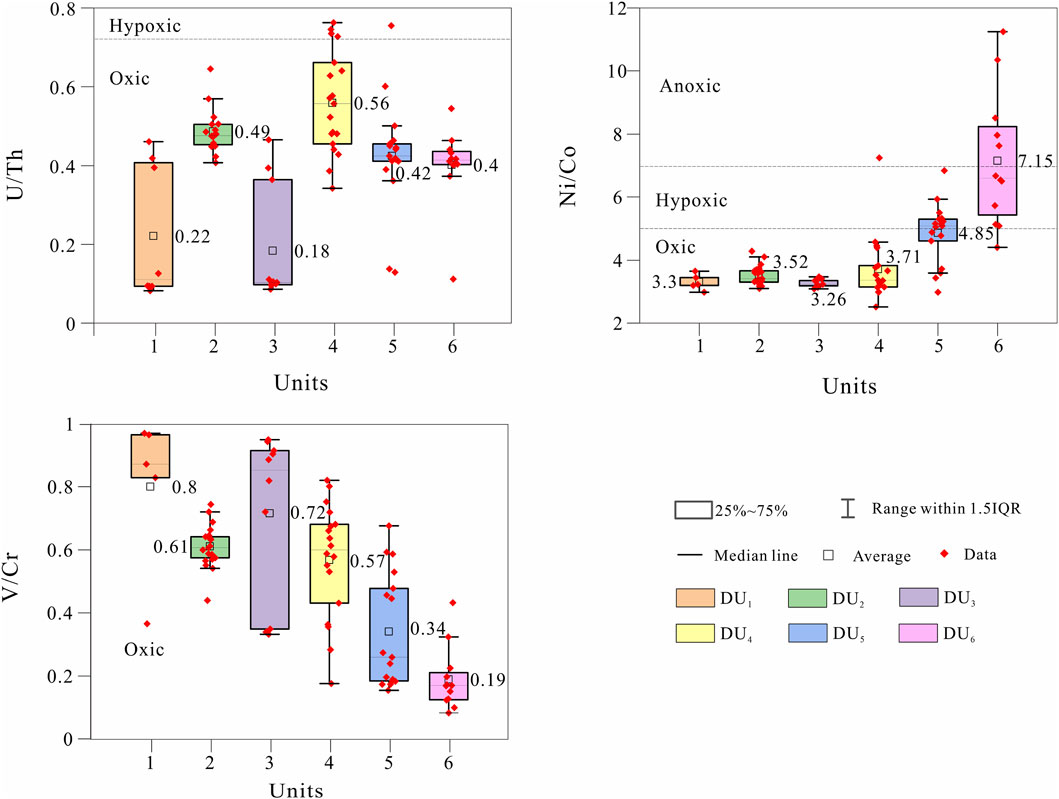

The U/Th, Ni/Co, and V/Cr ratios are established proxies for reconstructing paleoredox conditions in sedimentary systems. Mean U/Th is lowest in DU3 (0.18) and DU1 (0.22), increases progressively through DU6 (0.4), DU5 (0.42), DU2 (0.49), and peaks in DU4 (0.56). Mean Ni/Co increases from DU3 (3.29), DU1 (3.33), DU2 (3.54), and DU4 (3.88) to DU5 (4.85) and DU6 (7.15). Mean V/Cr increases systematically from DU6 (0.19) through DU5 (0.34), DU4 (0.55), DU2 (0.6), DU3 (0.7), to a maximum in DU1 (0.76) (Table 4).

5 Discussion

5.1 Paleoclimate

Sedimentary deposits under humid-climate are enriched in Fe, Mg, Cu, Rb, Co, and Ba, whereas arid-climate deposits exhibit elevated Sr, Na, Ca, Mg, and Zn contents (Fu et al., 2018; Stankevica et al., 2020). These elemental patterns constitute reliable proxies for paleoclimate reconstruction.

The Rb/Sr ratio is widely employed to infer climate conditions and environmental evolution over geological time scales. Rb preferentially accumulates in clay-rich, fine-grained sediments under warm-humid climates, whereas Sr is hosted chiefly by Ca-bearing phase (e.g., calcite, dolomite) and becomes enriched under cold-arid conditions (Gallet et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2000). Consequently, warm-humid settings yield elevated Rb/Sr ratio owing to Rb enrichment and Sr leaching (Dasch, 1969; Jeong et al., 2006; Du et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2024a). Xu et al. (2018) used Rb/Sr ratios of sediments from core MZ05 in the Min-Zhe muddy area of the East China Sea to reconstruct variations in the intensity of the EASM over the past 2900 years, and identified a negative correlation between the EAWM and EASM on a centennial scale during the Late Holocene. Fan et al. (2022) utilized the Rb/Sr ratio as an indicator of chemical weathering intensity in the source area of deep-sea sediments from Site U1516 of the IODP expedition 369. In monsoon-influenced Central and Eastern China, an Rb/Sr threshold of 0.45 distinguishes climate regimes: values <0.45 denote cold-dry conditions, whereas values >0.45 signify warm-humid climates (Chen, 1999). Rb/Sr ratio thus identify DU1 and DU3 as warm-humid intervals, DU2 and DU6 as transitional, and DU4 and DU5 as cold-arid intervals (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Box-plots of paleoclimate-related geochemical proxies in Core DZQ01: (a) Rb/Sr ratio, (b) Sr/Cu ratio, (c) Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA).

The Sr/Cu ratio is a sensitive proxy for paleoclimate variability (Yan et al., 2021). Under warm-humid climates, intensified chemical weathering mobilies Sr into solution, lowering the Sr/Cu ratio. Low Sr/Cu ratios (<10) denote warm-humid conditions, whereas high ratios (>10) signify cold-arid climates (Tribovillard et al., 2006; Brookfield et al., 2020). Drill-core DZQ01 yields Sr/Cu < 10 in DU1 and DU3, consistent with humid conditions and values >10 in DU6, DU5, DU2, and DU4, reflecting progressive aridification (Figure 4b). Sr/Cu-based temperature trends corroborate the Rb/Sr record.

The CIA indirectly constrains paleoclimatic and weathering intensity via the depletion of mobile elements (Ca, Na, K) and enrichment of stable elements (Al, Ti). CIA values of 80–100 signify intense weathering under warm-humid conditions. 60–80 moderate weathering, and 40–60 weak weathering under cold-arid regimes (Fedo et al., 1995). All six DUs exhibit CIA <60, implying cold-dry conditions (Figure 4c) (Neisbitt and Yong, 1982). The discrepancy with Rb/Sr and Sr/Cu interpretations likely reflects grain-size control on chemical weathering.

Interpretation of Rb/Sr, Sr/Cu ratios, and CIA as paleoclimate proxies requires explicit consideration of sediment grain-size effects and source rock effects, as grain-size variability can bias their geochemical signatures and confound paleoclimatic reconstruction: Rb preferentially resides in clay minerals and fine fractions, whereas Sr is enriched in coarser feldspar and calcite grains; during weathering and transport, Rb accumulates in fine fractions and Sr is preferentially leached—leading Rb/Sr to increase with hydrodynamic sorting rather than solely climatic forcing. For Sr/Cu, Cu is enriched in organic matter and clays, and arid climates elevate the ratio by concentrating Sr in coarse fractions (while humid climates lower it via Sr leaching and Cu enrichment in fines); neglecting grain size may erroneously attribute Sr/Cu fluctuations to climate, as elevated ratios could reflect coarser sediment supply rather than aridity. CIA is also grain-size dependent: fine fractions undergo more intense weathering, increasing Al and K contents and thus CIA values, whereas coarser, less weathered particles yield lower CIA—meaning ignoring grain-size effects may misascribe high CIA in fine sediments to particle size rather than climate-modulated weathering intensity.

In marine geology, Ti2O3/Al2O3 ratio is a well-recognized proxy for tracking terrestrial clastic input: Ti is predominantly derived from detrital minerals (e.g., ilmenite, rutile) with strong resistance to chemical weathering, while Al is mainly associated with clay minerals (also terrigenous). Thus, Ti2O3/Al2O3 effectively reflects the relative contribution and provenance stability of terrestrial clastic materials.

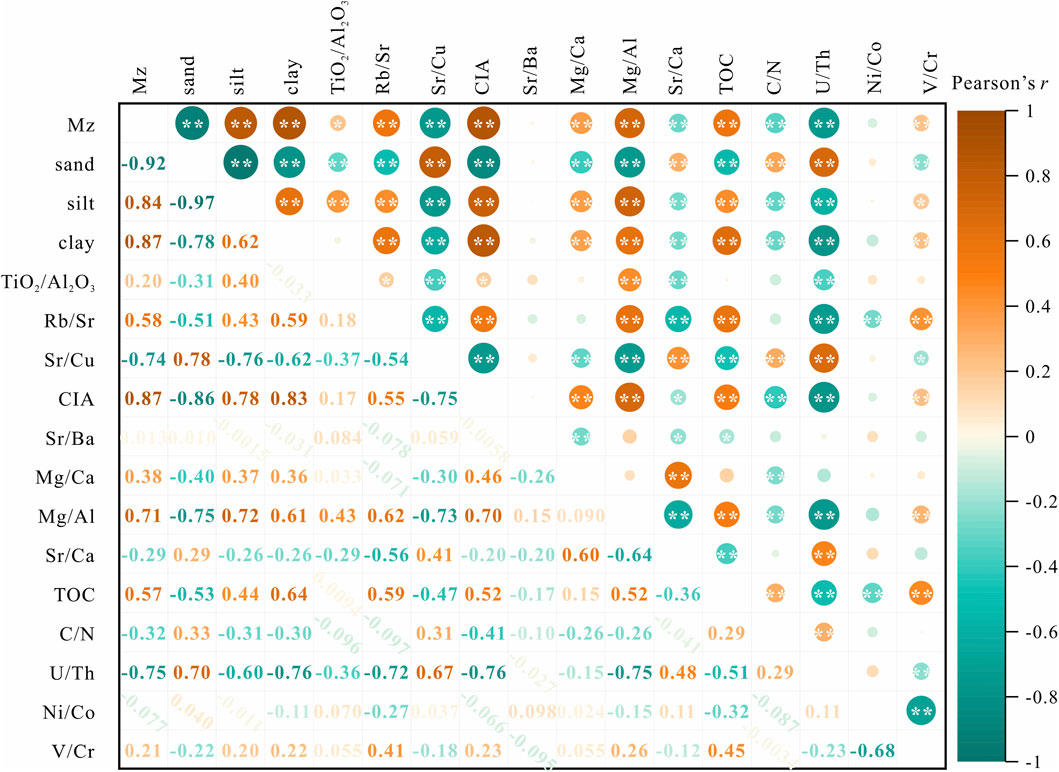

First, correlation analyses between the Ti2O3/Al2O3 ratio and three key proxies—Rb/Sr, Sr/Cu, and the CIA—yielded weak correlations, with r-values of 0.18, −0.37and 0.17, respectively (Figure 5). This indicates no direct evidence that these paleoclimate-related proxies are disturbed by variability in terrigenous source rock composition. Furthermore, Geochemical proxies exhibit differential sensitivity to grain size (Tabor and Myers, 2015). CIA display a strong positive correlation with Mz (r = 0.89, Figure 5). High CIA values correspond to fine-grained silt (r = 0.81) and clay (r = 0.85); thus elevated CIA chiefly records the weathering signature of fine-grained fractions. Conversely, Sr/Cu is inversely correlated with Mz (r = −0.81) and positively correlated with sand (r = 0.84, Figure 5). Hense, Sr/Cu serves as a proxy for coarser-grained, arid depositional setting. Rb/Sr exhibits a modest correlation with Mz (r = 0.47, Figure 5), indicating limited grain-size dependence. Because Rb/Sr is enriched in fine-grained fractions, it more faithfully records climate-driven compositional changes. Consequently, Rb/Sr is the most reliable independent paleoclimate indicator examined.

Figure 5. Pearson’s correlation coefficient heatmap among selected major oxides and trace elements, together with grain size and lithology fraction in sediment core DZQ01. Notes: *p < 0.05; and **p < 0.01.

5.2 Paleosalinity

The Sr/Ba, Mg/Ca, Mg/Al, and Sr/Ca ratios are established paleosalinity proxies that discriminate depositional environments. These ratios exhibit distinct patterns across marine, terrestrial, and transitional settings.

Sr/Ba ratio increase with salinity, being markedly higher in seawater than in freshwater (Chen et al., 1997). Sr is highly mobile and derived from seawater and mineral weathering, whereas Ba originates from crustal weathering, detrital input, and biogenic processes. In seawater, Sr exceeds Ba and becomes increasingly dominant at elevated salinities (Brand and Veizer, 1980; McArthur et al., 2008; Allmen et al., 2010). Consequently, Sr/Ba effectively discriminates depositional environments: marine setting yield Sr/Ba >0.8, transitional environment 0.5–0.8, and terrestrial system <0.5 (Tang, 2019). Sr >160 ppm further supports marine conditions (Chen et al., 1997), and elevated Sr/Ba may also reflect elevated marine productivity (Wang A. H. et al., 2021; Dashtgard et al., 2022). In drill-core DZQ01, Sr/Ba ranges from 0.5 to 0.8 across all six DUs, consistent with a marine-terrestrial transitional settings and DU5 attains the highest ratio (≈0.72), whereas the remaining units cluster narrowly (0.63–0.66), limiting the discriminatory power of Sr/Ba for intra-core paleosalinity reconstruction (Figure 6a).

Figure 6. Box-plots of paleosalinity-related geochemical proxies in Core DZQ01. (a) Sr/Ba ratio, (b) Mg/Ca ratio, (c) Mg/Al ratio, and (d) Sr/Ca ratio. The cutoff of the Sr/Ba, Mg/Ca, and Mg/Al according to the references.

In seawater, Mg and Ca display contrasting solubility behaviour. Rising salinity enhances Mg solubility but promotes Ca precipitate or desolvation. Consequently, Mg becomes enriched relative to Ca, elevating the Mg/Ca ratio in high-salinity setting (Ma et al., 2023). The Mg/Ca ratio is also modulated by provenance and weathering intensity; dolomite dissolution, for example, preferentially releases Mg over Ca, further elevating sedimentary Mg/Ca (Billups and Schrag, 2003; De Nooijer et al., 2017; Dunlea et al., 2017). Mg/Ca is widely applied as a paleosalinity proxy: >1 indicates marine conditions, 0.4–1 brackish water, and <0.4 freshwater (Martín et al., 2008; Peng et al., 2021). In drill-core DZQ01, DU2 and DU6 yield Mg/Ca <0.4, consistent with freshwater deposition. DU1, DU3, DU4, and DU5 record Mg/Ca = 0.4–1, indicative of brackish conditions. DU4 occupies the freshwater-brackish boundary, whereas DU3 attains the highest salinity, reflecting pronounced marine incursion (Figure 6b). These pronounced Mg/Ca differences underscore salinity fluctuations among stratigraphic intervals.

The Mg/Al ratio discriminates depositional environments. Mg derives predominantly from seawater and covaries with salinity (Berg et al., 2019), whereas Al, source chiefly from terrigenous clay minerals as insoluble aluminosilicates, is sensitive to salinity. Elevated Mg/Al denotes high salinity and marine dominance, lower ratio imply freshwater conditions or enhanced terrigenous influx (Gravina et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Diagnostic thresholds are: Mg/Al <1 (freshwater), 1–10 (brackish water), 10–500 (marine), >500 (Stanistreet et al., 2020). In dirll-core DZQ01, Mg/Al averages <1in DU2, DU4, and DU6 (freshwater). 1–10 in DU1, DU3, and DU5 (marine-terrestrial transitional), the latter appreciable terrigenous input (Figure 6c).

The Sr/Ca ratio serves as a proxy for surface-water paleoproductivity. During plankton growth, Ca2+ is preferentially incorporated into skeletal carbonate, whereas Sr2+ uptake is limited (Jin et al., 2011; Mario et al., 2020). Competitive uptake of these geochemical analogues generates an inverse Sr/Ca-productivity relationship: elevated productivity release Ca2+ and lowers Sr/Ca, diminished productivity raises the ratio (Stoll and Schrag, 2001; Peek and Clementz, 2012; Zhang et al., 2020). DU1 and DU3 exhibit lower Sr/Ca (30, 39, high productivity), DU4 and DU5 elevated Sr/Ca (83, 63, low productivity), and DU2 and DU6 intermediate values (53, 47, moderate productivity) (Figure 6d).

Geochemical signatures indicate that DU1 and DU3 record high-productivity, marine-terrestrial transitional settings; DU5 represents a moderate-productivity transitional environment influenced by terrigenous flux.; DU2, DU4, and DU6 denote low-productivity freshwater deposition.

Interpretation of Sr/Ba, Mg/Ca, Mg/Al, and Sr/Ca as paleosalinity proxies must account for grain-size effect. Sr is concentrated in coarser carbonate grains and seawater, whereas Ba is adsorbed onto organic matter and clay minerals, enriching finer fractions; coarsening thus elevates Sr/Ba (Wei and Algeo, 2020; Wang A. H. et al., 2021). Ca resides chiefly in coarse-grained calcite and aragonite; increased coarse fractions raise Ca content. Mg is incorporated via adsorption onto clay or precipitation within carbonate, and fine-grained clay and carbonate preferentially sequester Mg. Coarse-carbonate dominance lowers Mg/Ca, whereas fine-particles enrichment elevates it (Barker et al., 2005; Hoogakker et al., 2009; Poulain et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2021). Al, hosted in aluminosilicates, is enriched in clay-rich, fine-grained fractions. Mg preferentially adsorbs onto fine particles, elevating Mg/Al and biasing paleosalinity estimate (Von et al., 1990). Coarser grain adsorb Sr, raising Sr/Ca (Peek and Clementz, 2012).

Sr/Ba versus Mz yields r = −0.024, indicating neglibible grain-size control; Consistent with earlier findings, Sr/Ba is a weak paleosalinity proxy. Mg/Al versus Mz (r = 0.72) is strongly grain-size dependent. Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca exhibit moderate with Mz (|r| = 0.51–0.52), implying limited grain-size influence (Figure 5). Consequently, Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca provide the most robust paleosalinity signals in the study area.

5.3 Paleoredox environment

The U/Th, Ni/Co, and V/Cr ratios are widely employed as robust proxies of paleoredox conditions. Under oxic conditions, U is readily mobilised and transported from the soild phase to the water column, whereas Th remains largely immobile within the sedimentary matrix. Consequently, oxic settings yield low U/Th ratios, whereas anoxic to hypoxic environments, promote U enrichment and generate elevated U/Th values (Riquier et al., 2006; Ruffell et al., 2006; Adelabu et al., 2021). U/Th <0.75 indicates oxic conditions, 0.75–1.25 hypoxic conditions, and >1.25 anoxic conditions (Jones and Manning, 1994). In the six DUs of core DZQ01, U/Th ratios are consistently <0.75, with only a few exceptions in DU4, signifying persistently oxic bottom water since the Middle Pleistocene. Notably, DU1 and DU3 exhibit the lowest U/Th values, underscoring episodes of pronounced oxygenation (Figure 7a).

Figure 7. Box-plots of paleoredox-related geochemical proxies in Core DZQ01. (a) U/Th ratio, (b) Ni/Co ratio, and (c) V/Cr ratio. The cutoff of the U/Th and Ni/Co according to the references.

Both Ni and Co are incorporated into pyrite (Karl, 1975). Under reducing conditions, Ni preferentially complexes with organic matter and sulfides phases, forming stable sulfide that accumulate in the sediments column. Conversely, Co remains stable under oxic conditions, scavenged by Fe− and Mn− oxyhydroxides that precipitate onto particle surfaces. Under reducing conditions, Co solubility increases, facilitating its remobilization into the water column and diminishing its sedimentary retention (Chao et al., 2021). Ni/Co <5 denotes oxic conditions, 5–7 hypoxic conditions, and >7 anoxic conditions (Jones and Manning, 1994). In core DZQ01, DU6 yields Ni/Co >7, indicating episodic anoxia. DU5 displays hypoxic signatures, whereas DU1–DU4 exhibit Ni/Co <5, consistent with oxic deposition (Figure 7b).

Under oxic conditions, V (pentavalent HVO42- and H2VO4−) has low sedimentary concentrations (Breit et al., 1991). Cr (hexavalent CrO42-) scavenged into sediments lowering V/Cr ratio (Calvert and Pedersen, 1993). Reducing conditions, V reduces (precipitates/sequesters), Cr shifts to trivalent (mild) or more soluble (strong), elevating V/Cr ratio (Francois, 1988; Crusius et al., 1996). V/Cr <2 indicates oxic conditions; 2–4.25 hypoxic conditions; and >4.25 anoxic environment (Ernst, 1970; Jones and Manning, 1994). Throughout the six DUs V/Cr remains <2, consistent with persistently oxic deposition (Figure 7c). These V/Cr signatures contrast with the Ni/Co record, which exhibits an inverse stratigraphic trend. This discrepancy likely reflects the dominant terrigenous origin of V and Cr, whose ratios are therefore strongly modulated by provenance and detrital composition. Conversely, Ni and Co behavior is governed primarily by redox processes within the depositional environment. Consequently, V/Cr and Ni/Co track different biogeochemical mechanisms and should be interpreted cautiously when employed as paleoredox proxies.

When employing U/Th, Ni/Co, and V/Cr ratios as paleoredox proxies, the influence of grain size and organic matter input must be explicitly evaluated. U preferentially associates with organic matter and clay minerals and thus becomes enriched in fine-grained sediments under reducing conditions. Under oxidising conditions, however, U is mobilised via dissolution and subsequently reprecipitated in coarser lithologies such as sands or gravel (Andersen et al., 2014; Wang J. et al., 2021). The elevated porosity and permeability of these coarse facilitate fluid circulation and secondary U enrichment, elevating U/Th ratios relative to finer-grained counterparts. Co is dominantly hosted in terrigenous detrital minerals and is therefore concentrated in coarse particles, whereas Ni is preferentially bound to clay minerals, organic matter, and Fe-Mn oxyhydroxides in fine-grained fractions, yielding higher Ni/Co ratio in mud-rich sediments (Bajwah et al., 1987). V is likewise enriched in fine-grained sediments through complexation with organic matter and clay minerals, whereas Cr is concentrated in coarse-grained heavy-minerals assemblages (Wei, 2012). Consequently, fine-grained sediments exhibit elevated V/Cr ratio, whereas coarse-grained sediments display lower values.

First, the correlation coefficients between the U/Th, Ni/Co, and V/Cr ratios (paleoredox proxies) and the C/N ratio (organic matter source proxy) are all very low, with values of 0.29, −0.087, and −0.0034, respectively—thus ruling out the influence of organic matter input on these paleoredox proxies. Correlation analyses between these elements proxies and Mz reveal a strong negative correlation for U/Th (r = −0.72), confirming preferential enrichment of U in coarser-grained lithologies. Ni/Co exhibits a statistically insignificant correlation (r = 0.0093), whereas V/Cr is moderately positively correlated with Mz (r = 0.22), consistent with enrichment in fine-grained sediments. Collectively, these data indicate that Ni/Co is the most reliable paleoredox indicator among the three ratios, as it least affected by grain-size variability.

5.4 Evolution of sedimentary environments

During the Late Cretaceous–Paleogene (66–23.03 Ma), the structural nature of the Tan-Lu Fault Zone transitioned from a pre-existing compressive-shear regime to an extensional regime (Zhu et al., 2004). This extension acted as a dominant driver of the Bohai Basin, regulating the development and positioning of tectonic depression within the basin (Huang and Liu, 2014). Since the initiation of the Quaternary (∼2.58 Ma), the regional tectonic framework has been defined by the collaborative interplay of multiple plates: in the western sector, the Tibetan Plateau underwent rapid uplift—accompanied by northeastward tectonic expansion—driven by the far-field effects of sustained collision between the Indian and Eurasian Plates; in the eastern sector, a complex “trench-arc-basin” tectonic system (a hallmark of active continental margins) was developed along the eastern margin of the East Asian Continent, controlled primarily by the subduction and consumption of the Pacific Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate (Wang et al., 2011).

Against this tectonic backdrop, the Minzhe Uplift Zone and Miaodao Uplift Zone, located in the eastern continental shelf of China, experienced regional-scale subsidence (Sun et al., 2022). This subsidence event directly triggered the reconstruction of the paleogeomorphic framework in the shelf domain: the originally semi-enclosed continental setting gradually transited into a proto-basin with the capacity to retain seawater, ultimately facilitating and governing the formation of the Yellow Sea and BS. This integrated evolutionary process of tectonics and geomorphology not only furnished the essential accommodation space for multiple episodes of large-scale transgressions in eastern China since the Quaternary but also fundamentally established the land-sea distribution pattern of this region.

Core DZQ01 in the BS preserves a continuous sedimentary record since the Middle Pleistocene, which documents three transgressions-regressions cycles. Integration of paleoclimate, paleosalinity, and paleoredox proxies enables the subdivision of this sedimentary succession into six evolutionary stages.

5.4.1 DU6 (early MIS 8 period, 300–272 cal. ka B.P.)

The lithology is dominated by sand and silty sand, characterized by a relatively coarse median grain size (Figures 8a,h). Lower Rb/Sr ratio indicates prevailing cold-arid conditions (Figure 8b), whereas Mg/Ca and Ni/Co values denote a fluvial-lacustrine, fresh-water environment whose bottom waters evolved from hypoxic to oxic and subsequently return to hypoxic conditions in the BS (Figures 8c,d). According to LR04 benthic δ18O record (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005), global eustatic sea levels were relatively low at ∼300 cal. ka B.P., a time corresponding to the transition from MIS9 to MIS8. Subsequently, global sea-surface temperatures and eustatic sea-level began to rise after 300 cal. ka B.P. but this rising trend reversed after ∼285 cal. ka B.P. (Miller et al., 2005) (Figure 8e). Sedimentation was dominated by YR-derived fluvial and overbank deposits (Wu et al., 2024b). Recent modelling suggests that the Arctic ice sheet contracted during much of MIS 8, a trend that appears to conflict with concurrent increase in benthic δ18O values (Hao et al., 2024). This apparent contradiction may reflect intensification of Antarctic bottom water formation, whose cooling signature propagated through the deep ocean and is recorded by rising δ18O. In East Asia, the coeval strengthening of the EAWM exerted the dominant climatic control (Wu et al., 2024a).

Figure 8. Composite Stratigraphic Profile of the Sedimentary Environment Characteristics from the core DZQ01. (a) Mean grain size; (b) Rb/Sr ratio; (c) Ni/Co ratio; (d) Mg/Ca ratio; (e) Average temperatures; (f) Global sea-level changes (Miller et al., 2005); (g) Deep-sea δ18O record (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005); (h) Lithological characteristics and chronological framework; (i) Downcore variation distribution of benthic foraminifera, marine ostracods, and non-marine ostracods represent the total counts of each taxonomic group in Figure 2.

5.4.2 DU5 (late MIS 8–Early MIS 7 period, 272–205 cal. ka B.P.)

The Rb/Sr ratio indicates that the earliest part of DU5 continued the cold-dry conditions of DU6, followed by a progressive temperature rise (Figure 8b). Between 260 and 230 cal. ka B.P., declining benthic δ18O values (Figure 8g) signal a shifted to warmer, humid climate (Figure 8b), and global eustatic sea level began to rise (Figure 8f). Peak warmth was attained ∼240 cal. ka B.P. (Figure 8e), coinciding with maximum marine transgression across the study area (Figure 8b). Bottom waters were predominantly hypoxic, with transient anoxic between 253 and 256 cal. ka B.P. (Figure 8c). After 230 cal. ka B.P., two millennial-scale cool-warm oscillations are recorded globally (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Miller et al., 2005) (Figure 8e); nevertheless, the study area remained comparatively cold and dry (Figure 8b). The Mg/Ca record reveals two discrete marine incursions, early (272–260 cal. ka B.P.) and late (230–210 cal. ka B.P.) in DU5 (Figure 8d), whereas Ni/Co ratio indicate persistent hypoxic conditions (Figure 8c). Lithologically, the succession corresponds to grogradationsl tidal-flat to shallow-marine facies. Benthic foraminiferal assemblages suggests a warm, shallow, brackish setting, and only transient, localised freshwater influxes (Figure 8i). DU5 represents a shallow-marine depositional system modulated by orbitally paced climate warming, eustatic sea-level rise and fluctuating redox conditions.

High-resolution U-series chronologies from the Austrian Alps constrain the onset of MIS 7e warming to 242.5 ± 0.2 cal. ka B.P., with peak interglacial conditions persisting from 241.8 to 236.7 ± 0.6 cal. ka B.P. (Wendt et al., 2021). Consistently, planktonic foraminiferal records from site MD12-3429 in the northern South China Sea indicate elevate surface-water nutrients and recurrent bottom-water hypoxia throughout MIS 7 (Li et al., 2017).

5.4.3 DU4 (late MIS 7–Early MIS 5 period, 205–90 cal. ka B.P.)

Global climate deteriorated progressively: surface temperatures declined (Figure 8e), benthic δ18O values increased (Figure 8g), and eustatic sea level fell (Figure 8f) (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Miller et al., 2005). The study area evolved into a brackish-to-freshwater transitional setting characterized by persistently oxic bottom water (Figures 8c,d). Despite the global warming and eustatic sea-level rise that occurred 130–110 cal. ka B.P. (corresponding to MIS 5e; Figures 8e–g), this warming episode did not interrupt the overarching cold and arid climatic regime in the BS (Figure 8b). Sedimentation was dominated by extensive fluvial systems–braided and meandering channels, flood-plains and small lakes–sourced chiefly from the YR, LR, and LiaoR (Wu et al., 2024b).

Microfossil analyses indicate that during the severe cold-stage of the DU4, the study area was dominated by perennial freshwater lakes and low-gradient fluvial networks. Scattered benthic foraminifera first appeared between 130 and 110 cal. ka B.P. (Figure 8i). These taxa record a brief, low-magnitude marine incursion, which corresponds to the global high-sea-level event of MIS 5e.

5.4.4 DU3 (late MIS 5- MIS4 period, 90–57 cal. ka B.P.)

During MIS 5a (∼90–71 cal. ka B.P.), global eustatic sea level stood ∼10–20 m below than the present-day level (Miller et al., 2005) (Figure 8e). Despite this relatively depressed global sea level, the western BS experienced warm and humid climate regime (Figure 8b) and developed continuous neritic facies deposits in response to regional relative sea-level rise during this interval (Figure 8d). These sediments were accumulated in a shallow-marine characterized by fully oxic conditions (Figure 8c). Microfossil assemblages indicate a warm, nearshore, low-moderate salinity environment subject to periodic freshening and record minor, localised freshwater discharge (Figure 8i).

Collectively, DU3 reflects a fully marine depositional system established in response to orbitally forced warming and rapid sea-level rise. Tropical Pacific sea surface temperature (SST) during MIS 5 were governed by variations in eccentricity, obliquity, and precession, intensifying ENSO-like variability and driving a northward migration of the ITCZ (Mark, 1998).

5.4.5 DU2 (late MIS 4–MIS 2 period, 57–14 cal. ka B.P.)

This interval encompasses the last glacial period from MIS4 to MIS2 and is characterised by a monotonic decline in global temperatures (Figure 8e), rising δ18O values (Figure 8g) and falling eustatic sea level (Figure 8f). The study area lay under persistent cold-arid conditions (Figure 8b) and accumulated continental, freshwater deposits (Figure 8d) delivered by the YR, LR, and LiaoR (Wu et al., 2024b). DU2 is dominated by meandering-river facies, microfossil assemblages imply brief, low-energy incursions of warm, shallow marine or intertidal water, probable within isolated estuarine embayment during periods of slightly elevated relative sea level.

Rare-gas measurement on a 0.24 m ice core from Taylor Glacier (Sarah et al., 2021) indicate that Marine Oxygen Isotope Temperature (MOT) reached its minimum for the last glacial cycle during MIS 4, whereas atmospheric CO2 and δ18O did not peak until MIS 2. Ocean cooling thus outpaced both ice-sheet expansion and CO2 drawdown, driving a continuous decline in ocean temperatures from MIS 4 to MIS 2. Continental records from northern Europe (Karin, 2013) likewise document the progressive growth of continental-scale ice sheets and increasing aridity between 70 and 15 cal. ka B.P., corroborating the sustained deterioration of global climate during MIS 4–2.

5.4.6 DU1 (MIS 1 period, 14 cal. ka B.P.–Present)

Since 14 cal. ka B.P., global temperatures has risen steadily (Figure 8e), and eustatic sea levels has climbed to its present highstand (Figure 8f). The study area has entered a warm, humid climatic regime (Figure 8b). At the DZQ01 site, continuous mixing of YR fresh water with marine incursions has produced a brackish, fully oxic, coastal-shallow-marine environment (Figures 8c,d). Benthic foraminiferal assemblages are dominated by euryhaline, warm-water taxa, characteristic of intertial and inner-neritic settings with moderate to high salinity. Confirming sustained marine influence. The progressive enrichment of these taxa up-core records the landward migration of the shoreline to its modern position.

Frederikse et al. (2020) attributes the post-glacial sea-level rise to the thermal expansion of seawater, mass loss from glaciers and ice sheets, and anthropogenic alterations in terrestrial water storage–processes that have collectively elevated global mean sea level throughout MIS 1.

6 Conclusion

1. High-resolution geochemical profiles from core DZQ01constrain six DUs (DU1–6) in the western BS. Rb/Sr discriminate warm interglacial intervals (DU1, DU3) from cold-arid glacial stages (DU2, DU4, DU5, DU6). Mg/Ca distinguishes freshwater (DU2, DU6) versus brackish-marine setting (DU1, DU3–5). Ni/Co traces a progressive oxygenation trend from anoxic DU6 to fully oxic DU1.

2. DU6 (300–272 cal. ka B.P., Early MIS 8)–cold-arid fluvial; DU5 (272–205 cal. ka B.P., Late MIS 8–Early MIS 7) – glacial oneset, mid-unit eustatic highstand, then regressive; DU4 (205–90 cal. ka B.P., Late MIS 7–Early MIS 5) – domainantly cold-arid with brief 130–110 cal. ka B.P. marine incursion; DU3 (90–57 cal. ka B.P., Late MIS 5- MIS4) – last interglacial marine transgression; DU2 (57–14 cal. ka B.P., Late MIS 4–MIS 2) –sustained cold-arid meandering-rive; DU1 (14 cal. ka B.P. – Present, MIS 1) –post-glacial coastal-marine.

3. These glacial-interglacial alternations are governed by orbital forcing, modulated by ocean-atmospheric circulation, ice-sheet dynamics and regional hydro-climate feedbacks.

4. In furture research, over-reliance on single geochemical element indicators should be avoided. Instead, a multi-indicator system integrating “major elements (for provenance identification) + trace elements (for redox condition reconstruction) + isotopes (for paleoenvironment restoration)” should be established. This integrated methological framework can significantly mitigate ambiguity in the analysis of sedimentary environment.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. HC: Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. MA: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. YF: Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. JL: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was jointly supported by Observation and Research Station of South Yellow Sea Earth Multi-sphere, MNR “Research on the identification of organic carbon sources and their genetic mechanisms in the mudy area of the Central and Western South Yellow Sea since the Holocene” (Grant No.: SYS-2025-G03); “Temporal and spatial distribution of paleochannels and the origin of organic carbon buried in the Western Bohai Sea since 2.28Ma” (KC20220011) by the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of the Command Center of Natural Resources Comprehensive Survey; “Characterization of Carboniferous-Early Permian Heterogeneous Porous Carbonate Reservoirs and Hydrocarbon Potential Analysis in The Central Uplift of the South Yellow Sea Basin” (KLSG2304) by the Key laboratory of Submarine Geosience, Ministry of Natural Resources; the project entitled “1:25000 Marine Regional Geological Survey in Weihai Sea Area, North Yellow Sea (DD20230412)” supported by the China Geological Survey.

Acknowledgments

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to express their gratitude to the Yantai Center of Coastal Zone Geological Survey, China Geological Survey for providing basic data, and Ph. D Jun Liu for his help in this study. The authors are also grateful to the editors and reviewers who provided sincere comments and assisted in writing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial of financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adelabu, I. O., Opeloye, S. A., Oluwajana, O. A., and Ogbahon, O. A. (2021). Paleoredox conditions of Paleocene to miocene rocks of eastern Benin (dahomey) basin, nigeria: implications for chemostratigraphy. Int. J. Geogr. Geol. 10, 24–35. doi:10.18488/journal.10.2021.101.24.35

Allmen, V. K., Böttcher, M. E., Samankassou, E., and Nägler, T. F. (2010). Barium isotope fractionation in the global barium cycle: first evidence from barium minerals and precipitation experiments. Chem. Geol. 277, 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.07.011

Alqahtani, F. A., Johnson, H. D., Jackson, C. A. L., and Som, M. R. B. (2015). Nature, origin and evolution of a late pleistocene incised valley-fill, sunda shelf, southeast Asia. Sedimentology 62, 1198–1232. doi:10.1111/sed.12185

Andersen, M. B., Romaniello, S., Vance, D., Little, S. H., Herdman, R., and Lyons, T. W. (2014). A modern framework for the interpretation of 238u/235u in studies of ancient ocean redox. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 400, 184–194. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.051

Bajwah, Z. U., Seccombe, P. K., and Offler, R. (1987). Trace element distribution, co:ni ratios and genesis of the big cadia iron-copper deposit, new south wales, Australia. Min. Depos. 22, 292–300. doi:10.1007/bf00204522

Barceló, M., Vargas, C. A., and Gelcich, S. (2023). Land–sea interactions and ecosystem services: research gaps and future challenges. Sustainability 15, 8068. doi:10.3390/su15108068

Barker, S., Cacho, I., Benway, H., and Tachikawa, K. (2005). Planktonic foraminiferal mg/ca as a proxy for past oceanic temperatures: a methodological overview and data compilation for the last glacial maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 821–834. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.07.016

Bentley, S. J., Blum, M. D., Maloney, J., Pond, L., and Paulsell, R. (2016). The mississippi river source-to-sink system: perspectives on tectonic, climatic, and anthropogenic influences, miocene to anthropocene. Earth Sci. Rev. 153, 139–174. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.11.001

Berg, R. D., Solomon, E. A., and Teng, F. (2019). The role of marine sediment diagenesis in the modern oceanic magnesium cycle. Nat. Commun. 10, 4371–10. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12322-2

Billups, K., and Schrag, D. P. (2003). Application of benthic foraminiferal mg/ca ratios to questions of cenozoic climate change. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 209, 181–195. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00067-0

Brand, U., and Veizer, J. (1980). Chemical diagenesis of a multicomponent carbonate system; 1, trace elements. J. Sediment. Petrology 50, 1219–1236. doi:10.1306/212F7BB7-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

Breit, G. N., Wanty, R. B., Branthaver, J. F., and Filby, R. H. (1991). Vanadium accumulation in carbonaceous rocks; A review of geochemical controls during deposition and diagenesis. Chem. Geol. 91, 83–97. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(91)90083-4

Brookfield, M. E., Williams, J., and Stebbins, A. G. (2020). Geochemistry of the new Permian-Triassic boundary section at Sitarička Glavica, Jadar block, Serbia. Chem. Geol. 550, 119696. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119696

Cai, Q. F., Liu, D. Y., Jia, P. M., and Shao, C. G. (2015). Application status of pollen proxies to paleoclimate and paleo sea-level changes in Chinese coastal zone. J. Geol. 39, 621–626. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-3636.2015.04.621

Calvert, S. E., and Pedersen, T. F. (1993). Geochemistry of recent oxic and anoxic marine sediments: implications for the geological record. Mar. Geol. 113, 67–88. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(93)90150-T

Chao, H., Hou, M. C., Jiang, W. J., Cao, H. Y., Chang, X. L., Luo, W., et al. (2021). Paleoclimatic and redox condition changes during early-middle jurassic in the yili basin, northwest China. Miner. (Basel) 11, 675. doi:10.3390/min11070675

Chen, Z. Y., Chen, Z. L., and Zhang, W. G. (1997). Quaternary stratigraphy and trace-element indices of the yangtze delta, eastern China, with special reference to marine transgressions. Quat. Res. 47, 181–191. doi:10.1006/qres.1996.1878

Chen, J., An, Z., and Head, J. (1999). Variation of rb/sr ratios in the loess-paleosol sequences of central China during the last 130,000 years and their implications for monsoon paleoclimatology. Quanternary Res. 51, 215–219. doi:10.1006/qres.1999.2038

Chen, J., Wang, Y. J., Chen, Y., Liu, L. W., Ji, J. F., and Lu, H. Y. (2000). Rb and Sr geochemical characterization of the Chinese loess stratigraphy and its implications for palaeomonsoon climate. Acta Geol. Sin. 74, 279–288. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2000.tb00462.x

Chen, J. X., Shi, X. F., and Qiao, S. Q. (2012). Holocene palynological sequences and palaeoenvironmental changes in the Bohai Sea area. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 34, 99–105.

Chen, G. Q., Tang, Y. T., Nan, Y. H., Yang, F., and Wang, D. Y. (2023). Paleo-sedimentary environments and controlling factors for enrichment of organic matter in alkaline lake sediments: a case study of the lower permian fengcheng formation in well f7 at the western slope of mahu sag, junggar basin. Process. (Basel). 11, 2483. doi:10.3390/pr11082483

Chevalier, M., Davis, B. A. S., Heiri, O., Seppä, H., Chase, B. M., Gajewski, K., et al. (2020). Pollen-based climate reconstruction techniques for late quaternary studies. Earth Sci. Rev. 210, 103384. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103384

Crusius, J., Calvert, S. E., Pedersen, T., and Sage, D. (1996). Rhenium and molybdenum enrichments in sediments as indicators of oxic, suboxic and sulfidic conditions of deposition. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 145, 65–78. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(96)00204-X

Dasch, E. J. (1969). Strontium isotopes in weathering profiles, deep-sea sediments, and sedimentary rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 33, 1521–1552. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(69)90153-7

Dashtgard, S. E., Wang, A. H., Pospelova, V., Wang, P. L., La Croix, A., and Ayranci, K. (2022). Salinity indicators in sediment through the fluvial-to-marine transition (fraser river, Canada). Sci. Rep. 12, 14303. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18466-4

De Nooijer, L. J., Van Dijk, I., Toyofuku, T., and Reichart, G. J. (2017). The impacts of seawater mg/ca and temperature on element incorporation in benthic foraminiferal calcite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 18, 3617–3630. doi:10.1002/2017GC007183

Du, S. H., Li, B. S., Niu, D. F., Zhang, D. D., Wen, X. H., Chen, D. N., et al. (2011). Age of the mgs5 segment of the milanggouwan stratigraphical section and evolution of the desert environment on a kiloyear scale during the last interglacial in China's salawusu river valley: evidence from rb and sr contents and ratios. Geochemistry 71, 87–95. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2010.07.002

Dunlea, A. G., Murray, R. W., Santiago Ramos, D. P., and Higgins, J. A. (2017). Cenozoic global cooling and increased seawater mg/ca via reduced reverse weathering. Nat. Commun. 8, 844. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00853-5

Fan, Q. C., Xu, Z. K., Sun, T. Q., Li, T. G., and Chang, F. M. (2022). Sediment source-to-sink processes of the southeastern Indian Ocean during the late Eocene-Oligocene and their potential significance for paleoclimate. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 41, 9–19. doi:10.19509/j.cnki.dzkq.2022.0066

Fang, Y., Fang, G. H., and Zhang, Q. H. (2000). Numerical simulation and dynamic study of the wintertime circulation of the bohai sea. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 18, 1–9. doi:10.1007/BF02842535

Fedo, C. M., Nesbitt, H. W., and Young, G. M. (1995). Unraveling the effects of potassium metasomatism in sedimentary rocks and paleosols, with implications for paleoweathering conditions and provenance. Geology 23, 921–924. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0921:uteopm>2.3.co;2

Francois, R. (1988). A study on the regulation of the concentrations of some trace metals (rb, sr, zn, pb, cu, v, cr, ni, mn and mo) in saanich inlet sediments, british columbia, Canada. Mar. Geol. 83, 285–308. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(88)90063-1

Frederikse, T., Landerer, F., Caron, L., Adhikari, S., Parkes, D., Humphrey, V. W., et al. (2020). The causes of sea-level rise since 1900. Nature 584, 393–397. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2591-3

Fu, J. H., Li, S. X., Xu, L. M., and Niu, X. B. (2018). Paleo-sedimentary environmental restoration and its significance of chang 7 member of triassic yanchang formation in ordos basin, nw China. Petroleum Explor. Dev. 45, 998–1008. doi:10.1016/S1876-3804(18)30104-6

Gallet, S., Jahn, B., and Torii, M. (1996). Geochemical characterization of the luochuan loess-paleosol sequence, China, and paleoclimatic implications. Chem. Geol. 133, 67–88. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(96)00070-8

Gravina, P., Ludovisi, A., Moroni, B., Vivani, R., Selvaggi, R., Petroselli, C., et al. (2022). Geochemical proxies and mineralogical fingerprints of sedimentary processes in a closed shallow lake basin since 1850. Aquat. Geochem 28, 43–62. doi:10.1007/s10498-022-09403-y

Guan, B. X. (1994). Patterns and structures of the currents in bohai, huanghai and east China seas. Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0862-1_3

Hao, Q. Z., Peng, S. Z., Gao, X. B., Marković, S. B., Li, S. H., Zhang, J. J., et al. (2024). Unusual weakening trend of the east asian winter monsoon during mis 8 revealed by chinese loess deposits and its implications for ice age dynamics. Glob. Planet Change 234, 104389. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2024.104389

Hoogakker, B. A. A., Klinkhammer, G. P., Elderfield, H., Rohling, E. J., and Hayward, C. (2009). Mg/ca paleothermometry in high salinity environments. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 284, 583–589. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.027

Hu, S. B., O'Sullivan, P. B., Raza, A., and Kohn, B. P. (2001). Thermal history and tectonic subsidence of the bohai basin, northern China: a cenozoic rifted and local pull-apart basin. Phys. Earth Planet Inter 126, 221–235. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00257-6

Huang, L., and Liu, C. (2014). Evolutionary characteristics of the sags to the east of tan–lu fault zone, bohai bay basin (china): implications for hydrocarbon exploration and regional tectonic evolution. J. Asian Earth Sci. 79, 275–287. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2013.09.031

Jeong, G. Y., Cheong, C., and Kim, J. (2006). Rb–sr and k–ar systems of biotite in surface environments regulated by weathering processes with implications for isotopic dating and hydrological cycles of sr isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 4734–4749. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2006.07.012

Jin, Z. D., Bickle, M. J., Chapman, H. J., Yu, J. M., An, Z. S., Wang, S. M., et al. (2011). Ostracod mg/sr/ca and 87sr/86sr geochemistry from tibetan lake sediments: implications for early to mid-pleistocene indian monsoon and catchment weathering. Boreas 40, 320–331. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2010.00184.x

Jones, B., and Manning, D. A. C. (1994). Comparison of geochemical indices used for the interpretation of palaeoredox conditions in ancient mudstones. Chem. Geol. 111, 111–129. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(94)90085-X

Karin, F. H. (2013). The last interglacial-glacial cycle (mis 5-2) re-examined based on long proxy records from central and northern Europe.

Karl, K. (1975). Geochemical facies of sediments. Soil Sci. 119, 20–23. doi:10.1097/00010694-197501000-00004

Kim, Y., Caumon, M. C., Barres, O., Sall, A., and Cauzid, J. (2021). Identification and composition of carbonate minerals of the calcite structure by raman and infrared spectroscopies using portable devices. Spectrochimica Acta Part a Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 261, 119980. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2021.119980

Li, F. L., Yan, Y. Z., Shang, Z. W., Wang, H., Wang, F., Chen, Y., et al. (2014). Holocene climate evolution and land-sea changes on west Bohai Sea. J. Geol. 38, 173–186. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-3636.2014.02.173

Li, H., Huang, B. Q., and Wang, N. (2017). Changes of the palaeo-sea surface productivity and bottom water dissolved oxygen content at Md12-3429, Northern South China Sea. Acta Palaeontol. Sin. 56, 238–248. doi:10.19800/j.cnki.aps.2017.02.010

Li, J., Yang, S. X., Ye, S. Y., and He, L. (2019). The characteristics of palynous assemblages of alluvial sediments in the Bohai Sea and their implications for palynous sources in the sea. Mar. Geol. Front. 35, 81–84. doi:10.16028/j.1009-2722.2019.12011

Li, Y., Han, Q., Hao, L., Zhang, X. Z., Chen, D. W., Zhang, Y. X., et al. (2021). Paleoclimatic proxies from global closed basins and the possible beginning of anthropocene. J. Geogr. Sci. 31, 765–785. doi:10.1007/s11442-021-1870-8

Lisiecki, L. E., and Raymo, M. E. (2005). A pliocene-pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18o records. Paleoceanography 20, 2004PA001071. doi:10.1029/2004PA001071

Liu, D. Y., Liu, L. X., Di, B. P., Wang, Y. J., and Wang, Y. N. (2015). Paleoenvironmental analyses of surface sediments from the bohai sea, China, using diatoms and silicoflagellates. Mar. Micropaleontol. 114, 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2014.11.002

Lyu, W. Z., Yang, J. C., Fu, T. F., Chen, Y. P., Hu, Z. X., Tang, Y. Z., et al. (2020). Asian monsoon and oceanic circulation paced sedimentary evolution over the past 1,500 years in the central mud area of the bohai sea, China. Geol. J. 55, 5606–5618. doi:10.1002/gj.3758

Ma, C. Y., Kang, Z. Q., Zhang, L. H., Xuan, H. I., Nong, P. J., Pan, S. F., et al. (2023). Dissolution and precipitation of calcite in different water environments. Carsologica Sin. 42 (29), 51–39. doi:10.11932/karst20230102

Mario, L., Dieter, G. S., Marius, N. M., Sonia, B. A., and Richard, A. F. (2020). Global variability in seawater mg:ca and sr:ca ratios in the modern ocean. Pnas 117, 22281–22292. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918943117/-/DCSupplemental

Mark, A. C. (1998). A role for the tropical pacific. Science 282, 59–61. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.59

Martín, M., David, W. L., and Matthew, S. F. (2008). Implications of seawater mg/ca variability for Plio-Pleistocene tropical climate reconstruction. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 269, 585–595. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.014

McArthur, J. M., Algeo, T. J., van de Schootbrugge, B., Li, Q., and Howarth, R. J. (2008). Basinal restriction, black shales, re-os dating, and the early toarcian (jurassic) oceanic anoxic event. Paleoceanography 23, PA4217. doi:10.1029/2008PA001607

McHugh, C. M., Fulthorpe, C. S., Hoyanagi, K., Blum, P., Mountain, G. S., and Miller, K. G. (2018). The sedimentary imprint of pleistocene glacio-eustasy; implications for global correlations of seismic sequences. Geosph. (Boulder, Colo.) 14, 265–285. doi:10.1130/GES01569.1

Mestdagh, T., Lobo, F. J., Llave, E., Hernandez-Molina, F. J., and van Rooij, D. (2019). Review of the late quaternary stratigraphy of the northern gulf of cadiz continental margin; new insights into controlling factors and global implications. Earth Sci. Rev. 198, 102944. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102944

Miller, K. G., Kominz, M. A., Browning, J. V., Wright, J. D., Mountain, G. S., Katz, M. E., et al. (2005). The phanerozoic record of global sea-level change. Science 310, 1293–1298. doi:10.1126/science.1116412

Milliman, J. D., Yun-Shan, Q., Mei-E, R., and Saito, Y. (1987). Man's influence on the erosion and transport of sediment by asian rivers; the yellow river (huanghe) example. J. Geol. 95, 751–762. doi:10.1086/629175

Neisbitt, H. W., and Yong, G. M. (1982). Early proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature 299, 715–717. doi:10.1038/299715a0

Peek, S., and Clementz, M. T. (2012). Sr/ca and ba/ca variations in environmental and biological sources: a survey of marine and terrestrial systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 95, 36–52. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2012.07.026

Peeters, J., Cohen, K. M., Thrana, C., Busschers, F. S., Martinius, A. W., Stouthamer, E., et al. (2019). Preservation of last interglacial and holocene transgressive systems tracts in the Netherlands and its applicability as a north sea basin reservoir analogue. Earth Sci. Rev. 188, 482–497. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.10.010

Peng, H. J., Bao, K. S., Yuan, L. G., Uchida, M., Cai, C., Zhu, Y. X., et al. (2021). Abrupt climate variability since the last deglaciation based on a high-resolution peat dust deposition record from southwest China. Quat. Sci. Rev. 252, 106749. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106749

Poulain, C., Gillikin, D. P., Thébault, J., Munaron, J. M., Bohn, M., Robert, R., et al. (2015). An evaluation of mg/ca, sr/ca, and ba/ca ratios as environmental proxies in aragonite bivalve shells. Chem. Geol. 396, 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.12.019

Qiao, S. Q., Shi, X. F., Wang, G. Q., Zhou, L., Hu, B. Q., Hu, L. M., et al. (2017). Sediment accumulation and budget in the bohai sea, yellow sea and east China sea. Mar. Geol. 390, 270–281. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2017.06.004

Reimer, P. J., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Beck, J. W., Blackwell, P. G., Ramsey, C. B., et al. (2013). Intcal13 and marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal bp. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947/

Riquier, L., Tribovillard, N., Averbuch, O., Devleeschouwer, X., and Riboulleau, A. (2006). The late frasnian kellwasser horizons of the harz mountains (germany): two oxygen-deficient periods resulting from different mechanisms. Chem. Geol. 233, 137–155. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.02.021

Ruffell, A., McKinley, J. M., Lloyd, C. D., and Graham, C. (2006). Th∕k and th∕u ratios from spectral gamma-ray surveys improve the mapped definition of subsurface structures. J. Environ. Eng. Geophys 11, 53–61. doi:10.2113/JEEG11.1.53

Sarah, S., James, A. M., Edward, B., Christo, B., Michael, N. D., Vasilii, V. P., et al. (2021). Evolution of mean ocean temperature in marine isotope stage 4. Clim. Past. 17, 1–17. doi:10.5194/cp-17-1-2021

Saraswat, R., Nigam, R., Li, T., and Griffith, E. M. (2017). Marine paleoclimatic proxies: a shift from qualitative to quantitative estimation of seawater parameters. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 483, 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.05.036

Shi, X. F., Yao, Z. Q., Liu, Q. S., Larrasoaña, J. C., Bai, Y. Z., Liu, Y. G., et al. (2016). Sedimentary architecture of the bohai sea China over the last 1 ma and implications for sea-level changes. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 451, 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.07.002

Song, S., Feng, X. L., Li, G. G., Wang, X. M., and Teng, S. (2018). Sedimentary sequences and paleoclimatic evolution of the current yellow river mouth Area since Holocene transgression, 48. Qingdao, China: Periodical of Ocean University of China, 80–89.

Southon, J., Kashgarian, M., Fontugne, M., Metivier, B., and Yim, W. W. (2002). Marine reservoir corrections for the indian ocean and southeast Asia. Radiocarbon 44, 167–180. doi:10.1017/S0033822200064778

Stanistreet, I. G., Boyle, J. F., Stollhofen, H., Deocampo, D. M., Deino, A., McHenry, L. J., et al. (2020). Palaeosalinity and palaeoclimatic geochemical proxies (elements ti, mg, al) vary with milankovitch cyclicity (1.3 to 2.0ma), ogcp cores, palaeolake olduvai, Tanzania. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 546, 109656. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109656

Stankevica, K., Vincevica-Gaile, Z., Klavins, M., Kalnina, L., Stivrins, N., Grudzinska, I., et al. (2020). Accumulation of metals and changes in composition of freshwater lake organic sediments during the holocene. Chem. Geol. 539, 119502. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119502

Stoll, H. M., and Schrag, D. P. (2001). Sr/ca variations in Cretaceous carbonates; relation to productivity and sea level changes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 168, 311–336. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00205-X

Stuiver, M., Grootes, P. M., and Braziunas, T. F. (1995). The gisp2 δ18o climate record of the past 16,500 years and the role of the sun, ocean, and volcanoes. Quat. Res. 44, 341–354. doi:10.1006/qres.1995.1079

Sun, J., Guo, F., Wu, H. C., Yang, H. I., Qiang, X. K., Chu, H. X., et al. (2022). The sedimentary succession of the last 2.25 myr in the bohai strait: implications for the quaternary paleoenvironmental evolution of the bohai sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 585, 110704. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110704

Tabor, N. J., and Myers, T. S. (2015). Paleosols as indicators of paleoenvironment and paleoclimate. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 43, 333–361. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-060614-105355

Tang, P. H. (2019). Application of geochemical parameters in sedimentary paleo-salt. Yunnan Chem. Technol. 46, 124–127. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-275X.2019.09.050

Tian, L. Z., Chen, Y. P., Jiang, X. Y., Wang, F., Pei, Y. D., Chen, Y. S., et al. (2017). Post-glacial sequence and sedimentation in the western bohai sea, China, and its linkage to global sea-level changes. Mar. Geol. 388, 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2017.04.006

Tribovillard, N., Algeo, T. J., Lyons, T., and Riboulleau, A. (2006). Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: an update. Chem. Geol. 232, 12–32. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.02.012

Von, B. M. T., Collier, R., and Suess, E. (1990). Magnesium adsorption and ion exchange in marine sediments: a multi-component model. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 3295–3313. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(90)90286-T

Wang, H. J., Liu, B. H., and Li, X. S. (2011). One-dimensional ZnO nanostructures: solution growth and functional properties. Nano Research 556–564.

Wang, A. H., Wang, Z. H., Liu, J. K., Xu, N. C., and Li, H. L. (2021a). The sr/ba ratio response to salinity in clastic sediments of the yangtze river delta. Chem. Geol. 559, 119923. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119923

Wang, J., Yin, M. L., Liu, J., Shen, C. C., Yu, T. L., Li, H. C., et al. (2021b). Geochemical and u-th isotopic insights on uranium enrichment in reservoir sediments. J. Hazard Mater 414, 125466. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125466

Wang, M. L., Qing, Y. H., Liao, Z. Y., Li, Y. F., Li, S., Lv, Z. X., et al. (2022). Reconstruction of paleoenvironment and paleoclimate of the neogene guantao formation in the liaodong sub-uplift of bohai bay basin in China by sedimentary geochemistry methods. Water (Basel) 14, 3915. doi:10.3390/w14233915

Wang, W. X., Zhao, X. L., Li, S. J., Zhang, L., Wang, X. L., and Zhang, X. Y. (2023). Palynoflora and climatic dynamics of the laizhou bay of bohai sea, North China Plain, since the late middle pleistocene. J. Palaeogeogr. 12, 278–295. doi:10.1016/j.jop.2023.03.001

Wang, C. L., Qiu, Y. F., Hao, Z., Wang, J. J., Zhang, C. C., Middelburg, J. J., et al. (2024). Global patterns of organic carbon transfer and accumulation across the land–ocean continuum constrained by radiocarbon data. Nat. Geosci. 17, 778–786. doi:10.1038/s41561-024-01476-4

Wei, H. Y. (2012). Productivity and redox proxies of palaeo-oceans: an overview of elementary geochemistry. Sediment. Geol. Tethyan Geol. 32, 76–88.

Wei, W., and Algeo, T. J. (2020). Elemental proxies for paleosalinity analysis of ancient shales and mudrocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 287, 341–366. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2019.06.034

Wendt, K. A., Li, X., Edwards, R. L., Cheng, H., and Spötl, C. (2021). Precise timing of mis 7 substages from the austrian alps. Clim. Past. 17, 1443–1454. doi:10.5194/cp-17-1443-2021

Weymer, B. A., Everett, M. E., Haroon, A., Jegen-Kulcsar, M., Micallef, A., Berndt, C., et al. (2022). The coastal transition zone is an underexplored frontier in hydrology and geoscience. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 323. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00655-8

Wu, S. Y., Liu, J., Chu, H. X., Feng, Y. C., Yin, M. L., and Pei, L. X. (2024a). Paleoenvironmental evolution and east asian monsoon records through three stages of paleochannels since the mid-pleistocene in the western bohai sea, north China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 656, 112603. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112603

Wu, S. Y., Liu, J., Chu, H. X., Bai, D. P., Feng, Y. C., Li, M. T., et al. (2024b). Identification of three stages of paleochannels and main source analysis beginning in the middle pleistocene in the western bohai sea in north China. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 296, 108601. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2023.108601

Xu, J., Shi, X. F., Liu, S. F., Liu, J. X., Shan, X., and Dong, Z. (2018). High-resolution sedimentary record of East Asian Monsoon during late Holocene: evidence from the Inner Shelf Mud Area of East China Sea. Adv. Mar. Sci. 36, 216–228. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6647.2018.02.007

Xu, Q. S., Wang, Y. S., Ma, L. C., Yue, Y., Meng, T., Bi, J. F., et al. (2023). Paleoclimate quantitative reconstruction and characteristics of continental red beds: a case study of the lower fourth sub-member of shahejie formation in the bonan sag. J. Pet. Explor Prod. Technol. 13, 1993–2014. doi:10.1007/s13202-023-01663-w

Xu, F. J., Zhang, X. L., Xu, J. W., Sun, Z. L., Yuan, S. Q., and Liu, X. T. (2025). Sea level and low-latitude climate control on sedimentary provenance and paleoenvironmental evolution in the central okinawa trough since 19 cal. Ka bp. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 658, 112621. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112621

Yan, K., Wang, C. L., Mischke, S., Wang, J. Y., Shen, L. J., Yu, X. C., et al. (2021). Major and trace-element geochemistry of late cretaceous clastic rocks in the jitai basin, southeast China. Sci. Rep. 11, 13846. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93125-8

Yao, Z. Q., Guo, Z. T., Xiao, G. Q., Wang, Q., Shi, X. F., and Wang, X. Y. (2012). Sedimentary history of the western bohai coastal plain since the late pliocene: implications on tectonic, climatic and sea-level changes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 54-55, 192–202. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.04.013

Yao, Z. Q., Shi, X. F., Li, X. Y., Liu, Y. G., Liu, J., Qiao, S. Q., et al. (2017). Sedimentary environment and paleo-tidal evolution of the eastern bohai sea, China since the last glaciation. Quat. Int. 440, 129–138. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.04.010

Yao, Z. Q., Shi, X. F., Liu, Y. G., Kandasamy, S., Qiao, S. Q., Li, X. Y., et al. (2020). Sea-level and climate signatures recorded in orbitally-forced continental margin deposits over the last 1 myr; new perspectives from the bohai sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 550, 109736. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109736

Yi, L., Yu, H. J., Ortiz, J. D., Xu, X. Y., Chen, S. L., Ge, J. Y., et al. (2012). Late quaternary linkage of sedimentary records to three astronomical rhythms and the asian monsoon, inferred from a coastal borehole in the south bohai sea, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 329-330, 101–117. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.02.020

Zhang, D. E., and Derbyshire, E. (1991). Historical records of climate change in China. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 551–554. doi:10.1016/0277-3791(91)90049-Z

Zhang, W. P., Sun, Y. F., Chen, W. W., Song, Y. P., and Zhang, J. K. (2019). Collapsibility, composition, and microfabric of the coastal zone loess around the bohai sea, China. Eng. Geol. 257, 105142. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.05.019