Abstract

Rapid monitoring and early elimination are important measures to control the spread of invasive plants. Ambrosia artemisiifolia is a globally distributed harmful invasive weed. The aim of this study was to clarify the invasion habitat preferences of A. artemisiifolia and the interspecific associations or phylogenetic relationships between this and native species in the Yili River Valley of Xinjiang, China. We identified the preferred habitat types of A. artemisiifolia, and investigated the composition and distribution of native species at the early stage of invasion by targeted sampling at 186 sites. By comparing the associations and phylogenetic distance between A. artemisiifolia and native species with those in Xinjiang and worldwide, we assessed the feasibility of using native species as indicators for rapid monitoring of A. artemisiifolia. A. artemisiifolia displayed an obvious invasive preference for semi-arid areas, particularly road margins (27.96%), forest (21.51%), farmland (19.35%), wasteland (12.37%), residential areas (10.75%), and grassland (8.06%). The composition and distribution of native species were similar across habitats, with more than 50% co-occurrence of A. artemisiifolia with Setaria viridis, Poa annua, Arrhenatherum elatius, Artemisia annua, Artemisia vulgaris, Artemisia leucophylla, Cannabis sativa, and Chenopodium album. A. artemisiifolia was more likely to show co-occurrence with closely related species. Overall, 53.85% of the above indicator native species with high co-occurrence were widely distributed in the potential suitable areas for A. artemisiifolia in Xinjiang. Globally, the species with the highest occurrence belonged to the genera Chenopodium (58%), Bromus, Poa, Setaria, and Trifolium (>40%). Therefore, native species with the strong association and phylogenetic distant relationship to A. artemisiifolia can be employed as indicators for rapid and accurate monitoring in semi-arid areas.

Introduction

Alien plant invasion can be roughly divided into three stages: introduction, colonization, and naturalization (Radosevich, 2007). Accurate monitoring at an early stage is essential for immediate detection and effective prevention and control of invasive plants. At present, the monitoring of alien invasive plants relies mainly on inefficient manual large-scale screening (Richter et al., 2013). Although hyperspectral data monitoring has been proposed as an alternative, the corresponding results are strongly affected by source data and model accuracy, on top of elevated operational costs (Thamaga and Dube, 2018; Al-Lami et al., 2021). Because the early invasive population is difficult to spot due to low density and patchy or sporadic distribution, attempts should focus on rapid, efficient, and low-cost invasive species monitoring technology in the early stage.

The growth and distribution of invasive plants depend on the environment. Understanding habitat requirements and species distribution is essential for the successful monitoring and effective control of alien species (Hauser and McCarthy, 2009; Giljohann et al., 2011). Although the introduction and diffusion of alien species are random and the habitats they colonize are very diverse, interactions with abiotic and biotic factors will define a preference for certain habitats, especially during establishment and population expansion (Hejda et al., 2015; Andelkovic et al., 2022). At a local scale, habitat type is the best predictor of plant invasion, trumping the importance of propagule pressure and climate (Chytrý et al., 2008a,b, 2009). Therefore, it is crucial to identify suitable or preferred habitat characteristics of alien species, and conduct a census in these habitats to enable rapid monitoring.

Interaction with native species plays an important role for individual survival and population growth of invasive plants, overcoming the constraints of abiotic factors and propagule pressure (Thomaz and Michelan, 2011; Waller et al., 2016). On the one hand, alien species usually show positive interspecific associations with widespread native species in specific habitats (Fridley et al., 2007; Lei et al., 2018). On the other hand, Darwin noted how the relationship between alien and native species affected the successful naturalization of the former (Darwin, 1929). According to this simple methodological framework, the relationship between alien and native species can be used to predict which species are prone to invasion in which ecosystems (Procheş et al., 2010).

Furthermore, regular changes to interspecific associations and kinship between invasive and native species could potentially define some general rules governing specific invasion trends, leading to common indicator species. These could be employed as search tools for alien species in targeted rapid monitoring.

The invasive annual herbaceous species Ambrosia artemisiifolia has become a global problem, particularly in Europe and China. Crop yields are reduced in the invaded areas, and the large amount of pollen produced is harmful to human health (Essl et al., 2015; Hamaoui-Laguel, 2018). A. artemisiifolia is strongly competitive. When exposed to water and nitrogen stress, it responds by adjusting biomass allocation and by making other phenotypic plasticity changes, which makes it highly adaptable to habitats likely to be invaded (Leskovšek et al., 2012a,b). This species, thus, has a wide range of suitable habitat types, including croplands, transportation corridors, wastelands, and riparian areas (Montagnani et al., 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to identify the preferred habitats of A. artemisiifolia and then use indicator species to rapidly and effectively monitor these habitats to carry out prevention and control as early as possible.

Ambrosia artemisiifolia is widely distributed in northeast, north, and south China (Feng et al., 2012; Xing, 2012; Liu, 2019). Previously, we found that Yili Valley, located in the arid and semi-arid Xinjiang Province of China, was first invaded by A. artemisiifolia in 2010 (Dong et al., 2020). In this study, we investigated the community invaded by A. artemisiifolia in the Yili Valley to identify the preferred habitat of this species in semi-arid regions. Moreover, we evaluated the interspecific associations between A. artemisiifolia and native species in each invasive habitat, as well as the corresponding phylogenetic relationship. Finally, we used this information to determine whether the indicator species of Yili Valley could be employed as universal predictors for all of Xinjiang and global distribution areas of A. artemisiifolia. As an overall objective, this study is expected to aid the rapid monitoring of A. artemisiifolia in semi-arid areas.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Yili Valley (42°14′–44°53′N, 80°09′–84°56′E) lies in the westernmost part of the Tianshan Mountain Range of Xinjiang. The Valley comprises 56,400 km2, and has a continental temperate arid climate. The region has an average annual temperature of 10.4°C and precipitation of 417.6 mm. In grassland habitats, which represent the wettest area in Yili River, precipitation can reach 500 mm annually. The Yili Valley, with its rich plant diversity and extensive seed dispersal via canals, cattle, sheep, and tourists, provides favorable conditions for the invasion and rapid spread of alien species (Jia et al., 2011).

Experimental design and statistical analysis

Habitat investigation and sample setup of Ambrosia artemisiifolia invasion

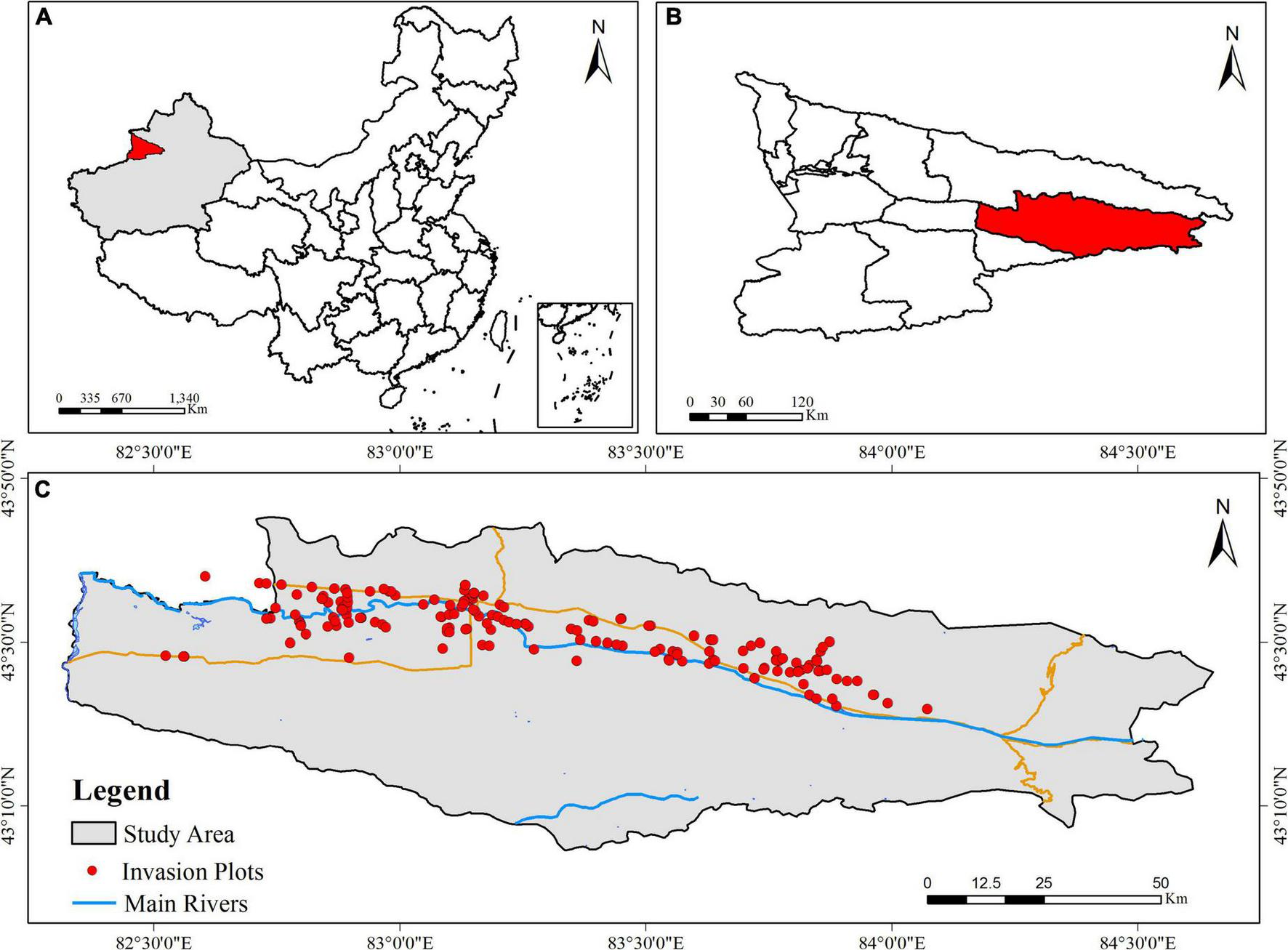

In August 2020, all communities at the initial stage of invasion by A. artemisiifolia (≤20% population coverage) were surveyed (Fenesi et al., 2015). Each invasive community was considered an invasion point, which was demarcated by latitude and longitude based on GPS data, as well as by habitat type (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Distribution points of Ambrosia artemisiifolia invasion communities in the study area. (A) The semi-arid regions Xinjiang is located in northwest of China. (B) The Yili Valley is located in northwest of Xinjiang. (C) Study area in the Yili Valley.

Observation plots were set up in the areas of A. artemisiifolia distribution within each habitat. Continuous or discontinuous 2 m × 2 m squares were used to cover the distribution of A. artemisiifolia. Species frequency was defined as the number of squares with a particular species/total number of squares × 100%. After the species frequency calculation of a certain habitat samples was completed, the species frequency of all samples in the habitat were regarded as repeated, and the mean and standard deviation were calculated as the species frequency of the habitat type.

There were some alien species (such as Conyza canadensis) that, according to our observations, were successfully naturalized in the study area. These species did not cause harm, and their distribution was stable and common. Therefore, we considered these as native species during our statistical analysis.

For species that could not be accurately identified in the field, plants were collected and identified in the laboratory. Growth forms and species taxonomy were identified according to descriptions in the Flora of China (Chinese Academy of Sciences Flora of China Editorial, 1998), Flora of Xinjiang (Editorial Committee of Xinjiang Flora, 1992–2011).

Interspecific associations between Ambrosia artemisiifolia and native species in the Yili Valley

Interspecific association reflects the coexistence of two species. A strong interspecific association indicates that ecological demand and habitat selection of A. artemisiifolia and native species have strong convergence and divergence. The χ2 statistic, association coefficient (AC), percentage of co-occurrence (PC), Ochiai index (OI), and dice index (DI) were used to determine the associations and co-occurrence probability between A. artemisiifolia and native species. To avoid bias introduced by rare species, taxa with a frequency < 10% were excluded from the analysis.

A 2 × 2 contingency table was constructed to show the coexistence interspecific associations between A. artemisiifolia and native species. The significance of interspecific associations were assessed by chi-square tests with Yates correction as follows:

Each A. artemisiifolia invasion point was taken as the unit of calculation, with N representing the total number of A. artemisiifolia invasion points, a the number of points in which two species co-occurred, b and c the number of points in which only one species occurred, and d the number of points in which none of the species occurred. For n = 1 degrees of freedom, the interspecific association of each species pair was non-significant if χ2 < 3.841 (P > 0.05), significant if 3.841 < χ2 < 6.635 (0.01 < P < 0.05), and highly significant if χ2 > 6.635 (P < 0.01). A positive association was indicated if ad > bc, and a negative association was indicated if ad < bc. The χ2 statistic could objectively and accurately reflect the significance of association between species pairs, but it could not quantify the closeness of this association.

The AC can further reflect the degree of interspecific associations, but it tends to exaggerate the significance of such associations in the absence of both species. The AC is calculated as follows:

The AC range is [−1, 1], and the closer it is to 1, the stronger is the positive association between species; whereas a value close to −1 indicates a strong negative association. AC = 0 indicates complete independence between species.

The PC reflects the degree of positive association between species, but tends to exaggerate the role of a, b, and c in the determination of association. The formula is PC = a/(a+b+c). The PC range is [0, 1]; the closer the value is to 1, the higher is the degree of positive connection, and the more likely two species are to appear or not together. Consequently, the ecological habitats and environmental requirements of the two species become more consistent.

The OI and DI can accurately reflect the probability and degree of association between different species pairs, and overcome the deviation caused by the large influence of d on the point AC. They are calculated as follows:

The range of these two indices is [0, 1]; the closer either of them is to 1, the higher is the degree of positive association between species pairs, and the higher is the probability of co-occurrence.

Phylogenetic relationship between Ambrosia artemisiifolia and native species in the Yili Valley

The PhyloMaker package in R was used to generate a phylogenetic tree framework, with the phylogenetic clade based on the APG classification system. The latter was done after the list of all families and species obtained from the survey was corrected in R 4.1.3 The phylogenetic distance (PD) between the invader and resident species in a recipient community was used as a metrics to represent their phylogenetic relatedness (Feng and Fu, 2008; Tretyakova et al., 2021). PD values were calculated uniformly for all indigenous species, regardless of habitat, using the picante package in R.

Distribution and representativeness of indicator species from the Yili Valley in potential suitable areas of Xinjiang

The classification of potential suitable areas of A. artemisiifolia plays an important role in early warning and effective monitoring. Through the Maxent model, Ma et al. (2020) used environmental factors, including climate data (precipitation and temperature); soil data; land use data; and altitude, slope, and aspect data, to identify the 13 areas listed in this study that are potentially suitable for A. artemisiifolia. The Flora of Xinjiang (Editorial Committee of Xinjiang Flora, 1992–2011) was consulted to check whether indicator species from the Yili Valley were distributed in all potential suitable areas for A. artemisiifolia in Xinjiang, and their proportion was calculated. Determining whether the main habitat types of the species recorded in the Flora were similar to those of indicator species could attest to the universality and representativeness of such species across Xinjiang.

Prevalence and representation of indicator and native species of the Yili Valley in major invasive areas of Ambrosia artemisiifolia across the world

To assess the difference and similarity of species composition between indicator species in the Yili Valley and native species in the main worldwide invasion areas of A. artemisiifolia, we search the literatures of associated species in the world’s recorded A. artemisiifolia distribution areas and count the native species present in the literatures (Igrc et al., 1995; Song and Prots, 1998; Makra et al., 2005; Brandes and Nitzsche, 2006; Fumanal et al., 2006; Essl et al., 2009; Gajnik and Peternel, 2009; Galzina et al., 2010; Patracchini and Ferrero, 2011; Puc and Wolski, 2013; Csontos et al., 2015; Gentili et al., 2016; Romain et al., 2016; Abramova, 2018; Chadaeva et al., 2018; Mang et al., 2018; Gusev, 2019; Petrova, 2019; Pinke et al., 2019).

To prevent discrepancies arising from different classification methods, the genera of recorded species were used to calculate the number of references for the occurrence of a species (i.e., the occurrence frequency of the species relative to the total number of references, which was 19). By arranging the frequency of each species, the similarity between the identified indicator species and the associated species of A. artemisiifolia was determined. This calculation defined the universality and representativeness of the species in present global distribution areas of A. artemisiifolia.

Results

Habitat types and species composition of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in the Yili Valley

A total of 186 invasion sites of A. artemisiifolia in the Yili Valley were cataloged. The invasive communities encompassed six habitat types: road margins (52), forest (40), farmland (36), wasteland (23), residential area (20), and grassland (15). A. artemisiifolia could not be found in other habitats, suggesting clear habitat preference for invasion.

Composition and distribution frequency of native species were similar across all habitats (Table 1). Specifically, 17 species were common in all habitats; they accounted for 60.71% of grassland species, 53.13% of farmland species, 56.67% of forest species, 60.71% of road margins species, 77.27% of residential area species, and 80.95% of wasteland species.

TABLE 1

| Habitat types | Species | Frequency/% | Species | Frequency/% | Species | Frequency/% | Species | Frequency/% |

| Grassland | Poa annua | 100 ± 0 | Cannabis sativa | 70 ± 16.12 | Artemisia vulgaris | 60 ± 10.12 | Achnatherum splendens | 33.33 ± 18.86 |

| Setaria viridis | 98.18 ± 5.75 | Trifolium | 70 ± 10 | Eragrostis pilosa | 60 ± 0 | Arctium lappa | 20 ± 0 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 90 ± 10 | Plantago asiatica | 70 ± 10 | Lagedium sibiricum | 60 ± 0 | Phragmites australis | 20 ± 0 | |

| Eleusine indica | 85 ± 16.58 | Artemisia annua | 67.27 ± 15.43 | Geranium wilfordii | 53.33 ± 9.43 | Carduus nutans | 20 ± 0 | |

| Medicago sativa | 80 ± 0 | Artemisia leucophylla | 67.27 ± 15.43 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 50 ± 10 | Achillea millefolium | 20 ± 0 | |

| Sonchus oleraceus | 80 ± 0 | Festuca elata | 60 ± 14.14 | Xanthium sibiricum | 44 ± 8 | |||

| Conyza canadensis | 75 ± 8.66 | Elymus dahuricus | 60 ± 0 | Daucus carota | 40 ± 0 | |||

| Chenopodium album | 70 ± 15.27 | Cirsium japonicum | 60 ± 0 | Lepidium apetalum | 40 ± 0 | |||

| Farmland | Bromus japonicus | 88.7 ± 17.52 | Conyza canadensis | 56 ± 8 | Medicago sativa | 46.67 ± 9.43 | Sonchus oleraceus | 30 ± 10 |

| Polygonum aviculare | 80 ± 21.91 | Artemisia vulgaris | 56 ± 7.12 | Sonchus oleraceus | 46.67 ± 24.94 | Phragmites australis | 30 ± 10 | |

| Setaria viridis | 79.2 ± 16.47 | Festuca elata | 50 ± 3 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 40 ± 0 | Abutilon theophrasti | 26.67 ± 9.43 | |

| Artemisia annua | 67.14 ± 9.58 | Echinochloa crus-galli | 48.57 ± 14.57 | Xanthium sibiricum | 36 ± 8 | Achnatherum splendens | 20 ± 0 | |

| Trifolium | 64 ± 23.32 | Plantago asiatica | 48 ± 9.8 | Geum aleppicum | 33.33 ± 9.43 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | 20 ± 0 | |

| Eleusine indica | 64 ± 19.6 | Arrhenatherum elatius | 48 ± 20.4 | Cannabis sativa | 32.31 ± 14.76 | Arctium lappa | 20 ± 0 | |

| Chenopodium album | 57.5 ± 6.61 | Geranium wilfordii | 48 ± 9.8 | Lagedium sibiricum | 30 ± 10 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 20 ± 0 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 56.5 ± 7.23 | Eragrostis pilosa | 46.67 ± 9.43 | Polygonum plebeium | 30 ± 10 | Galium paradoxum | 20 ± 0 | |

| Forest | Bromus japonicus | 97.33 ± 6.8 | Chenopodium album | 69.33 ± 14.36 | Sonchus oleraceus | 60 ± 0 | Xanthium sibiricum | 36.36 ± 11.5 |

| Setaria viridis | 87.5 ± 13.92 | Plantago asiatica | 67.06 ± 16.72 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 55 ± 8.66 | Polygonum plebeium | 35 ± 16.58 | |

| Conyza canadensis | 87.5 ± 9.68 | Artemisia leucophylla | 65.56 ± 16.06 | Festuca elata | 53.33 ± 9.42 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 35 ± 8.66 | |

| Geranium wilfordii | 80 ± 16.33 | Artemisia vulgaris | 62.14 ± 16.31 | Melilotus officinalis | 50 ± 10 | Arctium lappa | 33.33 ± 9.43 | |

| Poa annua | 80 ± 0 | Medicago sativa | 60 ± 12.65 | Elymus dahuricus | 50 ± 10 | Cirsium japonicum | 30 ± 10 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 76 ± 23.32 | Echinochloa crus-galli | 60 ± 12.65 | Cannabis sativa | 48.75 ± 14.09 | Daucus carota | 26.67 ± 9.43 | |

| Eleusine indica | 73.33 ± 9.43 | Eragrostis pilosa | 60 ± 0 | Sophora alopecuroides | 40 ± 0 | Achnatherum splendens | 20 ± 0 | |

| Trifolium | 71.67 ± 15.18 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | 60 ± 16.33 | Phragmites australis | 38.33 ± 9.86 | Urtica fissa | 20 ± 0 | |

| Road margins | Sophora alopecuroides | 96.67 ± 7.45 | Chenopodium album | 81.43 ± 15.97 | Artemisia annua | 62 ± 16.61 | Lagedium sibiricum | 48.57 ± 9.9 |

| Geranium wilfordii | 93.33 ± 9.43 | Eragrostis pilosa | 80 ± 14.14 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 60 ± 20 | Arctium lappa | 41.67 ± 9.86 | |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 92.65 ± 9.64 | Festuca elata | 80 ± 17.89 | Artemisia leucophylla | 56 ± 15 | Polygonum hydropiper | 40 ± 0 | |

| Setaria viridis | 91.74 ± 12.91 | Juncus bufonius | 80 ± 28.28 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 56 ± 15 | Daucus carota | 40 ± 0 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 90 ± 19.15 | Trifolium | 74.29 ± 11.78 | Sonchus oleraceus | 54.29 ± 9.04 | Achnatherum splendens | 26.67 ± 9.43 | |

| Eleusine indica | 90 ± 17.32 | Plantago asiatica | 69.41 ± 19.55 | Artemisia vulgaris | 52 ± 9.8 | |||

| Echinochloa crus-galli | 82.86 ± 7 | Medicago sativa | 67.27 ± 17.63 | Phragmites australis | 52 ± 9.8 | |||

| Conyza canadensis | 82.22 ± 17.5 | Cannabis sativa | 63.08 ± 18.14 | Xanthium sibiricum | 49.41 ± 15.52 | |||

| Residential area | Setaria viridis | 97.89 ± 6.14 | Polygonum aviculare | 93.75 ± 9.27 | Geranium wilfordii | 60 ± 20 | Melilotus officinalis | 42.86 ± 9.43 |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 97.5 ± 6.61 | Eleusine indica | 90 ± 10 | Medicago sativa | 57.5 ± 12 | Sonchus oleraceus | 40 ± 0 | |

| Echinochloa crus-galli | 96 ± 8 | Chenopodium album | 84 ± 15 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 52 ± 9.8 | Achnatherum splendens | 33.33 ± 9.43 | |

| Conyza canadensis | 95 ± 8.66 | Cannabis sativa | 80 ± 16.33 | Xanthium sibiricum | 50 ± 10 | |||

| Residential area | Artemisia leucophylla | 95 ± 8.66 | Trifolium | 77.5 ± 21.07 | Arctium lappa | 46.67 ± 9.43 | ||

| Artemisia annua | 95 ± 8.66 | Plantago asiatica | 61.82 ± 13.36 | Cirsium japonicum | 46.67 ± 9.43 | |||

| Wasteland | Setaria viridis | 98.1 ± 5.87 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 90 ± 9.27 | Plantago asiatica | 57.78 ± 11.33 | Xanthium sibiricum | 42.5 ± 6.61 |

| Eleusine indica | 98 ± 6 | Conyza canadensis | 80 ± 16.33 | Artemisia vulgaris | 50 ± 10 | Arctium lappa | 40 ± 0 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 96 ± 8 | Festuca elata | 80 ± 16.33 | Phragmites australis | 50 ± 10 | Cirsium japonicum | 33.33 ± 9.43 | |

| Trifolium | 96 ± 8 | Chenopodium album | 77.5 ± 21.07 | Sonchus oleraceus | 50 ± 10 | |||

| Geranium wilfordii | 95 ± 8.66 | Artemisia annua | 63.08 ± 17.27 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 46.67 ± 9.43 | |||

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 93.75 ± | Cannabis sativa | 60 ± 18.52 | Polygonum hydropiper | 46.67 ± 9.43 |

Distribution frequency (Mean ± SD) of native species in Ambrosia artemisiifolia invasive communities in the Yili Valley.

The most frequent grass species were Setaria viridis, Poa annua, Bromus spp., Arrhenatherum elatius, Echinochloa crus-galli, Eleusine indica, and some Artemisia species. Other common species were Chenopodium album, Plantago asiatica, C. canadensis, Cannabis sativa, and Trifolium spp. These results pointed to similar species composition and distribution in the habitats invaded by A. artemisiifolia (Table 1).

Interspecific associations between Ambrosia artemisiifolia and native species

No significant interspecific association between A. artemisiifolia and native species could be detected in all habitats. S. viridis, P. annua, and Bromus spp. correlated positively with A. artemisiifolia in all habitats; whereas A. elatius did so only in road margins, residential areas, and wasteland. Artemisia annua, Artemisia vulgaris, and Artemisia leucophylla showed similar association characteristics and were positively associated with A. artemisiifolia in all habitats. Instead, C. sativa exhibited positive association with A. artemisiifolia in farmland and grassland, but a negative association in other habitats. A negative association was observed also between C. album and A. artemisiifolia in all habitats (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Habitat types | Species | AC | Species | AC | Species | AC | Species | AC |

| Grassland | Poa annua | 0.346 | Xanthium sibiricum | –0.227 | Trifolium | –0.393 | Achillea millefolium | –0.433 |

| Setaria viridis | 0.292 | Eleusine indica | –0.292 | Elymus dahuricus | –0.393 | Eragrostis pilosa | –0.433 | |

| Artemisia annua | 0.292 | Festuca elata | –0.292 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.393 | Arctium lappa | –0.433 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 0.292 | Conyza canadensis | –0.292 | Plantago asiatica | –0.393 | Cirsium japonicum | –0.433 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 0.292 | Medicago sativa | –0.292 | Daucus carota | –0.433 | Phragmites australis | –0.433 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 0.227 | Lagedium sibiricum | –0.346 | Carduus nutans | –0.433 | |||

| Chenopodium album | –0.15 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.346 | Lepidium apetalum | –0.433 | |||

| Polygonum aviculare | –0.227 | Achnatherum splendens | –0.346 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.433 | |||

| Farmland | Setaria viridis | 0.462 | Echinochloa crus-galli | –0.3 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | –0.391 | Festuca elata | –0.44 |

| Bromus japonicus | 0.417 | Polygonum aviculare | –0.364 | Achnatherum splendens | –0.391 | Lagedium sibiricum | –0.44 | |

| Artemisia annua | 0.067 | Trifolium | –0.364 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.413 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.44 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 0.067 | Eleusine indica | –0.364 | Medicago sativa | –0.413 | Polygonum plebeium | –0.44 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 0.067 | Plantago asiatica | –0.364 | Eragrostis pilosa | –0.413 | Phragmites australis | –0.44 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 0.067 | Arrhenatherum elatius | –0.364 | Geum aleppicum | –0.413 | Galium paradoxum | –0.44 | |

| Xanthium sibiricum | –0.176 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.364 | Abutilon theophrasti | –0.413 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.44 | |

| Chenopodium album | –0.263 | Conyza canadensis | –0.364 | Arctium lappa | –0.413 | Taraxacum mongolicum | –0.462 | |

| Forest | Setaria viridis | 0.439 | Trifolium | –0.29 | Taraxacum mongolicum | –0.422 | Festuca elata | –0.439 |

| Poa annua | 0.403 | Phragmites australis | –0.229 | Cirsium japonicum | –0.422 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | –0.439 | |

| Bromus japonicus | 0.383 | Xanthium sibiricum | –0.26 | Achnatherum splendens | –0.422 | Eragrostis pilosa | –0.456 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 0.026 | Conyza canadensis | –0.339 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.422 | Melilotus officinalis | –0.456 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 0.026 | Arctium lappa | –0.383 | Polygonum plebeium | –0.422 | Urtica fissa | –0.456 | |

| Plantago asiatica | –0.026 | Echinochloa crus-galli | –0.403 | Eleusine indica | –0.439 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.456 | |

| Cannabis sativa | –0.075 | Polygonum aviculare | –0.403 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.439 | Elymus dahuricus | –0.456 | |

| Chenopodium album | –0.119 | Medicago sativa | –0.403 | Daucus carota | –0.439 | Sophora alopecuroides | –0.456 | |

| Road margins | Arrhenatherum elatius | 0.45 | Chenopodium album | –0.313 | Taraxacum mongolicum | –0.402 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.461 |

| Setaria viridis | 0.415 | Trifolium | –0.313 | Echinochloa crus-galli | –0.415 | Juncus bufonius | –0.461 | |

| Artemisia annua | 0.113 | Eleusine indica | –0.345 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.415 | Achnatherum splendens | –0.461 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 0.113 | Polygonum aviculare | –0.345 | Lagedium sibiricum | –0.415 | Daucus carota | –0.471 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 0.113 | Arctium lappa | –0.345 | Sophora alopecuroides | –0.427 | Polygonum hydropiper | –0.481 | |

| Cannabis sativa | –0.018 | Medicago sativa | –0.36 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.439 | |||

| Plantago asiatica | –0.257 | Phragmites australis | –0.375 | Eragrostis pilosa | –0.45 | |||

| Xanthium sibiricum | –0.257 | Conyza canadensis | –0.389 | Festuca elata | –0.45 | |||

| Residential area | Setaria viridis | 0.364 | Phragmites australis | –0.222 | Achnatherum splendens | –0.364 | Cirsium japonicum | –0.417 |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 0.3 | Trifolium | –0.222 | Conyza canadensis | –0.364 | Medicago sativa | –0.417 | |

| Artemisia annua | 0.125 | Xanthium sibiricum | –0.3 | Eleusine indica | –0.364 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.417 | |

| Residential area | Artemisia leucophylla | 0.125 | Echinochloa crus-galli | –0.3 | Polygonum aviculare | –0.364 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.417 |

| Cannabis sativa | 0 | Plantago asiatica | –0.3 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.364 | |||

| Chenopodium album | –0.125 | Melilotus officinalis | –0.3 | Arctium lappa | –0.364 | |||

| Wasteland | Setaria viridis | 0.405 | Chenopodium album | –0.219 | Geranium wilfordii | –0.375 | Taraxacum mongolicum | –0.432 |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 0.265 | Xanthium sibiricum | –0.219 | Trifolium | –0.375 | Sonchus oleraceus | –0.432 | |

| Artemisia annua | 0.107 | Cannabis sativa | –0.265 | Festuca elata | –0.405 | Arctium lappa | –0.432 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 0.107 | Conyza canadensis | –0.306 | Polygonum hydropiper | –0.405 | |||

| Eleusine indica | –0.107 | Phragmites australis | –0.342 | Polygonum lapathifolium | –0.405 | |||

| Plantago asiatica | –0.167 | Polygonum aviculare | –0.342 | Cirsium japonicum | –0.405 |

Association coefficient (AC) between native species and Ambrosia artemisiifolia invasive habitat community in the Yili Valley.

The PC of A. artemisiifolia and native species in different habitats was above 50% and reached up to 96.2% for S. viridis, P. annua, Bromus spp., A. annua, A. vulgaris, and A. leucophylla in all habitats. The PC of A. elatius in road margin, residential area, and wasteland habitats were above 60%, with a peak of 95.2%. Except for wasteland, the OI and DI values of C. sativa surpassed 60% in all habitats; whereas those of C. album were greater than 50% in all habitats (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Habitat types | Species | PC | OI | DI | Species | PC | OI | DI | Species | PC | OI | DI |

| Grassland | Poa annua | 75 | 85.9 | 85.7 | Festuca elata | 25 | 46.2 | 40 | Daucus carota | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 |

| Setaria viridis | 68.8 | 82 | 81.5 | Conyza canadensis | 25 | 46.2 | 40 | Carduus nutans | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Artemisia annua | 68.8 | 82 | 81.5 | Medicago sativa | 25 | 46.2 | 40 | Lepidium apetalum | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 68.8 | 82 | 81.5 | Lagedium sibiricum | 18.8 | 38.7 | 31.6 | Sonchus oleraceus | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 68.8 | 82 | 81.5 | Geranium wilfordii | 18.8 | 38.7 | 31.6 | Achillea millefolium | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 62.5 | 77.8 | 76.9 | Achnatherum splendens | 18.8 | 38.7 | 31.6 | Eragrostis pilosa | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Chenopodium album | 37.5 | 58.6 | 54.5 | Trifolium | 12.5 | 29.8 | 22.2 | Arctium lappa | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 31.3 | 52.7 | 47.6 | Elymus dahuricus | 12.5 | 29.8 | 22.2 | Cirsium japonicum | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Xanthium sibiricum | 31.3 | 52.7 | 47.6 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 12.5 | 29.8 | 22.2 | Phragmites australis | 6.3 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Eleusine indica | 25 | 46.2 | 40 | Plantago asiatica | 12.5 | 29.8 | 22.2 | |||||

| Farmland | Setaria viridis | 92.6 | 96.2 | 96.2 | Eleusine indica | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Abutilon theophrasti | 14.8 | 35.1 | 25.8 |

| Bromus japonicus | 85.2 | 92.1 | 92 | Plantago asiatica | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Arctium lappa | 14.8 | 35.1 | 25.8 | |

| Artemisia annua | 51.9 | 70.9 | 68.3 | Arrhenatherum elatius | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Festuca elata | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 51.9 | 70.9 | 68.3 | Geranium wilfordii | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Lagedium sibiricum | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 51.9 | 70.9 | 68.3 | Conyza canadensis | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Sonchus oleraceus | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 51.9 | 70.9 | 68.3 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | 18.5 | 40 | 31.3 | Polygonum plebeium | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Xanthium sibiricum | 48.1 | 68.1 | 65 | Achnatherum splendens | 18.5 | 40 | 31.3 | Phragmites australis | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Chenopodium album | 33.3 | 55.8 | 50 | Sonchus oleraceus | 18.5 | 40 | 31.3 | Galium paradoxum | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Echinochloa crus-galli | 29.6 | 52.3 | 45.7 | Medicago sativa | 14.8 | 35.1 | 25.8 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 11.1 | 29.4 | 20 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Eragrostis pilosa | 14.8 | 35.1 | 25.8 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 7.4 | 22.6 | 13.8 | |

| Trifolium | 25.9 | 48.5 | 41.2 | Geum aleppicum | 14.8 | 35.1 | 25.8 | |||||

| Forest | Setaria viridis | 88.9 | 94.2 | 94.1 | Conyza canadensis | 16.7 | 38.3 | 28.6 | Geranium wilfordii | 5.6 | 19.5 | 10.5 |

| Poa annua | 83.3 | 91.1 | 90.9 | Arctium lappa | 13.9 | 34.5 | 24.4 | Daucus carota | 5.6 | 19.5 | 10.5 | |

| Bromus japonicus | 62.5 | 77.8 | 76.9 | Echinochloa crus-galli | 11.1 | 30.2 | 20 | Festuca elata | 5.6 | 19.5 | 10.5 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 50 | 69.8 | 66.7 | Polygonum aviculare | 11.1 | 30.2 | 20 | Chrysopogon aciculatus | 5.6 | 19.5 | 10.5 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 47.2 | 69.8 | 66.7 | Medicago sativa | 11.1 | 30.2 | 20 | Eragrostis pilosa | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Plantago asiatica | 47.2 | 67.7 | 64.2 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 8.3 | 25.4 | 15.4 | Melilotus officinalis | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 44.4 | 65.6 | 61.5 | Cirsium japonicum | 8.3 | 25.4 | 15.4 | Urtica fissa | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Chenopodium album | 41.7 | 63.4 | 58.8 | Achnatherum splendens | 8.3 | 25.4 | 15.4 | Sonchus oleraceus | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Trifolium | 33.3 | 56.3 | 50 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 8.3 | 25.4 | 15.4 | Elymus dahuricus | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Phragmites australis | 30.6 | 53.7 | 46.8 | Polygonum plebeium | 8.3 | 25.4 | 15.4 | Sophora alopecuroides | 2.8 | 12 | 5.4 | |

| Xanthium sibiricum | 22.2 | 45.1 | 36.4 | Eleusine indica | 5.6 | 19.5 | 10.5 | |||||

| Road margins | Arrhenatherum elatius | 90.7 | 95.2 | 95.1 | Eleusine indica | 22.2 | 45.7 | 36.4 | Sophora alopecuroides | 11.1 | 31.2 | 20 |

| Setaria viridis | 85.2 | 92.2 | 92 | Polygonum aviculare | 22.2 | 45.7 | 36.4 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 9.3 | 28 | 16.9 | |

| Artemisia annua | 55.6 | 74 | 71.4 | Arctium lappa | 22.2 | 45.7 | 36.4 | Eragrostis pilosa | 7.4 | 24.6 | 13.8 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 55.6 | 74 | 71.4 | Medicago sativa | 20.4 | 43.6 | 33.8 | Festuca elata | 7.4 | 24.6 | 13.8 | |

| Road margins | Artemisia leucophylla | 55.6 | 74 | 71.4 | Phragmites australis | 18.5 | 41.4 | 31.3 | Geranium wilfordii | 5.6 | 20.6 | 10.5 |

| Cannabis sativa | 48.1 | 68.7 | 65 | Conyza canadensis | 16.7 | 39.1 | 28.6 | Juncus bufonius | 5.6 | 20.6 | 10.5 | |

| Plantago asiatica | 31.5 | 55 | 47.9 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 14.8 | 36.6 | 25.8 | Achnatherum splendens | 5.6 | 20.6 | 10.5 | |

| Xanthium sibiricum | 31.5 | 55 | 47.9 | Echinochloa crus-galli | 13 | 34 | 23 | Daucus carota | 3.7 | 15.9 | 7.1 | |

| Chenopodium album | 25.9 | 49.7 | 41.2 | Sonchus oleraceus | 13 | 34 | 23 | Polygonum hydropiper | 1.9 | 9.7 | 3.6 | |

| Trifolium | 25.9 | 49.7 | 41.2 | Lagedium sibiricum | 13 | 34 | 23 | |||||

| Residential area | Setaria viridis | 76.9 | 87 | 87 | Xanthium sibiricum | 23.1 | 43.3 | 37.5 | Geranium wilfordii | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 69.2 | 82.2 | 81.8 | Echinochloa crus-galli | 23.1 | 43.3 | 37.5 | Arctium lappa | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | |

| Artemisia annua | 53.8 | 71.4 | 70 | Plantago asiatica | 23.1 | 43.3 | 37.5 | Cirsium japonicum | 7.7 | 20.4 | 14.3 | |

| Artemisia leucophylla | 53.8 | 71.4 | 70 | Melilotus officinalis | 23.1 | 43.3 | 37.5 | Medicago sativa | 7.7 | 20.4 | 14.3 | |

| Cannabis sativa | 46.2 | 65.5 | 63.2 | Achnatherum splendens | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 7.7 | 20.4 | 14.3 | |

| Chenopodium album | 38.5 | 58.9 | 55.6 | Conyza canadensis | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | Sonchus oleraceus | 7.7 | 20.4 | 14.3 | |

| Phragmites australis | 30.8 | 51.6 | 47.1 | Eleusine indica | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | |||||

| Trifolium | 30.8 | 51.6 | 47.1 | Polygonum aviculare | 15.4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | |||||

| Wasteland | Setaria viridis | 83.3 | 91 | 90.9 | Xanthium sibiricum | 33.3 | 55.6 | 50 | Festuca elata | 12.5 | 31.3 | 22.2 |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | 66.7 | 80.9 | 80 | Cannabis sativa | 29.2 | 51.6 | 45.2 | Polygonum hydropiper | 12.5 | 31.3 | 22.2 | |

| Artemisia annua | 54.2 | 72.4 | 70.3 | Conyza canadensis | 25 | 47.3 | 40 | Polygonum lapathifolium | 12.5 | 31.3 | 22.2 | |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 54.2 | 72.4 | 70.3 | Phragmites australis | 20.8 | 42.6 | 34.5 | Cirsium japonicum | 12.5 | 31.3 | 22.2 | |

| Eleusine indica | 41.7 | 62.9 | 58.8 | Polygonum aviculare | 20.8 | 42.6 | 34.5 | Taraxacum mongolicum | 8.3 | 24.1 | 15.4 | |

| Plantago asiatica | 37.5 | 59.3 | 54.4 | Geranium wilfordii | 16.7 | 37.3 | 28.6 | Sonchus oleraceus | 8.3 | 24.1 | 15.4 | |

| Chenopodium album | 33.3 | 55.6 | 50 | Trifolium | 16.7 | 37.3 | 28.6 | Arctium lappa | 8.3 | 24.1 | 15.4 |

Common percentages of native species and Ambrosia artemisiifolia invasive habitat communities in the Yili Valley.

Species in bold are indicator species.

Various native species and A. artemisiifolia showed different PC due to different habitats (Table 3). The PC of A. artemisiifolia and Xanthium sibiricum in farmland reached 68.1%, that of Bromus spp. in forest reached 77.8%, that of Trifolium reached 56.3%, that of E. indica in wasteland reached 68.1%, and that of P. asiatica reached 59.3%.

Phylogenetic relationship between Ambrosia artemisiifolia and its native companion species

The greatest PD (376.57 MA) was observed between A. artemisiifolia and species of the Gramineae family with elevated PC, such as S. viridis, P. annua, and Bromus spp. The PD between A. artemisiifolia and C. album, C. sativa, and Trifolium spp. increased over time, with the proportion of species showing a distant relationship being greater in the early stages of A. artemisiifolia invasion (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Phylogenetic distance between Ambrosia artemisiifolia (red-colored) and native species in the study area. Green-colored species are the indicator species present in all habitat types. Blue-colored species are indicator species that occur only in a particular habitat type.

Indicator species in the potential habitat of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in Xinjiang

Poa annua, C. album, Trifolium spp., and A. elatius are widespread in Xinjiang, and their distribution area covered 100% of the potential suitable areas of A. artemisiifolia in this region. The distribution of A. annua showed a 46.15% overlap with potential suitable areas of A. artemisiifolia in Xinjiang, including severe, moderate, and mildly suitable areas. The degree of overlap between A. artemisiifolia, Bromus spp., S. viridis, A. leucophylla, and P. asiatica was only 30.77%, decreasing further to 15.38% for C. sativa, X. sibiricum, and E. indica. Notably, the habitats defined by each indicator species were similar to the main habitat types in the suitable area, especially in farmland, forest, road margins, and wasteland (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Species | Suitable areas of major distribution | Proportion of suitable area/% | Habitat types in the suitable area |

| Setaria viridis | Wide distribution | 100 | Farmland, Wasteland, Road margins |

| Chenopodium album | Wide distribution | 100 | Farmland, Canal, Wasteland |

| Trifolium | Wide distribution | 100 | Valley, Forest |

| Arrhenatherum elatius | Wide distribution | 100 | Valley, Wasteland, Farmland, Road margins, Valley meadow |

| Artemisia annua | Tarbagatay, Bortala, Altay, Changji, Aksu, Hetian | 46.15 | Farmland, Hillside, Wasteland, Road margins |

| Artemisia vulgaris | Tarbagatay, Altay, Urumqi, Turpan, Kashgar | 38.46 | Grassland, Forest, Wasteland, Road margins |

| Bromus japonicus | Tarbagatay, Bortala, Altay, Urumqi, Shihezi | 38.46 | Farmland, Canal |

| Poa annua | Tarbagatay, Altay, Urumqi, Aksu | 30.77 | Valley, Forest, Farmland |

| Artemisia leucophylla | Altay, Urumqi, Aksu, Kashgar | 30.77 | Hillside, Forest, Valley, Road margins |

| Plantago asiatica | Bortala, Changji, Urumqi, Aksu | 30.77 | Upland meadow, Alpine meadow, Farmland, Canal |

| Cannabis sativa | Tarbagatay, Altay | 15.38 | Valley, Wasteland, Farmland |

| Xanthium sibiricum | Urumqi, Yili | 15.38 | Farmland, Road margins, Wasteland |

| Eleusine indica | Bortala, Tarbagatay | 15.38 | Farmland, Road margins, Wasteland |

Distribution of indicator species in potential suitable areas of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in Xinjiang.

The habitat type in bold is the same as that of the indicator species in Yili River Valley.

Representation of indicator species from the Yili Valley in global distribution areas of Ambrosia artemisiifolia

In terms of species composition, 13 families (72.22%), 31 genera (61.76%), and 22 species (39.29%) were shared between the native species of the Yili Valley and those of areas currently infested by A. artemisiifolia across the world (Table 5). Among them, species belonging to the Gramineae and Compositae families accounted for the largest share. These common species had a high frequency of distribution in the Yili Valley.

TABLE 5

| Genus | Frequency/% | Genus | Frequency/% | Genus | Frequency/% | Genus | Frequency/% |

| Chenopodium | 58.33 | Arrhenatherum | 25 | Potentilla | 16.67 | Datura | 8.33 |

| Medicago | 50 | Festuca | 25 | Arctium | 8.33 | Kochia | 8.33 |

| Bromus | 41.67 | Taraxacum | 25 | Capsella | 8.33 | Oenothera | 8.33 |

| Cirsium | 41.67 | Daucus | 25 | Sonchus | 8.33 | Anthoxanthum | 8.33 |

| Poa | 41.67 | Melilotus | 25 | Galinsoga | 8.33 | Crepis | 8.33 |

| Setaria | 41.67 | Amaranthus | 16.67 | Galium | 8.33 | Picris | 8.33 |

| Trifolium | 41.67 | Centaurea | 16.67 | Abutilon | 8.33 | Senecio | 8.33 |

| Lolium | 41.67 | Polygonum | 16.67 | Forsythia | 8.33 | Rubus | 8.33 |

| Achillea | 33.33 | Bellis | 16.67 | Pisum | 8.33 | Sanguisorba | 8.33 |

| Artemisia | 33.33 | Cichorium | 16.67 | Cynodon | 8.33 | Stellaria | 8.33 |

| Echinochloa | 33.33 | Potentilla | 16.67 | Carex | 8.33 | Hordeum | 8.33 |

| Lactuca | 33.33 | Juncus | 16.67 | Digitaria | 8.33 | Phleum | 8.33 |

| Convolvulus | 33.33 | Lotus | 16.67 | Viola | 8.33 | Calamagrostis | 8.33 |

| Conyza | 25 | Erigeron | 16.67 | Sorghum | 8.33 | ||

| Plantago | 25 | Xanthium | 16.67 | Arenaria | 8.33 |

Statistics of native species of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in the world distribution.

Among all indicator species, C. album had the highest frequency of occurrence (58%); whereas species belonging to the Bromus, Poa, Setaria, and Trifolium genera appeared more than 40% of the time (Table 5).

Discussion

Ambrosia artemisiifolia shows obvious habitat preference when invading a semi-arid area

The successful establishment of alien invasive species is determined by the fluctuation of abiotic environmental factors, propagule pressure, and the interaction between species (Pysek and Chytry, 2014). Habitat conditions play a fundamental role by influencing the invasion process and the composition of native species, thus defining the relationship between the latter and the invaders, as well as the spread and harm caused by these (Catford et al., 2012; Hejda et al., 2015).

Water is an important factor affecting species distribution. Indeed, precipitation contributes more than 50% to the potential distribution of A. artemisiifolia (Ma et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). Precipitation above 280 mm promoting growth and propagation of A. artemisiifolia. Precipitation in most areas of The Yili Valley is above 280 mm; while the average precipitation in Xinyuan County, where A. artemisiifolia is particularly abundant, is 417 mm (Dong et al., 2020). Therefore, in low-lying areas, such as grassland, farmland, and road margins, the water supply can meet the needs for germination, growth, and reproduction of A. artemisiifolia seeds, thereby ensuring successful settlement and population expansion. By simulating the effect of different precipitation levels on the growth of A. artemisiifolia, found that A. artemisiifolia was highly adaptable to drought (Leiblein and Lösch, 2011; Leskovšek et al., 2012a), explaining its widespread distribution in a habitat with little water such as wasteland. Temperature had no significant effect on the growth and distribution of A. artemisiifolia in the Yili Valley (Dong et al., 2020).

Although the habitats of A. artemisiifolia across the world are not exactly the same as those in this study, priority targeting of habitats preferentially invaded by A. artemisiifolia is the basis for rapid surveillance (Epanchin-Niell and Hastings, 2010). This study describes the habitats that may be preferred for invasion by A. artemisiifolia throughout the world.

The probability of co-occurrence between Ambrosia artemisiifolia and species with strong positive correlation and distant relationship is higher at the neighborhood scale

In this study, the invasive community of A. artemisiifolia was at the stage from establishment to population growth, and the association between A. artemisiifolia and other species were weak (Table 2). The lack of any significant association on the whole indicated that the current invasive community of A. artemisiifolia was in a dynamic succession process and had not yet stabilized (Liu et al., 2017). At this stage, interspecific competition was weak, meaning that native species ecologically similar to A. artemisiifolia, including S. viridis, P. annua, A. elatius, A. annua, A. vulgaris, A. leucophylla, C. sativa, and C. album, as well as other dominant native plants in the community, did not compete intensely for resources and exhibited a high PC (Lei et al., 2018).

At the same time, species related to A. artemisiifolia were detected in all habitats, indicating similar habitat selection and adaptation (Ozaslan et al., 2016). However, at the neighborhood scale (i.e., within the habitat sample in this study), the PC of A. artemisiifolia and other local related species, such as X. sibiricum., Arctium lappa, and C. canadensis, was below 50% and as low as 6.3% (Table 3). Only Artemisia species presented higher PC. All Asteraceae species accounted for a very small proportion of indicator species.

Darwin’s naturalization and pre-adaptation hypotheses need not be mutually exclusive. Phylogenetic similarity may be both close and distant in the same system, as it may vary across spatial scales and at different stages of invasion (Diez et al., 2008; Procheş et al., 2010; Cadotte et al., 2018; Tretyakova et al., 2021). At fine spatial scales (in relation to plant size), one can expect closely related organisms to exist in mutually exclusive patterns due to competitive interactions. Species less closely related to the local community are more likely to coexist by minimizing competitive exclusion (Maitner et al., 2021). Li et al. (2015) found that the probability of invader establishment declined with increasing PD between the invader and residents; whereas the average size of surviving invader individuals increased with PD. Because of their adaptability to environmental conditions, successfully established A. artemisiifolia became more closely related to the community during the invasion stage, but grew phylogenetically more distant over time, as they were striving to replace closely related native plants (Ma et al., 2016). These studies suggest that the Darwin’s pre-adaptation hypothesis is more applicable to large scales and early stages of establishment, while Darwin’s naturalization hypothesis is applicable to neighborhood scales and late growth stages, which is similar to our results.

Indicator species are universal and representative

This study found a similar species composition of invasive communities across different habitats (Table 1). Native species were present in all invasive habitats except for some species, such as Achillea millefolium, Sophora alopecuroides, and Melilotus spp., in residential areas, grassland, and forest. Among widely distributed native species, S. viridis, P. annua, A. elatius, A. annua, A. vulgaris, A. leucophylla, C. sativa, and C. album exhibited positive correlation with A. artemisiifolia in all habitats and a high PC (Tables 2, 3). These indicator species accounted for 33.33% of native species, whose distribution frequency was more than 50% in the grassland, 81.82% in the farmland, 42.86% in the forest, 26.09% in the road margins, 37.5% in the residential areas, and 37.5% in the wasteland. These species not only reflect the co-occurrence with A. artemisiifolia, but are also representative and universal in various habitats, as well as easy to locate and identify. In the same way, X. sibiricum in the farmland, Bromus in the forest, Trifolium in the wasteland, and P. asiatica are good indicators and representative of their respective habitats.

By comparing similarities between the distribution of indicator species in potential suitable areas of A. artemisiifolia in the Yili Valley and the main habitat types, we found that indicator species grew in all such areas. In Tarbagatay and Bortala, more than 80% of indicator species were present in each habitat. The Maxent model predicted that precipitation in these two areas could meet the demand of A. artemisiifolia (Ma et al., 2020). Grassland was the main habitat type in the potential distribution area within the Yili Valley. This suggests that the distribution of indicator species from the Yili Valley points to potential suitable areas of A. artemisiifolia throughout Xinjiang. Therefore, it is feasible to rapidly monitor A. artemisiifolia by targeting indicator species in preferred invasive habitats of semi-arid regions.

In this study, native species associated with A. artemisiifolia across the world were counted by genus, limiting the influence of taxonomic differences and distribution habitat heterogeneity on the results. Except for C. sativa, which appeared only in the Yili River Valley, other species were distributed in all areas invaded by A. artemisiifolia. Setaria, Bromus, Elytrigia, Artemisia, and other species presented a wide distribution range. These results provide guidance and a reference for the worldwide rapid monitoring of A. artemisiifolia invasion.

At the time of monitoring, the worldwide distribution of A. artemisiifolia, and the composition and distribution of native species varied across habitats. Additionally, habitats with indicator species may not necessarily contain A. artemisiifolia because of non-dispersal or unsuccessful establishment. However, our study provides a reference key for finding common dominant native species as monitoring clues for the preferred habitat of A. artemisiifolia invasion. This is particularly true of Chenopodium spp., whose PC was 58% in the presence of A. artemisiifolia and reached up to 63.4% in a forest habitat (Table 3). Such examples improve dramatically the surveillance at an early stage of the invasion process, thereby facilitating prevention and control efforts.

Conclusion

In semi-arid areas, the preferred habitat of A. artemisiifolia and the transmission channel to surrounding areas can be accurately monitored by looking at the indicator species, i.e., dominant native species with strong correlation and distant phylogenetic relationship to A. artemisiifolia. Building on the potential suitable areas for A. artemisiifolia predicted by the Maxent model, this study provides clues for improved monitoring of this invasive species, thus reducing costs. All A. artemisiifolia found during monitoring should be removed in a timely manner to prevent the species from quickly forming dense populations and causing further harm.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

WZ conceived this study, performed data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. MS, HW, XL, and PS collected data of this study. TL led and coordinated the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Science and Technology Project of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No. 2022AB010) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31770461).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AbramovaL. M. (2018). Distribution of invasive species of Ambrosia L. genus in the south urals (Republic of Bashkortostan).Russ. J. Biol. Invasions91–8. 10.1134/S2075111718010022

2

Al-LamiA. K.AbboodR. A.MalikiA.Al-AnsariN. (2021). Using vegetation indices for monitoring the spread of nile rose plant in the tigris river within wasit province, Iraq.Remote Sensing Appl. Soc. Environ.22:100471. 10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100471

3

AndelkovicA.PavlovicD.MarisavljevicD.ZivkovicM.NovkovicM.PopovicS.et al (2022). Plant invasions in riparian areas of the middle danube basin in serbia.NeoBiota7123–48. 10.3897/neobiota.71.69716

4

BrandesD.NitzscheJ. (2006). Biology, introduction, dispersal, and distribution of common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) with special regard to Germany Biologie, Einschleppung, Ausbreitung und Verbreitung der Beifublttrigen Ambrosie (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) unter besonderer.Nachrichtenblatt des Deutschen Pflanzenschutzdienstes58286–291.

5

CadotteM. W.CampbellS. E.LiS. P.SodhiD. S.MandrakN. E. (2018). Preadaptation and naturalization of nonnative species: darwin’s two fundamental insights into species invasion.Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.69661–684. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040339

6

CatfordJ. A.VeskP. A.RichardsonD. M.PyšekP. (2012). Quantifying levels of biological invasion: towards the objective classification of invaded and invasible ecosystems.Global Change Biol.1844–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02549.x

7

ChadaevaV. A.ShhagapsoevaK. A.TsepkovaN. L.ShhagapsoevS. H. (2018). Monitoring of ambrosia artemisiifolia l. distribution in meadow phytocenoses of kabardino-balkarian republic (Central Caucasus).Russ. J. Biol. Invasions9195–203. 10.1134/S2075111718020030

8

Chinese Academy of Sciences Flora of China Editorial (1998). Flora of China.Beijing: Science Press.

9

ChytrýM.JarošíkV.PyšekP.HájekO.KnollováI.TichýL.et al (2008a). Separating habitat invasibility by alien plants from the actual level of invasion.Ecology891541–1553. 10.1890/07-0682.1

10

ChytrýM.MaskellL. C.PinoJ.PyšekP.VilàM.FontX.et al (2008b). Habitat invasions by alien plants: a quantitative comparison among mediterranean, subcontinental and oceanic regions of Europe.J. Appl. Ecol.45448–458. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01398.x

11

ChytrýM.PyšekP.WildJ.PinoJ.MaskellL. C.VilàM. (2009). European map of alien plant invasions based on the quantitative assessment across habitats.Diversity Distribut.1598–107. 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00515.x

12

CsontosP.AngyalZ.ChmuraD.NagyJ.TamásJ. (2015). New stand of invasive neophyte Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. and its potential reproduction.Polish J. Ecol.63453–459. 10.3161/15052249PJE2015.63.3.015

13

DarwinC. (1929). The origin of species by means of natural selection.Am. Anthropol.61176–177.

14

DiezJ. M.SullivanJ. J.HulmeP. E.EdwardsG.DuncanR. P. (2008). Darwin’s naturalization conundrum: dissecting taxonomic patterns of species invasions.Ecol. Lett.11674–681. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01178.x

15

DongH.SongZ.LiuT.LiuZ.LiuY.ChenB.et al (2020). Causes of differences in the distribution of the invasive plants Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Ambrosia trifida in the Yili Valley, China.Ecol. Evol.1013122–13133. 10.1002/ece3.6902

16

Epanchin-NiellR. S.HastingsA. (2010). Controlling established invaders: integrating economics and spread dynamics to determine optimal management.Ecol. Lett.13528–541. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01440.x

17

EsslF.BiróK.BrandesD.BroennimannO.BullockJ. M.ChapmanD. S.et al (2015). Biological flora of the british isles: Ambrosia artemisiifolia.J. Ecol.1031069–1098. 10.1111/1365-2745.12424

18

EsslF.DullingerS.KleinbauerI. (2009). Changes in the spatio-temporal patterns and habitat preferences of Ambrosia artemisiifolia during its invasion of Austria.Preslia81119–133.

19

FenesiA.VágásiC.BeldeanM.FöldesiR.KolcsárL.ShapiroJ. T.et al (2015). Solidago canadensis impacts on native plant and pollinator communities in different-aged old fields.Basic Appl. Ecol.16335–346. 10.1016/j.baae.2015.03.003

20

FengL.YueM. F.TianX. S.QiG. J.LvL. H. (2012). Distribution and growth characteristics of common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) in Guangdong Province, China.Chinese J. Biosafety21210–215.

21

FengY.FuG. (2008). Nitrogen allocation, partitioning and use efficiency in three invasive plant species in comparison with their native congeners.Biol. Invasions10891–902. 10.1007/s10530-008-9240-3

22

FridleyJ. D.StachowiczJ. J.NaeemS.SaxD. F.SeabloomE. W.SmithM.et al (2007). The invasion paradox: reconciling pattern and process in species invasions.Ecology883–17. 10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[3:TIPRPA]2.0.CO;2

23

FumanalB.PlenchetteC.ChauvelB.BretagnolleF. (2006). Which role can arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi play in the facilitation of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. invasion in France?Mycorrhiza1725–35. 10.1007/s00572-006-0078-1

24

GajnikD.PeternelR. (2009). Methods of intervention in the control of ragweed spread (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) in the area of Zagreb county and the city of zagreb.Collegium Antropologicum331289–1294.

25

GalzinaN.BarićK.ŠćepanovićM.GoršićM.OstojićZ. (2010). Distribution of invasive weed Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. in croatia.Agriculturae Conspectus Sci.7559–65.

26

GentiliR.GilardelliF.BonaE.ProsserF.CitterioS. (2016). Distribution map of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. (Asteraceae) in Italy.Plant Biosystems Int. J. Dealing Aspects Plant Biol.151381–386. 10.1080/11263504.2016.1176966

27

GiljohannK. M.HauserC. E.WilliamsN. S. G.MooreJ. L. (2011). Optimizing invasive species control across space: willow invasion management in the Australian Alps.J. Appl. Ecol.481286–1294. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02016.x

28

GusevA. P. (2019). Invasion of Ambrosia artemisifolia L. into the landscapes of the Southeastern Belarus.Russ. J. Biol. Invasions10129–135. 10.1134/S2075111719020061

29

Hamaoui-LaguelL. (2018). Effects of climate change and seed dispersal on airborne ragweed pollen loads in Europe.Nat. Climate Change5766–771. 10.1038/nclimate2652

30

HauserC. E.McCarthyM. A. (2009). Streamlining ‘search and destroy’: cost-effective surveillance for invasive species management.Ecol. Lett.12683–692. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01323.x

31

HejdaM.ChytryM.PerglJ.PyšekP.DiezJ. (2015). Native range habitats of invasive plants: are they similar to invaded range habitats and do they differ according to the geographical direction of invasion?Diversity Distrib.21312–321. 10.1111/ddi.12269

32

IgrcJ.DeloachC. J.ZlofV. (1995). Release and establishment of Zygogramma suturalis F (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in croatia for control of common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.).Biol. Control5203–208. 10.1006/bcon.1995.1025

33

JiaF. Q.HanN. E.ZhangX. F.ZhangW.ZhaoY. (2011). Age structures of components of Leymus chinensis population in different habitats in the Yili River Valley Area, China.Chinese J. Grassland3395–99.

34

LeiY.WuZ.-L.WuL.-Z.ShiH.-L.BaiH. T.FuW.et al (2018). Interspecific correlation between exotic and native plants under artificial wetland forests on the Dianchi lakeside, south-west China.Mar. Freshwater Res.69669–676. 10.1071/MF17177

35

LeibleinM. C.LöschR. (2011). Biomass development and CO2 gas exchange of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. under different soil moisture conditions.Flora206511–516. 10.1016/j.flora.2010.09.011

36

LeskovšekR.ElerK.BatičF.SimončičA. (2012a). The influence of nitrogen, water and competition on the vegetative and reproductive growth of common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.).Plant Ecol.213769–781. 10.1007/s11258-012-0040-6

37

LeskovšekR.DattaA.KnezevicS. Z.SimončičA. (2012b). Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) dry matter allocation and partitioning under different nitrogen and density levels.Weed Biol. Manag.1298–108. 10.1111/j.1445-6664.2012.00439.x

38

LiS. P.GuoT.CadotteM. W.ChenY. J.KuangJ. L.HuaZ. S.et al (2015). Contrasting effects of phylogenetic relatedness on plant invader success in experimental grassland communities.J. Appl. Ecol.5289–99. 10.1111/1365-2664.12365

39

LiuL.WangX.WenQ.JiaQ.LiuQ. (2017). Interspecific associations of plant populations in rare earth mining wasteland in southern China.Int. Biodeterioration Biodegradation11882–88. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.01.011

40

LiuX. L.LiH. Q.WangJ. H.SunX. P.XingL. G. (2021). The current and future potential geographical distribution of common ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia in China.Pakistan J. Botany53167–172. 10.30848/PJB2021-1(18)

41

LiuY. (2019). Study on Occurrencen, Spread and Control of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. in Henan Province.Master’s thesis, Zhengzhou (Henan Province): Agricultural University of Henan.

42

MaC.LiS. P.PuZ.TanJ.LiuM.ZhouJ.et al (2016). Different effects of invader–native phylogenetic relatedness on invasion success and impact: a meta-analysis of Darwin’s naturalization hypothesis.Proc. Biol. Sci.283:20160663. 10.1098/rspb.2016.0663

43

MaQ. Q.LiuT.DongH. G.ZhaoW. X.WangH. Y.WangR. L. (2020). Predicting the potential distribution of ragweed in Xinjiang using multi-scale data source.J. Arid Land Resources Environ.34188–193.

44

MaitnerB. S.ParkD. S.EnquistB. J.DlugoschK. M. (2021). Where we’ve been and where we’re going: the importance of source communities in predicting establishment success from phylogenetic relationships.Ecography2022:e05406. 10.1111/ecog.05406

45

MakraL.JuhászM.BécziR. (2005). The history and impacts of airborne Ambrosia (Asteraceae) pollen in Hungary.Grana4457–64. 10.1080/00173130510010558

46

MangT.EsslF.MoserD.DullingerS. (2018). Climate warming drives invasion history of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in central Europe.Preslia9059–81. 10.23855/preslia.2018.059

47

MontagnaniC.GentiliR.SmithM.GuarinoM. F.CitterioS. (2017). The worldwide spread, success, and impact of ragweed (Ambrosia spp.).Critical Rev. Plant Sci.36139–178. 10.1080/07352689.2017.1360112

48

OzaslanC.OnenH.FarooqS.GunalH.AkyolN. (2016). Common ragweed: an emerging threat for sunflower production and human health in Turkey.Weed Biol. Manag.1642–55. 10.1111/wbm.12093

49

PatracchiniC.FerreroV. A. (2011). Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) growth as affected by plant density and clipping.Weed Technol.25268–276. 10.1614/WT-D-09-00070.1

50

PetrovaS. E. (2019). Development of invasive weeds Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. and A. trifida L. (Asteraceae) in Moscow Oblast.Russ. J. Biol. Invasions10370–381. 10.1134/S2075111719040088

51

PinkeG.KolejaniszT.VérA.NagyK.CzúczB. (2019). Drivers of Ambrosia artemisiifolia abundance in arable fields along the Austrian-Hungarian border.Preslia91369–389. 10.23855/preslia.2019.369

52

ProcheşŞWilsonJ.RichardsonD. M.RejmánekM. (2010). Searching for phylogenetic pattern in biological invasions.Global Ecol. Biogeography175–10.

53

PucM.WolskiT. (2013). Forecasting of the selected features of Poaceae (R. Br.) Barnh., Artemisia L. and Ambrosia L. pollen season in Szczecin, north-western Poland, using Gumbel’s distribution.Annals Agricultural Environ. Med. AAEM20:36.

54

PysekP.ChytryM. (2014). Habitat invasion research: where vegetation science and invasion ecology meet.J. Veg. Sci.251181–1187. 10.1111/jvs.12146

55

RadosevichS. R.HoltJ. S.GhersaC. M. (2007). Ecology of Weeds and Invasive Plants: Relationship to Agriculture and Natural Resource Management.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

56

RichterR.DullingerS.EsslF.LeitnerM.VoglG. (2013). How to account for habitat suitability in weed management programmes?Biol. Invasions15657–669. 10.1007/s10530-012-0316-8

57

RomainS.AndreasL.EditaT.Anna-KarinK.SandaR.LarsA.et al (2016). Phenological variation in Ambrosia artemisiifolia l. facilitates near future establishment at northern latitudes.PLoS One11:e0166510. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166510

58

SongJ. S.ProtsB. (1998). Invasion of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.(Compositae) in the ukrainian carpathians Mts. and the transcarpathian plain (central Europe).Korean J. Biol. Sci.2209–216. 10.1080/12265071.1998.9647409

59

ThamagaK. H.DubeT. (2018). Testing two methods for mapping water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) in the Greater Letaba river system, South Africa: discrimination and mapping potential of the polar-orbiting Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI sensors.Int. J. Remote sensing398041–8059. 10.1080/01431161.2018.1479796

60

ThomazS. M.MichelanT. S. (2011). Associations between a highly invasive species and native macrophytes differ across spatial scales.Biol. Invasions131881–1891. 10.1007/s10530-011-0008-9

61

TretyakovaA. S.YakimovB. N.KondratkovP. V.GrudanovN. Y.CadotteM. W. (2021). Phylogenetic diversity of urban floras in the central urals.Front. Ecol. Evol.9:663244. 10.3389/fevo.2021.663244

62

WallerD. M.MudrakE. L.AmatangeloK. L.KlionskyS. M.RogersD. A. (2016). Do associations between native and invasive plants provide signals of invasive impacts?Biol. Invasions183465–3480. 10.1007/s10530-016-1238-7

63

XingY. F. (2012). Study on Distribution and Anatomical Structure of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. and Ambrosia trifida L. in Jilin Province.Master’s thesis, Changchun (Jilin Province): Northeast Normal University.

Summary

Keywords

Ambrosia artemisiifolia, invasive species, interspecific association, Darwin’s naturalization hypothesis, Darwin’s pre-adaptation hypothesis, early stage

Citation

Zhao W, Liu T, Sun M, Wang H, Liu X and Su P (2022) Rapid monitoring of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in semi-arid regions based on ecological convergence and phylogenetic relationships. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10:926990. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.926990

Received

23 April 2022

Accepted

06 July 2022

Published

22 July 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Qinfeng Guo, United States Forest Service (USDA), United States

Reviewed by

Barış Özüdoğru, Hacettepe University, Turkey; Aleksandra Savic, Institute for Plant Protection and Environment (IZBIS), Serbia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Zhao, Liu, Sun, Wang, Liu and Su.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tong Liu, 469004509@qq.com

This article was submitted to Conservation and Restoration Ecology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.