- 1Department of Social Work, Amrita School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, India

- 2Department of Liberal Arts, Alliance University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

- 3Department of English and Humanities, Amrita School of Arts, Humanities and Commerce, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, India

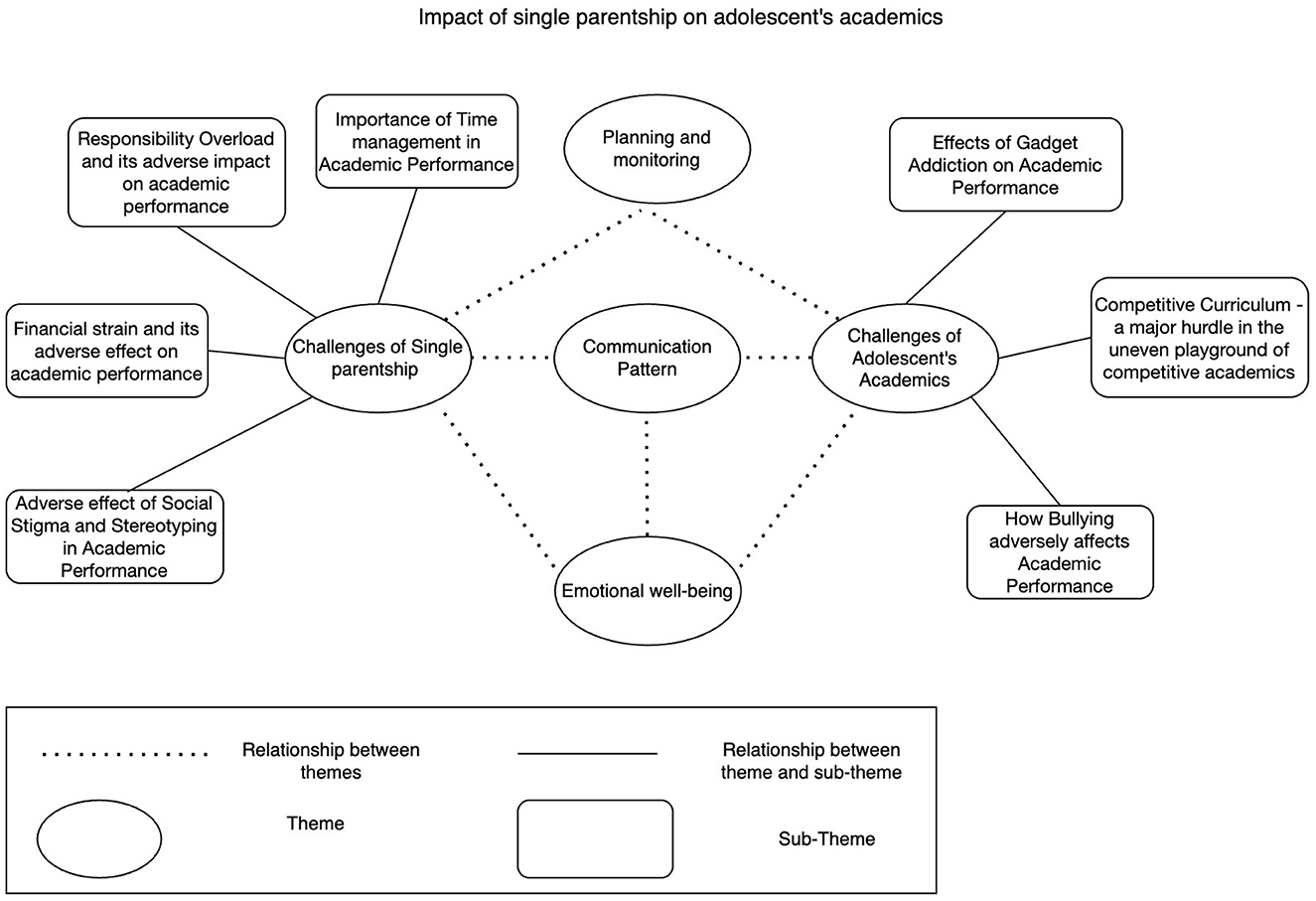

Adolescents in single-parent families frequently encounter academic challenges amplified by financial, temporal, and emotional constraints. Guided by Family Systems Theory this study explores the lived experiences of single-parents in India and identifies implications for educational professionalism-that is, the capacity of teachers, counselors, and school leaders to respond proactively to diverse family structures. In this study, semi-structured interviews with 12 single-parents of eleven to eighteen year old adolescents were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis. As a result, five inter-linked themes emerged: (1) challenges of adolescents' academics (Effects of Gadget Addiction on Academic Performance, How Bullying adversely affects Academic Performance, Competitive Curriculum—a major hurdle in the uneven playground of competitive academics); (2) challenges of single-parentship (Financial strain and its adverse effect on academic performance, Responsibility Overload and its adverse impact on academic performance, Adverse effect of Social Stigma and Stereotyping in Academic Performance, Importance of Time management in Academic Performance); (3) communication patterns; (4) emotional wellbeing; and (5) planning and monitoring. These findings underscore the need for flexible, stigma-free school practices, such as after-hours conferences, scholarship pipelines, and anti-bias training to ensure single-parent families are true partners in schooling and implies that embedding these recommendations within professional standards can help operationalize inclusive, context-sensitive education.

Introduction

Single-parent families constitute an increasingly visible demographic worldwide, accounting for roughly 10–12 % of all households in high-income countries and rising steadily in middle-income regions (Berghammer et al., 2024). India mirrors this trajectory: census micro-data indicate that the proportion of households headed by a lone mother or father grew from 4.5% in 2001 to about 7.8% in 2019, with urban centers recording the sharpest gains (Sinha and Ram, 2019). Legislative shifts such as streamlined divorce proceedings and improved widow-pension schemes have made single-parenthood more visible, yet social services and school policies have lagged behind these demographic realities (Herbst and Kaplan, 2016).

A multi-country meta-analysis confirms that students reared in single-parent homes score on an average one-quarter of a standard deviation lower on mathematics and reading assessments than peers in continuously married-parent families, net of socioeconomic status (Pong et al., 2003). Similar trends surface in India's National Achievement Survey data, where children from single-mother households perform significantly below the state mean in grades 8 and 10 (Garcia and Tillmann, 2025). Explanations converge on three mechanisms: (a) resource dilution-reduced income and learning materials (Cooper and Stewart, 2021); (b) time scarcity-one caregiver managing employment and child supervision (Skomorovsky et al., 2019); and (c) cumulative stress-exposure to conflict, stigma, or grief that erodes cognitive bandwidth (Chen and Wu, 2022). Each pathway separately predicts lower homework completion, diminished subject mastery, and weaken school attachment (Brown and Johnson, 2021). Studies have shown that adolescents from single-parent families with low socioeconomic status tend to perform worse academically than their peers from dual-parent families (Garg et al., 2007). Self-esteem of the adolescent from single parent families might get influenced by their peer relationships (Mohan, 2020). Limited access to basic educational resources, such as books, a quiet space to study, or internet connectivity, further exacerbates the academic challenges faced by these adolescents.

Educational professionalism: concept and policy imperative

Educational professionalism refers to the ethical, reflective, and responsive practice of educators committed to equity and continuous learning (Seleem et al., 2025). India's National Education Policy 2020 exhorts schools to become “vibrant, caring, and inclusive communities,” but operational guidelines remain generic, often presuming a two-parent involvement model (Venkata et al., 2025). International frameworks likewise stress collaborative professionalism-teachers partnering with social workers, psychologists, and families to address multifaceted barriers (Hargreaves, 2019). Yet empirical reviews reveal that teacher preparation programs seldom include modules on engaging single-parent households, leading to inadvertent deficit stereotyping and lower expectations (Fox, 2020).

Objectives of the study

1. To explore the lived experiences of single-parents as they engage with the Indian school system, striving to get good education for their adolescents.

2. To identify the specific educational challenges faced by single-parent families in supporting their adolescent children's academic journey.

Purpose of the study

The standard model of parental involvement often assumes a family has two parents and stable financial and emotional support. This model might not be suitable for this growing group of families. Therefore, educational professionalism needs to be redefined to include the ability to be empathetic, flexible, and adaptable to the needs of diverse families. This study offers the data needed to help guide this redefinition.

The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore the real-life experiences of single-parents as they interact with the Indian school system. The main goal is to turn their challenges into practical recommendations that can inform and improve educational professionalism.

Theoretical background

This study is grounded in Family Systems Theory, a theoretical framework that can be used to explain the complex interactions between single-parent families and the educational system. It provides a lens for understanding both the internal dynamics of the family and the external support structures needed from educational professionals.

Family systems theory

Family Systems Theory, developed by Murray Bowen, views the family as an interconnected emotional unit. It suggests that the actions and emotional state of one member directly affect all other members (Watson, 2012). This framework is particularly useful for understanding the challenges faced by adolescents in single-parent homes. The absence of one parent disrupts the family's balance, leading to shifts in roles, responsibilities, and relationships that can significantly impact an adolescent's development and academic life (Amato, 2005).

A core concept of this theory is the “differentiation of self,” which is the ability to remain an individual while staying emotionally connected to the family. In single-parent families, adolescents may struggle with this because of a heightened emotional connection with the single-parent, especially if the parent depends on the adolescent for support (Hooper and Doehler, 2011). This can increase the adolescent's stress and reduce their capacity to focus on school. Furthermore, the theory explains how the functioning of the single-parent-who often faces immense economic and emotional pressure-can influence their parenting style and, in turn, their child's academic success (Watson, 2012). Family boundaries can also become blurred, with adolescents taking on adult roles that interfere with their school responsibilities (van Dijk et al., 2025). By using Family Systems Theory, this study analyses how these internal family dynamics create specific needs that educational professionals must understand to provide effective support.

Family Systems Theory reflects Bronfenbrenner's ecological perspective, recognizing that schools and families form linked microsystems whose interactions significantly influence a child's development; thus, educational policy evaluation must include measures of family–school relational quality in addition to academic outcomes (Long et al., 2021). This is especially important when designing policies that support families experiencing disruption, such as single-parent households. Educational policy evaluation should include measures of family–school relational quality in addition to academic outcomes (Martinez-Yarza et al., 2024), emphasizes that strong family–school relationships improve both student outcomes and the long-term success of education systems, highlighting the need for policy evaluations to include indicators like relational trust and family wellbeing. The family systems theory highlights the need to restore balance within the family system; for example, school-based family interventions can help clarify boundaries and reduce emotional overdependence, which may in turn address issues like excessive gadget use through shared parent-adolescent monitoring strategies (Watson, 2012).

Need for study

Adolescents thrive on consistent, quality interaction with their parents, irrespective of the family structure and the quality of this interaction directly reflects on their academic performance. They require guidance in navigating homework requirements, understanding complex concepts, and developing effective study habits. They crave emotional support, encouragement and reassurance as they encounter academic setbacks and celebrate achievements. The rise in single-parent households in India has brought increased attention to the unique educational challenges faced by adolescents in these families (Sahib and Aldoori, 2025). Despite this demographic shift, there remains a significant gap in research specifically addressing the academic, emotional, and social struggles of adolescents from single-parent families in the Indian context (Naushad, 2022). Studies have found that adolescents in single-parent families often experience lower academic achievement and higher dropout rates compared to those from two-parent families, underscoring the need for focused investigation (Park and Lee, 2020).

This research tries to throw light to the complex terrain navigated by single-parents as they work with their adolescents through their academic challenges. By examining the specific challenges the single-parents face, and investigating the types of support needed by their children, and the potential hindrances in providing that support, we hope to uncover the unique challenges of adolescents of single-parents in their academic performance and help academic professionals to formulate relevant interventions to support them. Many existing studies on single-parenting and adolescent education are based on Western populations, and their findings may not be directly applicable to the Indian socio-cultural environment, where family dynamics and societal expectations differ considerably (Sinha and Ram, 2019). Recent Indian research highlights that adolescents in single-parent families face additional barriers such as financial constraints, reduced parental involvement, and limited access to educational resources, which can negatively impact their academic performance (Sinha and Ram, 2019). Furthermore, the stigma attached to single-parenthood in India often leads to social isolation for both parents and adolescents, compounding educational challenges (Dharani and Balamurugan, 2024). There is a pressing need for more empirical studies in India to identify effective interventions and support systems tailored to the needs of single-parent families (Mishra et al., 2021).

Methods

Informed consent: the participants were informed about the purpose of the study and assured of confidentiality. Full disclosure of the research process, including the reflexive nature of the analysis, was provided to participants.

Voluntary participation: participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without prejudice. This right to withdraw had been communicated to the participants. Participants were also encouraged to skip any questions that they did not feel like answering, with any number of questions.

Confidentiality: anonymity and confidentiality were assured throughout the research process.

Study design

This research employed an inductive qualitative study with a naturalistic approach, utilizing semi-structured interviews to explore the experiences of single-parents supporting their adolescent children's academics. This method focuses on understanding phenomena in their natural settings, allowing patterns and theories to emerge from the data itself (Cutler et al., 2021). It emphasizes the researcher's role in interpreting these experiences while acknowledging the inherent subjectivity of both researcher and participants, facilitating a nuanced understanding of individual narratives and their contextual complexities.

Settings

The researchers conducted the study from Dec 2023 to Jan 2024. They sent out a brief introduction explaining the study, the importance and the prerequisites of the research with their contact numbers for potential participants to reach out to them. This was published in social media forums such as Facebook and WhatsApp groups. The respondents were reached out to validate the participation criterion and to clarify any apprehensions that they might have had. Whoever reached out thus, were requested to refer others in their connections who also meet the research criterion to expand the sample size. Snowballing like this was important to get enough respondents since the sample universe is a reserved population.

Out of the initial pool of 92 respondents, 36 were excluded from the study: 32 because their children were below the minimum eligible age of 10 years, and 4 because their children exceeded the maximum eligible age of 22 years, with the youngest in this latter group being 23 years old. An additional 28 respondents did not meet the single-parent criterion and were therefore excluded. Sixteen participants initially consented to participate but subsequently discontinued communication and did not proceed to the data collection stage. Following confirmation of eligibility, interview appointments were scheduled. Data were collected through audio-recorded interviews conducted via telephone, using a laptop for recording.

Participants

While the snowball sampling technique has limits, such as the possibility of bias and results that may not apply to everyone, it worked well for finding people willing to share their personal experiences on a sensitive topic. The sample included 12 single-parents (11 mothers, 1 father) living in urban and semi-urban areas of India. Eight of the participants were from urban areas and four of them were from semi-urban areas. Each of the single-parents had at least one adolescent who was between the ages of 11 and 18.

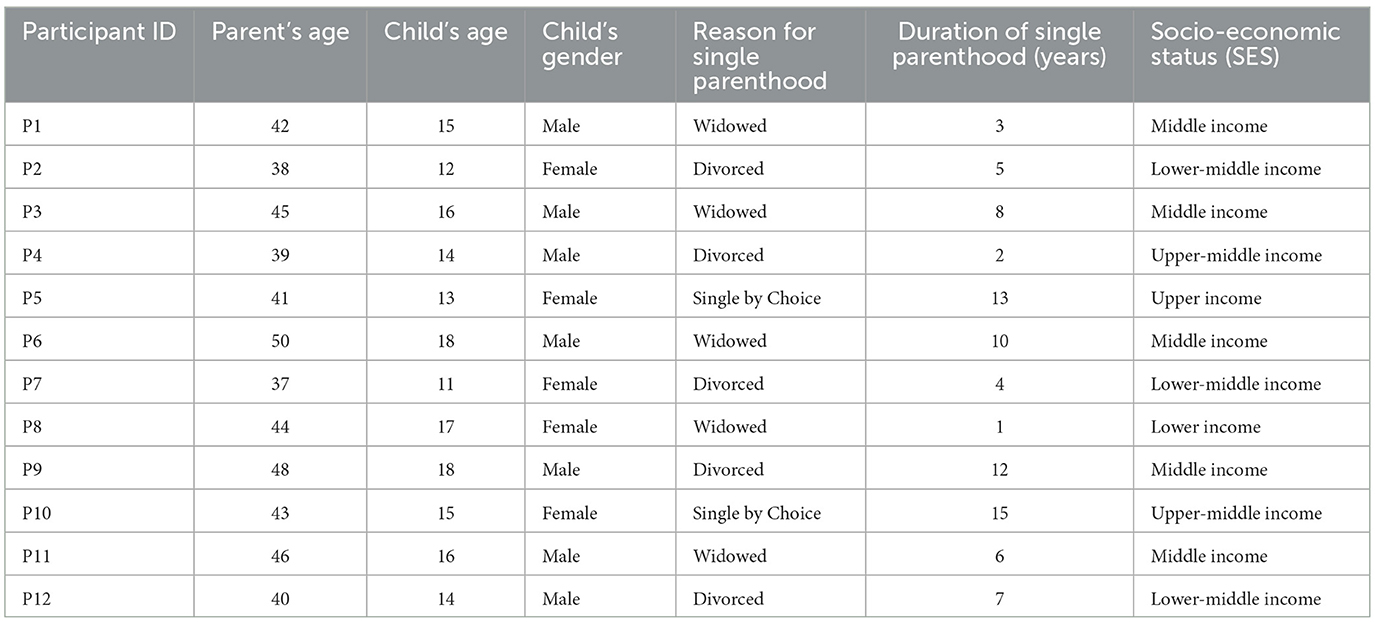

To provide the context needed to understand the findings and to address criticisms of past research that lacked such detailed demographic information was collected from each participant. This information is shown in Table 1. Including these details is not just for description; it is essential to the professional focus of this paper. It gives educators and counselors the background knowledge they need to move beyond a single view of “the single-parent family” and toward a practice that is responsive to individual differences. For example, this context is vital because the support an educator needs to provide for a recently widowed parent dealing with grief (like P1) will be very different from the support needed for a family that has been a stable single-parent household for years after a divorce (like P2). A one-size-fits-all professional approach is not effective, and the Table 1 below provides the context for a more tailored understanding.

Data collection

Reflexive Interviewing: participants were interviewed individually using a flexible interview questionnaire. The questionnaire served as a starting point, fostering open-ended dialogues that allow participants to delve deeper into their own experiences and perspectives. The researcher adapted the interview based on emerging themes and participant cues, promoting a collaborative and responsive dialogue.

The guide covered topics such as:

° Sociodemographic information

° Family structure

° Challenges faced in providing academic support

° Types of academic support adolescents need

° Barriers to providing effective support

° Coping mechanisms and strategies used

° Perceived impact of single-parenthood on adolescent academics

° Experiences with existing support systems (if any)

Duration: interviews lasted approximately 60–90 min and were audio-recorded with participant consent.

Field notes: the researcher took detailed field notes throughout the research process, capturing observations, reflections, and evolving understandings of the data. These notes helped the analysis and contributed to the researcher's own reflexivity.

Data analysis

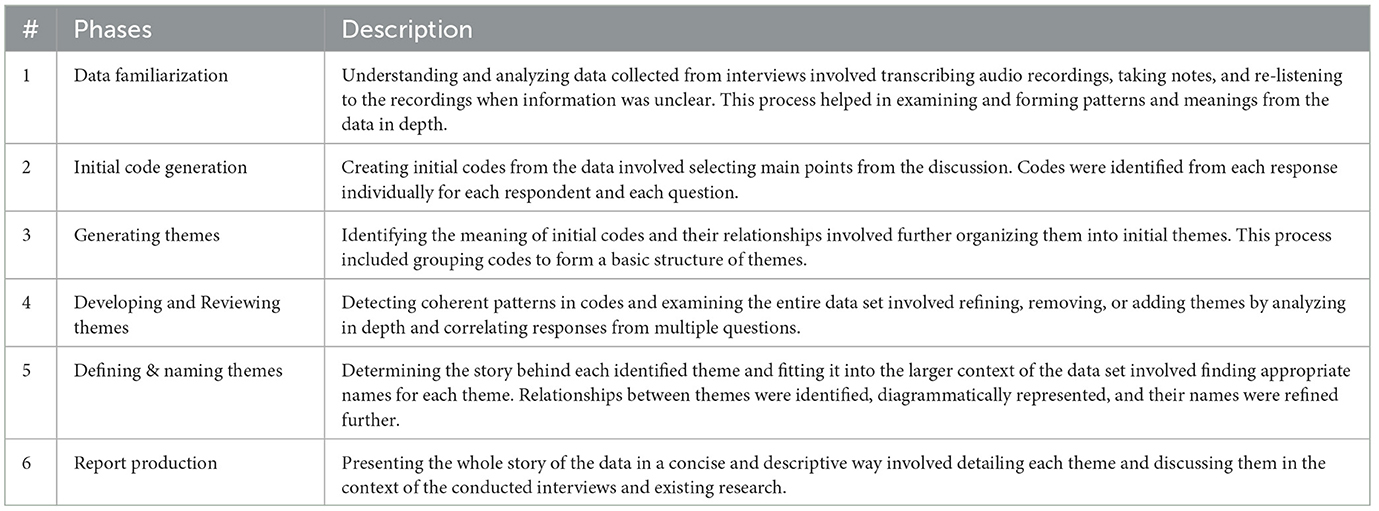

Reflexive Thematic Analysis: interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using Braun and Clarke's (2019) framework for reflexive thematic analysis. Table 2 depicts the phase of the framework.

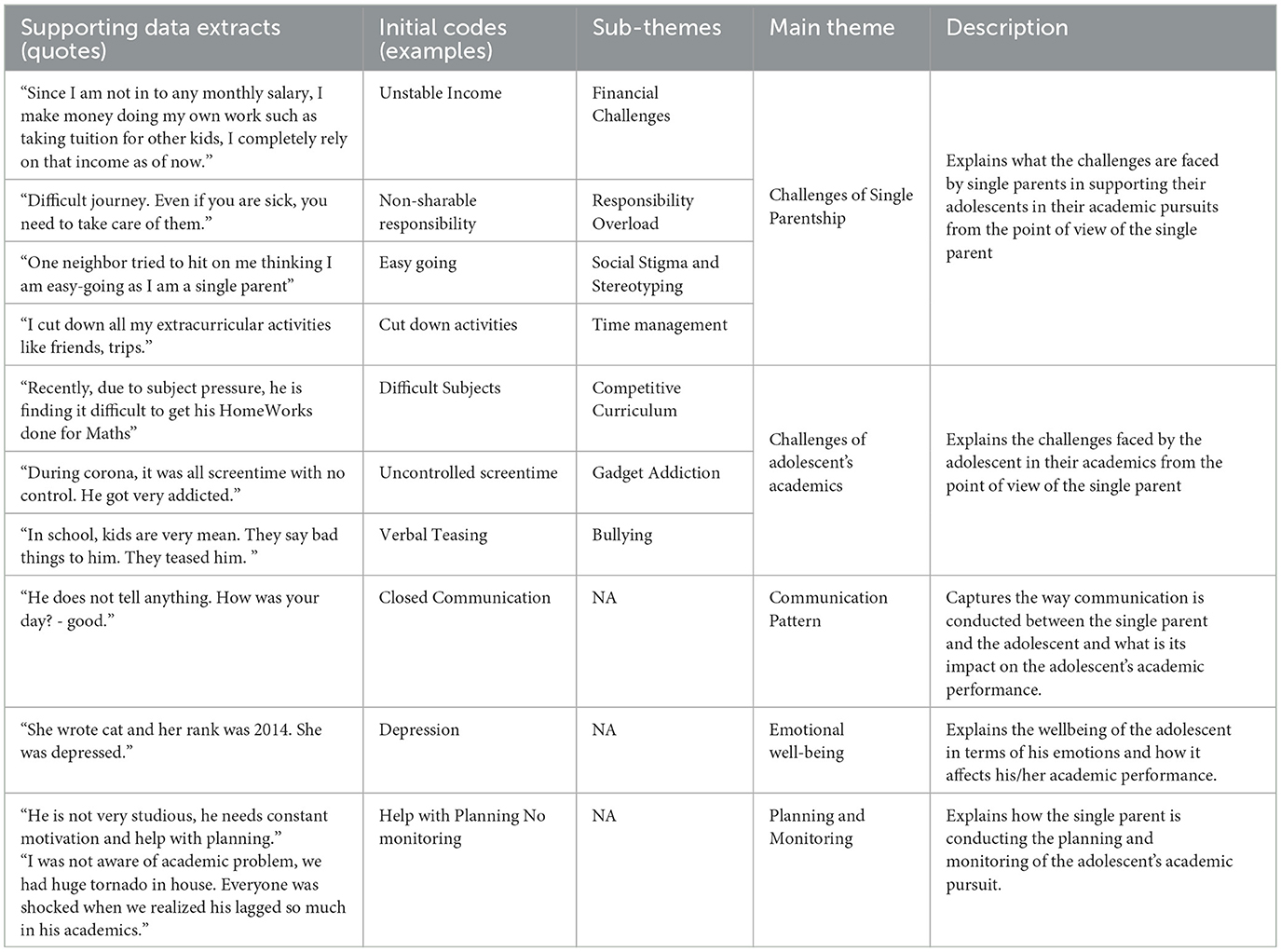

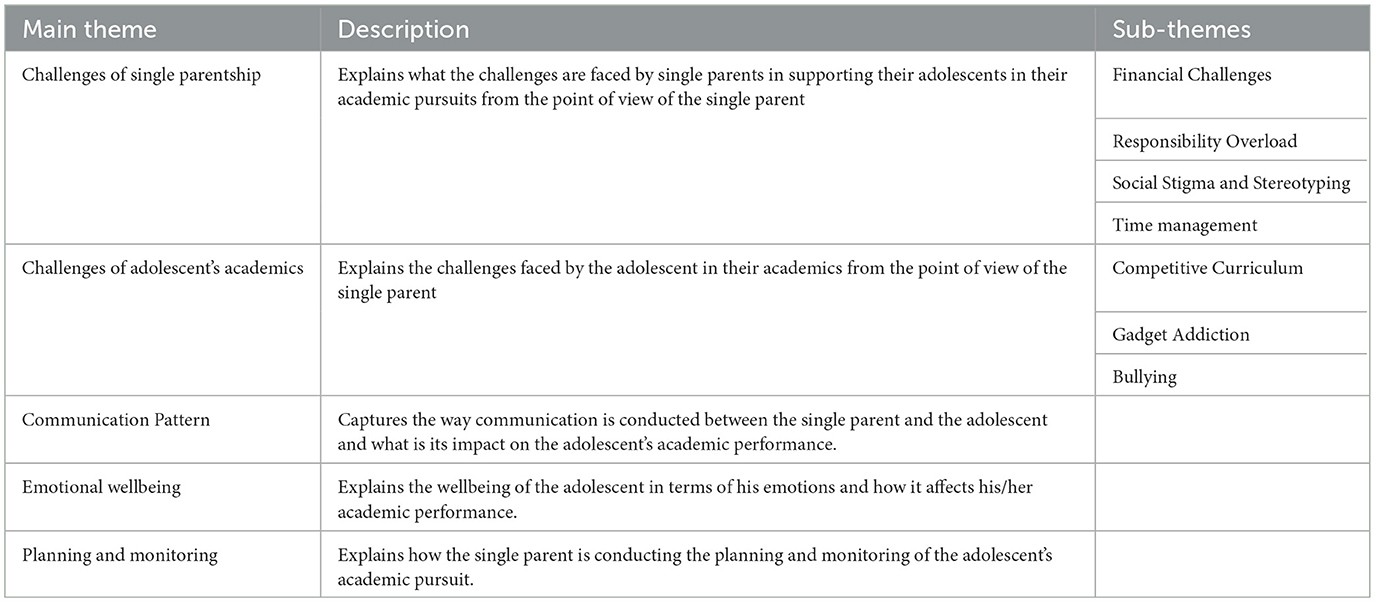

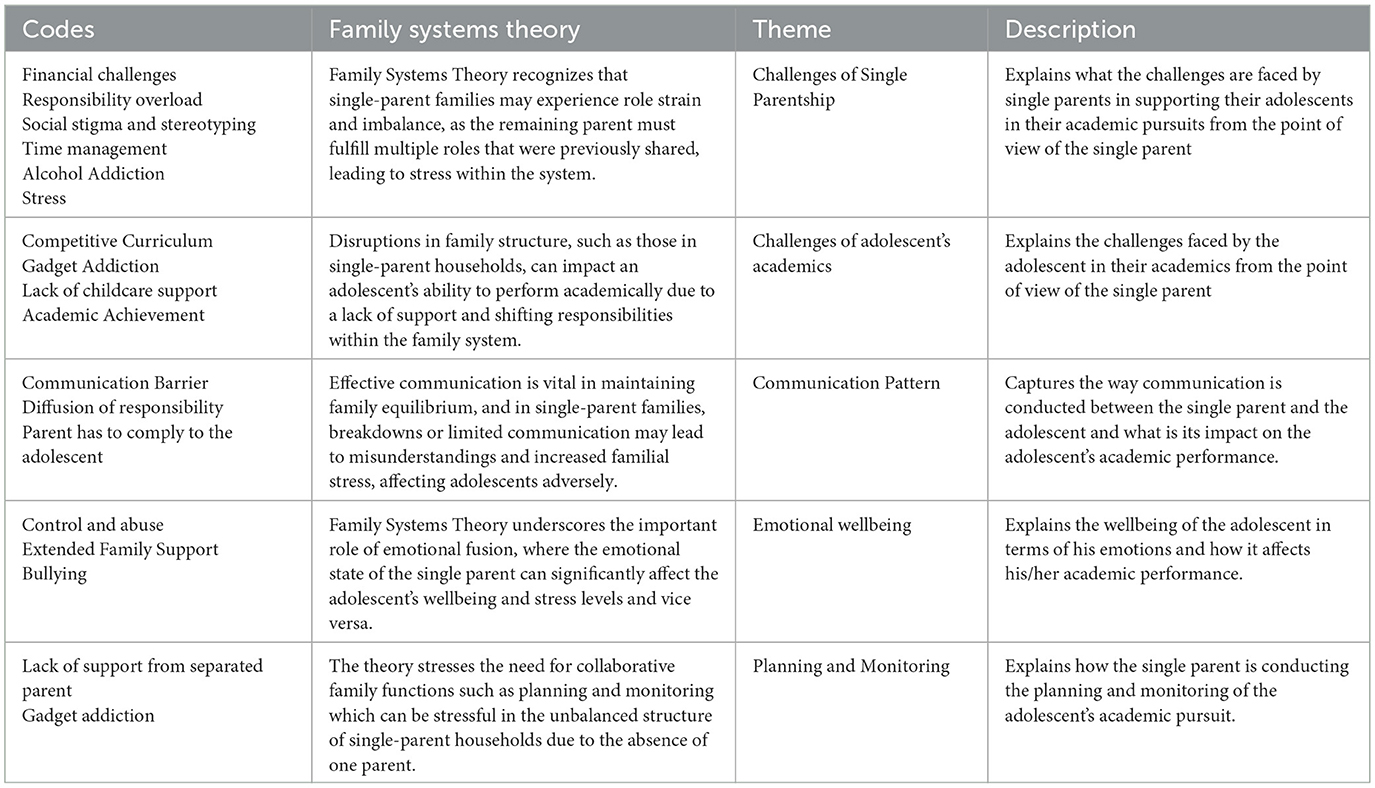

Justification for themes, sub-themes

Quotes, codes, sub-themes and themes extraction from transcripts are tabulated in Table 3 and the emerged Thematic representation is depicted in Table 4.

Our data analysis method also emphasizes on following aspects:

1. Critical self-awareness: the researcher explicitly acknowledged their own biases, assumptions, and theoretical stances throughout the analysis.

2. Dialogue with data: the analysis prioritized the voices and experiences of participants, allowing themes to emerge organically from their narratives.

3. Iterative engagement: the coding and theme development processes was cyclical, allowing for constant revisiting and refinement of interpretations.

4. Contextualization: themes were situated within the broader social and cultural context of single-parenthood and adolescent development.

Rigor

The confidence in the truth of the findings was enhanced through prolonged engagement with the data and through member checking. This member checking process involved creating a concise summary of the main themes and sub-themes, which was then emailed to four participants who had previously agreed to a follow-up review. They were asked to verify if the interpretations accurately reflected their experiences and perspectives. All four participants confirmed the resonance of the themes, providing minor suggestions for clarifying the wording of two quotes, which were subsequently incorporated. A detailed description of the participants' context and the study's setting, allowing readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other situations was captured during the interview and documented. Dependability was maintained through a rigorous process of reflexive thematic analysis, which involved keeping a detailed reflexive journal to document methodological decisions and personal biases throughout the research process. Furthermore, an audit trail consisting of audio recordings, interview transcripts, notes taken during analysis and discussions were maintained to ensure that the findings could be traced back to their original sources. To enhance credibility, triangulation was achieved by cross-verifying interview transcripts with field notes and member summaries. Two researchers independently coded 50% of the transcripts, achieving 85% inter-coder agreement, with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussions.

Results

After reviewing and analyzing the data in focus group discussions, researchers agreed up on five themes and sub-themes: challenges of single-parentship (four sub themes, Financial challenges, Responsibility overload, Social Stigma and stereotyping, planning and monitoring), Challenges of adolescent's academics (three sub themes, Effects of Gadget Addiction on Academic Performance, How Bullying adversely affects Academic Performance, Competitive Curriculum—a major hurdle in the uneven playground of competitive academics), Communication Pattern, Emotional wellbeing and time management.

Theme 1: challenges of adolescent's academics

Where five of the single-parents' have adolescents who were very good in studies and highly self-motivated, seven of them reported constant struggle with their adolescent's academics. Research consistently demonstrates that children living with single-parents score lower on measures of academic ability and achievement than do children with two continuously married parents (Amato et al., 2015).

Sub-theme: effects of gadget addiction on academic performance

Gadget addiction was identified as a major challenge, with 7 of the 12 participants reporting it as a primary concern. Parents explained that because they are often occupied with work or household chores, their adolescents have significant unsupervised time, which is frequently spent on mobile phones or laptops instead of on their studies. One of the parents reported that:

“He does not have any friends and does not like to go out and play. He is looking at the mobile phone all the time. If I try to take it away or ask him to study, he yells at me. He doesn't even spend half of that time for his homework.”

Another parent's report:

“I used to switch off the WIFI after a certain time. She used to go to a particular room and act like she was studying. Later I came to know that she was using neighbor's wifi and spending more time on the net. Even when it's time to study for the exams, she is scrolling more than usual, sharing her worries online than actually studying.”

This issue is understood within the framework of Family Systems Theory, which suggests that the absence of a second parent can limit the family's capacity for monitoring, making it more difficult to manage a child's digital habits.

Sub-theme: how bullying adversely affects academic performance

Another challenge raised by participants was bullying within the school environment, where other children would intimidate or tease their adolescent. One of the parents reported that:

“They called him mean words and prompted him to react. He got really angry and threw their water bottle at the ground. The class teacher came to know about this and punished my son. Then he told me and I reported to the head mistress. She saw the incident on camera and realized what happened and punished the other kids. after this incident my son had to be forced to even go to school.”

Participants expressed concern that while their children may develop resilience over time, these bullying incidents negatively impact their confidence and interest in going to school, which in turn affects academic performance.

Sub-theme: competitive curriculum—a major hurdle in the uneven playground of competitive academics

Participants described the difficulty of supporting their children through a highly demanding school curriculum. The lack of focus from a missing parent was seen as a considerable factor. One of the parents reported that:

“He is not studious at all. I wonder what is wrong with him. Whenever I make him study, he doesn't understand the concepts. He will not remember anything after a few days, even if he understands something. It's frustrating how he is such a failure at the school.”

The effort needed for getting good marks is very high in most of the syllabuses. Three single-parents changed their adolescents' schools multiple times, two others either changed syllabus or shifted from competitive topics such as science to creative topics such as fashion design.

Theme 2: challenges of single-parentship

In every single report from the twelve participants various challenges they face on a day to day basis due to various factors associated with the family structure were evident. Socio-economic status and economic independence and dependence have a profound impact on the wellbeing and adjustment of single-parents. Although gender parity was not achieved in the sample, the responses from single parents who participated in the study were largely consistent with findings from prior research. That study highlighted that, beyond economic challenges, a salient factor affecting wellbeing and social adjustment among divorced single parents in highly family-oriented cultures is the social identity associated with their marital status. This influence appeared to affect both men and women similarly, as no significant gender differences were observed in the present investigation (Bailey, 2007).

Sub-theme: financial strain and its adverse effect on academic performance

The biggest challenge that single-parents faced in self-reports was financial. But this contradicted the fact that most of them also reported that they did not have to cut down drastically on the adolescent's education or household expenses. For five families, a separated parent was sharing some of the financial burden such as paying for the school fees or sharing a percentage of his salary. But in the rest of the seven, only the single-parent's earnings were the source of supporting the household expenses as well as educational expenses. In general, the financial struggle is either in arranging expensive helplines such as external tuitions or affording entertainment such as costly toys or vacations, the lack of which can put the adolescent on a backfoot socially among his/her peers which will in turn cause low morale and reflect negatively in academic performance. One single-parent reported that:

“I am not a salaried employee; I earn month to month from my coaching. If I get sick for a few days, the money stops coming and that causes a lot of problems. I have to plan very carefully and cut down on expenses, forget extravagant parties or costly toys for my kid. I can't afford to get him tuition. Sometimes I manage to get old books from older kids that my kid can use so that I don't need to buy them. But it's not always possible. I have waited many weeks for me to get enough money so that I can buy textbooks for him.”

It is also observed that where the single-parent has good financial support, they are generally able to manage their single-parenthood without much hassle. One parent who had a company spends a lot of time with his adolescents and helps them plan, teach them subjects and does not feel it has added any pressure to his lifestyle. For those adolescents whose single-parents do not have good financial resources to send them to good schools or arrange for tuitions will struggle in getting quality education and good marks.

Sub-theme: responsibility overload and its adverse impact on academic performance

Single-Parents with adolescent kids must manage the entire household by themselves. Office work, paying bills, managing finances, cooking, household chores, helping their adolescent with subjects, visiting school and connecting with teachers, guiding their adolescent on various subjects about life and their body changes, making sure of the emotional health of the adolescent, health issues inside the house, socializing with neighbors, celebrating and participating in other people's parties etc, the list goes long. With one parent missing, they struggle to get everything done by themselves. This causes burn down as well as fatigue. To quote one parent:

“I have to manage all the work. Even if I am sick, I need to take care of them. Two kids who think they are adults but they are not. One kid needs support with subjects and the other one needs emotional support. Every year one of them will have an accident. Calling parents is an option but they are old. I put my kids in a non-regular school with minimal homework. But the responsibility of education is on us, so I need to spend time for that also.”

Based on Family systems theory, a single-parent's health problems can be extremely stressful due to the lack of support within the family unit. When the primary caregiver is ill, it can disrupt the system's equilibrium, leading to increased stress, anxiety, and potential for dysfunction. The presence of supportive grandparents can help alleviate these stressors by providing practical assistance and emotional support, thereby strengthening the family system and enabling the single-parent to cope more effectively.

Sub-theme: adverse effect of social stigma and stereotyping in academic performance

Society judges single-parents due to social conditioning. This happens even in corporate offices amidst well-educated people. This causes them to be less confident and makes their presence felt and poses challenges to their career progress. One parent reported thus:

“I have a good manager, it's a blessing. He understands. But my colleagues, particularly women in senior roles who are from regular families, keep telling me like you are doing all this to get attention, you should slow down, etc. They do not have the financial freedom that I have so they think I am doing well off. Nor do they have any decision-making skills or power. They do not see that it comes with a lot of burden though. This kind of treatment stresses me out and some days I take it on my kid. When I am stressed at the workplace I can't help him with his studies or even exam preparations.”

Sub-theme: importance of time management in academic performance

One theme which ten of participants out of twelve were struggling with is time management. Many of them reported concern that they still do not know how to manage time. They are not able to find time to talk to their adolescents, let alone help them in their studies. One parent reported thus:

“I take tuitions for other kids to earn money. But I need to leave the house by the time my kid comes back from school to take tuitions. By the time I am back, he has already wasted his time looking at mobile. I am not able to even speak to him. How can I teach him or even check on his progress if I am not even finding time to talk to him.”

In the effort to divide the time among the various tasks at hand, in many cases spending time with their adolescents is ignored by many single-parents. This causes emotional disconnects and affects overall wellbeing of the adolescent and has a negative impact on their academic success. Teachers can support adolescents from single parent families by using professional development strategies to help them build time management and self-regulation skills. The increased investment in professional development links directly with adaptability and the provision of structured support that helps students organize and prioritize their academic and personal responsibilities (Juhji et al., 2023).

Theme 3: communication pattern

Two distinct communication patterns were observed among the participants. The first group of single-parents (five in number) made a conscious effort to connect and spend quality time with their adolescents every day. This regular interaction had a positive impact on the adolescents' overall wellbeing and academic performance, highlighting the crucial role of communication in an adolescent's life-particularly in terms of life satisfaction, depending on family type. These findings challenge prevailing prejudices about single-parent families in our society, demonstrating that such families provide supportive developmental contexts for children's wellbeing (Camacho et al., 2020). Additionally, this group reported a better understanding of their adolescents' daily experiences. One of them reported:

“He goes to school in the morning. He is back by four. I have time till then to work. After he comes, I give some snacks. Then he goes to play and comes back. I spend 1 to 1.5 hrs. with him. Then he helps me with household work. Then we have a good time with each other. I share with him what I was doing, he also shares what happened with him at school. A little extra time we spend together is when his exams come which helps in his revisions.”

The second set of single-parents (seven in number), do not spend such communication time with their adolescent. This is also closely related to the time management sub theme. Some of the things they have tried include taking less responsibilities at office, moving out of India to have an easier work schedule, cutting down on social activities etc. One of them reported.

“She sometimes hides things from me. I am struggling a bit with her. She does have a few good friends. She does not share a lot with me. I do not know how she is doing in her studies. When she get bad marks, she blame it on random things.”

Particularly for the single-parent who cuts short on his/her social involvement etc. to support adolescent's academics, when the adolescent grows up and has friends of their own and do not share with the parent, it can be very isolating. More importantly, when there is a gap in the communication, single-parents fail to understand the emotional stress their adolescents are going through, if they are getting bullied, if someone is misbehaving with them etc. and fail to understand why their adolescents are not able to perform well at school.

Theme 4: emotional wellbeing

There have been a few studies about the way children get affected by separation of parents. It is revealed that the value acquisitions, which is also an indicator of social emotional development, are negatively affected in children from the divorced family. Children from divorced families were more adversely affected than parents and they feel the negative effects of the divorce in their later lives (Sahin, 2020). In the current study also, eleven single-parents reported that their adolescents showed anxiety, insecurity, depression, aggression etc after separation. But gradually those behavioral patterns came down over time in most of the cases. One single-parent said this about the behavior of her adolescent:

“He can get very aggressive. He behaves like a little boy at times. He does not understand our situation. He doesn't want to study. He spends more time on the phone, TV etc. than with books. His focus changes rapidly which creates problems for me. Whenever I try to have a discussion, he is always yelling and shouting. Most of the time I ask him to go with his father. But he refuses to go. His teachers have given up on him. few times he failed and had to repeat one year.”

Four of the twelve single-parents are taking their adolescent to counseling. Emotional wellbeing of the adolescent would be an important factor for his/her academic success.

Theme 5: planning and monitoring

Planning and monitoring are consistently mentioned by most of the single-parents who participated in the research which indicates the importance of it. Most single-parents seem to struggle with planning and monitoring their adolescent's day to day academic progress. Turning to items representing monitoring at home, both single mothers and single fathers were less involved than a parent of two-parent families. When it comes to day-to-day activities, such as monitoring homework, parents may need more time and knowledge to help their children (Nonoyama-Tarumi, 2017). In the current study, there were a couple of rare cases where the parent was particularly focused on planning out the subjects, homework, tuition, revision etc. In some of the other cases, adolescents were self-motivated and managed studies on their own where parents were not involved in the planning. When the parent is involved in day-to-day planning of the educational pursuit, the adolescents would have the motivation and focus to achieve good results in their academics. As per one of the participants:

“She needs my help with scheduling her study activities on a daily basis. Otherwise she misses homework or important topics which get piled up later. I also have to continuously keep an eye on the progress throughout the day and week. If I miss, then she would either forget things or let them be. Then it will be bedtime or something and she won't have time to complete it. If some important concept is missed, it affects the following concepts also.”

This theme also links back to the sub-theme of gadget addiction that was discussed earlier. Since one of the parents is missing, the kids enjoy non-monitored time which could easily go into social media and unwanted activities.

Above Figure 1 presents a thematic model that illustrates the challenges identified in this study and their interconnections. The model shows how two primary themes, Challenges of single-parentship and Challenges of Adolescent's Academics, are composed of several specific sub-themes (e.g., Financial Challenges, Bullying), as indicated by the solid lines. Positioned centrally, the three themes of Communication Pattern, Emotional Wellbeing, and Planning and Monitoring act as crucial connecting factors. The dashed lines show that these factors mediate the relationship between the parent's struggles and the adolescent's academic difficulties. This model suggests that the challenges a single-parent faces do not directly cause academic problems. Instead, their impact is filtered through the family's internal processes such as the quality of their communication, their collective emotional state, and their ability to plan and monitor academic progress.

Discussion

This study explored various challenges single-parent families from urban and semi-urban areas in India face regarding their adolescents' education, guided by Family Systems Theory. The findings reveal a complex interplay between parental struggles, adolescent-specific academic hurdles, and the mediating roles of communication, emotional wellbeing, and monitoring. This discussion situates these findings within the broader academic literature, comparing the lived experiences of the participants to existing research to highlight both consistencies and unique contextual insights. The themes that evolved in the study and how they are supported by the conceptual framework of Family Systems Theory is tabulated in Table 5 and explained further.

The analysis of single-parent households in relation to adolescent education emphasizes that communication, emotional wellbeing, and active monitoring are crucial in addressing academic challenges. Many participants who took part in this research noted that they have poor communication with their adolescents on a regular basis which greatly affects family dynamics which in turn created a stressful atmosphere at home and resulted in poor academic performance of the adolescent. Wherever the communication between the single-parent and adolescents were well structured, they were able to emotionally support each other and the family atmosphere was pleasant. This dynamics is well explainable with the Family systems theory which highlights the connected nature in which individuals operate in a family.

Open communication fosters trust, emotional stability, and academic performance. Research highlights that ongoing discussions about academic goals and challenges significantly impact students' emotional and academic outcomes (Yau et al., 2022). For single-parents, consistent engagement in these discussions combined with emotional support can improve academic persistence and success (Guo et al., 2025). It was noted that among the 8 urban participants, 5 of them reported issues with communication with the adolescents whereas this was highlighted by only 1 among the 4 semi-urban participants.

Emotional wellbeing is highlighted as a pivotal concern for both parents and adolescents. The capacity to maintain emotional stability and resilience, particularly in the face of academic challenges, is crucial for single-parents managing their dual responsibilities. The emotional fusion that is portrayed in the Family systems theory could be a double edge sword in case of single-parents, since the missing parent causes an emotional imbalance which needs to be compensated for by the lone parent. How this can play out in practical life was shown in both ways in the interviews. In general, when the single-parent could stay on top of things emotionally, it was found that the adolescent felt emotionally well supported whereas in cases where the single-parent was struggling to balance themselves emotionally, the adolescent also reflected that struggle which resulted in a stressful atmosphere at home as well as poor academic performance. The emphasis on emotional wellbeing during interviews underscores its importance, with some parents employing strategies such as yoga and meditation to mitigate emotional imbalance. Recent research indicates that adolescents from single-parent families often experience lower emotional wellbeing, which can negatively affect their academic performance. The reduced parental involvement and financial strain common in these households contribute to higher stress levels, leading to difficulties in maintaining academic focus and motivation. Emotional support from schools and peers can mitigate some of these effects, but the challenges remain significant (Yaw, 2016). Emotional stability in the home environment is crucial for supporting their academic success (Leerkes et al., 2011). The financial strain reported by our participants mirrors the findings of Eamon (2021) and Morelli et al. (2022), who quantitatively established the economic disadvantages of single-parent households. However, our qualitative data adds a crucial layer of nuance, revealing how this financial precarity translates into educational disparity.

Effective planning and monitoring are essential strategies for single-parents to stay informed about their children's academic progress, identify potential issues early, and provide necessary support. Collaboration with educators and peers is recommended to further reinforce this supportive network. The involvement of single-parents in their children's planning processes reflects the expectation of parental guidance during critical decision-making periods, such as subject selection. Given the potential limitations in adolescents' knowledge, the guidance of a parent is crucial to ensure well-informed decisions. Additionally, single-parents must closely monitor their children's use of technology, as deviations during this critical developmental stage could have long-lasting consequences. Research shows that parental involvement, including effective planning and monitoring, can significantly boost academic outcomes for adolescents. Also, their participation will enhance academic and career achievement in their children (Krishnan and Lasitha, 2019). Adolescents with single-parents benefit from active engagement in their academic journey, such as monitoring technology use and planning schoolwork, which helps mitigate potential academic issues early on. This involvement fosters a more structured and supportive learning environment, even in single-parent households (Choe, 2020; Chung et al., 2020). Parents in our study described not just the inability to afford resources like private tuition, but also the “time poverty” that resulted from needing to work longer hours, a direct link to the theme of responsibility overload. This finding resonates with the work of (Rani, 2006), who connected time management struggles in single-parent families to adverse academic outcomes. Thus, our study suggests that financial strain and responsibility overload are not separate issues but a compounding cycle where a lack of money necessitates more work, which in turn reduces the time available for parental involvement-a cornerstone of academic support.

The above themes are the connection between single-parents and challenges faced by Adolescents. The fourth theme that evolved from the study was ‘Challenges of adolescent academics. While there are a lot of challenges faced by the adolescents themselves in their academic pursuit, the following emerged as three major sub-themes.

a. Gadget Addiction: One of the major challenges for adolescents that emerged from the study was gadget addiction. This is also connected with other themes such as time management, planning and monitoring etc. Social media and gaming proved to be a common issue which consumed precious study time and hindered concentration. This theme emphasizes the need for digital literacy, strict vigilance from single-parents, setting clear boundaries and targets and encouraging alternative interests to promote healthy habits. While certain researches indicate that, the association between digital technology use and adolescent wellbeing is negative but small, explaining at most 0.4% of the variation in wellbeing (Orben and Przybylski, 2019), some other researches indicate that adolescents who excessively use their smartphones, especially for non-academic purposes, experience adverse effects on their academic achievements and are less likely to engage in effective learning strategies or goal-oriented behaviors (Yoon and Yun, 2023). But based on the interviews this emerged as one of the sub-themes, indicating that this is a bigger devil when it comes to the adolescent's academics. Our study builds on this by suggesting a mechanism rooted in family structure: gadget addiction appears to be exacerbated by the reduced parental monitoring capacity that stems directly from the parent's responsibility overload. While parents in two-parent households also struggle with this issue, the single-parents in our study felt uniquely ill-equipped to set and enforce boundaries due to their own exhaustion and time constraints.

b. Bullying: bullying and the intimidation it causes was seen to drag down adolescents' sense of security in many cases, negatively impacting their academic performance. Out of seven participants who reported that their adolescents are not conducting an open communication with them, it's possible that some of those adolescents are victims of bullying and are too frightened or timid to discuss it. Even though online bullying is also a possibility, none of the single-parents talked about the online mode of bullying. The absence of one parent can contribute to a lack of emotional support and monitoring, making these adolescents more vulnerable to bullying behaviors in school. This can lead to increased mental health issues and poor academic outcomes. Adolescents from single-parent families may be more vulnerable to bullying, which can further complicate their academic performance, as they often lack the emotional and social support needed to cope with such experiences. Studies suggest that bullying can lead to increased anxiety and decreased academic motivation, making it difficult for these adolescents to focus on their studies (Halliday et al., 2021). The contribution of our study is in linking bullying directly to communication patterns within the family. We found that adolescents who had open communication with their single-parent were better equipped to report and process bullying incidents. This supports the broader literature on the protective role of strong parent-child communication (Camacho et al., 2020) and suggests that fostering such communication is a critical, targeted intervention for single-parent families. Hence it is very important to educate both parent and kid to deal with bullying. Emphasizing the importance of fostering open communication about bullying, providing safe reporting mechanisms, and advocating for safe environments. Communication channels with schoolteachers is very important and during discussions single-parents did highlight the same.

c. Competitive Curriculum: the demands of the competitive curriculum were another recurring topic in the discussions. Participants described how their adolescents were overwhelmed by heavy workloads and the constant pressure to perform at par with kids from normal families with support from both parents. Lack of time and financial resources to seek external help is amplifying the problem for adolescents of single-parents. Adolescents from single-parent families often face difficulties in adapting to highly competitive curriculums due to the lack of adequate parental guidance and emotional support, which can lead to struggles in managing academic pressures (Akishina et al., 2022). These challenges may exacerbate their academic struggles, making it harder to compete effectively with peers from dual-parent households where support is more readily available.

While above themes are the challenges faced by adolescents in the pursuit of their academics, following themes are the underlying challenging reasons that single-parents are battling. Following four major sub-themes got spun out of the fifth major theme that got evolved in this study, namely, Challenges of single-parents.

a. Financial Challenges: this is one the biggest differences for a single-parent household. Participants described the struggle to afford basic needs, essential educational resources, private tuition, and extracurricular activities. Findings are in line with the current research, studies have highlighted that adolescents from lower-income, single-parent households tend to have reduced academic achievement due to the compounded effects of financial strain and limited parental involvement in education (Eamon, 2021). Financial challenges are not only eating away available time, it is also creating constraints around arranging for tuitions to augment schooling. This theme emphasizes the need for financial assistance programs, targeted scholarships, and community resources to offer some fair chance of competition for students from single-parent homes.

b. Responsibility Overload: taking care of office work, childcare, household chores, cooking and taking care of their own wellbeing proved to be very stressful for many single-parents. Most of the participants indicated little or very limited support from the other parent. This overload often left them with limited time and energy to dedicate to their children's academics. It was also noted in most of the cases that there was no help from extended family or the community. At the same time, whoever has help from their parents, mother in particular, has found it to be a pivotal support system. Adolescents from single-parent families often face responsibility overload, which can negatively impact their academic performance. The increased responsibilities, such as household tasks or caring for siblings, can detract from time spent on studies, leading to stress and lower academic achievement. This challenge is amplified by the absence of adequate parental supervision and support, which is critical during academic transitions. Studies emphasize that responsibility overload can hinder academic performance by overwhelming adolescents and reducing their ability to manage schoolwork effectively (Lee et al., 2007). This sub-theme highlights the importance of extended family support, support networks, affordable childcare options, and flexible work arrangements to help single-parents manage their multiple roles effectively.

c. Social Stigma and Stereotyping: Social stigma and stereotyping were described by participants as adding to their emotional burden. Feeling judged due to their single-parent status made it difficult for them at the workplace. This is especially evident during the initial days of separation. Single-parents also mentioned finding ways like yoga, meditation and becoming immune to such judgements over the time. Interestingly there was one working mother who did extremely well in the office and even went ahead to make HR policy changes in her office to facilitate a flexible schedule for single-parents such as herself. Even though this example is a very positive one, such cases are extremely rare. Adolescents from single-parent families often face social stigma and stereotyping, which can negatively affect their academic performance. It was noted in the study that out of the 8 urban participants, only 2 reported social stigmas whereas 3 out of 4 semi-urban participants reported that they were facing such challenges. Stereotypes about family structure may lead to lower expectations from teachers or peers, contributing to diminished self-esteem and academic disengagement. The pressure of conforming to societal norms can create additional stress, leading to decreased academic motivation and performance (Sahib and Aldoori, 2025). This affects the emotional wellbeing of single-parents and trickles down the same toward adolescents. This sub-theme emphasizes the need for anti-stigma campaigns and awareness programs to shatter societal misconceptions about single-parenthood. Our findings suggest its unique manifestation within a collectivistic culture. Participants described feeling judged not just socially but also in professional settings, which is a dimension less explored in Western literature. This finding is consistent with research by Valsala et al. (2018), who noted the importance of social support for Indian adolescents' self-esteem. When the parent faces social isolation due to stigma, it can erode the family's social capital, limiting access to community support networks that might otherwise buffer against stress.

d. Time Management: This sub-theme emerged in close correlation with responsibility overload sub-theme. With so many tasks at hand, single-parents often find themselves in an array of conflicting priorities. Oftentimes, they tend to overlook their adolescent's academics as a top priority and tend to trust their adolescents with it completely or partially. Adolescents from single-parent families often struggle with time management, which can impact their academic performance. Juggling household responsibilities, part-time jobs, and academic tasks can overwhelm these adolescents, leaving little time for focused study or extracurricular engagement. The absence of a second parent to share responsibilities can exacerbate this issue, leading to decreased academic outcomes (Cosp and Saladrigas, 2019). Teaching time management skills is crucial in supporting their academic success. This sub-theme highlights the need for time management strategies, resource sharing platforms, and community childcare initiatives to alleviate the time pressure on single-parents.

Synthesis of findings through family systems theory

The five emergent themes are not isolated issues but are deeply interconnected, as explained by Family Systems Theory. The theory posits that a family is an emotional unit where the functioning of one member affects all others (Watson, 2012). The immense stress on the single-parent, stemming from the “Challenges of single-parentship” (Theme 2) such as financial strain and responsibility overload, directly impacts the “Emotional Wellbeing” of the adolescent (Theme 4). This emotional fusion means that a parent's anxiety can manifest as an adolescent's academic disengagement (Chen and Wu, 2022).

Furthermore, the practical constraints of time and resources impact the parent's ability to engage in effective “Planning and Monitoring” (Theme 5). This creates a vacuum that is often filled by the “Challenges of an Adolescent's Academics” (Theme 1), most notably gadget addiction, which 7 of the 12 participants identified as a primary concern. The parent's struggle to monitor, a direct result of being the sole caregiver, creates an environment where academic discipline can falter. Finally, these internal stressors impact the “Communication Pattern” (Theme 3) within the family. As parents become overwhelmed and adolescents retreat, the communication barriers can prevent families from addressing critical issues like bullying or academic anxiety, creating a cycle of disengagement (Camacho et al., 2020).

Implications for redefining educational professionalism

The challenges documented in this study are not merely private family matters; they are educational issues that demand a systemic and professional response from schools. The findings call for a redefinition of educational professionalism-one that is empathetic, context-aware, and actively dismantles systemic barriers for students from non-traditional families. This involves adapting school structures, communication methods, and support systems to the realities of single-parent households.

Fostering socio-emotional and academic support systems

The emotional and academic wellbeing of the adolescent is clearly linked to the stability of the family system. Educational professionals might adopt a holistic and often two-generational approach to support.

• Mandate for Trauma-Informed Practices: The presence of codes like “Control and Abuse” and “Bullying” implies that these students may be functioning in a state of chronic stress. The critical implication is the need for all professionals to be skilled in trauma-informed practices. This involves recognizing the signs of trauma and creating a classroom environment that promotes safety and healing rather than one that might inadvertently re-traumatize a student (Walkley and Cox, 2013).

• Adopting a Two-Generation (2Gen) Perspective: The finding that the parent's and adolescent's emotional states are intertwined implies that supporting the student requires a focus that includes the wellbeing of their parent. A professional who understands this connection can better contextualize a student's behavior and advocate for resources that support the entire family unit, recognizing that strengthening the parent is a direct pathway to promoting the child's success (Shonkoff and Fisher, 2013).

• The School as a Protective System: When familial supports are weak, the school's role as a source of stability becomes paramount. This implies that professionals have a duty to cultivate a school climate characterized by safety, predictability, and strong, positive relationships. In this context, a teacher or counselor is not merely an educator but a consistent, caring adult who can buffer the impacts of external stressors (Masten, 2014).

Rethinking equity, access, and school policies

Many current school practices inadvertently create barriers for single-parent families. Professionalism demands that these be actively identified and dismantled.

• Financial Challenges and Socioeconomic Awareness: The financial instability reported by single-parents implies that it could help educators to be aware of socioeconomic diversity. School-related costs, even minor ones, can create significant barriers. Professionalism in this context means actively designing inclusive activities and implementing policies to mitigate these “hidden costs” (Lareau, 2011).

• Moving from Anti-Bullying Policies to Anti-Stigma Practice: The vulnerability of these adolescents to bullying based on their family structure implies that generic anti-bullying policies are insufficient. Educators need training to recognize and dismantle their own and others' implicit biases and create a genuinely inclusive culture where family diversity is respected (Halliday et al., 2021).

• Equity in a Competitive Curriculum: The finding that these adolescents struggle with a competitive curriculum implies that a rigid, one-size-fits-all academic standard can perpetuate inequality. True educational equity is not about treating every student identically but about providing flexible support that acknowledges different home realities (Naim, 2024). Professionalism requires adapting expectations and providing resources to level the playing field (Burford et al., 2014).

Building collaborative and flexible partnerships

The traditional model of parent-teacher engagement is often ineffective for single-parents facing time scarcity and responsibility overload.

• Flexible and Proactive Communication: The immense pressure on single-parents implies that schools can develop flexible, multi-channel communication systems (e.g., text message updates, asynchronous digital check-ins) (Lyubitskaya and Shakarova, 2018). Proactive and positive contact from teachers at the start of the year can build a foundation of trust (Voltz, 1994). This varied approach shows respect for the parent's time and situation, changing communication from a parental duty to a shared, professional responsibility (Adams and Christenson, 2000).

• Schools as Co-Executors of Academic Management: The overwhelming nature of planning and monitoring for a single-parent implies that schools must act as an active partner in this process. Educators can support this by implementing systems that scaffold organizational skills for both students and parents, such as using structured planners and breaking down large projects into manageable steps (Racz et al., 2019). Furthermore, the ever evolving social context demands educators to continuously adapt themselves to the challenges of the present times such as gadget addiction. The importance of ongoing professional development as a means for teachers to adapt to evolving educational demands, particularly in the context of technological advancement (Juhji et al., 2025).

• Proactive and Centralized Information Systems: The “lack of support from a separated parent” highlights the potential for critical information gaps. Schools have a professional responsibility to establish clear communication protocols, such as online parent portals where all legally permitted guardians can access grades and assignments directly. This reduces the monitoring burden on the single-parent and ensures all responsible adults have the same information (Arini et al., 2024). Furthermore, implementing systematic Early Warning Systems (EWS) allows schools to provide targeted support before a student falls into academic crisis (Balfanz et al., 2007).

Learnings

It was observed that the reason for being a single-parent could be many, but the challenges single-parents are facing to provide quality education for their adolescents are very much similar. The way they overcome these challenges are also similar. Some of the sacrifices single-parents made for educating their adolescents were extraordinary. The extent to which single-parent families can be tormented by struggles such as lack of financial resources to effective communication between the single-parent and the child is remarkable. From the part of society and educational institutes in particular, the lack of awareness, acceptance and customized support systems for such students were noted multiple times. The need for action for supporting adolescents from single-parent families in their education from educational professionals and other social institutes was evident from the study.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study and a review of best practices, the following practical recommendations are offered for key people within the educational system. These steps are designed to close the professional practice gap and create a more inclusive, supportive, and fair environment for students from single-parent families. Modern technologies such as Neuroeducation can be employed by teachers, using techniques such as memory retrieval, cognitive load management and adaptive learning methodologies, Anandakumar (2024).

For Teachers

• Develop Flexible Communication Strategies: move away from relying on strict parent-teacher meeting schedules and notes in diaries. Proactively offer and use various communication methods, such as email, scheduled phone calls, or secure, school-approved messaging apps, to accommodate the different work schedules and situations of parents (Adams and Christenson, 2000).

• Practice Proactive and Positive Outreach: Contact all parents at the start of the school year with positive news or a simple introduction. This builds a foundation of trust and a good relationship, ensuring that communication is not only about problems and encouraging parents to see teachers as partners (Voltz, 1994).

• Undergo Training in Implicit Bias and Cultural Sensitivity: Take part in professional development workshops that focus on understanding different family structures, including single-parent families. This training should help educators recognize and challenge their own unconscious biases, which can affect their interactions with and expectations of both parents and students (Gonzalez, 2021).

For school counselors

• Serve as a Central Resource Hub: Make the counsellor's office the main point of contact and a safe space for single-parent families. Counselors should be knowledgeable about and able to connect families with both school resources (e.g., information on fee waivers, tutoring, special education services) and external community support services (e.g., mental health counseling, financial aid programs, legal aid) (Warren-Adamson and Lightburn, 2010).

• Facilitate Parent Support Groups: Create and lead voluntary peer support groups for single-parents in the school community. These groups can be a valuable place for parents to share experiences, exchange coping strategies, and feel less isolated, which helps build a stronger community network (Arkonac et al., 2017).

• Advocate for Systemic Change and Child Rights: Use the insights gained from talking with students and families to push for more inclusive school policies at the administrative level. Counselors should be champions for fairness, making sure that school practices are in line with the rights and best interests of all children, no matter their family structure (Amatea and Clark, 2005).

For school administrators and policymakers

• Audit and Revise School Policies for Inclusivity: Conduct a full review of all school policies, procedures, and documents-including enrolment forms, handbooks, communication methods, and event schedules-to find and remove language or requirements that might be exclusionary or create unintended problems for non-traditional families. For example, forms should use inclusive terms like “Parent(s)/Guardian(s)” instead of “Mother” and “Father” (Gallego-Jiménez et al., 2025).

• Integrate Diverse Family Structures into Teacher Training and Professional Development: require that teacher education programs and ongoing professional development for current educators include significant modules on supporting students from diverse family structures. This curriculum should be based on research and provide practical, evidence-based strategies for creating inclusive classrooms (Shen and Musyoka, 2023).

• Invest in and Prioritize School-Based Support Systems: Set aside dedicated funding to hire and keep qualified school counselors and social workers. Also, invest in school-wide programs that support family wellbeing, such as digital wellness workshops for parents and social-emotional learning programs for students. Recognizing that supporting the family is essential to achieving educational goals is a core principle of the NEP 2020 and a critical investment in student success (Kumar et al., 2016).

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be noted. The small sample size (N=12) and the use of snowball sampling mean that the findings cannot be applied to all single-parent families in India. Out of the 12 respondents, there was only one male single parent, which might pose risk of bias and generalizability as the collected data might not fairly represent the experience of single fathers. Furthermore, the use of social media to recruit participants without controlling for demographic variability might result in low external validity. The study is exploratory and offers insight into a specific set of experiences. Additionally the study only captures the parents' perspective. The voices of the adolescents themselves are essential for a full understanding of the issues and are a necessary part of future research. Given that the primary subject is adolescent Education, including their voices could have enhanced the depth and authenticity of the results.

Future studies should try to address these limitations. Research with larger, more diverse samples with sufficient representation from single mothers and single fathers could provide a more complete picture. Mixed-methods studies could be used to measure how common the challenges identified here are and to check the effectiveness of the recommended actions. Most importantly, future research can explore the perspectives of adolescents from single-parent families to confirm the findings, explore their viewpoints and create support strategies that are focused on the students' own needs and experiences. Comparative studies looking at the differences in support between public and private schools, or in urban vs. rural areas, would also add valuable depth to the field.

Conclusion

This study reveals that adolescents from single-parent families face intertwined academic and emotional challenges, rooted in both household constraints and broader societal attitudes. Importantly, our findings underscore the central role of educational professionals in mitigating these challenges. A key takeaway is that educational professionalism entails actively adapting school policies and teaching practices to support single-parent households, rather than expecting these families to fit conventional molds. In concrete terms, this means flexible communication methods, targeted resource support, and inclusive classroom cultures that recognize diverse family realities.

While our sample is small and context-specific, the emergent themes suggest avenues for future research and practice: for example, investigating whether the correlations between gadget use and academic performance are stronger in single-parent families (as our parents suspected), or evaluating school-based interventions designed with these findings in mind. Overall, by turning parents' experiences into actionable guidance, we hope this study empowers educators and policymakers to create more equitable educational environments. Through enhanced collaboration between schools and single-parent families, and by grounding interventions, we can move toward the equitable support envisioned by the theme of educational professionalism.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Data involves confidential matters. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2FfcmFqYWxha3NobWlAY2IuYW1yaXRhLmVkdQ==.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. RS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. AT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor PG declared a shared affiliation with the author(s) PP, RS, and AT at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We have used Gemini 2.5 (Gemini Pro) to edit the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, K. S., and Christenson, S. L. (2000). Trust and the family-school relationship: an examination of parent-teacher differences in thinking. J. Sch. Psychol. 38, 477–497. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00048-0

Akishina, E. M., Olesina, E. P., and Mazanov, A. I. (2022). Influence of competitive activity on the development of self-realization among adolescents. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 11, 927–935. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v11i2.22361

Amatea, E. S., and Clark, M. A. (2005). Changing schools, changing counselors: a qualitative study of school administrators' conceptions of the school counselor role. Profess. Sch. Counsel. 9:2156759X0500900101. doi: 10.1177/2156759X0500900101

Amato, P. R. (2005). The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. Future Child. 15, 75–96. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0012

Amato, P. R., Patterson, S., and Beattie, B. (2015). Single-parent households and children's educational achievement: a state-level analysis. Soc. Sci. Res. 53, 191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.05.012

Anandakumar, R. (2024). Neuroeducation: understanding neural dynamics in learning and teaching. Front. Educ. 9:1437418. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1437418

Arini, M., Suryanto, F., Puspita, G., and Primastuti, H. I. (2024). Enhancing school health monitoring through teacher training and web-based applications. BIO Web Conf. 137:02004. doi: 10.1051/bioconf/202413702004

Arkonac, S. E., Frazer, J., Horgan, R. J., Kracewicz, A., and Al-Naimi, L. (2017). “Parentcircle: helping single parents build a support network,” in Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York, NY: ACM), 26–32. doi: 10.1145/3027063.3049271

Bailey, S. J. (2007). Family and work role-identities of divorced parents: The relationship of role balance to well-being. J. Divorce Remarriage 46, 63–82. doi: 10.1300/J087v46n03_05

Balfanz, R., Herzog, L., and Mac Iver, D. J. (2007). Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: the critical role of early warning systems. Educ. Psychol. 42, 223–235. doi: 10.1080/00461520701621079

Berghammer, C., Matysiak, A., Lyngstad, T. H., and Rinesi, F. (2024). Is single parenthood increasingly an experience of less-educated mothers? A European comparison over five decades. Demogr. Res. 51, 1059–1094. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2024.51.34

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exercise Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brown, R., and Johnson, L. (2021). The impact of family structure on adolescent academic performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 113, 123–135. doi: 10.1037/edu0000456

Burford, B., Morrow, G., Rothwell, C., Carter, M., and Illing, J. (2014). Professionalism education should reflect reality: findings from three health professions. Med. Educ. 48, 361–374. doi: 10.1111/medu.12368

Camacho, I., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Rivera, F., Moreno, C., and Gaspar de Matos, M. (2020). Communication in single-and two-parent families and their influence on Portuguese and Spanish adolescents' life satisfaction. J. Fam. Stud. 26, 157–167. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2017.1361856

Chen, H., and Wu, S. (2022). Emotional stress in single-parent families: effects on adolescents' school performance. Child Dev. 93, 482–493. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13728

Choe, D. (2020). Parents' and adolescents' perceptions of parental support as predictors of adolescents' academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 116:105172. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105172

Chung, G., Phillips, J., Jensen, T. M., and Lanier, P. (2020). Parental involvement and adolescents' academic achievement: latent profiles of mother and father warmth as a moderating influence. Fam. Process 59, 772–788. doi: 10.1111/famp.12450

Cooper, K., and Stewart, K. (2021). Does household income affect children's outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Child Indic. Res. 14, 981–1005. doi: 10.1007/s12187-020-09782-0

Cosp, M. A., and Saladrigas, N. G. (2019). Time distribution in single-mother households. Living with others as work-life balance strategy La distribución del tiempo en los hogares monoparentales de madre ocupada. vivir con otros como estrategia de conciliación. Rev. Int. Sociol. 77:e131. doi: 10.3989/ris.2019.77.3.18.027

Cutler, N. A., Halcomb, E., and Sim, J. (2021). Using naturalistic inquiry to inform qualitative description. Nurse Res. 29, 7–12. doi: 10.7748/nr.2021.e1788

Dharani, M. K., and Balamurugan, J. (2024). The psychosocial impact on single mothers' well-being – A literature review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 13:148. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1045_23

Eamon, M. K. (2021). Poverty, parenting, peer, and neighborhood influences on young adolescent antisocial behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 56–72.

Fox, K. R. (2020). “Home-school pathways: exploring opportunities for teacher and parent connections,” in Handbook of Research on Leadership and Advocacy for Children and Families in Rural Poverty, eds. H. C. Greene and B. S. Zugelder (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 382–401. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-2787-0.ch018

Gallego-Jiménez, M. G., Jáñez González, D., and Torrente Torres, B. (2025). Inclusive education and language competence: the role of thinking-based learning Educación inclusiva y competencia lingüística: El rol del aprendizaje basado en el pensamiento. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 10. doi: 10.31637/epsir-2025-1491

Garcia, M. R., and Tillmann, E. (2025). Influence of family composition on academic performance Influência da composição familiar no desempenho acadêmico Influencia de la composición familiar en el rendimiento académico. Rev. Brasil. Estudos Popul. 42:e0300. doi: 10.20947/S0102-3098a0300

Garg, R., Melanson, S., and Levin, E. (2007). Educational aspirations of male and female adolescents from single-parent and two biological parent families: a comparison of influential factors. J. Youth Adolesc. 36, 1010–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9137-3

Gonzalez, A. M. (2021). “Positive exemplar exposure: a method for early implicit racial bias change,” in Cultural Methods in Psychology: Describing and Transforming Cultures (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 296-323. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190095949.003.0010