- Department of Education Studies, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

The goal of this paper is to present, conceptually and empirically, a framing for inclusion grounded in the social network perspective: Relational Inclusivity (RI). This approach emphasizes the importance of interdependent student relationships that educators must attend to in order to create socially responsive learning communities. We center relational ties and dynamics across four social dimensions experienced by students: friendships, recess, academic support, and emotional connection networks. Using data from a Grade 7 class collected through the Social Network Analysis (SNA) Toolkit, we illustrate how student experiences vary across these four dimensions and how educators may attend to them. We argue that an RI approach necessarily shifts attention away from traditional individualized paradigms of achievement and towards the social dynamics of learning environments.

Introduction

Despite the noble intentions and continued efforts around the world to achieve full inclusion of students identified as having Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), there remain major concerns about these students’ social relationships and engagement with peers. Since the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994), inclusion has primarily been defined as a sense of social acceptance and an approach where physical placement in a general education classroom (“mainstreaming”) can lead to enhanced social participation outcomes for Students with SEND (Lüddeckens, 2021). However, even though a number of studies found that inclusion may generate social and academic benefits for Students with SEND (De Bruin, 2020; Frederickson et al., 2004; Hanushek et al., 2009; Lindsay, 2007; Mamas et al., 2023), some findings about these students’ social participation are alarming. In general, students identified as having SEND have been found to experience challenges engaging with others (Bossaert et al., 2015; Koster et al., 2009, 2010; Mamas et al., 2021; Zurbriggen et al., 2021), have fewer friends and social interactions than their peers (Avramidis, 2013; Koster et al., 2010; Mamas et al., 2020; Schwab et al., 2021), are less popular, less accepted and remain on the periphery of their classroom’s social networks (Kasari et al., 2011; Mamas, 2013; Schwab et al., 2019), are more lonely and maintain a lower sense of belonging and wellbeing (Heiman and Olenik-Shemesh, 2020; Kwan et al., 2020; Prince and Hadwin, 2013; Woodgate et al., 2020), and, in some cases, experience bullying, social isolation and marginalization (Humphrey and Symes, 2011; Qi and Ha, 2012; Van Mieghem et al., 2020; Woodgate et al., 2020). In other words, inclusion that places students with SEND in proximity to students in the general education environment does not necessarily result in a shift in the beliefs, attitudes, behaviors and practices of students or teachers. While this discussion focuses on students with SEND, these challenges of social integration and participation extend beyond this group, affecting other marginalized students as well. A broader understanding of relational inclusivity can therefore inform strategies that benefit all students, regardless of their specific educational needs.

Thus, despite the many benefits that inclusive education may generate for Students with SEND and their peers, it is clear that there is much more systematic pedagogical work that has to be done to support authentic inclusion in schools. Broadly defined as a multidimensional concept encompassing friendships/relationships, contacts/interactions, students’ social self-perception, and acceptance by peers (Koster et al., 2009), social participation is a core way that inclusion is conceptualized in academic literature on inclusion. However, the main goal of this paper is to invite into the social participation conversation a practical, yet theoretically rich, framing grounded in the social network perspective: Relational Inclusivity (RI). Conceptually, this shift emphasizes the importance of interdependent relationships in varied social contexts that educators must attend to in order to create socially responsive learning communities. To support educators’ application of this concept, we present a concrete measurement approach to explore RI in schools: the Social Network Analysis (SNA) Toolkit. Using this conceptual framing and tool, we provide insight into dynamics of four fundamental, overlapping social communities experienced by students: friendships, recess, academic support, and emotional connections. Together, we believe these four dimensions encompass the majority of students’ functional social interactions at school.

Theoretical framework: a social network perspective

From the social network perspective, learning is seen as a process of creating connections between pieces of information, concepts, experiences, and individuals (Borgatti et al., 2018). This perspective is a useful prism through which to understand the intimate connection between relationships and learning. Networks are seen as multiplex, with individuals simultaneously occupying different positions, roles, and identities across multiple communities at various levels (Collins, 2019; Crossley, 2022). Students engage in different types of relationships throughout the day across multiple social worlds that require them to mobilize and activate different schemas and skills (Lahire, 2011). Knowledge in this sense is not something that is static, but rather a dynamic network that is constantly changing and evolving. This view also has roots in sociocultural theories of learning, which emphasize the role of social interactions and cultural practices in mediating individual understanding. For example, Vygotsky and Cole (1978) argued that learning is a social process that occurs through interactions with others and that individuals internalize the knowledge and skills they learn from others to build their own understanding.

The social network perspective also approaches social structures as a function of human relationships (Crossley, 2022). Micro-changes at the dyadic level can, over time with repetition and reproduction, alter macro-level structures. Put differently, agency rests on the ability of knowledgeable actors to reflexively apply schema to an array of social contexts (Sewell, 1992). Reflexive actors can self-regulate, operating to either maintain the system as such or working to change it (Giddens, 1984). This reflexivity extends beyond just monitoring day-to-day interactions, but can also include a metacognitive element, where actors can consciously “monitor that monitoring” (Giddens, 1984, p. 29). Because (dis)ability is itself socially constructed (Valle and Connor, 2019), this perspective creates space to educators to fundamentally redefine how communities view and engage with notions of ability. Models of inclusion should seek to cultivate the social environment around all students, with the ultimate goal that natural human variation is valued rather than stigmatized. To shift away from paradigms of ‘fixing’ students, pedagogical and policy changes at different levels are needed to cultivate communities where students with SEND can actively participate in learning and develop relational ties with peers.

In this view, inclusion is dependent on understanding the ecological social systems that produce isolation around students with SEND. Rather than attributing challenges with social participation to a lack of or limited social skills associated with individual (dis)ability, recent research emphasizes the systemic barriers that educators place on students with SEND. For example, Garrote (2017) argues that studies which empirically challenge the claim that a lack of social skills is the main reason why students with SEND experience difficulties in social participation are scarce. We note that Dalkilic and Vadeboncoeur (2016) also point out that the individualistic frameworks currently dominating education support exclusionary practices and use a similar term to ours - relational inclusion. However, RI from the social network perspective is distinct in that the unit of analysis is not the individual but instead the dyad.

Defining relational inclusivity

We define RI as the degree to which all students are appropriately engaged across the various social dimensions of schooling (Mamas and Trautman, 2023). In previous work, we argued for the concept of RI as a fundamental ethical, moral, and pedagogical component to larger conceptualizations of inclusive education (Mamas and Trautman, 2023). Acknowledging that there exist multiple dynamic relationship contexts, we identify four core networks that we believe capture the majority of students’ functional social interactions at school: friendship networks, recess/play networks, academic support networks, and emotional wellbeing networks. Subsequently, we will demonstrate how sociograms across these dimensions can be used to visualize and drive inquiry around the extent to which RI occurs for students.

We distinguish RI from social participation, which empirically foregrounds friendship ties, relationship quality, and interactional behaviors across a number of theoretical frameworks. RI is inextricably linked to its theoretical underpinnings in the social network perspective, which has educator-friendly empirical applications and centers inclusive practices beyond those for students with SEND. We also note overlap with the literature on school belonging, a key feature of inclusion models which foreground social justice and educational equity (Valle and Connor, 2019). While belongingness can include teacher-student relationships, positive interactions, the feeling of acceptance by others (Slaten et al., 2016), however, RI looks specifically at the existence of concrete relationships between students across a variety of social domains within the school day. It examines less the extent to which students feel belonging generally and more the extent to which they actively and reciprocally participate in relationships with others across different contexts. While there can certainly be arguments for why empirical scholarship might favor one framing over another, we believe the advantage of RI conceptually for educators is that its grounding in social networks makes it intuitive, transferrable across different types of identity markers and educational spaces, actionable in terms of driving inquiry and interventions, and finally, that it provides a vision for a more just, equitable, and inclusive future for all youth.

We should note, however, that “appropriate engagement” is not necessarily a numerical concept. How many reciprocal friendship relationships one might need to feel a sense of inclusion or belonging can vary from student to student. Moreover, previous research has found that some students’ self-perception of acceptance is not tied to their peers’ actual social acceptance of them (Avramidis et al., 2018). RI uses practical measurement to guide educator inquiry into what appropriate engagement might look like for each student. It is fundamentally a tool to drive reflection and practice by recognizing patterns of engagement, seeking to understand them, and intervening when necessary to disrupt troubling social dynamics, such as isolation.

What we find compelling about the concept of RI is that it is not dependent upon the larger policies and structures surrounding education in order to be practically applied in the classroom. Instead, it can be pursued by teachers and educators who seek justice for all students, regardless of race, class, gender, ability, sexuality, or any other axis of difference which manifests itself in the learning environments they facilitate. Though RI may be conceptually and practically applied in relation to all students and student groups, we focus specifically on those identified as having SEND because these are the students most subject to officially justified exclusionary practice and have been labeled as having social deficits.

Looking at RI across four dimensions of schooling

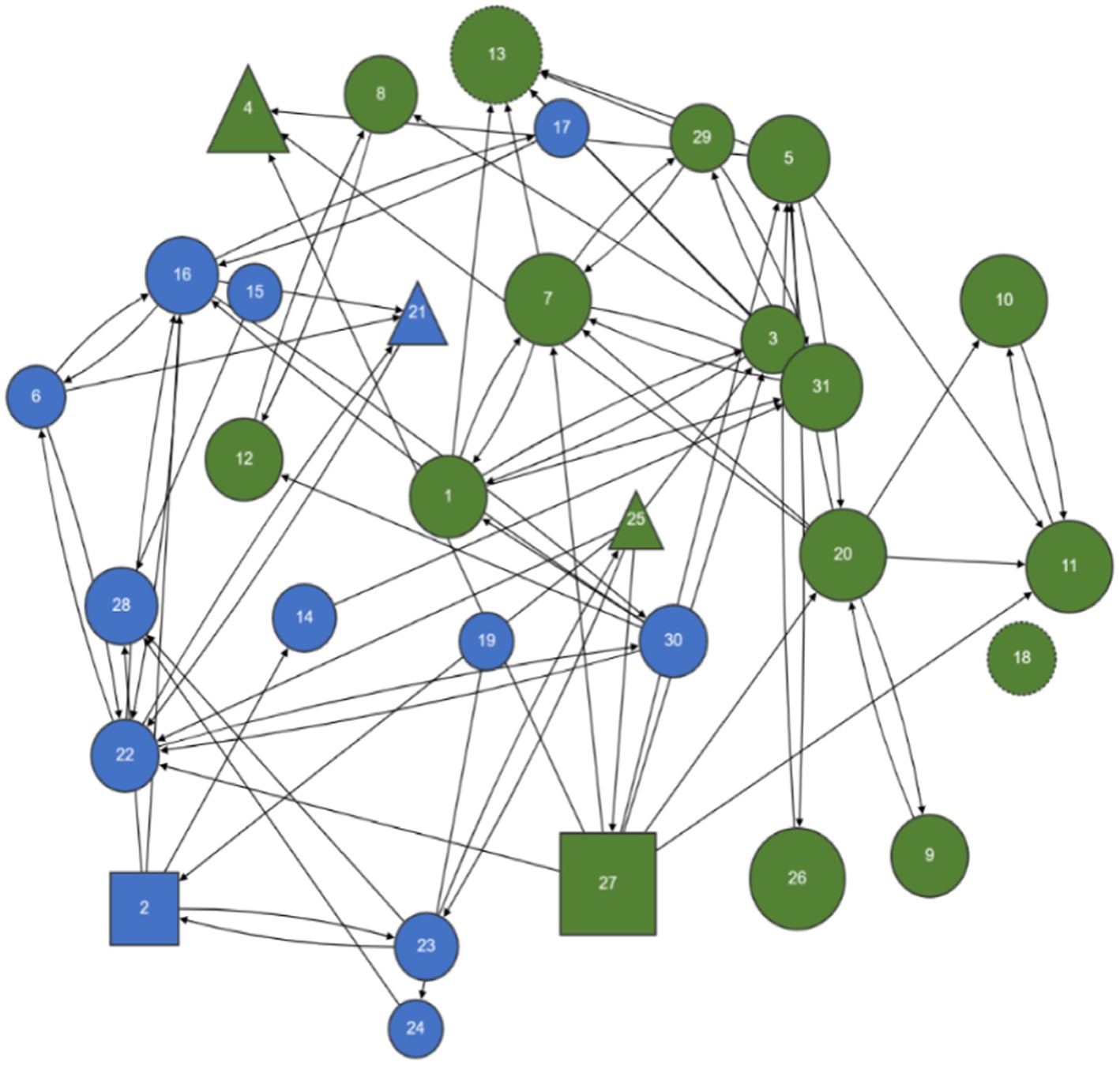

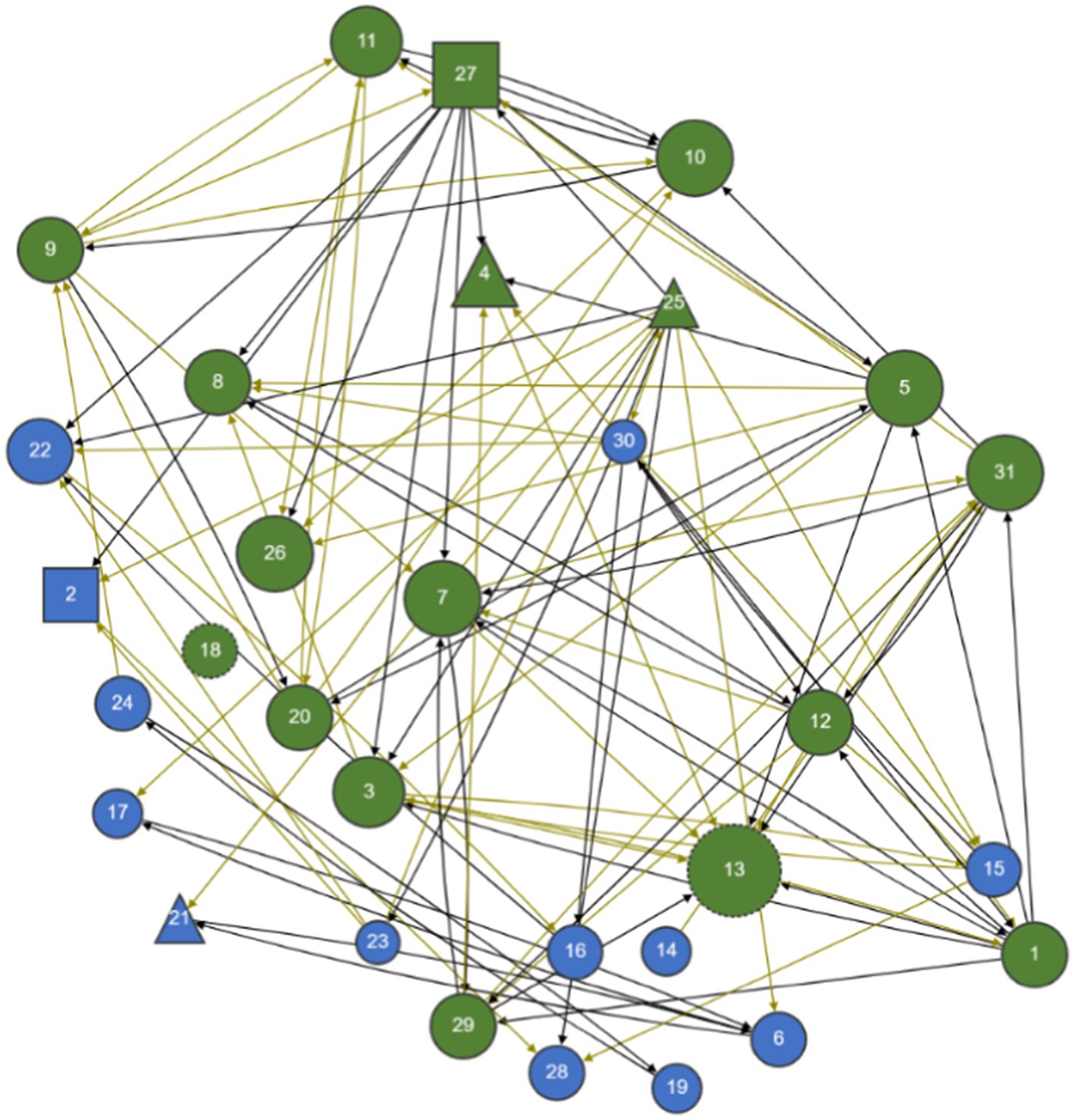

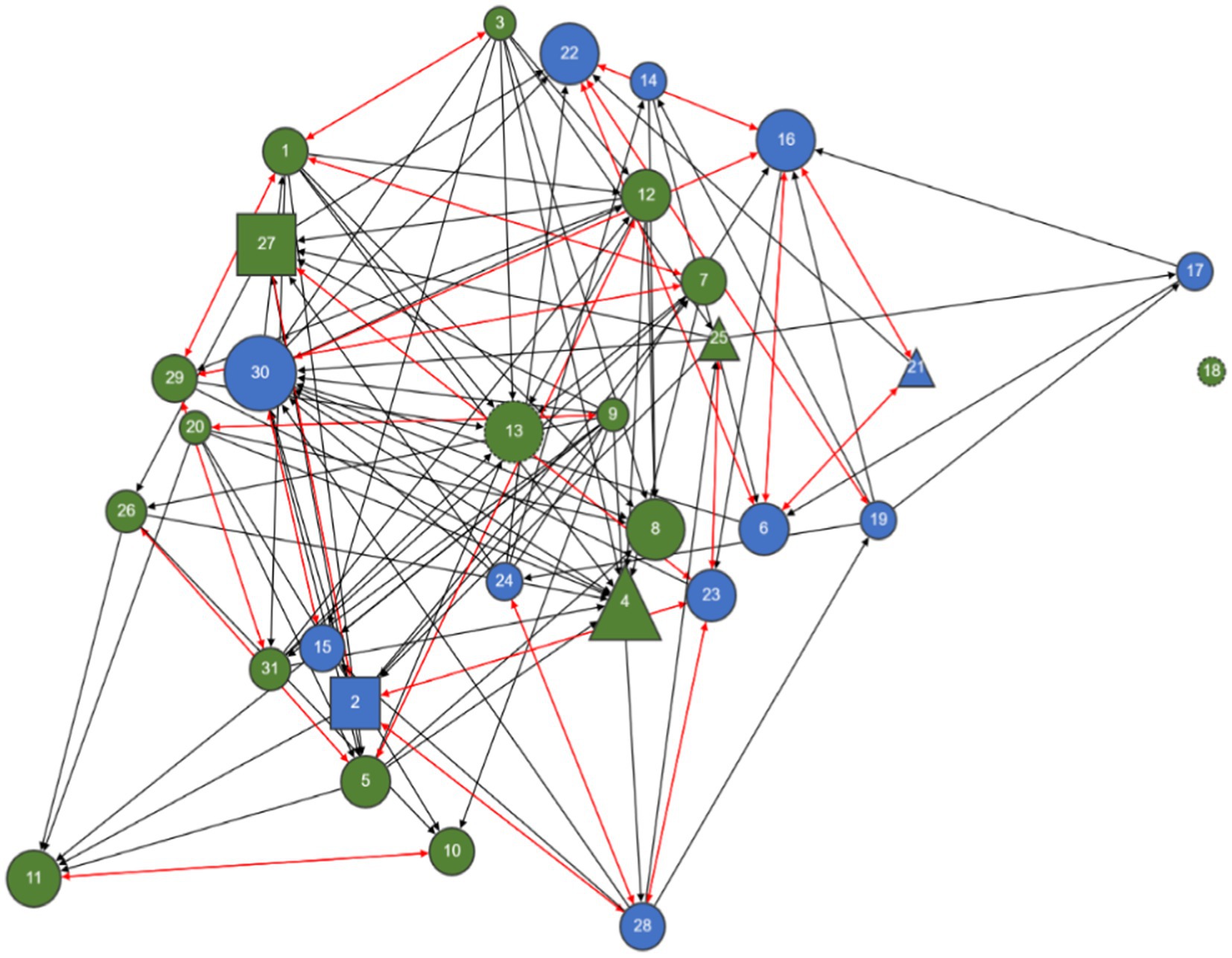

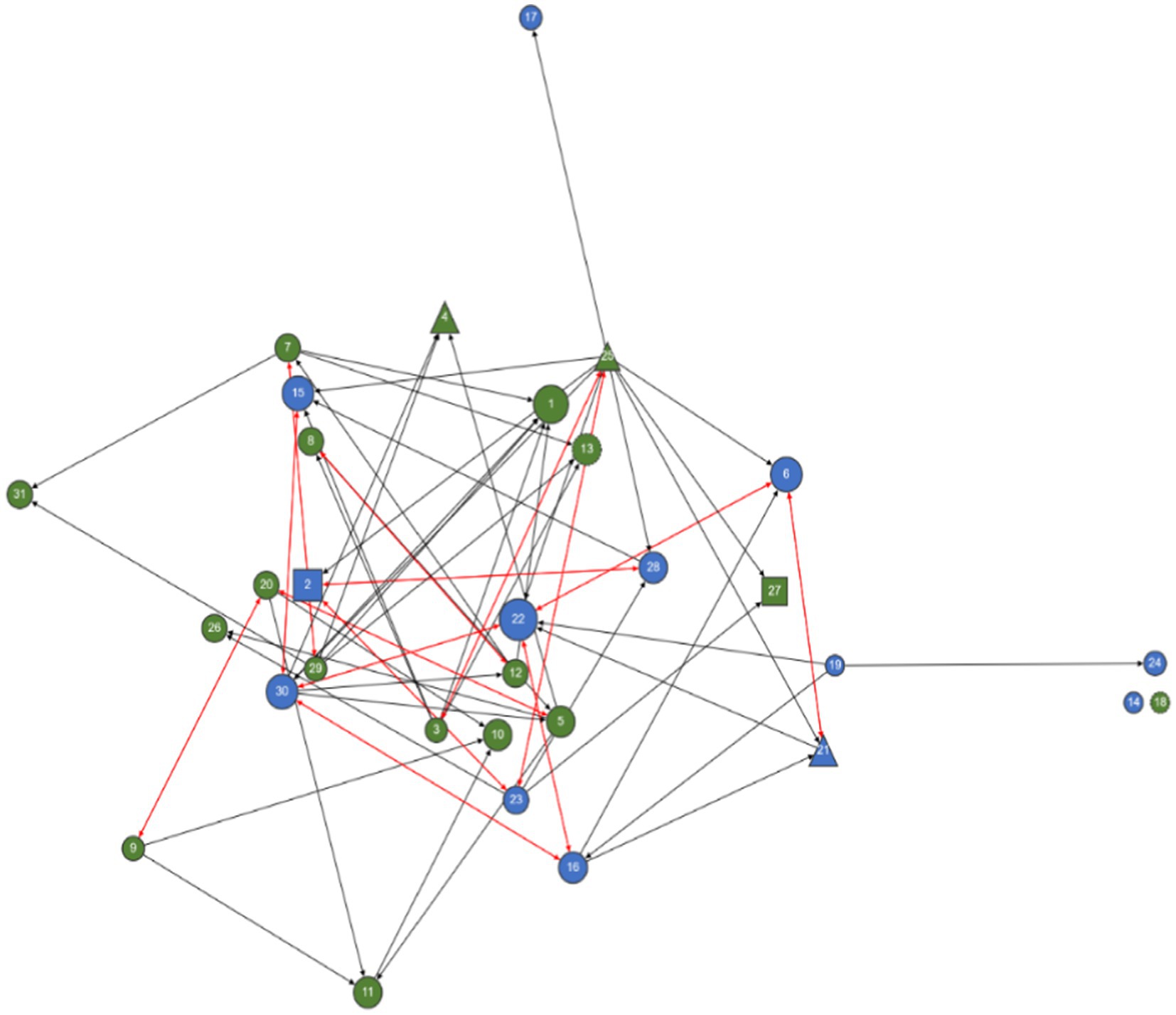

We argue that four dimensions capture the majority of functional relationships students rely on at school: friendship networks, play networks, academic support networks, and emotional support networks. These dimensions were identified through conversations and observations with youth in schools and were affirmed as significant in shaping inclusive experiences through a review of the literature (Mamas, 2025; Mamas et al., 2024). Though there is overlap between the dimensions, we show below that they each have distinct features. Below, we provide a brief description of recent literature on each of the four dimensions, particularly as it relates to the SEND population. We then present a sociogram that represents the connections between students in the sample classroom. Sociograms are visual representations of relationships within a particular system, fueled by mathematical theory to intentionally graph individuals (nodes) in relation to others based on their connectedness to others. For each section, we interpret the sociograms with particular attention to the implications for the inclusion of Students with SEND, with the goal of illustrating how educators might use these data to guide inquiry and practice in service of RI.

The particular set of maps we use in this paper comes from the students in one Grade 7 class in a highly diverse middle school in Southern California. Data were collected using the SNA Toolkit, a free web-based software teachers can use to map student social networks (Mamas et al., 2019b). The Toolkit produces a customizable survey which collects data through a nomination process. At the time of data collection, there were 31 students in the classroom, 13 girls and 18 boys. Three of the students have been identified as having a SEND and two of them exited special education services. Each student is represented by a numbered node that remains consistent in each network map (i.e., node 1 represents the same student across all maps/graphs). All but two of the students completed the survey. It is important to highlight that to get a meaningful picture of RI into the classroom, 75% or more of the students should complete the survey. Partial data can create distortions, as missing nodes or ties may misrepresent the network’s structure (Kossinets, 2006). This can lead to educators drawing incomplete or misleading conclusions about the inclusivity of their classrooms. To mitigate this, we recommend that educators pair SNA findings with qualitative observations and student interviews, ensuring that the broader social context is captured alongside quantitative network data. Furthermore, we emphasize the importance of this data as a tool for inquiry and reflection by teachers about how they shape relational systems in their classrooms, not evaluation or judgement of either students or themselves. Fundamentally, the data reflects how interdependent social systems are organized, not whether any given individual is solely responsible for anyone’s positioning (including their own).

Each geometric feature of the sociograms has meaning. The shape of each node shows student SEND status, with circles representing non-SEND, triangles representing SEND, and squares representing students who have exited from SEND services. Green nodes represent students who identify as male, while blue nodes represent students who identify as female. Nodes are sized by the number of in-degree nominations (the number of times this student was nominated by others for this type of connection). Nodes with a dashed outline represent students who did not participate in the network survey, but who are included in the sociogram because they were nominated by others. Arrows, known as edges, show the direction of the relational tie. Double arrows in the friendship and recess/hang out networks or red double-edged arrows in academic support and emotional wellbeing networks represent reciprocated ties, meaning that both students selected each other.

It is also important to note that while we find social network analysis tools particularly useful in visualizing and mapping network relationships, RI is not dependent upon them; educators may still intentionally attend to relational dynamics across the four dimensions without network data. That said, we advocate for the SNA Toolkit for a couple of reasons. First, attentiveness to the relationships students form across their schooling experience is less attended to in educational measurement paradigms, which tend to place a stronger emphasis on individualized academic outcomes. Second, social network mapping allows students to self-report relationships that may otherwise go unobserved or unnoticed by educators. Third, it provides a mechanism to demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions, as periodic sampling can reveal changes in network characteristics over time.

Friendship dimension

A large body of research indicates the importance of friendship for both youth and adults with and without SEND. Friendships have been found to be conducive towards the social and emotional development of children and adolescents (Bagwell and Bukowski, 2018). Friendship quality has been reported to protect against depressive symptoms for pre-adolescents both on and off the autism spectrum (O’Connor et al., 2022) and is related to less loneliness (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020). Researchers have also found a positive relationship between the size of adolescents’ social networks and their sense of satisfaction and confidence (Ferguson et al., 2022). At the same time, friendship quality for certain age groups can be impacted in Students with SEND, such as those with ADHD (Rokeach and Wiener, 2022). Despite the potential challenges of navigating relationships for students with SEND, all children both can and need to form deep and meaningful friendships. Adults can play a key role in supporting this, particularly in facilitating relationships between typically developing children and those identified as having more complex disabilities (Rossetti and Keenan, 2018). Given the positive impact of friendship on youth and the recognition that it may be more challenging for some children–regardless of disability status–to form relationships, we believe it is a crucial aspect of schooling for educators to monitor and support.

Figure 1 shows a friendship network map for the sample classroom. To identify connections, students were provided with a names list of their classmates and asked “Who are your friends in this classroom?” After identifying these individuals, students were prompted to select whether they were “very good friends,” “good friends,” or “sort of friends.” The network graph shows only the connections identified as “very good friends.” This is because stronger ties are more likely to be vehicles for transmitting knowledge, resources, and support (Krackhardt et al., 2003). These ties are also more likely to be reciprocated, indicating the existence of a mutual friendship. Additionally, from a social–emotional perspective, friendship quality impacts the benefits of the relationship (Dryburgh et al., 2022; Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020).

Looking at the Students with SEND in this sociogram, a few important noticings come to light with respect to RI. First, we see that Student 4, who identifies as male, has three in-degree nominations but no out-degree nominations indicating no reciprocal friendships. This is inconsistent with literature which finds that students with SEND tend to overestimate their friendships (Pijl et al., 2008; Schwab et al., 2019). Given the high number of in-degree nominations by other students, Student 4’s asymmetrical estimation of very good friendships merits further inquiry by their educator. For example, the absence of reciprocal friendships for Student 4 may reflect differences in how relationship intensity is perceived by students; while Student 4 has no outgoing ties in the ‘very good friends’ category, they may have perceived these relationships as ‘good friends’ or ‘sort of friends.’ An alternate explanation could be related to this students’ self-confidence. A similar pattern can be observed with Student 21, who also underestimates the number of very good friendships in relation to their in-degree nominations. An important contrast, however, is that 21 has two reciprocal friendships. While Student 25 has at least one reciprocal friendship nomination, they appear to report significantly more outgoing relationships in comparison to their incoming nominations. This may be an indication of aspirational friendship, or possibly general conviviality. These speculations should be handled with caution, however; the sociogram is not a tool to diagnose causal factors, but to stimulate inquiry around social relations. We emphasize that varying interpretations of social connections can be investigated by complementing network analysis with qualitative insights.

Recess dimension

Numerous studies point to the academic, social–emotional, and learning benefits of recess to all children (Hodges et al., 2022; Burson and Castelli, 2022). Despite these benefits, there is a clear link between not just the quantity of recess interactions children have, but also the quality (Massey et al., 2021a). However, recess is not just a time for play to occur, but also potential incidents of bullying or harm (Özkal, 2020). Adults, therefore, play a key role in shaping the recess environment, from ensuring safety and equipment to supporting students’ social behaviors (Massey et al., 2021b). Students with SEND may require additional support (e.g., prompting) from adults to meaningfully engage; researchers have found that simply being physically present at recess does not result in inclusion for students on the Autism spectrum, for example (Vincent et al., 2018). As we might expect, students with SEND positively experience strong relationships at recess and negatively experience both real and perceived exclusion (Rubuliak and Spencer, 2022). Educators cannot, therefore, assume that productive classroom relationships will transfer over to the recess environment. Working towards RI means monitoring if and how relationships occur at recess - a time when classroom teachers may or may not be present to observe - and take proactive steps to ensure that these spaces are inclusive for all students.

Figure 2 shows a recess/‘hang out’ network map for the sample classroom. To identify connections, students were provided with a names list of their classmates and asked “Who do you hang out with at recess/non-class time?” After identifying these individuals, students were prompted to select whether they hang out “daily” “once/twice a week,” or “once/twice a month.” As will the friendship dimension, we prioritize stronger relationships; the network graph shows only the hangout/play relational ties that existed on a daily and weekly basis. This network map shows some similar patterns to the Friendship map. Student 4 has four incoming nominations and one outgoing nomination with no reciprocal ties. It is again interesting here to see that this particular student asymmetrically estimates their relational ties; their perception of who they hang out with during recess is not aligned with the assessment of their peers. Student 21 seems to have a more symmetrical perception of their recess relational ties. Of note, their reciprocal tie at recess is with a different individual than their reciprocal friendship tie; this suggests that this student conceptualizes friendships and play relationships differently. Student 21 appears to distinguish between the social roles their classmates play. Indeed, the different structure of this map suggests that playmates are not necessarily friends, and vice versa. Conversely, Student 25 continues to significantly estimate a greater number of play relations (11) than they receive (1). We note that their one nomination is reciprocal and with the same student they shared reciprocity with in the Friendship dimension. A potential avenue for further inquiry by the classroom teacher may be the relational dynamic between Student 25 and their reciprocal friend, Student 23. If this student’s asymmetrical nominations map onto any observed social concerns, they might leverage an understanding of this reciprocal relationship to support Student 25’s socialization at school with other peers.

Academic support dimension

In general, peer academic support has been found to be beneficial for all students, including students with and without SEND (Cushing and Kennedy, 1997). In particular, peer academic support was found to increase confidence, improve social skills, and increase academic engagement for students with SEND (Brock and Huber, 2017; Scheef and Buyserie, 2020). Students who reported greater peer support are also more likely to have a higher sense of school belonging (Vargas-Madriz and Konishi, 2021). Additionally, students with SEND who receive peer academic support tend to achieve improved grades and academic outcomes (Vargas-Madriz and Konishi, 2021) and they can expand their social networks by providing an opportunity for the development of friendships (Carter et al., 2016). Finally, according to Carter et al. (2016), peer academic support was shown to help students without SEND to have a deeper self-understanding, more enhanced and positive views regarding peers with SEND, increased views of the value of diversity as well as development of advocacy skills.

Figure 3 shows the academic support network map for the sample classroom. To identify relational ties, students were provided with a names list of their classmates and asked “If the teacher is not around, who do you turn to for help on school work? Check as many classmates in the list below.” This prompt did not include a tie strength or frequency dimension, meaning that students only had to select classmates they go to for help on school work, without specifying how often they seek out help or how much they value that help.

From an inclusion perspective, this particular classroom’s academic support network is heartening; all students with SEND appear fully integrated into the fabric of the learning community. While all three students with SEND in this class (4, 25, 21) have been designated with a Specific Learning Disability and receive services related to their academic learning, they all have incoming nominations. In other words, this designation has not prevented them from being seen by their peers as sources of academic support, which runs contrary to what we have observed in many classrooms. This is an interesting finding, as students with SEND related to learning are perceived as needing more academic support than their non-SEND peers (Mamas et al., 2019a; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), 2004). Despite this, Student 4 appears to be an academic leader in their classroom, with one of the largest in-degree nominations (n = 10) of all students in the class. However, consistent with their other responses, they do not indicate that they seek support from peers. Students 21 and 25 also had incoming nominations, 2 and 3 respectively, as well as outgoing nominations, 3 and 5, respectively. This suggests that these two students had a more balanced network of relationships, in which they both give and receive academic support from peers. These observations are encouraging as they show that teachers can facilitate learning environments where SEND designations do not limit students from becoming important sources of academic support to their peers. An area of inquiry around stimulated by this network may be focused on identifying the classroom systems around instruction and collaboration that contribute to this positive dynamic.

Emotional wellbeing dimension

According to Hamilton and Redmond (2010), emotional wellbeing is a broad term that includes feelings, behavior, relationships, goals and personal strengths. They also note it might be displayed differently depending on culture, temperament and individual differences. It is generally acknowledged that emotional wellbeing is an important aspect of overall health and can have a significant impact on the quality of life for students with SEND (Park et al., 2002). This can be achieved by creating a welcoming, socio-emotionally responsive and inclusive atmosphere in schools and classrooms, promoting open communication, trust and positive relationships with peers and teachers. However, past research has shown that students with SEND maintain a limited sense of emotional wellbeing at school compared with their peers. These students were found to experience higher degrees of loneliness, bullying, and exclusion (Koller et al., 2018). Especially during the COVID pandemic, students with SEND experienced more negative emotions, including feeling more nervous and sadness than before (Berasategi Sancho et al., 2022).

Figure 4 shows the emotional wellbeing network map for the sample classroom. To identify relational ties, students were provided with a names list of their classmates and asked “If you are having a bad day at school, who do you talk to? Check as many classmates in the list below.” In the same manner as in Figure 3, this prompt did not include a tie strength or frequency dimension.

A similar picture is observed here in relation to the incoming and outgoing nominations of the three students with SEND. It should be noted that the support networks center students’ individual actions rather than perceptions of others. In other words, outgoing nominations reflect the extent to which students engage in outreach for support. A lack of outgoing ties can thus reflect either a lack of need (never having a bad day) or difficulty asking for help. With regard to the students with SEND, Student 21 continues to show balanced, relatively symmetrical nominations (including one reciprocal), suggesting that they both give and receive emotional support. Student 25’s 11 outgoing nominations suggest that they are very comfortable leaning on and sharing with others, consistent with their friendship estimations. They also have two reciprocal nominations, indicating that they possess some mutual emotional support relationships. However, there are a few students who have no outgoing nominations, which is concerning regardless of SEND status. Student 4 has incoming nominations (3), significantly fewer than in the academic support network, but no outgoing nominations. Similarly, Students 31, 24, and 17 have incoming ties, but no outgoing ties. Student 14, though they have ties in all the other networks (though their Recess network is relatively sparse) is completely isolated in the emotional wellbeing network.1 This data point may be important for teachers to follow up, engaging in exploration and inquiry to better understand why this particular network appears to be underdeveloped for so many students. It may necessitate implementing some pedagogical activities that support the ways in which students seek and provide emotional support to one another. An important line of pedagogical inquiry based on this graph would address the extent to which classroom systems support the level of safety and vulnerability students need in order to seek emotional support from their peers. We emphasize that, as this sociogram suggests, friendships are not necessarily vehicles for emotional support for all students.

Discussion and implications for inclusive practice

The sociograms/network maps presented above show how students’ networks vary across the four dimensions and provide a starting point for educator inquiry. These four dimensions go beyond friendship in order to capture the various relationships students navigate throughout the course of their school day. Despite some overlap, we see that they also each possess their own unique structure. This is because students may draw on others they perceive as experts for academic support even if they do not have a friendship tie, for example. Similarly, they may regularly play at recess with other students that they do not particularly like (e.g., a soccer match with many peers).

It is important to approach peer nominations with caution as perceptions are inherently subjective. While SNA provides valuable insights into relationships, it does not privilege the accuracy of one group’s perceptions over another’s. For students with SEND, their self-reported ties may reflect unique relational dynamics that are equally valid and should be interpreted alongside the nominations made by their peers. At the same time, we believe these data provide valuable opportunities for inquiry around the nature of inclusivity within classroom communities beyond simple co-presence.

In the sociograms above, we see that communities in educational settings extend beyond friendship circles and encompass a range of interconnected social networks that contribute to students’ overall experiences and well-being. Friendships involve close, reciprocal relationships built on shared interests, trust, and emotional support. Friendships play a significant role in fostering a sense of belonging, social integration, and positive peer interactions. Recess and play interactions occur during unstructured break times and play a vital role in providing opportunities for socialization, engagement in physical activities, and the development of social skills such as cooperation, conflict resolution, and negotiation. Recess interactions can contribute to students’ social development, well-being, and overall sense of belonging within the school community. Academic support networks involve interactions and collaborations focused on academic tasks, study groups, or peer tutoring. Academic support networks provide students with opportunities to learn from one another, share knowledge, and receive assistance, ultimately enhancing their academic goals and fostering a sense of collective responsibility for learning within the community. Emotional well-being networks consist of relationships that focus on emotional support, empathy, and understanding. They provide a safe space for students to express their feelings, seek guidance, and receive support during challenging times. Additionally, emotional well-being networks contribute to students’ mental health, resilience, and overall emotional well-being, creating a supportive and caring community environment. Each of these dimensions is important to attend to with intentionality if we want to create flourishing learning communities for all students, regardless of diagnosed ability. RI takes an expansive look at the different contexts in which relationships are salient for students’ academic and social success. Perhaps most importantly, it offers practitioners both a theoretical perspective and a relatively easy-to-use measurement tool to guide practical inquiry. RI is a distinct perspective to social participation because it emphasizes the importance of interdependent relationships from a social network perspective. The social network perspective highlights the interconnectedness and interplay of relationships and stresses the importance of fostering positive and supportive social connections among students. This perspective decenters individuals and instead looks at the dynamic between individuals. Responsibility for inclusion thus is not placed on students with SEND, but on how communities relate to perceived ability. It places emphasis on pedagogical intervention into relational systems rather than seeking to fix individuals; questions should not ever revolve around “how do we get Student X to make more friends?” and instead around “in what ways might our classroom routines support the development of robust, reciprocal friendships in our learning community?”

It should be noted here that we do not argue about favoring RI over social participation. While social participation encompasses various dimensions such as friendships, interactions, and peer acceptance, RI shifts focus to the dyadic and network-level structures underlying these dimensions. Unlike social participation, which often centers on inclusion outcomes or perceptions, RI uses a social network perspective to emphasize the mutual, reciprocal ties that create functional social ecosystems in classrooms. This distinction allows RI to highlight structural inequalities within these ecosystems and provide actionable insights that address systemic barriers. For example, a student may feel a sense of belonging but lack reciprocated social ties, which RI identifies as a gap in inclusion that social participation measures may overlook.

The SNA Toolkit can be used by educators to examine the specific relational ties and dynamics within four social network ties experienced by students, namely friendships, recess, academic support, and emotional connections. We argue that by focusing on these dimensions, educators can gain a comprehensive understanding of students’ social experiences and effectively promote positive relationships and social integration within the school environment. When educators take an inquiry stance towards the relationships in these dimensions, they can better structure supports that create more open and welcoming communities for all students (Mamas et al., 2024). It should be noted that educators are encouraged to use their own relational questions as well and to adapt any questions they use to the age and/or developmental level of their students. We believe that this approach and tool can support educators’ meaning making around how difference is navigated in the social communities they facilitate.

This perspective is somewhat at odds with the dominant measurement paradigm in education, which primarily focuses on individual achievement. Traditional assessment approaches emphasize the outcomes and achievements of individuals, overlooking the broader social and systemic factors that influence their educational experiences. Notably, factors such as ableism, racism, sexism, homophobia, and poverty are all systemic axes of oppression experienced by children, yet when students do not perform on traditional indicators academic success they are held individually responsible through a deficit narrative for their supposed lack of ability or grit. Though we focus on dynamics of ability in this paper, RI and the SNA Toolkit can be used to examine the extent to which children experience inclusion across social dimensions along any axis of difference. This perspective provides a framework for analyzing the patterns of relationships and social ties among individuals/students, providing more nuanced insights into the larger social structures that shape social interactions between students and their peers at school. Educators can use this to craft more welcoming, inclusive communities for all students (Mamas et al., 2024; Mamas and Mallén-Lacambra, 2025).

As a tool for inquiry, RI and the SNA Toolkit can uncover troubling patterns in social structures as well as reveal unrecognized social isolation and other potentially hidden structures that impact students’ experiences and social engagement. At the same time, educators need to take into account that more ties do not necessarily equate with enhanced RI. Ties vary in both quality and reciprocity and there is no clear optimal number of ties for students to have. What is considered an appropriate level of engagement varies from student to student, though we generally advocate the importance of some degree of symmetry and reciprocity. As such, the SNA Toolkit should not be used as an assessment of students’ popularity or a teacher’s effectiveness. We situate it purely as an educator-oriented tool for reflection and growth so that they can better attend to their communities of students. Data from the Toolkit is not intended for use in student-facing contexts; it should never be used to evaluate, shame, or to responsibilise students for their relationships. Additionally, the practical application of RI and the SNA Toolkit extends beyond mapping relationships. Educators can use these tools to identify students who may be socially isolated or marginalized and implement interventions with intentionality such as peer mentoring or structured group activities to foster inclusive relationships. Professional development can equip educators with strategies to build relationally responsive classrooms that actively support diverse learners, and the toolkit can help demonstrate the impact of this work over time.

By acknowledging and nurturing these four dimensions of RI, educators can systematically work to foster relationally inclusive and supportive educational communities. Recognizing the importance of friendships, recess interactions, academic support networks, and emotional well-being networks allows for a holistic understanding of students’ social experiences and enables the implementation of targeted interventions and support systems. Emphasizing the development and maintenance of these diverse social networks can contribute to enhanced RI, a sense of belonging, and the overall well-being of all students within the educational and wider community.

Conclusion

Our paper introduced the concept of Relational Inclusivity (RI) as a distinct perspective to examine the inclusion of students in general education classrooms. We propose that educators can and should actively attend to RI in four dimensions of social relationships: friendships, recess interactions, academic support networks, and emotional well-being networks. However, it is not enough to simply emphasize the importance of building a relationally responsive, inclusive and well-connected classroom community; educators should also be able to operationalize that rhetoric. Our paper used data from the Social Network Analysis (SNA) Toolkit to explore the variations between these dimensions for students with SEND in a middle school classroom. By examining these dimensions, educators can gain a comprehensive understanding of students’ social experiences and effectively promote positive relationships and social integration within the school environment. This attention can extend beyond students with SEND and encompasses all students in the classroom, though greater attention is warranted for those students who have been traditionally marginalized in educational settings. By emphasizing the importance of interdependent relationships from a social network perspective, RI recognizes classrooms as complex social systems. RI offers a different approach to measurement, shifting the focus from individual perceptions to the interconnectedness of individuals’ perceptions and relationships within communities and structures. This perspective helps uncover the hidden social structures that impact students’ experiences and social engagement, providing more nuanced insights into the larger social factors that shape educational environments. This approach can inform targeted interventions, support systems, and the creation of inclusive environments that promote positive relationships and foster the overall well-being of all students.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UC San Diego IRB (#800803). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Though student 18 is also an isolate in the network, they did not participate in the survey and thus we do not have an accurate read on their possible outgoing nominations.

References

Avramidis, E. (2013). Self-concept, social position and social participation of pupils with SEN in mainstream primary schools. Res. Pap. Educ. 28, 421–442. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2012.673006

Avramidis, E., Avgeri, G., and Strogilos, V. (2018). Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 221–234. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424779

Bagwell, C. L., and Bukowski, W. M. (2018). “Friendship in childhood and adolescence: features, effects, and processes” in Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. eds. W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, and K. H. Rubin. 2nd ed (Guilford: The Guilford Press), 371–390.

Berasategi Sancho, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaria, M., and Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. (2022). The well-being of children with special needs during the COVID-19 lockdown: academic, emotional, social and physical aspects. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 776–789. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1949093

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., and Johnson, J. C. (2018). Analyzing social networks. Los Angeles: Sage.

Bossaert, G., de Boer, A. A., Frostad, P., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2015). Social participation of students with special educational needs in different educational systems. Ir. Educ. Stud. 34, 43–54. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2015.1010703

Brock, M. E., and Huber, H. B. (2017). Are peer support arrangements an evidence-based practice? A systematic review. J. Spec. Educ. 51, 150–163. doi: 10.1177/0022466917708184

Burson, S. L., and Castelli, D. M. (2022). How elementary in-school play opportunities relate to academic achievement and social-emotional well-being: systematic review. J. Sch. Health 92, 945–958. doi: 10.1111/josh.13217

Carter, E. W., Asmus, J., Moss, C. K., Biggs, E. E., Bolt, D. M., Born, T. L., et al. (2016). Randomized evaluation of peer support arrangements to support the inclusion of high school students with severe disabilities. Except. Child. 82, 209–233. doi: 10.1177/0014402915598780

Crossley, N. (2022). A dependent structure of interdependence: structure and agency in relational perspective. Sociology 56, 166–182. doi: 10.1177/00380385211020231

Cushing, L. S., and Kennedy, C. H. (1997). Academic effects of providing peer support in general education classrooms on students without disabilities. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 30, 139–151. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-139

Dalkilic, M., and Vadeboncoeur, J. A. (2016). Re-framing inclusive education through the capability approach: an elaboration of the model of relational inclusion. Glob. Educ. Rev. 3, 122–137.

De Bruin, K. (2020). “Does inclusion work?” in Inclusive education for the 21st century ed. L. J. Graham (London: Routledge), 55–76.

Dryburgh, N. S., Ponath, E., Bukowski, W. M., and Dirks, M. A. (2022). Associations between interpersonal behavior and friendship quality in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis. Child Dev. 93, e332–e347. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13728

Ferguson, S., Brass, N. R., Medina, M. A., and Ryan, A. M. (2022). The role of school friendship stability, instability, and network size in early adolescents’ social adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 58, 950–962. doi: 10.1037/dev0001328

Frederickson, N., Dunsmuir, S., Lang, J., and Monsen, J. J. (2004). Mainstream-special school inclusion partnerships: pupil, parent and teacher perspectives. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 8, 37–57. doi: 10.1080/1360311032000159456

Garrote, A. (2017). The relationship between social participation and social skills of pupils with an intellectual disability: A study in inclusive classrooms. Frontline Learning Research, 5, 1–15.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Hamilton, M., and Redmond, G. (2010). Conceptualisation of social and emotional wellbeing for children and young people, and policy implications. Canberra, Australia: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. F., and Rivkin, S. G. (2009). New evidence about Brown v. Board of Education: the complex effects of school racial composition on achievement. J. Labor Econ. 27, 349–383. doi: 10.1086/600386

Heiman, T., and Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2020). Social-emotional profile of children with and without learning disabilities: the relationships with perceived loneliness, self-efficacy and well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:7358. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207358

Hodges, V. C., Centeio, E. E., and Morgan, C. F. (2022). The benefits of school recess: a systematic review. J. Sch. Health 92, 959–967. doi: 10.1111/josh.13230

Humphrey, N., and Symes, W. (2011). Peer interaction patterns among adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream school settings. Autism 15, 397–419. doi: 10.1177/1362361310387804

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). (2004) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A., and Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2011). Social networks and friendships at school: comparing children with and without ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x

Koller, D., Pouesard, M. L., and Rummens, J. A. (2018). Defining social inclusion for children with disabilities: a critical literature review. Child. Soc. 32, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/chso.12223

Kossinets, G. (2006). Effects of missing data in social networks. Soc. Networks 28, 247–268. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.07.002

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., Nakken, H., and Van Houten, E. (2010). Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 57, 59–75. doi: 10.1080/10349120903537905

Koster, M., Timmerman, M. E., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., and van Houten, E. J. (2009). Evaluating social participation of pupils with special needs in regular primary schools: examination of a teacher questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 25, 213–222. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.25.4.213

Krackhardt, D., Nohria, N., and Eccles, B. (2003). “The strength of strong ties” in Networks in the knowledge economy. eds. R. Cross, A. Parker, and L. Sasson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kwan, C., Gitimoghaddam, M., and Collet, J. P. (2020). Effects of social isolation and loneliness in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: a scoping review. Brain Sci. 10:786. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10110786

Lahire, B. (2011). The plural actor (D. Fernback, trans.). Cambridge, UK, and Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Polity (original work published 2001).

Lindsay, G. (2007). Educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77, 1–24. doi: 10.1348/000709906X156881

Lüddeckens, J. (2021). Approaches to inclusion and social participation in school for adolescents with autism spectrum conditions (ASC)—a systematic research review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 8, 37–50. doi: 10.1007/s40489-020-00209-8

Mamas, C. (2013). Understanding inclusion in Cyprus. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 28, 480–493. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2013.820461

Mamas, C. (2025). Relational inclusivity: eliciting student perspectives on friendship. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 11:101410. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101410

Mamas, C., Bjorklund, P. Jr., Cohen, S. R., and Holtzman, C. (2023). New friends and cohesive classrooms: a research practice partnership to promote inclusion. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 4:100256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100256

Mamas, C., Cohen, S. R., and Holtzman, C. (2024). Relational inclusivity in the elementary classroom: A Teacher’s guide to supporting student friendships and building nurturing communities. London: Taylor & Francis.

Mamas, C., Daly, A. J., Cohen, S. R., and Jones, G. (2021). Social participation of students with autism spectrum disorder in general education settings. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 28:100467. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100467

Mamas, C., Daly, A. J., and Schaelli, G. H. (2019a). Socially responsive classrooms for students with special educational needs and disabilities. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 23:100334. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100334

Mamas, C., Daly, A. J., Struyve, C., Kaimi, I., and Michail, G. (2019b). Learning, friendship and social contexts: introducing a social network analysis toolkit for socially responsive classrooms. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 33, 1255–1270. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-03-2018-0103

Mamas, C., and Mallén-Lacambra, C. (2025). Ethics of care: a theoretical underpinning for relational inclusivity [Ética de los cuidados: una base teórica Para la inclusividad relacional]. Teoría Educ. Rev Interuniv. 37. doi: 10.14201/teri.32183

Mamas, C., Schaelli, G. H., Daly, A. J., Navarro, H. R., and Trisokka, L. (2020). Employing social network analysis to examine the social participation of students identified as having special educational needs and disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 67, 393–408. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2019.1614153

Mamas, C., and Trautman, D. (2023). “Leading Toward Relational Inclusivity for Students Identified as Having Special Educational Needs and Disabilities”. eds. Y-H Liou, and A. J. Daly (London: Bloomsbury Academic).

Massey, W. V., Perez, D., Neilson, L., Thalken, J., and Szarabajko, A. (2021b). Observations from the playground: common problems and potential solutions for school-based recess. Health Educ. J. 80, 313–326. doi: 10.1177/0017896920973691

Massey, W. V., Thalken, J., Szarabajko, A., Neilson, L., and Geldhof, J. (2021a). Recess quality and social and behavioral health in elementary school students. J. Sch. Health 91, 730–740. doi: 10.1111/josh.13065

O’Connor, R. A. G., van den Bedem, N., Blijd-Hoogewys, E. M. A., Stockmann, L., and Rieffe, C. (2022). Friendship quality among autistic and non-autistic (pre-) adolescents: protective or risk factor for mental health? Autism 26, 2041–2051. doi: 10.1177/13623613211073448

Özkal, N. (2020). Teachers’ and school administrators’ views regarding the role of recess for students. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 16, 121–137. doi: 10.29329/ijpe.2020.277.8

Park, J., Turnbull, A. P., and Turnbull, H. R. III. (2002). Impacts of poverty on quality of life in families of children with disabilities. Except. Child. 68, 151–170. doi: 10.1177/001440290206800201

Pijl, S. J., Frostad, P., and Flem, A. (2008). The social position of pupils with special needs in regular schools. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 52, 387–405. doi: 10.1080/00313830802184558

Prince, E. J., and Hadwin, J. (2013). The role of a sense of school belonging in understanding the effectiveness of inclusion of children with special educational needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 238–262. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.676081

Qi, J., and Ha, A. S. (2012). Inclusion in physical education: a review of literature. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 59, 257–281. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2012.697737

Rokeach, A., and Wiener, J. (2022). Predictors of friendship quality in adolescents with and without attention-deficit /hyperactivity disorder. Sch. Ment. Heal. 14, 328–340. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09508-3

Rossetti, Z., and Keenan, J. (2018). The nature of friendship between students with and without severe disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 39, 195–210. doi: 10.1177/0741932517703713

Rubuliak, R., and Spencer, N. L. I. (2022). ‘Everyone’s just like, they’re fine, and when in reality, are we?’ Stories about recess from children experiencing disability. Sport Educ. Soc. 27, 167–181. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2021.1891041

Slaten, C. D., Ferguson, J. K., Allen, K. A., Brodrick, D. V., and Waters, L. (2016). School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33, 1–15.

Scheef, A., and Buyserie, B. (2020). Student development through involvement: benefits of peer support arrangements. J. Risk Issues 23, 1–8.

Schwab, S., Lindner, K. T., Helm, C., Hamel, N., and Markus, S. (2021). Social participation in the context of inclusive education: primary school students’ friendship networks from students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 834–849. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1961194

Schwab, S., Wimberger, T., and Mamas, C. (2019). Fostering social participation in inclusive classrooms of students who are deaf. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 66, 325–342. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2018.1562158

Schwartz-Mette, R. A., Shankman, J., Dueweke, A. R., Borowski, S., and Rose, A. J. (2020). Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 146, 664–700. doi: 10.1037/bul0000239

Sewell, W. H. (1992). A theory of structure: duality, agency, and transformation. In source. Am. J. Sociol. 98, 1–29. doi: 10.1086/229967

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education: adopted by the world conference on special needs education; Access and quality. Salamanca, Spain: UNESCO.

Valle, J. W., and Connor, D. J. (2019). Rethinking disability: a disability studies approach to inclusive practices. London, United Kingdom, and New York, United States: Routledge.

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., and Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: a systematic search and meta review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 675–689. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Vargas-Madriz, L. F., and Konishi, C. (2021). The relationship between social support and student academic involvement: the mediating role of school belonging. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 36, 290–303. doi: 10.1177/08295735211034713

Vincent, L. B., Openden, D., Gentry, J. A., Long, L. A., and Matthews, N. L. (2018). Promoting social learning at recess for children with ASD and related social challenges. Behav. Anal. Pract. 11, 19–33. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0178-8

Vygotsky, L. S., and Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard university press.

Woodgate, R. L., Gonzalez, M., Demczuk, L., Snow, W. M., Barriage, S., and Kirk, S. (2020). How do peers promote social inclusion of children with disabilities? A mixed-methods systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 2553–2579. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1561955

Keywords: relational inclusivity, social network analysis, social network analysis toolkit, social network perspective, students with special educational needs and disabilities, inclusion

Citation: Mamas C and Trautman D (2025) Defining and exploring relational inclusivity: attending to inclusion across four dimensions of schooling. Front. Educ. 10:1544512. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1544512

Edited by:

Israel Kibirige, University of Limpopo, South AfricaReviewed by:

Wills Kalisha, NLA University College, NorwayAnnika Fjelkner Pihl, Kristianstad University, Sweden

Copyright © 2025 Mamas and Trautman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christoforos Mamas, Y21hbWFzQHVjc2QuZWR1

Christoforos Mamas

Christoforos Mamas David Trautman

David Trautman