- 1Department of Biology, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, United States

- 2Earth and Environmental Sciences Area, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, United States

Enhanced weathering (EW) through the application of ground rock is a competitive carbon removal strategy. Adoption of this technology at a meaningful scale requires a systematic assessment of its long-term feasibility, especially with regard to soil quality from the application of rock amendments that contain varying levels of heavy metal (loid)s (HM) such as Cu, Ni, Cr, Co, and Pb. The potential accumulation of these metal (loid)s could be an unintended consequence of repeated large-scale EW applications, necessitating careful evaluation for use in croplands. This study explores the idea of using phytoremediation as a natural, low-cost means of remediating rock-amended soils. Specifically, we examined the ability of Nerium oleander and Salix alba species to remove HM from rock-amended soils in their tissues (i.e., leaves, stems, and roots). In this study, the relative abundance of HM accumulation in hyperaccumulator plants followed the order: Si > Rb > Cu > Sn > Cr > Cd > Pb > Ni > Mo > Co > As > Sb > Se > Cs. Our results indicate that HM accumulation in soils treated with rock were significantly below permissible limits set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Further, in reasonable amounts, some of these HM serve as essential micronutrients required by plants. In fact, we found increased growth and higher biomass for both plants under rock application than without. We further found a significant uptake of most HM in rock-amended soils planted with S. alba. Comparatively, uptake of certain HM like Ni, Mo, Cs, Pb and Cu was relatively higher in the roots of N. oleander. In contrast to N. oleander, S. alba accumulated higher levels of HM in its stems and leaves than in its roots. Interestingly, 31–35% weathering of metabasalt (applied rock) was observed across plant types over a 5-month period. Overall, we conclude that S. alba has a greater potential for phytoremediation in rock-amended soils, although both plants may be useful in remediating soils with varying levels and types of contamination.

1 Introduction

To keep planetary warming below 2 °C this century, there is an urgent need to implement carbon dioxide removal strategies (Shukla et al., 2022). In tandem, an alarming rate of topsoil loss and erosion has been observed around the world (Longbottom et al., 2022). This topsoil loss results in the loss of essential minerals and carbon from the soil, contributing to the already increasing rate of carbon dioxide (CO2) released into the air. Enhanced weathering (EW) has been suggested as an important approach that can not only remove CO2 from the atmosphere, but also improve soil health (Beerling et al., 2020; Renforth, 2012; Schuiling, and Krijgsman, 2006). In particular, EW works by accelerating the interactions between rock materials and CO2 to bind CO2 carbon permanently in the soil as minerals and/or increase alkalinity that will eventually runoff to the ocean.

There are several benefits to the application of enhanced weathering (EW), some of which include: 1) stabilizing soil pH, which benefits plants and reduces emissions of other greenhouse gases, 2) improving soil hydrology and releasing nutrients, which further stimulates biological carbon sequestration, and 3) increasing the alkalinity of natural waters, which amends ocean acidification (Beerling et al., 2018; Breunig et al., 2024; de Oliveira Garcia et al., 2020; Kantola et al., 2017). Although EW has many advantages, some of the mafic and ultramafic rocks used for EW (e.g., dunite and olivine) contain a high concentration of heavy metal (loid)s (HM), such as nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) (Alloway, 2012; Hartmann et al., 2013). However, HM concentrations from addition of ultramafic and basaltic rock materials can show tens of orders of magnitude variability based on the composition of the parent material (Kierczak et al., 2021; Suhrhoff, 2022). In a study by Dupla et al. (2023), HM accumulation was quantified across a range of rock sources, application rates, and national regulatory limits compiling legislation from China, Brazil, Canada, Germany and Russia. Their work suggested that rock application rates of 40 t ha−1 yr-1 would lead to Cu and Ni contents in soils to double after 40 years. In an experimental study, Renforth et al. (2015) showed that ∼99% of the Ni and Cr released from olivine weathering was retained in the soil for over 5 months. The results of the study imply that while the short-term impacts of HM release from rock-amended soils may be limited, longer-term accumulation may pose a serious environmental risk and need to be investigated. Pogge von Strandmann et al. (2022) reproduced the Renforth et al. (2015) experiments to evaluate the impact of temperatures on Ni and Cr retention in soils. Their work suggested that the accumulation of Cr and Ni in soils was an order of magnitude lower in colder temperatures (4 °C) than warmer climates (19 °C) due to slower dissolution rates. Contrastingly, Kelland et al. (2020) showed that amending a slightly acidic clay-loam soil with very large applications of 100 t ha−1 of basalt powder did not lead to elevated contents of nickel, copper or chromium in Sorghum. These and other studies have shown that rates of weathering and therefore, the rates of HM accumulation in soils depend on regional and local conditions including climate, soil properties as well as land and water management (Deng et al., 2023; Kabata-Pendias, 2010; Stolze et al., 2023). In support of enhanced weathering, it should be noted that all soils in their natural state contain a certain amount of HM (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Haque et al., 2020). Furthermore, in nutrient-poor environments, EW could be a long-term source of macronutrients (e.g., Ca, K, and P) and some of these same HM can act as micronutrients (e.g., B, Mo, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn, and Ni) required by plants (de Oliveira Garcia et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2021). In fact, several studies have noted agronomic and environmental co-benefits of enhanced weathering, including improved crop yields (e.g., Kelland et al., 2020; Skov et al., 2024; Vienne et al., 2022). Together, these studies suggest that benefits of EW cannot be overlooked but it may be important to assess and counter potential HM accumulation risk under different soil, climatic and agricultural contexts.

As a precautionary measure against potential HM pollution from EW, this study explores the idea of using phytoremediation plants in rock-amended soils as an integrated approach wherein plants enhance rock weathering while removing HM from soils. Phytoremediation is a safe, clean, and environmentally friendly approach that involves using bioenergy plants to prevent the accumulation and contamination of soils with HM (Ali et al., 2013; Haque et al., 2021; Mukherjee et al., 2024). Bioenergy plants used in phytoremediation are known as hyperaccumulator plants that have a high biomass production, and therefore, the ability to accumulate HM and remove their different concentrations from soils (Pulford and Watson, 2003). This study tested the ability of Nerium oleander and Salix alba species to remove HM from rock-amended soils. The choice of the plant species in this study is guided by the fact that each of the phytoremediation plants differ in their ability to uptake HM concentrations in each part (i.e., leaves, stems, and roots). Also, some of these species undergo annual dormancy at the onset of the winter season resulting in leaf drop. Therefore, by comparing two different species with different growing seasons and rooting depths, we will have the ability to predict HM accumulation in rock-amended soils. Additionally, given that these are ornamental plants, these plants are characterized by their ability to grow under different conditions. This implies that these plants don’t need any kind of specialized care (i.e., irrigation, nutrition, pesticides).

Nerium oleander, one of these phytoremediation plants, is a common fast-growing evergreen shrub that belongs to the family Apocynaceae. The shrub is a common drought-tolerant and fairly hardy landscaping plant (Kumar et al., 2017; Mackay et al., 2005). As a result, it is widely cultivated in the Mediterranean region for ornamental purposes. It can reach up to 4 m in height, although it is typically cut to keep a rounded smaller shape in parks, gardens, and along roadsides. Its leaves are short-stalked green or grey-green in color and range from about 10 to 20 cm long. One of the morphological and physico-chemical characteristics of Nerium oleander is that it has lanceolate leaves with high cuticle thickness (Abdalla et al., 2016; El-Taher et al., 2020). This implies that the plant can accumulate elements on the leaf surface largely from aerial sources and also by substratum (Aksoy and Öztürk, 1997; Seaward and Mashhour, 1991). Further, several studies have successfully shown the bio-accumulation of trace elements in N. oleander plant species (Ahmed et al., 2019; Aksoy and Öztürk, 1997; Palmieri et al., 2005; Seaward and Mashhour, 1991). Recent work has shown the effective ability of the N. oleander to accumulate HM such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and zinc (Zn) in their tissues (Ibrahim and El Afandi, 2020a; Ibrahim and El Afandi, 2020b).

The second plant under investigation, Salix alba (white willow), is notable for its ease of propagation, rapid growth, and tolerance of various soil conditions. Additionally, it is a productive group of plants for phytoremediation due to its ability to resprout after harvesting aboveground biomass. It has substantial transpiration rates and potential for producing energy biomass. Due to its capacity to absorb and resist heavy metal (loid)s, Salix species are suitable as HM phytoextractors. Salix is extremely good at phytoextraction of heavy metal pollution when compared to other plants (Berndes et al., 2004; Capuana, 2020; Sandil and Gowala, 2022; Pulford et al., 2002). Malik et al. (2020) observed the capability of Salix alba in remediating contaminated soil. In particular, their work suggested that S. alba has a huge economic value to offer eco-friendly machinery for removing HM from the soil as the plant is characterized by having a deep-root system as well as high biomass yields. Also, it has a high translocation rate from the root to the shoot (Greger and Landberg, 1999; Pulford and Watson, 2003).

However, these studies have been limited to studying the phytoremediation ability of N. oleander and S.alba in regions contaminated with air and soil pollution but not in rock-amended soils. Additionally, it is not clearly understood how these plants will behave in rock-amended soils with many different HM. Hence, the main objectives of this work are to: 1) quantify how much HM are released in rock-amended soils containing metabasalt and 2) examine the role of Nerium oleander and Salix alba species in capturing these HM in their tissues. Note that recent investigations have been diligent with monitoring HM concentrations during EW trials (e.g., Amann et al., 2020), some are focused on developing environmentally safe guidelines on applications (e.g., Flipkens et al., 2021), and yet others have shown these HM to remain within safe limits (Beerling et al., 2024; Vienne et al., 2022). Therefore, this work does not suggest that elevated HM concentrations are an inevitable outcome in all EW settings but explores the potential for a worst-case scenario in the event of such contamination occurring.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental setup

To test the impact of phytoremediation plants on HM uptake from rock-amended soils, a pot experiment was conducted at the greenhouse of Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi. The experiment was started on 16 January 2023, and concluded on 25 May 2023, spanning a duration of 129 days. A total of eight plants (two plant species N. oleander and S. alba) in four replicates (one control and three rock amendment) were planted in pots of 20–30 cm diameter. At the time of planting, all plants were approximately 3 years old. The pots were filled with a mixture of pot soil, and the rock powder was applied on the top 2 cm of the soil in three of the replicates. The pots were kept in the greenhouse under normal conditions (sunlight, temperature, and humidity) for the duration of the experiment. The greenhouse (located at 32.2994176° N latitude and −90.2103040° W longitude) is covered with glass and equipped with an air conditioning system to regulate temperature. During the experiment, the temperature inside the greenhouse was maintained between 18 and 22 °C, and the relative humidity ranged from 60% to 70%.

Irrigation water was applied to all pots weekly until mid-March, after which it was applied every 3 days to avoid the possibility of drought, biomass and nutrient losses, and the accumulation of solute near the surface (See Figure 1). Irrigation was conducted using a purification system to ensure that no heavy metals were introduced from this source. Fertilizers were not used in the experiment.

Figure 1. Experimental set up of (a) Nerium oleander and (b) Salix alba plants after application of the rock powder. .

Fresh biomass was analyzed, and samples of leaves, stems, roots, and soil were harvested at the end of the experiment. Both above-ground and below-ground parts were collected randomly, without selecting specific types of leaves, shoots, or roots to ensure a representative sampling of the entire plant structure for analysis. For root analyses, samples were collected from the entire volume of the pot, including both the top layer and lower horizons. After collection, samples were dried at temperatures ranging between 70 °C and 100 °C to assess dry matter yield. Plant tissues were not washed with water or any other agent prior to analysis; instead, soil particles adhering to plant tissues were removed by hand after oven drying. As a result, the HM concentrations reported in this study refer to total uptake, including both tissue and surface-adsorbed metals (Badr et al., 2012; Swaileh et al., 2001). Despite our best efforts, some residual soil particles may have remained, and therefore, our metal data may slightly overestimate actual uptake compared to protocols that include a root-washing step (Krishnamurti et al., 2015).

Plant samples were analyzed separately for heavy metals (e.g., Zn, Cd, Pb, Cr, Ni) and major nutrients (e.g., Mg, Si) to examine the ability of these two species to uptake different concentrations in their tissues.

2.1.1 Plant and soil analyses

The prepared samples (1 gm each) were digested using wet digestion with HNO3/H2 O2 (Jones et al., 1991). Following this procedure, the samples were filtered and run through ICP-MS. Previous studies have demonstrated that these techniques can provide sufficient information on plant uptake from contaminated soils in tissues of N. oleander (Abdullahi et al., 2021) and S. alba (Francis, 2017), and in soil (Ahmed et al., 2019).

2.1.2 Soil pH analysis

Soil pH is usually determined potentiometrically in the soil-water slurry system using an electronic pH meter (Mclean, 1982). Soil slurry was prepared by suspending 2 g soil in 2 mL distilled water. First, an electrode should be checked frequently to prevent residue buildup, which may affect the operation. The electrode should be protected in a way that prevents insertion to the very bottom of slurry vessels. Then, the electrode should be rinsed between each soil sample with a solution of soil and water (Eckert and Sims, 1995).

2.2 Applied rock characteristics

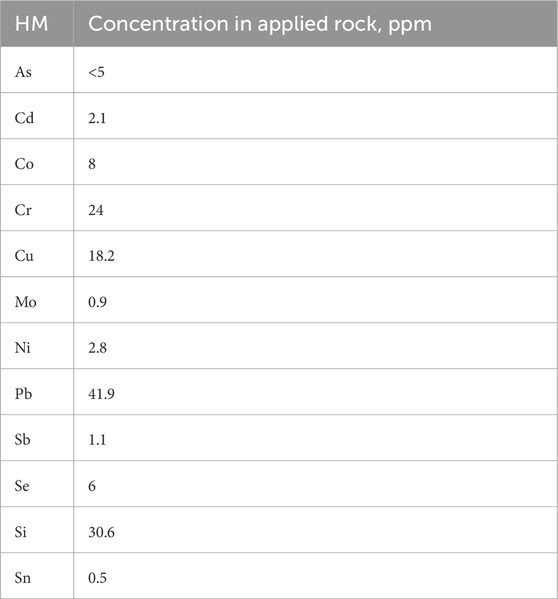

The rock applied to the top of the soil is a type of basalt (Lewis et al., 2021; Table 1). The rock is rich in magnesium which is about 1.72% MgO and these types of rocks are considered to be suitable for enhanced weathering because Mg can promote CO2 drawdown (Schuiling and Krijgsman, 2006). The amount of HM in the applied rock is given in Table 2.

2.3 Weathering and CO2 drawdown rates

We estimated rock weathering rates based on magnesium (Mg) balance following ten Berge et al. (2012). The amount of metabasalt weathered corresponds to the Mg accumulated in the soil (Mgsoil, g pot-1) and in the plant biomass (Mgplant, g pot-1) in excess of that amount in the control soil. The mass fraction of metabasalt weathered (Fweath) relative to metabasalt applied (Mgapplied_rock) is then written as:

where the subscripts of groups in brackets refer to rock treatment with metabasalt and control soil. Mg applied in the form of metabasalt is calculated in g pot-1.

2.4 Bioaccumulation and translocation factor calculation

Phytoremediation occurs through various mechanisms including uptake and accumulation of heavy metals, immobilization, breakdown, conversion to gas, and root-based uptake, with the specific mechanism depending on the plant species, contaminant type, and environmental conditions. For Nerium oleander and Salix alba, phytoremediation occurs primarily through root-based uptake. To assess metal accumulation efficiency in both species, we used two key indicators - the bioaccumulation factor (BCF) and the translocation factor (TF), calculated as follows:

where Cplant is the metal concentration in the plant (roots and shoots) and Csoil is the metal concentration in the soil after the rock experiment.

where Cshoots is the metal concentration in the shoots and Croots is the metal concentration in the roots after the rock addition. BCF is expressed as the ratio of metal in the plant to that in the soil, while TF is expressed as the ratio of the metal in the aerial parts to the roots.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Efficiency of N. oleander and S. alba in remediation of HM in metabasaltic soil

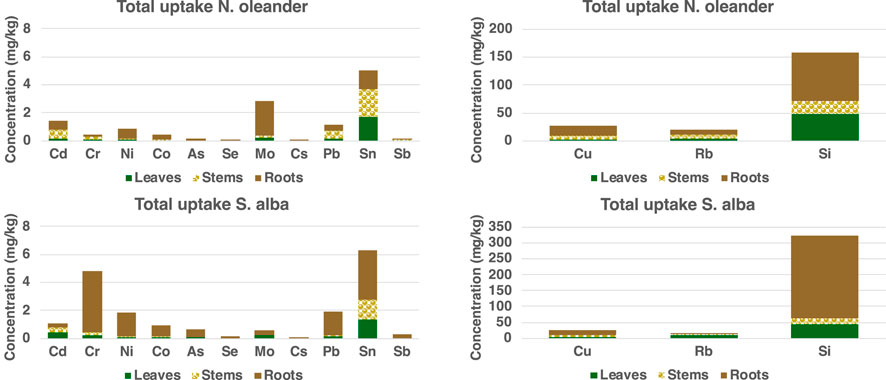

The order of relative abundance of HM accumulation in hyperaccumulator plants was found to be: Si > Rb > Cu > Sn > Cr > Cd > Pb > Ni > Mo > Co > As > Sb > Se > Cs. This section is organized to follow this order of HM abundance as well. To assess treatment effects, we conducted one-way ANOVAs comparing HM accumulation between control and rock-treated conditions. Since the control pot lacked replication, we assumed homogeneity of variance across all pots and used the pooled variance from the three treatment replicates as a proxy for the control’s variance. Given this limitation, we interpret the ANOVA results as exploratory rather than conclusive (Hurlbert, 1984). Out of all HM, only Cu, Ni, Mo, Co, and As had a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment groups for N. oleander. For S. alba, Rb, Sn, Cd, Mo, and Se showed significant differences (p < 0.05) between control and treatment groups.

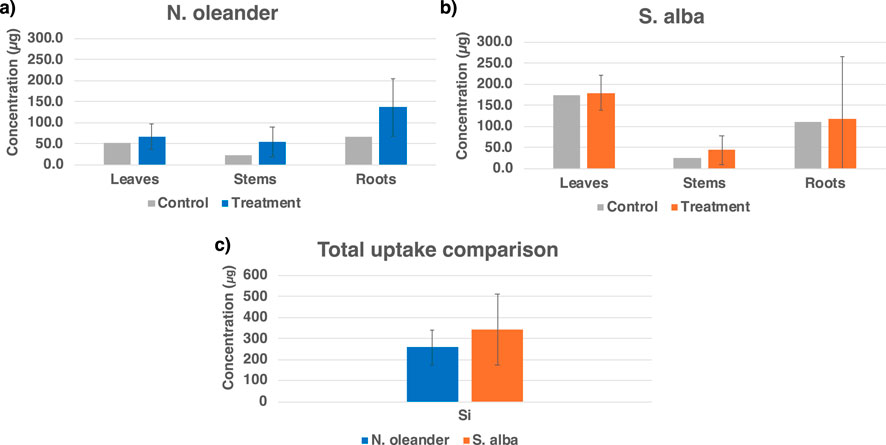

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the uptake of Si in N. oleander and S. alba in their tissues (leaves, stems, and roots) in control and rock-amended soils. Figure 2 shows that accumulation of Si is higher in all tissues of plants grown under rock-treated soils than under control across hyperaccumulator plant types, although the difference was insignificant at the 5% significance level. Interestingly, N. oleander roots showed a higher Si uptake than leaves, followed by stems. Since unwashed roots were analyzed, the measured Si uptake in roots may be overestimated due to adherent soil particles or mineral precipitates. In contrast, S. alba leaves showed a greater uptake than roots, followed by stems. Figure 2c further shows that S. alba had a higher overall Si uptake (341.5 μg, average under rock-treated soils) than N. oleander (258.2 μg, average under rock-treated soils). Weathering of alkaline silicate minerals used in enhanced rock weathering are expected to release significant amounts of Si. Si is a desired element for plant nutrition, especially for crops like sugarcane and rice (Haque et al., 2020).

Figure 2. Efficiency of (a) Nerium oleander and (b) Salix alba in taking up silica (Si) in different tissues, and (c) total Si uptake comparison for the hyperaccumulator plants.

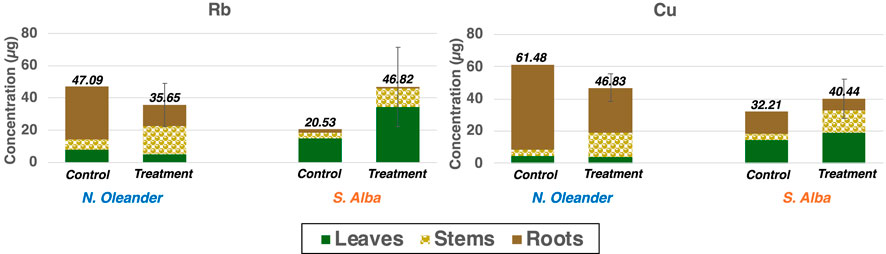

Accumulation of Cu and Rb in both plants show slightly different patterns than that of Si (Figure 3). Similar to Si, overall Rb and Cu uptake was found to be greater in S. alba under rock amendment than under control. In contrast, average concentration of Rb and Cu in the tissues of N. oleander was found to be greater in control than under rock-treated soils. However, for Rb, this average concentration is within 1 standard deviation of values reported in N. oleander tissues under rock-amended soils and the difference was found to be insignificant at the 5% significance level (p = 0.19). In contrast to Si and Rb, Cu uptake was found to be greater in N. oleander under control than in soils treated with metabasalt (p < 0.05). The reason for higher uptake under control conditions may be attributed to the fact that the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil is affected by many factors, including organic matter, cation exchange capacity and in particular, the pH which is affected by addition of rock amendments (Arora et al., 2018; Li and Shuman, 1996; Mayer et al., 2015; Mustafa and Khudair, 2023). Further, Cu uptake was found to be highest in the roots of N. oleander followed by stems and leaves. In comparison, Rb uptake was found to be greatest in the stems of N. oleander followed by roots and leaves. For both Rb and Cu, S. alba leaves showed a greater uptake than stems, followed by roots under rock amendment.

Figure 3. Efficiency of Nerium oleander and Salix alba in taking up Rb and Cu in different tissues under control versus rock-treated soils.

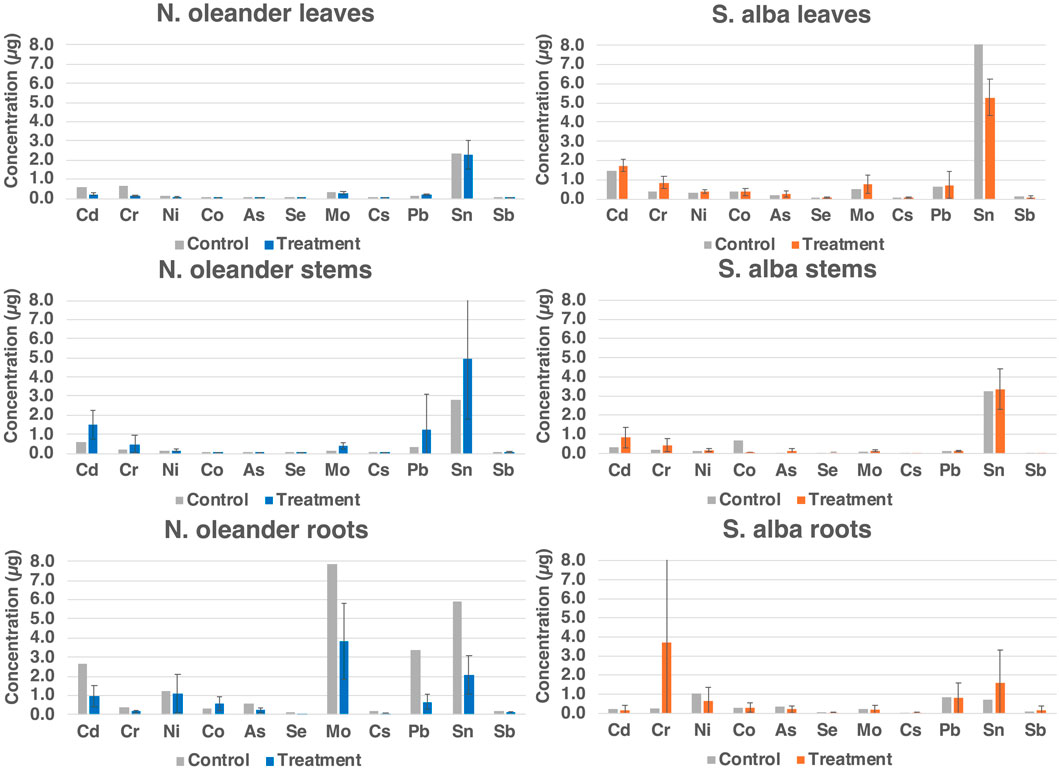

Figure 4 shows the capability of N. oleander to uptake the rest of the heavy metals (HM) in their tissues (leaves, stems, and roots) in control and rock-amended soils. Similar to Si and Cu, the highest uptake of HM was observed in roots, followed by stems and then leaves of N. oleander. These results corroborate previous research, where higher concentrations of HM have been observed in the roots of N. oleander, followed by stems and leaves (Franco et al., 2012; Franco et al., 2013; Ibrahim and El Afandi, 2020a; Ibrahim and El Afandi, 2020b). Further, previous studies have reported low transfer mobility (TF) of metals like Zn from roots to leaves of N. oleander, indicating higher accumulation in the roots of these plants (Ahmed et al., 2019). Figure 4 further illustrates that the uptake of HM in the leaves of N. oleander under rock treatment are typically higher than observed in the leaves of N. oleander under control (no rock amendment) except for Cd, Cr and Cs. However, for Ni, Co, Se, Mo and Sn, average uptake in the control group is within 1 standard deviation of values reported in N. oleander leaves under rock-amended soils. Surprisingly, we found that HM uptake in the roots of N. oleander was higher in control than rock-treated soils for most HM except Ni and Co. The reason for higher uptake under control conditions may be due to the influence of various factors affecting the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil, such as pH levels, which are known to be impacted by rock treatment (e.g., Arora et al., 2022; Beerling, 2017; Deng et al., 2023; Stolze et al., 2024). In stems of N. oleander, the accumulation of HM was always found to be greater in rock-treated soils than under control.

For S. alba, HM uptake in the leaves were greater in rock-treated soils than in untreated (control) soils except for Sn. In addition, average uptake of Co and Sb in the leaves of S. alba under control are within 1 standard deviation of values reported under rock-treated soils. Unlike N. oleander, the concentration of HM in the stems of S. alba were found to be greater in rock-treated soils than under control except for Co. However, for a few metals like, Cs, Pb and Sb, average concentrations in control are within 1 standard deviation of values reported in S. alba stems under rock-amended soils. Interestingly, the concentration of HM was always found to be greater in the roots of S. alba under rock-treated conditions than under control. In terms of total uptake in µg, the highest uptake of HM was observed in leaves, followed by stems and then roots of S. alba. The higher accumulation of HM in stems and leaves rather than roots observed in this study has been attributed to the fact that the TF values were >1 for all toxic ions in the senescent leaves of S. alba (Brkovic et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2020; Slaimi et al., 2021).

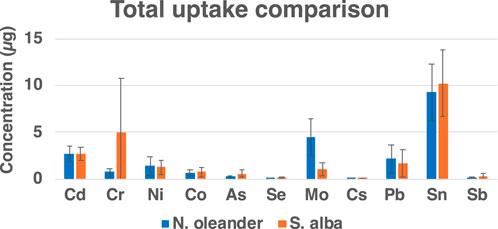

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the total uptake of HM by N. oleander and S. alba. An uptake greater than 1 µg of Cd, Ni, Mo, Pb and Sn was observed in rock-amended soils planted with N. oleander. Comparatively, lower concentrations of Mo and Pb were observed in tissues of S. alba planted in rock-amended soils than that observed in N. oleander tissues. However, a greater uptake of Cr and Sn was observed in rock-amended soils planted with S. alba. Overall, S. alba showed greater HM uptake in our study. However, we also note that there is a selective uptake of HM by both plants probably due to different solubilities in the soil and to specific species preference for different HM (e.g., Franco et al., 2012; Franco et al., 2013). Thus, both N. oleander and S. alba present a promising quality for reducing bioavailable metals from soils under EW application.

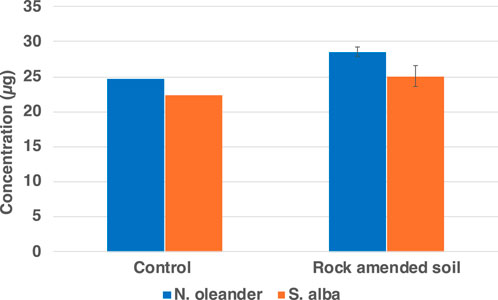

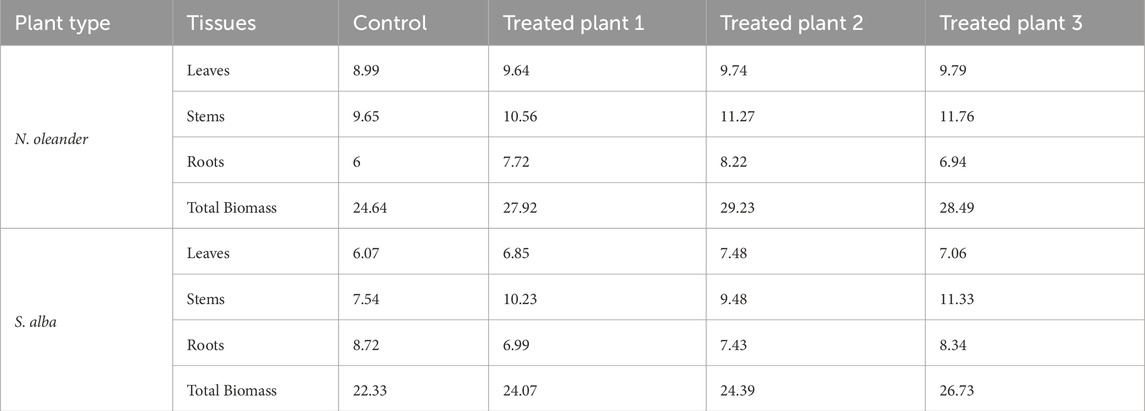

3.2 Plant growth and biomass

A higher biomass was also observed for both plants under rock application than without (Figure 6). Thus, rock addition resulted in higher plant growth under treatment as compared to the control. Further, the biomass of S. alba was observed to be slightly lower than that of N. oleander under both rock-amended and control conditions. To further assess the effect of rock amendment on plant growth, we calculated the average percent increase in biomass under treatment conditions relative to the control. This calculation showed that rock amendment resulted in the highest % increase in biomass in the roots of N. oleander, while the stems of S. alba exhibited the greatest % increase in biomass relative to the control (Table 3). Contrastingly, the root biomass of S. alba under rock treatment was slightly lower than observed under control conditions. A potential reason for this difference can be changes to Ca/Mg ratio in soils due to rock amendments. Other studies have shown significant impact of Ca/Mg ratio on Salix biomass (e.g., Mleczek et al., 2011). Further, studies have documented that plants can adjust their relative biomass allocation and distribution to organ systems (e.g., roots and shoots, reproduction and growth) when subjected to certain environmental conditions, such as presence of certain HM or organic compounds.

3.3 Bioaccumulation factor (BCF) and translocation factor (TF)

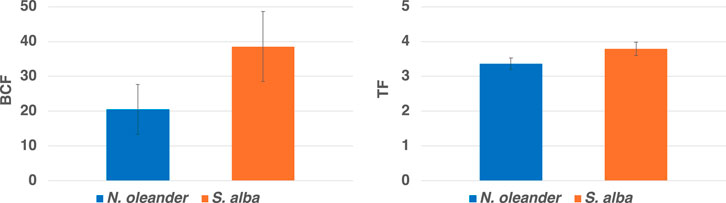

We further calculated BCF and TF indicators using Equations 2, 3, respectively, for both plants. BCF values greater than 1 indicate that the plant is an accumulator, and TF values greater than 1 indicate a high translocation of metals from plant roots to shoots. In our study, the BCF of S. alba (38.22) was found to be greater than that of N. oleander (20.51; See Figure 7), which further confirms higher bioaccumulation of HM in S. alba in rock-amended soils.

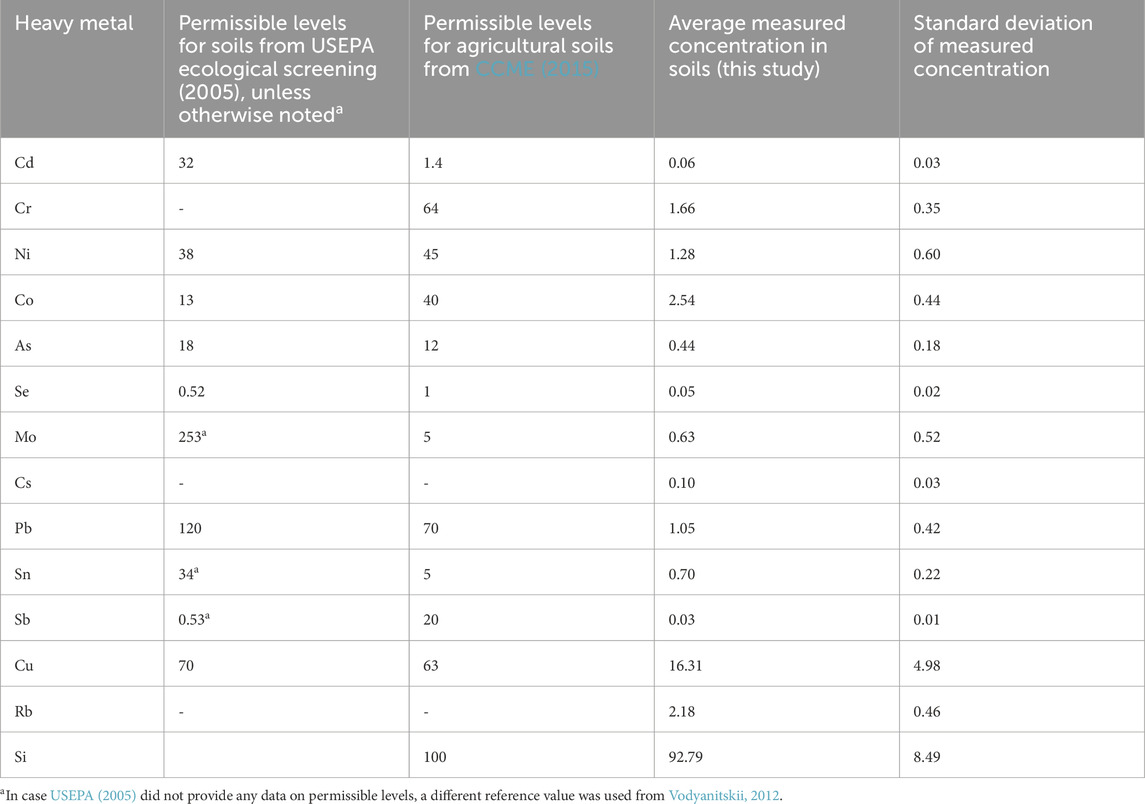

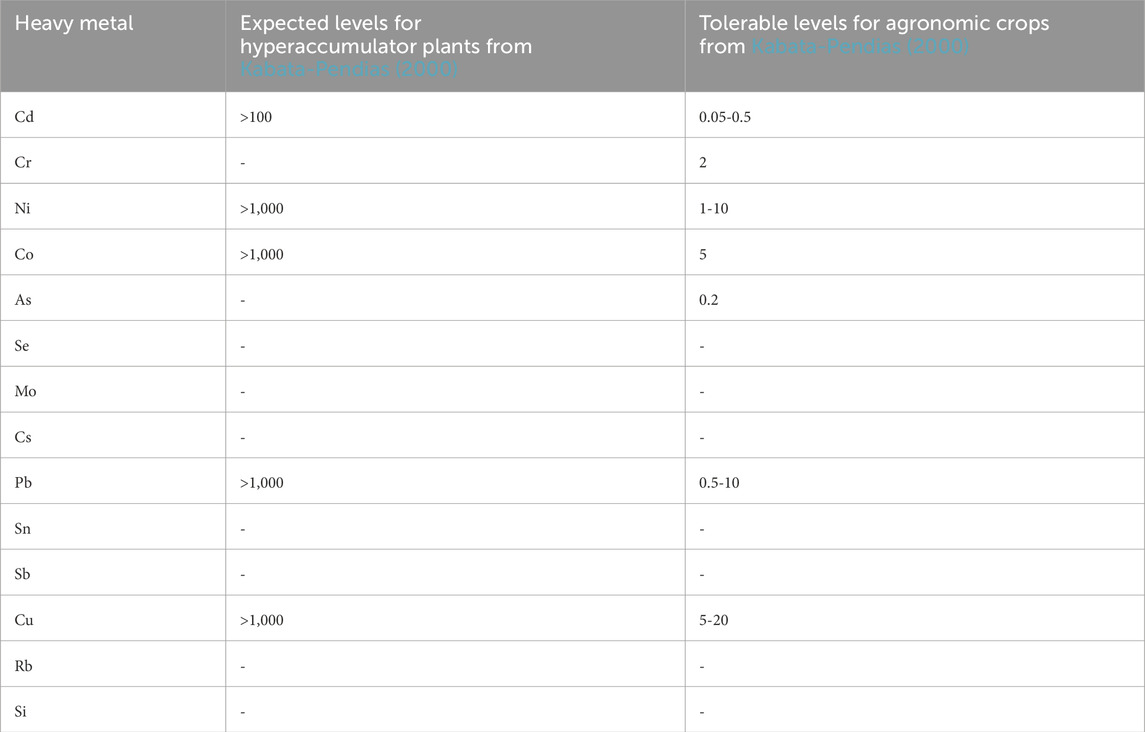

3.4 Allowable limits of HM in soils and plants

Since our results showed uptake of HM for both N. oleander and S. alba plants, we wanted to ascertain accumulation resulting from EW. Table 4 shows the permissible limits of HM in soils. Our results show that HM accumulation in soils from rock treatment were significantly lower than the allowable limits. Table 5 shows the expected levels of HM in hyperaccumulator plants and safe limits for agronomic crops. Figure 8 shows the measured concentration of HM in both hyperaccumulator plants. For all HM, the concentration in plant tissues were below permissible levels. Our results further indicate that concentration of most HM in hyperaccumulator plants are greater than that observed in soils. Interestingly, Co and Cs concentrations were always higher in soils than in plants. However, as previously noted, the concentrations of Co and Cs in soils were lower than the allowable limits (Table 4). The higher uptake of HM in plants signifies the efficacy of both plants in remediating soils contaminated with HM, particularly in rock amendment, a crucial factor in improving soil weathering.

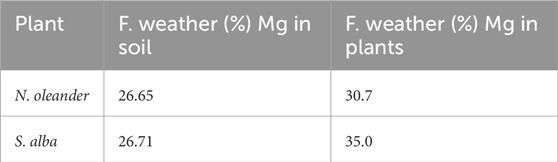

3.5 Estimation of weathering

Using Equation 1, we calculated the fraction of weathering observed in our 3-month experiment. We found ∼31% rock weathering in soils plotted with N. oleander and 35% in soils plotted with S. alba (Table 6).

Table 6. Estimation of rock weathering using Fraction weathering (Fweath%) calculation method based on Magnesium (Mg).

The weathering rate matches with previous experiments conducted under controlled conditions (Haque et al., 2019).

3.6 Analysis of pH and impact on HM release

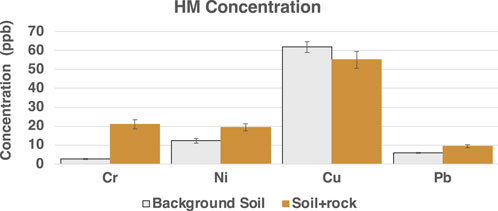

In comparing background soil conditions (before and after addition of rock), the results showed that the content of HM was higher in rock amendment than in control soil except in the case of Cu, which was higher in control soil compared to the rock treated soil (Figure 9). Potential reasons for higher background Cu concentrations could be the parent material of the soil or local conditions (e.g., pH) (e.g., Porter et al., 2004).

Figure 9. Concentration of select HM in control soil and soil after rock addition. The analyses was done after 1 month of rock addition without any plants.

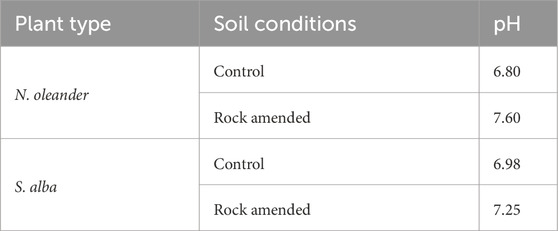

Furthermore, a significant uptake of Cu was observed under both plants in our study. Wu et al. (2011) have also shown that there may be a relationship between the pH of the soil and the uptake of HM in the plants because Cu and Mg content was higher in plants that grew in alkaline to medium acidity soil with pH ranging from 5.1 to 6.90. Table 7 shows soil pH measurements in control and rock-amended soils under both hyperaccumulator plants. In our study, pH of the control soil ranged between 6.8 and 6.98, while the measured pH of rock amendment soil ranged between 7.25 and 7.60 (Table 7).

Table 7. pH readings in control versus rock-amended soil in the presence of N. oleander and S. alba.

4 Summary and conclusion

Enhanced weathering through application of silicate rocks is a promising approach to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Although not applicable for all rock types or under all EW settings (see, e.g., Te Pas et al., 2023), practical concerns do exist about the accumulation of heavy metals in soils from application of large quantities of silicate rock. In this work, we explore the potential role of hyperaccumulator plants in modulating heavy metal fluxes resulting from EW application, especially in a worst-case scenario. Our results indicate that HM accumulation in rock-treated soils remained well below EPA-permissible limits. Further, only a few HM showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatment and control groups. However, these statistical outcomes should be considered exploratory given the lack of replication in the control pot.

Encouragingly, our work suggests a significant uptake of most HM in rock-amended soils planted with S. alba. In particular, significant remediation of Cr, Cd, Rb and Sn was observed in rock-amended soils planted with S. alba. Comparatively, uptake of HM such as Ni, Mo, Cs, Pb and Cu was relatively higher in the roots of N. oleander. In contrast to standard protocols, roots were not rinsed prior to analysis in this study; thus, the reported HM uptake reflects both internal tissue accumulation and surface-adsorbed metals. As suggested above, both plants accumulate HM in different tissues – with S. alba accumulating higher levels of HM in its stems and leaves, and N. oleander accumulating more in its roots. This is also confirmed by the higher TF of S. alba, which indicates a high translocation of metals from plant roots to shoots. Additionally, while both plants have BCF greater than 1, S. alba shows a higher BCF than N. oleander, further confirming greater bioaccumulation of HM in S. alba in rock-amended soils. We also found increased growth and higher biomass for both plants under rock application than without. In pots planted with hyperaccumulator species, significant weathering of applied rock (31–35%) was also observed over a 5-month period.

In conclusion, both N. oleander and S. alba present a promising quality for reducing bioavailable metals from soils under EW application. However, as this was a short-term study, our findings are insufficient to assess the long-term implications of heavy metal accumulation and plant uptake. Moreover, a comprehensive evaluation of organic matter-metal interactions was beyond the scope of this study. We therefore recommend future research using hyperaccumulator plants in EW field trials to ascertain concentration of HM, such as Cu, in heterogeneous field environments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

NI: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. ZS: Writing – original draft, Methodology. HZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology. SR: Writing – original draft, Methodology. SI: Writing – original draft, Methodology. BA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The authors would like to acknowledge the Visiting Faculty and the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) Program at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for funding. NI would also like to acknowledge funding from NSF HBCU EIR grant number 633259.

Acknowledgements

The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdalla, M. M., Eltahir, A. S., and El-Kamali, H. H. (2016). Comparative morph-anatomical leaf characters of Nerium oleander and Catharanthus roseus family (Apocynaceae). Eur. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 3 (3), 68–73.

Abdullahi, M. B., Animashaun, I. M., Garba, Y., Adamu, A., and Yisa, P. B. (2021). Phytoremediation of lead and chromium using sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) in contaminated soils of IBB university, lapai, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 25 (6), 1003–1007. doi:10.4314/jasem.v25i6.18

Ahmed, N. A., El-Shanhorey, N. A., Abdelsalam, I. Z., and Zahran, A. A. (2019). Bioremediation of heavy metals by using some shrubs in three different locations of Alexandria City.(B) Nerium oleander plant. Alexandria Sci. Exch. J. 40, 99–114. doi:10.21608/asejaiqjsae.2019.28703

Aksoy, A., and Öztürk, M. A. (1997). Nerium oleander L. as a biomonitor of lead and other heavy metal pollution in Mediterranean environments. Sci. Total Environ. 205 (2-3), 145–150. doi:10.1016/s0048-9697(97)00195-2

Ali, H., Khan, E., and Sajad, M. A. (2013). Phytoremediation of heavy metals—concepts and applications. Chemosphere 91 (7), 869–881. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.075

B. J. Alloway (2012). Heavy metals in soils: trace metals and metalloids in soils and their bioavailability (Springer Science and Business Media).

Amann, T., Hartmann, J., Struyf, E., de Oliveira Garcia, W., Fischer, E. K., Janssens, I., et al. (2020). Enhanced weathering and related element fluxes–a cropland mesocosm approach. Biogeosciences 17 (1), 103–119. doi:10.5194/bg-17-103-2020

Arora, B., Briggs, M. A., Zarnetske, J. P., Stegen, J., Gomez-Velez, J. D., Dwivedi, D., et al. (2022). Hot spots and hot moments in the critical zone: identification of and incorporation into reactive transport models. in Biogeochemistry of the critical zone. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 9–47.

Arora, B., Davis, J. A., Spycher, N. F., Dong, W., and Wainwright, H. M. (2018). Comparison of electrostatic and non-electrostatic models for U (VI) sorption on aquifer sediments. Groundwater 56 (1), 73–86. doi:10.1111/gwat.12551

Badr, N., Fawzy, M., and Al-Qahtani, K. M. (2012). Phytoremediation: an ecological solution to heavy-metal-polluted soil and evaluation of plant removal ability. World Appl. Sci. J. 16 (9), 1292–1301. doi:10.5829/idosi.wasj.2012.16.09.2882

Beerling, D. J. (2017). Enhanced rock weathering: biological climate change mitigation with co-benefits for food security? Biol. Lett. 13 (4), 20170149. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0149

Beerling, D. J., Leake, J. R., Long, S. P., Scholes, J. D., Ton, J., Nelson, P. N., et al. (2018). Farming with crops and rocks to address global climate, food and soil security. Nat. plants 4 (3), 138–147. doi:10.1038/s41477-018-0108-y

Beerling, D. J., Kantzas, E. P., Lomas, M. R., Wade, P., Eufrasio, R. M., Renforth, P., et al. (2020). Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 583 (7815), 242–248. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2448-9

Beerling, D. J., Epihov, D. Z., Kantola, I. B., Masters, M. D., Reershemius, T., Planavsky, N. J., et al. (2024). Enhanced weathering in the US corn belt delivers carbon removal with agronomic benefits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121 (9), e2319436121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2319436121

Berndes, G., Fredrikson, F., and Börjesson, P. (2004). Cadmium accumulation and Salix-based phytoextraction on arable land in Sweden. Agric. Ecosyst. and Environ. 103 (1), 207–223. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2003.09.013

Breunig, H. M., Fox, P., Domen, J., Kumar, R., Alves, R. J. E., Zhalnina, K., et al. (2024). Life cycle impact and cost analysis of quarry materials for land-based enhanced weathering in Northern California. J. Clean. Prod. 476, 143757. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143757

Brkovic, D., Bošković-Rakočević, L., Mladenovic, J., Simić, Z., Glišić, R., Grbović, F., et al. (2021). Metal bioaccumulation, translocation and phytoremediation potential of some woody species at mine tailings.

Capuana, M. (2020). A review of the performance of woody and herbaceous ornamental plants for phytoremediation in urban areas. iForest-Biogeosciences For. 13 (2), 139–151. doi:10.3832/ifor3242-013

CCME (2015). Canadian soil quality guidelines for the protection of environmental and human health: nickel. Canadian environmental quality guidelines, 1999. Winnipeg: Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment.

de Oliveira Garcia, W., Amann, T., Hartmann, J., Karstens, K., Popp, A., Boysen, L. R., et al. (2020). Impacts of enhanced weathering on biomass production for negative emission technologies and soil hydrology. Biogeosciences 17 (7), 2107–2133. doi:10.5194/bg-17-2107-2020

Deng, H., Sonnenthal, E., Arora, B., Breunig, H., Brodie, E., Kleber, M., et al. (2023). The environmental controls on efficiency of enhanced rock weathering in soils. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 9765. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-36113-4

Dupla, X., Möller, B., Baveye, P. C., and Grand, S. (2023). Potential accumulation of toxic trace elements in soils during enhanced rock weathering. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 74 (1), e13343. doi:10.1111/ejss.13343

Dwivedi, D., Steefel, C. I., Arora, B., Banfield, J., Bargar, J., Boyanov, M. I., et al. (2022). From legacy contamination to watershed systems science: a review of scientific insights and technologies developed through DOE-supported research in water and energy security. Environmental Research Letters 17 (4), 043004.

Eckert, D., and Sims, J. T. (1995). Recommended soil pH and lime requirement tests. Recommended soil testing procedures for the northeastern United States. Northeast Reg. Bull. 493, 11–16.

El-Taher, A. M., Gendy, A. E. N. G. E., Alkahtani, J., Elshamy, A. I., and Abd-ElGawad, A. M. (2020). Taxonomic implication of integrated chemical, morphological, and anatomical attributes of leaves of eight Apocynaceae taxa. Diversity 12 (9), 334. doi:10.3390/d12090334

Flipkens, G., Blust, R., and Town, R. M. (2021). Deriving nickel (Ni (II)) and chromium (Cr (III)) based environmentally safe olivine guidelines for coastal enhanced silicate weathering. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 55 (18), 12362–12371. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c02974

Francis, E. (2017). Phytoremediation potentials of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Asteraceae on contaminated soils of abandoned dumpsites. Int. J. Sci. and Eng. Res. 8 (1), 1751–17157.

Franco, A., Rufo, L., and de la Fuente, V. (2012). Metal concentration and distribution in plant tissues of Nerium oleander (Apocynaceae, Plantae) from extremely acidic and less extremely acidic water courses in the Río Tinto area (Huelva, Spain). Ecol. Eng. 47, 87–91. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.06.024

Franco, A., Rufo, L., Zuluaga, J., and de la Fuente, V. (2013). Metal uptake and distribution in cultured seedlings of Nerium oleander L. (Apocynaceae) from the río tinto (Huelva, Spain). Biol. trace Elem. Res. 155, 82–92. doi:10.1007/s12011-013-9761-1

Greger, M., and Landberg, T. (1999). Use of willow in phytoextraction. Int. J. phytoremediation 1 (2), 115–123. doi:10.1080/15226519908500010

Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Dutta, A., Thimmanagari, M., and Chiang, Y. W. (2019). Co-benefits of wollastonite weathering in agriculture: CO2 sequestration and promoted plant growth. ACS omega 4 (1), 1425–1433. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b02477

Haque, F., Chiang, Y. W., and Santos, R. M. (2020). Risk assessment of Ni, Cr, and Si release from alkaline minerals during enhanced weathering. Open Agric. 5 (1), 166–175. doi:10.1515/opag-2020-0016

Haque, M., Biswas, K., and Sinha, S. N. (2021). Phytoremediation strategies of some plants under heavy metal stress. Plant stress physiol.doi:10.5772/intechopen.94406

Hartmann, J., West, A. J., Renforth, P., Köhler, P., De La Rocha, C. L., Wolf-Gladrow, D. A., et al. (2013). Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Rev. Geophys. 51 (2), 113–149. doi:10.1002/rog.20004

Hurlbert, S. H. (1984). Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments Ecol. Monogr. 54, 187–211.

Ibrahim, N., and El Afandi, G. (2020a). Evaluation of the phytoremediation uptake model for predicting heavy metals (Pb, Cd, and Zn) from the soil using Nerium oleander L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (30), 38120–38133. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-09657-5

Ibrahim, N., and El Afandi, G. (2020b). Phytoremediation uptake model of heavy metals (Pb, Cd and Zn) in soil using Nerium oleander. Heliyon 6 (7), e04445. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04445

Jones, J. B., Wolf, J. B., and Mills, H. A. (1991). Plant analysis handbook. Athens, GA: Micro-Macro Pub. Inc., 30–34.

Kantola, I. B., Masters, M. D., Beerling, D. J., Long, S. P., and DeLucia, E. H. (2017). Potential of global croplands and bioenergy crops for climate change mitigation through deployment for enhanced weathering. Biol. Lett. 13 (4), 20160714. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0714

Kelland, M. E., Wade, P. W., Lewis, A. L., Taylor, L. L., Sarkar, B., Andrews, M. G., et al. (2020). Increas ed yield and CO2 sequestration potential with the C4 cereal Sorghum bicolor cultivated in basaltic rock dust-amended agricultural soil. Glob. Change Biol. 26 (6), 3658–3676. doi:10.1111/gcb.15089

Kierczak, J., Pietranik, A., and Pędziwiatr, A. (2021). Ultramafic geoecosystems as a natural source of Ni, Cr, and Co to the environment: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142620. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142620

Krishnamurti, G. S., Subashchandrabose, S. R., Megharaj, M., and Naidu, R. (2015). Assessment of bioavailability of heavy metal pollutants using soil isolates of Chlorella sp. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 8826–8832. doi:10.1007/s11356-013-1799-2

Kumar, D., Al Hassan, M., Naranjo, M. A., Agrawal, V., Boscaiu, M., and Vicente, O. (2017). Effects of salinity and drought on growth, ionic relations, compatible solutes and activation of antioxidant systems in oleander (Nerium oleander L.). Plos one 12 (9), e0185017. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185017

Lewis, A. L., Sarkar, B., Wade, P., Kemp, S. J., Hodson, M. E., Taylor, L. L., et al. (2021). Effects of mineralogy, chemistry and physical properties of basalts on carbon capture potential and plant-nutrient element release via enhanced weathering. Appl. Geochem. 132, 105023. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2021.105023

Li, Z., and Shuman, L. M. (1996). Heavy metal movement in metal-contaminated soil profiles. Soil Sci. 161 (10), 656–666. doi:10.1097/00010694-199610000-00003

Longbottom, T., Wahab, L., Min, K., Jurusik, A., Moreland, K., Dolui, M., et al. (2022). What's soil got to Do with climate change? GSA Today 32 (5), 4–10. doi:10.1130/gsatg519a.1

Mackay, W. A., Arnold, M. A., and Parsons, J. M. (2005). Nerium oleander L. `cranberry cooler', `grenadine glace', `pink lemonade', `peppermint Parfait', `raspberry Sherbet' and `Petite Peaches and Cream'. HortScience 40 (1), 265–268. doi:10.21273/hortsci.40.1.265

Malik, J. A., Wani, A. A., Wani, K. A., and Bhat, M. A. (2020). “Role of white willow (Salix alba L.) for cleaning up the toxic metal pollution,” in Bioremediation and biotechnology: sustainable approaches to pollution degradation, 257–268.

Mayer, K. U., Alt-Epping, P., Jacques, D., Arora, B., and Steefel, C. I. (2015). Benchmark problems for reactive transport modeling of the generation and attenuation of acid rock drainage. Comput. Geosci. 19, 599–611. doi:10.1007/s10596-015-9476-9

McLean, E. O. (1982). Soil pH and lime requirement. Methods soil analysis Part 2 Chem. Microbiol. Prop. 9, 199–224. doi:10.2134/agronmonogr9.2.2ed.c12

Mleczek, M., Kozłowska, M., Kaczmarek, Z., Magdziak, Z., and Goliński, P. (2011). Cadmium and lead uptake by Salix viminalis under modified Ca/Mg ratio. Ecotoxicology 20, 158–165. doi:10.1007/s10646-010-0567-z

Mukherjee, P., Dutta, J., Roy, M., Thakur, T. K., and Mitra, A. (2024). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial secondary metabolites in augmenting heavy metal (loid) phytoremediation: an integrated green in situ ecorestorative technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (44), 55851–55894. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-34706-8

Mustafa, M. K., and Khudair, A. F. (2023). Evaluation of the efficiency of Nerium oleander in the phytoremediation of lead pollution by using humic acid. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1213 (1), 012110. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1213/1/012110

Palmieri, R. M., La Pera, L., Di Bella, G., and Dugo, G. (2005). Simultaneous determination of Cd (II), Cu (II), Pb (II) and Zn (II) by derivative stripping chronopotentiometry in Pittosporum tobira leaves: a measurement of local atmospheric pollution in Messina (Sicily, Italy). Chemosphere 59 (8), 1161–1168. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.066

Pogge von Strandmann, P. A., Tooley, C., Mulders, J. J., and Renforth, P. (2022). The dissolution of olivine added to soil at 4 °C: implications for enhanced weathering in cold regions. Front. Clim. 4, 827698. doi:10.3389/fclim.2022.827698

Porter, G. S., Bajita-Locke, J. B., Hue, N. V., and Strand, D. (2004). Manganese solubility and phytotoxicity affected by soil moisture, oxygen levels, and green manure additions. Commun. soil Sci. plant analysis 35 (1-2), 99–116. doi:10.1081/css-120027637

Pulford, I. D., and Watson, C. (2003). Phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated land by trees—a review. Environ. Int. 29 (4), 529–540. doi:10.1016/s0160-4120(02)00152-6

Pulford, I. D., Riddell-Black, D., and Stewart, C. (2002). Heavy metal uptake by willow clones from sewage sludge-treated soil: the potential for phytoremediation. Int. J. phytoremediation 4 (1), 59–72. doi:10.1080/15226510208500073

Renforth, P. (2012). The potential of enhanced weathering in the UK. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 10, 229–243. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.06.011

Renforth, P., von Strandmann, P. P., and Henderson, G. M. (2015). The dissolution of olivine added to soil: implications for enhanced weathering. Appl. Geochem. 61, 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2015.05.016

Sandil, S., and Gowala, N. (2022). “Willows: cost-effective tools for bioremediation of contaminated soils,” in Advances in bioremediation and phytoremediation for sustainable soil management: principles, monitoring and remediation (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 183–202.

Schuiling, R. D., and Krijgsman, P. (2006). Enhanced weathering: an effective and cheap tool to sequester CO2. Clim. Change 74 (1-3), 349–354. doi:10.1007/s10584-005-3485-y

Seaward, M. R. D., and Mashhour, M. A. (1991). Oleander (Nerium oleander L.) as a monitor of heavy metal pollution. Urban Ecol., 48–61. doi:10.1016/0169-2046(91)90042-S

Shukla, P. R., Skea, J., and Slade, R. (2022). IPCC, 2022: climate change 2022: mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skov, K., Wardman, J., Healey, M., McBride, A., Bierowiec, T., Cooper, J., et al. (2024). Initial agronomic benefits of enhanced weathering using basalt: a study of spring oat in a temperate climate. Plos one 19 (3), e0295031. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0295031

Slaimi, R., Abassi, M., and Béjaoui, Z. (2021). Assessment of Casuarina glauca as biofiltration model of secondary treated urban wastewater: effect on growth performances and heavy metals tolerance. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193 (10), 653. doi:10.1007/s10661-021-09438-8

Stolze, L., Arora, B., Dwivedi, D., Steefel, C., Li, Z., Carrero, S., et al. (2023). Aerobic respiration controls on shale weathering. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 340, 172–188.

Stolze, L., Arora, B., Dwivedi, D., Steefel, C. I., Bandai, T., Wu, Y., et al. (2024). Climate forcing controls on carbon terrestrial fluxes during shale weathering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121 (27), e2400230121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2400230121

Suhrhoff, T. J. (2022). Phytoprevention of heavy metal contamination from terrestrial enhanced weathering: can plants save the day? Front. Clim. 3, 820204. doi:10.3389/fclim.2021.820204

Swaileh, K. M., Rabay'a, N., Salim, R., Ezzughayyar, A., and Rabbo, A. A. (2001). Concentrations of heavy metals in roadside soils, plants, and landsnails from the West Bank, Palestine. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 36 (5), 765–778. doi:10.1081/ese-100103759

Te Pas, E. E., Hagens, M., and Comans, R. N. (2023). Assessment of the enhanced weathering potential of different silicate minerals to improve soil quality and sequester CO2. Front. Clim. 4, 954064. doi:10.3389/fclim.2022.954064

Ten Berge, H. F., Van der Meer, H. G., Steenhuizen, J. W., Goedhart, P. W., Knops, P., and Verhagen, J. (2012). Olivine weathering in soil, and its effects on growth and nutrient uptake in ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.): a pot experiment. PLoS One 7, e42098. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042098

USEPA (2005). Ecological soil screening levels for antimony interim final OSWER directive 9285.7-61. U.S. environmental protection agency office of solid waste and emergency response, 1200 Pennsylvania avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20460.

Vienne, A., Poblador, S., Portillo-Estrada, M., Hartmann, J., Ijiehon, S., Wade, P., et al. (2022). Enhanced weathering using basalt rock powder: carbon sequestration, co-benefits and risks in a mesocosm study with Solanum tuberosum. Front. Clim. 4, 869456. doi:10.3389/fclim.2022.869456

Vodyanitskii, Y. N. (2012). Standards for the contents of heavy metals and metalloids in soils. Eurasian soil Sci. 45, 321–328. doi:10.1134/s1064229312030131

Keywords: carbon dioxide removal (CDR), enhanced rock weathering, metabasalt weathering, plant based remediation, metal uptake in plants, soil contamination, Cu, Ni

Citation: Ibrahim N, Smith Z, Zhang H, Roy SC, Islam SM and Arora B (2025) Phytoremediation potential of Nerium oleander and Salix alba for heavy metal removal in rock-amended soils: a natural and cost-effective approach. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1555232. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1555232

Received: 03 January 2025; Accepted: 21 October 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Craig Lundstrom, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Ibrahim, Smith, Zhang, Roy, Islam and Arora. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naira Ibrahim, bmFpcmEuYS5pYnJhaGltQGpzdW1zLmVkdQ==; Bhavna Arora, YmFyb3JhQGxibC5nb3Y=

Naira Ibrahim

Naira Ibrahim Zavier Smith1

Zavier Smith1 Bhavna Arora

Bhavna Arora