- 1Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music and Performance, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Performing Arts, Faculty of Education, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

The teaching of jazz history in tertiary institutions has historically focussed on the “great men” of jazz (Whyton, 2010), with jazz historiography giving scant recognition to female-identifying musicians (Rustin and Tucker, 2008). The historicising of certain individuals and their music is fundamental to understanding jazz, yet it silences female and gender non-binary voices, overshadowing the roles they played in the evolution of the genre. This study aims to deepen our understanding of the experience of students engaging with jazz history in the 21st century. Halberstam and Halberstam’s (2005) theory of queer time and disruption serves as the primary framework for analysing shifts in teaching and learning perceptions concerning hegemonic and male-dominated narratives in jazz history. To understand the experiences and perspectives of those directly involved in jazz history pedagogy this research draws on an education-focused, polyethnographic approach utilising data derived from self-selected student research topics, student surveys, and teacher interviews. Our findings highlight both the shifting discourse within tertiary education, teaching experiences and the interwoven attitudes of students, reflecting on how these dialogues came to impact and shape the other. The study provides implications for how jazz education may continue to evolve in both attitude and enlightened access in the education of jazz learners. The objective of this paper’s outcomes is to inform the translation of more diversified narratives in tertiary jazz pedagogy and music education more broadly.

Introduction

The contesting of historical narratives is not a new phenomena. The authors of this article have come to understand the complexities of historical narratives as educators and researchers at an Australian University in a settler-colonial context. We have learnt to be critical about history from First Nations’ long-running calls for truth-telling in regard to Indigenous perspectives of colonisation, and key events in our lifetimes such as the Australian “history wars” of the 1990s1 (Barolsky, 2023; Scates and Yu, 2022). This need for criticality has also been demonstrated in relation to jazz histories through decades of feminist historiography (Ruskin and Tucker, 2008; Tucker, 1999) and jazz educational scholarship (Prouty, 2018; Whyton, 2006). Additionally, as educators in an Australian context and advocates of non-hegemonic voices, we grapple with the field of critical jazz studies being Northern hemisphere focussed and dominated by African-American or Eurocentric perspectives. These drivers lead us to question how history is presented, which is the primary purpose of this study.

A critical lens in an Australian jazz context necessitates fresh reconceptualisations that help us understand our own “glocal”2 approach to jazz history (Nicholson, 2014), which is part of growing scholarship in critical Australian jazz studies (De Bruin, 2016; Phipps, 2022; Whiteoak, 2022). The socio-musical systems of “improvisative musicality” (Lewis, 1996), situated in environments shaped by persistent settler colonisation and distinct geopolitical histories of Australia, demand what is referred to as an “Austrological” lens (Kellett et al., 2024)3. What we, the authors, are aiming to do as jazz educators and researchers is part of a movement4 in Australia that strives to adopt more culturally relevant, responsive, and inclusive approaches to performance, education and scholarship. This includes responding to students’ demands for their educational experience to reflect the diversity of real life beyond the academy (Gale and Parker, 2017; Waling and Roffee, 2018). Such demands create an impetus to question the function and form of the historical narratives that have been central to our practice as Australian educators, researchers and performers. In our view, while any research concerned with inclusion is fundamentally a social justice concern, underpinning this inquiry’s social justice agenda is the troubling of how and what we teach about jazz in Australian university classrooms. We attempt to break past silences in a bid to make exclusionary narratives obsolete. To do this, the research seeks to understand the experiences and perspectives of those directly engaged in jazz history pedagogy through an education-focussed, polyethnographic approach.

We proceed from the standpoint that jazz historiography is not inclusive. Within the literature, there is at times, subtle and at other times very explicit, recognised bias in favour of male-identifying jazz practitioners and authors (Enstice and Stockhouse, 2004; Hall and Burke, 2022; McKeage, 2014; Reddan, 2022; Rustin and Tucker, 2008; Teichman, 2020; Wehr-Flowers, 2006). Research repeatedly argues women and minority groups are not only excluded from the jazz canon, but also jazz scholarship (Brown, 1991; Hall and Burke, 2022; McGlone, 2023; McMullen, 2021; Monson, 1995; Rustin and Tucker, 2008), with texts that perpetuate the dominant view of jazz history particularly culpable (Boeyink, 2022; Lawson, 2022; Rustin and Tucker, 2008). For the student of jazz history, this creates a problematic and inaccurate introduction to the world of jazz. For the contemporary teacher of jazz history, it creates a pedagogical challenge that includes a responsibility to critically reassess conventional narratives and resources, countering, augmenting and replacing them with more critically engaged, twenty-first century appropriate perspectives. Typical of these conventional narratives is the “veneration of great men and their achievements” (Hall and Burke, 2022, p. 337), which elevates the typically gendered concepts associated with the “jazzman” to that of prime canonical importance (Early and Monson, 2019; Johansen, 2023; Rustin and Tucker, 2008; Whyton, 2010). For instance, Tony Whyton (2010) identifies myths underpinning the jazz canon consisting of clear tropes5 that permeate nearly all mainstream general jazz history texts, evident in the tendency to replicate hegemonic perspectives (DeVeaux, 1991, 1997, 2002; Gioia, 2011; Gridley, 1992, 2000, 2007; Giddins and DeVeaux, 2009; Shipton, 2007; Tirro, 1993) and an adherence to a particular chronological construction of a historical jazz narrative (Stow and Haydn, 2012).

While a chronological model remains valuable for sociocultural contextualisation of certain events, we argue that in the teaching and learning of jazz, conventions of chronology delimits the application of critical thinking that is associated with research-led tertiary studies by overemphasising a particular sequence of historical events (Boeyink, 2022; McMullen, 2021) and therefore can be problematic in regards to inclusion. The male-centred construct of many chronological histories sidelines select voices, resulting in “clear gender differences with how jazz is and has been portrayed and taught in higher education” (Reddan, 2022 p.255) that lead to inconsistencies and biases in students’ understanding, resulting in misconceptions of who was present and what they contributed. This article discusses how the researchers have gone about teaching jazz history in a more inclusive way by disrupting gendered historical narratives. The next section explains the queer theory that has guided the investigation’s critical reflection.

Theoretical framing

Inspiration may be found in the rejection of chrononormativity that queer time affords. Halberstam and Halberstam’s (2005) conceptualisation of queer time is particularly useful as an opportunity to rethink how time, when seen as a construct, produces illusions of what it means to become an adult. Queer lives cause us to question how time is understood with diverse temporal logics, in the absence of hetrosexual lifespan milestones as an expectation, such as entering a profession, homeownership, and settling down to raise children with a life partner.

I try to use the concept of queer time to make clear how respectability, and notions of the normal on which it depends, may be upheld by a middle-class logic of reproductive temporality. And so, in Western cultures, we chart the emergence of the adult from the dangerous and unruly period of adolescence as a desired process of maturation; and we create longevity as the most desirable future, applaud the pursuit of long life (under any circumstances), and pathologize modes of living that show little or no concern for longevity (Halberstam, p. 17).

This line of questioning, when applied to jazz history, highlights the way temporality is used to reproduce and normalise particular hierarchies and power dynamics. For instance, temporal frames exist around what is perceived as the influence of one jazz style on another with linear causal links, and the necessity to comprehend the lives of these style’s ancestors as the means to legitimate one’s own “jazz capital” (Buscatto, 2021). In other words, the maturation of a jazz musician is authenticated by their ability to illustrate through knowledge and skill that they have mastered the music of their ancestors. This process of legitimation is usually enacted through the comprehension of a particular sequence of events marked by particular elders worthy of emulation—usually the “fathers” of jazz.

At the risk of being overly reductive of Halberstam’s effort “[…] to rethink the practice of cultural production, its hierarchies and power dynamics, its tendency to resist or capitulate” (p.20), this research extends queer time beyond human lifespan temporality and applies it as motivation to rethink the temporal framing of jazz history within higher education. The overarching aim is to disrupt the sanctity of presenting jazz history with a chronological logic that is wedded to the valorisation of canonical masculinist narratives in jazz education. The questioning of temporality with queer thinking is also a strategy for deeper self-reflexivity around the intersection of researchers’ positionalities with personal pedagogies. The research analyses the experience of jazz history in our current Australian higher context from both student and teacher perspectives, by questioning education (higher education) how teaching and learning jazz history can support gender diversity through the disruption of jazz historiographies.

Background to the study

In late 2019, the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music (SZCSoM) at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, signed The Keychange Pledge with the goal to “accelerate change and create a better more inclusive music industry for present and future generations”6. The Keychange pledge emphasised the importance of achieving a 50:507 gender balance in staffing, guest artists, and compositions performed. This initiative also prompted reflection and re-examination of pedagogical materials at SZCSoM, including those used in the Jazz History unit of study. Through this reflection, it became clear that there was insufficient representation of female-identifying artists and authors in jazz literature (Canham et al., 2022), which then manifested in readings and material used for teaching. For instance, a review of 56 text-based “recommended resources” revealed only six of them included at least one non-male author.

Following the Keychange pledge, the jazz history unit at SZCSoM engaged in a critical re-examination of teaching and learning materials from a gender perspective, which is the subject of the later discussion. From its initiation in 2015, the presentation of content in this unit was chronological, modelled on the dominant published jazz history texts (Giddins and DeVeaux, 2009; Gioia, 2011; Shipton, 2007; Tirro, 1993), notably all written by male-identifying authors. The choice of these texts as foundations for the unit grew from the practical needs of devising unit content that covers 100 years of musically diverse practice, while navigating the time constraints inherent in coordinating learning across a total of 48 h of teaching to deliver the unit. This re-examination involved in-class discussions with students and extensive teacher research, culminating in a collective critique of the limited gender representation in jazz historiography. Following this critical engagement, more tangible actions were implemented over the next 4 years (2019–2023), including a review of weekly listening lists and featured in-class audio-visual examples, with updates made to promote greater gender diversity. Additionally, the materials used in the online learning platform were changed to include a more balanced gendered visual representation.

A review of readings for the unit was also made at this time, which resulted in the inclusion of additional work by non-male authors, noting that further work was needed to achieve greater gender balance in 2020. One challenge that was noted at the time was the dominance of male authors writing about jazz history. While the unit included readings from seminal texts by authors like Ingrid Monson (1995) and Sally Placksin (1982), it was more challenging to simultaneously reflect gender diverse authorship and the chronological structure featured in the unit. This challenge highlighted the need to reevaluate the chronological approach to create greater space for non-male identifying authors. Publications by women authors such as, Pellegrinelli (2008), Scully (2016), McMullen (2012, 2021), McGee (2011), Rustin (2005) and Feldstein (2005) expose the male hegemony within traditional jazz history texts, suggesting a need to reevaluate chronological approaches. The following sections explain how and why these pedagogical actions emerged and what was learnt.

Methodology and methods

This research story conveys how a jazz history unit in an undergraduate institution has evolved over 5 years in three phases, including the rationale of how and why actions were made. The study employs a range of qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the perspectives of both staff and students regarding the changes made to unit guides, reading lists, in-class material and online learning platforms.

The investigation occurred in three main phases utilising the following methods:

Phase 1

• Student SETU feedback8 and a teacher generated student survey was analysed, providing useful insight into student perspectives. These are also integrated with teacher perspectives in phase 2.

• Student essays9 were thematically analysed, demonstrating the effect of pedagogical changes and disruptions to a chronological approach to jazz history pedagogy.

Phase 2

• A polyethnographic investigation of teacher experience was conducted using a critical self-reflexive dialogue between researchers to evaluate the what and why of jazz history. The results of these conversations were analysed, identifying salient themes and challenges, and are presented in the ‘Research Story’ section.

Phase 3

• Meaningful pedagogical actions were identified and implemented as an outcome of Phase 2

Polyethnographic narratives

Polyethnography11 is based on the reflection and interpretation of a phenomenon as experienced by researchers, which involves a collaborative process between the researchers as participants (Olt and Teman, 2019; Pasyk et al., 2022). A polyethnographic approach was taken in the second and third phases, which began with author Clare Hall (who did not teach into the unit) facilitating conversations through critical incident interviews with individuals who contributed to the teaching of jazz history; authors Johannes Luebbers, Robert Burke and Michael Kellett. Individual interviews were then collectively analysed and reflected upon by the group, identifying common themes and challenges. This approach of individual interviews followed by collective analytical reflection is a key aspect of our methodology. This created an intertextual dialogue between what we collectively understand as researchers, our individual experiences as learners and educators, and how these perspectives inform the research. Through this polyethnographic approach, both subjectivity and objectivity are positioned as central and inevitable, enabling a multiperspective understanding of lived experience (Hegelund, 2005).

Positionalities of the authors

A notable commonality among the teaching and research team is that none are historians. Our jazz history expertise instead emerges from practice-based backgrounds in performance, composition and education. The following are brief descriptions of each authors’ funds of knowledge in jazz history teaching and learning, illuminating what each author brings to the research. Notably, all the authors are Australian born and acknowledge the nation’s settler-colonial history. These positionality statements12 inform later discussion, and help reveal how generational attitudes and age-related differences purposefully interact with differences in positionality. They highlight the value of diverse knowledge bases and perspectives on authenticity, which are embraced rather than rejected.

Robert Burke

I am a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered male and an Associate Professor of Jazz and Improvisation at Monash University, Australia. I acknowledge coming from a university-educated, middle-class family—that afforded me private schooling and music tuition—introduces certain biases that I am conscious of in my teaching and research in my teaching. My journey in jazz education began in 1980 as a performance student, leading to a teaching role at a tertiary institution in 1996. Since this time, I have maintained dual roles as both a non-traditional (practice-based) and traditional research academic. From 2021 to 2024, I served as the unit coordinator and lecturer of jazz history. This wholistic background provides me with a longitudinal perspective on the gendered changes occurring in jazz education and the broader sector, which I bring to this paper. As a musician and researcher from Australia, I am committed to advocating for meaningful change in inclusion and diversity within the jazz and improvisation sector. I action this commitment as an ally and advocate through my roles as a teacher, researcher, and performer.

Clare Hall

I am a cisgendered female and Senior Lecturer in Performing Arts in the Faculty of Education, Monash University. Raised in rural areas in farming regions, I have strong ties to the land and waterways of the places that know me, which underscores everything I do. My cultural ancestry is from England, Scotland, and Ireland as a descendant of settler-colonisers with ruling and working class heritage. As the first in my family to attend university, my tertiary studies in music performance, majoring in classical viola, was revered as a valuable and privileged career path. Musical mothering is now at the heart of how I sole parent my daughter to pass on my family script, with performing musician ancestors on all sides of the family lines, including vaudeville performers in the early jazz era of Australia. I identify as a neurodivergent, post-classical improvising musician-educator who has come to the sociology of music education following a career in school and community music teaching. Understanding the conditions that enable meaningful and diverse participation in music has been a research focus since I began lecturing in higher music education in 2008. I bring expertise in feminist studies in gender and decolonising practices in music education, along with more than 30 years experience as an avid audience member and advocate for the Australian jazz music scene. My research, education and performance practice integrates my professional and personal commitments to equity, inclusion and diversity in music education through socially engaged music-making.

Michael J. Kellett

I am a composer, improviser, sound artist and doctoral candidate in practice-based methodologies at Monash University, Australia. My education in tertiary jazz began in 2014, completing my honours year in 2018, and starting my PhD in late 2019. I commenced tutoring into the Jazz History unit in 2021, coinciding with a period of transition which emphasised gender perspectives within course materials. My experiences of teaching and learning are framed by my background as a white, cisgendered, queer male who identifies as neurodivergent. Growing up in an Australian lower-middle class family, with an intergenerational history of early-mid twentieth century European migration, I was the first in my family to attend university. A vocation in music was both venerated and disapproved by different factions within my family. These aspects of my identity of both belonging and traversing against the grain of societal and familial norms have motivated my belief to critically examine accepted narratives, and in doing so respect all lived experiences. In educational settings, I seek to amplify student voices—and by virtue, disparate experiences and understandings—so that teaching becomes a learning opportunity that empowers inclusive music pedagogy. To date my research has focused on untangling relational understandings of music composition and improvisation, and theorising decolonial critiques of Australian jazz historiography.

Johannes Luebbers

I am a composer, pianist, researcher and educator, creating and teaching across a range of musical idioms. My perspective as both teacher and learner is inevitably influenced by my experiences as a white, cisgendered, heterosexual male, and the privilege this affords me. I am also a 1st generation Australian on one side of my family, and 3rd generation on the other, with migration from Germany and Italy respectively, providing mixed perspectives on what it means to belong. My appearance and my name tell different stories, and get different reactions. Social justice features strongly in the vocational choices of my family and their complex histories inform my own passion for fairness and inclusion. I am a Lecturer at the School of Music, Monash University and completed my undergraduate studies in 2005, majoring in jazz arranging and composition. Since then, I have contributed to the development and delivery of a jazz history unit at two large Australian universities, coordinating the unit that is the focus of this research from 2017 to 2020 and leading further development of content and assessment. I am committed to the transformational potential of education and believe an ethical and inclusive experience of jazz history for students is essential to the development of an ethical and inclusive jazz sector.

These author positionality statements recognise the varying degrees of power and privilege that have helped us understand how these factors might influence the education of students, which intersects with the educational architecture and principles of our university. In addition to these broad positionality statements, there exists a particular positionality around each authors’ experience of jazz history as a learner. The relatively diverse educational and socialising experiences relating to jazz history have generated particular relationships to the canon and have, therefore, produced differing pedagogical perspectives. Robert Burke completed their undergraduate studies in the 1980s during which a dedicated jazz history unit was not included in the curriculum. The core of their jazz education came in the form of an autodidactic approach, immersing themselves in the history of jazz through listening (records, radio and live performances), and performing music that was considered progressive, contemporary jazz at that time, in contrast to mainstream American neoclassicism. In contrast, Johannes Luebbers studied jazz in a tertiary setting in the early 2000’s, completing a series of compulsory jazz history units that focussed on chronological musical styles and key figures, with a strong emphasis on listening and no notable focus on gender as a theme. The most recent graduate from a tertiary music course, Michael Kellett studied at Monash University—the institutional home of this research—and completed the unit that is the subject of this research in 2016, bringing a valuable perspective as both teacher and recent learner. The iteration of this unit that Michael completed was also presented chronologically, with a strong emphasis on listening, but with greater a focus on supporting academic literature than Johannes experienced. Like Robert, Clares’s jazz history education was informal and driven by immersion as an avid audience member in the local jazz music scene.

The impact of these generational differences manifests in each jazz educators’ relationship to the notion of a canon and the perceived importance of chronology. For Robert, the lack of a structured jazz history educational experience results in a perception that something was missed out on, which in turn leads to an attachment to the inclusion of a chronological canon—even if the work included in it is challenged in other ways. In contrast, having experienced a chronological jazz history education has led Johannes and Michael to challenge its prioritisation and question whether other pedagogical approaches might lead to richer understandings. Interestingly, despite perceiving value in a chronological presentation Robert has been the driver of innovation away from this model, taking what was previously a purely chronological progression of content and adding a number of weeks that are more thematically focussed on socio-cultural issues and theory, demonstrating an interest in challenging norms and innovating pedagogy despite the inner tension this might generate demonstrating an interest in challenging norms and innovating pedagogy, despite the inner tension this might generate.

Research story

Phase 1: understanding student voice

Student feedback on the teaching and their learning experience was a launchpad for the study, both reinforcing and revealing perspectives around the importance of explicitly addressing gender and intersectionality in the jazz history unit. The first phase of the research began with critical questions regarding the degree of inclusivity and effectiveness of jazz history teaching and learning at this university. While this process of questioning educational practice was ongoing as a part of the authors’ pedagogies, the focus on gender inclusivity in particular occurred incrementally over a five-year period. Pedagogical changes and shifts in teachers’ and students’ actions and thinking were documented through student feedback, collaborative planning, and restructuring unit materials. The following quotes are a sample of the student feedback that represents the kinds of feedback that informed our understanding of their perspectives on gender and intersectionality. For instance, one student highlighted the need for “more focus on the influence of women in the history of Jazz” (student, 2017), reflecting a critique of the existing content, which tended to frame discussions from a predominantly male perspective. Similarly, another student acknowledged the “inclusion of female artists” but expressed concern that non-male identifying artists were not given sufficient prominence, they were “simply added to the standard history” (student, 2022), rather than being central to it. Moreover, some students acknowledged the critical approach to pedagogy, with one student commenting, “I appreciated that we were not just taught the basic history of jazz but were encouraged to consider who is excluded from this narrative and to challenge or critique historical sources and the lenses through which they are interpreted” (student, 2021). Feedback of this kind emphasised the discrepancies and discord with some of the unit offerings that reinforced the need for pedagogical change.

Student survey

In 2022, we conducted a student exit survey, where second-year undergraduate students emanating from disparate faculties and schools within the university were invited to participate voluntarily. Ethics approval was granted for this anonymous contribution. A sizable majority (approximately two-thirds) of the cohort were completing their Bachelor of Music, many from the jazz performance specialisation. The researchers used Qualtrics as a platform to gather survey data from the n = 70 students, to which there were 27 respondents. The survey consisted of seven questions which included (a) students’ enrolled area of study, (b) students’ study interests within jazz history and (c) their feedback regarding the discussion of gender-related topics and issues within the course content and its delivery. The survey took approximately 10 min to complete. The questions started with an inverted funnel technique (Ikart, 2019) and semi-structured questionnaire which began with closed ended questions and evolved into an open-ended approach, allowing participants to express their personal thoughts and observations about the unit. The resultant data and relevant quotes are embedded in phase 2 below.

Student essays

To evaluate the impact of pedagogical changes made within the five-year period, an analysis was conducted on an essay assessment and the evolving student-selected essay topics. The topics chosen by students provided insight into the relationship between teaching strategies and shifting student interests and engagement. The essay, which was the main assessment for the unit, allowed students to conduct independent research on a topic of their choice. This assignment encouraged them to engage critically with musical, social, cultural, and political issues related to their interest in the storytelling of jazz.

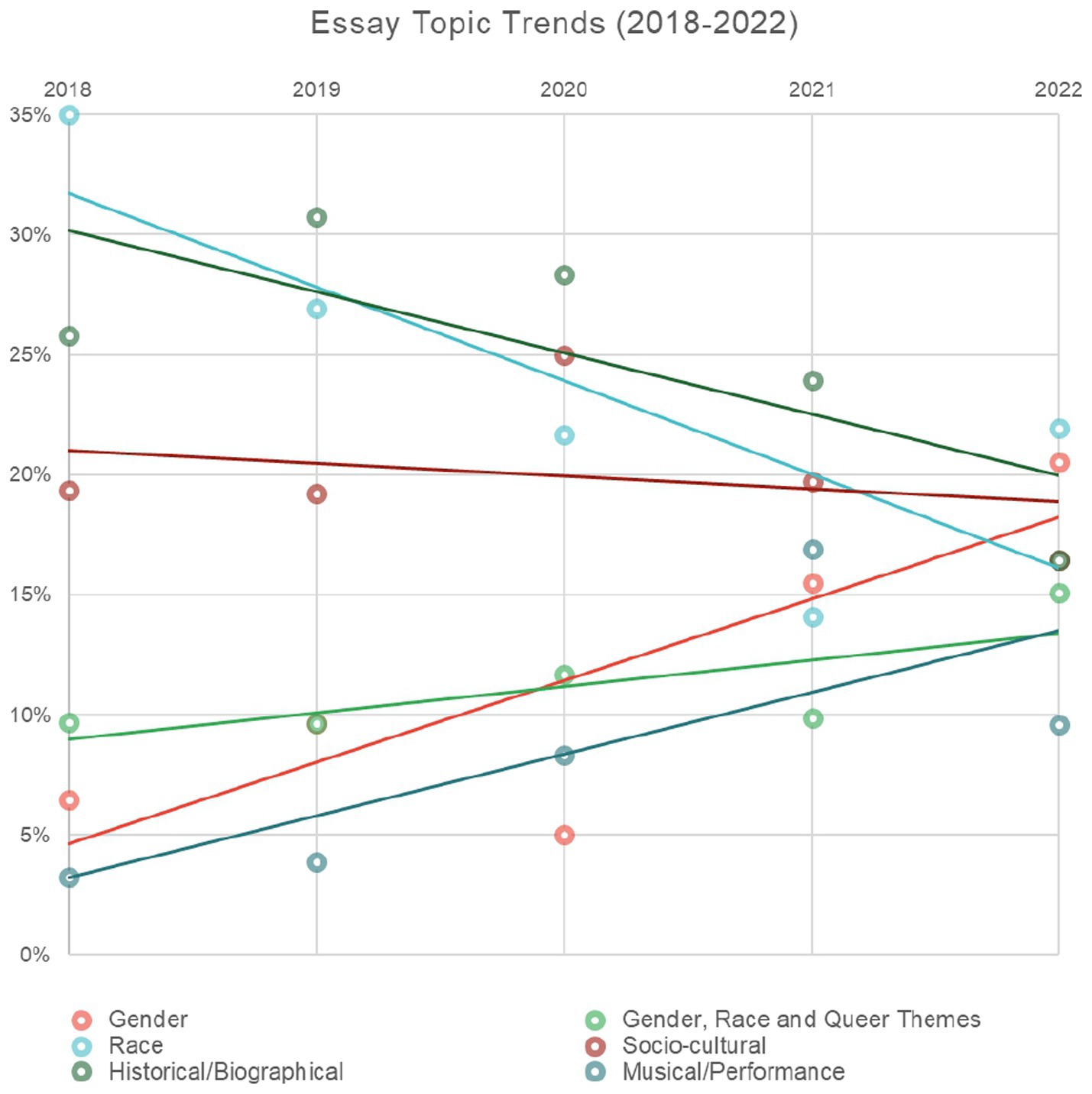

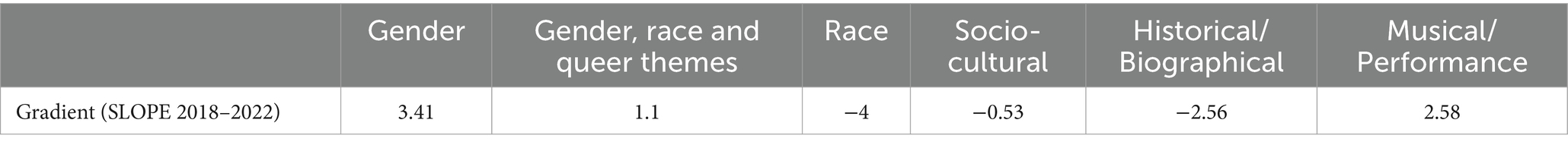

We collated the main themes and stated research questions of each of these essays over the five-year period from the 2018–2022 cohorts (n = 293). As a reference point for cross analysis of essay topics between the authors and further familiarisation with the data set, we included both the title and reference material from each essay in tandem with the theme attributed to each essay in our schema. The pairing of this reference material with the essay topic was essential in determining both the explicit and implicit inquiry the students had articulated in their assignments. In many cases, it was found that the essay title was either too broad, absent or incongruous with the actual argument contained in the body of the essay. This engendered a more accurate and meaningful interpretation of essays into their six possible data codes.

In coding student essays, we applied Terry et al.’s (2017), latent coding technique as a means of capturing the underlying research topic enhancing the identification of “ideas, meanings, concepts, assumptions which are not explicitly stated” (p. 23). We categorised the essays into the six themes that were identified in the assessments criteria, applying what Terry et al. terms a latent approach to data coding: intersectionality, gender, race, musical/performance, historical/biographical and socio-cultural.

The initial coding found that during this period students gradually started to explore intersecting social phenonmena. For example, many student’s focussed their studies on understanding how the sexual, racial and gendered experiences of particular artists informed their contribution to jazz music. This led us to the generation of the first coding theme of the intersection of gender, race and queer themes. The second and third themes centered on gender and race, respectively. The fourth theme identified essays that had music and performance as their exclusive focus for discussion, usually in the form of a transcription and theoretical analysis. The historical and biographical theme was reserved for essays that presented a historical retelling of chronological events or people. Lastly, essays that fell under the socio-political theme were either attempting to address a socio-cultural issue that was not captured in any of the previous themes or that applied socio-cultural theoretical frameworks to their analysis.

The analysis of the data (Figures 1; Table 1) from the essays revealed that the theme of gender increased at the highest rate over the 5 years from 6% in 2018 to 21% in 2022, with a gradient increase of 3.41. The theme of intersectionality also increased from 2018 to 2022 in a statistical range of 10–15%, with a gradient increase of 1.1. In 2022, a themed week of gender was introduced where intersectionality was contextualised through a historical background and positioning in jazz history, and is consistent with the upward trend. Collectively, gender and intersectionality increased year on year with the greatest rate of change among all essay themes at a gradient of 4.51. Although themes of race decreased over the five-years at a gradient of −4.00 it is noted that the discourse of racial identity became more sophisticated and critically immersed in the discussion of many social identities, such as gender and sexuality. Consequently, race was subsumed in a more global discourse which was classed as “intersectionality.” While there has been a marked increase in essay topics around gender and intersectional identity, essays that explored historical retellings consistent with a chronological approach to the jazz canon decreased over the five-year period. This is in concert with the noted increase in students’ critical engagement with historiographical perspectives. Buscatto (2022), Lawson (2022), Hall and Burke (2022) and Rustin and Tucker (2008) have noted that a chronological approach to history preferences masculinity and the gendered hegemony embedded in canonical jazz narratives. To comprehend how these changes in student behaviour and attitudes emerge, it is essential to identify not only changes in literature and student investigations, but how the educators’ backgrounds, experiences, values, pedagogical desires and real-time challenges in the classroom contribute to curating these critical shifts.

In summary, the statistical analysis of essay themes showed significant increases in topics related to gender and intersectionality. It also showed that intersectionality plays an important role in teaching jazz history by challenging conventional, often biased narratives, encouraging students to question13 and broaden their perspectives about jazz across time. The following section analyses how this group of educators went about guiding students’ navigation of jazz history by reflecting on the teaching methods.

Phase 2: teacher voices and perspectives

This phase presents the collective author voice, interlaced with verbatim quotes from the interviews conducted as a part of the polyethnographic methodology that serve to convey the individual experiences of specific teachers. The collective text reflects upon and contextualises these individual perspectives, linking the issues into a bigger picture.

Challenging the literature

As has been established, the presentation of jazz history is dominated by published jazz history texts featuring predominantly male artists and maintaining a chronological presentation of a jazz canon. However, in the past 15 years there has been a renewed interest in research and publication around gender and jazz (Reddan et al., 2023; Rustin and Tucker, 2008; Boornazian, 2022; Johnson, 2000; Buscatto, 2021; Smith, 2014), building on earlier work that highlights and promotes the experiences and contributions of female-identifying and non-binary musicians (Gourse, 1995; Leder, 1985; Placksin, 1982). The more recent research around gender and jazz is typically organised around themes or individuals to elevate lesser-known voices or reveal neglected perspectives, rather than large-scale chronology or historical periods.

The structural differences between these two groups of authors highlight one challenge with adhering to a chronological canon—the majority of literature that supports this pedagogical model only minimally focuses on gender and the contributions of female-identifying and non-binary people. In contrast, the more progressive writing around gender and jazz does not simply convey a chronological history, but instead focuses on issues and themes that implicitly (and explicitly) challenge the hegemony of particular periods and associated iconic male performers as the jazz history.

The conflict created by the perceived need to adhere to chronological narratives while simultaneously aiming for greater representation in both content and authorship is captured by Robert:

Our goal is to attain 50% readings [50% authored by women and gender non-conforming authors] at this stage. But that can be challenging, because at this point in time there’s not enough literature on particular musical styles and periods that have been written by women authors. When we want to focus on a certain chronological topic, we need explicit literature on that subject. We can avoid topics and just feature women authors, but then you are missing out on some key chronological literature written about women by, at this time … men.

This comment in part speaks to the lack of scholarship by female-identifying authors on certain topics within jazz history. Importantly, it also suggests that work by female-identifying authors may not necessarily adhere to chronological, canonical narratives. Robert also notes that maintaining conventional historical narratives leads to the exclusion of womens’ creative voices, as the majority of documented examples are from males, further highlighting the need to disrupt chronologies as a strategy for inclusion. If there is a desire to include diverse voices, one needs to include the topics diverse voices are engaged in, rather than expect those voices to fit existing narratives. Johannes similarly noted that conventional presentation of jazz histories offer a “kind of chronological blow by blow of who played what and when,” pointing to the limited critical thought and challenge to convention inherent to many of these narratives.

Reflecting on the shift in contemporary education around canonical representations, Michael noted that in his experience as a jazz student:

Even before going to university, there was very much a practice where you transcribe a lot, you listen to a lot of players, those that are deemed as the promulgators of the practice. And there’s a lot of idolization and mythologization that goes on around certain players like John Coltrane and Miles Davis…there are parts of their history that get obfuscated, to put them into a nice, neat little package—modern canonical tales of history.

It was not until his fourth year, involving a research project, that Michael began to develop a more critical understanding of “the world of jazz and its men” and to question this orthodoxy. This experience demonstrates that engagement with jazz history precedes any formal unit of study and suggests that the purpose of any such study may be as much to undo problematic stereotypes as it is to expand and enrich student understanding.

The undergraduate experience of Johannes was similarly reflective of canonical convention and uncritical of issues around gender in jazz history:

My experience [of jazz history] as a student was we were sat in a room and we played music from cassette tapes, with overheads, and photocopies from the textbooks that were a decade old. And it was interesting, but it wasn’t super engaging. It was mainly about the music and informing us of people and what the music they made sounded like. I do not want to be too critical of something that happened 20 years ago that I was probably only half invested in at the time. But it did not really prompt us to think critically and discuss things. The model of teaching was very much a lecture that we sat through.

Like Michael, Johannes developed a greater awareness of the need to question the canon later, through postgraduate study. An awareness of how individuals in the present might participate in the construction of a canon, or the perpetuation of a problematic historiography, was not developed through the study of jazz history.

I do not think I was aware [of our participation in the construction of history or a jazz canon] at all. The way it was presented to us it did not contextualise us as students in Australia as a part of jazz history… Whether we were perpetuating institutional problems or anything like that was not discussed, and I was not conscious of that. I do not think my peers were that conscious. Although, you know, I say that but I am sure there were women in our course that were more conscious of things. That wasn’t something that was explicitly discussed though.

In 2023, following cultural phenomena like the #MeToo movement and an increased interest in inclusive representation more broadly, there was an expectation from students and staff alike that a jazz history unit would engage in self-reflection and embrace difficult discussions around representation and inclusivity, while simultaneously illuminating a historical context within which to understand the music. There is an ever-growing body of literature that can contribute to this goal, but making it central to the pedagogical discourse may require a priority shift away from chronological canons. Johannes explains:

There are great women players throughout jazz history that you can find to add to listening lists. But the harder, the more challenging side of it has been finding equity in reading lists in terms of authorship. And I’m mindful of saying that’s been hard, because I think the criticism of that is always, “Well, you need to look harder, you need to do better…”. I think part of the answer to that is that a lot of the work that is written by women does not prioritise a chronological approach, or there’s not as many works by women that are like, here’s the history of bebop, or here is free jazz. And so when we are presenting a chronology, we are looking for work that can support that chronology. And that’s not the work that is out there. So instead we might ask “which people of colour and of diverse genders are writing about jazz. What have they written?” That’s our starting point. That creates the curriculum.

The proposal to deprioritise chronology, as Johannes suggests, forces a re-evaluation of the goals of jazz history teaching. But how else do we want students to engage in the study of jazz histories? There exists a responsibility to contextualise and challenge the dominant discourse encountered by students as reflexive and ever-evolving educators. The next section discusses how we experimented with this by questioning the content and recontextualising the purpose and presentation of jazz histories.

Recontextualising the content

Within this specific jazz history unit that is the focus of this research, there has been an increase in non-jazz students participating in the unit, influencing the discourse in the classroom. These non-jazz students come from both within and outside of the Bachelor of Music, bringing musical and disciplinary perspectives and expertise that enrich the discussion and broaden the perspectives of jazz-focussed students. Catering to these diverse groups presents both an opportunity and challenge. Reflecting on the purpose of study for these varied student groups, Robert observed:

For the jazz students, it’s important to be informed about the history of what they are doing, to inform their practice. For the more general musician, it gives a broader understanding of music…one of the aims is to make the students critically think, we challenge the students to think beyond the history of it, and then to have a critical understanding of the key themes.

This reflection articulates the practical musical use for jazz students studying the history, while also capturing the need to extend beyond musical idioms and engage critically with the wider context. Extending this further, Robert reflects:

It gives [our students] a greater understanding of the history of American jazz as a starting point. And then they move into their own history of Australia. So we obviously start with the American node, and then we bring in a global perspective, and then it’s localised… The importance of this jazz history unit is to investigate the broader social issues and cultural issues… our cultural understanding of who we are that is inclusive of settler colonisation and our indigenous culture history that informs our positionality to make us critically analyse our place in this world.

Michael reflects a similar positioning of the relevancy within a larger cultural, and non-musical, context, suggesting the study of jazz history should set out to critically re-imagine what it means in our local context:

The jazz canon can be very commonplace in a jazz performance degree we are not practising jazz in this hermetically sealed world of the university, we are engaging with a global culture, a local culture, and into First Nations culture as well. And having a very global understanding of that I think is quite important.

These reflections highlight the potential impact of jazz history studies to deepen students’ understanding of jazz performance practice, along both musical and cultural lines. An important outcome of this depth, and the resulting increased musical, cultural and social awareness, is a greater consciousness around practices of exclusion within jazz historiography. Returning to questions of chronology and canon, whether these best serve the goal of greater depth must be queried.

Acknowledging the problematic history of representation and inclusion in hegemonic jazz discourse, and the need to disrupt this narrative, provides a useful opening for the reimagining of jazz history pedagogy. Inversely, reproducing an orthodox regurgitation of jazz history runs the risk of perpetuating practices of exclusion and accepting cultural injustices such as gender discriminatory behaviours and sexual misconduct. Reflecting on their own experience as a learner, Johannes reflects:

I can recall conversations with lecturers [in my own experience as a student] that perpetuate sexist behaviour in terms of, you know, casually checking people out and things like that and objectifying people [outside of our peer group]… that kind of general laddie sort of discourse…what some people might call locker room [talk]… Because this is a performing arts institution, there’s dance courses, theatre courses… And so you have a lot of young women studying dance, sitting out having their lunch on the lawn, that kind of objectification where that was normalised to talk about how people look. So that’s the sort of cultural discourse that is floating in the air. By doing a jazz history unit within that culture, the awareness or the room to critique some of these things was not present.

Reflecting on the goals for contemporary jazz history pedagogy leads to further epistemological questioning; what is jazz history? Or rather, what should it be? A list of names and recordings? An understanding of a socio-cultural phenomena and the people within it? Is it the story of American racial and cultural politics, told through the lens of music? The complexities of any historical teaching results in a plurality of possible narrative angles, with the constraints of available resources and teacher expertise inevitably narrowing the focus. Reflecting on the impact of staff expertise, Robert notes:

[The] history of this unit is that it is taught by performers with expertise as artistic researchers, not with specifically expertise or training as musicologists. So we are developing our expertise even though, through our performance research and historical interest in the subject we have a strong understanding of the history of jazz chronologically and its social space. We’ve further developed our musicology and cultural study expertise as we have researched and taught the unit.

The lack of disciplinary knowledge in history may result in an over dependence on conventional jazz history literature and inherited concepts. This dependence can at times lead to the simplification of what is, in reality, a messy, rhizomatic unfurling of musical styles and cultures in a very compact timespan and gender diverse worlds.

I find that I am constantly saying the idea of a linear progression is problematic, right? Bebop did not grow linearly out of swing… Cool, and hard bop… this is not a straight line. It’s free and it’s messy and complicated. And I think part of the problem in teaching it with chronology is you suppress that messiness. And that’s what the jazz history books do as well, in some ways, because I guess the alternative is that you do not present a chronology. (Johannes).

To amplify this messiness, and the complex reality of musical and socio-cultural development, we must embrace a version of jazz history that emphasises the ability to critically engage with both the music and associated socio-cultural issues. There is a role for chronology in this version of jazz history, but perhaps it need not be the frame that everything else hangs from.

At the moment, there’s a chronology and we can hang the [socio-cultural] issues onto that, and we try to supplement that chronology with readings. And I would do the opposite, I would start with the conversation and the issues and then hang the music on to that, which would probably require some supplementary kind of timeline, like even some external thing that’s like, “look at this in your own time, this is where everything fits in a chronology, we are not going to be experiencing it in in this way.” And so you kind of complicate it in a good way (Johannes).

This perspective requires an understanding of the plurality of jazz history. There are many possible histories that might be presented and the version of jazz history that is prioritised speaks to the values of the institution. From a student perspective, this plurality needs to be explicitly communicated and it should be understood that in the context of a 12-week unit some things will necessarily be left out. The notion that key themes are the central pillars of any discussion of jazz history then allows the music to be understood through these contextual lenses, while simultaneously experiencing their musical qualities.

The use of “thematic pillars” to structure content supports evolving student interests and experiences, including the plurality of ideas and perspectives that result from an increase in non-music majors and double degree students. Reflecting on this, Robert noted that:

… some students just want to enrol in the unit and learn about jazz history and listen to some music, whilst other students major in other studies and want to bring that knowledge into the context of jazz history. For example a student studying law … students that are studying sociology and psychology… they are bringing their specific area of study and placing it in the discussion.

Deprioritising chronologies may allow space for the integration of diverse student perspectives in a way that improves contemporary connection and personal relevance, in addition to redressing historical biases. In doing so, the core purpose of a study of jazz history may be reframed in the minds of both students and teachers, away from names, dates and causal genre relationships, and into something more meaningful, alive and connected to contemporary experience.

Students who study other disciplines may bring additional conceptual tools to discussions, leading to more critical understandings of texts, and the expectation that tutorials will move beyond musical and musicological understanding. The strong practice-based background of much of the teaching team in this research leads to a pedagogical approach that may at times resist this, creating a gap between the space of pedagogical comfort for the teacher and the critical direction of the room. Michael notes that:

In performative degrees, there can be this idea that we’ll just kind of make it really simple, because the students are really just here for the doing aspect of the degree, rather than the intellectual part.

Robert further notes that in his experience:

[Performance students] would look at the historical side… they’ll want to study the key artists because it informs their practice … whereas I think [a non-jazz student] is not so focused on that, so as a result we have a much broader approach to investigating the artist that is inclusive of cultural and social elements.

The diversification of students in the room can lead to a tension between the desires of music students to improve their music-making and the needs of non-music students to expand their critical understanding of the discipline. This tension is ultimately a mirage though, as all students benefit from increased criticality, though there can be resistance. Michael noted some students’ lack of preparedness to question the orthodoxy.

One of the readings we did in the early weeks asked: how do you define jazz? Do you define it in a formulaic way? Are there different ways of defining different ontologies? And I got a question from one of the performance students just saying, why should we even bother doing that? And I think that kind of goes back to what I’m talking about, with my experience early on [as a student]. At that point in my life, I was also kind of not critical at all of what I was doing. I was just a participant that wasn’t questioning what was happening, I just wanted to make the music without understanding the music.

Michael highlights an intergenerational difference between the three teachers and students that relates to Halberstam’s queer temporal logic. Here exists the possibility of changing thenature of one’s relationship to the jazz canon as a matter of becoming a different kind of “jazzman,” characterised as a more understanding male in jazz with age.

Phase 3: responding to teacher-learner experience: making pedagogical moves

The critical thinking discussed above about the what and why of jazz history education is concomitant with a number of pedagogical moves the educators made to change how the teaching and learning occurred. In line with Halberstam’s concept of queer time, this section summarises the actions taken by the educators to make change, disrupt, challenge and reimagine the gendered narratives of jazz history and some of the outcomes in regards to the learners’ experience. The challenges include the embracing of discomfort. The lecturers in the researcher group are white, cis male teachers who acknowledge that a degree of discomfort can result when challenging one’s own privilege and power. The intention is not to compare it our discomfort to the experiences of more marginalised groups. Rather, discomfort is necessary for personal and professional growth. It is incumbent on us as critical and creative educators to “do the work” and this research represents an authentic attempt to engage in this responsibility to others.

Move 1: critical self-reflexivity

The first pedagogical move is the educators’ shift towards a critically self-reflexive disposition in relation to this music field. Being aware of and coming to deeper understandings of one’s positionality in relation to the wider musical field, but also the students, as part of that field, has been an important dimension of this teaching intervention. Deluca and Maddox (2016) support the argument that the questioning of one’s feelings of privilege and guilt encourages reflexive thinking and critical interrogation through the positioning of the self in the research process. Interestingly, for this research the critical self-reflexivity began in the classroom but continues to evolve through the writing of this article.

Initially, this criticality manifested as the male educators/authors heightened sensitivity toward their privileges as white cisgender men, which necessitated an acknowledgement of positionality and a relational way of teaching jazz history in the Australian context to students. For instance, Johannes questioned how he can represent diverse musical experiences, querying:

How do I talk about gender? How do I talk about race? I feel unsure how I should navigate some of these things that I know are problematic and difficult to talk about, but I do not feel equipped or feel like I have the lived experience or authority to comment on them.

Robert also noted some discomfort and uncertainty when discussing gendered experiences beyond his own lived experience, and the risk of saying the “wrong thing” by speaking for communities that he does not represent.

I feel that I’ve got to be very careful in what I say in relation to gender. I’ve made mistakes in the past whether it be gender pronouns, or not acknowledging my privileged position. So, I am retraining myself to be very cognisant of what I’m saying…I know I am in a position of power—in a sense a part of the dominant culture of jazz and so I need to be aware of my actions and the possibility of othering as a result of not having had the same experiences as minority groups.

Creative teaching requires challenging affects such as coping with discomfort and vulnerability (Skattebol, 2010). Not only evolving internal perspectives, but also adapting in response to student perspectives may produce a personal conflict and doubt, as in the case of Robert. However, this can lead to relearning around one’s positionality in relation to their students. Michael reflected on a teaching situation where he realised that he was not aware of the position he had taken and how hearing the voice of the students’ lived experiences informed his teaching approach.

One student managed to point out a kind of misogynistic undertone to the writing that I had not even touched upon. And so it is important to welcome and encourage those discussions in class. And for those students to have a voice and talk about these histories, with respect to their own experience was really quite revealing…

Michael highlights that when other voices are present, they may speak for themselves. Marginalised voices may also be heard through diverse forms of media, without tutor mediation. Through in-class discussion, in an environment where tutor facilitation and expertise is expected, it can be tempting to insert one’s own voice and perspective into the discussion, whether intentionally or through an attempt to understand the author of a specific text. Further reflection on the above quotes reveals an implicit assumption that educators should speak on behalf of other groups as the means to be representative of minority voices. Though facilitation of discussion is required for voices not physically present, through careful curation of media these voices may speak for themselves and these anxieties may be misplaced. In doing so we must reframe the notion of expertise, for both teacher and student, and exercise the power inherent in the role of educator to model how jazz history might be engaged with differently.

Move 2: chronological vs. thematic presentation

The second pedagogical move included changes that disrupted the hegemonic presentation of time and voice in response to the structure of the dominant texts in jazz history. As already noted, our experience as learners and scholars is that jazz history pedagogy frequently focuses on linear, chronological presentations—an approach mirrored in the dominant mainstream jazz history texts. The result of this is that diverse voices are repeatedly and systemically overlooked, with their absence entrenched in the jazz historiography. Recognising that literature by and about non-male identifying artists often sits outside of this narrow chronology, this pedagogical move aims to take diverse voices as the starting point, stepping outside of chronologies in favour of framing discussions around literature, resulting in a more thematic construction and presentation of material that is then historically contextualised.

This move also takes inspiration from Halberstam’s articulation of queer time. For Halberstam, critiquing the milestones that mark a heteronormative timeline helps establish the need for an alternative concept of time, one that includes and celebrates those that live outside of the hegemonic temporal mainstream. By applying queer time within jazz history pedagogy, this move suggests that rejecting the jazz-normative timeline and instead adopting a different conception of time that contextualises work within a chronology, but does not make that chronology the regulating concept, can similarly include and celebrate voices previously neglected by the dominant temporal conceptions of jazz history.

Move 3: diversifying materials

One goal of adopting non-chronological approaches is to make space for more diverse voices and materials. As already evidenced, the issue around the chronological approach to the writing of jazz history can limit the space for diverse literature. As a result, the changes made through this research, to expand beyond chronological presentations, has made room for diversity, embedding a varied and more inclusive approach to histories. Despite excellent literature, such as the seminal work of Rustin and Tucker (2008), simply layering more diverse literature onto an existing chronological framework can present challenges, as noted by Johannes:

Embedding [gender diversity] into our existing conversation about music, I think remains a challenge. It needs to be done in a way that does not feel like something insincere tacked onto the dominant jazz narrative […] and I think the students perceive [when it is an afterthought]. I think that we need to rethink how that discussion is had. So it’s not saying “Hello, we are going to talk about gender and jazz now,” but instead just normalising and rectifying some of the failings of the jazz history discourse as it currently stands.

This challenge was also reflected in the inclusion of supplementary resources intended to improve a chronological approach, which essentially preserved a masculinist paradigm, by feminising it rather than dismantling it and starting again. This approach risked the perception that gender resources were added for the optics of following school/faculty directives of gender equality, rather than as an important part of the pedagogical plan. Johannes notes in the following his unease with superficial additions such as these:

I actually think that’s where some students start to go, “this stinks, this smells fishy. You’re telling us that you want to talk about gender. But you are kind of slotting it in as this, you know, incidental afterthought. Like, let us talk about blues. And then let us talk about what the role of women was in the 20s. And that kind of fences that off in a way that kind of limits the focus…that’s sort of the way in which some of these discussions happen in the textbooks. And so that’s the way I presented it, as well. And it always felt a bit insincere. Like, it’s this extra thing, rather than actually going, “how can we reconstruct jazz history?,” while at the same time going, “I do not feel equipped to reconstruct jazz history,” either. So that sort of sense of unease about teaching it without actually being able to articulate the problem sometimes, and certainly not being able to find a solution.

This need for improvement in the context of how we delivered and integrated gender content came in the form of constructive feedback from the students who wanted to “… focus more on non-men” and “…explore gender and intersectionality further…” in the unit materials. As aforementioned in this paper, the use of Tony Whyton’s (2010) tropes as a foundation to challenge a male-centred and chronological approach to jazz history, led Michael to fill in the gaps of literature by and about female jazz musicians by generating discussion with the students through a rereading of literature by and about male performers. In other words, just because a text is by and about male performers does not mean it cannot be useful in disrupting power relations. It all depends on how it is read and what you do with that reading. For example, using a critical lens Michael explains:

We took Tony Whyton’s [narrative icons] framework, and we applied it to different writings about [a particular Australian male jazz musician]. I asked the students to reflect how the different typologies of Whyton’s were kind of popping up in the literature that we were reading, which created some really engaging conversations around gender and elements of masculinity, in how people wrote about it, and also in the sound [of the music], and the idea of an Australian jazz and Australian identity, and then also how that was tied to things like masculinity. So it wasn’t like the representation was in the authorship, it wasn’t diverse, but I was at least trying to bring a critical theoretical lens that they could use to get there themselves.

Johannes has had a similarly positive experience:

I have been successful in raising critical awareness of the issues that are there. So sometimes the discussions in class have been around the lines of “this is a problem. Let us talk about what we see here or what is noticeably absent in the way this article was written?” So taking problematic literature and making it the subject of critique, rather than trying to go “where’s the literature?” So I think those things have been successful in helping expand the critical awareness of our students of the kinds of issues that exist in jazz historiography.

By making problematic literature the subject of critique, the teaching staff have developed an environment where students are not passive recipients of information but active participants in deconstructing and understanding the content. The implication of this kind of teacher-led critique is that the dynamic of the learner-teacher relationship shifts, allowing for a more authentic dialogue whereby educators and their students are learning together by critically examining texts, focusing on what is present and, importantly, what is absent. Applying queer time within jazz history pedagogy and challenging the canonical timeline invites students to question the biases and gaps in existing narratives rather than merely seeking literature that aligns within a pre-established chronological framework.

The changes to the teaching of jazz history outlined here are the product of inviting student perspectives, listening to them and braiding them with a reflective teaching practice. It also demonstrates how the translation of diversified narratives in jazz pedagogy can inform the evolving nature of “new jazz studies” to be more inclusive of a sociological and ethicised approach, influencing the education of jazz teachers and learners.

Concluding summary

This paper explores the views and experiences of both students and teachers at an Australian tertiary university to understand the issues around the teaching and learning of jazz history. Polyethnographic and narrative methodologies are used to examine a pedagogical disruption to gender bias in jazz history literature, which is predominantly authored by men and features mostly male artists. It explores the issues and effects of this exclusivity, as identified by Whyton (2010) through his tropes of the male hero, genius, myths, and the masculine identity of jazz. In a time where society is grappling with past biases and inequities, educational practices need to reinvent new approaches to learning that reflect these changes. This paper outlines a pedagogical design and learning approach across a 5-year period, using a method of staff reflexivity and student input that disentangle the significance of Whyton’s tropes. The theoretical foundation of Halberstam’s theory of queer temporality was applied as a strategy to disrupt existing hegemonic chronological approaches to teaching jazz history.

Fundamentally, this study explores how the deprioritising of chronology’s function within the jazz canon, along with the embedding of non-biased theoretical frameworks, can help students to understand, question, reason and negotiate past and prevailing attitudes. This was achieved through a focus on teaching a theoretical knowledge of culture, race, gender and intersectional theory, providing students with informed understandings of the past through the interrogation of the canon and the chronological bias of jazz history literature. The differing experiences of the authors reflect the changes over time and why change was needed.

While recognising such change is ongoing, the results to date evidence the potential impact of this kind of pedagogical intervention and exploration. Moving forward, we face the challenge of not only continuing to teach and discuss in more gender-inclusive ways, but to expand this inclusivity into other spaces, recognising our post-colonial Australian context, the necessity to engage with First Nations’ ontologies and living histories, and the need for an understanding of jazz history that speaks to the “glocal” perspectives of Australian jazz.

Critiquing jazz history literature and pedagogy necessitates a consideration of what alternatives might exist. In response to this need, this study has turned its focus inwards, responding to the specific teacher-learner context of the authors, and making pedagogical change appropriate to this context. Our contribution to new knowledge lies in this reflexive process and pedagogical response: offering a model of change, an impetus to review and a pathway for further development. Future possibilities for this research include; a further review of the impact of the changes outlined in this research; a more comprehensive review of jazz history pedagogy across multiple institutions, and; the development of a pedagogical approach that might inform the teaching of jazz history in other institutions, particularly those in Australia. We hope this research inspires others to engage in critical reflection about their own and others’ teaching of jazz history to prompt vital shifts in both discourse and practice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC project ID35086). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Paul Williamson for establishing the Jazz History unit, along with Miranda Park and Talisha Goh for their teaching contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer GJ is currently organizing a Research Topic with the author RB.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This began with Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating’s (1991–1996) focus on the inclusion of First Nations perspectives and escalated with John Howard’s liberal government (1996–2007), whose priorities were the preservation of British culture (Fordham, 2015) that was reflected in the compulsory schooling curriculum.

2. ^A hybridity in the interaction of global music with local musical forms, which Nicholson calls the ‘glocalization effect’ (2014, p. 17).

3. ^Kellett et al. have developed a sociocultural logic of ‘ambivalence’ towards the various histories such as settler colonisation and identities that have permeated Australian jazz history. This ambivalence, Kellett et al. argue, is influenced by Australia’s status as a settler-colonial nation, and it reflects the ways in which many Australians have grappled with their nation’s colonial legacy.

4. ^For example, this movement includes gender inclusive initiatives of the Australasian Jazz and Improvisation Research Network (AJIRN), and decolonial and post-human provocations in improvisation like the “Companion "Thinking” of Rottle and Reardon-Smith’s (2023).

5. ^Tony Whyton, in his chapter Jazz icons: heroes, myths and the jazz tradition (2010), identifies clear tropes of the ‘masculine myth’, ‘jazz hero’, ‘tricksters and myths’, the ‘jazz frontier’ and ‘musical genius’ male hero, genius and myths that underscore the issues around the masculine identity of jazz within a chronological narrative.

6. ^ https://www.monash.edu/arts/music-performance/about/keychange-prs-foundation

7. ^We acknowledge that the premise of the KeyChange 50/50 gender split potentially reinforces a binary and the exclusion of gender minority groups that is counterproductive to gender equity.

8. ^SETU is the anonymous Student Evaluation of Teaching and Units feedback system for each unit at Monash University. Though student evaluation such as this is imperfect and not always reliable, it served as a useful initial ‘temperature check’ that informed further discussion.

9. ^Essays were the final assessment task in the jazz history unit. The topics were chosen by the students which were categorised as part of this study.

11. ^A term proposed by Arthur et al. (2017) so that several authors can engage in the autoethnographic method collaboratively.

12. ^Modelled on the work of Pasyk et al. (2022).

13. ^These questions/observations are stated on p. 9.

References

Arthur, N., Lund, D. E., Russell-Mayhew, S., Nutter, S., Williams, E., Vazquez, M. S., et al. (2017). Employing polyethnography to navigate researcher positionality on weight bias. Qual. Rep. 22:1395. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2558

Barolsky, V. (2023). Truth-telling about a settler-colonial legacy: decolonizing possibilities? Postcolonial Stud. 26, 540–556. doi: 10.1080/13688790.2022.2117872

Boeyink, N. (2022). “Jazzwomen in higher education: experiences, attitudes, and personality traits” in The Routledge companion to jazz and gender. eds. Herzig and Kahr (NY - REddan: Routledge), 348–358.

Boornazian, J. (2022). Mary Lou Williams and the role of gender in jazz: how can jazz culture respect women's voices and break down barriers for women in jazz while simultaneously acknowledging uncomfortable histories? Jazz Educ. Res. Pract. 3, 27–47. doi: 10.2979/jazzeducrese.3.1.03

Brown, L. B. (1991). The theory of jazz music" it don't mean a thing…". J. Aesthet. Art Critic. 49, 115–127. doi: 10.2307/431700

Buscatto, M. (2022). “Women's access to professional jazz: from limiting processes to levers for transgression” in The Routledge companion to jazz and gender. eds. Herzig and Kahr (NY - REddan: Routledge), 230–242.

Canham, N., Goh, T., Barrett, M. S., Hope, C., Devenish, L., Park, M., et al. (2022). Gender as performance, experience, identity and, variable: a systematic review of gender research in jazz and improvisation. Front. Educ. 7:987420. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.987420

De Bruin, L. R. (2016). Journeys in jazz education: learning, collaboration and dialogue in communities of musical practice. Int. J. Commun. Music 9, 307–325. doi: 10.1386/ijcm.9.3.307_1

DeLuca, J. R., and Maddox, C. B. (2016). Tales from the ethnographic field: navigating feelings of guilt and privilege in the research process. Field Methods 28, 284–299. doi: 10.1177/1525822X15611375

DeVeaux, S. (1991). “Constructing the jazz tradition: jazz historiography” in Black American literature forum, vol. 25 (St. Louis University), 525–560.

DeVeaux, S. K. (1997). The birth of bebop: A social and musical history. Los Angeles, USA: Univ of California Press.

DeVeaux, S. (2002). Struggling with jazz (Spring 2001-Spring 2002) © 2002 by the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. 71–73.

Early, G., and Monson, I. (2019). Why jazz still matters. Daedalus 148, 5–12. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_01738

Enstice, W., and Stockhouse, J. (2004). Jazzwomen: Conversations with twenty-one musicians, vol. 1. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press.

Feldstein, R. (2005). “I Don't Trust you anymore”: Nina Simone, culture, and black activism in the 1960s. J. Am. Hist. 91, 1349–1379. doi: 10.2307/3660176

Fordham, H. (2015). Curating a nation’s past: the role of the public intellectual in Australia’s history wars. M/C J. 18:1007. doi: 10.5204/mcj.1007

Gale, T., and Parker, S. (2017). Retaining students in Australian higher education: cultural capital, field distinction. Europ. Educ. Res. J. 16, 80–96. doi: 10.1177/1474904116678004

Gridley, M. (2007). “Misconceptions in linking free jazz with the civil rights movement” in College music symposium, vol. 47 (College Music Society), 139–155.

Halberstam, J. J., and Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York: University Press.

Hall, C., and Burke, R. (2022). “Negotiating hegemonic masculinity in Australian tertiary jazz education” in The Routledge companion to jazz and gender. (NY - Reddan, Herzog and Kahr: Routledge), 336–347.

Hegelund, A. (2005). Objectivity and subjectivity in the ethnographic method. Qual. Health Res. 15, 647–668. doi: 10.1177/1049732304273933

Ikart, E. M. (2019). Survey questionnaire survey pretesting method: An evaluation of survey questionnaire via expert reviews technique. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 4:1. doi: 10.20849/ajsss.v4i2.565

Johansen, G. G. (2023). Playing jazz is what she does”: the impact of peer identification and mastery experiences on female jazz pupils’ self-efficacy at Improbasen. Front. Educ. 7:1066341. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1066341

Lawson, S. R. (2022). “Inclusive jazz history pedagogy” in The Routledge Companion to Jazz and Gender, eds. Reddan, Herzig and Kahr. New York, 322–335.

Leder, J., (1985). Women in jazz: A discography of instrumentalists, 1913–1968. Westport, Conn. USA: Greenwood Press.

Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological perspectives. Black Music Res. J. 16, 91–122. doi: 10.2307/779379