- 1Research Institute on Terrestrial Ecosystems (IRET), National Research Council of Italy (CNR), Terni, Italy

- 2NBFC, National Biodiversity Future Center, Palermo, Italy

A Commentary on:

Biological recycling theory: a cyclic network framework for evolutionary innovation and recovery

By Mesallum S (2025) Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1641717. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1641717

1 Introduction

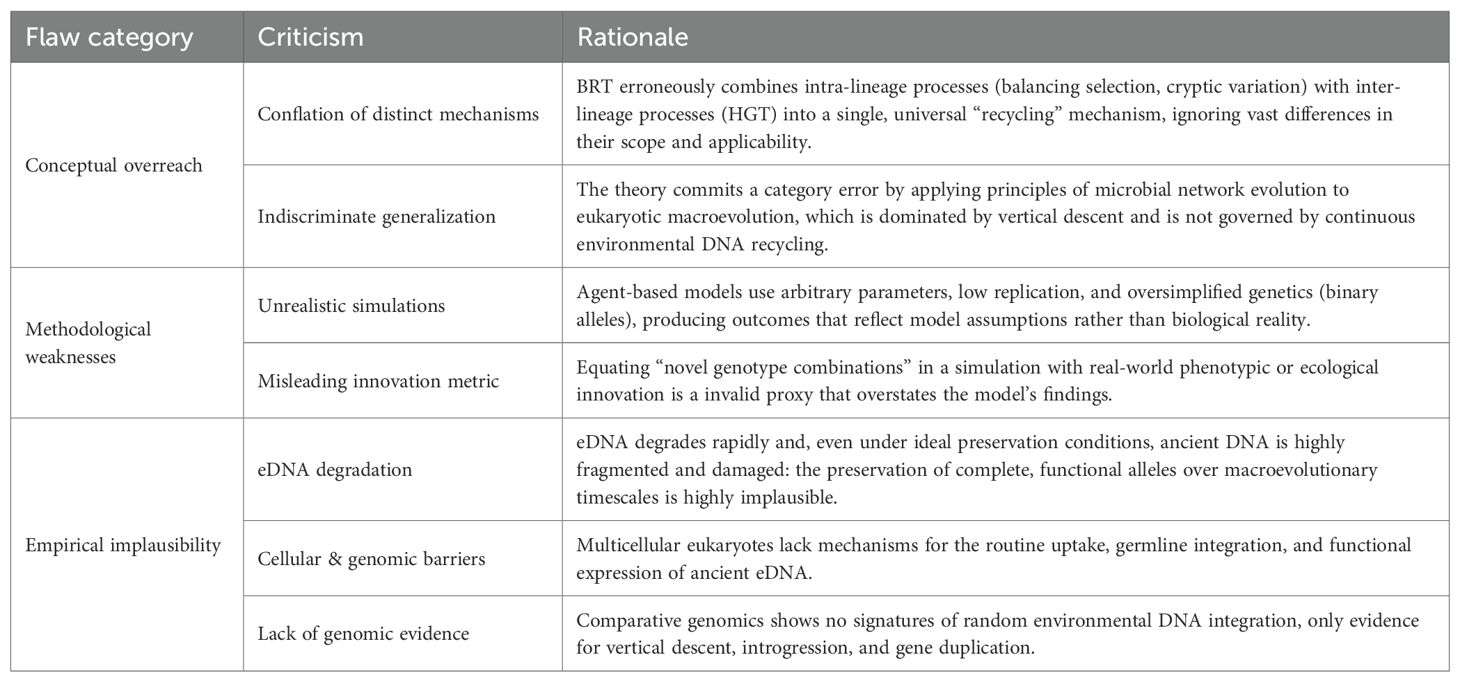

Macroevolutionary patterns such as biodiversity recovery after mass extinctions and evolutionary radiations driven by biological novelties are central questions in evolutionary biology (Erwin, 2008; Benton, 2010). Mechanisms such as mutation, selection, recombination, and hybridization provide well-established explanations for genetic and phenotypic innovation. Recently, Mesallum (2025) introduced the Biological Recycling Theory (BRT), proposing that evolution operates through a “cyclic network” rather than a purely tree-like process of descent with modification. In this view, alleles lost from extinct populations/species may persist in environmental DNA (eDNA) reservoirs and be later reintroduced into genomes through processes such as horizontal gene transfer (HGT), and recombination. While conceptually intriguing, BRT conflates processes of different nature and scope, extending microbial mechanisms to all life without a solid empirical foundation. This commentary evaluates BRT’s conceptual soundness, highlighting its major flaws (Table 1) and suggesting directions for future research.

Table 1. Summary of major conceptual, methodological, and empirical flaws in the Biological Recycling Theory (BRT).

2 Conceptual overreach and theoretical inconsistencies of BRT

BRT combines established processes like balancing selection, cryptic variation, and HGT into a single, problematic “recycling” mechanism.

Balancing selection maintains polymorphisms within lineages (Charlesworth, 2006), not across extinction boundaries, and cryptic genetic variation is an intragenomic reservoir, not a transgenerational recycling system (Paaby and Rockman, 2014). In contrast, HGT is a recognized evolutionary force in prokaryotes and some protists (Lorenz and Wackernagel, 1994). While HGT’s occurrence in multicellular eukaryotes is acknowledged, it remains a more limited phenomenon (Soucy et al., 2015; see point 4). Crucially, there is no compelling evidence for functional HGT from ancient eDNA into complex multicellular eukaryotes. The unifying metaphor of “alleles circulating through time and space” thus collapses mechanisms that differ profoundly in frequency and scope.

3 Methodological limitations of the simulation model

The agent-based simulations used to support BRT are elegant but biologically unrealistic. Mesallum (2025) simulated scenarios where the “full BRT” model produced faster recovery after extinctions. However, methodological concerns undermine these conclusions: (a) arbitrary parameters: probabilities for DNA uptake and mutation rates are not empirically grounded; (b) low replication: only three replicates per scenario were run, limiting statistical confidence; (c) simplistic genotype definition: binary alleles and additive fitness fail to capture genetic complexity like epistasis and pleiotropy; (d) misleading innovation proxy: counting unique genotype combinations does not equate to phenotypic innovation (Wagner, 2011). The outcomes reported by the author thus reflect model assumptions rather than emergent properties of real evolution.

4 Empirical implausibility of environmental DNA recycling

The core BRT premise, i.e. that eDNA acts as a long-term reservoir of functional alleles, conflicts with empirical evidence.

DNA persistence: DNA degrades rapidly due to chemical and enzymatic processes. Its persistence in the environment can range from days/years for extracellular eDNA in water (Harrison et al., 2019) up to ~2–2 Myr in exceptional cold, stable, clay-rich sediments (Kjær et al., 2022). However, even under ideal conditions, ancient DNA is highly fragmented and damaged (Willerslev and Cooper, 2005), rendering the preservation of complete, functional alleles over geological timescales highly implausible. Furthermore, even if well preserved, a released ancient allele would degrade rapidly, making its uptake and functional integration into a living organism infinitesimally rare (except perhaps for microorganisms under particular conditions).

Cellular and genomic barriers: for heritable change, an ancient allele must be taken up by germline cells and integrated into the genome without deleterious effects. While bacteria can freely exchange genetic material with their environment, multicellular eukaryotes show no evidence of routinely integrating environmental eDNA into their genomes. Although it is true that documented cases of HGT in plants and animals are increasingly common, they are not ubiquitous but rather context-specific. Most importantly, they typically involve direct cellular contact (e.g., in parasitism or symbiosis) or vectors like viruses (Keeling and Palmer, 2008; Mariault et al., 2025), not the scavenging of free, ancient eDNA proposed by BRT. Critically, even if integration occurred, an allele from a distantly related extinct organism (e.g., a dinosaur) would be functionally incompatible with the gene regulatory network of a living species (e.g., a modern mammal).

Genomic signatures: evidence from comparative genomics reveal clear signatures of vertical descent, introgression, and duplication, but no evidence for the systematic genomic integration of exogenous eDNA sequences in eukaryotic organisms.

5 The problem of scale and generalization

Cyclic genetic exchange is already a recognized model for microbial evolution, where HGT is rampant (Doolittle and Bapteste, 2007). However, this does not extend to eukaryotic evolution, which is largely vertical and shaped by mutation, recombination and hybridization. By proposing a universal framework that conflates microbial gene flow with eukaryotic macroevolution, BRT commits a category error. Evolutionary mechanisms must be interpreted within their cellular, phylogenetic and ecological contexts.

6 Framing and epistemic caution

The rhetorical framing of BRT as a replacement for the “tree of life” can lead to a misrepresentation of evolutionary theory. Tree-like descent remains a robust model, even when augmented by networks for specific cases. Moreover, relying on the “recycling” analogy without empirical evidence may inadvertently promote an “eternal return” view of evolution, which is not only problematic under the perspective of biodiversity conservation, but also risks acquiring theological overtones, confusing to the public’s understanding of how nature’s laws operate.

7 Perspectives and future directions

Despite its flaws, BRT highlights a genuine research frontier: the role of non-vertical genetic processes in macroevolution. Future research should focus on empirically testable questions: (1) What are the actual rates and adaptive impact of HGT across major lineages?; (2) Can genomic data distinguish ancient HGT events from introgression or duplication? (3) How can evolutionary models incorporate reticulate processes and HGT without sacrificing realism?

8 Conclusions

The biological recycling theory is a stimulating but scientifically fragile proposal. It fuses credible processes into an implausible evolutionary framework that lacks empirical grounding. Rather than offering a paradigm shift, BRT could serve as a reminder that theoretical synthesis must remain constrained by mechanistic plausibility. Conceptual creativity is welcome, but without empirical anchors, it produces elegant metaphors detached from reality. The future of evolutionary theory lies in integrating genomic evidence, palaeontological data, and the biotic and abiotic drivers of evolution within realistic modelling frameworks, grounding evolutionary inference in both known biological processes and the deep-time patterns documented in the fossil record.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Benton M. J. (2010). The origin of modern biodiversity on land. Phil. Trans. R. Soc B. 365, 3667–3679. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0269

Charlesworth D. (2006). Balancing selection and its effects on sequences in nearby genome regions. PloS Genet. 2, e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020064

Doolittle W. F. and Bapteste E. (2007). Pattern pluralism and the Tree of Life hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2043–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061069910

Erwin D. H. (2008). Extinction as the loss of evolutionary history. PNAS 105, 11520–11527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801913105

Harrison J. B., Sunday J. M., and Rogers S. M. (2019). Predicting the fate of eDNA in the environment and implications for studying biodiversity. Proc. R. Soc B. 286, 20191409. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1409

Keeling P. J. and Palmer J. D. (2008). Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 605–618. doi: 10.1038/nrg2386

Kjær K. H., Pedersen M. W., De Sanctis B., De Cahsan B., Korneliussen T. S., Michelsen C. S., et al. (2022). A 2-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland uncovered by environmental DNA. Nature 612, 283–291. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05453-y

Lorenz M. G. and Wackernagel W. (1994). Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiol. Rev. 58, 563–602. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.563-602.1994

Mariault L., Puginier C., Keller J., El Baidouri M., and Delaux P. M. (2025). Mechanisms, detection, and impact of horizontal gene transfer in plant functional evolution. Plant Cell. 37, koaf195. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koaf195

Mesallum S. (2025). Biological recycling theory: a cyclic network framework for evolutionary innovation and recovery. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1641717

Paaby A. B. and Rockman M. V. (2014). Cryptic genetic variation: evolution’s hidden substrate. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 247–258. doi: 10.1038/nrg3688

Soucy S. M., Huang J., and Gogarten J. P. (2015). Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 472–482. doi: 10.1038/nrg3962

Wagner A. (2011). The origins of evolutionary innovations: a theory of transformative change in living systems (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199692590.001.0001

Keywords: biodiversity resilience, biological recycling theory, environmental DNA (eDNA), evolutionary radiations, horizontal gene transfer (HGT), macroevolution, post-extinction recovery

Citation: Marchesini A (2025) Commentary: Biological recycling theory: a cyclic network framework for evolutionary innovation and recovery. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1743158. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1743158

Received: 10 November 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Revised: 01 December 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

John Maxwell Halley, University of Ioannina, GreeceReviewed by:

Diogo Mayrinck, Rio de Janeiro State University, BrazilCopyright © 2025 Marchesini. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexis Marchesini, YWxleGlzLm1hcmNoZXNpbmlAY25yLml0

Alexis Marchesini

Alexis Marchesini