- Department of Applied Educational Sciences, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Knowledge about how quality in extended education is defined, formulated, and communicated regarding quality-related problems in educational practices, and school leaders’ roles in these processes is limited. This article presents findings from research focusing on educational quality in extended education in Sweden (commonly known as School-age educare) is defined by school leaders in one Swedish municipality. The data examined written documents associated with governance and organizations of School-age educare created by school leaders at different levels of one Swedish municipality. The analysis of data was based on the concepts of Bernstein’s pedagogical codes (2003), and from Scherp and Scherp's School organization model (2007). The results revealed that the educational-pedagogical code dominated, and the leisure-pedagogical and social-pedagogical codes only appeared sporadically in the analyzed documents. A new ‘educational-economic’ pedagogical code emerged during analysis. It included formulations indicating that quality can be addressed by economic actions. The analyzed documents revealed power structures between different levels of school leaders, and also a lack of shared understanding and definition of quality in extended education. School leaders should discuss, and agree on, what quality in extended education includes and not only rely on quantitative and measurable aspects of this educational practice.

1 Introduction

Quality in education is a ‘hot’, multi-faceted contemporary issue in many ways. A critical element of problematization is that the notion of high educational quality is often defined, measured, and quantitatively compared through assessments of individual pupils’ knowledge (Biesta, 2009), rather than contributions to the common good in society (UNESCO, 2021). This issue is particularly problematic if quality criteria that are applied to schools are also applied in extended educational practices such as School-age educare, which are traditionally mandated to provide care and social inclusion, as far as possible, in addition to education (Andersson, 2020). Extended education in Sweden is called School-age educare (SAEC) and is hereafter referred to that name and abbreviation. SAEC is supposed to provide complementary care before and after the school day, including meaningful care, play and restorative activities in a socially inclusive setting, in addition to formal classroom teaching (Klerfelt et al., 2020; Klerfelt and Ljusberg, 2018). Understanding the quality has been limited. A Swedish study has shown that SAEC centers have often acted more as extended forms of compulsory schools, with associated focus largely on individual educational attainment, rather than the traditional complementary activities (Memišević, 2024). Thus, important elements of educare in Swedish SAEC seem to have been lost, or at least substantially diminished. Local school leaders play prominent roles not only in the formation and maintenance of educational practices, but also the communication and application of pedagogical ideas and values of their staff, pupils, and caretakers (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023b). This article presents a study of how educational quality in SAEC from one Swedish municipality as defined by school leaders from various levels of the school organization originating in official documents. The aim is to contribute knowledge of how quality in SAEC is defined, formulated, and communicated regarding quality-related problems in Swedish SAEC practices, and school leaders’ roles in these processes. The study was guided by the following research questions:

• How is quality in SAEC defined and formulated by school leaders in municipal documents?

• What pedagogical codes are present in the written definitions of SAEC quality?

• What are the implications of school leaders’ definitions of quality for SAEC practices?

2 Educational quality in extended education

Measurable elements of educational quality include not only pupils’ educational performance (nationally assessed) but also practice guidelines such as numbers of pupils per class, and areas available for indoor and outdoor activities (Swedish School Inspectorate, 2010). The latter are intended to ensure that educational conditions are equal and fair, or at least meet acceptable minimum standards, but this approach to defining the quality concept and associated practices has been questioned and problematized by educational philosophers and researchers (Biesta, 2009; Dahlberg et al., 2007). Briefly, this is because educational quality defined solely in measurable terms is rooted in a too narrow view of the purpose of education, which should not offer individuals possibilities of meaning-making solely through pre-defined educational goals (Biesta, 2014). Critics note the complementary importance of social elements that promote the development of wellbeing and justice for all (UNESCO, 2021). The associated problems may be particularly complex in contexts such as preschool (cf. Moss, 2017) and extended education, with broader aims than merely teaching and acquiring individual knowledge (such as school practice in general). In research focusing on educational quality in extended education in German speaking parts of Europe emphasis are on what effects extracurricular activities may have on academic achievements for pupils (i.e., Schuepbach, 2015). In a meta-analysis from the United States the results show an optimistic development of intellectual skills as well as social, physical and academic performance when attending after-school programs (Durlak et al., 2010). In a research study, the guidelines and children’s perspectives of Swedish SAEC centers and German all day schools are compared (Fischer et al., 2022). The result of this comparison reveals that the educational policy in the two countries is similar regarding development of for example, social skills, health, life-long learning, and well-being. However, the German quality framework, unlike the Swedish curriculum, also emphasize the academic skills (Fischer et al., 2022). When extended education mainly focuses on academic learning there is a risk of “schoolification” (Klerfelt and Stecher, 2018, p. 56) of the practice. Research in Swedish extended education has shown that educational practices of care are also framed and measured in a similar manner to those aiming to increase knowledge, such as in school (Memišević, 2024). This framing also has important performative implications, as assumed expectations and measurements of educational practices guide and affect those practices, including the definition and assessment of quality, as well as efforts to provide it (Löfdahl and Pérez Prieto, 2009; Löfgren, 2016).

2.1 School leadership and educational quality

The term “School leaders” is here used as a general term for all types of educational leaders where some have responsibility for whole school organizations, and some are principals with responsibility for one school unit. Especially principals play prominent roles in the formation and maintenance of educational practices, and both the communication and application of pedagogical ideas and values by their staff, pupils, and caretakers. Besides this, research point to that school leaders of today also are obliged to handle economic issues, in which it is argued that entrepreneurial leadership can be beneficial in this matter (Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz and Pashiardis, 2022). In the same vein, Hallinger (2003) finds that principals’ leadership can be seen a process of development that is affected by the local school context for example financial resources, and the structure of the organization. In addition to providing opportunities to govern and develop extended education, school leaders must also maintain continuous dialog and collaboration with the staff, i.e., shared leadership (Kielblock, 2025) about the daily work and how to develop extended education practices. A further task for school leaders in Sweden is to organize SAEC in a manner that favors cooperation between SAEC staff, preschool classes and the schools. This also provides important overviews of the pupils’ development, learning and education. Principals must also consider pupils’ ages, staff competence, design of premises and the outdoor environment, and adapt the staff density and both sizes and composition of groups to enable delivery of the SAEC mission (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023a). The Swedish National Agency for Education’s latest assessment of the state of the education system (2023a), highlights challenges faced in SAEC. This regards quality related to its mission, including impacts of a shortage of trained teachers and low teacher-to-pupil ratios, and deterioration of conditions in SAEC in favor of schools in terms of resources and the utilization of premises. It also notes a shift in responsibility for SAEC operations from the governing body to the principal, who in turn delegates responsibility to teachers and other staff. A consequence of this is a gap between the overall responsibility for the SAEC conditions in terms of premises and resources and teachers’ responsibility for teaching. Inadequate conditions inevitably impair SAEC quality and their ability to fulfill their mission (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023a). The Swedish Schools Inspectorate’s review of SAEC quality (2018) also reveals that principals are not sufficiently striving to clearly steer, set goals, and follow up on teaching in SAEC. The review also shows that the teaching in SAEC tends to be marginalized in schools’ systematic quality work. Accordingly, a recent assessment by the Swedish National Agency for Education (2023a) recognizes needs to increase the quality of teaching in SAEC and its inclusion in the schools’ systematic quality work.

2.2 The context of Swedish school-age educare, SAEC

SAEC has been included in the national educational organization since the mid-1990s, and it has had its own part in the national curriculum for compulsory school since 2016 (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2016). SAEC is offered to all Swedish children between 6 and 12 years old. It is not compulsory, but about 57 percent of the cohort (about 500,000) are currently enrolled (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2024). SAEC has two main purposes: to provide care and meaningful activities before and after compulsory school days, and to offer teaching and learning in line with the curricular aims (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2022). Recent increases in societal divisions have also raised the importance of this educational practice for mitigating social exclusion and inequalities. However, despite the urgently required and emphasized societal function, several reports have found that the quality of SAEC practices is frequently low (Swedish School Inspectorate, 2010, 2018; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023a). Noted quality shortcomings in these reports include deficiencies in offering stimulating and meaningful leisure as well as good care. SAEC facilities may be regarded as lacking quality if they do not provide satisfactory conditions, and/or set goals or definitions of quality and anticipated results. Moreover, reports have consistently found increases in numbers of pupils, leading to increasingly large pupil groups and reductions in staff density. Further noted obstacles to good quality SAEC include deficiencies in premises’ design and school leaders’ developmental competence. According to the Swedish School Inspectorate (2010), leaders in more than half of the reviewed schools need more knowledge of the SAEC mission to enhance development of the practice. Similarly, the Swedish National Agency for Education’s latest assessment of the Swedish school system (2023a) found that school leaders of several reviewed SAEC providers put little effort into setting goals, and both managing and following-up results. It highlights that the teaching in SAEC has low prioritization in the schools’ systematic quality work. The finding that SAEC practices lack the quality needed to provide good care and meaningful activities for children and youths, in accordance with the stated mission, is clearly problematic. Moreover, this is exacerbated by lack of clarity regarding the definition of quality in informal settings, who should define, why it requires definition, and how current educational discourses on quality affect educational practices like SAEC.

2.3 Research perspectives on quality in Swedish SAEC

The inclusion of SAEC in the Swedish national curriculum (see part four) introduced in 2016, contributed to an increase in its legitimacy. However, the chances for staff to realize the curriculum in SAEC practice are strongly influenced by frame factors, such as organizational elements, the time allocated for shared planning, access to dedicated premises, and involvement of staff with a university degree in education (Norqvist, 2022). For example, some SAEC staff have reported that the curricular text contributed to discussion about quality in terms of the content and pedagogical approach of the practice (Norqvist, 2022), but the mentioned frame factors inevitably affect the social relations and opportunities that can be provided in everyday practice within SAEC (Lager, 2020). Quality audits have focused on opportunities in SAEC to promote pupils’ learning and development, in accordance with key elements as described in part four of the curriculum. According to Andersson (2020), this is a manifestation of an educational discourse on quality in SAEC that raises questions about whether teachers involved in SAEC should assess children individually, in stark contrast to previous group- or setting-based quality assessments (Andersson, 2010, 2013). It has also been found that tensions arise when more structured and individualized approaches to quality are introduced into traditional SAEC (Lager et al., 2015). Variations in, and effects of, settings and the times of activities add further complexities (Lager, 2015). Lager (2015) also found that although compulsory schools’ quality work may provide a template for the conduct of quality work in SAEC, the social pedagogical discourse of SAEC was still prominent. Further, the staff engaged in SAEC may adapt their work to an implemented template for systematic quality work, which can lead to complications when a quality system is introduced into practice grounded in a social pedagogical tradition (Andersson, 2013, 2020; Lager, 2015). Two contrasting ways of handling such changes have been identified. Some SAEC providers seem to have carried on as before, at least temporarily, despite the introduction of new curricular demands (Boström and Berg, 2018), while others seem to have abandoned the traditional features of SAEC in favor of more school-like practices (Memišević, 2024). Moreover, researchers have noted a shift in the prevailing discourse, from warnings about changes in the mission and conditions of SEAC (particularly threats to the social, restorative and recreational functions) toward fulfillment of the schools’ curricular goals (Memišević, 2024). This has been reportedly accompanied by clashes between the traditional group-orientation in SAEC and school discourse (e.g., Andersson, 2013, 2020; Lager, 2015; Memišević, 2024). A Swedish practice-based study has also found that quality in SAEC is connected to several knowledge interests, and introduced the concepts technical, practical and liberating quality (Kane, 2023). Technical quality refers to doing the ‘right thing’ in relation to the curricular assignment and difficulties linked to voluntariness and individual assessment of pupils’ goal fulfillment since it presupposes control of participation and assessment. Practical quality includes collegial sense-making in attempts to transform curricular text into everyday practice in SAEC. Liberating quality is largely about collegial reflections focused on problematizing norms and limitations with the aim to improve activities for both pupils and staff. It involves planning and designing practice with responsiveness and curiosity in line with the interests, needs and experiences of the children, as expressed by the children themselves (Kane, 2023).

2.4 Principals’ responsibility for quality in Swedish SAEC

Quality in SAEC is a complex concept (see Andersson, 2013; Lager, 2015), which is rarely applied in a manner that is fully congruent with a practice rooted in social pedagogical traditions. Principals are the instructional leaders in SAEC facilities, and responsible for the educational quality within them. General advice of the Swedish National Agency for Education (2023b) highlights the importance of the principal’s knowledge of the SAEC assignment. The principal can also provide support and guidance for development of the practice through follow-up and evaluation of the goals linked to its purpose (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023b). However, studies indicate that principals often lead SAECs with a more distanced leadership rather than as educational leaders (Glaés-Coutts, 2021), which may be related to what was mentioned earlier about many leaders needing more knowledge about the SAEC’s mission (Swedish School Inspectorate, 2010). This limits the development of educational quality in SAECs as they only relate quality to the educational level of the staff rather than the development of practice, and there is a need to apply structural quality criteria to the pedagogical work in SAECs (Andersson, 2020). This makes it complex as SAEC practice mainly involves learning in informal situations that are intended to promote social inclusion and wellbeing, which are difficult to document, monitor and evaluate (Andersson, 2013). There is a need to examine this issue with more empirical research. In summary, the issue of educational quality in extended education in general, and in SAEC in particular, is highly complex and difficult to interpret, as quality in SAEC is multifaceted and influenced by diverse factors, encompassing (for example) the suitability of premises, teachers’ training, and available time for planning (e.g., Lager, 2020; Norqvist, 2022). Moreover, schools’ measurement of quality and the applied definition of quality inevitably influence SAEC norms and practices (e.g., Andersson, 2013, 2020; Lager, 2015). National and international education trends toward more formal and measurable definitions of quality rooted in a knowledge-oriented paradigm pose threats to socially oriented SAEC (e.g., Biesta, 2014; Lager, 2015; Löfdahl and Pérez Prieto, 2009; Löfgren, 2016). Aspects of quality within extended education seems thus to be an area open for varied definitions and implementations, why a study like this could contribute with more knowledge on school leaders’ perspectives on the issue.

3 Theoretical perspectives

Theoretically, this study is based on two theoretical positions—Bernstein (2000, 2003) theory of pedagogical code as adapted by Norqvist (2022) and a model of school improvement by Scherp and Scherp (2007). The classification, framing and pedagogical code concepts and associated theory of Bernstein (2000, 2003) was used to facilitate analysis of the principles and norms that inform the organization, content, communication, and relations in pedagogic practice (Bernstein, 2000). This theory is valuable for illuminating power relations and control mechanisms between various ‘categories’, for example, relations or boundaries between categories such as agencies, agents, discourses, and practices (Bernstein, 2000). Classification refers to the strength of separation between curricular categories, content, or subject matter. Framing refers to the control that teachers and students have over the selection, organization, pacing and timing of knowledge transmission. Pedagogic code refers to the way that knowledge is classified and framed (Bernstein, 2000, 2003). In the present study, pedagogical codes identified by Norqvist (2022), i.e., educational-pedagogical code, social-pedagogical code, and leisure-pedagogical code, will be utilized in the analysis (see also section 4.2). The organizational theories of schools, particularly the model of school improvement presented by Scherp and Scherp (2007) has four inter-related dimensions that influence the success or failure of developmental work. The four dimensions are holistic idea, routines and structures, professional knowledge creation, and pedagogical practice. A holistic idea (that is ideas about the practice and its purpose) as a common understanding within a school organization has proven to be the most important factor for successful school development (Mogren, 2019). Routines and structures that support the common goal is also vital for a successful educational practice, as well as the possibilities of teachers’ professional knowledge creation. What then turns out as a reality in the pedagogical practice could be understood in relation to the other dimensions (Scherp and Scherp, 2007). This model has proven value for analyzing educational practices to identify aspects that are strong and explicitly addressed or weak and implicitly rather than explicitly addressed, which hinders improvement (Manni and Knekta, 2022; Manni et al., 2024). Combining these two perspectives contributes to understanding our case on educational quality in a more comprehensive way including norms as well as structures.

4 Methods

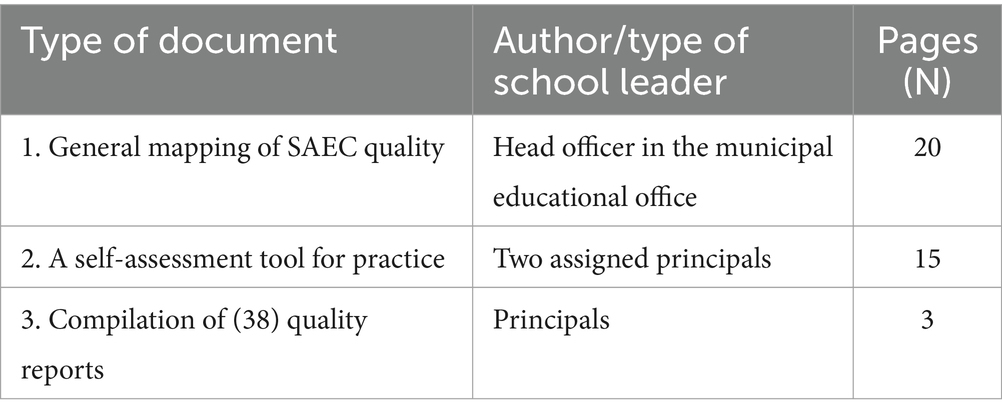

This study is based on documentary sources. Three significant educational documents from a single municipality in Sweden, were analyzed according to methods described by Scott (1990). In accordance with the aim of the study, the focus was on parts of these documents that provided indications of municipality-level actors’ interpretation, definition and communication of quality in SAEC. As described in the background section, quality in extended education is complex and has not been in focus of many municipalities school developmental work in the past. Therefore, documentation of this kind is sparsely found, why this study is somewhat unique.

4.1 Data selection and sampling

The documents were sourced through a collaborative partnership between the municipality and the researchers’ host university and are the only three documents specifically focusing on quality in SAEC in this municipality. This opportunity facilitated practically oriented and critical examination of SAEC quality. The selected documents (see Table 1) were deemed to meet the four criteria (authenticity, credibility, representativeness, and meaning) for appropriate sources of data in documentary research suggested by Scott (1990, p. 19). Confirming the authenticity of many documents, particularly old ones, can be difficult or even impossible. However, the documents selected for this study were deemed to have high authenticity because they were recent, and the researchers had collaborated with the authors of the documents. Regarding credibility, “all accounts of social events are of course ‘distorted’, as there is always an element of selective accentuation in the attempt to describe social reality” (Scott, 1990, p. 22). Credibility is a matter of sincerity, that is, the degree that authors of documents believed what they recorded. In this research it is considered that all the authors to believe what they recorded in each document, so despite their inevitable selectivity the researchers regard them as providing highly credible foundations for the analysis of quality in SAEC and its definitions. Representativeness refers to the degree that the chosen documents represent “the totality of relevant documents” (Scott, 1990, p. 24), and thus the possibility of basing valid generalizations on them. Other aspects of this criterion are whether the documents will survive and be available for future scrutiny. The documents used in this study will remain available because they are official documents that will be preserved in municipal archives. Assessment of the degree that they represent all relevant documents is more difficult. There is a strong possibility that similar types of documents are present in archives of other Swedish municipalities, based on the researchers’ knowledge of educational structures. There are no claims of that the findings of this study are generalizable; however, these forms of document are potentially found in other municipalities. The researchers regard them as trustworthy indications of views meaning refers to the legibility, clarity and ease of interpreting documents. All three documents used are easy to read, written in clear and modern language, and easy to understand, at least for anyone such as researchers with knowledge of the SAEC context. In summary, all the analyzed documents stem from one municipality, concerned aspects of quality in its SAEC practice. They were produced by school leaders such as head officers and principals with positions at three levels in the hierarchical organization of municipal education. One document was 20-page mapping of the physical framings of the practice to be used by the municipality’s head of education. Another document was a self-assessment tool for teachers to evaluate quality-related aspects of SAEC, produced by two assigned principals. The other document was a compilation of quality reports written by principals of all schools in the municipality.

4.2 Analytical process

Analysis of the three text documents started with repeated readings before an inductive step, in which each text was coded based upon its content and wording. After the initial coding procedure, the documents were analyzed deductively to identify pedagogical codes (Bernstein, 2000, 2003). These included three codes—designated the educational-pedagogical, social-pedagogical, and leisure-pedagogical codes identified in a previous study on extended education (Norqvist, 2022). The educational-pedagogical code referred to concepts with a stronger classification and stronger framing (for example, teaching or focus on the knowledge goals of school). Hence, the educational-pedagogical code was assigned to text indicating that school-age educare is goal-oriented and focused on the pupils’ goal achievement in compulsory school. The two other codes, social-pedagogical, and leisure-pedagogical code are characterized by a weaker classification and weaker framing. The social-pedagogical code represents concepts that indicate work with social relations and care in SAEC. The leisure-pedagogical code regards concepts of the SAEC teaching, which involves situation-based and group-oriented play and teaching centered on pupils’ needs, interests and experience (Norqvist, 2022). The text in each of the three documents was color-coded according to these descriptions. Memos were scribbled in the margin when a wording expressed something that could not be assigned to one of these predefined pedagogic codes.

4.3 Validity and reliability

Following the documentary analysis process described by Scott (1990) the researchers aimed to maximize the study’s trustworthiness in terms of internal validity (through all authors and municipal participants discussing the results) and reliability (by providing accurate contextual descriptions and quotations from the documents).

4.4 Ethical considerations

None of the documentary sources are ethically sensitive as they are formal educational policy documents produced in a single municipality. The school leaders who authored them were participants in a co-operative project and were informed about the research study and participated voluntarily (Swedish Research Council, 2024). Open and respectful occurred in all stages of the research, giving the participants opportunities to discuss the findings throughout the process and in a final meeting (i.e., Manni and Löfgren, 2022). This rigor supported the validity of the findings.

5 Results—definitions and codes regarding quality in SAEC in the three municipal documents

The results section consecutively provides a contextual description of each of the selected documents to establish its authenticity (Scott, 1990) and increase the qualitative depth, as commonly done in document-based case studies (Flyvbjerg, 2011), see 5.1.1, 5.2.1, and 5.3.1. The definitions of quality and pedagogical codes identified in each document are also presented, see 5.1.2, 5.2.2, and 5.3.2. Finally, in section 5.4, we present results of a comparative analysis of the documents in terms of the similarities and differences in definitions and pedagogical codes related to quality, and their relations to school leaders at different municipal levels.

5.1 The general mapping of SAEC quality

5.1.1 Contextual description of the document

This document (Municipality, 2021a) partly originated from a desire of the municipal board of educational politicians to obtain an overview of the uses of economic resources in all the municipality’s SAEC centers, and how the practice was organized in relation to the national curriculum. The mapping was also partly inspired by signals of problems within SAEC identified in previous joint assessments of schools and SAEC centers, which raised awareness of needs for higher-resolution knowledge of the practices. The author of this document was a school leader with in the municipal educational office. The author was a Head Officer and one of his tasks was to monitor developmental work within all schools, and to implement policies expressed by the Lead Officer of Education and the Educational Board. The main quality-related content of this document concerns economic and formal aspects of quality, as well as deficiencies and needs of the municipality’s SAEC centers identified by the mapping. The main proposals for enhancing quality include establishment of a developmental manager for SAEC centers and following up of the distribution of personnel costs between school and SAEC. It also proposes three further measures:

• Development of competence regarding the curricular aim of the SAEC among principals and key personnel of all the municipality’s SAEC-centers.

• Creation of guidance for principals regarding group sizes, appropriate premises and collaboration to clarify appropriate positions, roles and responsibilities in the SAEC centers in the future.

• Development of the skills needed to ensure that the municipality has competent staff in the SAEC practice (Municipality, 2021a, p. 19–20).

5.1.2 Definitions of quality and pedagogical codes

The general mapping document is permeated by consistently strong classification and strong overall framing. This is manifested in formulations such as “[the SAEC] is more curriculum-oriented and structured than before, as manifested by clearer work with the pupils’ goal achievement” (Municipality, 2021a, p. 7). Quality on this general municipality level focuses largely on frame factors related to formal quality and economic aspects that we interpret as elements of a new (educational-economic) type of pedagogical code. Examples include changes in the way that SAEC is organized, the occupational categories that should be engaged in SAEC, and the service and budgetary allocations to support the principals’ distribution of personnel and funds. This definition of quality could also be understood as what Scherp and Scherp (2007) frame as a dimension of routines and structures within the school organization. In the general mapping, the SAEC practice is to a large extent linked to the compulsory school and the text is consistently informed by an educational-pedagogical code which emerged by wording such as that the school-age educare practice now “is more curriculum oriented and structured than before” (Municipality, 2021a, p. 7), and this manifests by “a clearer work with the pupils goal achievement in the school-age educare” (Municipality, 2021a, p. 7). These expressions assigned to the educational-pedagogical code are mixed with short passages assigned to the leisure-pedagogical code, stating for example that school-age educare practice should “seize the learning opportunities” (Municipality, 2021a, p. 7). Occasionally the social- pedagogical code emerges in references to relationships that are considered key elements of “all teaching and the mission of school-age educare, which includes care, learning and development” (Municipality, 2021a, p. 11). The document includes suggestions for targeted changes focusing on frame factors, such as directions for group size, purposive premises, and development of relevant competence of principals and key personnel in all the municipality’s SAEC centers. It also recommends clarification of the optimal positions, roles and responsibilities of staff engaged in SAEC and a review of the needs for development of their competence in the whole municipality.

5.2 A self-assessment tool for practice

5.2.1 Contextual description of the document

This document (Municipality, 2021b) was commissioned following the general mapping of the SAEC centers and its call for development of competence about the curricular aim of the SAEC for principals and key personnel of all SAEC centers in the municipality. The authors were two principals who were assigned the task of supporting such competence development. The main content of this document is of a practical nature, consisting of questions designed to elicit the views of teachers and other staff on what, how and why they teach and work as they do in their respective SAEC centers. In accordance with the curriculum, it focuses particularly on the complementary task of SAEC and thus has an educational emphasis. A similar self-assessment tool is used in compulsory school; however, the content of this tool is based on the SAEC part of the curriculum.

5.2.2 Definition of quality and pedagogical codes

The self-assessment tool is based on formulations in the SAEC part of the curriculum. It focuses on teaching in SAEC practice, particularly the staff’s pedagogical approach, both individually and within the team of colleagues. This document thus focuses what Scherp and Scherp (2007) calls a dimension of professional knowledge creation, and the pedagogical practice, while it clearly does not include any dimensions of routines or structures. It generally has weak classification as it does not set clear boundaries between any categories, however the framing is slightly stronger as some of the text indicates that pupils can influence the practice to some extent in high quality SAEC. The self-assessment tool was developed to facilitate analyses of teaching quality in SAEC. Accordingly, large parts of the document are characterized by leisure-pedagogical, social-pedagogical, and educational-pedagogical codes, with emphasis on the part of SAEC’s mission to complement compulsory schooling. These codes emerged under the headings learning environment, adaptation, and structure, since the formulations derive from the SAEC part of the curriculum (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2022). Examples of the leisure-pedagogical code include self-assessment items, such as “in our practice there is room for situation-driven and experience-based activities” (Municipality, 2021b, p. 7). Examples of the social-pedagogical code include formulations that chime with the social relations and care elements of SAEC, such as “we build relationships with the pupils and make pupils feel part of the group community” (Municipality, 2021b, p. 5). The self-assessment tool has the same structure as the tool for compulsory schools mentioned above. A consequence of this is that some of the self-assessment items have the character of an educational-pedagogical code, e.g., “we have high expectations on all pupils” (Municipality, 2021b, p. 5). This formulation is complex as it implies that placing high demands on pupils is desirable, but the expectations may be unattainable for some pupils.

5.3 The compilation of quality reports

5.3.1 Contextual description of the document

This document (Municipality, 2022) presents a compilation and analysis of 38 of the municipality’s 45 quality reports for compulsory schools (including SAEC practice). Quality reports are prepared annually as part of the focal municipality’s routines. The authors of the compilation document were the two principals assigned to work with quality development in SAEC. The compilation is based on individual principals’ quality reports for their respective schools. The main content of this document concerns the schools’ goals for the previous year, the current year’s results, identified successes and aspects requiring development as well as future goals. Of the 38 schools that submitted a quality report, only 23 reported specific results for the SAEC activities. A pupil questionnaire had provided foundations for 22 of the schools’ quality reports of, but only two had used the self- assessment tool in parallel with the pupil questionnaire. The analysis shows that most of the results reported by the municipality’s SAEC centers were based on the goals set by the schools and overall goals linked to the curriculum. However, 14 of the reports address goals specifically linked to SAEC practice, eight of these mainly report efforts related to furnishings and production of play boxes, and six of the SAEC center’s reportedly goals had related to safety and values. Furthermore, five had goals related to adaptations in the physical environment intended to support groups or individuals.

5.3.2 Definitions of quality and pedagogical codes

In the compilation of quality reports there are signs of a weaker classification since few of the municipality’s school’s quality reports explicitly concern the quality in SAEC, and weak framing since pupils’ influence in the practice is highlighted as a sign of success. The document strongly focuses on frame factors, such as funding, and the content of the SAEC practice, indicating acknowledgement of the importance of both formal and informal quality aspects. However, a low proportion of the results explicitly concern the practice in SAEC. Some formulations highlight a need for consensus between different groups of professionals within the organization and the importance of both collaboration and a common understanding of the SAEC mission. The focus on frame factors is manifested in formulations that stress the importance, for example, of “joint time for planning the practice for the staff in school-age educare, good organizational structures in both organization and practice” (Municipality, 2022, p. 1). The leisure-pedagogical code also emerges, in formulations such as “Making pupils involved in the practice, and pedagogues’ relational competence are also factors for success” (Municipality, 2022, p. 1). In addition, the compilation of quality reports includes some results of a survey of the views of the municipality’s pupils and proposed measures based on their views for SAEC staff to adjust the content of the practice and their approach. However, the problems highlighted in the pupils’ survey are largely related to the frame factors and hence difficult to change through such adjustments. Analyzing the definition of quality in this document through the school organization lens of Scherp and Scherp (2007), we again notice a focus on the dimension of routines and structures, but also on the professional knowledge creation in terms of collegial dialogs. A few comments reveal a need for a common understanding of the SAEC mission, i.e., a holistic idea (Scherp and Scherp, 2007).

5.4 Comparison of the documents and their pedagogical codes defining quality in SAEC

5.4.1 Initial reflections

Comparison of the three documents and their codes defining quality in SAEC led to the following reflections:

First, the three documents from a single municipality present different dimensions and definitions of quality in SAEC, which do not seem to have been explicitly discussed. Second, quality is defined and largely related to economic and frame factors such as routines and structures in both the general mapping document and compilation of quality reports, but these aspects are not mentioned in the self-assessment tool for teachers. Third, there are indications in both the general mapping and compilation of quality reports of expectations that identified economic and organizational shortcomings will be addressed by changes in practice and approaches of the staff within the SAEC centers. Fourth, use of the self-assessment tool was not mandatory, and results obtained with it were not compiled to provide clearer foundations for the pedagogical developmental efforts within the municipality. Similarly, the compilation of quality reports shows that some schools did not include SAEC in their annual educational assessments and quality reports. Finally, the pedagogical codes we identified were not solely leisure-pedagogical and social-pedagogical. Instead, as further addressed below, both an educational-pedagogical code and the new educational- economic code influenced the definition of quality in SAEC in the focal municipality.

5.4.2 Pedagogical codes and power structures between different levels of school leaders

Deeper analysis of the three documents revealed that the educational-pedagogical code dominated, and both the leisure-pedagogical and social-pedagogical codes only appear sporadically. In addition, a new ‘educational-economic’ pedagogical code emerged during analysis of the general mapping document, as it includes formulations indicating that quality can be addressed by economic actions. The analyzed documents, which were created by school leaders at different levels of the municipality organization, revealed power structures between different levels of school leaders. This is normal for hierarchical school organizations, but it can complicate collaboration, for example, a Head of education must both respond to demands from the educational politicians and help principals to develop the quality of SAEC practice in their centers. Dilemmas associated with power structures are further illustrated by the self-assessment tool (developed by two assigned principals) solely focusing on the staffs’ pedagogical approaches and neglecting the higher-level frame and economic factors, which also strongly affects the quality in SAEC practice.

6 Discussion

This research reveals how quality in SAEC was defined and formulated by school leaders from several levels in a Swedish municipality, and the pedagogical codes embedded in documents concerning quality, and implications of their definitions, assessments and recommendations for SAEC practices were exposed. Although, by analyzing these national findings with general theories on policy, power and school organizations we argue that the results could be of common value. An overall reflection is that despite shared ambitions to increase the quality in SAEC there are clear variations in the assumptions regarding definitions of quality, and clear challenges to overcome. Different definitions of quality are embedded in the three studied municipal documents. In terms of the school improvement model, with the four interrelating dimensions (Scherp and Scherp, 2007) this clearly indicates a lack of a joint understanding or a shared holistic idea of quality in extended educational practices (Mogren, 2019). In accordance with Manni and Knekta (2022) such ambiguities should be explicitly discussed in practice. Also noted was a correlation between the authors’ hierarchical positions in the school organization and definitions of educational quality, with high positions being linked to formal, structural, and economic definitions of quality, and closeness to practice linked to more social-pedagogical approaches. In terms of the cited school improvement model, two documents focus on routines and structures, while the other focuses on pedagogical knowledge. This may not be surprising, given the differences in school leaders’ responsibilities (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023b), however the apparent lack of awareness of the variation among the relevant actors involved could clearly hinder efforts to improve SAEC quality.

Regarding the results revealing pedagogical codes (Bernstein, 2000, 2003; Bernstein, 2000), we think the most interesting is the identification of a previously unrecognized code, which we call the educational- economic code. This helped the researchers to deepen the analysis of principles and norms that inform the municipality organization and relations in the pedagogical practice of SAEC When this code was identified it illuminated findings with clarity. Together with the three codes (educational- pedagogical, leisure-pedagogical, and social-pedagogical) identified in a previous study (Norqvist, 2022) analysis of aspects of quality work emphasized in textual documents and the complexity of quality in SAEC, which has been problematized in previous research (e.g., Andersson, 2013, 2020; Lager, 2015) was evident. For example, it illuminates more clearly how schools’ approaches to quality have often served as templates for practices rooted in a social pedagogical tradition such as preschool and SAEC (Lager, 2015). A consequence is that informal aspects of quality are frequently overshadowed by more formal quality aspects or performative aspects that are easier to measure (e.g., Biesta, 2014; Löfdahl and Pérez Prieto, 2009; Löfgren, 2016; Moss, 2017). This also increases the risk of extended educational practices becoming more like those of schools rather than continuing the social and leisure pedagogical traditions (Memišević, 2024). The result also raises questions about the responsibilities of school leaders, particularly principals, in matters of complex and integrated educational practices, such as extended education (Glaés-Coutts, 2021). The main problems identified regarding good and equal quality were connected to staff shortages, large groups of pupils, and adequate classrooms, none of which can be addressed without good financial support (Lager, 2020; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023a). Similar results and conclusions regarding the financial aspect of educational quality and school leadership were also found in previous international research (Fischer et al., 2022; Hallinger, 2003; Kielblock, 2025). The identification of an educational-economic code can also be related to the fact that current educational leadership are to handle economic efficiency alongside pedagogical issues, and some argue that entrepreneurial leadership can be beneficial for developing the educational practice (Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz and Pashiardis, 2022). We thus argue that interventions by relevant politicians, together with school leaders or teachers are needed to solve the economic challenges. Furthermore, leaders of specific schools can pay attention to the four dimensions of school improvement presented by Scherp and Scherp (2007) and strive (for example) to ensure that the whole staff in their schools discuss quality and establish shared understandings and definitions of quality to maintain a coherent approach. Similarly, leaders on higher levels in the school organization should strive to develop a shared understanding among the school leaders. This can avoid some problems, however good will and pedagogical efforts are not sufficient to overcome problems associated with inadequate funding or deficiencies in other resources. Results of this study also highlight surprisingly weak attention to children’s well-being and care in the definitions of good quality in SAEC. We also found a surprising, and problematic, apparent optionality in implementation of some of the municipality’s structural recommendations for quality control in our study, which we relate to a general and problematic issue of extended education practices nation-wide (Biesta, 2009: Moss, 2017).

7 Final conclusions

Through this study, questions are raised about relying on the more quantitative and measurable aspects in definitions of quality in extended educational practices. Practical and economic aspects, such as available facilities and numbers of pupils are clearly essential for comparing educational conditions and efforts to ensure equality in care-oriented, as well as education-oriented practices. However, it is still important to consider qualitative aspects of quality in extended education, such as SAEC, since they include educational values, teaching approaches, as well as individuals’ experiences and meaning making of practice. Since this was a rather small-scale and national study, we recommend for further, and international, research that involves a collaborative understanding of quality in line with Kane’s (2023) concept of liberating quality including collegial reflections. Further inclusion of attention to children’s and pupils’ voices, when considering quality in extended education, and holistic efforts of school leaders (cf. Manni et al., 2024; Scherp and Scherp, 2007) to address the full multi-dimensionality of this educational practice should be required. Quality in extended education is a complex concept; however, it demands attention to ensure that extended education provides children with valuable opportunities that are not only based on structural or economical aspects.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andersson, B. (2010). Introducing assessment into Swedish leisure-time centres -pedagogues' attitudes and practices. Educ. Inq. 1, 197–209. doi: 10.3402/edui.v1i3.21942

Andersson, B. (2013). Nya fritidspedagoger - i spänningsfältet mellan tradition och nya styrformer. Department of applied educational science. [Doctoral dissertation] Umeå University.

Andersson, B. (2020). “Fritidshemmets utveckling ur ett styrningsperspektiv” in Fritidshemmets pedagogik i en ny tid. eds. B. Haglund, J. Gustafsson Nyckel, and K. Lager (Malmö: Gleerups), 35–58.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique. Rev. Edn. Landham Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Bernstein, B. (2003). “Class, codes and control” in Towards a theory of educational transmission, vol. 3 (London: Routledge).

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educ. Assessment Evaluation 21, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

Boström, L., and Berg, G. (2018). Läroplansimplementering och korstryck i fritidshemmets arbete. Educare - Vetenskapliga Skrifter 2, 107–131. doi: 10.24834/educare.2018.2.6

Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz, S., and Pashiardis, P. (2022). Entrepreneurial leadership in schools: linking creativity with accountability. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 25, 787–801. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2020.1804624

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., and Pence, A. R. (2007). Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Languages of evaluation. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., and Pachan, M. (2010). A Meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 45, 294–309. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

Fischer, N., Elvstrand, H., and Stahl, L. (2022). Promoting quality of extended education at primary schools in Sweden and Germany: a comparison of guidelines and children’s perspectives. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung 15, 273–289. doi: 10.1007/s42278-022-00148-9

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). “Case study” in The sage handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 301–316.

Glaés-Coutts, L. (2021). The principal as the instructional leader in school-age educare. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 22, 873–889. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2021.2019792

Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Camb. J. Educ. 33, 329–352. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000122005

Kane, E. (2023). Teknisk, praktisk och frigörande kvalitet I fritidshemmets systematiska kvalitetsarbete. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 28, 117–141. doi: 10.15626/pfs28.04.05

Kielblock, S. (2025). Rethinking leadership in extended education: how collaborative development drives organizational quality. Front. Educ. (Lausanne) 10, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1545842

Klerfelt, A., Haglund, B., Andersson, B., and Kane, E. (2020). “Swedish school-age educare: a combination of education and care” in International developments in research on extended education. eds. J. L. M. S. H. Bae, S. Maschke, and L. Stecher (Leverkusen – Opladen: Barbara Budrich), 173–192.

Klerfelt, A., and Ljusberg, A.-L. (2018). Eliciting concepts in the field of extended education. A Swedish provoke. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ.: IJREE 6, 122–131. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i2.03

Klerfelt, A., and Stecher, L. (2018). Swedish school-age Educare Centres and German all-day schools: a bi-National Comparison of two prototypes of extended education. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 6, 49–65. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i1.05

Lager, K. (2015). I spänningsfältet mellan kontroll och utveckling: en policystudie av systematiskt kvalitetsarbete i kommunen, förskolan och fritidshemmet. (Gothenburg studies in Educational Sciences, 379) [Doctoral dissertation] Gothenburg University.

Lager, K. (2020). Possibilities and impossibilities for everyday life: institutional spaces in school-age educare. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 8, 22–35. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v8i1.03

Lager, K., Sheridan, S., and Gustafsson, J. (2015). Systematic quality development work in a Swedish leisure-time Centre. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 60, 694–708. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2015.1066434

Löfdahl, A., and Pérez Prieto, H. (2009). Between control and resistance: planning and evaluation texts in the Swedish preschool. J. Educ. Policy 24, 393–408. doi: 10.1080/02680930902759548

Löfgren, H. (2016). A noisy silence about care: Swedish preschool teachers’ talk about documentation. Early years 36, 4–16. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2015.1062744

Manni, A., and Knekta, E. (2022). Fritidshemmet - en förbisedd potential i arbetet med lärande för hållbar utveckling? Nordina: Nordic Stud. Sci. Educ. 18, 63–81. doi: 10.5617/NORDINA.8481

Manni, A., Knekta, E., and Åberg, E. (2024). “Critical events in the systematic work at an organizational level towards a whole school approach to sustainability in a Swedish municipality” in Whole school approaches to sustainability: Education renewal in times of distress. eds. A. E. J. Wals, B. Bjønness, A. Sinnes, and I. Eikeland (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 201–213.

Manni, A., and Löfgren, H. (2022). Methodological development through critical reflections on a study focusing on daily valuable encounters in early childhood settings. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 25, 383–396. doi: 10.1177/14639491221129192

Memišević, A. (2024). Det undervisande fritidshemmet i lärandets tidevarv: en diskursanalytisk studie med fokus på de naturvetenskapliga och tekniska undervisningspraktikerna. Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning. [Doctoral dissertation] Linköping University.

Mogren, A. (2019). Guiding principles of transformative education for sustainable development in local school organisations: investigating whole school approaches through a school improvement lens. The Faculty of Health, Science, and technology [doctoral dissertation] Karlstad university.

Moss, P. (2017). Power and resistance in early childhood education: from dominant discourse to democratic experimentalism. J. Pedagogy. 8, 11–32. doi: 10.1515/jped-2017-0001

Norqvist, M. (2022). Fritidshemmets läroplan under förhandling: Formulering, tolkning och realisering av del fyra i Lgr 11. Department of applied educational science. [Doctoral dissertation] Umeå University.

Scherp, H.-Å., and Scherp, G.-B. (2007). Lärande och skolutveckling: ledarskap för demokrati och meningsskapande. Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten: Pedagogik, Karlstad University.

Schuepbach, M. (2015). Effects of extracurricular activities and their quality on primary school-age students' achievement in mathematics in Switzerland. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 26, 279–295. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.929153

Swedish National Agency for Education (2016). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare 2011: Reviced 2016. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2022). Curriculum for Cumpulsory school, preschool class and school-age Educare – Lgr22. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2023a). Skolverkets bedömning av läget i skolväsendet 2023. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2023b). Styrning och ledning av fritidshemmet. Kommentarer till Skolverkets allmänna råd om styrning och ledning av fritidshemmet. Sweden: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2024). Elever och personal i fritidshem. Läsåret 2023/24. Sweden: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish School Inspectorate (2018). Undervisning i fritidshemmet inom områdena språk och kommunikation samt natur och samhälle. Sweden: Swedish Research Council.

Keywords: extended education, educational quality, school leaders, school-age educare, case study

Citation: Manni A, Norqvist M and Yttergren S (2025) Identifying an educational-economic code of quality in definitions of extended education: an example from school leaders in Sweden. Front. Educ. 10:1531438. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1531438

Edited by:

Jennifer Cartmel, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Patricia Schuler, Zurich University of Teacher Education, SwitzerlandHaiqin Ning, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Manni, Norqvist and Yttergren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Annika Manni, YW5uaWthLm1hbm5pQHVtdS5zZQ==

Annika Manni

Annika Manni Maria Norqvist

Maria Norqvist Susanne Yttergren

Susanne Yttergren