- Faculty of Environment, School of Environment, Resources, and Sustainability, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

In sustainability education affective responses to climate change are rarely discussed, and this is to the detriment of students. One way to address this gap in higher education for sustainability is learner-centred teaching using transformative learning principles. The processes for implementation may vary. Our preliminary study evaluated the contribution of environmental films paired with viewer-response activities, such as reflections and discussions, to create emotional engagement and facilitate transformative learning in an online course where content focused on sustainability and climate change. Data for the study were gathered through two questionnaires, student reflections, and interviews. Our study found that the process of film watching, reflection writing, and engaging in discussion was conducive to incorporating five of the six elements of transformative learning: individual experience, promoting critical reflection, awareness of context, dialogue, and authentic relationships. We conclude that films are an effective means of conveying complex content in an online course pertaining to climate change and sustainability. We propose pairing films with viewer-response strategies, especially reflections to allow students to identify their feelings, biases, and preconceived frames of references and stimulate the path toward transformative learning in higher education.

Introduction

The science is clear – anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are increasing global temperatures, destabilising many Earth systems, and endangering human societies reliant on those systems (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). Yet despite this consensus, attempts to stimulate action in political or social bodies that would counteract climate change has been painfully slow (Moser, 2020). Part of this inaction is due to an inability to imagine new ways of living (Yusoff and Gabrys, 2011) and, especially in the wealthy West, to acknowledge affective or emotional responses to climate change (Norgaard, 2011; Head, 2016). This lack of affective awareness is most clearly seen in the way students are instructed about these environmental issues (Ray, 2020; Verlie, 2021). Despite at least a decade of research from psychologists demonstrating that knowledge about the impacts of climate change is affecting human mental health (Doherty and Clayton, 2011), affective responses to this crisis are rarely discussed in sustainability education, and this is to the detriment of students.

Since the adoption of the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) by the United Nations (2005–2014), there has been an interest in bringing transformative learning into higher education (Balsiger et al., 2017). There have been several studies as well as a teaching framework called “Work that Reconnects” that have strived to connect transformative learning to sustainability topics such as natural resources management (Diduck et al., 2012), ecological crisis (Hathaway, 2017), and sustainable consumption (Sahakian and Seyfang, 2018). Currently a framework has been proposed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2019) for implementing ESD beyond 2019, which includes transformation action as a key component.

Transformative learning as a theory was first advanced by Mezirow (1978), drawing influences from Kuhn’s (1962) conception of paradigms, Freire (1970) ideas of conscientisation, and Habermas’ (1971) domains of learning (Kitchenham, 2008). Transformative learning builds on these ideas and recognises the key role of an individual’s frames of reference (perspectives), through which individuals view and interpret their experiences and derive meaning (Mezirow, 1991). A key component of this is reflecting on assumptions that have been accepted without critical thought and “overcoming limited, distorted, or arbitrarily selective modes of perception and cognition” (Mezirow, 1991, p. 5). Transformative learning theory is not without its criticisms (Howie and Bagnall, 2013). One such criticism by Taylor (1997) is the missing role of emotions, which Mezirow (2010, p. 29) acknowledges, restating that transformative learning theory “involves how to think critically about assumptions supporting one’s perspectives and to develop critically reflective judgment in discourse regarding one’s beliefs, values, feelings, and self-concepts.”

This revised idea of transformative learning may be the pathway to engaging students in climate change and sustainability education. Climate change educators from around the world have sought to engage students emotionally (Ray, 2020; Verlie, 2021) because the lack of motivation to act on climate change is not apathy or scepticism, but rather a reflection of “socially constructed silence” (Pihkala, 2018, p. 549). One way to overcome this silence is to cultivate spaces to discuss climate change and the emotions it evokes (Norgaard, 2011; Verlie, 2019; Hendersson and Wamsler, 2020). Hathaway (2017) points out that feelings of fear, guilt, shame, and even dread are natural and understandable when confronted with the ecological crisis, which relates to the feelings that often accompany disorienting dilemmas – the first phase in transformative learning (Mezirow, 2010). Creating such spaces in higher education to examine feelings and recognise the shared experience of climate change impacts will require a combination of balancing power structures (Weimer, 2002, p. 74) and integrating the core elements of transformative learning, which are individual experience, promoting critical reflection, dialogue, holistic orientation, awareness of context, and authentic relationships (Taylor, 2009). These elements form the framework for the 10 phases of learning in the transformative process, the first five of which are: a disorienting dilemma, self-examination (including feelings), a critical assessment of assumptions, recognising the connection between one’s discontent and transformation process and that others have navigated similar changes, and exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and action (Kitchenham, 2008; Mezirow, 2010).

Following this, our study evaluated the extent of transformative learning in an online course where content was primarily conveyed through films. While agreeing on what constitutes transformative learning may be difficult in practice (Drikx and Smith, 2009, p. 64), our study proposes that transformative learning can be fostered in the classroom with the process of watching films as the disorienting dilemma trigger, followed by reflection writing to enable the second and third phases of transformative learning, and finally peer-to-peer dialogue to stimulate the fourth and fifth phases. The extent of transformative learning can be evaluated by examining students’ emotional and cognitive reactions as well as their ability to confront biases and preconceptions in self-reflections and engage with communication of complex themes in discussions.

Materials and Methods

The novel undergraduate environmental film course had originally been planned for in-person offering. It was designed to convey content regarding climate change and sustainability through films in popular culture and allow undergraduate students to critically engage with their affective responses to these complex issues. Anticipating interdisciplinary interest in the course, the syllabus was constructed to be introductory in scope to engage students from various faculties within the university. However, the shift to online teaching due to COVID-19 precautions presented the unique challenge of engaging students with these films in an online environment and formed the motivation for this exploratory study. Therefore, funding was sought through a learning innovation and teaching enhancement grant to investigate how effective films can be as a paedagogical tool to promote experiential learning within an online teaching environment. However, the design of the course more aptly fits within the transformative learning framework than experiential learning according to the comparison of frameworks by Strange and Gibson (2017).

Course Design

The learning objectives of the course intended students to:

1. Critically examine assumptions that have been part of (their) existing knowledge base.

2. Recognise the underlying complexities associated with human development and environmental sustainability and communicate the accompanying emotions.

3. Understand and explain the roles of, and challenges associated with, contemporary film in defining, analysing, and resolving environmental issues.

4. Critically analyse and evaluate both fiction and non-fiction films’ environmental claims and proposed solutions from different disciplinary perspectives.

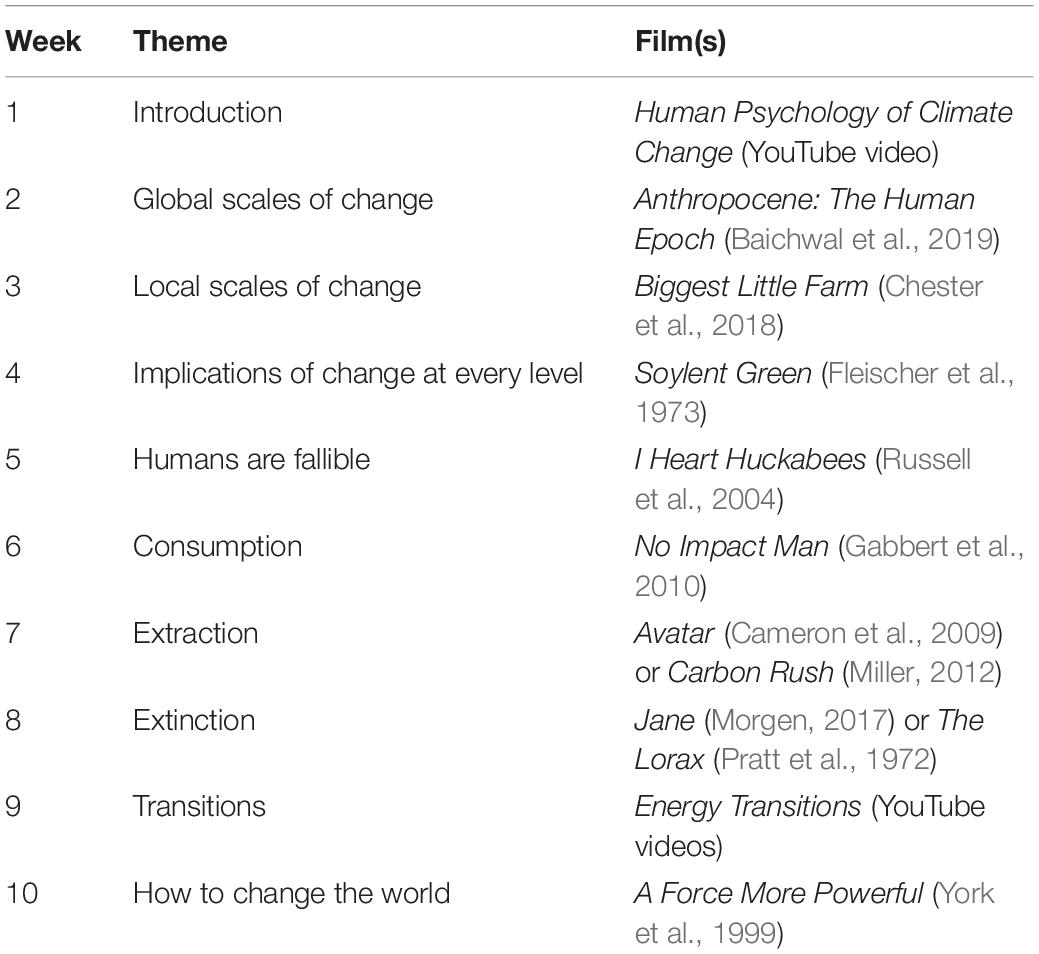

Each week of the course focused on a different theme paired with films that exemplified that theme, scaffolding the topics of sustainability from global scales of change to local scales of change to issues of overconsumption, extraction, extinction, and pollution, and finally, how to change the world. The themes for each week along with the corresponding films are outlined in Table 1. Films were used as the course media because (1) films allow the educator to play the role of facilitator rather than instructor, and facilitation helps create a balance of power with and among learners (Weimer, 2002); (2) they are multi-sensory tools, which can be an effective way to communicate the complexities of environmental problems in accessible ways (Weik von Mossner, 2017); and (3) they provide the opportunity for active and meaningful discussion, promoting understanding through interaction with others (Petkari, 2017). The balance of power is vital to creating learning conditions to facilitate learner-centred teaching, which is focal to transformative learning (Taylor, 2009; Aboytes and Barth, 2020).

The course combined environmental films with viewer-response strategies inspired by and adapted from reader-response paedagogy (Davis, 1992). Students watched the films on their own, at their own pace, and were provided a week to reflect on the films. Students were also required to contribute posts to discussion themes every 2 weeks. The Framework for the Implementation of ESD Beyond 2019 (UNESCO, 2019, Annex II 4), rephrases Mezirow’s concept of a disorienting dilemma as “a certain level of disruption opting to step outside the safety of the status quo or the ‘usual’ way of thinking.” Mezirow (1991) adds that critical self-reflection, based on premise reflection, can help reassess previously unexamined assumptions. To enable this, students were pre-assigned weekly reflection prompts before each week’s film to promote expression of initial reactions (thoughts and feelings) and exploration of changes in both perspective and self-awareness. The prompt questions were designed to not only encourage students to reflect on content but also on the premise of learning to become more aware of their own preconceptions as viewers and learners. The discussion board themes also had prompt questions to spark conversation and debate. The aim was to enhance the dialogue between two or more students after having immersed in critical self-reflection (Aboytes and Barth, 2020).

Study Design and Analysis

This exploratory research study ran concurrent to the course and was prompted by the desire to explore the effectiveness of films as a paedagogical tool and to investigate the impact of viewer-response activities (reflections and discussions) on emotional and cognitive engagement of undergraduate students. Films for the course were selected based on their connection to the themes of the course and their availability through the university’s streaming service (Criterion) and YouTube. Further selection criteria included diversity in types of film (e.g., documentary, fiction, live action, and animated) as well as a spectrum of emotional messaging (e.g., uplifting, disheartening, and thought-provoking) to ensure structured and intended student exposure to disorienting dilemmas (Aboytes and Barth, 2020).

Participants were gathered from the pool of students in the environmental film course, which had an enrolment of 29 students. The study received guidance and approval from the Office of Research Ethics. In accordance with ethics requirements, the prospective participants were provided an information letter with a brief overview of the research, and a participation form to record their consent for the various components of this research, including participation in two questionnaires (administered online through Qualtrics), permission to use reflection assignments, and participation in an exit interview (administered online through Microsoft Teams). To prevent undue influence or pressure as well as acquiescence bias in responses, the instructor was not involved in any part of the recruitment, consent, or data collection. The research assistant managed all communications with potential and consenting participants, collected data, and de-identified study files. It was communicated to the students that the instructor would not have access to the study files until all marks were published for the course. Even after the course was over, the instructor would only receive de-identified files.

In total, there were twelve participants from three faculties (ten from the Faculty of Environment and one each from the Faulty of Arts and the Faculty of Health). Not only were these participants from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, but they also ranged in total years at the university: one participant was in their first year, three in their second year, four in their third year, and four participants graduated shortly after completing this course. The small sample size limits the validity of statistical analyses but provides valuable information as a preliminary study.

The questionnaires were made available to the participating students at two points in time, once at the beginning and once at the end of the term. Both questionnaires were identical and designed to gauge changes in opinion over the duration of the term. The questions consisted of short answer and five-point Likert scale statements for which students had a choice to rate each statement on a scale of 1–5 where 1 was strongly disagree and 5 was strongly agree. The one exception was for the question asking about climate change concern where 1 was not concerned at all and 5 was very concerned. The questionnaires were analysed quantitatively using R-software for statistical significances within three categories: (1) climate change, (2) emotional awareness, and (3) films. In the analyses, the answers were grouped together for response comparison within the categories and over time, from beginning to end of term.

The individual reflections from consenting students were analysed to evaluate emotional and cognitive engagement as well as to assess the extent of transformative learning. Each reflection contained five questions, four of which had standard wording (Supplementary Material). The flow of the questions follows Mezirow’s (1991, p. 109) premise that continued learning is dependent on “what we have learned, how we have learned it, and whether our presuppositions are warranted.” Question 1 always asked about students’ feelings and thoughts during and after the film, Question 2 always asked students to convey the key message from the film in accessible language, Question 3 was film-specific, Question 4 asked students to reflect on any changes in perspective, and Question 5 asked students to reflect on what they learned about themselves by watching the film. The reflections were analysed for sentiment using R-software and the Bing Liu Lexicon (Hu and Liu, 2004). Sentiment analysis allows for automatic determination of a writer’s feeling in text by evaluating the number of positive and negative words used in the text. The quantitative nature of sentiment analysis allowed for analysis of variance (ANOVA) using R-software to explore statistical significance in sentiment from week to week for the 10 weeks of reflection submissions. Additionally, text query of the reflections was conducted using stemmed words “feel” and “think” (including past tense), “learn,” “aware,” and “bias” to explore trends in student emotional and cognitive awareness. Starting at Week 5, the students received a rubric (Supplementary Material) to provide further clarity on the evaluation criteria for each question. Of particular interest in transformative learning were Questions 4 and 5. The exception to the standard reflection prompts is the last reflection for Week 10 (Supplementary Material).

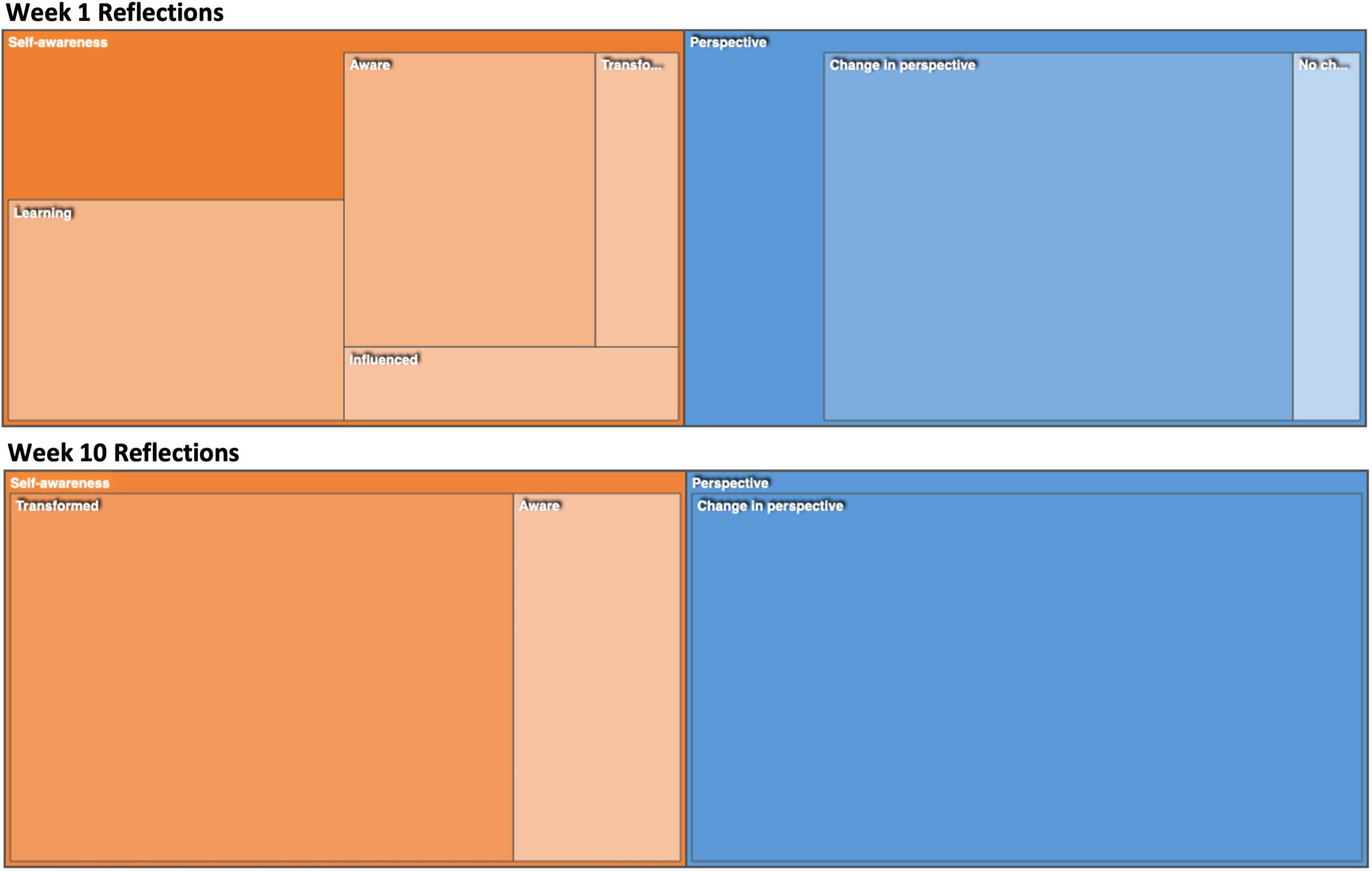

Given the structured nature of the course where each reflection had standard prompts and corresponded to a specific film, a theoretical approach to thematic analysis was applied as opposed to an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The thematic analysis for Question 4 (“Has this film changed your perspective? Elaborate and give examples of how”) was coded under two categories: change in perspective or no change in perspective. On the other hand, the thematic analysis for Question 5 (“What are 2 things you learned about yourself while/after watching this film?”) was coded for self-awareness under four categories: Influenced, Learning, Aware, and Transformed. For Week 10, the questions transitioned to: “What is your outlook now on environmental sustainability? What actionable learnings do you feel you will integrate into your education going forward?” The questions were designed to evaluate the extent of transformation from self-examination to empowerment and/or individual action [i.e., phase 5 of transformative learning: exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and action (Mezirow, 2010)] at the end of the course.

Additional data were gathered through semi-structured interviews after the completion of the course to assess students’ perspectives of films for content delivery and engagement with viewer-response activities, including reflections and discussion posts. The online interviews, each averaging about one hour, were conducted one-on-one with the research assistant on the Microsoft Teams platform. During the interviews participants were asked open ended questions (Supplementary Material) encouraging them to reflect on various aspects of the course as well as the impact of learning from films in an online environment. Data from the interviews were qualitatively analysed through NVivo.

Results

The results demonstrated that while students found films to be an engaging tool for online course delivery, it was the viewer-response activities (reflections and discussions) that most helped them gain a deeper understanding of the content and themselves – their perspectives, their preconceptions, and their biases. Films were found to be effective at eliciting feelings that correspond to a disorienting dilemma and the weekly reflective writing helped students align their thoughts and feelings, stimulating the transformative learning process by engaging with emotions and shifting perspectives. Analysis of interviews showed that participants enjoyed the discussion posts because the posts allowed them to engage with differing perspectives from their peers. The results also emphasise the important role of the instructor as a facilitator – in providing guidance (a rubric), feedback, and encouraging critical reflection.

Disorienting Dilemma of Climate Change in Film

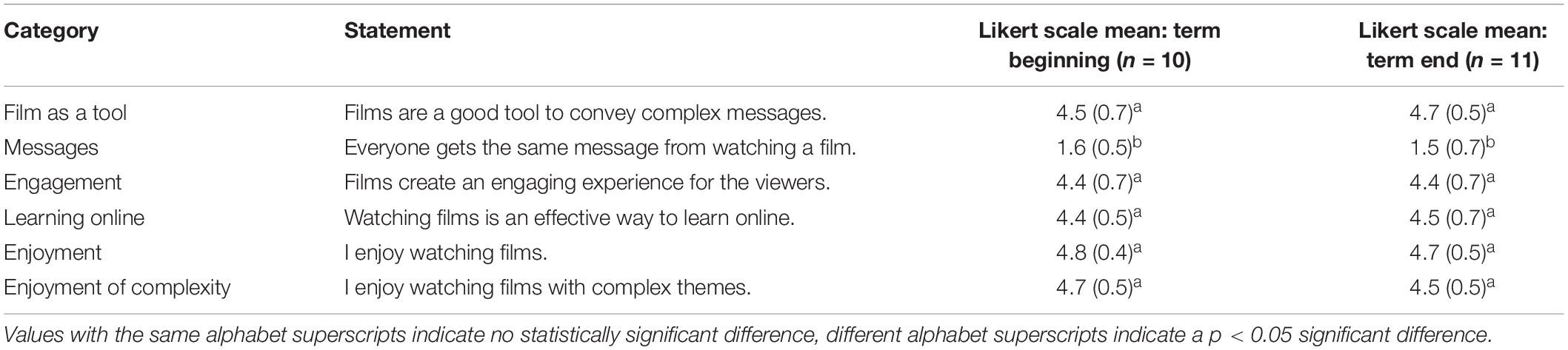

With respect to films, the questionnaires asked the students about engagement, enjoyment, and messaging. The results showed that students think highly of films as an effective way to learn online, a tool for conveying complex messages, and an engaging and enjoyable experience. These opinions did not change significantly at the end of the term (Table 2). The students also strongly disagree that everyone gets the same message from films. Therefore, students recognise that while films can convey complex messages, individual viewer experiences may vary.

Table 2. Opinions of films as an engaging and enjoyable tool for conveying complex messages in online learning, students were asked to rate each statement on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

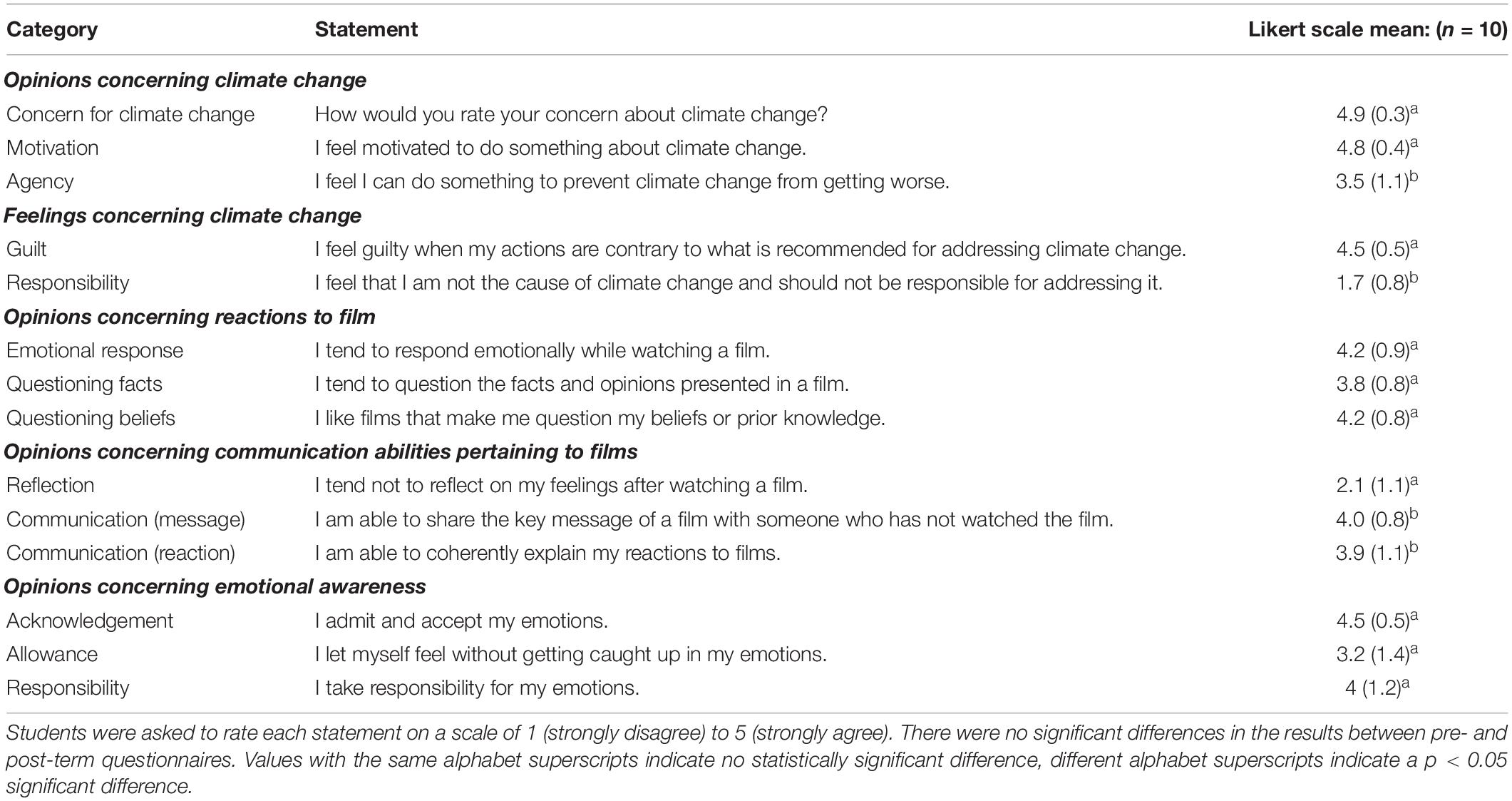

With respect to climate change, students were asked in the questionnaires about their concern, their motivation, and feelings of agency related to climate change. Additionally, students were asked whether they felt guilty when performing actions that are contrary to addressing climate change and if they feel they are responsible for addressing climate change. While there were no statistically significant differences in the responses to these questions between the beginning and end of term questionnaires, there were some notable patterns within each questionnaire. One was the statistically significant difference between concern and agency as well as between motivation and agency related to climate change (Table 3). Students who participated in this research (and this course) are highly concerned and motivated to do something about climate change but are less confident in having agency over the situation. There were also significant differences between feelings of guilt and feelings of not being the cause of climate change at both the beginning and end of term (Table 3), which demonstrates that not only do the students feel guilty for taking actions contrary to addressing climate change, they also feel responsible for actions that contribute to climate change.

Table 3. Likert scale results from the pre-term questionnaire grouped under five groups: opinions concerning climate change, feelings concerning climate change, opinions concerning reactions to film, opinions concerning communication abilities pertaining to films, and opinions on emotional awareness.

These feelings were confirmed in the reflections for Week 2 in reaction to the documentary film, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018). When asked to reflect on the prompt question, “How do you feel about inheriting a world where climate change is a primary concern for the future of the human race?”, participants responded with a variety of feeling words, including anxious, saddened, distraught, burdened, overwhelmed, distressed, angry, frustrated, disappointed, hopeless, irritated, upset, fearful, worried, stressed, cheated, resentful, and daunted. One analogy that stood out from the reflections was, “It is essentially like inheriting a hoarder’s items and trying to dig yourself out of the mess they have created.” The variety of feeling words exhibited in this week’s reflection demonstrated the power of climate change impacts on the participants and the power of film to bring these feelings to the surface, to elicit the disorienting dilemma of climate change. Two of the twelve participants also added optimism and seeing a glimmer of hope as feelings, one of whom said “I am optimistic because of the generation that the world is being handed to. I have seen so many young people rising up to take action and call upon those in power to make a difference.”

Presented with the openness and vulnerability of students’ emotions to climate change, the instructor implemented feedback in each week’s reflection based on (1) acknowledging the sharing of feelings, (2) relating the response to question instruction and rubric (once implemented), and (3) encouraging further exploration or providing open-ended inquiries. For example, “I like how you’ve described the mix of feelings and connected each to different aspects of the film using one example from the film – I encourage you to describe the specific scenes/concepts that are connected to your feelings/thoughts to help explain them further” or “Thank you for sharing these feelings and thoughts! I like how you use examples from the film to share your reactions. One point [I would] like you to explore further in your own time is when you mention ‘can we as environmentalists even win?’ – I wonder how winning should be defined for environmentalists.”

Engaging Emotion and Cognition Through Reflective Writing

Film content affects students’ emotions, which is self-reported in the questionnaire results, explicitly expressed in the reflections, and supported by sentiment analysis of reflection writing. Students reported responding emotionally to films and enjoying films that make them question their beliefs or prior knowledge (Table 3). Students also reported tendencies to reflect on their feelings after watching a film and being able to communicate both the key message of the film and their reactions to the film. They are also likely to admit and accept their emotions and take responsibility for their emotions. They are, however, less likely to let themselves feel without getting caught up in their emotions. There were no statistically significant differences in self-reported emotional awareness responses in the questionnaires between beginning and end of term.

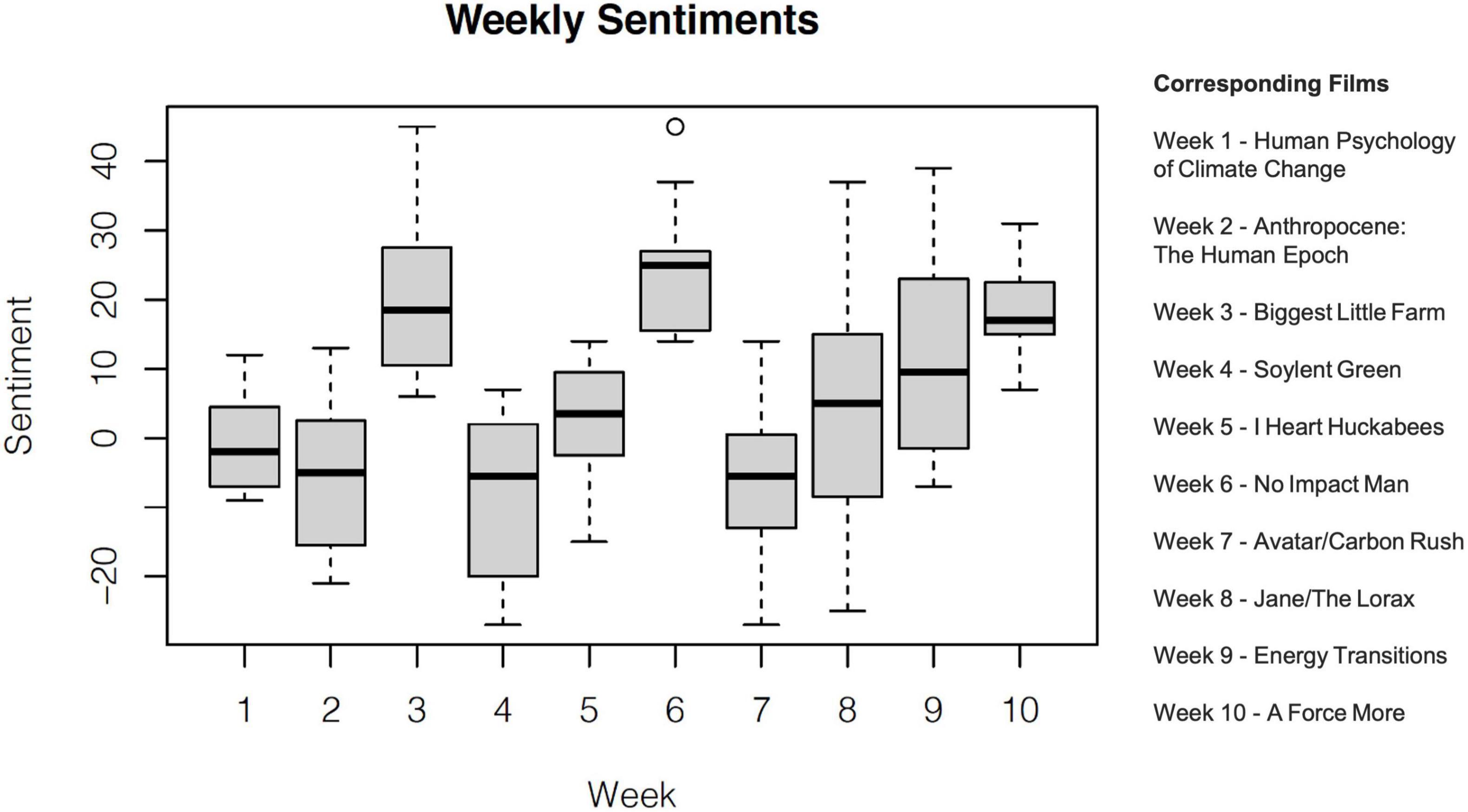

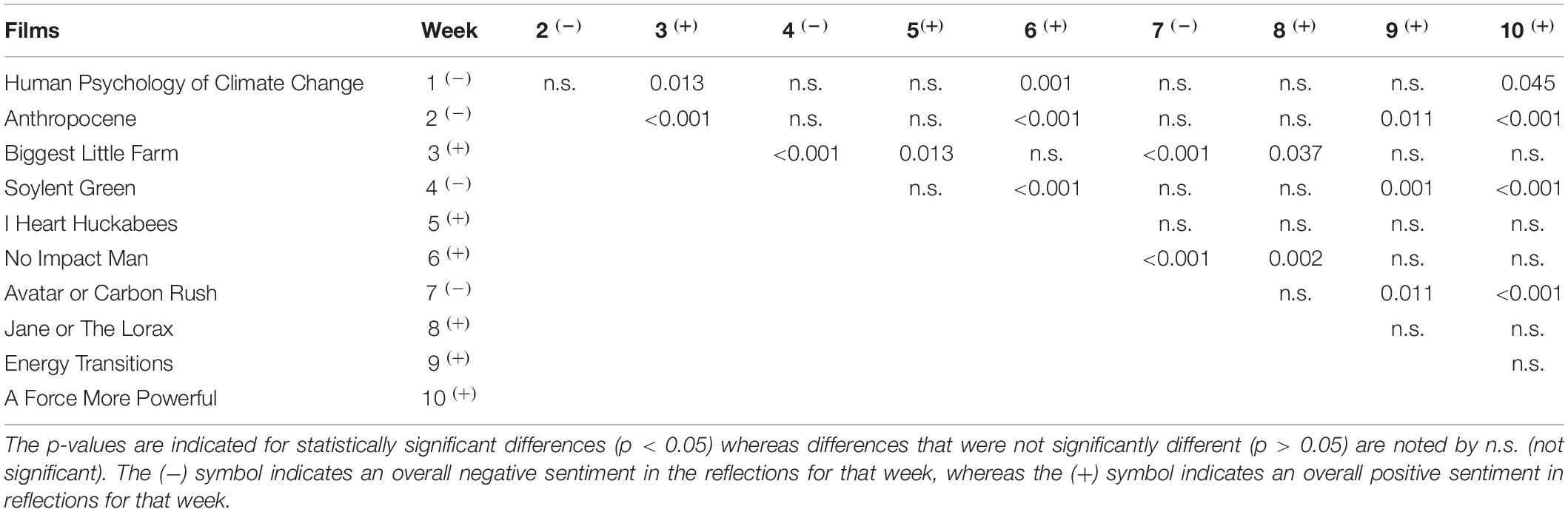

Text queries of the stemmed words “feel” and “think” showed that students tend to reflect through “thinking” more than “feeling” (Figure 1). The sentiment analysis for student reflections revealed that students had overall negative emotions for Weeks 1, 2, 4, and 7, whereas their emotions were overall positive for the remaining weeks (Figure 2 and Table 4). The themes for Weeks 1 and 2 were Climate Change and Global Scales of Change, more specifically the damage and destruction that has been caused by humans over time, conveyed through two short YouTube videos and the documentary Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018). The theme for Week 4, Changes at Every Level, was conveyed through the 1973 film, Soylent Green, which projects into the future (year 2022) the grim consequences of overpopulation. In their reflections, students were asked to discuss similarities and differences between the fictional year 2022 of the film and the actual year 2020 that had just passed. In their writing students expressed shock at the number of similarities they found, including wealth disparity, inequitable access to food, loss of biodiversity, and warming oceans. One participating student wrote “It’s frightening to think that it was easier to spot similarities than it was differences” while another expressed dismay, saying “This film paints quite the dystopian picture of the future in all aspects of life. Should we not correct course, I can definitely see at least the environmental aspects of this dystopia becoming more real. It is unfortunate that there are visible similarities at all.”

Figure 1. Frequency of “feel” versus “think” words in reflection assignment over 10 weeks, using stemmed text query (which includes words with the same root, e.g., feeling and thinking).

Figure 2. Stem-and-leaf plots of sentiment analysis for weekly reflections using R-software and the Bing Liu Lexicon (Hu and Liu, 2004).

Table 4. Analysis of variance Tukey HSD statistics summary comparing sentiments in reflection texts between the 10 thematic weeks.

There were statistically significant differences between Week 3 and many other weeks of reflection (Weeks 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8). The film for Week 3 was a documentary titled The Biggest Little Farm (2018), an uplifting film about a couple resolving to move out of the city, buy a farm, and learn to farm sustainably. For the reflections in Week 3, students were asked to envision their ideal world in 50 years and the participating students had overall positive visions, two of which were:

“My vision for the world in 50 years is that we will be living more equitably than we are now. As well that everyone is living free of fear and doubt, we have time for family, friends and leisure.”

“Hopefully, things will be a little less centralized though, so we’re less dependent on expensive repairs from one company and more dependent on our community networks. It would be really cool to have like solarpunky [sic.] neighbours who come over to fix my rooftop solar panels and then stay for a drink that I brewed at home.”

However, some students see more than one trajectory, each dependent on the current actions of human beings, which is exemplified by the following paragraph from a student’s reflection that uses the films to help visualise the future pathways:

“I have two visions for the world 50 years from now. The first vision is one that relates more to the Anthropocene film that we watched last week, where humans are going to extract so many resources that the consequences will be immense, and the world will be destroyed. My second vision is inspired by [The Biggest Little Farm] and the David Attenborough ‘A Life on Our Planet’ film, which makes me feel that we still have the power to reverse everything that we have done, so if we take action now in 50 years we will be living in a beautiful and healthy world.”

The sentiments in Weeks 6, 9, and 10 were also significantly more positive than Weeks 1, 2, 4, 7, and 8. The film for Week 6 was another documentary, No Impact Man (2009), which was an uplifting story about an author from New York who decides to embark on a zero-waste journey for a year with his family (wife and toddler daughter). The movie follows their journey, struggles, and successes in reducing their reliance on mass consumerism and even electricity. The themes for Weeks 9 and 10 were Transitions and How to Change the World. These uplifting stories demonstrated a corresponding positivity in students’ reflection writing. The themes for Weeks 7 and 8 were extraction and extinction with films like Avatar (2009), Carbon Rush (2012), Jane (2017), and The Lorax (1972), which narrated through powerful imagery the impacts of extraction on communities, particularly indigenous populations, and the ultimate negative consequences of human negligence on both people and environment.

The participating students acknowledged the importance of reflection in understanding the films, as a student stated, “I usually do not take the time to reflect on the movies that I watch, and by doing so in this course, I realized that I am able to better convey the message of the film and I can better understand the meaning of the movie by reflecting about it.” They also recognised the value in reflecting after watching each film, as one student pointed out “My reflections from each week have been really helpful to better understand my initial reactive thinking to films…I found that my immediate reactions were not always the same after a few [days’] time.” Additionally, participants recognised the importance of reflections in expressing their feelings, as one student aptly wrote “I find that in university and academic spaces, feelings are often regarded as insignificant or irrelevant, especially in most research, where you are expected to remain bias-free and impartial. However, through the reflections, I’ve learned the importance of recognising my feelings and my biases to get a better understanding of my thoughts on the issue.”

Shifting Perspectives and Communicating Complexity

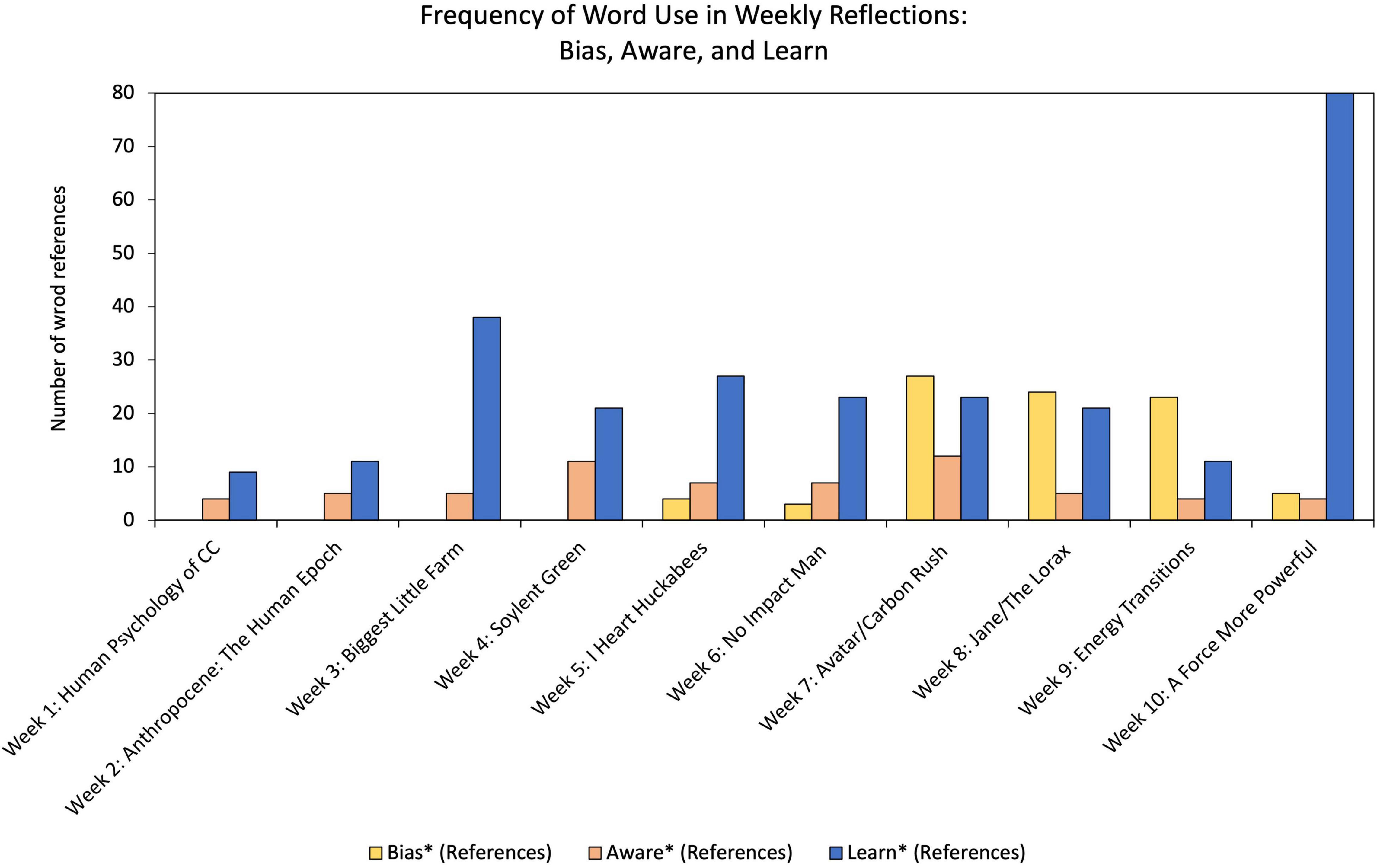

While students reported enjoying films that made them question their beliefs or prior knowledge, they did not strongly believe that they questioned facts or opinions presented in a film (Table 3). Analyses of the reflections showed that students also require guidance and prompting to allow deeper exploration of their existing frames of reference (beliefs, prior knowledge, perceptions, biases, and stereotypes). Text queries for the stemmed words “bias,” “aware,” and “learn” (Figure 3) indicate that students did not use the word “aware” very frequently in their texts, with a count of less than 10 references each week, except for Weeks 4 and 7, which were both weeks of strongly negative sentiment. The frequency of the word stem “bias” only begins at Week 5 when the rubric was introduced, increases during Weeks 7–9, and drops again to less than 10 references for Week 10. The reference count for the word stem “learn” is greater than both “bias” and “aware” from Weeks 1–6 and has a large surge in Week 10 where the question focused on what they learned through the course.

Figure 3. Frequency of “bias,” “aware” versus “learn” words in reflection assignment over 10 weeks, using stemmed text query (which includes words with the same root, e.g., biased, awareness, and learning).

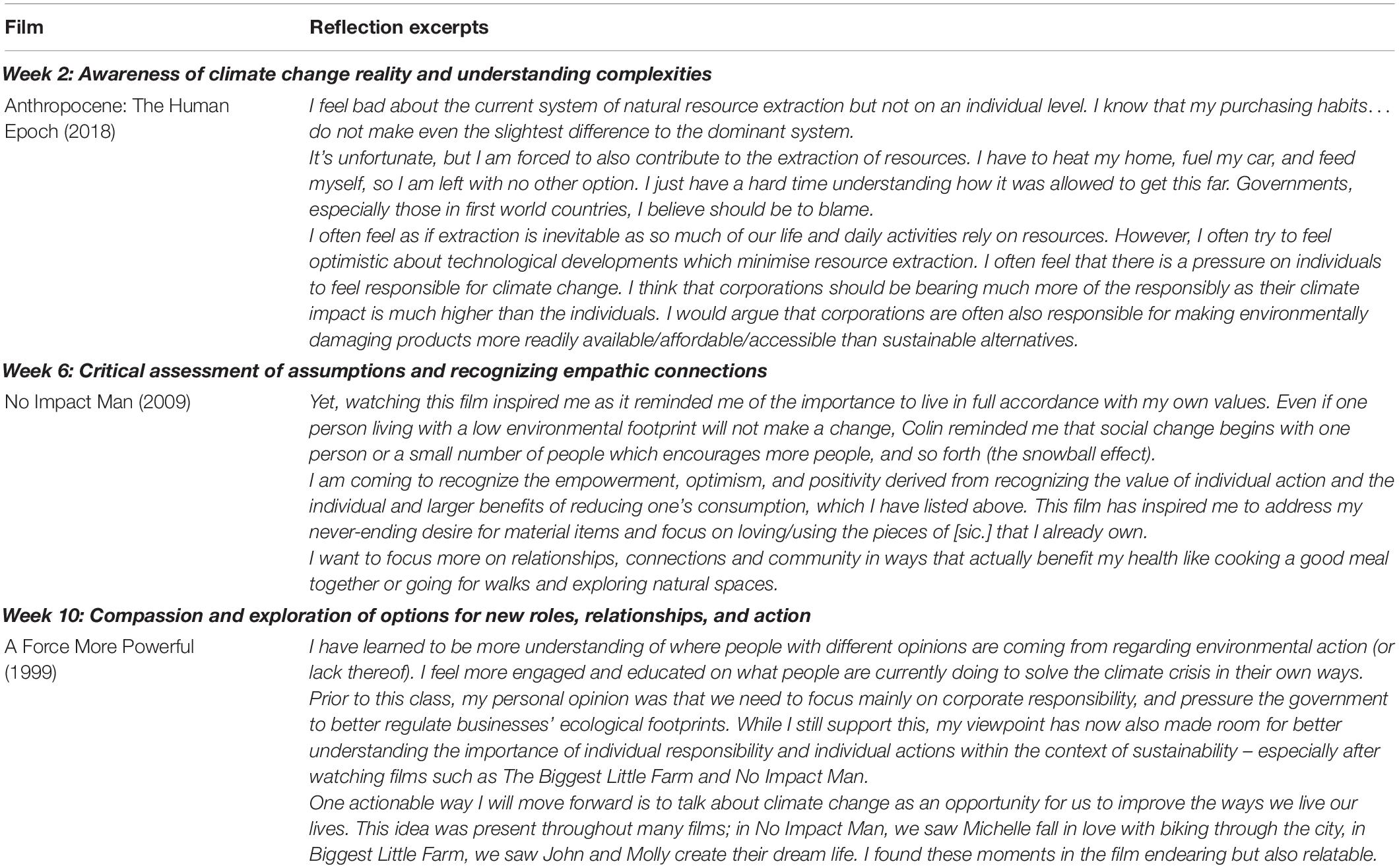

The thematic analyses on reflections from Week 2 (Anthropocene: The Human Epoch), Week 6 (No Impact Man), and Week 10 (A Force More Powerful) convey a compelling progression in perspective shifts toward individual action (Table 5). In Week 2 participants divulged more feelings than in Weeks 6 or 10. The feelings related to climate change were powerful, as was discussed above. While they acknowledged that individuals are also responsible for contributing to climate change, the participants strongly believed that governments and corporations hold the primary responsibility and power to make changes. However, at Week 6 after watching No Impact Man, there was evidence of influenced self-awareness that resulted in demonstrated shifts in perspectives toward individual action. Participants reflected on how individual action should not be negated and that living in line with their values is a life to aspire to. The impact of this perspective shift carried into Week 10 final reflections that asked about actionable change.

Table 5. Select quotes from Week 2, 6, and 10 reflections that exemplify the journey of transformative learning from awareness of context and reality to exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and action (phase 5 of the transformative learning process).

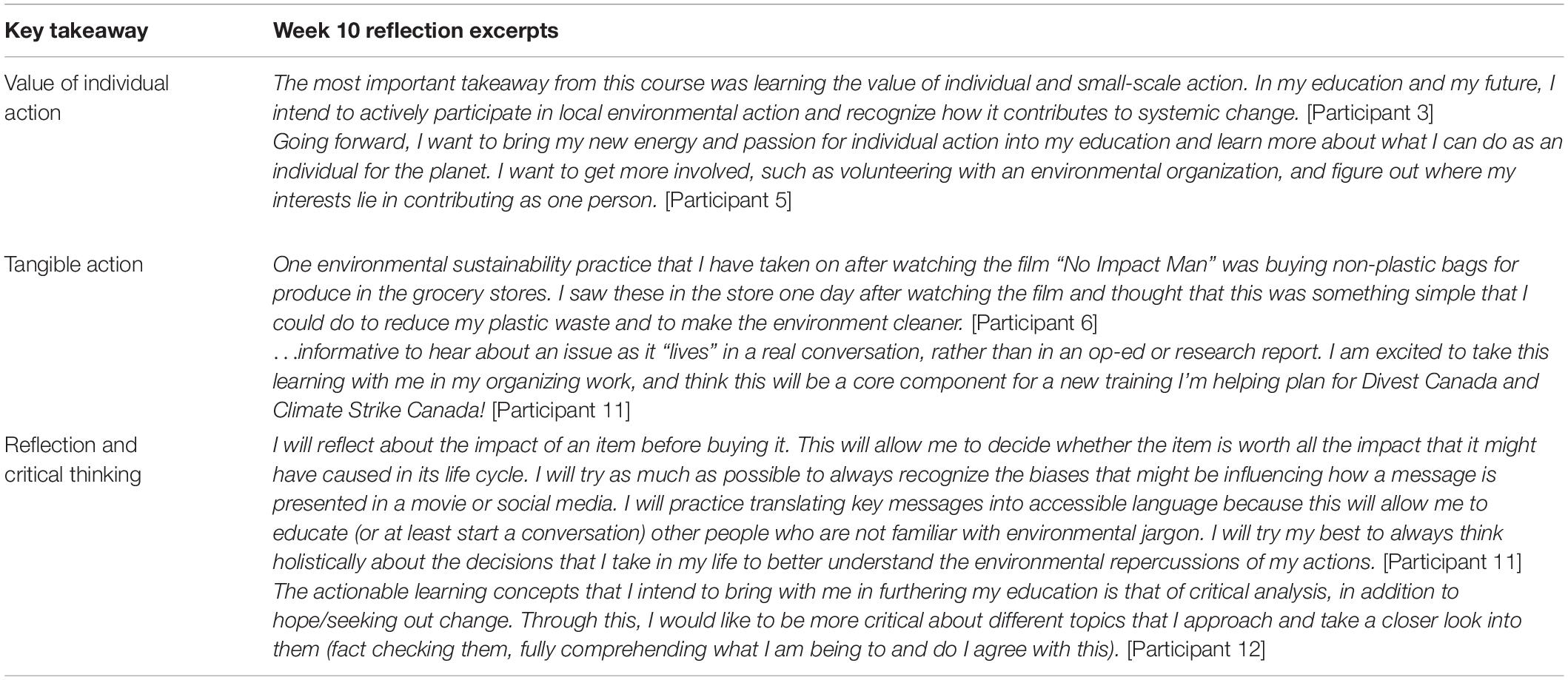

It is important to underline that shifts in perspective are not necessarily changes in opinion. The participants still hold the opinion that there are bigger contributors to climate change who have the responsibility and power to create change. However, they are also recognising the value of their own role as individuals. The writing changes from a hopeless narrative in Week 2 to one of optimism and understanding in Weeks 6 and 10, which is also noted in the sentiment analysis. Coding analysis of the reflections for perspective changes and self-awareness showed an improvement over the duration of the term. All participating students exhibited growth from being influenced to becoming aware and transformed through guided reflection of films (Figure 4). The analyses also show that some students participating in the study were already predisposed to transformative learning from the first week of the course. Shifts in perspective are not necessarily indicative of complete transformation in learning but do infer the potential to achieve transformation and can be compared to the 10 phases of the transformative learning process to determine the extent of transformative learning. Select excerpts from Week 10 reflections (Table 6) help further demonstrate the extent of transformative learning at the end of term after the consistent process of watching a film, reflecting on the film, and discussing the film with peers (online) over a 10-week period. The excerpts are categorised as: the value of individual action, tangible action, and reflection and critical thinking.

Figure 4. Changes from Week 1 (beginning of term) to Week 10 (end of term) in coding categories for perspectives and self-awareness coding in weekly reflections. Awareness is defined as self-examination and a critical assessment of assumptions (second and third phases of the transformative learning process). Transformed is defined as the recognition of connection between one’s discontent and transformation process and exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and action [fourth and fifth phases of the transformative learning process as defined by Mezirow (2010)].

Table 6. Select quotes from Week 10 reflections articulating transformative learning through key takeaways from the course.

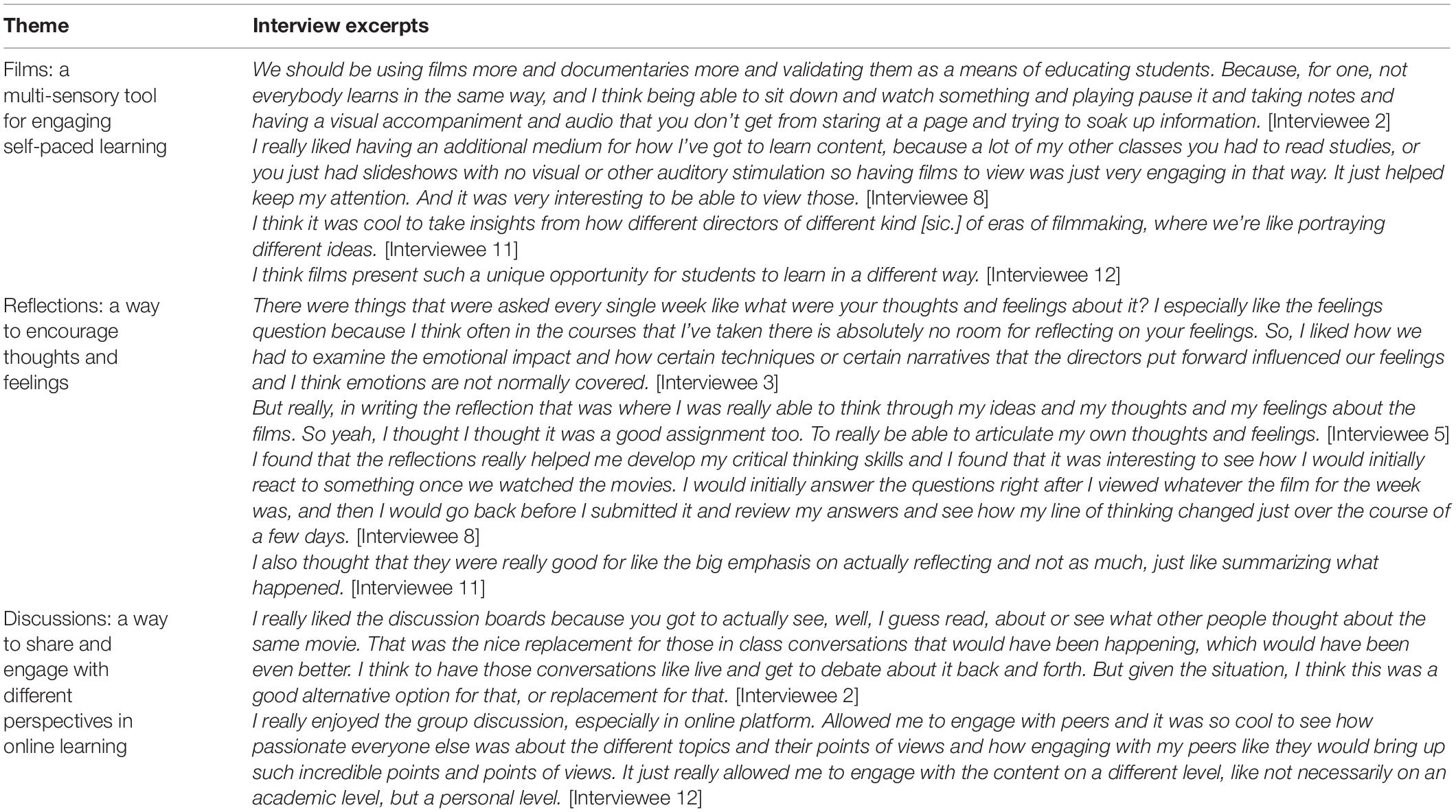

One key component of the reflections that students found valuable was being asked to write the key message of the film in accessible language. The responses to the question improved the participants’ ability to talk about climate change, as one participant wrote, “the reflections allowed me to start very good conversations with my family regarding the films that I watched. This was due to the fact, that we had to write in accessible language the key message of the movie, which allowed me to approach my family with the right words for them to understand what I wanted to tell them.” Another participant shared, “One effective communication tool that I thoroughly enjoyed in this class was explaining complex messages in an accessible way. I feel that this skill has helped me have better conversations with friends and family members and explain complex issues so that they can understand. I enjoy finding metaphors that friends/family members could relate too [sic.], and it seems that they also find this effective.” Additionally, the interviews revealed that one of the online discussion boards were a memorable aspect of the course as they allowed participants to engage with varying perspectives presented by their peers. Select excerpts from interviews (Table 7) reveal the lasting impact of the films, reflections, and discussions with peers.

Table 7. Select quotes from exit-interviews elaborating on student engagement with films in an online learning environment and the attitudes toward the viewer-response activities of reflection and discussion.

Discussion

Transformative learning strives to explain by what processes perspectives are changed or transformed in adult learning structures (Mezirow, 1991). The process employed in this study to stimulate perspective change in higher education was film watching, followed by critical reflection, and discussing with peers repeated on a weekly basis for 10 weeks in online learning. According to Taylor (2009, p. 4), there are six core elements of transformative learning, which are incomplete without a balance of power in the classroom (Weimer, 2002). We categorise the findings of this research into five of the core elements for further discussion: individual experience, promoting critical reflection, awareness of context, dialogue, and authentic relationships.

Individual Experience

Students are concerned about climate change and do not feel they have agency, though they are motivated to address climate change. Students also experience guilt when their actions feel contrary to addressing climate change. Quesada-Embid (2016, p. 57) describes this as “green guilt,” which is the “emotional sentiment associated with an awareness of not making choices according to what is best for the environment and sustainability when one wants to.” We showed in this preliminary study that the use of environmental films evoked the feelings of guilt, fear, and dread that Hathaway (2017) found to be natural in the face of ecological crisis. American environmental humanities scholar Ray (2020, p. 2) discovered that when she led her class in a reflective exercise to envision “what it would feel and look like to live in a climate-changed future in which all the positive results of all their collective efforts had come to pass,” her students failed to give her any positive visions. Ray’s students were unable to give her an answer not because they were unwilling to engage with her question, but rather because they were overwhelmed by their emotional reaction to a climate-changed future. In the reflections from Week 3, we showed that students were able to engage with the question of envisioning the future 50 years from now and demonstrated that while some are hopeful, others saw the divergence of futures depending on human actions today and express worry for the worst-case scenarios. Ray (2020) concludes that movement toward acting on climate change will require engagement with feelings about this issue. We found that environmental films were able to provide that engagement and enabled participants to experience how others are navigating a changing world – through both uplifting and disheartening documentaries – and express the emotions accompanying these experiences through reflections. This is aligned to sociologist Norgaard’s (2011, p. 9) work, which aims to integrate “the emotional and psychological experiences of noticing or thinking about climate information.” The caution to facilitators when engaging with student emotions is to not “use fear, guilt, or shame as motivating forces [as this may] distance, disempower, and undermine solidarity” (Hathaway, 2017, p. 300). Instead, we recommend instructors acknowledge student feelings without judgement and provide students with a rubric. A good rubric can outline expectations and encourage students to further explore their reactions to course content. In this study, we found that the introduction of a rubric in Week 5 led to further self-awareness in reflections.

Whether students realise or not, their writing reflected the sentiment of the films they were assigned, which varied week to week from documentaries to fictional stories and from doom-and-gloom to uplifting narratives. According to Verlie (2019, p. 758), the process of recognising and discussing emotions related to climate change and the future was a crucial step for her students in learning how to “live-with [sic.] climate change.” She believes that for her students (and others) to change their behaviour and act on climate change, they first need to acknowledge the emotions (both positive and negative) that climate change evokes. The written reflections demonstrated that students do indeed let themselves feel as they self-reported in the questionnaires. However, they express more cognitively than emotionally. While the reflections carried strong sentiments that related to the intended sentiments of the films being viewed, students demonstrated a higher frequency of cognitive processes (using “think” words) instead of emotional processes (using “feel” words) in their writing. Kron et al. (2010) argue that the focus on feelings (experience of emotion) consumes mental resources that may also be concurrently required for cognitive tasks, thus leading to a reduction in intensity of feelings. Therefore, the act of writing a reflection for a course under the pressure of deadlines and meeting rubric criteria may explain the lower frequency of “feel”-related text. In which case, assessing students’ reflective writing can be complemented with sentiment analysis, which proved to be a useful quantitative assessment in this preliminary study. Nonetheless, the process of reflecting on thoughts and feelings surrounding sustainability themes each week allowed students to become more aware of themselves as viewers and learners, which connects to phase 2 of the transformative learning process: self-examination (Mezirow, 2010).

Critical Reflection and Awareness of Context

Students recognised that reflective exercises allowed them to improve their critical thinking skills and their ability to articulate their thoughts, which they were then able to share on the online discussion forums. According to Quesada-Embid (2016, p. 58), critical self-reflection that bridges the personal with the academic and open dialogue are the paths to addressing the sentiment of “green guilt” and encouraging individuals to take impactful and meaningful steps to addressing climate change. Therefore, the critical reflections and discussion posts in this course are in line with the path prescribed, while the films are conducive to bringing the feelings of “green guilt” and other sentiments to the surface.

Students came into the course with existing frames of reference that were built on beliefs or prior knowledge that may have been taken for granted. However, the reflections from this preliminary study demonstrated progress in student self-awareness over the term. According to Mezirow (1997, p. 27):

“…the process by which we construe our beliefs may involve taken-for-granted values, stereotyping, selective attention, limited comprehension, projection, rationalization, minimizing, or denial. These considerations are reasons that we need to be able to critically assess and validate assumptions supporting our own beliefs and expectations and those of others.”

The surges in the words “learn” and “bias” starting at Weeks 3 and 5, respectively, indicate the response of students to the feedback provided by the instructor from previous reflection submissions as well as the introduction of a comprehensive rubric. The rubric provided clear expectations and urged students to explore further learning about themselves, especially their beliefs, biases, preconceptions, and prejudices they have as a viewer of the films and as learners acquiring knowledge through films. Student bias is a subject of interest in business ethics (Tomlin et al., 2021) and medical sciences (Motzkus et al., 2019) where implicit biases have an impact on clinical decision-making but have not yet been explored in-depth in other fields of study. Because films are subjective, they can convey varying messages along with implicit biases, which are important for students to recognise and compare against their own existing frames of reference as well as their values.

According to the Framework for Implementation of ESD Beyond 2019 (UNESCO, 2019), the stages of individual transformation are: acquisition of knowledge, awareness of certain realities, understanding complexities of realities through critical analysis, empathic connections to realities through experience, and resulting in compassion and solidarity. The excerpts demonstrating the journey of students from Week 2 to Week 6 to Week 10 illustrate the transformation of participants in this study from awareness of context to empathic connections (Table 5). As was advanced by Drikx and Smith (2009, p. 65), the role of teachers and facilitators is to help learners make deep connections with the content and create the potential for transformative learning, though ultimately it is on the students to take that leap in their learning experience. Nonetheless, facilitators play a critical role of creating the safe space for sharing feelings and thoughts without judgement and encouraging students to question their preconceived frames of reference, which has been explored through arts-based approaches to transformative learning (Butterwick and Lawrence, 2009), has been advanced through this preliminary study in sustainable education, and is recommended for further investigation with films in higher education regardless of field of study.

Dialogue and Authentic Relationships

Films are an engaging learning method, reflections allow for exploration of thoughts and feelings, and discussions are a way for sharing and engaging different perspectives, which are all in line with the core elements of transformative learning as described by Taylor (2009, p. 4). Participating students enjoyed engaging with their peers’ differing points of view, which was consistent with findings of Sullivan and Longnecker (2014) who implemented class-maintained blogs that increased class interaction and enjoyment of intellectual exchange with other students. The participants also emphasised the importance of online discussion as a replacement to in-person conversations in classrooms. This was a surprising result as discussion posts were obligatory and counted toward the students’ grade, impelling students to post to the discussion themes on a biweekly basis. However, the inclusion of online discussion as a viewer-response activity provided the social presence component that students need for personal connection (Ensmann et al., 2021), especially given the shift to fully online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. One key advantage of the online film course was that there was sufficient time and space provided for reflection and discussion, which is one of the most often cited favourable learning conditions for transformative learning (Aboytes and Barth, 2020).

There were many moving parts in this course and its research design. The course assessments warranted heavy time commitment for the instructor toward marking reflections and balancing meaningful feedback conducive to student-teacher dialogue, acknowledging difficult emotions, and pushing students to move beyond superficial or surface level awareness toward deeper personal growth and perspective transformation. This resonates with the experiences of Drikx and Smith (2009, p. 65) who found that “engaging, accepting, and helping students work through emotional dynamics” is a challenging dimension of transformative teaching, especially in an online environment. The balance of power relations in the feedback dialogue between instructors and students is important to maintain as a learning condition to encourage a sense of agency and empowerment (Aboytes and Barth, 2020). Therefore, this research recognises that educators who engage in fostering transformative learning should do so with forethought and planning as it requires intentional action and a genuine concern for student learning (Taylor, 2009). Additionally, it requires educators to appreciate and evaluate their own assumptions and beliefs about the content being taught as well as the purpose of fostering transformative learning (Taylor, 2009).

Study Limitations and Recommendations for Further Study

An important limitation in this exploratory study was the low participation rate (12 participants out of 29 enrolled students). Difficulties in recruitment were a common occurrence with other studies also trying to recruit in the term when this course took place as was communicated to the investigators by the grant funders. The students had also received advertising for one other study being conducted by a fellow classmate in the same term. Additionally, the course was an optional special topics course with a course code that was shared with another course in the same term offering; therefore, enrolment in the course was lower than anticipated.

While the course was advertised to all six faculties of the university, students from only three faculties enrolled and participated in the study, a majority of whom were from the Faculty of Environment. Therefore, it is recognised that by the act of having enrolled in this course, the pool of students for the study was skewed toward interest in, and concern for, climate change and its impacts, which may contribute to the ceiling effect. Here, we use the definition of Ho and Yu (2015), that the ceiling effect is insufficient precision of measurement to enable distinguishing differences in the upper regions of a score scale. In this case, the effect of a small, self-selected sample influenced survey results with Likert scale responses being very close to the upper threshold limit and the lack of significant changes over the term. Precautions were taken to limit acquiescence bias by starting the survey with a short answer response and providing participants with a five-point Likert scale as opposed to binary choices of agreement for the statements. Additionally, the survey statements varied in positive and negative wording, encouraging participants to consider the question and reduce response bias. In this preliminary study, low participation and ceiling effect limit the rigour of the statistical analyses presented. Additionally, the results demonstrating transformative learning are limited to the time duration of the course and the interviews (total of 5 months). The lasting impacts of some transformations observed in this study would need to be verified over a longer duration or through follow-up interviews with participants to gauge follow-through of intended individual actions.

It is unlikely the ceiling effect would have been avoided if the sample size within the pool of students in this course offering had been larger than 12 with the survey design that was used. For future studies, we recommend expanding the sample size to participants recruited from disciplines other than the Faculty of Environment and using a seven-point Likert scale instead of a five-point Likert scale to increase reliability and validity of the questionnaire responses (Taherdoost, 2019). A larger study with control groups could also provide deeper insight into the impact of films and viewer-response activities on transformative learning. If the course had been in-person, the progression of watching the film, writing the reflection, then discussing would have been synchronous and likely more compressed in time than it was in the online offering. For future studies with in-person classes, we recommend honouring the linear progression and providing time and space for students to reflect on the films immediately after watching it before implementing peer-to-peer discussion. The act of reflecting allows students to process their thoughts and feelings, develop their own point of view, and acknowledge their biases, which we posit leads to more open-minded and respectful dialogue. Further studies can explore this hypothesis by manipulating the three-component linear sequence.

Conclusion

We conclude that films are a very effective and engaging tool for online course delivery, which should be integrated more readily and with intention in higher education classrooms, especially in courses with complex topics like sustainability or climate change and courses that take place online. Films may also serve as a venue for triggering a disorienting dilemma, which is the first phase of the transformative learning process. However, films alone are not effective at engaging student cognitive and emotional awareness or setting them on the path toward transformative learning. It is critical to pair films with viewer-response activities, such as individual reflections to explore their feelings and articulate their thoughts, allowing them to explore their preconceptions, biases, and existing frames of reference through guided prompts, and online discussions where they can articulate their perspectives and learn from the perspectives and experiences of their peers. The viewer-response activities enable progress from the second to the fifth phases of transformative learning process. Using films to convey content with viewer-response strategies encourages a balance of power within the classroom as the learning model is not one-way from instructor to student, but rather a three-way learning model that focuses on student-centred learning. Student emotions and biases are elements not frequently explored or evaluated in higher education. Allowing for emotional exploration is recommended in sustainability education as course content contains complex topics relevant to both the students’ academic and personal lives. Therefore, the process of film watching, followed by reflection writing and peer-to-peer discussions was shown to be effective at challenging student preconceptions and frames of reference in this preliminary study and, with appropriate implementation and nurturing by the educator, may facilitate transformative learning in sustainability education.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SE made primary contributions to the manuscript working collaboratively with MM-R. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We acknowledge funding and support from the Centre for Teaching Excellence’s Learning Innovation and Teaching Enhancement (LITE) Grant and the School of Environment, Resources, and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo.

Author Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kyle Scholz from the Centre for Teaching Excellence and Simon Courtenay from the School of Environment, Resources, and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo for their support of this research. We also thank Nickolas Rollick for supporting manuscript revisions.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.836988/full#supplementary-material

References

Aboytes, J., and Barth, M. (2020). Framework for the implementation of education for sustainable development (ESD) beyond 2019 - UNESCO digital library. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21, 993–1013. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-05-2019-0168

Baichwal, J., Burtynsky, E., Pencier, N. D., and Vikander, A. (2019). Anthropocene: The Human Epoch. Toronto, ON: Mercury Films.

Balsiger, J., Förster, R., Mader, C., Nagel, U., Sironi, H., Wilhelm, S., et al. (2017). Transformative learning and education for sustainable development. GAIA - Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 26, 357–359. doi: 10.14512/gaia.26.4.15

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Quali. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butterwick, S., and Lawrence, R. (2009). “Creating alternative realities: arts-based approaches to transformative learning,” in Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights From Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, eds J. Mezirow and E. W. Taylor (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 35–45.

Cameron, J., Worthington, S., Saldana, Z., and Weaver, S. (2009). Avatar. Los Angeles, CA: Twentieth Century Fox.

Chester, J., Chester, J., Chester, M., and Chester, B. (2018). The Biggest Little Farm. Los Angeles, CA: Diamond Docs.

Davis, J. R. (1992). Reconsidering readers: louise rosenblatt and reader-response pedagogy. Res. Teach. Dev. Educ. 8, 71–81.

Diduck, A., Sinclair, A. J., Hostetler, G., and Fitzpatrick, P. (2012). Transformative learning theory, public involvement, and natural resource and environmental management. J. Environ Plan. Manag. 55, 1311–1330. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2011.645718

Doherty, T. J., and Clayton, S. (2011). The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 66, 265–276. doi: 10.1037/a0023141

Drikx, J., and Smith, R. (2009). “Facilitating transformative learning: engaging emotions in an online context,” in Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights From Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, eds J. Mezirow and E. W. Taylor (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 57–66.

Ensmann, S., Whiteside, A., Gomez-Vasquez, L., and Sturgill, R. (2021). Connections before curriculum: the role of social presence during covid-19 emergency remote learning for students. Online Learn. 25, 36–56. doi: 10.24059/olj.v25i3.2868

Fleischer, R., Heston, C., Robinson, E. G., and Taylor-Young, L. (1973). Soylent Green. Los Angeles, CA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Gabbert, L., Schein, J., Beavan, C., and Conlin, M. (2010). No Impact Man: The Documentary. New York, NY: Shadowbox Films Inc.

Hathaway, M. D. (2017). Activating hope in the midst of crisis: emotions, transformative learning, and “the work that reconnects.”. J. Transform. Educ. 15, 296–314. doi: 10.1177/1541344616680350

Head, L. (2016). Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene, Routledge Research in the Anthropocene. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hendersson, H., and Wamsler, C. (2020). New stories for a more conscious, sustainable society: claiming authorship of the climate story. Clim. Change 158, 345–359. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02599-z

Ho, A. D., and Yu, C. C. (2015). Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 75, 365–388. doi: 10.1177/0013164414548576

Howie, P., and Bagnall, R. (2013). A critique of the deep and surface approaches to learning model. Teach. High. Educ. 18, 389–400. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2012.733689

Hu, M., and Liu, B. (2004). “Mining and summarizing customer reviews,” in Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’04 (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 168–177. doi: 10.1145/1014052.1014073

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The evolution of john mezirow’s transformative learning theory. J. Transform. Educ. 6, 104–123. doi: 10.1177/1541344608322678

Kron, A., Schul, Y., Cohen, A., and Hassin, R. R. (2010). Feelings don’t come easy: studies on the effortful nature of feelings. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 139, 520–534. doi: 10.1037/a0020008

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago,IL: University of Chicago Press.

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., et al. (Eds). (2021). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Educ. 28, 100–110. doi: 10.1177/074171367802800202

Mezirow, J. (1997). “Transformative learning: theory to practice’,” in Transformative Learning in Action: Insights from Practice – New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, ed. P. Cranton (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Mezirow, J. (2010). “Transformative learning theory,” in Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, eds J. Mezirow and E. W. Taylor (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 18–31.

Miller, A. (2012). The Carbon Rush. Byron A. Martin Productions, Wide Open Exposure Productions, Bell Broadcast and New Media Fund.

Moser, S. C. (2020). The work after “It’s too late” (to prevent dangerous climate change). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11:e606. doi: 10.1002/wcc.606

Motzkus, C., Wells, R. J., Wang, X., Chimienti, S., Plummer, D., Sabin, J., et al. (2019). Pre-clinical medical student reflections on implicit bias: implications for learning and teaching. PLoS One 14:e0225058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225058

Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Petkari, E. (2017). Building beautiful minds: teaching through movies to tackle stigma in psychology students in the UAE. Acad. Psychiatry 41, 724–732. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0723-3

Pihkala, P. (2018). Eco-Anxiety, tragedy, and hope: psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon® 53, 545–569. doi: 10.1111/zygo.12407

Pratt, H., Albert, E., Holt, B., and Lorde, A. (1972). The Lorax. The Cat in the Hat Productions. Burbank, CA: DePatie-Freleng Enterprises (DFE).

Quesada-Embid, M. C. (2016). “Eco-crimes and eco-redemptions: discussing the challenges and opportunities of personal sustainability,” in Learner-Centered Teaching Activities for Environmental and Sustainability Studies, ed. L. B. Byrne (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 57–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-28543-6_6

Ray, S. J. (2020). Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. Oakland, CA: University of California.

Russell, D. O., Schwartzman, J., Law, J., and Watts, N. (2004). I Heart Huckabees. Century City, CA: Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Sahakian, M., and Seyfang, G. (2018). A sustainable consumption teaching review: from building competencies to transformative learning. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.238

Strange, H., and Gibson, H. J. (2017). ‘An investigation of experiential and transformative learning in study abroad programs’. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 29:85–100. doi: 10.36366/frontiers.v29i1.387

Sullivan, M., and Longnecker, N. (2014). Class blogs as a teaching tool to promote writing and student interaction. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 30, 390–401. doi: 10.14742/ajet.322

Taherdoost, H. (2019). What is the best response scale for survey and questionnaire design; review of different lengths of rating scale / attitude scale / likert scale. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 8, 1–10.

Taylor, E. W. (1997). Building upon the theoretical debate: a critical review of the empirical studies of mezirow’s transformative learning theory. Adult Educ. Q. 48, 34–59. doi: 10.1177/074171369704800104

Taylor, E. W. (2009). “Fostering transformative learning,” in Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, eds J. Mezirow and E. W. Taylor (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 3–17.

Tomlin, K. A., Metzger, M. L., and Bradley-Geist, J. (2021). Removing the blinders: increasing students’ awareness of self-perception biases and real-world ethical challenges through an educational intervention. J. Bus. Ethics 169, 731–746. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04294-6

UNESCO (2019). “Framework for the implementation of education for sustainable development (esd) beyond 2019 united nations educational, scientific and cultural organization,” in Proceedings of the General Conference 40th Session (Paris).

Verlie, B. (2019). Bearing worlds: learning to live-with climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 751–766. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2019.1637823

Verlie, B. (2021). Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation. London: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9780367441265

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Weik von Mossner, A. (2017). Affective Ecologies: Empathy, Emotion, and Environmental Narrative. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

York, S., Kingsley, B., Allende, S., and Arasteh, S. (1999). A Force More Powerful. Santa Monica Pictures. Wellington: WETA.

Keywords: films, sustainability, higher education, reflection, emotional engagement, online learning, transformative learning

Citation: Esmail S and Matthews-Roper M (2022) Lights, Camera, Reaction: Evaluating Extent of Transformative Learning and Emotional Engagement Through Viewer-Responses to Environmental Films. Front. Educ. 7:836988. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.836988

Received: 16 December 2021; Accepted: 01 March 2022;

Published: 25 March 2022.

Edited by:

Lili-Ann Wolff, University of Helsinki, FinlandReviewed by:

Nancy Longnecker, University of Otago, New ZealandPradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, India

Copyright © 2022 Esmail and Matthews-Roper. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shefaza Esmail, c2hlZmF6YS5lc21haWxAdXdhdGVybG9vLmNh

Shefaza Esmail

Shefaza Esmail Misty Matthews-Roper

Misty Matthews-Roper