- The Levinsky-Wingate Academic College, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel

Introduction: This study explores how inclusive education is addressed in teacher training programs in Israel, with a focus on the perspectives of participants who are actively engaged in the process.

Methods: Using a qualitative, inductive design, 34 semi-structured interviews were conducted with teacher candidates, pedagogical counselors, program heads, school principals, and mentor teachers across four teacher education colleges and eight partner schools.

Findings: Thematic analysis revealed four interrelated themes: the value of practical fieldwork experience, the need for stronger theoretical foundations in inclusion, challenges in bridging theory and practice, and the importance of professional development for teacher educators. Methodological triangulation across diverse roles enhanced the validity of the findings and allowed for a multidimensional understanding of the systemic and practical challenges in preparing teachers for inclusive classrooms.

Discussion: The findings identified a clear need for reform, redesigning the teacher education programs, and a need for guidelines regarding the curriculum of teacher-training programs for inclusive education. The study concludes with recommendations for redesigning teacher education programs, including closer integration of theory and practice, embedding Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, and supporting educators through structured mentorship and ongoing training.

Introduction

There is a crucial need for systemic reform in teacher education to enable authentic and relevant training for inclusive education (Lewis et al., 2019). However, providing teacher candidates with the necessary training is a challenge that is seen in a global context. An analysis that examined the provision of inclusive education training within teacher training programs showed that only 61% of 168 countries that participated in the evaluation provided aspects related to inclusion. Furthermore, only 10% of 196 countries have education laws regarding inclusion, and only one-third indicate inclusive education in teacher training (Global Education Monitoring Report [UNESCO], 2020). Unfortunately, inclusive education policies often advance superficial terminology revisions while central education policies remain unchanged.

In 2018, Israel amended its special education law to move from a system that focused on integrating children with special needs into an inclusive education system that recognizes each pupil’s diverse and specific needs in the whole class and tailors curricula and instruction accordingly. The primary responsibility for all pupils, including those with special needs, rests with the regular teachers, with special education professionals providing support (Kimhi and Bar Nir, 2024). Like many other countries, Israel did not stipulate including inclusive education in teacher education programs. This study examines the status of the Israeli teacher education programs, recognizing that the teacher candidates must get appropriate training to acquire the broad knowledge and capabilities necessary to teach in heterogeneous classrooms.

Inclusive education aims to increase accessibility, presence, and active participation in the school life of all pupils, including those with disabilities or other disadvantages. To develop positive attitudes regarding inclusive education, teachers and teacher candidates need to acquire relevant knowledge, psycho-pedagogical skills, and a powerful sense of competency to provide optimal and equal education for all pupils in the community (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a,b; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2020). As part of an effort to develop guidelines for an appropriate teacher-training curriculum, the current qualitative study examined existing and emerging processes concerning inclusive education implemented in teacher colleges in Israel and looked at allegedly absent curriculum components. The overarching aim is to advance clear guidelines concerning teacher training programs regarding inclusive education training and advance the adaptation of the training programs so they become an integral part of the policy framework for inclusive education. We note, however, that international organizations, such as the United Nations (UN), the European Commission, and the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a), caution that the disconnection between teacher education institutions and local contexts can challenge the ability to prepare teachers for inclusive education. Without providing appropriate support, inclusive education can be detrimental to the students in the schools (Gagnon et al., 2023).

Inclusive education

The success of inclusive education is closely linked to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. A recent review examining the optimal design of pre-service inclusive teacher education programs found that teachers’ sense of efficacy and the content of their training significantly influence these attitudes (Khamzina et al., 2024). Teacher efficacy, as defined by Bandura (1982), refers to educators’ belief in their ability to promote student learning and achieve desired educational outcomes. In the context of inclusive education, this translates to successfully facilitating inclusive practices in diverse classrooms (Lindner et al., 2023). This is established based on the teachers’ positive attitudes toward inclusion, appropriate knowledge, teaching abilities, adapted pedagogical tools, and support from school leaders (e.g., principals, inspectors) and the community (Desombre et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2018). Therefore, comprehensive support for the education sector and clear, strategic guidelines for teacher education programs are essential. Such systemic support enables the effective implementation of inclusive education and facilitates tailored responses to the needs of heterogeneous classrooms (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a,2020). In their analysis of 36 teacher education programs, Khamzina et al. (2024) found that those integrating both theoretical instruction and practical experience were more effective in fostering positive attitudes toward inclusion. Fieldwork and classroom experience help pre-service teachers develop practical skills and apply their theoretical learning in real-world settings, thereby enhancing their readiness to support diverse learners. According to the Global Education Monitoring Report (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2020), teacher training programs should not highlight inclusion as a specialized, individual subject but as a core element of general teacher preparation. Inclusive teacher education should address issues such as instructional techniques, assessment, and classroom management skills, including teamwork, thereby covering multiple aspects of inclusive education. The personalized learning inherent in inclusive education places the learners at the center of the learning process, enabling them to advance according to their needs, abilities, and individual development (Sharma and Spencer, 2018; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2020). This approach significantly improves children’s learning outcomes (Liu and Potmesil, 2025). It is based on the pupil’s strengths and establishes the diversity between learners as a given element within the classroom. Inclusive education adopts the universal design of learning (UDL) principles since they facilitate accessible teaching and learning methods adapted to all pupils in the classroom (Baldiris Navarro et al., 2016; Lowrey et al., 2017; Slee, 2018). UDL has three guiding principles. The first deals with engagement and ways to immerse learners in their learning experience; the second deals with forms of expression, which enable learners to express their abilities and knowledge in a variety of ways, and not only via tests and written works. The third principle involves representing information in multiple formats (Baldiris Navarro et al., 2016).

If all pre-service training programs included key components such as inclusive pedagogy, practical experiences with diverse learners, and training in UDL, implementing inclusive education would likely be much more effective and sustainable. Unfortunately, many teacher education programs worldwide still lack these essential elements (Global Education Monitoring Report [UNESCO], 2020; Lewis et al., 2019). The context and approach to teachers’ education for inclusion vary across countries and educational institutions (Ackah-Jnr et al., 2025). Nonetheless, several countries have taken decisive steps to reform their teacher training systems to align with the principles of inclusive education. One notable example is Ireland. In 2012, the country extended the duration of both undergraduate and postgraduate teacher training programs to ensure teacher education for inclusion (Hick et al., 2018; Hick et al., 2019). The process involved the extension and reconceptualization of the programs, embedding mandatory content related to inclusive education. Following the reform, a study assessed the components of inclusive education within the teacher training programs and the readiness of teacher graduates in line with the “Profile of Inclusive Teachers” (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education [EADSNE], 2012; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2022). It revealed a growing commitment among teacher education institutions to inclusive education, particularly concerning recognizing student diversity. However, it also highlighted a tendency among some programs to prioritize special educational needs over a broader conception of inclusion, thus narrowing the scope of diversity addressed. Moreover, while teacher candidates demonstrated generally positive attitudes toward inclusive education during their training, these attitudes tended to decline in their first year of teaching. Many reported feeling underprepared in practical knowledge and classroom strategies (Hick et al., 2018; Hick et al., 2019).

Ireland’s reform efforts reflect a broader international movement toward inclusive teacher education. In Italy, inclusive education has been a legal mandate since the 1970s, with teacher training programs requiring all educators—general and support teachers—to complete coursework in inclusive pedagogy, including practicum experiences focused on co-teaching and collaboration. Nevertheless, initial teacher training is unspecialized, leading to questions about the teacher’s ability to supply adequate support to all students (Ianes et al., 2020). New Brunswick in Canada implemented province-wide reforms, via a model of inclusive schooling for all students. They also developed a personalized learning plan based on the students’ strengths and needs, and multi-leveled instruction employing UDL frameworks, reducing reliance on segregated classrooms (AuCoin et al., 2020). Finland’s internationally lauded teacher education system integrates inclusive pedagogy throughout its curriculum, preparing all teachers at the master’s level to give general and intensified support to all pupils (Takala et al., 2023).

Across these contexts, several common factors underpin successful implementation: strong policy commitment, the integration of inclusive principles throughout the teacher education curriculum, continuous professional development, and collaborative partnerships between academic institutions and communities. These international examples demonstrate that successful transitions to inclusive education in teacher training programs require systemic commitment, curricular integration, and sustained professional development. With these international examples in mind, the following section examines the trajectory of inclusive education reform in Israel, exploring how its teacher training programs have responded to similar challenges and to what extent they align with global best practices.

The reform for inclusive education in Israel

For the past few decades, there has been public and educational discourse about inclusive education in Israel, emphasizing the inclusion of pupils with special needs in general education classes. Since 1988, the Ministry of Education has been promoting the implementation of the Special Education Law (Knesset, 1988). Two main reports were published to evaluate the implementation processes: the Margalit Report (Margalit, 2000) and the Dorner Report (Dorner et al., 2009). These reports criticized the general classroom teachers’ lack of knowledge and tools to accommodate pupils with special needs. The reports addressed the negative perceptions and attitudes of the teachers regarding integration and their lack of trust in it. These attitudes align with the obvious: teachers do not accept educational reforms when the reform does not concur with the reality of their everyday lives in the classrooms (Baş, 2021). The amendment to the Special Education Law (Section 211, Knesset, 2018) led the system to a fundamental change, broadening from a focus on integrating children with special needs by placing them in general classrooms and meeting their specific needs individually to a comprehensive and more inclusive response for all pupils in the general classroom, providing appropriate accommodations for them, whatever their needs. According to the amendment, the general education staff is expected to take full responsibility for all pupils, including those with special needs. The special education staff has a supportive role. Like others, the success of this reform depends, among other factors, on the teachers’ positive beliefs in the reform (Baş, 2021). Therefore, teacher training programs must prepare the teacher candidates for this reform (Kimhi and Bar Nir, 2024).

In sum, legislation in Israel, as elsewhere, has promoted inclusive education in the education system. The expectation is that teacher-training programs prepare teacher candidates for teaching in inclusive classrooms (Hopkins et al., 2018). There is, therefore, a shift in teacher education, moving from traditional integrative responses such as implementing specific interventions for distinct struggling pupils to preparing all teachers to teach and work with diverse groups of learners (Florian and Camedda, 2020). This type of teaching demands a change in teacher training so that teachers will be trained to support and encourage all pupils to participate in educational opportunities (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a,2020).

The current study context

The traditional curricula in all the teacher-training programs in Israel include theoretical and practical aspects. The Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) is a 4-year degree based on programs that include, for the most part, a curriculum consisting of educational knowledge (e.g., methods of instruction, foundations of education, educational psychology, philosophy and sociology, assessment, etc.), discipline knowledge (e.g., mathematics, literature, biology, etc.) and hands-on practical fieldwork. The practical fieldwork occurs within educational frameworks (e.g., kindergartens or schools) throughout the first 3 years. The teacher education programs differ between sectors (e.g., early childhood, elementary, secondary, and special needs education), thus preserving the difference between the types of teacher education needed to prepare teachers to teach diverse pupils (Florian and Camedda, 2020). These programs are composed of curriculum-based courses usually formatted as isolated one-semester units. Content knowledge about diversity and special needs is usually added to the existing programs as supplementary courses. In Israel, many pupils with diverse needs are included in general mainstream educational frameworks, and teacher candidates should, therefore, experience inclusive teaching in their fieldwork during their training program (Gilor and Katz, 2017; Kimhi and Bar Nir, 2024).

As reflected by the amendment to the Knesset (2018), implementing inclusive education within the education system in Israel has already begun, more so in the schools themselves than in the teachers’ training colleges. Although some teacher colleges have started the process, for the most part, the adaptations are minor and do not follow any clear or defined guidelines. This process necessitates a comprehensive adjustment of the teacher-training programs’ curriculum in general and within the general education programs (Kimhi and Bar Nir, 2024).

The current study is part of a wider study characterized by a multidimensional examination of teacher education for inclusive education within teacher-training colleges in Israel. This study is novel in its aim and multidimensional scope. It aims to qualitatively examine existing and emerging processes concerning inclusive education implemented in teacher colleges in Israel and to recognize that components may be missing in the training programs. The following question was posed: What are the optimal existing, emerging, and absent components within the teacher training programs in Israel that assist teacher candidates in teaching successfully in heterogeneous classes, which include pupils with diverse needs?

Materials and methods

The current study was designed as a qualitative empirical inquiry, grounded in the interpretation of cases and behaviors. This approach was chosen to explore the complex, context-specific experiences of those involved in teacher training for inclusive education in Israel. Aligned with the constructivist paradigm, which emphasizes multiple interpretations of reality and prioritizes participants’ voices (Denzin and Lincoln, 2000), a qualitative methodology enables the collection of rich, in-depth data. By engaging a diverse range of participants that included teacher candidates, pedagogical counselors, program heads, schoolteachers, and principals, the study offers a multidimensional understanding of both systemic structures and practical challenges. This breadth of perspectives contributes to a more comprehensive view of how inclusive education is implemented and experienced across different levels of the teacher education system. The inductive nature of the analysis allowed themes to emerge organically from the data, further supporting a nuanced understanding of current practices and informing the development of inclusive knowledge, attitudes, and skills among preservice teachers.

Participants

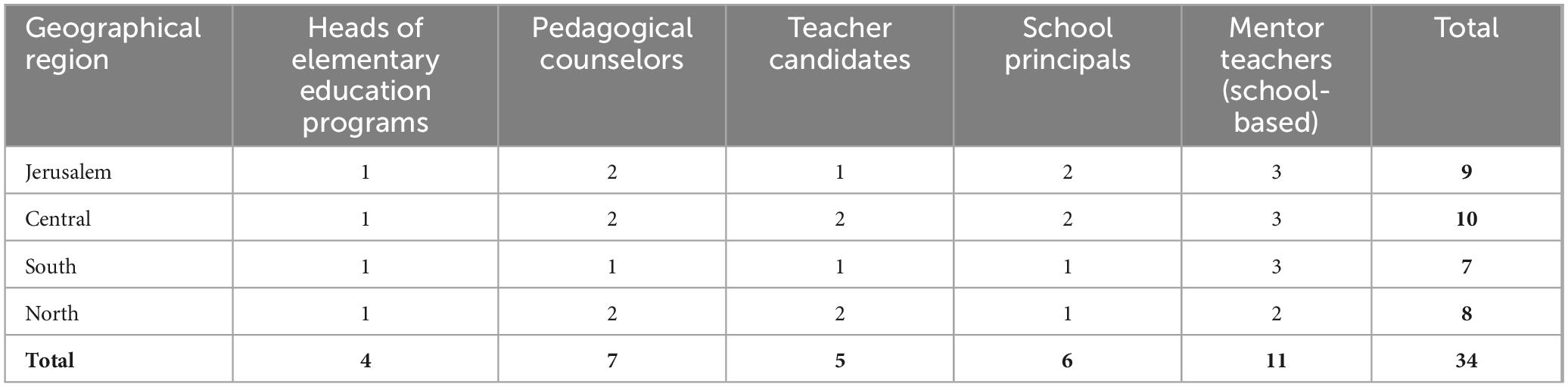

The study included 43 semi-structured interviews conducted with participants involved in teacher education and field-based training for inclusive education. Four teacher education colleges (out of the nine secular colleges in Israel) were purposefully selected to ensure geographic diversity—representing the south, center, Jerusalem, and north of Israel. These colleges had indicated early success in implementing inclusive education within their training programs and agreed to participate in the study.

Each college selected two elementary schools known for their effective collaboration in inclusive teacher training and obtained their consent to participate. In total, eight schools were included in the study. At each of the four colleges, interviews were conducted with the head of the elementary teacher education program, pedagogical counselors working with the selected schools, and teacher candidates placed at those schools who agreed to participate. School principals and mentoring teachers involved in student training were also interviewed. This structure allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the training process, as experienced by the participants within the teacher colleges and the school field. See Table 1 for participant groups and numbers.

All the program heads had at least 1 year of seniority as program heads and had been pedagogical counselors in the program for a minimum of 5 years. All the pedagogical counselors had at least 3 years of experience, and all had been teachers in general education schools before their work at the colleges. The program heads and pedagogical counselors taught at least one course connecting theory and practice. Except for one principal with only 2 years of seniority, they all had been principals for at least three or more years. All the participating teachers had been teaching for a minimum of 3 years.

Assessment measures

To enhance the trustworthiness of the data collected in this qualitative empirical study, we adopted some techniques suggested by researchers, including a reflexive, open, non-judgmental stance, and the pursuit of multiple voices (Creswell, 2007). The data were collected via thirty-four semi-structured interviews conducted with each of the participants to learn about their experiences in the context of inclusive education. Each of the thirty-four interviews was conducted as a semi-open conversation, with guiding questions added by the interviewer (see Appendix for the guiding questions). Thus, the interviewees could describe their experiences and feelings in their own terms and interpret them according to their understanding (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Each interview was approximately an hour long and was conducted in a location of the interviewees’ choosing, such as unused classrooms or offices. Following the COVID-19 lockdowns, some interviews were conducted online via the ZOOM platform. All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the project was obtained in line with the researchers’ institutional requirements (see section “Ethics”). All the participants signed written consent forms for their participation, and exit options before, during, or after the interviews were possible upon the participant’s request. The teacher candidates were approached by the head of the program, who asked if they would be willing to be interviewed. Candidates were given the option of refusing to participate and were assured of confidentiality. Participants were told that the study aimed to investigate the implementation of inclusive education in general teacher-training programs.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the project was obtained from the institutions’ Ethics Committees, and approval for the study was received from the Office of the Chief Scientist in the Ministry of Education. Two major ethical issues arose. The first was related to the teacher candidates’ identity since they were still candidates at the colleges when the interviews were conducted. The second was related to the researchers’ position since each researcher held a leading role in their college. It was decided that neither researcher would interview or collect data at her college to prevent feelings of inequality or pressure. All the data were transcribed using pseudonyms, thereby ensuring all the participants’ anonymity.

Trustworthiness and validity

Triangulation, peer debriefing, and member checking were used to strengthen the trustworthiness of the findings reported in the current study. For triangulation, information can be obtained from multiple data sources (Lub, 2015). The interviewees imparted different perspectives, as some relayed the perspective of the teacher-training colleges (program heads and pedagogical counselors), some of the educational field (principals and teachers), and the teacher candidates’ perspective that connected academia with the educational field.

To enhance the validity of the findings, the methodological triangulation of these diverse perspectives allowed the researchers to identify consistent patterns as well as contrasting viewpoints across the teacher education ecosystem. For instance, the overlap between teacher candidates’ concerns about inadequate preparation and principals’ perceptions of gaps in candidate readiness reinforced the credibility of that theme. Similarly, alignment between program heads and pedagogical counselors regarding the need for stronger theoretical grounding added weight to those findings. Triangulation in this context ensured that the themes identified were not based on isolated accounts but rather emerged from cross-confirmation among independent sources, thereby strengthening the validity of the analysis.

When analyzing the data, peer debriefing and member checking also established the trustworthiness and validity of the analysis (Lub, 2015). Peer debriefing was implemented as the researchers presented preliminary findings to a national educational forum established to advance inclusive education in teacher education in Israel. They presented their dilemmas and discussed viable solutions with the forum members. The researchers incorporated the insights and suggestions from the forum members in the analytic process. In addition, all the interviewees received their transcribed interviews and were asked to review them, thus employing member checks (Lub, 2015).

Data analysis

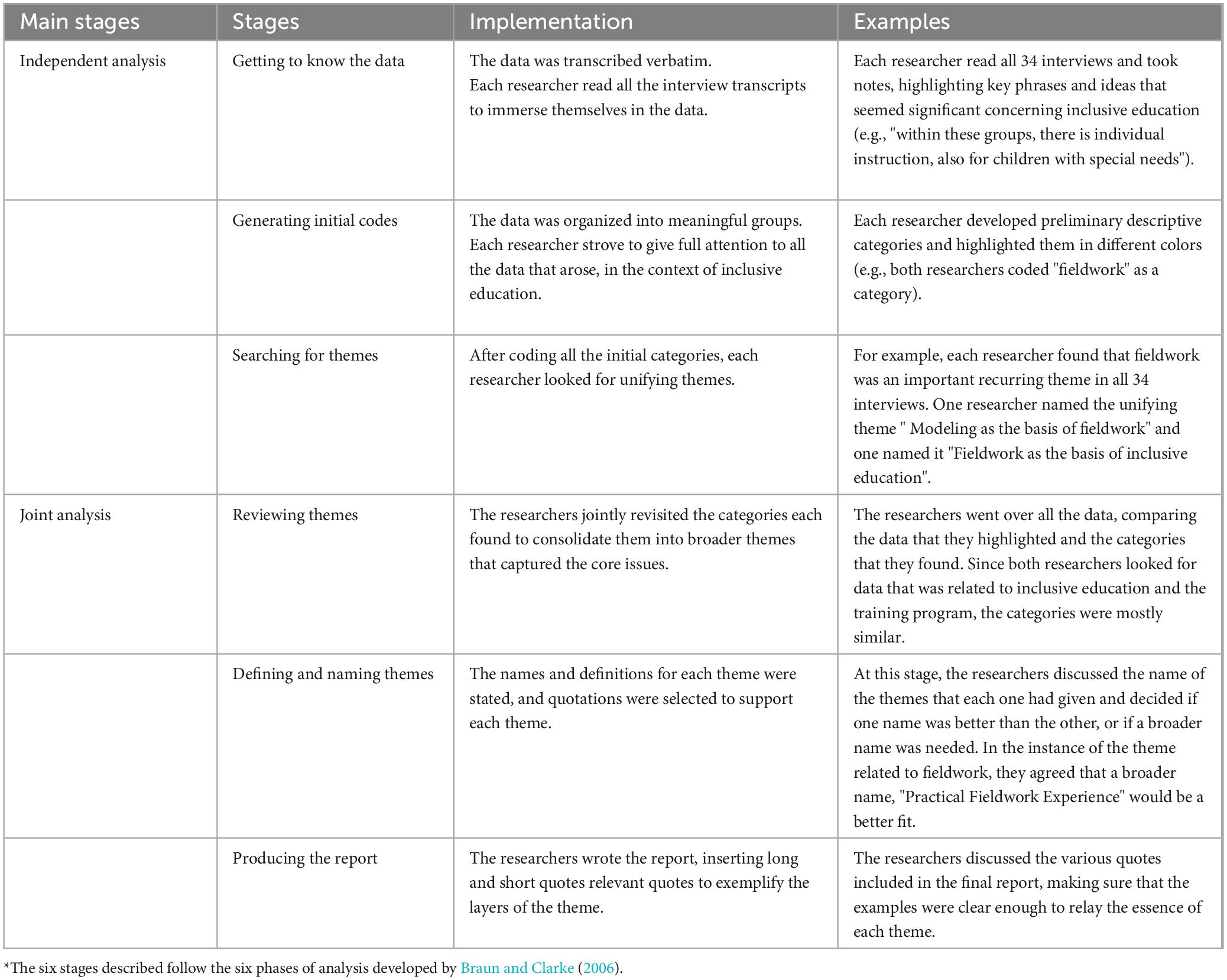

The data analysis followed an inductive approach, allowing categories and themes to emerge from the data itself rather than being predetermined by existing theoretical frameworks (Nowell et al., 2017). This approach aligns with the study’s exploratory nature and constructivist paradigm, enabling the researchers to remain open to unanticipated findings that surfaced in the participants’ responses. The analysis was conducted in two main stages, independent and collaborative, guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework (see Table 2).

In the first stage, each researcher independently read all 34 interview transcripts, immersed themselves in the data, and began identifying initial codes and descriptive categories related to inclusive education. Notes and color coding were used to organize relevant data segments. Themes were not imposed but constructed through an iterative dialogue with the data. In the second stage, the researchers jointly reviewed and refined the initial categories, consolidating them into broader thematic constructs that captured recurring patterns across participant groups. They revisited the data to verify coherence, clarified definitions, and resolved disagreements collaboratively. Representative quotations were selected to exemplify each theme, ensuring that the voices of participants were accurately reflected.

The use of constant comparison (Anderson, 2010) and careful thematic mapping (Shkedi, 2004) throughout the process enabled a multidimensional examination of participant perspectives, revealing both commonalities and contextual nuances in the teacher training process for inclusive education. To enhance the credibility of the analysis, triangulation across participant roles, peer debriefing sessions, and member checks were employed. These strategies supported the transparency of the inductive process and helped reduce individual researcher bias.

Results

The content analysis yielded four major themes related to advancing inclusive education in teacher education. The first major theme was practical fieldwork experience; the second was theoretical knowledge; the third was the connection between theoretical knowledge and practical tools; and the fourth was professional development and included two subthemes: knowledge teacher educators have regarding inclusive education and professional development programs within the colleges.

Practical fieldwork experience

One notable study finding points to practical fieldwork as essential in the optimal training of teacher candidates for teaching in heterogeneous classrooms. Several candidates stressed the importance of practicing diverse teaching, instructional, and system-related situations to understand schools, inclusivity, and the tools needed to achieve it. Danielle, one of the candidates, said, “It is important to try more practical things. During my training, I developed a meaningful relationship with the children in the class”. The same point of view was articulated by most of the program heads, as was explained for example, by Edna, who said that the first year of practical training is dedicated to individual instruction, while the second to “ways of working with small groups of pupils,” and the third, goes on to work with those that have special and diverse needs and abilities in a heterogeneous class. Like most pedagogical counselors, Yaron emphasized: “The third year is when the candidates utilize the characteristics of differential teaching in small groups while still teaching each pupil individually.” It is apparent that the two processes are essential in the optimal training for inclusive education. Yasmin, one of the teachers, stressed the importance of mutual processes:

At first, they learn how to make personal connections with the children. They work not only with the whole class but also with small groups of pupils; within these groups, there is individual instruction, also for children with special needs. And then, when they teach the whole classroom, the bond with the children already exists. This is fundamental to advancing their training in heterogeneous classes.

Principal Shahar and all the other principals stressed that the candidates should “understand the importance of personal relations with the pupils during their fieldwork.” In sum, all the participants stressed the importance of fieldwork as the basis for introducing processes of inclusion, both at a conceptual level and to acquire the tools and skills needed for teaching in heterogeneous classes.

Theoretical knowledge

The second theme that emerged focused on the theoretical knowledge necessary for the candidates’ training. The participants emphasized the need to incorporate inclusive education and diversity concepts throughout the training program. Most of the pedagogical counselors and all the program heads stressed the importance of courses regarding inclusive education. As Daphne, one of the heads of the programs, pointed out: “Every teacher candidate will have to take a course that will clarify concepts and learn about this thing called inclusiveness and diversity.” Efrat, another head of an elementary education program, said:

They have courses in the program – one that deals with learning disabilities and one that deals with inclusive education and integration. They also learn about diversity and lead a problem-based learning project (PBL), choosing a disability-related topic.

However, the need for knowledge in the field of special education, alongside the confusion concerning concepts of inclusive education, arose among the interviewees. It is evident that some of the training programs emphasize disabilities rather than inclusive education, as Hani, one of the program heads, explained: “They take special education courses but not inclusive education.” According to Ruthie, a pedagogical counselor, “You have to learn basic concepts, I think that within the training, I would add basic courses about learning disabilities, basic concepts in special education, and all sorts of similar things that they need to know.” Stav, a candidate, echoed this need. “I think there should be courses that teach more about pupils with special needs because now the teacher must deal with all the special needs of the pupils in the classroom. We need more knowledge.”

The candidates describe a lack of knowledge, as revealed by Galia’s remarks, “I do not have any courses about inclusion or mainstreaming.” In addition, Hani, head of one of the programs, raised the need to provide knowledge about collaborating with parents as an important component for promoting inclusive education in the classes.

In the second year, we work on various disabilities and add the whole issue of collaborating with parents and the community [.] The issue of discipline and connecting with parents is indispensable. In my opinion, these are the weakest links.

Hava, one of the pedagogical counselors, elaborated, “We have to add subjects, such as education in special classes, general matriculation track classes, and other types of classes. It is important to bring in these issues.”

In conclusion, there is a demand for addressing many additional theoretical topics. However, despite the agreement on the need to increase theoretical knowledge, all the participants spoke in terms of adding elements as “add-ons,” and the challenge of incorporating the relevant theoretical materials as an integral part of the training program remains.

Connecting between theoretical knowledge and practical tools

The third major theme that emerged was related to the connection between relevant theoretical knowledge and the practical tools necessary in the practical field experience, which was crucial for promoting optimal inclusive education. As Efrat, one of the program heads, explained, “Everything they learn in theory I want to see applied in the field, and that is why I monitor it and see how it is implemented.” Michal, a pedagogical counselor, elaborated. “I think that first of all, some kind of academic base should be taught in the academic courses regarding what they will meet in the field.” Hava, another counselor, described her methods. “Every week, I give a workshop at my candidates’ school, and we discuss the issues that they met in the classes that day or that week, and that is where we do the real work, connecting between theory and practice.” The counselors realize that the connection between theory and practice must be constantly maintained. Michal, a pedagogical counselor, added:

They must receive a combination of theoretical and practical knowledge together. We want to translate theory into practical moves. They need to learn how to plan a learning program and how to build a personal learning plan for the pupils.

The requirement to connect the theoretical knowledge to the field of practice was stressed by Galia, one of the teacher candidates:

We need more about what you need in real-life situations. We should bring experiences from the field because, otherwise, in real-time, we will not know what to do. Making field practice the priority in the training program is necessary.

The teachers stressed the importance of providing more theoretical and practical knowledge, such as “special education courses and learning strategies. Some strategies help more, and the material can be simplified.” This statement was reinforced by all the principals and teachers, such as the teacher Yasmin, who said unequivocally: “Differential teaching in classrooms is important. They must get the relevant tools to deal with the children according to their needs.” The benefit of combining theory and practice throughout the training program is evident, particularly in the context of inclusive education. Sharon, a pedagogical counselor, emphasized that “we teach them classroom tools after being taught the relevant knowledge and the expected attitudes toward inclusion. Hopefully, it will assist them. The combination of expected attitudes and appropriate tools is good.” In sum, all the interviewees from academia and all the teachers and principals stressed the importance of combining theoretical and practical knowledge, underscoring the importance of both.

Professional development

The professional development theme had two subthemes. The first was teacher educators’ knowledge regarding inclusive education, and the second was their professional development programs within the colleges. It is interesting to note that none of the teacher candidates referred to either of these subthemes.

The knowledge that teacher educators have regarding inclusive education

A lack of up-to-date knowledge regarding inclusive education, in general, was voiced, alongside concerns about the pedagogical counselors’ ability to convey the appropriate knowledge, as required in the training programs. Daphne, one of the program heads, described the issue. “We asked the counselors in the elementary school program about the basic concepts of inclusive education, and it was quite clear that they do not know many things related to special and inclusive education.” Limor, a pedagogical counselor, asserted that “when speaking about inclusiveness and integration, there are counselors who have been working for a long time and need to be updated, and there are counselors who are new and need orientation as to what it all means.” Hani, head of another program, also raised this concern:

Most of the counselors complained at the end of last year and asked how they were expected to train the candidates since they did not have sufficient knowledge. They raised many concerns stating that this is not part of the elementary school program.

The counselors voiced the same concerns regarding the gaps and lack of knowledge of special needs and what is needed for inclusive education. For example, Hagit said:

It is important to know the best practices for teaching these pupils because we know that teaching them is no longer the same as teaching the other children. This knowledge is missing, many counselors do not have it.

Awareness of the knowledge gaps that exist among teacher educators also arose, to a lesser extent, from the voices in the educational field. Yasmin, one of the teachers, stressed that the training does not fit the complexity of today’s heterogeneous classes. “I do not know if the counselors can supply the appropriate training. I see that the candidates are finding the solutions from us - the teachers.” Her words imply that the pedagogical counselors overseeing the training of future teachers lack the required knowledge regarding inclusive education.

Professional development programs within the colleges

The existing knowledge gaps require a training process for teacher educators. This process has already begun in Israel, with each institution training according to its priorities and resources, but without any clear national or general requirement or guidance. The intent to promote inclusive education in the counselor’s professional development arises clearly. However, it is evident that the process is just at the beginning, and much work is still needed to promote the learning and training of the educational teams. All the program heads and most pedagogical counselors and teachers stressed this need. Efrat, head of one of the programs, explained:

Two years ago, I began to examine the possibility of professional development for pedagogical counselors and started a structured training program for them in inclusiveness and integration. We formed a college team that included the head of the college’s special education program and the head of the internship program.

Sharon, a counselor, described that they met “every 3 weeks in a counselors’ forum and studied together. There is a constant need for professional development.” According to Daphne, one of the heads of the programs, relevant content must be enriched, alongside the strengthening of ties between content knowledge and practical training, so that the counselors will not have to make the connections “intuitively.” They are addressing the issues, but it should be more systematic. If we want the candidates to be trained and develop some feelings of efficacy, they do not make the link until we do.” Daphne described the initiative she took to advance the professional development in her program:

When it came to inclusiveness and integration, I focused on the difference between inclusiveness and integration. First, we clarified the concepts …, and then we took the materials published by the Ministry of Education about inclusive education. Each group had to choose an issue and prepare a didactics class that dealt with the issue.

Yaron, a frustrated counselor, asked: “How do you expect pedagogical counselors to train teacher candidates who have pupils with diverse needs in the classroom, especially as they are not from the special education field and do not have the relevant knowledge?” The voice of the pedagogical counselors was clear, seeking and conceptualizing the knowledge they needed and that which they lacked so that they could promote inclusive education in the training program. Hagit, one of the counselors, described the tools she needed, sounding like a checklist:

First, getting to know special populations integrated into general classes and at-risk populations. However, I think it must come not only theoretically but also on a practical level, like a seminar, meaning that the pedagogical counselors will bring case studies from the training field, even their cases with the candidates, things they experience firsthand.

The need for learning arises very clearly from the voices of the interviewees. Lifelong learning is a well-known concept in teacher training, endorsed in all educational institutions. However, no policy dictates the scope required to promote this learning, and many institutions do not have control or measures to enforce professional development, nor can they assess whether professional development and learning are being carried out. Merav, a principal, stressed that lifelong learning “should be for everyone in the field of education.” The desire for professionalism is heard in the words of Michal, the pedagogical counselor, who firmly said that “a teacher must continue to study all the time.” In the context of inclusiveness and inclusive education, there is a strong need for in-depth, meaningful learning.

Discussion

The current study examined existing, emerging, and absent elements concerning inclusive education implemented in general education teacher-training programs in teacher colleges in Israel. The content analysis of the data revealed four major themes, underscoring the elements that could promote optimal training for inclusive education. The first was practical fieldwork experience, the second was theoretical knowledge, the third was the connection between theoretical knowledge and practical tools, and the fourth was professional development. These themes are not surprising, as they reflect long-standing challenges in teacher preparation programs globally. In this case, these themes underscore what is relevant to inclusive education and the related shortcomings. The biggest hurdle is to encourage and support teacher training institutions and the Ministry of Education to formalize a true reform of the pre-service curricula to ensure the relevant pedagogy throughout pre-and in-service training nationally. Reform in teacher education programs necessitating inclusive education training is a MUST. Unfortunately, most countries are adding courses or fieldwork to existing teacher training programs or even lengthening the training programs, as in the case of Ireland (Hick et al., 2018; Hick et al., 2019) but not undertaking a complete reform and not replanning the training programs to train the teacher candidates to prepare them for inclusive education. To begin unpacking the themes, we first turn to the foundational importance of practical fieldwork experience in preparing teacher candidates to work effectively in heterogeneous classrooms.

Practical fieldwork experience

Recent studies (Hopkins et al., 2018; Walton and Rusznyak, 2020) indicate that candidate teachers are expected to know how to teach in a heterogeneous class, including pupils with diverse needs, thus enabling all pupils’ full emotional, social, and academic participation. One of the recommended ways to achieve this goal is to train candidates in schools that already employ successful models of inclusive education (Hick et al., 2019). Thus, they will be able to experience success personally (Lautenbach and Heyder, 2019) and develop their feelings of efficacy as teachers. It is important to emphasize that merely exposing the candidates to desirable models is not enough; active participation within a class that already implements best practices for inclusive education is required. Thus, the candidates will experience firsthand work with the pupils and a broader perspective of the heterogeneous class, as supplied by the training teacher (Kimhi and Bar Nir, 2024). As stressed by the interviewees, during the training process, each teacher candidate should learn how to develop a meaningful personal relationship with the pupils in the class. To promote the teacher candidates’ self-efficacy and to advance their positive feelings about inclusive education, they must know their pupils’ abilities, interests, and readiness to learn. Without this level of acquaintance, the chances of facilitating a feeling of competence regarding inclusive education are low (Walton and Rusznyak, 2020) or even non-existent. The current study confirmed the need for varied experiences in the practical field. These conclusions demand that when placing teacher candidates in schools for their practical fieldwork, the program heads and pedagogical counselors find schools and teachers that have already adapted their way of teaching and implemented inclusive education practices. This is complex since Israel’s educational system is still transitioning toward inclusive education, so finding these schools and teachers can be a huge hurdle. While practical experiences provide invaluable hands-on exposure, they must be grounded in a robust theoretical framework. Although participants emphasized the need for more theoretical content, they also highlighted the lack of meaningful integration between what is learned theoretically and what is practiced in the field. The following section delves into how these gaps might be bridged to enhance candidates’ ability to translate theoretical learning into effective inclusive teaching strategies.

Theoretical knowledge and connecting between theoretical knowledge and practical tools

Another theme that arose dealt with the theoretical knowledge required in the field of inclusive education alongside the need to connect it to the practical fieldwork experience. Our findings echo those in the professional literature (e.g., European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2020), indicating that programs focusing solely on theoretical components, such as single courses about special needs or inclusive education, are insufficient in preparing teacher candidates for the realities of diverse classrooms. Programs that combine coursework and fieldwork experiences bring forth the multifaceted reality of diversity. The current study’s findings accentuate what has already been found in previous studies regarding the importance of underscoring the connections between the theoretical components and the practical fieldwork training components, thus enhancing applicable translations of the theoretical knowledge acquired during the training (Sharma and Mullick, 2020) and establishing a comprehensive unit of information (Walton and Rusznyak, 2020).

Teacher training programs can better integrate theory and practice by embedding intensive mentoring programs throughout the training period. In such models, candidates are paired with experienced mentor teachers who implement inclusive practices and support the integration of course concepts into day-to-day classroom activities. Weekly reflective sessions and co-teaching opportunities can help candidates apply theoretical concepts such as differentiated instruction, collaborative learning, and behavior management directly within inclusive settings (Hopkins et al., 2018). Additionally, simulations and role-play scenarios can be used to prepare candidates for inclusive classrooms. These can create virtual teaching environments where preservice teachers can practice managing inclusive classrooms, differentiating instruction, and responding to behavioral challenges while feeling safe enough to make mistakes and learn from others (Qualls et al., 2024).

Furthermore, when planning the curriculum, it is essential to underscore the connections between theory and practice since the teacher candidates usually find it challenging to make the connections independently (Walton and Rusznyak, 2020). The European Agency for the Development of Knowledge in Special Education (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education [EADSNE], 2012) designates required areas of knowledge at both the theoretical and the practical level, such as knowledge about adapted teaching practices, assessment, comprehensive knowledge about disabilities, teamwork, teaching according to the Universal Design of Learning (UDL), alongside practical knowledge (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2022). Unfortunately, many of these issues were absent from the current study’s participants’ existing teacher education training programs. They were also not brought up by the interviewees, perhaps indicating how far even the most involved professionals are from best practices.

Still, the integration of technology and UDL is central to inclusive teaching. UDL provides a flexible instructional framework to meet diverse learners’ needs (Baldiris Navarro et al., 2016; Lowrey et al., 2017). Technologies that contribute to inclusive education are digital tools and devices that enable equitable access to learning (Navas-Bonilla et al., 2025). Teacher education programs should introduce teacher candidates to digital tools aligned with UDL principles, such as captioned videos and screen readers for the principle of multiple means of representation, digital and video submissions for the principle of multiple means of action and expression, and gamified learning and adaptive platforms for the principle of multiple means of engagement.

Strengthening the link between theory and practice also depends heavily on the competencies of the teacher educators and mentors who guide candidates through their training. This brings us to the final theme that deals with the professional development of those responsible for shaping the next generation of inclusive educators.

Professional development

There is a consensus that the expertise of teachers depends on constant professional development and life-long learning (Van der Klink et al., 2017). The importance of the professional development of teacher educators has become an increasingly prominent issue in general (Van der Klink et al., 2017) and regarding successful teacher training for inclusive education, in particular (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE], 2019a). It is imperative to support teacher educators so that inclusive education becomes understandable and feasible for them. This support should be manifested in high-quality professional development aimed at illuminating the paradigms of inclusive education. Promoting the global concept of inclusion will not be possible without the relevant knowledge. This need was also a key finding in the teacher training reform in Ireland and stressed the need for a systemic change regarding inclusive education worldwide. In Ireland, they stressed the importance that teacher educators have access to opportunities for professional development in inclusive education (Hick et al., 2019). In Israel, although the teacher training colleges that participated in this study had started implementing professional development programs for the teacher educators, albeit without any determined policy. Each college realized the need and operated on an individual and voluntary basis. The teacher educators, like the teachers in the educational system, lack a feeling of self-efficacy in relation to inclusive education. Furthermore, there is a mix-up regarding the meaning of inclusive education. Many interviewees regard it as accommodating children with special education needs and do not realize the broader context. This is one of the dangerous pitfalls when training for inclusive education. Therefore, it is not enough to determine which issues need to be adjusted in the curriculum of the teacher training programs. The reform must be widespread and deal with the retraining of the teacher educators themselves.

In sum, there is unanimous feedback that more preparation and training are required at all levels, as expressed in all the themes, and based on the interviewees’ personal experiences. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that the whole teaching chain, including the teacher educators, the pedagogical counselors, and the program heads in the teaching colleges, is in a similar situation. When addressing all the findings, the primary conclusion is that the whole is much more significant than its’ parts. The entire system needs to be reformed and articulated, not only its parts. The teacher candidates, counselors, faculty, and school personnel are all integral to the system and, therefore, underscore the need for an articulated reform of each arm of the system - practical fieldwork, theoretical knowledge, and professional development.

True reform necessitates replanning training programs in Israel to adapt to the new reality. There is an inherent conflict between a desire in Israel for a timely introduction of inclusive education on the one hand and the need for adequate prior preparation and training on the other. We conclude that a slower-paced transition would have allowed for better preparation and training and, most likely, for better ultimate execution of the transition. It is a fundamental requirement to lead a genuine reform that clear guidelines be established regarding the curriculum of teacher-training programs toward inclusive education training and the professional development of teacher educators. One cannot implement a law dealing with inclusive education successfully without laying the necessary foundations within the teacher training programs and for the professional development of teacher educators. The educational future lies with these programs; therefore, implementing appropriate and adequate training is not ancillary but indispensable.

Study limitations, conclusions, and recommendations

This study was conducted within a specific time frame and context, involving a relatively small sample of teacher colleges and schools, which may not fully represent the broader teacher training landscape in Israel (Wolcott, 1990). Therefore, the findings and emergent themes should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation lies in the exclusive use of semi-structured interviews as the primary data collection method. While interviews offer rich, in-depth insights into participants’ perceptions and experiences, they are subject to inherent biases, such as social desirability bias, where participants may present themselves or their institutions in a more favorable light, and recall bias, which may affect the accuracy of their reflections. Furthermore, the researchers’ affiliation with teacher education institutions may have introduced response bias, particularly among teacher candidates and pedagogical counselors, who may have felt constrained in expressing critical views. Although trustworthiness was strengthened through member checking, triangulation across participant roles, and peer debriefing, the absence of additional data sources—such as classroom observations, document analysis, or student performance data—may have limited the depth and robustness of the findings. To address these limitations, future research could benefit from employing mixed-methods approaches that combine qualitative insights with observational or quantitative data, thereby enhancing the reliability and generalizability of results. Nonetheless, due to the multidimensional scope of this study—spanning multiple participant roles across various institutions—some degree of generalization may still be appropriate and informative.

This study identified four interconnected components critical to effective inclusive teacher education. Together, these findings highlight that isolated reform—such as adding a single course or extending training length—is insufficient. Instead, systemic change is needed at all levels of teacher preparation. The key recommendations include redesigning teacher training curricula to embed inclusive pedagogy throughout, aligning field placements with inclusive environments, introducing mentoring and technological tools guided by UDL principles, and institutionalizing structured professional development for teacher educators. These recommendations are essential for aligning teacher education with inclusive education policy and ensuring that teacher candidates are equipped to meet the diverse needs of learners in today’s classrooms.

We recommend complementing the current findings with additional research. Since this study focused on elementary education teacher-training programs, one design recommended for future empirical studies would be expanding the study to the secondary and early childhood education training programs. The underlying assumption of that study should be that there is a difference between all life stages and that there may be unique characteristics for other ages that should be examined separately. Furthermore, since this is an urgent international issue, comparative studies with other countries undergoing reform in their teacher education programs for inclusive education would be recommended.

Since only approximately seventy countries report implementing inclusive education in teacher training (Global Education Monitoring Report [UNESCO], 2020), there is a critical need to advance teacher education reform internationally and learn from different countries’ attempts at reform. True reform mandates rethinking and restructuring the training programs. These findings have crucial implications for policymakers nationally and, by extension, internationally.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ABN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We thank the MOFET Institute for funding the research and the Levinsky-Wingate Academic College for funding the article publishing charges.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer DP declared a past co-authorship with the authors to the handling editor.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackah-Jnr, F. R., Abedi, E. A., Udah, H., and Ackah, M. J. (2025). Essentialising teachers’ education for inclusive education: The forms, characteristics, and synergies that support capacity building for sustainable inclusive practice. Support Learn. 40, 51–64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12516

Anderson, C. (2010). Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 74:141. doi: 10.5688/aj7408141

AuCoin, A., Porter, G. L., and Baker-Korotkov, K. (2020). New Brunswick’s journey to inclusive education. Prospects 49, 313–328. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09508-8

Baldiris Navarro, S., Zervas, P., Fabregat Gesa, R., and Sampson, D. G. (2016). Developing teachers’ competences for designing inclusive learning experiences. Educ. Technol. Soc. 19, 17–27.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Baş, G. (2021). Teacher beliefs about educational reforms: A metaphor analysis. Int. J. Educ. Reform 30, 21–38. doi: 10.1177/1056787920933352

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among five Approaches, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). “Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 1–32.

Desombre, C., Lamotte, M., and Jury, M. (2019). French teachers’ general attitude toward inclusion: The indirect effect of teacher efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 39, 38–50. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1472219

Dorner, D., Penn, R., Sobol, R., Shliemoff-Rechtman, S., Cassuto–Shefi, E., and Malka, Y. (2009). The Public Committee for the Examination of the Special Education System in Israel. Available online at: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Owl/Hebrew/Dorner.pdf

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education [EADSNE]. (2012). Teacher Education for Inclusion: Profile of Inclusive Teachers. Odense: EADSNE.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE] (2022). Profile for Inclusive Teacher Professional Learning: Including All Education Professionals in Teacher Professional Learning for Inclusion, eds A. De Vroey, A. Lecheval, and A. Watkins (Odense: EASNIE).

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE]. (2019a). Teacher Professional Learning for Inclusion: Literature Review, eds A. De Vroey, S. Symeonidou, and A. Watkins (Odense: EASNIE).

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE]. (2019b). Teacher Professional Learning for Inclusion: Policy Self-Review Tool, eds S. Symeonidou and A. De Vroey (Odense: EASNIE).

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE]. (2020). Teacher Professional Learning for Inclusion: Phase 1 Final Summary Report. eds A. De Vroey, S. Symeonidou, and A. Lecheval (Odense: EASNIE).

Florian, L., and Camedda, D. (2020). Enhancing teacher education for inclusion. European J. Teach. Educ. 43, 4–8. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1707579

Gagnon, J. C., Honkasilta, J., and Jahnukainen, M. (2023). “Teacher education in Finland: Progress on preparing teachers for the inclusion of students with learning and behavior difficulties,” in Teacher Education Around the World: Challenges and Opportunities, eds R. de Oliveira Brito and A. Anselmo Guilherme (Paris: UNESCO), 197–221.

Gilor, O., and Katz, M. (2017). Teaching inclusive classes: What preservice teachers in Israel think about their training. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 16, 293–303. doi: 10.1891/1945-8959.16.3.293

Global Education Monitoring Report [UNESCO] (2020). Policy Paper 43. Inclusive Teaching: Preparing All Teachers to Teach All Students. Paris: UNESCO.

Hick, P., Matziari, A., Mintz, J., Ó Murchú, F., Cahill, K., Hall, K., et al. (2019). Initial Teacher Education for Inclusion. Final Report to the National Council for Special Education. Research Report No.27. Paris: National Council for Special Education.

Hick, P., Solomon, Y., Mintz, J., Matziari, A., Ó Murchú, F., Hall, K., et al. (2018). Initial Teacher Education for Inclusion. Phase 1 and 2 Report. Research Report No.26. Paris: National Council for Special Education.

Hopkins, S. L., Round, P. N., and Barley, K. D. (2018). Preparing beginning teachers for inclusion: Designing and assessing supplementary fieldwork experiences. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 24, 915–930. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1495624

Ianes, D., Demo, H., and Dell’Anna, S. (2020). Inclusive education in Italy: Historical steps, positive developments, and challenges. Prospects 49, 249–263. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09509-7

Khamzina, K., Stanczak, A., Brasselet, C., Desombre, C., Legrain, C., Rossi, S., et al. (2024). Designing effective pre-service teacher training in inclusive education: A narrative review of the effects of duration and content delivery mode on teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36:13. doi: 10.1007/s10648-024-09851-8

Kimhi, Y., and Bar Nir, A. (2024). Balancing special education knowledge and expertise in teacher training programs. Teach. Educ. 35, 443–459. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2024.2327861

Knesset (1988). Special Education Law, clause 762. 1988 [Hebrew]. Available online at: https://main.knesset.gov.il/activity/legislation/laws/pages/LawBill.aspx?t=LawReshumot&lawitemid=174543

Knesset (2018). Special Education Law (amendment 11), clause 763. 2018 [Hebrew]. Available online at: https://main.knesset.gov.il/activity/legislation/laws/pages/LawBill.aspx?t=LawReshumot&lawitemid=2065822

Lautenbach, F., and Heyder, A. (2019). Changing attitudes to inclusion in preservice teacher education: A systematic review. Educ. Res. 61, 231–253. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2019.1596035

Lewis, I., Corcoran, S. L., Juma, S., Kaplan, I., Little, D., and Pinnock, H. (2019). Time to stop polishing the brass on the Titanic: Moving beyond ‘quick-and-dirty’ teacher education for inclusion, towards sustainable theories of change. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 23, 722–739. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1624847

Lindner, K.-T., Schwab, S., Emara, M., and Avramidis, E. (2023). Do teachers favor the inclusion of all students? A systematic review of primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 38, 766–787. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2172894

Liu, X., and Potmesil, M. (2025). A review of research on the development of inclusive education in children with special educational needs over the past 10 years: A visual analysis based on CiteSpace. Front. Educ. 9:1475876. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1475876

Lowrey, K. A., Hollingshead, A., Howery, K., and Bishop, J. B. (2017). More than one way: Stories of UDL and inclusive classrooms. Res. Pract. Pers. Severe Disabil. 42, 225–242. doi: 10.1177/1540796917711668

Lub, V. (2015). Validity in qualitative evaluation: Linking purposes, paradigms, and perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Methods 14. doi: 10.1177/1609406915621406

Margalit, M. (2000). Report of a Public Committee for the Implementation of the Special Education Law. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education (Hebrew).

Navas-Bonilla, C. D. R., Guerra-Arango, J. A., Oviedo-Guado, D. A., and Murillo-Noriega, D. E. (2025). Inclusive education through technology: A systematic review of types, tools and characteristics. Front. Educ. 10:1527851. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1527851

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

Qualls, L. W., Carlson, A., Scott, S. N., Cunningham, J. E. M., and Hirsch, S. E. (2024). Special education teachers’ preservice experiences with mixed-reality simulation: A systematic review. Teach. Educ. Special Educ. 47, 124–141. doi: 10.1177/08884064231226255

Sharma, U., Aiello, P., Pace, E. M., Round, P., and Subban, P. (2018). In-service teachers’ attitudes, concerns, efficacy and intentions to teach in inclusive classrooms: An international comparison of Australian and Italian teachers. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 33, 437–446. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1361139

Sharma, U., and Mullick, J. (2020). Bridging the Gaps Between Theory and Practice of Inclusive Teacher Education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Sharma, U., and Spencer, S. (2018). Personalised Learning and Support: Inclusive Classrooms for Students with Additional Needs. Melbourne: Education Services Australia.

Shkedi, A. (2004). Words That Try to Touch, Qualitative Research – Theory and Application. Moshav: Ramot.

Slee, R. (2018). Paper Commissioned for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report: Inclusion and Education. Paris: UNESCO

Takala, M., Sutela, K., Ojala, S., and Saarinen, M. (2023). Teaching practice in the training of special education teachers in Finland. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 38, 835–849. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2177945

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2019). Promoting Inclusive Teacher Education: Curriculum. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2020). Personalized Learning within Teacher Education: A Framework and Guidelines. The Interpearl Project Partners. Paris: UNESCO.

Van der Klink, M., Kools, Q., Avissar, G., White, S., and Sakata, T. (2017). Professional development of teacher educators: What do they do? Findings from an explorative international study. Professional Dev. Educ. 43, 163–178. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2015.1114506

Walton, E., and Rusznyak, L. (2020). Cumulative knowledge-building for inclusive education in initial teacher education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 18–37. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1686480

Appendix

Guiding Questions for Interviews

Tell me about yourself and what you do at the school/college.

What can you tell me about the relationship between the school and the college?

What do you think about inclusive education in general? What about inclusive education in the school?

What can you tell me about the student’s training for inclusive education? Is it enough? What training should they receive? What should be added?

Keywords: inclusive education, teacher training, education reform, qualitative research, pre-service, teacher education

Citation: Kimhi Y and Bar Nir A (2025) Teacher training in transition to inclusive education. Front. Educ. 10:1510314. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1510314

Received: 12 October 2024; Accepted: 02 May 2025;

Published: 21 May 2025.

Edited by:

Israel Kibirige, University of Limpopo, South AfricaReviewed by:

Lina Higueras-Rodríguez, University of Granada, SpainDavide Parmigiani, University of Genoa, Italy

Shunit Reiter, University of Haifa, Israel

Shirley Har-Zvi, Talpiot College of Education, Israel

Copyright © 2025 Kimhi and Bar Nir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yael Kimhi, eWFlbC5raW1oaUBsLXcuYWMuaWw=

Yael Kimhi

Yael Kimhi Aviva Bar Nir

Aviva Bar Nir