- 1University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

- 2Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

This paper explores the intersection of trauma, ethics, and public administration pedagogy, focusing on the impact of intergenerational trauma on students’ comprehension and application of ethical theories in post-colonial contexts such as South Africa. The aim of the study is to critically examine how traditional Western ethical frameworks, such as deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics, align—or fail to align—with the lived experiences of students affected by historical trauma, and to explore the development of context-specific ethical frameworks rooted in African philosophical thought. The study employs a critical narrative review methodology, synthesizing recent literature on trauma, ethics education, and decolonising pedagogy to identify key challenges and gaps in existing research. The analysis reveals that traditional ethical frameworks often fail to address the cognitive and emotional barriers faced by students from marginalised communities, whose historical and collective trauma impedes their engagement with abstract ethical theories. In particular, the findings highlight a critical gap in trauma-informed pedagogical strategies, which are essential for fostering a deeper understanding of ethics in public administration. The paper concludes that contextually constructed ethical frameworks, particularly those informed by African philosophical traditions like Ubuntu, offer a more relevant and effective approach to ethics education in post-apartheid South Africa. The study recommends the integration of trauma-sensitive, context-specific pedagogical strategies to enhance the ethical decision-making capacities of public administration students. Additionally, it calls for the use of technological and pedagogical innovations, such as virtual simulations and interdisciplinary approaches, to advance the teaching of ethics to trauma-affected populations. These recommendations aim to prepare future public servants for the complex ethical challenges they will encounter in governance and public service, particularly in societies shaped by historical trauma.

1 Introduction

The educational landscape in South Africa remains significantly influenced and constructed by the historical and social legacy of apartheid. The apartheid regime (1948–1994) which comprised of While English and Afrikaner members of the National Party not only enforced racial segregation but also created a tiered education system where resources and opportunities were disproportionately allocated along racial lines. While white South Africans benefited from well-funded institutions, the majority of Black South Africans were confined to under-resourced schools, resulting in a legacy of educational inequality that continues to affect service delivery, public administration and pedagogy today (Fernandez and Fernandez, 2020; Naidoo, 2019). Despite various educational reforms, the remnants of apartheid-era inequities persist, contributing to ongoing disparities in access to quality education, and limiting efforts toward meaningful transformation in the public sector, including Public Administration (Roberts, 2021; Dipitso, 2021). The enduring effects of these inequities on pedagogy underline the need for a critical examination of how ethical frameworks are taught in these contexts. In this introduction, the use of the terms inequalities, inequities and disparities is meant to convey injustices within the post-apartheid South African context that emanate from its prejudicial past. Inequalities pertain to structural imbalances that continue to plague the educational system in relation to resources, quality and infrastructure (Fernandez and Fernandez, 2020; Naidoo, 2019). The term inequities serves the purpose of emphasising the unfairness of such inequalities, while disparities refer to differences that continue to persist in the education system (Fernandez and Fernandez, 2020; Naidoo, 2019).

Two decades following the end of apartheid, the educational system in South Africa continues to exhibit gross inequalities that continue to perpetuate intergenerational trauma and ethical decision making, particularly among Black students from historically marginalised backgrounds (Dipitso, 2021; Mabokela and Mlambo, 2017). Disparities in the education system continue to persist regardless of post-independence educational reforms which are aimed at decolonising the educational system. Consequently, there are upstream factors that continue to be the hallmark of the South African educational system which include the reliance on Western theories and practices and curriculum biases (Mabokela and Mlambo, 2017). These influence downstream issues on a student level which include continued intergenerational trauma and the continued attribution of blame on individuals while neglecting systemic issues that need to be addressed.

This review is critical for multiple reasons. Firstly, it provides an examination of the current pedagogical approaches to teaching ethical theories—such as deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics—within South Africa’s Public Administration education. Secondly, it highlights the gaps in current research that fail to address the intersection of intergenerational trauma and ethics education, particularly in post-colonial contexts (Meny-Gibert, 2022; Naidoo, 2019). Moreover, the review underscores the importance of developing context-specific theories that can better equip students with the ethical tools necessary for public service in a country still grappling with the consequences of apartheid (Ngwenya, 2019; Roberts, 2021). Given that much of the existing literature focuses on either trauma or ethical theories independently, there is a clear gap in exploring how these domains intersect in the educational setting, particularly in post-apartheid South Africa.

The primary goal of this review is to examine how intergenerational trauma affects the comprehension and application of ethical theories within Public Administration pedagogy. By addressing this gap, the review aims to contribute to the development of a more nuanced and contextually relevant approach to ethics education that acknowledges the lived experiences of South African students. This is crucial not only for improving the academic understanding of ethical decision-making but also for enhancing the effectiveness of public service delivery in a country that continues to grapple with the legacy of apartheid (Waghid and Davids, 2022; Rispel, 2023; Sesanti, 2023). Through this exploration, the review seeks to advocate for the integration of trauma-sensitive pedagogies that better align with the social and historical realities of students in post-apartheid South Africa.

Given this critical background, the paper unfolds as a critical narrative review. The rationale for this approach in exploring the influence of intergenerational trauma on ethical theory understanding is that it is more rigorous, requiring an interpretative analysis of dominant discourses within the literature, while highlighting critical gaps that require further exploration (Theile and Beall, 2024). Therefore, unlike other types of narrative reviews, for instance descriptive reviews, it extends beyond merely summarising literature. Additionally, critical narrative reviews have been proven to be suitable for exploring complex research phenomena that involve political, historical and even contextual issues (Theile and Beall, 2024). The main research question upon which the review is premised is, in post-apartheid South Africa how does intergenerational trauma affect teaching practices and the learning of ethical frameworks in the discipline of Public Administration? This question will be explored based on two main objectives which are, (i) to critically analyse the current body of literature on intergenerational trauma and ethics education, and (ii) to highlight critical gaps in current ethics education pedagogies and to advocate for context-specific pedagogies that take into account the lived experiences of South African students, resulting in better outcomes in the sphere of public service.

2 Conceptualisation of historical trauma

Historical trauma is acknowledged as a by-product of cultural and physical suppression (Gone et al., 2019; Koenig, 2022; Smallwood et al., 2021). Mutuyimana and Maercker (2023, p. 7) provide the following definition for historical trauma:

“…Psychological and emotional injuries shared collectively across generations resulting from past collective traumatic experiences or events, manifesting in perceived discrimination and oppression, learned mistrust, exhaustion and feelings of humiliation, cultural-related syndromes and historical thoughts of loss, associated with various clinical psychological disorders and risk behaviours within a group that share a similar social, historical, and political backgrounds.”

While we acknowledge the contribution of this definitionwe do not agree with the exclusion of colonization by Mutuyimana and Maercker (2023, p. 7) as a prerequisite for historical trauma (Gone et al., 2019). This paper includes the perspective of (Joo-Castro and Emerson, 2021), which suggests that historical trauma encompasses the shared recollection of societal turmoil and disturbances that have reshaped a community’s beliefs, values and lifestyle. It additionally represents the cumulative scars of past injustices that persistently influence present-day populations through intergenerational inheritance. In this definition we find justification for the inclusion of communities such as Indigenous South Africans who experienced the effects of colonisation through the apartheid regime. Trauma is progressively understood as being intergenerationally transmitted, leading to long-term effects on the affected. It is particularly prevalent in Indigenous populations, where it is linked to poorer health outcomes and the need for culturally safe holistic care (Joo-Castro and Emerson, 2021; Gone et al., 2019; Smallwood et al., 2021).

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Intergenerational trauma

Intergenerational trauma which also referred to as transgenerational trauma is transmitted from generation to generation (Isobel et al., 2019), particularly in post-colonial contexts like South Africa where it has profound impacts on individuals and communities. According to Hesse and Main (2000, cited in Isobel et al., 2019, p. 1101) intergenerational trauma can be defined “as the process by which parents with unresolved trauma transmit this to their children via specific interactional patterns, resulting in the effects of trauma being experienced without the original traumatic experience or event.” The experiences often shape the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural responses to current social structures (Cerdeña et al., 2021). This type of trauma is characterised by the transmission of the emotional, psychological, and social consequences of historical violence, including colonialism, across generations (Cerdeña et al., 2021). Transmission takes place through parenting practices, socialisation, memory sharing and evident systemic inequalities. The transmission of intergenerational trauma is a critical topic to consider due to its significance in shaping human through and behaviour. To this effect, research has shown that inherited trauma can affect cognitive processes such as memory, learning, and decision-making, particularly in contexts that require engagement with complex ethical frameworks (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Matheson et al., 2022). An example of this can be drawn from experiences of trauma amongst Indigenous peoples in Canada which has been shown to have impacts that extend beyond mental health to seriously affect engagement in and participation within education and professional contexts (Matheson et al., 2022). As this research outlines, historical trauma perpetrated through colonial policy-in the form, for example, of the Indian Residential School system-continues as a self-perpetuating cycle of trauma which inhibits the ability for Indigenous individuals to function effectively within institutional environments and thus leads to disengagement both academically and professionally (Elias et al., 2012).

Under the “colonial trauma” theory (which highlights how collective psychological and emotional wounds caused by colonisation are transmitted across generations, moulding people’s collective identity, behaviour, as well as social systems), it would seem that some of the impacts brought about by the accumulation of these colonial policies can be captured by ongoing mental health disparities, disconnection with cultural practices, and challenges in institutional participation (Mitchell, 2019). Moreover, educational settings often fail to address intergenerational trauma, which can account for the dropping-out rate or lower levels of institutional engagement found among Indigenous students, linked to some barriers relating to the residential school legacy (Gaywsh and Mordoch, 2018).

In South Africa, the long-term psychological impacts of apartheid on Black communities manifests in feelings of alienation and dislocation, which may impair the ability to critically engage with abstract ethical concepts (Knight, 2019). Similarly, traumatic legacies from apartheid continue to influence educational spaces, affecting both educators and students, which results in students who are disconnected from conventional teaching methods that do not consider historical trauma (Barlow, 2018; Pentecost, 2021).

This trauma-informed perspective is essential for understanding why students in South Africa, particularly those from historically marginalised communities, struggle with the cognitive demands of ethical decision-making in academic contexts, and more tragically, when they join the world of work. When these challenges are addressed within pedagogical frameworks that acknowledge historical trauma, it allows for more nuanced, trauma-sensitive educational strategies, which are crucial for fostering deeper engagement with ethical theories. Recognising the historical and psychological burdens carried by students is a key step in reshaping how ethical decision-making is taught, highlighting the necessity for contextually relevant teaching methods that can accommodate the cognitive pathways shaped by trauma (Kizilhan and Wenzel, 2020; Wyatt, 2023).

3.2 Ethical theories in public administration

Ethical theories such as deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics are foundational frameworks that guide decision-making in Public Administration, shaping how many future public servants approach ethical dilemmas. Deontology emphasizes adherence to rules and duties, positioning ethical decision-making as a matter of following established principles regardless of the outcomes. In contrast, utilitarianism advocates for decisions that produce the greatest good for the majority of people; it focuses on consequences rather than adherence to pre-existing rules. Virtue ethics emphasizes the character and moral development of the decision-maker, suggesting that ethical actions stem from individuals who are virtuous (Matsiliza, 2020; Roberts, 2021).

The utilitarian approach, which is based on the Greatest Happiness Principle, asserts that actions are righteous to the extent that they contribute to happiness -of other people- and wrong to the degree that they result in unhappiness. An individual with intergenerational trauma from apartheid may face significant challenges in aligning their actions with the principles of utilitarianism due to the deep psychological and emotional impacts of trauma, which affect their ability to objectively evaluate outcomes for the ‘greater good.’ This happens because intergenerational trauma can distort one’s perception of trust, safety, and fairness, making it difficult to detach personal and collective pain from ethical reasoning processes that require impartial evaluation of broader societal outcomes. Utilitarianism, advocates for ethical decision-making based on maximising the overall happiness or benefit of the majority, and requires a level of emotional detachment and rational calculation that can be difficult for trauma-affected individuals, especially when their personal experiences with injustice and suffering shape their ethical worldview (Isobel et al., 2021). Utilitarianism demands the sacrifice of one’s own well-being for the greater good, which may be difficult to reconcile when approaching life from a position of loss or disadvantage, and especially if they observe that their individual needs or experiences are dismissed in the pursuit of collective happiness.

Barrow and Khandhar (2023) suggest that deontologists evaluate actions according to widely accepted moral standards, irrespective of their actual outcomes. Deontological ethics, emphasises adherence to moral rules or duties irrespective of consequences, whether anticipated or otherwise, posing potential challenges for trauma survivors. Adherence to strict moral principles may be difficult when their experiences have revealed the complexities and ambiguities of real-world situations. Trauma has the tendency to disrupt one’s sense of safety and trust, potentially leading to skepticism about the reliability or universal application and applicability of moral rules. Furthermore, their lived experiences and transgenerational trauma may lead to an internal struggle with feelings of guilt or low self-concept if they perceive themselves as unable to meet the rigorous standards of deontological ethics.

Virtue ethics, as articulated by Zeigler-Hill and Shackelford (2020), suggests the habit of making prudent choices, relative to an individuals’ circumstances, all the while governed by principle. Virtue ethics, emphasises the cultivation of moral character and the development of virtues such as courage, justice, and temperance. It requires individuals to act in accordance with these virtues as part of their moral reasoning. However, for those with intergenerational trauma, the ethical alignment required can be difficult due to the lasting effects of historical trauma on their worldview, emotional resilience, and sense of self-efficacy (Isobel et al., 2021). Trauma impairs emotional regulation and cognitive functions, which are critical for the development of the stable moral character required by virtue ethics (Giotakos, 2020). Individuals affected by trauma may experience heightened anxiety, depression, or dissociation, which can hinder their ability to consistently apply virtuous traits like patience or empathy in challenging situations. In higher education, virtue ethics acquired through pedagogical practices from teaching practitioners plays a pivotal role in upholding dignity and instilling ethics and values in students (Tripathy, 2020). Furthermore, virtue ethics offers a structured approach to sustainable development, emphasizing the character of individuals and their capacity for positive change (Jena and Kar, 2020).

The collective memory of injustice and oppression experienced during apartheid may lead individuals to distrust societal norms and institutions that promote virtue ethics. Trust is foundational to moral development and ethical action, yet for many, the systemic injustices of apartheid have created a deep mistrust of both public and private institutions (Le Grange, 2016). This lack of trust undermines the willingness to adopt virtues like justice or fairness, which are often seen as aligned with the same systems that perpetuated historical injustices. As a result, individuals may struggle to internalize virtues that appear disconnected from their lived experiences of historical and structural injustice (Matsiliza, 2020).

These ethical frameworks are critical for public administrators as they encounter a range of ethical challenges in governance and service delivery. However, in post-apartheid South Africa, where public servants operate within a context of deep-seated historical trauma, these frameworks may not fully resonate with the lived experiences of those affected by intergenerational trauma (Ngwenya, 2019; Knight, 2019). Trauma can distort ethical reasoning by inhibiting the ability to engage with the abstract reasoning required in deontological or utilitarian ethics. This disconnection necessitates a re-examination of how -and possibly what- ethical theories are taught, advocating for pedagogical models that more than just introduce students to traditional frameworks, but also address the cognitive and emotional challenges posed by trauma (Waghid and Davids, 2022).

This review highlights the need to integrate ethical teaching with trauma-informed educational strategies, allowing for the development of a more contextually relevant pedagogy. Doing so acknowledges the limitations of traditional ethical frameworks in post-colonial contexts and advocates for approaches that incorporate the socio-historical realities of students. This is essential for developing public administrators who can make ethical decisions that are both theoretically sound and grounded in a deep understanding of the communities they serve (Rispel, 2023; Sesanti, 2023).

4 Schools of thought and controversies

4.1 Decolonising pedagogy: exploring different schools of thought

The notion of decolonsing pedagogy has gained popularity in recent years, with educators and scholars debating the appropriate ways to dismantle colonial legacies in education systems, particularly in post-colonial countries like South Africa. One school of thought argues for the need to develop contextually constructed ethical theories, which resonate with the lived experiences and historical backgrounds of students affected by colonialism (Le Grange, 2016). These proponents suggest that traditional Western ethical frameworks, such as deontology and utilitarianism, fail to address the specific socio-historical contexts of students from formerly colonised nations (Le Grange, 2016). This perspective is grounded in the notion that education should not only be a tool for acquiring knowledge but also a means of restoring cultural identity and agency to historically marginalised peoples. By incorporating indigenous knowledge systems and African philosophy, educators demonstrate that traditional ways of being were inherently ethical, and they can develop ethical frameworks that students would want to identify with, and that are more relevant to individuals in post-colonial settings.

Conversely, some scholars argue that while the decolonisation of pedagogy is necessary, completely discarding Western ethical theories might undermine the universal applicability of ethics in globalised governance and public administration (Le Grange, 2016). The universal principles embedded in these ethical systems are valuable for public administration in diverse societies but seem to require contextual adaptation to avoid reinforcing colonial legacies (Le Grange, 2016). It is also argued that these misapplications arise primarily because Western ethical theories were developed in contexts vastly different from post-colonial societies (Le Grange, 2016). Deontology, for example, emphasises duty and adherence to universal moral laws, yet applying rigid deontological principles in settings shaped by systemic injustice can easily overlook the lived realities of those who have historically been oppressed, and more who have inherited the trauma (Delgado-Alemany et al., 2020). This creates a disconnect between ethical theory and practical governance, as Western frameworks may not fully address the complex socio-historical dynamics of post-colonial nations (Akor, 2019). According to Akor (2019) frameworks such as utilitarianism and deontology are not inherently colonial but have been applied inappropriately in certain contexts. Instead of rejecting these theories outright, these scholars advocate for a hybrid model that integrates both ethical approaches from the Global North and the Global South, allowing for a more holistic and inclusive ethical pedagogy (Heleta, 2016; Garuba, 2015). Such integration, they argue, would prepare students for ethical decision-making in a global context while still addressing the specific needs of post-colonial societies. This view posits that ethical universality, when contextualised properly, can contribute to a more inclusive education system, where both global and local ethical concerns are addressed.

Despite the argument that Western ethical frameworks such as utilitarianism and deontology have universal applicability, the fact that the education system itself is perceived as a colonial construct complicates their acceptance. Many post-colonial scholars contend that because these educational institutions were historically vehicles for promoting colonial values, everything they espouse—including ethical principles—is often viewed as part of that oppressive legacy (Heleta, 2016; Le Grange, 2016). As a result, instruments used to regulate behaviour, such as ethical frameworks grounded in Western philosophy, are frequently regarded as mechanisms of continued subjugation. This perception is particularly prevalent in societies like South Africa, where education has long been associated with the enforcement of colonial ideologies, leading to a deep distrust of the ethical systems it promotes (Garuba, 2015; Chilisa, 2019). Consequently, even well-intentioned ethical frameworks can be viewed with skepticism, as they are seen as perpetuating the very systems of oppression they aim to address (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This underscores the need for decolonised approaches to ethics education that are culturally relevant and rooted in the socio-historical realities of the populations they serve.

Another significant debate within decolonising pedagogy revolves around the role of language and the epistemic dominance of English in formerly colonised countries. Proponents of decolonisation contend that the use of English as the primary language of instruction perpetuates the colonial legacy by marginalising indigenous languages and epistemologies (Chilisa, 2019). This school of thought argues that language is a critical medium through which knowledge is constructed and transmitted; thus, the continued dominance of English inherently privileges Global North modes of thinking and excludes other cultural perspectives. Apart from that, the dominance of English affects the ability of students who use English as a second, third or even fourth language to understand the underlying concepts behind different ethical theories and frameworks. A critical examination of South Africa and its 11 recognised official languages, coupled with the influence of a large migrant population from other countries also adds complexities in language use in the country and reveals a context where people are exposed to many indigenous languages before English. However, English remains the official language of instruction in education and students with limited exposure will also have limited understanding. As a response, scholars advocate for bilingual or multilingual education systems that incorporate indigenous languages as a way to decolonise the classroom and make education more inclusive and accessible to all students (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018) (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). However, opponents argue that in a globalised world, fluency in English is necessary for economic mobility and global participation, and thus, English should maintain a central role in education, albeit with efforts to include indigenous perspectives.

Despite these debates, a consensus exists around the importance of creating a more inclusive curriculum that reflects the diverse cultural and historical backgrounds of students. Mbembe (2015) emphasises the need to decolonise the curriculum by revising syllabi to include African history, philosophy, and ethical systems that have been marginalised in favor of Eurocentric perspectives. This approach would enable students to critically engage with ethical dilemmas that are grounded in their lived realities, thus enhancing the relevance of education in post-colonial contexts (Mbembe, 2015). However, critics argue that simply revising the curriculum is insufficient; they suggest a deeper restructuring of educational institutions themselves, to address systemic inequalities and power imbalances that continue to reflect colonial structures (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). Addressing these inequalities requires more than just updating syllabi—it calls for a fundamental restructuring of the entire educational system. From a systems perspective, the curriculum is only one component; to truly decolonise education, changes must also occur at the institutional, administrative, and policy levels. This means revisiting everything from the governance structures of educational institutions to the recruitment and training of educators, the allocation of resources, and the methods of assessment and evaluation (Chilisa, 2019).

The debates surrounding decolonising pedagogy reflect broader conflicts between universalism and contextualism in ethics. While some scholars advocate for the complete replacement of ethical frameworks from the Global North, with contextually constructed theories, others argue for a hybrid approach integrating both global and local perspectives. Regardless of the specific approach, there is agreement on the need to make education more inclusive and reflective of the diverse cultural and historical experiences of students in post-colonial societies.

4.2 Controversies in the role of trauma in ethical understanding

The relationship between trauma and ethical decision-making has sparked significant controversy within academic discourse, particularly regarding how intergenerational trauma influences students’ capacities to engage with complex ethical frameworks. Some scholars argue that trauma, particularly intergenerational trauma, hinders ethical understanding by impairing cognitive functions necessary for moral reasoning, such as memory, critical thinking, and empathy (Isobel et al., 2021; Matheson et al., 2022). In this view, trauma is seen as a cognitive and emotional burden that affects students’ ability to comprehend abstract ethical concepts, such as deontology or utilitarianism. Trauma may cause students to be overly self-protective or emotionally disengaged, which limits their capacity for ethical reflection and decision-making in both academic and professional settings (Cerdeña et al., 2021). This perspective is particularly prevalent in studies of post-colonial and post-apartheid contexts, where the psychological scars of historical injustices continue to affect contemporary educational outcomes.

The existing epistemology needs to be so designed that trauma can enrich ethical understanding by fostering a deeper sense of empathy and moral responsibility. In this approach, students who have experienced trauma, or whose communities have suffered historical injustices, have the opportunity to develop heightened ethical sensitivities and a greater capacity for moral reasoning due to their personal experiences with injustice (Knight, 2019; Wyatt, 2023). This argument is grounded in the notion that individuals who have suffered trauma are more likely to identify with marginalised or vulnerable populations and are therefore better equipped to engage with ethical dilemmas that involve issues of justice, equality, and human rights. For example, students in post-apartheid South Africa may be guided on how they can draw on their own communities’ experiences of oppression to develop a more nuanced and compassionate approach to ethical decision-making, particularly in fields such as public administration, where they may encounter ethical dilemmas related to social justice and equity in service delivery.

Another controversy centers on the role of trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education. Advocates of trauma-informed education argue that educators must acknowledge the role of intergenerational trauma in shaping students’ ethical understanding and adapt their teaching methods accordingly (Barlow, 2018; Le Grange, 2016). This approach requires the integration of psychological support systems within the educational framework, enabling students to process their trauma while simultaneously engaging with ethical content. Trauma-informed pedagogy may include creating safe spaces for students to discuss their experiences, incorporating therapeutic practices into the classroom, and adjusting curricula to better reflect the psychological realities of trauma-affected students. Proponents argue that this approach not only enhances students’ ability to engage with ethical theories but also promotes healing and resilience (Ngwenya, 2019; Waghid and Davids, 2022). However, critics argue that such approaches may inadvertently pathologise students or lower academic standards by over-accommodating emotional responses at the expense of rigorous ethical engagement (Heleta, 2016; Garuba, 2015).

In addition, the debate over whether trauma-informed ethical teaching should focus on addressing personal trauma or if it should also incorporate collective or historical trauma, adds another complexity. Some scholars argue that focusing exclusively on personal trauma may individualise the experience of trauma and obscure the broader social and historical forces that contribute to collective suffering (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018; Mbembe, 2015). In this view, trauma-informed pedagogy should engage with historical trauma at both the individual and collective levels, helping students understand how their personal experiences are shaped by systemic injustices, such as colonialism or apartheid. This approach would enable students to engage with ethical issues from a broader, more contextualised perspective, promoting a more comprehensive understanding of ethical dilemmas that affect both individuals and communities.

The controversies surrounding the role of trauma in ethical understanding highlight the complex ways in which trauma can hinder or when differently engaged, enrich moral reasoning. Our paper argues that trauma impairs cognitive processes essential for ethical decision-making, and that it adversely affects the understanding of ethical theory and essentially ethical behaviour. The discussions of trauma-informed pedagogy also emphasize a tension between the need to balance academic rigor with sensitivity to the affective needs of students who have experienced trauma. This is indicative of a polarised view on the role that educational spaces ought to assume in relation to trauma, particularly within subjects such as ethics and humanities. Some instructors insist on an integrative approach whereby the pursuit of emotional safety should be prioritised as a way of avoiding re-traumatization among students, given that exposure to traumatic content will in all likelihood stir distress that, if not sensitively managed, would destroy learning processes entirely (Carello and Butler, 2014).

Others still propose a “safe space” model, purporting that knowledge of trauma provides an important building block for social justice. In light of this, they suggest that trauma-informed pedagogies enable classrooms to be democratized as spaces in which experiences of trauma become part of the learning process (Carter, 2015). This has the risk of potentially “dumbing down” of higher education or focus too intently on student emotions rather than mastery over subject matter. These debates highlight a need for a balanced approach that incorporates flexibility, fosters resilience, and respects the integrity of academic content. This nuanced view stresses that while trauma-informed approaches are important in considering engagement, they must not be used to lower academic expectations (Petersen and Nkomo, 2022).

5 Fundamental concepts, issues, and problems

5.1 Challenges in teaching ethical theories to traumatised populations

Trauma can profoundly affect cognitive processes related to comprehension and engagement with complex ethical concepts, making teaching ethical theories to students affected by historical and intergenerational trauma uniquely challenging. Students who have inherited the psychological and emotional legacies of colonialism, apartheid, or other systemic oppressions often struggle with abstract reasoning and critical thinking, which are essential for understanding traditional ethical frameworks like deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics (Isobel et al., 2021). Trauma often manifests in ways that impair concentration, memory retention, and emotional regulation, which leads to difficulty in following and applying complex theoretical constructs (Cerdeña et al., 2021). The dynamic life experiences further exacerbate the challenges educators face in adapting their teaching methods to meet the needs of students, while ensuring that the rigor of ethical education is maintained.

Many educators in the Public Administration discipline in South Africa have either lived through the apartheid regime or are deeply affected by the trauma passed down through generations. This historical burden makes the first and most significant challenge in their teaching an internal one—their own trauma. Educators are not immune to the emotional triggers that surface when teaching subjects closely tied to their personal or collective histories. As a result, they carry an additional cognitive and emotional load that intensifies the already challenging task of teaching complex ethical theories. This internal struggle can lead to emotional fatigue, burnout, and, in some cases, a disconnection from the material they are expected to teach (Isobel et al., 2021). In this context, trauma is not just a personal burden but an invisible weight that complicates the process of delivering ethical education with the depth and nuance it requires.

The influence of unresolved trauma also extends to how educators perceive and communicate ethical concepts, particularly when the concepts seem to clash with their lived experiences of systemic injustice. For example, many educators who lived through apartheid may find it difficult to champion abstract, universal ethical principles—such as those found in utilitarianism or deontology—without critically questioning their relevance in a society that still grapples with deep social inequalities. Having witnessed or inherited the impacts of systemic oppression, these educators might see firsthand how these Western frameworks have often failed to address the complexity of ethical dilemmas within contexts marked by racial, economic, and social injustice (Le Grange, 2016). This can create an unintentional bias, where some educators strictly adhere to the curriculum, possibly in an effort to suppress their own emotional responses, while others may hesitate to fully engage with the material, fearing their own trauma might seep into their teaching.

Moreover, educators who have inherited or directly experienced intergenerational trauma often struggle to create trauma-sensitive learning environments for their students. Their own experiences of trauma can blur their ability to empathize fully with the struggles of their students, or it may hinder their capacity to maintain an emotionally safe classroom (Barlow, 2018). This internal conflict can result in inconsistencies in their teaching, where trauma resurfaces unpredictably, affecting not only how they teach but also how they connect with their students. In such cases, both educators and students are trapped in a cycle where trauma undermines the learning process, particularly in subjects like ethics, which are critical for shaping future public servants. These future leaders must possess the moral clarity and emotional resilience to navigate complex ethical dilemmas in governance, yet their own education is compromised by the unresolved trauma that impacts both teacher and student alike (Waghid and Davids, 2022).

One of the key issues in teaching ethical theories to traumatised populations is the emotional disengagement that students may exhibit as a coping mechanism. Research indicates that trauma-affected students may dissociate from emotionally charged subjects, such as ethical dilemmas that evoke feelings of injustice or inequality (Knight, 2019). This emotional detachment can prevent students from fully engaging with ethical content, resulting in a superficial understanding of the theories being taught. Furthermore, students from historically marginalised communities may perceive traditional ethical frameworks from the Global North as irrelevant or even as a perpetuation of oppression, given that these theories often fail to account for the socio-historical realities of their communities (Chilisa, 2019; Le Grange, 2016). This creates an additional barrier to comprehension, as students may resist engaging with content that they view as disconnected from their lived experiences.

Another significant challenge is the psychological impact of trauma, which can result in heightened anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues that interfere with learning. Trauma-affected students may feel overwhelmed by the demands of academic life, particularly when ethical theories require deep critical reflection and engagement with abstract principles (Matheson et al., 2022). These students often require additional support, such as trauma-informed teaching strategies, to help them navigate the psychological barriers that impede their ability to fully comprehend ethical theories (Barlow, 2018). Trauma-sensitive teaching practices, such as providing safe spaces for discussion and incorporating reflective exercises, can help to mitigate some of these psychological barriers, but these strategies are not always implemented in a consistent or effective manner across educational institutions (Roberts, 2021). The lack of a standardised approach to trauma-informed pedagogy, from which to design pedagogy, leaves a critical gap in how ethical theories are taught to these vulnerable populations.

6 Reflexivity statement

In conducting this study on the intersection of trauma, ethics, and public administration pedagogy, it is imperative to acknowledge the positionality of the researchers and how their lived experiences shape the lens through which they interpret and engage with the subject matter. This paper is authored by three African scholars, each with distinct yet intersecting backgrounds in public administration, psychology, and higher education. Their collective experiences—both personal and professional—provide an intimate understanding of the challenges associated with navigating trauma, ethical decision-making, and the struggle for epistemic justice in post-colonial contexts such as South Africa.

The first author, an African scholar and Postdoc Fellow in the Public Governance discipline, has a deep-rooted understanding of the complexities of governance and ethics in the South African context. Their lived experience of historical and structural inequalities informs their critical perspective on the limitations of traditional ethical theories, particularly those originating from Western philosophical traditions. Having personally encountered the barriers imposed by colonial legacies—both intellectually and socially, the first author recognises the cognitive dissonance that students from historically marginalised backgrounds experience when attempting to engage with ethical concepts that do not reflect their realities and often times could appear divergent. This awareness drives their commitment to exploring alternative, contextually relevant ethical frameworks that integrate African philosophical traditions, such as Ubuntu, into the pedagogy of Public Administration.

The second author holds a Master’s degree in psychology and brings a nuanced understanding of trauma and its impact on cognitive processing and learning. Having taught multigenerational and ethnically diverse students in higher education, they have first-hand experience of how trauma-whether historical, collective, or individual-affects students’ ability to engage with abstract ethical theories. Her background in psychology enables her to critically examine how trauma-informed pedagogy can enhance the teaching and comprehension of ethics. The psychological lens she brings to this study underscores the importance of integrating trauma-sensitive strategies into public administration curricula, ensuring that students from historically marginalised communities can meaningfully engage in ethical decision-making without being retraumatised by the learning process.

The third author is a seasoned academic with over 20 years of experience in teaching public administration, previously worked in the South African public sector in the 1980s, − during and after the apartheid era. This dual exposure to governance in both pre- and post- democratic South Africa provides him with a unique vantage point in assessing ethical dilemmas in public administration. His first-hand witness to the transition from apartheid to democracy allows for a critical interrogation of the ethical frameworks that have historically guided governance and the need for their transformation to be more inclusive of African epistemologies. Having personally experienced and navigated systemic barriers, he brings to this study an acute awareness of how historical trauma continues to shape the ethical consciousness of students aspiring to work in the public sector.

Collectively, the authors recognise the tension between Western ethical paradigms and African lived realities. Their own academic journeys have required engagement with Western-influenced definitions and theories, often demanding a temporary disassociation from their lived experiences to make sense of dominant epistemologies. However, through continuous reflection, scholarship, and engagement with students, they have come to appreciate the interconnectedness of Global North and Global South values in ethical discourse. This realisation has reinforced their commitment to decolonising ethics education by advocating for pedagogical approaches that validate and integrate African philosophical traditions alongside global ethical theories.

The authors’ shared lived experience of trauma and resilience further strengthens their perspective on the importance of contextually relevant ethical education. They have personally grappled with the psychological and structural barriers that hinder professional and academic advancement, and they recognise similar struggles in their students. By incorporating trauma-informed pedagogical strategies and advocating for ethical frameworks rooted in African traditions, they seek to create a more inclusive and empowering learning environment for public administration students in post-apartheid South Africa.

Their positionality, therefore, is both a source of insight and a guiding principle for this study. They approach the research with a deep commitment to fostering ethical leadership in the public sector, not through the wholesale adoption of Western theories, but through a critical synthesis that acknowledges the historical and socio-cultural realities of their students. This work is not merely an academic exercise but a reflection of their own intellectual and personal journeys-an attempt to reconcile the dissonance between inherited epistemologies and lived realities while advocating for a transformative approach to ethics education in the public sector.

7 Methodology

In conducting the narrative literature review, a non-systematic, but purposeful review strategy was utilised. The emphasis in determining the articles to include in the review was on fulfilling the mandate of the paper by focusing on conceptual alignment and the historical context. The academic databases from which the reviewed articles were obtained include Google Scholar, Scopus and Taylor & Francis Online, SpringerLink and PsycINFO. These were chosen because they provide access to peer-reviewed journals; thus, the search terms that were used include intergenerational trauma, ethics education, post-apartheid pedagogy teaching, deontology, virtue ethics, utilitarianism and Public Administration pedagogy. To enhance the search Boolean operators AND, OR and NOT were utilised to direct the search towards the desired article titles and content.

There are three main inclusion criteria that were used to select the articles that were included in thematic analysis. These included (i) the focus area, thus articles needed to focus on intergenerational trauma, ethics education and higher education; (ii) the key themes in the articles which needed to align conceptual foundations of this paper including historical injustices and inequalities and decolonial pedagogies; (iii) the publication period with the focus being on articles that were published from 2015 to 2024. This publication period was chosen to enhance the opportunity for identifying seminal works that have shaped the discourse on intergenerational trauma and ethics education.

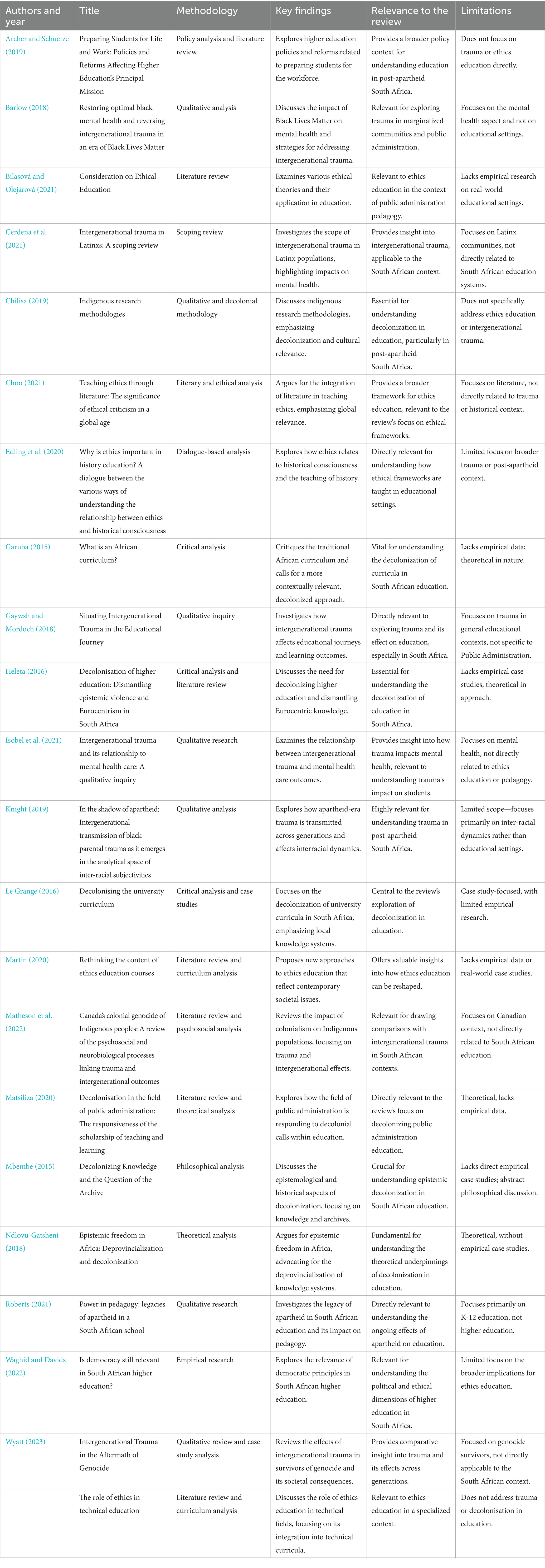

A total of 22 articles were included in the review and they are summarised in the following Table 1.

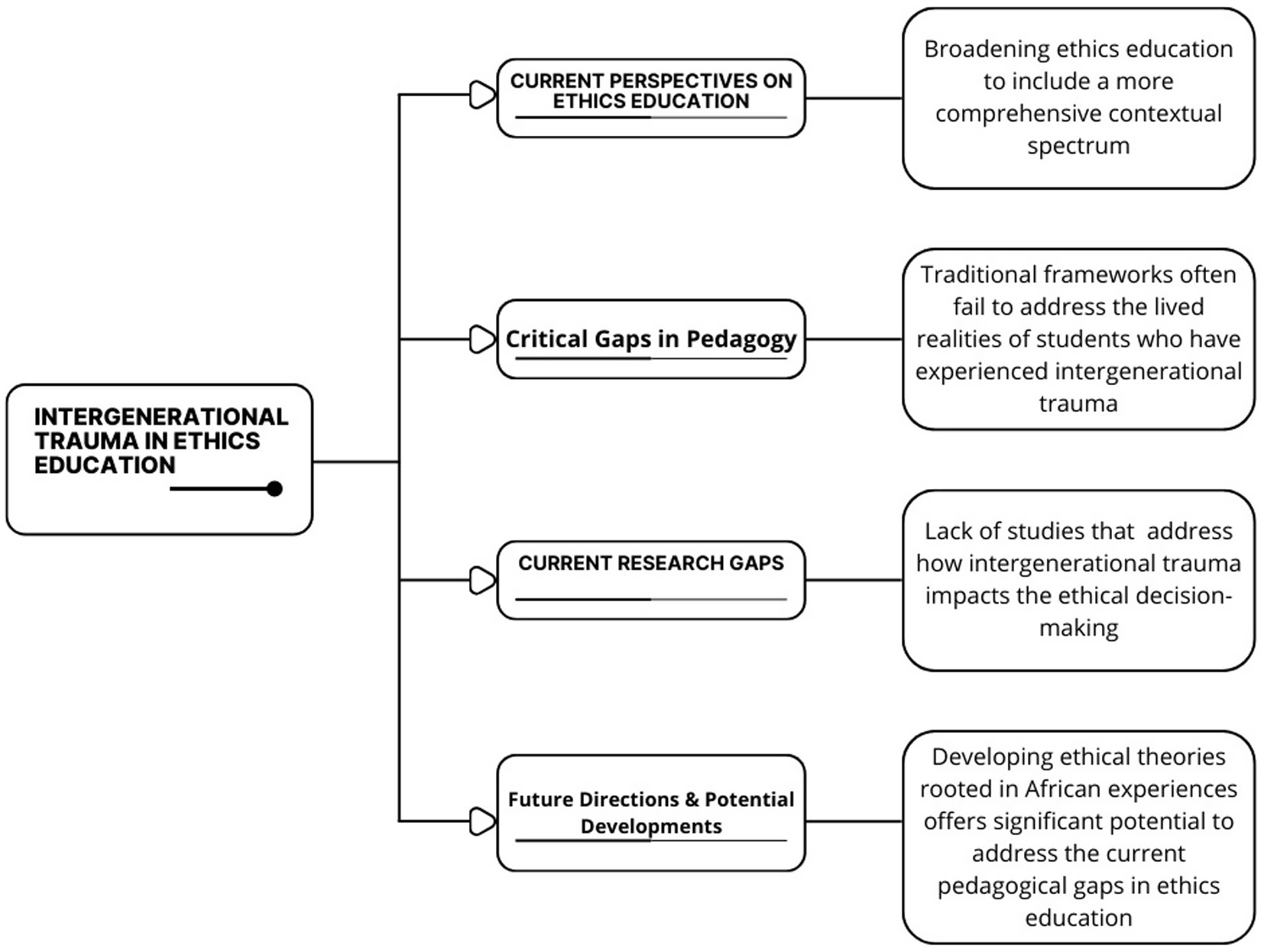

Thematic analysis of the summarised articles using Atlas ti resulted in the identification of key themes that pertain to the research question. These themes focus on the current perspectives in ethics education, critical gaps in pedagogy, current research gaps, as well as future directions and potential developments. A brief illustration of the themes which is discussed in detail in the thematic discussion to follow is provided in Figure 1.

8 Thematic discussion of findings

The crux of this discussion is the emphasis on highlighting the perspectives in the current body of literature regarding ethics education. In line with the research question and the objectives thereof, that discussion cannot be complete without locating where the gaps are and providing direction for future research.

8.1 Current perspectives on ethics education

Recent studies highlight the importance of broadening ethics education to include a more comprehensive cultural spectrum, prioritising the development of individual ethical perspectives (Martin, 2020). Ethics play a pivotal role in molding individual character and principles, giving ethics education particular significance (Choo, 2021; Edling et al., 2020) particularly in institutions of higher education. Another central objective in ethics education is the emphasis of the cultivation of moral consciousness and proficiency in ethics (Bilasová and Olejárová, 2021; Edling et al., 2020).

We concur with Martin (2020) who laments the approach of ethics education courses highlighting that they predominantly revolve around communicating traditional ethical theories which have their origins in American and European moral philosophy. In addition, the attempt at a practical application of the theories through case studies and deliberation on ethical decision-making models with no contextual application is often used when teaching ethics in South African settings. The primary objective of ethics courses remains the enhancement of ethical reasoning skills. However, advancements in related disciplines such as psychology and learning and leadership development suggest the need for a review of current curricula. Ethics education requires adaptation to the psychological dynamics and workplace realities of South African communities encompassing a variety of ethical principles. While the perspective of deontology, utilitarianism and virtue ethics retain relevance, we interrogate whether the overarching aim to facilitate the nurturing of individual ethical perspectives in our students is plausible. Therefore, ethics educational courses should incorporate insights from the Global South -non-Western philosophies-, and integrate contextual advancements from fields like psychology, leadership development, sociology and neuroscience.

The current emphasis on Western ethical frameworks in the teaching and learning pedagogy such as deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics in public administration scholarship overlooks the rich diversity of ethical perspectives from other cultures and regions, particularly the Global South. Our understanding of the attempt to broaden ethics education to include non-Western philosophies, such as African Ubuntu, Eastern Confucianism, or Indigenous ethics has exposed global students to a better understanding of ethics while suggesting the interconnectedness of our world. Institutions of higher education have the potential to support and influence the development of students for the world of work in rapidly changing environments suggesting an uncertain future (Pretti and McRae, 2021). This can be effectively achieved by using innovative pedagogical approaches and technologies designed to address issues. The impact of policies and reforms on higher education’s mission of preparing students for life and work is also a key consideration (Archer and Schuetze, 2019).

8.2 Critical gaps in pedagogy

Traditional ethical frameworks such as deontology and utilitarianism often fail to address the lived realities of students who have experienced intergenerational trauma. These frameworks tend to be rooted in Western philosophical traditions, which may not resonate with students from post-colonial contexts, where historical trauma continues to shape individual and collective experiences (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018).

The literature on ethical education has also been slow to acknowledge the impact of trauma on students’ ability to engage with abstract ethical concepts. While there is a growing body of research on trauma-informed pedagogy, much of this work focuses on emotional and psychological support, rather than on how trauma affects students’ engagement with specific academic content, such as ethical theories (Isobel et al., 2021; Chilisa, 2019). This gap in the literature means that educators often lack the tools and frameworks needed to effectively teach ethical theories to trauma-affected populations. For example, traditional case-based methods of teaching ethics, which often rely on hypothetical scenarios may not be effective for students whose experiences of injustice and trauma are deeply personal and real (Waghid and Davids, 2022). These students may find it difficult to engage with abstract ethical dilemmas that do not reflect the complex realities of their own lives, which in turn limits their ability to fully understand and apply the ethical principles being taught in their lives and in the world of work.

Another significant gap in pedagogy is the lack of integration of indigenous ethical frameworks into the curriculum. In many post-colonial contexts, indigenous knowledge systems offer valuable ethical insights that are often overlooked in favor of philosophical traditions with their origins in the Global North (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). For example, African ethical systems such as Ubuntu emphasize community, empathy, and collective responsibility—values that are particularly relevant in trauma-affected populations where the legacy of historical injustices continues to affect social cohesion (Chilisa, 2019). However, these ethical systems are rarely included in the curriculum, leaving a critical gap in how ethical education is delivered to students from diverse cultural backgrounds. This failure to incorporate non-Western ethical frameworks not only limits students’ understanding of ethics but also perpetuates the epistemic violence that decolonising pedagogies seek to address (Heleta, 2016).

Furthermore, there is a gap in the practical application of ethical theories for students who will enter public service roles in post-colonial societies. Traditional ethical frameworks often emphasize individual decision-making and abstract principles, such as duty or utility, without fully considering the social and historical contexts in which ethical decisions are made (Mbembe, 2015). For students in public administration programs, this lack of contextualisation can lead to a disconnect between the ethical theories they learn in the classroom and the complex, real-world ethical dilemmas they will face in their careers (Garuba, 2015). These students need ethical frameworks that are not only theoretically sound but also practical and applicable in the contexts of governance, public policy, and social justice—contexts that are often shaped by the legacies of colonialism, inequality, and systemic violence.

8.3 Current research gaps

Current research on the intersection of trauma, ethics, and public administration pedagogy reveals several critical gaps. While research has been conducted on trauma’s effects on cognitive processes, much of this literature has focused on personal trauma or trauma in clinical contexts rather than collective or intergenerational trauma within academic settings (Cerdeña et al., 2021). Furthermore, although there is a growing interest in trauma-informed pedagogy, these studies often emphasize emotional and psychological support rather than exploring how trauma impacts students’ ability to engage with complex ethical theories in the field of public administration (Barlow, 2018). More than this, it does not map out the far-reaching implications in the public sector relating to service quality and service delivery. This presents a significant gap in the literature, as students from historically marginalised communities frequently encounter ethical dilemmas in their professional lives that are deeply intertwined with their own socio-historical contexts.

Another limitation in current studies is the lack of empirical research exploring how ethical theories are taught to students affected by historical trauma. While theoretical discussions on the role of ethics in public administration are abundant, there is a paucity of studies that investigate the pedagogical strategies employed to teach these concepts to trauma-affected populations (Knight, 2019). Moreover, most existing studies on ethics in public administration tend to focus on philosophical traditions originating from the Global North, often neglecting to consider how these theories resonate—or fail to resonate—with students from post-colonial contexts like South Africa (Heleta, 2016; Garuba, 2015). As a result, there is little guidance for educators on how to adapt their teaching methods to better suit the needs of students who may have inherited the psychological and emotional burdens of historical injustice. This gap in the literature underscores the need for more research on context-specific pedagogical strategies that can engage students with diverse cultural and historical backgrounds.

A further limitation lies in the lack of interdisciplinary studies that examine the intersection of trauma, ethics, and pedagogy within the specific context of public administration. Research on ethics education is often siloed within philosophical or pedagogical domains, while studies on trauma tend to focus on psychology or social work. Few studies bridge these disciplines to provide a comprehensive understanding of how trauma affects students’ engagement with ethical theories, particularly in fields like public administration where ethical decision-making has profound implications for governance and social justice (Chilisa, 2019; Le Grange, 2016). Addressing this interdisciplinary gap is crucial for developing more holistic approaches to ethics education, particularly in post-apartheid South Africa, where the legacies of colonialism continue to shape both the personal and professional lives of public servants.

There is a growing need for the development of ethical frameworks that are more attuned to the socio-historical context of South Africa, particularly in the field of public administration. Critics argue that traditional Western ethical theories, such as deontology and utilitarianism, often fail to resonate with students from post-colonial contexts as they scarcely adequately reflect the lived realities of communities affected by historical trauma (Heleta, 2016; Mbembe, 2015). These frameworks are rooted in philosophical traditions that emerged in vastly different cultural and historical contexts, and their application in post-apartheid South Africa can feel disconnected from the ethical dilemmas faced by public servants in the country today. For example, Western ethical theories often emphasise individual decision-making, whereas African cultural systems, prioritise collective responsibility (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This divergence underscores the need for context-specific ethical frameworks that are grounded in African values and philosophies.

However, not all scholars agree that abandoning Western ethical theories is the solution. Some argue that these theories offer valuable insights that can be applied in any cultural context, provided they are adapted to reflect local realities (Garuba, 2015; Waghid and Davids, 2022). From this perspective ethical universality is possible but it requires careful contextualisation to ensure that abstract ethical principles are relevant to the socio-historical conditions of the students being taught. For example, deontological principles of duty and obligation can be reframed within an African ethical context by emphasising the responsibilities that public servants have to their communities, rather than focusing solely on individual moral duties (Roberts, 2021). Similarly, utilitarian considerations of the greater good can be integrated with African culture which prioritises social harmony and collective well-being. This balanced approach suggests that it is possible to retain the theoretical rigor of Western ethical frameworks while adapting them to meet the needs of African students in post-colonial societies.

The need for context-specific ethical frameworks also extends to the practical application of ethics in public administration. Public servants in South Africa are frequently confronted with ethical dilemmas that are deeply rooted in the country’s colonial and apartheid past, such as issues related to inequality, corruption, and social justice (Matsiliza, 2020). Western ethical theories which often emphasize neutrality and impartiality, may not adequately address these complexities, as they tend to overlook the historical and structural factors that shape ethical decision-making in post-colonial contexts (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This has led to calls for ethical frameworks that are not only theoretically robust but also attuned to the specific ethical challenges faced by public servants in post-apartheid South Africa. For example, scholars have suggested incorporating African philosophical traditions into public administration curricula as a way to foster ethical decision-making that is more responsive to the socio-historical realities of the country (Le Grange, 2016).

At the same time, it is important to recognise the potential risks of over-contextualising ethical frameworks. Critics warn that an excessive focus on local context can lead to ethical relativism, where moral standards are seen as entirely contingent on cultural or historical circumstances (Garuba, 2015; Chilisa, 2019). This could undermine the development of a coherent ethical framework for public administration, as it may result in a fragmented or inconsistent approach to ethical decision-making. Instead, proponents of a more balanced approach argue that while ethical frameworks should be context-sensitive, they must also adhere to certain universal principles of justice, fairness, and accountability. This perspective emphasises the need to strike a balance between adapting ethical theories to local conditions and maintaining a commitment to universal ethical standards that can guide public servants in making fair and just decisions, regardless of the specific cultural or historical context in which they operate (Waghid and Davids, 2022).

8.4 Future directions and potential developments

Developing ethical theories rooted in African philosophical thought offers significant potential to address the current pedagogical gaps in ethics education, especially in post-colonial contexts like South Africa. One prominent African ethical philosophy is Ubuntu, which emphasizes community, interconnectedness, and shared humanity. In contrast to the individualism central to the Global North ethical frameworks, Ubuntu underscores the moral responsibility of individuals to contribute to the well-being of their community, making it a more relevant ethical system in contexts where social cohesion and collective justice are paramount (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018; Chilisa, 2019). In the public administration discipline, where ethical decision-making affects entire communities, incorporating Ubuntu into ethical education better equips students to navigate complex ethical dilemmas that require balancing individual rights with collective responsibilities (Le Grange, 2016).

The integration of African philosophical thought into ethics education could also address the shortcomings of Western frameworks like deontology or utilitarianism, which often do not fully reflect the socio-historical realities of post-colonial societies (Mbembe, 2015). For example, while deontology focuses on adherence to universal principles, it often neglects the contextual nuances that may influence ethical decision-making in societies marked by deep historical trauma. In contrast, an Ubuntu-based ethical theory could provide students with a more holistic perspective on ethics by emphasizing reconciliation, empathy, and collective responsibility, values that resonate deeply in post-apartheid South Africa (Garuba, 2015). Additionally, incorporating African ethics into the curriculum can empower students by affirming their cultural identities and addressing the epistemic violence perpetuated by the dominance of Western thought in higher education (Heleta, 2016).

Future developments in this area could involve a greater collaboration between African philosophers, educators, and policymakers to develop comprehensive ethical frameworks that align with both African values and the demands of modern governance. This would not only foster a more inclusive pedagogy but also contribute to the development of ethical leaders who are deeply attuned to the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they operate (Waghid and Davids, 2022). The construction of such contextually relevant ethical theories is critical for preparing future public servants to navigate the ethical complexities inherent in governance and public service in post-colonial societies.

Integrating trauma-sensitive, context-specific ethical education into public administration programs can greatly improve ethical decision-making in South Africa’s public service. Public servants often face complex issues rooted in historical inequalities and social injustices. Training in trauma-sensitive frameworks enhances their ability to empathize with marginalized communities and fosters a deeper understanding of the ethical consequences of their decisions (Isobel et al., 2021). This approach equips public servants to address social justice and inequality with greater sensitivity to historical trauma, leading to more equitable policy outcomes (Matheson et al., 2022).

Additionally, trauma-sensitive education promotes ethical reflexivity, encouraging public servants to critically reflect on their biases and ethical frameworks (Cerdeña et al., 2021). This is crucial in addressing the legacies of apartheid, such as racial discrimination and economic inequality (Roberts, 2021). Incorporating African ethical principles like Ubuntu can further align public service policies with community values, fostering trust between government and the public (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). Ultimately, this education will not only enhance the ethical competencies of public servants but also contribute to more just and effective governance.

Technological and pedagogical innovations hold immense potential to advance the teaching of ethics, particularly in trauma-affected populations. Digital tools, such as online platforms and virtual simulations, can provide students with immersive learning experiences that allow them to engage with ethical dilemmas in a controlled and reflective environment (Waghid and Davids, 2022). For example, virtual reality (VR) simulations can recreate real-world ethical challenges that public servants may face, allowing students to practice ethical decision-making in a safe space where they can reflect on the consequences of their choices (Garuba, 2015). This kind of experiential learning is particularly valuable for trauma-affected students, as it allows them to engage with ethical content at their own pace and in a way that minimises the emotional risks associated with real-world decision-making.

In addition to VR, digital platforms can also be used to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge-sharing among students, educators, and public service professionals. Online discussion forums, for example, can create spaces where students can engage with ethical dilemmas from multiple perspectives, encouraging them to critically reflect on their own biases and assumptions (Matsiliza, 2020). Furthermore, these platforms can provide trauma-affected students with access to psychological support resources, allowing them to process their trauma while engaging with ethical content in a supportive and trauma-informed environment (Le Grange, 2016).

Pedagogical innovations, such as the use of interdisciplinary approaches, can also enhance the teaching of ethics in trauma-affected populations. By integrating insights from psychology, sociology, and history, educators can provide students with a more holistic understanding of ethical decision-making that considers the socio-historical context in which ethical dilemmas arise (Heleta, 2016). For example, incorporating lessons on the psychological effects of trauma into ethics courses can help students develop a deeper understanding of how trauma affects cognitive processes, emotional regulation, and moral reasoning (Roberts, 2021). This interdisciplinary approach not only enriches students’ ethical education but also provides them with the tools they need to navigate the complex ethical challenges that arise in post-colonial societies like South Africa.

The use of technological and pedagogical innovations in ethics education also offers opportunities for personalised learning. Trauma-affected students often have unique learning needs that may not be addressed by traditional teaching methods (Isobel et al., 2021). Digital tools, such as adaptive learning platforms, can provide students with customised learning experiences that are tailored to their individual needs, allowing them to engage with ethical content in a way that is both accessible and meaningful. These platforms can also offer real-time feedback, helping students reflect on their ethical decision-making processes and adjust their approaches as needed (Cerdeña et al., 2021). Personalised learning not only enhances student engagement but also helps trauma-affected students overcome the cognitive and emotional barriers that can impede their ability to engage with complex ethical theories.

9 Conclusion and recommendations

The development of a more inclusive ethics education pedagogy in an increasingly globalised world, is beneficial to professionals, scholars, and leaders who find themselves working across cultural boundaries. This approach will nurture a more comprehensive understanding and respect for different value systems, which is essential for meaningful collaboration and addressing global challenges such as pandemics, climate change, human rights, and social justice. All of which are dealt with by Public Administrators at various levels and points of the service delivery cycle. The inescapable influence of Western-centric theories, models and frameworks on ethics education in the Global South run the risk of being understood as perpetuating colonial legacies. Broadening our scholarship and pedagogy to incorporate Global South perspectives increases the chances of its citizens embracing ideas that have existed in their communities before colonial times and provide a practical gateway to decolonising knowledge and acknowledging the intellectual contributions of historically marginalised regions.

The future directions and potential developments in the teaching of ethics to trauma-affected populations offer a range of possibilities for addressing the current gaps in pedagogy. By developing ethical theories rooted in African philosophical thought, such as Ubuntu, educators can create more contextually relevant frameworks that resonate with students’ lived experiences. The integration of trauma-sensitive ethical education into public administration programs has the potential to enhance ethical decision-making in public service sectors, fostering more just and effective governance. Finally, technological and pedagogical innovations, such as virtual simulations, interdisciplinary approaches, and personalised learning platforms, offer new ways to engage trauma-affected students with ethical content, making ethics education more inclusive and impactful.

Author contributions

SN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CT: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TN: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. This manuscript acknowledges the use of generative AI tools for refining the language and enhancing clarity. The tools were used strictly in an editorial capacity to improve readability and ensure effective communication of ideas. All intellectual contributions, conceptualisations, and analyses presented in the manuscript are the work of the authors.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akor, E. U. (2019) In quest for an ethical and ideal post-colonial African democratic state: The cases of Nigeria and South Africa

Archer, W., and Schuetze, H. G. (Eds.) (2019). Preparing students for life and work: Policies and reforms affecting higher education’s principal Mission. Leiden & Boston: Brill.

Barlow, J. N. (2018). Restoring optimal black mental health and reversing intergenerational trauma in an era of black lives matter. Biography 41, 895–908. doi: 10.1353/bio.2018.0084

Barrow, J. N., and Khandhar, P. B. (2023). Deontology. In: StatPearls [online]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Bilasová, V., and Olejárová, G. P. (2021). Consideration on ethical education. Acta Univ. Bohem. Merid. 24:24. doi: 10.32725/acta.2021.005

Carello, J., and Butler, L. D. (2014). Potentially perilous pedagogies: teaching trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. J. Trauma Dissociation 15, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.867571

Carter, A. M. (2015). Teaching with trauma: disability pedagogy, feminism, and the trigger warnings debate. Disabil. Stud. Q. 35. doi: 10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4652

Cerdeña, J. P., Rivera, L. M., and Spak, J. M. (2021). Intergenerational trauma in Latinxs: a scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 270:113662. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113662

Choo, S. S. (2021). Teaching ethics through literature: The significance of ethical criticism in a global age. Abingdon, Oxon & New York: Routledge.

Delgado-Alemany, R., Blanco-González, A., and Díez-Martín, F. (2020). Ethics and deontology in Spanish public universities. Educ. Sci. 10:259. doi: 10.3390/educsci10090259

Dipitso, O. (2021). Higher education post-apartheid: insights from South Africa. Higher Educ. 84:1. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00780-x

Edling, S., Sharp, H., Löfström, J., and Ammert, N. (2020). Why is ethics important in history education? A dialogue between the various ways of understanding the relationship between ethics and historical consciousness. Ethics Educ. 15, 336–354. doi: 10.1080/17449642.2020.1780899

Elias, B., Mignone, J., Hall, M., Hong, S. P., Hart, L., and Sareen, J. (2012). Trauma and suicide behaviour histories among a Canadian indigenous population: an empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada's residential school system. Soc. Sci. Med. 74, 1560–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.026

Fernandez, S., and Fernandez, S. (2020). “Addressing the legacy of apartheid” in Representative bureaucracy and performance: public service transformation in South Africa, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 69–111.

Gaywsh, R., and Mordoch, E. (2018). Situating intergenerational trauma in the educational journey. Education 24, 3–23. doi: 10.37119/ojs2018.v24i2.386

Giotakos, O. (2020). Neurobiology of emotional trauma. Psychiatriki 31, 162–171. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2020.312.162

Gone, J. P., Hartmann, W. E., Pomerville, A., Wendt, D. C., Klem, S. H., and Burrage, R. L. (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: a systematic review. Am. Psychol. 74, 20–35. doi: 10.1037/amp0000338

Heleta, S. (2016). Decolonisation of higher education: dismantling epistemic violence and eurocentrism in South Africa. Transform. High. Educ. 1, 1–8. doi: 10.4102/the.v1i1.9

Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., Furness, T., and Foster, K. (2019). Preventing intergenerational trauma transmission: a critical interpretive synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 1100–1113. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14735

Isobel, S., McCloughen, A., Goodyear, M., and Foster, K. (2021). Intergenerational trauma and its relationship to mental health care: a qualitative inquiry. Community Ment. Health J. 57, 631–643. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00698-1

Jena, A., and Kar, S. (2020). Virtue ethics a framework for sustainable development. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 7, 965–970.

Joo-Castro, L., and Emerson, A. (2021). Understanding historical trauma for the holistic care of indigenous populations: a scoping review. J. Holist. Nurs. 39, 285–305. doi: 10.1177/0898010120979135

Kizilhan, J., and Wenzel, T. (2020). Concepts of transgenerational and genocidal trauma and the survivors of ISIS terror in Yazidi communities and treatment possibilities. Int. J. Ment. Health Psychiatry 6:1037532. doi: 10.37532/ijmhp.2020.6(1).174