- 1Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER), A Member of Intealth, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 2Health Professions Education Unit, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

Background: Given the significant gap in International Electives (IEs) opportunities for African health professions students, ECFMG|FAIMER through its Global Educational Exchange in Medicine and other health professions (GEMx) program launched a pilot African regional elective exchange program in 2016. During IEs, students have a choice of discipline they would like to learn, and the location, often at a host institution in a different country. This study provides an overview of health professional students’ experiences through participation in the pilot GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa.

Methods: This was a quasi-experimental, single-group post-test-only study using the survey method. Data were collected online using a self-administered survey through SurveyMonkey. Students (N = 107) received emails with a link to the survey as they completed the electives. The survey was open for a month for each student and weekly reminders were sent.

Results: The survey obtained a 100% response rate. All postgraduate and undergraduate students from various professional training programs (n = 107) reported gaining knowledge that was applicable back home. Over 43.4% (n = 46) reported having formed professional networks that are valuable for career progression. More than half 59.8% (n = 64) gained clinical skills and learned various procedures while 26.2% (n = 28) recognized the need for increased reliance on history taking for disease diagnosis. More than a third, 34.6% (n = 37) appreciated the different cultures and the effect of cultural beliefs on health outcomes.

Discussion and conclusions: The GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa provided a useful platform that enabled health professional students at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in their respective disciplines to gain enhanced perspectives on health issues, acquire clinical knowledge and skills applicable to their home country, strengthen personal and professional development, and develop positive attitude change in various health care delivery approaches.

1. Introduction

Growing global health partnerships and initiatives have led to a significant emphasis on internationalization in higher education policies in numerous health professional training institutions (Engel et al., 2015). Internationalization in higher education refers to the integration of international/ intercultural dimensions into all activities of a training institution, i.e., teaching, curricula, staff, and structural function [Organisation for Economic Co-operation (OECD), 2004]. International Electives (IEs) among others have served as a popular and critical platform to strengthen internationalization approaches in various health training institutions by enhancing global exposure for health professional trainees (Gribble and Dender, 2013). This has been achieved through more training opportunities in institutional bilateral and unilateral partnerships with diverse countries (Muir et al., 2016). The majority of these partnerships have been North (high-income countries) to South (low and middle-income countries) collaborations (Basu et al., 2017). As a result, more than half (59.0%) of the students at undergraduate and postgraduate levels especially in medicine and other professions from high-income countries move to low and middle-income countries to learn and get exposed to different health systems and disease burdens (Law et al., 2013; Centre for International Mobility CIMO, 2015).

There is some evidence that IEs have contributed significantly to transformative education experiences through the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, enhanced global perspective, and improved personal and professional development (Dowell and Merrylees, 2009; Eaton et al., 2011). Furthermore, IEs taken in low and middle-income countries provide ample opportunities for evidence-based global health advocacy in resource-limited settings (Loftus, 2013; Kumwenda et al., 2014).

Despite the added benefits of participating in IEs, not all students globally can take advantage of opportunities to enroll in these electives. Students coming from African nations are particularly disadvantaged due to the high costs of electives in high-income countries, lack of information about available opportunities, difficulty getting accepted by international programs, coupled with challenges in obtaining a visa to study abroad (Gribble and Dender, 2013). This has led to a mobility imbalance with scarcely any African students traveling for electives to high-income countries while African institutions are hosting many students from high-income countries (Eaton et al., 2011; Tsang, 2011; Daniels et al., 2020). Research has shown that South-to-South (between low and middle-income countries) regional partnerships have yielded fruitful outcomes in global health, especially in malaria, HIV care, and drug pricing (Muir et al., 2016). However, little is known about the feasibility and outcomes of the South-to-South (regional) model of hosting students and creating transformative education experiences via short-term electives for health professional training/learning in Africa.

Over the past 20 years, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER) have responded to a changing environment in global health professions education through FAIMER global faculty development programs and the creation of new models of student educational partnerships (ECFMG, 2019). FAIMER promotes excellence in global health professions education through programmatic and research activities and aims to be the trusted global authority on healthcare education as it moves into its next decade (FAIMER, 2021). On identifying a significant gap in IEs opportunities for African students, ECFMG through its Global Educational Exchanges in Medicine and the health professions (GEMx) program launched a regional elective exchange program promoting mobility within Africa in 2016 and had 107 students who participated in the pilot from 2017 to 2018 (GEMx, 2019). The undergraduate students who participated in the program were from medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and laboratory medicine disciplines. The postgraduate students were from the ophthalmology and pathology specialties.

This paper reports the learning experiences of health professional students’ participation in the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa. The research question that we aimed to answer was, “What are the experiences of health professional students’ participating in the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa?”

2. Materials and methods

2.1. GEMx regional elective exchange program description

The GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa utilized a multilateral approach to partnership that allowed reciprocity and elective diversity for participating institutions. A web-based application system based on the ECFMG Medical School Web Portal (EMSWP) was provided by ECFMG to enable the centralization of mobility and tracking applications. Mini-grants of $3,000 per institution were provided by ECFMG to defray costs for students. All institutions waived administrative fees to enable affordability. ECFMG developed a coordinating center based in Kampala, Uganda, that oversaw and support the development and implementation of the program. Specifically, this center worked with partner institutions in Africa to develop and implement a memorandum of understanding, oversaw grant funds distribution and accountability, elective curriculum, offered technical support and training on the web application system, supported each institution in budget development, assisted all students with preparations required by the host institution, provided information for visa application requirements, administered a post elective survey, and ensured each student submitted a participation report after participation. The duration of electives was about 4 weeks for undergraduate and 4 to 8 weeks for postgraduate students. For more details on the operational structure, the approaches, and lessons learned from the program see Nawagi et al. (2022).

GEMx partnered with five medical associations that encouraged their member institutions to participate in the program. These included the Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI), the Nursing Education Partnership Initiative (NEPI) which both later merged to form the African Forum for Research and Education in Health (AFREhealth), the College of Ophthalmology of East Central and Southern Africa (COECSA), the South-to-South initiative by the University of Dundee (Daniels et al., 2020), and the East African Health Professions Educators Association (EAHPEA).

2.2. Study design and measures

A single-group, post-test-only quasi-experimental, design using the survey method was used for this study. The research team developed a self-administered survey questionnaire based on the study objectives and a review of the literature to identify valid constructs for the population of interest. The questionnaire contained both close- and open-ended items. Besides student socio-demographics, the survey collected data about the student experience of the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa in the following areas: feedback on GEMx support and structure; obtaining academic credit at the home institution for program participation; activities students participated in, and student satisfaction with the host institution. The open-ended questions solicited in-depth detailed learning experiences and feedback from students (see Supplemental Material Appendix 1 for details of the questionnaire). Content and face validity of the tool was reviewed by senior ECFMG and FAIMER research team with expertise in measurement and survey research methodology. The Cronbach alpha was 0.72 for the tool.

2.3. Ethical considerations

Written and verbal informed consent was sought from every participant. Confidentiality was observed using study numbers and the data being password protected with access only to the research team. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Euclid University, School of Global Health, and Bioethics an intergovernmental and treaty-based institution under the United Nations Treaty Series 49006/49007 (Reference: IRB-2019-LTR-0705).

2.4. Study participants and data collection

Students who participated in the program were primarily in their clinical years of training in medicine, nursing, and pharmacy programs at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Immediately after completion of the elective, students were sent the post-elective survey using SurveyMonkey, an online platform widely used for data collection. Students were given 7 days to complete the survey with a follow-up reminder after a week to ensure their data were captured. Because students’ electives were taken at varying times, the time of survey administration varied and was on a rolling basis, depending on when each student completed their elective. The survey obtained a 100% response rate.

2.5. Data analysis

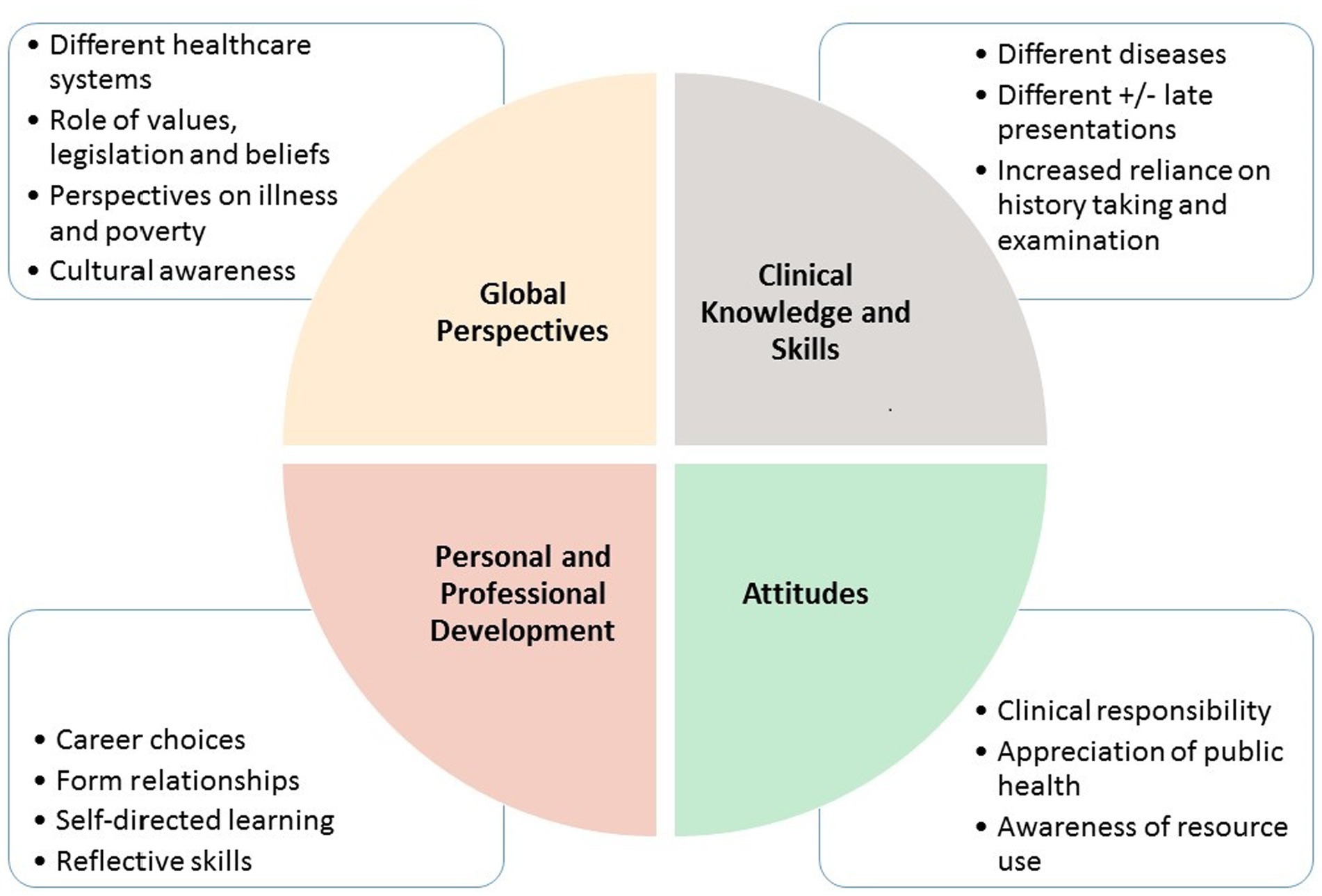

Univariate analysis was conducted using the SPSS IBM Statistic Version 21 statistical package. Descriptive statistics such as mean, median, interquartile ranges, and standard deviations (SD) were conducted for continuous variables. Frequency distribution and percentages were done for categorical variables. The learning experiences of students’ participation in the GEMx regional elective exchange placement were categorized into personal and professional development, clinical knowledge, global perspectives, and attitudes. Figure 1 shows the subcategories in each of the four terms used to report the student’s experiences. These were adapted from Dowell and Merrylees (2009) that attempted to define the experiences of health professional students, participating in International Medical Electives (IMEs) as values of participation in IMEs (Dowell and Merrylees, 2009).

Figure 1. Values used to categorize the students’ experiences as they participate in international electives for health professional students.

3. Results

Only those students who completed their electives in the program from January 2017 to December 2018 (2 years) and who provided informed consent were included in the study. Of the 108 students who enrolled in this program, only one student did not complete their elective while the rest of the 107 students completed their elective and gave consent, and therefore were included in this study.

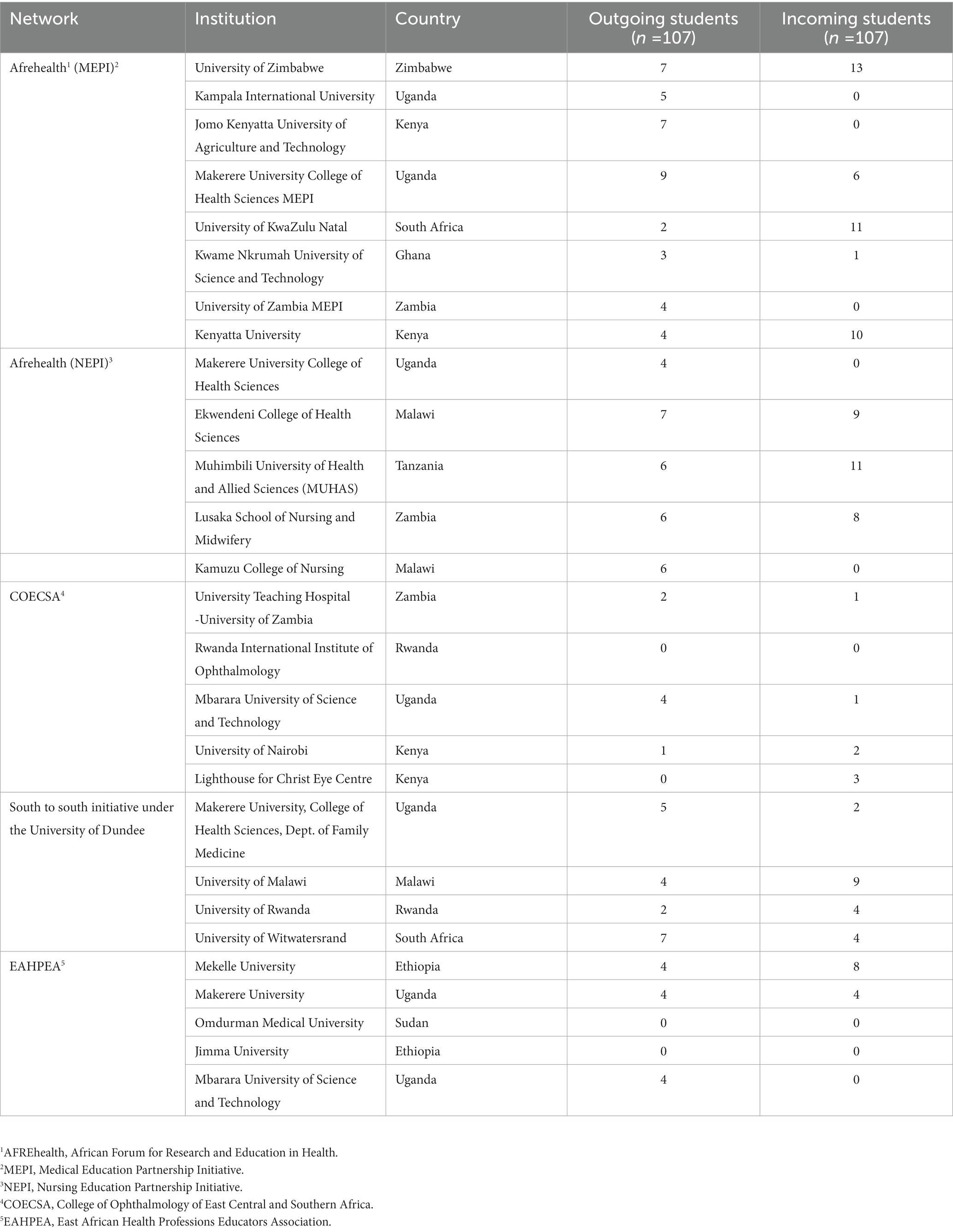

GEMx worked with a total of 27 institutions in five Institutional Network associations located in 11 African countries during the pilot of its regional elective exchange program in Africa for 2 years (2017–2018). Table 1 shows the distribution of incoming and outgoing students among these 27 institutions.

Table 1. Institutional networks with participating institutions location and distribution of student mobility during the pilot GEMx Africa regional elective exchange program (N = 107).

3.1. Participants characteristics

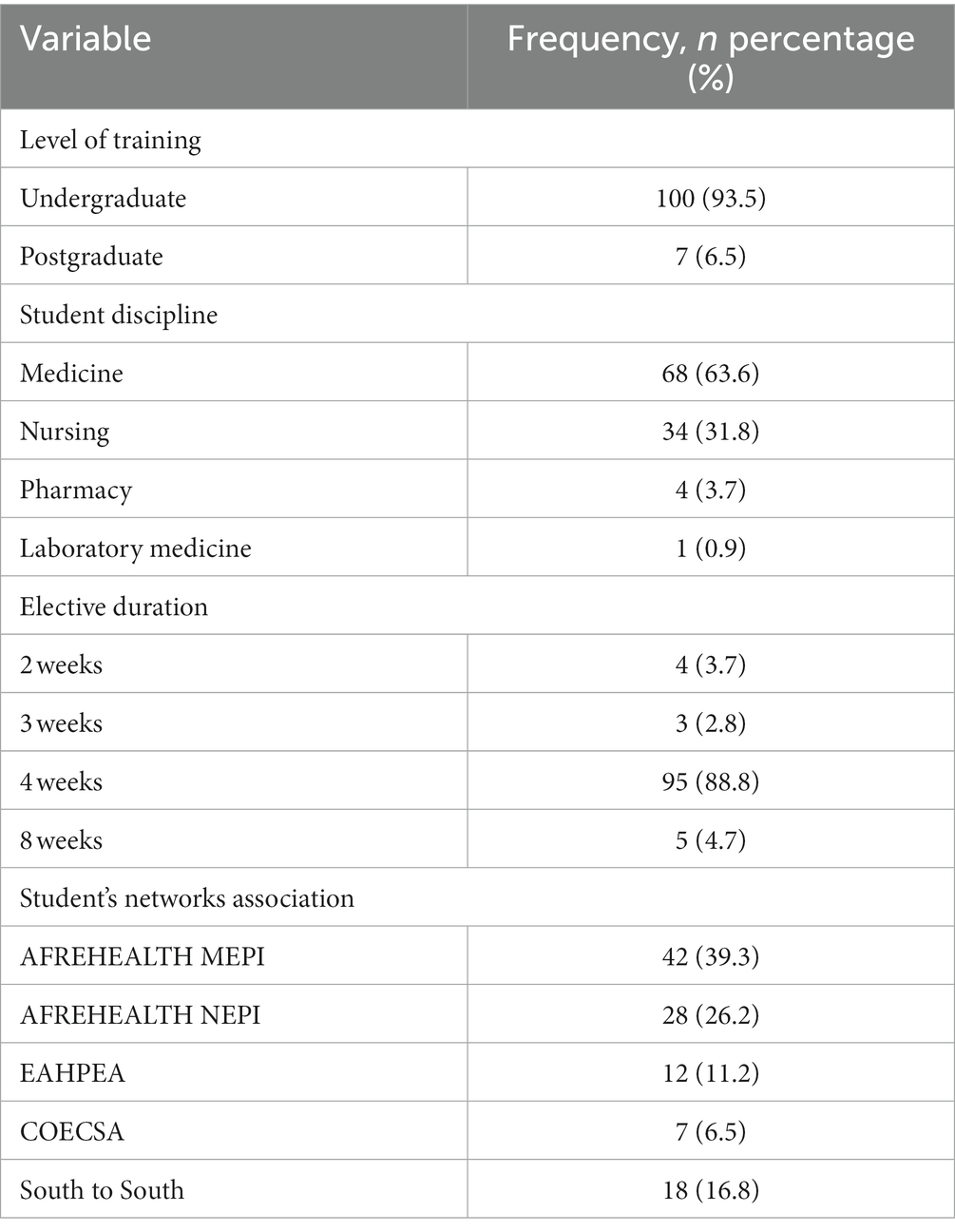

As shown in Table 2, below, the vast majority of students 93.5% (n = 100) were undergraduates and almost 89.0% (n = 95) took 4-week electives. Close to two-thirds of the students were from medicine 63.6% (n = 68) and close to a third from Nursing 34.0% (n = 34).

3.2. Elective specialties taken by students

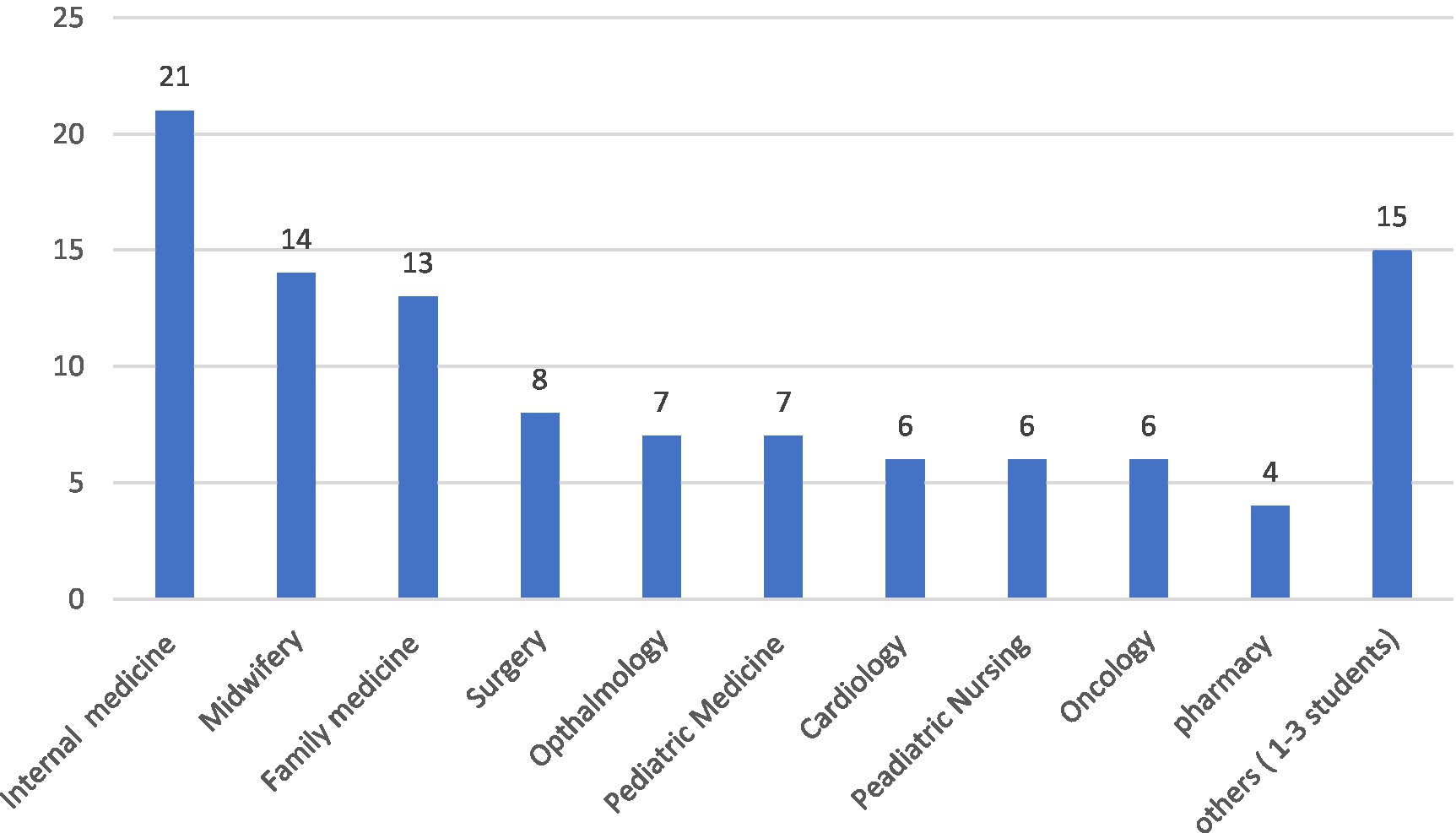

In total 18 elective specialties were offered and taken up by the students. As indicated in Figure 2, Internal Medicine (n = 21) was the most popular elective followed by midwifery (n = 14) and family medicine (n = 13). The specialties with lower participation rates (between 1 and 3 students) included medical nursing, theatre nursing, social medicine, emergency and trauma medicine, emergency, and trauma nursing, laboratory medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and critical care.

3.3. Learning activities the students participated in

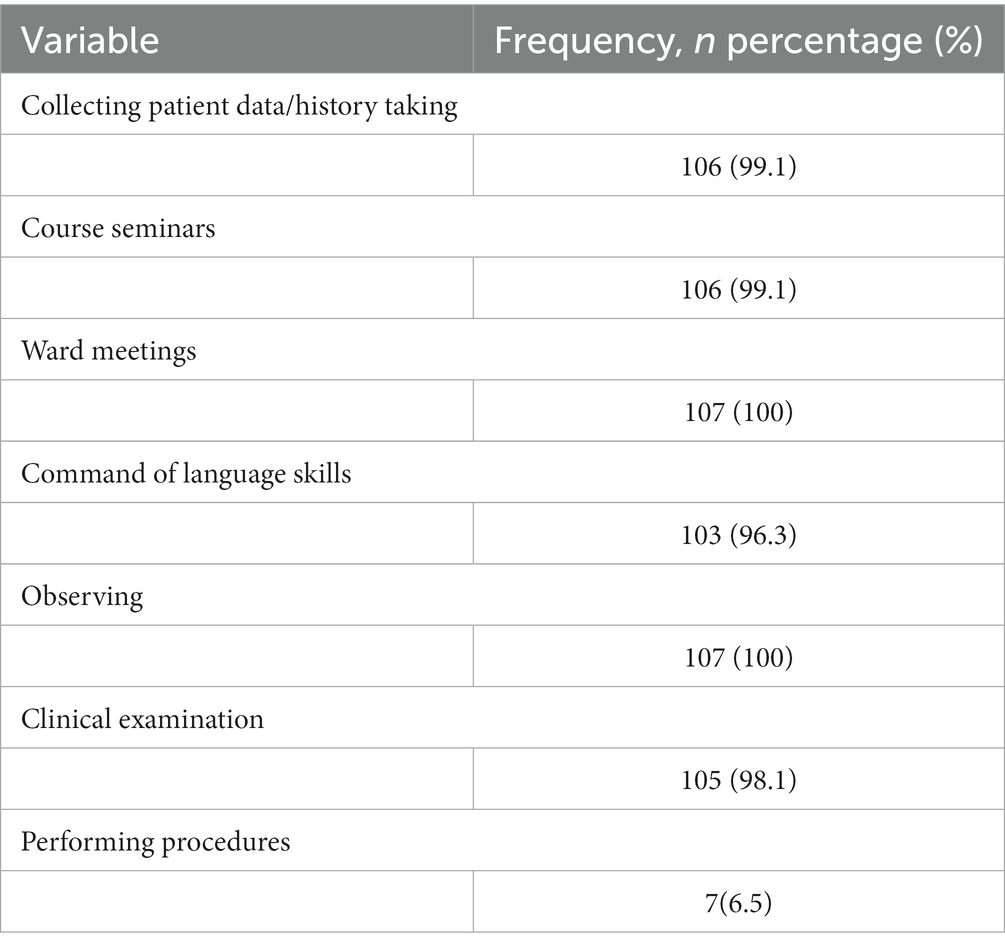

The various learning activities that the students participated in are shown in Table 3.

3.4. Students’ learning experiences in the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa

About 62.6% (n = 67) rated their experience to be 4 which meant good on a scale of 1–5. For the vast majority of students 98.1% (n = 105), it was their first time participating in IEs, and 95.5% (n = 102) agreed that they would not have had the opportunity without the GEMx regional elective exchange program. Only a little over a quarter of the students 28.0% (n = 30) earned a credit/grade for their elective placement. The mean cost of the electives per student was $1,275 (SD ± $1076) USD.

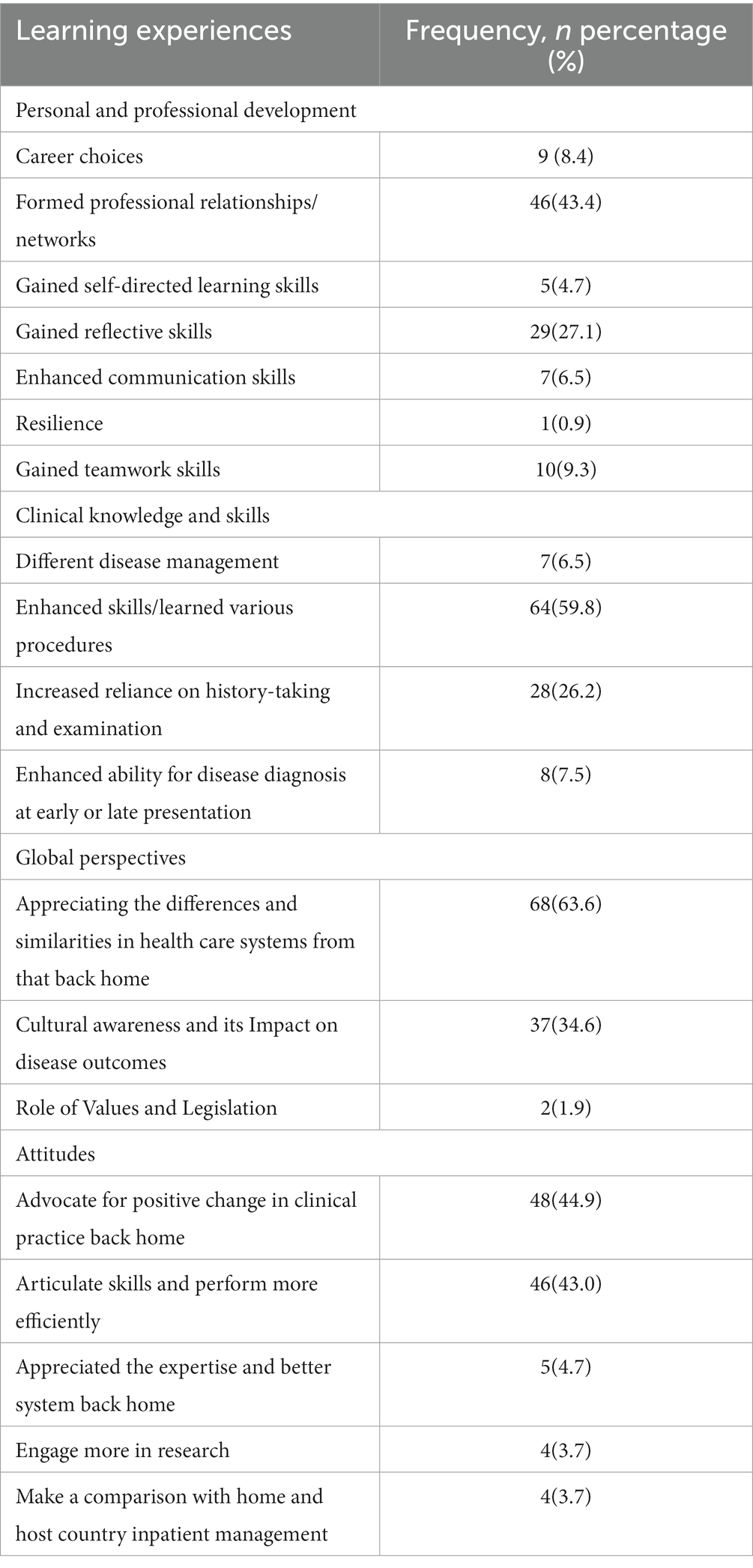

All students 107 (n = 100%) reported to have gained knowledge that they considered applicable in their home countries as shown in Table 4. Regarding personal and professional development, 43.4% (n = 46) of students reported to have formed valuable professional networks and relationships to advance their career paths. In the area of obtaining clinical knowledge and skills, almost 60.0% (n = 64) reported to have enhanced their clinical skills and learned various procedures and 26.2% (n = 28) expressed appreciation of the need for increased reliance on history-taking for a more accurate disease diagnosis. Close to two-thirds of the students, 63.6% (n = 68) recognized and appreciated the differences and similarities with healthcare systems in their home countries. More than a third of the students 34.6% (n = 37) realized the effect of culture on health outcomes. About 44.9% (n = 48) reported willingness to advocate for positive change in clinical practice in the specialties they were placed in their home countries.

Table 4. Students self-report of learning experiences in the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa (N = 107).

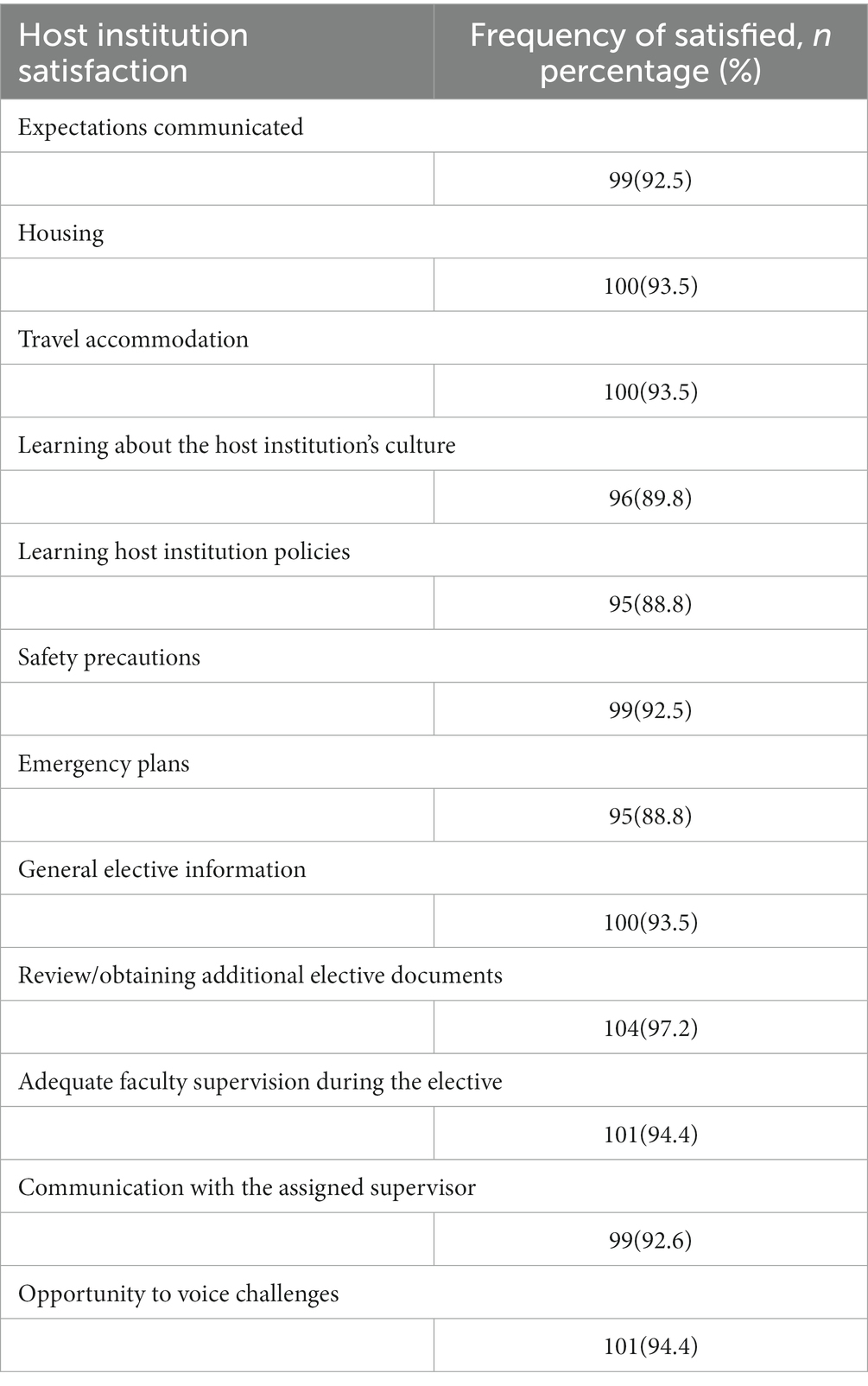

4. Students’ satisfaction with host institution during the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa

Students were asked to report on their satisfaction with their orientation and stay at the host institution (see Table 5). Options included very dissatisfied, dissatisfied, satisfied, and very satisfied. At the time of data analysis very dissatisfied and dissatisfied were categorized as dissatisfied while satisfied and very satisfied were categorized as satisfied. In general, responses were skewed in the direction of high satisfaction. Table 5 shows the distribution of satisfied participants in the various domains at the host institution.

Table 5. Student Satisfaction with Host Institution during Regional Elective Placement in Africa (N = 107).

5. Discussion

The GEMx regional elective exchange program enabled learners to gain enhanced perspectives on the health systems and disease burdens in Africa. Students were able to gain clinical knowledge and skills that could be applied in their home countries and enhanced personal and professional development skills. GEMx regional elective exchange program created an opportunity for African students to have more affordable international elective experiences without going to a high-income country. The details of what worked well and the strengths and weaknesses of the models used to develop the program including the lessons learned have been published in another paper (Nawagi et al., 2022). This paper focused on the student experiences. Although this program did not aim at addressing any Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it reflects Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 17which promotes the triangulation of partnerships for sustainable development by 2030 [United Nations (UN), 2015]. This goal (SDG17) postulates the need for partnerships from various global regions with a North-to-South, South-to-South, or a combination partnership model to advance initiatives for development, shared learning, and leverage resources similar to this study’s context. ECFMG, a USA-based organization from the north, provided substantial financial investment and leveraged technology through its web-based application system, and an African coordinating center to manage and coordinate the GEMx regional elective exchange program utilizing a South–to–South model, thus promoting transferable knowledge sharing for sustainable development and practice among the future health workforce. In fact, this was the first time for almost all the students to participate in IEs. Most of the students mentioned they would not have had the opportunity to gain an elective placement outside their home country without the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa. These findings show a significant gap in global exposure for African students through IEs, compared to their counterparts from high-income countries (Olu et al., 2017).

The GEMx regional elective program in Africa helped facilitate a South-to-South model, i.e., mobility within low and middle-income countries in Africa. This resulted in affordable elective costs, i.e., on average, $1,275 for all expenses for 4 weeks compared to $5,000 or higher for other comparable IEs taken in northern America (Amopportunities.org, 2019). The program created an opportunity for African students to have more affordable international elective experiences without going to a high-income country (Bozinoff et al., 2014; TIMS, 2019).

While there was elective diversity in this study with over 18 elective specialties, most of these electives were clinical, with only one in public health (Social Medicine). This was because the vast majority of schools offer clinical electives, and mainly medicine, nursing, and pharmacy students were selected to participate in the program. This scenario can be compared to multiple incidents where many international electives are usually clinical in the region and globally (Neel et al., 2018). A similar occurrence is further indicated in a study among Saudi Arabia students who went for electives in other countries with the majority going for clinical electives (Neel et al., 2018).

Globally, efforts are being made in health professions education to achieve equity with the ultimate goal of producing a competent future health workforce with exposure to various or similar disease burdens in different settings (Beaglehole and Bonita, 2010). In this pilot study, all students reported gaining knowledge and skills that are applicable and transferable to their home country. This is because they were exposed to systems and disease trends within the same region (Africa). Flinkenflögel et al. (2015) conclusions are similar in that Rwandan family medicine residents were able to achieve their learning objectives and gained knowledge applicable to their home country during a South African family medicine elective (Flinkenflögel et al., 2015). However, the study was quantitative with a sample size of only five residents being studied for their learning outcomes (Flinkenflögel et al., 2015). Our study is one of the few large studies using a quantitative approach in Africa to document learning experiences in regional elective programs among health professional students and thus, strengthens the argument for the importance of regional elective programs in health professional training. IEs experiences, outcomes, and their impact are widely documented among medical students (Law and Walters, 2015). Our study is one of the few that has documented experiences with a multidisciplinary representation from medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and laboratory medicine coupled with undergraduate and postgraduate experiences in Africa.

Students participated in learning activities that include clinical examinations, observation of procedures, ward rounds, history taking, and course seminars among others. These are similar learning activities that students in high-income countries are exposed to when they go to low and middle-income countries for IEs (Kumwenda et al., 2014), and when a few students from low and middle-income countries go to high-income countries (Abedini et al., 2014). A caveat to note is that many of the students were not able to perform clinical procedures independently simply because they were undergraduate students and not ethically eligible to independently perform procedures. However, all those eligible to practice, i.e., the ophthalmology postgraduates performed procedures because they were eligible for temporary practicing licenses for the duration of their elective upon arrival to their host institution. This exhibits another strength of the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa which provided opportunities for hands-on clinical training to enhance skills learning for postgraduate students, unlike the South-to-North electives that are largely observer ships (Abedini et al., 2014; Amopportunities.org, 2019).

While electives are very common in the medical curriculum for students in high-income countries (Law et al., 2013), this is not the case for many African students. More than three-quarters who participated in this program did not gain credit or grades for their elective and utilized their semester break to take the elective. Given the learning experiences gained during a regional and international elective placement, African health professional institutions may want to consider adding electives to the curriculum that enable students to select IEs. Currently, only a few institutions like Makerere University (MakCHS, 2019) and the University of Witwatersrand (University of Witwatersrand Johanesburg, 2019) among others, have electives as part of their medical curriculum and allow students to take IEs.

From this study, we learn that the regional elective exchange model enabled students to obtain learning experiences similar to those obtained by students who participate in the North-to-South elective programs (Kumwenda et al., 2014). Furthermore, participants in this study describe positive attitude change in participation in regional (South-to-South) electives which is similar to students who went for the North-to-South electives (Stone et al., 2022). This is further indicated by almost half of the students in this study who mentioned that they would advocate for positive change and implement better practices back home. In this study, we used the values of IMEs developed by Dowell and Merrylees (2009) to report and analyze the student experiences. From the literature, under the value of global perspectives, specifically cultural awareness, and integration, students who participated in the North-to-South electives have often reported difficulties (Kumwenda et al., 2014). This is often referred to as cultural shock, which is an occurrence where one finds difficulty in integration when in a setting they are not familiar with Mitha et al. (2021). In the South-to-South electives, given exposure to almost similar settings, integration and the value of global perspective in relation to cultural awareness and integration just like in this study are often easily navigated which could be a strength. Nevertheless, the values of IMEs developed by Dowell and Merrylees (2009) have been used by other studies globally and in Africa (Daniels et al., 2020) to report student outcomes during international electives qualitatively and have been useful in widening the lens of the analysis of the student’s experiences. This study through its results section attempts to report the findings quantitatively which add validity and strength to the IMEs values developed by Dowell and Merrylees (2009).

The pilot GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa confirmed the importance of regional elective programs in addressing the existing gap in international exposure for African health professional students. Upon completion of the pilot, seven more institutions were added to the various networks, and a new institutional network called the College of Pathology for East Central and Southern Africa (COPECSA) was added in 2019. By the end of 2019, a total of 199 electives had been offered to students. Due to COVID-19 that caused hardships in physical mobility, the program has continued to run with a changed virtual interprofessional education approach in partnership with AFREhealth. From 2020 to date, 125 students have participated virtually using country-specific case studies. Funding for the virtual elective program is being provided from the AFREhealth NIH grant while the physical mobility continuity is still going to be funded using the ECFMG challenge grant with a focus on clinical exchanges and is expected to run again in 2024.

In terms of limitations, it is essential to note that this pilot study reports the experiences of immediate outcomes after the student’s elective completion and not the long-term impact. However, the findings of the survey were used to explore in-depth students’ experiences based on responses to the open-ended questions. This study’s objective did not include any relationships between the student’s experiences and their characteristics which may be crucial in affecting the student’s general experiences during the elective placements. However, the students who were included were all those already in their clinical years of training in the various disciplines which enabled familiarity with the clinical and community settings where most of the international electives take place. This study did not collect baseline data on the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of program participants but, instead, only collected post-program data, making a change in these variables impossible to determine. A longitudinal study to establish the long-term transformative change is crucial and integral to assessing the impact of the electives on students’ medical education, careers, attitudes, global perspectives, and clinical skills. Furthermore, an impact study with a rigorous longitudinal study design that systematically examines elective participation outcomes and their relationships with the student’s characteristics is vital.

6. Conclusion

The outcomes of this study support the fact that the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa provided a useful platform to enable health professional students to gain enhanced global perspectives in health, acquire clinical knowledge and skills applicable to their home country, enhance personal and professional development, and promote positive attitude change in various health care delivery approaches.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Euclid University, School of Global Health, and Bioethics an intergovernmental and treaty-based institution under the United Nations Treaty Series 49006/49007 (Reference: IRB-2019-LTR-0705). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FN led the implementation of the program, analyzed data, and developed the first manuscript. AI, JS, and SY assisted in manuscript preparation. SM provided the oversight role and guidance in all steps of the manuscript development. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the management and executive leadership of ECFMG and FAIMER who have supported the development of the program to date. We truly appreciate Marta van Zanten, a senior associate at FAIMER that has worked with us in the technical writing of this manuscript. Furthermore, we highly appreciate the contribution and support of the different network associations, committed partner institutions, and students who have participated in this program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1181382/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

GEMX, Global Educational Exchanges in Medicine and the Health Professions; IEs, International electives; AFREhealth, African Forum for Research and Education in Health; COECSA, College of Ophthalmology of East Central and Southern Africa; COPECSA, College of Pathology of East Central and Southern Africa; EAHPEA, East African Health Professions Educators Association.

References

Abedini, N. C., Danso-Bamfo, S., Moyer, C. A., Danso, K. A., Mäkiharju, H., Donkor, P., et al. (2014). Perceptions of Ghanaian medical students completing a clinical elective at the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad. Med. 89, 1014–1017. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000291

Amopportunities.org (2019). AMOpportunities-on-demand US clinical experience for medical students & doctors. AMOpportunities. Available at: https://www.amopportunities.org [Accessed September 17, 2022].

Basu, L., Pronovost, P., Molello, N. E., Syed, S. B., and Wu, A. W. (2017). The role of South-North partnerships in promoting shared learning and knowledge transfer. Glob. Health 13:64. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0289-6

Beaglehole, R., and Bonita, R. (2010). What is global health? Glob. Health Action 3:5142. doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

Bozinoff, N., Dorman, K. P., Kerr, D., Roebbelen, E., Rogers, E., Hunter, A., et al. (2014). Toward reciprocity: host supervisor perspectives on international medical electives. Med. Educ. 48, 397–404. doi: 10.1111/medu.12386

Centre for International Mobility CIMO (2015). North–south–south 10 years: A decade of supporting development through academice mobility. Available at: http://www.cimo.fi/instancedata/prime_product_julkaisu/cimo/embeds/cimowwwstructure/67206_NSS_10_years.pdf [Accessed January, 2023].

Daniels, K., Thomson, E., Nawagi, F., and Flinkenflögel, M. (2020). Value and feasibility of south-south medical elective exchanges in Africa. BMC Med. Educ. 20:319. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02224-z

Dowell, J., and Merrylees, N. (2009). Electives: isn’t it time for a change? Med. Educ. 43, 121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03253.x

Eaton, D. M., Redmond, A., and Bax, N. (2011). Training healthcare professionals for the future: internationalism and effective inclusion of global health training. Med. Teach. 33, 562–569. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.578470

ECFMG (2019). Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. ECFMG. Available at: https://www.ecfmg.org/ [Accessed September 17, 2022].

Engel, L., Sandström, A. M., van der Aa, R., and Glass, A. (2015). The EAIE barometer internationalisation in Europe. Amsterdam Netherlands: European Association for International Education (EAIE).

FAIMER (2021). Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER)| about us. Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research. Available at: https://www.faimer.org/about.html [Accessed August 24, 2022].

Flinkenflögel, M., Ogunbanjo, G., Cubaka, V. K., and De Maeseneer, J. (2015). Rwandan family medicine residents expanding their training into South Africa: the use of South-South medical electives in enhancing learning experiences. BMC Med. Educ. 15:124. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0405-3

GEMx (2019). GEMx - global educational exchange in medicine and the health professions. Available at: https://www.gemxelectives.org/ [Accessed September 17, 2022].

Gribble, N., and Dender, A. (2013). “Internationalisation and health professional education” in Educating health professionals practice, education, work and society (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 223–234.

Kumwenda, B., Royan, D., Ringsell, P., and Dowell, J. (2014). Western medical students’ experiences on clinical electives in sub-Saharan Africa. Med. Educ. 48, 593–603. doi: 10.1111/medu.12477

Law, I. R., and Walters, L. (2015). The influence of international medical electives on career preference for primary care and rural practice. BMC Med. Educ. 15:202. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0483-2

Law, I. R., Worley, P. S., and Langham, F. J. (2013). International medical electives undertaken by Australian medical students: current trends and future directions. Med. J. Aust. 198, 324–326. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11463

MakCHS (2019). Mak CHS curriculum maps | Makerere University College of health sciences | MakCHS. Available at: https://chs.mak.ac.ug/content/makchs-curriculum-maps [Accessed November 1, 2022].

Mitha, K., Sayeed, S. A., and Lopez, M. (2021). Resiliency, stress, and culture shock: findings from a global health service partnership educator cohort. Ann. Glob. Health 87:120. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3387

Muir, J., Farley, J., Osterman, A., Hawes, S., Martin, K., Stephen Morrison, J., et al. (2016). Global Health programs and partnerships: evidence of mutual benefit and equity. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Nawagi, F., Iacone, A., Seeling, J., and Mukherjee, S. (2022). Developing an African medical and health professions student regional elective exchange program: approaches and lessons learned [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review]. MedEdPublish 12. doi: 10.12688/mep.19095.2

Neel, A. F., AlAhmari, L. S., Alanazi, R. A., Sattar, K., Ahmad, T., Feeley, E., et al. (2018). Medical students’ perception of international health electives in the undergraduate medical curriculum at the College of Medicine, King Saud University. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 9, 811–817. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S173023

Olu, O., Petu, A., Ovberedjo, M., and Muhongerwa, D. (2017). South-South cooperation as a mechanism to strengthen public health services in Africa: experiences, challenges and a call for concerted action. Pan Afr. Med. J. 28:40. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.40.12201

Organisation for Economic Co-operation (OECD) (2004). Internationalisation of higher education. SAGE publication Inc.

Stone, S. L., Moore, J. N., Tweed, S., and Poobalan, A. S. (2022). Preparation, relationship and reflection: lessons for international medical electives. J. Roy. College Phys. Edinburgh 52, 95–99. doi: 10.1177/14782715221103406

TIMS (2019). How much will a clinical elective in the US cost? The Indian Medical Student. Available at: https://theindianmedicalstudent.com/how-much-will-a-clinical-elective-in-the-us-cost/ [Accessed September 17, 2022].

Tsang, M. K. L. (2011). An elective placement in Africa. Nurs. Times Available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/critical-care/an-elective-placement-in-africa/5024162.article [Accessed October 25, 2022].

United Nations (UN) (2015). The sustainable development agenda. United Nations sustainable development. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ [Accessed August 27, 2022].

University of Witwatersrand Johanesburg (2019). Medicine (MBBCh) - Wits University. Available at: https://www.wits.ac.za/health/academic-programmes/undergraduate-programmes/medicine-mbbch/ [Accessed August 27, 2022].

Keywords: regional elective exchanges, Africa, internationalization in health professions education, students, South-to-South model

Citation: Nawagi F, Iacone A, Seeling J, Yuan S and Mukherjee S (2023) Experiences of health professional students’ participation in the GEMx regional elective exchange program in Africa. Front. Educ. 8:1181382. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1181382

Edited by:

Ashti A. Doobay-Persaud, Northwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Brett Nelson, Harvard Medical School, United StatesFred Rose, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United States

Copyright © 2023 Nawagi, Iacone, Seeling, Yuan and Mukherjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Faith Nawagi, Zm5hd2FnaUBmYWltZXIub3Jn

Faith Nawagi

Faith Nawagi Anna Iacone1

Anna Iacone1 Justin Seeling

Justin Seeling Snigdha Mukherjee

Snigdha Mukherjee