Abstract

The Lower Congo Basin, a salt-rich passive-margin basin, displays complex coupling between salt tectonics and sedimentation that strongly controls hydrocarbon systems, yet the deformation mechanisms and spatiotemporal evolution of its Aptian salt structures remain insufficiently constrained. Here we combine basin-scale physical analogue experiments with structure-scale three-dimensional discrete element method (3D DEM) simulations to investigate the gravity-driven deformation and three-dimensional kinematics of salt structures in the central Lower Congo Basin. The analogue models reproduce seaward gravitational spreading of the Aptian salt and overburden followed by contraction triggered by delayed frontal obstruction against volcanic outer highs, whereas the 3D DEM experiments resolve salt–sediment coupling, strain partitioning and salt-flow anisotropy around pre-existing diapirs. The results define a three-phase evolutionary model for passive-margin salt tectonics: (1) a Global Extension phase dominated by salt-raft development and passive diapirism; (2) a Frontal Obstruction phase in which arrested downslope salt flow localizes compressional stresses; and (3) a Compression Propagation phase that produces squeezed and welded diapirs with mushroom and teardrop geometries and associated minibasins. Pre-existing diapirs function as preferential strain sinks and “stress-release windows” that focus velocity anomalies and control the migration of depocenters toward active diapirs, promoting minibasin asymmetry. Comparison with seismic profiles from the central Lower Congo Basin shows good agreement, supporting the predictive value of the models. These findings provide a three-dimensional mechanical framework for the evolution of salt-bearing passive margins and offer guidance for assessing structural controls on hydrocarbon trap development in salt-influenced basins.

1 Introduction

Salt-bearing passive margins are among the most structurally complex sedimentary systems, where gravitationally driven deformation of evaporites interacts with sedimentation to produce a diverse range of structures (Marton et al., 2000; Valle et al., 2001; Vendeville and Jackson, 1992; Jackson and Vendeville, 1994; Brun and Fort, 2011; Jackson and Hudec, 2017). Along the West African margin, the Lower Congo Basin is a prominent example, containing extensive Aptian salt deposits and displaying salt rafts, passive and active diapirs, squeezed pillows, and salt canopies (Cramez and Jackson, 2000; Hudec and Jackson, 2007). Salt rafts are salt-related structures that develop when the overburden above a salt layer undergoes extreme extension, so that the hanging wall and footwall of normal faults become completely detached and translated apart. The resulting fault-bounded blocks are underlain by salt and have a raft-like geometry, with the intervening spaces progressively filled by syn-kinematic sedimentary strata (Séranne and Anka, 2005; Anka et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2020). Salt diapirs, in contrast, are upward-bulging salt structures formed where abundant source salt is available and sustained differential loading drives salt rise through the overburden. Their morphology is controlled by a combination of regional tectonic stress, the sedimentation rate of the overlying strata, the rate of salt supply, and erosion of the overburden (Hudec and Jackson, 2007; Ge et al., 2021; Gou and Liu, 2024; Koyi, 1998; Koyi et al., 2008). These structures develop in response to differential loading, lithospheric tilting, and downslope movement of salt along detachment horizons, and they are further influenced by basement topography, sediment supply, and regional tectonics (Vendeville, 2002; Fort et al., 2004; Adam et al., 2012).

A widely used framework for interpreting salt-related deformation on passive margins divides the margin into three structural domains from landward to seaward: an extensional zone on the upper slope, characterized by listric growth faults and salt rafts; a transitional zone with numerous high-amplitude diapirs and mixed stress regimes; and a contractional zone at the slope toe, where thrusts, folds, salt nappes, and salt canopies dominate (Duval et al., 1992; Fort et al., 2004; Rowan et al., 2004; Hudec and Jackson, 2007; Jackson et al., 2015; Piedade and Alves, 2017). Although this model captures the general organization of salt tectonics, field and seismic observations reveal significant local deviations from this pattern (Jackson et al., 2008; Pilcher et al., 2014).

One notable issue concerns the spatial and temporal balance between extension in the upper slope and shortening in the lower slope. In the Lower Congo Basin, displacement of salt rafts in the extensional domain can exceed 200 km (Pilcher et al., 2014; Rouby et al., 2003), which appears larger than the shortening accommodated by contractional structures alone. Several mechanisms have been proposed to reconcile this apparent imbalance, including partial extension over oceanic crust (Kukla et al., 2018), seaward tilting of basement blocks (Jackson et al., 2000), and obstruction of downslope salt flow by volcanic outer highs (Norton et al., 2016). These explanations highlight the role of both deep crustal processes and post-rift magmatism in shaping salt systems (Pichel et al., 2022). However, spatial heterogeneity persists, particularly in segments of the contractional domain where high-amplitude diapirs occur without associated large-scale thrusts, suggesting that local controls—such as pre-existing diapir geometries, sedimentation patterns, and the timing of frontal obstruction—are also significant (Hudec and Jackson, 2007; Brun and Fort, 2011).

Previous analog and numerical studies have greatly improved understanding of passive margin salt tectonics. Basin-scale analog models have clarified the relationship between lithospheric cooling, margin tilting, and gravitational sliding (Duval et al., 1992; Fort et al., 2004; Smit et al., 2008; Dooley et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2015; Ferrer et al., 2017), while numerical simulations have examined the role of salt thickness, rheology, and sediment loading in diapir evolution (Vendeville and Jackson, 1992; Adam et al., 2012; Pichel et al., 2017; Pichel et al., 2019; Pichel et al., 2022; Eslamirezaei et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Nonetheless, few studies have combined basin-scale analog modeling with structure-scale three-dimensional simulations to investigate how salt deformation evolves from early gravitational spreading to later compression, particularly in settings where frontal obstruction is delayed (Pilcher et al., 2014). In the neighbouring Kwanza Basin, Zhang et al. (2020) used integrated analogue and 3D DEM experiments to simulate basin-scale gravity-driven extension and raft tectonics. Their models successfully reproduced the zonation of extensional, translational and contractional domains, but the contractional sector is dominated by thick thrust-related salt structures and does not capture the high-amplitude, mushroom-shaped diapirs that characterise the proximal contractional domain of the central Lower Congo Basin. Consequently, the mechanics of high-relief diapirs and their interaction with syn-kinematic minibasins in the proximal contractional domain of the central Lower Congo Basin remain poorly constrained.

This study addresses this gap by integrating physical analog modeling with three-dimensional discrete element modeling (3D DEM) to examine the deformation and evolution of Aptian salt structures in the central Lower Congo Basin. The analog experiments simulate initial basinward gravitational spreading followed by contraction induced by delayed frontal obstruction, allowing the observation of transitional and contractional salt structures over time. The 3D DEM complements this by resolving salt–sediment interactions, strain partitioning, and velocity anomalies around pre-existing diapirs under syn-depositional compression. Through this combined approach, the study aims to (1) reconstruct the spatiotemporal evolution of salt structures under changing stress regimes, (2) evaluate the role of obstruction timing in controlling deformation style, and (3) provide insights into the mechanical coupling between salt mobility and sedimentary loading. The results contribute to a better understanding of passive margin salt systems and have direct implications for predicting structural traps in hydrocarbon exploration.

2 Geologic setting

The Lower Congo Basin, situated along the passive continental margin of West Africa, extends offshore from southern Gabon, Congo (Brazzaville), Congo (Kinshasa), and Angola. As part of the continental rift system that formed during the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous breakup of the southern Gondwana supercontinent, the basin has undergone three major evolutionary phases: the rift phase, transitional phase, and passive margin phase (Marton et al., 2000; Valle et al., 2001). The basin is divided into two structural layers by the Aptian salt layer: the pre-salt and post-salt sequences (Fort et al., 2004). Based on stress conditions and salt tectonic styles, the Lower Congo Basin can be further subdivided into three zones: (1) the eastern extensional zone (comprising Cretaceous salt rafts, pre-salt rafts, Neogene salt rafts, and isolated diapirs), (2) the central transitional zone (characterized by salt walls and turtle structures), and (3) the western contractional zone (featuring squeezed diapirs, salt tongues, salt canopies, thickly layered folded salt sheets, and allochthonous salt sheets) (Marton et al., 2000) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Location and distribution of salt tectonic belts of the Lower Congo Basin.

The basement of the Lower Congo Basin consists of Precambrian crystalline rocks. During the rift stage (Valanginian to Aptian), the opening of the South Atlantic led to the development of intracontinental rifting, forming a series of half-grabens and rift lakes. During the this syn-rift stage, normal faulting and crustal thinning established a segmented, seaward-dipping basement surface and an ocean–continent transition (OCT) zone along the margin. These pre-Aptian structures controlled the large-scale basement tilt and the position of the distal salt basin. From the Barremian to Aptian, localized carbonate deposits were formed, while mudstone interbeds were widely deposited during periods of sufficient terrigenous supply. By the late Barremian, the rift lakes were filled with siliciclastic sediments, including sandstone layers (Séranne and Anka, 2005; Anka et al., 2013).

The transitional stage (Aptian to Albian) was marked by the complete separation of the South Atlantic passive margin and the initial formation of the Lower Congo Basin. During this phase, thick salt deposits accumulated in a thermally subsiding shallow-water environment, covering the underlying rift basins (Séranne and Anka, 2005; Anka et al., 2013). The passive margin stage (Albian to present) began with the continued spreading of oceanic crust, leading to the establishment of a shallow marine environment. During the Albian, a massive carbonate sequence and coastal sand deposits were formed. As the oceanic crust cooled, significant subsidence occurred, accompanied by global sea-level rise. This resulted in widespread marine transgression, which temporarily ended during the Cenomanian, leading to the deposition of deep-water mudstones (Anderson et al., 2000; Anka et al., 2013; Warsitzka et al., 2017; Séranne and Anka, 2005). Occasional turbidity currents deposited sandstone layers in localized areas (Figure 2). The post-salt structural styles in the Late Cretaceous to Cenozoic sediments of the Lower Congo Basin are controlled by the interplay between salt tectonic activity and sedimentation rates (Monnier et al., 2014; Fort et al., 2004).

FIGURE 2

Comprehensive stratigraphic column and tectonic activity, sedimentation rate, and sea-level change diagram of the Lower Congo Basin (adapted from Séranne and Anka, 2005; Anka et al., 2013).

The structural characteristics of the central Lower Congo Basin are illustrated by seismic profile A (location in Figure 1). The salt layer, which acts as a regional detachment, thins toward the landward side of the Angolan passive margin. The extensional zone is dominated by salt rollers, with salt-related structures such as salt rafts and salt welds, but lacks significant diapirism. The transitional zone is less distinct, while the contractional zone features high-amplitude salt stocks, with no large-scale salt canopies or thrust faults observed (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Seismic interpretation profile of the central Lower Congo Basin (modified from Marton et al., 2000). The unlabeled unit represents the pre-salt basement.

3 Methods

3.1 Analog modeling approach and design

The experimental design is directly informed by seismic interpretation of the central Lower Congo Basin (Figure 1), which reveals prominent salt stocks in the absence of large-scale thrust faults. This structural framework guided the model geometry and boundary conditions. The experiment follows established geometric and dynamic similarity principles, employing well-justified rheological analogs (Hubbert, 1937; Allen and Beaumont, 2012; Weijermars et al., 1993; Adam et al., 2012). Brittle upper-crustal behavior is reproduced using high-purity (>98%) dry quartz sand with a bulk density of 1,300–1,600 kg/m3, grain sizes of 150–300 μm (median 199 μm), and frictional–plastic properties consistent with the Mohr–Coulomb criterion (Xie et al., 2013). The salt layer is modeled with a high-viscosity polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) polymer, which behaves as a Newtonian fluid with a density of 926 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 1.1 × 103 Pa·s under experimental strain rates. The scaling parameters are shown in Table 1. These parameters and material properties have been rigorously supported against natural prototypes, ensuring dynamic similarity in stress trajectories and power dissipation between the model and the natural system (Zhang et al., 2020; Santolaria et al., 2021).

TABLE 1

| Parameter | Model | Nature | Scaling ratio | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (L) | 1 cm | 4 km | 0.25 × 10–5 | |

| Density (ρ) | ||||

| Sand | 1,450 kg/m3 | 2,600 kg/m3 | 0.55 | |

| Polymer | 926 kg/m3 | 2,200 kg/m3 | 0.42 | |

| Gravity (g) | 9.8 m/s2 | 9.8 m/s2 | 1 | |

| Cohesion | 55 Pa | 50 × 106 Pa | 1.1 × 10–5 | |

| Deviatoric stress (σ) | 142 Pa | 1.02 × 108 Pa | 1.39 × 10–6 | σ = ρ⋅g⋅L |

| Ductile layer viscosity (η) | 1.1 × 103 Pa s | 1018 Pa⋅s | 1.1 × 10−15 Pa s | |

| Strain rate (ε) | 1.26 × 109 | ε = σ/η | ||

| Time (t) | 1 h | 13 My | 7.73 × 10−8 | t = 1/ε |

| Velocity (V) | 0.1 cm/h | 2.78 mm/y | 3.15 × 103 | V = L·ε |

Material properties and dynamic scaling parameters.

While the general approach follows earlier sandbox experiments on gravity-driven salt tectonics in the Kwanza Basin (Zhang et al., 2020), all boundary conditions in this study—such as basement morphology, salt thickness, slope geometry and time–thickness depositional schedules—were independently derived from the central Lower Congo dataset to ensure basin-specific similarity. The analog model configuration simplifies the structural geometry of the central Lower Congo Basin into a single-slope system, with dimensions of 65 cm (length) × 30 cm (width). To simulate the outer high volcanic basement obstruction, a 1 cm-thick foam barrier was positioned 15 cm from the distal (seaward) end of the model (Figure 4a). An initial 45 cm-long PDMS salt analog layer (thickness: 1 cm) was deposited on a pre-designed basement and allowed to equilibrate for 12 h (Figure 4b). Pre-kinematic sedimentation representing Albian–Cenomanian equivalent strata was then deposited using differentially colored sand layers (Figure 4c). Subsequently, a motor-driven tilting mechanism gradually elevated the proximal (landward) end by approximately 3°, replicating thermally driven subsidence and passive margin seaward dipping (Figure 4d).

FIGURE 4

(a) Spatial setting of analog modeling in the initial state, including the base plate, glass wall on both sides (the partition adjacent to the observation side is omitted in the diagram), as well as the arrangement of the outer high and buttress. (b) Paving the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) polymer and allowing the PDMS layer to stand and level out naturally. (c) Paving the pre-kinematic layer and removing the buttress. (d) Lifting the base plate while paving the syn-kinematic layer.

Syn-kinematic sedimentation was simulated by sieving equal-thickness sand layers (dyed for visualization) at fixed time intervals corresponding to geological periods (Table 2), thereby capturing sediment deposition during active deformation. Structural evolution was monitored via overhead time-lapse photography to document planform development. Post-experiment stabilization through water saturation enabled detailed cross-sectional analysis via serial slicing perpendicular to the structural trend.

TABLE 2

| Sedimentary | Age (Ma) | Model time (h) | Model thickness (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albian–Cenomanian | 113–93.9 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Turonian–Paleogene | 93.9–23.03 | 5.6 | 0.4 |

| Miocene | 23.03–5.333 | 1.4 | 1 |

| Pliocene | 5.333–2.58 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Quaternary | 2.58–0 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

Model parameters for the experimental process.

3.2 3D discrete element modeling approach and design

The physical modeling approach used in this study offers qualitative insights into the deformation processes within salt layers, but it suffers from certain limitations. Due to equipment constraints, it is not possible to directly observe the evolution of the salt basement interface, and the top surface topography and strain rate data were not obtainable during the experiments. As a result, the physical modeling results tend to focus on qualitative interpretations, which is why the original intention of conducting three-dimensional discrete element simulations is to compensate for the limitations of physical models in characterizing the developmental features of small basins at the basement interface and to improve the overall understanding of the research object through numerical simulation methods.

Compared to physical modeling, numerical simulations provide access to a wealth of dynamic information, are more flexible in terms of material parameters and boundary conditions, and offer more reproducible results. For example, physical modeling experiments face challenges in ensuring the evenness and thickness of sand layers and controlling environmental factors like temperature. Additionally, the materials available for analogous modeling in the laboratory are limited, whereas numerical simulations do not face such constraints. Numerical methods not only allow for detailed analysis of salt tectonic deformation processes but also are actively used to design targeted numerical experiments that probe the underlying mechanical mechanisms. For example, the Finite Element Method (FEM) and Finite Difference Method (FDM) are based on continuum mechanics. They can directly solve the Navier-Stokes equations or viscoelastic constitutive equations, and have irreplaceable advantages in efficiently handling the overall rheological behavior of high-viscosity continuous media such as salt rock and obtaining macro stress-strain fields. Thus, they are widely used in the simulation of high-viscosity geological bodies (Nikolinakou et al., 2012; Vengrovitch and Stovba, 2019).

The Discrete Element Method (DEM) is a numerical simulation technique that relies on contact rules between discrete particles (Cundall and Strack, 1979). The DEM uses a time-displacement finite difference method to calculate particle movement based on Newton’s laws. This method is advantageous because the rocks in the simulation are composed of particles that are bonded together, with no constraints on the relative displacement between particles. This allows for easy analysis of large strain structural deformation styles and has been widely used to simulate shallow crustal structures, fault systems, and shear zone deformation processes (Morgan and McGovern, 2005; Morgan, 2015; Dean et al., 2015). In recent years, it has also been applied to simulate salt tectonics (Carter et al., 1993; Morgan, 2004a; b).

Building on previous studies of passive continental margin basins in the South Atlantic, the underground salt layers are approximated as a Newtonian fluid, and the adopted model for salt is a linear model. The overlying layers of sedimentary rock are modeled using the commonly used parallel bond model, where particles are bonded in parallel, allowing them to transmit both force and torque. At the boundary between the salt particles and the overlying sediment layers, the parallel bond model is also applied. The normal and tangential stiffness of the walls in the simulation are set to 1010 N/m, with friction coefficients of 0.5 between the walls and particles, 0.1 for the salt layer, and 0.3 for the overlying sediments (Dean et al., 2015; Nikolinakou et al., 2012).

Given that salt tectonics evolve over geological time scales (millions of years), it is essential to incorporate accurate viscosity parameters for salt in numerical simulations. Salt behaves as a viscous fluid over geological time scales (Carter et al., 1993). In DEM simulations, the viscosity of the salt must be set appropriately to ensure accurate results. According to Newton’s law of viscosity, viscosity is the linear relationship between shear stress and velocity gradient. In natural conditions, the viscosity of salt is approximately 1017–1018 Pa·s. If set to these values in the DEM model, the simulation time would need to span several years to achieve geological time scale results. Therefore, for practical simulation purposes, the viscosity of salt in the DEM model is set to 108 Pa·s, with the velocity gradient adjusted to 1010 s-1 to ensure that the shear stress in the model matches that of natural conditions. The primary cause of salt deformation is the internal shear deformation of the salt (Morgan, 2004a), and this balance is maintained by adjusting the average sedimentation rate of subsequent continental deposits. These parameter settings are tailored to the analysis of salt tectonics, supporting the accuracy of the research findings (Maxwell, 2009; Dean et al., 2015; Carter et al., 1993; Morgan, 2004a; b). Table 3 presents the specific particle-related parameters used in the model.

TABLE 3

| Parameter | Salt | Supra-salt | Boundary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 2,200 | 2,600 | - |

| Normal stiffness (N/m) | 1010 | 1010 | - |

| Tangential stiffness (N/m) | 1010 | 1010 | - |

| Frictional | 0.1 | 0.3 | Inheritable |

| Damp | 0.7 | 0.7 | Inheritable |

| Contact type | Linear | Parallel bond | Parallel bond |

| Normal critical damping ratio | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Parallel bond normal stiffness (N/m) | - | 108 | 106 |

| Parallel bond shear stiffness (N/m) | - | 5 × 107 | 5 × 106 |

| Parallel bond tensile strength(N) | - | 2 × 105 | 2 × 103 |

| Parallel bond Cohesion(N) | - | 5 × 104 | 5 × 102 |

Microscopic parameters of particles in the 3D Discrete Element model.

To investigate the influence of extensional forces on salt tectonics along the principal stress direction, a 3D extensional model was created. In DEM simulations, the smallest time unit is the timestep, which is directly related to the mass of the particles and inversely related to their stiffness (Bathe and Wilson, 1976; Potyondy, 2009). Once the density, size, and stiffness of the particles are defined, the total number of particles determines the computation time. A large number of particles increases computational time, whereas a small number of particles may fail to capture the full extent of structural deformation. Therefore, when selecting the model’s scale and particle number, a balance between computational time and model realism must be considered.

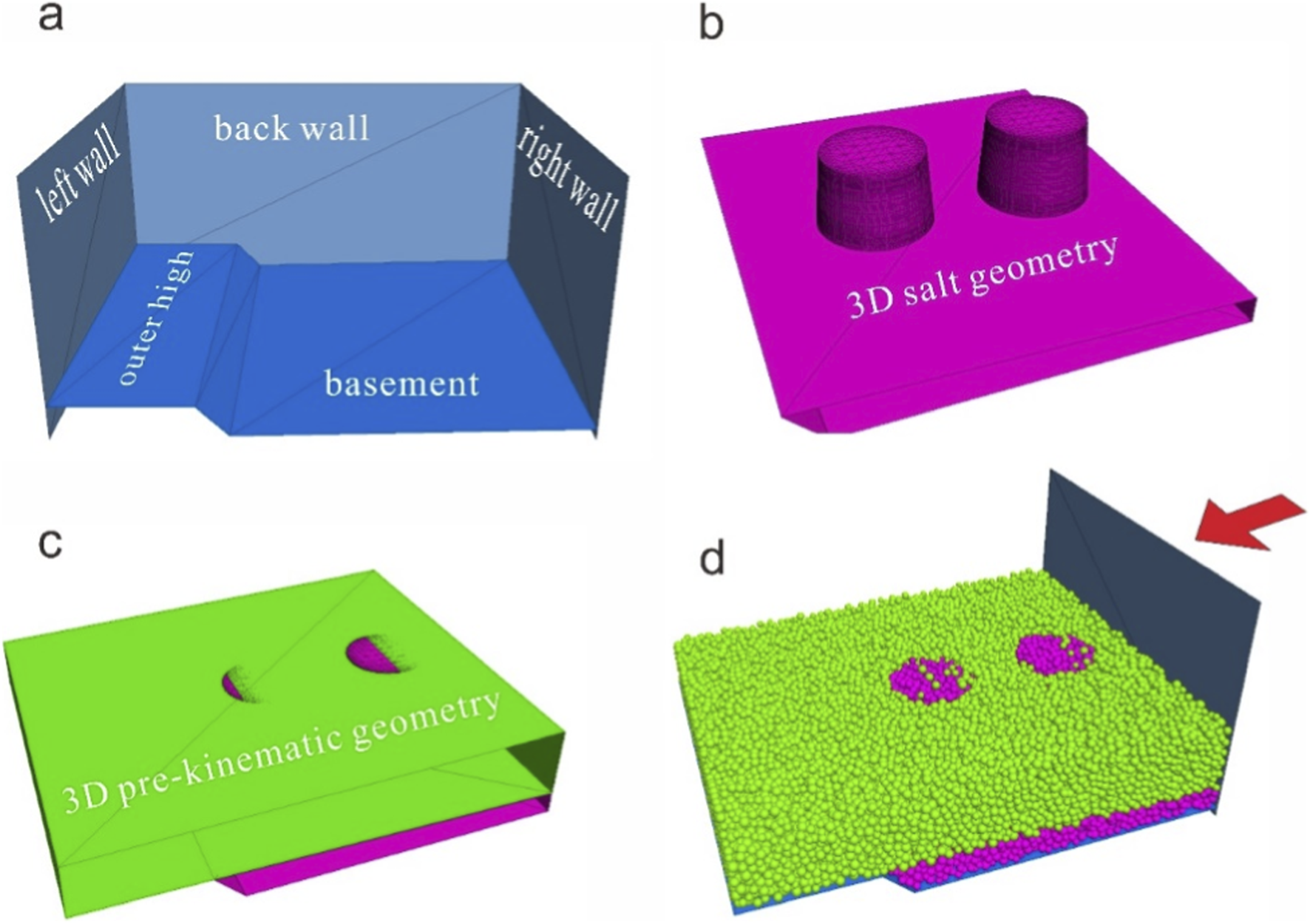

The simulation starts with a spatial domain of 250 m (x-axis), 250 m (y-axis), and 150 m (z-axis) (Figure 5a). Particles with radii ranging from 2 to 3 m are randomly generated within this domain. Gravity is then applied to allow the particles to naturally compact and reach equilibrium. Next, the top particles are gradually removed, leaving only particles within a 250 m × 250 m × 60 m area, resulting in a total of 31,798 particles. In contrast to the exploratory basin-scale DEM configuration used for the Kwanza Basin (Zhang et al., 2020), which did not include along-strike structural variability or pre-imposed diapirs, the present 3D DEM model explicitly incorporates two pre-existing salt diapirs and distinguishes salt, pre-kinematic and syn-kinematic strata as separate mechanical units in order to resolve local diapir–minibasin interactions in the central Lower Congo contractional domain (Figure 5b). The particles are assigned specific properties based on their geometry group (Figure 5c). The central layers of each depth interval are marked as reference layers to facilitate the identification of deformation patterns during later stages of the simulation. To simulate the deformation of the model, a rigid wall is placed on the right side, and the model is subjected to compression in the negative x-direction at a rate of 1 m/s (Figure 5d). During program operation, timesteps can be set to save the simulation results. However, it should be noted that “timesteps” only serve to characterize the relative chronological order of structural phenomena occurring in the process of simulation iteration and do not correspond to specific geological time. This is determined by the inherent nature of discrete element simulations—their timesteps are iterative units designed to ensure the convergence and stability of particle contact mechanics calculations, rather than being set to match real geological time. Although a correspondence between simulation time and geological time can be forcibly established through parameter adjustment, such calibration is generally not performed in similar discrete element simulation studies of salt structures. This is because the converted results are affected by various simplified parameters such as particle stiffness and friction coefficient, resulting in a lack of clear geological significance and comparability (Maxwell, 2009; Dean et al., 2015).

FIGURE 5

(a) Wall distribution of the 3D discrete element model (DEM) in the initial state, including the base wall, left and right walls, and front and back walls; the front wall is omitted in the diagram for ease of visualization. (b) Preset geometric morphology of the salt rock. (c) Geometric morphology of the pre-kinematic sedimentary layer. (d) Initial model morphology after balls generation, filling and equilibration.

4 Results

4.1 Analog modeling results

At the initial stage (15 min), the model began to develop a series of faults sequentially at the near-shore end (Figure 6a). After 1 h, the fault displacement gradually increased, leading to the formation of new faults at the near-shore end. At 2 h and 15 min, further expansion of the early faults resulted in the creation of additional faults at the near-land end. Meanwhile, the salt layer at the near-shore end began to make initial contact with the barrier (Figure 6b).

FIGURE 6

(a) Initial stage (15 min): sequential development of faults at the near-shore end. (b) 2 h 15 min: formation of new faults at the near-land end, with initial contact between the near-shore salt layer and the barrier. (c) 3 h: restricted stretching and compressional characteristics at the near-shore end; cessation of early fault displacement, and salt ascent along faults forming positive topographic anomalies in the overlying thin sedimentary layers. (d) 4 h: significant reduction in near-shore fault displacement; reverse faulting at the slope lowest point, with active salt domes persisting along the slope. (e) 6 h 30 min to 8 h 5 min: waning fault activity at both model ends; transition of linear salt basement deformation at the near-shore end to localized point deformation driven by differential lateral activity.

After 3 h, the stretching space at the near-shore end became restricted, displaying compressional characteristics. The displacement along the early faults ceased to increase, and salt began to ascend along these faults, creating a positive topographic anomaly at the surface of the overlying thinner sedimentary layers (Figure 6c). After 4 h, the fault displacement at the near-shore end showed a significant reduction compared to earlier stages, and a reverse faulting characteristic was observed at the lowest point of the slope, with active salt domes still present along the slope (Figure 6d).

From 6 h to 30 min to 8 h and 5 min, the activity along the faults at both ends of the model began to decline (Figure 6e). The linear salt basement deformation at the near-shore end formed a localized point deformation due to differential lateral activity. Observations from the typical profiles revealed significant variations in the maturity of the salt basement deformation, particularly at the near-shore end, where salt extrusion features were observed at the end, and salt welding occurred due to compressional stress, leading to the formation of salt tears. From the sea to the land, the intensity of the compressional deformation diminished. Notably, no turtle-back structures were observed between the basement deformations. A comparison with the actual geological profile indicates that the size and duration of salt domes at the near-land end closely resembled real-world conditions, while the salt basement deformation at the near-shore end was fully compressed (Figure 7). Regarding the activity duration of salt domes and basement deformations, the timescales of activity were distinctly hierarchical. Furthermore, there were significant variations in the activity durations of different types of deformations and salt domes. Specifically, extensional faults were active from 15 min to 4 h, compressional deformations from 3 h to 8 h 5 min. Slope salts were active in 1–4 h, near-shore linear salt structures from 3 h to 8 h 5 min, and localized salt domes from 6 h 30 min onward.

FIGURE 7

Photos and explanations of the cross-sectional results of the physical simulation experiment.

4.2 3D discrete element modeling results

4.2.1 Structural evolution of the salt layer top surface and cross-sectional profiles

Under progressive compression, the model exhibits a clear stage-wise evolution in the coupled deformation of salt structures and sedimentary layers, transitioning from initial local thickening of salt and strata uplift, through pronounced diapir rise and minibasin development, to the formation of thrust-dominated salt sheets and their eventual burial beneath syn-kinematic deposits (Figure 8). Initial compressional stresses localized near the contractional boundary, inducing upward tilting of originally horizontal strata adjacent to pre-existing diapirs while causing marked thinning of subsequent sedimentary layers over diapir crests (∼100,000 timesteps). Concurrently, salt diapirs displayed enhanced vertical migration with crestal widening, particularly pronounced near the contractional boundary. Early-stage salt inflation was evidenced by preferential upward mobilization of horizontal salt layers in the lower-left quadrant. As compression propagated to distal diapirs (∼200,000 timesteps), basement-driven strain partitioning initiated fold-dominated deformation in both pre-kinematic and syn-kinematic sedimentary layers, accompanied by incipient thrust development above basement obstacles. Minibasins emerged between diapirs with pronounced syn-kinematic sediment thickening. While both diapirs underwent crestal widening, proximal diapirs maintained stronger vertical ascent. Salt advance continued upslope, partially overriding the basal detachment. Progressive compression (∼300,000 timesteps) amplified minibasin development, which was manifested by the expansion of minibasin spatial scale (i.e., increased area and depth of the negative topography between diapirs) and significant thickening of sediments in the depocenters. Salt diapirs absorbed substantial strain, elongating perpendicular to the maximum principal stress (σ1) and shortening parallel to it, forming elliptical geometries with long axes orthogonal to σ1. Complete overriding of the detachment surface in the lower-left quadrant generated thrust-dominated salt sheets. At advanced deformation stages (∼400,000 timesteps), syn-kinematic sediment thickness homogenized with cessation of minibasin thickening. Pre-existing diapirs became fully buried by syn-kinematic deposits, which depended on the relative rate between diapir growth rate and sedimentation rate. Throughout the compression history, coupled evolution of diapiric deformation and sedimentary layers demonstrated a persistent feedback between salt mobility and sediment loading.

FIGURE 8

Salt diapir structures and cross-sectional profiles parallel to the maximum principal stress direction (Y = 125).

4.2.2 Velocity analysis along the maximum principal stress direction

Progressive strain accumulation drives kinematic convergence from initially decoupled diapir-sediment systems toward homogenized oblique uplift, with stress shadows delineating persistent mechanical heterogeneities (Figure 9). Initial compression (∼100,000 timesteps) generated marked velocity anomalies at both diapirs with pronounced vertical mobilization. The proximal diapir exhibited uplift vectors combining vertical and compression-parallel lateral components, kinematically coupled with supra-salt sediment motion. Conversely, the distal diapir maintained predominantly vertical ascent trajectories, displaying mechanical decoupling from adjacent sediments. As strain accumulated (∼200,000 timesteps), diapir-sediment kinematic coupling intensified, reducing displacement contrasts between structures and host strata. The proximal diapir transitioned to horizontal translation aligned with the compression axis, while the distal diapir sustained vigorous vertical rise in its mid-upper sections. Sedimentary packages between diapirs and along the distal diapir’s left flank developed persistent low-displacement zones, delineating well-defined stress shadows. During advanced compression (∼300,000–400,000 timesteps), displacement patterns stabilized with both diapirs converging toward obliquely vertical uplift skewed 15°–20° toward the compression direction. Stress-shadow zones remained active in inter-diapir regions and along the distal diapir flank. Progressive strain homogenization culminated in near-complete elimination of kinematic disparities between diapirs and sedimentary layers by ∼400,000 timesteps.

FIGURE 9

Velocity distribution along the maximum principal stress direction (Y = 125).

4.2.3 Vertical cross-section evolution perpendicular to the maximum principal stress direction

Integrated 3D DEM simulations document a systematic salt geometric progression from cylindrical inflation to teardrop welding, while exposing critical limitations of 2D section analysis in capturing salt mobility vectors (Figure 10). Initial deformation manifested as localized salt inflation, forming incipient cylindrical diapirs with subtle crestal topography while supra-salt sediments retained near-original geometry (∼100,000 timesteps). During intermediate compression, the diapir pierced the first syn-kinematic layer and induced pronounced thinning of the overlying second layer, evolving into a mushroom morphology with a narrowed neck and expanded crest (∼200,000 timesteps). Progressive salt upwelling under intensified compression drove significant tilting of flanking sediments as crestal widening accelerated (∼300,000 timesteps), resulting in the further inclination of flank strata toward the diapir. At maturation, pre-kinematic strata underwent steep tilting concurrent with diapir neck welding, generating salt teardrop structures while syn-kinematic sediments tapered toward the diapir crest (∼400,000 timesteps). Crucially, 2D sectional analysis underestimates three-dimensional dynamics by failing to capture out-of-plane salt migration, leading to overestimation of strain localization within the profile plane, underscoring the necessity of integrated 3D approaches to resolve out-of-plane flow and stress anisotropy (Marton et al., 2000; Vendeville and Jackson, 1992).

FIGURE 10

Cross-sectional profiles perpendicular to the maximum principal stress direction (X = 130). Salt bodies migrate vertically through this plane over time.

4.2.4 Dynamic evolution of 3D salt mobility and displacement vectors

The dynamic evolution of salt structures under continued compression reveals a progressive shift from localized velocity anomalies to basin-wide mechanical coupling (Figure 11). Initial velocity gradients decreased basinward from the contractional boundary, with high-velocity zones (HVZs) localized at diapirs during vertical upwelling and low-velocity anomalies (LVZs) developing downdip of the proximal diapir (∼100,000 timesteps). The proximal diapir exhibited compression-skewed uplift while the distal diapir maintained weaker vertical motion. Progressive strain partitioning intensified lateral velocity contrasts, contracting the distal LVZ toward its central axis as the proximal diapir transitioned to horizontal translation and the distal structure sustained vertical ascent (∼200,000 timesteps). Velocity gradient diminution occurred at intermediate stages, with distal LVZ contraction to a basal narrow zone and both diapirs aligning toward regional compression despite retained vertical components in the distal structure (∼300,000 timesteps). Final-stage homogenization eliminated lateral velocity gradients and distal LVZs, with parallel-to-compression motion of both diapirs confirming full mechanical integration into the regional stress field (∼400,000 timesteps).

FIGURE 11

Velocity distribution on the salt layer top surface.

4.2.5 3D velocity structure evolution under syn-depositional compression

The evolution of salt structures with two adjacent pre-existing diapirs under syn-depositional compression demonstrates a general resemblance to 2D sectional behavior while revealing significant lateral heterogeneity in three dimensions. Vertical velocity structures are analyzed across upper, middle, and lower layers (Figure 12). At the early stage (∼100,000 timesteps), a velocity gradient decreasing from the contractional boundary toward the basin interior dominates the model, with pronounced high-velocity anomalies (HVAs) centered over both pre-existing diapirs. In the middle and lower layers, distinct low-velocity anomalies (LVAs) develop downdip of the diapirs along the compression direction, exhibiting similar geometries. By ∼200,000 timesteps, velocity contrasts between the proximal diapir and its host sediments diminish in the upper layer, while HVAs persist in the middle and lower layers. The downdip LVA adjacent to the proximal diapir vanishes, while a fan-shaped LVA emerges downdip of the distal diapir. As deformation advances (∼300,000 timesteps), velocity contrasts further decrease in the upper layer, and downdip LVAs disappear completely. In the middle and lower layers, the fan-shaped LVA contracts toward the central axis of the distal diapir. By the final stage (∼400,000 timesteps), velocity structures homogenize across all layers, with minimal contrast between diapirs and surrounding sediments. The disappearance of both downdip LVAs indicates full mechanical coupling of the diapirs into the regional stress regime.

FIGURE 12

Velocity structure (cross-sectional slices at Z = 30, Z = 40, and Z = 50 from top to bottom).

5 Discussion

5.1 Comparison with natural profiles: The genetic mechanism of high-amplitude mushroom-shaped salt diapirs in the proximal contractional zone

Early analog modeling of the Angolan passive margin demonstrated that lithospheric cooling during the late drifting phase induces a basinward tilting of the passive margin, thereby initiating gravitational instability within the salt layer and its overburden. This process drives large-scale downslope movement, resulting in coeval extensional deformation in the upper slope and contractional deformation in the lower slope (Duval et al., 1992; Fort et al., 2004). Within the conventional three-zone framework, salt-tectonic provinces on passive margins are typically divided from landward to seaward into extensional, transitional, and contractional zones. In most physical models of passive-margin salt systems, including those calibrated to the Kwanza Basin, the extensional zone is dominated by growth faults and salt rafts, while the contractional zone expressed by thrust faults and compressional salt structures such as canopies and nappes rather than by numerous high-relief diapirs (Zhang et al., 2020). Positioned between these two is the transitional zone, characterized by an ambiguous stress regime and the frequent occurrence of high-amplitude salt diapirs. Comparable structural patterns have been documented in the Lower Congo Basin (Cramez and Jackson, 2000).

A central issue in this structural configuration is the spatial compatibility between upper-slope extension and lower-slope contraction. Some studies propose that extension in the upper slope should be balanced by shortening in the lower slope (Duval et al., 1992; Fort et al., 2004). However, this balance is challenged by the magnitude of displacement observed in upper-slope salt rafts, which often exceeds the amount of shortening accommodated by folding and thrusting in the lower slope. Observations suggest that the extension of proximal salt rafts and the contractional deformation of distal salt structures occur simultaneously, with distal shortening creating the space needed for extreme extension in the proximal domain (Adam et al., 2012; Pilcher et al., 2014). Nonetheless, in the most extended raft systems of the Lower Congo Basin, Albian salt rafts record cumulative downslope translations of up to ∼200 km—far exceeding the accommodation space provided solely by lower-slope shortening (Pilcher et al., 2014; Rouby et al., 2003).

Alternative explanations for this space discrepancy include oceanic spreading as a potential sink for upper-slope extension (Duval et al., 1992). However, the lateral extent of salt overlying the oceanic crust is often limited, and in some cases, salt does not extend onto the oceanic domain at all. Consequently, the accommodation space produced by oceanic crust accretion is not fully utilized by salt systems (Kukla et al., 2018). For the Angolan margin, seismic interpretations and stratigraphic evidence have also supported models involving basement tilting on both landward and oceanward sides (Jackson et al., 2000). Yet, due to the structural complexity of the contractional domain and the generally poor quality of seismic imaging in this region, the spatiotemporal relationship between upper-slope extension and lower-slope contraction remains poorly constrained.

In examining contractional salt structures, gravity-driven fold belts on passive margins have been classified into thrusts, folds, squeezed diapirs, and salt nappes—largely influenced by the initial thickness of the source salt layer (Rowan et al., 2004). Among these, squeezed diapirs are typically interpreted as pre-existing diapirs that later experienced compression. However, in most physical experiments, the lower slope rarely exhibits abundant high-amplitude salt diapirs, suggesting that factors beyond source layer thickness—such as boundary conditions, sedimentation rates, or timing of slope toe obstruction—may play critical roles in diapir evolution.

Recent insights further underscore the significance of temporal dynamics. For instance, continuous extension over 3–4 million years following salt deposition may have facilitated emplacement of intrusive oceanic crust beneath the salt layer, followed by volcanic activity that later obstructed seaward salt flow. This obstruction near the slope toe, in some cases, appears to be volcanically induced rather than a persistent compressional boundary from the outset (Norton et al., 2016). Finite element modeling suggests that wide salt basins like the Lower Congo Basin, formed during the final rifting stages before continental breakup, may develop distal salt sheets over newly accreted oceanic crust (Pichel et al., 2022). In such systems, a phase of free gravitational spreading likely preceded later-stage obstruction by volcanic outer highs.

Building on these concepts and incorporating seismic observations, a new experimental design was developed to simulate delayed obstruction at the slope toe. This setup aims to investigate its effects on the formation and evolution of salt diapirs and to explore the spatial and temporal differentiation between gravity spreading and gravity gliding during salt raft extension and diapirism.

Comparison between the central Lower Congo Basin’s actual geological profiles and physical modeling experiments shows a high degree of similarity with seismic profiles (Figure 13). Integrating previous studies, it can be inferred that the salt in the proximal contractional zone experienced a brief phase of free gravitational spreading before being obstructed by later volcanic basement highs. Subsequent gravity-driven sliding from the proximal extensional zone transmitted compressional stresses, forming contractional salt diapirs rather than sustaining a continuously compressional environment from the outset. Based on the physical modeling results, the salt tectonics in the central Lower Congo Basin underwent three evolutionary stages at the passive margin scale: a) Global Extension Phase: Regional extension of both the salt layer and overburden; b) Frontal Obstruction Phase: Termination of seaward extension due to volcanic basement highs; c) Compression Propagation Phase: Landward propagation of compressional stresses (Figure 14). Minibasin research is presented in Section 5.2 via DEM simulations.

FIGURE 13

Comparison of the seismic profile of the central Lower Congo Basin with the analog modeling results. The analog modeling results are derived from Figure 7, and the seismic profile is from Figure 3. They are juxtaposed here to intuitively compare the structural morphology and evolutionary characteristics between the analog modeling and actual seismic observation.

FIGURE 14

(a) Global Extension stage: Gravitational spreading dominates the salt layer and overburden. Extensional initial faults on the upper slope evolve into pre-salt rafts and salt rafts (with structural styles controlled by the interplay between raft slip rates and syn-kinematic sedimentation rates), while extensional faults on the mid-lower slope induce passive salt diapirs due to insufficient overburden thinning. (b) Frontal Obstruction stage: Obstruction limits salt and overburden mobility, establishing a proximal-distal mechanical linkage. Passive diapirs in the transitional zone show sedimentation rate-controlled growth; post-salt weld formation, overburden tilting toward diapirs forms turtle structures, and persistent extension leads to pseudo-turtle structures atop collapsed diapirs. (c) Compression Propagation stage: Stress inversion transforms lower-slope pre-existing diapirs into a compressional regime, evolving into mushroom-shaped geometries. Landward-propagating intense compression induces mid-diapir welding (forming salt teardrops), with inter-diapir sedimentary architectures governed by adjacent diapir activity intensity.

During Global Extension stage, gravitational spreading dominates both the salt layer and overburden. Under the control of a tilted basement, initial fractures develop at various positions along the profile. On the upper slope, extensional initial fractures form grabens, which gradually evolve into pre-salt rafts (incompletely detached fault blocks with unwelded salt rollers) and salt rafts (Duval et al., 1992; Pilcher et al., 2014; Piedade and Alves, 2017). The dip angle of the salt detachment surface governs the slip rate of salt rafts, while syn-kinematic sedimentation rates control the infill patterns between rafts. The interplay between raft slip rates and sedimentation rates determines the structural styles of rafts and inter-raft deposits (Cheng et al., 2020). Relatively high sedimentation rates favor domino-style pre-salt rafts and salt rafts, whereas lower rates promote horst-and-graben-style salt rafts. Once salt welds form, the sliding capacity of the overburden is significantly reduced. On the mid-lower slope, extensional fractures cause insufficient overburden thinning to resist salt upwelling, resulting in passive salt diapirs (Figure 14a).

Frontal Obstruction stage marks a critical temporal transition. The formation of obstructions limits the mobility of salt and overburden, establishing a mechanical linkage between proximal extension and distal contraction. During the initial obstruction period, compressional effects remain localized. In the transitional zone, passive diapirs exhibit growth morphologies strongly controlled by sedimentation rates. Inter-diapir structures are influenced by salt weld formation. Post-weld development, continued salt withdrawal from diapir flanks tilts the overburden toward diapirs, forming turtle structures. If extension persists, salt evacuation and diapir collapse generate pseudo-turtle structures atop pre-existing diapirs (Figure 14b). Following obstruction formation, pre-existing diapirs in the lower slope experience stress inversion, transitioning to a compressional regime. These diapirs undergo necking and evolve into mushroom-shaped geometries. Compression propagates landward, with the strongest and longest-lasting effects near the contractional boundary. Intense compression induces mid-diapir welding, forming salt teardrops. The structural architecture of inter-diapir sediments is governed by the activity intensity of adjacent diapirs (Figure 14c).

5.2 Interactions between salt diapirs and their impact on syn-depositional strata

3D discrete element simulations reveal that depocenter migration in minibasins is dynamically linked to along-strike variations in the growth rates of adjacent diapirs (Figure 15a). When the salt supply is sufficient and syn-depositional compression does not induce neck welding of pre-existing diapirs, the seaward Diapir 1 initially dominates activity, attracting the depocenter toward its vicinity. As Diapir 2 becomes more active, the depocenter shifts toward Diapir 2 Salt feeding into the diapirs originates from adjacent source layers, and the resultant salt withdrawal causes subsidence of the overlying strata, consistent with the conceptual framework proposed by Brun and Fort (2011). Similar patterns of depocenter focusing and subsequent lateral shifting toward more active or longer-lived diapirs have been documented in natural salt minibasins from the Lower Congo Basin and Santos Basin, where depocenters migrate in response to diachronous welding and spatial gradients in diapir activity (Ge et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2021; Diório et al., 2025). These observational studies show that depocenters tend to remain broadly centred between diapirs of comparable growth history, but progressively shift toward diapirs that accommodate a greater fraction of salt flow and vertical displacement.

FIGURE 15

(a) Simulation results: Minibasin depocenter migration correlates with adjacent diapir growth rate variations. With sufficient salt supply and no diapir neck welding, Diapir 1 initially dominates (depocenter attracted), followed by Diapir 2 (depocenter shift). Salt withdrawal from source layers induces overlying strata subsidence (Brun and Fort, 2011). (b) Seismic comparisons (central Lower Congo Basin): Left – Diapir 1/2 have comparable activity (equal strata pierced), depocenter centered. Right – Depocenter migrates toward Diapir 2 (Diapir 3 weaker, fewer strata pierced).

A comparison with seismic profiles from the central Lower Congo Basin supports this model-based behaviour (Figure 15b). Between Diapir 1 and Diapir 2, both diapirs pierce an equal number of strata with similar contact relationships, suggesting comparable activity intensities. In this case, the minibasin depocenter remains located approximately midway between the two diapirs, as expected for a system where salt withdrawal and subsidence are symmetrically partitioned. In contrast, the minibasin between Diapir 2 and Diapir 3 exhibits sustained depocenter migration toward Diapir 2, indicating weaker activity of Diapir 3. This is corroborated by the greater number of strata pierced by Diapir 2 compared to Diapir 3. The observed asymmetric depocenter migration in the central Lower Congo Basin is therefore consistent with the along-strike activity gradients inferred in other passive-margin salt provinces, where more active or later-welding diapirs act as long-term sediment traps and drive lateral shifts of the minibasin depocenter (Ge et al., 2020; Diório et al., 2025).

The weak mechanical strength and high ductility of salt enable diapirs to act as strain sinks, preferentially absorbing deformation in regions with pre-existing diapirs. Our 3D discrete element simulations of two adjacent pre-existing diapirs under syn-depositional compression demonstrate that compressional strain is first absorbed by the proximal (seaward) diapir, generating a fan-shaped low-strain anomaly downdip. Strain absorption intensifies with depth, weakening near the surface (Figure 16). Once the proximal diapir approaches strain saturation, the distal (landward) diapir continues to accommodate deformation until both are saturated.

FIGURE 16

3D diagram of salt rock flow in diapirs and stress absorption between diapirs under compression.

Seismic profiles from the central Lower Congo Basin (Figure 15b) validate this mechanism: proximal diapirs exhibit greater necking and strain absorption, with diminishing effects toward distal diapirs. This along-strike gradient in diapir activity provides a robust explanation for the observed minibasin depocenter migration, which tracks the locus of maximum diapiric strain accommodation. This behaviour provides a three-dimensional mechanical underpinning for the strain-partitioning scenarios inferred from analogue and numerical models of gravity-driven and contractional salt systems, which show that minibasins and diapirs compete for salt and strain through time (Ge et al., 2019; Zwaan et al., 2021; Santolaria et al., 2021; Fernandez et al., 2023; Gou and Liu, 2024; Wang et al., 2017). In these studies, subsidence minima and depocenters tend to migrate toward regions where salt withdrawal and strain localization are maximized, broadly mirroring the patterns observed in our DEM experiments.

In contrast to most previous 2D analogue and numerical studies that infer depocenter migration from evolving subsidence patterns (Zwaan et al., 2021; Fernandez et al., 2023) or from coupled analogue–flow simulations (Wang et al., 2017), our fully 3D discrete element models explicitly resolve the competition for strain between neighbouring diapirs and its direct impact on depocenter trajectories. The resulting “stress-release window” at pre-existing diapirs highlights their critical role in modulating three-dimensional strain distribution and depocenter evolution, providing critical insights for interpreting salt-related hydrocarbon traps and reservoir fairways in contractional salt provinces.

6 Conclusion

This study integrates physical analog experiments with 3D discrete element modeling to unravel the deformation mechanisms and spatiotemporal evolution of Aptian salt structures in the central Lower Congo Basin. The results support a three-phase evolutionary model for passive margin salt tectonics: Global Extension Phase–Characterized by seaward gravitational spreading of the salt layer and overburden, producing salt rafts and passive diapirs under basement tilt; Frontal Obstruction Phase–Initiated by volcanic basement highs that block seaward salt flow, leading to stress accumulation and onset of contraction; Compression Propagation Phase–Involves landward migration of compressional stresses, formation of squeezed and welded diapirs with mushroom or teardrop geometries, and minibasin development. The study highlights that pre-existing diapirs act as preferential strain sinks, facilitating vertical and lateral salt migration. These structures create localized velocity anomalies and stress shadows, which control the distribution and migration of sedimentary depocenters. Diapirs exhibiting sustained vertical ascent attract sediment loading, further amplifying structural differentiation and promoting minibasin asymmetry. Comparison with seismic profiles demonstrates strong agreement between model outputs and natural observations, justifying the model’s ability to capture key salt tectonic features. The findings clarify the spatial imbalance between upper-slope extension and lower-slope contraction, attributing it to delayed obstruction timing and pre-existing diapir activity rather than synchronous shortening. This work contributes to the broader understanding of passive margin salt systems by emphasizing the importance of 3D dynamics, obstruction timing, and salt rheology. The results offer valuable guidance for hydrocarbon exploration in salt-bearing basins, particularly in predicting the location and evolution of structural traps associated with complex salt deformation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PC: Software, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. YQ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. JZ: Writing – review and editing, Visualization.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering Doctoral Scientific Research Staring Fund Project (BKY202133).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adam J. Ge Z. Sanchez M. (2012). Post-rift salt tectonic evolution and key control factors of the Jequitinhonha deepwater fold belt, central Brazil passive margin: insights from scaled physical experiments. Mar. Petroleum Geol.37, 70–100. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2012.06.008

2

Allen J. Beaumont C. (2012). Impact of inconsistent density scaling on physical analogue models of continental margin scale salt tectonics. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth117, B08. 10.1029/2012JB009227

3

Anderson J. E. Cartwright J. Drysdall S. J. Vivian N. (2000). Controls on turbidite sand deposition during gravity-driven extension of a passive margin: examples from Miocene sediments in Block 4, Angola. Mar. Petroleum Geol.17, 1165–1203. 10.1016/S0140-6701(02)85071-8

4

Anka Z. Ondrak R. Kowitz A. di Primio R. Horsfield B. (2013). Identification and numerical modelling of hydrocarbon leakage in the lower Congo Basin: implications on the genesis of km-wide seafloor mounded structures. Tectonophysics604, 153–170. 10.1016/j.tecto.2012.11.020

5

Bathe K. J. Wilson E. L. (1976). Numerical methods in finite element analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. 10.1002/nag.1610010308

6

Brun J. P. Fort X. (2011). Salt tectonics at passive margins: geology versus models. Mar. Petroleum Geol.28, 1123–1145. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2011.03.004

7

Carter N. L. Horseman S. T. Russell J. E. Handin J. (1993). Rheology of rock salt. J. Struct. Geol.15, 1257–1271. 10.1016/0191-8141(93)90168-A

8

Cheng P. Li J. Zhang Y. Wang D. Liu Z. (2020). Physical simulation of Cretaceous salt rafts in the lower Congo Basin. J. Univ. Geosciences26 (5), 585–591. 10.16108/j.issn1006-7493.2019067

9

Cramez C. Jackson M. P. A. (2000). Superposed deformation straddling the Continental-Oceanic transition in deep-water Angola. Mar. Petroleum Geol.17, 1095–1109. 10.1016/S0264-8172(00)00053-2

10

Cundall P. A. Strack O. D. L. (1979). “The development of constitutive laws for soil using the distinct element method,” in Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Numerical Methods in Geomechanics, Aachen, Germany, April 2-6, 1979, 289–317. 10.1002/nag.637

11

Dean S. Morgan J. Brandenburg J. P. (2015). Influence of mobile shale on thrust faults: insights from discrete element simulations. AAPG Bull.99, 403–432. 10.1016/j.jsg.2013.05.008

12

Diório G. R. Trzaskos B. Pichel L. M. Dias S. F. L. Assis V. da S. R. (2025). Stacking patterns in minibasins and intra-salt geometries as clues for reconstructing salt tectonic processes: the case of the Northern Santos Basin, Brazil. Mar. Petroleum Geol.174, 107328. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2025.107328

13

Dooley T. Jackson M. P. A. Hudec M. R. (2009). Inflation and deflation of deeply buried salt stocks during lateral shortening. J. Struct. Geol.31, 582–600. 10.1016/j.jsg.2009.03.013

14

Duval B. Cramez C. Jackson M. P. A. (1992). Raft tectonics in the Kwanza Basin, Angola. Mar. Petroleum Geol.9, 389–404. 10.5802/crgeos.103

15

Eslamirezaei N. Alavi S. A. Nabavi S. T. Mohammadi M. (2022). Understanding the role of décollement thickness on the evolution of décollement folds: insights from discrete element models. Comptes Rendus Géoscience354, 75–91. 10.5802/crgeos.103

16

Fernandez N. Duffy O. B. Jackson C. A.-L. Kaus B. J. P. Dooley T. Hudec M. (2023). How fast can minibasins translate down a slope? Observations from 2D numerical models. Tektonika1, 177–197. 10.55575/tektonika2023.1.2.22

17

Ferrer O. Gratacós O. Roca E. Muñoz J. A. (2017). Modeling the interaction between presalt seamounts and gravitational failure in salt-bearing passive margins: the Messinian case in the northwestern Mediterranean Basin. Interpretation5, SD99–SD117. 10.1190/INT-2016-0096.1

18

Ferrer O. Gratacós O. Roca E. Muñoz J. A. (2020). The influence of pre-salt topography on minibasin evolution: insights from 3D seismic data and numerical modeling, offshore Brazil. Mar. Petroleum Geol.122, 104628. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104628

19

Fort X. Brun J. P. Chauvel F. (2004). Salt tectonics on the Angolan margin, synsedimentary deformation processes. AAPG Bull.88, 1523–1544. 10.1306/06010403012

20

Ge Z. Rosenau M. Warsitzka M. Gawthorpe R. L. (2019). Overprinting translational domains in passive margin salt basins: insights from analogue modelling. Solid earth.10, 1283–1300. 10.5194/se-10-1283-2019

21

Ge Z. Gawthorpe R. L. Rotevatn A. Zijerveld L. Oluboyo A. P. (2020). Minibasin depocentre migration during diachronous salt welding, offshore Angola. Basin Res.32, 875–893. 10.1111/bre.12404

22

Ge Z. Gawthorpe R. L. Zijerveld L. Oluboyo A. P. (2021). Spatial and temporal variations in minibasin geometry and evolution in salt tectonic provinces: lower Congo Basin, offshore Angola. Basin Res.33, 594–611. 10.1111/bre.12486

23

Gou Y. Liu M. (2024). Active and passive salt diapirs: a numerical study. Geophys. J. Int.239, 621–636. 10.1093/gji/ggae284

24

Hubbert M. K. (1937). Theory of scale models as applied to the study of geologic structures. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull.48, 1459–1520. 10.1130/GSAB-48-1459

25

Hudec M. R. Jackson M. P. A. (2007). Terra infirma: understanding salt tectonics. Earth-Science Rev.82, 1–28. 10.1016/j.earscirev.2007.01.001

26

Jackson M. P. A. Hudec M. R. (2017). Salt tectonics: principles and practice. London, UK: Cambridge University Press, 76–77. 10.1017/9781139003988.005

27

Jackson M. P. A. Vendeville B. C. (1994). Regional extension as a geologic trigger for diapirism. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull.106, 57–73. 10.1130/0016-7606(1994)106<0057:reaagt>2.3.co;2

28

Jackson M. P. A. Cramez C. Fonck J. M. (2000). Role of subaerial volcanic rocks and mantle plumes in creation of South Atlantic margins: implications for salt tectonics and source rocks. Mar. Petroleum Geol.17, 477–498. 10.1016/S0264-8172(00)00006-4

29

Jackson M. P. A. Hudec M. R. Jennette D. C. Kilby R. E. (2008). Evolution of the Cretaceous Astrid thrust belt in the ultradeep-water Lower Congo Basin, Gabon. AAPG Bull.92, 487–511. 10.1306/12030707074

30

Jackson C. A. L. Jackson M. P. A. Hudec M. R. (2015). Understanding the kinematics of salt-bearing passive margins: a critical test of competing hypotheses for the origin of the Albian Gap, Santos Basin, offshore Brazil. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull.127, 1730–1751. 10.1130/B31290.1

31

Koyi H. (1998). The shaping of salt diapirs. J. Struct. Geol.20, 321–338. 10.1016/S0191-8141(97)00092-8

32

Koyi H. Ghasemi A. Hessami K. Dietl C. (2008). The mechanical relationship between strike-slip faults and salt diapirs in the Zagros fold-thrust belt. J. Geol. Soc.165, 1031–1044. 10.1144/0016-76492007-142

33

Kukla P. A. Strozyk F. Mohriak W. U. (2018). South Atlantic salt basins — witnesses of complex passive margin evolution. Gondwana Res.53, 41–57. 10.1016/j.gr.2017.03.012

34

Marton L. G. Tari G. C. Lehmann C. T. (2000). “Evolution of the Angolan passive margin, West Africa, with emphasis on postsalt structural styles,” in Atlantic rifts and Continental margins. American geophysical union). Editors MohriakW. U.TalwaniM. (Washington, DC, USA: Geophysical Monograph Series), 115, 129–149. 10.1029/gm115p0129

35

Maxwell S. A. (2009). Deformation styles of allochthonous salt sheets during differential loading conditions: insights from discrete element models. Houston, TX, USA: Rice University. PhD Thesis. 10.1144/SP476.13

36

Monnier D. Imbert P. Gay A. Lopez M. (2014). Pliocene sand injectites from a submarine lobe fringe during hydrocarbon migration and salt diapirism: a seismic example from the Lower Congo Basin. Geofluids14, 1–19. 10.1111/gfl.12057

37

Morgan J. K. (2004a). Particle dynamics simulations of rate- and state-dependent frictional sliding of granular fault gouge. Pure Appl. Geophys.161, 1877–1891. 10.1007/s00024-004-2537-y

38

Morgan J. K. (2004b). “Particle dynamics simulations of Rate- and state-dependent frictional sliding of granular fault gouge,” in Rheology and deformation of the lithosphere at Continental margins (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 1877–1891.

39

Morgan J. K. (2015). Effects of cohesion on the structural and mechanical evolution of fold and thrust belts and contractional wedges: discrete element simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth120, 3870–3896. 10.1002/2014JB011455

40

Morgan J. K. McGovern P. J. (2005). Discrete element simulations of gravitational volcanic deformation: deformation structures and geometries. J. Geophys. Res.110, B05. 10.1029/2004JB003252

41

Nikolinakou M. A. Luo G. Hudec M. R. Flemings P. B. (2012). Geomechanical modeling of stresses adjacent to salt bodies: part 2—Poroelastoplasticity and coupled overpressures. AAPG Bull.96, 65–85. 10.1306/04111110143

42

Norton I. O. Carruthers D. T. Hudec M. R. (2016). Rift to drift transition in the South Atlantic salt basins: a new flavor of oceanic crust. Geology44, 55–58. 10.1130/G37265.1

43

Pichel L. M. Finch E. Huuse M. Gawthorpe R. L. (2017). The influence of shortening and sedimentation on rejuvenation of salt diapirs: a new discrete-element modelling approach. J. Struct. Geol.104, 61–79. 10.1016/j.jsg.2017.09.016

44

Pichel L. M. Finch E. Gawthorpe R. L. (2019). The impact of pre-salt rift topography on salt tectonics: a discrete-element modeling approach. Tectonics38, 1466–1488. 10.1029/2018TC005174

45

Pichel L. M. Huismans R. S. Gawthorpe R. Muñoz J. A. Theunissen T. (2022). Coupling crustal-scale rift architecture with passive margin salt tectonics: a geodynamic modeling approach. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth127 (11), e2022JB025177. 10.1029/2022JB025177

46

Piedade A. Alves T. M. (2017). Structural styles of Albian rafts in the Espírito Santo basin (SE Brazil): evidence for late raft compartmentalisation on a ‘passive’ continental margin. Mar. Petroleum Geol.79, 201–221. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.10.023

47

Pilcher R. S. Murphy R. T. Ciosek M. D. (2014). Jurassic raft tectonics in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Interpretation2, SM39–SM55. 10.1190/INT-2014-0058.1

48

Potyondy D. (2009). Stiffness matrix at a contact between two clumps. Itasca consulting group technical memorandum ICG6863-L. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Itasca Consulting Group. 10.1016/B978-0-12-398500-2.00012-6

49

Rouby D. Guillocheau F. Robin C. Bouroullec R. Raillard S. Castelltort S. et al (2003). Rates of deformation of an extensional growth fault/raft system (offshore Congo, West African margin) from combined accommodation measurements and 3-D restoration. Basin Res.15, 183–200. 10.1046/j.1365-2117.2003.00200.x

50

Rowan M. G. Frank J. Vendeville B. C. (2004). “Gravity-driven fold belts on passive margins,” in Thrust tectonics and hydrocarbon systems. Editor McClayK. R. (Tulsa, OK, USA: AAPG Memoir), 82, 159–184. 10.1306/M82813C9

51

Santolaria P. Ferrer O. Rowan M. G. Roca E. Granado P. Snidero M. et al (2021). From downbuilding to contractional reactivation of salt-sediment systems: insights from analog modeling. Tectonophysics819, 229078. 10.1016/j.tecto.2021.229078

52

Séranne M. Anka Z. (2005). South Atlantic continental margins of Africa: a comparison of the tectonic vs climate interplay on the evolution of equatorial west Africa and SW Africa margins. J. Afr. Earth Sci.43, 283–300. 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.010

53

Smit J. Brun J. P. Fort X. Cloetingh S. Ben-Avraham Z. (2008). Salt tectonics in pull-apart basins with application to the dead sea basin. Tectonophysics449, 1–16. 10.1016/j.tecto.2007.12.004

54

Valle P. J. Gjelberg J. G. Helland-Hansen W. (2001). Tectonostratigraphic development in the Eastern Lower Congo Basin, offshore Angola, West Africa. Mar. Petroleum Geol.18, 909–927. 10.1016/S0264-8172(01)00036-8

55

Vendeville B. C. (2002). A new interpretation of Trusheim's classic model of salt-diapir growth. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Soc. Trans.52, 943–952. 10.1306/A1ADEF73-0DFE-11D7-8641000102C1865D

56

Vendeville B. C. Jackson M. P. A. (1992). The fall of diapirs during thin-skinned extension. Mar. Petroleum Geol.9, 354–371. 10.1016/0264-8172(92)90048-J

57

Vengrovitch D. B. Stovba S. M. (2019). Numerical modelling of salt tectonics with ductile-brittle deformations of salt overburden. Monitoring1, 1–5. 10.3997/2214-4609.201903202

58

Wang X. Luthi S. M. Hodgson D. M. Sokoutis D. Willingshofer E. Groenenberg R. M. (2017). Turbidite stacking patterns in salt-controlled minibasins: insights from integrated analogue models and numerical fluid flow simulations. Sedimentology64, 530–552. 10.1111/sed.12313

59

Wang M. Wang M. Feng W. Yao L. Li H. (2022). Influence of surface processes on strain localization and seismic activity in the longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt: insights from discrete-element modeling. Tectonics41, e2022TC007515. 10.1029/2022TC007515

60

Warsitzka M. Kley J. JaHne-Klingberg F. Kukowski N. (2017). Dynamics of prolonged salt movement in the Glückstadt Graben (NW Germany) driven by tectonic and sedimentary processes. Int. J. Earth Sci.106, 131–155. 10.1007/s00531-016-1306-3

61

Weijermars R. Jackson M. P. A. Vendeville B. (1993). Rheological and tectonic modeling of salt provinces. Tectonophysics217, 143–174. 10.1016/0040-1951(93)90208-2

62

Wu Z. Yin H. Wang X. Zhao B. Zheng J. Wang X. et al (2015). The structural styles and formation mechanism of salt structures in the Southern Precaspian Basin: insights from seismic data and analog modeling. Mar. Petroleum Geol.62, 58–76. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.01.010

63

Xie G.A. Jia D. Zhang Q.L. (2013). Physical modeling of the Jura-type folds in eastern Sichuan. Acta Geol. Sin.87 (6), 773–788.

64

Zhang Y. Li J. Lei Y. Yang M. Cheng P. (2020). 3D simulations of salt tectonics in the Kwanza Basin: insights from analogue and discrete-element numerical modeling. Mar. Petroleum Geol.122, 104666. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104666

65

Zwaan F. Rosenau M. Maestrelli D. (2021). How initial basin geometry influences gravity-driven salt tectonics: insights from laboratory experiments. Mar. Petroleum Geol.133, 105195. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.105195

Summary

Keywords

salt tectonics, diapir evolution, analog modeling, 3D discrete element method, Lower Congo Basin

Citation

Cheng P, Qi Y and Zhao J (2025) Deformation and evolution of Aptian salt tectonics in the central Lower Congo Basin: integrated analogue and 3D discrete element modelling. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1682234. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1682234

Received

08 August 2025

Revised

22 November 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Hu Li, Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, China

Reviewed by

Andrea Zanchi, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Kiichiro Kawamura, Yamaguchi University, Japan

Yiren Gou, Southern University of Science and Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cheng, Qi and Zhao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Cheng, 1061666845@qq.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.