- 1Mammal and Osteology Section, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

- 2Hemiptera Section, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

- 3Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Centipedes (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha), long regarded as generalist arthropod predators, are increasingly recognized for their capacity to subdue and consume small vertebrates. This review synthesizes over a century of published accounts documenting centipede predation on amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and occasionally fish, emphasizing the ecological breadth, behavioral strategies, and taxonomic diversity of both predators and prey. Notable cases include Scolopendra gigantea preying on bats in Venezuelan caves, Scolopendra subspinipes capturing snakes in urban environments, and Cormocephalus coynei exerting top-down control on seabird populations on predator-free islands. We also present the first confirmed case of bat predation by a centipede in Asia, where a Rhysida species was observed consuming a Pipistrellus bat in a fig tree hollow in West Bengal, India. This observation expands the known biogeography and ecological context of vertebrate predation by centipedes. Our synthesis highlights the underappreciated role of scolopendrid centipedes as mid-level predators capable of influencing small vertebrate populations, particularly in resource-limited or insular ecosystems, and calls for a re-evaluation of their functional position within terrestrial food webs.

1 Introduction

Predation is a central ecological force shaping trophic dynamics, influencing population regulation, species distributions, and evolutionary trajectories (Begon et al., 2006). While classical food web models often depict vertebrates preying upon invertebrates, an emerging body of literature emphasizes the importance of reverse trophic interactions where invertebrates act as predators of vertebrates (Nyffeler and Knörnschild, 2013; Nyffeler and Gibbons, 2022).

Across a range of taxa including arachnids, insects, myriapods, and crustaceans, invertebrates have been documented preying on vertebrate animals in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems (McCormick and Polis, 1982; Formanowicz and Bradley, 1987; Mori and Ohba, 2004; Nyffeler and Knörnschild, 2013; Valdez, 2020; Nyffeler and Gibbons, 2022; etc.). Among invertebrate predators, centipedes (class Chilopoda) represent a particularly intriguing and underappreciated group capable of subduing vertebrate prey (Undheim and King, 2011; Dugon and Arthur, 2012; Clark, 1979). Members of the order Scolopendromorpha, especially within the genus Scolopendra, are large, nocturnal, and venomous generalists that use modified forelegs (forcipules) to inject venom, immobilize prey, and initiate extra-oral digestion (Undheim and King, 2011; Dugon and Arthur, 2012). Although their primary diet consists of arthropods, accumulating evidence reveals that scolopendrid centipedes frequently prey on small vertebrates across diverse environments (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1968; Forti et al., 2007; Bauer, 1990; Molinari et al., 2005; Srbek-Araujo et al., 2012, etc.).

These interactions between centipede and vertebrate are often overlooked due to the secretive and nocturnal habits of centipedes, yet they may exert significant top-down pressures on small vertebrate populations, particularly in resource-limited habitats or insular ecosystems (Halpin et al., 2021). Unlike most terrestrial invertebrates, large scolopendrid centipedes are capable of overpowering prey exceeding their own body mass (Dugon and Arthur, 2012). This functional capacity positions them uniquely in terrestrial food webs, where they may occupy mid-level predator niches and influence vertebrate community composition. Their role in nutrient transfer and energy flow, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, is only beginning to be understood (Nyffeler and Gibbons, 2022).

This review synthesizes over a century of records on centipede predation on vertebrates, emphasizing the diversity of prey, attack strategies, ecological contexts, and the evolutionary implications of such interactions. By integrating published literature and novel observations, including the first documented case of bat predation by a centipede in Asia, we aim to expand the ecological narrative surrounding centipedes and highlight their role as key, albeit cryptic, predators of vertebrates.

2 Literature review

2.1 Overview of invertebrate-driven vertebrate mortality

A diverse array of invertebrates have been documented preying on vertebrates, often in ecologically impactful ways. For example, odonate larvae (dragonfly nymphs) are major predators of amphibian larvae and exert strong selective pressures on anuran life history traits (Morin, 1983; McCollum and Leimberger, 1997). In tropical ecosystems, army ants (Eciton burchellii) are known to kill and consume nestling birds and small reptiles during raids (Rettenmeyer et al., 2011). Similarly, wasps and spiders have been recorded depredating avian nestlings (Henriques, 1998; Nyffeler and Knörnschild, 2013).

These interactions are not merely incidental; they contribute significantly to mortality regimes and influence prey behavior and habitat use (Sih et al., 1998; Preisser et al., 2005). Importantly, they underscore the need to reassess traditional trophic hierarchies and recognize the diverse roles of invertebrates as apex or mesopredators in certain ecological contexts (Nyffeler and Birkhofer, 2017).

2.2 Centipede predation on amphibians

Predation events of centipedes have been documented across a range of amphibian taxa. In the Caribbean, Scolopendra alternans was observed attacking and consuming the toxic cane toad (Rhinella marina), a species known for its chemical defenses (Carpenter and Gillingham, 1984). This highlights the centipede’s resistance or indifference to amphibian toxins in some cases. Similarly, in tropical Australia, native centipedes (Ethmostigmus rubripes) have been reported killing invasive cane toads, indicating a remarkable reversal of expected predator–prey dynamics (Pomeroy et al., 2021). In Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Otostigmus tibialis has been recorded preying on the small arboreal tree frog Dendropsophus elegans, showcasing centipede predation within vertical forest strata (Forti et al., 2007). These observations provide crucial insights into centipedes as opportunistic and generalist predators capable of subduing toxic or agile amphibian prey across diverse ecosystems.

Although quantitative studies on the frequency and ecological impact of centipede-amphibian interactions are lacking, the available evidence suggests that centipedes play a significant, if under-recognized, role in amphibian mortality particularly among juveniles and small-bodied species.

2.3 Centipede predation on reptiles

Reptilian prey, especially small lizards and snakes, form a notable component of centipede diets. Species like Cormocephalus coynei, Scolopendra viridicornis and Scolopendra subspinipes have been recorded attacking geckos, skinks, and colubrids using venom injection and powerful mechanical restraint (Halpin et al., 2021; Vieira et al., 2021; Deb et al., 2023). These interactions occurred in microhabitats such as leaf litter, under logs, and within rock crevices, where reptiles are abundant and centipedes can ambush effectively.

Multiple field observations illustrate the breadth of reptilian predation. In India, Scolopendra hardwickei has been reported preying on Oligodon taeniolatus, a small snake (Smart et al., 2010), while in Thailand’s Sakaerat Biosphere Reserve, Scolopendra dawydoffi consumed Sibynophis triangularis (Chiacchio et al., 2017). In the Andaman Islands, S. dehaani was documented subduing Lycodon hypsirhinoides in forest habitats (Vazifdar et al., 2021), and Lycodon zawi in urban Guwahati (Deb et al., 2023), suggesting adaptability to varied landscapes.

In urban Singapore, Scolopendra subspinipes was recorded preying on multiple fossorial snakes such as Calamaria schlegeli, Calamaria pavimentata, and Pseudorabdion longiceps within green spaces embedded in city infrastructure (Pwa et al., 2023). Elsewhere, Scolopendra gigantea has been observed attacking Leptodeira bakeri, a colubrid snake (Goessling et al., 2012; van Buurt and Dilrosun, 2017). Additionally, Scolopendra sp. captured Calliophis melanurus, a venomous elapid, in Mumbai’s rocky outcrops (Mirza and Ahmed, 2009), indicating their ability to handle dangerous prey.

These accounts underscore the ecological versatility of large centipedes and their ability to exploit a wide range of reptilian prey across diverse habitats, from pristine forests and islands to anthropogenic settings such as cities and agricultural margins.

2.4 Centipede predation on birds and fish

Although uncommon, centipede predation on birds is best exemplified by Cormocephalus coynei on Phillip Island, Norfolk Island, Australia where it functions as a top terrestrial predator in the absence of mammals. This species preys on thousands of black-winged petrel (Pterodroma nigripennis) chicks annually by entering their burrows and using venom to subdue them (Halpin et al., 2021). Cormocephalus coynei also scavenges regurgitated marine fish from seabirds, demonstrating notable dietary flexibility (Halpin et al., 2021).

Historical reports suggest other Scolopendra species may occasionally prey on small birds (Cumming, 1903; Cloudsley-Thompson, 1968), though such accounts lack detailed verification. While active predation on fish has not been documented, scavenging behaviors particularly in island or predator-limited ecosystems reveal the trophic adaptability of some centipedes. These interactions challenge conventional views of invertebrate predators and warrant further ecological investigation.

2.5 Centipede predation on mammals

Mammalian predation by centipedes, particularly involving bats, is well-documented for Scolopendra gigantea in Venezuelan caves, where it preys on molossid and mormoopid bats (Molinari et al., 2005). Similar predation events involving Scolopendra viridicornis have been reported in Brazil (Srbek-Araujo et al., 2012; Noronha et al., 2015). In the United States, Scolopendra heros has been observed preying on Eptesicus fuscus in rock crevices in Texas (Lindley et al., 2017). In addition to bats, rodents have also been recorded as prey. For instance, Scolopendra galapagoensis has been observed preying upon the Galápagos rice rat Oryzomys bauri (= Aegialomys galapagoensis) (Clark, 1979), and unidentified rodents have been found in the diet of other large scolopendrid centipedes (Shugg, 1961). These observations expand the known mammalian prey base of centipedes and highlight their role as opportunistic vertebrate predators. The behavioral and ecological implications of such predation particularly concerning roost site selection, foraging behavior, and predator avoidance remain poorly studied but are likely to be significant.

3 Case study: centipede predation on a bat, a new record from Asia

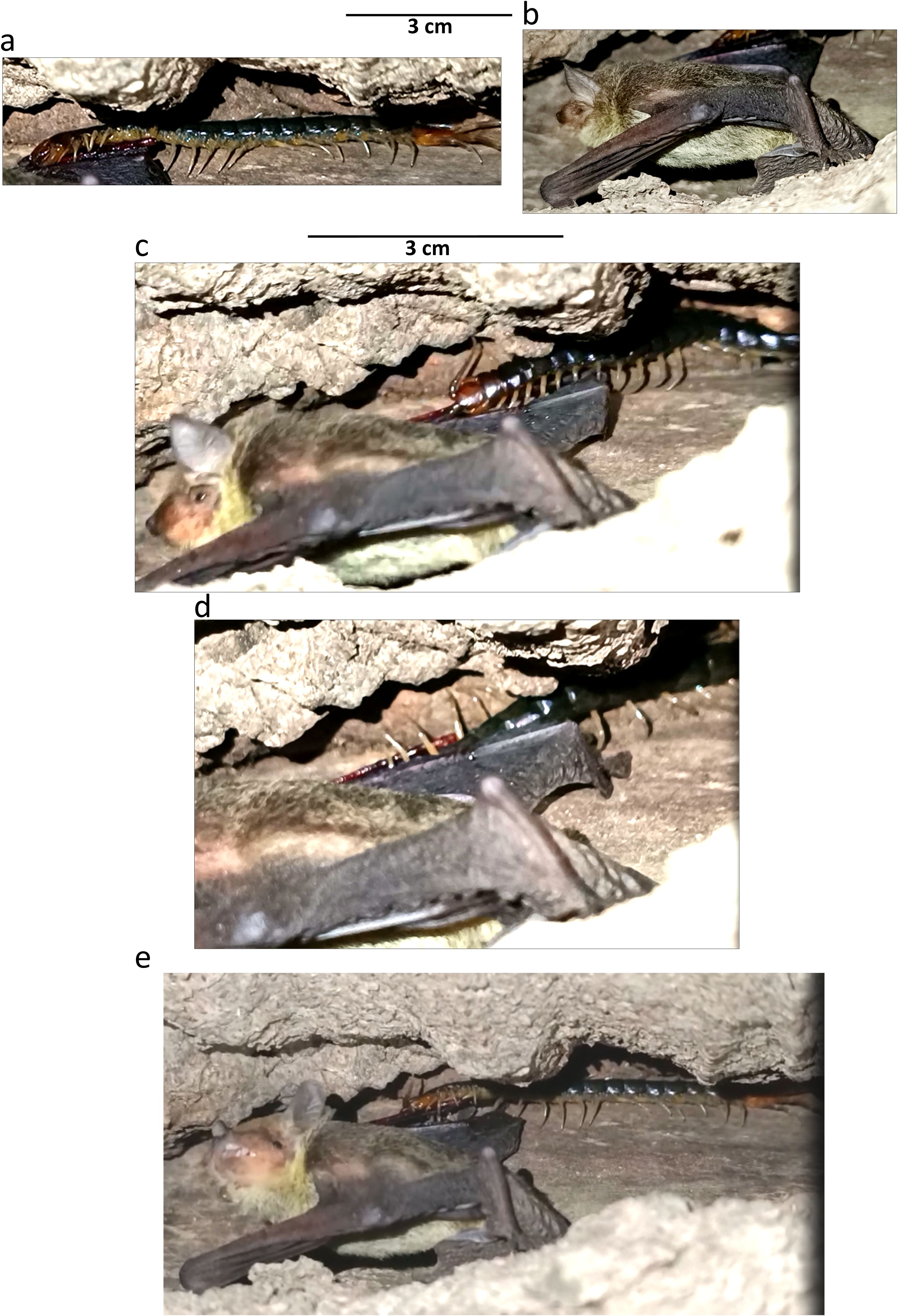

Recently, a team of scientists of Zoological Survey of India carried out a faunal survey in the dry tropical forests of West Bengal, India. The study area, Nakpur a village situated in the Nalhati Block of Birbhum district of West Bengal state in India (24.295684°N, 88.011694°E) which is primarily occupied by crop agricultural fields. During the insect survey in the study area, a centipede was observed preying on a bat in the hollow of a Sacred Fig (Ficus religiosa) tree at 20:30 h on 19 June 2024. This rare interaction was captured through photographs (Figure 1) and video (Supplementary material) to provide significant documentation. The centipede was identified as a species belonging to the genus Rhysida (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha: Scolopendridae), based on its head, dorsal body, ultimate legs and leg color, body profile (Figure 1a), and spiracle formula one of the diagnostic characters of the genus against other scolopendrids (Joshi et al., 2020; Sureshan, 2024; Bonato et al., 2025), while the bat was identified as a species belonging to genus Pipistrellus (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) due to its small size (≈ 6 cm), body shape, and internarial groove (Figure 1b) (Bates and Harrison, 1997; Sharma et al., 2024). Due to logistical constraints in the field and the non-invasive nature of the observation, molecular confirmation of species identity was not feasible. Both the bat and centipede were observed at the lower part of the tree, approximately 5 feet above the ground, and the tree was home to the Indian flying fox (Pteropus medius), spotted house gecko (Hemidactylus parvimaculatus), Asian common toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus), and bee nests. The weather during this observation was warm and humid, reaching a high of around 36°C (96.8°F)- West Bengal’s monsoon season. The centipede was notably longer than the bat (≈ 10 cm). The centipede began to feed on the bat’s wing membrane (Figure 1c) and proceeding deeper into the body of the bat (Figure 1d) while it was still alive (Figures 1c, e). The authors noted that the predatory actions occurred after the bat had been immobilized, yet its head continued moving while the centipede was feeding. After capturing a one-minute video and taking some photos, the researchers stepped back from the spot to prevent disrupting the centipede’s hunting behavior.

Figure 1. Bat predation by a centipede: (a) the predator Rhysida sp. centipede, (b) the prey Pipistrellus sp. bat, (c) the centipede immobilizes the bat using its forcipules while the bat is still alive; the open eye suggests it remains conscious, (d) damage to the bat’s wing membrane caused by the centipede, (e) the bat’s mouth is open as the centipede feeds, indicating a potential struggle or distress response. All images were taken under natural conditions using a flashlight during nighttime observations.

4 Discussion

Previous studies (Molinari et al., 2005; Srbek-Araujo et al., 2012; Noronha et al., 2015; Lindley et al., 2017) have reported bat predation by Scolopendra species in the Americas, mainly in caves and artificial structures. This new record suggests that arboreal predation on bats by centipedes may be more widespread than previously thought.

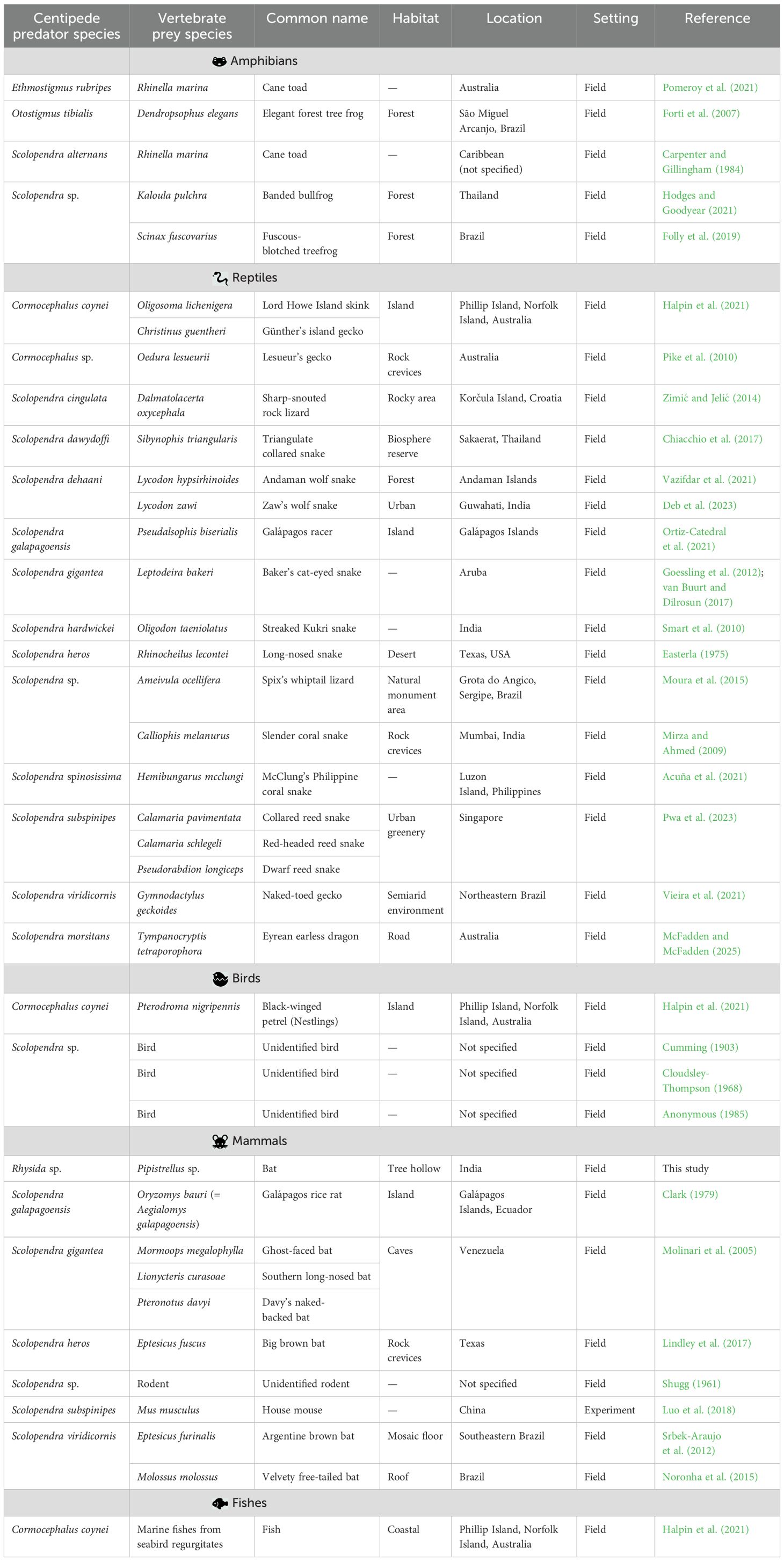

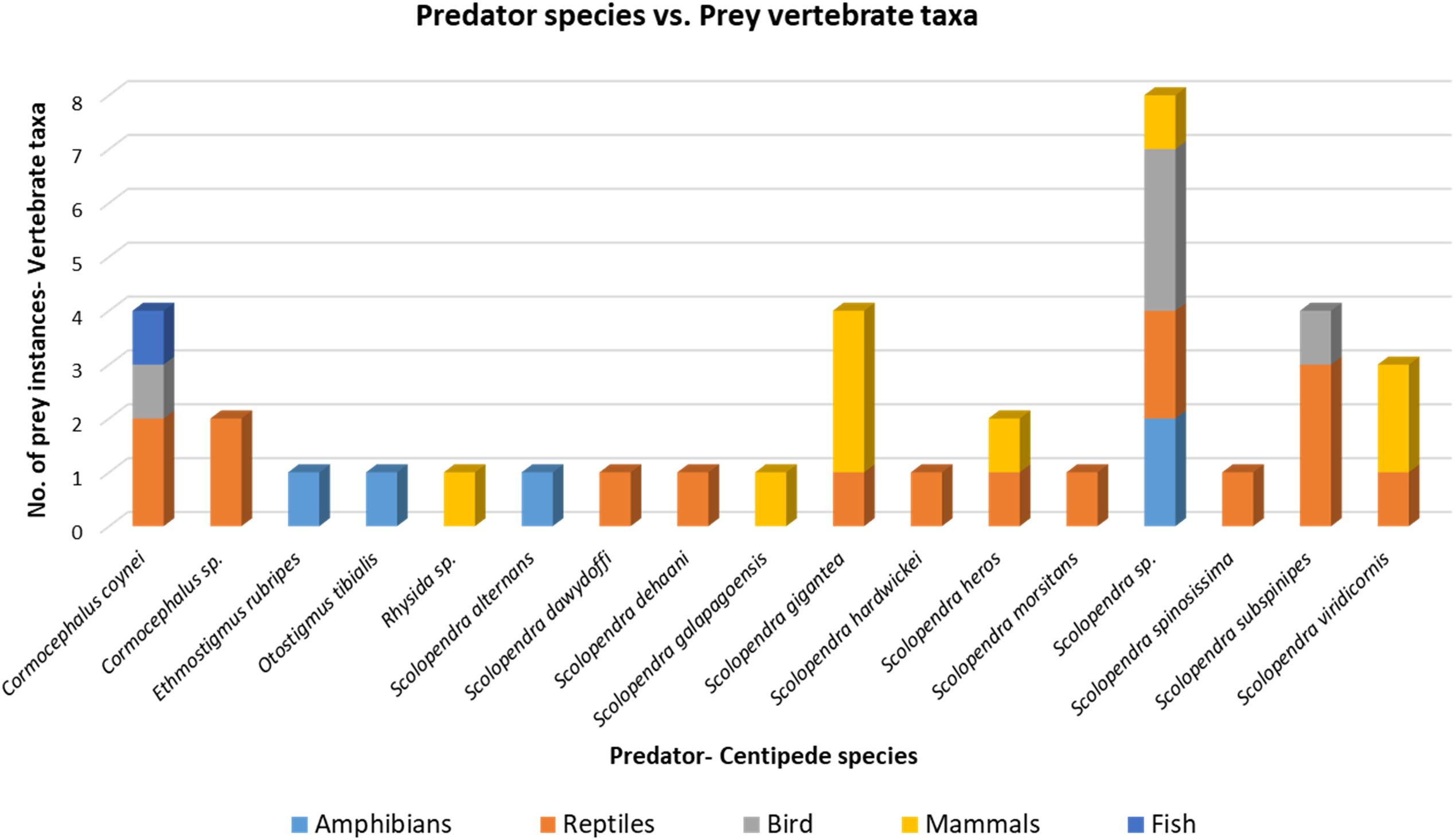

Our analysis on centipede predation on vertebrate reveals a clear taxonomic bias in centipede predation towards reptiles, particularly snakes (Table 1; Figure 2). Among the 16 centipede species with documented vertebrate predation, reptiles constitute the most frequently reported prey class. This trend is especially evident in large-bodied Scolopendra species such as Scolopendra subspinipes, Scolopendra gigantea, and Scolopendra heros, which have been recorded subduing snakes often comparable to their own size (Valdez, 2020; Easterla, 1975; van Buurt and Dilrosun, 2017; Pwa et al., 2023). The elongated, limbless morphology of snakes may facilitate subjugation and consumption by centipedes using their powerful forcipules and envenomation tactics (Lewis, 1981). Moreover, snakes often inhabit microhabitats also frequented by centipedes such as forest floors, under logs, or leaf litter thereby increasing encounter rates. This dietary inclination suggests that scolopendrid centipedes, though generalist predators, may exert predatory pressure on certain reptile populations, especially in insular or disturbed ecosystems where snakes are among the few available vertebrate prey.

Table 1. Documented instances of centipede predators and their vertebrate prey species (amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and fishes).

Figure 2. Stacked bar chart showing the number of prey instances consumed by different centipede predator species and also indicate different group of vertebrate. This visualization highlights variation in feeding breadth and prey specialization across predator species.

5 Conclusion

Vertebrate predation by centipedes, though often overlooked, is neither rare nor ecologically insignificant. Our review reveals that large scolopendrid centipedes occupy a unique trophic niche, with documented ability to subdue vertebrate prey ranging from amphibians and reptiles to birds and mammals across diverse habitats worldwide. The new record from India involving a Rhysida centipede feeding on a live bat in an arboreal setting represents the first such case from Asia and challenges prior assumptions that such interactions are confined to cave or ground environments. Collectively, these findings underscore the ecological versatility, behavioral sophistication, and predatory impact of scolopendrid centipedes. Future research should prioritize quantitative assessments of their predation rates, prey selection, and ecological consequences, especially in tropical and subtropical ecosystems where they may serve as cryptic yet influential components of vertebrate mortality regimes.

Author contributions

MK: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Project administration, Validation, Formal Analysis. RM: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. DB: Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the core funding from the Zoological Survey of India, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. M. Sureshan, former senior scientist at the Zoological Survey of India, for his valuable assistance in identifying the centipede genus.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2025.1634037/full#supplementary-material

References

Acuña D., Isagani N., and Pitogo K. M. (2021). Predation on a McClung’s Philippine False Coralsnake, Hemibungarus mcclungi (Weigmann 1835), by a Giant Spiny Centipede, Scolopendra spinosissima Kraepelin 1903, on Luzon Island, The Philippines. Reptiles Amphibians 28, 417–419.

Anonymous (1985). Dangerous Australians (Sydney: Bay Books). https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v28i3.15782

Bates P. J. and Harrison D. L. (1997). Bats of the Indian Subcontinent (Sevenoaks, UK: Harrison Zoological Museum), 258 pp.

Bauer A. M. (1990). Gekkonid lizards as prey of invertebrates and predators of vertebrates. Herpetol. Rev. 21, 83–87.

Begon M., Townsend C. R., and Harper J. L. (2006). Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems (4th ed.) (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing).

Bonato L., Chagas-Junior A., Edgecombe G. D., Lewis J. G. E., Minelli A., Pereira L. A., et al. (2025). ChiloBase 2.0 – A World Catalogue of Centipedes (Chilopoda). Available online at: http://chilobase.biologia.unipd.it (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Carpenter C. C. and Gillingham J. C. (1984). Giant centipede (Scolopendra alternans) attacks marine toad (Bufo marinus). Caribbean J. Sci. 20, 71–72.

Chiacchio M., Nadolski B. S., Suwanwaree P., Waengsothorn S., et al. (2017). Centipede, Scolopendra dawydoffi (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae), predation on an egg-laying snake, Sibynophis triangularis (Squamata: Colubridae), in Thailand. J. Insect Behav. 30, 563–566. doi: 10.1007/s10905-017-9642-0

Clark D. B. (1979). Centipede preying on a nestling rice rat (Oryzomys bauri). J. Mammal. 60, 654. doi: 10.2307/1380119

Cloudsley-Thompson J. L. (1968). Spiders, Scorpions, Centipedes, and Mites (Oxford: Pergamon Press).

Cumming W. D. (1903). The food and poison of a centipede. J. Bombay Natural History Soc. 15, 364–365.

Deb A., Sinha D., and Purkayastha J. (2023). Predation on Zaw’s Wolfsnake (Lycodon zawi) by a Malaysian Cherry Red Centipede (Scolopendra dehaani). Reptiles Amphibians 30, e18468. doi: 10.17161/randa.v30i1.18468

Dugon M. M. and Arthur W. (2012). Prey orientation and the role of venom availability in the predatory behavior of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans (Arthropoda: Chilopoda). J. Insect Physiol. 58, 874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.03.014

Easterla D. A. (1975). Predation by Scolopendra heros on Rhinocheilus lecontei. Southwestern Naturalist. 20(3):411.

Folly H., Thaler R., Adams G. B., and Pereira E. A. (2019). Predation on Scinax fuscovarius (Anura, Hylidae) by Scolopendra sp. (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae) in the State of Tocantins, Central Brazil. Rev. Latinoamericana Herpetol. 2, 39–43.

Formanowicz D. R. and Bradley P. J. (1987). Fluctuations in prey density: effects on the foraging tactics of scolopendrid centipedes. Anim. Behav. 35, 453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80270-1

Forti L. R., Fischer H. Z., and Encarnação L. C. (2007). Treefrog Dendropsophus elegans (Wied-Neuwied 1824) (Anura: Hylidae) as a meal to Otostigmus tibialis Brölemann 1902 (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae) in the tropical rainforest in southeastern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 67, 583–584. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842007000300028

Goessling J. M., Lutterschmidt W. I., Odum R. A., and Reinert H. K. (2012). Leptodeira bakeri (Aruban cat-eyed snake). Predation. Herpetol. Rev. 43, 345.

Halpin L. R., Terrington D. I., Jones H. P., Mott R., Wong W. W., Dow D. C., et al. (2021). Arthropod predation of vertebrates structures trophic dynamics in island ecosystems. Am. Nat. 198, 540–550. doi: 10.1086/715702

Henriques R. (1998). Bird predation on nest of a social wasp in Brazilian cerrado. Rev. Biol. Trop. 46, 1139–1140.

Hodges C. W. and Goodyear J. (2021). Novel foraging behaviors of Scolopendra dehaani (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae) in Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 41, 3257–3262. doi: 10.1007/s42690-021-00431-9

Joshi J., Karanth P. K., and Edgecombe G. D. (2020). The out-of-India hypothesis: evidence from an ancient centipede genus, Rhysida (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha) from the Oriental Region, and systematics of Indian species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 189, 828–861. doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz138

Lindley T. T., Molinari J., Shelley R. M., and Steger B. N. (2017). A fourth account of centipede (Chilopoda) predation on bats. Insecta Mundi 573, 1–4.

Luo L., Li B., Wang S., Wu F., Wang X., Liang P., et al. (2018). Centipedes subdue giant prey by blocking KCNQ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 115, 1646–1651.

McCollum S. A. and Leimberger J. D. (1997). Predator-induced morphological changes in an amphibian: predation by dragonflies affects tadpole shape and color. Oecologia 109, 615–621. doi: 10.1007/s004420050124

McCormick S. and Polis G. A. (1982). Arthropods that prey on vertebrates. Biol. Rev. 57, 29–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1982.tb00363.x

McFadden M. S. and McFadden J. M. (2025). Predation of an adult Eyrean Earless Dragon, Tympanocryptis tetraporophora, by a Red-headed Centipede, Scolopendra morsitans, in Australia. Herpetol. Notes 18, 221–223.

Mirza Z. A. and Ahmed J. J. (2009). Note on predation of Calliophis melanurus Shaw 1802 (Serpentes: elapidae) by Scolopendra sp. Hamadryad 34, 166.

Molinari J., Gutiérrez E. E., Ascencao A. A., Nassar J. M., Arends A., and Márquez R. J. (2005). Predation by giant centipedes, Scolopendra gigantea, on three species of bats in a Venezuelan cave. Caribbean J. Sci. 41, 340–346.

Mori A. and Ohba S. (2004). Field observations of predation on snakes by the giant water bug. Bull. Herpetol. Soc. Japan 2004, 78–81.

Morin P. J. (1983). Predation, competition, and the composition of larval anuran guilds. Ecol. Monogr. 53, 119–138. doi: 10.2307/1942491

Moura L. O. G., MaChado C. M. S., Silva A. O., Conceição B. M., Ferreira A. S., and Faria R. G. (2015). Predation of Ameivulla ocellifera (Spix 1825) (Squamata: Teiidae) by Scolopendra sp. (Linneaus 1758) (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae) in the vegetation of the Caatinga biome, northeastern Brazil. Herpetol. Notes. 8, 389–391.

Noronha J. C., Battirola L. D., Chagas-Júnior A., Miranda R. M., Carpanedo R. S., and Rodrigues D. J. (2015). Predation of bat (Molossus molossus: Molossidae) by the centipede Scolopendra viridicornis (Scolopendridae) in Southern Amazonia. Acta Amazonica 45, 333–336. doi: 10.1590/1809-4392201404083

Nyffeler M. and Birkhofer K. (2017). An estimated 400–800 million tons of prey are annually killed by the global spider community. Sci. Nat. 104, 30. doi: 10.1007/s00114-017-1440-1

Nyffeler M. and Gibbons J. W. (2022). Spiders feeding on vertebrates is more common and widespread than previously thought, geographically and taxonomically. J. Arachnol. 50, 121–134. doi: 10.1636/JoA-S-21-054

Nyffeler M. and Knörnschild M. (2013). Bat predation by spiders. PloS One 8, e58120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058120

Ortiz-Catedral L., Christian E., Chimborazo W., Sevilla C., and Rueda D. (2021). A Galapagos centipede Scolopendra galapagoensis preys on a Floreana Racer Pseudalsophis biserialis. Galapagos Res. 70, 2–4.

Pike D. A., Croak B. M., Webb J. K., and Shine R. (2010). Context-dependent avoidance of predatory centipedes by nocturnal geckos (Oedura lesueurii). Behaviour 147, 397–412. doi: 10.1163/000579509X12578482408448

Pomeroy J., Brown G. P., Webb G. J. W., and Shine R. (2021). The fauna fights back: Invasive Cane Toads killed by native centipedes in tropical Australia. Aust. Zool. 41, 580–585. doi: 10.7882/AZ.2021.002

Preisser E. L., Bolnick D. I., and Benard M. F. (2005). Scared to death? The effects of intimidation and consumption in predator–prey interactions. Ecology 86, 501–509. doi: 10.1890/04-0719

Pwa V. K. H., Yap S., Law I. S., Law I. T., Wong J., and Figueroa A. (2023). Predation on two species of reed snakes (Squamata: Colubridae: Calamariinae) by the giant forest centipede, Scolopendra subspinipes Leach 1815 (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae), in Singapore. Herpetol. Notes 16, 577–582.

Rettenmeyer C. W., Rettenmeyer M. E., Joseph J., and Berghoff S. M. (2011). The largest animal association centered on one species: the army ant Eciton burchellii and its more than 300 associates. Insect. Soc 58, 281–292. doi: 10.1007/s00040-010-0128-8

Sharma G., Kamalakannan M., Saikia U., Talmale S., Dam D., Banerjee D., et al. (2024). Checklist of Fauna of India: Chordata: Mammalia. Version 1.0 (Zoological Survey of India). doi: 10.26515/Fauna/1/2023/Chordata:Mammals

Sih A., Englund G., and Wooster D. (1998). Emergent impacts of multiple predators on prey. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 350–355. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01437-2

Smart U., Patel P., and Pattanayak P. (2010). Scolopendra hardwickei (Newport 1844) feeding on Oligodon taeniolatus (Jerdon 1853) in the scrub jungles of Pondicherry, southern India. J. Bombay Natural History Soc. 107, 68.

Srbek-Araujo A. C., Nogueira M. R., Lima I. P., and Peracchi A. L. (2012). Predation by the centipede Scolopendra viridicornis (Scolopendromorpha: Scolopendridae) on roof-roosting bats in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil. Chiroptera Neotropical 18, 1128–1131.

Sureshan P. M. (2024). Fauna of India Checklist: Arthropoda: Myriapoda: Chilopoda (Zoological 409 Survey of India). doi: 10.26515/Fauna/1/2023/Arthropoda:Myriapoda:Chilopoda

Undheim E. A. B. and King G. F. (2011). On the venom system of centipedes (Chilopoda), a neglected group of venomous animals. Toxicon 57, 512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.01.004

Valdez J. W. (2020). Arthropods as vertebrate predators: A review of global patterns. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 1691–1703. doi: 10.1111/geb.13157

van Buurt G. and Dilrosun F. (2017). Predation by an Amazonian giant centipede (Scolopendra gigantea) on a Baker’s cat-eyed snake (Leptodeira bakeri). Reptiles Amphibians 24, 127.

Vazifdar N., Khalid M. A., and D’Costa M. (2021). A centipede (Scolopendra dehaani) feeding on a juvenile Andaman wolfsnake (Lycodon hypsirhinoides) on Havelock Islands, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Reptiles Amphibians 28, 326–327. doi: 10.17161/randa.v28i2.15607

Vieira W. L. S., Gonçalves M. B. R., Morais E. R., Macedo Júnior F. V., and Vieira K. S. (2021). Predation of naked-toed gecko, Gymnodactylus geckoides Spix 1825 by giant centipede, Scolopendra viridicornis Newport 1844 in northeastern Brazil (Squamata: Phyllodactylidae). Herpetol. Notes 14, 671–673.

Keywords: bat, centipede, prey, predation, Pipistrelles

Citation: Kamalakannan M, Mondal R and Banerjee D (2025) Centipede predation on vertebrates: a review with the first bat case from Asia. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1634037. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1634037

Received: 23 May 2025; Accepted: 09 July 2025;

Published: 28 July 2025.

Edited by:

Jing Chen, Institute of Zoology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Darrell Acuña, University of Santo Tomas, PhilippinesCopyright © 2025 Kamalakannan, Mondal and Banerjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manokaran Kamalakannan, a2FtYWxha2FubmFubTFAZ21haWwuY29t

Manokaran Kamalakannan

Manokaran Kamalakannan Rahul Mondal

Rahul Mondal Dhriti Banerjee3

Dhriti Banerjee3