- 1School of Education, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Woosong Language Institute, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

This study aims to study how the incorporation of digitized heritage buildings into blended English as a second language (ESL) teaching can facilitate Students’ attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target of quality education, specifically increasing cultural awareness and consciousness of global citizenship. Based on the lens of social cognitive theory and case study approach, the researchers collected qualitative data from 40 participants who enrolled in a blended English-as-a-Second Language course in a community college in the United States. The results indicated that cultural heritage and buildings in the blended language learning curriculum, expanding the knowledge to other subject matter, and beyond the book were the three main themes. Based on the current course and curriculum designs with the elements of cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs, students expressed positive experiences in the fields of second language acquisition, employments of the computer-aided and technologically assisted tools, and interdisciplinary knowledge. University leaders, department heads, curriculum developers, instructors, and trainers should use this study as the reference to reform and upgrade their current materials with cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs in order to offer the comprehensive training to college and university students.

Introduction

The background of the study

Heritage has been defined by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre (UNESCO., 2022) as tangible and intangible assets with significant historical and cultural elements and value to the people inhabiting a given location or to tourism. Heritage can be categorized into two groups: natural and cultural. Natural heritage refers to assets in the natural environment, such as physical and biological items. Cultural heritage refers to institutions, buildings, monuments, fine arts, ideas, and intangible knowledge and practice ranging from human behaviors to practices, food, lifestyle, personal beliefs, religion, language, customs, social identity, and memories (Blake, 2000; Lowenthal, 2005). Heritage education refers to the pedagogical procedures by which individuals and groups can gain knowledge and practical experience of historical facts and assets via a designated curriculum. Learners can gain an understanding of historical facts and a sense of protection and recognition of the history and cultural practice (Mendoza et al., 2015). Although some schools have established individual courses and modules for heritage education, scholars have argued that heritage education could be incorporated into different subject areas.

One of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) relating to quality education is the appreciation of cultural diversity and global citizenship among learners (SDG target 4.7) (United Nations [UN], 2020; UNESCO/UNICEF, 2021). However, the attainment of this goal has been disrupted by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in developing countries (Iivari et al., 2020; United Nations [UN], 2020). First, the impossibility of learners returning to campus causes difficulties in delivering knowledge and organizing activities related to global citizenship and cultural diversity (Iivari et al., 2020; United Nations [UN], 2020). Second, the negative impact on learners’ mental well-being leads to interpersonal alienation and a feeling of meaninglessness (Hu et al., 2022). Such attitudes further discourage learners from making consistent commitments and collective efforts to engage in movements of global citizenship, and from becoming active change-makers due to falling student mobility and poorer chances of international cooperation (Ghosh and Jing, 2020).

Studies in the past decade (Baticulon et al., 2021; Van Doorsselaere, 2021) have shown that incorporating cultural heritage buildings into education can raise Students’ awareness of global citizenship and cultural awareness. Through immersion in the study of heritage buildings through field trips or excursions, students are able to situate themselves in relation to historical phenomena embracing the past, present and future, thereby fostering deeper reflection on the relationships between humanity, the environment and history (Van Doorsselaere, 2021). However, school closures, lockdowns and public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have made such in-person connection impossible (Baticulon et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, technology has given teachers and trainers an alternative means to provide similar learning experiences to students by incorporating digitized buildings into their teaching (Wang et al., 2021). In response to UNESCO’s call to digitize cultural heritage, many countries have created free electronic archives of their heritage buildings (Ott and Pozzi, 2011). Customized views of these heritage buildings and the use of specific software to rotate or zoom in to them allows teachers and trainers to focus on specific details as showcases of the original context and natural context of these buildings (Ott and Pozzi, 2011).

While some scholars (Ott and Pozzi, 2011; Van Doorsselaere, 2021) have investigated the benefits of incorporating digitized cultural buildings in various settings such as museums and tourist spots, as well as the implementation of cultural buildings in geography and history classes, it should be acknowledged that a holistic framework and an interdisciplinary approach across various subjects or key learning areas in the K-12 and post-secondary educational setting is still necessary to attain the SDG of quality education (Biasutti and Frate, 2017; Biasutti et al., 2018). Among the literature related to incorporating digitized cultural heritage buildings into education, few studies have examined the implementation of digitized cultural buildings in language subjects in relation to the attainment of SDG and language learning goals. It is only known from previous studies (Summers et al., 2005; Winter, 2007) that language teachers are not generally motivated to incorporate elements of sustainable development into their teaching, so that students perceive it as irrelevant to the subjects. However, some teachers do endeavor to incorporate such elements into their classroom to arouse Students’ cultural awareness and sense of global citizenship in the pursuit of language learning goals (Bekteshi and Xhaferi, 2020; Kwee, 2021). To assess the effectiveness of the incorporation of digitized cultural heritage buildings in community college settings in relation to the attainment of the SDG, it is necessary to examine how such incorporation is effected.

The purpose of the study

This study aims to study how the incorporation of digitized heritage buildings into blended English as a second language (ESL) teaching can facilitate Students’ attainment of the SDG target of quality education, specifically increasing cultural awareness and consciousness of global citizenship (SDG 4). By examining the experiences of students learning the English language in their classrooms, the researchers identified the strategies for implementing digitized cultural heritage and buildings into teaching and attaining SDGs. The effective strategies identified in this study are a practical indicator of a model for incorporating digitized cultural heritage buildings into English Language teaching to attain English language learning objectives and the SDG target of quality education. With this aim, the research is guided by two questions:

(1). How do students describe their learning experience of English language classes incorporating cultural heritage, buildings, and sense of SDGs into the blended learning environments?

(2). What are the strategies for incorporating digitized cultural heritage, building, and sense of SDGs toward the successful attainment of SDG4, quality education in aspects of cultural awareness and global citizenship, particularly in the blended ESL classroom environment?

Theoretical frameworks and relevant literature

Social cognitive theory

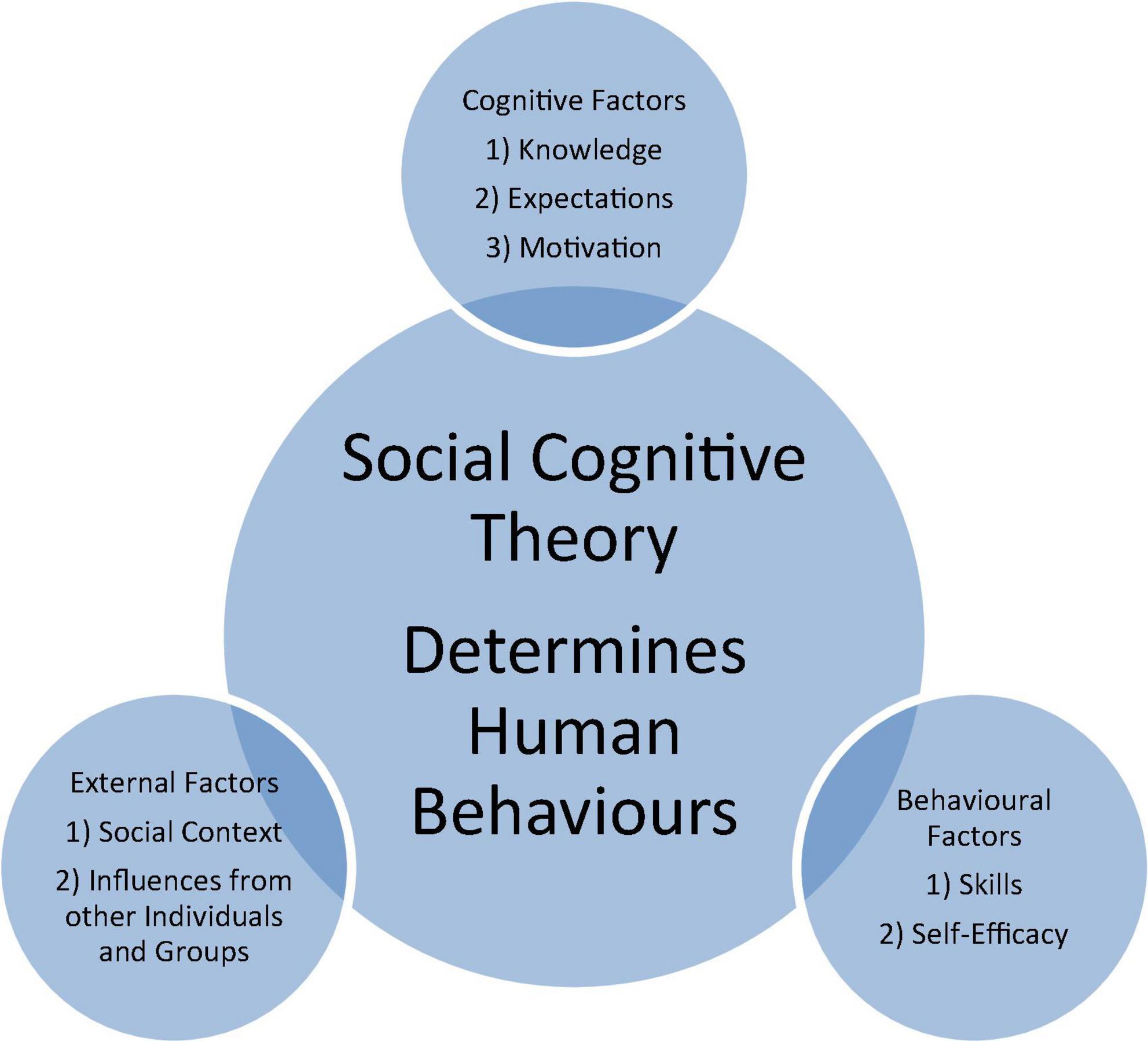

Social cognitive theory is one of the theories of individuals’ learning behaviors and developments. It (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992) argues that learning behaviors occur in a social context through the interactions between people, social environments, and the behaviors of other individuals and groups. Learning cannot be separated from other human beings as individuals and groups gain new insights and knowledge based on other people’s behaviors and sharing. In other words, the social influences of and interactions with other individuals and groups play significant roles in learners’ internal and external social reinforcement (de Guerrero and Villamil, 1994).

In addition to the influences of other individuals and groups, learners’ own experiences, understanding, and personal beliefs also play significant roles in their cognitive development and learning behaviors. Bandura (1986, 1988, 1992) argued that learners’ previous experiences and understanding can impact reinforcements, expectations, and expectancies, which can reshape learners’ learning motivations, engagements, and behaviors and their expectations of the outcome of courses and qualifications (Yunus et al., 2021). Figure 1 outlines the social cognitive theory.

Figure 1. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992).

Social cognitive theory and language learning

Social interactions with peers, teachers, and social backgrounds play a significant role in second language acquisition (de Guerrero and Villamil, 1994). Bandura (1986, 1988, 1992) argued that individuals and groups usually learn new knowledge and practices based on the behaviors and models of peers, instructors, social context, and social environmental factors. Learning is not an isolated process; individuals cannot gain knowledge without models and practice. In foreign language learning, language learners can gain understanding and improve their proficiency and knowledge based on their experiences and interactive teaching and learning materials (Sun and Gao, 2020).

Hellermann (2018) has argued that cultural heritage buildings could be positive examples in foreign language teaching classroom environments. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992), individuals and groups can learn language knowledge using cultural heritage buildings with targeted language materials. Beyond the traditional textbook materials, the contemporary cultural heritage building in the local environment significantly increases interest, learning motivation, and the sense of SDGs (Koukopoulos and Koukopoulos, 2018).

The relationship between cultural heritage, buildings, and learning

The discussion on cultural heritage buildings is currently centered on their relationship with sustainable development, specifically SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) (Xiao et al., 2018). For example, Harun (2011) and Adetunji et al. (2018) have probed into how conservation can be done, and focused on economic development related to tourism, while Jiménez Pérez et al. (2010) and Ott and Pozzi (2011) have related the possibilities of using heritage buildings to achieve SDGs, whereby attaining the goal of quality education (SDG4) of rising cultural awareness on the diverse cultures in this globalized era.

Among the studies about utilizing cultural heritage buildings to achieve myriad educational purposes, the scholars generally agree on the benefits of such incorporation (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2010; Harun, 2011; Ott and Pozzi, 2011; Castro-Calviño et al., 2020). For instance, Harun (2011) and Castro-Calviño et al. (2020) have recognized the benefits of including cultural heritage and buildings in teaching owing to the symbolic meaning of cultural identity, which allows people to relate to their predecessors, channeling a stronger link with their present community, and realize the value of history. This aligns with the target of SDG 4, quality education raising awareness of global citizenship and cultural diversity, thereby allowing learners to experience different national traditions and different ways of life in the age of globalization (Hollings, 2020).

Traditionally, the teaching of cultural heritage and buildings was done face-to-face only in classroom lessons with printed texts and images (Ott and Pozzi, 2011; Adetunji et al., 2018). With the advances of information and communication technology (ICT), some teachers have opted for gamification, virtual reality, augmented reality and software like Google Earth to provide simulation and inclusive experience of historical events (Konstantinov et al., 2018; Castro-Calviño et al., 2020). Through first-person experience and experiential learning, students are able to boost their motivation and improve their understanding of inequality, social justice and the causes of poverty, provoking reflection on relevant local and global issues (Adetunji et al., 2018; Konstantinov et al., 2018; Huish, 2021). The effectiveness of teaching has been boosted due to an increase in knowledge, cultural awareness and motivation of learners. Notably, with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Huish (2021) suggested that virtual learning spaces can overcome the restrictions of the traditional classroom in adopting new policies and promoting Students’ activism and promotion of global citizenship. Therefore, it can be seen from the current literature that incorporating digitized cultural heritage buildings has the potential to achieve the benefits of SDG 4 (quality education) in terms of raising awareness of cultural diversity and global citizenship.

Although previous studies (Adetunji et al., 2018; Konstantinov et al., 2018) have made significant contributions to identifying the benefits of incorporating cultural heritage, buildings, and sense of SDGs into education and the potential of using ICT in such teaching, there are still a few gaps in the literature. First, most studies have not focused on the prolonged implementation of materials involving heritage buildings in K-12 school settings. For example, some (Castro-Calviño et al., 2020; Karyoto et al., 2020) have focused on the effectiveness and possibility of including short-term educational programs on-site, such as at festivals and museums. Others (Embaby, 2014; Konstantinov et al., 2018) have focused on highly specialized professional areas in higher education, like building services and architecture. The discussion is centered around the conservation and preservation of cultural heritage buildings, but not the long-term impact on learners (Embaby, 2014). One of the criteria of a quality education is that it endows students with an appreciation of cultural diversity and global citizenship, reflected in the transformation of their values, beliefs and attitudes, and that it encourages their sustained efforts and commitment to be an active change-maker (Estepa Giménez et al., 2008; Biasutti and Frate, 2017). Although benefits of teaching about heritage buildings have been suggested, it is not yet known whether they have a sustainable impact on learners’ understanding of cultural and global issues.

Second, although the benefits of incorporating heritage buildings into education are mentioned in the literature, cultural heritage buildings mostly serve as the backdrop in teaching materials. For example, cultural heritage and buildings appear as 3D objects in interactive maps to provide historical background (Ott and Pozzi, 2011; Konstantinov et al., 2018), or in discussion threads in forums or social media such as Instagram or Facebook (Adetunji et al., 2018). Although scholars (Jiménez and Rose, 2010; Castro-Calviño et al., 2020) suggest that there is rising interest in the purposes, contents and pedagogies of teaching on heritage buildings, further effort is needed to investigate the holistic integration of cultural heritage buildings into the formal school setting, both the curriculum and classroom teaching. For example, although scholars (Adetunji et al., 2018; Konstantinov et al., 2018) have suggested that such a backdrop can provoke deeper reflection on the facts, the actual strategies used to achieve the specific learning outcomes in the curriculum and the way that teaching contents facilitate Students’ reflection on cultural practices, challenging assumptions about humanity, war and death, remain obscure.

Third, descriptions of heritage buildings can be seen everywhere in articles and literature; however, very few studies have examined how such elements could be implemented in K-12 language teaching and linked to sustainable development. Although language is perceived as a powerful tool to present and reflect upon culture, community membership and global citizenship (Wong and Xiao, 2010), very few studies (Guo et al., 2020; Kwee, 2021) have focused on the successful attainment of SDG 4 in the context of language teaching and learning. The attainment of SDGs needs transdisciplinary effort via collaboration among various key learning areas (Biasutti and Frate, 2017; Biasutti et al., 2018). Digitized cultural buildings are incorporated mostly into social sciences classes (Ott and Pozzi, 2011; Van Doorsselaere, 2021). Without knowing how the incorporation of digitized cultural heritage buildings into language classrooms is actually implemented, it is hard to evaluate its effectiveness within an interdisciplinary approach to education.

The current research gaps indicate that there is a need of further investigation into how cultural heritage buildings are incorporated into language teaching on online and blended learning platforms. It is also important to understand what strategies have been adopted to boost Students’ self-efficacy in understanding and to motivate them to engage in the development of global citizenship and awareness of cultural diversity. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the Students’ learning experiences to identify the specific cognitive, environmental and behavioral factors contributing to the successful implementation of digitized heritage buildings in language classrooms. Without such knowledge, it is difficult to devise effective strategies and drive efforts from various disciplines to attain the SDG quality education target by 2030.

Methodology

Research design

A case study approach (Yin, 2012) was employed to capture data from three ESL courses at a community college in the United States. Since incorporating heritage buildings in ESL courses is an innovative approach in the field, a qualitative case study design is beneficial in generating rich and in-depth data in understanding such phenomenon. First, a case study approach is useful to allow the researchers to gain a holistic view of the learning process by asking a series of “how” and “why” questions (Meyer, 2001). In this study, the community college selected is an information-rich case as the ESL department specifically discussed and designed the curriculum, activities and course materials with the incorporation of cultural heritage buildings (Creswell, 2012). Second, while examining ESL Students’ learning experiences with the incorporation of heritage buildings, the researchers could capture the lived experiences in a natural and real-life context (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2012). Third, case study is appropriate to investigate the critical factors contributing to a system of beliefs and actions of individuals (Tellis, 1997). Unlike the traditional ESL courses, which mainly focus on language proficiency and second language acquisition, the current case study and ESL courses employed a series of SDGs learning elements in the English language curriculum and instruction. In this way, the learners could build up their language proficiency at the same time as a sense of SDGs during their academic journey, particularly among international students. Through employing a qualitative case study design, the researchers were able to explore the processes, activities and events in Students’ blended learning from this information-rich case (Creswell, 2012).

Recruitment and participants

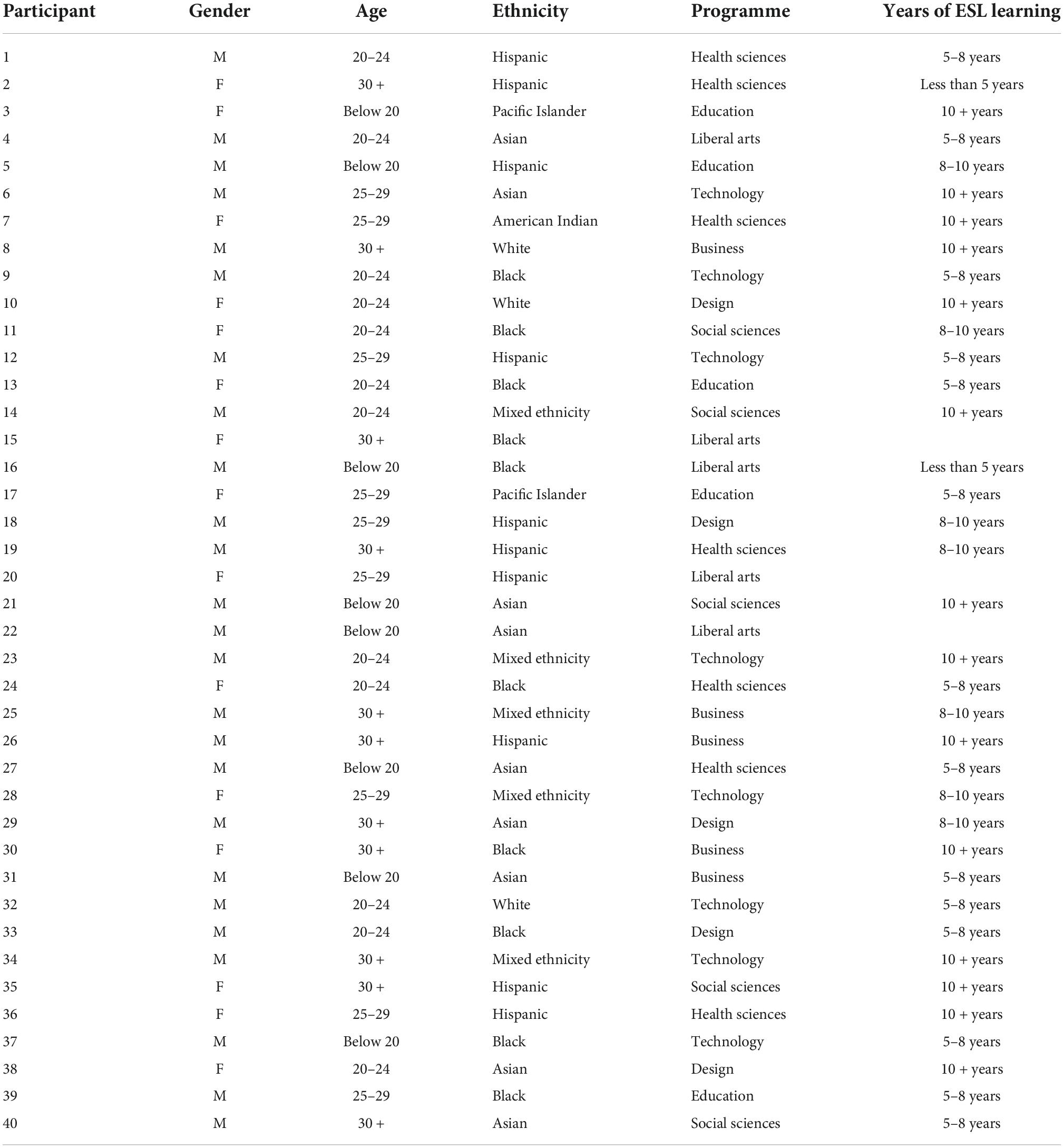

Forty ESL learners who joined the current blended ESL course with the elements of cultural heritage, building, and SDGs were the participants of this study. All the participants have to be enrolled in the blended ESL course with the elements of cultural heritage, building, and SDGs throughout the semester. Upon finishing the course, the ESL department assisted the researchers in sending out email invitations to students to participate in the research. The research purpose, procedures, data collection methods, expected time of commitment and potential risks were clearly outlined to the participant (Merriam, 2009; Creswell, 2012). Upon receiving the agreement from the potential participant, the consent form was then sent to each participant to read and sign prior the start of data collection (Merriam, 2009; Creswell, 2012). This sample of the participants represents a cross-section of the ESL learners in American community colleges in general (Lavrakas, 2011). Table 1 captures the demography of the participants.

Data collection

Qualitative tools were employed to collect multiple sources of data from the participants to ensure the trustworthiness of the study (Patton, 2002; Creswell, 2012). Three tools were used: (1) two one-on-one online semi-structured interview sessions (Merriam, 2009), (2) one focus group activities (Morgan, 1998), (3) remarkable item sharing (Creswell, 2012).

First, in the semi-structured interview sessions, the participants shared their experiences of the blended model ESL course, particularly about the relationship between cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs in the English language learning background. To ensure the participants would not withhold the most important yet confidential lived experiences, the researchers allowed the participants to choose a place where they were the most comfortable with to conduct the online interviews (Seidman, 2013). The researchers also paid extra attention to the video and audio quality to ensure the participants’ voices, facial expressions and the body gestures could be captured (Janghorban et al., 2014; Hai-Jew, 2015). As a result, each interview session lasted 49–72 min. They were recorded, transcribed and sent for member-checking prior to the start of data analysis (Creswell, 2012).

After all participants had shared their experiences and stories from the semi-structured interview sessions, all participants were invited to join the focus group activities. As there were 40 participants in the study, four focus group activities were formed (i.e., 10 participants per group). The focus group activities lasted 35–60 min, whereby participants were invited to discuss and share their experiences, opinions and feedback about the ESL course incorporated with the cultural heritage elements. Same as the semi-structured interviews, the recordings were transcribed and sent for member-checking (Creswell, 2012).

Data analysis

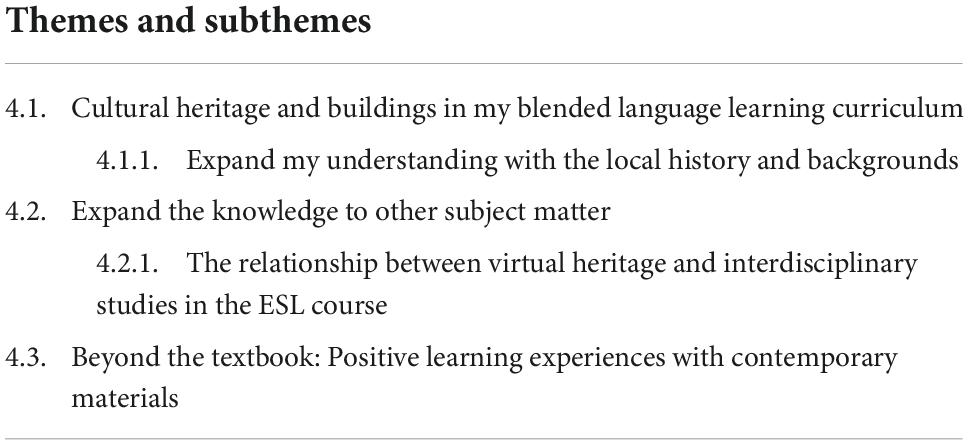

After data collection, a two-step data analysis procedure were employed (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Creswell, 2012). First, the researchers transcribed the oral conversations to written transcripts. The researchers re-visited the data multiple times in order to find out the relationships and the gist of the current issue (Merriam, 2009; Creswell, 2012; Alase, 2017). Then, a general inductive approach was adopted to reduce large chunk of data into meaningful themes and subthemes with the guidance of the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992). The researchers employed the open-coding step to narrow the large-sized data to the first-level themes and subthemes, whereby 11 themes and 17 subthemes were generated. Afterward, the researchers employed the axial-coding step to reduce the number of themes and subthemes by categorizing the open-coding results for further developments and studies (Merriam, 2009; Yin, 2009). Also, some participants also provided pictures of their remarkable items. The images were also studied as additional supporting evidence to their perceptions of the learning experiences, thereby enhancing the trustworthiness of the study (Merriam, 2009; Yin, 2009). As a result, three themes and two subthemes were categorized.

Human subject protection

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved and supported by Woosong University Academic Research Funding Department 2022. The study was supported by Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2022.

Findings and discussion

The ESL learners were all international students who had come to the United States for their higher education. Therefore, many had little understanding of the tangible buildings and heritage in North America. The participants indicated that the curriculum and teaching and learning materials relating to heritage buildings and SDGs significantly increased their learning motivation and understanding of SDGs via English language learning acquisition. Table 2 outlines the themes and subthemes of the data. The researchers combined the findings and discussions together into a single chapter for the report, thereby permitting a gaze into the correlation between evidence and findings more clearly (Anderson, 2010; Okamura and Miller, 2010).

Cultural heritage and buildings in my blended language learning curriculum

…our English courses is not very traditional…it is a nice ESL course…but our teacher added many sustainability and historical backgrounds…and American buildings…to our exercises…videos…and materials…I can see the cultural heritage…and American cultures…in our ESL course…we learnt multiple ideas and backgrounds in the same English environment…(Participant #35, Interview).

…I don’t like the traditional general English courses…the current English class has a lot of cultural ideas and buildings…and cultural heritage in our curriculum…and exercises…we need to do a lot of internet search…in order to complete the exercises…but we can learn a lot of American history and culture…from this English class…(Participant #3, Focus Group).

Traditionally, ESL and general English language courses usually focus on overall language proficiency and development, regardless of the instruction mode (on-campus, blended, online) (Wei, 2012). This general perspective may meet the needs of readers from international sites and locations as publishers design textbooks for international English language learners in different countries and regions (Byrd, 2001). Some students and teachers argue that the orientation of the textbooks and materials did not fit the needs of learners in their countries and regions. More importantly, college-level learners cannot gain additional knowledge beyond language acquisition from the traditional ESL curriculum.

Recently, some scholars (Gordon Ginzburg, 2019; Joung, 2021) argued that English language courses and teaching materials should employ special topics in order to motivate foreign language learners. For example, the South Korean government and educational institutions incorporated speeches and songs by popular Korean singers and TV stars into their language learning textbooks and curriculum (Joung, 2021). In Israel, letter writing has also incorporated in the intercultural classroom to allow reflect during the Students’ assimilation to a new culture (Gordon Ginzburg, 2019). Based on this idea, the researchers captured the following stories:

…I want to see some interesting facts and ideas from the English language course…cultural heritage and nice buildings all across the United States…increased my learning interests and motivations…I love to have these textbooks…I don’t want to go back to the general English textbooks without any American buildings and cultural understanding…(Participant #5, Interview).

From the perspective of the blended learning model, online lessons also offered positive learning experiences:

…our teachers also asked us to search some quick information from our computer…the blended learning model…in front of our computer…helped us to enjoy the flexibilities between the real situation and background and online learning experiences…we used the real materials from our community…and the videos are contemporary…in the United States with real building and cultural heritage…we also needed to do exercises and projects…with real cultural heritage with online learning mode…(Participant #16, Interview).

This study reflected that incorporating the cultural heritage building in a blend ESL courses can provide visual stimulation and greater possibility to engage in reflection in social issues in the real-world context (Dos Santos, 2019; Ben-Eliyahu, 2021). These provided the proximal contextual support to foster the learners’ sense of satisfaction in learning (Deci and Ryan, 2008). As a result, the positive affections generated in the learning process has become the Students’ source of self-efficacy, boosting their motivation in ESL learning (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992).

Expanding my understanding with local history and backgrounds

…while I was learning my ESL course, my teacher showed me pictures and videos of Liberty Bell [a Grade I historic building]. Then we read the story about the independence of the United States [a famous historical fact and cultural heritage of the American history]…I understood more about the cultural implication of American history…and of course the nostalgia of that postcolonial spirit…Even I was born after the independency…I understood the Old American heritage pretty well…(Participant #8, Interview).

Before the participants came to the United States, many had no understanding of the country’s history or culture and had no experience of blended learning experiences in any subject. As all were planning to complete their general education requirements and transfer to a senior university for their bachelor’s degree, they needed to complete a series of American history and cultural courses (a general education requirement) to obtain their associate degree (Starobin et al., 2016; List and Nadasen, 2017). Such requirement, coupled with their status as international students, created a challenge in their experiences of integration, generating stress and anxiety to both their learning environment and adaptation to the new cultures (Waasdorp et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2020). For the international students whose native language is not English, this could add further stress to their learning with an increase in worry in the possibilities of influencing their academic achievement (Peirce, 1995; Benson, 2019). All the participants thus indicated that their ESL course incorporating American history, cultural backgrounds, and SDGs increased their overall knowledge, boosted their motivation to learn, and interest as American community college students. The researchers captured the following:

…as an American college student…I need to learn some American history…but I could not take it now…before I finished the ESL courses…but I can learn some cultures and historical backgrounds in this ESL course…the curriculum design is excellent…(Participant #18, Interview).

…I really love the ideas of the sustainability goals…cultural heritage…American historical buildings…in our ESL course…I love history…and I want to learn American history and culture…because it will open my mind about the American people and background…we can learn different ideas in this ESL course…not only English…but also other cultural heritage…(Participant #28, Focus Group).

Furthermore, the blended learning model allowed the participants to conduct research using their computers in their rooms. Some assignments also required them to present their project from the live lesson during the blended classes. Many participants spoke about their presentations and projects on technological developments in the United States:

…iPhone and Apple computers are developed in the United States…our professor asked us to finish our presentation about the relationship between cultural heritage and technology…during the blended live lessons…students will bring the presentation back to the in-person classes 2 days later…we also needed to do a project about the cultural building based on the SDGs…I am glad that we learnt multiple knowledge in the ESL class…(Participant #38, Interview).

The blended learning approach applying cultural heritage, buildings, and SDGs in the ESL classroom environment significantly improved the learning experiences of the participants. According to the thoughts shared by the participants, the experiences were positive and the current teaching and learning strategies improved outcomes and achievements. This was reflected in their contentment engagement in activities (Reeves, 2000; Dungus, 2013). Apart from the sense of fulfillment in skill development, the participants also indicated that the abovementioned elements in their ESL curriculum greatly increased their understanding of local history and context as international students in the United States, reflecting the attainment of the learning outcomes. In line with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992), social context and environment play significant roles in learners’ knowledge development and second language acquisition (de Guerrero and Villamil, 1994; Pavlova and Vtorushina, 2018).

Expanding the knowledge to other subjects

Critical thinking, interdisciplinary background, and intercultural communication are three of the key factors for the success of post-secondary degree learners (Terenzini et al., 1996; Spector and Infante, 2020). In other words, associate degree learners should attain or experience these key factors during their academic journey. Although the participants had to complete courses in different subjects, such as ESL, history, ethics, philosophy, etc., each course should have connections and a common core (Al Salami et al., 2017). The participants indicated that the community college invited guest speakers or guest lectures to join their ESL classes for interdisciplinary sharing: professionals with different backgrounds and knowledge bases were invited to share their ideas in the ESL classroom environment. The researcher captured the following:

…the college invited the government official who provides services about the SDGs and local cultural heritage…and historical promotion…we learnt a lot of new ideas about the American culture…and the historical buildings and facts…from the guest speaker…(Participant #31, Interview).

While engaging learners into conversations and dialogues through questions and presentations, the ESL learners were able to acquire new knowledge and higher-order thinking skills such as critical thinking and multi-perspective thinking. Such skills were deemed essential in improving the proficiencies of language learning (Ellis, 2000; Hyland, 2007). Moreover, by integrating global issues in such a creative ESL classroom, students were able to further develop higher-order thinking skills such as critical thinking and system thinking, which is considered as essential in this era of education (Eli et al., 2020). Some participants expressed their thoughts about multiple online field trips to local history museums in their community during classes (Kamen and Leri, 2019). Beyond the online live lessons, the field trips during the in-person classes played a significant role in building up their sense of SDGs and cultural understanding because the interactive learning modes increased their learning motivation, interest, and language proficiency from the social learning (cognitive) background (Wright, 2017; Güntaş et al., 2021). Two said:

…during our classes…the online tour guide from the history museum taught us a lot of interesting facts in the United States…and the local community…there are also many catalogs and booklets for ESL learners…who only have second language proficiency… (Participant #1, Focus Group).

…the blended learning is not only online classes…we have the in-person meeting on Friday…the online field trip to the history museums…helped us to understand the history, the cultural heritage and building in the state and country…there were figures and pictures…with basic and simple English…ESL students could understand that…it is good to learn at least two knowledge and subjects in the same ESL course…(Participant #13, Interview).

From the sharing of the participants, it is evident that the incorporation of cultural heritage buildings in their ESL learning correlated directly to the attainment of performance outcomes, like the development of the higher-order thinking skills and the acquisition of local knowledge. The positive experiences brought by both virtual and in-person tours yielded higher self-efficacy in adopting and continuing such mode of learning in future, reflecting that such element can yield to the success in boosting the Students’ ESL learning to boost the learners’ motivation in future (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992).

The relationship between virtual heritage and interdisciplinary studies in the English-as-a-second language course

Computer-aided language teaching and technologically assisted teaching and learning approaches (Johnson, 2002; Levy and Stockwell, 2006; Gok et al., 2021) are useful strategies for contemporary learners, particularly in the blended ESL language learning environment. Besides the audio recordings and videos among the textbook materials, Wang et al. (2020) have also argued that the 3D learning experiences increase the motivation and interest of learners. Relating to virtual heritage learning in the participants’ ESL course, the researchers captured:

…Virtual heritage building is not a gimmick. Some of my friends think it is something just pleasing the “big bosses” [the authorities] to have some SDGs or elements of sustainability there. In fact, I think heritage building is a part in our culture. When we are learning about Daoist belief, my teacher gave us a VR headset and showed us the Temple in Chinatown…Then I know more about how the Chinatown transformed into a hub of local Chinese…During the multimodal presentation, I discussed the racial tension in between and our colonial past. I feel pretty good…(Participant #4, Interview).

The First Transcontinental Railroad or Pacific Railroad was a milestone in American history. Although community college students learn this history in their American History courses, the current curriculum successfully combined history, cultural heritage, and SDGs into the ESL courses (Kaur, 2013; Dhawan, 2020). Virtual technology and social (cognitive) learning gave the participants a way into American history and cultural heritage in this blended ESL course (Levy and Stockwell, 2006). One interesting point was captured:

…the college gave us the VR classes…so we [students] could enjoy the virtual images and historical backgrounds for the First Transcontinental Railroad…it was excited…to see and learn the sharing from the video…we entered the building and learnt the cultural heritage…such as the worker’s house…in Iowa…and we walked from Iowa to California…in the virtual video…the SDGs ideas were excellent…and met…(Participant #14, Focus Group).

Many of the participants argued that the interdisciplinary knowledge made possible by the computer-aided language learning strategies significantly increased their interest in learning, motivation, language proficiency, and knowledge development in this blended ESL course. Scholars (Albashiry et al., 2015; Chaleta et al., 2021) have argued that the university curriculum should incorporate different learning achievements and outcomes, such as interdisciplinary knowledge and development. For example, many participants expressed that they “received the expected outcomes and achievements from the online field trips to the history museums” (Participant #10, Focus Group).

In line with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988, 1992), the elements of social context and social environment significantly boosted the second language acquisition and sense of SDGs among the participants on the blended ESL course (Wright, 2017; Güntaş et al., 2021). More importantly, many believed that the virtual and 3D experiences played significant roles in this (Peeters, 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Gok et al., 2021). Through this kind of personalized learning experiences, the learners are more motivated in learning as they believe they can recall and reuse both the knowledge and language in their later stages of life (Summers et al., 2005; Fedosejeva et al., 2018).

Beyond the textbook: Positive learning experiences with contemporary materials

A recent study (Joung, 2021) argued that foreign language textbooks and learning materials should incorporate contemporary knowledge and local culture to increase the interest and motivation of international learners who may not know anything about the context of the target language. More importantly, the local history and cultural heritage, in this case, in the United States, may further improve the language proficiency of learners due to the interdisciplinary background and culture of language learners (Leong, 2015). Almost all the participants favorably compared their current ESL course to their previous ESL courses in terms of contemporary materials. Two said:

…my previous English courses…only used the textbook…the textbook materials were boring and outdated…the textbook exercises talked about some ideas 20 years ago…the exercises were not interested…and no students wanted to learn with the old-fashioned pictures and sentences…also, I love the blended learning model…because we can make the balance between live lessons and in-person classes…(Participant #24, Interview).

…black and white…no pictures…CD and cassettes tapes…many schools continued to use these old-schooled items in their language courses…our current ESL course…real videos…go to the museum…field trip…guest speakers…real building and cultural heritage practice in front of us…very useful and contemporary…all students were excited…(Participant #25, Focus Group).

Some studies (Park, 2010; Leong, 2015; Moritoki, 2018) have argued that international students may need additional time to understand local history and culture. Although their experiences of living in local communities and the school environment increased their practical knowledge and skills, loneliness and alienation could have been reinforced due to the paucity of the cultural heritage knowledge of their new countries (Tu and Zhang, 2014; Olofsson et al., 2021). The incorporation of the local language, history and cultural heritage in the college curriculum could be beneficial to the international students to acclimatize and adapt to the new culture and environment (Fishman, 2001; Dewey et al., 2012; Taguchi et al., 2016). This study reflected that the blended learning model and the computer-aided teaching and learning approach (Levy and Stockwell, 2006; Dhawan, 2020) further helped the participants to learn about American cultural heritage and buildings in the internet environment:

…we all live in the United States…but no one taught us the local history and cultural practices…in the community-level and the national-level…all students wanted to learn more about the American culture and buildings…why American people build their buildings and establishments in this way…why buildings in Massachusetts are not the same as the buildings in California…our ESL courses have this knowledge…(Participant #6, Interview).

Many participants also indicated that the blended learning model and the computer-aided teaching and learning approach (Levy and Stockwell, 2006; Dhawan, 2020) allowed them access, in their own room, to materials beyond those made available by the textbook, teacher’s materials, and the designated classroom environment, particularly materials about cultural heritage, buildings, and historical knowledge used for language development. As one said,

…many ESL classes do not have the blended learning model…we could enjoy the materials with cultural heritage…American history…and American culture…in the blended learning model…I like that we can have 1.5 h in my own room…and the other 1.5. h in the classroom…sometimes with good field trip to the local community…we learnt a lot of knowledge of English language and cultural heritage and building…very good and we learnt a lot…(Participant #40, Interview).

Contemporary materials, computer-aided language learning and the blended learning model played significant roles in the participants’ learning experience. Many stated that the blended learning model allowed them to do research and complete for their presentations and projects online via their computer (Stadtlander et al., 2011). They might return to the in-person classroom environment every other class for peer-to-peer interactive activities.

Limitations and future research directions

First, this is a small-scale qualitative study with limited participants. Although 40 participants decided to join the ESL course with the elements of cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs, larger-sized population may be useful. As the blended ESL courses will continue, further studies can be conducted to understand the long-term developments of the learners.

Second, the current study only developed a series of teaching and learning materials in the ESL department at a community college in the United States. Other curriculum and materials in other subject matters, such as Spanish, French, and Japanese etc., may also apply these strategies for classroom instruction. Further research studies may conduct in other departments and subject matters.

Third, although blended model is one of the popular teaching and learning approaches in the classroom environments, many foreign language courses continue to offer in-person and face-to-face (only) instruction. Therefore, the current ESL course with the elements of cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs should be employed to the in-person and face-to-face (only) classroom environments. Researchers may further compare the outcomes and achievements between these two groups of students for a comprehensive study.

Conclusion

This study reflected that the ESL course and curriculum designs with the elements of cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs boosted Students’ motivation in learning both the languages and cultures, as evident in their positive experiences in the fields of second language acquisition, employments of the computer-aided and technologically assisted tools, and interdisciplinary knowledge. Colleges and universities are places where students gain their critical thinking, interdisciplinary backgrounds, and intercultural communication skills. As for international students, it is also an opportunity to sharpen their language skills and capacities to achieve their academic goals in the new countries. Thus, empowering international students with such knowledge, language and skills by engaging them in learning is crucial to determining the success of quality education in the post-pandemic era (Ahlburg, 2020; Kim et al., 2020). In the post-pandemic era, it is equally foreseeable that the number of international students will increase back to the pre-pandemic level (Thatcher et al., 2020). Universities and higher education institutes need to reconsider their curriculum to embrace such multiculturalism so as to provide quality education to enrolled students (Parker, 2012; Ahlburg, 2020). The findings of this study can be useful for the university leaders, department heads, curriculum developers, instructors, and trainers as a reference to reform and upgrade their current materials with cultural heritage, buildings, and senses of SDGs in order to offer the comprehensive training to college and university students.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Woosong University Academic Research Department and Funding. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adetunji, O. S., Essien, C., and Owolabi, O. S. (2018). eDIRICA: Digitizing Cultural Heritage for Learning, Creativity, and Inclusiveness. Berlin: Springer International Publishing, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-01762-0_39

Ahlburg, D. A. (2020). Covid-19 and UK Universities. Polit. Q. 91, 649–654. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12867

Al Salami, M. K., Makela, C. J., and de Miranda, M. A. (2017). Assessing changes in teachers’ attitudes toward interdisciplinary STEM teaching. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 27, 63–88. doi: 10.1007/s10798-015-9341-0

Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 5:9. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

Albashiry, N., Voogt, J., and Pieters, J. (2015). Curriculum design practices of a vocational community college in a developing context: Challenges and needs. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 39, 1137–1152. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2014.942894

Anderson, C. (2010). Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 74:141. doi: 10.5688/aj7408141

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1988). Organizational applications of social cognitive theory. Aust. J. Manag. 13, 275–302.

Bandura, A. (1992). “Social cognitive theory of social referencing,” in Social referencing and the social construction of reality in infancy, ed. S. Feinman (New York, NY: Plenum Press), 175–208.

Baticulon, R. E., Sy, J. J., Alberto, N. R. I., Baron, M. B. C., Mabulay, R. E. C., Rizada, L. G. T., et al. (2021). Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. Med. Sci. Educ. 31, 615–626. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01231-z

Bekteshi, E., and Xhaferi, B. (2020). Learning about sustainable development goals through English language teaching. Res. Soc. Sci. Technol. 5, 78–94. doi: 10.46303/ressat.05.03.4

Benson, A. (2019). Migrant teachers and classroom encounters: Processes of intercultural learning. London Rev. Educ. 17, 1–13. doi: 10.18546/LRE.17.1.01

Biasutti, M., and Frate, S. (2017). A validity and reliability study of the Attitudes toward Sustainable Development scale. Environ. Educ. Res. 23, 214–230. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2016.1146660

Biasutti, M., Makrakis, V., Concina, E., and Frate, S. (2018). Educating academic staff to reorient curricula in ESD. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 19, 179–196. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-11-2016-0214

Blake, J. (2000). On defining the cultural heritage. Int. Comp. Law Q. 49, 61–85. doi: 10.1017/S002058930006396X

Byrd, P. (2001). “Textbook: Evaluation for selection and analysis for implementation,” in Teaching English as a second or foreign language, (London: Thomson Learning Inc.), 415–427.

Castro-Calviño, L., Rodríguez-Medina, J., Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., and López-Facal, R. (2020). Patrimonializarte: A heritage education program based on new technologies and local heritage. Educ. Sci. 10:176. doi: 10.3390/educsci10070176

Chaleta, E., Saraiva, M., Leal, F., Fialho, I., and Borralho, A. (2021). Higher education and sustainable development goals (Sdg)—potential contribution of the undergraduate courses of the school of social sciences of the university of Évora. Sustainability 13, 1–10. doi: 10.3390/su13041828

Creswell, J. W. (2012). “Qualitative Research Narrative Structure,” in Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd Edn. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications)

de Guerrero, M. C. M., and Villamil, O. S. (1994). Social-cognitive dimensions of interaction in L2 Peer revision. Mod. Lang. J. 78, 484. doi: 10.2307/328586

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 49, 182–185. doi: 10.1037/a0012801

Dewey, D., Bown, J., and Eggett, D. (2012). Japanese language proficiency, social networking, and language use during study abroad: Learners’ perspectives. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 68, 111–137. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.68.2.111

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Dos Santos, L. M. (2019). English language learning for engineering students: Application of a visual-only video teaching strategy. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 21, 37–44.

Dungus, F. (2013). The effect of implementation of performance assessment, portfolio assessment and written assessments toward the improving of basic physics II learning achievement. J. Educ. Pract. 4, 111–117.

Eli, M, Scheie, E., Gabrielsen, A., Jordet, A., Misund, S., et al. (2020). Interdisciplinary primary school curriculum units for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 795–811. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2020.1750568

Ellis, R. (2000). Task-based research and language pedagogy. Lang. Teach. Res. 4, 193–220. doi: 10.1177/136216880000400302

Embaby, M. E. (2014). Heritage conservation and architectural education: “An educational methodology for design studios.”. HBRC J. 10, 339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.12.007

Estepa Giménez, J., Ruiz, R. M. Á, and Listán, M. F. (2008). Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions about heritage and heritage education: A comparative analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 2095–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.017

Fedosejeva, J., Boèe, A., Romanova, M., Iliško, D., and Ivanova, O. (2018). Education for Sustainable Development: The choice of pedagogical approaches and methods for the implementation of pedagogical tasks in the anthropocene age. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 20, 157–179. doi: 10.2478/jtes-2018-0010

Fishman, J. (2001). “300-plus years of hertiage language education in the United States,” in Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Language in Education: Theory and Practice, eds J. Peyton, D. Ranard, and S. McGinnis (Washington, D.C: Center for Applied Linguistics), 81–98.

Ghosh, R., and Jing, X. (2020). Fostering Global Citizenship Through Student Mobility. Beijing Int. Rev. Educ. 2, 553–570. doi: 10.1163/25902539-02040009

Gok, D., Bozoglan, H., and Bozoglan, B. (2021). Effects of online flipped classroom on foreign language classroom anxiety and reading anxiety. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1950191

Gordon Ginzburg, E. (2019). Letter Writing in the Intercultural Classroom: The Case of Retraining Courses for Immigrant English Teachers in Israel. Intercult. Educ. 30, 180–195. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2018.1538039

Güntaş, S., Gökbulut, B., and Güneyli, A. (2021). Assessment of the effectiveness of blended learning in foreign language teaching: Turkish language case. Laplage Em. Rev. 7, 468–484. doi: 10.24115/S2446-622020217Extra-B926p.468-484

Guo, S., Shin, H., and Shen, Q. (2020). The commodification of chinese in thailand’s linguistic market: A case study of how language education promotes social sustainability. Sustainability 12:7344. doi: 10.3390/SU12187344

Hai-Jew, S. (2015). Enhancing Qualitative and Mixed Methods Research with Technology. Hershey, PA: Business Science Reference, doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-6493-7

Harun, S. N. (2011). Heritage building conservation in Malaysia: Experience and challenges. Proc. Eng. 20, 41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.137

Hellermann, J. (2018). Languaging as competencing: Considering language learning as enactment. Classr. Discourse 9, 40–56. doi: 10.1080/19463014.2018.1433052

Hollings, S. (2020). COVID-19: The changing face of global citizenship and the rise of pandemic citizenship. Knowl. Cult. 8, 81–91. doi: 10.22381/KC83202012

Hu, Q., Liu, Q., and Wang, Z. (2022). Meaning in life as a mediator between interpersonal alienation and smartphone addiction in the context of Covid-19: A three-wave longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 127:107058. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107058

Huish, R. (2021). Global citizenship amid COVID-19: why climate change and a pandemic spell the end of international experiential learning. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 42, 441–458. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2020.1862071

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. J. Second Lang. Writ. 16, 148–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005

Iivari, N., Sharma, S., and Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life – How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? Int. J. Inf. Manage. 55:102183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

Janghorban, R., Roudsari, R. L., and Taghipour, A. (2014). Skype Interviewing: The New Generation of Online Synchronous Interview in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 9:10.3402/qhw.v9.24152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.24152

Jiménez Pérez, R., Cuenca López, J. M., Mario Ferreras, and Listán, D. (2010). Heritage education: Exploring the conceptions of teachers and administrators from the perspective of experimental and social science teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.01.005

Jiménez, R. T., and Rose, B. C. (2010). Knowing How to Know: Building Meaningful Relationships Through Instruction That Meets the Needs of Students Learning English. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 403–412. doi: 10.1177/0022487110375805

Johnson, E. (2002). The role of computer-supported discussion for language teacher education: What do the students say? CALICO J. 20, 59–79.

Joung, H. (2021). Korean-language textbook featuring BTS content being developed. Ministry of culture, sports and tourism and korean culture and information service. Available online at: https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Society/view?articleId=199402 (accessed October 6, 2021).

Kamen, E., and Leri, A. (2019). Promoting STEM persistence through an innovative field trip–based first-year experience course. J. Coll. Sci. Teach 49, 24–31.

Karyoto, K., Chasanah, N., Sisbiantoro, D., Setyawan, W., and Huda, M. (2020). Effectiveness Legal Formal of Education Culture Heritage at Van Den Bosch Fort in Indonesian. doi: 10.4108/eai.26-11-2019.2295169

Kaur, M. (2013). Blended learning: Its challenges and future. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 93, 612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.248

Kim, H., Krishnan, C., Law, J., and Rounsaville, T. (2020). COVID-19 and US higher education enrollment: Preparing leaders for fall. New York, NY: McKinsey Company, 1–10.

Konstantinov, O., Kovatcheva, E., and Palikova, N. (2018). “Gamification in Cultural and Historical Heritage Education,”. 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (Valencia). 1, 8443–8451. doi: 10.21125/inted.2018.2043

Koukopoulos, Z., and Koukopoulos, D. (2018). Evaluating the usability and the personal and social acceptance of a participatory digital platform for cultural heritage. Heritage 2, 1–26. doi: 10.3390/heritage2010001

Kwee, C. (2021). I want to teach sustainable development in my English classroom: A case study of incorporating sustainable development goals in English teaching. Sustainability 13:4195. doi: 10.3390/su13084195

Lavrakas, P. J. (ed.) (2011). “Purposive Sample,”. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods*. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. 645–647. doi: 10.4135/9781412963947

Leong, P. (2015). Coming to America: Assessing the patterns of acculturation, friendship formation, and the academic experiences of international students at a U.S. college. J. Int. Students 5, 459–474.

Levy, M., and Stockwell, G. (2006). CALL dimensions: Options and issues in computer-assisted language learning. New York, NY: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9780203708200

List, A., and Nadasen, D. (2017). Motivation and self-regulation in community college transfer students at a four-year online university. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 41, 842–866. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2016.1242096

Lowenthal, D. (2005). Natural and cultural heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 11, 81–92. doi: 10.1080/13527250500037088

Mendoza, R., Baldiris, S., and Fabregat, R. (2015). Framework to heritage education using emerging technologies. Proc. Comput. Sci. 75, 239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2015.12.244

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: a Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Morgan, D. (1998). The Focus Group Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, doi: 10.4135/9781483328164

Moritoki, N. (2018). Learner motivation and teaching aims of Japanese language instruction in Slovenia. Acta Linguist. Asiat. 8, 39–50. doi: 10.4312/ala.8.1.39-50

Okamura, Y., and Miller, J. (2010). Career Development Strategies for Japanese Immigrant Teachers. Aust. J. Career Dev. 19, 33–42. doi: 10.1177/103841621001900306

Olofsson, J., Rämgård, M., Sjögren-Forss, K., and Bramhagen, A. C. (2021). Older migrants’ experience of existential loneliness. Nurs. Ethics 28, 1183–1193. doi: 10.1177/0969733021994167

Ott, M., and Pozzi, F. (2011). Towards a new era for cultural heritage education: Discussing the role of ICT. Comput. Human Behav. 27, 1365–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.031

Park, H. (2010). The stranger that is welcomed: Female foreign students from Asia, the English language industry, and the ambivalence of ‘Asia rising’ in British Columbia, Canada. Gender Place Cult. 17, 337–355. doi: 10.1080/09663691003737603

Parker, L. D. (2012). From privatised to hybrid corporatised higher education: A global financial management discourse. Financ. Account. Manag. 28, 247–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0408.2012.00544.x

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd. Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, doi: 10.2307/330063

Pavlova, L., and Vtorushina, Y. (2018). Developing students’ cognition culture for successful foreign language learning. SHS Web Conf. 50:01128. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20185001128

Peeters, W. (2018). Applying the networking power of Web 2.0 to the foreign language classroom: A taxonomy of the online peer interaction process. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 31, 905–931. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1465982

Peirce, B. N. (1995). Social Identity, Investment, and Language Learning. Tesol Q. 29, 9–31. doi: 10.2307/3587803

Reeves, T. C. (2000). Alternative assessment approaches for online learning environments in higher education. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 23, 101–111. doi: 10.2190/GYMQ-78FA-WMTX-J06C

Seidman, I. (2013). “A structure for in-depth phenomenological interviewing,” in Interviewing as qualitative research. A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 15–27. doi: 10.1037/032390

Spector, A., and Infante, K. (2020). Community college field placement internships: Supervisors’ perspectives and recommendations. Soc. Work Educ. 39, 462–480. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2019.1654990

Stadtlander, L. M., Sickel, A., and Salter, D. (2011). Online doctoral student research and writing self-efficacy in a publishing internship. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 10, 78–89. doi: 10.18870/hlrc.v10i1.1170

Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research: Perspectives on practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Starobin, S., Smith, D., and Santos Laanan, F. (2016). Deconstructing the transfer student capital: Intersect between cultural and social capital among female transfer students in STEM fields. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 40, 1040–1057. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2016.1204964

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Summers, M., Childs, A., and Corney, G. (2005). Education for sustainable development in initial teacher training: Issues for interdisciplinary collaboration. Environ. Educ. Res. 11, 623–647. doi: 10.1080/13504620500169841

Sun, Y., and Gao, F. (2020). An investigation of the influence of intrinsic motivation on students’ intention to use mobile devices in language learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1181–1198. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09733-9

Taguchi, N., Xiao, F., and Li, S. (2016). Assessment of study abroad outcomes in Chinese as a second language: Gains in cross-cultural adaptability, language contact and proficiency. Intercult. Educ. 27, 600–614. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2016.1217126

Tellis, W. M. (1997). The Qualitative Report Application of a Case Study Methodology Application of a Case Study Methodology. Qual. Rep. 3, 1–19.

Terenzini, P., Springer, L., Yaeger, P., Pascarella, E., and Nora, A. (1996). First-generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Res. High. Educ. 37, 1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01680039

Thatcher, A., Zhang, M., Todoroski, H., Chau, A., Wang, J., and Liang, G. (2020). Predicting the Impact of COVID-19 on Australian Universities. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 13:188. doi: 10.3390/jrfm13090188

Tu, Y., and Zhang, S. (2014). Loneliness and subjective well-being among chinese undergraduates: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 124, 963–980. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0809-1

UNESCO/UNICEF, (2021). 5-year progress review on SDG 4 - Education 2030 in Asia-Pacific. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations [UN] (2020). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. New York, NY: United Nations.

Van Doorsselaere, J. (2021). Connecting sustainable development and heritage education? An analysis of the curriculum reform in flemish public secondary schools. Sustainability 13:1857. doi: 10.3390/su13041857

Waasdorp, T. E., Bradshaw, C. P., and Leaf, P. J. (2012). The Impact of Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on Bullying and Peer Rejection. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 166, 149–156. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.556785

Wan, H., Yan, L., and Gong, Y. (2020). “Two Major Factors that Lead to English Speaking Anxiety,” in 2020 3rd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences,(Paris) 661–665. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.201214.584

Wang, C., Lan, Y.-J., Tseng, W.-T., Lin, Y.-T. R., and Gupta, K. C.-L. (2020). On the effects of 3D virtual worlds in language learning: A meta-analysis. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 33, 891–915. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2019.1598444

Wang, T., Lin, C.-L., and Su, Y.-S. (2021). Continuance intention of university students and online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A modified expectation confirmation model perspective. Sustainability 13:4586. doi: 10.3390/su13084586

Wei, J. (2012). The chinese bouyei college students’ strategies for coping with classroom anxiety in foreign language learning: A survey study*. World J. English Lang. 2, 75–90. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v2n1p31

Winter, C. (2007). Education for sustainable development and the secondary curriculum in English schools: Rhetoric or reality? Camb. J. Educ. 37, 337–354. doi: 10.1080/03057640701546656

Wong, K., and Xiao, Y. (2010). Diversity and difference: Identity issues of chinese heritage language learners. Herit. Lang. J. 7, 314–348. doi: 10.46538/hlj.7.2.8

Wright, B. M. (2017). Blended learning: Student perception of face-to-face and online EFL lessons. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 7:64. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v7i1.6859

Xiao, W., Mills, J., Guidi, G., Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P., Gonizzi Barsanti, S., and González-Aguilera, D. (2018). Geoinformatics for the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage in support of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 142, 389–406. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2018.01.001

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and Methods, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, doi: 10.33524/cjar.v14i1.73

Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of Case Study Research, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Keywords: blended learning, building, case study, community college, cultural heritage, English as a second language (ESL), social cognitive theory, sustainable development goals

Citation: Kwee CTT and Dos Santos LM (2022) How can blended learning English-as-a-second-language courses incorporate with cultural heritage, building, and sense of sustainable development goals?: A case study. Front. Educ. 7:966803. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.966803

Received: 19 August 2022; Accepted: 28 September 2022;

Published: 17 October 2022.

Edited by:

Fahriye Altinay, Near East University, CyprusReviewed by:

Sitkiye Kuter, Eastern Mediterranean University, TurkeyRamesh Chander Sharma, Ambedkar University Delhi, India

Copyright © 2022 Kwee and Dos Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luis Miguel Dos Santos, bHVpc21pZ3VlbGRvc3NhbnRvc0B5YWhvby5jb20=

Ching Ting Tany Kwee

Ching Ting Tany Kwee Luis Miguel Dos Santos

Luis Miguel Dos Santos