- 1Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Concepción, Chile

- 2Facultad de Artes Liberales, Universidad Adolfo Ibañez, Viña del Mar, Chile

- 3School of Archaeology, Universidad Austral de Chile, Puerto Montt, Chile

- 4Doctorado en Ciencias, mención en Biodiversidad y Biorecursos, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Concepción, Chile

- 5Instituto Milenio en Socio-Ecología Costera (SECOS), Santiago, Chile

Kelp forests are among the most productive and resilient coastal ecosystems, providing long-term ecological stability and diverse resources for marine and human communities. These attributes underpin the Kelp Highway Hypothesis (KHH), which proposes that kelp-dominated seascapes facilitated early human coastal dispersal and settlement along the Pacific Rim. While most KHH research has focused on the North Pacific, its southern extension remains poorly understood. Here, we apply species distribution models (SDMs) to reconstruct the potential distribution of major kelp species along the Pacific coast of South America during three key paleoclimatic periods: the Last Glacial Maximum, the Mid-Holocene, and the Medieval Warm Period. Our results reveal persistent and spatially continuous kelp habitats over millennial timescales, with evidence of poleward shifts in suitable areas following postglacial warming. When compared with published archaeological data, these reconstructions show recurrent spatial overlap between favorable kelp habitats and early coastal sites. Although direct evidence of kelp use remains scarce, this spatial congruence supports the idea that kelp forests may have provided stable and productive environments that facilitated human occupation and mobility along the southeastern Pacific coast. By integrating paleoenvironmental modeling with archaeological evidence, this study contributes a novel South American perspective to the KHH and demonstrates the potential of SDMs for reconstructing ancient coastal ecosystems within a paleoecological framework.

1 Introduction

Forest-forming kelps, recognized for their role as ecosystem engineers, provide essential ecological functions that sustain coastal biodiversity and productivity (Jones et al., 1994; Steneck et al., 2002). They span approximately one-third of the world’s coastline, support the livelihoods of nearly 750 million coastal inhabitants, and contribute an estimated $500 billion annually to the global economy (Jayathilake and Costello, 2021; Eger et al., 2023). Their present and future socioecological relevance is enormous (Eger et al., 2023). Similarly, archaeological and historical records have recently highlighted the long-standing relationship between kelp forests and human populations. Based on archaeological site found in the California Channel Islands, the kelp highway hypothesis (KHH) proposed an alternative for the initial peopling of the Americas: a coastal migration route. It proposed that during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ∼20,000 years ago), humans crossed the Behring Strait and migrated southward along the Pacific coast following productive kelp forests habitats (Erlandson et al., 2007). This dispersal probably occurred contemporaneously with a central continental route focused on terrestrial Pleistocene megafauna, as traditionally proposed by the Clovis hypothesis (Dillehay, 1997). Unlike earlier hypothesis that proposed a single inland migration route through Beringia, it has since been recognized that such a terrestrial pathway would have required rapid movement through a wide range of ecosystems within a relatively short time frame—on the order of a millennium (Erlandson et al., 2015). The early scarcity of supporting archaeological evidence for the KHH was likely due, in large part, to the post-glacial global rise in sea levels (Erlandson, 2013; Erlandson et al., 2025). The peopling of the Americas is now understood as a complex process involving successive migratory waves that utilized both coastal and inland routes, thus matching recent archaeological and paleogenetic evidence (Meltzer, 2021).

The continental-scale of the diversity and predictability of marine resources linked to kelp forest–seabirds, waterfowl, marine mammals, fishes, shellfish and seaweeds– are the foundation of the KHH (Erlandson et al., 2015; Schiel and Foster, 2015). Indigenous practices in the Pacific Northwest further underscore their ecological and cultural significance. For example, sustainable management of Pacific herring demonstrates a deep understanding of human-environment interactions, as hemlock branches were placed in kelp-rich areas to collect herring eggs, promoting spawning and reflecting advanced ecological knowledge (Thornton, 2015). In this way, the KHH provided support to 14,500-year-old Monteverde archaeological site in southern Chile, one of the oldest evidence of human occupation in the Americas, and the first to put forward a coastal alternative to the Clovis hypothesis-heavily contested initially (Dillehay, 1997; Meltzer et al., 1997; Dillehay et al., 2008).

Along the Andean coastline, kelp forests thrive from Peru to Tierra del Fuego under the influence of the highly productive Humboldt Current, one of the major Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems (EBUS) (Bakun, 1990; Cuba et al., 2022). Past human uses of kelp along the Humboldt ecosystems extended from the construction of floors and walls, to part of funerary practices, and as sources of fuel, food, and fertilizer (Araos et al., 2018; Borie et al., 2006; Arriaza and Standen, 2009; Montt et al., 2021; Núñez et al., 1974; Moragas and Mendez-Quiros, 2022; Sitzia et al., 2023). Beyond past cultural uses, kelp forests continue to provide critical ecosystem services, including the attenuation of nearshore wave energy, which facilitates resource gathering even under adverse storm conditions (Mork, 1996; Elsmore et al., 2024). Complementing this broader perspective, recent studies have documented evidence of past kelp utilization along the northern coast of Chile, where kelp served not only as a direct food resource and as critical habitat for associated food species (Vega et al., 2016; Vega, 2016), but also as an essential source of fuel in arid coastal regions where terrestrial wood resources were limited (Sitzia et al., 2023). Recent zooarchaeological evidence highlights that coastal populations specialized in, and heavily relied on, kelp-associated species—including coastal birds, pinnipeds, fishes, mollusks, and crustaceans—for both food and raw materials (Lopez et al., 2025; Rebolledo et al., 2016, 2021; Salazar et al., 2015, 2018).

One of earliest pieces of evidences of kelp use comes from shell middens—archaeological deposits that preserve records of coastal resource use over millennia (Rick, 2024). Along the Pacific coast of the Americas, shell middens rich in Tegula shells, abalone, and other kelp-dependent species reflect the long-term importance of these ecosystems for coastal communities (Rick and Erlandson, 2016; Erlandson et al., 2015; Ainis et al., 2014, 2019; Ainis and Erlandson, 2025; Erlandson et al., 2025). On the coast of South America, archaeological shell middens –locally known as conchales or concheros – provide exceptionally well-preserved evidence on human diet, on the use of marine resources and cultural patterns owing to the extreme aridity of the region (Flores et al., 2016; Olguín et al., 2015; Salazar et al., 2015; Moragas and Mendez-Quiros, 2022; Zangrando, 2018; Lopez et al., 2025). Similarly, their use in habitational contexts or the presence of associated fauna such as Tegula or Scurria snails serve as indirect indicators of kelp (Alcalde et al., 2023).

As such, either direct or indirect evidence suggest the presence of kelp ecosystems across the Holocene along the arid and hyperarid coast of the Atacama desert. However, past kelp range dynamics remain poorly understood. To date, evidence remains indirect and limited to a single kelp species. Genetic analyses combined with a species distribution model (SDM) for Macrocystis pyrifera during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) revealed climate-driven range shifts and indicated that the highest genetic diversity of this species occurs in the Northern Hemisphere, likely reflecting its area of origin (Assis et al., 2023). In California, reconstructions of sea level and associated geomorphological changes on offshore islands have been used to infer variations in nearshore reef extent and their capacity to sustain kelp forest ecosystems since the LGM (Graham et al., 2010; Kinlan et al., 2005). Past kelp forest productivity has also been inferred from multiscale analyses of zooarchaeological assemblages, which further suggest that indigenous peoples managed urchin populations through intensive harvesting (Mcfarland et al., 2025). It is well-known that the northern sector of the Humboldt Upwelling Ecosystem (HUE) experienced large changes in sea surface temperature and consequently in upwelling conditions after the LGM and across the Holocene (Ortlieb et al., 2011; Carré et al., 2016; Flores and Broitman, 2021). In this way, multi-species kelp forest abundance and distribution, particularly at its trailing (warm) edge are likely to have experienced range expansions and contractions.

Species Distribution Models (SDMs) offer a powerful framework for linking species occurrences with climatic variables, enabling reconstructions of past distributions and projections under future climate scenarios (Austin, 2002; Robinson et al., 2017; Assis et al., 2023; Torres et al., 2024). SDMs allow us to link the current distribution of a species to current environmental conditions and project it to other scenarios in time and space (Sillero et al., 2021). Although widely applied in terrestrial systems, their use has been more limited in marine environments (Robinson et al., 2011; Melo-Merino et al., 2020). Advances in remote sensing and the increasing availability of high-resolution environmental datasets are now bridging this gap, providing new opportunities to model and conserve critical coastal ecosystems (Melet et al., 2020). Global climate models, such as those from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) and Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase 4 (PMIP4) (Kageyama et al., 2018), further enhance our ability to reconstruct past oceanographic conditions relevant to kelp forest distributions.

Given that kelp forests provide rich and stable coastal resources, and that archaeological evidence supports persistent maritime adaptations along the Pacific rim, we explore whether the past distribution of kelp forests in South America—shaped by oceanographic changes—could have generated ecologically rich coastal areas that coincided with early human presence. Here, we reconstruct the potential distribution of South American kelp forests under past climatic conditions and examine their spatial overlap with archaeological sites of early coastal occupation. This study leverages the archaeological record to contextualize modeled reconstructions of suitable habitats for forest-forming kelp species along the South American coast.

2 Methods

2.1 Species occurrence data

To map the distribution of kelp forests in South America, we extracted present-day occurrence data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) on September 9, 2024, retrieving a total of 2,581 records from its open-access platform (GBIF.org, 2024g). These occurrences encompassed all known forest-forming macroalgal species occurring in South America (Wernberg et al., 2019), including Macrocystis pyrifera (GBIF.org, 2024a), Durvillaea incurvata (GBIF.org, 2024b), Durvillaea antarctica (GBIF.org, 2024b), Lessonia flavicans (GBIF.org, 2024c), Lessonia trabeculata (GBIF.org, 2024d), Lessonia spicata (GBIF.org, 2024e), and Lessonia berteroana (GBIF.org, 2024f). We further incorporated 49 additional occurrence records for two low-latitude species, Eisenia cokeri and Eisenia gracilis, which were not available in GBIF at the time of data retrieval (Ávila Peltroche et al., 2024; Uribe et al., 2024). Other Eisenia species such as Eisenia galapagensis occur in the Galápagos Archipelago, but given their restricted insular distribution and subtropical affinity, were not considered relevant to the temperate coastal environments addressed in this study.

We applied a series of quality filters to clean the dataset from unreliable records, excluding records predating 1980, occurrences located on land, duplicate coordinates, and records with positional uncertainty exceeding 10 km (Feng et al., 2019). To compensate possible geographic biases and mitigate spatial clustering to achieve a more uniform distribution of records, we implemented a ‘thinning’ of the records, with a 5.5 km2 radius, selecting a single occurrence per grid cell at random (Fourcade et al., 2014; Sillero et al., 2021). This spatial resolution was chosen to maintain consistency with the environmental variables used in subsequent analyses (Barbosa et al., 2010). To account for regional differences in ecological and evolutionary processes, we classified the filtered occurrences into biogeographical regions following the classifications by Spalding et al. (2007). We used two units of coastal biogeographic provinces:

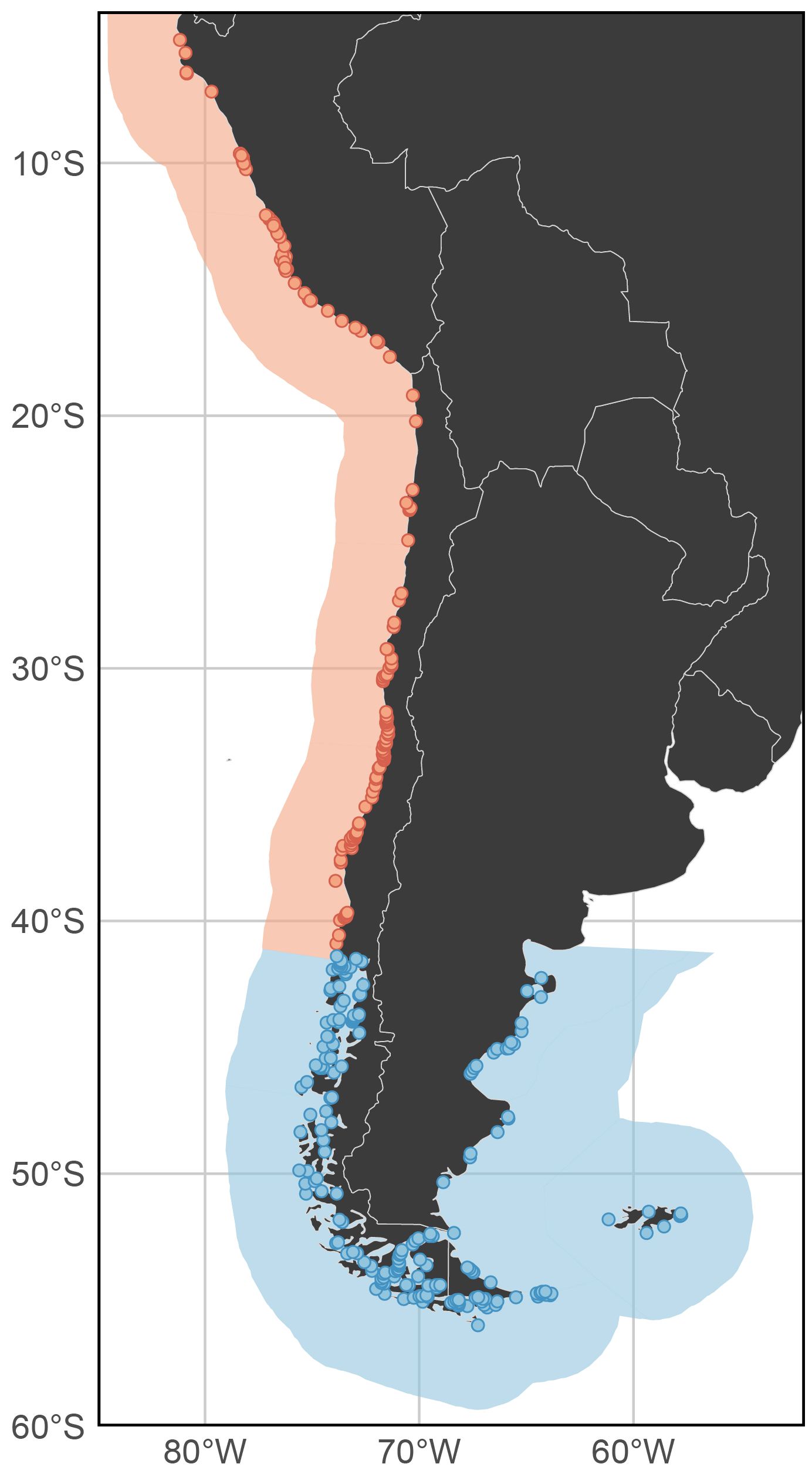

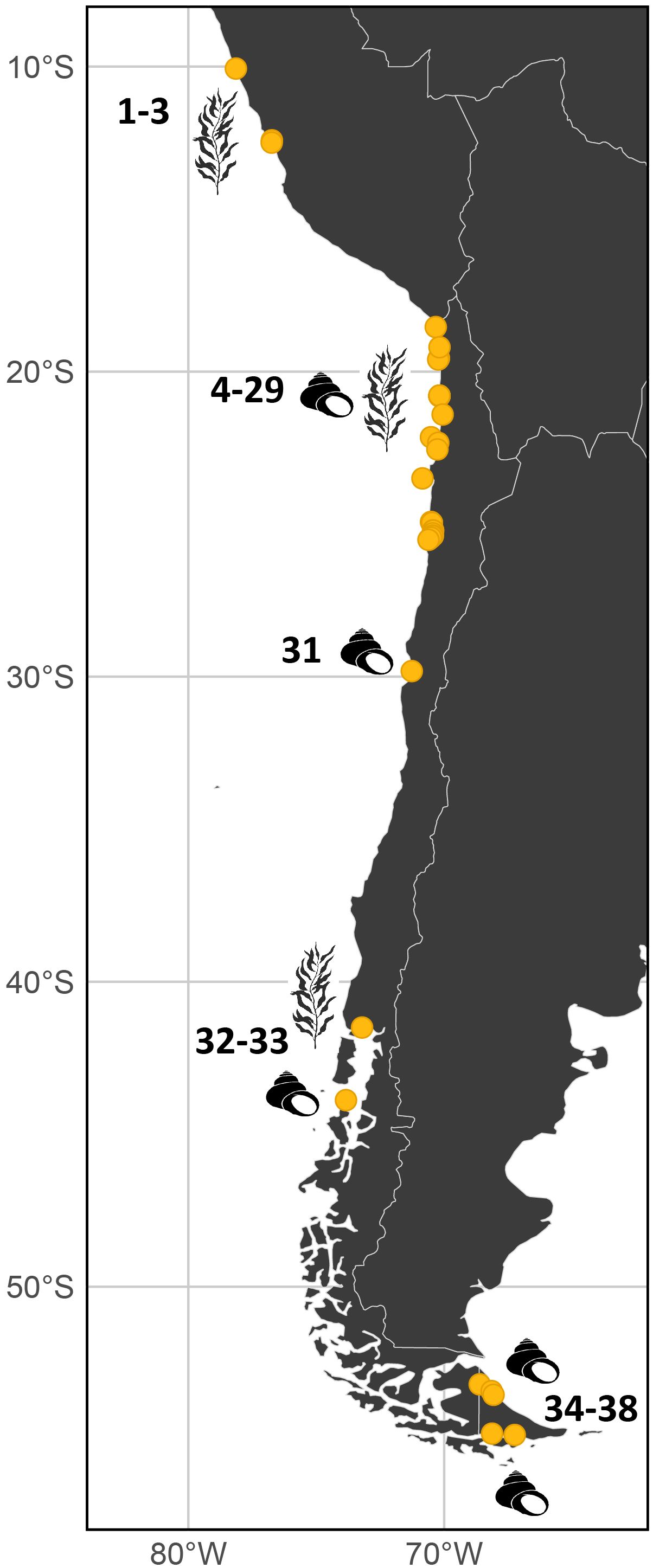

Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific, which includes records from Peru and north-central Chile, and the Magellanic, encompassing records from southern Chile and Argentina. Following these filters and classification process, we retained a total of 313 occurrences, with 161 records from the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific and 152 to the Magellanic Ecoregion. The distribution of the final records closely aligns with historical patterns documented in previous studies (Wernberg et al., 2019) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of kelp forest occurrences in South America since 1980, obtained from GBIF and used in the model of this study. The map also shows the two coastal biogeographic provinces relevant to the study area: the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific (light red) and the Magellanic Province (blue).

2.2 Environmental predictors

We obtained paleo-sea surface temperature (SST) data from the PMIP4, a subset of CMIP6 simulations (Kageyama et al., 2018). For the Medieval Warm Period (MWP; 850–1250 AD), we used reconstructions from the ACCESS-ESM1.5 model, which provides ocean fields at a spatial resolution of 1° (approximately 100 km at the equator) (Ziehn et al., 2020). For the Mid-Holocene (6000–5900 BP) and the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; 21,000–20,901 BP), we used simulations from the MIROC-ES2L model, available globally at 0.5° resolution (approximately 55 km at the equator) (Ohgaito et al., 2019). These datasets were accessed via the Earth System Grid Federation (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/), providing consistent paleoclimate reconstructions. To standardize spatial resolution and projection across all datasets, we processed the SST variables using Climate Data Operators (CDO) (Schulzweida, 2023). Data processing was performed in R Studio (R Core Team, 2022), where for each grid cell and period, the minimum and maximum SST values were extracted to represent the range of past thermal conditions.

To ensure alignment between paleoenvironmental predictors and the distribution of kelp forests, we created a coastal mask using a high-resolution coastline layer from Natural Earth (http://naturalearthdata.com/). This mask incorporated key habitat characteristics relevant to kelp forest distribution, such as light availability and wave exposure (Steneck et al., 2002; Wernberg et al., 2019). A 100 km2 buffer was applied around the coastline to guarantee that at least one pixel of the paleo-SST variables overlapped with coastal areas of South America. We then manually validated the spatial consistency between species occurrences and the masked environmental layers to ensure accuracy in subsequent analyses. To the Last Glacial Maximum model, we incorporated the extent of the Patagonian ice sheet known to have persisted during this period, based on reconstructions by Hulton et al. (2002).

An important limitation of our approach is that sea-level changes associated with glacial–interglacial dynamics could not be directly resolved at the spatial scale of the PMIP4 simulations. The MIROC-ES2L model, for example, has an oceanic resolution of 1° (100 km per pixel), with grid cells representing offshore waters rather than nearshore environments. Nevertheless, the thermal signal of these offshore pixels can reasonably be assumed to influence adjacent coastal ecosystems, including kelp forests, given the broad spatial scales of ocean–atmosphere interactions represented in these models. By focusing on offshore predictors, our approach avoids the additional uncertainties introduced by attempting to reconstruct shifting paleoshorelines (Lambeck et al., 2014), while still capturing the large-scale environmental gradients most relevant to kelp distribution. Although this means that local shoreline displacement and the inundation or exposure of shallow habitats cannot be explicitly modeled, these processes are partly embedded in the broader PMIP4 reconstructions. Thus, while some uncertainty remains—particularly along narrow coastal margins—the framework provides a consistent basis for comparing kelp habitat suitability across glacial–interglacial cycles.

Temperature is a primary driver of kelp forest distribution, influencing physiological performance, ecological interactions, and nutrient dynamics (Steneck et al., 2002; Smale, 2020; Fram et al., 2008; Reed and Brzezinski, 2009). Moreover, previous studies on different kelp species have repeatedly identified SST as the most influential variable in determining their spatial distribution (Martínez et al., 2018; Jayathilake and Costello, 2021; Assis et al., 2023; González-Arangón et al., 2024; Assis et al., 2024). While highly collinear variables are often excluded from species distribution models, their inclusion can be justified when they represent key ecological determinants (Sillero and Barbosa, 2021). In this case, minimum SST is closely linked to nutrient-rich upwelling events, which are essential for the reproduction, growth and persistence of kelp forests (Narayan et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2007b). Conversely, maximum SST plays a critical role in defining the low-latitude distribution limits of kelp forest, as thermal stress imposes both physiological and ecological constraints on its survival (Ladah et al., 1999; Edwards, 2004). Based on these findings, we selected SST minimum (°C, SSTmin) and SST maximum (°C, SSTmax) as the key predictors for species distribution modeling (SDM). These layers were clipped using the coastal mask and visually inspected to confirm their alignment with kelp forest occurrences and coastal features.

2.3 Model performance, evaluation, threshold and projections

The current distribution of South American kelp forests was estimated using Maxent 3.4.1 (Phillips et al., 2021), incorporating the filtered GBIF occurrences and predictor variables. Maxent is a SDM approach based on machine learning that uses presence-only data to estimate habitat suitability by identifying the most uniform (maximum entropy) probability distribution, constrained by the environmental conditions at known occurrence sites (Phillips et al., 2006; Phillips and Dudík, 2008). This approach predicts areas with similar environmental conditions to those where the species has been observed, even when available data are incomplete or limited (Elith et al., 2011; Merow et al., 2013). The model was configured with 10 replicate runs under a cross-validation framework and a maximum of 1000 iterations. To characterize the range of available environmental conditions, we randomly selected up to 10,000 background points from grid cells lacking kelp occurrences (Phillips et al., 2004, 2006). These points were restricted to the coastal region defined in the study to ensure they represented relevant environmental conditions (Merow et al., 2013).

To project the historical distribution of kelp forests under past climate scenarios from PMIP4 (Kageyama et al., 2018), we selected SSTmin and SSTmax for the LGM, Mid-Holocene, and MWP. To account for the evolutionary history of kelp species in distinct biogeographic contexts, separate projections were conducted for the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific and Magellanic provinces (Spalding et al., 2007). The distribution maps, estimated habitat area, and spatial range for each scenario were generated using RStudio (R Core Team, 2022). For visualization purposes, we applied a smoothing technique to the Maxent model output, enhancing the clarity of the potential distribution maps of kelp forests.

For model evaluation, we used 70% of the occurrence data for training and retained the remaining 30% for validation (Phillips et al., 2006). Model accuracy was assessed using the area under the curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) (Peterson et al., 2008). The ROC curve and AUC provide a measure of model performance by evaluating the balance between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate), which reflects the model’s ability to distinguish presences from background points (Phillips et al., 2004; Lawson et al., 2014). Because AUC calculations depend on background data, careful delineation of the study area is crucial to prevent an artificial increase in accuracy due to improper background selection (Merow et al., 2013). In this study, the background area was constrained to the defined coastline mask to avoid overestimating AUC values, following recommendations for presence-only models where the species’ distribution is large relative to the study area (Lobo et al., 2008).

To define suitable habitat in our study area, which was limited to the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific and Magellanic biogeographic provinces, we applied the “Maximum training sensitivity plus specificity” threshold. This method optimizes the trade-off between correctly predicting presence and minimizing false positives, providing a more reliable classification of suitable habitat while reducing overestimation in areas with limited environmental extrapolation (Liu et al., 2013). Given the spatial extent of this study, this threshold provided a more reliable representation of potential kelp forest distribution. The continuous Maxent output was transformed into a binary classification of presence and absence using the “Maximum training sensitivity plus specificity” threshold. The threshold values were 0.5028 for the ACCESS-ESM1–5 model in the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific province and 0.5623 for its projection in the Magellanic province. For the MIROC-ES2L model, the thresholds were 0.5785 in the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific and 0.582 in the Magellanic province. Only areas with values above these thresholds were considered suitable habitat for kelp species in this study.

2.4 Archaeological data

To support the results from the habitat suitability models, we incorporated archaeological evidence documenting human interactions with kelp forests. A comprehensive bibliographic review was conducted, focusing on peer-reviewed primary literature that provided specific chronological and contextual data. This search was carried out using Google Scholar with the following keywords: “archaeological kelp South America”, “shell middens South America”, “archaeological evidence kelp South America”, and “archaeological macroalgae South America”—with the latter refined to include only studies confirming the presence of kelp species. These same keyword combinations were also searched by replacing “South America” with specific countries of interest: Peru, Chile, and Argentina, to capture more localized studies. Only peer-reviewed primary archaeological studies were included, excluding reviews, non-scientific reports, and grey literature, to ensure data reliability and reproducibility. Studies were retained if they (i) presented clear evidence of human use or interaction with kelp forests, (ii) reported either direct remains of kelp species or associated taxa found in shell middens, and (iii) included precise spatial (geographic coordinates or mappable site descriptions) and temporal (radiocarbon or contextual dating) information.

The review yielded 21 scientific publications reporting 38 archaeological sites distributed along the Pacific coast of South America (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). These sites included both direct evidence of kelp use such as preserved remains of M. pyrifera, Lessonia spp., Durvillaea spp., or Eisenia spp. and indirect evidence, as for example of marine taxa ecologically associated with kelp forests. For each site, we extracted geographic coordinates, temporal range, and type of evidence (direct kelp remains or indirect proxy). To obtain a consistent temporal range in calibrated years before present (cal BP), uncalibrated radiocarbon dates were processed using OxCal (Ramsey, 2001), applying the Southern Hemisphere calibration curve SHCal04 (McCormac et al., 2004).

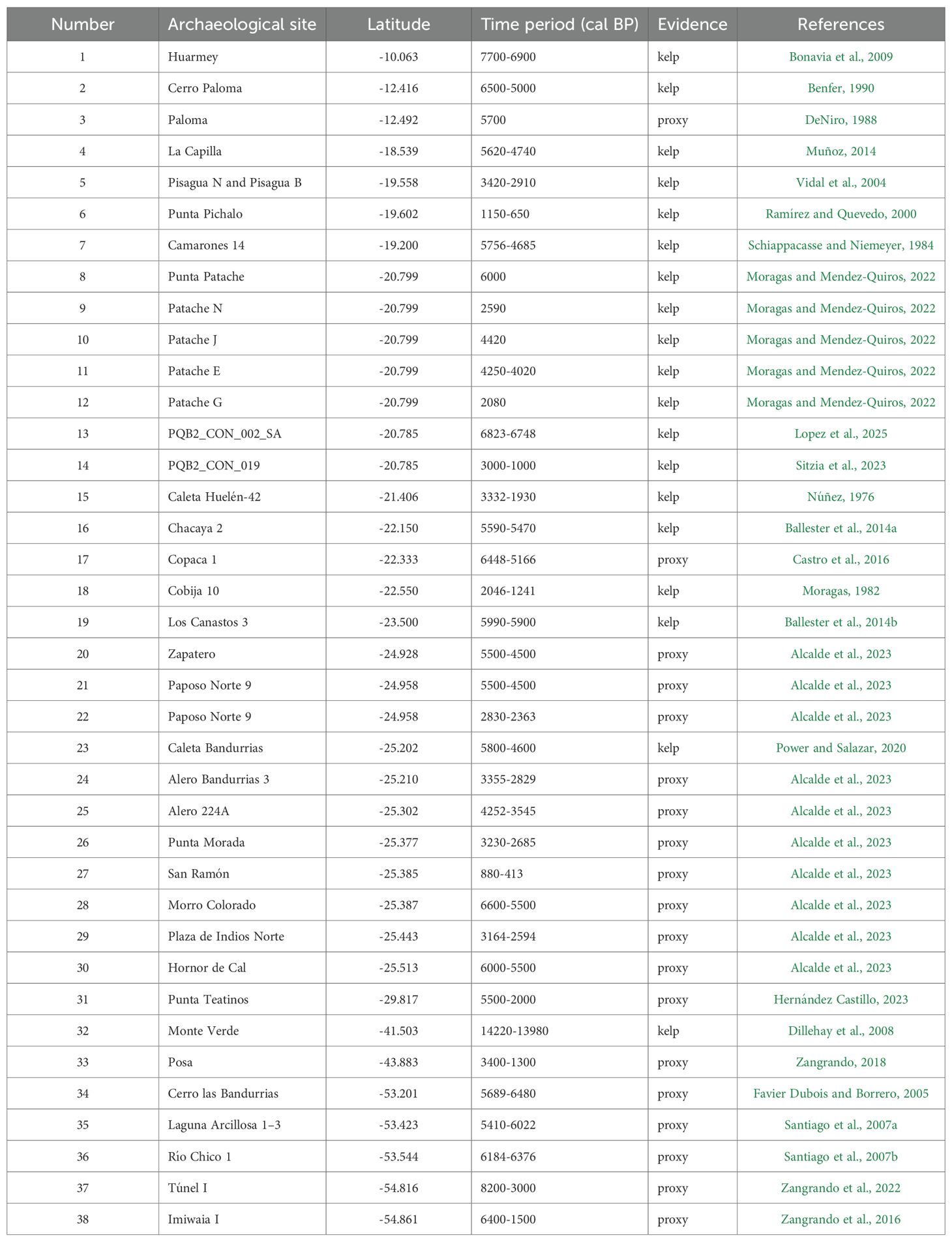

Table 1. Archaeological sites with kelp or proxy evidence along the South American coast during different Holocene periods.

For the purpose of spatial comparison with modeled kelp distributions, each archaeological area was treated as a single geographic point, even when multiple discrete occupations were reported within the same site. For example, Punta Patache includes several occupational components (N, J, E, G) with distinct radiocarbon dates. While all dates were included individually in the database to preserve temporal resolution and enable subsequent correlation with paleoclimatic models, they were aggregated spatially to a single point to simplify the mapping and visualization of human–kelp forest overlap.

This information enabled the spatial and temporal mapping of human–kelp forest interactions throughout the Holocene. Archaeological sites whose occupation dates overlapped with two modeled paleoclimatic scenarios—the Mid-Holocene and the MWP—were georeferenced and overlaid onto the corresponding modeled kelp forest distributions. This allowed us to visually assess the spatial correspondence between archaeological presence and areas of suitable kelp habitat, providing a contextual framework for understanding potential ecological and cultural interactions along the South American Pacific coast.

It is important to note that this connection between kelp SDMs and archaeological records represents an approximation rather than a precise chronological match. While the modeled periods could not align exactly with the occupation dates of some sites, the long-term resilience and persistence of kelp forests suggest that their distributional ranges would not have shifted drastically within such time spans. Likewise, archaeological chronologies incorporate inherent uncertainties, with calibrated radiocarbon dates reflecting ranges rather than exact years. Thus, this integration does not aim to track human migration or movement, but rather to provide an environmental framework within which coastal populations could have persisted through time. In this sense, the archaeological record serves as contextual evidence to interpret the modeled reconstructions, highlighting the existence of ecologically rich coastal areas—structured by kelp forests—that may have supported sustained human occupation.

3 Results

3.1 Paleodistribution of kelp forest in South America

The SDMs for past kelp forest distribution along western South America showed high AUC values, indicating strong model performance in distinguishing suitable from unsuitable habitat. For the MWP and Mid-Holocene scenarios, the AUC was 0.706 for the Warm Temperate Southeastern Pacific province and 0.816 for the Magellanic province. In the Last Glacial Maximum scenario, the AUC values were 0.714 and 0.882, respectively. These results suggest reliable predictive capacity across both regions, with slightly higher AUC values in the Magellanic province (likely reflecting greater environmental stability over time). The contribution of SST to past kelp forest distribution varied between predictors: SSTmin dominated (69.7% in MWP and Mid-Holocene; 98% in LGM), while SSTmax contributed minimally (30.3% in MWP/Mid-Holocene; 2% in LGM).

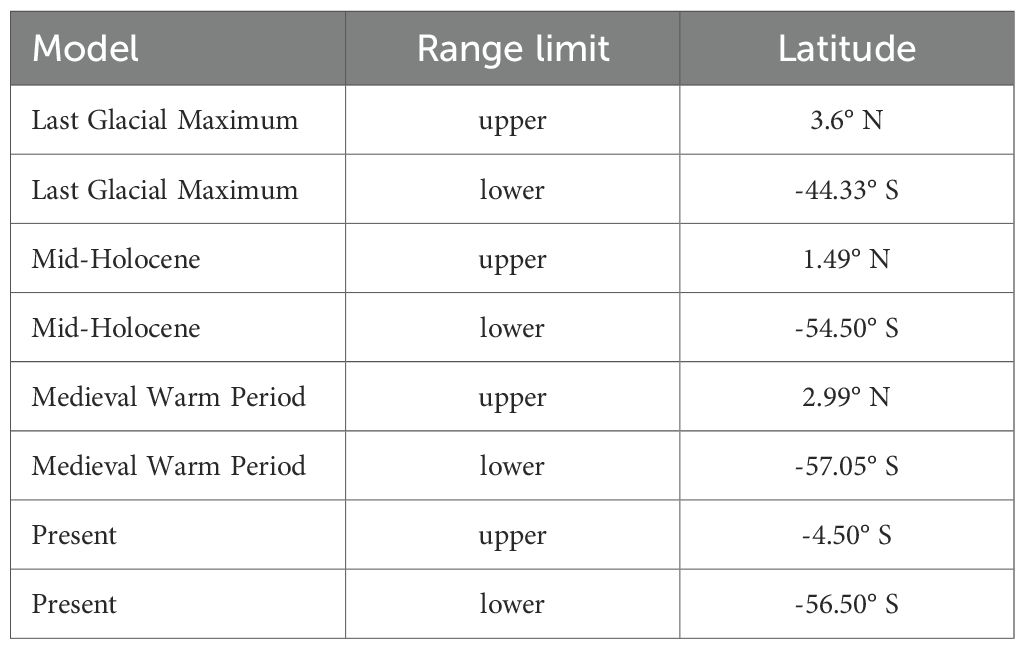

The latitudinal range of kelp forest habitat suitability in South America varied across past and present climate scenarios (Table 2, Figure 2). During the Last Glacial Maximum, the distribution spanned 47.93° of latitude, from 3.6°N to 44.33°S. In the Mid-Holocene, the range expanded to 55.99° (around the tip of the continent), extending from 1.49°N to 54.50°S. The MWP showed the widest distribution, covering 60.04° from 2.99°N to 57.05°S. In contrast, the present-day range has contracted to 52°, with the northern limit shifting southward to 4.5°S while the southern extent remains at 56.50°S.

Table 2. Latitudes degrees of the maximum range in the model distribution of kelp forest in South America for the Last Glacial Maximum, Mid-Holocene, Medieval Warm Period, and present.

Figure 2. Modeled distribution of suitable habitat for kelp forest in South America during the Last Glacial Maximum, Mid-Holocene, Medieval Warm Period, and the present. Suitable areas are shown in green, with the total range of potential distribution for each period indicated by a green bar on the left side of each map. For the LGM, known glaciated areas in Patagonia are depicted in white.

Beyond the latitudinal extent, our reconstructions revealed marked shifts in the continuity of kelp forest distribution across paleoclimatic periods (Figure 2). During the LGM, the northernmost modeled distribution extended to what is today the southern Colombian coast, though the pattern was fragmented and patchy. In northern Peru and Ecuador, kelp forests exhibited a relatively continuous potential distribution, which became interrupted toward southern Peru. With the exception of a small patch, the modeled range was absent around the Arica bight—at the border between southern Peru and northern Chile—before resuming along most of the Chilean coast. This distribution remained largely continuous until encountering the Patagonian ice sheet in the far south. Overall, the LGM scenario suggests a distribution characterized by large yet isolated patches along the southeastern Pacific coastline (Figure 2).

In contrast, the Mid-Holocene model revealed a more continuous distribution from southern Ecuador to southern South America, with only a localized gap in central Peru. A pronounced expansion was evident toward the southernmost regions of Patagonia, coinciding with the retreat of the western Patagonian ice sheet. Unlike the LGM scenario, the Mid-Holocene also revealed the emergence of a potential Atlantic distribution along the Argentine coast between approximately 40°S and 50°S including a small part of the Malvinas-Falklands.

A similar general pattern was recovered for the MWP with slight differences on the Pacific coast: a patch of newly suitable area appeared along the Colombian-Ecuadorian border and the gap in central Peru expanded relative to previous periods. On the Atlantic side, the distribution fragmented in two large patches. In the Magellanic region, kelp forests expanded further southward, reaching the polewardmost modeled range among all periods considered.

Finally, the present-day model exhibited two main clusters of kelp forest distribution in northern and southern Peru, separated by a region of unsuitable habitat around the Arica bight—similar to the LGM model. From northern Chile southward, the distribution was uninterrupted to the southern tip of the continent. Along the Atlantic coast, however, the predicted distribution became more patchy than during the MWP, indicating a possible long-term decline in habitat continuity.

3.2 Archaeological kelp-use evidence in South America

Archaeological evidence of past kelp use spans much of the Pacific coast of South America, although there remains a notable absence of published information from southern Peru, central Chile, and most of the Patagonian fjords (Figure 3). The temporal range of these records extends from 14,220-13,980 BP at Monte Verde in southern Chile to 880–413 BP at San Ramón in northern Chile (Table 1). Our literature review, identified a total of 38 archaeological sites, including 19 with direct evidence of kelp (e.g., preserved algal remains) and 19 based on indirect faunal or cultural evidence from shell middens (proxy). The complete table, including geographic coordinates and full references for each record, is available in the repository cited in the Data Availability Statement.

Figure 3. Archaeological sites in South America with direct or indirect evidence of kelp use. Each site is labeled with its corresponding reference number from Table 1. Sites with direct evidence of kelp are marked with a kelp icon, while those with indirect evidence—such as shell middens—are indicated with a shell icon.

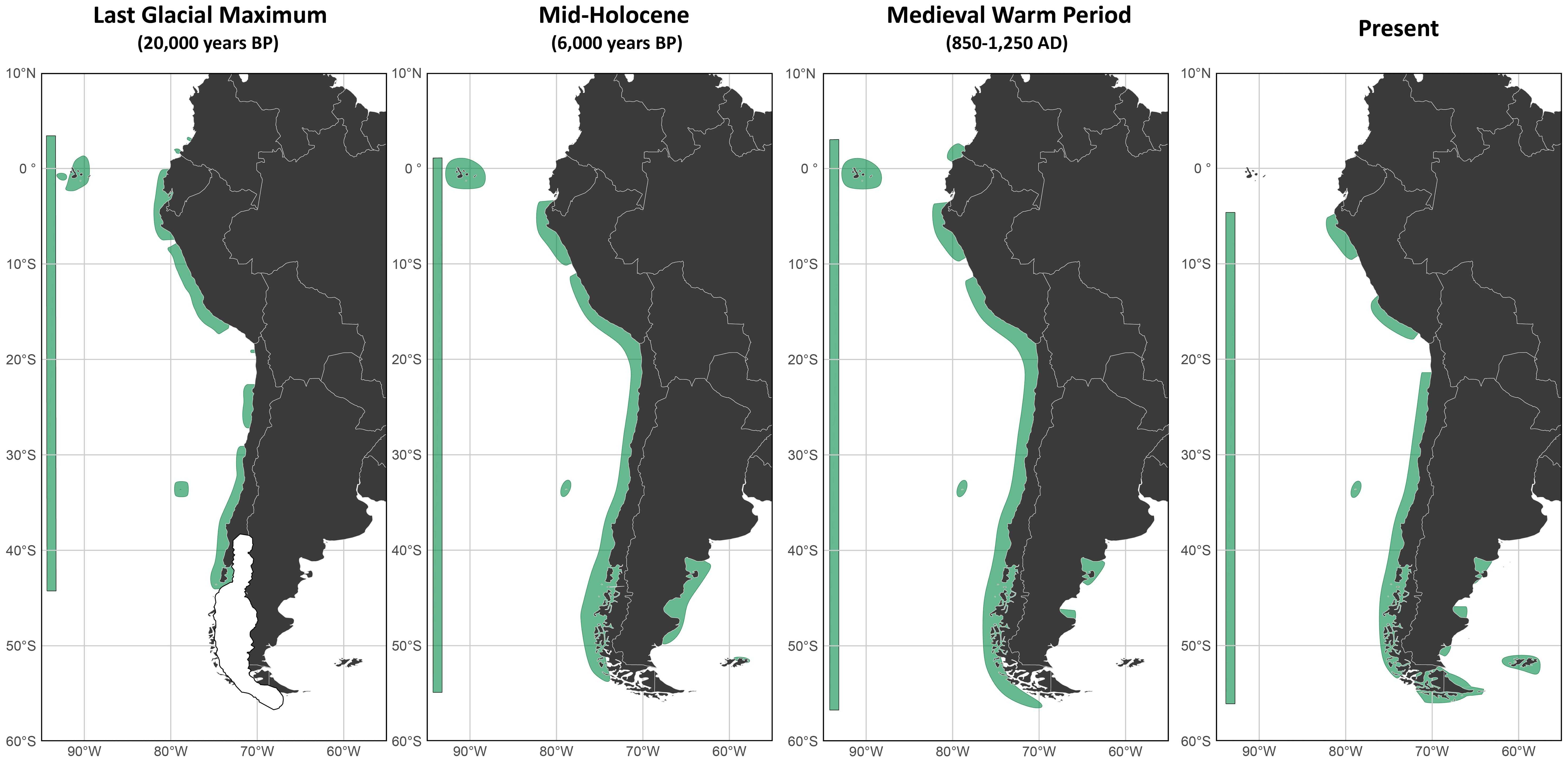

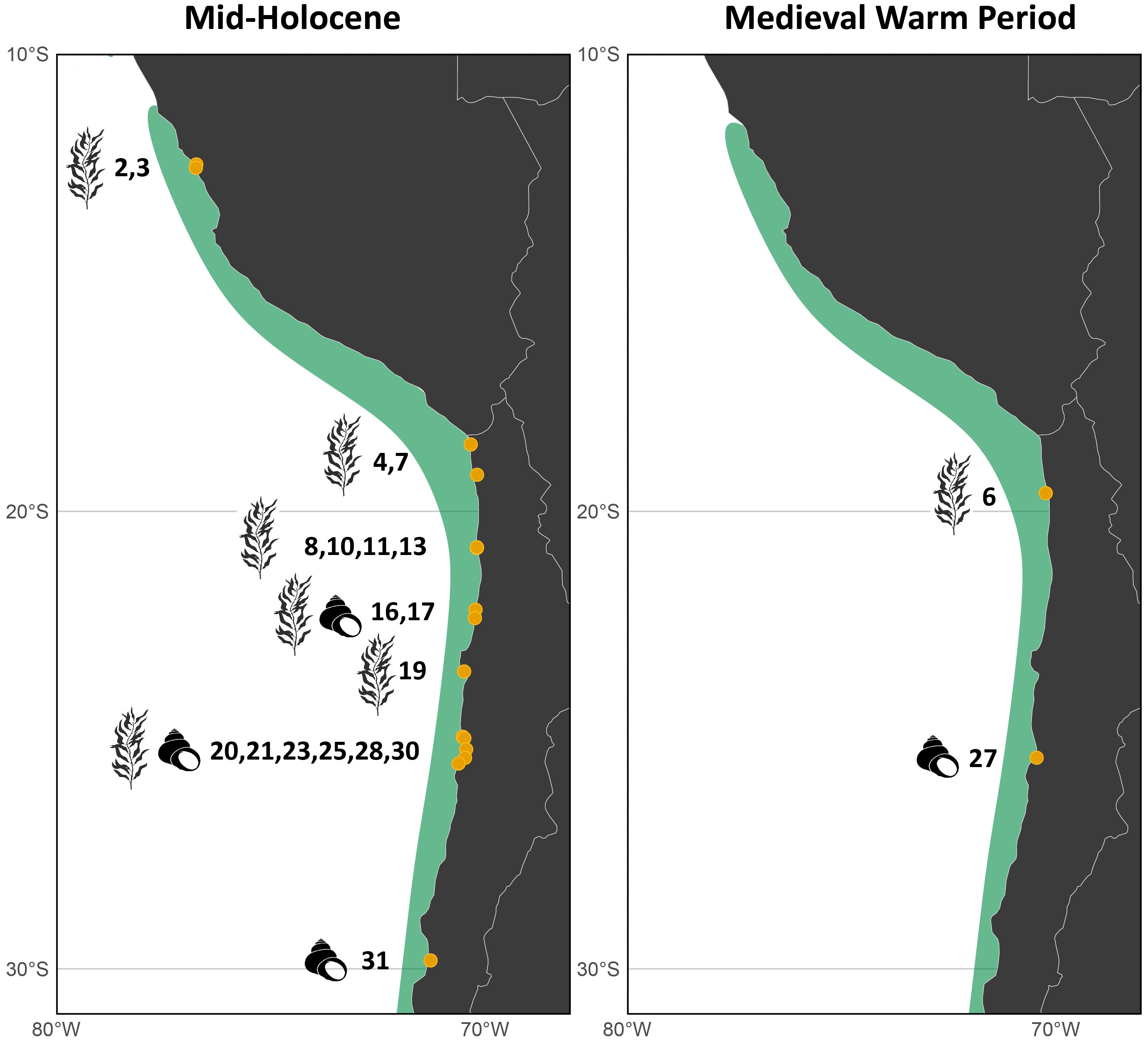

When comparing the archaeological record with the modeled past distributions of kelp forests, 23 sites overlapped both temporally and spatially with the Mid-Holocene scenario, whereas only two overlapped with the MWP (Figure 4). In both cases, the northern sites located between Peru and northern Chile fell within areas identified as suitable kelp habitat for the corresponding modeled period. Notably, Mid-Holocene archaeological sites were almost co-located with the northernmost limit of the modeled kelp distribution in Peru.

Figure 4. Species distribution models (SDMs) of kelp forest suitability for the Mid-Holocene and Medieval Warm Period in Peru and northern Chile, overlaid with archaeological sites containing direct or indirect evidence of kelp use. Sites with direct evidence are marked with a kelp icon, while those with indirect evidence—such as shell middens—are indicated with a shell icon.

Among the 23 archaeological sites that coincide with our Mid-Holocene habitat model, five are situated at the extreme southern end of the continent, in Tierra del Fuego (Table 1, sites 34–38), a region where our model does not predict suitable kelp forest habitat. This discrepancy is expected, as PMIP4 paleoclimatic variables have coarse spatial resolution (approximately 100 km at the equator; Ziehn et al., 2020) and do not adequately resolve the complex geomorphology of the Patagonian fjords. Consequently, this disagreement between models and data emphasizes the relevance of archaeological records for past ecological reconstructions and for improving ecological models, particularly in areas with complex hydrology, geomorphology, and oceanography. Because our objective is to capture large-scale changes in kelp forest distribution, rather than fine-scale patterns within narrow fjord systems, this region cannot be reliably represented by the model. For this reason, we excluded the Patagonian fjord region from the final figure to avoid misinterpreting model limitations as true absence of kelp.

Other archaeological sites fall outside the temporal ranges of our models. Two sites date to the interval between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Middle Holocene (site number 32 in Table 1), within which the site of Monte Verde stands out, dated to 14,220–13,980 BP. In addition, ten sites fall between the temporal ranges of the MWP and Middle Holocene models (Table 1): sites 5, 9, 12, 15, 18, 22, 24, 26, 29, and 33).

4 Discussion

The results from our models indicated that conditions for the persistence of kelp forests were maintained along the Pacific margin of South America from the LGM throughout the Holocene. The observed ecological continuity provides independent support for the KHH, which proposes that productive, kelp-dominated coastal ecosystems facilitated early human migration into the Americas along the Pacific Rim (Erlandson et al., 2015). During the LGM, the persistence of kelp-suitable habitats—although somewhat patchy—along the South American coastline provided predictable environments that could have supported early maritime adaptations and coastal dispersal (Erlandson et al., 2007, 2015). Kelp forests are known to sustain multiple resources—such as fish, invertebrates, marine mammals, and seaweeds—which would have offered reliable food sources for migrating populations (Kennett and Ingram, 1995; Schiel and Foster, 2015; Uribe et al., 2024). Our findings are consistent with the ecological plausibility of kelp forests acting not only as biodiversity hotspots but also as biocultural landscapes supporting early human settlement and movement.

Although most applications of the KHH have centered on the North Pacific—particularly Beringia and the North American coastline—archaeological evidence from California highlights the prolonged use and management of kelp forest resources. Studies from the California Channel Islands indicate intensive exploitation of marine resources linked to kelp ecosystems over the past 10,000 years (Ainis et al., 2019). Recent work by Mcfarland et al. (2025) shows that indigenous communities actively controlled sea urchin populations, preventing overgrazing and contributing to the long-term resilience of kelp forests. This evidence underscores the potential for sustainable human stewardship of coastal ecosystems.

Our results extend the geographic relevance of the KHH to the southeastern Pacific by demonstrating the persistence of suitable kelp habitats along the South American coast. Consistently suitable regions in our models coincide with archaeological sites dated from the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene (ca. 14,200–400 cal yr BP), including locations in Peru (Benfer, 1990; DeNiro, 1988; Bonavia et al., 2009), northern Chile (Núñez, 1976; Moragas, 1982; Schiappacasse and Niemeyer, 1984; Ramírez and Quevedo, 2000; Vidal et al., 2004; Muñoz, 2014; Ballester et al., 2014b, a; Castro et al., 2016; Power and Salazar, 2020; Moragas and Mendez-Quiros, 2022; Hernández Castillo, 2023; Alcalde et al., 2023; Sitzia et al., 2023; Lopez et al., 2025), southern Chile (Dillehay et al., 2008; Zangrando, 2018), and southern Patagonia (Favier Dubois and Borrero, 2005; Santiago et al., 2007a, b; Zangrando et al., 2016, 2022). Together, these findings expand the latitudinal scope of the KHH and provide robust model-based evidence that kelp-dominated seascapes could have served as viable corridors for early human settlement along the southeastern Pacific coast.

During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, modeled time window ∼21,000 years BP), kelp forests exhibited a fragmented distribution along the Pacific coast of South America, with multiple patches of suitable habitat. At low latitudes, suitable areas persisted along parts of the Ecuadorian coastline and possibly around the Galapagos´ Archipelago, consistent with hypotheses of localized kelp refugia in the region (Graham et al., 2007a). The recent discovery of mesophotic kelp species in the Galapagos´ supports the persistence of these forests under unique environmental conditions (Buglass et al., 2022), potentially as relicts of ancient equatorial populations. At low latitude on the mainland, the modeled suitability along southern Colombia and Ecuador may reflect kelp assemblages dominated by species with higher thermal affinity, such as Eisenia cokeri and E. gracilis (Hu et al., 2024; Ávila Peltroche et al., 2024). In Peru, E. cokeri forms extensive and structurally complex holdfast assemblages that sustain diverse benthic communities, acting as a key foundation species in ecosystems otherwise lacking functional redundancy (Uribe et al., 2024). Such productive and thermally tolerant kelp assemblages could likewise have provided stable and resource-rich habitats for early coastal communities along the low-latitude Pacific margin. At high latitudes, the poleward limit of modeled distributions coincided with the western Patagonian ice sheet (Hulton et al., 2002), suggesting that postglacial expansion likely tracked ice retreat, a pattern observed in modern Arctic ecosystems (Castro de la Guardia et al., 2023). Our findings align closely with projections for the kelp M. pyrifera by Assis et al. (2023), though our approach explicitly accounted for ice-sheet extent and biogeographical provinces, providing a more constrained view of high-latitude habitat availability. After the LGM, progressive glacial retreat modified coastal geomorphology, temperature, salinity, and light penetration; the photobiological strategies of M. pyrifera are known to sustain high physiological performance under such challenging conditions (Coral-Santacruz et al., 2024; Gómez et al., 2025).

The Mid-Holocene modeled window (∼6000 years BP) exhibited a broader latitudinal range of suitable kelp habitat compared to the LGM, reflecting the expansion of temperate conditions and the retreat of the western Patagonian ice sheet. Suitable habitats persisted around the Galapagos´ region and extended further poleward. Enhanced coastal upwelling in northern Chile and south-central Peru during this period (Salvatteci et al., 2019; Flores and Broitman, 2021) likely supported the persistence of kelp forests at lower latitudes, paralleling biomass increases documented for Northern Hemisphere populations (Graham et al., 2010). This poleward expansion trend culminated during the MWP, when modeled distributions reached their widest latitudinal extent across the southeastern Pacific. Although the coarse resolution of PMIP4 data limits detailed inferences in complex regions such as Patagonia (Kageyama et al., 2018), our reconstructions remain suitable for identifying large-scale distributional patterns through time.

Despite their near-continuous distribution along the Pacific coast of South America, direct archaeological evidence of kelp forest use remains sparse, likely due to taphonomic degradation, submerged coastal sites from postglacial sea-level rise, and historiographic biases (Flügel, 2012; Sturt et al., 2018). Most archaeological records are concentrated in the hyper-arid northern coast of Chile, where exceptional preservation conditions favor the survival of organic remains (Latorre et al., 2013). In contrast, more humid regions such as central Chile show a marked absence of direct kelp evidence despite ecological suitability—possibly due to taphonomic loss or site submergence (Carabias et al., 2014; López Mendoza et al., 2018). In our study, changes in sea level associated with postglacial dynamics were not explicitly incorporated into the paleodistribution models due to the coarse resolution of the PMIP4 predictors (Kageyama et al., 2018). While sea-level rise has been documented in other studies (Kinlan et al., 2005; Lambeck et al., 2014), the first available grid cells in our datasets are located offshore, limiting the representation of narrow coastal margins and submerged landscapes. Addressing these gaps will require targeting submerged landscapes using new interdisciplinary methods (Rodriguez-Schrader, 2025; Erlandson et al., 2025). Beyond these taphonomic constraints, cultural and historiographic biases may have further contributed to the underrepresentation of macroalgae in the archaeological narrative. The association of macroalgae with marginalized groups, together with the historical underestimation of their importance in daily life as both food and raw material, may have contributed to their devaluation in colonial texts and their subsequent exclusion from academic discourse (Araos et al., 2018).

Our analysis focused strictly on kelp forests, incorporating direct and indirect evidence (e.g., shell middens) from 38 archaeological sites along the South American coast (Figure 3). A clear spatial bias emerges: direct kelp remains are more frequent at lower latitudes, while kelp-associated taxa dominate in southern regions—likely reflecting differential preservation patterns of organic remains. In spite of these challenges, several archaeological findings highlight the long-standing importance of kelp in early coastal societies of South America (Dillehay et al., 2008; Alcalde et al., 2023; Sitzia et al., 2023). The lowest-latitude archaeological evidence of kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) in our study comes from Huarmey, Peru (10°S) (Bonavia et al., 2009). Although its chronology predates the Mid-Holocene interval represented in our models, the recovery of substantial quantities of kelp at this site indicates both the local persistence of these forests and their importance to coastal populations in this region (Bonavia et al., 2009). Radiocarbon data places the initial human settlement of the south of the continent shortly after the LGM, around 15,500 cal BP (Prates et al., 2020). The most compelling evidence at this early stage is Monte Verde, a site in southern Chile dated to approximately 14,500 cal years BP, where multiple kelp species were recovered from stratified cultural layers (Dillehay et al., 2008). These remains indicate the use of kelp not only as a food source but also for medicinal purposes, underscoring its functional and cultural relevance to early populations (Dillehay et al., 2008). Monte Verde’s age and location support the KHH highlighting kelp forests as a stable coastal environment that likely facilitated early human dispersal in South America, as also evidenced by the persistent habitat suitability revealed in our SDMs during the LGM.

Our paleodistribution model for the Mid-Holocene identified 19 archaeological sites that coincide both temporally and spatially with areas of suitable kelp habitat. This period was marked by significant climatic shifts, including progressive sea-level rise, increasing aridity in regions such as Peru and northern Chile, and the onset of the modern El Nino˜ Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climatic pattern, all of which likely affected freshwater availability and marine productivity along the Pacific coast (Grosjean et al., 2003; Wanner et al., 2008). These environmental changes have been linked to demographic contractions and societal transformations across South America during the Mid-Holocene (Barberena et al., 2017; Riris and Arroyo-Kalin, 2019). In central Peru, isotopic analyses from sites like Huaca Prieta point to strong marine subsistence strategies during this period, possibly extending inland through trade (Benfer, 1990; DeNiro, 1988; Tung et al., 2020). However, rising environmental pressures—including increased aridity, El Nino-associated˜ flooding, and the formation of beach ridges—eventually led to the gradual abandonment of coastal preceramic settlements and ceremonial sites along the Pacific coast (Sandweiss et al., 2007, 2009). At the Peruvian margin, paleoceanographic data from sediment cores suggest intensified upwelling during the Mid-Holocene, conditions that could have favored kelp forest persistence (Salvatteci et al., 2019). Yet, at lower latitudes (9–11°S), reconstructed sea surface temperatures of 22–23 °C approached the upper thermal tolerance of some kelp species, such as M. pyrifera (Zimmerman and Kremer, 1984; Rodriguez et al., 2016), coinciding with the latitudinal break in kelp distribution predicted by our models (Salvatteci et al., 2019). In these warmer environments, more heat-tolerant kelp species such as the genus Eisenia may have played a crucial role in maintaining stable marine resources for early coastal populations (Hu et al., 2024; Ávila Peltroche et al., 2024).

Similar climatic shifts are documented along the northern Chilean coast, where warmer sea surface temperatures were observed at the onset of the Mid-Holocene, followed by a general cooling trend throughout the remainder of the period (Flores and Broitman, 2021). These thermal changes, supported by sedimentary evidence, suggest a weakening of coastal upwelling systems, with implications for marine productivity and the spatial distribution of nearshore fisheries (Mohtadi et al., 2004; Latorre et al., 2017; Flores and Broitman, 2021). Such environmental variability is reflected in archaeological shell middens, where changes in species composition and abundance have been interpreted as responses to ecological stress and as indicators of community-based management practices during times of diminished marine productivity (Santoro et al., 2017). At 20°S on the northern Chilean coast, zooarchaeological evidence reveals adaptive foraging strategies of coastal fauna and a shift toward permanent settlements strategically located near freshwater and productive nearshore environments during the Middle Holocene (Lopez et al., 2025). Recent findings from the Atacama Desert reveal that major Mid-Holocene shifts in marine productivity prompted a suite of cultural adaptations, including changes in subsistence practices, diversification of fishing technologies, and transformations in funerary traditions, reflecting the adaptive strategies coastal hunter-gatherer groups deployed during periods of pronounced environmental change (Godoy-Aguirre et al., 2025). In southern Patagonia, changes in ichthyoarchaeological records during the Mid- to Late Holocene indicate a shift from demersal to nearshore species linked to subtidal kelp forests, reflecting broader ecosystem transformations (Torres et al., 2024). Collectively, these findings suggest that climatic variability during the Mid-Holocene reshaped coastal environments and resource use, influencing human adaptation strategies along the Pacific margin (Erlandson and Fitzpatrick, 2006; Graham et al., 2010; Méndez et al., 2015; Santoro et al., 2017; Godoy-Aguirre et al., 2025).

In contrast to the Mid-Holocene, only two archaeological sites coincide temporally and spatially with the distribution of suitable kelp habitat during the MWP. This pre-Columbian interval, however, is rich in ethnohistorical accounts describing the extraction, processing, and differentiated use of various marine algae species by indigenous populations (Araos et al., 2018). Historical records document the intensive use of algae not only by coastal groups such as the Lafkenche, Huilliche, and canoe-faring peoples of Patagonia, but also by inland communities, revealing dynamic exchange networks between coastal, valley, and highland populations that persist to this day in southern Chile (Masuda, 1986, 1988). Similar seasonal practices have been proposed during the pre-Hispanic Peru, where highland pastoralists may have descended with their llama herds to coastal areas to harvest kelp (DeNiro, 1988). These patterns align with isotopic evidence from northern Chile indicating marine foraging strategies and coastal dietary contributions in both camelids and humans (Bonilla et al., 2016). Despite the apparent intensity of prehistoric kelp harvesting, archaeological and paleoecological evidence suggests that such activities did not significantly alter coastal ecosystems (Rivadeneira et al., 2010). This stands in sharp contrast to the present day, where preliminary data indicate that overfishing has triggered a major, unprecedented shift in Chilean coastal biodiversity over the past few decades to centuries (Rivadeneira et al., 2010).

Along the equatorial margin, our reconstructions place the Ecuadorian coast at the low-latitude limit of past kelp-suitable habitat. During the LGM, the model indicates patchy suitability extending into southern Ecuador, but this signal weakens markedly in subsequent periods, aligning with the expected thermal constraints on kelp persistence near the equator. Archaeological evidence from this region is consistent with this pattern. The early Holocene Las Vegas Complex of Santa Elena (Stahl and Stothert, 2020)—one of the best-studied cultural sequences in a fully equatorial setting from the early Holocene—shows no kelp remains or kelp-associated shellfish in its assemblages (Sarma, 1974; Stahl and Stothert, 2020). Instead, its faunal remains are dominated by soft-bottom and mangrove-dwelling species, with the few rocky-shore taxa representing tropical communities. Farther north, additional sites document intensive marine exploitation but likewise emphasize tropical resources rather than cold-water kelp forest species (Favier Dubois et al., 2019). Together, these findings support the interpretation that kelp forests did not necessarily contributed to early coastal subsistence strategies in equatorial South America, in agreement with the modeled northern limit of suitable kelp habitat.

Finally, the present modeled range matches the current known distribution of kelp forests (Wernberg et al., 2019; González-Arangón et al., 2024), reinforcing model reliability. Across all periods, we observed a consistent poleward shift in kelp forest distributions, reflecting broader global patterns linked to climate warming (Wernberg et al., 2016; Smale and Moore, 2017; Smale, 2020). In South America, the northern range limit of M. pyrifera has already contracted from historical records near 4–6°S to its current boundary near Lima, Peru (12°S) (Juhl-Noodt, 1958; Buschmann et al., 2004; Carbajal Enzian and Gamarra, 2018). This long-term contraction, combined with nearly continuous habitat availability along the Pacific coast, underscores the ecological importance of kelp forests as persistent resources and potential migratory corridors for coastal populations over millennia.

5 Conclusion

By integrating archaeological evidence with ecological modeling, this study highlights the potential of SDMs to reconstruct past seascapes and elucidate long-term human–environment interactions. Our results demonstrate that kelp forests likely provided continuous, productive, and ecologically stable habitats along the Pacific coast of South America throughout key climatic periods—including the LGM, Mid-Holocene, and MWP. This continuity reinforces the ecological plausibility of the KHH, suggesting that kelp-dominated coastal corridors facilitated maritime migrations and sustained human settlement across diverse temporal and geographic contexts. Despite regional gaps in the archaeological record, persistent habitat suitability revealed by our models—coupled with archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence—supports the interpretation of kelp forests as both biocultural landscapes and viable migration routes. Our findings extend the KHH to South America, suggesting that these corridors were mostly continuous but likely fragmented during warm periods, and shaped the dynamics of human dispersal. This highlights the importance of combining ecological and archaeological approaches to better understand ancient coastal migrations and emphasizes the enduring role of kelp forests as key connectors between marine ecosystems and human history.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DG-A: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. CF: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FT: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. BB: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. FT was supported by National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) by Beca Doctorado Nacional (21240418, 23250349). BB acknowledges support from FONDECYT 1221699 and the Millennium Science Initiative Program – ICN2019–015 and NCN19 153.

Acknowledgments

Finally, we are profoundly grateful to the reviewers for their careful reading and insightful suggestions, which significantly improved the manuscript. In particular, we thank them for highlighting overlooked archaeological evidence and additional distributional records of Eisenia, enabling a more robust integration of ecological and archaeological data.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools were used to assist in improving the English language, refining grammar, and enhancing the clarity and readability of the manuscript text. All scientific content, data analysis, interpretation of results, and conclusions were entirely conceived, written, and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2025.1720175/full#supplementary-material

References

Ainis A. F. and Erlandson J. M. (2025). “The use of seaweeds and marine plants by island and coastal peoples in the past,” in The oxford handbook of island and coastal archaeology (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197607770.013.9

Ainis A. F., Erlandson J. M., Gill K. M., Graham M. H., and Vellanoweth R. L. (2019). “The potential use of seaweeds and marine plants by native peoples of Alta and Baja California,” in An archaeology of abundance: reevaluating the marginality of california’s islands. Eds. Braje T. J. and Erlandson J. M. (University Press of Florida, Gainesville), 135–170.

Ainis A. F., Vellanoweth R. L., Lapeña Q. G., and Thornber C. S. (2014). Using non-dietary gastropods in coastal shell middens to infer kelp and seagrass harvesting and paleoenvironmental conditions. J. Archaeological Sci. 49, 343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.024

Alcalde V., Flores C., Guardia J., Olguín L., and Broitman B. R. (2023). Marine invertebrates as proxies for early kelp use along the western coast of South America. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1148299. doi: 10.3389/feart.2023.1148299

Araos F., Borie C., Romo M., Lira N., and Duarte A. (2018). Algas: breves antecedentes etnográficos y arqueológicos. FOGÓN. Rev. Internacional Estudio las Tradiciones 1, 40–52.

Arriaza B. and Standen V. (2009). “Catálogo Momias Chinchorro. Cuerpos con momificación artificial,” in Serie Científica del Centro de Investigaciones del Hombre del Desierto (CIHDE) (Museo Arqueológico Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Chile).

Assis J., Alberto F., Macaya E. C., Castilho Coelho N., Faugeron S., Pearson G. A., et al. (2023). Past climate-driven range shifts structuring intraspecific biodiversity levels of the giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) at global scales. Sci. Rep. 13, 12046. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39231-5

Assis J., Fragkopoulou E., Gouvêa L., Araújo M. B., and Serrão E. A. (2024). Kelp forest diversity under projected end-of-century climate change. Diversity Distributions 30, e13837. doi: 10.1111/ddi.13837

Austin M. P. (2002). Spatial prediction of species distribution: an interface between ecological theory and statistical modelling. Ecol. Model. 157, 101–118. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00205-3

Ávila Peltroche J., Avalos M.-L., and Scholl Chirinos J. (2024). Concise review of the kelp genus Eisenia areschoug. J. Appl. Phycology 36, 2397–2416. doi: 10.1007/s10811-024-03264-4

Bakun A. (1990). Global climate change and intensification of coastal ocean upwelling. Science 247, 198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.247.4939.198

Ballester B., Clarot A., Bustos V., Llagostera A., and Garcés H. (2014a). Arqueología de la prehistoria de la pen´ınsula de mejillones: el campamento de los canastos 3 desde sus cuadernos de campo y materiales de museo. Boletín la Sociedad Chil. Arqueología, 5–21.

Ballester B., Clarot A., and Bustos V.. (2014b). Chacaya 2: Reevaluación de un campamento arcaico tardío, (6000 al 4000 cal ap) de la costa de mejillones, ii región, Chile. Werkén, 31–48.

Barberena R., Méndez C., and de Porras M. E. (2017). Zooming out from archaeological discontinuities: The meaning of mid-holocene temporal troughs in south american deserts. J. Anthropological Archaeology 46, 68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2016.07.003

Barbosa A. M., Real R., and Vargas J. M. (2010). Use of coarse-resolution models of species’ distributions to guide local conservation inferences. Conserv. Biol. 24, 1378–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01517.x

Benfer R. A. (1990). The preceramic period site of Paloma, Peru: Bioindications of improving adaptation to sedentism. Latin Am. Antiquity 1, 284–318. doi: 10.2307/971812

Bonavia D., Grobman A., Johnson-Kelly L. W., Jones J. G., Ortega Y. R., Patrucco R., et al. (2009). Historia de un campamento del Horizonte Medio de Huarmey, Peru´ (pv35-4). Bull. l’Institut franc¸ais d’études andines 38, 237–287. doi: 10.4000/bifea.2636

Bonilla M., d. C. D.-Z., Drucker D. G., Richardin P., Silva-Pinto V., Sepúlveda M., et al. (2016). Marine food consumption in coastal northern Chilean (Atacama Desert) populations during the formative period: Implications of isotopic evidence (c, n, s) for the neolithic process in south central andes. J. Archaeological Science: Rep. 6, 768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.10.033

Borie C., Araos F., Romo M., Lira N., and Duarte A. (2006). “Potencialidades, usos y evidencias de explotación de algas marinas: antecedentes etnográficos y arqueológicos, implicancias y líneas de investigación,” in Actas del XVII Congreso de Arqueología Chilena (Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia), 1191–1201.

Buglass S., Kawai H., Hanyuda T., Harvey E., Donner S., de la Rosa J., et al. (2022). Novel mesophotic kelp forests in the Galápagos Archipelago. Mar. Biol. 169, 156. doi: 10.1007/s00227-022-04092-7

Buschmann A. H., Vásquez J. A., Osorio P., Reyes E., Filún L., Hernández-González M. C., et al. (2004). The effect of water movement, temperature and salinity on abundance and reproductive patterns of Macrocystis spp. (phaeophyta) at different latitudes in Chile. Mar. Biol. 145, 849–862. doi: 10.1007/s00227-004-1387-z

Carabias D., Cartajena I., Simonetti R., López P., Morales C., and Ortega C. (2014). “Submerged paleolandscapes: Site gnl quintero 1 (gnlq1) and the first evidences from the Pacific Coast of south America,” in Prehistoric archaeology on the continental shelf: a global review (New York, NY, USA: Springer), 131–149.

Carbajal Enzian P. and Gamarra A. (2018). Guía para recolección y reconocimiento de macroalgas pardas comerciales del Perú. Tech. rep (Callao, Peru: Instituto del Mar del Peru´ (IMARPE).

Carré M., Jackson D., Maldonado A., Chase B. M., and Sachs J. P. (2016). Variability of 14C reservoir age and air-sea flux of CO2 in the Peru-Chile upwelling region during the past 12,000 years. Quaternary Res. (United States) 85, 87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2015.12.002

Castro V., Aldunate C., Varela V., Olguín L., Andrade P., García-Albarido F., et al. (2016). Ocupaciones arcaicas y probables evidencias de navegacion´ temprana en la costa arreica de antofagasta, Chile. Chungara´ (Arica) 48, 503–530. doi: 10.4067/S0717-73562016005000039

Castro de la Guardia L., Filbee-Dexter K., Reimer J., MacGregor K. A., Garrido I., Singh R. K., et al. (2023). Increasing depth distribution of arctic kelp with increasing number of open water days with light. Elementa: Sci. Anthropocene 11, 51. doi: 10.1525/elementa.2022.00051

Coral-Santacruz D., Méndez F., Marambio J., Haye P. A., Bahamonde F., and Mansilla A. (2024). Effects of glacial melting on physiological performance of Macrocystis pyrifera in the fjord of the mountains, magellanic sub-antarctic ecoregion, Chile. J. Appl. Phycology 36, 3637–3648. doi: 10.1007/s10811-024-03362-3

Cuba D., Guardia-Luzón K., Cevallos B., Ramos-Larico S., Neira E., Pons A., et al. (2022). Ecosystem services provided by kelp forests of the humboldt current system: A comprehensive review. Coasts 2, 259–277. doi: 10.3390/coasts2040013

DeNiro M. J. (1988). “Marine food sources for prehistoric coastal Peruvian camelids: Isotopic evidence and implications,” in Economic prehistory of the central andes. Ed. Sanders W. T., et al (Oxford, UK: BAR International Series), 119–128.

Dillehay T. D. (1997). The battle of monte verde. Sciences 37, 28–33. doi: 10.1002/j.2326-1951.1997.tb03283.x

Dillehay T. D., Ramírez C., Pino M., Collins M. B., Rossen J., and Pino-Navarro J. D. (2008). Monte verde: Seaweed, food, medicine, and the peopling of South America. Science 320, 784–786. doi: 10.1126/science.1156533

Edwards M. S. (2004). Estimating scale-dependency in disturbance impacts: El niños and giant kelp forests in the northeast pacific. Oecologia 138, 436–447. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1452-8

Eger A. M., Marzinelli E. M., Beas-Luna R., Blain C. O., Blamey L. K., Byrnes J. E., et al. (2023). The value of ecosystem services in global marine kelp forests. Nat. Commun. 14, 1894. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37303-7

Elith J., Phillips S. J., Hastie T., Dudík M., Chee Y. E., and Yates C. J. (2011). A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists: Statistical explanation of MaxEnt. Diversity Distributions 17, 43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x

Elsmore K., Nickols K. J., Miller L. P., Ford T., Denny M. W., and Gaylord B. (2024). Wave damping by giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera. Ann. Bot. 133, 29–40. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcad226

Erlandson J. M. (2013). “After clovis-first collapsed: Reimagining the peopling of the americas,” in Paleoamerican odyssey. Eds. Jenkins D. L., Davis L. G., and Stafford T. W. (College Station, TX, USA: Texas A&M University Press), 127–131.

Erlandson J. M., Braje T. J., Gill K. M., and Graham M. H. (2015). Ecology of the kelp highway: Did marine resources facilitate human dispersal from northeast asia to the americas? J. Island Coast. Archaeology 10, 392–411. doi: 10.1080/15564894.2014.1001923

Erlandson J. M. and Fitzpatrick S. M. (2006). Oceans, islands, and coasts: Current perspectives on the role of the sea in human prehistory. J. Island Coast. Archaeology 1, 5–32. doi: 10.1080/15564890600639504

Erlandson J. M., Fitzpatrick S. M., Gill K. M., Kirch P. V., Ruiz J. T., Thompson V. D., et al. (2025). Rising seas endanger maritime heritage. Science 387, 482. doi: 10.1126/science.adl1790

Erlandson J. M., Graham M. H., Bourque B. J., Corbett D., Estes J. A., and Steneck R. S. (2007). The kelp highway hypothesis: Marine ecology, the coastal migration theory, and the peopling of the americas. J. Island Coast. Archaeology 2, 161–174. doi: 10.1080/15564890701628612

Favier Dubois C. M. and Borrero L. A. (2005). Playas de acreción: cronología y procesos de formación del registro arqueológico en la costa central de la bahía san sebastián, tierra del fuego (Argentina). Magallania 33, 93–108.

Favier Dubois C. M., Storchi Lobos D., Lunniss R., Mora Mendoza A., and Ortiz Aguilú J. (2019). Prehispanic fishing structures preserved on the central coast of Ecuador. J. Maritime Archaeology 14, 107–126. doi: 10.1007/s11457-019-09239-w

Feng X., Park D. S., Walker C., Peterson A. T., Merow C., and Papes M. (2019). A checklist for maximizing reproducibility of ecological niche models. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1382–1395. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0972-5

Flores C. and Broitman B. R. (2021). Nearshore paleoceanographic conditions through the Holocene: Shell carbonate from archaeological sites of the Atacama desert coast. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecol. 562, 110090. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110090

Flores C., Figueroa V., and Salazar D. (2016). Middle Holocene production of mussel shell fishing artifacts on the coast of taltal (25°s), Atacama desert, Chile. J. Island Coast. Archaeology 11, 411–424. doi: 10.1080/15564894.2015.1105884

Fourcade Y., Engler J. O., Roder D., and Secondi J. (2014). Mapping species distributions with maxent using a geographically biased sample of presence data: A performance assessment of methods for correcting sampling bias. PloS One 9, e97122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097122

Fram J. P., Stewart H. L., Brzezinski M. A., Gaylord B., Reed D. C., Williams S. L., et al. (2008). Physical pathways and utilization of nitrate supply to the giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera. Limnology Oceanography 53, 1589–1603. doi: 10.4319/lo.2008.53.4.1589

GBIF.org (2024g). GBIF occurrence (Copenhagen, Denmark: GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility)). doi: 10.15468/DL.4GC7TQ

Godoy-Aguirre C., Frugone-Álvarez M., Flores C., Latorre C., Santoro C. M., and Gayo E. M. (2025). Cultural transformations were key to long-term resilience of hunter-gatherer societies in the coastal Atacama desert. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 369, 109580. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109580

Gómez I., Loaiza J., Palacios M., Osman D., and Huovinen P. (2025). Functionality of photobiological traits of the giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) as key determinant to thrive in contrasting habitats in a sub-antarctic region. Sci. Total Environ. 971, 179055. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.179055

González-Arangón D., Rivadeneira M. M., Lara C., Torres F. I., Vásquez J. A., and Broitman B. R. (2024). A species distribution model of the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera: Worldwide changes and a focus on the southeast pacific. Ecol. Evol. 14, e10901. doi: 10.1002/ece3.10901

Graham M. H., Kinlan B. P., Druehl L. D., Garske L. E., and Banks S. (2007a). Deep-water kelp refugia as potential hotspots of tropical marine diversity and productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 16576–16580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704778104

Graham M. H., Kinlan B. P., and Grosberg R. K. (2010). Post-glacial redistribution and shifts in productivity of giant kelp forests. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 277, 399–406. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1459

Graham M. H., Vásquez J. A., and Buschmann A. H. (2007b). “. Global ecology of the giant kelp Macrocystis: From ecotypes to ecosystems,” in Oceanography and marine biology: an annual review, vol. 45. (Washington, DC, USA: CRC Press), 39–88.

Grosjean M., Cartajena I., Geyh M. A., and Núñez L. (2003). From proxy data to paleoclimate interpretation: The mid-Holocene paradox of the Atacama desert, northern Chile. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecol. 194, 247–258. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00281-2

Hernández Castillo D. (2023). Humanos y fauna invertebrada: Tres modos de relacionamiento con la costa en punta teatinos (29°49’ lat. s), Chile. Boletín la Sociedad Chil. Arqueología, 135–171.

Hu Z.-M., Shan T.-F., Zhang Q.-S., Liu F.-L., Jueterbock A., Wang G., et al. (2024). Kelp breeding in China: Challenges and opportunities for solutions. Rev. Aquaculture 16, 855–871. doi: 10.1111/raq.12793

Hulton N. R., Purves R., McCulloch R., Sugden D. E., and Bentley M. J. (2002). The last glacial maximum and deglaciation in southern South America. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 21, 233–241. doi: 10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00103-2

Jayathilake D. R. M. and Costello M. J. (2021). Version 2 of the world map of laminarian kelp benefits from more arctic data and makes it the largest marine biome. Biol. Conserv. 257, 109099. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109099

Jones C. G., Lawton J. H., and Shachak M. (1994). Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 69, 373. doi: 10.2307/3545850

Juhl-Noodt H. (1958). Beiträge zur kenntnis der Peruanischen meeresalgen, i. Kieler Meeresforschungen 14, 167–174.

Kageyama M., Braconnot P., Harrison S. P., Haywood A. M., Jungclaus J. H., Otto-Bliesner B. L., et al. (2018). The pmip4 contribution to cmip6—part 1: Overview and over-arching analysis plan. Geoscientific Model. Dev. 11, 1033–1057. doi: 10.5194/gmd-11-1033-2018

Kennett J. P. and Ingram B. L. (1995). A 20,000-year record of ocean circulation and climate change from the santa barbara basin. Nature 377, 510–514. doi: 10.1038/377510a0

Kinlan B. P., Graham M. H., and Erlandson J. M. (2005). “Late-quaternary changes in the size and shape of the california channel islands: Implications for marine subsidies to terrestrial communities,” in Proceedings of the Sixth California Islands Symposium. 119–130 (Arcata, CA: Institute for Wildlife Studies).

Ladah L. B., Zertuche-González J. A., and Hernandez-Carmona G. (1999). Giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera, phaeophyceae) recruitment near its southern limit in baja california after mass disappearance during enso 1997–1998. J. Phycology 35, 1106–1112. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1999.3561106.x

Lambeck K., Rouby H., Purcell A., Sun Y., and Sambridge M. (2014). Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15296–15303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411762111

Latorre C., De Pol-Holz R., Carter C., and Santoro C. M. (2017). Using archaeological shell middens as a proxy for past local coastal upwelling in northern Chile. Quaternary Int. 427, 128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.01.074

Latorre C., Santoro C. M., Ugalde P. C., Gayo E. M., Osorio D., Salas-Egaña C., et al. (2013). Late pleistocene human occupation of the hyperarid core in the Atacama desert, northern Chile. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 77, 19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.06.008

Lawson C. R., Hodgson J. A., Wilson R. J., and Richards S. A. (2014). Prevalence, thresholds and the performance of presence–absence models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 54–64. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12123

Liu C., White M., and Newell G. (2013). Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J. Biogeography 40, 778–789. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12058

Lobo J. M., Jiménez-Valverde A., and Real R. (2008). Auc: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Global Ecol. Biogeography 17, 145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00358.x

Lopez P. M., Power X., González Venanzi L., Ibacache Doddis S., and Lorca Hurtado R. (2025). Diversity of birds and mammals uses on the Atacama desert coast, northern Chile (20°s): a case study of the middle Holocene. Quaternary Int. 742, 109911. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2025.109911

López Mendoza P., Cartajena I., Carabias D., Prevosti F. J., Maldonado A., and Flores-Aqueveque V. (2018). Reconstructing drowned terrestrial landscapes. isotopic paleoecology of a late pleistocene extinct faunal assemblage: Site gnl quintero 1 (gnlq1) (32 s, central Chile). Quaternary Int. 463, 153–160.

Martínez B., Radford B., Thomsen M. S., Connell S. D., Carreño F., Bradshaw C. J., et al. (2018). Distribution models predict large contractions of habitat-forming seaweeds in response to ocean warming. Diversity Distributions 24, 1350–1366.

Masuda S. (1986). Las algas en la etnografía andina de ayer y hoy. MASUDA, Shozo. Etnograf´ıa e historia del mundo andino. Continuidad y cambio (Tokio: Universidad de Tokio).

McCormac F. G., Hogg A. G., Blackwell P. G., Buck C. E., Higham T. F., and Reimer P.J. (2004). Shcal04 southern hemisphere calibration, 0–11.0 cal kyr bp. Radiocarbon 46, 1087–1092. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200033014

Mcfarland J. D., Ainis A. F., and Jazwa C. S. (2025). Multiscale analysis of zooarchaeological data to reconstruct past kelp forest productivity for the northern channel islands, california usa. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 316, 109178. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2025.109178

Melet A., Teatini P., Le Cozannet G., Jamet C., Conversi A., Benveniste J., et al. (2020). Earth observations for monitoring marine coastal hazards and their drivers. Surveys Geophysics 41, 1489–1534. doi: 10.1007/s10712-020-09594-5

Melo-Merino S. M., Reyes-Bonilla H., and Lira-Noriega A. (2020). Ecological niche models and species distribution models in marine environments: A literature review and spatial analysis of evidence. Ecol. Model. 415, 108837. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2019.108837

Meltzer D. J. (2021). First peoples in a new world: populating ice age america (Cambridge University Press).

Meltzer D. J., Grayson D. K., Ardila G., Barker A. W., Dincauze D. F., Haynes C. V., et al. (1997). On the pleistocene antiquity of monte verde, southern Chile. Am. Antiquity 62, 659–663. doi: 10.2307/281884

Méndez C., Gil A., Neme G., Delaunay A. N., Cortegoso V., Huidobro C., et al. (2015). Mid holocene radiocarbon ages in the subtropical andes (29–35 s), climatic change and implications for human space organization. Quaternary Int. 356, 15–26.

Merow C., Smith M. J., and Silander J. A Jr. (2013). A practical guide to maxent for modeling species’ distributions: what it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography 36, 1058–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.07872.x

Mohtadi M., Romero O. E., and Hebbeln D. (2004). Changing marine productivity off northern Chile during the past 19–000 years: a multivariable approach. J. Quaternary Sci. 19, 347–360. doi: 10.1002/jqs.832

Montt I., Fiore D., Santoro C. M., and Arriaza B. (2021). Relational bodies: affordances, substances and embodiment in chinchorro funerary practices c. 7000–3250 bp. Antiquity 95, 1405–1425.

Moragas C. (1982). Túmulos funerarios en la costa sur de tocopilla (cobija) - ii región. Chungara Rev. Antropología Chil. 9, 152–173.

Moragas C. and Mendez-Quiros P. (2022). La secuencia cronológica de punta patache y la ocupación de la costa arreica del desierto de Atacama (21°s). Estudios atacameños 68. doi: 10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2022-0029

Mork M. (1996). The effect of kelp in wave damping. Sarsia 80, 323–327. doi: 10.1080/00364827.1996.10413607

Muñoz I. (2014). Ritualidad y memoria de los pescadores de la costa de arica durante el período arcaico tardío: El caso de la cueva de la capilla (Arica, Chile: Mil años de historia de los constructores de túmulos de los valles desérticos de Arica: Paisaje, monumentos y memoria), 39–64.

Narayan N., Paul A., Mulitza S., and Schulz M. (2010). Trends in coastal upwelling intensity during the late 20th century. Ocean Sci. 6, 815–823. doi: 10.5194/os-6-815-2010

Núñez L. (1976). Registro regional de fechas radiocarbónicas del norte de Chile. Estudios Atacameños. Arqueología y antropología surandinas, 69–111.

Núñez L., Zlatar V., and Núñez P. (1974). Caleta huelén-42: una aldea temprana en el norte de Chile (nota preliminar). Hombre y Cultura 2, 67–103.