- 1Xi’an Branch, China Coal Research Institute, Beijing, China

- 2Drilling Technology and Equipment Division, CCTEG Xi’an Research Institute, Xi’an, China

Soft coal seams represent a common geological feature in coal and gas outburst mines. They generate a substantial amount of coal debris during gas extraction drilling, which easily causes hole blockage and leads to drilling hazards such as pipe sticking, pipe jamming, and borehole collapse. This study draws inspiration from the burrowing and soil discharge mechanisms of earthworms and proposes a novel composite drilling process that combines “impact vibration + crawling extrusion” for soft coal seams to mitigate these risks and enhance drilling efficiency. Based on discrete element simulation, the effects of drill bit structure, coal seam pressure, and coal seam condition on drilling performance are investigated. The results show that the concave cone bionic bit exhibits the best cutting performance at a buried depth of 400–600 m, with a drilling speed approximately 18% higher than that of other bit structures. The coal seam pressure demonstrates a negative correlation with drilling speed, and the bit displacement at 600 m is 32% lower than that at 400 m. In addition, the drilling efficiency in loose coal seams is considerably higher than in cohesive coal seams, with a displacement difference of 0.025 m/cycle. This study confirms that the proposed high-frequency impact extrusion bionic drilling technology can effectively enhance drilling efficiency and safety in soft coal seams, providing a theoretical basis for the design and optimization of related drilling equipment.

1 Introduction

Coal and gas outbursts are one of the major dynamic disasters in coal mine production and pose a serious threat to global coal mining, among which “soft and low permeability” remains the common and core geological challenge encountered by most coal and gas outburst mines (Zhang and Wang, 2023; Zhang et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2023). Soft and low-permeability coal seams have characteristics of low firmness coefficients and weak mechanical strength (Zhang et al., 2020). During drilling in such seams, excessive coal debris is produced, which tends to accumulate in the borehole and cause downhole incidents such as pipe jamming, bit failure, and even gas blowouts. These problems directly compromise the attainable depth and range of gas drainage, reducing its overall efficiency (Keim et al., 2011; Karacan et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2011; Kedzior, 2009). A primary challenge in drilling soft coal seams lies in inadequate cuttings removal. Specifically, when the rate of cuttings discharge falls behind the rate of cuttings generation, coal debris accumulates in the annular space between the drill pipe and the borehole wall, eventually leading to pipe sticking and jamming. Since the risk of pipe sticking decreases significantly when the rate of cuttings removal equals or surpasses the rate of cuttings generation, a fundamental solution to the challenges of drilling in soft coal seams involves enhancing the efficiency of cuttings transport from the borehole.

Given the persistent issue of inefficient coal debris discharge in soft coal seams, substantial research efforts have been dedicated to improving downhole cleaning efficiency, particularly through innovations in drilling tool design and process optimization. Regarding drilling tool structures, Tang Ping, Zhang Yu, and others developed spiral-structured drill pipes, including L-shaped, triangular-grooved, and rib-type designs, to enhance coal debris discharge efficiency and capacity. However, in deep or steeply inclined boreholes, these pipes still demonstrate insufficient debris removal capability, resulting in debris accumulation. In addition, the frictional resistance between the drill pipes and the borehole wall remains high, the hole protection effect is limited, and the risk of hole collapse persists (Tang, 2020; Zhang, 2023; Jiang, 2019). Concerning the coal debris discharge process, the medium-low-pressure air slag discharge method has been widely utilized. This technique employs compressed air as the power medium and provides advantages such as system simplicity and low cost. However, under complex geological conditions, it continues to face challenges due to limited debris-carrying capacity caused by inadequate air pressure (Zhang et al., 2017). In foam drilling technology, a stable foam generated by mixing a foaming agent with water is injected into the borehole. This foam encapsulates coal debris and carries it out of the hole. With a cuttings-carrying capacity approximately 7–8 times that of clean water, this process effectively removes debris from the bottom of the hole and minimizes the risk of drill pipe sticking (Guo and Galambor, 2002). In addition, the dual-pipe dual-action directional air drilling technology has also demonstrated its advantages. It enables continuous and efficient debris discharge while reducing the risk of pipe blockage by employing an independently rotating inner and outer pipe design. This method is particularly suitable for soft coal seams with steep inclinations or complex geological structures (Saxena et al., 2017; Song, 2024). Although the mentioned technologies provide distinct theoretical advantages, their practical application continues to face challenges, including difficulties in maintaining optimal foam performance, strong dependency on water quality, complex supporting equipment and processes, and high initial investment costs.

When conventional methods in geotechnical engineering and kinematics fail to achieve significant breakthroughs, nature often provides sophisticated and efficient solutions (Tan et al., 2025; Velivela and Zhao, 2022; Kindlein and Guanabara, 2005). Studies have demonstrated that animals such as moles, ants, and earthworms possess remarkable excavation capabilities. For instance, a 10 cm long mole can dig a 4.5 m long tunnel within 1.5 h (Lee et al., 2019); limbless earthworms can construct burrows up to 2 m in length (Liem et al., 2024; Kandh et al., 2021); and ants measuring only 2 cm in length can excavate tunnel systems extending over 8 m (Prasath et al., 2022). In recent years, bionic robotic technology inspired by animal excavation mechanisms has advanced substantially. Researchers around the world have developed specialized systems such as mole-inspired digging robots and arc-shaped mud-penetrating robots, which have been successfully applied in areas including space sampling and underwater operations (Liang and Ren, 2016; Yi et al., 2007). Regarding specific bionic mechanisms, the Atlantic razor clam (Ensis directus) employs a highly efficient “dual-anchor strategy” for burrowing, utilizing its robust muscular foot and expandable articulated shell. The core of this locomotion mechanism involves a cyclic process in which the expanded shell serves as an anchor, enabling the foot to penetrate the soil ahead and establish a new anchoring point (Zhang L. et al., 2024). During this process, shell expansion relieves stress in the soil beneath the foot tip, facilitating subsequent penetration. Foot extension redistributes mechanical forces, weakening the previous shell anchor and raising a continuous propulsion cycle. Mechanically, this dual-anchor strategy can be represented as a composite motion model involving the periodic expansion of a cylinder followed by the penetration of a cone (Huang and Tao, 2020; Martinez et al., 2020). Inspired by this principle, Tao et al. developed a self-drilling robot driven by a single-segment fiber-reinforced silicone tube. The robot achieved autonomous drilling in sandy soil by controlling inflation and deflation to imitate biological periodic motion (Tao et al., 2020). Earthworms accomplish peristaltic burrowing through the coordinated interaction between their hydrostatic skeleton and muscles. The hydrostatic skeleton operates as a fluid-supported system in which internal liquid pressure preserves the structural integrity of the surrounding muscular wall. Utilizing the incompressibility of the internal fluid, contraction of muscles in one direction causes the body segment to elongate perpendicularly. When longitudinal muscles contract axially, the segment thickens and shortens to form an anchor; when circular muscles contract radially, the segment narrows and elongates to penetrate the soil. A retrograde peristaltic wave then propagates from the anterior to the posterior, driving the body forward through a continuous “anchor-penetrate-reanchor” cycle (Calderón et al., 2016). Based on this principle, Isaka developed a drilling robot for submarine exploration that successfully performed curved drilling operations with a turning radius of 1,670 mm and a depth of 613 mm (Isaka et al., 2019). Ma et al. proposed a self-excavating geological probe equipped with a soft pneumatic bladder positioned behind its rigid conical head. The penetration resistance of the conical head can be effectively regulated by cyclically applying positive and negative pressure to control its expansion and contraction (Ma et al., 2020). The Niiyama research team developed an earthworm-inspired soft drilling robot featuring an artificial hydrostatic skeleton, which achieved 5 mm of advancement in soil under specific peristaltic patterns (Niiyama et al., 2022). In addition, moles and crabs employ a compound excavation strategy involving chiseling, grabbing, and propulsion through the coordinated motion of their limbs and mouthparts. Various mole species exhibit distinct excavation mechanisms: those possessing chisel-shaped incisors (Fukomys micklemi, the fast-digging mole) employ an incisor-based technique, raising the lower incisors to grasp soil while the upper incisors remain anchored, followed by a rapid downward rotation of the head to dislodge the material (Van Wassenbergh et al., 2017). In contrast, species that rely primarily on forelimbs (the tunnel-digging mole) perform a two-phase digging cycle: initially using rapid forelimb movements to generate and collect loose particles beneath the abdomen, followed by powerful hindlimb kicks to discharge the debris (Kim et al., 2018). Drawing inspiration from the digging mechanisms and the sophisticated humeral structure of moles, Lee et al. developed a drilling system integrated with retractable blades and a forelimb-inspired configuration, successfully constructing a vertical tunnel with a diameter of approximately 202 mm (Lee et al., 2020).

Although existing bionic excavation research has achieved remarkable progress in homogeneous sandy soil, underwater sediments, and other relatively stable medium environments with uniform structures, there remains a lack of effective technical responses to complex working conditions characterized by high stress, strong adhesion, and easy crushing in soft coal seams. Oriented toward the practical requirements of safe and efficient drilling in coal mines, this study draws inspiration from the core mechanism of “anchor-propulsion” dynamic interaction observed in earthworms and other organisms. Moving beyond mere morphological imitation, it innovatively proposes a composite hole-forming process that integrates “impact vibration and crawling extrusion”. This process deconstructs the continuous peristaltic wave of biological motion into a discrete action sequence combining high-frequency impact and quasi-static extrusion. It retains the adaptive advantages of bionic mechanisms in complex environments while aligning with the engineering constraints of coal mine hydraulic drilling systems, providing a new technical pathway for safe and efficient drilling in soft coal seams.

Compared to the traditional “drill rig-drill pipe-drill bit” technology used for drilling in soft coal seams, the technical method proposed in this study demonstrates the following significant advantages: (1) simplified system structure and efficient energy transfer. It resolves issues of high energy loss and low system efficiency caused by multi-stage transmission in traditional drilling methods by eliminating the need for complex equipment combinations such as drill rigs and drill pipes. (2) Reduced borehole wall disturbance and enhanced hole stability. Through optimized drilling mechanisms, it significantly minimizes mechanical disturbance to the borehole wall caused by drilling tools, effectively preventing downhole accidents such as hole collapse and bit burial that are common in conventional methods, improving the reliability and safety of the drilling process.

2 Analysis of the bionic burrowing mechanism and function simplification

The earthworm, a typical soil organism known as nature’s “cultivator,” exhibits extraordinary burrowing and soil-discharging capabilities. Figure 1 indicates that research data indicate that an earthworm measuring only 15 mm in length can construct a tunnel up to 2 m long (Kou et al., 2025; Trivedi et al., 2008; Kier, 2012). This study adopts the earthworm as a bionic morphological prototype, abstracting its unique soil movement abilities, analyzing its physiological structure and movement mechanisms during burrowing and soil discharge, and applying these findings to hole drilling in soft coal seams.

The crawling and locomotion of earthworms involve several key organs, including the prostomium, setae, circular muscles, and longitudinal muscles. The setae, which serve as locomotive organs attached to the body wall, consist of the setae themselves, setal sacs, and setal muscles. The setal muscles include protractor and retractor muscles that contract alternately to extend or retract the setae into the body wall. This mechanism enables the earthworm to anchor itself in the tunnel or crawl sinuously across surfaces. During crawling, when the longitudinal muscles of a body segment contract and the circular muscles relax, the segment thickens and shortens while the setae extend backward to grip the surrounding soil. Simultaneously, in the preceding segment, the circular muscles contract and the longitudinal muscles relax, causing that segment to thin and elongate, retract its setae, and detach from the soil. The setae of the subsequent segment then provide support and propulsion, moving the body forward. This reciprocal action between adjacent segments enables continuous crawling motion.

This study analyzes the anatomical structure of the earthworm to derive its movement mechanism and crawling function model. Figure 2 reveals that the earthworm employs its prostomium to excavate soil and construct tunnels, utilizing circular muscles for anchoring, longitudinal muscles for propulsion, and setae to facilitate locomotion. Building on this mechanism, the research proposes a bionic drilling system in which a specialized drill bit replaces the prostomium, and a combined “impact vibration + crawling extrusion” power system substitutes for the synergistic action of the circular and longitudinal muscles. This bio-inspired approach enables efficient drilling in soft coal seams.

3 Bionic design of impact extrusion drill bits

The structural design of the drill bit plays a critical role in determining the efficiency of impact extrusion hole formation in soft coal seams. An optimized drill bit not only enhances coal fragmentation efficiency and reduces drilling resistance but also facilitates the smooth flow of coal powder, ensuring rapid removal of fragmented coal dust to the periphery of the borehole.

In the design of impact extrusion drill bits, experimental observations and previous studies have revealed that the non-smooth surface morphologies of typical soil-dwelling organisms, such as dung beetles, mole crickets, and earthworms, can effectively reduce adhesive wear and friction coefficients. These bio-inspired surface structures transform sliding actions (such as scraping, cutting, and chiseling) into rolling motion during friction, significantly minimizing surface damage and lowering crawling resistance. In recent years, the application of bionic engineering to drill pipes, plowshares, and excavator buckets has demonstrated substantial improvements in wear resistance and overall performance. Building on this concept, the present study transfers the wear-resistant features of biological structures into an engineered design, focusing on developing a bionic non-smooth morphology for the impact cone surface of the drill bit. The pit morphology on the dung beetle’s surface decreases the contact area with soil, minimizing soil adhesion. In addition, air trapped within these pits creates localized negative pressure that counteracts a portion of the contact pressure and contributes to the reduction of overall resistance (Cui, 2021). The earthworm’s body surface consists of multiple striped segments that flexibly twist and contract during soil penetration. This motion generates a non-smooth wavy profile, effectively decreasing soil contact area and reducing frictional resistance (Shi et al., 2005; Liu, 2009). The lizard, which inhabits desert environments, has evolved a multi-layered skin structure with tightly interlocked diamond-shaped scales arranged in an overlapping pattern, which effectively reduces surface contact with the ground and minimizes frictional resistance (Ren and Liang, 2012). Figure 3 illustrates the body surface structures of the dung beetle, earthworm, and lizard.

Figure 3. Body surface structure of bionic biological prototype: (a) Dung beetle pit body; (b) Earthworm segment body surface; (c) Lizard scale body surface.

Drill bits were designed with three distinct bionic structural forms: a non-continuous stepped shape, a pitted conical shape, and a striped conical shape based on the biological prototypes of the lizard, dung beetle, and earthworm, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Bionic drill bits of different structures: (a) Non-continuous stepped shape; (b) Pit conical shape; (c) Striped conical shape.

4 Rigid body dynamics-coupled analysis of particle dynamics

4.1 Establishment of a discrete element model

The coal body medium is modeled using the discrete element method as a system composed of numerous finite discrete rigid elements that interact through different types of contact models. These particles can transmit both normal and shear stress while also transferring torque, enabling a realistic simulation of the mechanical responses and failure processes of coal rock under varying loading conditions.

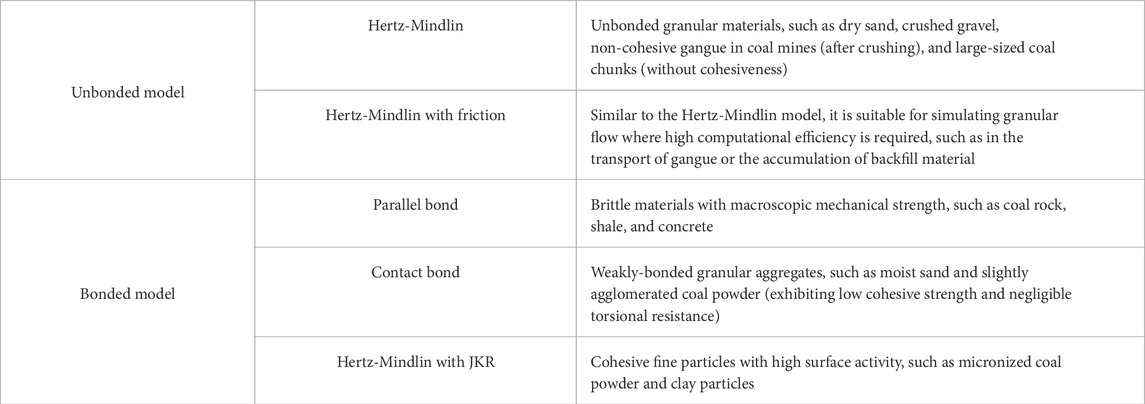

The physical characteristics of coal seams differ considerably across regions. This study concentrates on soft coal seams, which exhibit distinct interparticle voids and dynamically varying adhesion properties. The selection of a discrete element contact model depends on its compatibility with both the mechanical properties of the granular material (such as bonded or unbonded and brittle or plastic behavior) and the specific requirements of the research scenario. Table 1 lists commonly used discrete element contact models and their respective application scopes.

In coal mining contexts, the choice of simulation models primarily emphasizes the typical behaviors of materials such as coal rock, gangue, and coal powder, including brittle failure, bulk flow, and fine particle agglomeration. The bionic drill bit analyzed in this study is primarily designed for soft coal seams. After fragmentation, the resulting coal blocks and gangue typically exhibit particle sizes larger than 5 mm, show no significant interparticle bonding, and transmit loads mainly through friction and collision. The Hertz-Mindlin model accounts solely for elastic contact and frictional effects, making it suitable for simulating flow behaviors such as particle rolling, sliding, and accumulation in these materials. In contrast, for coal powder, smaller particle sizes produce larger specific surface areas, resulting in more pronounced van der Waals forces due to surface energy, which readily raise agglomerate formation. The Hertz-Mindlin with JKR model, which computes cohesive forces based on surface energy theory, effectively replicates the dynamic process of coal powder “dispersing-agglomerating-redispersing.” Therefore, based on parameters derived from existing studies, this study employs both the Hertz-Mindlin (Zhang J. X. et al., 2024; Aleshin and Van Den Abeele, 2012) and Hertz-Mindlin with JKR (Xia et al., 2019; Zakeri and Faraji, 2023) contact models to simulate loosely structured coal with weak interparticle cohesion and densely agglomerated coal with strong cohesion, respectively.

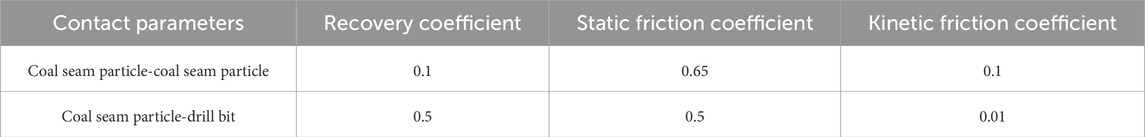

The contact parameters for coal seam particles under different material combinations are presented in Table 2 (Yang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022). Considering the significant influence of particle size on the computational efficiency of discrete element simulations and referring to relevant research findings on particle size effects by domestic and international scholars (Wu et al., 2025; Coetzee, 2017), this study sets the coal seam particle radius to 3 mm.

The material parameters of the bionic drill bit and the coal seam medium are shown in Table 3 (Wu et al., 2024).

A cubic coal seam model measuring 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.6 m was established, consisting of a total of 120,000 particles. Simulation models were developed for burial depths of 400, 500, and 600 m, based on the corresponding relationship between coal seam burial depth and confining pressure of the coal body, to analyze the impact of the extrusion effect of the drill bit on coal seams at varying burial depths, as shown in Figure 5.

4.2 Kinematic analysis of the drill bit

A kinematic simulation analysis of the impact extrusion drilling process in soft coal seams was performed, with the extrusion load set at 45 kg, the frequency of the impact load at 350 times/min, and the impact energy at 150 J. Both loads were superimposed to form the power load for robotic drilling, with the combined load illustrated in Figure 6.

4.3 Coupled simulation analysis

The impact-extrusion composite drilling process in soft coal seams was numerically simulated using a coupled dynamic simulation approach. The bidirectional coupling workflow is depicted in Figure 7. During each simulation time step, the kinematic simulation transfers the displacement and orientation data of the drill bit to the discrete element simulation. Based on this geometric configuration, the discrete element simulation calculates the interaction loads between the coal seam particles and the drill bit and feeds the resultant force and torque back to the kinematic simulation. Using the received load data, system constraints, and external excitation, the kinematic simulation updates the dynamic state of the drill bit and outputs key response parameters, including displacement, force, and drilling speed, thus completing the solution for the current time step. Through iterative cyclic data exchange, bidirectional co-simulation of the mechanical-granular system dynamics is achieved.

After completing the basic bidirectional coupling model between the kinematic and discrete element simulations, three key configuration files are required to establish the co-simulation environment. The ADM file defines the system topology and generalized force elements located at the center of mass of each component, serving as the interface to receive particle loads from the discrete element simulation. The ACF file specifies the master simulation step size and total duration for the kinematic simulation. The cosim file manages the mapping between component names and generalized force element identifiers, ensuring a one-to-one correspondence between particle loads and geometric bodies.

Once configured, the system operates in a client-server communication mode. The kinematic simulation functions as the master, advancing the multibody dynamics solution based on the defined step size and transmitting the position, orientation, and velocity information of each component’s center of mass to the discrete element simulation in real time via the TCP/IP protocol. After completing the particle-structure interaction calculations within its sub-cycles, the discrete element simulation returns the resultant force and moment on contact surfaces in 64-bit double-precision format to the kinematic simulation, where they are applied to the corresponding generalized force elements. The discrete element simulation performs linear interpolation on the motion trajectories provided by the kinematic simulation to maintain time synchronization.

5 Analysis of drill bit motion characteristics and coal seam stress

A further analysis was conducted on the motion characteristics of the drill bit and the stress intensity generated within the coal seam under different drilling conditions, considering that the drilling process is influenced by the drill bit structure, coal seam confining pressure, and seam conditions.

5.1 Influence of drill bit structure on the drilling process

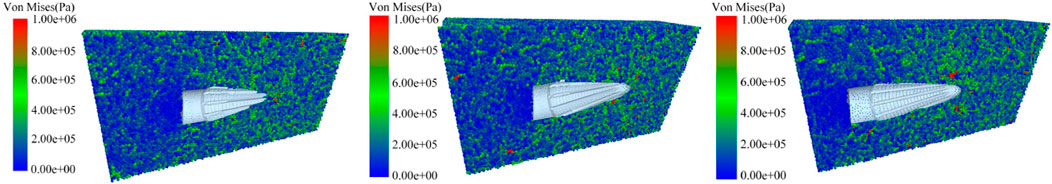

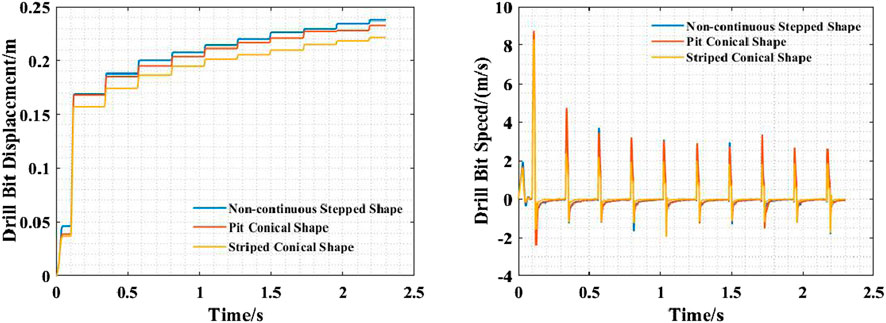

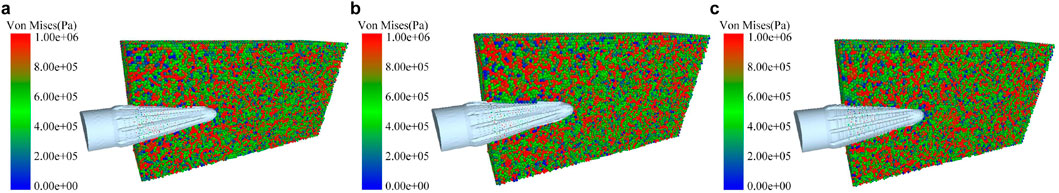

Simulations of the impact-extrusion drilling process were performed for non-continuous stepped, pit-conical, and striped-conical drill bits at coal seam burial depths of 400, 500, and 600 m, respectively. The analysis focused on variations in drill bit displacement and speed during drilling, as well as on the stress intensity induced in the coal seam. The simulation results are presented in Figures 8–13.

Figure 8. Change of displacement and speed of drill bits with different structures at a depth of 400 m.

Figure 9. Coal seam stress generated by drill bits with different structures at a depth of 400 m: (a) Non-continuous stepped shape; (b) Pit conical shape; (c) Striped conical shape.

Figure 10. Change of displacement and speed of drill bits with different structures at a depth of 500 m.

Figure 11. Coal seam stress generated by drill bits with different structures at a depth of 500 m: (a) Non-continuous stepped shape; (b) Pit conical shape; (c) Striped conical shape.

Figure 12. Change of displacement and speed of drill bits with different structures at a depth of 600 m.

Figure 13. Coal seam stress generated by drill bits with different structures at a depth of 600 m: (a) Non-continuous stepped shape; (b) Pit conical shape; (c) Striped conical shape.

Figures 8, 10, 12 show that all three drill bit types successfully achieved impact extrusion failure of the coal seam while accounting for particle adhesion effects. The drilling displacement and speed exhibited distinct periodicity, indicating that the impact load played a substantially more dominant role than the crawling extrusion load. When the impact load was applied, the drill bit rapidly penetrated the stratum, and the drilling speed decreased as the drill bit gradually advanced. The forward displacement changed rapidly before the conical surface of the drill bit fully penetrated the coal seam, and as the drill bit penetrated further, the displacement change gradually decreased. Under the three different coal seam burial depth conditions, the striped-conical drill bit experienced the greatest drilling resistance and the slowest drilling speed. In contrast, the pit-conical drill bit demonstrated superior penetration capability, with a displacement approximately 32% greater than that of the striped-conical drill bit, indicating that the pit, non-smooth structure, reduced drilling friction resistance and facilitated the movement of coal slag around the drill hole.

Figures 9, 11, 13 indicate that as the burial depth of the coal seam increases, the drilling distance of the drill bit becomes shorter, resulting in the confining pressure of the coal seam exerting a significant influence on the motion characteristics of the drill bit. Different drill bit structures generate varying stress distributions within the coal seam. Taking a burial depth of 400 m as an example, all three types of drill bits, the non-continuous stepped drill bit, the pit conical drill bit, and the striped conical drill bit, produce a maximum stress of 247 MPa in the coal seam. However, the coal seam particles surrounding the non-continuous stepped and striped conical drill bits experience higher stress levels, while those around the pit conical drill bit show noticeably lower stress. This indicates that the pit conical drill bit encounters less resistance from the coal seam during drilling, explaining its superior drilling speed.

5.2 Influence of coal seam pressure on the drilling process

The burial depth of the coal seam is a crucial factor influencing the ground stress in underground coal mines, as different burial depths result in distinct vertical and horizontal stresses. Generally, the vertical stress within coal seams increases proportionally with burial depth. During impact extrusion drilling in soft coal seams, the drill bit must deliver sufficient impact extrusion load to achieve fragmentation and deformation of the coal body while also possessing adequate energy to overcome the stratum stress to extrude the fragmented coal dust into surrounding pores. This study investigates three burial depths, 400, 500, and 600 m, calculates the corresponding vertical stresses and pressure measurement coefficients, and analyzes the effect of coal seam pressure on variations in drilling speed and displacement.

Figure 14 illustrates an analysis of the drilling performance using a pit conical drill bit under varying coal seam pressure conditions. It demonstrates that as the coal seam pressure gradually increases, the drilling speed of the drill bit decreases. For each applied load, with every additional 100 m of burial depth, the drill bit displacement decreases by approximately 10%–15%. At a burial depth of 600 m, the drilling displacement of the drill bit reaches its minimum. Figure 15 shows that the conical drill bit generates a maximum stress of 247 MPa in coal seams at burial depths of 400, 500, and 600 m. However, as the burial depth increases, the area subjected to significant stress within the coal seam particles expands notably. This phenomenon occurs because greater burial depth increases the reservoir pressure on the coal seam, resulting in higher resistance for the drill bit as it extrudes coal powder into the surrounding borehole, reducing the drilling speed. This finding indicates that under specific load conditions, the “impact vibration + crawling extrusion” composite hole-forming process is suitable for coal seams with limited reservoir pressure; to broaden the applicability of this process, both the impact and extrusion loads must be increased.

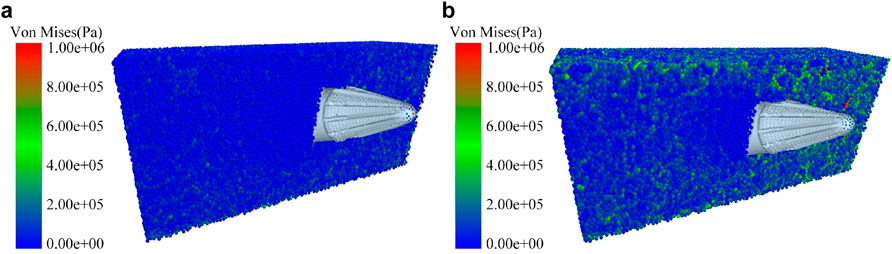

Figure 15. Stress in coal seams at different burial depths: (a) Burial depth of 400 m; (b) Burial depth of 500 m; (c) Burial depth of 600 m.

5.3 Study on the influence of coal seam state on the drilling process

Under the condition of coal seams at a burial depth of 400 m, the drilling process of the pit conical drill bit in loose coal seams and adhering coal seams was simulated. Figure 16 demonstrates that at the same load cycle, the drilling speed in loose coal seams increased by 28% compared to that in adhering coal seams due to higher porosity. In adhering to coal seams, the displacement of the drill bit was smaller and the speed slower, with an average displacement difference of approximately 0.025 m. Figure 17 reveals that the stress generated by the conical drill bit on adhering coal seam particles is significantly higher than that on loose coal seams. This indicates that the coal seam state markedly influences the extrusion drilling speed of the bionic automatic drilling robot. In loose coal seams, the larger gaps between coal particles allow easier deformation under drill bit extrusion. In contrast, when drilling in adhering coal seams, the drill bit must first overcome the adhesive forces of the coal blocks, fracturing them before extruding the resulting coal slag against the surrounding coal wall to form the borehole.

Figure 17. Stress in coal seams under different coal seam states: (a) Loose coal seam; (b) Adhering coal seam.

The above analysis demonstrates that the coal seam state substantially affects the extrusion drilling process. The looser the coal seam and the lower the coal’s firmness coefficient, the easier it is for the coal to be crushed and extruded along the coal wall of the borehole during drilling. Therefore, this process is suitable for specific coal seam states and geological conditions in practical drilling operations.

5.4 Static analysis of the drill bit structure

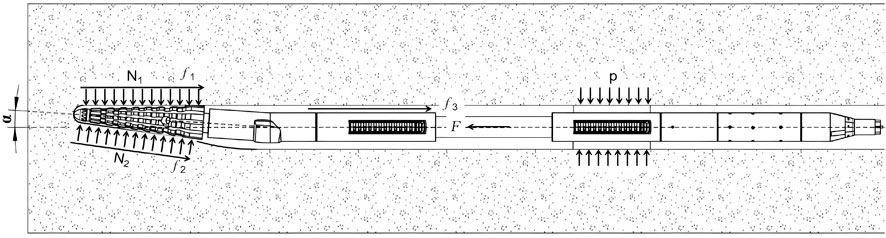

During the impact extrusion drilling process, the drill bit transfers load to the coal seam, and its mechanical strength and bearing capacity play a crucial role in determining the drilling performance. Taking the working condition of adhesive coal seam with buried depth of 600 m as an example, a force analysis was performed on the pit conical drill bit, and a mechanical model for the hole formation of the drill bit in coal powder was developed, as illustrated in Figure 18.

Assuming the frictional resistance on the drill bit sidewall is f, the lateral pressure exerted by the coal powder on the drill bit is N, and the kinetic energy obtained by the drill bit is E0, when the impact energy of the drill bit exceeds the work done by the coal powder resistance, the forward movement stroke of the drill bit is ΔL. Equation 1 shows the equation of extrusion and crushing energy:

where ρ is the loss coefficient, it refers to the ratio of useful energy converted into rock fragmentation and overcoming frictional resistance, to the total kinetic energy obtained by the drill bit. This coefficient is typically influenced by factors such as the accumulation of residual coal powder at the front end of the bit. If the energy consumed by residual coal powder is disregarded, the coefficient can be taken as 1; ΔW1 is the elastic deformation energy of the coal body; ΔW2 is the plastic deformation energy of the coal body; Nf · ΔL is the work done by the frictional resistance on the drill bit sidewall.

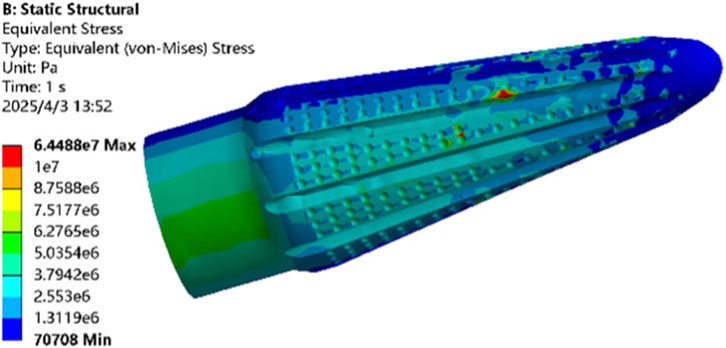

Under the conditions of a 600 m coal seam burial depth, 10.5 MPa confining pressure, and a 0.7 coal seam friction coefficient, a finite element simulation model for drill bit extrusion and drilling was established. The forces acting on the drill bit were calculated based on the energy distribution during coal extrusion and fragmentation. Figures 19, 20 indicate that the maximum resistance exerted by coal seam particles on the drill bit was applied as a surface load in the simulation. The maximum load on the drill bit from a single coal seam particle was 81 N, and the maximum stress on the drill bit was 64 MPa. The point of maximum stress was located at the chip space on the side of the drill bit. This occurred because, during the drilling process, the sidewall of the drill bit not only contributes to coal body crushing but also needs to extrude the crushed coal powder to the periphery of the drill hole to form a compaction zone, resulting in a significant reaction force from the coal powder on the sidewall. The front end of the drill bit primarily functions to crush the coal powder. During the drilling process, since the front end of the drill bit first contacts the coal powder, which has not yet undergone significant extrusion deformation, the force required to extrude the coal powder outward is relatively small. Therefore, the force on the front end of the drill bit remains comparatively low.

The material used for the impact drill bit is low-alloy steel Q345, with a yield strength of 345 MPa. Considering the impact loads encountered during the drilling process, a design safety factor of 2 was adopted for the drill bit, resulting in an allowable stress of 172.5 MPa, which is significantly greater than the maximum stress experienced by the drill bit. Therefore, under extreme working conditions, the strength of the drill bit satisfies the operational requirements of the drilling process.

6 Drilling test

6.1 Test conditions and methods

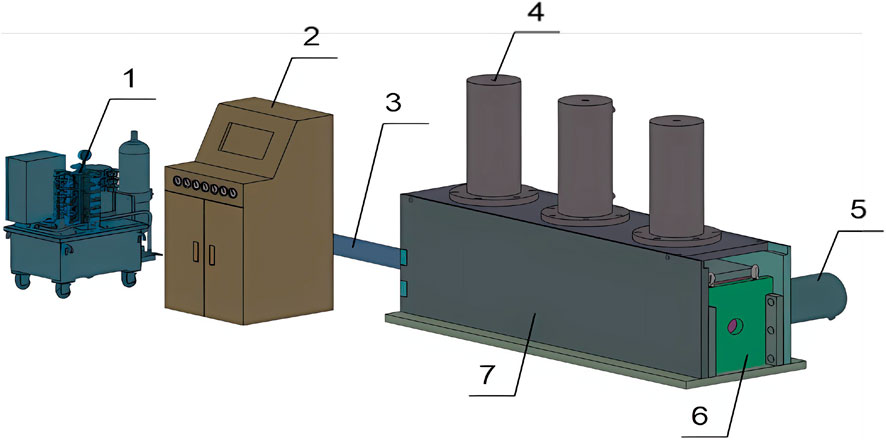

The drilling test bench comprises a hydraulic pump station, control console, discharge cylinder, top compression cylinder, side compression cylinder, and experimental chamber, among other components. It provides functions such as hydraulic pressure control and drilling monitoring, as shown in Figure 21. Specifically, three sets of 200 t compression cylinders are installed at the top and sides of the experimental chamber to apply different confining pressure loads, simulating drilling speeds under varying confining pressure conditions. All cylinder operations are integrated into the control console. Pressure sensors are installed on the top and side walls of the experimental chamber to monitor pressure variations in the coal sample in real time. A discharge cylinder is positioned at the rear to facilitate the rapid loading and unloading of coal samples. The experimental chamber measures 500 × 500 × 2000 mm and is filled with loose coal samples. During testing, the drilling equipment is supplied with a driving air pressure of 0.9 MPa, and drilling tests are performed both without confining pressure and under a 2 MPa confining pressure.

Figure 21. Drilling test bench. 1-hydraulic pump station, 2-control console, 3-discharge cylinder, 4-top compression cylinder, 5-side compression cylinder, 6-unloading bin door, 7-experimental chamber.

The bionic drilling mechanism is illustrated in Figure 22, and its core function is achieved through the coordination of the impact and crawling mechanisms. The impact mechanism, driven by a hydraulic system, generates high-frequency impulsive loads that are transmitted to the drill bit in the form of stress waves, effectively fracturing the coal-rock mass. The crawling mechanism, powered by hydraulic cylinders, provides a stable axial thrust, producing a continuous extrusion load during the drilling process. The actual drilling test photograph is shown in Figure 23.

6.2 Test results

The real-time drilling speed of the bionic drill bit was measured using displacement sensors, and the collected data were processed through Gaussian filtering to minimize fluctuations. During testing, the variations in drilling displacement were monitored in real time, as illustrated in Figure 24.

Figure 24 demonstrates that the drill bit successfully penetrates under both working conditions. In the initial stage, the drilling speed is relatively high; however, as the drill bit gradually advances deeper into the formation, the speed stabilizes, reaching a maximum of 0.125 m/s. The confining pressure load significantly influences the composite impact-extrusion drilling process. When the confining pressure load is 2 MPa, the drilling speed decreases by 46%, indicating that the confining pressure in the coal seam exerts a substantial effect on the drilling operation.

7 Discussion

This study presents a novel “impact vibration + crawling extrusion” composite hole-forming process for drilling in soft coal seams, inspired by the bionic principles of earthworm locomotion. The feasibility of the proposed process was verified through coupled discrete element-multibody dynamics simulations, which revealed that impact loads effectively fragment the coal body, while crawling extrusion loads facilitate the removal of cuttings. The synergistic interaction between these loading modes substantially reduces the accumulation of coal slag in the borehole and lowers the risk of downhole incidents. The principal conclusions of this study are summarized as follows: (1) Three bionic drill bits were designed: non-continuous stepped, pit-conical, and striped-conical. Among them, the pit-conical drill bit effectively minimizes frictional resistance and coal chip adhesion, exhibiting superior drilling performance. It achieves a 15%–20% higher drilling speed than conventional drill bits and maintains stable drilling efficiency even at a burial depth of 600 m. (2) As the coal seam burial depth increases, the extrusion resistance on the drill bit gradually rises. Simulation results indicate that for every 100 m increase in burial depth, the drilling displacement declines by approximately 10%–15%. It is essential to dynamically adjust the load frequency and impact energy to sustain efficient drilling performance. (3) Under identical loading conditions, the average drilling speed in loose coal seams is 28% higher than that in adhesive coal seams, demonstrating the strong adaptability of this impact-extrusion process to various coal seam conditions.

This study comprehensively examined the “impact vibration + crawling extrusion” composite hole-forming process in soft coal seams. The feasibility was systematically confirmed through a combined approach involving discrete element-multibody dynamics coupled simulation and field drilling tests. The results show that within this process, the impact load primarily fractures the coal mass, and its high-frequency action effectively overcomes coal strength. The crawling extrusion load advances in a quasi-static manner, pushing the fragmented coal cuttings toward the borehole wall. The interaction between these two mechanisms establishes an efficient hole-forming principle characterized by “dynamic fragmentation and quasi-static transport,” which significantly alleviates the issue of coal debris accumulation commonly observed in traditional drilling. Field tests further verified that this technique enables drilling in soft coal seams without the need for conventional drilling rigs and pipe systems, providing a novel technological pathway for efficient drilling in such challenging environments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. DT: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. ZC: Data curation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China “Intelligent Stress Sensing and Robust Control for Pressure Relief Drilling Processes in Coal and Rock Dynamic Hazard Prevention”, Fund No. 52474192, and Key R&D Program of Shaanxi Province “Research on Active Anti-Dropping Technology for Drill Pipes Based on Bionic Bone-Tendon Characteristics”, Fund No. 2024GX-YBXM-482.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aleshin, V., and Van Den Abeele, K. (2012). Hertz–mindlin problem for arbitrary oblique 2D loading: general solution by memory diagrams. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 60, 14–36. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2011.10.003

Calderón, A. A., Ugalde, J. C., Zagal, J. C., and Pérez-Arancibia, N. O. (2016). “Design, fabrication and control of a multi-material-multi-actuator soft robot inspired by burrowing worms,” in 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Qingdao, China. doi:10.1109/ROBIO.2016.7866293

Cheng, Y. P., Wang, L., and Zhang, X. l. (2011). Environment alimpact of coal mine methane emissions and responding strategiesin China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 5, 157–166. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2010.07.007

Coetzee, C. (2017). Review:calibration of the discrete element method. Powder Technol. 310, 104–142. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2017.01.015

Cui, Y. Z. (2021). Research on bionic surface wear and fatigue resistance of ball end milling. Harbin, China: Harbin University of Science and Technology. Ph.D. Thesis.

Guo, B. Y., and Galambor, A. (2002). Gas volume requirements for underbalanced drilling: deviated holes. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Pennwell Corp..

Huang, S., and Tao, J. (2020). Modeling clam-inspired burrowing in dry sand using cavity expansion theory and DEM. Acta Geotech. 15, 2305–2326. doi:10.1007/s11440-020-00918-8

Isaka, K., Tsumura, K., Watanabe, T., Toyama, W., Sugesawa, M., Yamada, Y., et al. (2019). Development of underwater drilling robot based on earthworm locomotion. IEEE Access 7, 103127–103141. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2930994

Jiang, Z. G. (2019). Research and application of rational rod for soft coal seam with outburst danger. China Energy Environ. Prot. 41, 135–138. doi:10.19389/j.cnki.1003-0506.2019.04.030

Kandhari, A., Wang, Y. F., Chiel, H. J., Quinn, R. D., and Daltorio, K. A. (2021). An analysis of peristaltic locomotion for maximizing velocity or minimizing cost of transport of earthworm-like robots. Soft Robot. 8, 485–505. doi:10.1089/soro.2020.0021

Karacan, C. Ö., Diamond, W. P., and Schatzel, S. J. (2007). Numerical analysis of the influence of in-seamhorizontal methane drainage boreholes on longwall face emission rates. Int. J. Coal Geol. 72, 15–32. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2006.12.007

Kedzior, S. (2009). Accumulation of coal-bed methane in the south-west part of the upper silesian coal basin (southern Poland). Int. J. Coal Geol. 80, 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2009.08.003

Keim, A. S., Luxbacher, K. D., and Karmis, M. (2011). A numericalstudy on optimization of multilateral horizontal wellbore patternsfor coalbed methane production in southern Shanxi Province, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 86, 306–317. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2011.03.004

Kier, W. M. (2012). The diversity of hydrostatic skeletons. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 1247–1257. doi:10.1242/jeb.056549

Kim, J., Jang, H. W., Shin, J.-U., Hong, J.-W., and Myung, H. (2018). Development of a mole like drilling robot system for shallow drilling. IEEE Access 6, 76454–76463. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2884495

Kindlein, J. W., and Guanabara, A. S. (2005). Methodology for product design based on the study of bionics. Mater. Des. 26, 149–155. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2004.05.009

Kou, H. L., Chen, Y. J., and Wang, Y. K. (2025). Development and experimental research of a biomimetic earthworm subsea lateral survey instrument. Ocean. Eng. 43, 1–13. doi:10.16483/j.issn.1005-9865.2025.04.001

Lee, J., Kim, J., and Myung, H. (2019). “Design of forelimbs and digging mechanism of biomimetic mole robot for directional drilling,” in RITA. Editors A. P. P. Abdul Majeed, J. Mat-Jizat, M. Hassan, Z. Taha, H. Choi, and J. Kim (Singapore). doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8323-6_28

Lee, J., Tirtawardhana, C., and Myung, H. (2020). “Development and analysis of digging and soil removing mechanisms for mole-bot: bio-inspired mole-like drilling robot,” in IEEE/RSJ international conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7792–7799. doi:10.1109/IROS45743.2020.9341230

Liang, Y. H., and Ren, L. Q. (2016). Preliminary study of habitat and its bionics. J. Jilin Univ. Eng. Technol. 46 1746–1756. doi:10.13229/j.cnki.jdxbgxb201605053

Liem, W. L., Kanada, A., and Mashimo, T. (2024). Earthworm-inspired robot design: reducing the number of actuators through embedded motor between segments. IEEE 12, 114636–114644. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3445330

Liu, G. M. (2009). Coupling bionic research on the adhesion and resistance reduction of the earthworm surface. Changchun, China: Jilin University. Ph.D. Thesis.

Ma, Y., Evans, T. M., and Cortes, D. D. (2020). 2D DEM analysis of the interactions between bio-inspired geo-probe and soil during inflation–deflation cycles. Granul. Matter 22, 11. doi:10.1007/s10035-019-0974-7

Martinez, A., DeJong, J. T., Jaeger, R. A., and Khosravi, A. (2020). Evaluation of self penetration potential of a bio-inspired site characterization probe by cavity expansion analysis. Can. Geotech. J. 57, 706–716. doi:10.1139/cgj-2018-0864

Niiyama, R., Matsushita, K., Ikeda, M., Or, K., and Kuniyoshi, Y. (2022). A 3D printed hydrostatic skeleton for an earthworm-inspired soft burrowing robot. Soft Matter 18, 7990–7997. doi:10.1039/d2sm00882c

Prasath, S. G., Mandal, S., Giardina, F., Kennedy, J., Murthy, V. N., and Mahadevan, L. (2022). Dynamics of cooperative excavation in ant and robot collectives. Elife 11, e79638. doi:10.7554/eLife.79638

Saxena, A., Pathak, A. K., Ojha, K., and Sharma, S. (2017). Experimental and modeling hydraulic studies offoam drilling fluid flowing through vertical smooth pipes. Egypt. J. Pet. 26, 279–290. doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2016.04.006

Shi, W. P., Ren, L. Q., and Yan, Y. Y. (2005). The creeping mechanism of the non-smooth wavy surface of earthworm body. Mech. Eng. 27, 73–74. doi:10.6052/1000-0992-2004-272

Song, Y. B. (2024). Soft coal drilling technology and application based on air directional drilling. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2771, 012019. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2771/1/012019

Tan, J., Mekloumian, N., Harvey, D., and Akmeliawati, R. (2025). Nature-inspired solutions for sustainable mining: applications of NIAs, swarm robotics, and other biomimicry-based technologies. Biomimetics 10, 181. doi:10.3390/biomimetics10030181

Tang, P. (2020). Development and application of multi-stage variable-diameter drill bit and double spiral anti-lock drill pipe. Mech. Res. Appl. 33, 200–202. doi:10.16576/j.cnki.1007-4414.2020.03.059

Tao, J. J., Huang, S. C., and Tang, Y. (2020). SBOR:A minimalistic soft self-burrowing-out robot inspired by razor clams. Bioinspir. Biomim. 15, 055003. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/ab8754

Trivedi, D., Rahn, C. D., Kier, W. M., and Walker, I. D. (2008). Soft robotics: biological inspiration, state of the art, and future research. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 5, 99–117. doi:10.1080/11762320802557865

Van Wassenbergh, S., Heindryckx, S., and Adriaens, D. (2017). Kinematics of chisel-tooth digging by African mole-rats. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 4479–4485. doi:10.1242/jeb.164061

Velivela, P. T., and Zhao, Y. F. (2022). A comparative analysis of the state-of-the-art methods for multifunctional bio-inspired design and an introduction to domain integrated design (DID). Designs 6, 120. doi:10.3390/designs6060120

Wang, Y. L., Zhai, X. X., and Sun, Y. N. (2012). Analysis of mechanism of borehole wall protection in soft coal seams with outburst threat. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. 32, 50–55.

Wu, W. D., Zhegn, K. F., Zhang, D., Li, S. K., and Li, M. H. (2024). Study on coal loading performance bridge shearer with spiral drum in thin seam coal. Coal Technol. 43, 237–240. doi:10.13301/j/cnki.ct.2024.09.048

Wu, J. Y., Zhang, W. Y., Wang, Y. M., Ju, F., Pu, H., Riabokon, E., et al. (2025). Effect of composite alkali activator proportion on macroscopic and microscopic properties of gangue cemented rockfill: experiments and molecular dynamic modelling. Int. J. Min. Met. Mater. 32, 1813–1825. doi:10.1007/s12613-025-3140-8

Xia, R., Li, B., Wang, X. W., Li, T. J., and Yang, Z. J. (2019). Measurement and calibration of the discrete element parameters of wet bulk coal. Measurement 142, 84–95. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.04.069

Yang, M. L., Long, Y. Y., Shi, Y., Guo, Z. X., and Li, Y. H. (2023). Discrete element simulation analysis of excavator bucket tooth load based on EDEM. Res. Explor. Lab. 42, 101–106. doi:10.19927/j.cnki.syyt.2023.04.020

Yao, Z. Z., Zhang, Z. G., and Dai, L. C. (2023). Research on hydraulic thruster-enhanced permeability technology of soft coal drilling through strata based on packer sealing method. Processes 11, 1959. doi:10.3390/pr11071959

Yi, L., Bo, H., and Yan, S. (2007). Kinematics analysis and statics of a 2SPS+UPR parallel manipulator. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 18, 619–636. doi:10.1007/s11044-007-9054-6

Zakeri, M., and Faraji, J. (2023). Modeling the adhesion of spherical particles on rough surfaces at nanoscale A thermodynamic model of grain-grain contact force. Int. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 124, 103385. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2023.103385

Zhang, Y. (2023). Design of anti-stuck drilling rod for drilling soft coal seam. Coal Technol. 42, 226–230. doi:10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2023.04.051

Zhang, G. R., and Wang, E. Y. (2023). Risk identification for coal and gas outburst in underground coal mines: a critical review and future directions. Gas. Sci. Eng. 118, 2–19. doi:10.1016/j.jgsce.2023.205106

Zhang, H. J., Yao, K., and Zhang, Y. Z. (2017). Drilling technology and equipment in soft coal seam. Saf. Coal Mines. 48, 99–102. doi:10.13347/j.cnki.mkaq.2017.07.026

Zhang, L., Ren, T., Aziz, N., and Zhang, C. (2019). Evaluation of coal seam gas drainability for outburst-prone and high-CO2-containing coal seam. Geofluids 2019, 3481834. doi:10.1155/2019/3481834

Zhang, J., Wang, Y., and Huang, H. J. (2020). Directional drilling technology and equipment of pneumatic screw motor in soft seam. Coal Geol. Explor. 48, 36–41. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2020.02.007

Zhang, L., Wang, L., Sun, Q., Badal, J., and Chen, Q. S. (2024). Multi-objective design optimization of clam-inspired drilling into the lunar regolith. Acta Geotech. 19, 1379–1396. doi:10.1007/s11440-023-02119-5

Zhang, J. X., Wang, Q. Y., Niu, F. S., Yu, X. D., Chagn, Z. J., Wu, F., et al. (2024). Simulation and verification of discrete element parameter calibration of pulverized coal particles. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 45, 1244–1263. doi:10.1080/19392699.2024.2379405

Keywords: soft coal seams, bionic bit, impact extrusion, slag discharge efficiency, discrete element

Citation: Tian H, Tian D and Chen Z (2025) Study of high-frequency impact extrusion bionic drilling technology for soft coal seams. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1712684. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1712684

Received: 30 September 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jiangyu Wu, China University of Mining and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Tian, Tian and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongjie Tian, dGhqODh0aGpAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Hongjie Tian

Hongjie Tian Dongzhuang Tian1,2

Dongzhuang Tian1,2