- 1 English Language Education, Sari Mulia University, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

- 2Education of Administration, State University of Malang, Malang, Indonesia

- 3Geography Education, Khairun University, Ternate, Indonesia

- 4Education of Administration, Universitas Persatuan Guru 1945 NTT, Kupang, Indonesia

- 5Educational Management, State University of Papua, Manokwari, Indonesia

Building on Anderson’s nationalism concept (2006), national culture is essential as it shapes social practices and institutions; however, its complexity arises from internal diversity. This research aims to clarify how Nusantara cultural values are integrated into pupils’ management and activities to revitalize national identity and promote social harmony in Indonesia’s multicultural context. Utilizing a cross-sectional design, data were collected through surveys from 265 participants, including school leaders, teachers, staff, and pupils across ten provinces. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed for data analysis, revealing significant relationships among the variables. The findings indicate that the integration of Nusantara cultural values positively influences social harmony and significantly impacts the revitalization of national identity. Furthermore, pupil management activities grounded in these cultural values enhance social harmony and positively affect national identity, with the latter significantly influencing social harmony. This demonstrates a complex interplay among these elements, where both cultural value integration and pupil management activities are pivotal, with national identity acting as a mediating factor. These results underscore the critical role of cultural values in shaping educational experiences and fostering unity amid globalization. The implications of this study suggest practical strategies for educators and policymakers to enhance cultural integration within schools, preserving Indonesia’s rich heritage while promoting inclusivity. Ultimately, this research contributes to the discourse on cultural education, offering a framework for future studies to strengthen national unity and intercultural understanding in diverse societies.

1 Introduction

Anderson (2006, p. 4) states that nation-ness, as well as nationalism, are cultural artifacts of a particular kind. This implies that nations and nationalism are created and shaped by cultural practices, historical events, and shared symbols rather than emerging naturally, meaning that national identity is not an inherent or biological reality but a constructed consciousness that can be shaped through institutions such as education, media, and state policies. In this context, schools, as formal institutions, play a pivotal role in this process by transmitting cultural values and shaping how students perceive their nation and social belonging. Schools contribute to the construction of an “imagined national identity” that aligns with both ethnic traditions and civic unity (Smith, 1991). Understanding national culture is essential, as it influences social practices and institutions, yet it remains a complex topic. National culture has been debated due to internal diversity and cross-border similarities (Minkov and Hofstede, 2012). Hofstede’s Value Survey Module (VSM) has helped measure cultural values, but it has been criticized for oversimplifying them at the individual level, highlighting the need for more nuanced tools to capture cultural complexity, for instance, in a national context (Bearden et al., 2006). This aligns with Steel and Taras (2010) emphasized the dynamic nature of culture, which evolves in response to micro and macro-level factors as a mix of individual and national characteristics. According to Woods P. (1990, p. 27), culture is social, shared, systemic, and cognitive. It encompasses values, beliefs, rules, codes of conduct, language, speech patterns, and understandings of acceptable behaviors. Likewise, in the organizational context, National cultural values refer to the collective set of values, beliefs, and norms that define society and shape its social practices and institutions, even in nations with considerable internal diversity or common languages and religions (Akaliyski et al., 2021; Minkov and Hofstede, 2012).

Recent studies propose that in the era of globalization, national cultures should evolve, expand, and modernize to contribute to both national and global development while also adapting to ongoing changes and advancements (Ergashev and Farxodjonova, 2020; Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2020; Huong, 2023). In this case, embracing openness, diversity, and respect is essential for fostering cultural exchange and growth, but national cultures must also maintain a balance between their traditions and global perspectives (Chen et al., 2019; Chiang, 2020; Huong, 2023). Besides, racism and discrimination in Indonesia are serious problems that show up in different ways, like unfair treatment, negative stereotypes, exclusion, and violence against minority groups (Karmila and Budimansyah, 2022). To help strengthen national identity and social harmony in a globalized world, some regions focus on teaching local and national cultural values through families, schools, and communities (Djumat and Hayun, 2021).

1.1 Background of Indonesia’s national archipelagic cultural values

As an archipelagic nation with over 17,000 islands, Indonesia is home to rich cultural diversity, featuring more than 300 ethnic groups and 700 local languages, each contributing unique traditions and philosophies (Indonesia Development Forum, 2018). This cultural wealth shapes various aspects of life, including formal education. It is reflected in vital national principles such as Pancasila and Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, which emphasize diversity, cooperation, tolerance, and mutual respect. The Nusantara culture, another term of National Culture, represents the aspirations and dignity of the Indonesian people, rooted in a legacy of tolerance and collaboration. However, concerns are rising that the discourse around Nusantara culture is fading due to foreign influences, leading to a crisis in character and identity among youth. To counter these negative impacts, it is essential to continue promoting cultural discussions and the Nusantara’s values that unify the nation.

1.2 Integrating Nusantara archipelagic cultural values into the education system

National cultural values are fundamental in shaping educational practices, management, and outcomes, influencing the content and effectiveness of education systems worldwide (Anderson, 2006). Education must incorporate universal shared values alongside specific ethnic and cultural values to promote social harmony within multicultural societies (Singh, 1995; Smith, 1991). Pupils’ attitudes toward education, shaped by their sociocultural backgrounds and national cultural values, significantly impact their learning orientation and how they interpret educational content and methods (Planel, 1997). Consequently, preserving cultural heritage and fostering well-rounded citizens are vital goals for national education (Nguyen, 2021; Thomas, 2009). Value-based education, beginning at home and extending into formal institutions, is crucial for students’ cultural development and aligns with interdisciplinary approaches to education policy, ultimately improving children’s character, fostering social harmony, and enhancing community resilience (Noviana et al., 2023; Prahaladaiah, 2021; Sakti et al., 2024; Suri and Chandra, 2021). This underscores the importance of integrating Nusantara cultural values within formal education systems.

1.3 The urgency of pupil management and its activities based on Nusantara archipelagic cultural values

National culture influences the management of transnational education programs in both academic and operational aspects, making it essential for adequate national and international education settings (Eldridge and Cranston, 2009). Pupils’ attitudes toward education are strongly shaped by their sociocultural backgrounds, which influence how they view essential aspects like authority, control over learning, and educational goals (Osborn, 2001; Planel, 1997). Managing cultural diversity in schools, especially inside the classroom, effectively requires inclusive leadership that fosters collaboration, values pupils’ cultural contributions, and is dedicated to social justice (Gómez-hurtado et al., 2021). In this term, teachers and leaders play a critical role by serving as role models, guiding and managing pupils through discussions and projects that reflect cultural traditions, ethics, and social norms in their activities.

The urgency of integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management and its activities in schools becomes even more critical as Indonesian youth navigate challenges posed by globalization, including the pervasive influence of global popular culture such as digital fandoms (Sugihartati, 2020), marginalization of religious minorities (Nilan and Wibawanto, 2023), and the cultural impact of the Korean Wave (Lee et al., 2020), which threatens the preservation of national identity and social harmony at school. However, limited research investigates the integration of Nusantara’s cultural values in the context of pupil management and its activities in the school environment to tackle these challenges. Consequently, building on Anderson’s (2006) concept of imagined communities and the existing presented literatures, this study posits that Nusantara archipelagic cultural values, when embedded in pupil management, contribute to national identity revitalization, which in turn fosters social harmony. Schools serve as key institutions in shaping collective identity by reinforcing cultural narratives and structured interactions that strengthen national belonging. As national identity is a socially constructed and evolving artifact, its revitalization through education ensures that cultural heritage is preserved while promoting inclusivity and cohesion in diverse school communities.

Henceforth, this study aims to examine the nexus of Nusantara archipelagic cultural values in pupil management and its activities on social harmony mediated by National Identity Revitalization. This study holds significance theoretically, practically, and for future research. Theoretically, it enriches the discourse on cultural integration in education by exploring how Nusantara cultural values can promote national identity and social harmony in the face of globalization. Practically, it provides educators and policymakers with strategies to integrate these values into pupil management and its activities, enhancing pupils’ sense of identity and fostering social harmony. Lastly, future research opens new avenues for examining the long-term impact of cultural integration in education systems, especially in multicultural societies, and its influence on national unity and intercultural understanding.

2 Literature review

2.1 The concept of Nusantara cultural values

The concept of Nusantara archipelagic insight plays a crucial role in resolving cultural conflicts and the negative globalization influence in Indonesia by promoting the understanding and integration of the nation’s diverse ethnic, racial, religious, and cultural backgrounds to strengthen unity and address potential tensions (Mukri and Waspiah, 2023). Indonesia’s rich cultural diversity, including historical and cultural values and archeological assets, is a valuable resource for national heritage, which requires sustainable management to preserve these benefits for the long term (Ardiwidjaja and Antariksa, 2022). Teaching Indonesia’s history and culture in Social Studies is essential for helping pupils appreciate cultural diversity and understand the need for sustainable implementation (Nur et al., 2023). Integrating Nusantara cultural values into Indonesian education combines local wisdom and multicultural influences from a blend of indigenous and foreign influences (Indian, Arab, Dutch, Chinese, etc.) (Meliono, 2011), and religious insights that emphasize values such as obedience, independence, simplicity, togetherness, the spirit of gotong royong (cooperation), compassion, equality, deliberation, moderation, and tolerance (Yumnah, 2021) to build the worldview and values of the Indonesian people, promoting nationalism, harmony, and moral values in young people through education.

In the globalized era, national culture is vital to be implemented e.g., the study of Ergashev and Farxodjonova (2020) discovered that the essence of national culture not only upholds human freedom in valuing cultural respect but also fosters an understanding and appreciation of national culture and its unique characteristics. These findings emphasized the primary key to cultural diversity in a nation. Likewise, Nusantara cultural values should be woven into various subjects to ensure pupils acquire academic knowledge and develop an appreciation for their cultural heritage. This integration supports the recognition of ethnocultural identities while promoting national unity and equality (Blum, 2014; Perveen, 2014). In a diverse country like Indonesia, incorporating national cultural values into education requires a balance between fostering a unified national identity and respecting cultural diversity. Several studies highlight strategies to achieve this, including embedding regional cultural values into the curriculum (e.g., He et al., 2023; Legbo, 2022; Xia, 2023), fostering a culture of innovation (Fuad et al., 2022), civic education (e.g., Rapanta et al., 2021; Yang, 2024), cultural activities (e.g., Chen and Ma, 2023; Smagorinsky, 2022), inclusive education (e.g., Uthus and Qvortrup, 2024), moral and ethical development (e.g., Chan et al., 2024; Nurasiah et al., 2022), and integrating traditional arts and ideological education (e.g., Lin and Zhu, 2022; Setyawan and Dopo, 2020). However, most of these studies used a qualitative approach, and limited research uses a quantitative approach and cross-sectional study, particularly in exploring the nexus of integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management and its activities comprehensively to revitalize national identity and promote social harmony.

2.2 Social harmony at schools

Social harmony is the peaceful coexistence of individuals and groups, marked by mutual respect, understanding, and cooperation across diverse backgrounds (Smith, 1991). Schools are key to building social harmony, serving as places where pupils learn both academics and how to interact with peers from different backgrounds. Schools play a crucial role in fostering societal harmony by teaching respect and cooperation (Thayer, 1960). Similarly, Hanish et al. (2016) define social harmony in schools as a condition characterized by fostering positive peer interactions and cultivating an inclusive, supportive environment that allows students to connect across diverse backgrounds. Furthermore, social harmony in schools is conceptualized as a multilevel, overarching construct encompassing children’s relational competencies, peer relationship experiences, and the level of school support for fostering relationships (Hanish et al., 2016). The impact of promoting social harmony in schools includes the promotion of tolerance and respect, which helps pupils value and appreciate cultural, religious, and social differences (Astutik, 2023; Ginting et al., 2023); reduction of prejudice and discrimination through inter-group interactions and collaborative activities, and helping pupils overcome biased attitudes (Hughes, 2014); developing critical social and emotional skills like empathy, conflict resolution, and communication (Garibaldi and Josias, 2015), ultimately creating a supportive learning environment that reduces stress and anxiety among pupils, helping them focus better on their studies. In the context of Nusantara cultural values, Setiawan and Stevanus (2023) found that integrating these values in education promotes pluralism and social ethics in Islam Nusantara, helping resolve conflicts and encourage tolerance in multicultural societies. Additionally, Pratama et al. (2023) noted that Taruna Nusantara High School teachers create an inclusive environment with a multiculturalism approach that enhances pupils’ social resilience and prepares them for global challenges. These studies emphasized that integrating Nusantara cultural values in education fosters social harmony by promoting pluralism, tolerance, and resilience, preparing pupils to thrive in diverse and globalized communities.

2.3 The integration of Nusantara cultural values into pupil management and its activities

Pupil management refers to the strategies and practices teachers and administrators use to maintain discipline, foster positive behavior, create an environment conducive to learning, and support pupils’ academic and social development (McNamara, 2000). While traditional methods focus on discipline, authority, and behavior control, as explained by Chaplain (2016), modern approaches highlight inclusive leadership for diversity (Gómez-hurtado et al., 2021), community-building (Soodak, 2003), student-centered approaches (Li et al., 2022), and structured classroom management (Polirstok, 2015) are more effective. These strategies help teachers and educators meet students’ needs better and create a positive learning environment. Cultural values, like Nusantara’s emphasis on community, resilience, and adaptability, strongly shape pupil management in educational settings. Indonesian Nusantara values shape pupil management by integrating these values into the curriculum, fostering strong school leadership, and promoting nation-building, which helps students achieve academically while developing national identity and social harmony (Gaol, 2023; Moser, 2016). Power et al. (2024) discovered that culturally responsive teaching and pedagogy management can enhance pupils’ behavior by aligning education with their cultural backgrounds, making learning more relevant and engaging. Additionally, Mejía-Rodríguez and Kyriakides (2023) argue that national culture dimensions such as Monumentalism-Flexibility significantly affect student achievement. Imron (2010) noted several important Nusantara cultural values to integrate into pupil management, including truth, honor, unity, concern, self-esteem, harmony, patience, trustworthiness, heroism, social solidarity, respect for elders, adherence to wise advice, and piety.

These studies suggest that cultural factors can affect pupils’ behavior and enhance academic performance. However, challenges remain in integrating national cultural values into pupils’ management, including systemic barriers, policies, classroom practice difficulties, and the need for a collaborative and inclusive school culture (Sarmini et al., 2023). Therefore, we aim to examine how integrating national cultural values in pupil management and its activities can address the existing challenges in the Indonesian context, as this is significant for aligning educational practices with these values in revitalizing national identity and social harmony, ultimately enhancing overall student outcomes.

2.4 National identity revitalization as mediator

National identity is defined as a dynamic condition shaped by factors such as ethnicity, culture, language, religion, and ideology, which provide a crucial sense of belonging and recognition for a nation on the global stage (Anderson, 2006; Smith, 1991). In Indonesia, national identity includes ethnic and civic aspects, reflecting the country’s rich cultural diversity and varied social aspects (Agus et al., 2021; Fossati, 2021). Revitalizing national identity is crucial for countering globalization’s negative impacts by boosting national pride and unity and promoting cultural values like those in traditions and arts, emphasizing peace and harmony (Dharsono, 2017). Several indicators to conceptualize the revitalization of national identity, including cultural heritage integration (Ariely, 2012; Kunovich, 2009), community engagement (Agus et al., 2021), and national consciousness (Rusciano, 2003). Moreover, the moral teachings of Pancasila, Indonesia’s foundational philosophy, can help mitigate the harmful effects of modernization and globalization by promoting ethical values and social harmony (Madrohim et al., 2021; Mulyono, 2017; Shabrov et al., 2021). Education is essential for shaping and revitalizing national identity, especially in today’s globalized and tech-driven world, with schools acting as critical places for fostering this identity through curriculum, cultural activities, values-based learning, and school culture and extracurricular activities.

The curriculum is crucial for building and passing on national identity, with schools playing a key role in nation-building through the involvement of political leaders, educators, and students in creating education policies that promote national belonging (Jacob and Gardelle, 2020). Cultural activities, particularly sports, and arts in education, significantly reinforce national identity among pupils (Hadj et al., 2022; Setyawan and Dopo, 2020). Furthermore, values-based education is vital for developing national identity from a young age, with principals and teachers needing to incorporate these values into lessons and activities, yet the absence of clear policies emphasizes the need for defined strategies and models for this integration (Sarmini et al., 2023). Finally, fostering a school culture that highlights national identity requires an environment where students engage in activities promoting patriotism, tolerance, and social responsibility, with extracurricular activities like national events and community service playing a key role in internalizing these values (Mavroudi and Holt, 2015; Sarmini et al., 2023). These studies reflect that Indonesia’s national archipelagic (Nusantara) cultural values play a pivotal role in revitalizing national identity, forming the basis for educational practices that integrate curriculum design, cultural activities, values-based learning, and school culture, which promoting key Nusantara principles like unity in diversity, local wisdom, and social harmony, all of which cultivate patriotism, tolerance, and social responsibility among pupils.

Therefore, integrating Nusantara cultural values into educational activities, governance, and policy-making focusing on national identity can promote social harmony. For instance, programs in pupil management and activities that celebrate national heroes from diverse ethnic backgrounds or encourage the observance of local and national values help reinforce the connection between cultural diversity and national unity. This mediating role of national identity revitalization is evident in Indonesia’s approach to Pancasila education, where the core principles of the state ideology reflect the country’s rich cultural diversity and a unifying national doctrine. Revitalizing these civic values strengthens national identity, ensuring cultural diversity contributes to broader social cohesion and harmony.

2.5 The Nexus among measured variables based on previous studies and hypotheses development

The established hypotheses, mainly guided by Anderson (2006) concept. Several studies have also investigated integrating Nusantara cultural values through various aspects of the school education system. Previous studies demonstrate a substantial nexus between cultural values, pupils’ management, and pupils’ activities on social harmony, with national identity revitalization playing a crucial role. Integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management practices improves student behavior and academic performance, reflecting the strength of national identity and promoting social cohesion in diverse societies like Indonesia. This is aligned with previous studies, such as Gaol (2023), Gómez-hurtado et al. (2021), Moser (2016), Power et al. (2024), and Sarmini et al. (2023) who discovered the essential relationship of cultural values in school management, including pupil management at schools and classrooms, in unifying pupils from different backgrounds into one national identity, which develops a harmonious environment. Furthermore, student activities such as sports and arts, extracurricular activities like national events and community service based on Nusantara cultural values also revitalize national identity, which ultimately can promote social harmony at schools, as emphasized by Hadj et al. (2022), Jacob and Gardelle (2020), Mavroudi and Holt (2015), Sarmini et al. (2023), and Setyawan and Dopo (2020).

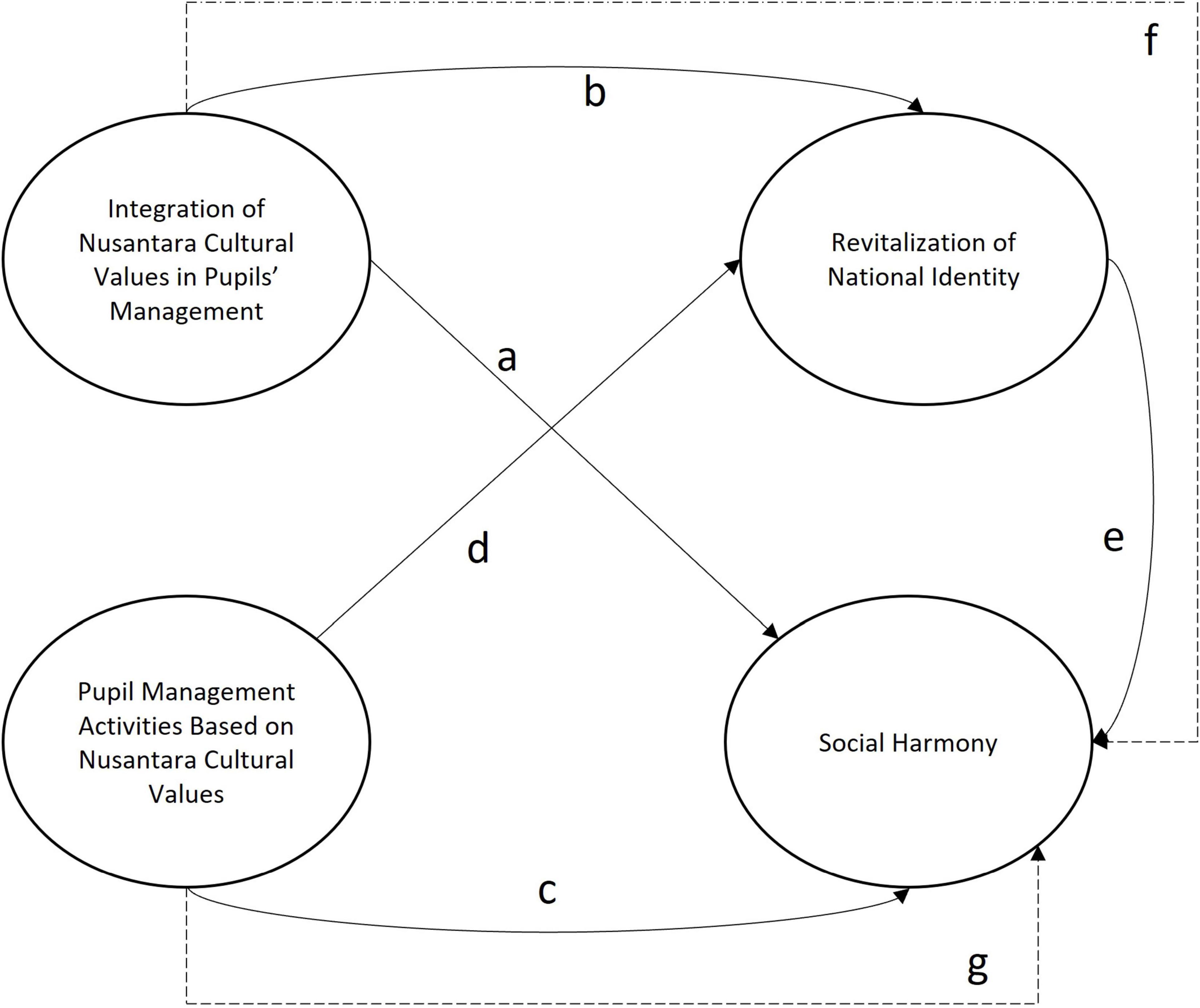

Revitalizing national identity, shaped by Nusantara cultural values into pupils’ management and activities as parts of education system settings, ensures that education contributes to broader societal goals, fostering tolerance, unity, and social harmony (Imron, 2010; Mavroudi and Holt, 2015; Sarmini et al., 2023). These findings highlight the importance of culturally responsive education in preparing students for academic success and active participation in a multicultural society marked by a solid national identity to create social harmony (Hughes, 2014; Pratama et al., 2023; Setiawan and Stevanus, 2023). Hence, the mediating role of national identity revitalization in pupils’ management and activities based on Nusantara cultural values would be a bridge to enhance social harmony at schools consisting of students from various backgrounds of cultures, traditions, religions, and habits. Finally, this study proposes seven key hypotheses, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesis model. Author(s) conceptual and hypotheses development. Figure 1 demonstrates the seven hypotheses proposed: (a) H1: Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in Pupils’ Management (X1) influences Social Harmony (Y); (b) H2: Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in Pupils’ Management significantly impacts the Revitalization of National Identity (Z); (c) H3: Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2) affect Social Harmony (Y); (d) H4: Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values Influences Revitalization of National Identity; (e) H5: Revitalization of National Identity (Z) significantly affects Social Harmony (Y); (f) H6: Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in Pupils’ Management influences Social Harmony mediated by Revitalization of National Identity; and (g) H7: Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values influence Social Harmony mediated by Revitalization of National Identity.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Design and procedures

This study employed a quantitative approach which serves as hypothesis testing research designed to clarify and explain the influence between specific variables. Data collection encompasses a broad demographic, including school principals, vice principals, teachers, students, and staff across diverse provinces in Indonesia. Data was collected once using Google Forms and distributed to schools across various provinces in Indonesia, following approvals from local government authorities and the schools. Additionally, this research adopts a cross-sectional design, with respondent surveys conducted between July and August 2024. The study’s primary aim is to examine how integrating Nusantara cultural values within pupil management and activities impacts social harmony, focusing on the role of national identity revitalization as a mediating factor.

3.2 Participants and sampling

We divided the participants into two groups: the pilot study participants and the research participants. The determination of participants was conducted by using voluntary non-probability sampling. The participants were volunteers with a strong interest in this topic (Murairwa, 2015). The pilot study participants (n = 53) included principals (n = 9%), vice principals (n = 10 = 19%), teachers (n = 21, 40%), staff (n = 2 = 2%), and students (n = 15 = 28%). These participants were from various types of schools, including public schools, vocational schools, and Islamic and Christian senior high schools, across three provinces in Indonesia: East Kalimantan (n = 23, 43%), South Kalimantan (n = 19 = 36%), and West Nusa Tenggara (n = 11 = 21%).

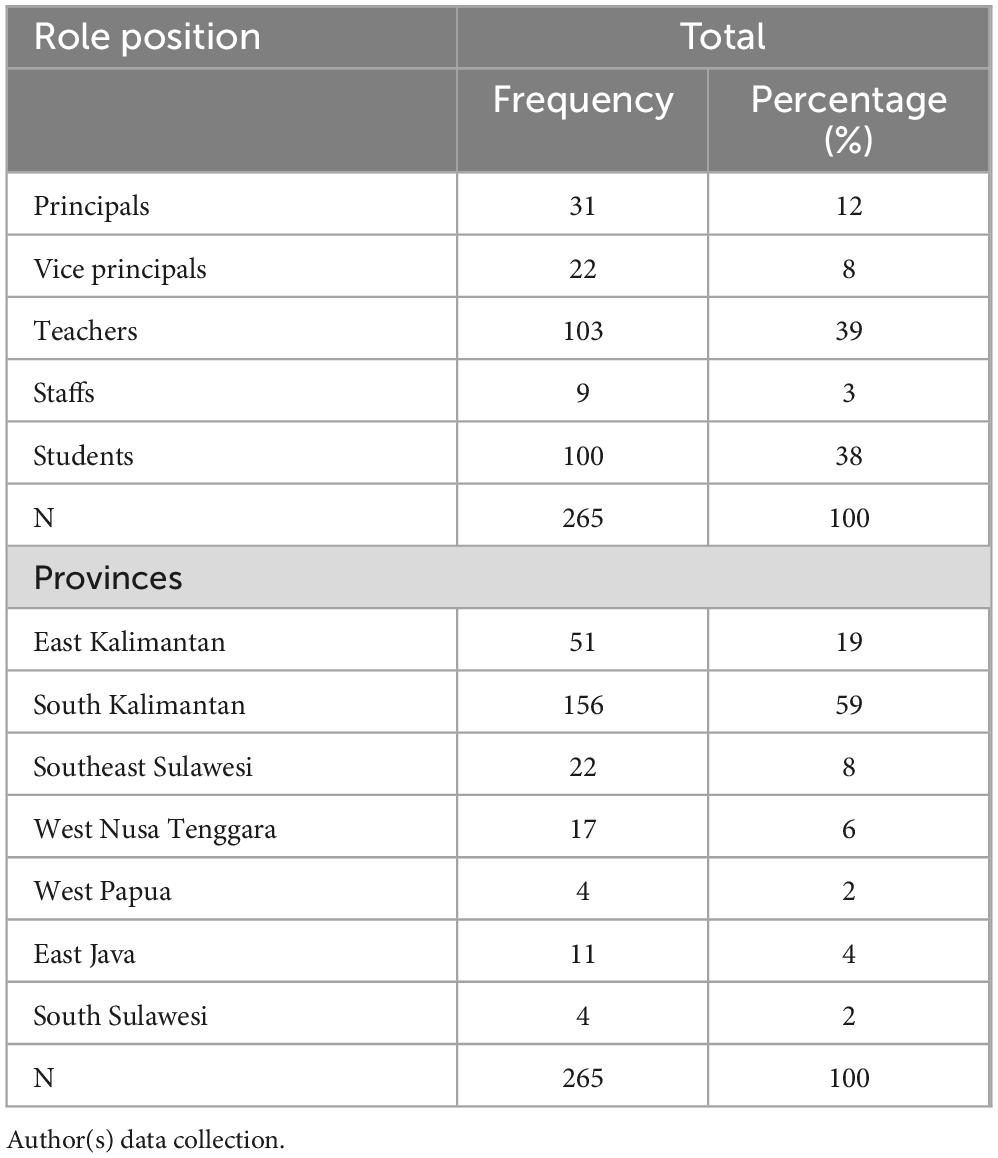

The research participants (n = 268) came from various types of schools, including public high schools, vocational schools, and Islamic and Christian senior high schools in 10 provinces, which were selected without specific to regional limitations to capture Indonesia’s diverse cultural contexts, particularly on how Nusantara archipelagic cultural values are integrated into pupil management practices and activities, which will enhance the study’s relevance by reflecting varied interpretations and implementations of cultural values, which differ not only by school type but also by regional context. However, provinces from Kalimantan were mandatory in this research due to its role as the new capital city of Indonesia in specific expected roles. Data collection relied on respondents who completed the survey within a specified set timeframe. The highest number of respondents came from South and East Kalimantan, comprising 59 and 19% (n = 156 and 51) of the sample, reflecting a significant representation of this region. In contrast, the lowest numbers were recorded in Papua, Bengkulu, and East Nusa Tenggara, each contributing only a single respondent (n = 1), or less than 1% of the total sample. Respondent positions are principals, vice principals, teachers, staff, and students. The highest respondent position came from teachers (n = 39%), students (n = 38%), and principals (12%) as shown in Table 1. There were 3 out of 268 respondents excluded from further analysis, including East Nusa Tenggara, Papua, and Bengkulu, because they represent too few respondents, which we afraid does not represent the population in these schools or provinces. Hence, the total number of participants for further analysis was (n = 265).

As shown in Table 1, we prioritized respondents from Kalimantan, Indonesia’s new capital, due to its strategic role as an expanding multicultural center in the present and future. With a significant influx of diverse populations anticipated, understanding current educational perspectives is essential to promote social harmony and effectively incorporate Nusantara cultural values.

3.3 Instruments

The research instrument underwent two phases: a pretest and a pilot study. We developed this instrument based on theoretical frameworks and previous research related to the topic addressed in this study (Supplementary Table 5). The instrument items utilize a five-point answer scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 5 represents “strongly agree.” Based on the literature review, we created more specific indicators for each item in the instrument and then reorganized the questionnaire items to reflect experiences and opinions. The total number of tested items (n = 56) included four measured variables with indicators: Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values of the Archipelago in Pupils’ Management (X1), Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values of the Archipelago (X2), Revitalization of National Identity (Z) as a mediator, and Social Harmony (Y). The indicators for the X1 variable comprised Faith and Truth (n = 2), Respect and Care (n = 4), Unity and Discipline (n = 3), and Trust and Independence (n = 6). The X2 variable included Community-Building (n = 5), Pupils-Centered Approaches (n = 3), and Structured Classroom Management (n = 2). Additionally, the mediator variable (Z) consisted of Cultural Heritage Integration (n = 6), Community Engagement (n = 4), and National Consciousness (n = 5). Lastly, the dependent variable (Y) was defined by indicators of Pupils’ relational competencies (n = 6), Pupils’ peer relationship experiences (n = 5), and Schools’ support for relationships (n = 6).

During the pilot study phase, the instrument items developed from the literature review were tested with 53 participants. The validity and reliability of the instrument items were assessed using SPSS v.25 confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, with a standard guideline suggesting that the alpha coefficient should generally be 0.70 or higher (Cronbach, 1951; Taber, 2018). The validity test results indicated that all items were valid (p < 0.05). The highest loading factor coefficient for validity was 0.898 for the Community-Building indicator of X2. The reliability test results for the four measured variables indicated significant coefficients: X1 (0.933), X2 (0.949), Z (0.962), and Y (0.963), demonstrating the consistency of the instruments required for further analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the constructs X2, Y, and Z have strong factor loadings, adequate commonality, high KMO values, and good reliability, making them robust for further analysis. X1 indicators are slightly weaker in factor loading but perform well in other areas.

3.4 Data analysis

In the data analysis for this study, we utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), as recommended by prior research (Hair et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2021). This method effectively examined complex multivariate relationships (Shah et al., 2022) and was implemented using SmartPLS version 4 (Hair et al., 2020; Sarstedt and Cheah, 2019). PLS-SEM was chosen for its ability to handle multiple latent variables, test relationships based on established theories and literature, and provide detailed insights into model support (Hair et al., 2021). Before analyzing the structural models, we first assessed the measurement model for internal consistency, which included Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and Rho_A (Cronbach, 1951; Hair et al., 2021; Taber, 2018); convergent validity, comprising outer loading and average variance extracted (AVE) (Hair et al., 2021); and discriminant validity, as indicated by the coefficient of Fornell-Larcker Criterion (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Once each coefficient met the required thresholds, we analyzed the structural models using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples to determine path coefficients and their significance (p < 0.05, two-tailed), as it provides robust standard error estimation, enhances statistical power, and does not rely on normality assumptions (Hair et al., 2021; Henseler et al., 2009). This approach ensures more precise confidence intervals for hypothesis testing and is widely recommended in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) research for its reliability and replicability (Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Sarstedt and Cheah, 2019). In this phase, we also assessed model fit using various criteria in SmartPLS 4, including Standardized Root Mean Residual and Non-Fit Index values, which must meet certain thresholds: SRMR ≤ 0.10, d_ULS ≥ 0.05, d_G ≥ 0.05, chi-square ≤ 3.00 (or preferably small), and NFI ≥ 0.80 (Edeh et al., 2023; Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013). Furthermore, this study draws on the definitions of mediation and non-mediation proposed by Zhao et al. (2010). For the mediation analysis, we employed bootstrapping, recognized as a robust and effective method for testing mediation effects (Hayes, 2009; Zhao et al., 2010).

4 Results

4.1 Assessment of measurement model

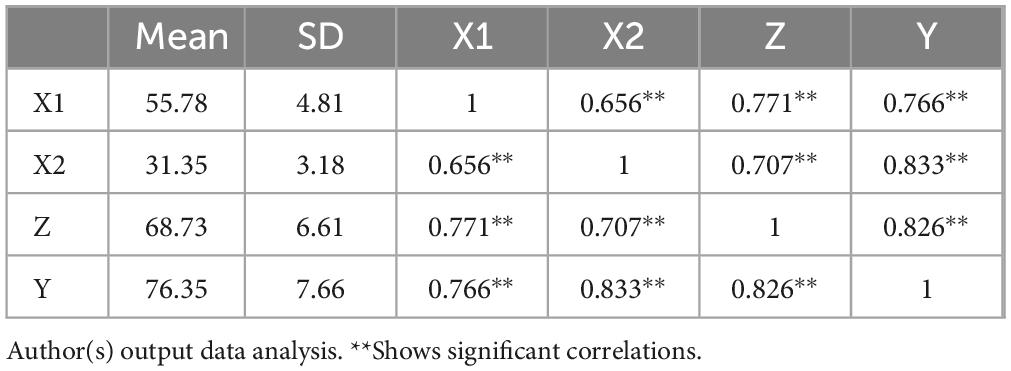

Before testing the hypothesis, the validity and reliability measurements are evaluated based on the measurement model (Supplementary Table 5). Following the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) testing of instruments, descriptive statistics—including means and standard deviations—and correlations were examined using SPSS v.25. The results reveal significant positive correlations among the constructs (Table 2). The integration of Nusantara cultural values into pupil management (X1), the integration of these values in student management activities (X2), the revitalization of national identity (Z), and social harmony (Y). Notably, X1 has the highest mean score (55.78), reflecting a positive perception of cultural value integration in pupil management, whereas X2 has the lowest mean (31.35). Strong correlations were identified between X2 and Y (r = 0.833, p < 0.001) and between Z and Y (r = 0.826, p < 0.001), indicating that improvements in the integration of cultural values in student activities and the revitalization of national identity can significantly foster social harmony. All correlations are statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.000. These findings also support the main hypothesis, suggesting that enhancing the integration of Nusantara cultural values in pupil management (X1) may lead to increased social harmony (Y).

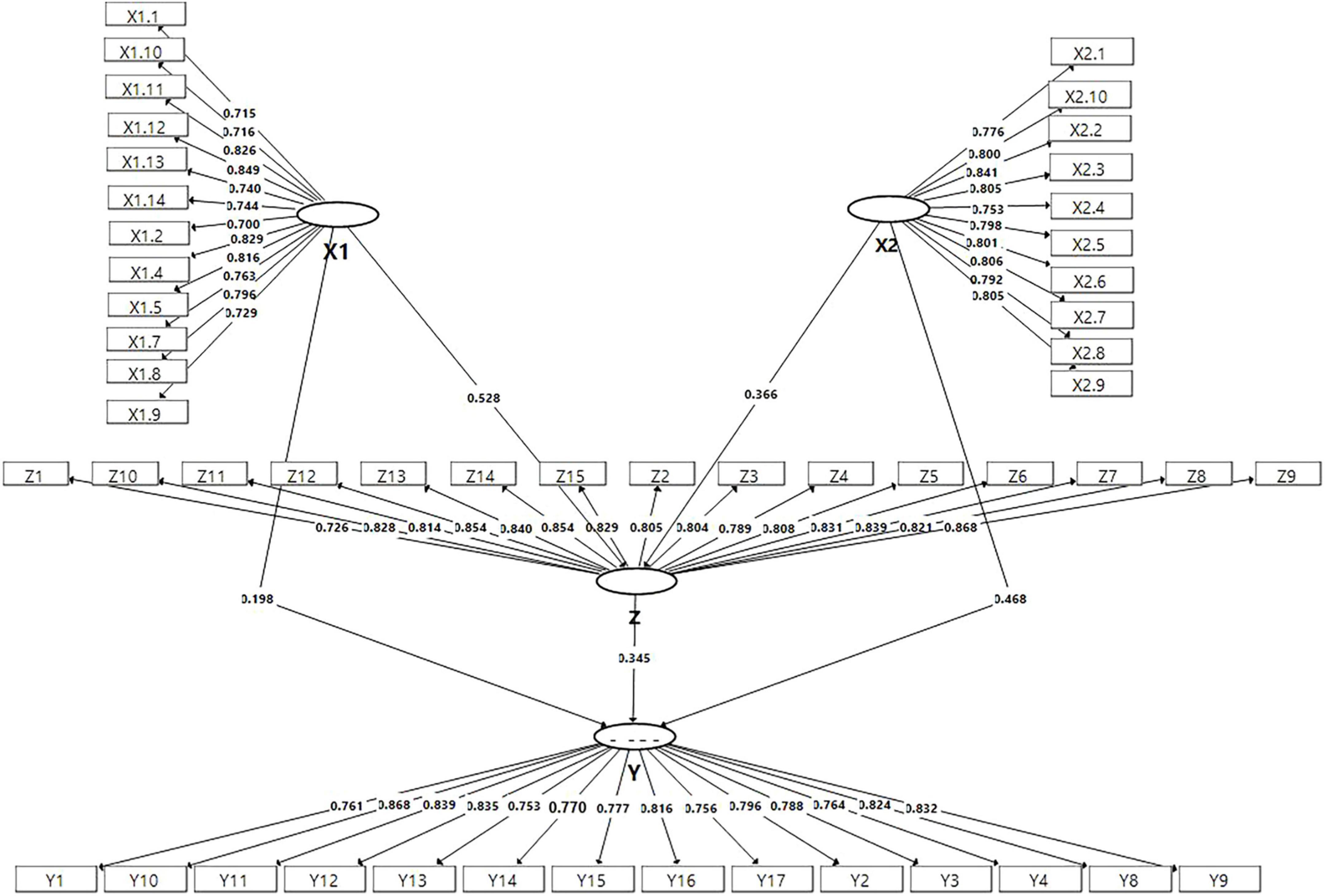

Furthermore, Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 6 show that all outer loadings, convergent validity, and internal consistency exceed the threshold after removing five of the 56 items. Additionally, the inner VIF values of each construct were also analyzed (Supplementary Table 3). The integration of Nusantara cultural values in pupil management (X1) shows strong item loadings (β-values from 0.700 to 0.849) aligned to (Sarstedt et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2022; Zeng, 2023), excellent reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.937 > 0.70 proposed by Cronbach (1951); Taber (2018), and good construct validity (AVE of 0.593 > 0.50), with VIF values (1.806-6.636 < 10) indicating minimal multicollinearity, according to Hair et al. (2021). Similarly, pupil management activities based on these values (X2) exhibit robust β values (0.753-0.841), high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.937), and solid validity (AVE of 0.637), along with VIF values between 2.103 and 5.351 which is not critical concern of multicollinearity, as they remain below the commonly accepted threshold of 10, with only a mild indication of collinearity that does not compromise the model’s reliability (O’Brien, 2007). The social harmony construct (Y) displays strong β values (0.753-0.868), very high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.956), and good validity metrics (AVE of 0.639), with VIF values (2.267-4.905). Finally, the revitalization of national identity (Z) features strong loadings (β-values between 0.726 and 0.868), high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.965), and robust validity (AVE of 0.675), with VIF values (2.187-4.385).

These statistics affirm the effectiveness of integrating Nusantara cultural values in educational contexts, particularly in pupil management and its activities, highlighting their potential to revitalize national identity and social harmony.

Besides, discriminant validity was assessed according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Supplementary Table 3). The statistical findings reveal strong relationships among the constructs, with each explaining a significant portion of its variance (X1: 0.770, X2: 0.798, Y: 0.799, Z: 0.821) according to the standard of Fornell and Larcker (1981). X1 and X2 are moderately correlated (0.669), indicating they are related yet distinct. X1 strongly connects with Y (0.777) and Z (0.773), suggesting that integrating Nusantara cultural values in pupil management enhances social harmony and revitalizes national identity. X2 also has a solid correlation with Y (0.848), highlighting its importance in student management activities. The strong link between Y and Z (0.834) further illustrates the connection between social harmony and the revitalization of national identity. These findings underscore the interconnections among the constructs, supporting further analysis. Overall, this analysis illustrates how these constructs are interlinked and have no problem for further analysis. Finally, the model in Supplementary Table 4 exhibits a good fit based on SRMR, d_ULS, and d_G, but shows a marginal fit according to Chi-Square and NFI, indicating an overall mixed and accepted performance for further analysis.

4.2 Assessment of structural model

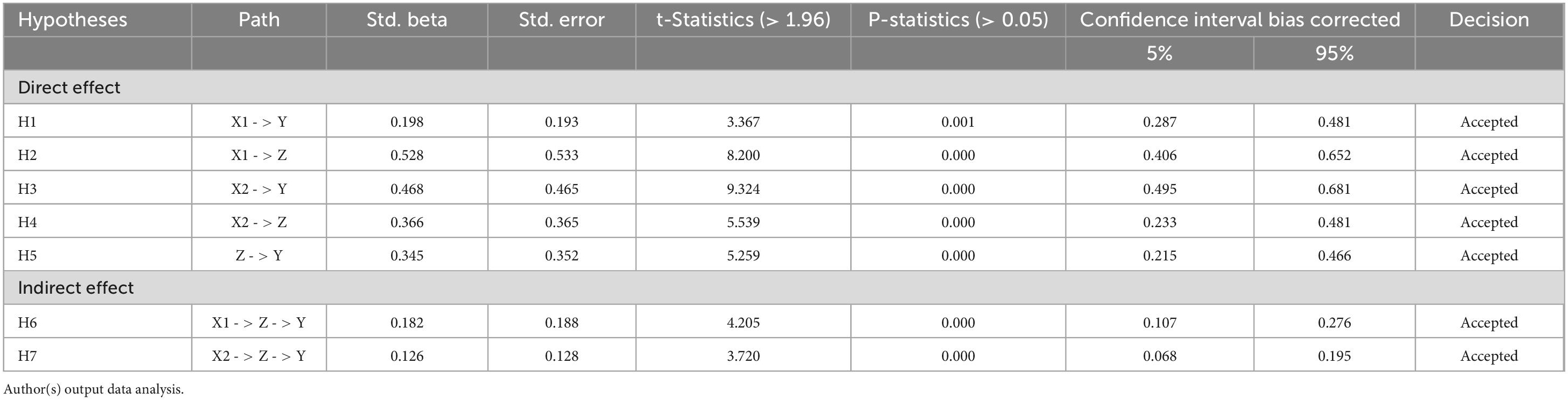

After establishing the reliability and validity of the measurement model using PLS-SEM, the structural model was evaluated, and the hypotheses regarding direct effects were tested. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that the direct effect of the Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in pupil management (X1) on Social Harmony (Y) is positive and significant, with a path coefficient of β = 0.198, a t-value of 3.367, and a p-value of 0.001, thus confirming that H1 is accepted. Similarly, the Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in pupil management (X1) significantly influences the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) with a strong effect (β = 0.528, t-value = 8.200, p < 0.05), leading to the acceptance of H2. For Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2), the direct effect on Social Harmony (Y) is also positive and significant (β = 0.468, t-value = 9.324, p < 0.05), which means H3 is accepted. Additionally, Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2) positively affect the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) (β = 0.366, t-value = 5.539, p < 0.05), supporting H4. Finally, the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) significantly influences Social Harmony (Y) with a strong effect (β = 0.345, t-value = 5.259, p < 0.05), leading to the acceptance of H5.

The indirect effect results are also reported in Table 3, showing that the indirect effect of Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in pupils’ management (X1) on Social Harmony (Y) through Revitalization of National Identity (Z) is positive and significant, with a path coefficient of (β = 0.182), a t-value of (4.205), and a p-value of (0.000), thus confirming that H6 is accepted. Similarly, the indirect effect of Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2) on Social Harmony (Y) via Revitalization of National Identity (Z) is also positive and significant, with a path coefficient of (β = 0.126), a t-value of (3.720), and a p-value of (0.000), leading to the acceptance of H7.

Moreover, after recognizing the importance of the effects between the constructs, the study looked at how well the model predicts outcomes using R2 values. These values show how much of the variation in the outcome, Social Harmony (Y), can be explained by the exogenous variables: Integration of Nusantara Cultural Values in pupil management (X1), Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2), and Revitalization of National Identity (Z) (Supplementary Table 7). According to Hair et al. (2021), values of R2 (0.75, 0.50, and 0.25) indicate strong, moderate, and weak contributions, respectively. In our study, Social Harmony (Y), the R2 value is 0.838, meaning that about 83.8% of its variation is explained by these exogenous factors (X1, X2, and Y), showing a strong connection. Meanwhile, the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) has an R2 value of 0.672, indicating that 67.2% of its variation is explained by the same exogenous variables (X1 and X2), reflecting a moderate effect. This leaves 16.2% of the variation in Social Harmony influenced by other factors not included in the model.

Finally, the f2 effect sizes were used to evaluate how each exogenous variable impacts the endogenous variables in the model. By observing the change in the R2 value when a specific exogenous variable is removed, we can gauge its significance in influencing the outcomes. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively. In this study (Supplementary Table 8), the integration of Nusantara cultural values (X1) has a small effect on social harmony (Y) with an f-2-value of 0.090, showing that it has a limited influence. However, it has a medium effect on the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) at 0.470, indicating a more significant impact. On the other hand, Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2) demonstrate a large effect on Social Harmony (Y) with an f2-value of 0.608, suggesting it plays a crucial role in enhancing social harmony outcomes, while its effect on Z is more modest at 0.226. Lastly, the relationship between Social Harmony and the Revitalization of National Identity shows a small impact with an f2-value of 0.240.

5 Discussion

This study aimed to explore the integration of Nusantara cultural values in pupils’ management and pupils’ management activities influence on the revitalization of national identity and social harmony and determine its direct and indirect effects. Firstly, the model shows that the direct effect of Nusantara cultural values integration in pupils’ management significantly affects social harmony. While the direct effect (β = 0.198) is relatively small, it is still statistically significant and meaningful in the context of educational and social research. This finding aligned with previous studies (Gómez-hurtado et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Polirstok, 2015; Yang et al., 2020). Integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management creates a vibrant atmosphere of social harmony in schools, where students genuinely appreciate and respect one another’s diverse backgrounds. Additionally, the previous study by Imron (2010) aligns closely with these finding, highlighting the importance of integrating the core Nusantara cultural values into pupil management values, such as truth, honor, unity, and respect for elders to foster school social harmony. This can be achieved through effective leadership in implementing these values into pupil management (Gaol, 2023; Sarmini et al., 2023), for instance, instill these values in the curriculum (He et al., 2023; Legbo, 2022; Xia, 2023), and inclusive teaching at schools (Uthus and Qvortrup, 2024). When these values are integrated effectively into pupil management, pupils understand the essence of social harmony, learn to embrace differences, and respond positively to foreign cultures, fostering a sense of belonging and safety for everyone (Eldridge and Cranston, 2009). This nurturing environment encourages acts of mutual assistance and helpfulness, allowing students to connect deeply with one another (Astutik, 2023; Ginting et al., 2023; Pratama et al., 2023).

Secondly, Nusantara cultural values in pupils’ management significantly affect the revitalization of national identity. The effect size of these constructs was moderate. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Ergashev and Farxodjonova, 2020; Huong, 2023; Mukri and Waspiah, 2023; Nguyen, 2021). Integrating national culture, such as Nusantara cultural values, into pupil management deeply enriches students’ understanding of national identity, helping them appreciate the beauty of cultural diversity while fostering a sense of belonging. Furthermore, this conforming a study by Agus et al. (2021), that by embracing Nusantara cultural values such as faith and truth, respect and care, unity and discipline, as well as trust and independence, students connect with their heritage and recognize the importance of their roots. This approach encourages them to take pride in their cultural traditions and to see themselves as part of a larger community that values unity in diversity (Mulyono, 2017). Through pupil management that highlights these values in curriculum, inclusive and multicultural teaching, and civic education in general, pupils not only learn about Pancasila and the richness of their nation’s history but also develop a commitment to preserving this cultural legacy for future generations. Ultimately, this integration helps create a school environment where students feel valued and empowered, strengthening their identities and shared national pride. Hence, the globalization threats such as digital fandoms narrated by Sugihartati (2020), religious conflicts by Nilan and Wibawanto (2023), Korean Wave culture by Lee et al. (2020), and racism issue (Karmila and Budimansyah, 2022) can be manageable.

Thirdly, pupils’ management activities based on Nusantara cultural values significantly affect social harmony. This can be seen through the most prominent effect size contribution. This effect indicates that these activities demonstrate a more pronounced and significant influence than other measured factors. In practical terms, when schools implement management activities centered around these cultural values, the positive outcomes on social harmony—such as improved relationships, tremendous respect among students, and a more inclusive atmosphere—are notably greater than the effects observed from other approaches. This underscores the importance of integrating Nusantara values into pupil management activities to promote a cohesive and harmonious school community. This finding convergent with previous studies (Nur et al., 2023; Yumnah, 2021). As pupils participate in these activities based on Nusantara cultural values, they cultivate important values like helpfulness and tolerance, which encourage them to support one another both in the classroom and beyond (Hanish et al., 2016). This sense of cooperation and connection fosters strong friendships, making every student feel accepted and valued in their school community. Ultimately, these activities and experiences enrich individual relationships and create a vibrant, harmonious school culture that embodies the spirit of unity in diversity (Bhinneka Tunggal Ika), allowing all students to feel at home and part of something larger than themselves (Mejía-Rodríguez and Kyriakides, 2023; Power et al., 2024).

The fourth result indicates the significant effect of pupils’ management activities based on Nusantara cultural values on revitalizing national identity with a moderate effect size. This suggests that while these activities have a meaningful influence on shaping students’ understanding and appreciation of their cultural heritage, the extent of this impact is notable but not excessive. This hypothesis result is consistent with previous studies (Chen and Ma, 2023; Hadj et al., 2022; Jacob and Gardelle, 2020; Smagorinsky, 2022). Through activities like traditional arts and community service, students develop a deeper connection to their roots and learn the importance of values such as unity and respect for diversity, as emphasized in Pancasila and the symbol of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Dharsono, 2017; Fossati, 2021). The moderate effect size indicates that, while these efforts are effective in fostering national identity, there is still room for enhancing these activities to maximize their influence. However, this finding underscores the importance of integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management activities as a vital strategy for nurturing a strong sense of national identity among students, encouraging them to carry these values into their lives and communities. Furthermore, the final direct effect revealed that the revitalization of national identity has a notable impact on social harmony within the school community, even with a small effect size that highlights the importance of this relationship. This direct effect aligns with findings from previous studies (Imron, 2010; Mavroudi and Holt, 2015; Sakti et al., 2024; Suri and Chandra, 2021). By fostering cooperative behavior, students learn the value of teamwork, which enhances their relational competencies and builds trust among peers (Osborn, 2001; Planel, 1997). This spirit of collaboration nurtures mutual respect, allowing students to appreciate the diverse backgrounds that make up their community and strengthen their peer relationships (Hanish et al., 2016; Planel, 1997). As these connections deepen, a strong sense of social cohesion emerges, ensuring every pupil feels safe and valued, a critical factor for their emotional wellbeing. Moreover, when students take pride in their national identity, they contribute actively to a culture of unity and understanding, promoting empathy and support within the school (Hanish et al., 2016; Singh, 1995).

The indirect effect of the structural model measurement exhibits that integrating Nusantara’s cultural values in pupil management significantly affects social harmony at schools via the revitalization of national identity. This finding is coherent with previous studies (Jacob and Gardelle, 2020; Madrohim et al., 2021; Shabrov et al., 2021). Integrating these Nusantara cultural values in pupil management components such as policy, curriculum, and inclusive teaching, pupils can develop a deeper appreciation for their heritage, such as the principles of Pancasila and the symbol of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, which fosters pride in their nation. This strengthens national identity, encouraging respect for diversity. Moreover, as they embrace their national identity, pupils become more involved in community-building activities, reinforcing bonds with their peers and promoting cooperation (Agus et al., 2021; Ariely, 2012; Rusciano, 2003). This engagement nurtures a sense of belonging and cultivates mutual respect and empathy—key ingredients for social harmony. In this area, we recommend that educational institutions should formalize cultural education by integrating traditional values into official school frameworks, establishing partnerships with reputable cultural organizations, and providing comprehensive professional development for educators on culturally responsive teaching methodologies. Concurrently, teachers can incorporate indigenous knowledge systems into their pedagogical approaches, facilitate student-initiated cultural projects, and utilize learning resources that accurately represent Indonesia’s rich multicultural heritage. When students participate in experiential, cultural activities, community engagement initiatives, and structured intercultural dialogues, they develop a stronger national identity, more profound respect for diversity, and build empathic understanding—essential for social cohesion. Educational institutions would benefit from formalizing relationships with community stakeholders to create authentic learning opportunities, ensuring that cultural appreciation extends beyond theoretical knowledge to practical application.

Finally, the indirect effect of pupil management activities based on Nusantara cultural values on social harmony via the revitalization of national identity also demonstrates a significant effect, which is persistent in previous studies (Pratama et al., 2023; Sarmini et al., 2023; Setiawan and Stevanus, 2023). When pupils engage in activities such as celebrating their cultural heritage, community service, and cultural events, they develop a stronger sense of pride in their national identity (Mavroudi and Holt, 2015). This increases respect for diversity as they learn to appreciate different backgrounds and perspectives. Additionally, as they embrace this identity, pupils strengthen their bonds with peers through cooperative activities, fostering mutual respect and empathy, which are core values of Pancasila. Ultimately, this interplay between revitalizing national identity and engaging in cultural activities creates a supportive environment where social harmony can flourish, enabling pupils to coexist peacefully and collaboratively. Speaking about this finding and relevance, when school leaders and teachers thoughtfully design programs that weave cultural activities into everyday school routines, transformation happens - students naturally begin working together across social divides. These are not just add-on activities but carefully crafted experiences that bring Pancasila’s core values to life. Picture students practicing gotong royong (mutual cooperation) while preparing for a school festival or discussing social justice principles while collaborating on community projects. These shared experiences create meaningful connections beyond superficial interactions, allowing young people to develop genuine empathy for classmates from different backgrounds. Moreover, this approach is powerful because it addresses two crucial needs simultaneously: strengthening national identity while fostering meaningful cultural engagement. This creates learning environments where students don’t just tolerate differences - they appreciate them. They discover how to navigate disagreements respectfully and find common ground despite diverse perspectives. Lastly, the outcome extends far beyond classroom walls. Students graduate not just with academic knowledge, but with the social skills and cultural understanding needed to become citizens who actively contribute to Indonesia’s remarkable “unity in diversity” (Bhinneka Tunggal Ika). They become the living embodiment of a harmonious, multicultural nation.

To enhance the study’s real-world applicability, educators should implement structured cultural immersion programs that weave Nusantara values into daily school routines through activities like traditional storytelling, community service projects, and student-led exhibitions, while school administrators establish professional development in culturally responsive teaching and forge partnerships with local cultural institutions for authentic learning experiences. Government support through policy reforms mandating Indigenous cultural values in curricula and targeted funding is essential, especially considering how regional autonomy laws require local education offices to balance community-specific traditions with national identity-building efforts. Financial incentives should prioritize underfunded schools to ensure equitable access to cultural education, with collaborative evaluation frameworks developed by policymakers, school leaders, and educators to measure how effectively these cultural integration strategies foster national identity and social harmony among Indonesia’s diverse student population.

6 Implication

This study highlights the significance of integrating Nusantara cultural values into pupil management, demonstrating that this approach enhances both national identity and social harmony among pupils. The findings contribute to existing research by showing how cultural values help students connect with their heritage and foster a harmonious school community, with national identity playing a key role in improving social interactions and cooperation. Practically, schools should prioritize embedding these values in their curricula and daily activities, promoting respect, unity, and cooperation. Besides, school leaders and teachers must create inclusive environments that celebrate cultural diversity through community events and service projects, which nurture mutual respect and understanding. Lastly, future research should explore the long-term effects of these values on students’ behaviors and identities beyond school, as well as how they adapt as they transition into adulthood. Additionally, comparing different educational settings could reveal effective strategies for promoting social harmony through cultural integration while examining how global influences shape local cultural identities in our rapidly changing world.

7 Limitations and recommendation

This study has some limitations that are important to consider. First, a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional model provides only a snapshot of how Nusantara cultural values relate to national identity and social harmony at a specific point in time. However, it does not account for how these relationships might evolve over time. A longitudinal approach would be beneficial in capturing the dynamic nature of cultural integration and its long-term impact on pupils’ perceptions and behaviors. Additionally, relying solely on self-reported survey data may introduce social desirability bias, potentially influencing responses. The absence of qualitative insights, such as interviews or classroom observations, limits our ability to understand personal narratives and deeper contextual factors that shape cultural values in education.

While the sample size is sufficient for initial findings, it may not fully represent the diversity of schools across Indonesia, which could affect the generalizability of the results. Moreover, the instruments used to measure these constructs may not capture all the complexities of cultural values, as they rely on self-reported perceptions rather than direct observations.

Adopting a mixed-methods approach that integrates qualitative methods, such as teacher or student interviews and classroom observations, would provide a more nuanced perspective for future research. Conducting longitudinal studies could further explore how the integration of Nusantara cultural values develops over time and its sustained influence on national identity and social harmony. Expanding the sample to include more schools from diverse regions would enhance the applicability of the findings. Additionally, refining measurement tools to encompass a broader range of cultural indicators could strengthen the reliability and depth of the study. Overall, these enhancements would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how cultural values shape the educational landscape in Indonesia.

8 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the significant role of integrating Nusantara cultural values in pupil management and pupil management activities and its positive effects on social harmony and national identity. The seven hypotheses proposed provide a comprehensive framework for understanding these relationships: H1 posits that the integration of Nusantara Cultural Values (X1) positively influences Social Harmony (Y), while H2 suggests it significantly impacts the Revitalization of National Identity (Z). H3 indicates that Pupil Management Activities Based on Nusantara Cultural Values (X2) positively affect Social Harmony (Y), and H4 states that X2 also positively influences Z. H5 emphasizes that the Revitalization of National Identity (Z) significantly affects Social Harmony (Y). Additionally, H6 and H7 propose that both integrating Nusantara cultural values and pupil management activities based on Nusantara cultural values influence social harmony through mediation by the revitalization of national identity, demonstrating the interconnectedness of these constructs. In this study, the revitalization of national identity is influenced by the integration of Nusantara cultural values in pupil management and pupil management activities based on these values, which account for 62.7%. Moreover, social harmony is influenced by the integration of Nusantara cultural values in pupil management, pupil management activities based on these values, and the revitalization of national identity, accounting for 83.8%. The remaining influence comes from unexamined variables.

These findings suggest schools should prioritize integrating Nusantara’s cultural values into pupil management through curricula, inclusive teaching, and pupil management activities to foster a cohesive environment by tackling issues in the globalized world regarding digital fandom, religious conflicts, the Korean Wave, racism, and discrimination. However, this study is limited by its quantitative, cross-sectional design, which provides a snapshot view without the depth that qualitative insights could offer. Moreover, the sample size may not fully represent the diversity of schools across Indonesia. Therefore, future research should consider mixed methods, a larger sample, and improved measurement tools to deepen our understanding of how cultural values influence pupils’ social behavior and identity formation.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee State University of Malang. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. AI: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RR: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. EP: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. IM: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SM: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. IS: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research received funding from the Research and Community Service Institute of Universitas Negeri Malang, a Non-State Budget (non-APBN).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely would like to thank Universitas Sari Mulya Banjarmasin, Indonesian Education Scholarship (BPI), Center for Higher Education Funding and Assessment (PPAPT), and Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) from the Ministry of Finance Republic Indonesia for granting the scholarship and supporting this research and all the participants involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1524105/full#supplementary-material

References

Agus, C., Saktimulya, S. R., Dwiarso, P., Widodo, B., Rochmiyati, S., and Darmowiyono, M. (2021). “Revitalization of local traditional culture for sustainable development of national character building in Indonesia BT,” in Innovations and traditions for sustainable development, eds W. Leal Filho, E. V. Krasnov, and D. V. Gaeva (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 347–369. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-78825-4_21

Akaliyski, P., Welzel, C., Bond, M. H., and Minkov, M. (2021). On “Nationology”: The gravitational field of national culture. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 52, 771–793. doi: 10.1177/00220221211044780

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised Ed). London: Verso.

Ardiwidjaja, R., and Antariksa, B. (2022). Pengelolaan tinggalan arkeologi: Kegiatan pelestarian sebagai daya tarik wisata. PURBAWIDYA: J. Penel. Dan Pengembangan Arkeologi 11, 153–164. doi: 10.55981/purbawidya.2022.75

Ariely, G. (2012). Globalisation and the decline of national identity? An exploration across sixty-three countries. Nat. Natl. 18, 461–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2011.00532.x

Astutik, D. (2023). Implementation of multicultural education through school social capital relationships in creating social harmonization. QALAMUNA: J. Pendidikan Sos. Dan Agama 15, 1–16. doi: 10.37680/qalamuna.v15i1.2075

Bearden, W. O., Money, R. B., and Nevins, J. L. (2006). Multidimensional versus unidimensional measures in assessing national culture values: The hofstede VSM 94 example. J. Bus. Res. 59, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.04.008

Blum, L. (2014). Three educational values for a multicultural society: Difference recognition, national cohesion and equality. J. Moral Educ. 43, 332–344. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2014.922057

Chan, R. Y. K., Sharma, P., Alqahtani, A., Leung, T. Y., and Malik, A. (2024). Mediating role of cultural values in the impact of ethical ideologies on Chinese consumers’ ethical judgments. J. Bus. Ethics 191, 865–884. doi: 10.1007/s10551-024-05669-0

Chaplain, R. (2016). Teaching without disruption in the primary school: A practical approach to managing pupil behaviour, 2nd Edn. England: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781315715759

Chen, C., Wang, X., and Chen, F. (2019). Countermeasures of national culture in the context of cultural globalization. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Human. Res. 336, 808–811. doi: 10.2991/icsshe-19.2019.197

Chen, M., and Ma, X. (2023). The contemporary values and practical ways of Chinese national culture education. Stud. Soc. Sci. Res. 4:172. doi: 10.22158/sssr.v4n3p172

Chiang, T. H. (2020). “Is cultural localization education necessary in epoch of globalization?: An analysis of the nature of state sovereignty,” in Handbook of education policy studies: Values, governance, globalization, and methodology, 1st Edn, eds G. Fan and T. S. Popkewitz (Singapore: Springer), 329–341. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8347-2_15

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

Dharsono. (2017). The revitalization of values of cultural precepts in traditional javanese arts. Arts Design Stud. 51, 7–16.

Djumat, I., and Hayun, S. (2021). Internalization of local culture of ternate, eroded by globalization to strengthen the character of the nation in the new normal era (a Literature Review). Int. J. Adv. Res. 9, 917–928. doi: 10.21474/ijar01/12924

Edeh, E., Lo, W.-J., and Khojasteh, J. (2023). Review of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Struct. Equat. Model. Multidiscipl. J. 30, 165–167. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2022.2108813

Eldridge, K., and Cranston, N. (2009). Managing transnational education: Does national culture really matter? J. Higher Educ. Pol. Manag. 31, 67–79. doi: 10.1080/13600800802559286

Ergashev, I., and Farxodjonova, N. (2020). Integration of national culture in the process of globalization. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 477–479. doi: 10.31838/jcr.07.02.90

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Fossati, D. (2021). National identity and public support for economic globalisation in Indonesia. Bull. Ind. Econ. Stud. 57, 61–84. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2020.1747594

Fuad, D. R. S. M., Musa, K., and Hashim, Z. (2022). Innovation culture in education: A systematic review of the literature. Manag. Educ. 36, 135–149. doi: 10.1177/0892020620959760

Gaol, N. T. L. (2023). School leadership in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 51, 831–848. doi: 10.1177/17411432211010811

Garibaldi, M., and Josias, L. (2015). Designing schools to support socialization processes of students. Proc. Manufact. 3, 1587–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.446

Ginting, E. B., Basuki, A., Eliasa, E. I., and Lumbanbatu, J. S. (2023). Implementing multicultural education through relationships with school social capital to promote social harmony. Int. J. Islamic Educ. Res. Multiculturalism (IJIERM) 5, 143–160. doi: 10.47006/ijierm.v5i1.214

Gómez-hurtado, I., Valdés, R., González-falcón, I., and Vargas, F. J. (2021). Inclusive leadership: Good managerial practices to address cultural diversity in schools. Soc. Inclusion 9, 69–80. doi: 10.17645/si.v9i4.4611

Hadj, B. K., Hayat, T., Mokrani, D., and Guezgouz, M. (2022). Identification of national identity through sports and cultural activities. Sport Sci. Pract. Aspects: Int. Sci. J. Kinesiol. 19, 11–17. doi: 10.51558/1840-4561.2022.19.2.11

Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., and Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 109, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Hajisoteriou, C., and Angelides, P. (2020). Examining the nexus of globalisation and intercultural education: Theorising the macro-micro integration process. Global. Soc. Educ. 18, 149–166. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2019.1693350

Hanish, L. D., Martin, C. L., Miller, C. F., Fabes, R. A., DeLay, D., and Updegraff, K. A. (2016). “Social harmony in schools: A framework for understanding peer experiences and their effects,” in Handbook of social influences in school contexts: Social-emotional, motivation, and cognitive outcomes, 1st Edn, eds K. Wentzel and G. Ramani (England: Routledge), doi: 10.4324/9781315769929

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monographs 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

He, Y., Li, T., Fanoos, A., and Päivi, T. (2023). Cross-cultural research on early childhood teacher education curriculum design. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 18, 620–635. doi: 10.1177/17454999231212548

Henseler, J., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comp. Statist. 28, 565–580. doi: 10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Market. 20, 277–319. doi: 10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Hughes, J. (2014). Contact and context: Sharing education and building relationships in a divided society. Res. Pap. Educ. 29, 193–210. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2012.754928

Huong, ĐT. T. (2023). Cultural development in the new phase from the viewpoints of the party and the state. J. Adv. Educ. Philos. 7, 152–156. doi: 10.36348/jaep.2023.v07i05.001

Imron, A. (2010). Profil manajemen sekolah unggulan pada satuan pendidikan sekolah dasar. J. Manajemen Pendidikan 1, 1–14.

Indonesia Development Forum. (2018). Penguatan konektivitas Indonesia sebagai negara kepulauan. Available online at: https://indonesiadevelopmentforum.com/2018/call-for-papers/theme/5-penguatan-konektivitas-indonesia-sebagai-negara-kepulauan (accessed July 24, 2024).

Jacob, C., and Gardelle, L. (eds). (2020). “National identities and the curriculum: Socio-cultural legacies and contemporary questions,” in Schools and national identities in french-speaking Africa (London: Routledge), doi: 10.4324/9780429288944-1

Karmila, P., and Budimansyah, D. (2022). Digital racism: A new form of racism, a threat to the integrity of the nation. Proc. Ann. Civic Edu. Conf. (ACEC 2021) 636, 296–301. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.220108.054

Kunovich, R. M. (2009). The sources and consequences of national identification. Am. Sociol. Rev. 74, 573–593. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400404

Lee, Y. L., Jung, M., Nathan, R. J., and Chung, J. E. (2020). Cross-national study on the perception of the Korean wave and cultural hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia using discourse on social media. Sustainability 12:6072. doi: 10.3390/su12156072

Legbo, T.-I. G. (2022). Exploring the relevance of school-based curriculum development with culture integration. Eur. J. Educ. Pedagogy 3, 36–42. doi: 10.24018/ejedu.2022.3.2.139

Li, D., Gavaldà, J. M. S., and Badia Martín, M. (2022). Listening to students’ voices on inclusive teaching strategies in Chinese primary schools. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 11:2212585X2211209. doi: 10.1177/2212585X221120971

Lin, D., and Zhu, H. (2022). On the long-term construction of ideological and political education system in colleges and universities guided by the status and values of national senior officials—based on students’ emotional behavior driving factors. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25(Suppl._1), A28–A29. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyac032.039

Madrohim, M., Prakoso, L. Y., and Risman, H. (2021). Pancasila revitalization strategy in the era of globalization to face the threat of national disintegration. J. Soc. Polit. Sci. 4, 155–164. doi: 10.31014/aior.1991.04.02.284

Mavroudi, E., and Holt, L. (2015). “(Re)constructing nationalisms in schools in the context of diverse globalized societies,” in Governing through diversity, eds T. Matejskova and M. Antonsich (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 181–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-137-43825-6_10

McNamara, E. (2000). Positive pupil management and motivation: A secondary teacher’s guide, 1st Edn. London: David Fulton Publishers, doi: 10.4324/9781315068633

Mejía-Rodríguez, A. M., and Kyriakides, L. (2023). Searching for the impact of national culture dimensions on student achievement: Implications for educational effectiveness research. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 34, 226–246. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2023.2171068

Meliono, I. (2011). Understanding the nusantara thought and local wisdom as an aspect of the Indonesian education. TAWARIKH: Int. J. Histor. Stud. 2, 221–234. doi: 10.1002/9780470710470.ch17

Minkov, M., and Hofstede, G. (2012). Is national culture a meaningful concept?: Cultural values delineate homogeneous national clusters of in-country regions. Cross-Cult. Res. 46, 133–159. doi: 10.1177/1069397111427262

Moser, S. (2016). Educating the nation: Shaping student-citizens in Indonesian schools. Children’s Geograph. 14, 247–262. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2015.1033614

Mukri, W. M., and Waspiah, W. (2023). Archipelagic Insights in solving national cultural conflicts in Indonesia. Ind. J. Pancasila Global Constit. 2, 35–58. doi: 10.15294/ijpgc.v2i1.62444

Mulyono, M. (2017). The problems of modernity and identity in globalization era. J. Maritime Stud. Natl. Integrat. 1, 106–111. doi: 10.14710/jmsni.v1i2.1819

Nguyen, C. H. (2021). Educating national cultural identity for Vietnamese students: A case study at an Giang University. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 9, 1773–1784. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2021.091006

Nilan, P., and Wibawanto, G. R. (2023). Catholic youth and nationalist identity in Java, Indonesia. J. Contemp. Rel. 38, 41–60. doi: 10.1080/13537903.2022.2139910