- Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway

Introduction: Children in Europe and Norway grow up in an increasingly culturally diverse society. As of 2022, 20% of children in Norwegian Early Childhood Education (ECE) institutions have a minority background. It is essential for parents and ECE professionals to work together to ensure a good start for these children. The partnership between the ECE institutions and parents is a statutory right and duty, and parents should, on equal terms, participate and influence what happens in the ECE institutions. However, research has shown a wide variation in how ECE professionals create partnerships with minority and refugee parents, and many find working with this group of parents challenging. This article explores the experiences of the interactions and encounters between refugee parents and ECE professionals in a Norwegian ECE setting. The aim is to analyze the tensions in this partnership and provide insights into these encounters, negotiation processes and their experiences.

Methodology: The study is based on semi-structured interviews with twelve refugee parents, interviews with six pedagogical leaders, and one kindergarten manager. Additionally, fieldwork was conducted in one ECE institution to provide contextual depth.

Results: The data is analyzed thematically using an inductive research design. Through this analysis, three prominent themes emerged: 1) Barriers, 2) “Norwegianness”, and 3) Trust. The findings highlight the importance of trust in children’s care and the ECE institution’s safety. At the same time, refugee parents emphasize education as a key to a promising future in Norway and value the education aspect of ECE institutions as high. Communication and language barriers pose an extra burden or stress for both ECE professionals and refugee parents. “Norwegianness” as a cultural norm within ECE institutions is linked to the values, norms, and cultural capital valid within the ECE institution.

Discussion: The findings are discussed within the theoretical frameworks of cultural capital and power relations and critical pedagogy. The interactions and encounters between refugee parents and ECE professionals show tensions arising from differences in cultural norms and understandings. In summary, this article explores the challenges posed by cultural diversity in ECE institutions and argues for using cultural sensitivity to foster more flexibility in these encounters to enhance inclusion and belonging in ECE institutions.

Introduction

Children in Norway are being raised in a culturally diverse environment. According to Statistics of Norway, in 2022, 20% of children enrolled in Norwegian Early Childhood Education (ECE)1 have a minority background. In addition, 93.4% of all children in Norway attend ECE (Statistics Norway, 2022), which implies that children with minority backgrounds are exposed to the Norwegian language and culture when they attend ECE institutions. A solid and dialogic partnership between parents and ECE professionals and professionals2 is essential for a good start in ECE institutions, and it is both a statutory right parents have and the duty of the ECE institution to establish (Ministry of Education and Research, 2005, 2017). The partnership between parents and ECE institutions is even more crucial in a culturally diverse society (Tobin et al., 2013; Tobin, 2020). The research agrees on the importance of a strong partnership between migrant and refugee families and ECE institutions and professionals to foster belonging and processes of inclusion (Vandenbroeck, 2009; Janssen and Vandenbroeck, 2018; Solberg, 2018; Garvis et al., 2021; Sadownik and Višnjić Jevtić, 2023). According to the Framework Plan for Kindergarten in Norway and the Children’s Act (Ministry of Education and Research, 2005, 2017), parents have the statutory right to parental involvement and to impact what happens in the ECE.

Further, the ECE institution is legally obligated to establish a dialogic partnership with all parents according to the framework plan for kindergarten (Ministry of Education and Research, 2017). Scandinavian research on parental cooperation with minority parents in kindergarten has long focused on language and how shortages in Norwegian language competence make parental cooperation difficult (Becher, 2006; Gjervan et al., 2012; Glaser, 2018). Fewer scholars have investigated how parents with a refugee background experience the encounter with Norwegian ECE institutions. Of these studies, several points to language barriers, challenges linked to culture, and that nursery practice is still dominated by the major for care and parenting (see Solberg, 2018, 2019; Sønsthagen, 2018; Kalkman and Kibsgaard, 2019). Refugee and migrant parents may find parental involvement different from what they know from their own country, and expressing their perspectives may be difficult when facing professionals in the ECE setting (Van Laere et al., 2018). Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) found that migrant parents also highlight the social support the ECE institutions give them. According to Lund (2022c), refugee parents consider the ECE institution a social and learning arena for themselves and their children.

The ECE institution is an essential social arena for migrant and refugee families in a new country, learning cultural codes and a new language (Vandenbroeck et al., 2009). In attempting to recognize cultural diversity and respect families’ values, ECE professionals sometimes encounter conflicts between their notions of best practices and cultural responsiveness (Tobin et al., 2013). Several studies on minorities and migrants, including refugee families, have highlighted language barriers, challenges related to cultural differences, and ECE practices that are shaped by institutional norms of care and parenting (Palludan, 2007; Vandenbroeck, 2009; Vandenbroeck et al., 2010; Geens and Vandenbroeck, 2013; Kalkman and Kibsgaard, 2019; Lund, 2022c). In this article, I investigate how refugee parents and ECE professionals perceive their partnership, their interactions within the ECE institutions in Norway, their barriers and tensions, and how the ECE institutions and professionals can promote inclusion and exclusion through their institutional practices.

The study involved conducting 12 interviews with parents with refugee backgrounds who have lived in Norway for 1–3 years. They all have non-western backgrounds and limited or no experience with ECE institutions in Norway and their countries of origin. The study includes fieldwork and participatory observation, data from interactions between the refugee parents and the ECE professionals, the daily life in the ECE institution, and interviews with the ECE professionals in the ECE institution where their children are enrolled. Using Bourdieu’s (1977, 1996) and Bourdieu et al. (2006) theory of cultural capital and critical theory (Nicola, 2005; May and Sleeter, 2010; Rhedding-Jones, 2010; Rhedding-Jones and Otterstad, 2011; Kalonaityté, 2014; Røthing, 2019), the study analyses how refugee parents and ECE professionals experience the ECE partnership and how the ECE professionals practices and structural societal conditions shape and reproduce power relations between minorities and majorities. The research questions being raised and discussed are:

1. How do refugee parents and ECE professionals experience partnership with each other in ECE institutions in Norway, and how do elements of this partnership impact refugee families’ sense of belonging and inclusion?

This article examines how institutional practices in ECE institutions may impact refugee parents’ sense of belonging and inclusion in the ECE. Moreover, societal discrimination and prejudice can make the refugee parents feel estranged and excluded from the ECE institution. The barriers and challenges arising from the encounters between ECE institutions and the refugee parents will be discussed and explored. Addressing these challenges may promote understanding and create a more equitable ECE institution for all families. The following section outlines the interdisciplinary research on parental partnerships with minorities and refugee families.

The context of ECE

Early Childhood Education institutions in the Nordic countries share several common traits, for example, the child–centered and holistic approach, where care and parenthood are both private and public matters, essential to making children future citizens (Jensen, 2009), which may contrast with non-Western cultures where care and parenthood are mainly personal, a less holistic and child-centered view (Jávo, 2010). Therefore, studies from ECE contexts with this holistic approach are considered most relevant to the study. The backdrop for the institutional organization of childcare in Western societies reflects a social change emphasizing individual belonging and undermining collective relationships (Studsrød and Tuastad, 2017). Two distinguishing features are prominent: (1) the public presence and (2) a high degree of trust both between citizens and in social institutions (Hernes and Hippe, 2007; Wollebæk and Segaard, 2011). Hence, the values of the children’s best interests, equality between the sexes, and self-determination can vary across cultures (Aadnesen, 2015). Implicit and tacit expectations, different norms and behaviors, and pedagogical practices with little room for other models and understandings of parenthood, childhood, and views on children may affect the relationship between refugee parents and ECE professionals (e.g., Bundgaard and Gulløv, 2008; Sønsthagen, 2018; Lund, 2022b).

Studies on refugees in general (in Norway) can broadly be divided into three categories: studies of (1) refugees’ trauma, (2) cultural differences, and (3) parenthood. The studies of Bergset (2019), Erstad (2015), Friberg and Bjørnset (2019), Smette and Rosten (2019), and Nadim (2015) are examples of the two latter categories. They are considered most relevant for this study as they demonstrate how diverse cultural parenting models are experienced in different welfare and educational institutions, like the ECE institutions in Norway. This article includes research on minorities with refugee backgrounds, while ethnic, religious, and national minorities are excluded. Research on minority parents’ encounters with health services shows that many express concerns for their children and a cross-pressure between their and majority cultures (Aarset and Sandbæk, 2009; Aarset and Bredal, 2018). As a group, minority parents, including refugees, may experience conflicting aspirations on behalf of their children (Smette and Rosten, 2019). Studies of refugees in Europe show that refugees’ encounters with public institutions are essential for developing a sense of belonging and empowerment in the new society (Vandenbroeck et al., 2009; Van Laere and Vandenbroeck, 2017). Researchers also underscore that ECE professionals’ communication with minorities (including refugees), both children and parents, appears to be characterized by information rather than dialoge (De Gioia, 2003; Palludan, 2007; Kultti and Samuelsson, 2016). Barriers are also found to create challenges between refugee and minority parents and ECE professionals (De Gioia, 2003; Palludan, 2007; Kultti and Samuelsson, 2016; Solberg, 2018; Lund, 2022b). Studies from Norway and Iceland on ECE partnership have also shown that minority parents are often assigned a marginalized position compared to majority parents (Bergsland, 2018; Solberg, 2018; Sønsthagen, 2018; Einarsdottir and Jónsdóttir, 2019). Recent studies from ECE institutions show that the inclusion and processes of belonging of refugee children and parents in ECE settings involve tensions in negotiating language and cultural norms (Lund, 2022c; Kimathi, 2023). In this article, I discuss the challenges and tensions refugee parents experience in their interactions with ECE institutions and the experiences of ECE professionals in this parental partnership. The following sections outline the theoretical framework, methodology, results, and discussion.

Critical and power critical theory

Critical theory and power critical theories do not aim to criticize but to analyze processes that create and maintain power relations and privileges in different contexts, often associated with norm-critical perspectives and pedagogy in the education research field (Nicola, 2005; May and Sleeter, 2010; Rhedding-Jones, 2010; Rhedding-Jones and Otterstad, 2011; Kalonaityté, 2014; Røthing and Bjørnestad, 2015; Røthing, 2019). According to Kalonaityté (2014), p. 8, a norm-critical pedagogy aims to create an enduring awareness of societal power relations outside the educational settings of school and the ECE institution and argues that this needs an epistemological understanding and attitude. Such educational philosophy demands commitment and theoretical competence from practitioners (Kalonaityté, 2014, p. 9). Røthing (2019), p. 19 argues that ‘diversity competence’ requires relevant knowledge, power-critical theoretical perspectives, and recognition. Critical culturalism incorporates elements from multiculturalist and anti-racist pedagogy (Nicola, 2005; May and Sleeter, 2010; Rhedding-Jones and Otterstad, 2011). Within multiculturalism, children and adults are placed in cultural categories and assigned characteristics and rights based on their cultural identity. May and Sleeter (2010) criticize liberal multiculturalism in emphasizing cultural differences, arguing that the multiculturalism approach fails to see power differences between minorities and majorities. Within a critical multiculturalist process, children’s and parents’ culture is verified and acknowledged, but without over-focusing or simplifying the importance of cultural differences (May and Sleeter, 2010; Westrheim, 2014). According to May and Sleeter (2010) and Westrheim (2014), the critical multicultural approach does not categorize people and groups with common cultural characteristics or identities but acknowledges people without oversimplifying or over-focusing their cultural differences. Bourdieu et al. (2006) have a similar approach and argue that culture is dynamic and relational depending on people’s cultural capital and the power relations between groups and people within a society or specific context such as the ECE institution.

In this article, I explore how cultural, social, and symbolic factors affect adapting to a new country and culture, where educational institutions such as the ECE institutions play vital roles (Bourdieu, 1996; Bourdieu et al., 2006). Specifically, it examines the experiences and perceptions of refugee parents through the lens of Bourdieu’s (1996, 2006) critical theory of symbolic power, habitus, and social and cultural capital, and the ECE professional practices as institutionalized and their exercising of power. According to Bourdieu’s theoretical perspective, society comprises social structures, groups, classes, and symbolic systems like language and ideas. Further, these social spaces, or fields, have symbolic power and function as classification systems (Bourdieu and Prieur, 1996; Esmark, 2006). The ECE institution, for example, is a social space where people with different forms of capital (economic, cultural, social, and symbolic) interact. Specific capital forms may be valuable and necessary within a given social space and are not available for all. The refugee parents in the study come from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, including education, work experience, socioeconomic status, and nationality. However, their shared status as refugees in Norway is the focus of the analysis and the discussion of findings. The same relates to the ECE professionals; they have diverse backgrounds but have shared education as ECE teachers and positions as pedagogical leaders. The social positions of refugee parents and ECE professionals in social space (here: the ECE institution) as minority and majority with different habitus impact their perceptions, understandings, and ways of thinking and acting, as their access to cultural capital, and thus also the interaction between them (Bourdieu and Prieur, 1996; Bourdieu et al., 2006). In this context, habitus is “the sum of lived life” or the “totality of a person’s experiences.” Researchers have found that the majority’s cultural capital and doxa are normative for what happens in ECE and ECE’s encounters with minority and refugee parents (Solberg, 2018; Sønsthagen, 2018; Lund, 2021, 2022c). According to Bourdieu (1996), doxa operates at a subconscious level and is deeply ingrained in our habitus, which is a set of dispositions, attitudes, and behaviors that we acquire through our socialization and experiences, which implies that the refugee parents and the ECE professionals in the study have different habitues and base their knowledge ion different doxas. In the discussion, I argue that the refugee parents have limited access to what is considered valid capital in ECE, and how this access or lack of access to valid capital has an impact on the relationship and interaction between ECE professionals and refugee parents and what consequences this may have for the partnership, and ultimately on inclusion and belonging of the refugees.

Methodology and research design

The study presented in this article has an inductive and interpretive research design. It stems from qualitative, semi-structured interviews with 12 refugee parents, both women and men, observational material from “deliver and collect” situations in the ECE institution in the study, and interviews with six pedagogical leaders and one kindergarten manager. The informants were recruited through an Introduction Center for Refugees in a Western Norwegian rural municipality and the ECE institution where refugee parents’ children attended. All the parents have a non-western background (see Table 1), a refugee status, and a brief period of residence in Norway (1–3 years). They are participants in the compulsory qualification program and introduction program for refugees.3 Having their children in the ECE institutions is thus not an individual choice but a necessity as they do not have the option to stay home; they must attend the introductory program to have the right to economic introductory support. The data are analyzed thematic, sorted, and categorized in shared themes regarding the ECE institution and their partnership. Themes include upbringing, parenthood, barriers to partnership between parents and the ECE institution, and how to best integrate into society. The sample are shown in Table 1.

Ethical considerations

The researcher’s point of view will influence what the researcher sees or does not see; there will be blind spots. Ethical core discussions are therefore essential in all research work. Recruitment of parents with a minority background, with potential language and cultural barriers, distrust, and uncertainty, may present researchers with ethical issues and challenges. I have obtained ethical aspects by written informed consent (participation, use of audio recordings, and use of the material in research). The storage of notes and audio recordings safeguards the duty following confidentiality. All data is anonymized, and the audio files will be deleted after the results are published. Applications to the Norwegian Center for Research Data (SIKT) have been approved and prepared according to the research ethics guidelines.

However, when vulnerable groups participate in research, whether they feel the opportunity to decline participation is an ethical issue. Whether or not the voluntary sector is genuine depends on who asks for participation and the information. The refugee consultant at the Introduction Center was used as a gatekeeper and interpreter to ensure crucial information about involvement in the current research. The refugee consultant had a Syrian background and spoke Arabic, as did all the informants in the study. Because he spoke the same language and came from the same country as most of the refugee parents (Syria) in the study, he could provide clarifications and ensure that information about participation was adequately understood. The preparatory work related to informed consent and information about the research proved valuable and necessary to obtain contact with the research field, the informants, and the negotiations on access (Riese, 2019). During the analysis, I have strived for reflexivity and to present the informants’ voices in an ethically justifiable manner (Klykken, 2022, p. 13). In addition to the preparatory work for the interviews, I met the refugee parents in the “deliver and collect” situations in the ECE institution. I conducted all the parent interviews at the Introduction Center, assessing this as a more neutral, safe, and well-suited space in the ECE institution. I used an interpreter in half of the interviews; the other half was in my native language, Norwegian. The interpretation was conducted to reduce and minimize the influence and asymmetry in the relationship between me as a researcher, the interpreter, and the interviewee. The interpreter was hired through a professional interpretation service (Noricom).

As an outside researcher, a white Norwegian woman with a majority background may have influenced the refugee parents’ narratives. Also, my ethnic majority status and the interview situation may have similarities with the asylum process they previously experienced. Their prior experience from the asylum process may potentially have led the refugee parents to act more formally and correctly, withholding information and their own opinions, telling me what they assumed I wanted to know (Lidén, 2017; Kalkman and Kibsgaard, 2019). My research position and presence in ECEs in “deliver and collect” situations may also have contributed to the refugee parents holding back disagreements, fearing that what they said in the interviews might be passed on to the ECE professionals in fear of potential distrust. According to Bourdieu (1996) and Bourdieu et al. (2006), social structures are created by the fact that individuals as actors, through their actions and practical knowledge embedded in an embodied habitus, are constructed precisely by these objectives and hidden social structures.

Further, these social structures are reproduced by the actors interacting. In this perspective, social reality is constituted by hidden social structures, in which the actors’ consciousness and social experience are crucial to Bourdieu’s understanding of the world. Awareness of my preconceptions and influence in the social environment being studied has been essential in both the data collection process and the analysis, and reflexivity in the positioning as a researcher: […] relational pedagogics, which is aware of all the social differences and which is directed toward reducing them” (Bourdieu, 2003, s. 24).

According to Qureshi (2009), there are several reports on how professionals discriminate against minorities based on prejudice on ethnic grounds, lack of understanding, and distrust in their encounters with people from other countries and cultures. At the same time, my previous presence at the ECE institution may also have relaxed my parents because they had met before. According to Serrant-Green (2011), the experiences of minorities, such as the refugee parents in this study, may be in the blind spots of the majority. Raising awareness of how my positioning as a white ethnic majority has influenced my choices and interpretations is an essential methodological reflection. In the interview situation, the informants were allowed to speak as freely as possible. I avoided leading questions and emphasized dialoge in the conversation. As a researcher, I took a less active role to minimize the potential asymmetry in the interview situations. However, asymmetry in the relationship between the informants and me as a researcher became a communication challenge. In the interviews with the refugee parents, I chose to ask more follow-up questions than planned and had to take on a more active researcher role (Tjora, 2012).

Structural mechanisms may interact and position the informants in the ECE institution and social context. Therefore, research must evade legitimizing social models and the reproduction of existing (and symbolic) inequalities between social groups, as symbolic hegemony, between minorities and majorities in ECE institutions and society in general. However, researchers are also responsible for uncovering and identifying social differences resulting from cultural and symbolic capital (Skrobanek and Jobst, 2022). As Røthing (2019) argues, diversity competence requires relevant knowledge and power-critical perspectives to understand the power relations and structures of recognition. Reflexivity on these mechanisms and my positioning have been a focus throughout the research process (Lund, 2022a).

Analysis

The interview data was transcribed and read several times, color-coded, systematized, and analyzed using the NVivo program and marker pens in Word. The conversations and interview transcripts from encounters between parents and ECE professionals and their experiences as expressed in the interviews are analyzed, first with each category separately and then together. When data from refugee parents and ECE professionals was compared, shared themes became evident. In addition, I have chosen descriptions of situations and quotes from the interviews where ECE professionals and parents negotiate on values and understanding of the content and activities in ECE institution and their obligations as parents. The conversations could thus be interpreted as joint constructions between the ECE professional and the parents, however not necessarily on equal terms (Kvale, 2009). I used a professional interpreter for all the interviews with the refugee parents, but two. In the interviews without an interpreter, the presentation of the informants’ statements has occasionally changed grammatically to make the text more readable and understandable, but without altering the meaning with a focus on the importance of the informants’ stories and commonalities across the material. The fieldwork, participant observation in the ECE institution and interviews with ECE professionals were conducted in February 2019; contact and recruiting of refugee parents and interviews with the refugee parents were conducted later, in April 2019.

The analysis of both datasets was initially done separately. After that, the dataset from both parents and the ECE professionals was analyzed together, looking for common themes. I have used a reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) method, in line with a social constructivist epistemological (and ontological) perspective (Braun et al., 2022). The RTA method is a powerful tool that researchers can use to gain new insights by engaging in six crucial steps throughout the analysis process: (1) reading the transcripts, (2) coding, (3) analyzing based on produced codes, (4) critically reviewing the codes, (5) re-reading the transcripts, (6) writing. By following these steps, researchers can thoroughly analyze and interpret the data, leading to valuable insights and discoveries (Braun et al., 2022).

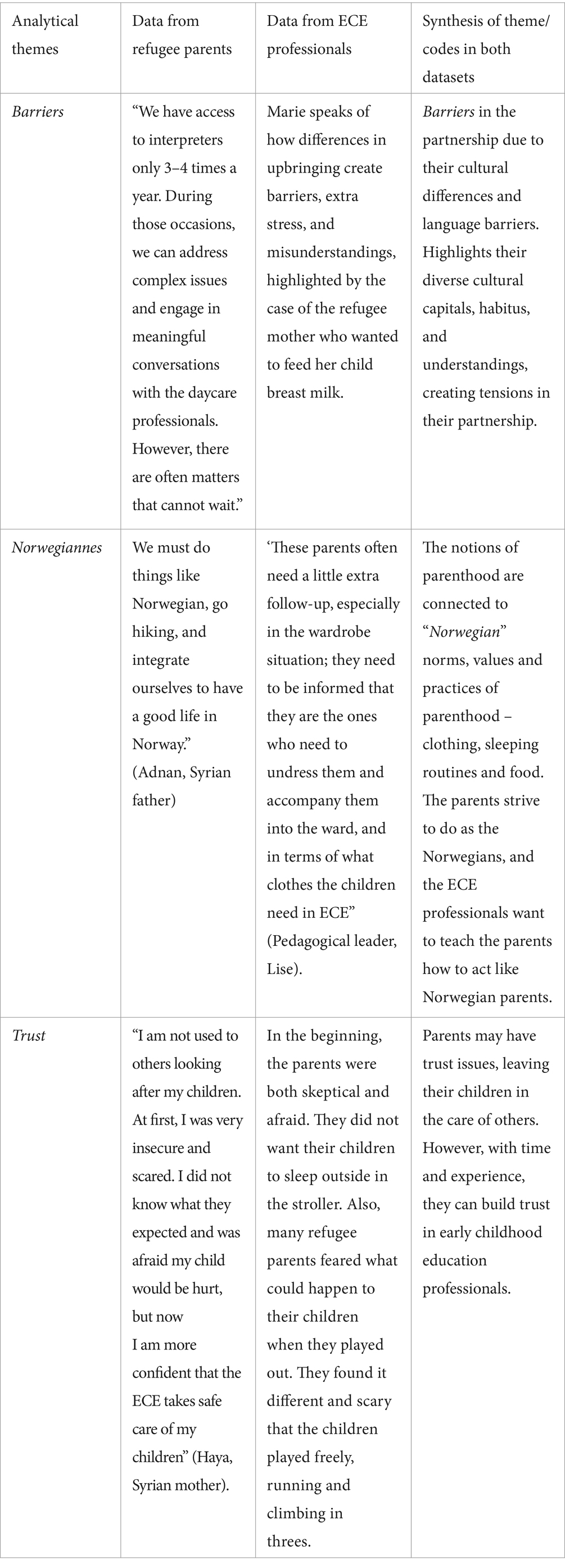

The themes found across the data from (both the parents and the ECE professionals) in steps two, three, four and five can be linked to values and perceptions of parenthood and childhood, experiences with the collaboration and partnership with ECE institution, and encounters of different cultural perspectives: (1) challenges such as language barriers, (2) parents’ experiences with ECE institution and the ECE professionals experiences in their encounter with the refugee parents, (3) shared focus on integration the Norwegian culture. The parents and the ECE professionals were asked the same questions: (1) What do you think is a decent quality of ECE? (2) What do you value as a good childhood, and (3) What do you consider as good parents? The data reveals individual variations connected to the refugee parents’ backgrounds, migration experiences, and the ECE professionals’ differences in age, knowledge, and work experience. Theoretically, they can be said to have different habitus(es) and epistemological understandings and access to the doxa applicable in ECE institutions (Power, 1999; Bourdieu et al., 2002). However, the focus of the analysis has been the shared themes among the parents and the ECE professionals. In coding and sorting all data, I grouped the main statements, topics, and meanings from parents and the ECE professionals and then developed the following analytical categories: (1) Barriers, (2) Norwegianness, and (3) Trust. However, the meanings of the categories differed. The themes shed light on the complexities of these encounters: The first theme, “barriers,” underscores language skills as a critical role in communication and engagement within ECE institutions and the challenges faced by individuals with limited language skills and emphasizes the need for inclusive strategies to bridge these linguistic divides. The second theme, “Norwegianness,” reals the significance of cultural norms and perceptions within the ECE institution context and the importance of recognizing and embracing cultural diversity while addressing normative expectations placed upon refugee parents and children. Finally, the third theme, “trust,” highlights the fundamental role of trust-building in fostering positive collaborations between refugee parents, ECE professionals, and the broader ECE institution. It emphasizes the need for open and transparent communication and the consequences of trust deficits in achieving positive outcomes for children. The table below shows an excerpt of the coding and sorting in the analytical process:

Findings

Due to their participation in the obligatory introductory program for refugees, sending their children to an institution is essential for refugee parents, not just a personal choice. Some refugee parents have yet to learn or experience the ECE as an institution and what to expect, and they may sometimes find the ECE institution to be unfamiliar. However, the study reveals that ECE professionals are experienced as friendly and respectful despite language barriers and cultural differences. Further, the analysis shows tensions between ECE professionals and refugee parents. The findings highlight the importance of trust in children’s care and the ECE institution’s safety. At the same time, refugee parents emphasize education as a key to a promising future in Norway and value the education aspect of ECE institutions as high. Communication and language barriers pose an extra burden or stress for both ECE professionals and refugee parents. In the following sections, I will elaborate on the empirical findings using the abovementioned analytical categories.

Barriers

Effective communication and interaction between refugee parents and ECE professionals in the ECE setting and language barriers may impede or create tensions in this relationship. Minorities such as refugee parents may face difficulties in Norway stemming from their unfamiliarity with the Norwegian language, cultural norms, and the rules and requirements of Norwegian ECE institutions. The analysis shows challenges encountered by parents with limited Norwegian vocabulary, the ECE professionals experiencing workplace pressures due to language barriers, and the refugee parents’ experiences of lacking knowledge of the Norwegian language and cultural codes. Mohamad, a Syrian father, shares his perspective as follows:

“We have access to interpreters, but it occurs only 3-4 times a year. During those occasions, we can address complex issues and engage in meaningful conversations with the ECE professionals. However, there are often matters that cannot wait”.

Despite facing challenges, most parents say they are satisfied with the ECE institution and describe a positive relationship with the professionals. Zahra, a mother from Syria, commented on how pleased she is with the care her child receives in the ECE:

“We have effective communication with the ECE professionals. The ECE professionals keep us updated on our children’s experiences and the activities at the ECE institution. We have productive meetings at the beginning and end of each year. If my child becomes ill or experiences any issues, they promptly contact us through telephone messages or calls. We are pleased with their services”.

The descriptions provided by refugee parents regarding their partnership with ECE institutions encompass both favorable experiences and challenges, challenges that contain linguistic barriers, a limited understanding of parental expectations, and the desire to discuss topics beyond practical concerns that hold personal significance to them and the perceptions about children and parenting. Despite the goal of promoting inclusion by assisting and informing refugee parents about Norwegian ECEs, the majority (Norwegian) definition of “good parenting” still holds sway in the ECE institution and the relationship between refugee parents and ECE professionals, as Marie, a pedagogical leader in Parken tells me in the interview:

“Before they arrived, the children’s parents needed to learn more about ECE institutions. We had to educate them on the fundamentals. I distinctly recall that when one of the children from a minority group began with us, they were accustomed to being breastfed exclusively. As a result, the child could not eat anything besides breast milk when they started. It was not milk formula but breast milk! Before starting in the ECE institution, the child had not yet learned to consume anything else. We assumed that everyone would understand our expectations after speaking with an interpreter. However, we should have taken more initiative to ensure they were fully informed. Also, it was challenging to communicate effectively with them as their Norwegian was limited. As a result, there were some minor issues and misunderstandings”.

Communicating with people who speak a different language can be difficult and lead to misunderstandings, such as the refugee parents and ECE professionals. To address this problem, learning new languages, using translation services, or utilizing simplified language when possible are essential actions that can prevent confusion and frustration for all parties involved. However, parents and ECE professionals need to articulate more support with the difficulties regarding access and frequency of translation services.

“Norwegianness”

“Norwegianness” as a cultural norm within ECE institutions is linked to the values, norms, and cultural capital valid within the ECE institution. It demonstrates how refugee parents and ECE professionals perceive, define, and navigate this norm. Additionally, it sheds light on how adherence to this norm affects the integration of diverse cultural backgrounds. How the welfare society meets minorities in ECEs (and schools) institutions can be decisive for identity development and belonging. Questions related to the future, integrating into the new culture, and learning “to become Norwegian” are essential in assessing what can provide a promising future. Adnan, a Syrian father, expresses the end for him and his family in Norway: “We have to do things like Norwegian, go hiking and stuff, integrate ourselves so that we can have a good life in Norway.” For many, arriving in a new and peaceful country after perhaps years on the run can be perceived as the dream itself. However, many find learning a new language, customs, norms, and culture challenging, as the quote from a Kurdish father, Aram, illustrates:

“I think we need time to get used to that life here in Norway, with that weather and society. The children must be in the ECE institution and the school. Moreover, there are so many rules we cannot follow, like what clothes they must wear to the ECE institution. Norwegians spend much time outdoors and love their woolen clothes”.

In their new life situation in Norway, refugee parents must balance different values between the new culture (Norwegian) and their own, which may be perceived as tensions and contradictions for many. The refugee parents are concerned that their children learn Norwegian culture and language that will ensure them a promising future in Norway, but also emphasize that the children must know their own culture, as Kandan, a Syrian father, emphasizes:

“[…] And we are committed to teaching our kids the rules in this country [Norway]. What is suitable for our culture? Furthermore, what is essential in this country is how it is with our religion and how they should respect other religions and other persons. We try to give the children a good life”.

When asked what they value as “good parents,” differences between their own and Norwegian parenthood are often highlighted as contrasts. Several of the refugee parents find that Norwegian parents spend a lot of time and money on their children, are permissive, and perceive Norwegian children as spoiled. Zilan, a Syrian mother, puts it this way: “We discuss parenting, but I do not always agree. I think we need to be strict with the children. I think the Norwegian parents say yes to their children too often.” A Syrian father, Bashar, also highlights this: “We have more discipline and are strict. Norwegian parents, I find somewhat soft and permissive. I think Norwegian children are spoiled.” Mustafa, another father, says, “We are perhaps more concerned with discipline while the Norwegian parents are more focused on “serving” the children. The Norwegian children also have fewer boundaries”.

Different parenting styles and values related to views on children and upbringing are actualized in the encounters with ECE institutions. Although the refugee parents come from different countries, a common denominator is their perception of Norwegian upbringing as more relaxed with less or no focus on discipline. At the same time, the refugee parents emphasize the importance of “Norwegianness” as crucial for integration and a promising future in Norway. In communicating with the refugee parents, the ECE professionals want to give them knowledge and “teach” them to understand what the ECE institution expects and ensure they become “good parents.” Their experiences of “good parenting” are here assessed based on the norm for “Norwegian parenthood” as addressed by Lise, a pedagogical leader in Parken:

“These parents often need a little extra follow-up, especially in the wardrobe situation; they need to be informed that they are the ones who need to undress them and accompany them into the department, and what clothes the children need in ECE institution. They do not know this with wool and “layer upon layer” and often come dressed in cotton clothes. And this with frameworks and routines at home. We have talked a little bit about the children being out late into the evening, which we [Norwegians] should have had a rule to put children to bed between seven and eight. They [the refugee children] come to ECE institutions and are very tired because they are awake late at night. We [Norwegians] are concerned that the children should go to bed no later than eight”.

The ECE professionals are most concerned with their differences and notions of the Norwegian norm of “good childhood” and “good parenting”. The following excerpt from a field observation may illustrate this:

“The pedagogical leader observes two siblings from ethnic minority backgrounds (ages 4 and 5) playing and tells me, “As you can see, they are very uneasy in their bodies. We believe the girls in this family watch TV and use many iPads at home. I live in the same neighborhood, and I rarely see them out on the playground, out for walks in the afternoons, or on weekends. I have tried to bring this up with parents, but they do not seem to think it is a problem” (fieldnote, from ECE institution, named Parken)”.

ECE professionals show the refugee children and parents respect but express concern about their lack of skills in the Norwegian language, everyday cultural (Norwegian) experiences, outdoor activities, and adherence to Norwegian norms for nutrition and sleep. Their approach focuses on parenting practices that differ from Norwegian parenting practices and the challenges this creates for them in their daily work. As the quote above shows, communication difficulties arise due to language barriers and different expectations and values related to upbringing and care. As demonstrated, language barriers and different expectations and values regarding upbringing and care can result in communication difficulties and potentially impact the partnership between ECE professionals and refugee parents.

Trust

The refugee parents underscore the need for trust in the ECE professionals when caring for their children. The answer to how their experiences of their (first) encounter in the (Norwegian) ECE, Isir, a Somalian mother, says this: “I like that my child thrives, but sometimes, I am scared. But that was before when I did not know how the ECE worked. I am not afraid anymore. My daughter is happy when I come to collect her in the afternoon.” The insecurity experienced by many of the refugee parents can be linked to their experiences with the ECE institution, as illustrated by Isir’s quote, and dissimilar perceptions related to childhood, parenthood, and the ECE institution’s expectations of the parents. Isir talks about how she was at first afraid but now feels safe, showing the socialization (or integration) process the refugee parents go through, where starting an ECE institution is described as challenging. However, they find it more accessible as time passes as they learn more about Norwegian culture and norms in the ECE institution and the Norwegian language.

Fear and distrust are recurring themes in the refugee parents’ stories of their encounters in the ECE institution. It may reflect cultural backgrounds from more closed and controlled societies and different perceptions and relationships to the state’s role in caring for children, parenthood, and education. Refugee parents’ migration histories of war and crisis, as they talk of in the interviews, may also create tensions and insecurities. Further, it is essential to consider how the ECE professionals encounter them. Are they satisfied with the ECE institutions understanding? Are they interested in their backgrounds and supportive? Or do they feel like they are always doing things the wrong way? Many of the refugee parents in the study seem to struggle to navigate new cultural codes and build trust with the ECE professionals. After escaping from war and conflicts, they must re-establish themselves and learn a new language and culture, which can be daunting. However, all the e refugee parents in the study expressed satisfaction with their contact with the ECE institution. Nevertheless, some also expressed skepticism about the safety of the ECE institution, as the quote from the interview with Marwa, a Syrian mother, illustrates:

“After hearing about these accidents in an ECE institution in the neighboring municipality, the abuse of underage children and this strangled child has made me uneasy. I want it to be surveillance to ensure children’s safety. The best, I think, is to change things regarding safety and security. As a mother, I feel it is better when there is surveillance. Have you mentioned this to the ECE professionals, I ask? Do you not feel safe or heard? Will you tell the ECE professionals that they should set up surveillance cameras? No, I will never do that. Because then it will be a matter of trust. I then express that I lack confidence in or trust them. It will never happen that I tell them about my wishes”.

The fear and uncertainty that Marwa describes above may also be linked to expectations of ECE as an institution, trust or distrust in public welfare institutions, perceptions of play and risk, and what children can and cannot manage. The insecurity reported by many of the refugee parents must also be seen considering an accident in an ECE institution reported in the media, where a routine failure by an ECE professional led to a child’s death.

As a result of several factors, such as differing views on children, parenthood, and different experiences in institutions such as ECE institutions and schools, ECE institutions’ safety can be questioned and lead to a weakening of trust. A high degree of confidence from society members that the institutions and professionals (in ECE institutions) considered in the best interest of the children can thus contrast ECE institutions and schools in their home country, as Haya, a Syrian mother, puts it:

“I am not used to others looking after my children. At first, I was very insecure and scared. I did not know what they expected and was afraid my child would be hurt, but now I am more confident that the ECE institution takes diligent care of my children”.

As expressed in the interviews, the relationships between refugee parents and ECE professionals appear to be two-sided: a beneficial relationship and tensions. They express confidence in the ECE professionals, that they are satisfied and experience respect from them, as both Haya and Isis articulate. At the same time, findings show that refugee parents express skepticism and concern, that they may withhold information in fear of loss of trust, as Marwa’s story exemplifies, or that they have been afraid and uncertain due to a lack of insight into expectations because they have no experience with ECE institution, as Isir story tells. In a field conversation in the ECE institution, ECE professionals discussed how they had experienced a rapidly increasing culturally diverse group of children and encounters with issues of trust and safety and different views on risk:

“In the beginning, the parents were both skeptical and somewhat afraid. They did not want their children to sleep outside in the stroller. Also, many refugee parents feared what could happen to their children when they played out. They found it different and scary that the children played freely, running and climbing in threes. We worked for some time to get them to trust us. Luckily, they got used to it and trust us more now”.

Both the ECE professionals and refugee parents highlight trust as an issue in their partnership. The refugee parents connect trust to their uncertainty and notions of what children can do and what they can manage independently, contrasting the ECE professionals’ notions of children’s play, independence, and risk outside.

Discussion

In this article, I have explored how refugee parents and ECE professionals experience the encounters in ECE institutions. Moreover, how does the nature of the ECE partnership contribute to inclusion and belonging? Findings show that refugee parents experience recognition and respect from ECE professionals. At the same time, the analysis reveals how the refugee parents experience tensions between their cultural backgrounds, belonging to the new culture and “do as the Norwegians,” and negotiations about parenthood in their encounters with (the Norwegian) ECE institution. Shared themes of both the refugee parents and ECE professionals are the perception of barriers, the importance of the notion of “Norwegianness,” and the establishment of trust in their partnership. In the following sections, I will discuss how the refugee parents’ and the ECE professionals’ experiences, as expressed through interviews and observations from the ECE institution, are influenced by institutionalized ECE practices, notions of parenthood and the potential consequences this may have for identity development, belonging and inclusion in the ECE institution.

“Cultivating parents”

Refugee parents’ values and diverse cultural models of upbringing may conflict with the institutionalized forms of care and upbringing prevalent in ECEs institutions (and society), potentially undermining trust in state institutions, a mutual issue, according to Ayon and Aisenberg (2010) and Jávo (2010). Care and upbringing in non-Western cultures are often viewed as solely private matters, unlike Western countries where public welfare institutions like ECE institution take care of children and take part in the children’s upbringing (Glaser, 2018), which may be an unfamiliar practice for many refugee parents. Cultural norms and values express society’s dominant and valid culture as a form of “collective” history or doxa (Bourdieu et al., 2006). The refugee parents’ reflections on the encounters with (Norwegian) ECE institutions and what they emphasize as necessary for a good life in Norway institution, must be interpreted considering the values and practices that give social validity within the ECE—assessing the perspectives and actions of others using their own culture (here: Norwegian) for what is the ‘right’ and shared value, the so-called ethnocentric view, may inhibit processes of inclusion and a sense of belonging, as previous research also have found (see, e.g., Palludan, 2007; Solberg, 2018; Lund, 2022b). The refugee parents in the study portray, through their narratives, the values and expectations of parenthood that seem to exist within the ECE institution, such as putting the children to bed at the “right” time, the “right” packed lunch, outdoor playing and hiking trips, the right clothes (Palludan, 2007; Solberg, 2018; Lund, 2022b). The (Norwegian) majority norm for care and parenthood, understood as Norwegian notions of parenthood, as expressed in the parents’ stories, appears as a hegemonic care discourse in ECE institutions, which is an execution of symbolic power (Bourdieu, 1996). As demonstrated, the ECE professionals’ practices and constructions of cultural diversity are mostly seen as challenges. However, a few of the pedagogical leaders in the study also find cultural diversity more positive, emphasizing that cultural diversity is a positive element in the ECE.

Nevertheless, the ECE professionals’ importance stress on challenges may be translated considering limited competence and knowledge in intercultural pedagogy and experience with this parent group. As Røthing (2019) has argued, to develop ‘diversity competence,’ you need relevant knowledge, power-critical theoretical perspectives, and an ability to recognize diversity as a resource. The ECE professionals in the sample have no or limited additional education, either in general or in multicultural pedagogy, and little experience with this parent group, which may explain why their constructions of cultural diversity are challenged and how they meet refugee parents. Lack of knowledge and competence may lead to over-focusing or simplifying the importance of cultural differences. Further, limited knowledge of how to work with parents from different cultures causes challenges that the ECE professionals strategies to handle; they stress “Norwegianness” as the “right way” (Nicola, 2005; May and Sleeter, 2010; Westrheim, 2014). The refugee parents, conversely, do not have the cultural capital valued in the ECE institution unless they “do as the Norwegians” parents.

As described by both the refugee parents and the ECE professional, communication and cooperation in their partnership have the purpose of informing and educating the refuge parents rather than dialogical, which may indicate a low degree of flexibility, understanding, and support, factors in the ECE professionals communication with minority parents (and children) seem to be characterized by primarily informative or education-oriented rather than dialogical (see, for example, De Gioia, 2003; Sønsthagen, 2018; Lund, 2021, 2022c). As shown, the ECE professionals in the study highlight the need to “teach” the refugee parents to act as Norwegian parents in line with Norwegian norms and culture. This approach contributes to under-communicating the importance of diverse cultural perceptions and emphasizing the dominant (majority) perspective of care and parenting as a discourse as “the right way.” As shown in the findings section, the ECE institutions’ norms of what they express as “proper upbringing and parenting” may also be interpreted as well-meant advice to the refugee parents. However, such approaches do not foster inclusion but become effective exclusion mechanisms, executing symbolic violence (Bourdieu and Prieur, 1996; Palludan, 2007; Solberg, 2018; Lund, 2021). The refugee parents’ statements, such as “we must do like Norwegians, go hiking and stuff, and integrate,” may be understood as a sign of this strategy to gain access to participation in the ECE institution. Nevertheless, the ECE professionals do not acknowledge their cultural capital (Bourdieu et al., 2006). Also, belonging and recognition by searching for “to become Norwegian” aligns with what, e.g., Lauritsen and Berg (2019) found that refugee and minority parents in their study did everything possible to blend in with the community and appear as similar as possible to the majority and strived to “integrate by do as the Norwegians.”

Although the refugee parents in this study emphasize Norwegian values related to care and upbringing, they also disagree with the ECE institutions’ norms and values. Nonetheless, they have explicitly confronted the ECE institution about their disagreements. Marwa’s criticism of the ECE institutors practices express to me in the interview, but not directly to the ECE professionals, because too much is at stake. As Marwa tells med in the interview, she wants to avoid a “matter of trust,” and also fear the consequences if critics the ECE professionals. As mentioned earlier, as refugees, the parents in this study are participants in the compulsory introductory program; they must participate in it to have the right to introductory economic benefits. Therefore, sending their children to ECE is not a personal choice but a necessity. The refugee parents’ dependence on the ECE institutions creates an asymmetrical relationship that may not be beneficial to building a genuine partnership, as noted by several scholars (see, e.g., Palludan, 2007; Dannesboe et al., 2012; Bergsland, 2018; Glaser, 2018; Lund, 2022b).

Beyond barriers – inclusion and belonging

The ECE institution is an arena where individuals from diverse cultural and social backgrounds meet and may serve as a socialization arena where both children and migrant parents get to know the new culture (Vandenbroeck et al., 2009; Van Laere and Vandenbroeck, 2017). However, the dominant culture in Norway seems to be prevalent in the ECE institution, with its resources and codes (Bourdieu et al., 2006; Lund, 2021). The ECE institutions can create a more inclusive environment by improving their sense of belonging and recognition. Examining how institutionalized ECE institutions practices and societal conditions affect refugee (minority) parents’ experiences is also essential. By understanding these factors, we can work toward developing a more equitable education system for all families and creating an egalitarian society recognizing different cultural identities, distributing economic and cultural resources, and redistributing cultural capital and resources (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990; Bourdieu and Prieur, 1996; Fraser, 2004, 2008). The ECE institutions may play a role in this respect, but by distributing “Norwegianness” as the cultural capital, it fails to include diverse cultural capitals. These challenges may lead to misunderstandings and disagreements between ECE professionals and the refugee parents, straining their relationship, cooperation, and partnership. Building trust is essential for positive collaboration in ECE institutions, which involves developing confidence among refugee parents, ECE professionals, and the ECE institution. Understanding the factors contributing to building trust and the negative impact of a lack of trust on children’s outcomes is therefore essential. The tensions between insecurity, trust, and respect can be understood considering the refugee parents’ processes of adapting to a new culture and creating a new life in a different country through which refugees find themselves. Additionally, refugee parents strongly desire to engage with ECE professionals on topics beyond the practical aspects of childcare. However, more access to interpreters and adequate capability in the Norwegian language is needed, as Mohammad articulates.

The findings show that an essential factor that contributes to inclusion and belonging is flexible professionals who are open to different cultural models regarding upbringing and parenthood to create a true partnership with mutual interest and understanding (Qureshi, 2009; Zachrisen, 2020; Skrobanek and Jobst, 2022; Lund, 2022b). In this way, partnership will foster integration and inclusion simultaneously. It is essential to address the challenges faced by minority parents with refugee backgrounds in cooperating with ECE professionals, enhancing the feeling of belonging and recognition for refugee parents. ECE professionals can create a more inclusive and supportive environment and how institutionalized ECE institutions’ practices and societal conditions affect the experiences of refugee and minority parents. By understanding these factors, ECE professionals and ECE institutions can work toward creating a more equitable and welcoming education system for families with a refugee background in Norway. Some examples of institutionalized ECE institutions practices that seem to affect the refugee parents’ access to inclusion demonstrated in this study are language barriers, limited access to information, cultural differences in communication and the understanding of parent- and childhood, and access to the valid cultural capitals of the ECE institutions in Norway. In addition, societal conditions such as discrimination and prejudice can create isolation and exclusion for these parents (Bourdieu and Prieur, 1996; Bourdieu et al., 2006; Lund, 2022c). Therefore, the ECE institutions must address challenges and promote inclusion for a supportive and equitable education system. Researchers have found that communication between ECE institutions and minority groups, including refugees and their children, tends to be one-sided and lacks dialoge and that language barriers make it challenging for parents to cooperate with ECE professionals (De Gioia, 2003; Palludan, 2007; Kultti and Samuelsson, 2016).

While Norwegian ECE professionals have satisfactory general knowledge of childhood and pedagogy, their specific knowledge regarding the needs of minority language children is more limited. Studies on ECE parental cooperation and partnership in Scandinavia have shown that ECE professionals may struggle to establish good relationships with minority parents, particularly newly arrived refugee families (Bouakaz and Persson, 2007; Kramvig, 2007; Bouakaz, 2009; Dannesboe et al., 2012; Lunneblad, 2013, 2017).

Toward more flexible ECE practices?

The refugee parents in the study presented in this article can indirectly exert influence and power by questioning established ECE institutions’ practices and prevailing norms within the ECE institution. The refugee parents’ questioning may compel the ECE professionals to reflect and reevaluate their professional practices, attitudes, and values. The refugee parents questioning may potentially lead to positive changes in their approach toward a more culturally sensitive pedagogical practice and cultural responsiveness (Lund, 2022b,c), contribute to professional development and serve as a source of inspiration for developing professional learning among the ECE professionals (Zachrisen, 2020; Sadownik and Ndijuye, 2023).

The refugee parents’ values, norms, and perceptions about parenthood may differ from those they encounter in Norway. The refugee parents may also need to change their perspectives and adapt to a new culture (Jávo, 2010). In addition to learning a new language, the refugee parents in my study need to become familiar with ECE as a social institution with its logic and expectations. The ECE institution is also valued as an arena where negotiations about parenthood occur and an arena for inclusion and an understanding of the cultural codes and the Norwegian language (Lund, 2022c). Norwegian ECE institutions can be perceived as unfamiliar with their logic and partly hidden rules. As several of the refugee parents in the study say, there are both practical (correct clothes, packed lunches, etc.) and implicit expectations about parenthood that may be difficult to know and understand, such as that wool warms better than cotton, what right bedtimes, clothes, and packed lunches.

Many of the refugee parents in the study share a common desire for their children to attend a safe and supportive ECE institution where they can thrive and learn Norwegian. ECE institutions are also crucial for promoting integration and socialization for parents and children. However, Norwegian studies have highlighted ECE professionals’ challenges in recognizing and responding to cultural diversity, feeling unsure and lacking the skills to effectively engage with this group of parents (e.g., Sønsthagen, 2018; Bergset, 2020; Lund, 2021; Rønning Tvinnereim and Bergset, 2023). Additionally, there is a tendency to prioritize the (Norwegian) majority norms of parenting and upbringing rather than engaging in critical discussions about handling intercultural encounters, issues of power dynamics and trust in line with several scholars in the field (Palludan, 2007; Lunneblad, 2017; Solberg, 2018; Sønsthagen, 2018; Mikander et al., 2018; Lund, 2021).

When integrating minorities in modern societies, a liquid approach to integration may be more effective for promoting inclusion and acceptance (Skrobanek and Jobst, 2019, 2022). Instead of focusing on integration as static and rigid processes, liquid integration acknowledges the complex and ever-changing interactions between society’s personal, social, and structural factors today (Bauman, 2013) and in migration (Engbersen, 2012; Skrobanek and Jobst, 2019, 2022; Jobst and Skrobanek, 2020).

Conclusion and implications

In this article, I have investigated how refugee parents and ECE professionals experience encounters and their partnership and examine the factors that may influence the refugee parents’ sense of belonging within ECE institution. Findings have revealed refugee parents’ experiences of challenges and tensions in the encounter with ECE institutions and the ECE professionals’ understanding of their task as “cultivating” or socializing refugee parents into the existing ECE institution’s logic and notions of parenthood. The findings of this research may lead to an understanding of ECE institutions as an arena for inclusion and a more inclusive and equitable education system, increased support for minority parents with refugee backgrounds, and better outcomes for their children. The findings of this study are based on a rural area, which has less cultural diversity than the larger cities in Norway. Therefore, these findings may not be directly applicable to those contexts. However, the ECE institution in the sample represents a typical Norwegian ECE institution with 10–15% cultural diversity, consistent with most ECEs outside of major cities in Norway. The Norwegian ECE institution system can benefit from creating a more welcoming and supportive environment for all families by addressing language and cultural barriers and promoting understanding and inclusion through more flexible ECE institution practices (e.g., Lunneblad, 2017; Lund, 2021; Rønning Tvinnereim and Bergset, 2023). Ultimately, this could lead to more social integration and improved opportunities for minority families living in Norway. I argue that recognizing and including refugee families in ECE institutions and addressing cultural diversity will benefit professional development and reflection (Sadownik and Ndijuye, 2023) toward a more culturally sensitive approach and flexible professional practices to enhance inclusivity. It involves acknowledging how one’s sociocultural experiences and cultural backgrounds impact professional practice and valuing the differences and similarities between children and parents. A more culturally sensitive perspective and flexible practices may foster a desire to learn more about all children’s and parents’ experiences and backgrounds, ultimately promoting a more inclusive environment (Zachrisen, 2020; Lund, 2021).

In a rapidly globalizing world where cultural diversity is a defining characteristic of our societies, the findings of this research are particularly relevant to developing cultural sensitivity. By embracing and valuing diversity, ECE institutions can create enriched learning environments that benefit not only refugee children but all children participating in ECE institutions and may contribute to a broader dialog on the importance of culturally inclusive education. There is a need for more empirical studies to explore the extent and variety of cooperation between ECE institutions and refugee parents to shed light on an essential issue to create more inclusivity in ECE institutions and to provide deeper insights into how refugees experience encountering the Norwegian ECE for the first time, and how ECE professionals experience these encounters. The perspectives of refugee parents are valuable in developing institutional practices in the ECE institutions that promote inclusion and a sense of belonging. These practices should not only be limited to those with refugee backgrounds but also to all migrants new to a culture and country and parents from diverse backgrounds and cultures since the norms of ECE institutions are highly institutional and may be unfamiliar to all parents initially.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HL: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this paper, the term Early Childhood Education and the acronym ECE will refer to ECE settings, centers and institutions. The term ECE institution is throughout the text. In Norway, ECE is intended for social and pedagogical purposes and is the responsibility of municipalities. Both private and public providers offer ECEC services, which cater to children between the ages of one and five. While ECEC is financially subsidized, parents are still required to pay a fee.

2. ^The description - ECE professionals are used throughout the text as ECE staff with a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education. Staff is used in more general terms, including all staff in ECE.

3. ^The Introduction Program Act covers newly arrived foreigners between 18 and 55 who need basic qualifications. The Act covers those who have been granted asylum, arrived as a resettlement refugee, or have been granted a residencepermit because of a need for protection. The introduction program aims to provide basic skills in Norwegian, fundamental insight into Norwegian society, and preparation for participation in working life. It is full-time and contains Norwegian language training, social studies, and measures that lead to further training or work activity. The program usually lasts 2 years and is based on a cooperation agreement between the municipality and social services The Act of Introductory Program for Refugees, (Ministry of Labour and Inclusion, 2004).

References

Aadnesen, B. (2015). Forståelser av barnets beste i et flerkulturelt barnevern i Norge. Current Information system in norway.

Aarset, M. F., and Bredal, A. (2018). Omsorgsovertakelser og etniske minoriteter. En gjennomgang av saker i fylkesnemnda.

Aarset, M. F., and Sandbæk, M. L. (2009). Foreldreskap og ungdoms livsvalg i en migrasjonskontekst. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/177529.

Bergset, G. (2019). Kva styrer og kva styrker samspelet mellom barnehagepersonalet og foreldra? Ein studie om kommunikasjon mellom personale i barnehagen og fleirkulturelle foreldre med migrasjonsbakgrunn. Nordic J. Comp. Int. Educ. 3, 49–64. doi: 10.7577/njcie.3334

Bergset, K. (2020). Parenting in exile: narratives of evolving parenting practices in transnational contact zones. Theory Psychol. 30, 528–547. doi: 10.1177/0959354320920940

Bergsland, M. D. (2018). Barnehagens møte med minoritetsforeldre: En kritisk studie av anerkjennelsens og miskjennelsens tilblivelser og virkninger. Doctoral thesis.

Bouakaz, L., and Persson, S. (2007). What hinders and motivates parents’ engagement in school? Int. J. Parents Educ. 1:1.

Bourdieu, P. (1995). Den kritiske ettertanke: grunnlag for samfunnsanalyse. 2nd Edn. Oslo: Samlaget.

Bourdieu, P. (2003). Participant objectivation. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 9, 281–294. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.00150

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J. C., Bundgård, P. F., and Esmark, K. (2006). Reproduktionen: bidrag til en teori om undervisningssystemet. Copenhagen, Denmark: Hans Reitzel.

Bourdieu, P., Prieur, A., and Jakobsen, K. (2002). Distinksjonen: en sosiologisk kritikk av dømmekraften. Oslo, Norway: De Norske Bokklubbene.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bundgaard, H., and Gulløv, E. (2008). Forskel og fællesskab: Minoritetsbørn i daginstitution. Copenhagen, Denmark: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Dannesboe, K. I., Kryger, N., Palludan, C., and Ravn, B. (2012). Hvem sagde samarbejde?: Et hverdagsstudie af skole-hjem-relationer. Bristol, CT: ISD LLC.

De Gioia, K. (2003). Beyond cultural diversity: exploring micro and macro culture in the early childhood setting. Available at: http://handle.uws.edu.au:8081/1959.7/795.

Department of Education and Research (2006). The children’s act. Department of Education and Research.

Einarsdottir, J., and Jónsdóttir, A. H. (2019). Parent-preschool partnership: many levels of power. Early Years 39, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2017.1358700

Engbersen, G. (2012). “Migration transitions in an era of liquid migration” in European Immigrations. Trends, Structures and Policy Implications. ed. M. Okólski (Nieuwe Prinsengracht: Amsterdam University Press), 91–107.

Erstad, I. (2015). Here, now and into the future: Child rearing among Norwegian-Pakistani mothers in a diverse borough in Oslo, Norway. [Doktorgradsavhandling, Universitetet i Oslo]. Olslo.

Esmark, K. (2006). “Bourdieus uddannelsessociologi” in Pierre Bourdieu: en introduktion. ed. K. Esmark (Copenhagen, Denmark: Hans Reitzels Forlag), 71–114.

Fraser, N. (2004). Recognition, redistribution and representation in capitalist global society: an interview with Nancy Fraser. Acta Sociol. 47, 374–382. doi: 10.1177/0001699304048671

Fraser, N. (2008). Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. New Delhi: Critical Quest.

Friberg, J. H., and Bjørnset, M. (2019). Migrasjon, foreldreskap og sosial kontroll. Fafo Rapport 1:53.

Garvis, S., Phillipson, S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., and Sadownik, A. R. (2021). Parental engagement and early childhood education around the world. Abingdon: Routledge.

Geens, N., and Vandenbroeck, M. (2013). Early childhood education and care as a space for social support in urban contexts of diversity. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 21, 407–419. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2013.814361

Glaser, V. (2018). Foreldresamarbeid: barnehagen i et mangfoldig samfunn. 2nd Edn. Oslo: Universitetsforl.

Gjervan, M, Andersen, C. E., and Bleka, M. (2012). Se mangfold!: perspektiver på flerkulturelt arbeid i barnehagen. (2. utg. ed.). Cappelen Damm akademisk.

Hernes, G., and Hippe, J. (2007). Kollektivistis individualisme. Hamskifte. Den norske modellen i endring. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

Janssen, J., and Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). (De)constructing parental involvement in early childhood curricular frameworks. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 26, 813–832. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533703

Jávo, C. (2010). Kulturens betydning for oppdragelse og atferdsproblemer. Transkulturell forståelse, veiledning og behandling. 11. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Jensen, B. (2009). A Nordic approach to early childhood education (ECE) and socially endangered children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J 17, 7–21. doi: 10.1080/13502930802688980

Jobst, S., and Skrobanek, J. (2020). “Cultural hegemony and intercultural educational research–some reflections” in Bildungsherausforderungen in der globalen Migrationsgesellschaft: Kritische Beiträge zur erziehungswissenschaftlichen Migrationsforschung. eds. W. Baros, S. Jobst, R. Gugg, and T. H. Theuer (Lausanne, Switzerland: Peter Lang Publishing Group), 17–23.

Kalkman, K., and Kibsgaard, S. (2019). Vente, håpe, leve: familier på flukt møter norsk hverdagsliv. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Kalonaityté, V. (2014). Normkritisk pedagogik: för den högre utbildningen. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

Kimathi, E. (2023). Tensions of difference in integrating refugee children in Norwegian ECEC centers. Nordisk Barnehageforskning 20, 43–62. doi: 10.23865/nbf.v20.409

Klykken, F. H. (2022). Implementing continuous consent in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 22, 795–810. doi: 10.1177/14687941211014366

Kramvig, B. (2007). Fedres involvering i skolen: Delrapport fra forskningprosjektet cultural encounters in school. A study of parental involvement in lower secondary school, Tromsø, Norway: Norut. Norut Report, No. 5.

Kultti, A., and Samuelsson, I. P. (2016). Diversity in initial encounters between children, parents and educators in early childhood education. Voices on participation: Strengthening activity-oriented Interactions and growth in the early years and transitions, pp. 140–152.

Kvale, S. (2009). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 2nd Edn. Copenhagen, Denmark: Gyldendal Akademisk.

Lastikka, A. L., and Lipponen, L. (2016). Immigrant Parents’ perspectives on early childhood education and care practices in the Finnish multicultural context. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 18, 75–94. doi: 10.18251/ijme.v18i3.1221

Lauritsen, K., and Berg, B. (2019). “Familien i eksil–om å finne fotfeste i et nytt land” in Vente, håpe, leve. Familier på flukt møter norsk hverdagsliv. eds. I. K. Kalkmanog and S. Kibsgaard (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget), 23–37.

Lund, H. H. (2021). “De er jo alle barn–Mangfoldskonstruksjoner i barnehagen” in Hvordan forstå fordommer? Om kontekstens betydning–i barnehage, skole og samfunn. eds. R. Faye, E. M. Lindhardt, B. E. Ravneberg, and V. Solbue (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget), 148–176.

Lund, H. H. (2022a). ““Through the researcher’s gaze”. Field roles, positioning and epistemological reflexivity doing qualitative research in a kindergarten setting” in Inquiry as a bridge in teaching and teacher education. NAFOL 2022. ed. K. R. Smith (Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget), 125–142.

Lund, H. H. (2022b). Ulikhet, likhet og mangfold: pedagogisk ledelse og foreldreskap i kulturelt mangfoldige barnehager PhD-avhandling. Bergen, Norway: Høgskulen på Vestlandet.

Lund, H. H. (2022c). «Vi må gjøre som nordmenn, gå på tur og sånn, integrere oss»: Flyktningforeldres erfaringer med barnehagen. Nordisk Barnehageforskning 19:385. doi: 10.23865/nbf.v19.385

Lunneblad, J. (2013). Tid till att bli svensk: En studie av mottagandet av nyanlända barn och familjer i den svenska förskolan. Nordisk Barnehageforskning 6:339. doi: 10.7577/nbf.339

Lunneblad, J. (2017). Integration of refugee children and their families in the Swedish preschool: strategies, objectives and standards. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 25, 359–369. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308162

May, S., and Sleeter, C. E. (2010). Critical multiculturalism: Theory and praxis. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Framework Plan for the content and tasks of kindergartens. Osla: Ministry of Education and Research.

Nadim, M. (2015). Kulturell reproduksjon eller endring? - Småbarnsmødre med innvandringsbakgrunn og arbeid. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 32, 15–24. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1504-3053-2015-01-03

Nicola, Y. (2005). Critical issues in early childhood education. United Kingdom: Open University Press.

Palludan, C. (2007). Two tones: the Core of inequality in kindergarten? Int. J. Early Child. 39, 75–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03165949

Power, E. M. (1999). An introduction to Pierre Bourdieu’s key theoretical concepts. J. Study Food Soc. 3, 48–52. doi: 10.2752/152897999786690753

Qureshi, N. A. (2009). Kultursensitivitet i profesjonell yrkesutøvelse. Over profesjonelle barrierer, et minoritetsperspektiv i psykososialt arbeid med barn og unge. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

Rhedding-Jones, J. (2010). Critical multicultural practices in early childhood education. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rhedding-Jones, J., and Otterstad, A. M. (2011). Barnehagepedagogiske diskurser. Oslo: Universitetsforl.

Riese, J. (2019). What is ‘access’ in the context of qualitative research? Qual. Res. 19, 669–684. doi: 10.1177/1468794118787713

Rønning Tvinnereim, K., and Bergset, G. (2023). “Det er veldig forskjellig fra hjemlandet mitt”: Migrantforeldres erfaringer med kommunikasjon og samhandling med barnehagepersonalet. Nordic J. Comp. Int. Educ. 7:5457. doi: 10.7577/njcie.5457

Røthing, Å. (2019). «Ubehagets pedagogikk»–en inngang til kritisk refleksjon og inkluderende undervisning? Scand. J. Intercult. Theory Pract. 6, 40–57. doi: 10.7577/fleks.3309