- School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Resistance to xenobiotic compounds—including insecticides, herbicides, antibiotics, fungicides, and chemotherapies — is a pervasive and intensifying problem across agriculture, medicine, and public health. Billions are invested each year into creating new compounds to combat pests, pathogens, and cancer cells, yet resistance evolves swiftly and repeatedly. This recurring failure stems not from a lack of innovation but from a lack of integration. Current strategies are predominantly developed within disciplinary and taxonomic silos, and often ignore the evolutionary nature of resistance. This topic is extremely relevant and contemporary as the emergence of resistance is an evolutionary inevitability whenever a population is exposed to strong selection pressures such as xenobiotic compounds. Despite this, resistance management remains reactive and compound-specific, relying on successive chemical innovations rather than long-term strategies. In this piece, the authors argue that resistance is not a domain-specific phenomenon, but a general evolutionary process. Drawing together research across insects, bacteria, fungi, plants, and cancer biology, this Perspective outlines how comparative insights and integrative strategies can reshape the way we approach resistance in both agricultural and biomedical systems. To confront this pressing and pervasive issue — where evolution outpaces our interventions — we must adopt an integrative evolutionary perspective that is anticipatory, not reactive. Resistance to xenobiotics is a shared evolutionary outcome across life forms, and so too should be our approach to solving it. This Perspective will serve as a conceptual bridge for researchers across domains, encouraging coordinated, evolutionary-informed solutions to one of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Introduction

Organismal resistance to anthropocentric, xenobiotic interventions, such as insecticides and antibiotics, is of pressing health and financial global concern that requires rapid and sustainable solutions. Billions of dollars are spent every year on existing chemicals, or to find new alternatives to eradicate organisms that negatively impact our health and well-being, including plants, insects, bacterial and fungal parasites, viruses and coronaviruses, and even cancer cells. Yet all these organisms have evolved mechanisms to thwart the drugs, chemicals and transgenic interventions designed to eliminate them (Ahmad and Khan, 2019; Grochtdreis et al., 2018; Pimentel, 2010; Alyokhin et al., 2025). This response is predicted by evolutionary theory: changes in the environment, including the introduction of xenobiotics, will create a selection pressure favouring the evolution of counter-adaptations in the species we wish to eliminate. New interventions are unlikely to be more successful but rather encourage an ongoing escalation of interventions and counter-adaptations, with no net gain for either antagonist, a process dubbed the Red Queen Hypothesis by Van Valen, 1977. Despite decades of research investigating the mechanisms of organismal resistance, this thorny issue persists because the interventions, developed by isolated fields of research, fail to eliminate the entire population or species. It is timely to recognise that this approach is not sustainable, and raises the question: should the research community take a step back and analyse the problem from a broader perspective to develop different approaches? Here we outline some advances in disparate fields of xenobiotic resistance, as well as identify some taxonomic silos, and suggest potential strategies to combat this pervasive issue of resistance.

The active and continuous emergence of resistance to xenobiotic compounds reflect the rich history of the evolution of life (Wedell and Hosken, 2017). More than three billion years of natural selection has driven the evolution of extraordinary adaptations that ensure the persistence of populations in diverse environments. Whilst we have tinkered with evolutionary processes, including the remarkable success of plant and animal domestication, we have barely scratched the surface of the potential nature has to solve anthropocentric problems (Ng et al., 2021). For example, gene editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, which were developed a decade ago, leverage an immune response mechanism in bacteria that has existed for billions of years (Jinek et al., 2012). Similarly, the potential of utilising the innate metabolism of bacteria to breakdown pollutants or harvest rare metals from mine waste was only discovered in the last two decades (Bryan et al., 2006). And whilst we have been using insecticides to fight pests in agriculture since the 1940s, most insecticides are still based on compounds naturally produced by plants (e.g. caffeine and nicotine), which have evolved for millions of years to prevent the attack of insects (Matthews, 2018).

Nonetheless, our approach to resolving the challenges of resistance too often ignores underlying evolutionary processes, judging each situation as insular and resolved with a single cellular compound to target. Our history is of sledge-hammer solutions in the form of developing and applying new, “last resort” synthetic poisons. Yet one thing is certain: new methods of controlling unwanted organisms will generate strong selective pressures favouring effective counter measures – adaptations that rapidly evolve in the target population and allow these unwanted organisms to persist. In this context, it is unsurprising that resistance has evolved against almost all insecticides (Bass et al., 2015), and that antibiotic resistance is a globally pervasive challenge in our health and agricultural systems (Selvarajan et al., 2022). Many studies have, in fact, shown that an increased use of antibiotics is directly linked with an increase in antibiotic resistance prevalence in medical wards (Goossens et al., 2005; Willemsen et al., 2009). Clearly, we require a smarter, more nuanced approach.

An evolutionary process requires an evolutionary perspective

Perhaps the first step is to recognise that emerging resistance is an evolutionary process, which requires an appreciation of how resistance to xenobiotic compounds arises and recognising that resistance to xenobiotic compounds does not necessarily carry a cost.

It is widely believed that resistance to human-made compounds arises from de novo mutations (Bass, 2017). This is a misconception – in most cases, the evolution of resistance involves the recruitment or repurposing and/or enhancement of existing genetic detoxification machinery (Bass, 2017). As such, most adaptations to detoxify xenobiotic compounds are not necessarily associated with costs, even though the notion of costly resistance is pervasive across the scientific fields. For example, the cytochrome P450 gene Cypg6g1 in Drosophila melanogaster was originally involved in the hydroxylation and detoxification of metabolic compounds (Daborn et al., 2002). Less than a century ago, Cyp6g1 was recruited to metabolise insecticides such as DDT and imidacloprid (Ffrench-Constant, 2013). The Cyp6g1 ‘resistance’ allele existed prior to the application of insecticides (Harrop et al., 2014) and became a key element in driving the evolution of insecticide resistance. This pattern is not isolated: the same molecular machinery is utilised in the related species D. simulans, where the orthologue of Cyp6g1 also confer resistance to insecticides by increased expression (Schlenke and Begun, 2004). The history of resistance adaptations to anthropocentric compounds is replete with similar cases. Wild populations of the Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina, have high frequencies of resistance to malathion, an insecticide used briefly in the 1950s. Resistance to malathion predates the use of this insecticide, and is most likely associated with standing genetic variation that already existed in wild populations. Human activity is responsible for the increase in frequency of these existing rare variants within natural populations (Ffrench-Constant, 2007).

It is frequently assumed that resistance mechanisms are costly, and that natural selection will eliminate them in the absence of exposure to xenobiotic compounds. However, these genetic detoxification mechanisms that allow insects to manage naturally occurring toxins in their environment have been shaped by billions of years of evolution resulting in minimised or optimised fitness costs (Wedell and Hosken, 2017). Hence, we should not assume that these detoxification mechanisms inherently are costly. To understand this misconception, we must look at cases across taxa and understand the commonalities between them.

Taxonomic silos

Antibiotic resistance is perhaps more widely recognised in the public domain due to its dramatic impacts on human lives (Dadgostar, 2019). However, resistance to xenobiotic compounds has evolved across all taxonomic groups: insecticide resistance among insects; plant resistance to herbicides, and resistance to fungicides by fungi, are globally pervasive and each is of concern (Bass et al., 2015; Lucas et al., 2015; Owen and Zelaya, 2005). The United Nations has recently highlighted the urgency of examining these phenomena with sustainability in mind and an emphasis on research cooperation amongst countries and institutes (Figueras, 2024). Resistance across these diverse taxa directly impacts human health and wellbeing, yet we found there is remarkably uneven research activity across these taxonomic boundaries and, unfortunately, very little evidence of engagement between them.

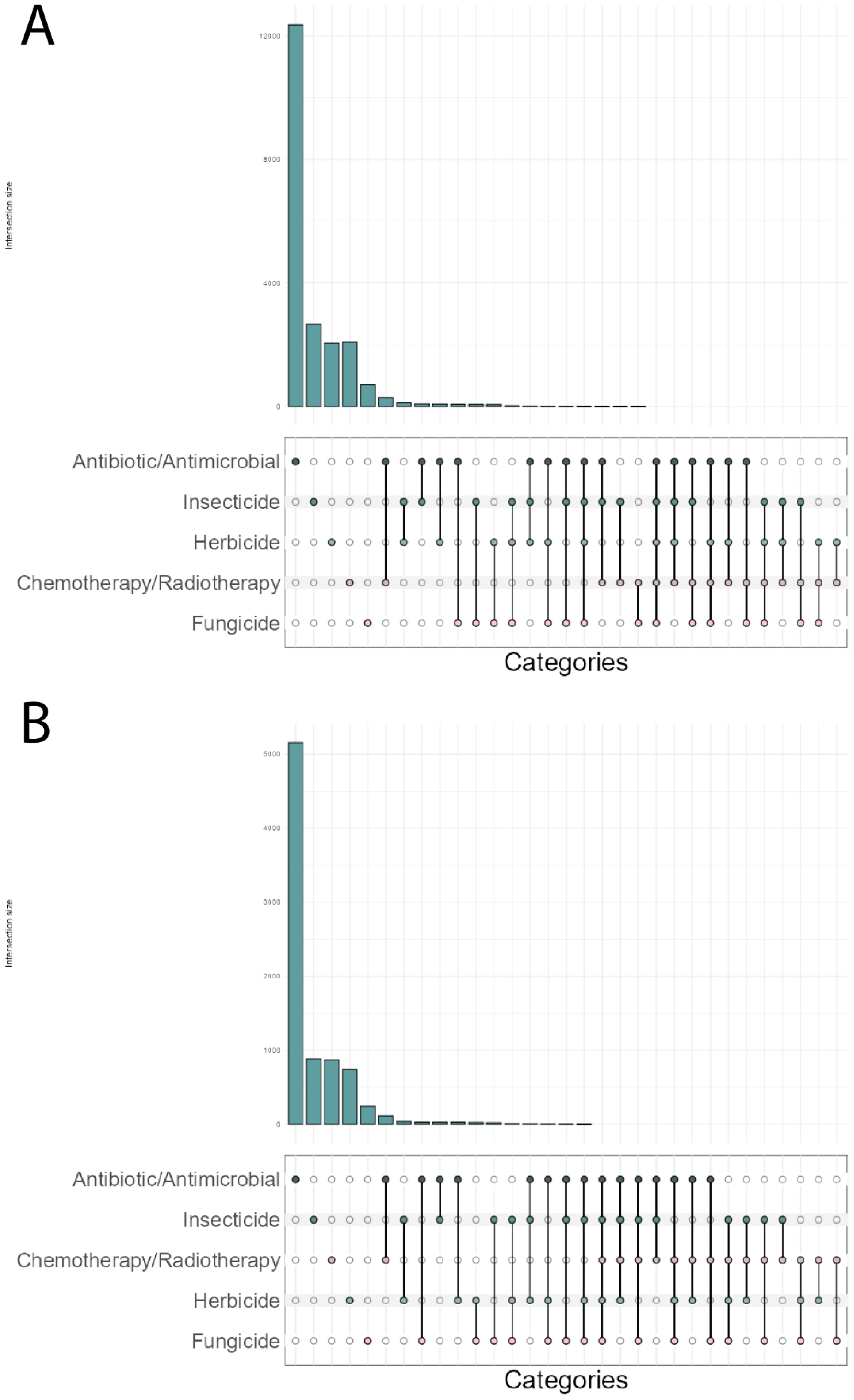

We quantified the number of scientific articles that examined the evolution of resistance by pairing the terms “evolution” and “natural selection” with the different types of compound resistance and searching through the Web of Science’s repository for scientific articles that mention these terms [20/07/2024]. Over 11,000 articles were identified with antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance, which is close to five times more frequent than that identified for insecticide, herbicide or chemotherapy/radiotherapy resistance (Figure 1A). The least studied, with five times fewer articles mentioning these terms, was fungicide resistance (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Number of scientific articles exploring the evolution of resistance to human-made compounds across all time (A) or within the last 5 years (B). A search containing the terms “evolution”, “natural selection” and either of the resistances shown was performed to count the number of scientific articles in the Web of Science repository that fit these criteria. The dots in the x axis show which terms were searched, connecting lines symbolize multiple terms searched concurrently. The y axis shows the number of articles that contain the terms searched.

A simple way to assess the degree of engagement of research across these different taxonomic groups is to count the number of articles that mention more than one type of resistance. We investigated this possibility by pairing different terms of resistance and searching through the same repository for scientific articles. Less than 4% of the 19,165 articles mention the evolution of resistance in multiple taxa/systems (Figure 1A), and chemotherapy/radiotherapy resistance research is reported the least in conjunction with any other type of resistance beyond antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. Although this search does not take into account terms mentioned in sections of an article such as discussion, this search provides a broader and more conservative snapshot of a pattern consistent with earlier observations that research into organismal resistance is segregated into two major groups (REX Consortium, 2007), comprising the medical and the agricultural (and related) sciences. The chasm between the fields is remarkable, given the pervasive commonality of resistance to xenobiotics across taxa.

Furthermore, the separation of research on resistance into taxonomic silos is both historical and contemporary. Confining this literature to the last 5 years, reveals remarkably similar patterns. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance is still the most reported resistance, followed by insecticide, herbicide, and chemotherapy/radiotherapy resistance. Fungicide resistance remains as the least reported resistance across the fields (Figure 1B). Most strikingly, the lack of engagement between fields remains unchanged, with less than 4% of articles mentioning the evolution of resistance in multiple taxa/systems (Figure 1B).

This pattern may arise because research on resistance places a strong focus on resolving proximate questions: how to rapidly eliminate resistant individuals, and which molecule(s) should be produced next to target the resistance mechanism? While resolving these questions may provide short-term solutions, they are not sustainable in the long term because resistance to anthropomorphic compounds is not a short-term or transient problem. Natural selection cannot be eliminated except by extinguishing the population or species. Nevertheless, it is rarely acknowledged that across taxa, the resistance mechanisms we observe arise from the evolutionary recruitment of an existing molecular machinery that often have low fitness costs (Ffrench-Constant and Bass, 2017). The lack of sustainable success in controlling unwanted organisms means we require a different approach that incorporates evolutionary knowledge and insights from across the traditional taxonomic boundaries.

Universal approaches for global problems

The evolutionary problem of resistance has been investigated for many decades (Futuyma, 1995; Mayr, 1961; Palumbi, 2001), and it is acknowledged that research in both the medical and agricultural (and related) fields would benefit from identifying the selective pressures created by xenobiotics, thereby determining the mechanistic and evolutionary strategies that will minimise the impact and rise of xenobiotic resistance. There is an increasing need for adoption of a holistic approach to control insects and weeds, which aims to incorporate genetic tools and evolutionary theory to develop strategies that mitigate resistance emergence and its costs to society.

An early attempt at a holistic approach was made in the 1990s through the use of Transgenic Insecticidal Cultivars (TICs). TICs are crops that are genetically modified to incorporate genes from other organisms that code for compounds that are toxic to pests (Carozzi and Koziel, 1997). The use of TICs aims to incorporate chemical strategies by harnessing naturally produced insecticide- or herbicide-chemicals with biological approaches. However, TICs require heavy regulation worldwide, and like many other strategies, it only works in a short timeframe due to adaptation by the pests to these chemical compounds, which ultimately leads to an increase in resistance (Gould, 1998).

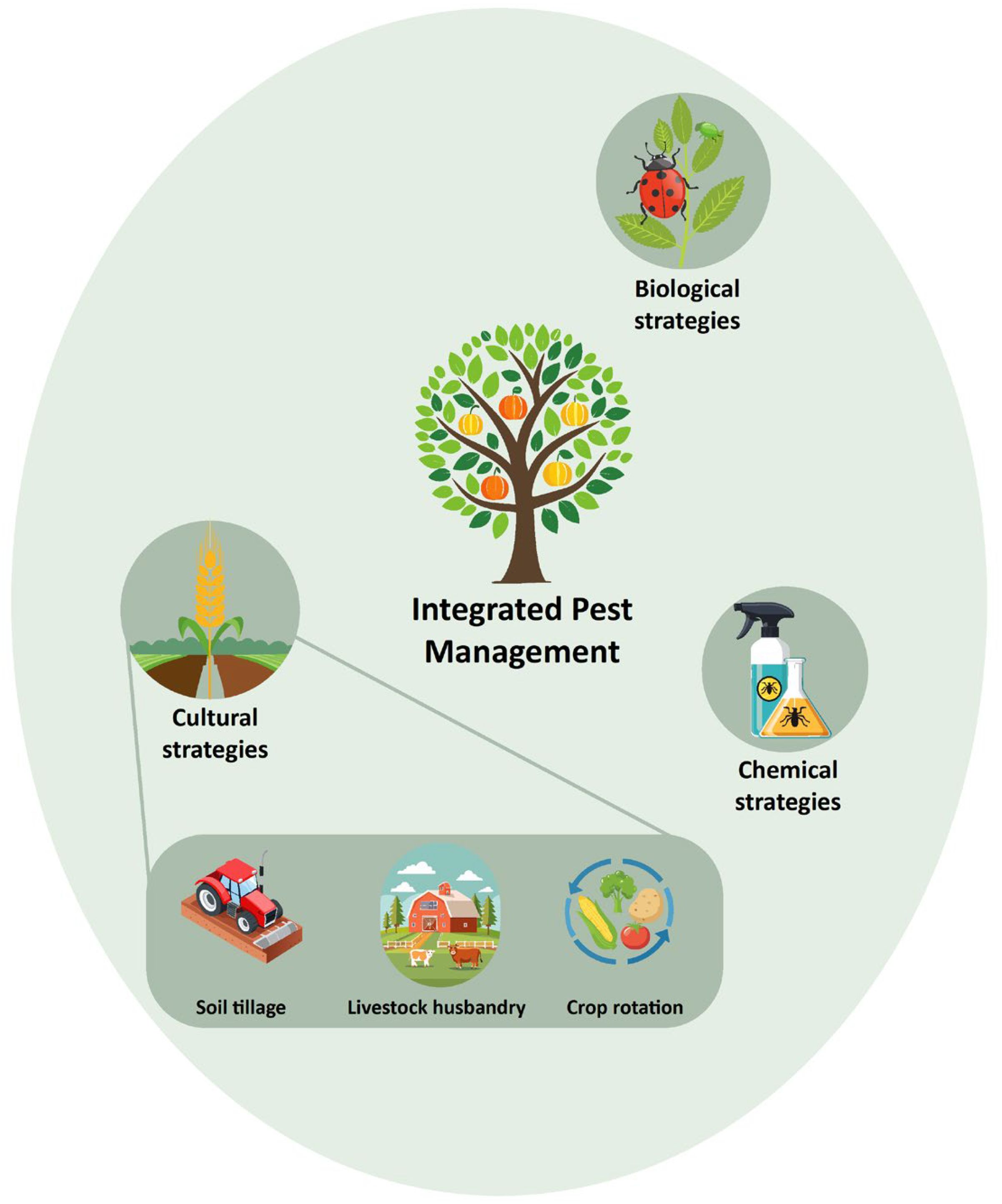

The Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach is, however, a combination of chemical, biological, and cultural strategies to prevent significant economic loss and reduce the frequency of xenobiotic resistance (Figure 2, Barzman et al., 2015). While chemical strategies are most common, integrating cultural changes at the agricultural level may achieve better outcomes in the longer term (Figure 2). Biological strategies can add further value by using natural predators such as mites and parasitic wasps to reduce pest populations, or by harnessing gene drives capable of reducing populations of resistant conspecific insects (Barzman et al., 2015). Gene drive is a phenomenon where a particular heritable element enjoys a biased transmission, resulting in a higher prevalence in the population across generations (Alphey et al., 2020). This mechanism was first observed in nature in the form of active transposable elements in Zea maize (Hoffmann et al., 2017). Naturally occurring segregation distorters can be harnessed and used to drive detrimental genes or constructing entirely synthetic gene drives to manage and suppress pest or vector populations (Wedell et al., 2019). Wolbachia has been used as an endosymbiont capable of reducing mosquito populations, whilst also reducing these insects’ vector competence to dengue (Dorigatti et al., 2018). The combination of these approaches will allow for a drastic reduction in the use of xenobiotic compounds to eliminate these organisms and hence eliminating strong selection for emerging resistance.

Figure 2. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) as a holistic approach to xenobiotic resistance. Beckie et al., 2021 showed through bioeconomic modelling that with the reduction in available herbicides, strategies like soil tillage or livestock husbandry may become key to prevent weeds from ruining crops while simultaneously reducing the frequency of herbicide resistance. While chemical strategies are the most used, integrated cultural changes at the agricultural level may achieve better outcomes. Such changes might include better crop hygiene, crop rotation, livestock husbandry, soil tillage, and many other interventions (Beckie et al., 2021).

Although highly effective and beneficial, IPM strategies are yet to be widely adopted. One inherent barrier to the wider take up of this strategy is its complexity and knowledge-heavy nature, which requires an investment in education, and experimentation by farmers (Deguine et al., 2021). But other barriers such as economic, cultural, or social also need to be addressed to ensure this strategy can be more efficiently adopted in agriculture (Zhou et al., 2024).

While IPM has been seen as an efficient approach in the agricultural sciences, an analogous strategy is yet to be developed in the context of population health. The closest strategy to date is One Health, an integrated, unifying approach that aims to optimize the health of humans, animals, plants, and ecosystems and recognises that these are closely linked and interdependent (FAO et al., 2022). This strategy integrates multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at various levels in society to promote collaboration and to tackle threats to health and ecosystems whilst addressing the collective need for clean resources, taking action on climate change, and contributing to sustainable development (FAO et al., 2022). However, there is still a lack of evolutionary theory integration into these plans. Ultimately, this omission will lead to a resurgence of xenobiotic resistance, incurring millions of dollars in costs and losses, as well as negatively impacting ecosystems around the world.

Bacteriophage therapy to combat antibiotic resistance is an example of an emerging strategy to reduce antibiotic resistance (Gordillo Altamirano and Barr, 2019). Bacteriophage (or just phage) therapy has been revived recently and involves bacteriophages that are absorbed by a specific host-bacterium and that can be targeted with great precision, resulting in lysis and death of the antibiotic-resistant bacterium (Gordillo Altamirano and Barr, 2019). However, continually implementing this strategy will simply favour phage-resistance bacteria as readily as antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Nevertheless, a holistic approach that uses a combination of antibiotics, phages, and other strategies may act to control the rate of evolution of “super resistant” bacteria.

Prophylactic treatments have a higher chance of success at eradicating the targeted organism and reducing insurgence of resistance compared with therapeutic treatments (Kennedy and Read, 2017). Vaccine development and antiretroviral treatments are exemplary cases. The wide use of vaccines for many decades against various microorganisms, imposes strong selection for resistance to emerge. However, vaccine resistance is rarely observed (Kennedy and Read, 2017, 2018). This is due to the prophylactic nature of vaccines combined with the fact that vaccines tend to induce immune responses against multiple targets on a single pathogen, increasing the difficulty to evolve resistance (Kennedy and Read, 2017). Prophylactic measures ensure the immune system retains memory of the measures against pathogens, which increases efficiency for future incursions. Prophylactic measures also induce population bottlenecks, prior the use of xenobiotics, which drastically reduce genetic diversity, and hinders the capacity microorganisms have to develop resistance to the xenobiotics in question (Alyokhin et al., 2025). Antibiotics in contrast, do not create this memory response, and act post-invasion when genetic diversity is higher, and resistant individuals can be selected for (Alyokhin et al., 2025). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is another successful approach that has been implemented globally for more than a decade without a rise in resistance (Gibas et al., 2019). This antiretroviral strategy, similar to vaccines, relies on its prophylactic nature and induction of the immune response to eradicate the virus, creating population bottlenecks, which reduces genetic diversity and hence the scope for resistance to be selected for (Gibas et al., 2019).

Other more novel, but not as effective, strategies are the use of anti-antibiotics, which are compounds that inactivate intravenous antibiotics that reach the gastrointestinal tract in humans (LaJeunesse, 2020). The precise deployment prevents resistance in off-target bacteria while maintaining the effectiveness of antibiotics in the rest of the body (Morley et al., 2019). Pairing strategies such as the use of anti-antibiotics with the use of bacteriophages, when prophylactic strategies such as vaccines are not available, may potentially reduce the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as these compounds will reduce the selective pressure stemming from antibiotic usage. Furthermore, these strategies can be informed by components of evolutionary concepts, including kin selection theory. Bacteria can adjust their virulence based on their social and abiotic environment (Kümmerli, 2015). Social interactions between bacteria are also important in antibiotic-resistant scenarios, since resistance to xenobiotics can change dramatically depending on the bacterial community structure (Denk-Lobnig and Wood, 2023, 2025). In some contexts, resistance can rapidly evolve through the community when endogenous bacteria protect the pathogenic bacteria by metabolising antibiotics before they reach the pathogenic strains. And social interactions can, inversely, reduce the prevalence of resistant strains if the microbial communities exhibit mutualistic cross-feeding interactions. In these cases, the most antibiotic susceptible strain will determine the antibiotic susceptibility for the whole community, since without this strain the whole community collapses. Pearl Mizrahi et al. (2023) also showed that strains of susceptible bacteria can evolve tolerance to antibiotic compounds if they cohabit with resistant strains of the same bacterial species. Applying these evolutionary insights may allow us to predict the emergence of antibiotic resistance and may prove helpful in understanding the population dynamics of xenobiotic resistance.

Research into cancer is an exemplary case of how pairing chemical with evolutionary approaches create a more effective strategy against xenobiotic resistance. Many types of cancer cells develop resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy (Hickman, 1996), and an evolutionary perspective, together with the use of holistic strategies, has had some success in controlling emerging resistance. Evolutionary theory predicting how natural populations evolve can provide insight into how to avoid the emergence of chemo/radiotherapy resistance in cancer populations (Natterson-Horowitz et al., 2023). Strategies such as adaptive and extinction therapies are currently being used in test trials with great success for some cancers (Zhang et al., 2017). These therapies rely on extinction biology principles that state that reducing population size (in this case, cancer cells), while the population is still susceptible to the stressor (in this case chemo- or radiotherapy) and introducing a new ecological perturbation (here, a new drug), is often associated with the extinction of the cancer (Gatenby and Brown, 2020; Walther et al., 2015). This approach has been driven by the fact that a cancer is a genetically diverse population, with a highly sensitive environment (the human host). Strong stressors might cause too much harm to the environment where the cancer resides, and genetic tools, such as xenobiotic compounds, are most effective when targeting specific cell receptors common across the whole population, and therefore, are not as effective in a genetically diverse population.

Although a holistic approach is an improved direction for future resistance research, it may not necessarily provide a panacea. From an evolutionary perspective, IPM strategies to combat insecticide resistance involve prevention of the invasion of resistant insects, and/or reduction of the selective pressure. This can be achieved by reducing pesticide usage and creating opportunities to increase the proportion of susceptible individuals into the population, typically by creating adjacent, insecticide-free crops (Barzman et al., 2015). While a similar strategy has been suggested in a hospital context (Cole et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2014), it is unlikely to garner much traction: hospital administrators would be reluctant to encourage free movement of patients infected by bacteria with variable levels of antibiotic resistance across different wards to reduce levels of antibiotic resistance across the hospital. Hence the usage of prophylactic measures, such as vaccines and PrEP-like compounds, might become the best strategy to combat resistant organisms. And just as the number of effective antibiotics is decreasing, the number of effective pesticides is also shrinking: this number reduced in Europe by 64% between 1999 and 2009 (Moss, 2010). With fewer xenobiotic compounds available, new and different strategies are required to combat resistance, notably because the overuse of available human-made compounds will lead to a further increase in resistance. A correlation between xenobiotic compound usage and an increase in insecticide resistance is common across insect taxa, suggesting a causal relationship (Bass et al., 2015; Bell et al., 2014; Chantziaras et al., 2014; Reid et al., 2016). This pattern is also true of antibiotic resistance, and thus, emphasises the commonality of processes (Ventola, 2015). This emergence in resistance across taxa underscores why a holistic approach is vital for a multi-levelled issue, for both human-focused and crop-focused scenarios.

The consistent and taxonomically widespread increase in the frequency of emerging resistance to xenobiotic compounds indicates that persisting with current strategies is simply not sustainable. Changes in the environment, such as the introduction of xenobiotic interventions, will inevitably create a selection pressure favouring the evolution of counter-adaptations in the populations we wish to eliminate. As Raymond (2019) puts it: “some humility in the face of natural selection can ensure that human creativity keeps pace with evolutionary innovation”. This collective creativity will benefit not only from an evolutionary perspective, but also from collaboration across disciplines and taxonomic silos. Initial steps within this framework are promising and show positive outcomes in both agricultural systems and in cancer therapy (Beckie et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2017). These successes encourage a holistic approach more generally to understand the process of resistance in other taxa, including fungi, plants and bacteria, thereby allowing us to at least keep pace with the Red Queen.

To rise to the challenge posed by the Red Queen Hypothesis, the research community must embrace a paradigm shift—one that unites the medical and agricultural fields under a shared evolutionary framework. Resistance across taxa stems from the same evolutionary principles, yet our responses remain fragmented along taxonomic lines. Despite society already having the necessary tools at hand, success at implementing these strategies is rare. To move forward, we must prioritize four key steps: first, embed evolutionary principles into the design of all interventions, ensuring strategies are anticipatory rather than reactive to resistance adaptations. Without evolutionary theory integrated in our strategies, resistance will keep evolving and circumventing our efforts. Second, we should foster cross-disciplinary collaborations that dismantle taxonomic silos, enabling researchers in agriculture, medicine, and beyond to share data, methods, and lessons learned. By integrating cross-disciplinary knowledge, we will evolve beyond focussing on proximate approaches such as developing new chemical compounds, to broaden the scientific fields’ views to holistic strategies. Third, we need to expand and harmonize existing approaches, such as Integrated Pest Management, One Health, prophylactic measures such as vaccines, and resistance-informed cancer therapies, to address resistance across taxa. Fourth, enable individuals such as farmers, nurses, and doctors, who will ultimately make use of these strategies by educating and funding them. These steps will require coordinated funding initiatives, global research networks, and a willingness to rethink traditional research boundaries. Only through these actions can we hope to develop and successfully implement sustainable, long-term solutions that keep pace with the relentless innovations of natural selection.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AN: Visualization, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ME: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. NW: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

In memoriam

In memory of Professor Mark Elgar, whose brilliant mind was pivotal to the creation of this manuscript. His stories and excitement towards academia and science will always be remembered fondly.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad M. and Khan A. U. (2019). Global economic impact of antibiotic resistance: A review. J. Global antimicrobial resistance. 19, 313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.05.024

Alphey L., McKemey A., Nimmo D., Neira Oviedo M., Lacroix R., Matzen K., et al. (2020). Genetic control of Aedes mosquitoes. Pathog. Global Health 107, 170–179. doi: 10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000095

Alyokhin A. V., Rosenthal B. M., Weber D. C., and Baker M. B. (2025). Towards a unified approach in managing resistance to vaccines, drugs, and pesticides. Biol. Rev. 100, 1067–1082. doi: 10.1111/brv.13174

FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH. (2022). One Health Joint Plan of Action 2022–2026. Working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment (Rome: FAO; UNEP; WHO; World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (founded as OIE).

Barzman M., Bàrberi P., Birch A. N. E., Boonekamp P., Dachbrodt-Saaydeh S., Graf B., et al. (2015). Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 1199–1215. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0327-9

Bass C. (2017). Does resistance really carry a fitness cost? Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 21, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.04.011

Bass C., Denholm I., Williamson M. S., and Nauen R. (2015). The global status of insect resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 121, 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.04.004

Beckie H. J., Busi R., Lopez-Ruiz F. J., and Umina P. A. (2021). Herbicide resistance management strategies: how do they compare with those for insecticides, fungicides and antibiotics? Pest Manage. Sci. 77, 3049–3056. doi: 10.1002/ps.6395

Bell B. G., Schellevis F., Stobberingh E., Goossens H., and Pringle M. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 1–25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-13

Bryan C. G., Hallberg K. B., and Johnson D. B. (2006). Mobilisation of metals in mineral tailings at the abandoned São Domingos copper mine (Portugal) by indigenous acidophilic bacteria. Hydrometallurgy. 83, 184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.03.023

Carozzi N. B. and Koziel M. (1997). Advances in insect control: the role of transgenic plants (USA: CRC Press).

Chantziaras I., Boyen F., Callens B., and Dewulf J. (2014). Correlation between veterinary antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in food-producing animals: a report on seven countries. J. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 69, 827–834. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt443

Cole K. A., Rivard K. R., and Dumkow L. E. (2019). Antimicrobial stewardship interventions to combat antibiotic resistance: an update on targeted strategies. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 21, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11908-019-0689-2

Daborn P. J., Yen J. L., Bogwitz M. R., Le Goff G., Feil E., Jeffers S., et al. (2002). A single P450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science. 297, pp.2253–2256. doi: 10.1126/science.1074170

Dadgostar P. (2019). Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infection Drug resistance. 3903–3910. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S234610

Deguine J. P., Aubertot J. N., Flor R. J., Lescourret F., Wyckhuys K. A., and Ratnadass A. (2021). Integrated pest management: good intentions, hard realities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 41, p.38. doi: 10.1007/s13593-021-00689-w

Denk-Lobnig M. and Wood K. B. (2023). Antibiotic resistance in bacterial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 74, 102306. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2023.102306

Denk-Lobnig M. K. and Wood K. B. (2025). Spatial population dynamics of bacterial colonies with social antibiotic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122, e2417065122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2417065122

Dorigatti I., McCormack C., Nedjati-Gilani G., and Ferguson N. M. (2018). Using Wolbachia for dengue control: insights from modelling. Trends Parasitol. 34, 102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.002

Ffrench-Constant R. H. (2007). Which came first: insecticides or resistance? Trends Genet. 23, 1–4. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.141895

Ffrench-Constant R. H. (2013). The molecular genetics of insecticide resistance. Genetics. 194, 807–815. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.141895

Ffrench-Constant R. H. (2017). Does resistance really carry a fitness cost? Current opinion in insect science. 21, 39–46.

Figueras A. (2024). A global call to action on antimicrobial resistance at the UN general assembly. Antibiotics. 13, 915. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13100915

Futuyma D. J. (1995). The uses of evolutionary biology. Science 267, 41–42. doi: 10.1126/science.7809608

Gatenby R. A. and Brown J. S. (2020). Integrating evolutionary dynamics into cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 675–686. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0411-1

Gibas K. M., van den Berg P., Powell V. E., and Krakower D. S. (2019). Drug resistance during HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Drugs. 79, 609–619. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01108-x

Goossens H., Ferech M., Vander Stichele R., and Elseviers M. (2005). Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 365, 579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17907-0

Gordillo Altamirano F. L. and Barr J. J. (2019). Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, 10–1128. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00066-18

Gould F. (1998). Sustainability of transgenic insecticidal cultivars: integrating pest genetics and ecology. Annu. Rev. entomology. 43, 701–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.701

Grochtdreis T., König H. H., Dobruschkin A., von Amsberg G., and Dams J. (2018). Cost-effectiveness analyses and cost analyses in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review. PloS One. 13, e0208063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208063

Harrop T. W., Sztal T., Lumb C., Good R. T., Daborn P. J., Batterham P., et al. (2014). Evolutionary changes in gene expression, coding sequence and copy-number at the Cyp6g1 locus contribute to resistance to multiple insecticides in Drosophila. PloS One. 9, e84879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084879

Hickman J. A. (1996). Apoptosis and chemotherapy resistance. Eur. J. Cancer. 32, 921–926. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00080-9

Hoffmann S., Pohl C., and Hering J. G. (2017). Exploring transdisciplinary integration within a large research program: Empirical lessons from four thematic synthesis processes. Res. Policy. 46, 678–692. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.01.004

Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., and Charpentier E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 337, 816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829

Kennedy D. A. and Read A. F. (2017). Why does drug resistance readily evolve but vaccine resistance does not? Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 284, 20162562. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2562

Kennedy D. A. and Read A. F. (2018). Why the evolution of vaccine resistance is less of a concern than the evolution of drug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 12878–12886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717159115

Kim C. J., Kim H. B., Oh M. D., Kim Y., Kim A., Oh S. H., et al. (2014). The burden of nosocomial staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in South Korea: a prospective hospital-based nationwide study. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0590-4

Kümmerli R. (2015). Cheat invasion causes bacterial trait loss in lung infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 10577–10578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513797112

Lucas J. A., Hawkins N. J., and Fraaije B. A. (2015). The evolution of fungicide resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 90, 29–92. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2014.09.001

Mayr E. (1961). Cause and effect in biology: kinds of causes, predictability, and teleology are viewed by a practicing biologist. Science. 134, 1501–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3489.1501

Morley V. J., Woods R. J., and Read A. F. (2019). Bystander selection for antimicrobial resistance: implications for patient health. Trends Microbiol. 27, 864–877. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.06.004

Moss S. R. (2010). “Non-chemical methods of weed control: benefits and limitations,” in 17th Australasian weed conference (CAWs, Christchurch), 14–19.

Natterson-Horowitz B., Aktipis A., Fox M., Gluckman P. D., Low F. M., Mace R., et al. (2023). The future of evolutionary medicine: sparking innovation in biomedicine and public health. Front. Sci. 1, 997136. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2023.997136

Ng L., Elgar M. A., and Stuart-Fox D. (2021). From bioinspired to bioinformed: benefits of greater engagement from biologists. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 790270. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.790270

Owen M. D. and Zelaya I. A. (2005). Herbicide-resistant crops and weed resistance to herbicides. Pest Manage. Science: formerly Pesticide Sci. 61, 301–311. doi: 10.1002/ps.1015

Palumbi S. R. (2001). Humans as the world’s greatest evolutionary force. Science 293, 1786–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5536.1786

Pearl Mizrahi S., Goyal A., and Gore J. (2023). Community interactions drive the evolution of antibiotic tolerance in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2209043119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2209043119

Pimentel D. (2010). “The effects of antibiotic and pesticide resistance on public health,” in Antibiotic Resistance: Implications for Global Health and Novel Intervention Strategies—Workshop Summary, 294–300.

Raymond B. (2019). Five rules for resistance management in the antibiotic apocalypse, a road map for integrated microbial management. Evolutionary Appl. 12, 1079–1091. doi: 10.1111/eva.12808

Reid S. A., McKenzie J., and Woldeyohannes S. M. (2016). One Health research and training in Australia and New Zealand. Infection Ecol. Epidemiol. 6, 33799. doi: 10.3402/iee.v6.33799

REX Consortium (2007). Structure of the scientific community modelling the evolution of resistance. PloS One. 2, e1275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001275

Schlenke T. A. and Begun D. J. (2004). Strong selective sweep associated with a transposon insertion in Drosophila simulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 1626–1631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303793101

Selvarajan R., Obize C., Sibanda T., Abia A. L. K., and Long H. (2022). Evolution and emergence of antibiotic resistance in given ecosystems: possible strategies for addressing the challenge of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics. 12, 28. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12010028

Ventola C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. 40, 277.

Walther V., Hiley C. T., Shibata D., Swanton C., Turner P. E., and Maley C. C. (2015). Can oncology recapitulate paleontology? Lessons from species extinctions. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 273–285. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.12

Wedell N. and Hosken D. J. (2017). Three billion years of research and development. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0035. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0035

Wedell N., Price T. A. R., and Lindholm A. K. (2019). Gene drive: progress and prospects. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20192709. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2709

Willemsen I., Bogaers-Hofman D., Winters M., and Kluytmans J. (2009). Correlation between antibiotic use and resistance in a hospital: temporary and ward-specific observations. Infection. 37, 432–437. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-8325-y

Zhang M., Liu E., Cui Y., and Huang Y. (2017). Nanotechnology-based combination therapy for overcoming multidrug-resistant cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 14, 212–227. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0054

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, coevolution, evolution, insecticide resistance, resistance

Citation: Nogueira Alves A, Elgar M and Wedell N (2026) Resolving resistance adaptations: an integrated, evolutionary perspective across taxonomic borders. Front. Ecol. Evol. 14:1719781. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2026.1719781

Received: 06 October 2025; Accepted: 05 January 2026; Revised: 18 December 2025;

Published: 29 January 2026.

Edited by:

Astrid T. Groot, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Mitchell Baker, Queens College (CUNY), United StatesCopyright © 2026 Nogueira Alves, Elgar and Wedell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andre Nogueira Alves, YW5kcmUubm9ndWVpcmFhbHZlc0B1bmltZWxiLmVkdS5hdQ==

†Deceased

Andre Nogueira Alves

Andre Nogueira Alves Mark Elgar†

Mark Elgar†