- 1School of Earth and Environment, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, Anhui, China

- 2National Key Laboratory of Deep Coal Safety Mining and Environmental Protection, Huainan, Anhui, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Xinjiang Coal Resources Green Mining, Ministry of Education, Xinjiang Institute of Engineering, Urumqi, China

Underground coal mining causes movement of overlying rock layers and damage to geological structures, leading to surface subsidence and the development of tensile cracks. To investigate the influence of surface cracks on soil structure and properties, this study was carried out in the Zhuzhuang Mine subsidence area. The research focused on two typical tensile cracks that segmented the area into three plots (HP, MP, LP), with 105 soil samples collected from around the cracks. By measuring soil particle size distribution (PSD), organic matter (SOM), moisture content (MC), available phosphorus (SAP), and available kalium (SAK), and combining multifractal theory to analyze soil structural heterogeneity. The results indicate that surface fissures promote the formation of preferential flow paths on the slope, leading to the migration of clay particles towards the fissures. The average surface clay content in the HP area is 5.45%, significantly higher than the 3.03% in the LP area. The fractal dimension shows that the fractal dimension of surface soil is lower than that of deep soil, and increases with depth, reflecting that cracks exacerbate the stratification and heterogeneity of soil structure. Correlation analysis further revealed that there was a significant negative correlation (−0.916) and positive correlation (0.903) between the viscosity and powder particles in the HP region and the fractal dimension D(0), while there was a strong negative correlation (−0.992) between the powder particles in the LP region and D(1). There is a positive correlation between soil moisture and clay content, but the nutrient migration path in the LP area is disrupted due to the obstruction of cracks and terrain, resulting in a weakened correlation with particle size. This study elucidates the mechanism by which mining subsidence cracks affect soil physical and chemical properties by altering soil particle transport and water distribution, providing a theoretical basis for land reclamation and ecological restoration in mining areas.

1 Introduction

The underground coal mining activities cause the movement of overlying rock layers and the destruction of geological structures, which was the fundamental reason for inducing surface subsidence and the formation of tensile cracks (Behera and Singh Rawat, 2023; Dawei et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2023) These drastic changes in surface morphology had become a key mechanism for soil system degradation in coal mining subsidence areas (Zhao et al., 2015). During the process of surface subsidence above the coal mining face, when the tensile and shear stresses generated by local subsidence exceed the mechanical bearing capacity range of the soil, cracks will form in the surface soil (He et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2024). The number and scale of cracks were influenced by various factors, including the range of the coal mining face, the thickness of the loose layer, and the physical properties of the surface soil (Gao et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2025c). Previous research had systematically revealed the negative impact of coal mining subsidence on soil systems through surface cracks, pointing out that it was the core link in vegetation degradation and ecosystem function damage in mining areas (Li et al., 2023). Therefore, the soil environment in the surface crack zone of coal mining subsidence areas has attracted more attention.

At present, many researches generally believed that surface tension cracks were one of the main reasons for the decline in arable land quality and ecological environment deterioration in mining areas (Li et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). The formation and development of cracks constitute a complex dynamic process involving multiple factors such as geological structure, rock thickness, mining rate, surface topography, and changes in soil moisture content, and exhibited spatiotemporal characteristics such as “leading” and “lagging” (Guo et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2024b). The generation of cracks significantly changed the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil, destroyed the integrity of soil structure, and forms “preferential flow” channels for water and gas (Fan et al., 2023). And priority flow paths can promote the leaching of pollutants (such as heavy metals and nutrients) into groundwater (Liu et al., 2025), this not only exacerbated soil moisture evaporation and deep leakage, leading to a decrease in soil moisture content and a trend towards aridification, but also directly affected soil porosity, bulk density, permeability, and water holding capacity, thereby accelerating soil weathering. In addition, coal mining subsidence and crack development were often accompanied by soil nutrient loss. Numerous studies had shown that key fertility indicators such as organic matter, total phosphorus, and available potassium in subsidence areas were significantly reduced, resulting in serious damage to soil quality and productivity (Hou H. et al., 2021; Hou K. et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). The deterioration of soil physicochemical properties further led to an imbalance in microbial community structure and a decrease in enzyme activity. Cracks can alter the soil microenvironment (such as moisture, aeration, nutrient availability), thereby affecting the structure and activity of microorganisms (Li et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2021). Meanwhile, many scholars had pointed out that soil particle composition was closely related to its physical and chemical properties, and emphasized that soil particle distribution was a key indicator reflecting changes in soil environment (Hu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015; Zou et al., 2014), and the migration of fine particles (especially clay) through cracks could indeed facilitate the transport of adsorbed contaminants, including heavy metals (Huang et al., 2020). Its spatial variability can effectively indicate the response of soil systems to external disturbances (Lu et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2025b). Therefore, researchers often use different particle size ratios to explore the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of soil (Qi et al., 2018; Shahbazi et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2021).

The method based on fractal theory had become an important technique for quantitatively studying the characteristics of soil particle distribution (PSD) in recent years (Yang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021). Early research often used traditional hydrometer methods to determine soil particle composition and evaluate the single fractal dimension of PSD. With the widespread application of laser diffraction method (laser particle size analyzer) in soil particle composition determination, research on PSD multifractal parameters was also increasing. Compared with traditional statistics such as mean and variance, multifractal analysis can better capture the local singularity and scaling characteristics of soil PSD, and is particularly effective in detecting hidden heterogeneity and complex spatial patterns caused by disturbances such as cracks (Pan et al., 2025). Especially under different land use or vegetation types, multifractal parameters help to reveal the complexity and heterogeneity of soil PSD (De et al., 2008; Jing et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). However, there is still a lack of research on the distribution characteristics of soil particles in coal mining subsidence areas, especially the limited description of the impact of cracks on soil particle distribution.

Therefore, this study focused on the coal mining subsidence area of Zhuzhuang Mine in Huaibei City as the main research area, and used multifractal dimension to analyze the distribution characteristics of soil particles around surface cracks, studied the roughness and non-uniformity of soil particle composition, as well as the changes in soil texture and physicochemical properties around cracks, providing a basis for land reclamation and ecological restoration in mining areas.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

105 soil samples were collected on both sides of the surface cracks in the study area, as shown in Figure 1. HP were 35 samples, MP were 40 samples, and LP were 30 samples (Figure 1c). Sampling was conducted at multiple depths (0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, 40–60 cm, 60–80 cm, and 80–100 cm) within each zone to ensure vertical and horizontal representativeness. The study area is situated above the 3,522 working face of the Zhuzhuang Coal Mine in Huaibei, with geographical coordinates of 116°50′42′E and 33°57′29′N. The 3,522 working face extends 150 m in length and 130 m in width, oriented in a southwest–northeast direction. This region has a warm temperate semi humid monsoon climate. Rainfall is concentrated in summer, with an average annual precipitation of 823.4 mm and an extreme maximum annual precipitation of 1441.4 mm. The surface soil type is abandoned farmland, with a groundwater depth of 1–3 m. The terrain gradually decreases from north to south, and cracks of different sizes appear on the surface of the subsidence area. Two east–west trending typical cracks, C1 and C2, were selected, with lengths of 51.6 m and 106.7 m, widths of 35–45 cm, and depths of 50–75 cm, respectively. According to the topography, C1 and C2 divided the study area into three parts, named HP, MP and LP, and there were different tilt angles in each part. The dip angle of the HP is 1⁓2°, the MP is 0⁓1°, and the LP is 2⁓3°.

Figure 1. Research area topography and sampling point layout [(a–c) are the location of the study area, the surface cracks in the subsidence area, and the layout of sampling points, respectively].

2.2 Methods for testing physical and chemical properties of soil samples

Divided the collected fresh soil samples into two parts, one part was measured for soil moisture content (MC) by drying method, and the other part was air dried to remove garbage and other impurities. Then, the samples were crushed and sieved and used for the detection of particle size and other physical and chemical indicators. A RISE-2006 laser particle size analyzer was employed to measure the soil particle size, with a measuring range of 0.02⁓2000 μm. The soil organic matter (SOM) was determined using the potassium dichromate volumetric method–external heating method, and then the sodium bicarbonate extraction–spectrophotometric method was used to determine soil available phosphorus (SAP). The sodium tetraphenylborate colorimetric method is used to detect soil available kalium (SAK).

2.3 Methods for analyzing soil PSD

The multifractal method was used to study the spatial variability of soil PSD of the individual samples. The interval of soil particle size I = [0.5,105] (μm) was considered, and I was subdivided into 32 subintervals

and

where,

The generalized dimensions of q = 0 and q = 1 are called the capacity dimension D (0) and entropy dimension D(1), respectively. D(0) can characterize the PSD range of soil, commonly known as the box-counting dimension, and D(1) can characterize the concentration level of soil PSD, known as information entropy. And the most uneven case gives D(0) = 1 because it has the richest distribution of soil particles, and the most uniform distribution follows D(0) = 0. On the other hand, a D(1) value close to 1 indicates the uniformity of measurement on the unit size set, and a D(1) value close to 0 indicates the scale subset of the irregular set.

Generally, the multifractal spectrum f(α) of the measure is used to express the results, and f(α) is defined by the Legendre transform as:

where,

α is the Lipschitz–Holder exponent, characterizing the average strength of singularity in measure u. f(α) is the fractal dimension of the subset of the interval that dominates the sum for different q having the same Lipschitz-Holder exponent α. For values −10 ≤ q ≤ 10 and step 1, multifractal attributes α and f(α), were obtained based on Equations 3–5, using the least square fitting method.

The multifractal spectrum width Δα, Δα = αmax− αmin, can exhibit the nonuniformity of the soil PSD in the overall fractal structure. Δf, Δf = f(αmin) −f(αmax), exhibits the multifractal spectrum shape feature and characterizes the asymmetry of the soil PSD. The asymmetrical ƒ(α)-α spectra are shaped as a left-skewed spectrum when Δƒ > 0, and as a right-skewed spectrum when Δƒ < 0. In addition, Δƒ is zero for the symmetry shape. The more left-skewed the multifractal spectrum is, the more significant the impact of high value information of the variable on the soil PSD, indicate dominance of coarse particles. In contrast, the low value information has a more significant impact on the soil PSD, indicate dominance of fine particles.

2.4 Statistical analysis of data

Statistical analysis and graphical representation were conducted on the physical and chemical properties of different soil samples and the minimum, maximum, median, mean, skewness, kurtosis, and coefficient of variation (CV) data of PSD using SPSS 20.0 and Origin 2021. Central tendency can be predicted by the mean and median, and if the mean and median have similar values, the outliers will not dominate the measure of central tendency in their distribution. The CV is the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean (Meng et al., 2015), which reflects the absolute value of data dispersion, and is employed to illustrate the variation in PSD and multifractal properties in different soils. Variability in different soil PSDs can be divided into the following levels: low variability (CV<15%), moderate variability (15%≤CV ≤ 35%), and high variability (CV>35%) (Chen et al., 2021).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 The effect of coal mining activities on soil particle composition

Soil particle was classified using the soil taxonomy developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA): clay (˂0.002 mm), silt (0.002⁓0.05 mm), and sand (0.05⁓2 mm) (Zhang et al., 2019). Based on the classification results, the soil texture of this study area was silt with a relatively uniform texture (Figure 2).

The soil particle composition of different regions were shown in Supplementary Table S1. The formation of cracks caused obvious changes in the local topography and certain differences in the composition of soil particles. HP had the highest terrain with a slope of 1°–2°, the average content of clay was 5.45%, with a maximum in the 40–60 cm soil layer being 31.09%, and the minimum in the 60–80 cm soil layer being 0.58%. However, the variation in clay content in different soil layers was high, and all CVs were greater than 35%. The content of silt had low variability in HP, with an average content of 94.10%, a maximum of 98.79% in the 40–60 cm soil layer, and a minimum of 68.16% in the 80–100 cm soil layer. The sand content was low, only 0.45%. In MP, the variability of clay particles was greater than 35%, indicating high variability, but the variability of clay and silt particles in MP was less than that in HP in each soil layer. Compared with HP, the distribution of clay and silt particles in MP was more uniform in each soil layer. The average content of clay is 3.11%, silt was 96.07% and sand was 0.82%. Compared with HP and MP, LP had the lowest terrain, with a slope of 2°–3°. The average content of clay was only 3.03%, less than HP and MP, and the variation degree in the 40–60 cm, 60–80 cm and 80–100 cm soil layers was significantly higher than that in the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm. However, the silt content in LP was higher than that in HP and MP, the variation degree was low in each soil layer, and the mean value of silt in each layer was approximately equal to the median, that is, the outliers did not affect the measures of central tendency.

The geological activities caused by coal mining subsidence not only result in physical damage (Xie et al., 2024), but also exacerbate the spatial heterogeneity of soil texture by driving differential particle transport, as shown in Figure 3. Although the soil particle composition in the entire study area is highly uniform, mainly consisting of silt (95.56%) and clay (3.86%), the surface tension cracks induced by coal mining subsidence acted as a strong geological soil force, reshaping the original soil texture and leading to significant differences in soil particle composition between different regions. Cracks form a “soil reformation process” by eroding the soil and altering the transport path of particles. In the HP area with higher terrain, cracks becomed the dominant channel for preferential leaching of clay particles, leading to significant depletion of their content; In the MP enclosed by cracks on both sides, there was a phenomenon of leaching and deposition of clay particles in deep soil, characterized by a higher content of clay particles at the bottom than at the surface; In the LP with low and steep terrain, the combined effect of terrain and crack exacerbated the rapid loss of surface clay particles.

Figure 3. Contour map of particle size distribution in different areas [(a–c)represent the content of soil clay, silt, and sand, respectively].

3.2 The effect of surface tension cracks on soil physicochemical properties

Due to coal mining subsidence, there was significant spatial heterogeneity in the physical and chemical properties of soil in different crack regions (HP, MP, LP), as shown in Figure 4, and Supplementary Table S2 provides descriptive statistical data on MC, SOM, SAP, and SAK at different depths within these areas. The MC showed a trend of HP > MP > LP, especially in the surface layer of 0–20 cm. The average MC in the HP region reached 11.55%, while in the LP was only 6.30%, indicating that the degree of crack development had a significant impact on soil water holding capacity. And cracks alter infiltration and evaporation patterns (Zou et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2024a). In the HP region, cracks may enhance deep infiltration, while in the LP region, steep slopes promote surface runoff and reduce effective infiltration. In contrast, SOM showed the opposite trend (LP > MP > HP), with an average topsoil content of 3.54 g/kg in the LP region, significantly exceeding HP’s 1.39 g/kg, indicating that organic matter may be lost in higher crack regions. And the higher SOM in LP may be attributed to shrub litter, which decomposes slower than herbaceous litter and accumulates more organic matter. The SAP content in the MP region was slightly higher, with an average surface value of 3.75 mg/kg compared to the HP and LP regions. In addition, the concentration of SAP decreased with increasing depth in all regions, reflecting the trend of phosphorus accumulation in the surface soil. It is worth noting that SAK was most prominent in the HP region, with an average surface content of 129.77 mg/kg, significantly exceeding the MP and LP regions. Overall, the spatial variation of soil physicochemical properties reflects the structural degradation and uneven distribution of nutrients in the soil affected by subsidence cracks caused by mining.

Figure 4. Characteristics of soil physicochemical properties in different crack regions [(a–d) represent MC, SOM, SAP, and SAK, respectively].

3.3 Multifractal properties of soil PSD in different crack regions

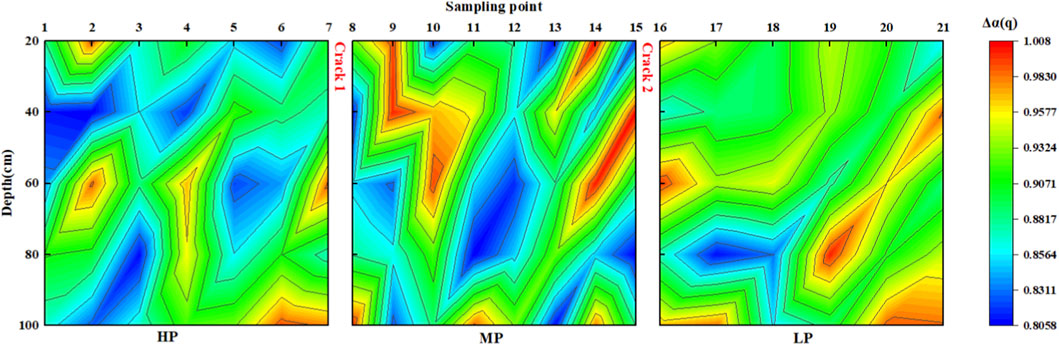

In different tensile crack regions (HP, MP, LP) of coal mining subsidence areas, multifractal parameters exhibited significant spatial differentiation characteristics, as shown in Supplementary Table S3. Overall, the capacity dimension D (0) of each crack region ranged from 0.8615 to 1.0000, and the information dimension D (1) ranged from 0.9570 to 0.9993, indicating that soil properties have obvious multifractal characteristics at different depths and strong spatial heterogeneity. Among them, the HP region D (0) and D (1) were generally higher, reflecting a relatively more complex structure; The low depth values in the MP and LP regions indicated the presence of a relatively homogeneous structure locally. In terms of singular spectrum parameters, the range of Δα(q) was between 0.8059 and 1.0083, and Δf(α) was between 0.0176 and 0.3379, indicating that all crack regions had varying degrees of local singularity, and the differences in spectral width and morphology reflected the uneven distribution of soil properties at different depths. The significant changes in Δα(q) and Δf(α) in the HP region indicated significant local variability, and the MP and LP regions exhibited more concentrated singular spectral features at certain depths, reflecting the enhanced consistency of the dominant structure.

The spatial distribution maps of the multifractal attributes of the soil PSD in the three regions were presented in Figures 5–8. It can be seen that the multifractal parameters D(0), D(1), Δα(q), and Δf(α) showed significant differences with soil depth, indicating that surface tension cracks had a significant impact on the spatial heterogeneity of soil structure. The overall performance of the HP region showed the highest D(0) and D(1) values, especially in the shallow to middle soil layers (20–80 cm), with significant fluctuations and relatively high Δα(q) values, as well as positive Δf(α), indicating that this region was most affected by tensile cracks, and the soil structure was complex and uneven in height; The parameter values in the MP area were centered, with local low values appearing in the middle of the profile, reflecting a moderate degree of tensile crack influence and transitional structural characteristics. The LP region exhibited the lowest D(0), D(1), and smaller Δα(q), with Δf(α) tending towards zero, indicating that it was least affected by tensile cracks and maintained a relatively homogeneous and continuous soil structure. The spatial distribution characteristics of fractal dimension indicated that the surface tension cracks caused by coal mining subsidence significantly affected the heterogeneity of soil physical properties by changing the pore distribution and structural composition in the soil profile. The HP region was most affected, with significant soil structure fragmentation characteristics, while the LP region maintained good structural integrity, and the MP region was in a transitional state between the other regions, reflecting the spatial differentiation of tension cracks on the soil environment.

Figure 5. Spatial distribution maps of D(0) of soil PSD at different depths in three sampling plots.

Figure 6. Spatial distribution maps of D(1) of soil PSD at different depths in three sampling plots.

Figure 7. Spatial distribution maps of Δα(q) of soil PSD at different depths in three sampling plots.

Figure 8. Spatial distribution maps of Δf(α) of soil PSD at different depths in three sampling plots.

3.4 Relationship between particle composition and fractal dimension of crack in the soil

Underground coal mining has a great influence on the terrain above the working face, and the terrain gradually slopes downward from north to south. On both sides of C1, HP on the northern side was 10∼15 cm higher than MP on the southern side, but the terrain in the MP area was relatively flat, while the terrain in the LP area was the lowest in the whole study area, and the terrain slope was the greatest. The analysis of the whole study area from north to south showed that the clay content decreased with decreasing terrain, and the ground slope also led to an uneven distribution of local clay particles, resulting in a high spatial variability in the particle size distribution. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), soil particles are divided into clay, silt and sand. We studied the distribution characteristics of particle size and the spatial variability of particle size based on multifractal dimensions. However, there was a correlation between clay, silt, and sand and multifractal dimension D(0), D(1), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Correlation diagram among multiple variables in different regions [(a,b) represents D(0) and D(1) in the multiple variables, respectively].

D(0) characterize the range of soil PSD, and the correlations between clay, silt, and sand and D(0) in the whole study area were −0.613 (p < 0.001), 0.549 (p < 0.001), and 0.236 (p < 0.05), respectively. However, the analysis of HP, MP and LP in three different parts showed that in HP, clay, silt, and sand and D(0) showed strong correlations, which were −0.916 (p < 0.001), 0.903 (p < 0.001) and 0.599 (p < 0.001), respectively. In LP, sand and D(0) also showed a high correlation, which was 0.764 (p < 0.001), while in MP, only clay showed a weak correlation, which was −0.473 (p < 0.01). D(1) characterize the concentration level of PSD. The distribution kernel density map of clay particles in Figure 8 shows that the waveform is left biased, indicating that the kernel density tends to move toward the direction of numerical reduction. In other words, the difference in clay content among HP, MP and LP was narrowing, and there was a dynamic convergence characteristic. However, there was an obvious multipeak shape in MP and LP, indicating that the distribution of clay content in MP and LP had multipolar differentiation. Moreover, in HP, there was a high correlation between clay content and D(1), which was 0.910 (p < 0.001), and the correlation was weak in MP and LP. There was a high correlation between the powder and D (1) in HP and LP, which was −0.999 (p < 0.001) and −0.992 (p < 0.001), respectively. The kernel density map of sand showed that the contents of HP, MP and LP were relatively uniform; therefore, there was a strong correlation between sand and D(1), which were −0.598 (p < 0.001), −0.833 (p < 0.001) and −0.781 (p < 0.001), respectively.

3.5 Relationship between soil particle size and physicochemical properties

The generation of cracks not only affects the particle size structure of the soil, but also changes the physical and chemical properties of the local soil (Zhang et al., 2009). And cracks can reduce soil fertility, increase erosion risk, alter hydrological pathways, and thus affect agricultural productivity and ecosystem services such as water regulation and nutrient cycling (Li et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2018). In this study, it was pointed out that there was a positive correlation between the content of soil clay and organic matter. The increase in clay content in the study area made the content of organic matter significantly higher than in other areas. However, in HP and LP in the study area, there was a negative correlation between the content of organic matter and clay, as shown in Figure 10, and only a weak positive correlation was found in the MP area. It was noticed in this study that the different types of soil utilization also had a certain impact on the content of organic matter. In the study area, the plants growing in the surface soil were different. Different vegetation types can indeed affect SOM through variations in litter quality, root exudates, and microbial activity. Shrubs in LP may contribute to higher SOM due to deeper root systems and slower decomposition, while herbaceous plants in HP may lead to more rapid nutrient cycling. In HP and MP, herbaceous plants were in the majority, while in the LP area, shrubs were the main plants, which would also affect the migration and transformation of soil organic matter (Li et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2025a). At the same time, the generation of cracks blocked the migration path of organic matter, which changed the relationship between organic matter and particle size. It is proposed that the soil MC and the soil particle size have a significant correlation, the surface cracks cause the loss of soil clay particles, and the soil MC gradually decreases. Clay particles are smaller and can more easily absorb soil nutrients, and surface cracks will accelerate the loss of fine particles, which will affect the MC, SOM, SAP and SAK. In the HP and MP regions, there was a clear negative correlation between the content of clay particles and sand and water content. At the same time, there was a strong positive correlation between silt, sand and water content in the MP region, but In the LP region, due to the greater slope (2°–3°), lower terrain, and the presence of cracks disrupt the MC and particle movement. Cracks act as barriers and divert flow paths, preventing clay and moisture from accumulating in a correlated manner, led to the trend of this correlation gradually weakened. The cracking of the surface, makes the study area unique. The whole study area is divided into three relatively independent areas. Cracks block soil element migration movement, and ground subsidence also disrupts soil migration. Soil elements with small particle migration toward the lower part of the terrain may be the reason for the destruction of the correlation between soil elements.

Figure 10. Correlation between soil particle size and physical and chemical properties [(a–c) respectively represent tensile crack regions of HP, MP and LP].

4 Conclusion

In view of the surface cracks in the subsidence area of the Huaibei coal mine, the distribution of soil particle size was studied, the fractal dimension of particle size was calculated, and part of the physical and chemical properties of the soil was detected. The following conclusions were drawn:

1. The tensile cracks disordered the distribution characteristics of soil particle size in the study area. In LP with the lowest terrain and the greater slope, the average clay content was 3.03%, which was lower than MP and HP. The tensile cracks made the surface soil collapse to deep depression, hindering the migration of clay particles. Under the action of rain scouring and leaching, clay particles were more likely to gather at the cracks. Moreover, the study of fractal dimension indicated that the PSD range, PSD concentration, PSD heterogeneity and PSD asymmetry of soil showed high spatial variability.

2. The soil particle size in the tensile cracks area was not only related to the fractal dimension D (0) and D (1), but also related to the physical and chemical properties of the soil. In HP, clay and silt had strong correlations with D (0), which were −0.916 and 0.903, respectively, and the correlation between clay and D (1) was high, which was 0.910. In MP, there was a strong correlation between sand and D (1) as −0.833. In LP, the correlation between silt and D (1) was −0.992. There was a positive correlation between clay and MC in three relatively independent plots, and in HP, there was a positive correlation between silt, sand, MC and D, but this correlation was not appeared in LP, but there was a correlation between SOM, SAP and SAK in LP.

3. For different crack areas, HP area should intervene in crack development and clay improvement to maintain moisture and nutrients, MP area should promote vegetation cover to stabilize soil structure, and LP area should prioritize erosion control and organic matter addition to improve soil structure.

These research results have certain guiding significance for the treatment and restoration of tensile fracture soil in coal mining subsidence area. However, this paper lacks continuous research on the region, so it is hoped that samples can be collected at different time points for analysis and detection, so as to study the influence of surface cracks in mining subsidence areas on soil more comprehensively.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AL: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. TF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. CY: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. SW: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. XW: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Open Fund of Huaibei Mining Group in 2019 and 2021.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the tutor for correcting the organization and grammatical errors in the structure of the paper, thanks the classmates of the research group for assisting the author in carrying out the experiment and organizing the experimental data, and the author expresses the gratitude to the research area provided by Huaibei Mining Group, the experimental conditions provided by Anhui University of Science and Technology, and the financial assistance provided Huaibei Mining Group.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Huaibei Mining Group. The funder had the following involvement in the study: study design and study area selection.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2025.1716591/full#supplementary-material

References

Behera, A., and Singh Rawat, K. (2023). A brief review paper on mining subsidence and its geo-environmental impact. Mater. Today Proc. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.183

Chen, T. L., Shi, Z. L., Wen, A. B., Yan, D. C., Guo, J., Chen, J. C., et al. (2021). Multifractal characteristics and spatial variability of soil particle-size distribution in different land use patterns in a small catchment of the three gorges reservoir region, China. J. Mountain Science 18, 111–125. doi:10.1007/s11629-020-6112-5

Dawei, Z., Kan, W., Zhihui, B., Zhenqi, H., Liang, L., Yuankun, X., et al. (2019). Formation and development mechanism of ground crack caused by coal mining: effects of overlying key strata. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 1025–1044. doi:10.1007/s10064-017-1108-2

De, W., Fu, B., Zhao, W., Hu, H., and Wang, Y. (2008). Multifractal characteristics of soil particle size distribution under different land-use types on the loess Plateau, China. Catena 72, 29–36. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2007.03.019

Fan, C., Zhao, L., Hou, R., Fang, Q., and Zhang, J. (2023). Quantitative analysis of rainwater redistribution and soil loss at the surface and belowground on karst slopes at the microplot scale. Catena 227, 107113. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2023.107113

Gao, C., Xu, N., Ni, X., Ma, H., and Wang, C. (2016). Research on surface crack depth and crack width caused by coal mining. Coal Engineering 48, 81–83.

Guo, W., Guo, M., Tan, Y., Bai, E., and Zhao, G. (2019). Sustainable development of resources and the environment: mining-induced eco-geological environmental damage and mitigation measures—A case study in the Henan coal mining area, China. Sustainability 11, 4366. doi:10.3390/su11164366

He, X., Zhao, Y. X., Yang, K., Zhang, C., and Han, P. H. (2021). Development and formation of ground fissures induced by an ultra large mining height longwall panel in shendong mining area. Bull. Engineering Geology Environment 80, 7879–7898. doi:10.1007/s10064-021-02429-6

Hou, H., Ding, Z., Zhang, S., Guo, S., Yang, Y., Chen, Z., et al. (2021a). Spatial estimate of ecological and environmental damage in an underground coal mining area on the loess Plateau: implications for planning restoration interventions. J. Clean. Prod. 287, 125061. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125061

Hou, K., Qian, H., Zhang, Y., Qu, W., Ren, W., and Wang, H. (2021b). Relationship between fractal characteristics of grain-size and physical properties: insights from a typical loess profile of the Loess Plateau. Catena 207, 105653. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2021.105653

Hu, Z., Wang, X., and He, A. (2014). Distribution characteristic and development rules of ground fissures due to coal mining in windy and sandy region. J. China Coal Soc. 39, 11–18.

Huang, B., Yuan, Z., Li, D., Zheng, M., Nie, X., and Liao, Y. J. E. S. P. (2020). Effects of soil particle size on the adsorption, distribution, and migration behaviors of heavy metal(loid)s in soil: a review. A Review 22, 1596–1615. doi:10.1039/d0em00189a

Jing, Z., Wang, J., Wang, R., and Wang, P. (2020). Using multi-fractal analysis to characterize the variability of soil physical properties in subsided land in coal-mined area. Geoderma 361, 114054. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.114054

Li, T. Y., He, B. H., Zhang, Y., Tian, J. L., He, X. R., Yao, Y., et al. (2016). Fractal analysis of soil physical and chemical properties in five tree-cropping systems in Southwestern China. Agrofor. Systems 90, 457–468. doi:10.1007/s10457-015-9868-9

Li, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, G., Xiong, K., and Cai, L. (2020). Dynamic variations in soil moisture in an epikarst fissure in the karst rocky desertification area. J. Hydrology 591, 125587. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125587

Li, Y., Lv, G., Shao, H., Dai, Q., Du, X., Liang, D., et al. (2021). Determining the influencing factors of preferential flow in ground fissures for coal mine dump eco-engineering, Determining Influencing Factors Preferential Flow Ground Fissures Coal Mine Dump Eco-Engineering. 9, e10547, doi:10.7717/peerj.10547

Li, Y., Liu, H., Su, L., Chen, S., Zhu, X., and Zhang, P. (2023). Developmental features, influencing factors, and formation mechanism of underground mining-induced ground fissure disasters in China: a review. Int. Journal Environmental Research Public Health 20, 3511. doi:10.3390/ijerph20043511

Li, J., Jia, S., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., and Liu, D. J. F.Fractional (2025). Research status and the prospect of fractal characteristics of soil microstructures, 9, 223.

Liu, H., Deng, K. Z., Zhu, X. J., and Jiang, C. L. (2019). Effects of mining speed on the developmental features of mining-induced ground fissures. Bull. Engineering Geology Environment 78, 6297–6309. doi:10.1007/s10064-019-01532-z

Liu, R., Zhou, J., Chui, T. F. M., Liu, D., and Liu, Y. J. W. R. M. (2025). Preferential flow in common low impact development technologies: a review, 1–22.

Lu, S., Tang, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, L., and Gong, W. (2018). Effects of the particle-size distribution on the micro and macro behavior of soils: fractal dimension as an indicator of the spatial variability of a slip zone in a landslide. Bull. Of Eng. Geol. And Environ. 77, 665–677. doi:10.1007/s10064-017-1028-1

Meng, H., Zhu, Y., Evans, G. J., and Yao, X. (2015). An approach to investigate new particle formation in the vertical direction on the basis of high time-resolution measurements at ground level and sea level. Atmos. Environ. 102, 366–375. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.12.016

Pan, Y., Chen, M., and Chen, Y. J. E. E. S. (2025). Analysis of the relationship between soil particle fractal dimension and physicochemical properties, 84, 1–16.

Peng, X., Dai, Q., Li, C., and Zhao, L. (2018). Role of underground fissure flow in near-surface rainfall-runoff process on a rock mantled slope in the karst rocky desertification area. Eng. Geol. 243, 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2018.06.007

Qi, F., Zhang, R., Liu, X., Niu, Y., Zhang, H., Li, H., et al. (2018). Soil particle size distribution characteristics of different land-use types in the funiu mountainous region. Soil and Tillage Res. 184, 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.still.2018.06.011

Qiao, J. B., Zhu, Y. J., Jia, X. X., and Shao, M. A. (2021). Multifractal characteristics of particle size distributions (50-200 M) in soils in the vadose zone on the loess Plateau, China. Soil and Tillage Research 205, 104786. doi:10.1016/j.still.2020.104786

Shahbazi, F., Aliasgharzad, N., Ebrahimzad, S. A., and Najafi, N. (2013). Geostatistical analysis for predicting soil biological maps under different scenarios of land use. Eur. J. Of Soil Biol. 55, 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2012.10.009

Wang, J. M., Zhang, M., Bai, Z. K., and Guo, L. L. (2015). Multi-fractal characteristics of the particle distribution of reconstructed soils and the relationship between soil properties and multi-fractal parameters in an opencast coal-mine dump in a loess area. Environ. Earth Sciences 73, 4749–4762. doi:10.1007/s12665-014-3761-0

Wang, J. M., Zhang, J. R., and Feng, Y. (2019). Characterizing the spatial variability of soil particle size distribution in an underground coal mining area: an approach combining multi-fractal theory and geostatistics. CATENA 176, 94–103. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2019.01.011

Wang, H., Zhang, K., Gan, L., Liu, J., and Mei, G. J. I. J. o.D. M. (2021). Expansive soil-biochar-root-water-bacteria interaction: investigation on crack development, water management and plant growth in green infrastructure, 30, 595–617.

Wang, X., Sun, L., Zhao, N., Li, W., Wei, X., and Niu, B. (2022). Multifractal dimensions of soil particle size distribution reveal the erodibility and fertility of alpine grassland soils in the northern Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 315, 115145. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115145

Wu, C., Zheng, Y., Yang, H., Yang, Y., and Wu, Z. (2021). Effects of different particle sizes on the spectral prediction of soil organic matter. Catena 196, 104933. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2020.104933

Xie, X., Hou, E., Zhao, B., Feng, D., and Hou, P. (2024). Investigating the damage characteristics of overburden and dynamic evolution mechanism of surface cracks in gently inclined multi-seam mining: a case study of hongliu coal mine. Environ. Technol. and Innovation 36, 103897. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2024.103897

Xu, N., Gao, C., Ni, X., and Liu, M. (2015). Study on surface cracks law of fully-mechanized top coal caving mining in shallow buried depth and extra thick seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 43, 124–128.

Xu, G. S., Li, D. H., Zhang, Y. B., and Li, H. G. (2023). Overlying strata dynamic movement law and prediction method caused by longwall coal-mining: a case study. PROCESSES 11, 428. doi:10.3390/pr11020428

Yan, J., Chen, X., Cheng, F., Huang, H., and Fan, T. J. T. o.t.C. S. o.A. E. (2018). Effect of soil fracture priority flow on soil ammonium nitrogen transfer and soil structure in mining area, 34, 120–126.

Yang, C. L., Wu, J. H., Li, P. Y., Wang, Y. H., and Yang, N. N. (2023). Evaluation of soil-water characteristic curves for different textural soils using fractal analysis. WATER 15, 772. doi:10.3390/w15040772

Yang, B., Chen, Y., and Yuan, S. J. L. D.Development (2024a). Investigation on structure, evaporation, and desiccation cracking of soil with straw biochar, 35, 3126–3135.

Yang, B., Chen, Y., Zhao, C., and Li, Z. (2024b). Effect of geotextiles with different masses per unit area on water loss and cracking under bottom water loss soil conditions. Geotext. Geomembranes 52, 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.geotexmem.2023.10.006

Yuan, B., Huang, Q., Xu, W., Han, Z., Luo, Q., Chen, G., et al. (2025a). Study on the interaction between pile and soil under lateral load in coral sand. Geomechanics Energy Environ. 42, 100674. doi:10.1016/j.gete.2025.100674

Yuan, B., Huang, X., Huang, Q., Shiau, J., Liang, J., Zhang, B., et al. (2025b). Effects of particle size on properties of engineering muck-based geopolymers: optimization through sieving treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 492, 142967. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.142967

Yuan, B., Huang, X., Li, R., Luo, Q., Shiau, J., Wang, Y., et al. (2025c). Dynamic behavior and deformation of calcareous sand under cyclic loading. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 199, 109730. doi:10.1016/j.soildyn.2025.109730

Zhang, Z., Fu, W., Zhu, Z., Zhang, H., Wen, Z., and Li, Q. (2009). Characteristics of fractal dimension of limestone soil and its correlation with soil properties. SOILS 41, 90–96.

Zhang, Y., Bi, Y., Chen, S., Wang, J., Han, B., and Feng, Y. (2015). Effects of subsidence fracture caused by coal-mining on soil moisture content in semi-arid windy desert area. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 38, 11–14.

Zhang, X., Zhao, W., Wang, L., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., and Feng, Q. (2019). Relationship between soil water content and soil particle size on typical slopes of the loess Plateau during a drought year. Sci. Of Total Environ. 648, 943–954. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.211

Zhang, Z. H., Yang, F., and Li, Y. Y. (2021). An optimized method based on fractal theory to calculate particle size distribution. Geomechanics Engineering 27, 323–331.

Zhao, G., Bi, Y., and Yang, W. (2015). The impact of coal mining, subsiding on particle size composition in shen fu coal field. J. Desert Res. 35, 1461–1466.

Keywords: surface tension crack, mining induced subsidence, particle size distribution, multifractal dimension, soil physical and chemical properties

Citation: Lu A, Fan T, Yang C, Wang S and Wang X (2025) Investigation of soil particle size distribution, physical and chemical properties due to coal mining subsidence. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1716591. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1716591

Received: 30 September 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Bingxiang Yuan, Guangdong University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Chuncai Zhou, Hefei University of Technology, ChinaBeenish Jehan Khan, CECOS University of Information Technology and Emerging Sciences, Pakistan

Li Ma, Xi’an University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Lu, Fan, Yang, Wang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tingyu Fan, dHlmYW5AYXVzdC5lZHUuY24=

Akang Lu

Akang Lu Tingyu Fan1,2,3*

Tingyu Fan1,2,3* Xingming Wang

Xingming Wang