- 1School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Hunan City University, Yiyang, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Key Technologies of Digital Urban-Rural Spatial Planning of Hunan Province, Hunan City University, Yiyang, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Urban Planning Information Technology of Hunan Provincial Universities, Hunan City University, Yiyang, China

The historical and cultural city protection zone is the core carrying area of the old city center, which centrally preserves historical streets, traditional buildings and cultural relics in the process of urban development, and is a key space that reflects the continuity of the city’s historical context and carries the cultural memory of residents. This study employs GIS-based spatial analysis and space syntax theory, combined with relevant policy and planning documents, to process and interpret digitalized historical maps of five development stages (1948, 1967, 1990, 2015, and 2024) of the Yiyang Historic and Cultural City Protection Area. The results reveal that: 1) The spatial morphology of the protection area evolved from a single north-bank settlement along the Zi River into a complex cross-river network, with the road system transforming from disorderly patterns to a highly connected and organized structure. 2) The protection area has consistently remained at the urban core, witnessing the evolution of Yiyang’s old city center through five stages of development, and as a distinctive “local part,” it plays a vital role in promoting the sustainable development of the city’s overall structure. 3) The functional composition of the protection area has shifted from being predominantly residential to a diversified mix of residential, commercial, cultural, industrial, and administrative uses. The concentration of commercial and cultural activities has enhanced the vibrancy of streets and alleys, fostering high-quality development across multiple spatial scales. This study provides empirical evidence for understanding the spatial morphological evolution of old city centers with local historic districts in medium-sized cities like Yiyang and offers practical insights for future urban planning and renewal.

1 Introduction

Driven by the global wave of urbanization, China has experienced an unprecedented transformation in its urbanization process, becoming a focal issue of extensive concern across academic and policy circles. At present, China’s urbanization has entered a mature stage. As the cultural and historical foundation of cities, traditional old urban centers are constrained by their historically formed spatial fabric and infrastructural conditions, making it difficult for them to meet the demands of new urban development. Under the dual pressures of intensive redevelopment and the rise of new urban districts, problems such as functional decline and urban hollowing have become increasingly severe, with approximately 75% of old urban centers urgently requiring revitalization. Against this backdrop, research on the spatial morphological evolution of urban form has emerged as a central topic in the interdisciplinary fields of urban planning and human geography. Systematically examining the adaptive mechanisms between the spatial evolution of traditional old urban centers and the broader process of urban development enables a deeper understanding of how driving forces—such as socioeconomic growth (Thompson et al., 2015), population migration (Chaudhuri, 1992), urbanization (Rogerson and Giddings, 2021), and cultural inheritance (Nyseth and Sognnæs, 2013) interact and couple to shape spatial structures. This provides a multidimensional perspective for comprehensively interpreting the evolutionary logic of old urban centers. In the context of rapid global urbanization, traditional old urban centers serving as the foundation for urban cultural heritage preservation—are facing unprecedented dual challenges of transformation and protection. Therefore, an in-depth investigation into their spatial evolution is crucial for revealing the historical development logic and morphological characteristics of cities. Such research contributes to the rational utilization of urban space, the optimization of functional and spatial organization within protection zones, and the effective preservation of historical and cultural heritage.

With the continuous advancement of spatial analysis technologies and the digital transformation of historical maps, GIS-based spatial analysis and Space Syntax have become effective quantitative tools for accurately analyzing and interpreting the topological relationships and geometric characteristics of various urban districts and historical cities, including heritage quarters. These tools provide new perspectives and methodologies for studying urban block spaces. At the block scale, GIS spatial analysis has been widely recognized as a key approach for investigating spatial attributes such as spatial structure, accessibility, commercial vitality, and residents’ activity patterns. With the advancement of spatial analysis technologies, GIS-based spatial analysis has become a widely used approach for quantifying and visualizing urban spatial structures, transforming abstract spatial features into measurable and interpretable results. It has been effectively applied to evaluate spatial accessibility, commercial vitality, and neighborhood social dynamics in different urban contexts (Mavoa et al., 2012; Fuentes et al., 2020; Wang and Vermeulen, 2021; Cui et al., 2025; Sherwani et al., 2025). Likewise, Space Syntax has demonstrated strong adaptability and validity in studies of historical districts, providing a quantitative and visual framework to analyze spatial morphology, street connectivity, and cultural heritage conservation (Atakara and Allahmoradi, 2021; Eldiasty et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2021; Lai et al., 2023; Lyu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Together, these methods enable a deeper understanding of the spatial logic embedded in historic urban fabrics and offer valuable tools for exploring the interaction between form, function, and culture in the evolution of traditional urban centers. Although existing studies have employed GIS spatial techniques and Space Syntax to deeply explore the topological and geometric characteristics of urban blocks and historic protection zones, most case studies are concentrated in mega or large-scale national historical cities such as Beijing, Xi’an, and Nanjing. Systematic research on small- and medium-sized cities or localized historical districts remains limited, making it difficult to support differentiated renewal and conservation practices across diverse urban scales.

Yiyang, whose name dates back to the Eastern Han Dynasty, is one of China’s four ancient cities whose names have remained unchanged for over two millennia, alongside Handan, Jimo, and Chengdu. The Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone, located along both banks of the Zijiang River, constitutes the core area of the old city, embodying its commercial, cultural, and residential traditions. Its intricate historical fabric, Ming–Qing architectural heritage, and diverse cultural relics together form an organic cultural network that reflects the city’s historical continuity and spatial diversity while offering valuable references for contemporary urban planning and sustainable development. Systematic protection and adaptive reuse of these historical resources not only reveal the spatial logic of urban evolution and regional cultural identity but also strengthen residents’ sense of place and enhance urban cultural vitality. However, with accelerating modernization and urban renewal, the area faces severe challenges such as spatial fragmentation, the erosion of historical character, and declining vitality caused by the weakening of traditional functions.

Against this backdrop, this study takes the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone as a representative case of small- and medium-sized cities to analyze its spatial morphological evolution, heritage conservation, and cultural transmission strategies. By integrating Space Syntax and GIS spatial analysis, it seeks to fill the quantitative research gap on historical spatial evolution and local cultural inheritance in smaller cities, enriching the theoretical paradigm of heritage-oriented urban planning. The proposed analytical framework not only enhances the scientific and systematic understanding of spatial morphology and cultural continuity but also provides practical guidance for urban regeneration. Through quantifying spatial values of traditional streets, prioritizing conservation of Ming–Qing architecture, and evaluating the revitalization potential of heritage sites, this research offers a data-driven foundation for transforming Yiyang’s old city from “static preservation” to “dynamic revitalization,” contributing a replicable model for similar medium-sized historic cities in China.

This study focuses on three main aspects: 1) It examines the specific characteristics of the spatial morphology of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone across key historical periods, identifying how its street network structure, architectural fabric integrity, and functional spatial layout have evolved over time. 2) By applying Space Syntax and GIS spatial analysis, the study quantitatively evaluates the topological connectivity efficiency of historical streets, the spatial distribution density and clustering patterns of Ming–Qing architecture, and the spatial coupling relationships between historical relics and their surrounding environment. Through these analyses, it seeks to uncover the structural features and evolutionary patterns that characterize different stages of development within the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone.

2 Literature review

2.1 Research on protected areas of historical and cultural cities

The term “Historical and Cultural City” is a unique concept in China, corresponding roughly to expressions such as “Old City” or “Historical City” in Western contexts (Gu and Yuan, 2005). The concept has evolved over time and has become increasingly well defined. In February 1982, the State Council approved and circulated the document “Proposal on Protecting China’s Historical and Cultural Cities,” which officially introduced the term at the national level and released the first list of National Historical and Cultural Cities. Although the document did not explicitly define the term, it stated that such cities were ancient centers of politics, economy, and culture, or important sites of modern revolutionary movements and major historical events. These cities preserve abundant cultural and revolutionary relics above and below ground, embodying China’s long history, revolutionary spirit, and brilliant civilization (Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, 2009).

Later that same year, the Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics formally defined historical and cultural cities as “cities rich in cultural relics with significant historical value and revolutionary importance” (People’s Republic of China, 1982). Meanwhile, in Western countries, modern heritage conservation movements began in the 20th century, emphasizing urban heritage and everyday cultural environments. The Athens Charter adopted by the International Congress of Modern Architecture in 1933 declared that “buildings of historical value must be properly preserved and must not be destroyed” (Gold, 2019). The Venice Charter of 1964, adopted by the Second International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, became the first international charter for monument conservation. It articulated key principles of authenticity, recognizability, sustainability, and integrity (International Council on Monuments and Sites et al., 1964).

Within this broader context, the Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone serves as the core component of China’s urban heritage protection system. Its essential value lies not merely in preserving old buildings but in maintaining the city’s historical memory, regional cultural identity, and vibrant community life. It represents a “living historical field” where material space and cultural practices coexist rather than a static “museum of relics.” The fundamental components of such protection zones—historical buildings, traditional streets and alleys, cultural landscapes, and everyday social life—constitute an organic synthesis of tangible and intangible heritage (Tafahomi, 2022).

As the material carrier of local culture and the repository of urban memory, the protection and development of historical and cultural cities have long been central topics in urban planning and cultural heritage studies. With the deepening of related theories and the advancement of practice, research on historical and cultural cities has evolved from isolated, building-level protection to more comprehensive and integrated approaches. Early studies focused on individual historic buildings, emphasizing restoration and adaptive reuse. For instance, Penića M. examined heritage projects in Niš (Serbia) and St. Petersburg (Russia), exploring how historic landmarks can be revitalized through functional adaptation to meet contemporary needs (Penića et al., 2015). Thatcher M. analyzed how state actors determine the motivation, timing, and methods for protecting heritage buildings, showing that national identity construction and cultural nationalism often drive policy decisions, while political or economic factors may also lead to neglect or destruction (Thatcher, 2018).

More recent studies have shifted toward district-level protection, addressing the overall morphology, landscape character, and functional coordination of historic quarters. Wang M. discussed the complexity of decision-making in urban regeneration projects for historical districts in relation to Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG-11) (Wang and Vermeulen, 2021); Shang W. analyzed the spontaneous spaces in Wuhan’s Tanhualin Historic District, revealing how residents’ daily practices significantly influence spatial evolution (Shang et al., 2023); and Pourzakarya M., through the case of Rasht Bazaar in Iran, proposed culture-led regeneration strategies integrating local creative industries for the reuse of abandoned spaces (Pourzakarya and Fadaei Nezhad Bahramjerdi, 2019). From the perspective of revitalization and community participation, several scholars have emphasized value-based assessment and inclusive regeneration. Zhang Y. developed a vitality evaluation framework for Beijing’s nine historical districts, finding that culturally oriented areas such as Shichahai, Nanluoguxiang, and Fuchengmennei exhibit the highest vitality (Zhang and Han, 2022). Tanrıkul A. highlighted the role of community participation and social inclusion in Mediterranean heritage regeneration, demonstrating through cases in Valencia, Palermo, and Chania that collective identity and equitable benefit distribution are essential for sustainable renewal (Tanrıkul, 2023).

In terms of methodology, Li H. employed traditional questionnaire surveys in Nara, Japan, to examine residents’ attitudes toward adaptive heritage reuse, underlining the importance of public engagement (Li et al., 2023); Lu Y. used multi-source data and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the tourism competitiveness of urban heritage districts (Lu et al., 2023); and Malaperdas G. applied GIS techniques to geo-reference, digitize, and visually compare architectural and street elements of the Neokastro Castle in Greece, illustrating the precision advantages of spatial technologies in heritage documentation (Malaperdas et al., 2023).

In terms of research themes, scholars have explored the spatial distribution and vitality patterns of historic districts. Fan J. revealed a northeast–southwest clustering trend in Xi’an’s heritage areas and proposed strategies for balancing commercialization, cultural identity, and infrastructure improvement (Fan et al., 2025); Ding J. combined Baidu heat maps with spatial models to analyze vitality in Nanjing’s historic waterfront, identifying significant spatial heterogeneity among influencing factors (Ding et al., 2023); and Catalanotti C. investigated how commercial activities in Venice’s historic center shape residential dynamics and urban regeneration, offering insights into bottom-up revitalization practices (Catalanotti, 2023).

2.2 Research on urban street morphology

The concept of urban spatial morphology carries a similar meaning in both Chinese and English, referring to the structure and organization of urban space, including functional layout, block configuration, building scale, and the spatial relationships among various urban elements. The term “morphology” originates from the Greek words morphē(form) and logos (logic), meaning the structural logic of form. According to Cihai (a major Chinese encyclopedia), morphology refers to “the manifestation of a thing under certain conditions, encompassing both physical and spiritual forms” (Duan and Qiu, 2008). Scholarly attention to urban morphology dates back to the 19th century, when the concept was initially grounded in geographical studies of urban spatial structure. In 1936, German geographer Herbert Louis proposed the concept of the urban fringe, marking the beginning of systematic research on the evolution of urban spatial form (Louis, 1936). Later, Kevin Lynch’s seminal work The Image of the City (1960) introduced the concept of mental maps, identifying five key elements—paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks—to explain how citizens perceive and understand cities. This work opened a new avenue for architectural and planning studies of urban spatial morphology (Lynch, 1960).

In China, the practice of urban spatial form regulation has a long history, with early codifications found in The Rites of Zhou: Kaogong Ji, which prescribed principles for the siting and construction of ancient capitals. However, theoretical research on urban morphology emerged much later. With the urban development driven by the reform and opening-up policy in the 1980s, Academician Qi Kang introduced the concept of urban morphology to China, initiating systematic domestic studies in this field (Qi, 1999). Since then, scholars have explored the relationships between urban morphology, functional zoning, and urban evolution. For example, Ye Qiang and colleagues analyzed how functional divisions within cities influence their spatial transformation (Ye et al., 2019), while Hu Jun and Gu Chaolin classified urban forms into centralized and polycentric (clustered) types, arguing that these distinct structures follow fundamentally different patterns of spatial evolution (Gu, 1995).

Urban morphology research spans multiple disciplines such as urban planning, geography, and architecture, with increasingly diverse analytical approaches. With technological advancement, GIS spatial analysis has become a fundamental method for quantifying urban form, enabling the evaluation of compactness, land-use intensity, and walkability in cities across different contexts (Taleai and Taheri Amiri, 2017; Xia et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). Meanwhile, Space Syntax has developed into a core framework for understanding the spatial logic of urban morphology by quantifying topological relationships, connectivity, and accessibility through indicators such as integration and choice. Studies combining Space Syntax and GIS have revealed how spatial configuration shapes urban development and social activities—for instance, identifying correlations between integration and land-use intensity, pedestrian flow, or commercial vitality in cities such as Wuxi, Valencia, and Hefei (Xing and Guo, 2022; Zhou and Zheng, 2023; Durá-Aras et al., 2025). Large-scale analyses based on open data further demonstrate how multi-scale street networks influence accessibility and urban vitality across diverse urban contexts (Boeing, 2020; Zhou and Wang, 2023). Overall, integrating Space Syntax with GIS provides a multi-scalar analytical framework—from micro-level street networks to macro-level urban structures—facilitating a deeper understanding of spatial evolution and offering quantitative support for improving urban design, walkability, and the adaptive renewal of historical districts.

In the field of urban spatial morphology, research exploring the interrelationships among “rivers, riverside blocks, and their internal evolution” remains limited. Existing studies primarily focus on the overall urban structure and function, yet insufficiently address the distinct spatial characteristics of such river–city systems. As a result, the complex interactive dynamics between rivers and adjacent urban blocks, as well as the internal spatial evolution within these areas, have not been fully revealed.

At the same time, studies on the historical evolution of urban spatial morphology remain relatively scarce, particularly regarding the mechanisms of dynamic change. Most existing research is confined to static analyses of specific periods, lacking investigation into the temporal processes and driving factors underlying morphological transformation across different stages, which constrains a holistic understanding of urban spatial dynamics. Furthermore, there is a notable gap concerning the contextual sensitivity of Space Syntax indicators. Given the considerable variation in spatial characteristics among cities and across historical periods, the performance and applicability of these indicators require further examination to enhance their accuracy and reliability in the study of urban spatial morphology.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

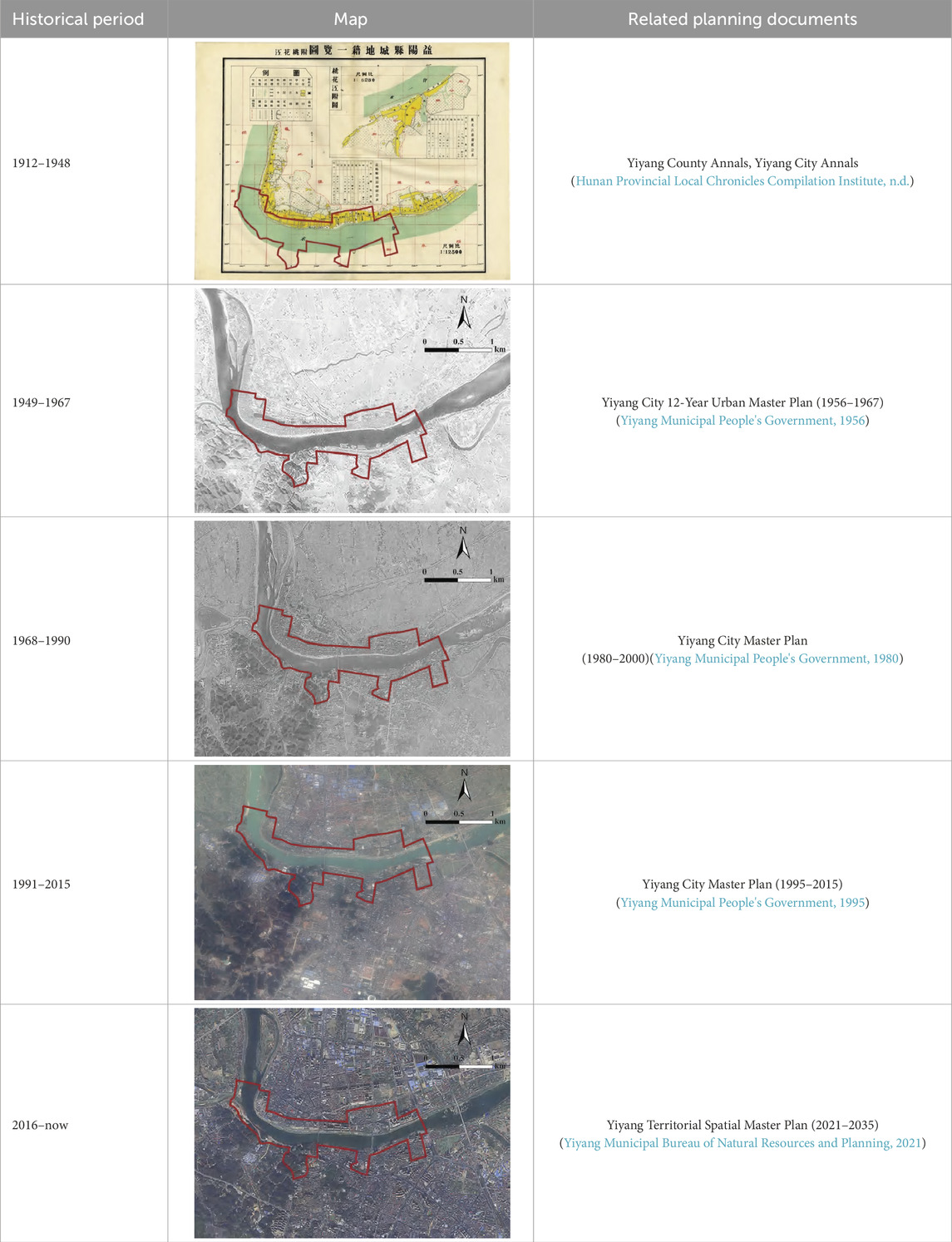

Based on the Yiyang Territorial Spatial Master Plan (2021–2035) and the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Plan (2021–2035), the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone covers the old urban area on both banks of the Zijiang River, extending north to Jinhua Lake Road and Wuyi Road, south to Binjiang Road and Luofan Road, west to the confluence of the Zijiang and Zhixi Rivers, and east to Longzhou Bridge, with a total area of 574.18 ha, including 2.08 km2 of river surface (Figure 1). The protected area has experienced five historical stages of spatial evolution (Table 1). From 1912 to 1948, river navigation stimulated port-driven commerce and cultural exchange, forming the initial historic core, with flooding leading to a high proportion of water surface. Between 1949 and 1967, post-liberation urban construction shifted the functional center southward under state-led planning, redefining cultural and social functions. From 1968 to 1990, social upheavals disrupted cultural activities, while industrialization accelerated urban expansion, though parts of the district retained historical traces. During 1991–2015, rapid urbanization and improved riverbank connectivity enhanced recognition and protection of the historic zone. Since 2016, Yiyang has emphasized the integration of cultural heritage with modern urban life, promoting revitalization through coordinated planning, enhanced conservation awareness, and adaptive reuse.

Table 1. Development stage classification of the Yiyang historical and cultural city protection zone. (Source: drawn by the authors based on the Yiyang city map and satellite imagery).

3.2 Data sources

The data sources for this study are as follows:

1. Collection of spatial and historical data. Map information of the protection zone was obtained by compiling and analyzing historical records and local chronicles of Yiyang City since the Republic of China period, including Yiyang County Annals, Yiyang City Annals, and successive urban planning documents. These materials provide information on the evolution of the city’s central area layout, block structure, and other spatial elements across different historical stages.

2. Selection of key temporal nodes. Based on Yiyang’s urban development trajectory, which has undergone multiple planning policy updates over time, the development of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone was divided into five stages according to historical archives, field surveys, and planning documents. The years 1948, 1967, 1990, 2015, and 2024 were selected as representative research nodes (Table 1).

3. Acquisition of land-use data. Land-use maps of the protection zone were obtained from the Compilation of Basic Data on the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone provided by the Yiyang Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning (https://www.yiyang.gov.cn/jsj/31736/31738/content_1462041.html).

4. Digitization of building footprints. Historical maps from 1948 and satellite imagery from 1967, 1990, 2015, and 2024 were used to delineate building outlines for different periods. Due to the technological limitations of the early years, no high-resolution satellite data are available before 1967, resulting in incomplete building-contour information for that period.

5. Field surveys. Supplementary on-site investigations were conducted to document the spatial distribution and evolution of architectural forms, streets, commercial centers, and cultural and educational facilities within the old city.

Given the inherent limitations of historical maps—such as blurriness, missing details, and satellite angle deviations—the redline boundary of the protection zone may exhibit slight rotational offsets when aligned with satellite imagery. To improve spatial accuracy, the Georeferencing tool in ArcGIS 10.8 was used to perform control-point registration, ensuring a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of less than 5 m.

3.3 Methods

3.3.1 Space syntax

Space Syntax, developed by Bill Hillier and Julian Hanson at University College London in the 1970s (Hillier and Hanson, 1984), is a theoretical and methodological framework for analyzing and describing urban spatial morphology and its interrelationships. It measures spatial accessibility through indicators such as integration, choice, and synergy. According to spatial configuration theory, urban form significantly influences human behavior: streets with higher integration tend to attract more pedestrian and commercial activities due to their accessibility. Cities function as complex dynamic systems in which street networks organize flows of people and vehicles, shaping urban activity patterns, while land-use types regulate these movements. Space Syntax reveals the intrinsic relationship between the physical environment and socio-cultural functions, serving as a powerful analytical tool in urban planning, architecture, transportation, and social sciences. The integration index indicates how closely a spatial element is connected to others within the system reflecting its accessibility, centrality, and potential to attract movement. Its calculation formula is as follows (Hillier, 1999):

In Formula 1:

Choice reflects the frequency with which a spatial element lies on the shortest topological paths connecting pairs of nodes. Unlike integration, which emphasizes spatial centrality, choice focuses on through-movement potential, evaluating how likely a space is to serve as a preferred route for movement within the network. A higher choice value indicates a greater probability of the space being selected as a primary pedestrian or traffic pathway. The calculation formula for choice is as follows (Penn, 2003):

In Formula 2:

Synergy (Seamon, 2015) reflects the degree of interaction and coordination between local and global spatial structures. It reveals how local spaces are interconnected with the broader urban system and how they influence the city’s overall function and form. By analyzing the integration and connectivity between local and global spaces, synergy helps researchers understand the complex relationships within urban morphology and provides a basis for optimizing spatial layout, improving efficiency, and enhancing urban vitality. The calculation formula for synergy is as follows:

In Formula 3:

3.3.2 GIS overlay analysis

GIS, as a core technological tool for spatial data processing and analysis, serves as a vital bridge between theoretical research on urban spatial morphology and practical planning applications. It enables the quantification of spatial structures, monitoring of morphological evolution, and support for planning decisions. The concept of GIS was first introduced in 1963 by Canadian surveyor R. F. Tomlinson for the national land-use management program, and later elaborated in his 1975 monograph Canada Geographic Information System, which outlined the core principles of layered spatial data management, geocoding, and analytical logic (Tomlinson, 1990). These principles laid the foundation for subsequent GIS development.

Among its various analytical techniques, the overlay analysis method is particularly important. By superimposing multiple spatial layers—such as street networks, POI density maps, and population distribution data—overlay analysis reveals spatial relationships among different elements (Stevens and Thai, 2024). In urban planning, this method helps analyze the spatial distribution of functional zones, accessibility, and the alignment between population and resources. In this study, overlay analysis is employed to integrate and correlate multi-scale spatial data within the protection zone, exploring the spatial correspondence among population mobility, accessibility, and the clustering of commercial and cultural activities.

4 Results

4.1 Analysis of multi-scale spatial evolution of block morphological types in different periods

4.1.1 1948: a period of spontaneous growth characterized by belt-shaped streets and alleys distributed along the Zijiang river

During the Republic of China period, maps reveal that the street texture of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone exhibited a simple spatial pattern. The streets were organized around a central pedestrian street, forming a belt-shaped, grid-like structure characterized by parallel arrangements. The internal alleys were generally narrow, densely built, and varied in width and height, creating a compact yet interconnected spatial network. The urban blocks were primarily distributed along the Zijiang River, highlighting the close relationship between the built environment and the natural landscape. Comparison between maps from the Republic of China period and 1948 indicates that the internal spatial structure and street layout remained largely unchanged.

Figures 2, 3 present the syntactic axial map for 1948, overlaid with data on commercial and cultural activity clusters at a micro radius (R = 800 m), to analyze the choice and integration of the protection zone’s spatial morphology between 1912 and 1948.

Figure 2. Multi-scale analysis of Yiyang historical and cultural protection zone (1948): selection and integration. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 3. Distribution of commercial activity gathering points and cultural activity gathering points in 1948. (a) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1948). (b) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1948). (c) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1948). (d) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1948). (Image source: drawn by the author).

In the choice analysis, as the scale increased from micro (800 m) to meso (1,600 m) and macro (3,200 m), the core streets evolved from a dispersed to a linear structure. The pedestrian street consistently maintained its central role, while Wuyi Road gradually emerged as another key axis accommodating residents’ diverse travel needs. At the meso and macro scales, the foreground network shifted toward the Zijiang riverfront, suggesting that the protection zone’s development extended southeastward along Wuyi Road (Figure 2). The micro-scale overlay of choice values with activity data revealed that commercial and cultural clusters were mainly concentrated around the pedestrian street and Wuyi Road. Functionally, this spatial clustering corresponds closely to residents’ daily patterns of consumption, social interaction, and cultural participation. The concentration of commercial activities efficiently supported basic services such as shopping and dining, while nearby cultural clusters met residents’ needs for leisure, community engagement, and recreation—demonstrating the strong spatial coupling between urban form and socio-economic activity (Figures 3a,b).

In the integration analysis, at the micro scale (800 m), the city’s river-oriented morphology became increasingly evident. The belt-shaped historical streets, shaped by the port economy along the Zijiang, fostered highly accessible riverfront zones, which in turn promoted the development of the pedestrian street and Wuyi Road. As the scale expanded to the meso (1,600 m) and macro (3,200 m) levels, integration values increased, and the spatial advantage extended toward the northern bank, forming a denser accessibility network along the riverfront. The protection zone began to exhibit the early grid-pattern structure characteristic of its later urban form (Figure 2). Overlay analysis at the micro scale further indicated a strong spatial correlation between high-integration street nodes and commercial and cultural clusters, with their core overlaps concentrated in areas of high-frequency daily activities. These high-integration zones, benefiting from superior accessibility, provided the fundamental spatial conditions that supported the clustering of commerce and cultural life within the protection zone (Figures 3c,d).

4.1.2 1967: pioneering expansion toward the south

Figures 4, 5 present the syntactic axial map of 1967, overlaid with data on commercial and cultural activity clusters at a micro radius (R = 800 m), to analyze the choice and integration of the protection zone’s spatial morphology from 1949 to 1967.

Figure 4. Multi-scale analysis of Yiyang historical and cultural protection zone (1967): selection and integration. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 5. Distribution of commercial activity gathering points and cultural activity gathering points in 1967. (a) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1967). (b) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1967). (c) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1967). (d) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1967). (Image source: drawn by the author).

In the choice analysis, the foreground network at the micro scale was concentrated in the northwestern part of the protection zone, particularly within the Shimatou Historical and Cultural Block, while the original core streets remained clustered around the pedestrian street. At the meso and macro scales, the improvement of the street network in the northwest and the emergence of development on the southern bank of the Zijiang River marked the formation of a “one river, two banks” spatial pattern. The dominance of Zijiang Road and Binjiang Road in terms of choice values further strengthened this trend (Figure 4). At the micro scale, analysis of commercial and cultural activity clusters revealed that commercial activities were concentrated around the pedestrian street, whereas cultural activities were mainly located south of Binjiang Road. This spatial shift, significantly influenced by the social policies of the time, reduced the overall number of activity clusters but also broke the long-standing pattern of concentration north of the Zijiang, signaling the beginning of urban expansion toward the southern bank (Figures 5a,b).

In the integration analysis, the increased street-network density near the confluence of the riverbanks reflected improvements in local economic activity, though overall integration values along the riverfront were slightly lower than in 1948. Across micro (800 m), meso (1,600 m), and macro (3,200 m) scales, the foreground network extended outward along both banks of the Zijiang. At meso and macro scales, a “north–south dual-axis” structure formed by the pedestrian street, Zijiang Road, Binjiang Road, and Lujiashang Road enhanced spatial integration and improved inter-street accessibility (Figure 4). The micro-scale overlay of integration and activity data revealed a positive correlation between integration and the density of commercial clusters—streets with higher integration tended to exhibit more frequent commercial activities. In contrast, the areas surrounding cultural clusters showed relatively lower integration, likely due to the early stage of cross-river urban development. Although cultural functions had begun to extend south of the Zijiang, the limited river-crossing infrastructure, underdeveloped supporting facilities, and residents’ habitual preference for established northern neighborhoods constrained the activation of spatial connectivity and use intensity in the southern areas (Figures 5c,d).

4.1.3 1990: a transitional period of commercial prosperity and transportation network improvement

Figures 6, 7 present the syntactic axial map for 1990, overlaid with commercial and cultural activity clusters at a micro radius (R = 800 m), to analyze the choice and integration characteristics of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone from 1968 to 1990.

Figure 6. Multi-scale analysis of Yiyang historical and cultural protection zone (1990): selection and integration. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 7. Distribution of commercial activity gathering points and cultural activity gathering points in 1990. (a) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1990). (b) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (1990). (c) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1990). (d) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (1990). (Image source: drawn by the author).

The results of the choice and integration analyses were generally consistent. As the spatial scale expanded, Wuyi Road, Zijiang Road, and Maliang Bridge (formerly the First Bridge) increasingly demonstrated strong spatial advantages as streets with high integration and choice values. This pattern reflects the impact of the Yiyang City Master Plan (1990–2010), which adopted a compact, contiguous development strategy for the planning and construction of historic districts (Figure 6). At the micro scale, comparison with the previous stage revealed a significant increase in the number of commercial and cultural activity clusters. Commercial clusters became highly concentrated along the pedestrian street and Zijiang Road, indicating a higher probability of being selected as part of residents’ shortest daily travel paths. The completion and opening of Maliang Bridge effectively removed the barrier of cross-river travel, enabling commercial activity to expand from the northern bank to the southern areas of the Zijiang. Meanwhile, cultural clusters exhibited a more pronounced cross-river spatial pattern, maintaining moderate density along Zijiang Road while increasingly spreading toward the southern bank, providing greater spatial diversity and accessibility (Figures 7a,b).

In the integration analysis, the Shimatou Historical and Cultural Block, centered on the pedestrian street, began to show a clear belt-shaped, grid-radiating street network even at the micro scale (800 m). As the radius expanded, the foreground network continued to shift southeastward, with Zijiang Road and Maliang Bridge emerging as the primary structural axes with the highest integration values, while integration levels among secondary streets varied slightly (Figure 6). Overlay analysis of street integration with functional activity clusters at the micro scale revealed a positive correlation between commercial activity density and integration—commercial clusters were more concentrated in areas with high integration, primarily on the northern bank of the Zijiang. Cultural clusters, by contrast, appeared in both the traditional northern district and the newly developed southern areas, though the integration values of streets surrounding cultural clusters were generally lower than those around commercial ones (Figures 7c,d).

4.1.4 2015: a period of rapid development and street network improvement

Figures 8, 9 present the syntactic axial map for 2015, overlaid with commercial and cultural activity clusters at a micro radius (R = 800 m), to analyze the choice and integration characteristics of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone between 1991 and 2015.

Figure 8. Multi-scale analysis of Yiyang historical and cultural protection zone (2015): selection and integration. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 9. Distribution of commercial activity gathering points and cultural activity gathering points in 2015. (a) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (2015). (b) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (2015). (c) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (2015). (d) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (2015). (Image source: drawn by the author).

In the choice analysis, Wuyi Road maintained its traditional central position, with the foreground network at the micro scale concentrated primarily on the northern bank of the Zijiang River. At the meso and macro scales, improvements in the northern urban morphology and the completion of Baimashan Bridge (formerly the Third Bridge) promoted expansion toward the southern bank. The openings of Maliang Bridge (formerly the First Bridge) and Baimashan Bridge provided residents on both banks with multiple transportation options (Figure 8). Micro-scale overlay analysis revealed a significant increase in both commercial and cultural activity clusters under the city’s rapid expansion. Commercial clusters remained primarily concentrated on the northern bank, though their presence on the southern bank also increased. Meanwhile, cultural clusters were mostly distributed around Wuyi Road, where high choice values indicate enhanced accessibility; their broader and denser distribution reflects growing cultural engagement (Figures 9a,b).

In the integration analysis, the intensification of economic activity around Wuyi Road increased the street network density connected to Maliang Bridge and Baimashan Bridge, producing a cross-scale spatial shift in the foreground network toward both banks of the Zijiang. The northern area achieved a substantial rise in spatial integration compared to earlier periods, especially at the macro scale (R = 3,200 m), where a clear topological advantage emerged. Together, Wuyi Road and the two bridges formed a “

4.1.5 2024: a period of quality enhancement and urban optimization

Figures 10, 11 present the syntactic axial map for 2024, overlaid with commercial and cultural activity clusters at a micro radius (R = 800 m), to analyze the choice and integration characteristics of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone between 2016 and 2024.

Figure 10. Multi-scale analysis of Yiyang historical and cultural protection zone (2024): selection and integration. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 11. Distribution of commercial activity gathering points and cultural activity gathering points in 2024. (a) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (2024). (b) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter choice radius in the study area (2024). (c) Distribution of commercial activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (2024). (d) Distribution of cultural activity gathering points within an 800-meter integration radius in the study area (2024). (Image source: drawn by the author).

In the choice analysis, as the analytical scale expanded from micro (800 m) to meso (1,600 m) and macro (3,200 m), the core street network extended from the pedestrian street of the Shimatou Historical and Cultural Block northward toward Wuyi Road in the Dongmen Historical Block and southward toward Xiliuwan Bridge. With the continuous expansion of bridge infrastructure, Xiliuwan Bridge has increasingly become a major corridor for medium- and long-distance travel (Figure 10). At the micro scale, the analysis of commercial and cultural clusters revealed that, following the shift in urban planning policies from broad macro-level control to refined spatial guidance, both types of activity clusters exhibited wider spatial coverage and more optimized layouts. This optimization enhanced accessibility and provided residents with greater flexibility and choice in selecting destinations for daily and leisure activities (Figures 11a,b).

The integration analysis produced similar findings. At the micro level, Wuyi Road, Zijiang Road, Binjiang Road, and Maliang Bridge (formerly the First Bridge), Xiliuwan Bridge, and Baimashan Bridge (formerly the Third Bridge) together formed a “three-vertical, three-horizontal” grid-like core structure. The strong spatial connectivity of Wuyi Road and Xiliuwan Bridge significantly improved accessibility across adjacent streets, further reinforcing the integration advantage of the radiating grid network (Figure 10). Quantitative analysis of the relationship between street integration values and the density of commercial and cultural activity clusters indicated that areas with higher integration consistently contained a greater number and density of both cluster types. These high-density cores were highly concentrated within historic and cultural districts, suggesting that these areas owing to their distinctive historical and cultural significance have become the primary hotspots for both commercial vitality and cultural activities (Figures 11c,d).

4.2 Comparative analysis between the protection zone and overall urban development patterns

4.2.1 Analysis of internal spatial parameters of the protection zone

This study objectively analyzes the evolution of spatial morphology within the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone by systematically examining Space Syntax parameters across different historical periods (Table 2; Figures 12–14).

Table 2. Synergy analysis of the Yiyang historical and cultural city protection zone at different measurement radii in different periods. (Source: drawn by the author).

Figure 12. Changes in the proportion of alleyways occupied by foreground networks and background networks in historic cultural districts during different periods. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 13. Changes in the average integration degree and maximum integration degree of historic cultural districts in different periods. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 14. Changes in the synergy degree of historical and cultural districts in different periods. (Image source: drawn by the author).

In the early development stage, the synergy index exhibited a significant increase from micro to macro scales, with an average value exceeding 0.85, indicating a high level of coordination between local and global spatial structures. This suggests that spatial layout and functional organization were well-aligned. As the adaptive evolution of historical blocks progressed, a hierarchical spatial order gradually emerged, reflecting improved integration capacity and diversification of residents’ daily activities. The foreground network ratio was notably higher than in later stages, demonstrating the rational organization of internal spaces and the adaptive optimization of spatial form to meet functional needs.

After 1949, the implementation of the Yiyang 12-Year Urban Master Plan (1956–1967) shifted the city’s development focus southward across the Zijiang River. This planning initiative standardized the internal spatial form and increased the number of mixed-use streets. Although the mean and maximum integration values remained stable, the mean synergy value declined sharply—from 0.85 to 0.61—indicating that the planned adjustments modified the original fractal spatial hierarchy. Spatial changes during this period were characterized by the development of new areas and the functional adjustment of existing ones, reflecting the optimization of the city’s functional structure.

Between 1968 and 1990, the opening of Maliang Bridge (formerly the First Bridge) significantly strengthened cross-river connections and stimulated economic growth on the southern bank. The average synergy decreased further to 0.51, suggesting adaptive restructuring in response to new transportation conditions and urban demands. The decline in the foreground network ratio and the rise in the background network ratio indicated a redistribution of spatial importance from core to peripheral areas, marking a reconfiguration of the city’s topological network and demonstrating its self-adaptive optimization process.

From 1991 to 2015, planning and renewal efforts led to a more balanced distribution of mixed-use streets and an improved fractal structure within the protection zone. The completion of Baimashan Bridge (formerly the Third Bridge) further optimized the urban functional layout. Although morphological changes were moderate, their impact on the spatial hierarchy was substantial: the macro-level integration maximum declined, suggesting a weakening of central agglomeration, while the synergy value rose again from 0.51 to 0.61, indicating enhanced coordination between spatial and functional systems. The recovery of the foreground network ratio and the decline of the background ratio reflected a more rational spatial configuration.

Since 2016, the completion of Xiliuwan Bridge has markedly improved north–south accessibility, commuting efficiency, and cross-river integration in economic, cultural, and social dimensions. Both the average synergy and the foreground network ratio show a steady upward trend, reflecting improved coordination and connectivity of core functional areas. At the macro scale, the mean and maximum integration remained stable, suggesting that Yiyang’s urban spatial structure continues to maintain overall stability, coherence, and orderly development.

4.2.2 Comparative evolution of local and overall urban spatial morphology

Since the Republic of China era, the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone has experienced a progressive transformation from spontaneous expansion to structural adjustment and, ultimately, to integrated optimization. During the initial stage, the protection zone served as Yiyang’s core in spatial, social, and cultural terms, maintaining strong local–global synergy and shaping the city’s foundational urban logic. The transformative expansion period (1948–1967), driven by the 12-Year Urban Master Plan, triggered southward growth and internal renewal. Integration and synergy analyses (Figures 15, 16) reveal the emergence of corridor-based spatial reorganization and a gradual weakening of macro-level coordination. In the transitional adjustment stage (1968–1990), improved cross-river connectivity facilitated urban dispersal, resulting in a shift from a monocentric to a multi-core structure. Although accessibility increased, synergy patterns became increasingly dispersed, indicating declining coordination between the protection zone and new development areas.

Figure 15. Relationship between integration of Yiyang historical and cultural city protection zone and central urban area of Yiyang city in different periods. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 16. Analysis diagram of synergy degree of historical and cultural districts with different measurement radii in different periods. (Image source: drawn by the author).

From 1991 to 2015, the implementation of the Yiyang City Master Plan enhanced spatial efficiency and concentrated economic-cultural functions toward the south and east. While the macro-scale integration of the historical district slightly diminished, its micro-scale connectivity advantage expanded, confirming its sustained structural significance within the urban system. Entering the quality enhancement and optimization phase (2016–2024), the Territorial Spatial Master Plan redefined the city under a “one core, one sub-center, one belt, seven zones” hierarchy, reinforcing the protection zone’s strategic centrality. Synergy scatter plots show vertical clustering, and integration values increased at multiple scales, reflecting strengthened coordination between heritage preservation and contemporary urban development. Overall, this evolutionary process demonstrates enhanced spatial coupling, functional upgrading, and intensified heritage–modernization synergy, driving improvements in urban quality, cultural vitality, and sustainable competitiveness.

4.3 Changes and causes of functional and architectural form of the cultural famous city protection area in different periods

4.3.1 Evolution of functional zoning in different historical periods

Across the five studied periods, the functional attributes of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zoneunderwent significant transformations, reflecting the combined influence of social, economic, and political factors. (Figures 17, 18) clearly illustrates the temporal evolution of functional zoning within the protection zone, revealing a shift in both the overall area and its five internal historic and cultural districts from simple to complex and from single-purpose to multi-functional configurations (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Locations of historical and cultural blocks in the study area. (Image source: drawn by the authors based on the study area map and satellite images).

By analyzing the functional changes across different periods, this study captures the evolving urban demands and development trends in residential, commercial, cultural, administrative, and industrial dimensions. Such analysis provides valuable insight into the spatial logic and developmental mechanisms underlying the transformation of Yiyang’s urban form and functional organization.

In 1948 (Figure 18a), the functional zoning of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone was primarily concentrated on the northern bank of the Zijiang River, encompassing the Shimatou and Dongmenkou historical districts, while the southern bank remained largely undeveloped. The urban function was predominantly residential, with limited commercial and cultural activity, resulting in a spatial pattern that was both structurally and functionally simple. By 1967 (Figure 18b), the social turbulence of the period disrupted the cultural vitality of the protection zone, constraining commercial activities. Residential land accounted for over 60% of the total area and began extending southward into the Tuzishan and Xinyi University historical districts. This dominance of residential land use reflects the city’s focus on basic living functions during this stage of development. In 1990 (Figure 18c), as urban reforms deepened, the city’s functional composition became increasingly diversified, though residential use remained the core. Educational facilities emerged near the Dongmenkou and Tuzishan districts, while administrative offices were concentrated in the Xinyi University area indicating a strong southward development orientation within Yiyang’s planning framework. By 2015 (Figure 18d), with accelerating urbanization, land-use functions underwent further optimization and restructuring. Portions of former residential zones near Shimatou and Dongmenkou were converted into mixed residential–commercial areas, while the share of commercial land rose significantly. The Huilongshan historical district began developing as a multi-functional area, integrating residential, commercial, administrative, and cultural uses, thereby enhancing its comprehensive service capacity. In 2024 (Figure 18e), Yiyang’s urban development entered a new phase, shifting from rapid expansion to high-quality growth, characterized by greater functional diversity and complexity. Residential use remained dominant, but the proportions of educational and industrial land increased markedly. The expansion of educational land underscores growing emphasis on talent cultivation and knowledge innovation, while the refinement of industrial land reflects the city’s industrial upgrading and transformation toward advanced and high-tech sectors. Overall, Yiyang’s urban form has evolved beyond its traditional mono-functional structure, developing into a multi-layered, integrated spatial systemwith enhanced coordination and balance among functions.

Figure 18. Functional zoning maps of different time periods. (a) Functional zoning of the study area (1948). (b) Functional zoning of the study area (1967). (c) Functional zoning of the study area (1990). (d) Functional zoning of the study area (2015). (e) Functional zoning of the study area (2024). (Image source: drawn by the author).

4.3.2 Evolution of architectural form in different historical periods

From a holistic perspective, the architectural texture of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone demonstrates a clear evolution across the three periods from dispersed and traditional forms to more compact, orderly, and modernized patterns revealing the city’s spatial development trajectory. In 1990 (Figure 19a), the architectural layout within the protection zone was relatively scattered, with most buildings aligned linearly along roads and the Zijiang River. Building density was low, and the overall texture retained a strong historical imprint, preserving much of the traditional street-and-lane configuration. This pattern reflected a slow-paced urban development and an emphasis on maintaining the organic authenticity of the historical and cultural landscape. By 2015 (Figure 19b), building concentration had increased significantly. New constructions filled and expanded existing areas, leading to noticeably higher density. The influence of the road network on building orientation became more pronounced, producing a more structured and organized spatial texture. This change signified both the city’s growing economic dynamism, which spurred building renewal, and the strengthened role of urban planning in regulating spatial utilization and shaping a more coherent built environment. In 2024 (Figure 19c), architectural texture achieved a higher degree of regularity and integration with modern elements. Buildings continued to grow in number and density, while their relationship with urban features—such as roads and rivers—became more harmonious. Overall, the spatial form now combines historical continuity with modern urban design principles: it preserves traces of the historical fabric while exhibiting a vibrant, orderly, and contemporary cityscape. This transformation reflects Yiyang’s ongoing effort to balance heritage preservation with modernization, ensuring that the protection zone’s architectural fabric both embodies cultural legacy and adapts to the demands of contemporary urban life.

Figure 19. Architectural texture evolution maps of different time periods. (a) Architectural texture of the study area (1990). (b) Architectural texture of the study area (2015). (c) Architectural texture of the study area (2024). (Image source: drawn by the author).

As shown in Figure 20, the building density of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone in 1990, 2015, and 2024 demonstrates a clear pattern of dynamic evolution. Detailed analysis across these three periods reveals a trajectory of change from low to high density and from concentration to spatial dispersion, reflecting the morphological transformation of the protection zone throughout the city’s development process. In 1990 (Figure 20a), influenced by the limited urban scale and functional orientation of the time, the overall building density was relatively low, with the Shimatou Historical District as the main concentration area, displaying a clear clustering effect. The density distribution was relatively uniform, indicative of an early urban development stagecharacterized by low land-use efficiency and a slow pace of spatial expansion. By 2015 (Figure 20b), with the acceleration of urbanization, building density increased significantly, particularly around the Shimatou and Dongmenkou historical districts. The emergence of mixed residential–commercial land use further heightened density in these core areas. The growing share of commercial land in overall urban land use stimulated commercial vitality, while the Huilongshan Historical District on the southern bank of the Zijiang River also experienced a marked rise in building density. This shift signaled the city’s progressive expansion toward the south and the strengthening of cross-river development dynamics. In 2024 (Figure 20c), the building density within the protection zone continued to increase, reflecting both policy-driven spatial refinement and improvements in land-use efficiency. Targeted redevelopment efforts reduced excessive crowding and eliminated structures inconsistent with the historical character, achieving balanced density control that preserved the scale and texture of traditional streets while enhancing the quality of the living environment. In peripheral areas such as Huilongshan, moderate increases in building density accompanied the integration of cultural tourism and leisure-oriented functions. These developments, undertaken under strict heritage protection principles, maintained a reasonable balance between historical authenticity and ecological capacity. Overall, the 2024 pattern illustrates a harmonious coexistence of preservation and modernization, where Yiyang’s historical protection zone achieves both cultural continuity and sustainable urban growth.

Figure 20. Building density analysis maps of different time periods. (a) Building density of the study area (1990). (b) Building density of the study area (2015). (c) Building density of the study area (2024). (Image source: drawn by the author).

4.3.3 Visual documentation of morphological evolution

Figure 21 vividly captures the transformation of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone across different historical stages through a series of photographs taken from three perspectives—panoramic views, building outlines, and architectural details.

Figure 21. The changes of the Yiyang historical and cultural city protection zone. (Image source: Photographed and collated by the authors based on the archival materials of Yiyang city).

First, the panoramic views illustrate the overall landscape along both banks of the Zijiang River. In 1948, the protection zone consisted mainly of natural scenery with sparse buildings and a low degree of urbanization. By 1967, urban development had intensified, and construction within the zone increased noticeably. The 1990 images reveal denser building clusters and a visibly accelerated urbanization process. The photos from 2015 to 2024 further depict a modernized cityscape, with high-rise buildings and a more diverse urban skyline. Second, the building outline images focus on internal spatial organization and architectural layout. In 1948, the structures were simple and low-rise. By 1967, a greater diversity of architectural forms appeared, including some distinctive landmark buildings. In 1990, the urban form became more complex, with the emergence of multi-story buildings symbolizing urban vitality. The 2015 and 2024 outline maps present a more orderly and modern building pattern, characterized by higher density and vertical development, reflecting the deepening of urbanization. Third, the architectural detail photos highlight the micro-level characteristics of the buildings that ornamentation, structure, and materials revealing the evolution of construction styles and technologies. In 1948, details reflected a traditional style with simple materials and techniques. The 1967 and 1990 photographs show increasing stylistic diversity and technological advancement, while those from 2015 to 2024 capture refined modern designs featuring new materials and construction methods, embodying the progress of both architectural art and engineering innovation.

Overall, these three visual perspectives provide a dynamic and comprehensive record of the protection zone’s transformation from traditional simplicity to modern complexity—illustrating the intertwined evolution of urban form, architecture, and cultural identity in Yiyang.

5 Discussion

5.1 Evolution of road morphology within the protection zone

The transformation of internal streets and alleys in the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone across different historical periods has significantly altered both mobility choices and connectivity within the area. A series of highly goal-oriented planning policies fundamentally restructured the living fabric of the old city center, triggering stage-specific evolutions in the spatial extension paths and morphological features of its core districts. The Yiyang 12-Year Urban Master Plan (1956–1967), drafted in 1952, was based on the existing urban spatial form. Accompanied by notable changes in spatial syntax parameters and foreground network patterns, the development model shifted from spontaneous growth to planning-oriented expansion, leading to the emergence of a belt-shaped grid spatial structure. This evolution reflected the protection zone’s rapid expansion from the Shimatou Historical District on the north bank toward the Dongmenkou Historical District in the east and south. Since 1968, the opening of Maliang Bridge (formerly the First Bridge) marked a crucial turning point in Yiyang’s spatial development, greatly enhancing connectivity between the northern and southern banks of the Zijiang River. After 1991, the successive openings of Xiliuwan Bridge and Baimashan Bridge (formerly the Third Bridge) reshaped the cross-river transportation network, optimizing the local street system and improving accessibility within the historical districts. Each phase of planning reform sought to establish a new urban order, resulting in the emergence of new textures, functions, and linkages. Within these evolving structures, core streets which guided by planned functional hierarchies—became focal points for traffic flow concentration. This process reconstructed the multi-scale spatial topological hierarchy, improving circulation efficiency and enhancing everyday mobility convenience for residents in the protection zone.

5.2 Evolution of functional zoning and architectural form within the protection zone

The functional zoning of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone demonstrates a clear progression from single-use dominance to composite diversification. In 1948, land use was concentrated on the north bank of the Zijiang River and primarily residential, with weak commercial and cultural functions. By 1967, despite limited socio-economic growth, residential expansion extended southward across the river, maintaining a mono-functional pattern. In 1990, emerging educational and administrative functions signaled a planned southward restructuring. By 2015, rapid urbanization facilitated functional upgrading: residential–commercial mixed areas emerged near Shimatou and Dongmenkou, commercial land proportion increased, and the Huilongshan Historical Area evolved into a comprehensive service hub. By 2024, urban development entered a quality-enhancement stage, featuring increased educational and industrial land toward talent cultivation and industrial transition, forming a multi-functional, composite spatial system with residential use remaining central.

Architecturally, the urban fabric evolved from dispersed and organically traditional forms toward denser and more structured configurations aligned with urban road systems. In 1990, building distribution remained low-density and concentrated near Shimatou. By 2015, density significantly increased in key southern districts, reflecting spatial consolidation under urban expansion. By 2024, density was moderately regulated, balancing heritage preservation in core historical areas with controlled cultural and tourism-oriented development along the periphery, especially in Huilongshan. Overall, functional restructuring guided changes in building form and density, while architectural transformation reinforced the optimization of spatial functions, collectively driving the protection zone’s transition from a traditional settlement to a modernized, composite urban environment that maintains historical continuity.

5.3 Changes in the protection zone and urban development

The Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone has consistently occupied a core position in Yiyang’s urban development process, demonstrating strong centrality throughout different stages of growth. As a witness to the city’s historical evolution, the protection zone reflects the transformation of Yiyang’s old urban center through five distinct phases spontaneous growth, formative expansion, transitional adjustment, rapid development, and quality-oriented optimization. It continues to serve as the spatial and social nucleus of the city, reinforcing its role as a cultural and social hub. Functioning as a key conduit of cultural inheritance, the protection zone provides substantial spatial support for the diversity and continuity of Yiyang’s urban culture, while strengthening residents’ sense of identity and belonging. As a culturally distinctive “local core”, the protection zone plays an indispensable role in promoting the sustainable and integrated development of Yiyang’s broader urban system, bridging the relationship between heritage conservation and contemporary urban growth.

5.4 Protection and spatial optimization strategies for historical and cultural cities

Ensuring the authenticity of spatial morphology is one of the core objectives in the conservation of historical and cultural cities. This encompasses not only the protection of physical space, but also the revitalization and regeneration of cultural, functional, and historical continuity. Effective conservation thus requires multi-level and multi-scalar approaches to safeguard and extend the historical and cultural values of the city. For medium-sized cities like Yiyang, particularly those whose protection zones contain distinctive local historic districts, conservation efforts should focus on maintaining functional continuity and the authenticity of spatial structure. To achieve this goal, planning and construction within the protection zone should prioritize three key aspects: road network structure, building functions, and overall urban form.

5.4.1 Selectivity and connectivity of road networks

The road system within Yiyang’s Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone forms the skeletal framework of the city, carrying rich historical information and cultural significance. Over the course of urban evolution, these roads developed into a highly selective and integrated network, mirroring the city’s developmental trajectory and serving as carriers of social and cultural activities. The openings of Maliang Bridge (First Bridge), Xiliuwan Bridge, and Baimashan Bridge (Third Bridge) have been crucial in strengthening connectivity across the Zijiang River, integrating the northern and southern banks. In the context of contemporary urban transformation, it is essential to preserve the authentic configuration of key roads such as Pedestrian Street, Wuyi Road, and Zijiang Road. Urban planning should therefore prioritize connectivity within the historical fabric, avoiding large-scale widening or realignment projects that could disrupt historic continuity. Any interventions in core districts or high-selectivity streets should be approached with caution to maintain their historical directionality and spatial relationships. To relieve internal traffic pressure while preserving the historical street network from modern vehicular impacts, external expressways or underground transit systems could be developed. Such a “historic connectivity–centered” strategy allows the road network to accommodate modern transportation demands while maintaining authenticity, ensuring a harmonious coexistence of historical integrity and modern accessibility within Yiyang’s protection zone.

5.4.2 Revitalization and preservation of functional zoning and architecture

In Yiyang’s conservation practice, maintaining functional continuity and ensuring the living transmission of architecture are essential for sustaining vibrancy and safeguarding cultural heritage. Historically, the protection zone evolved around the Zijiang River with a residential core, commerce along the riverfront, and cultural functions interwoven throughout. On the north bank, the Shimatou and Dongmenkou districts served as primary residential hubs while hosting small-scale commerce—shops, groceries, and markets—along Pedestrian Street and Zijiang Road. Scattered temples and folk activity spaces complemented these with spiritual and cultural dimensions, embodying Yiyang’s historical logic of “prospering by the river and flourishing through commerce.” For functional revitalization, regeneration should align with contemporary socioeconomic demands. Historical commercial districts such as Pedestrian Street and Zijiang Road can be reactivated by integrating creative industries, cafés, and boutique retail, preserving their role in modern urban life. Residential areas should retain traditional courtyard-style architecture while upgrading interior infrastructure to meet modern living standards. Architectural preservation requires differentiated strategies. Historical buildings with strong heritage value should undergo meticulous restoration, retaining traditional wooden structures and brick façades. Modern-era buildings compatible with the historic context can be revitalized through façade renewal and adaptive reuse, ensuring that preservation coexists with contemporary functionality.

5.4.3 Protection through public participation and legal-policy mechanisms

A sustainable conservation system relies on both regulatory enforcement and public participation that the synergy between the two forms the foundation of long-term heritage protection. From an institutional perspective, local governments should establish legal frameworks that define the boundaries and core principles of the protection zone. On one hand, dedicated regulations should codify land-use attributes and zoning functions, strictly limiting the intensity and scope of development or renovation to prevent excessive commercial exploitation or inappropriate alterations that may damage historical character. On the other hand, detailed technical standards for building restoration, alley preservation, and waterfront utilization must be developed especially for core districts such as Shimatou and Dongmenkou specifying guidelines for wooden and masonry restoration, and for maintaining the belt-shaped grid street pattern characteristic of Yiyang’s urban heritage. Public engagement is equally vital for revitalizing and enhancing the effectiveness of conservation. Community co-governance mechanisms can involve residents in decision-making through public hearings on building restoration, functional renewal, and land-use changes, ensuring that conservation aligns with local living needs. Educational outreach through exhibitions, workshops, and digital platforms can further raise awareness and foster emotional connections between residents and the historic environment. Moreover, leveraging digital technologies to build virtual archives and interactive heritage platforms can make the evolution of historic spaces more accessible to the public while providing valuable feedback for improving conservation strategies. In essence, the spatial, functional, and participatory protection framework for Yiyang’s Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone emphasizes the integration of authenticity, continuity, and adaptability preserving historical integrity while fostering sustainable urban vitality and contemporary livability.

6 Conclusion

6.1 Research findings

This study employed GIS and space syntax techniques to conduct an in-depth analysis of the morphological evolution of the Yiyang Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone across five key periods that 1948, 1967, 1990, 2015, and 2024. By comparing the morphological transitions of the protection zone at different historical stages, its relative spatial relationship with the city center, and the evolution of building functions, several important conclusions were drawn.

1. The spatial morphology of Yiyang’s Historical and Cultural City Protection Zone has undergone a remarkable transformation, evolving from an initially simple, mono-structured form confined to the north bank of the Zijiang River into a complex, multi-dimensional network extending across both riverbanks. This transition reflects the shift of the road system from a spontaneous and irregular pattern to a more organized, interconnected, and hierarchical structure. Particularly since the 1990s, with rapid socioeconomic development and urban expansion, the road network of the protection zone has been significantly extended and optimized, forming a system characterized by high selectivity, integration, and connectivity.