- 1Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Santiago, Chile

- 2Facultad de Educación, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Santiago, Chile

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the discourse on mental health has strongly permeated educational spaces. This is evidenced by the proliferation of policies and initiatives related to Social and Emotional Learning (SEL), which urgently emphasize socio-emotional development and the psychological and subjective well-being of students. This phenomenon makes it necessary to study how professionals should take responsibility and implement a series of practices to respond to these initiatives and policies, many of which are improvised and poorly understood by the community. The aim of this article is to analyze the narratives of professionalization produced by educational agents responsible for implementing SEL policies in Chilean schools. For this purpose, in-depth narrative interviews were conducted with 12 primary education actors, including principals, educational psychologists, school climate coordinators, and homeroom teachers. The participants were selected from different types of educational institutions, including public schools, subsidized private schools, and private schools. Through an inductive Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA), two main themes were identified that articulate the professional experience of implementing SEL policies among the interviewees: (1) commitment to SEL and the (dis)continuities between institutions and personal efforts, and (2) initial and ongoing training for the implementation of SEL. Moreover, from these two proposed themes, various sub-themes emerged, classified according to the types of professionals interviewed and the complexities associated with the types of schools where they work. These sub-themes demonstrate how discourses on the emotional dimension and SEL in schools translate into concrete implications, both subjective and material, regarding the daily work of the interviewees. Finally, the article discusses the complexity arising from the narrative differences among professionals, particularly in terms of their initial and ongoing training, as well as the importance of shared commitments among communities in recognizing the work carried out by these professionals.

1 Introduction

The last few decades have been characterized by what Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014) have labeled the emotional turn in education, which consists in the mass proliferation of studies on the importance, application, design, and evaluation of programs aimed at developing the emotional dimension in educational establishments, with this phenomenon remaining stable since the mid 1990s to date. Likewise, international entities such as The World Bank and the Organization for Co-operation and Economic Development encourage countries to implement educational policies that promote the development of “soft skills.” These include socio-emotional skills, regarded as one of the most relevant tools for successfully entering the 21st century job market (see The World Bank, 2015). With this goal in mind, the OCDE (2017) administered the first PISA test of Subjective Well-Being in 2015, a landmark event in the evaluation of dimensions other than the cognitive which focused on students’ mental health.

In this regard, several policies have been introduced in Chile to foster students’ socio-emotional development. These include the definition of Education as an integral process, proposed in the General Education Law, encompassing emotional and spiritual dimensions of development, among others (Ley 20370, 2009); the updated version of the National School Climate Plan (Ministerio de Educación, 2019); and the Cross-Curricular Learning Objectives (OAT); among other policies currently in force. Furthermore, efforts have been made to expand the way in which education quality is measured and understood. One such attempt was made in 2014, when Social and Personal Development Indicators (IDPS) –e.g. academic self-esteem and motivation, school climate, civic engagement, civics– were introduced to complement the academic indicators measured by SIMCE1 (Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación, 2017).

In addition to the above, after the pandemic and health crisis of the year 2020, the Ministry of Education developed a set of documents that are noteworthy due to the direct use of the term ‘socio-emotional’ (Ministerio de Educación, 2021), including a self-care guide entitled “Keys to Well-Being. A Logbook for Teacher Self-Care Based on the Emotional Intelligence and Positive Psychology Principles” (Ministerio de Educación, 2020). The Ministry also produced a guide for a socio-emotionally safe return to school (Ministerio de Educación, 2021) and a tool repository entitled “School Climate and Socio-Emotional Learning Toolbox” (Ministerio de Educación, 2021). Finally, in 2021, the Integral Learning Diagnosis System was implemented, incorporating evaluation tools that provide diagnostic information about students’ socio-emotional learning outcomes (Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación, 2021); in addition, authorities implemented the Socio-Emotional Guidelines and Skills System, composed of a set of Pedagogical Fact Sheets for Socio-Emotional Skills, along with the Strategies for Socio-Emotional Development through the National Curriculum. All these documents were developed upon the basis of the notion of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL), following international guidelines (see CASEL, 2023a).

Emotions have a long history in education and are not necessarily a topic of recent interest (see Abramowski, 2015, 2022; Toro-Blanco, 2018, 2019). Dewey (1997/1938) already took pains to argue how emotional experience plays an important role in the formation of intelligence and learning. Vygotsky, on his part, was not only concerned with the role of emotions in learning but was also interested in producing a theory about the development of emotions and their interweaving with historical-cultural aspects of knowledge (Vygotsky, 1933/2017). In particular, it is feasible to think that Vygotsky conceived emotional development under the same principles of development as the rest of the higher psychic processes, characterized by the functional systemic transformation of the psyche in relation to socioculturally directed tasks and activities (Vygotsky, 1930/2014; Bonhomme, 2021). Given this, the idea of the social situation of development becomes important (González-Rey, 2000), as the subjective experience during the learning process is fundamental to understanding the meaning of these systemic transformations. Thus, emotions are a psychological function capable of developing like any other psychological function (memory, attention, language, thought, perception, etc.) to become a higher psychic process (Bonhomme, 2021). At the same time, they play a transcendental role in the experience—whether of school learning or not—in terms of giving subjective meaning to any process of change and development (González-Rey, 2000). This is fundamental to understanding a pedagogy in which students have an active role in their learning process and in the shaping of a liberating education (Bruner, 1990; Freire, 2000/1970).

According to the above, emotions are not entities that inhabit the interior of the subject and are oriented from the inside out in the experience (Le Breton, 2013). In the educational field, it is crucial to understand schools as institutions that transform learning processes and guide development through specific socio-historically situated ways (Rogoff, 1990). Based on this, education and the pedagogical means of teaching can be understood in the same sense that Vygotsky (1925/2006) attributed to the function of art: as a social technique of emotion. Education plays an active role in the transformation of psychological systems, having the potential to produce creative paths of development (Vygotsky, 1931/2012). This is fundamentally important when the socio-emotional development of students and the shaping of affective schools take on particular socio-political relevance (Kaplan, 2022).

However, the emerging concern for the socioemotional dimension in learning had its most recent boom since the nineties through a so-called emotional turn (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014), which has its main antecedent in the concept of Emotional Intelligence (Mayer and Salovey, 1990). Similarly, from that term, the global agenda of educational policies has placed emotions and the non-cognitive dimensions of development as nodal aspects for the competencies of the 21st century and in the promotion of well-being and social development of students and educational communities (OECD, 2016; OCDE, 2018; UNESCO, 2020). Although the term Emotional Intelligence is no longer preponderant for educational policy in the field of socioemotional development, the new conceptualization from the SEL (CASEL, 2023a) shares the assumption of pointing to the individual and cognitive capacity to manage and express emotions correctly (Bisquerra-Alzina and Pérez-Escoda, 2007; Goleman, 2010; Menéndez, 2018; Seligman, 2019; Barría-Herrera et al., 2021).

The term Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) was coined by the Collaborative for Academics, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and is defined as:

The process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions. (CASEL, 2023a, para. 1).

CASEL is an organization that has among its objectives “to establish high-quality, evidence-based SEL as an essential part of preschool through high school education” (CASEL, 2023b, para. 10). A pioneering force in the promotion of SEL with a three-decade presence in the USA, it proposes that SEL is based on the development of 5 specific competencies: Self-management, Self-awareness, Responsible decision-making, Relationship skills, and Social awareness.

At the educational policy level, SEL can be regarded as a “multifaceted umbrella term that encompasses multiple types of social and emotional competences as well as moral attitudes and dispositions” (Pérez-González, 2012, p. 58). It is worth noting that educational policies can present emotional education in both a restrictive and a lax sense (Pérez-González, 2012). Restrictive policies are explicitly aimed at developing thoroughly defined competencies (e.g., RULER, PATHS, Second Step). In contrast, lax policies cover multiple actions and statements that loosely incorporate efforts associated with a broad spectrum of what SEL is. These aspects of SEL may include various related concepts such as classroom climate, participation and involvement, academic, self-esteem, and sense of belonging, among many others, which encompass and/or compose the socio-emotional dimension of learning. In this regard, the plans and adjustments of SEL-oriented educational policies can be highly variable and not refer to specific programs (Pérez-González, 2012).

Due to the complex political reality of education in Chile, it makes sense to adopt the lax SEL policy categorization to discuss the situation in the country’s educational establishments. Thus, it is possible to identify a cluster of SEL-oriented policies, like those mentioned above, aimed at incorporating this dimension of learning in a variety of ways, beyond the implementation of specific programs.

It is important to understand schools as “places of intersection of networks and processes that exceed the physical and institutional boundaries of school space” (Rockwell, 2005, p.28). In addition, according to Ball et al. (2012), “policies create context, but context also precedes policies” (p. 19), which means that SEL policies converge in the specific context of a school, coexisting with other policies and other contexts. Likewise, many policies co-occur in schools, with certain subsets targeting similar principles (such as the SEL policies mentioned above) and others focusing on a wide variety of purposes. Furthermore, it is worth stressing that not only Ministry-developed policies coexist in schools, since there are also internal, municipal, and other policies in place (Braun and Maguire, 2018). Thus, the authors of policy enactment theory focus on how top-down political demands are absorbed in various ways depending on the particular context of each school, according to how valuable they are to schools and to individual educational agents (Ball et al., 2012; Vincent, 2019).

An important aspect of the enactment of policies is how they are translated and interpreted by educational agents (Ball et al., 2012). According to Hoffman (2009), most research on SEL policies focuses on the implementation and evaluation of specific programs, seeking to describe and defend said programs. Based on the nomenclature proposed above, these studies examine restrictive SEL policies (Pérez-González, 2012). In this regard, to study SEL policies, “it is important to bear in mind that what teachers or other educators actually do in the classroom may be different, and that program implementations can and do differ considerably across contexts” (Hoffman, 2009, p. 534–535). Even though more than a decade has passed since Hoffman advanced these views (2009), to date few researchers have analyzed SEL policies taking into account how educational actors and schools (re)interpret and translate them in order to enact them (for some exceptions, see Vincent et al., 2016; Barnes and McCallops, 2019; Spohrer, 2021).

Studies focused on educational actors are still emergent (see Collie et al., 2011; Muñiz, 2020; Sorondo, 2023), seeking to analyze internal school factors crucial to the successful implementation of SEL programs. Some of these studies highlight the importance of commitment to SEL (see Collie et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2019) and the training provided to professionals (see Esen-Aygun and Sahin-Taskin, 2017; Barnes and McCallops, 2019) as factors leading to adequate SEL program implementation.

Based on the above, the present article examines the way in which professionals narrate their experience during the policy enactment process, underlining two main aspects of their professional activity: commitment and training. In addition, the article seeks to reveal how these factors involved in the implementation of SEL policies are interpreted and experienced differently according to the interviewees’ professional discipline and specific functions as well as the values of the school where they work.

2 Method

2.1 Design

This article is an outgrowth of a project aimed at analyzing the narratives about emotional factors and the enactment process conveyed by professionals in charge of implementing Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) policies. Its research design is grounded in a narrative perspective (Schöngut-Grollmus and Pujol, 2015) whereby narratives are regarded as performative and transformative actions, embracing the view that subjects who produce them simultaneously construct their own experience and its meanings (Schöngut, 2015). Also, the study is inspired by the theoretical-methodological contributions of Ball et al. (2012) concerning the implementation of educational policies, acknowledging that they are not blindly and linearly reproduced by educational actors, but that they are translated and interpreted by them.

Fieldwork was conducted during 2021, while lockdown measures were in force. The data production strategy employed was the narrative interview (Murray, 2018), which can be either structured or semi-structured depending on the issue that the researcher intends to study (Roulston and Choi, 2018). This technique was adopted in order to capture both the emotional dimension and the implementation efforts of the interviewees. The interviews, which lasted between 1 h 30 min and 2 h 15 min, were conducted over Zoom and audio-visually recorded.

2.2 Participants

The interviewees were professionals who worked with students in primary education and who were in charge of implementing SEL proposals, initiatives, and policies in their schools. They were selected according to their position in the school hierarchy, considering the availability and overall presence of these positions in Chilean educational establishments as well as the agents’ involvement in the promotion, management, and enactment of SEL policies. For this reason, institutional affiliation was not used as a selection criterion, and efforts were made to safeguard the interviewees’ personal anonymity and that of their schools.

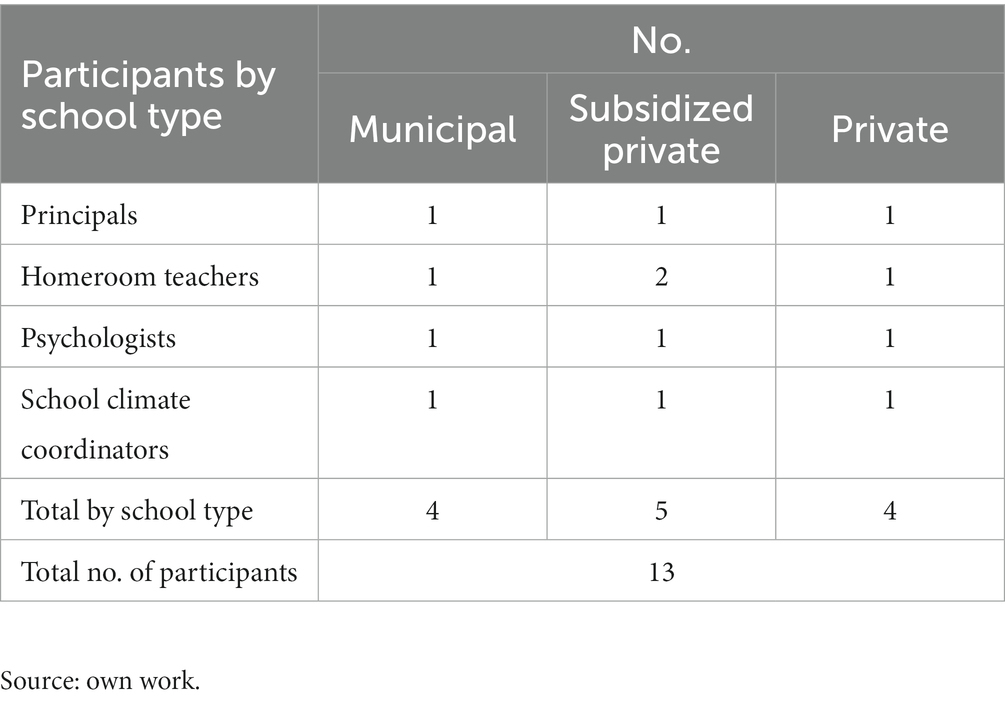

The sample included all three school administration types in Chile (Municipal, Subsidized Private, and Private), with one agent per position being interviewed for each.

Based on the above, agent positions and the number of interviewees per school type are shown in Table 1. In almost all cases, it was possible to conduct the minimum number of interviews required by the methodological design (one representative per position and school type). Nevertheless, in order to uphold the agreement with the participants and take advantage of the richness of the interviews, the decision was made to conduct two interviews with homeroom teachers from two different subsidized private schools, which were subsequently transcribed and analyzed.

2.3 Analysis strategy

The data were examined using Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA), considered to be a specific approach derived from Thematic Analysis (TA), which is a general term used to refer to a set of approaches focused on the identification of themes (meaning patterns) present in the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2022). The defining traits of RTA are its theoretical flexibility and the opportunities that it provides for the researcher’s subjectivity to play a major role. This means that the researcher’s subjectivity can be used in various situations to answer and adapt to multiple types of research questions, where neither the researcher’s analytic choices nor the topics constructed are neutral (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2022). This perspective openly acknowledges the impossibility of attaining neutrality and is built on the assumption that the thematic selection of data already introduces a complex, theoretically motivated act of analysis. However, although the analysis performed adopts the criteria of an RTA, the topics presented in this article were inductively proposed, being derived from the data themselves (Patton, 1990; Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2022). Based on this logic, the theme production process for this article was similar to that of grounded theory; however, the study freely switched from theoretically oriented (deductive) thematic generation processes and processes directly derived from the data (inductive).

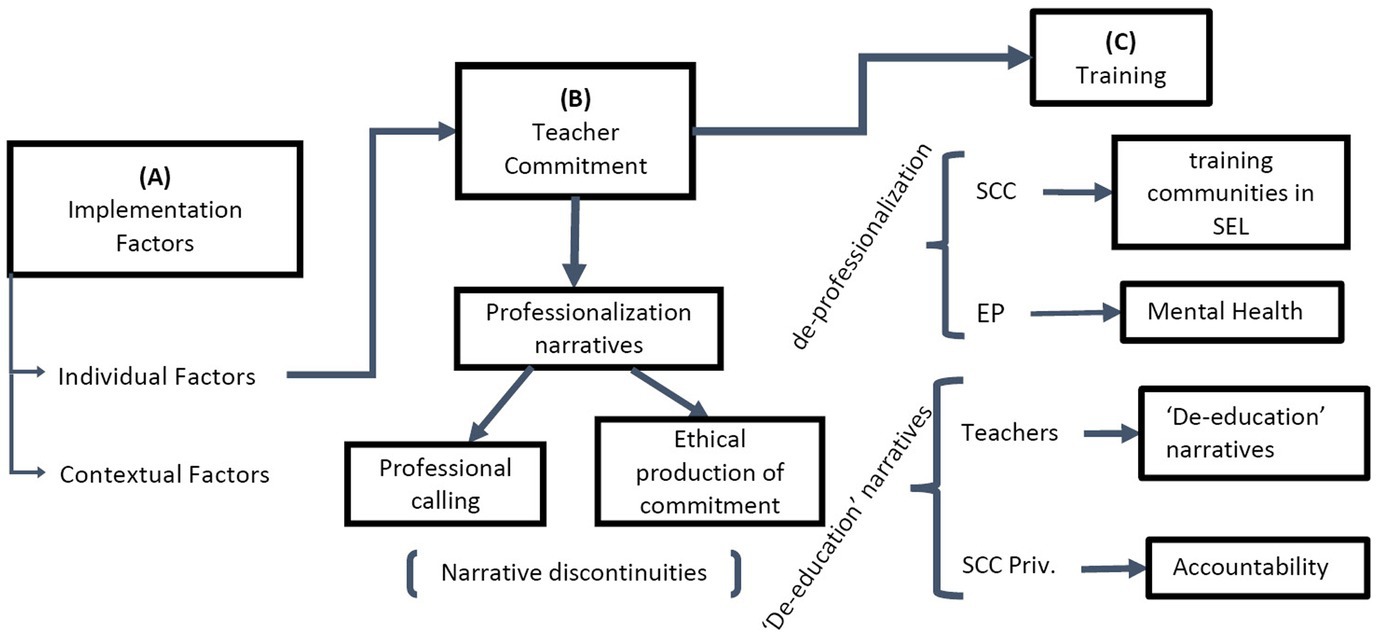

An inductive RTA revealed two main topics that articulate the professionals’ experience during the implementation of SEL policies: (1) commitment to SEL and discontinuities between the institutional level and their personal efforts; (2) initial and continuing training for the implementation of SEL. The aforementioned themes were extracted in the search for factors that influence the implementation of SEL policies by the participants, either hindering or facilitating their professional practice. Thus, two main categories were recognized: contextual factors and individual factors. Within the individual factors, commitment and training (initial and continuous) were identified as two fundamental thematic nodes in the construction of professionalization narratives by the agents interviewed.

The interviews were thematically coded using Atlas.ti V.22 and were then sorted according to a criterion of familiarization with the data, themes, and sub-themes. Thus, the analysis process can be charted in the following sequence: (1) familiarization with the transcribed interviews; (2) production of initial codes; (3) identification of common themes that encompass the experience of the professionals; (4) review of the constructed themes and analysis of narrative discontinuities; (5) definition of the two main themes and classification by professional role and type of establishment; and (6) elaboration of the narrative (dis)continuities as sub-themes that stress the professional roles in the implementation of SEL policies.

The analysis path can be seen in the diagram in Figures 1A–C by focusing on the individual factors present in the research project data.

2.4 Ethical considerations

The study followed the core ethical principles laid out in the TCPS2 (2018) pertaining to actions and tasks that involve human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence (or concern for welfare) and justice. Furthermore, the Institutional Review Board of Universidad Alberto Hurtado ruled that both the design and the Informed Consent (IC) protocol met its ethical standards. Each participant took part in the IC process voluntarily, signing the document prior to the interview. In addition, alongside the researchers, the participants read their rights and the IC and were given the opportunity to voice their doubts and/or questions regarding the process or the objectives of the project.

3 Results

This section presents the professionalization narratives of actors tasked with implementing SEL policies and initiatives in schools. These narratives revolve around two proposed topics, linked to specific factors that the agents describe as central in their daily SEL implementation work: (I) commitment and (dis)continuity between the institutional domain and their personal efforts; (II) initial and continuing training. Each of these themes will be organized by type of school and type of participant.

Figures 1B,C shows in a didactic way the main discursive nodes, narrative discontinuities, and implications (professionalization and de-professionalization) that emerge from the results in an intersectional manner (according to the role of the agents interviewed, type of institution and main topic: commitment/training).

3.1 Commitment to SEL and (dis)continuities between the institutional level and personal efforts

When referring to their work implementing SEL initiatives and policies, the interviewees organized their professional narratives around commitment, but this position varied across types of professionals and schools.

3.1.1 The importance of one’s professional calling according to school principals

Principals of all school types appealed to educational community members to make a personal commitment to students’ SEL. For example, the principal of a private school states the following:

First, we need to be personally convinced that emotional aspects are important, so, if I’m certain of this and I see a child crying in my class, I’m going to stop the class, and of course I’m not going to say, “you, crybaby, get out,” and resume my Math or Language lesson. So, I need to demonstrate that emotional aspects are valuable to me, that’s really important for me as an educator (Principal, Private School).

Overall, the interviewed principals tend to highlight the value of community members’ individual commitment to SEL. In this regard, for the principals, being committed to the emotional aspects of teaching is part of every actor’s duty to education in general and a major component of their professional calling. Another principal illustrates this point as follows:

The main thing is to be committed to education, to one’s profession, that’s the most important thing, one’s commitment to education, because that drives everything. A committed person will make every effort in their power; last year, some teachers from this school went to students’ homes because their parents did not answer the phone, did not come here, did not check their messages, did not answer their emails, so, because of that, some teachers said, “okay Mrs., I’m going to that girl’s house myself to hand her the booklets, the material, the texts”; that’s commitment, that’s truly devoting your life to education (Principal, Subsidized Private School).

Commitment to SEL —and education in general— is an important factor in school principals’ professionalization narratives. However, they reference the individual professional calling of their school’s teachers, a quality they may be entitled to demand but one that is challenging to target and address using administrative tools. Thus, a lower level of control over the teaching team can lead to discontinuities between administrative/institutional guidelines and the actions of individuals. This issue is described as follows by a municipal school principal:

I still have a couple of teachers who are still a bit, so to speak, rigid, but I cannot criticize them because I used to be like them too, but I’m trying to soften them and tell them that this is not a waste of time, because teachers sometimes come here and say, “hell, I started the lesson and wasted 30–40 min because the students were not feeling well at first, they did not have a good night’s sleep, had trouble sleeping, the others were still saying they were afraid.” So now I tell them that this is not a waste of time, in fact, it’s a way to gain experience, at the very least you are making students feel that someone’s listening to them (Principal, Municipal School).

3.1.2 The ethical production of teacher commitment

In contrast, for the interviewed teachers, commitment is an aspect of their daily efforts aimed at increasing their students’ well-being. In their view, commitment is related to the ethics-based work that they carry out every day:

If you ask me, I worked really hard last year to make sure the kids were all right and had everything they needed, plus, I wanted all the objectives to be met and to fulfill all my expectations; maybe it has to do with the things you want… you think, “I want those things to happen, I want them to happen my way, I have to do things my way,” so, at least on my part, I achieved all I had set out to do, which was to ensure a good outcome for my students (Homeroom Teacher, Subsidized Private School).

In line with the above excerpt, another homeroom teacher is unable to separate her commitment to SEL from her commitment as an educator, because, as a teacher, she spends long stretches of time and several subjects with her students. She links this phenomenon to the cross-curricular nature of SEL in her daily actions and her pedagogical work:

So, regarding the cross-sectional nature of this emotional education, I’m the one in charge, me alone, as the homeroom teacher, because I’d say that teachers of other subjects do not really take charge, it’s the homeroom teacher who has to do nearly everything. There are some evident reasons; I spend 22 h per week with my class. The way things work in my school, I teach every subject, I teach Natural Sciences, Language, Social Sciences, Mathematics, and Orientation, I mean, I spend a lot of time with them, so (…) my personal intention (…) the decision to continue delivering this emotional education is mostly mine (Homeroom Teacher, Private School).

Aligned with this perspective, the interviewed teachers’ responsibility entails an ethical commitment that manifests itself in the relationship with their students, which is inextricably linked to their implementation of SEL. Therefore, even though the interviewed principals regard commitment as a quality related to one’s calling, for the teachers, responsibility and commitment to SEL are not necessarily intrinsic to their status as educators. Commitment to SEL is actualized and produced through practice, and like every cultural practice, it is grounded in a set of socio-historical ethos and the actualization of teaching work, based on the socio-cultural demands in which it is embedded. In this regard, a teacher illustrates how professional duties and commitments make it necessary to modify their teaching approaches and pedagogical priorities:

Let me tell you, it’s been 6 years since I changed; they are children, and, look, I live with two children here, and I’d also like someone to ask them what’s going on. I would not like them to have a cold teacher, so I think that also made me change; I would like my children to have a teacher who’s interested in them, not one who comes into the classroom, teaches her lesson, and leaves, but one who cares about how they are feeling (Homeroom Teacher, Municipal School).

This point of view is grounded in a moral attitude toward teaching, which means that commitment to SEL in the implementation of associated policies is not a generalized aspect of their ‘teaching persona’, but a product of a personal and individual process that makes it possible to articulate professionalization narratives in this area.

3.1.3 School climate coordinators and educational psychologists and their intrinsic commitment to SEL: continuities and discontinuities

According to a School Climate Coordinator (SCCs), there can be continuities or discontinuities between this actor and teachers regarding their commitment to SEL:

It completely depends on the homeroom teacher’s attitude, I mean, in the case I was just telling you about, the homeroom teacher is great, he really takes an interest in this, he communicates with us a lot, but if we had a teacher… there are some teachers who do not care at all, they do not listen to us, and there’s not much we can do either (SCC, Private School).

This excerpt indicates that an SCC’s professionalism can either be hindered or increased by the continuity or discontinuity between agents’ level of professional commitment to SEL. Yet, while the interviewed teachers state that commitment to SEL requires practical work and ‘changing’ their approach, the SCCs consider that SEL is closely associated with their profession, since they tend to view it as the ‘core of their work’. From this viewpoint, an Educational Psychologist (EPs) stresses that, since the pandemic, some progress has been made —even if only discursively— to foster the confluence of individual levels of commitment to SEL:

In 2020, I think there was something of a perspective shift, or maybe we started giving more importance to the socio-emotional area, and therefore to school climate teams. Before the pandemic I felt a little alone in this regard, in my job, but now I feel we are working more collaboratively and that the people, the community are beginning to understand the importance of this (EP, Subsidized Private School).

As illustrated above, commitment to SEL involves aspects that, be them cultural or contingent, require a match between the professional commitment of each individual and that of the school community as a whole. Thus, when SEL becomes an urgent concern, the interviewed SCCs report feeling professionally recognized.

3.1.4 Professional commitment in the face of market logics and an outcome-driven focus

When factors are observed which link individual commitments to institutional and/or socio-cultural continuities, it is interesting to note that, in institutions with a strong association between market logics and academic achievement (such as private schools) and where institutional SEL initiatives —despite being internal— seek to fill a void in a changing market, there emerge greater barriers to the establishment of communities committed to SEL. This is vividly illustrated by professionals of schools of this type. Specifically, one of them points out the following:

Your child getting straight sevens2… we have our whole lives ahead of us, let us focus on that. And it’s me who devotes a very large part of my interview guidelines to emotional development. I talk about social, academic, and emotional aspects. However, I’d say I try to tone down the importance of academic outcomes, especially because I work with 3rd graders, it’s not so important what grades they get. I mean, they are an indicator, evaluations are important (…) they show me whether I’m teaching well (…). It’s important not to leave any gaps, but I think, in my school, parents and even people at the institutional level are rather academically-oriented, even though our discourse highlights the importance of the emotional dimension (Homeroom Teacher, Private School).

Similarly, despite the seeming interest that SEL arouses in most private schools —considering the material and professional resources devoted to it— this interest does not appear to extend beyond a declarative level, as commitments are ultimately reliant on each individual’s professionalism. Illustrating this situation, an SCC describes it as a specific event where, despite the resources and means promoted by his institution, his efforts as a promoter of SEL are hindered.

Globally (…), they organize an event that’s like the world well-being day, the [name of program], and they plan it in England (…) that’s where the head office is, so to speak, and they organize really cool activities, schedule talks by experts, develop lots of things, and here things are done quite differently compared to England, the focus is different, I think the principal likes spectacle, so to speak, she likes things to look beautiful, but there’s very little content, so, for example, last year we had these activities and we had a budget and I was trying to arrange a presentation by an expert, but she spent it all hiring some jugglers (…) so that on the day, as they came into the school, parents would see a show with confetti, jugglers, and all that stuff (…) that happens a lot, it’s like they try to show that we really care about this topic (SCC, Private School).

Consistent with the above, the last two interviewees state that a market-driven and/or outcome-oriented perspective is not enough to develop a professional and professionalizing SEL approach and that a fundamental component for achieving this goal is a collective commitment to SEL from educational communities.

Finally, and in contrast with prior experiences, in State-subsidized schools (both private and municipal), commitment to SEL begins to converge within the communities in response to wider socio-cultural demands that materialize into Ministry mandates or guidelines. Specifically, the pandemic helped actors to align their commitments and, as more importance was attached to the socio-affective dimension, professionals detected the need to acquire up-to-date knowledge or transform themselves; in the case of psychologists and school climate coordinators, they began to receive recognition as professionals:

What we have been able to improve is one thing we’d mentioned before, that emotional learning should be given more importance, and school climate teams as well, that has actually changed, I feel, at least compared to my previous job and my first year here, the perspective (…) because the approach used to be much more reactive (…) and now it’s more preventive (EP, Subsidized Private School).

In the same vein, a school climate coordinator describes how the pandemic and her job were re-signified during the pandemic:

This year, for example, the pandemic made the situation clear: teachers were not coming to school (…) they did not come because they asked for permission not to come, and I felt it was right, because they had so much work at home, but we, all the assistants, kept coming to school and stayed here, it’s like we organized the school so that it would keep functioning (…) and so the pedagogical aspect suffered, but it was because of people’s lives, you know? People kept on living and the school was a source of support (…) that’s not the only function of the school, but it’s still a great source of emotional support for families (SCC, Municipal School).

As the above SCC notes, recent discursive changes regarding education and the material complexities derived from the pandemic made it possible for actors to differentiate their individual duties and distinguish themselves professionally. This generates disparities in professionalizing discourses concerning SEL, especially in the area discussed below: the initial and continuing training that professionals receive.

3.2 SEL implementation: initial and continuing training

As noted earlier, difficulties in the creation of professionalization narratives about the enactment of SEL initiatives result from discontinuities between individual and cultural/institutional commitments; in contrast, with respect to initial and continuing training, there are gaps between the actors’ professionalization narratives associated with their individual disciplinary domains.

3.2.1 Administrative training narratives connected to ministry mandates in subsidized schools

From an administrative point of view, schools that start receiving Ministry pressure and demands concerning the socio-affective dimension are forced to implement measures and initiatives of their own, within a climate of uncertainty. With respect to this issue, the interviewed school principals highlight the absence of guidelines:

The Quality Agency’s diagnostic test has a socio-emotional section, right? But whatever specific guidelines we have used in our work, we have had to find, compile, and develop ourselves, because, as I was telling you, we prepared booklets for 2020 and also 2021, and we used our own compilation of material, because there’s nothing else… this urgency appeared suddenly for everyone, with no time to prepare, so it seems they left schools free to devise their own plans to develop the socio-emotional area (Principal, Subsidized Private School).

As the interviewee points out, schools were faced with uncertainty and needed to resort to their own resources and strategies to enact SEL. Likewise, they had no choice but to draw on their own professional experience to acquire the necessary resources to implement these policies. Thus, at the school administration level, actors are affected by a scarcity of tools and training that prevents institutions from meeting the new demands. A municipal school principal describes the situation as follows:

I think we have certain tools we acquire throughout our lives and in our professional career, our day to day work allows us to learn from colleagues, what they are experiencing, what’s going on with their families, and so on, but I feel we need a well-defined path to work on socio-emotional issues in the right way, or rather (…) in a consistent, linear way, I think the Ministry should begin by offering a good course, with psychologists, assistants, I do not know, they should offer a comprehensive view of the issue (Principal, Municipal School).

As this participant illustrates, there is a particularity in the professionalization narratives about the training available to schools that receive State subsidies and Ministry mandates. The interviewed principals begin to notice the pressure exerted by SEL policies, but, simultaneously, the internal weaknesses of their institutions start coming to light; in this context, schools must respond using their own strengths, although this does not preclude calls for additional training and professional advice.

In a different sphere, professional recognition begins to focus on initial teacher training. At this point, the efforts of professionals from other disciplines take center stage, since, according to the logic laid out by the interviewees, they are better equipped to implement SEL policies. Thus, the interviewees consider that it is a strength for communities to have access to professionals from a wide range of areas, as this should enable them to address the many SEL-related challenges facing schools:

Right now, we are making use of our own experience as professionals in each of our roles and the enormous support that the psychologist has been giving us since August, at a municipal level, plus the experience of the 2 psychologists and the social worker in our staff. And the tasks that each one of us must fulfill according to our respective roles. But I feel we are coming up short in that regard, I think we need proper training, proper tools (Principal, Municipal School).

In conclusion, continuing training is deemed to be essential for addressing the gaps between the professionalization narratives of teachers and other professionals who are better equipped to enact SEL policies.

3.2.2 SCCs and institutional strengthening narratives

Even though knowledge or initial training shortcomings can be counterbalanced by the personal commitments discussed earlier, what the interviews reveal is an ‘openness’ on the part of schools to embrace domains outside the pedagogical, with certain professionals playing a more central role in educational cultures. In this regard, professionals with a greater affinity for SEL draw attention to a lack of continuity in the knowledge required for the promotion of these policies in schools:

A problem I see in my community is that people have little knowledge about school climate concepts, I think that may be a factor, well, I do not blame them, my school is a subsidized private one and, to be frank, they only care about money (…) I think whatever little discussion there is about emotional issues is capitalized or monopolized; that focus on money obscures everything else, and we stop learning new concepts, new terminologies, and new tools that not only enable us to do that, but also help us with our primary duties: generating healthy and nutritious environments for learning (SCC, Subsidized Private School).

According to school climate coordinators, educational communities require professional training in SEL and school climate. They stress the importance of continually acquiring new concepts and tools, and analyze their schools critically, demanding a more professional approach to the emotional dimension:

I feel there’s more awareness of emotions, greater ability to identify them, especially, but very little capacity to work on them adequately, in general, there’s this typical attitude that, I do not know, anger is a highly negative emotion, sorrow is an emotion that must be private, there’s no further development beyond that (SCC, Private School).

3.2.3 Narratives of acknowledgment regarding mental health logics in SCCs

Educational psychologists, on their part, manage to develop narrative continuity between the role that their profession demands and their initial and continuing training; therefore, their continuing training is not part of a process detached from their professional role:

I really like what I do and I’m highly aware of the importance of starting to give more importance to socio-emotional issues. I do not like to do things I know nothing about, so I study a lot, I buy lots of books, I read a lot, I want to do things only if I have support, that way I can also back what I say (EP, Private School).

The professional training process allows for narrative continuity to exist between what the professional says and does at school and the professionalism that grounds these words and actions. Thus, continuing training is a process linked to each actor’s initial training and their personal SEL implementation efforts. Likewise, commitment and training are articulated in each actor through institutional change narratives, which make it possible to attach meaning to one’s professional duties:

I’m really happy with everything I’ve achieved because I think I’ve managed to make people understand that there must be a balance between academic outcomes and broader, comprehensive educational objectives (…) and that’s what we are working on, that’s where we are going (EP, Private School).

Since the pandemic, the role of EPs became much more meaningful, precisely as a result of the greater weight of the emotional dimension. This professional begins to occupy an exclusive and particular place within the school, mostly as a result of their contributions derived from their initial education process (as a psychologist):

[during the pandemic] we also tried to reach parents by making recommendations (…) to foster well-being, self-care, talking about what emotions are, what types of emotions exist, teaching them the importance of the emotional dimension; we did the same with teachers and educational support staff, we gave them presentations to raise awareness so that this could also be applied in classes (EP, Subsidized Private School).

The intrinsic value that EPs begin to have since the pandemic resulted from their relationship with mental health, with professional requirements also focusing on that area:

Last year, of course, we were unable to organize the workshops and other similar activities, so I worked a lot as a clinical psychologist. Some days I’d phone several children and we talked and I sort of interviewed their parents (EP, Municipal School).

Therefore, initial education has a larger impact than continuing education on the professional recognition of educational psychologists. This occurs regardless of the distinction between educational psychology and clinical psychology, for example, since the value attached to them results from the relationship between their discipline and the notion of mental health as well as from these professionals’ presumed mastery of socio-affective factors.

3.2.4 Teacher ‘de-education’ narratives

For the teachers interviewed, initial and continuing education involve the acquisition of disciplinary aspects different from those of pedagogy and all the other knowledge acquired during their years of initial education. In this regard, in the face of the proliferation of SEL policies, the interviewed teachers narrate how their professionalization depends on tools that are unrelated to those of their initial education process. This is the case of a private school teacher who had the opportunity to complete a graduate program at a prestigious European university.

I think the great progress I’ve made with this very complex class I was telling you about, I owe it to having studied mediation in socio-educational settings; first of all, that program taught me mediation as a method, a resource for solving problems through peaceful means. It’s amazing (…) how useful that’s been for navigating everyday issues, daily conflicts, children who come to class crying, those who are frustrated (Homeroom Teacher, Private School).

Professionalization narratives with respect to this issue concern finding among one’s tools, or in aspects of one’s specific education process, beyond one’s initial education, the necessary strengths to navigate SEL policies and the new socio-emotional challenges that they pose. As an exception, a homeroom teacher with an undergraduate degree in Physical Education considers that the nature of her pedagogical education and the role of her discipline in her school have the potential to help her to promote SEL in her students:

I cannot ask them to do 60 sit ups in 1 min, like we used to… and those who only did 40 but made a huge effort, got a 5 out of 7, so that means frustration for the person who made his best effort, while someone else did 60 and spent 30 doing nothing because he was a machine. Well, in my school, some teachers have been there for years, so they know what each student is like, but in my subject, since it’s soft, flexible, we do a lot of work on self-improvement, the process, soft skills (Homeroom Teacher, Subsidized Private School).

Initial and continuing education establish the possibility of distinguishing oneself from other teachers, or staying ‘relevant’ by acquiring the capacities needed nowadays. In any case, these deviations from their initial education process involve competences associated with mental health disciplines such as psychology:

In college, we learn the tiniest bit of psychology, probably in 1st year, and when you are out there, actually working, you do not remember much, you learn along the way, but there are some technical concepts, for instance, I had no idea the OPD even existed, I did not know schools had the obligation to report violations of children’s rights, well, I did not really know what school psychologists do (Homeroom Teacher, Subsidized Private School).

The interviewed teachers’ professionalization narratives are focused on their insufficient knowledge about a specific domain, but address the importance of seeking tools and engaging in continuous learning about topics unconnected to their initial education. Thus, they appreciate the support offered by schools and the resources provided the Ministry, which allow them to acquire tools and concepts from other disciplines:

It would be greatly beneficial for us as teachers, since we get so many training programs all the time, a special socio-emotional program would be great because… yes, to be fair, we have received some training opportunities because of our ties with [name of facilitator], I do not know if you have met her, she’s a really good psychologist, we have had those sessions in our school (…) there are talks that we have been able to attend. In general, the school tries to organize events for us to receive information and resources, both for teachers and families (Homeroom Teacher, Private School).

The resources provided by each type of school, along with personal resources, generate differences when establishing narrative continuity in the interviewed teachers’ professional experience. However, training programs are not everything, because it is in the teachers’ daily efforts and in the actualization of their ethical commitments that they devise ways of overcoming their educational ‘weaknesses’ through auxiliary tools or resources:

I try to incorporate learning into my classes (…) especially with 1st and 2nd grades, in character as a clown, telling stories and creating stories, and after that, we return to the routine that we have implemented in our school, and we show, for example, several videos to facilitate a learning process (Homeroom Teacher, Municipal School).

This excerpt shows that the interviewed teachers’ training narratives follow the same productive logic of their commitment to SEL; however, receiving training in this area is a task that, again, requires them to transform their initial education.

4 Discussion

Commitment and training are factors that influence the way in which actors depict their professionalization processes in connection with their work implementing SEL policies and initiatives.

The school principals interviewed in the study, for example, produce commitment narratives that make reference to the professional calling of the people working in their institutions. In these appeals, there is a notion of professional calling that articulates the configuration of an affective category in teachers (Abramowski, 2022) that plays a key role in their professionalization frameworks, and which is not precisely the remnant of a supposedly religious order that should be ignored (Abramowski, 2015); rather, this category has the function of politically organizing teachers around a profession that, at the time, constituted a modern educational project (Abramowski, 2015, 2022). This appeal operates as both a general and an individual call to actors in the educational domain, urging them to act professionally.

The individualistic notion regarding professional vocation aligns with evidence indicating that teacher commitment is commonly associated with dedication to teaching, students, and school. However, commitment is less associated and studied about adaptability to change (Sun, 2015). On the other hand, research indicates that teacher commitment is significantly influenced by instructional leadership and alignment with institutional value systems (Collie et al., 2015; Sun, 2015; Anyon et al., 2016). Studies suggest that narrative discontinuities may explain how principals disengage from their role within SEL commitment, which impacts teachers’ job stress (see Collie et al., 2015).

On the other hand, the ethical production of commitment by teachers has an ethical and contingent quality, linked more to their professionalism than to their vocation, is strongly interconnected with the teachers’ training narrative, because both are intertwined in the ‘subjective theories’ of professionals (Cuadra-Martínez et al., 2018a,b).

Examining professional narratives and their discontinuities allows not only the identification of factors but also the recognition of the contents and depth of discourses on the agents’ practices. In this way, it is possible to understand the discursive effects of policies on the work of teachers and other educational agents, noting, for example, their potential de-professionalizing effect on some of them.

With respect to training, the interviewees’ narratives highlight the introduction of new Ministry mandates; new demands which make it necessary to possess certain resources. In this context, it is worth anticipating the idea that schools respond to guidelines imposed by a hyper-vigilant State (Falabella, 2018) by requesting economic, material, and/or professional resources, along with specific training programs that cover areas related to SEL.

In contrast, to understand the commitments of teachers, it is necessary to acknowledge that they are (re)actualized daily, being produced in their professional practice in a situated manner. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the contributions of Cornejo et al. (2021), who show how the socio-affective efforts of the teachers who took part in their study represent a constant process of situated professional learning “that is not acquired in the initial education process (…), with emotional knowledge being constructed in specific contexts upon the basis of mutual experiences that take place over time” (p. 19). This is consistent with the findings presented, where commitments are inextricably associated with the interviewed teachers’ daily efforts to improve their students’ well-being and learning outcomes. As the interviews show, the teachers are aware of their weaknesses and the tools that they need, demanding some of this in the form of continuing education; however, their training narratives often reveal a search for further education in fields or subjects different from their core discipline. This process leads to a differentiation that may derive from the need to produce professional certifications that enable them to compete with each other under a performative market-driven education logic (Falabella, 2018), in contexts where SEL gained great relevance (for example, during the pandemic). In consequence, the interviewees highlight the importance of an initial education process sensitive to these issues. Such an approach may be enriched by the studies conducted by Bächler et al. (2020) on the profiles of initial emotional education in primary teacher education programs, adopting the idea that emotions are common to all teacher education processes, from a holistic, non-purposive point of view, together with the notion of teachers’ emotional work (Cornejo et al., 2021). Developing a pedagogical approach to SEL that is situated and consistent with teacher training is essential, since, as shown by some meta-analyses, SEL programs and initiatives implemented by teachers are more effective for school functioning than those taught by external personnel (Durlak et al., 2011; Domitrovich et al., 2015; Cipriano et al., 2023). Thus, bringing together commitment and training in a way that nurtures teachers’ professional narratives is crucial.

On the other hand, according to the evidence, the application of universal school-based (USB) programs and policies, oriented to the entire community, positively favors school and classroom climate, and the latter has a circular relationship with academic achievement (Cipriano et al., 2023). In addition, the school climate factor has a great impact on the educational experience of minorities (Cipriano et al., 2023); a good classroom climate results in an environment conducive to inclusion. Taking this aspect seriously, the concern of advancing in SEL policies, but also in aspects that manage to intertwine commitment and training from a pedagogical approach, which is not individualizing or psychologizing, is urgent to address current issues related to inclusion and the formation of a culturally responsive pedagogy (Barnes and McCallops, 2019).

As for school climate coordinators and educational psychologists, it is necessary to pay attention to the continuities and discontinuities connected to the values ascribed to SEL in schools. In line with the observations of Forman et al. (2008), the values and efforts shared and coordinated in connection with SEL are relevant factors for the successful implementation of specific programs that target this dimension of learning. The present study revealed that, under a market-driven approach, regardless of the amount of resources allocated to this issue, the outcome will not be positive if there continue to exist discontinuities between personal and administrative/institutional efforts and commitments. In addition, it is worth taking into account the illuminating study by Ascorra et al. (2019) on the institutional enactment of school climate policies, which shows how, in contexts of high-stakes accountability, two contradictory but juxtaposed approaches to school climate ultimately coexist: a punitive and a formative one.

With respect to the educational psychologists interviewed, it is necessary to recognize the role of the pandemic in the urgent investments that schools made in the mental health domain, where EPs tend to be highly valued by their communities. Yet, despite the importance of the recognition of the role of these actors in the educational field, it is necessary to note that discourses about emotions in education are grounded in mental health discourses (Toledo and Bonhomme, 2019), leading some authors to warn of the risks posed by the growth of therapeutic education or therapization of the education (Ecclestone, 2012; Bonhomme and Schöngut-Grollmus, 2023). Likewise, it is necessary to examine in more detail the complexity that psy discourses introduce into the educational field, under an ethos of vulnerability (Ecclestone and Brunila, 2015), and the types of subjectivation that these disciplines bring into educational practices (Apablaza, 2017). In addition, work should continue to be done to understand how languages derived from psychological and therapeutic logics color the professional efforts of educational agents, as well as the emergent association between different sets of discourses and practices. To do so, researchers must examine the narrative output of professionals’ practices surrounding the emotional dimension of learning, as well as the shared educational horizons of two disciplines such as teaching and psychology, in order to determine the disciplinary and political implications of key factors such as training and commitment for the professionalization of educational agents in this area.

This research provides evidence about the contents that express the narrative discontinuities in the study of the implementation and enactment of SEL policies in Chile. The results manage to deepen and investigate the characteristics of an aspect that have been a crucial factor for studies on the implementation of SEL policies: the way in which the commitments and discursive values are aligned among different educational actors concerning the development of social–emotional learning in schools (Forman et al., 2008; Langley et al., 2010; Collie et al., 2011, 2015; Sun, 2015; Anyon et al., 2016; Barnes and McCallops, 2019; Exner-Cortens et al., 2019).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Universidad Alberto Hurtado Ethics Committee: Verónica Anguita, Daniella Carrazola, Diego García, René Cortínez, José Gaete, Natalia Hernández, Marcela Perticara, Alejandra Morales, Daniela (external member). Paula Dagnino has excused herself from participating in this evaluation because she belongs to the same faculty as the principal investigator. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MR: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investivación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile, through the National Doctoral Scholarship No. 21190581, awarded to the lead author AB, to pursue his doctoral studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abramowski, A. (2015). “La vocación como categoría afectiva fundante de la docencia como profesión” in Pretérito indefinido. Afectos y emociones en las aproximaciones del pasado. eds. C. Macón and M. Solana (Buenos Aires: Título), 67–94.

Abramowski, A. (2022). “‘Darlo todo’. La entrega incondicional como componente fundante del magisterio argentino y sus resonancias en el siglo XXI” in Política, afectos e identidades en América Latina. eds. L. Anapios and C. Hammerschmidt (Buenos Aires: CLACSO), 383–404.

Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación. (2017). Informe Técnico 2017. Indicadores de Desarrollo Personal y Social (IDPS) medido a través de cuestionarios. Available at: http://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/Informe_tecnico_IDPS_2017.pdf

Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación. (2021). Diagnóstico integral de aprendizajes. Available at: https://diagnosticointegral.agenciaeducacion.cl

Anyon, Y., Nicotera, N., and Veech, C. (2016). Contextual influences on the implementation of a schoolwide intervention to promote students’ social, emotional and academic learning. Child. Sch. 38, 81–88. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdw008

Apablaza, M. (2017). Prácticas ‘Psi’ en el espacio escolar: Nuevas formas de subjetivación de las diferencias. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo Soc. 16, 52–63. doi: 10.5027/psicoperspectivas-vpl16-issue3-fulltext-1063

Ascorra, P., Carrasco, C., López, V., and Moralez, M. (2019). Políticas de convivencia escolar en tiempos de rendición de cuentas. Archivos Anal. Polít. Educ. 27, 1–24. doi: 10.14507/epaa.27.3526

Bächler, R., Meza, S., Mendoza, L., and Poblete, O. (2020). Evaluación de la formación emocional inicial docente en Chile. Rev. Estudios Experiencias Educ. 19, 75–106. doi: 10.21703/rexe.20201939bachler5

Ball, S., Maguire, M., and Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy. Policy enactments in secondary schools. London and New York: Routledge.

Barnes, T., and McCallops, K. (2019). Perceptions of culturally responsive pedagogy in teaching SEL. J. Multicult. Educ. 13, 70–81. doi: 10.1108/JME-07-2017-0044

Barría-Herrera, P., Améstica-Abarca, J., and Miranda-Jaña, C. (2021). Educación socioemocional: discutiendo su implementación en el contexto educativo chileno. Rev. Saberes Educ. 6, 59–75. doi: 10.5354/2452-5014.2021.60684

Bisquerra-Alzina, R., and Pérez-Escoda, N. (2007). Las competencias emocionales. Educación 10, 61–82. Avalaible at: http://www.uned.es/educacionXX1/pdfs/10-03.pdf

Bonhomme, A. (2021). La teoría vygotskyana de los afectos ante el capitalismo emocional en la escuela. Interdisciplinaria 38, 85–100. doi: 10.16888/interd.2021.38.1.6

Bonhomme, A., and Schöngut-Grollmus, N. (2023). Terapización y emociones en la puesta en práctica de políticas de Aprendizaje Social y Emocional en la escuela. Psicoperspectivas Individuo y. Sociedad 22, 1–13. doi: 10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol22-Issue1-fulltext-2765

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, A., and Maguire, M. (2018). Doing without believing – enacting policy in the English primary school. Critical Stud. Educ. 61, 433–447. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2018.1500384

CASEL. (2023a). Fundamentals of SEL. Available at: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/ (Accessed October 5, 2023)

CASEL. (2023b). Our history. Available at: https://casel.org/about-us/our-history/ (Accessed October 5, 2023)

Cipriano, C., Strambler, M., Naples, L., Ha, C., Kirk, M., Wood, M., et al. (2023). The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: a contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Dev. 94, 1181–1204. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13968

Collie, R., Shapka, J., and Perry, N. (2011). Predicting teacher commitment: the impact of school climate and social-emotional learning. Psychol. Sch. 48, 1034–1048. doi: 10.1002/pits.20611

Collie, R., Shapka, J., Perry, N., and Martin, A. (2015). Teacher’s believes about social-emotional learning: identifying teacher profiles and their relations with job stress and satisfaction. Learn. Instr. 39, 148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.06.002

Cornejo, R., Etcheberrigaray, G., Vargas, S., Assaél, J., Araya, R., and Redondo-Rojo, J. (2021). Actividades emocionales del trabajo docente: un estudio de shadowing en Chile. Quaderns Psicol. 23, e1689–e1626. doi: 10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1689

Cuadra-Martínez, D., Castro, P., and Juliá, M. (2018a). Tres saberes en la formación por competencias: Integración de teorías subjetivas, profesionales y científicas. Formación Universitaria 11, 19–30. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062018000500019

Cuadra-Martínez, D., Salgado, J., Lería, F., and Menares, N. (2018b). Teorías subjetivas en docentes sobre el aprendizaje y desarrollo socioemocional: Un estudio de caso. Revista Educ. 42, 250–271. doi: 10.15517/revedu.v42i2.25659

Domitrovich, C., Pas, E., Bradshaw, C., Becker, K., Keperling, J., Embry, D., et al. (2015). Individual and school organizational factors that influence implementation of PAX good behavior game intervention. Prev. Sci. 16, 1064–1074. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0557-8

Durlak, K., Weissberg, R., Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., and Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a Meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Ecclestone, K. (2012). From emotional and psychological well-being to teacher education: challenging policy discourses of behavioural science and ‘vulnerability’. Res. Pap. Educ. 27, 463–480. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2012.690241

Ecclestone, K., and Brunila, K. (2015). Governing emotionally vulnerability subjects and ‘therapisation’ of social justice. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 23, 485–506. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2015.1015152

Esen-Aygun, H., and Sahin-Taskin, C. (2017). Teacher’s views of social-emotional skills and their perspectives on social-emotional learning programs. J. Educ. Pract. 8, 205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103813

Exner-Cortens, D., Spiric, V., Crooks, C., Syeda, M., and Wells, L. (2019). Predictors of healthy youth relationships program implementation in sample of Canadian middle-school teachers. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 35, 100–122. doi: 10.1177/0829573519857422

Falabella, A. (2018). “La seducción por la hipervigilancia: El caso de la educación escolar chilena (1973-2011)” in Privatización de lo público en el sistema escolar. Chile y la agenda global de la educación. eds. C. Ruiz-Schneider, L. Reyes-Jedlicki, and F. Herrera-Jeldres (Santiago: LOM Ediciones), 163–187.

Forman, S. G., Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Crowe, M., and Saka, N. (2008). Evidence-based interventions in schools: developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. Sch. Ment. Heal. 1, 26–36. doi: 10.1007/s12310-008-9002-5

González-Rey, F. (2000). El lugar de las emociones en la constitución social de lo psíquico: El aporte de Vigotski. Educ. Soc. 21, 132–148. doi: 10.1590/S0101-73302000000200006

Hoffman, D. (2009). Reflecting on social emotional learning: a critical perspective on trends in the United States. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 533–556. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325184

Langley, A., Nadeem, E., Kataoka, S., Stein, B., and Jaycox, L. (2010). Evidence-based mental health programs in school: barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Mental Heatl 2, 105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1

Le Breton, D. (2013). Por una antropología de las emociones. Revista Latinoamericana Estudios Sobre Cuerpos Emociones Soc. 4, 69–79. Available at: https://www.relaces.com.ar/index.php/relaces/article/view/239

Ley 20370 (2009). Ley General de Educación. Gobierno de Chile. Available at: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1006043&idParte

Mayer, J. D., and Salovey, P. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 9, 185–211. doi: 10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Menéndez, D. (2018). Aproximación crítica a la Inteligencia emocional como discurso dominante en el ámbito educativo. Rev. Española Pedag. 76, 7–23.

Ministerio de Educación. (2019). Política Nacional de Convivencia Escolar. Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

Ministerio de Educación. (2020). Claves para el bienestar. Bitácora para el autocuidado docente. Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

Ministerio de Educación. (2021). Formación Integral y Convivencia Escolar. Available at: http://convivenciaescolar.mineduc.cl/set-de-convivencia-escolar-y-aprendizaje-socioemocional/ (Accessed October 20, 2021)

Muñiz, R. (2020). Muddy sensemaking: making sense of socio-emotional skills amidst a vague policy context. Educ. Policy Analysis Archives 28, 1–28. doi: 10.14507/epaa.28.5235

Murray, M. (2018). “Narrative data” in The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection. ed. U. Flick (London: SAGE Publications), 264–279.

Nielsen, B. L., Laursen, H. D., Reoil, L. A., Jensen, H., Kozina, A., Vidmar, M., et al. (2019). Social, emotional and intercultural competencies: a literature review with a particular focus on the school staff. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 410–428. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1604670

OCDE. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/db1d8e59-en

OECD (2016), Habilidades para el progreso social: El poder de las habilidades sociales y emocionales. Paris: UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Pekrun, R., and Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). International handbook of emotions in education. New York: Routledge

Pérez-González, J. C. (2012). “Revisión del Aprendizaje Social y Emocional en el mundo” in ¿Cómo educar las emociones? La Inteligencia Emocional en la infancia y la adolescencia. ed. R. Bisquerra (Barcelona: Hospital Sant Joan de Déu), 56–69.

Rockwell, E. (2005). “La apropiación, un proceso entre muchos que ocurren en ámbitos escolares. En Sociedad Mexicana de Historia de la Educación” in Memoria, conocimiento y utopía. Anuario de la Sociedad Mexicana de Historia de la Educación. Número 1 (Barcelona: Ediciones Pomares), 28–38.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Aprendices del pensamiento. El desarrollo cognitivo en el contexto social. Buenos Aires: Paidós

Roulston, K., and Choi, M. (2018). “Qualitative interviews” in The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection. ed. U. Flick (London: SAGE Publications), 233–249. doi: 10.4135/9781526416070.n15

Schöngut, N. (2015). Perspectiva narrativa e investigación feminista: posibilidades y desafíos metodológicos. Psicol Conocimiento Sociedad 5, 110–148. Avalaible at: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1688-70262015000100006&lng=es&tlng=es

Schöngut-Grollmus, N., and Pujol, J. (2015). Relatos metodológicos: difractando experiencias narrativas de investigación. Qual. Soc. Res. 16, 1–24. doi: 10.17169/fqs16.2.2207

Seligman, M. E. (2019). Positive psychology: a personal history. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095653

Sorondo, J. (2023). La Educación Emocional en el Marco de las Políticas Neoliberales: Reflexiones Teórico-Epistemológicas a Partir de un Estudio Exploratorio sobre Discursos de Educadoras/es en Secundarias del AMBA. Archivos Analíticos Políticas Educativas 31, 1–19. doi: 10.14507/epaa.31.7717

Spohrer, K. (2021). Resilience, self-discipline and good deeds – examining enactments of character education in English secondary schools. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 32, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2021.2007986

Sun, J. (2015). Conceptualizing the critical path linked by teacher commitment. J. Educ. Adm. 53, 597–624. doi: 10.1108/JEA-05-2013-0063

TCPS2 (2018). Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. Ottawa: Secretariat on Responsible Conduct of Research

The World Bank (2015). Emotions are worth as much as knowledge. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/06/22/las-emociones-valen-tanto-como-los-conocimientos

Toledo, C., and Bonhomme, A. (2019). Educación y emociones: coordenadas para una teoría vygotskyana de los afectos. Psicol. Escolar Educ. 23:7. doi: 10.1590/2175-353920190193070

Toro-Blanco, P. (2018). Una nueva oficina en el liceo: la instalación de los orientadores como política educacional en Chile (c.1946-c.1953). Rev. Historia Caribe 13, 283–315. doi: 10.15648/hc.33.2018.11

Toro-Blanco, P. (2019). Entre modulaciones de afecto y autoridad en episodios de la historia de la educación chilena (c.1820-c.1950). Rev. Historia Educaçao 23, 1–23. doi: 10.1590/2236-3459/88795

UNESCO (2020). Promoción del bienestar socioemocional de los niños y los jóvenes durante la crisis. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373271_spa

Vincent, C. (2019). Cohesion, citizenship and coherence: schools’ responses to the British values policy. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 40, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2018.1496011

Vincent, C., Neal, S., and Iqbal, H. (2016). Children’s friendships in diverse primary schools: teachers and the processes of policy enactment. J. Educ. Policy 31, 482–494. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2015.1130859

Vygotsky, L. S. (1930/2014). “Sobre los sistemas psicológicos” in Obras Escogidas. eds. I. Tomo and L. S. Vygotsky (Madrid: Antonio Machado), 71–93.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1931/2012). “Historia del desarrollo de las funciones psíquicas superiores” in Obras Escogidas. Tomo III. ed. L. S. Vygotsky (Madrid: Antonio Machado), 10–340.

Keywords: social and emotional learning, commitment, training, teacher professionalization, narrative approach, educational policy enactment

Citation: Bonhomme A and Rojas MT (2024) Commitment and training: professionalization narratives in the implementation of social and emotional learning policies in Chilean schools. Front. Educ. 8:1322323. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1322323

Edited by:

Silvia Cristina da Costa Dutra, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by:

María Lorena Alonso, Universidad Nacional de Villa María, ArgentinaCarlos Ossa, University of the Bío Bío, Chile

Copyright © 2024 Bonhomme and Rojas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alfonso Bonhomme, YWJvbmhvbW1lQHVhaHVydGFkby5jbA==

Alfonso Bonhomme

Alfonso Bonhomme María Teresa Rojas2

María Teresa Rojas2