- 1Institute of Natural Resources Survey, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, China

- 2Faculty of Earth Resources, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, China

- 3Western Mining Group Co., Ltd., Geermu, China

The Lalinggaolihe mining area, situated in the southeastern Qimantag Mountain within the East Kunlun Orogen, hosts skarn-type Fe–Cu–Zn polymetallic deposits and is characterized by widespread intrusive rocks. LA-ICP-MS zircon U–Pb dating indicates that monzogranites in the northern part of the mining area yielded weighted mean ages of 216.22 ± 0.96 and 215.3 ± 2.1 Ma, whereas monzogranites, granodiorites, and dark diorites in the southern part yielded weighted mean ages of 415.8 ± 1.3, 417.1 ± 2.8, 416.7 ± 1.9, 414.6 ± 1.2 Ma. The northern and southern intrusions were formed during the Early Devonian and Late Triassic, respectively. The northern monzogranites exhibit high SiO2 (75.72%–77.36%), high alkali (K2O+ Na2O = 7.51%–8.39%), low CaO (0.58%–1.15%) and MgO (0.20%–0.26%) contents. They are enriched in light rare earth elements (LREE), depleted in Sr, U, and Eu, and display elevated TFeO (>1.0%), high TFeO/MgO ratios (>1), and high crystallization temperatures (811 °C), all consistent with A-type granite characteristics. Contrastingly, the southern monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites have aluminum saturation indices (A/CNK) ranging from 0.82 to 1.09, classifying them as metaluminous to weakly peraluminous. These rocks belong to the high-potassium calc-alkaline series and are depleted in Nb, Ta, U, and Hf and are enriched in LREE. They contain minor amphibole, with TZr (closure temperatures for zircon) ranging from 739 °C to 746 °C for the monzogranites and granodiorites, and 724 °C for the diorites, characteristics consistent with I-type granites. Zircon Hf isotopic results reveal that the northern monzogranites have εHf(t) values ranging from −4.17 to −1.2, whereas the southern monzogranites, granodiorites, and dark diorites exhibit εHf(t) values ranging from −3.54 to 1.10, −4.3 to −0.27, and −2.86 to −1.16, respectively. These predominantly negative εHf(t) values suggest that the magmas were primarily derived from the partial melting of ancient crustal materials, with potential mixing of mantle-derived components. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the northern and southern intrusions formed during the post-collisional extensional stage of the Early Devonian and the collisional to post-collisional stage of the Late Triassic, respectively. These intrusions likely originated from the underplating of mantle-derived magmas mixed with crustal materials, with Fe polymetallic mineralization resulting from crust–mantle material exchange.

1 Introduction

Granite intrusions play a crucial role in the formation of various economically significant skarn type polymetallic deposits worldwide. The heat, fluids, and metals they release can significantly alter the surrounding rock and lead to extensive mineralization (Einaudi et al., 1981). Therefore, understanding the genesis, evolution, and spatiotemporal relationship between these intrusive bodies and ore bodies is crucial for establishing mineralization models and exploration criteria.

Multiple large and medium-sized skarn type iron copper polymetallic deposits are distributed in the Qimantag area of the East Kunlun Mountains in Qinghai Province, and their mineralizations are closely related to granite bodies (Zhu, 2020; Chen et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013a; Bai et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2018). The Lalinggaolihe deposit is a newly discovered medium-sized iron copper polymetallic deposit in the region in recent years. Previous work believed that it belongs to the skarn type iron polymetallic deposit, and the mineralization is closely related to the intrusive rocks in the mining area. Although some scholars have conducted relevant researchs on the tectonic background of the Lalinggaolihe area and the geological characteristics of the deposit (Jing, 2013; Ma et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017), there have been no reports on the formation age, petrogenesis,and tectonic environment of intrusive rocks closely related to the genesis of the deposit, which greatly restricts the understanding of the geodynamic settings and genesis of the deposit. This article conducts petrology, geochemistry, zircon U-Pb geochronology, and Hf isotope studies on the main intrusive rock bodies exposed in the Lalinggaolihe mining area based on the observation of their geological characteristics. The aim is to explore their zircon crystallization ages, source area properties, genesis, and geodynamic settings, and further investigate their relationship with iron polymetallic mineralization. This research results not only help to understand the geological evolution history of the East Kunlun region, but also has important significance for understanding the genesis of iron polymetallic deposits in the Lalinggaolihe area.

2 Geological background and deposit geology

2.1 Geological setting of the region and ore deposits

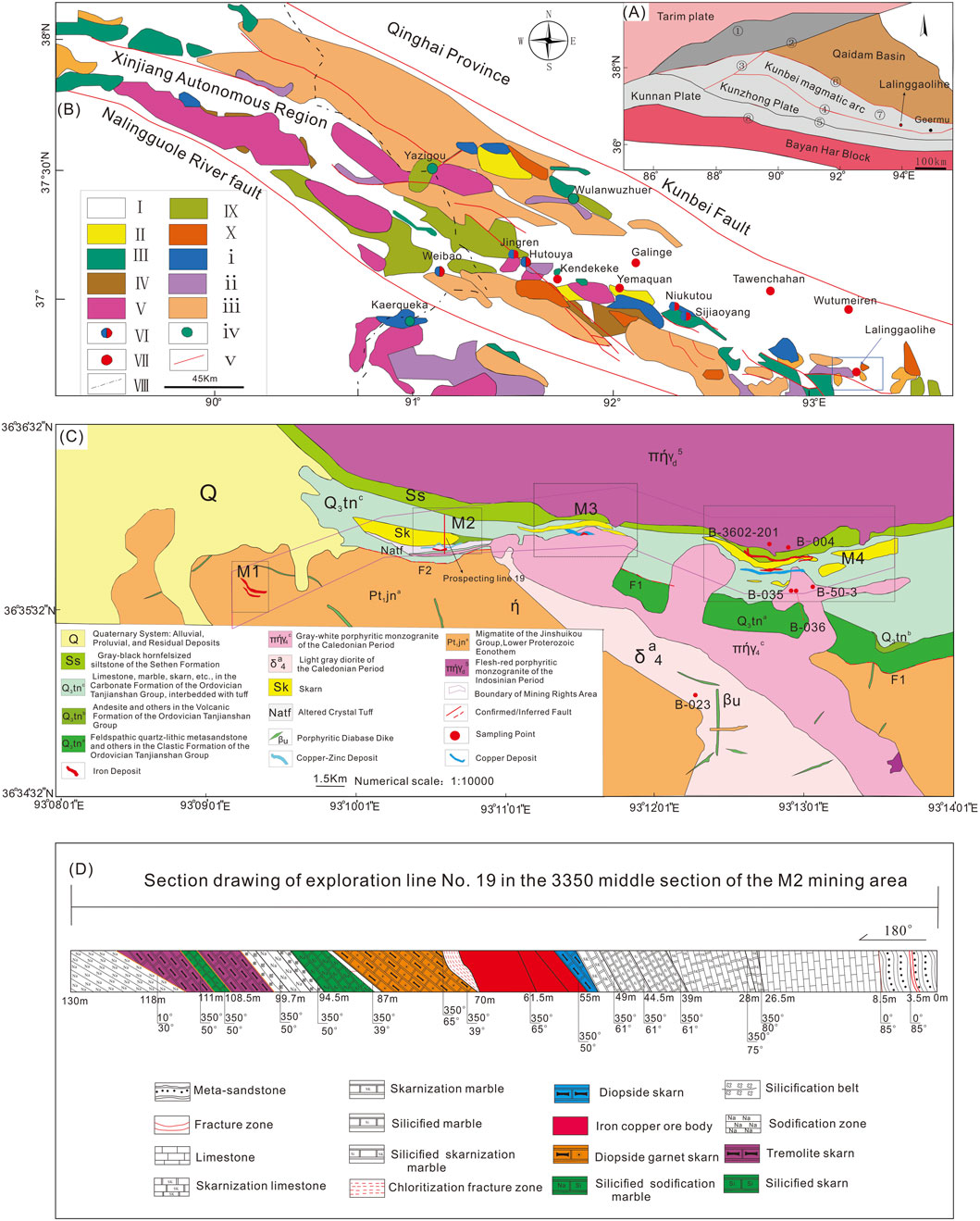

The Qimantag area is located in the western part of the East Kunlun orogenic belt and represents an important polymetallic mineral base in western China (Gao et al., 2017). To the north, it is separated from the Tarim microplate by the Altyn Fault, and to the south, it is connected with the Bayan Har Block by the Kunnan Fault. To the northeast, it is adjacent to the Qaidam massif via the Kunbei Fault. With the Nalingguole River Fault and Kunzhong Fault as boundaries, this area can be further divided into the Kunbei magmatic arc (the area between the Kunbei Fault and the Nalingguole River Fault), Kunzhong terrane, and Kunnan terrane (Figure 1A). The polymetallic deposits in the Qimantag area are mainly concentrated in the Kunbei magmatic arc. The mineralization belt of the mining area belongs to the Qimantag–Dulan Fe–Cu–Zn–W–Sn–Bi–Au–Mo metallogenic subbelt of Kunlun Metallogenic Province and the East Kunlun Metallogenic Belt. The main deposit types are skarn type, followed by magmatic hydrothermal and hydrothermal sedimentary types, as represented by the Hutouya, Sijiaoyang–Niukutou, Galinge, Tawenchahan, and Yemaquan deposits (Song et al., 2016). From oldest to youngest, the regional strata consist of the metamorphic basement of the Jinshuikou rock group (Pt1Jn) of the Lower Proterozoic Era, intermediate-basic volcanic and clastic rocks interbedded with carbonate rocks of the Early Paleozoic Era, limestone interbedded with clastic rocks of the Late Paleozoic Era, and intermediate-felsic volcanic rocks of the Mesozoic Era. Among them, the early Paleozoic clastic rocks interbedded with carbonate rocks, and the late Paleozoic limestone interbedded with clastic rocks are the main ore-bearing host lithology of the deposits in the area. The intrusive rocks are mainly intermediate-acid intrusive rocks formed during the Caledonian and Indosinian periods (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Comprehensive geological map of the study area. (A,B) Geodetic structure location map; (C) Regional stratigraphic distribution map; (D) Partial profile map of the ore body in the mining area (section drawing of exploration line No. 19 in the 3350 middle section of the M2 mining area) I: Quaternary System; II: Carboniferous System; III: Ordovician–Silurian Systems; IV: Neoproterozoic Erathem; V: Triassic granite; VI: Lead–Zinc Deposit; VII: Iron deposit; VIII: Province boundary; IX: Triassic System; X: Devonian System; i: Cambrian System; ii: Palaeo-Mesoproterozoic Erathem; iii: Palaeozoic granite; iv: Copper–Molybdenum deposit; v: Fault; ①:Altun (Altyn) Orogenic Belt; ②:Altun Fault; ③:Baiganhe Fault; ④:Nalingguole River Fault; ⑤:Kunzhong Fault; ⑥:Kunbei Fault; ⑦:Kunbei Plate; ⑧:Kunnan Fault.

The Lalinggaolihe mining area is located in the southeast of the Kunbei magmatic arc. The exposed strata in the mining area, from oldest to youngest, include the Jinshuikou Group of Lower Proterozoic (Pt1Jn), Tanjianshan Group of Ordovician (O3tn), Saishiteng Formation of Silurian (Ss), and Quaternary overburden (Figure 1C). The lower rock formation (Pt1jna) of the Jinshuikou Group is mainly distributed in the southwest of the mining area. The lithology is mainly migmatite, locally interbedded with dark gray mica quartz schist and black plagioclase breccia. The Tanjianshan Group is divided into three lithological sections. The lower section comprises clastic rocks, including quartz sand, conglomerate, and quartz sandstone interbedded with dacite tuff. The middle section is dominated by volcanic rocks, mainly composed of andesite. The upper member consists of carbonate rocks such as limestone, marble, and various types of skarns. The Silurian Saishiteng Formation is mainly composed of gray–black hornstone, quartz siltstone, or weakly skarn calcareous siltstone. The strata in the mining area are monoclinic and generally inclined to the north. Two large-scale fault structures (F1 and F2) are present: F1 extends in NW–SE direction, and F2 extends in W–SE direction, both dipping toward the northeast. These two faults belong to the secondary structures of the Kunbei Fault in the region, which are relatively small structural units developed under the influence of the Kunbei Fault. They play a major role in controlling the emplacement of intrusive rocks in the area. The intrusive rocks in the southern region are mainly composed of gray-white monzogranite, gray-white granodiorite, and dark diorite, followed by quartz diorite, gabbro diabase, etc. The northern intrusive rocks are mainly composed of light flesh-red monzogranite. There is a phase transition in the northern intrusive rocks, with some areas transitioning from the monzogranite phase to the potassium feldspar granite phase. The granitic batholith in the northern part of the mining area invaded and captured the Tanjianshan group strata to varying degrees. The granitic batholith in the southern part of the mining area intrudes southward into the Proterozoic Jinshuikou rock group and northward into the Ordovician Tanjianshan group clastic rock group. The ore bodies in the mining area are mostly located in the skarn zone within the carbonate rocks of the Tanjianshan Group, which are controlled by interlayer fracture zones, and there is basically no mineralization in the contact zone between the granitic batholith and the wall rocks.

2.2 Deposit geology

The ore body in the mining area is divided into four ore sections, corresponding to four magnetic anomalies (M1, M2, M3, and M4) (Figure 1C). All four ore sections exhibit varying degrees of magnetite mineralization, with minor differences in individual mineral combinations. The host rock is mainly composed of skarn. The main types of ore bodies include iron, iron–copper, and copper–zinc ore bodies.

No. 1 ore section consists of two parallel, vein-shaped magnetite ore bodies. The nearby outcrop belongs to the lower rock unit of the Proterozoic Jinshuikou Group (Pt1jna). The lithology is mainly grayish opthalmite, followed by grayish-black biotite quartz schist. The gabbro veins, oriented in a NWW direction, are exposed in the north, and the lenticular skarn belt, mainly composed of garnet skarn, is distributed in the middle. The surface and shallow parts of No. 2 ore section are composed of copper–zinc ore, whereas the deeper parts are dominated by iron ore (Figure 1D), occurring in a lens-like shape. The exposed strata near the ore section include carbonate rock formations of the Ordovician Tanjianshan Group, such as limestone, marble, and skarn, with interlayers of tuff. A banded skarn belt is distributed to the north of the ore section, mainly composed of green curtain garnet skarn. The No. 3 ore section is mainly composed of iron–copper ore bodies. The surrounding exposed strata include the carbonate rock formations (O3tnc), such as limestone, marble, and skarn, of the Ordovician Tanjianshan Group. Skarn belts are highly developed in these ore sections, appearing in banded and lenticular shapes, and are mainly composed of garnet skarn, followed by diopside skarn and diopside garnet skarn. The shallow part of No. 4 ore section is almost entirely composed of iron ore bodies, whereas iron–copper ore bodies appear toward the deeper part. The exposed strata include the carbonate rocks (O3tnc) of the Ordovician Tanjianshan Group, such as limestone, marble, and skarn. To the north of the ore section lies a Late Triassic shallow red porphyritic monzogranite (πηγ4), whereas to the south, Early Devonian monzogranite and granodiorite, which are in intrusive contact with the Ordovician Tanjianshan Group (Figures 2A–C). The skarn zone is well developed in this ore section, and all the ore bodies are hosted within it. The lithology is mainly garnet skarn, followed by epidote–garnet skarn and diopside skarn.

3 Samples and analytical methods

3.1 Sample collection and petrological characteristics

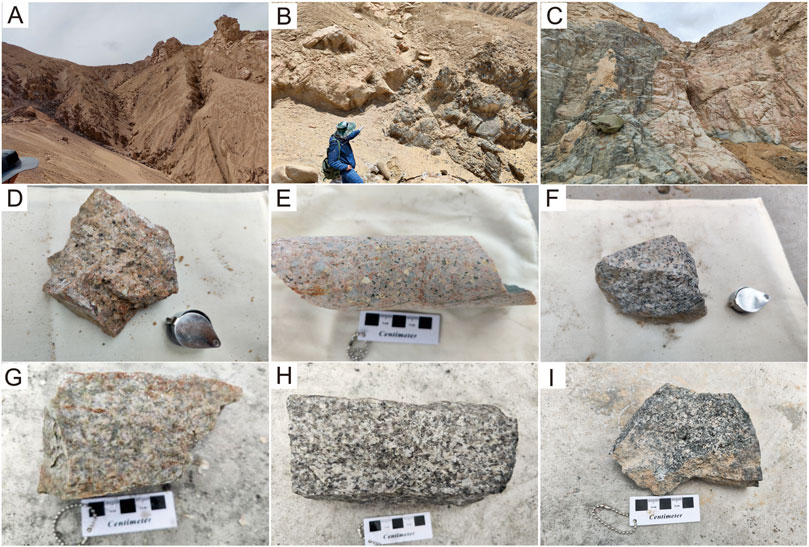

The samples for this study were collected from various parts of the mining area. Light flesh-red monzogranites were collected from the northern part (sampling location: M4). From the southern part, gray–white monzogranites (sampling location: M4), gray–white granodiorites (sampling location: M4), and dark diorites (sampling location: southwest of M4) were obtained. Sampling locations and sample photographs are shown in Figures 1C, 2. Samples were selected based on microscopic observations showing no significant alteration and were subsequently analyzed for rock geochemistry, isotopic geochemistry, zircon U–Pb dating, and LA-ICP-MS geochronology.

Figure 2. Photographs of hand specimens and field outcrops of granitic lithologies in the central-southern part of the mining area. (A–C) Field outcrop profiles; (D,E) Surface and drill hole samples of light flesh-red monzogranite; (F,G) Surface and downhole samples of gray–white monzogranite; (H) Underground sample of granodiorite; (I) Surface sample of dark diorite.

The light flesh-red monzogranites are predominantly found in the northern part of the mining area, exhibiting massive structures (Figures 2D,E). The main minerals include quartz (36%), plagioclase (30%), potassium feldspar (28%), and biotite (6%). Plagioclase and potassium feldspar are predominantly euhedral to subhedral tabular crystals, showing polysynthetic and Carlsbad twinning (Figures 3B,C). Quartz appears as irregularly granular, filling the gaps between other minerals. Biotite is euhedral to subhedral and occurs as plate-like crystals (Figure 3A).

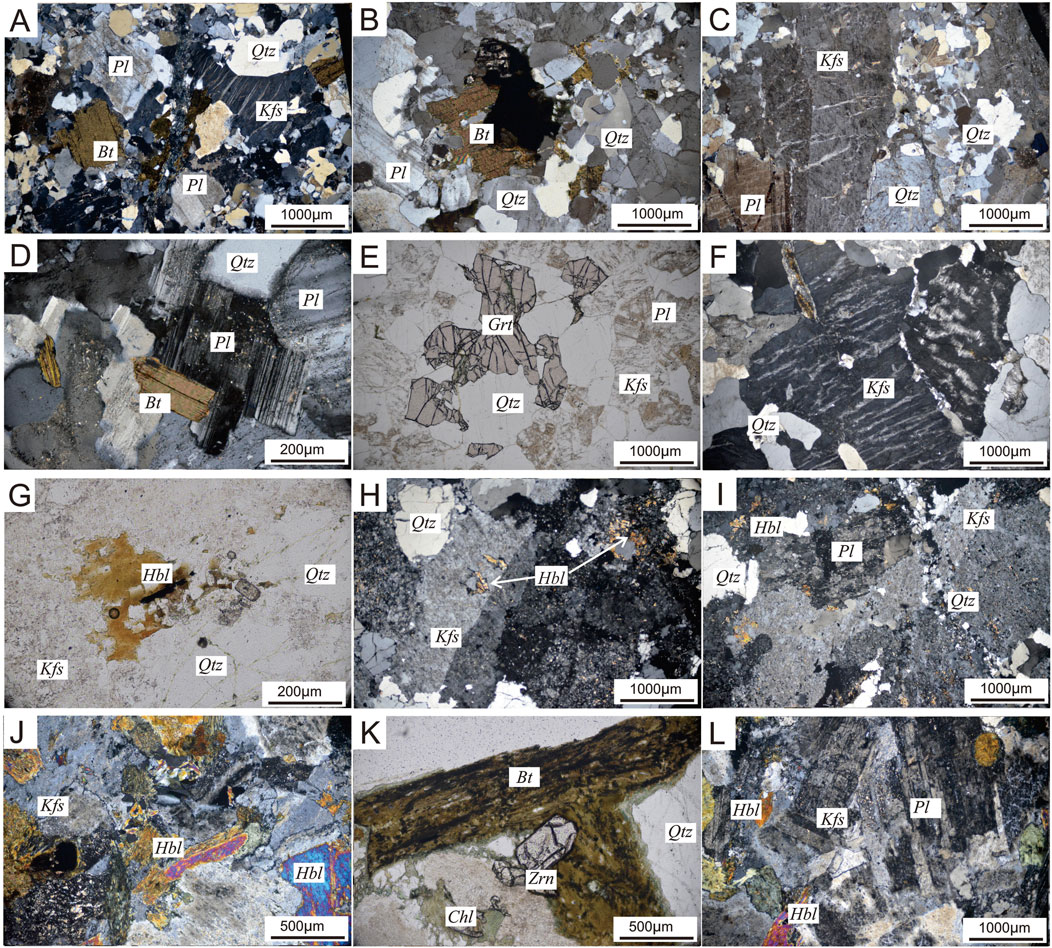

Figure 3. Microscopic identification photographs of samples from the mining area. (A–C) Light flesh-red monzogranite; (D–F) Gray–white monzogranite; (G–I) Granodiorite; (J–L) Diorite; Pl: Plagioclase; Kfs: Orthoclase; Qtz: Quartz; Bt: Biotite; Hbl: Hornblende; Grt: Garnet; Chl: Chlorite; Zrn: Zircon.

The gray–white monzogranites are primarily distributed in the southeastern part of the mining area, forming irregular stocks with massive structures (Figures 2F,G). The main minerals include quartz (50%), plagioclase (22%), potassium feldspar (20%), and biotite (8%). Some samples also contain garnet-bearing clusters (Figure 3E). Quartz occurs as euhedral to subhedral grains, interstitial to other minerals. Plagioclase is euhedral to subhedral, tabular, with well-developed perthitic twin lamellae and obvious cleavage (Figure 3D). Potassium feldspar is predominantly euhedral to subhedral, tabular, with perthitic zoning visible in some areas (Figure 3F). Biotite is euhedral and occurs as plate-like crystals with well-developed cleavage.

The gray–white granodiorites are mainly distributed in the southern part of the mining area, with an overall gray–white color and massive structures (Figure 2H). They exhibit anhedral granular textures, with primary minerals including plagioclase (42%), quartz (35%), potassium feldspar (15%), and hornblende (8%). Plagioclase is subhedral to anhedral and tabular, with perthitic twin lamellae visible (Figure 3I). Quartz is subhedral to anhedral, granular, and fills the gaps between feldspar grains. Potassium feldspar is predominantly euhedral to subhedral and tabular, displaying kaesbar twinning, and is often altered to kaolinite, resulting in a turbid surface (Figure 3H). Hornblende occurs in irregular shapes (Figure 3G).

The diorites are primarily dark brown with massive structures (Figure 2I) and are widely developed in the southern part of the mining area. Their mineral composition includes plagioclase (approximately 51%), hornblende (16%), quartz (approximately 10%), potassium feldspar (approximately 9%), biotite (10%), and chlorite (4%), with zircon as the main accessory mineral (Figure 3K). Plagioclase is predominantly subhedral and tabular, with well-developed perthitic twin lamellae and obvious zoning (Figure 3L). Hornblende is irregularly shaped (Figure 3J). Quartz occurs as subhedral to anhedral and granular, filling cracks between other minerals. Potassium feldspar is subhedral to anhedral and tabular, with some alteration to kaolinite. Biotite is euhedral and occurs as plate-like crystals, with some locally altered to chlorite.

3.2 Test analysis method

Rock chemical analyses include the determination of major, trace, and rare earth elements (REEs) of the samples. The samples were analyzed under ambient conditions of 10 °C–4 °C and 30%–50% humidity. Major elements were analyzed using a wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF, model: ZSXPrimus II), with an analysis accuracy better than 1%. FeO content was determined by potassium dichromate titration. Trace elements and REEs were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Agilent 7900), and the analysis accuracy is better than 3%.

Zircon samples for dating were selected using standard heavy mineral separation technology at Shangpu Analysis Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan City, Hubei Province. Zircons with flat and smooth surfaces, different length-to-width ratios, and different column cone characteristics were carefully selected through binocular observation to prepare targets. The zircon particles were stuck on double-sided adhesive tape and fixed on the sample target with colorless transparent epoxy resin. After the epoxy resin was cured, the surface of the zircon particles was polished to expose one-third to one-half of the cross section of most zircon particles. Before in situ analysis, microphotography was performed using reflected light and cathodoluminescence imaging to study the crystal morphology and internal structural characteristics of zircon in detail, thus selecting the best spot for isotope analysis.

The LA-ICP-MS analysis was conducted at Shangpu Analysis Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan City, Hubei Province. The U–Pb isotope and trace element content analyses were conducted using an ICP-MS (Agilent 7900) and its matched coherent 193 nm Excimer Laser Etching System (GeoLas HD). Analytical conditions included a laser energy of 80 mJ, frequency of 5 Hz, and laser beam spot diameter of 32 µm. The zircon age was determined using standard zircon 91,500 as the external standard, GJ-1 as the internal standard, and He as the carrier gas. Data processing was performed using the ICPMSDATACAL 10.8 program. The zircon U–Pb age harmonic line graph and weighted average ages were calculated and plotted using Isoplot 3.0s. The error for single data points is estimated at 1 σ, and the error for the sample weighted average age is 2 σ, with a confidence level of 95%.

Based on LA-ICP-MS U–Pb dating, zircons with good harmony were selected for micro area Hf isotope analysis. These measurements were conducted at Sichuan Chuangyuan Microspectral Technology Co., Ltd., using a RESOlution 193 laser ablation system. The international zircon standard GJ1 was employed as the external standard, with a laser beam pulse energy of 5.3 J cm−2. The operating conditions and detailed analysis procedures can be found in Hu et al. (2012). The experimental determination obtained a zircon standard GJ1 with 176Hf/177Hf values ranging from 0.282440 to 0.282508, which is consistent with the recommended value of 0.282010 ± 0.000003.

4 Analytical results

4.1 Zircon U–Pb geochronology

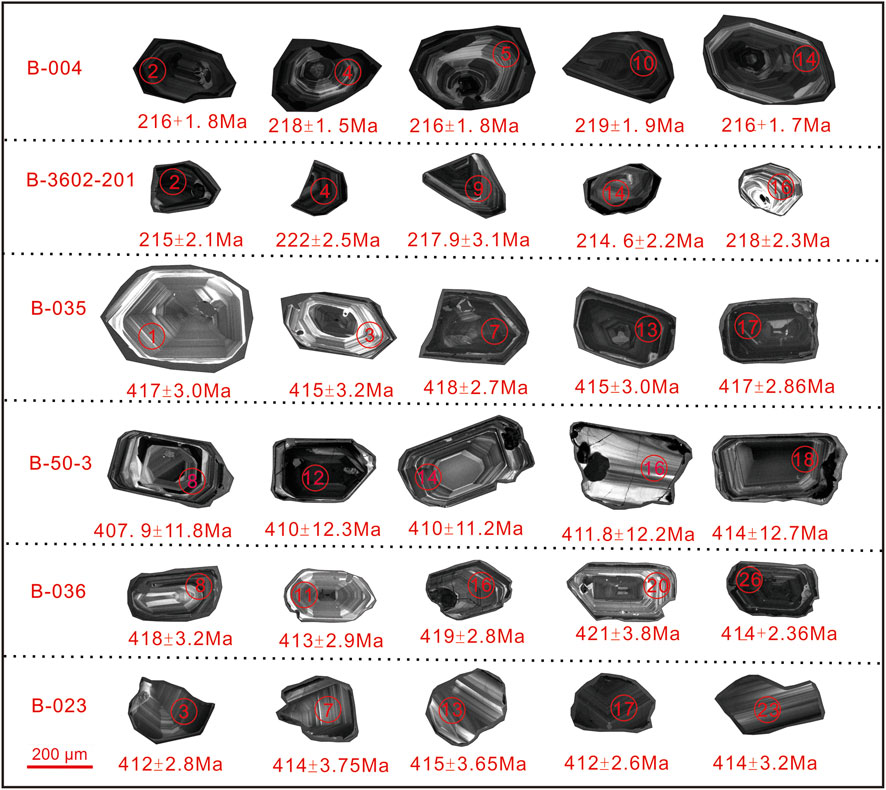

The zircon U–Pb geochronology of the intrusive rock samples from the mining area was conducted using LA-ICP-MS. The zircons analyzed are light yellow or transparent, with a prismatic shape and grain sizes ranging from 60 to 370 μm. Cathodoluminescence images (Figure 4) reveal distinct rhythmic oscillatory zoning of the zircons. All six groups of zircons exhibit Th/U ratios exceeding 0.4. Additionally, the zircons exhibit a pronounced positive Ce anomaly, which are characteristic features of magmatic zircons (Zang et al., 2025). The analytical error for the zircon U–Pb dating is reported at the 1σ level.

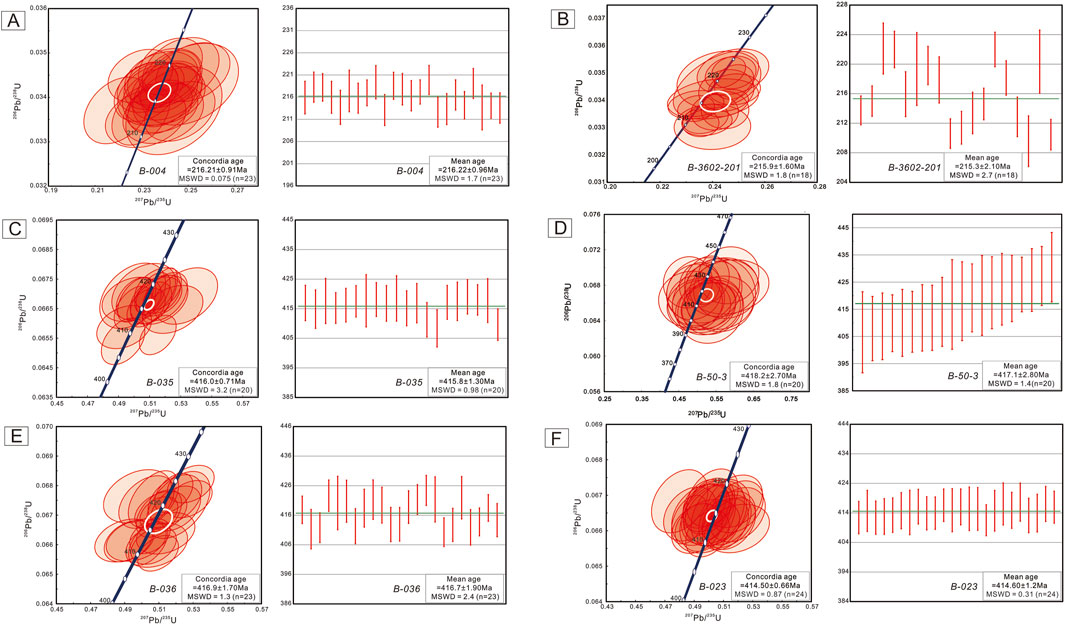

Two sample groups from the light flesh-red monzogranites were analyzed. The first sample (B-004) yielded a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 216.22 ± 0.96 Ma (MSWD = 1.7) based on 23 measured points (Figure 5A). The second sample (B-3602-201) yielded a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 215.3 ± 2.1 Ma (MSWD = 2.7) from 18 measured points (Figure 5B). In both cases, the analytical data from the northern part of the mining area are located on or near the concordia line, indicating that the ages represent the crystallization ages of the rocks, which belong to the Late Triassic. Similarly, two sample groups were analyzed for the gray–white monzogranites. The first sample (B-035) yielded a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 415.8 ± 1.3 Ma (MSWD = 0.98) from 20 zircons (Figure 5C). The second sample (B-50-3) provided a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 417.1 ± 2.8 Ma (MSWD = 1.4) from 20 measured points (Figure 5D). The 20 zircons measured from the gray–white granodiorite sample (B-036) obtained a206Pb/238U weighted average age of 416.7 ± 1.9 Ma (MSWD = 2.4) (Figure 5E). The dark diorite sample (B-023) resulted in a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 414.6 ± 1.2 Ma from 20 measured points (MSWD = 0.31) (Figure 5F). The zircon ages of the four groups of samples from the southern part of the mining area show consistent values, with analytical data distributed on or near the concordia line, representing the crystallization ages of the rocks, which belong to the Early Devonian.

Figure 5. Concordia and weighted average plots of zircon U–Pb ages of intrusive rocks from the mining area. (A,B) Light flesh-red monzogranites; (C,D) Gray–white monzogranites; (E) Gray–white granodiorites; (F) Dark diorites.

The results indicate the presence of two distinct magmatic rock suites with significant temporal differences in the mining area: the Early Devonian granitic intrusions in the southern part and the Late Triassic granitic intrusions in the northern part.

4.2 Lithogeochemical characteristics

4.2.1 Major elements

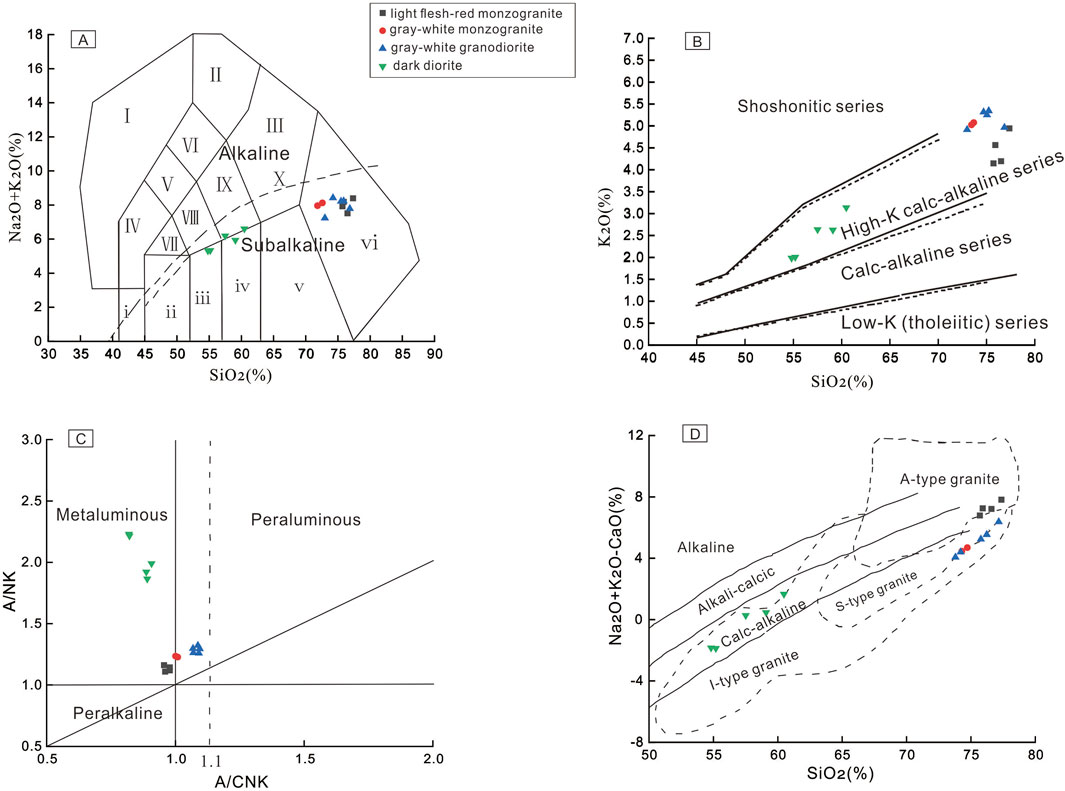

The results of major, rare earth, and trace element analyses of intrusive rocks from the Lalinggaolihe mining area are presented in Table 1. The SiO2 content of the Late Triassic light flesh-red monzogranites in the north of the mining area ranges from 75.72% to 77.36%, indicating silicon supersaturation (Zhu, 2019). CaO (0.58%–1.15%) and MgO (0.20%–0.26%) contents are low, reflecting calcium and magnesium depletion. The K2O and Na2O + K2O contents are in the range of 4.14%–4.94% and 7.51%–8.39%, respectively, with a Riteman index of 1.68–2.05, showing high silicon and alkali-rich characteristics, belonging to the high potassium calcium alkaline series (Figure 6B). On the silica alkali TAS rock classification projection map, the samples fall within the granite field (Figure 6A). The Al2O3/(CaO + Na2O+ K2O) (A/CNK) ratios range from 0.89 to 0.96, with an average value of 0.93, indicating quasi-aluminum granites (Figure 6C). In the Na2O + K2O-CaO vs. SiO2 diagram, all samples are located in the A-type granite region (Figure 6D). Overall, the northern monzogranite samples exhibit characteristics of high silicon, calc alkaline, and poor calcium and magnesium.

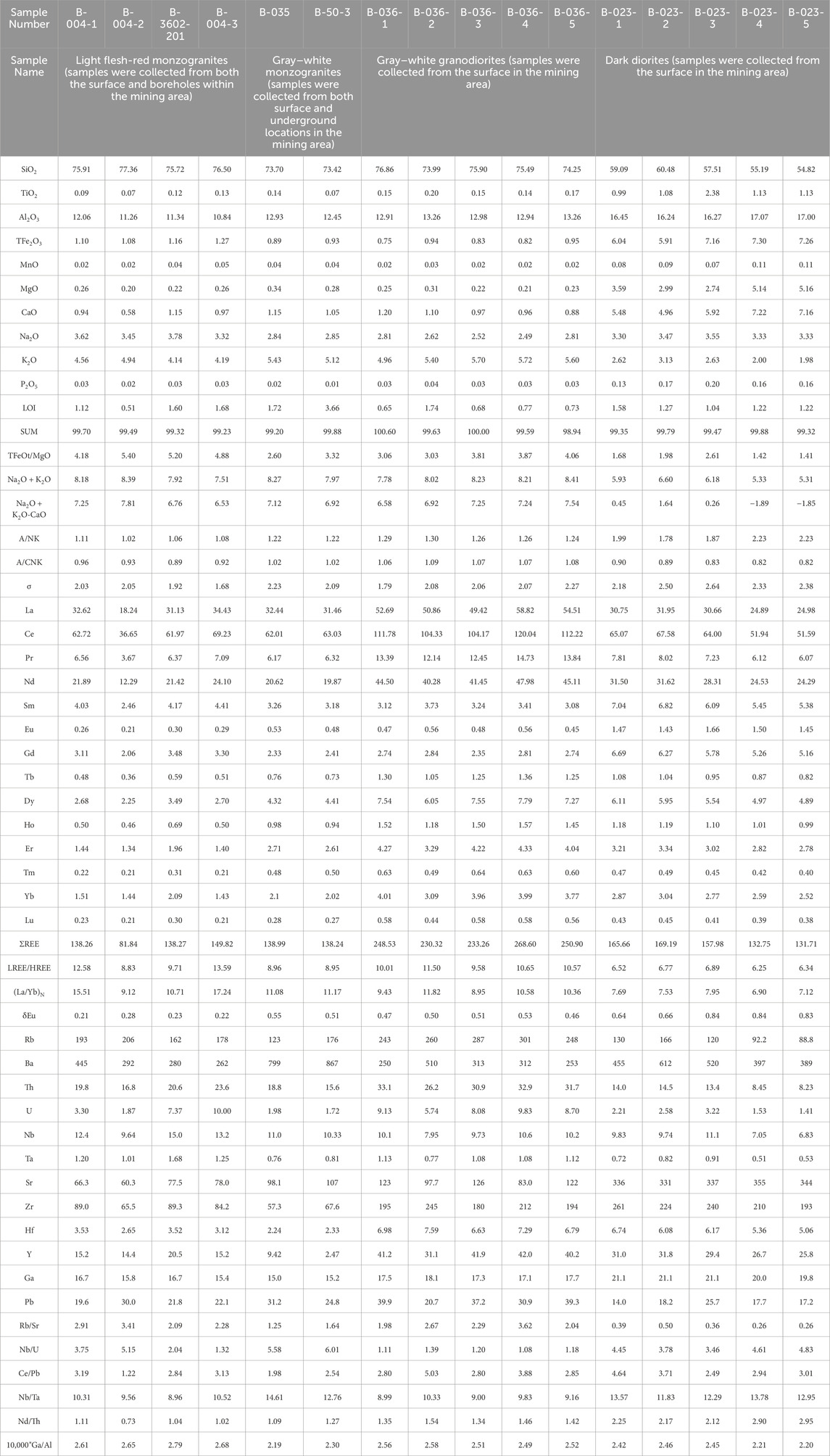

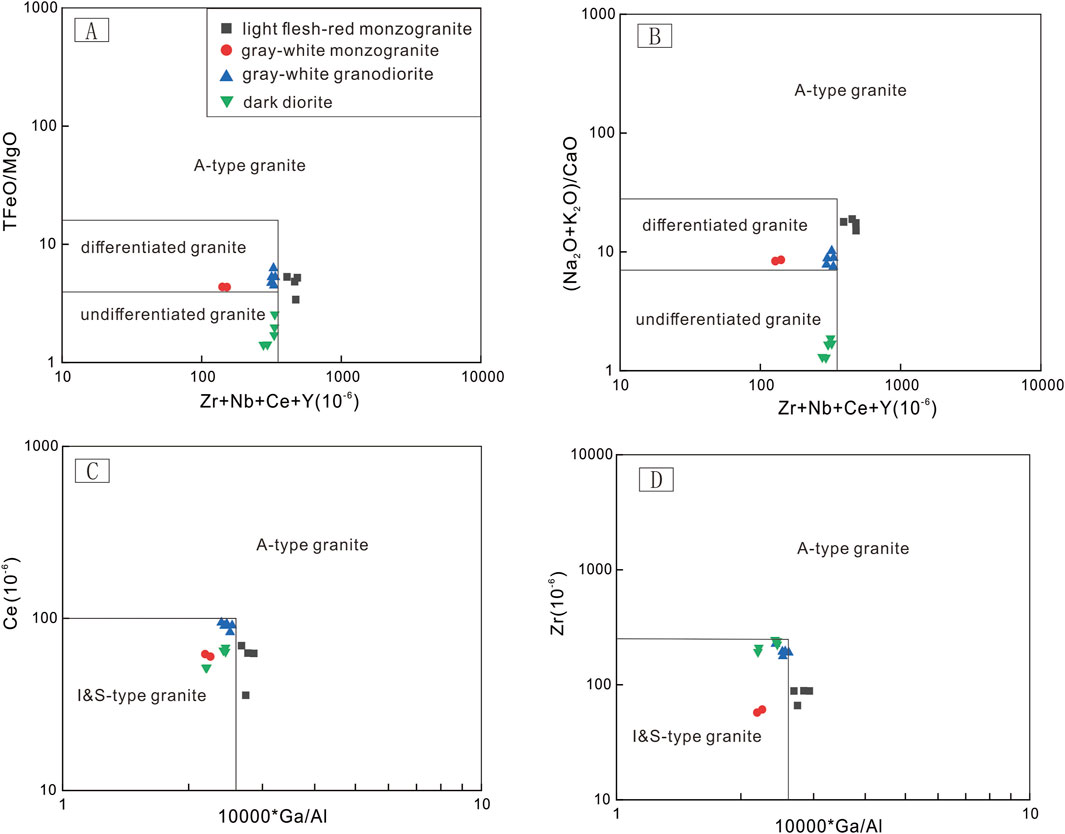

Table 1. Analytical results of major elements (wt%) and trace elements (×10-6) in rock masses from the Lalinggaolihe mining area.

Figure 6. (A) Silica alkali TAS rock classification projection map; (B) K2O–SiO2 diagram; (C) A/NK-A/CNK diagram; (D) Diagram for discrimination of granite types. (I): Alkaline rock; II: Alkaline syenite; III: Syenite; IV: Alkaline gabbro; V: Alkaline monzonitic diorite; VI: Alkaline monzonitic syenite; VII: Monzogabbro; VIII: Monzodiorite; IX: Monzonite; X: Quartz monzonite; i: Olivine gabbro; ii: Gabbro; iii: Gabbrodiorite; iv: Diorite; v: Granodiorite; vi: Granite.

The SiO2 contents of the Early Devonian gray–white monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites in the southern part of the area vary within the ranges of 73.42%–73.70%, 73.99%–76.86%, and 54.82%–60.48%, respectively. The CaO contents range from 1.05% to 1.15%, 0.88%–1.20%, and 4.96%–7.22%, whereas the MgO contents range from 0.28% to 0.34%, 0.21%–0.31%, and 2.74%–5.16%. The monzogranites and granodiorites are rich in alkali and poor in calcium and magnesium, whereas the diorites are relatively rich in calcium and magnesium. The Na2O + K2O contents of the three rock types range from 7.97% to 8.27%, 7.78%–8.41%, and 5.31%–6.60%, respectively. The Rittmann index (σ) values are 2.09–2.23, 1.79–2.27, and 2.18–2.64, respectively, belonging to the calcium alkaline series (Figure 6B). On the silica alkali TAS rock classification projection map, the monzogranites and granodiorites fall within the granite range, whereas the diorites fall within the diorite range (Figure 6A). The A/CNK ratios for the monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites in the southern area are 1.02, 1.06–1.09, and 0.82–0.90, respectively, with average values of 1.02, 1.07, and 0.85. In the A/NK–A/CNK diagram (Figure 6C), the samples of monzogranites and granodiorites fall within the weak peraluminous rock range, whereas the samples of diorites fall within the quasi-aluminous rock range. In the Na2O + K2O-CaO vs. SiO2 diagram (Figure 6D), the samples of monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites mainly fall along the boundary of S- and I type.

4.2.2 Rare earth and trace elements

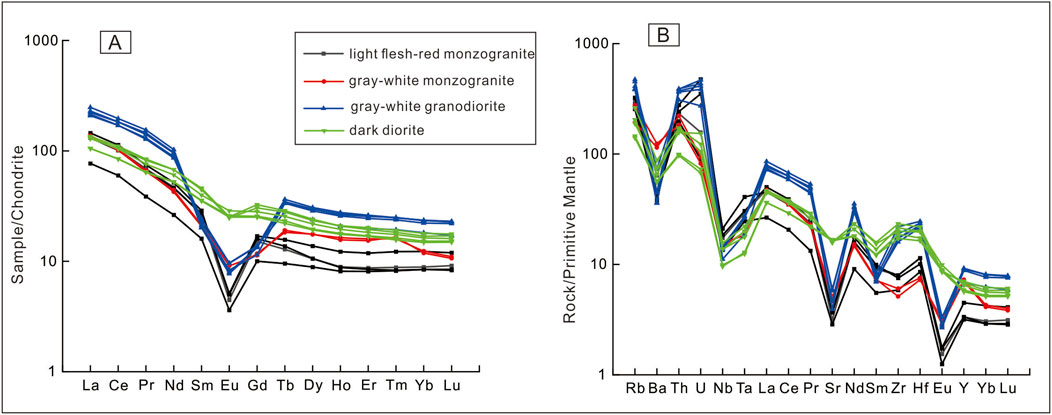

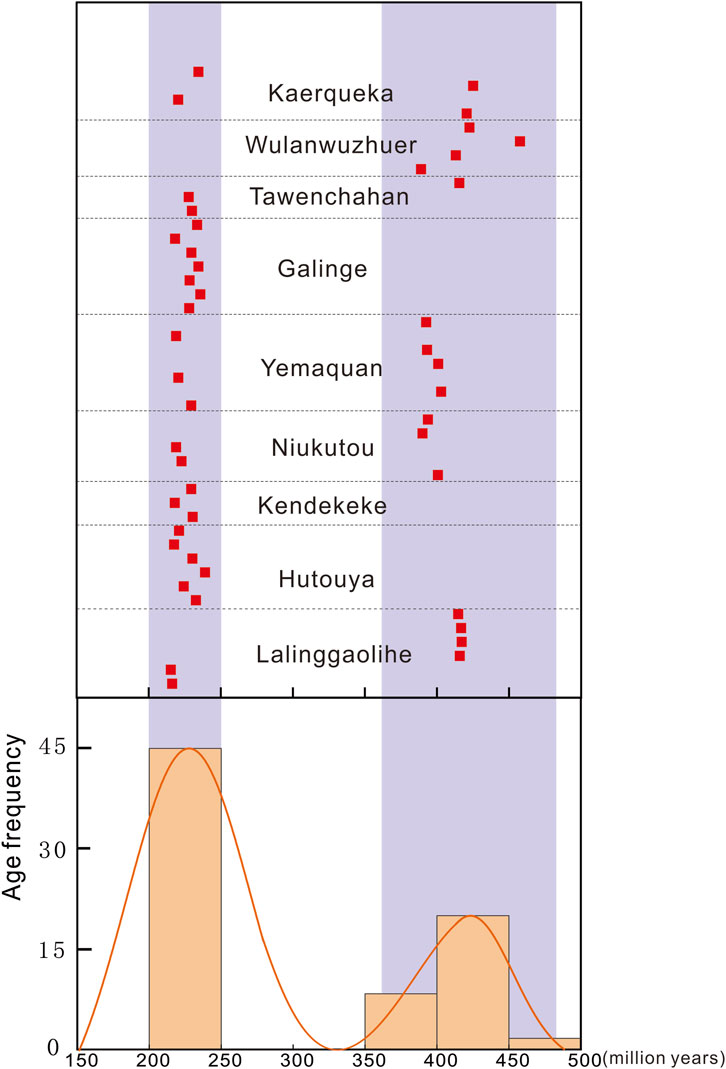

The total REE content of the Late Triassic light flesh-red monzogranites ranges from 81.84 to 149.82 ppm, with an average value of 127.05 ppm. The REE enrichment pattern is LREE-enriched, with an average LREE/HREE ratio of 11.18 and an average (La/Yb)N ratio of 13.14. This indicates significant fractionation between light and heavy REEs and a strong enrichment in light REEs (Figure 7A). The samples exhibit a obvious negative Eu anomaly (δEu = 0.21–0.28), reflecting strong fractional crystallization of plagioclase during magma evolution (Zhang and Li, 2025). The whole-rock compositions show a general deficiency in large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs), such as Sr and Ba, and high-field-strength elements (HFSEs), such as U, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta (Figure 7B), characteristics typical of A-type granites (Ma et al., 2024). The main reason for the loss of Eu and Sr in the sample may be due to the fractional crystallization of plagioclase during the magmatic evolution (Zhang et al., 2025).

Figure 7. (A) Chondrite-normalized REE distribution patterns of intrusive rocks in the mining area (normalized using values from Sun and McDonough, 1989); (B) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagram (normalized using values from Sun and McDon, 1989).

The REE contents of the Early Devonian gray–white monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites range from 138.24 to 138.99 ppm, 230.32–268.60 ppm, and 131.7–169.19 ppm, respectively, with average values of 138.67 ppm, 246. 32 ppm, and 151.46 ppm. All three rock types show LREE-enriched REE distribution patterns (Figure 7A), which are more pronounced in the gray–white monzogranites and granodiorites than in the diorites. The average LREE/HREE ratios for the gray–white monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites are 8.95, 10.46, and 6.55, respectively, and the corresponding average (La/Yb)N ratios are 11.13, 10.23, and 7.44. These values indicate LREE enrichment and obvious fractionation between LREEs and HREEs. The δEu values of the gray–white monzogranites and granodiorites range from 0.51 to 0.55 and 0.46 to 0.53, respectively. Both show moderately negative Eu anomalies, indicating that plagioclase exhibits a moderate degree of fractional crystallization. The dark diorites exhibit δEu values of 0.64–0.84, also indicating moderately negative Eu anomalies, suggesting a moderate degree of plagioclase segregation crystallization. The standardized trace element and REE diagrams (Figures 7A,B) show that these three groups of samples exhibit different test results. The gray–white granodiorites are depleted in Sr, U, Hf, Nb, and Ta but enriched in Rb. By contrast, although the dark diorites are depleted in Nb, Ta, Hf, and U, they are not severely depleted in Sr and are enriched in Zr (Figure 7B). Although some samples of the gray–white monzogranite exhibit deviations in their geochemical patterns, they generally display significant depletions in LILEs (e.g., Sr) and HFSEs (e.g., Nb, Ta, U, and Zr).

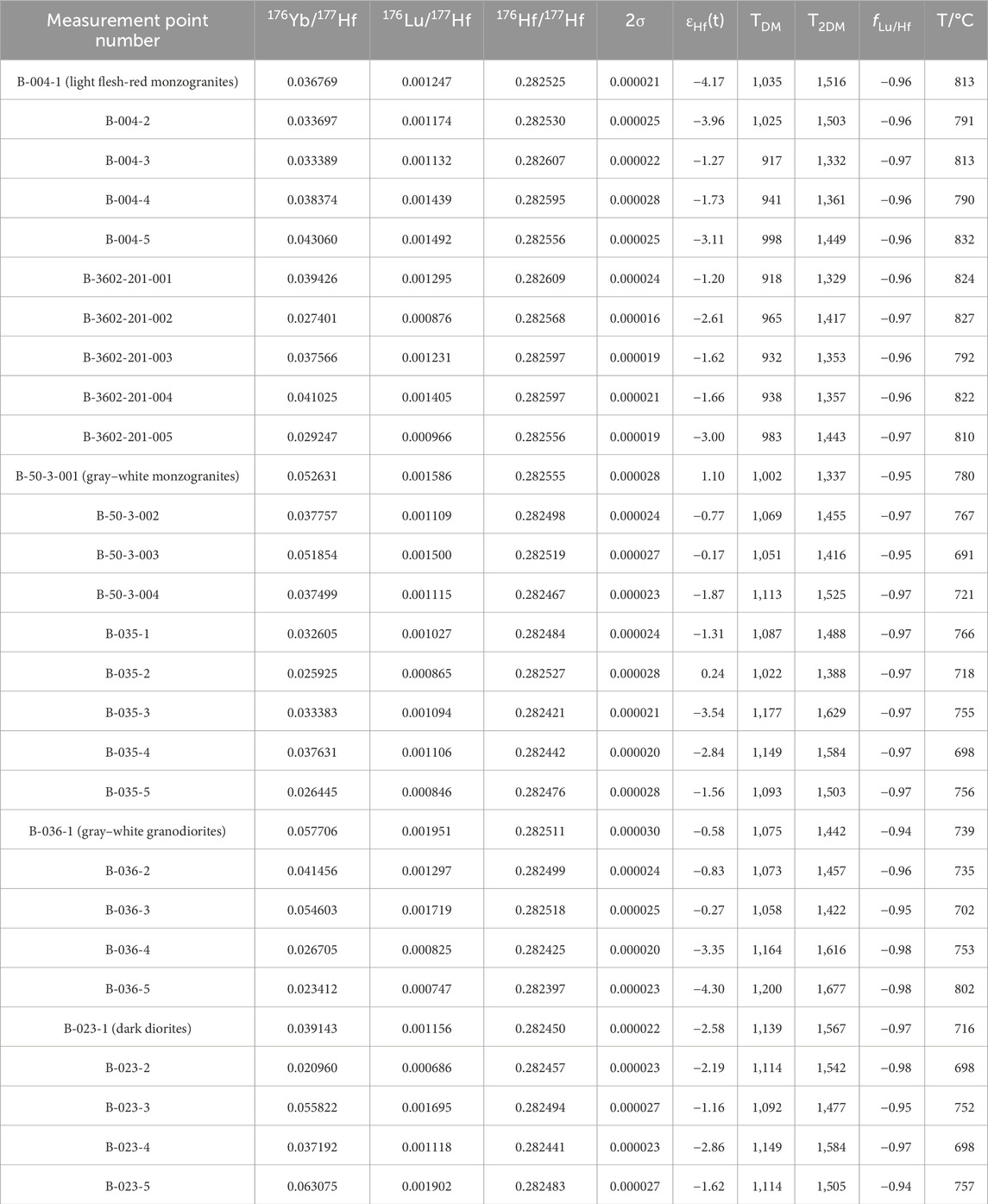

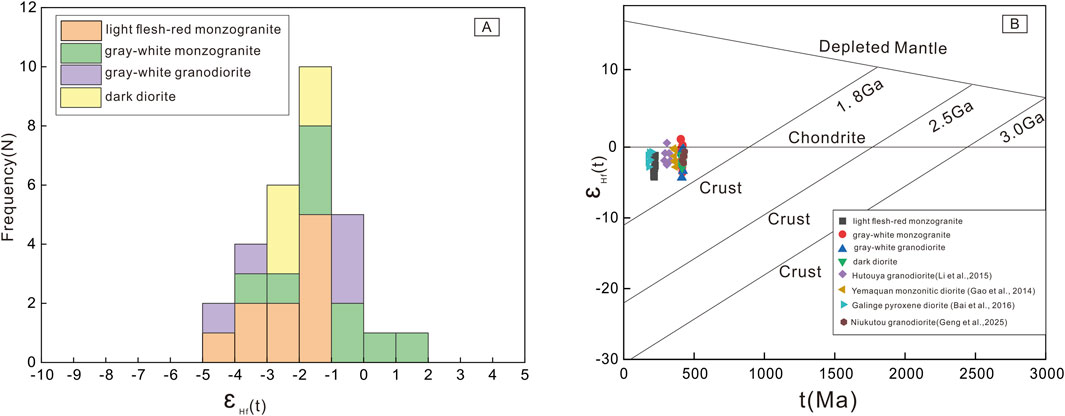

4.3 Hf isotopic characteristics of zircon

The results of zircon Hf isotope analyses are presented in Table 2. The measured 176Lu/177Hf values of zircon particles are less than 0.003918, indicating low radiogenic Hf accumulation after zircon formation. Therefore, the measured 176Lu/177Hf can represent the 176Lu/177Hf value at the time of zircon formation (Zhu et al., 2025). In addition, fLu/Hf represents the degree of deviation of the Lu/Hf ratio in a sample relative to a reference standard (usually chondrite meteorites or primitive mantle). The larger the negative value (such as fLu/Hf = −0.95), the more significant the loss of Lu in the sample, reflecting the recycling of ancient crustal materials; If the value is close to or greater than 0, it suggests the addition of new crustal or mantle derived materials (Hawkesworth and Kemp, 2006). The fLu/Hf values of zircon range from −0.98 to −0.94, suggesting that the two-stage model age provides a more robust estimate for the timing when the source material was extracted from the depleted mantle and incorporated into the crust, as it accounts for further Lu/Hf fractionation within the crust, whereas the one-stage model age may underestimate this age (Wu et al., 2007).

For the light flesh-red monzogranites from the northern mining area, the 176Hf/177Hf values range from 0.282525 to 0.282609, with an average of 0.282574. The corresponding εHf(t) values, calculated based on an age of 216 Ma, range from −4.17 to −1.2, with an average of −2.43. The two-stage Hf model ages of t2DM range from 1,329 to 1,516 Ma, with an average of 1,406 Ma. For the gray–white monzogranites from the southern part, the 176Hf/177Hf values range from 0.282295 to 0.28255 with an average of 0.282468. The εHf(t) values range from −8.21 to 1.10, with an average of −1.89, and the t2DM values range from 1,337 to 1924 Ma, with an average of 1,525 Ma, calculated based on an age of 416 Ma. The 176Hf/177Hf values of the gray–white granodiorites range from 0.282397 to 0.282518, with an average of 0.282470. The εHf(t) values range from −4.3 to −0.27, with an average of −1.87, and the t2DM values range from 1,422 to 1,677 Ma, with an average of 1,523 Ma, calculated based on an age of 415 Ma. For the dark diorites, the 176Hf/177Hf values range from 0.282441 to 0.282494, with an average of 0.282465. Calculated based on an age of 216 Ma, the εHf(t) values range from −2.86 to −1.16, with an average of −2.08, and the t2DM values range from 1,477 to 1,584 Ma, with an average of 1,535 Ma. Except for two samples (B-50-3-001 and B-035-2), all measured zircon εHf(t) values are less than zero, indicating that zircons are mainly formed from the remelting of crust-derived materials. The average εHf(t) values range from −2.43 to −1.19, which are close to 0, implying the mixing of crust and mantle materials (Liu B. et al., 2025).

5 Discussion

5.1 Zircon crystallization age and its significance

The zircon U–Pb ages of the light flesh-red monzogranites in the northern part of the mining area are obtained as 216.22 ± 0.96 and 215.3 ± 2.1 Ma. The zircon U–Pb ages of gray–white monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites in the southern part are obtained as 415.8 ± 1.3, 417.1 ± 2.8, 416.7 ± 1.9, and 414.6 ± 1.2 Ma. These results show that the northern and southern rock bodies of the mining area correspond to the Early Devonian and Late Triassic, respectively. In the northern area, the granite bedrock mainly consists of light flesh-red monzogranites, with a local phase transition to potassium feldspar granite, which is overlaid on the sandstone of the Saishiteng Formation (Ss). Deep borehole observations reveal that the batholith invaded and captured the underlying Ordovician Tanjianshan Group (O3tn) in varying degrees. In the southern part, the granitic batholith is dominated by granodiorites, monzogranites, and diorites, followed by quartz diorites and gabbro diabase. Field observations reveal rapid changes in lithology, with numerous dark diorite inclusions and part of gneiss xenolith often existing in gray-white monzogranites. The southern batholith intrudes into the Jinshuikou Group (Pt1Jn) of the Lower Proterozoic and the Tanjianshan Group (O3tn) of the Ordovician. The characteristics of the batholiths in the northern and southern areas are different, reflecting the occurrence of multi-stage magmatism in the mining area.

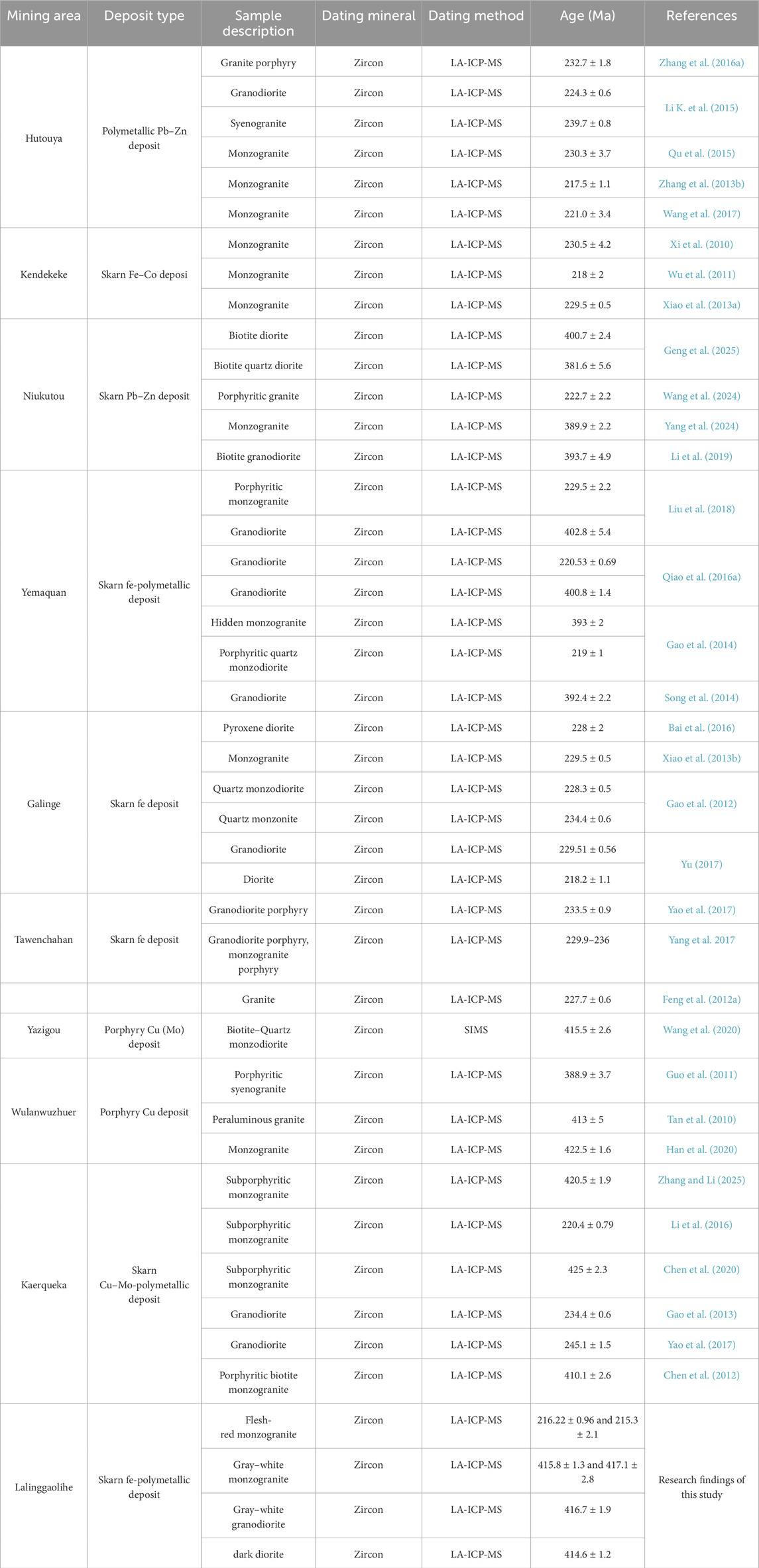

From a regional geological view, the occurrence of Early Devonian and Late Triassic multi-stage magmatism in the Lalinggaolihe iron ore area is not an isolated phenomenon. Numerous studies have been conducted on the magmatic evolution and metallogenic events in the Qimantag area of the East Kunlun orogenic belt. Some researchers have proposed that the granite in the East Kunlun orogenic belt can be divided into four periods, corresponding to four orogenic cycles (Feng et al., 2024). Others have summarized the tectonic evolution of the East Kunlun orogenic belt into two models: Early Paleozoic–Early Devonian and Early Carboniferous–Triassic two-stage subduction accretion (Dong et al., 2022). Research shows that intermediate-acid intrusive rocks of the Early–Middle Devonian and Middle–Late Triassic are widely developed in the Qimantag area, and numerous porphyry and skarn deposits, closely related to regional magmatism, have been identified (Zhong et al., 2025a), such as Hutouya, Kendekeke, Galinge, Niukutou, and Yemaquan (Table 3; Figure 8). Qiao et al. (2016b) based on zircon U-Pb dating results of granodiorite (220.53 ± 0.69 Ma, 400.8 ± 1.4 Ma), believed that the formation of the Yemaquan iron polymetallic deposit is closely related to the intermediate acidic intrusive rocks at the end of two tectonic magmatic cycles, and is the result of two mineralization periods. Zhang et al. (2016c) based on zircon U-Pb dating results of granite porphyry (232.7 ± 1.8), believed that the East Kunlun Mountains entered the late stage of intracontinental orogeny during the Indosinian period, and large-scale magmatic events caused Indosinian mineralization in the Qimantag area, leading to the formation of the Hutouya polymetallic mining area. Based on the zircon U-Pb ages (415.5 ± 2.6) of biotite quartz diorite, Wang et al. (2020) suggest that the rock mass of Yazigou was formed during the post collisional intracontinental extension stage and is closely related to regional lead-zinc mineralization. These deposits are closely related to the two phases of collisional magmatism that followed the closure of the Proto-Tethys and Paleo-Tethys oceans. The chronological data presented in this study confirm two magmatic events in the Lalinggaolihe mining area. Their intrusion periods correspond to the two tectono-magmatic cycles of Early Paleozoic and Late Paleozoic–Mesozoic in the Qimantag area of the Eastern Kunlun Mountains, respectively (Gao et al., 2014). This further supports the existence of two paleo-oceanic evolutionary events.Meanwhile, the new geochronological data obtained in this study precisely limits the closure time of the original Tethys Ocean. Guo et al. (2024), through their study of the Valega granite rocks, suggest that the original Tethys ocean was not completely closed at 414 Ma. This study indicates that the primitive Tethys Ocean was already in the post collisional orogeny stage during the Early Devonian, and its closure time was earlier than some scholars (Guo et al., 2024) believed. This provides a more precise temporal constraint for understanding the geodynamic evolution of the region.

Table 3. Diagenetic ages of main porphyry–skarn deposits in the Qimantag area, East Kunlun Mountains.

Figure 8. Statistics of diagenetic ages of main porphyry–skarn deposits in the Qimantag area, East Kunlun Mountains.

5.2 Rock types and genesis

Intrusive rocks in the Lalinggaolihe mining area are widely exposed and display a wide range of lithologies, from intermediate basic to acidic compositions. Their distribution is controlled by the NW–SE-oriented faults. Based on the magma source characteristics and geochemical signatures, granitic rocks can be divided into I-, S-, and A-type granites (Wu et al., 2007). Generally, S-type granites show strong peraluminous characteristics. However, all the intrusive rock samples in this study exhibit quasi-aluminous to weakly peraluminous properties (A/CNK <1.1), which is inconsistent with the characteristics of S-type granites. In addition, the rocks lack cordierite, muscovite, and other aluminum-rich minerals, and the P2O5 content is relatively low (0.01%–0.2%), which further differentiates them from S-type granites (Chappell and White, 1992).

A-type granites generally exhibit alkaline, low-water content, and non-orogenic characteristics (Liu X. et al., 2025). They typically exhibit the following geochemical characteristics: (1) They are enriched in SiO2 and alkalies (K2O + Na2O) and depleted in CaO, MgO, and Al2O3, with high TFeO/MgO and Ga/Al ratios. They show significant enrichment in HFSEs and Y (Ce), whereas significant depletion in Ba, Sr, Eu, P, and Ti. Their REE patterns typically display a LREE-enriched pattern with pronounced negative Eu anomalies (Liu et al., 2013a). (2) High TFeO content (>1.0%) and TFeO/MgO ratios (>1) (King P L et al., 1997). (3) Formation at elevated temperatures (Loiselle M C et al., 1979). The Late Triassic light flesh-red monzogranites in the northern part of the Lalinggaolihe mining area exhibit high SiO2 content (75.72%–77.36%), high alkalinity (K2O + Na2O content in the range of 7.51%–8.39%), low P2O5 (0.02%–0.03%), and marked depletion in CaO (0.58%–1.15%) and MgO (0.20%–0.26%) (Table 1). These rocks are also depleted in Sr, Ba, and Eu (Figure 7B); contain TFeO more than 1.0%; and have an average TFeO/MgO ratio greater than 1. In the chondrite-normalized REE patterns, the curves display a “swallow-shaped” pattern with prominent negative Eu anomalies, consistent with A-type granite characteristics (Zhang et al., 2025). A Ga/Al ratio >2.6 (northern samples: 2.61–2.79) further supports their classification as A-type granites (Whalen et al., 1987). Additionally, A-type granites are typically formed under high-temperature conditions, which is a critical distinguishing feature from other granite types. In this study, the zircon saturation temperature was calculated using the formula by Watson and Harrison (1983): TZr (°C) = 12,900/[2.95 + 0.85M + ln (496000/Zrmelt)] − 273.15, where M = (Na + K + 2Ca)/(Al × Si). Zircon Ti-inclusion temperatures were calculated using the formula by Watson and Harrison (2005): TTi-in-Zr (°C) = (5,080 ± 30)/[(6.01 ± 0.3) − ln (TiZircon)] – 273. As shown in Table 2, the average TZr of the northern monzogranites is 811 °C, which is higher than typical S-type (764 °C) and I-type (781 °C) granites. These samples exhibit marked LREE/HREE fractionation with a right-leaning pattern. They are depleted in LILEs (e.g., Sr) and HFSEs (e.g., U, Zr, Hf, Nb, Ta) but are strongly enriched in Rb (Figure 7B). The depletion of HFSEs suggests crustal contamination, whereas Sr depletion indicates residual plagioclase in the source region. The Rb enrichment implies significant magmatic differentiation. On granite classification diagrams (Figures 9A–D), all northern samples plot within the A-type granite field. Based on geochemical evidence—including high alkalinity, negative Eu anomalies, elevated temperatures, and REE patterns—the intrusive rocks in the northern Lalinggaolihe mining area are classified as A-type granites. Their geochemical signatures align with the established criteria for A-type granite formation in non-orogenic, high-temperature tectonic settings.

Figure 9. Comprehensive discrimination diagram of granite categories. (A,B) Discrimination diagram of differentiated granite; (C,D) Discrimination diagram of A-type granite.

The typical rock association of I-type granites is diorite–monzonite (Ma et al., 1992), with amphibole as the marker mineral. These granites often show quasi-aluminous to weakly peraluminous characteristics (A/CNK <1.1). The diorites from the southern area have low SiO2 content (54.82%–60.48%), classifying them as neutral rocks. They are relatively rich in calcium and magnesium (CaO: 4.96%–7.22%; MgO: 2.74%–5.16%) and display weak negative Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.64–0.84). The A/CNK values range from 0.82 to 0.90, with moderate total alkali content and K2O/Na2O ratios between 0.59 and 0.9, showing relatively sodium-rich characteristics—different from typical A-type granites. The average TZr (°C) value is 724 °C, similar to that observed in I-type granites (Gao et al., 2014). By contrast, the monzogranites and granodiorites in the southern mining area are rich in characteristic minerals such as amphibole and biotite. These rocks are rich in alkali and poor in calcium and magnesium, corresponding to high potassium calc-alkaline rocks. They are depleted in LILEs, such as Sr, and HFSEs, such as U, Nb, and Ta, but rich in LILE Rb, differentiating them from the diorites in the southern mining area.

According to previous studies, highly differentiated I- and A-type granites exhibit similar characteristics (Jia et al., 2009), such as depletion in calcium and magnesium, enrichment in LREEs, and depletion in Nb, Ta, and U. The monzogranites and granodiorites in the southern mining area display these features. However, in granite classification diagrams (Figures 9A–D), both rock types fall into the I-type granite field, suggesting they represent highly differentiated I-type granites. Whalen et al. (1987) and Wang et al. (2000) pointed out that highly differentiated I-type granite exhibits different characteristics from A-type granite, such as lower TFeO content (<1.0%), lower zircon saturation temperature (average 764 °C), high Rb content (>270 μg g−1) and relatively low Ba, Sr, and Ga contents and Ga/Al values (Sun et al., 2021). The TFeO contents of the monzogranites and granodiorites are less than 1.0%, and they show relatively low Sr and Ga contents. Their average TZr (°C) values are 739 °C and 746 °C, respectively, further distinguishing them from typical A-type granites. In granite classification diagrams (Figures 9A,B), both rock types fall within the field of differentiated granites. Overall, their geochemical signatures are more consistent with those of highly differentiated I-type granites. This is consistent with the characteristics of I-type granites formed in the post-collision environment of the Early Devonian in the East Kunlun region (Zhao et al., 2008). Therefore, we conclude that the rock mass in the southern mining area belongs to I-type granites.

5.3 Magma source

According to previous studies, A-type granites have various genetic modes and are mainly classified into three types: (1) differentiation of mantle-derived magma (Liu et al., 2013a); (2) partial melting of felsic crust, that is, crustal processes (Collins et al., 1982); (3) interaction between mantle- and crust-derived magmas (Frost and Frost, 1997). A-type granites formed by the separation and crystallization of mantle-derived magma are associated with large-scale basic and ultrabasic rocks of the same period (Turner et al., 1992). However, the rock mass in the northern part of the mining area is mostly moderately acidic, and no large-scale basic–ultrabasic rocks of the same period have been found. This suggests that mantle-derived magma differentiation is unlikely to be the primary genesis mechanism. Trace elements, which are relatively stable and less affected by continental crustal contamination and later alteration, can reflect the source characteristics to a certain extent (Wang et al., 2006). The rock body in the northern area is rich in trace element Rb and depleted in Ba, Nb, and Ta. The negative Ba anomaly typically indicates partial melting of crustal rocks (Zhang et al., 2016b). Furthermore, the average Nb/U and Ce/Pb values of the light flesh-red monzogranites are 3.1 and 2.6, respectively, which are significantly different from those of the original mantle (the average values are approximately 30 and 9, respectively) but are closer to those of the average crust (the average values are approximately 10 and 4, respectively) (Hofmann et al., 1986). This further reflects that it mainly originates from the partial melting of felsic crustal rocks. The negative Nb and Ti anomalies provide additional evidence for crust-derived magmatism. The Nb/Ta ratio is approximately 17.5 for mantle melts and approximately 11 for continental crust. The light flesh-red monzogranites in the mining area are depleted in HFSEs such as Nb and Ta, with an Nb/Ta ratio of 9.0–10.5, indicating that crust-derived magmatism may be dominant, although with some contribution from mantle-derived materials (Geng et al., 2025). Moreover, the Rb/Sr ratio of the pluton is 2.7, which is lower than the crustal ratio (5.36–6.55) (Rudnick and Fountain, 1995), implying the mixing of mantle-derived materials into the magma (Li Y. Z. et al., 2015). These characteristics are consistent with those observed in Late Triassic A-type granites from the Yemaquan area, which are interpreted as products of mixed crust and mantle sources (Gao et al., 2014).

I-type granites have two main origins: (1) underplating of mantle-derived magma, resulting in the melting of crustal materials to form I-type granites (Wu et al., 2003a; 2003b; Richards, 2011; Wang et al., 2014); (2) intrusion of mantle-derived magma into the lower crust, where it mixes with crust-derived magma to form crust–mantle mixed magma, which separates and crystallizes in the later stage to form I-type granite (Champion and Chappell, 1992; Qiu et al., 2008). For the chemical characteristics, REE fractionation is pronounced in the rock mass from the southern mining area, with a right-leaning trend. This suggests the presence of residual plagioclase in the magma source area, indicating that the magma may originate under shallow, low-pressure conditions (Zhang et al., 2007). The southern gray–white monzogranites and granodiorites exhibit relatively high SiO2 contents (73.42%–76.86% and an average δEu value of 0.50, indicating a moderate negative Eu anomaly. The average Nb/U and Ce/Pb ratios are 5.8 and 2.3, and 1.2 and 3.5, respectively, which are significantly different from those of the original mantle but closely resemble average crustal values (Hofmann et al., 1986). These characteristics suggest that the magma was mainly derived from the remelting of crustal materials. The dark diorites have a relatively low SiO2 content (54.82%–60.48%), and its Sr content ranges from 331 × 10−6 to 355 × 10−6, with an average value of 340 × 10−6, which is higher than the average value of the mantle (17.8 × 10−6; Taylor and McLennan, 1985), indicating that its original magma is unlikely to have been solely derived from the mantle. This implies that its main magma source area is the crust. The Mg# value is often used to assess the contribution of mantle-derived substances to the crust-derived magmas (Frost et al., 2001). The Mg# values of the gray–white monzogranites, granodiorites, and diorites in the southern part of the mining area range from 31.13 to 61.23, 23.54 to 55.03, and 43.14 to 58.27, respectively. These values are generally higher than those expected from the melt produced by partial melting of the pure basic lower crust (Mg# < 40; Rapp and Waston, 1995), suggesting the contribution of mantle-derived magma (Li et al., 2021). The average Nb/Ta and Nd/Th ratios for the three are 13.68, 9.46, and 12.88, and 1.18, 1.42, and 2.48, respectively, which are smaller than those of mantle-derived rocks (Nb/Ta = 17.5; Green, 1995) and crust-derived rocks (Nd/Th = 3), indicating that mantle materials were involved in the formation of the southern rock mass (Geng et al., 2025). Overall, the southern rock mass of the mining area shows the characteristics of mixed crust–mantle origin, which is similar to those of the I-type granite formed in the early Devonian post-collisional background in the East Kunlun Mountains (Zhao et al., 2008).

Zircon Hf isotopes, because of their good stability, can be used as a reliable tool for investigating the sources of magmatic rocks (Griffin et al., 2002). Combined with Hf isotope results, the εHf(t) values of the light flesh-red monzogranites in the northern mining area range from −4.17 to −1.2. Similarly, εHf(t) values of the gray–white monzogranites in the southern mining area range from −3.54 to 1.10, those of the gray–white granodiorites from −4.3 to −0.27, and those of the dark diorites from −2.86 to −1.16. The εHf(t) values are mostly negative and close to zero (Figure 10A), indicating that the rock mass material is mainly derived from the remelting of ancient crustal material, with the mixing of mantle-derived materials occurring simultaneously (Yi et al., 2025). The εHf(t) values of Hutouya, Yemaquan, and Niukutou, which are located close to the Lalinggaolihe iron ore deposit, are concentrated in the range of −5 to 1.1, showing the characteristics of crust–mantle mixing. This suggests that mantle materials may have contributed to the Early Devonian and Late Triassic magmatic activities in the Lalinggaolihe iron polymetallic mining area. In the εHf(t) vs. zircon U–Pb age correlation diagram (Figure 10B), εHf (t) values are mainly located below the chondrite line and above the crustal evolution line, showing trends similar to magmatic rocks from Hutouya, Galinge, Yemaquan, and Niukutou. This is consistent with the understanding that magmatic rocks developed in the East Kunlun region during the Early–Middle Devonian to Middle–Late Triassic periods were likely formed through crust–mantle magma mixing (Mo et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008).

Figure 10. Histogram of zircon εHf(t) distribution (A) and εHf(t)–zircon U–Pb age correlation diagram (B) for the granitic body in the Lalinggaolihe iron ore area.

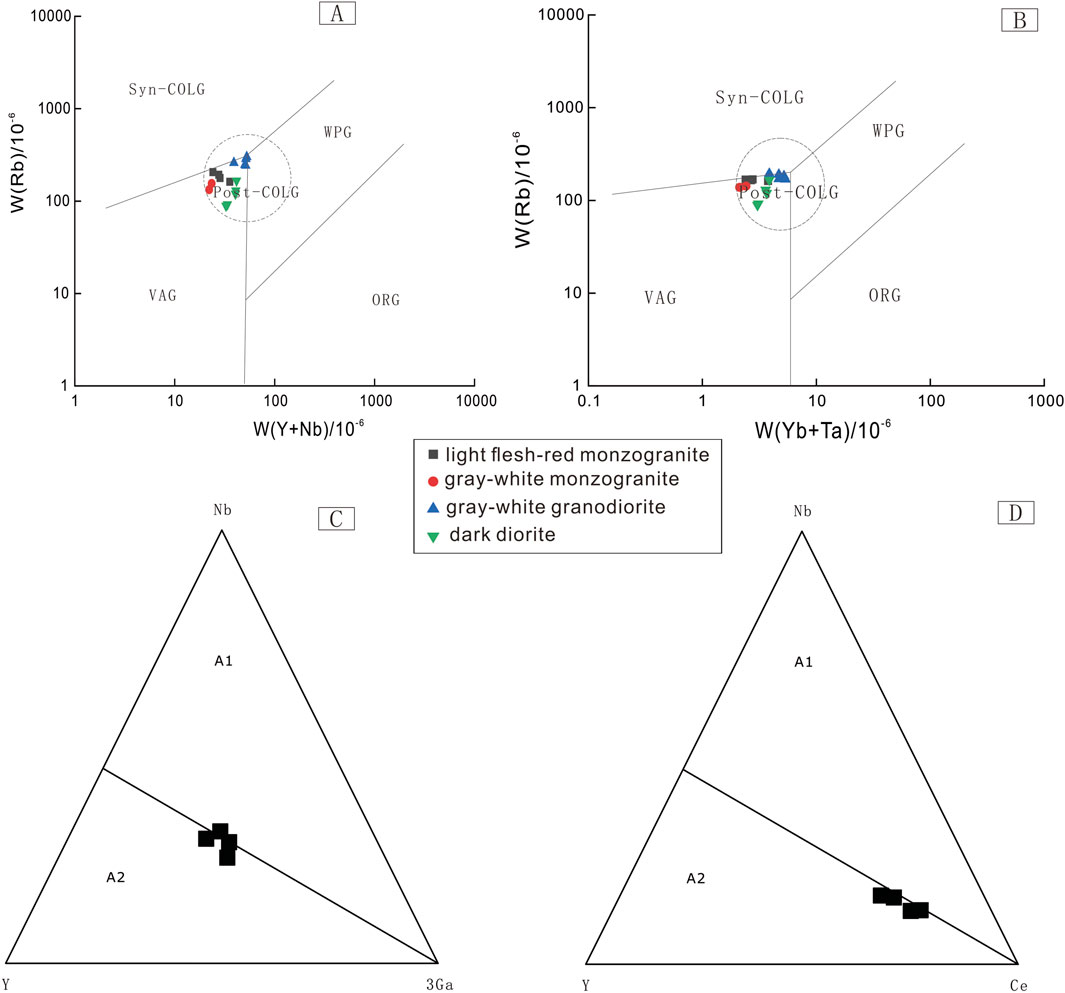

5.4 Tectonic environment

According to previous studies, the East Kunlun region has undergone two major evolutionary processes: the Proto-Tethys and Paleo-Tethys (Li et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2012) and two tectono–magmatic cycles—Early Paleozoic and Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic (Mo et al., 2007). In the Early Cambrian, the Proto-Tethys Ocean began to form and expand in the East Kunlun region (Mo et al., 2007). From the end of the Early Cambrian to the Late Ordovician, the formation and evolution of the Proto-Tethys Ocean to the Paleo-Tethys Ocean resulted in a polar subduction from south to North (Li et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2018; Song et al., 2015), followed by a closed collision (Lu et al., 2005). These tectonic processes resulted in the development of a volcanic magmatic arc (Cui et al., 2011), leading to the formation of a large number of granites with volcanic arc background (Li et al., 2007). The Silurian to Devonian period is generally considered to be the period when the Proto-Tethys Ocean closed and collision orogenesis occurred in the East Kunlun region (Li et al., 2024; Mo et al., 2007). However, the timing and duration of subduction and final closure of the Proto-Tethys Ocean remain subjects of debate (Guo et al., 2024). For example, Mo et al. (2007) suggest that the subduction of the Proto-Tethys Ocean crust and subsequent closed collision occurred at 513–420 Ma. Contrastingly, Liu et al., 2013b argue that subduction continued into the Early Silurian in the East Kunlun region (Liu et al., 2013b). Guo et al. (2024), based on studies of the Walega granites, propose that the Proto-Tethys Ocean was not completely closed at 414 Ma. Some scholars believe that the closure of Proto-Tethys Ocean and subsequent continental collision occurred at 432.0 ± 2.6 Ma (Liu et al., 2013b). However, it is widely acknowledged that the tectonic evolution of this ancient ocean caused the explosion of collisional magmatism and large-scale mineralization during the Silurian and Devonian periods (Zhong et al., 2025b), resulting in the formation of a series of ore deposits such as Xiarihamu, Kaerqueka, Niukutou, Baidungou (Han et al., 2024), and Lalangmai Tungsten Mine (Teng et al., 2025). The zircon U–Pb dating of the rock body in the southern part of the Lalinggaolihe mining area yields ages ranging from 414.6 to 417.1 Ma, indicating an Early Devonian formation. On Rb-Y + Nb and Rb-Yb + Ta structure discrimination diagrams, the samples generally fall in the post-collision granite field (Figures 11A,B). The relatively high Yb content and low Sr content further indicate its association with crustal tensile thinning (Zhang et al., 2014). Therefore, we infer that the Early Devonian pluton in the Lalinggaolihe mining area was formed in a post-collisional extensional tectonic environment. This implies that the collision orogeny in the Qimantag region had ended before the Early Devonian, and the southern iron-polymetallic pluton of the Lalinggaolihe mining area was formed in this stage.

Figure 11. Tectonic setting discriminant diagrams for granites (A,B) and subtype discriminant diagrams for A-type granite (C,D). ORG, Ocean ridge granite; WPG, Within-plate granite; VAG, Volcanic arc granite; Syn-COLG, Syn-collisional granite; Post-COLG, Post-collisional granite.

Many studies have shown that post-collision tectonism occurred after the closure of the Proto-Tethys Ocean and lasted until approximately 370 Ma (Kou et al., 2017; Zhang Y. L. et al., 2018; Duan et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). The Palaeo-Tethys Ocean is believed to have formed during the Late Devonian, whereas the Yaziquan ophiolite (Yang, 1999) is considered to be a fragment of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean (Zhong, 2024). During the Carboniferous–Permian, the East Kunlun region subsided into an epicontinental sea, depositing a set of shallow coastal marine sediments, predominantly composed of carbonate rocks, indicating a relatively stable environment. From the Middle–Late Permian to Early Triassic, the Paleo-Tethys Ocean entered a subduction–orogenic stage (260–240 Ma), during which a set of arc granites developed. By the Middle Triassic, this tectonic regime had evolved from subduction to collision (Guo et al., 2019). The Middle–Late Triassic is marked by a transition from collisional to post-collisional stage, forming numerous Middle–Late Triassic intrusive rocks. These include syenite in the Langmaitan area of East Kunlun (231.5 ± 1.7 Ma; li et al., 2021), the Xiaozaohuo syenite (226 ± 1 Ma; Chen et al., 2018), Dachagou monzonite (233 ± 2 Ma; Tang et al., 2018), and esitic volcanic breccia tuff in the southern Galinge area (222.2 ± 2.1 Ma; Zhang J. et al., 2018), and Yizigou monzonite (224 ± 4 Ma; Wang et al., 2020). The monzonitic granites in the northern part of the Lalinggaolihe mining area were likely formed under this background. In the A-type granite discrimination diagrams (Figures 11C,D), the samples of monzogranites from the northern mining area mainly fall within the A2 granite field, suggesting that it was formed in an extension environment (Wang et al., 2024). Similarly, in the tectonic environment discrimination diagrams (Figures 11A,B), the samples fall within the post-collision granite field. Therefore, we infer that the Late Triassic pluton in the Lalinggaolihe mining area was formed in a post-collisional extensional tectonic environment. During the Middle–Late Triassic, due to the existence of a thickened lower crust, the geodynamic balance caused continuous lithosphere disintegration, leading to the collapse of the East Kunlun orogenic belt. This transition into the post-arc extensional environment (Ma et al., 2025) caused the upwelling of the asthenospheric mantle. The influx of mantle magma brought substantial metallogenic materials into the crust, as a result, it causes mantle upwelling in the asthenosphere and bottom intrusion, forming one or more massive basic magma chambers. Due to the mantle derived basic magma of the bottom intrusion providing a heat source for the lower crust, the pre depleted refractory rocks in the lower crust partially melted, producing high silica, high alkali, and HFSE rich felsic melts (Figure 7B). Afterwards, mantle derived magma underwent varying degrees of mixing with these crustal melts. Therefore, the εHf (t) values are mostly negative and close to 0 (Figure 10B). Finally, the mixed magma underwent a separation crystallization process dominated by potassium feldspar, forming the A-type granite in this study area (Halder et al., 2021; Huppert et al., 1998).

5.5 Magmatism and mineralization

Field geological surveys and zircon U–Pb geochronology studies reveal that there are two sets of magmatic batholiths with significant age differences in the Lalinggaolihe mining area: the Indosinian granitic batholith in the north and the Caledonian granitic batholith in the south. The polymetallic ore bodies are primarily hosted within the skarn zones of the Ordovician Tanjianshan Formation (O3tnc), specifically within the graywackes and marbles of the region. However, the relationship between the ore-bearing skarns and the intrusive rock bodies remains unclear, as the skarns are spatially distant from the intrusive contact zones. Recent U–Pb dating of garnet from diopside–garnet skarn-type iron ores yielded an age of 219.5 ± 6.6 Ma (unpublished data), indicating a close temporal association between the mineralization and Late Triassic intrusive activity. Numerous studies have demonstrated that polymetallic mineralization in the Qimantag region is closely linked to Mesozoic magmatic activity, particularly during the Early–Middle Devonian and Late Triassic periods.

1. The LA-ICP-MS analyses indicate that the U-Pb zircon ages of Early–Middle Devonian (type I) monzogranite and granodiorite are between 415 and 386 Ma, forming skarn-type iron-polymetallic deposits and porphyry-type copper–molybdenum deposits, such as those in the northern ore belts of Yemaquan, Niukutou, and Kaerqueka.

2. During the Middle–Late Triassic, granodiorite–quartz diorite–monzogranite intrusions (type I or type A) occurred, forming skarn-type iron polymetallic deposits (such as the southern ore belts of Yemaquan, Galinge, Jingren, and Tawenchahan), as well as the stratabound skarn-type lead–zinc deposits related to magmatic hydrothermal activity (such as Weibao and Hutouya), with a diagenetic and metallogenic age of 239–210 Ma (She et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Feng et al., 2010; 2011; 2012b; Gao et al., 2012). This period represents the most important polymetallic metallogenic phase in the Qimantag area. Pb isotope data indicate that lead in the Galinge, Hutouya, Kaerqueka, Sijiaoyang, Weibao, and other deposits originated from a mixed crust–mantle subduction source area associated with magmatism (Xu, 2010; Huang, 2010; Ma, 2012).

The two phases of magmatic and mineralization activity are interpreted to have occurred during the post-collisional magmatic stages following the closure of the Proto-Tethys and Paleo-Tethys oceans during the Early–Middle Devonian and Middle–Late Triassic, respectively. These events were accompanied by mantle underplating and magmatic mixing, with crust–mantle material exchange potentially providing the large amounts of metallogenic materials required for regional-scale mineralization. The Lalinggaolihe mining area is located within the same mineral belt as the aforementioned deposits. Based on the petrogenetic and mineralization characteristics of the intrusive rocks and ore deposits in the mining area, it is inferred that the mineralization source is closely related to mantle underplating and magmatic mixing. Additionally, the possibility of Early–Middle Devonian skarn-type mineralization in the mining area cannot be ruled out and warrants further exploration.

6 Conclusion

1. The U–Pb ages of monzogranites in the northern part of the Lalinggaolihe mining area are 216.22 ± 0.96 and 215.3 ± 2.1 Ma. The U–Pb ages of monzogranites, granodiorites, and dark diorites in the southern part of the mining area are 415.8 ± 1.3, 417.1 ± 2.8, 416.7 ± 1.9, and 414.6 ± 1.2 Ma. These results indicate that the northern and southern rock bodies were formed in the Early Devonian and Late Triassic periods, respectively.

2. Geochemistry analyses indicate that the monzogranites in the northern mining area belong to high-potassium calc-alkaline rocks, with high formation temperature, and show characteristics of A-type granites. By contrast, monzogranites, granodiorites, and dark diorites in the southern part of the mining area are classified as I-type granites.

3. The monzogranites in the northern mining area were formed during the Late Triassic collision to post-collision stage, involving crust–mantle magma mixing. The rock mass in the south was formed during the Early Devonian post-collision extensional stage, also involving magma mixing. The formation of these two granites is related to the Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic and Early Paleozoic tectono–magmatic cycles in the East Kunlun area, respectively. Mantle underthrusting and magma mixing likely provided a large amount of metallogenic materials for the mining area.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. CC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. XL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. RX: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. DZ: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. HL: Investigation, Software, Writing – review and editing. ZZ: Software, Investigation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

AcknowledgementsWe express our gratitude to the staff and management of Western Mining Group Co., Ltd., for their valuable assistance during fieldwork and sample collection.

Conflict of interest

Author DZ was employed by Western Mining Group Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bai, Y. N., Sun, F. Y., Li, B. L., Li, S. J., and Zhao, T. F. (2016). Zircon U-Pb chronology and geochemistry of the granite porphyry in galinge iron polymetallic deposit, Qinghai province, and their geological significance. Glob. Geol. 35 (4), 941–953.

Bai, S. L., Liu, G. Y., Li, J. L., Zhang, F., and Wang, Y. (2019). Prospecting indicators for deep-seated iron-polymetallic deposits in low-gradient magnetic anomaly zones of shaqiu area, East Kunlun. Mineral. Explor. 10 (1-2), 118–124.

Champion, D. C., and Chappell, B. W. (1992). “Petrogenesis of felsic I-type granites: an example from northern Queensland,” in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. (Bath, United Kingdom: Geological Society Publishing House), 83 (1-2), 115–126. doi:10.1130/spe272-p115

Chappell, B. W., and White, A. J. R. (1992). I- and S-type granites in the lachlan fold belt, southeastern Australia. Geol. Soc. Am. Special Pap. 272, 1–26. doi:10.1130/SPE272-p1

Chen, J. L., Wang, Z. Q., Zeng, Z. C., Xu, X. Y., and Li, S. (2004). Geochemical characteristics and tectonic significance of the mengchuan rock body in the west qinling. Geol. Bull. China 23 (2), 139–145.

Chen, C. H., Liu, Y., and He, B. B. (2011). Assessment of polymetallic mineral resource potential in yemaquan area, East Kunlun. Metal. Mine (2), 90–94.

Chen, B., Li, W. Y., Li, D. M., Qian, B., and Gao, Y. B. (2012). Zircon U-Pb dating and geochemistry of granite porphyry in kaerqueka copper-molybdenum deposit of qimantage and its significance. Geol. China 39 (4), 1013–1028.

Chen, J., Hu, J. C., Lu, Y. Z., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2018). Geochronology, geochemical characteristics and geological significance of Mo-mineralized syenogranite in Xiaozhaohuo area, East Kunlun. Gold Sci. Technol. 26 (4), 465–472.

Chen, H. F., Li, R. S., Ji, W. H., Zhang, J., and Chen, S. J. (2020). Zircon U-Pb chronology, geochemistry and geological significance of granite porphyry in kaerqueka copper-molybdenum deposit, East Kunlun. Geol. China 47 (3), 612–628.

Collins, W. J., Beams, S. D., White, A. J. R., and Chappell, B. W. (1982). Nature and origin of A-type granites with particular reference to southeastern Australia. Contributions Mineralogy Petrology 80 (2), 189–200. doi:10.1007/bf00374895

Cui, M. H., Wang, T., Guo, L., Tong, Y., and Zhang, J. J. (2011). Geochronology, geochemistry and tectonic implications of the early Paleozoic volcanic rocks in the East Kunlun orogenic belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 27 (11), 3361–3376.

Dong, Y. P., Hui, B., Sun, S. S., Li, R. X., and Wang, K. Y. (2022). Multi-stage composite orogenic processes of the proto-paleo-tethys in the central China orogenic system. Acta Geol. Sin. 96 (10), 3426–3448.

Duan, X. Y., Pei, X. Z., Li, R. B., Liu, C. J., and Chen, Y. X. (2019). The termination of the proto-tethyan orogen in the East Kunlun orogen: constraints from the magmatic and metamorphic events. Geol. J. 54 (6), 3456–3478.

Einaudi, M. T., Meinert, L. D., and Newberry, R. J. (1981). Skarn deposits. Econ. Geol. 75, 317–391. doi:10.5382/av75.11

Feng, C. Y., Wang, S., Li, S. J., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2010). Molybdenite Re-Os dating of the hutouya lead-zinc polymetallic deposit in qimantag, Qinghai, and its geological significance. Acta Petrol. Sin. 26 (11), 3363–3372.

Feng, C. Y., Zhang, D. Q., Xiang, X. K., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2011). Molybdenite Re-Os dating of the kaerqueka copper-molybdenum deposit in qimantag, Qinghai, and its geological significance. Acta Geol. Sin. 85 (2), 245–255.

Feng, C. Y., Wang, X. P., Li, W. Y., Li, D. M., and She, H. Q. (2012a). Zircon U-Pb age and geochemistry of granodiorite in tawenchahan skarn iron-polymetallic deposit, Qinghai province, and their significance. Mineral. Deposits 31 (4), 745–762.

Feng, C. Y., Li, G. C., Ma, S. C., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2012b). Metallogenic epoch of skarn-type iron-polymetallic deposits in the qimantag area, Qinghai, and its geological significance. Acta Geol. Sin. 86 (8), 1295–1308.

Feng, C. Y., Wang, H., Qu, H. Y., Li, R. X., and Wang, K. Y. (2024). Paleo-tethyan evolution and characteristics of large-scale metallogeny in the East Kunlun orogenic belt. Mineral. Deposits 43 (6), 1316–1335.

Frost, C. D., and Frost, B. R. (1997). Reduced rapakivi-type granites: the tholeiite connection. Geology 25 (7), 647–650. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0647:rrtgtt>2.3.co;2

Frost, B. R., Barnes, C. G., Collins, W. J., Arculus, R. J., Ellis, D. J., and Frost, C. D. (2001). A geochemical classification for granitic rocks. J. Petrology 42 (11), 2033–2048. doi:10.1093/petrology/42.11.2033

Gao, Y. B., Li, W. Y., Qian, B., Li, D. M., and Ma, X. F. (2012). Zircon U-Pb dating and geochemical characteristics of granodiorite in galinge iron polymetallic deposit of East Kunlun and its significance. Mineral. Deposits 31 (5), 1013–1028.

Gao, Y. B., Li, W. Y., Li, D. M., Qian, B., and Ma, X. F. (2013). Zircon U-Pb dating and geochemical characteristics of granodiorite in kaerqueka copper-molybdenum deposit of qimantage and its significance. Mineral. Deposits 32 (1), 63–78.

Gao, Y. B., Li, W. Y., Qian, B., Li, R. X., and Wang, K. Y. (2014). Geochronology, geochemistry and Hf isotopic characteristics of granitoid rocks related to the yemaquan iron deposit, East Kunlun. Acta Petrol. Sin. 30 (6), 1647–1665.

Gao, Y. B., Li, W. Y., Li, D. M., Qian, B., and Wang, Y. W. (2014). Zircon U-Pb dating and geochemical characteristics of granodiorite in yemaquan iron polymetallic deposit of East Kunlun and its significance. Mineral. Deposits 33 (4), 739–756.

Gao, Y. B., Li, W. Y., Li, K., Li, D. M., and Qian, B. (2017). Magmatic activity and metallogenesis during early Mesozoic Continental crustal accretion in qimantag, East Kunlun. Mineral. Deposits 36 (2), 463–482.

Geng, J., Wang, Y. W., Wang, X. Y., Li, Z. W., and Chen, X. Y. (2025). Chronology, source, petrogenesis and geodynamic background of Hercynian magmatic rocks in the niukutou area, Qinghai. Chin. J. Geol. 60 (1), 165–190.

Green, T. H. (1995). Significance of Nb/Ta as an indicator of geochemical processes in the crust-mantle system. Chem. Geol. 120 (3-4), 347–359. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(94)00145-x

Griffin, W. L., Wang, X., Jackson, S. E., Pearson, N. J., O'Reilly, S. Y., Xu, X., et al. (2002). Zircon chemistry and magma mixing, SE China: in-situ analysis of Hf isotopes, tonglu and pingtan igneous complexes. Lithos 61 (3-4), 237–269. doi:10.1016/s0024-4937(02)00082-8

Guo, T. Z., Wang, G. H., Wang, Y., Ma, Z. G., and Wang, J. P. (2011). Zircon U-Pb dating and geological significance of granodiorite in wulanuzhuer copper-polymetallic deposit, East Kunlun. Geol. Explor. 47 (4), 579–589.

Guo, X. Z., Jia, Q. Z., Li, J. C., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2019). Geochronology, geochemistry and tectonic significance of the zhamaxiuma syenogranite in East Kunlun. Acta Geol. Sin. 93 (4), 830–842.

Guo, X. M., Ding, F., Fan, T., Li, R. X., and Wang, K. Y. (2024). Subduction timing of the proto-tethys ocean in the Eastern East Kunlun: constraints from zircon U-Pb geochronology and geochemistry of walega granitic rocks. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 51 (2), 222–246.

Halder, M., Bhowmik, S. K., and Chaudhuri, A. (2021). Tectonic evolution of the karakoram terrane in the himalayan-tibetan orogen: a critical review. Geosci. Front. 12 (1), 53–90.

Han, Z. H., Li, R. S., Ji, W. H., Zhang, J., and Chen, S. J. (2020). Zircon U-Pb chronology, geochemistry and geological significance of monzogranite in wulanuzhuer mining area, East Kunlun. Geol. China 47 (2), 352–367.

Han, Y., Wang, Q. L., Xie, H. L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2024). Petrogeochemistry, zircon U-Pb age, Hf isotopic characteristics and tectonic implications of the baitougou granite in East Kunlun. Acta Petrologica Mineralogica 43 (6), 1448–1464.

Hawkesworth, C. J., and Kemp, A. I. S. (2006). Using hafnium and oxygen isotopes in zircons to unravel the record of crustal evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 241 (3-4), 531–542.

Hofmann, A. W., Jochum, K. P., Seufert, M., and White, W. M. (1986). Nb and Pb in Oceanic basalts: new constraints on mantle evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 79 (1-2), 33–45. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(86)90038-5

Hu, Z., Liu, Y., Gao, S., Liu, W., Yang, L., Zhang, W., et al. (2012). Improved in situ Hf isotope ratio analysis of zircon using newly designed X skimmer cone and jet sample cone in combination with the addition of nitrogen by laser ablation multiple collector ICP-MS. J. Anal. Atomic Spectrom. 27 (9), 1391–1399. doi:10.1039/c2ja30078H

Huang, L. (2010). Geological and geochemical characteristics and genesis of the weibao lead-zinc deposit in Qinghai province (Master's thesis). Beijing: China University of Geosciences.

Huppert, H. E., and Sparks, R. S. J. (1988). The generation of granitic magmas by intrusion of basalt into Continental crust. J. Petrology 29 (3), 599–624. doi:10.1093/petrology/29.3.599

Jia, X. H., Wang, Q., and Tang, G. J. (2009). Research progress and significance of A-type granites. Geotect. Metallogenia 33 (3), 465–480.

Jing, Z. C. (2013). Characteristics and prospecting direction of iron-copper deposits in lower lalinggaolihe area (Master's thesis). Beijing: China University of Geosciences.

King, P. L., White, A. J. R., Chappell, B. W., and Allen, C. (1997). Characterization and origin of aluminous A-type granites from the lachlan fold belt, southeastern Australia. J. Petrology 38 (3), 371–391. doi:10.1093/petroj/38.3.371

Kou, G. C., Meng, F. C., Feng, X. T., and Wang, Z. Q. (2017). Post-collisional extension of the proto-tethyan orogen in the East Kunlun: evidence from magmatic activity. Geol. Bull. China 36 (7), 1123–1135.

Li, D. P., Zhou, X. K., Zhao, Y., Du, A. G., and Hu, J. M. (2003). Ordovician tectonic-sedimentary environment and tectonic evolution on the northern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geol. Bull. China 22 (10), 769–776.

Li, W. Y., Li, S. G., Guo, A. L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2007). Zircon SHRIMP U-Pb dating and trace element geochemistry of kuhai gabbro and derni diorite in the eastern kunlun south tectonic belt, Qinghai: constraints on the southern boundary of the late neoproterozoic–early Ordovician multi-island ocean in qilian-qaidam-kunlun region. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 50 (Suppl. 1), 288–294.

Li, R. S., Ji, W. H., Zhao, Z. M., Wang, Y. H., and He, S. P. (2008). Division of tectonic units of the kunlun orogenic belt and their characteristics. Geol. Bull. China 27 (10), 1617–1627.

Li, S. J., Sun, F. Y., Wang, L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2008). Geological characteristics and genesis of the weibao lead-zinc deposit in the qimantag area, East Kunlun. Geol. Explor. 44 (4), 32–38.

Li, J. Q., Li, W. Y., Gao, Y. B., Li, D. M., and Feng, C. Y. (2016). Zircon U-Pb dating and geochemistry of monzogranite in kaerqueka molybdenum-polymetallic deposit, qimantage, Qinghai, and their geological significance. Mineral. Deposits 35 (2), 287–306.

Li, R. B., Pei, X. Z., Pei, L., Li, Z. C., Chen, G. C., Chen, Y. X., et al. (2018). The early Paleozoic tectonic evolution of the East Kunlun orogen, northern Tibet: insights from magmatic and sedimentary rocks. Gondwana Res. 58, 1–17.

Li, J. D., Wang, B., Li, Y., Feng, J. K., and Ma, D. F. (2019). Zircon U-Pb dating and geological significance of granite porphyry in the niukutou polymetallic deposit, Qinghai province. Geol. China 46 (5), 1089–1101.

Li, J. C., Guo, X. Z., Kong, H. L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2021). Geochronology, geochemical characteristics and geological implications of A-type granite in langmaitan area, East Kunlun. Acta Geol. Sin. 95 (5), 1508–1522.

Li, W. F., Wang, Q., Wang, B. Z., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2024). Chronology, geochemical characteristics and geological significance of pyroxene-hornblendite in the alkaline complex of dagele area, East Kunlun. Geotect. Metallogenia 48 (1), 144–167.

Li, K., Gao, Y. B., Wang, C. L., Wang, G. H., and Wang, Z. Q. (2015). Zircon U-Pb age and its geological significance of granodiorite in hutouya polymetallic ore deposit, qimantage area, Qinghai province. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 34 (1), 1–9. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3657.2013.04.004

Li, Y. Z., Kong, H. L., Li, J. C., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2015). Geochemical characteristics and U-Pb geochronology of the yueliangwan plagiogranite in wulonggou mining area, Qinghai. Bull. Mineralogy, Petrology Geochem. 34 (2), 401–409.

Liu, B., Ma, C. Q., Liu, Y. Y., Huang, J., Jiang, H. A., and Wang, Z. Q. (2012). Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of early paleozoic post-collisional granites in East Kunlun orogenic belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 28 (12), 4035–4050.

Liu, B., Ma, C. Q., Guo, P., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2013a). Identification of middle Devonian A-type granite and its tectonic significance in East Kunlun. Earth Sci. 38 (5), 947–962.

Liu, B., Ma, C. Q., Jiang, H. A., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2013b). Transition from early Paleozoic Oceanic crust subduction to collision orogeny in East Kunlun: evidence from huxiaoqin mafic rocks. Acta Petrol. Sin. 29 (6), 2093–2106.

Liu, J. N., Yang, Y. Q., Li, J. B., Li, Y., and Ma, S. K. (2018). Zircon U-Pb chronology and geochemistry of the granite porphyry in yemaquan skarn iron-polymetallic deposit, East Kunlun, and their geological significance. Acta Petrol. Sin. 34 (5), 1299–1316.

Liu, B. S., Kou, L. L., Li, C. L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2025). Zircon U-Pb dating, Hf isotopic composition and prospecting significance of amphibolite gabbro in the zhengguang gold deposit, Heilongjiang. Geoscience 39 (2), 345–359.

Liu, X. H., Liu, D. L., Lou, Y. L., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2025). Geochronology, Hf isotope, geochemistry and petrogenesis of the baimashan complex pluton in central Hunan. Earth Sci. 50 (2), 609–620.

Loiselle, M. C., and Wones, D. R. (1979). Characterization and origin of anorogenic granites. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 11 (2), 448–468.

Lu, J. P., Xu, H., Zhou, F. X., and Li, Q. (2005). Characteristics and tectonic setting of Ordovician volcanic rocks in the eastern part of the north qilian Mountains. Geol. Bull. China 24 (5), 412–418.

Ma, S. C., Feng, C. Y., Li, G. C., Wang, Y., and Zhang, F. (2012). Lead isotopic compositions and their genetic significance of the kaerqueka copper-molybdenum deposit in qimantag, Qinghai. J. Mineralogy Petrology 32 (4), 78–85.

Ma, Y. L., Zhao, Z. Y., Tan, Y., Li, R. X., and Wang, K. Y. (2017). Analysis of copper-polymetallic ore prospecting potential in northern lalinggaoli area, Qinghai. West. Resour. (1), 41–43.