- 1School of Psychology, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC, Australia

- 2Excellence in Attendance Support, International Consultancy, Netherlands

- 3Samenwerkingsverband vo Zuid-Kennemerland, Haarlem, Netherlands

Background: Authorized absences often receive less attention from policymakers and researchers, despite having a similar impact to unauthorized absences. The GRIP study aimed to help a Dutch school district ‘get a grip’ on attendance by raising awareness of authorized absences and supporting improvements in attendance practices.

Method: Using an action research approach, two district-level consultants prioritized building trust with school staff, administrators, and district personnel to foster collaboration in the study. With the participation of 31 of the district’s 33 secondary schools, they accessed and analyzed absence data from the 2018/2019 academic year. A key step was standardizing absence categories across schools to gain a clearer picture of absences across the district. A launch event was held to communicate findings and start helping schools translate data insights into attendance improvement practices.

Results: Authorized absences accounted for 85.5% of all missed class time. Sickness/medical-related absences and school-initiated absences were the most prevalent, comprising 75 and 16% of all authorized absences, respectively. There was little evidence that schools responded to authorized absences prior to the current study. Through the collaborative process that characterized the GRIP study, schools became more aware of authorized absences and received support in implementing practices to improve attendance, sparking growing interest among schools in establishing an attendance taskforce of their own.

Conclusion: Schools have substantial influence over authorized absences, particularly school-initiated ones, offering opportunities to reduce unnecessary absences. Six key drivers for improving school attendance emerged from the consultants’ reflections: district-wide collaboration, trust-building through non-judgmental engagement, using data to trigger urgency, empowering schools with data-driven insights, applying a tiered approach to attendance, and adopting an adaptive approach for continuous improvement. Future research should focus on refining absence registration systems and incorporating qualitative methods to better understand authorized absences and improve interventions.

1 Introduction

Students’ presence at school provides educators with key opportunities to support learning, well-being, and readiness for adulthood (Heyne et al., 2024; Kearney et al., 2022). School absence – whether authorized or unauthorized – can disrupt this developmental process, affecting academic achievement (Keppens, 2023) and social–emotional well-being (Villadsen et al., 2024). The KiTeS framework (Melvin et al., 2019) highlights that school absence is shaped by interconnected factors, including school-level influences such as disciplinary procedures and support structures, as well as broader influences, such as cultural attitudes toward education and policies at local and national levels.

Efforts to improve school attendance continue to gain momentum, an important development given high rates of chronic absence (Chang et al., 2024). These efforts include fostering an inclusive school environment that supports students’ sense of belonging, well-being, and engagement (e.g., Grant et al., 2023; McNeven et al., 2023; Solberg and Laundal, 2024). At the district level, initiatives to support attendance are expanding, as reflected in a growing body of research (e.g., Balfanz and Byrnes, 2018; Boaler et al., 2024; Brown, 2023; Corcoran et al., 2024; Lavigne et al., 2021; Rychcik, 2023), with some specifically targeting secondary school students (e.g., Daniels, 2020). Meanwhile, countries worldwide are increasingly reviewing policies and practices that holistically address students’ educational, social, and emotional needs, including policies on attendance and school completion (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024).

Attendance and absence data1 provide essential insights as schools, districts, and authorities work to support students, promote attendance, and reduce absence. First, knowing who is present upholds schools’ safeguarding responsibilities, ensuring student safety (White, 2022). Second, data helps identify students struggling with attendance, enabling timely interventions within a multi-tiered support framework to prevent chronic absence (Heyne and Gentle-Genitty, 2024; White, 2022). Third, attendance data informs local and national policies and practices (Kearney et al., 2022; Kearney and Graczyk, 2022), influences resource allocation, and helps foster more inclusive learning environments (Heyne et al., 2022). The usefulness of attendance data depends on its quality and completeness (Kearney and Childs, 2022), and on how absences are categorized.

1.1 Authorized and unauthorized absences: the dominant dichotomy

Schools often classify absences as authorized (excused) or unauthorized (unexcused). Authorized absences include those the school deems acceptable based on satisfactory explanations, such as sickness, medical appointments, and religious events, as well as school-approved term-time holidays, while the unauthorized absences cover unexplained or unapproved absences such as truancy and unapproved term-time holidays (Dräger et al., 2023; Hancock et al., 2013; Karel et al., 2022).

Research on the impact of school absence often focuses on total absences, but a smaller body of work has examined the distinct effects of authorized and unauthorized absences. Early studies suggested that unauthorized absences are more harmful to academic achievement than authorized ones, based on findings from primary-aged students in the US (Gershenson et al., 2017; Gottfried, 2009; Pyne et al., 2023) and both primary- and secondary-aged students in Australia (Hancock et al., 2013). These findings are thought to have contributed to the predominant focus on unauthorized absences in research and policy (Dräger et al., 2024; Klein et al., 2024; Weathers et al., 2021). A report on post-pandemic education policy, drawing on survey data from 26 countries, supports this view, noting that while absences due to illness increased during and after the pandemic, unjustified absences remain a common concern for countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024). Reflecting this, the survey itself focused on policies and practices addressing unauthorized absences, reinforcing the longstanding prioritization of unauthorized absences over authorized absences.

More recent research based on UK data suggests that both authorized and unauthorized absences throughout primary and secondary school are equally harmful to students’ performance at the end of compulsory schooling (Dräger et al., 2024). In fact, both authorized and unauthorized absences negatively impact educational attainment similarly across each year of schooling (Klein et al., 2024). Even moderate levels of authorized and unauthorized absences negatively affect academic progress (Dräger et al., 2023), and authorized absences in secondary school and at the end of primary school are more harmful to achievement than authorized absences earlier in primary school (Dräger et al., 2024).

Beyond broad comparisons of authorized and unauthorized absences, some studies have examined the effects of different types of absences within these categories. For example, research on secondary school students found that both authorized absences due to illness and unauthorized absences due to truancy lowered the likelihood of students pursuing further education after school (Klein and Sosu, 2024). Another study of secondary school students found no difference in educational outcomes between authorized absences due to illness or domestic circumstances (e.g., a family crisis) and unauthorized absences (i.e., truancy) at the end of compulsory and post-compulsory schooling (Klein et al., 2022). These findings suggest that authorized and unauthorized absences can have comparable impacts, reinforcing the need for further research into each, as emphasized by Panayiotou et al. (2021).

1.2 Inconsistencies in the recording and reporting of authorized and unauthorized absences

There are inconsistencies in how authorized and unauthorized absences are recorded and reported, both across and within countries (Heyne et al., 2022). These inconsistencies stem not only from differences in national policies but also from variations within regions, between schools, and even among individual staff responsible for documenting and managing absences.

Despite schools receiving official guidance on how to record authorized and unauthorized absences (e.g., Griffiths et al., 2022), variations persist. Some schools enforce stricter policies on term-time family holidays than others (Hancock, 2019), and even within schools, principals may treat absences of high-performing students more leniently (Keppens, 2023), such as by classifying certain absences as authorized that would otherwise be recorded as unauthorized for other students. In the UK, absences related to emotional distress are typically considered authorized but are sometimes recorded as unauthorized (Lester and Michelson, 2024). School staff also report difficulties in accurately classifying absences as illness, COVID-19 isolation, or emotion-based school absence (Ward and Kelly, 2024). In the US, definitions of habitual unauthorized absences vary by state, and schools often apply their own unofficial criteria (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2014). Additionally, tracking methods for unauthorized absences likely differ considerably across states (Conry and Richards, 2018).

Reporting requirements also vary. Some authorities mandate reporting all absences exceeding a certain threshold, while others focus only on unauthorized absences (Heyne et al., 2022). In the Netherlands, unauthorized absences must be reported if they exceed 16 hours in four weeks, while authorized absences are only reported under specific circumstances (Karel et al., 2022). As a result, there is no national register of authorized absences and little published data on their prevalence. However, a report from four municipalities suggests that long-term authorized absences are eight times more common than long-term unauthorized absences (Ingrado, 2023).

These inconsistencies in recording and reporting affect attendance management at school and district levels. The underestimation of the prevalence and impact of authorized absences can delay essential support (Karel et al., 2022) and contribute to inequitable interventions by skewing perceived needs for support. Municipalities may also be uncertain about their role in addressing long-term authorized absences, as the legal framework is unclear and seemingly absolves them of this responsibility (Ingrado, 2023). More reliable data on authorized absences is needed to better understand the issue and ensure appropriate support.

1.3 Illuminating school-initiated authorized absences

Authorized absences include those initiated by the school. Common examples are temporary removal from class (in-school suspension), temporary removal from school (out-of-school suspension), and permanent removal from school (expulsion), which are used as disciplinary measures in response to behavioral issues (Heyne et al., 2019; Maag, 2012). These absences are collectively termed school-initiated absences (Kearney et al., 2019).

School-initiated absences take various forms beyond disciplinary measures. These can involve schools subtly encouraging struggling students to stay home during tests to protect the school’s academic performance, pressuring parents to collect children early, or failing to adequately support students with diverse needs – such as autistic students – hindering their full participation (Cleary et al., 2024; Heyne et al., 2019). Additionally, class absences due to school-related activities, such as re-exams or mentoring, may be recorded as ‘absent’ or ‘present’ depending on school, regional, or national guidelines. For example, in the UK, specific codes classify off-site educational activities such as work experience, interviews, or sporting events approved by the school, with students counted as ‘present’ even when off school grounds (Griffiths et al., 2022).

School-initiated absences are notable for several reasons. First, although authorized by the school, they are often not in the student’s best interests (Cleary et al., 2024; Heyne et al., 2019). For example, out-of-school suspensions can reduce students’ engagement with school (Pyne, 2019), and, like unauthorized absences and those due to illness, absences due to school exclusion have been linked to lower academic achievement (Keppens, 2023). Second, exclusionary discipline disproportionately affects black and Latinx students (Weathers et al., 2021), reinforcing inequities in the education system. Third, while schools have limited control over some absences, such as those due to illness (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024), they have considerable control over school-initiated absences. Reducing these absences is therefore essential for schools and districts seeking to improve attendance to promote better outcomes for young people.

1.4 Summary and aims

Both authorized and unauthorized absences are linked to lower academic achievement. However, policies and research have often prioritized unauthorized absences. Meanwhile, school-initiated absences have received little attention, despite schools having more control over these absences from class. The current GRIP study contributes to the growing focus on district-level initiatives that proactively improve attendance by supporting all students and fostering a preventive approach to absence.

Commissioned and funded by the school district, the study was led by authors Inge Verstraete (IV) and Marije de Wit (MdW) and focused on secondary schools in a district in the Netherlands. Its aim was to help these schools ‘get a grip’ on attendance by raising awareness of authorized absences and promoting proactive attendance practices that support students and their development. This paper outlines the motivation, process, and progress of this district-wide initiative.

2 Method

Guided by a collaborative, context-specific problem-solving approach, the GRIP study focused on identifying and addressing all types of absences, not just unauthorized ones. The study embraced principles of action research to foster proactive and sustainable improvements in attendance practices, bridging the gap between research and the everyday realities of school practices (Edwards-Groves and Rönnerman, 2022; Manfra, 2019).

Conducted between November 2020 and October 2023, we outline the study’s context for change (2.1.1), the problem addressed (2.1.2), collaboration and communication among partners (2.1.3), working with secondary schools to systematically collect absence data (2.2.1), reflections on practices for recording absences, leading to a uniform system for classifying absences (2.2.2), data analysis (2.2.3), and actions taken to influence knowledge and practice in the school district (2.3). For further methodology details, refer to the report by Karssen et al. (2023), Grip op Geoorloofd Verzuim (Gaining Control over Authorized Absences).

2.1 Foundations for change

2.1.1 Study context

In the Netherlands, schools are legally required to record both authorized and unauthorized absences, but reporting requirements to the national service that administers education department regulations (DUO) primarily focus on unauthorized absences. Specifically, reporting is mandatory for unauthorized absences totaling 16 hours or more within 4 weeks, or continued unauthorized absences for four or more weeks. Authorized absences are reported only in specific cases, such as concerns about the duration and frequency of the student’s absences (Karel et al., 2022).

The GRIP study was conducted in South Kennemerland, an urban area in the west of the Netherlands. The Samenwerkingsverband vo Zuid-Kennemerland (Collaboration of Secondary Schools in South Kennemerland) is an association akin to a school district, including 33 secondary schools across six municipalities, seven of which are special education schools. These schools educate about 20,000 students at all educational levels, under the direction of 14 school boards.

GRIP study data covered the 2018/2019 school year, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and included both quantitative and qualitative data, although this paper focuses on the quantitative data.

2.1.2 Impulse for action

The impetus for the study arose from the role of consultants IV and MdV in assisting South Kennemerland schools with supporting students with special needs and their parents, in accordance with the inclusive education law. Over several years, they observed rising student absences, particularly for those reported as sick. Their interactions with schools revealed a troubling trend: while most absences were authorized, they were often prolonged, highlighting a gap in the existing legal framework’s focus on unauthorized absences.

Recognizing the need for a more comprehensive approach to address all types of absences, the consultants developed an absence policy and protocol in collaboration with community health services, youth and family services, youth health care and school doctors, care coordinators, and compulsory education officers. This guide, detailing roles and responsibilities at the first signs of absence, was disseminated across schools and relevant agencies in the district.

The consultants’ commitment to promoting attendance was further reinforced by attending the 2019 inaugural conference of the International Network for School Attendance (INSA), which underscored the importance of a preventive approach to attendance that engages all students, including those with authorized absences. At the conference, poignant messages from youth, such as “Do not let go of us” and “Safety is the key,” highlighted the value of inclusive attendance practices. The conference also deepened the consultants’ understanding of the crucial role of data for early intervention and supportive responses to absence.

These insights, coupled with the consultants’ earlier initiatives, culminated in the GRIP study, which they led as principal researchers. The study aimed to explore absence patterns and raise awareness about the importance of proactive district-wide practices for both authorized and unauthorized absences.

2.1.3 Partner engagement

To drive change, the consultants actively engaged key partners at all levels of the district’s education system. Historically, partnership development was informal and infrequent, relying on schools sharing information amongst themselves or through incidental consultations.

Employing an intentional and inclusive approach, the consultants built a broad coalition through strategic outreach. This coalition included decision-makers (directors from the district and school boards, and principals from the schools) as well as frontline professionals from 31 schools (team leaders, care coordinators, program counsellors, and administrative staff who provided absence data). The initiative was further supported by the Kohnstamm Institute and a data specialist. Study permission was obtained from the district’s director and board members, and the consultants made persistent efforts to align all partners with the study’s objectives.

Communication was key, with updates shared during biannual management and board meetings, as well as quarterly meetings with the district’s support coordinators. Discussions focused on the study’s status, timeline, expectations, and the individuals needed for upcoming steps.

2.2 Learning from the absence data

This section outlines the collection of absence data, the development of a standardized system for classifying absences, and the descriptive analyses used to identify absence patterns.

2.2.1 Accessing the data

To minimize the burden on schools, the consultants recruited a specialist in Dutch student administration systems. Her expertise ensured streamlined data collection from schools. Direct collaboration with the schools, characteristic of action research (e.g., Ward and Kelly, 2024), was essential for trust and cooperation. Consequently, data was provided by 31 of the 33 schools, representing 94% of the district’s schools.

Schools were asked for the following information: each occurrence of absence, whether it was deemed authorized or unauthorized, date of absence, who reported the absence, the stated reason for the absence, whether there was a response to the absence, and who was involved in the response (e.g., mentor, care coordinator, youth doctor, school attendance officer). Background information on students, including sex, the type of education they were enrolled in, and year level, was also collected to provide context.

The specialist accessed data through the Magister student administration system, used by most schools, and integrated data from the remaining schools using other systems. All data-related interactions followed strict protocols, including agreements to ensure data confidentiality and integrity. Files were secured, and data anonymized to protect student privacy.

After combining the schools’ datasets, the specialist began standardizing the data to address discrepancies (e.g., some schools recorded absences per half-day while others did so hourly).

2.2.2 Developing a uniform system for classifying absences

Recognizing inconsistencies in how schools recorded absences, including variations in the number and types of categories used, the consultants collaborated with the Kohnstamm Institute to develop a uniform classification system. The system was based on the SNACK screening instrument for school attendance problems (Heyne et al., 2019) and insights from the INSA conference.

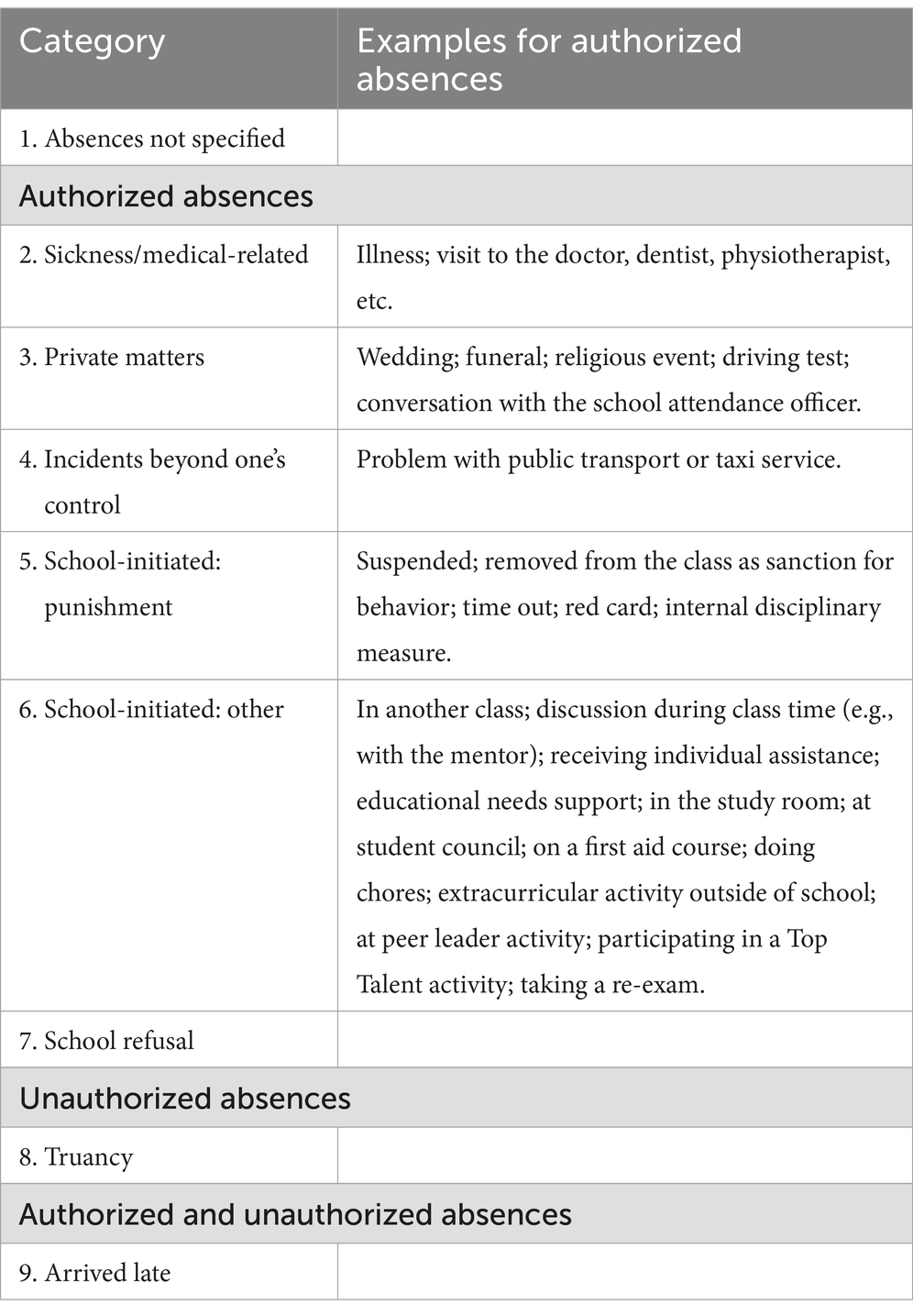

The nine categories, detailed in Table 1, covered both authorized and unauthorized absences, with examples in the table reflecting actual school data entries. These categories were established before re-classifying the schools’ data.

Several details about the categories are worth noting. ‘Absences not specified’ was used when no information was provided by the school regarding the absence. For ‘sickness/medical-related’ and ‘private matters’, the decision for the student to miss school typically came from the parent. ‘School-initiated: other’ was categorized as an absence because, although students were engaged in other school-initiated activities, they missed scheduled instructional time. The category ‘arrived late’ was not sub-categorized by the length of lateness, as schools did not provide specific data on how late students were.

In the next stage of data preparation, the consultants mapped each school’s absence categories to one of the nine standardized categories. For instance, a school with 12 different absence categories had them reclassified into the nine uniform categories. This process ensured consistent classification of all absences, regardless of the number or type of categories originally used by the schools.

In the final stage, the nine categories were classified as either authorized or unauthorized based on the definition provided by the current Compulsory Education Act of 1969 (Government of the Netherlands, 2021). Authorized absences were defined as those with a valid reason for not attending school, while absences that did not meet this criterion were classified as unauthorized, with the following clarifications. Schools generally classified ‘school refusal’ as authorized when a doctor or healthcare provider indicated a reduced capacity for attendance. The exceedingly small proportion of school refusal absences classified by schools as unauthorized (0.0008% of all school refusal absences) were excluded from the analysis. For ‘arrived late’, some schools classified late arrivals as authorized, while others deemed them unauthorized. Due to limited additional information (e.g., whether lateness was due to a dentist appointment), it was not possible to verify classifications independently. Therefore, we adhered to each school’s classification, labeling late arrivals as either authorized or unauthorized accordingly. The classification of absence categories as authorized or unauthorized is shown in Table 1.

2.2.3 Data analysis

The dataset for analysis included 1,526,062 data points, covering absence details (date, reason, whether the absence was authorized or unauthorized, who reported the absence, whether a response was made, and by whom) as well as student background information (sex, type of education, and year level). This extensive dataset was managed and analyzed using SPSS (IBM, 2021).

Given the exploratory nature of the study, the analysis focused on identifying patterns in absences across the district, laying the groundwork for actionable insights. Accordingly, descriptive statistics were applied to summarize overall absence rates, authorized absences, school-initiated authorized absences, and the frequency of responses to absences.

2.3 Engaging schools in action

To maximize the study’s impact in driving meaningful change across the district, the consultants employed three key strategies: communicating the study’s findings, supporting schools in translating those findings into actions, and creating a district-wide network to help schools develop and implement their own attendance taskforces. These strategies are outlined below, with their observed impact discussed in Section 3.3.

Study findings were communicated both before and during a launch event. Prior to the event, a summary of the research report was shared with district and school boards, including aggregated data across schools and anonymized school-level data (with the 31 schools identified numerically rather than by name).

The consultants organized a celebratory, collaborative launch event to both recognize the schools’ involvement in the study and build awareness and enthusiasm for improving attendance and managing absences. The event brought together a diverse group of participants, including representatives from the district and school boards, along with key staff from 26 of the 31 participating schools (84%). Attendees included 8 district personnel, 10 management members (6 school principals), 24 student support coordinators, 10 special needs coordinators, 6 behavior specialists, and the data specialist involved in the study. To foster an open and trusting atmosphere, school attendance officers and city council representatives were not present but were later informed of the study’s findings.

The event featured both theoretical and practical elements, beginning with an informative morning session followed by an interactive afternoon work session. During the morning session, dynamic presentations were delivered by the consultants, a research partner from the Kohnstamm Institute, and an international expert in school attendance. These presentations covered the study’s purpose, methods, key findings, the practical implications of data for improving attendance, and the pyramid framework for promoting attendance and reducing absence (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020).

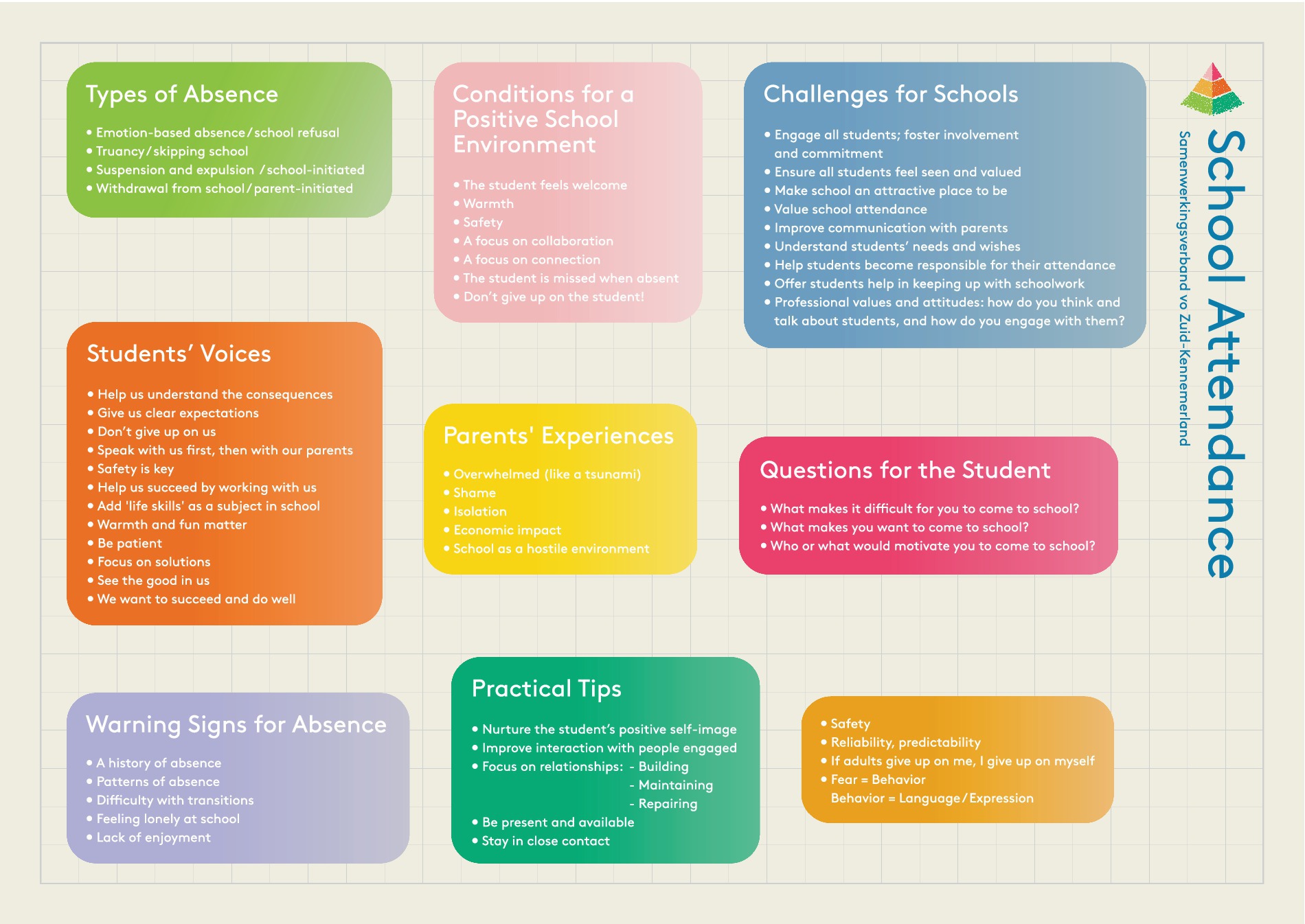

During a networking break before the afternoon session, participants received a comprehensive package containing: a research report with aggregated data across schools, a school-specific report with tiered data based on the pyramid framework, a digital copy of their school’s data, a template letter to parents emphasizing the importance of attendance, and a visually engaging poster highlighting key aspects of school attendance.

Designed as a quick-reference guide for school staff, this poster outlined various types of absence, conditions for a welcoming school environment, and challenges schools face in engaging all students. It also included key student and parent perspectives, thought-provoking questions for students about attendance, early warning signs of absence, practical tips for fostering positive relationships, and important safety considerations (Figure 1). This resource aimed to raise awareness and foster support strategies that promote student attendance and well-being.

In the afternoon, the consultants led a supervised work session that promoted active participation within and across school teams. They guided schools in analyzing their own data and identifying practical strategies to address attendance issues specific to their context. Each school received an individualized report, with data disaggregated by absence levels: Level 1 (students with 5% absence or less), Level 2 (students with more than 5% and less than 10% absence), and Level 3 (students with 10% absence or more). The pyramid framework, also known as the multidimensional, multi-tiered system of supports, helped schools understand student needs and allocate resources more effectively – providing school-wide interventions at Level 1, targeted support for emerging absences at Level 2, and intensive support for chronic absences at Level 3 (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020). Schools were encouraged to monitor attendance consistently throughout the year, paying particular attention to early-year data, as patterns in the first month of the school year often predict future absences (Attendance Works, 2023a). To ensure the session led to actionable outcomes, staff were encouraged to identify specific implementation steps upon their return to school. Ideas that were generated included discussing attendance during staff meetings and having principals greet students at the school entrance.

At the conclusion of the launch event, schools were invited to establish their own attendance taskforces. This would involve using their school-specific reports to develop and implement tailored attendance strategies aligned with their goals, participating in district-wide attendance network meetings held three times a year, and receiving ongoing consultant support as needed.

Following the event, schools were provided with a digital copy of the general research report for broader dissemination. Since June 2024, they have also been receiving attendance-themed newsletters to further support their efforts.

3 Results

This section reports on absence rates, starting with overall absences for context, followed by rates of authorized absences, including school-initiated authorized absences. ‘Rates’ refer to the proportion of class time missed over the school year, aggregated across students in the 31 secondary schools, unless otherwise specified. In addition, we report the frequency of schools’ responses to authorized absences and observations of the study’s impact on district-wide attendance initiatives.

3.1 Rates of absence

3.1.1 Overall absence

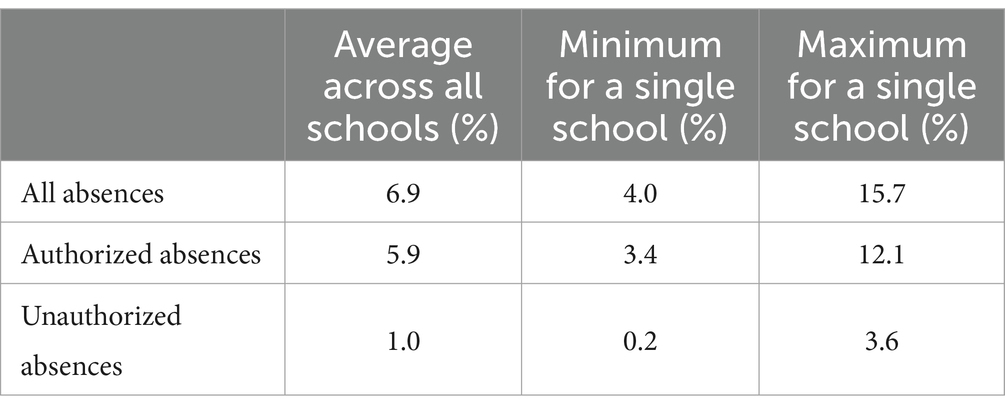

Students in the 31 secondary schools missed an average of 6.9% of class time during the 2018/2019 school year (see Table 2), roughly equivalent to 2 weeks of absence over the year. Notably, absence rates varied considerably across schools, ranging from 4.0 to 15.7%.

Table 2. Proportion of school time missed across students in 31 participating schools, relative to total possible school time during the 2018/2019 academic year.

When examining absence rates by sex, boys missed an average of 6.8% of class time, and girls missed an average of 7.1%. These sex-based averages are based on data from 30 schools, as one school did not provide sex-specific absence data.

The highest absence rates were observed among students in the 2nd and 3rd years of secondary school, at 7.4 and 7.5%, respectively, while the lowest rate was observed among 1st year students, at 5.5%.

3.1.2 Authorized and unauthorized absences

Among students in the 31 schools, 5.9% of class time was missed due to authorized absences, while 1.0% was missed due to unauthorized absences (Table 2). This means authorized absences accounted for 85.5% of the total missed class time (5.9% out of 6.9%).

Authorized absence rates varied considerably across schools, ranging from 3.4% at the school with the lowest rate to 12.1% at the highest. Similarly, unauthorized absence rates ranged considerably, ranging from 0.2 to 3.6% across schools.

When disaggregated by sex, girls had an authorized absence rate of 6.1%, while boys had a slightly lower rate at 5.9%. Unauthorized absence rates were 1.1% for girls and 1.0% for boys.

By school year, authorized absences were highest in the 2nd year of secondary school (6.7%) and lowest in the 6th year (5.1%). Unauthorized absences peaked in the 3rd year of secondary school (1.2%) and were lowest in the 1st year (0.5%).

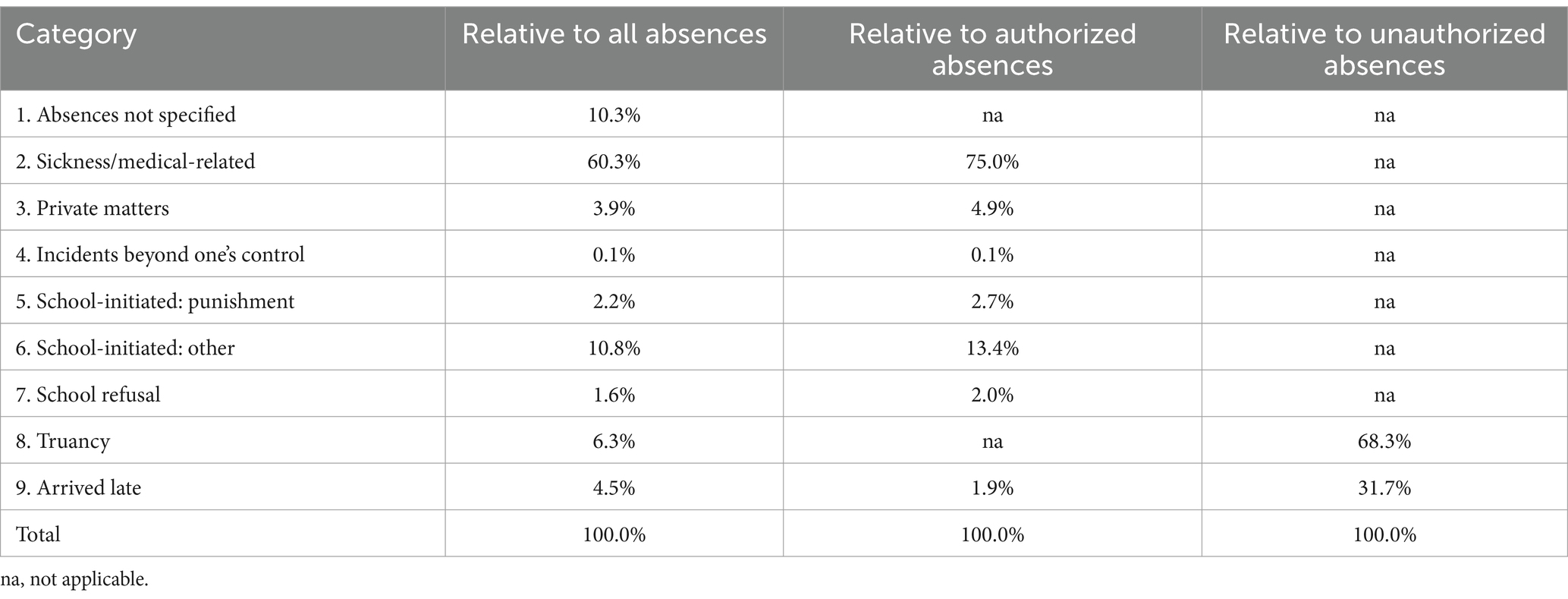

The breakdown of absence rates by category is provided in Table 3. Across both authorized and unauthorized absences, the most common categories were sickness/medical-related absences (60.3% of all absences) and school-initiated: other (10.8%). Among authorized absences, the two most common categories were sickness/medical-related absences (75.0% of all authorized absences) and school-initiated: other (13.4%). For unauthorized absences, truancy was the more prevalent of the two categories, accounting for 68.3% of all unauthorized absences.

3.1.3 School-initiated authorized absences

School-initiated absences, which were categorized as school-initiated: punishment and school-initiated: other, collectively accounted for 13.0% of all absences and 16.1% of all authorized absences (Table 3).

In regular schools, school-initiated absences represented 10.4% of all absences (i.e., both authorized and unauthorized), compared to 52.8% in special schools. In special schools, school-initiated absences were the most common category (52.8%), followed by sickness/medical-related absences (32.7%) and absences not specified (8.2%). In regular schools, sickness/medical-related absences were the most frequent category (69.8%), followed by absences not specified (11.7%) and school-initiated absences (10.4%).

3.2 Response to authorized absences

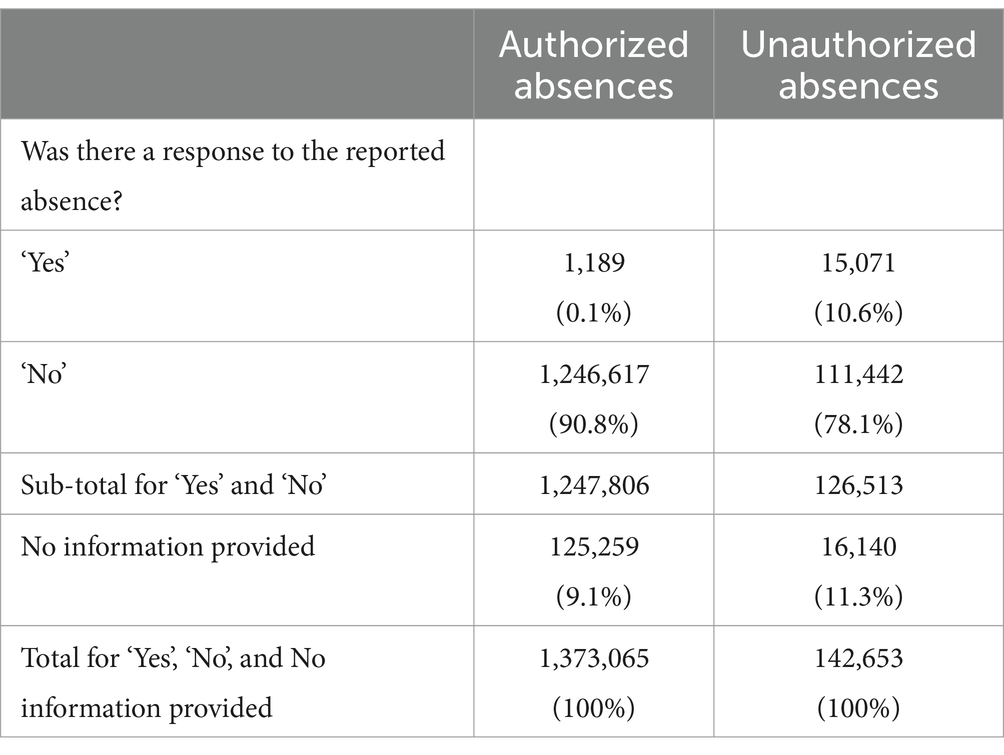

Across all schools, the vast majority of absences were not followed by any action (Table 4). Specifically, when considering all data, including instances where no information was provided about whether a response was made, approximately 9 out of 10 authorized absences (90.8%) went without a response, and approximately 8 out of 10 unauthorized absences (78.1%) also received no response. When looking only at instances where schools clearly indicated whether a response was made following absence (i.e., excluding instances of absence where no information about a response was provided), nearly 100% of authorized absences (1,246,617 out of 1,247,806) and 88% of unauthorized absences (111,442 out of 126,513) were not acted upon.

Table 4. Frequency (and percent) of responses to authorized and unauthorized absences, including instances with no information about whether there was a response.

We also examined responses to absences separately for special and regular schools, using data not presented in Table 4.

For the 7 special schools, there was limited information regarding whether any action was taken in relation to absence. Of the 139,137 data points across the fields ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘no information’, 99.4% (n = 138,329) fell into the ‘no information’ category. The remaining 0.6% of data points (n = 808) indicated that no action was taken in response to unauthorized absences. Notably, there were no data points indicating that these schools responded to authorized or unauthorized absences.

In contrast, data from regular schools was more complete, with only 0.2% of data points indicating ‘no information’ about whether a response was made. For authorized absences, just 0.1% of data points indicated that ‘yes,’ action was taken, while 99.7% indicated ‘no’ action. For unauthorized absences, 11.9% of data points indicated that ‘yes,’ action was taken, whereas 87.9% indicated ‘no’ action was taken.

3.3 Observed impact of the GRIP study on school attendance initiatives in the district

The consultants leading the GRIP study observed a notable impact on school attendance initiatives across the district.

A significant ‘shock effect’ occurred when the study’s findings revealed previously unnoticed absence patterns to school staff. This revelation, facilitated by the study’s comprehensive strategy for disseminating findings, was instrumental in establishing school attendance as a priority for schools. As a result, the consultants found it easier to introduce strategies aimed at reducing absences and promoting student engagement. Furthermore, school attendance is now a standing item in the district’s annual management meetings, where discussions focus on fostering open communication and strong collaboration between the district and schools to ensure coordinated efforts in addressing attendance-related challenges.

This prioritization has already led to concrete actions across multiple schools. Since the launch event, the consultants have supported five schools in establishing their own attendance taskforces, with two additional schools expressing interest. These schools are receiving assistance in using their data reports to develop actionable strategies for attendance improvement. One school, for example, is updating its student information system to strengthen its capacity for data-informed decision-making about attendance improvement. In addition, the district is offering financial support to schools interested in launching projects to improve their data use, with plans to extend successful initiatives across the district.

A key aspect of the consultants’ ongoing efforts is to keep school attendance a priority across the district. In their consultations with schools, they emphasize the importance of the issue by posing the question: ‘Why is this so important to us?’ Through regular themed newsletters on new developments in the field of attendance, such as strategies for increasing parent involvement, they help maintain a district-wide focus on attendance improvement, sustaining the momentum generated by the GRIP study.

4 Discussion

The district-wide GRIP study focused on raising awareness of authorized absences in secondary schools and fostering a proactive approach to attendance.

4.1 Summary, interpretation, and implications

In this section, we summarize the key findings, interpret them in relation to existing literature, and consider their implications for policy and practice. Additionally, we consider how absence classifications can reflect or reinforce broader systemic factors, influencing educational equity.

4.1.1 Rates of authorized absence

Authorized absences were the primary contributor to student absence in our district’s secondary schools, accounting for 85.5% of missed class time in the 2018/2019 school year. Specifically, of the total 6.9% of class time missed, authorized absences constituted approximately 5.9%, while unauthorized absences accounted for the remaining 1.0%.

Comparing authorized absence rates across studies is challenging due to variations in classification criteria, data collection methods, student populations (e.g., different ages), timeframes (e.g., absences measured over a school year or term), and contextual factors (e.g., data collected pre- or post-pandemic). Despite these differences, findings from other studies can still offer some valuable perspective. For instance, while authorized absences constituted 54% of absences in lower secondary education (ages 12–15) in Western Australia (Hancock, 2019), we found that authorized absences made up 85.5% of all missed class time in secondary schools (ages 12–18).

The high proportion of authorized absences across our district’s secondary schools highlights the need for greater attention. Prior research indicates that both authorized and unauthorized absences negatively affect academic achievement, sometimes to a similar degree (Dräger et al., 2024; Klein et al., 2024). While policy and interventions often focus on unauthorized absences, studies suggest that even moderate levels of authorized absence can lower academic performance (Dräger et al., 2023). Developing effective policies and practices can help ensure that all forms of missed instructional time – including authorized absences – are appropriately addressed.

At the national level, policies in the Netherlands focus primarily on unauthorized absences, as schools are currently required to report only unauthorized absences to the national database, while the reporting of authorized absences is not obligatory (Karel et al., 2022). This means that a substantial portion of missed instructional time due to authorized absences is overlooked by authorities, and potentially also by districts and schools. National policies should be revised to require schools to record both authorized and unauthorized absences with equal detail, supported by uniform reporting standards for both types of absence. This more comprehensive approach would enhance the understanding of overall attendance patterns and support the development of more effective interventions.

At the district policy level, education authorities should mandate the inclusion of authorized absences in early warning systems, ensuring that frequent absences – regardless of classification – trigger structured, supportive interventions rather than being overlooked. By establishing clear policies, education authorities can ensure a uniform and proactive approach to identifying students with recurring authorized absences, allowing barriers to attendance to be addressed before they escalate.

At the school policy level, administrators should reassess attendance protocols to ensure that authorized absences are addressed as rigorously as unauthorized ones. Protocols should emphasize that the primary aim of recording attendance and absence is not just compliance but the early identification of students and families who may need support to address barriers to attendance. Schools can also implement mandatory staff training to help educators distinguish between different causes of authorized absences (e.g., illness, mental health challenges, and family obligations), ensuring consistent application of absence codes and helping staff recognize patterns of authorized absences as potential indicators of broader issues requiring intervention.

At the school practice level, schools should work to raise awareness of the cumulative impact of absences – regardless of the reason – on student engagement and learning. Also, frequent authorized absences may signal deeper concerns, such as health problems or disengagement from school. Schools should implement support systems to help identify and address these challenges, ensuring that staff can respond effectively when patterns of absence suggest an underlying need for support.

By embedding these measures into national, district, and school-level policies and practices, education systems can move toward a more balanced approach to attendance management, ensuring that all types of absence receive appropriate attention and response.

4.1.2 Sickness/medical-related authorized absences

Sickness/medical-related absences accounted for 75% of all authorized absences and were the most common category of absences – authorized or unauthorized – in this study of secondary school students. A similar pattern was found in Dutch primary schools, where 75% of students in regular schools and 71% in special education were reported sick at least once during the school year (Pijl et al., 2021a). This consistency across primary and secondary schools suggests that sickness/medical-related absences represent a significant public health concern within the education system.

Although sickness/medical-related absences are often perceived as less problematic than other types of absence, they are linked to lower academic achievement and can act as a barrier to student success (Hancock, 2019). Students who miss school due to illness may be motivated to catch up on missed work (Keppens, 2023), and teachers and parents may be more supportive of these students than they are of students with other absences (Klein et al., 2022), yet an accumulation of sickness/medical-related absences can still hinder academic progress. To minimize this, Klein et al. (2022) recommended additional school-based support, such as tutoring during and after school, along with strengthening parents’ home-based involvement by providing guidance on helping children keep up with schoolwork.

Beyond academic concerns, sickness/medical-related absences warrant close attention for other reasons. They may indicate underlying health concerns, including mental health challenges (Klein et al., 2022). Interviews with secondary school students suggested that absences recorded as sickness/medical-related are not always due to illness or medical appointments but may stem from family problems, peer conflicts, dissatisfaction with lessons, school disengagement, or simply a preference to do something else during school hours (Vanneste-van Zandvoort, 2015). Additionally, parents may report sickness/medical-related absences to mask other factors, such as family difficulties or a child’s reluctance to attend school (Kearney, 2003; Reid, 2014; Thambirajah et al., 2008).

These findings and perspectives highlight the need for a dual approach – one that provides educational support while also uncovering and addressing the underlying reasons for absences reported as sickness/medical-related. According to Vanneste-van Zandvoort (2015), responding to absence reports should not be a routine administrative task focused on verification and control but should involve meaningful engagement with students and parents to understand their experiences. School staff should take a proactive role in these conversations, fostering open dialogue to uncover the real reasons behind reports of sickness-related absences.

Schools can further support families of students with frequent sickness/medical-related absences by providing targeted resources to ease transitions back to school. For example, Attendance Works (2023b) offers guidance to help parents determine when a child is well enough to attend. Additionally, schools can equip families with strategies to support students experiencing anxiety or other health-related attendance barriers (e.g., Parenting Strategies Program, 2022).

These family-level measures would complement broader school-based interventions aimed at reducing sickness-related absences and ensuring students receive necessary academic and well-being support. A structured, school-based approach to managing sickness-related absences is exemplified by the Medical Advice for Sick-reported Students (MASS) intervention (Vanneste et al., 2016). MASS focuses on early identification and systematic monitoring, with teachers encouraged to explore underlying reasons for absences (van den Toren et al., 2020). By fostering collaboration among students, parents, school staff, and healthcare providers, MASS seeks to address root causes of absences and lessen their impact on students.

This approach may be particularly relevant in contexts like the Netherlands, where any legal guardian can report a child as sick regardless of the underlying cause, reinforcing the need for structured systems that ensure sickness-related absences are appropriately monitored and addressed. Moreover, because secondary schools often have less flexibility than primary schools in adapting or repeating missed instructional content (Pijl et al., 2021b), structured interventions such as MASS are especially valuable at this level.

Preliminary evidence from two non-randomized studies suggests that MASS may help reduce sickness-related absences among adolescents and young adults. A quasi-experimental study in 14 pre-vocational secondary schools (VMBO) involving over 900 students found that sickness-related absences in the intervention group decreased, after 12 months, from 8.5 days during a 12-week period to 4.9 days, while the control group showed less improvement (Vanneste et al., 2016). Similarly, a controlled before-and-after study in eight intermediate vocational education schools (MBO) suggested that MASS may have reduced sickness-related absences and depressive symptoms among the older students (van den Toren et al., 2020). However, the researchers emphasized the need for a larger randomized controlled trial to confirm these findings.

The high rate of sickness/medical-related absences calls for a comprehensive response that includes not only school-based interventions but also supportive policies at national and district levels. National policies could mandate standardized criteria for reporting sickness-related absences to education authorities, ensuring consistency across schools and reducing the risk of misclassification. At the district level, education authorities could establish guidelines for schools to systematically monitor patterns of sickness-related absences and incorporate this data into district-wide attendance-tracking systems to identify trends and guide early interventions. Additionally, funding and policy support for structured interventions like MASS could help schools to move beyond simply recording sickness-related absences, ensuring they are met with timely and appropriate responses that address both academic and well-being needs.

4.1.3 School-initiated authorized absences

School-initiated absences were the second most common type of absence, comprising 13.0% of all absences and 16.1% of authorized absences. These absences were categorized into two types, namely school-initiated: punishment and school-initiated: other. Understanding the nuances between these categories is essential for developing effective policies and interventions.

The school-initiated: punishment absences accounted for approximately 2% of all absences in the study. While exclusionary disciplinary practices, such as suspension and exclusion, make up a small share of absences, they carry substantial implications for student engagement and equity. These practices disproportionately affect marginalized groups, including autistic students (Cleary et al., 2024) and racial and ethnic minorities, such as Black and Latinx students (Weathers et al., 2021), deepening existing educational inequities. The work of Cleary et al. and Weathers et al. underscore the need for schools to critically assess their disciplinary practices. Readers may consult the practical guide by Addis and Hawkins (2025) for an in-depth discussion.

At the school and district policy levels, clear guidelines should limit punitive exclusionary measures. Schools should be required to record and report school-initiated: punishment absences, making it possible to assess their impact on students and identify disparities across student groups. Districts should also provide professional development on alternative disciplinary approaches, such as restorative practices, which effectively address behavioral issues without excluding students (Grant et al., 2023). At the national level, policymakers should incentivize schools to replace punitive measures with inclusive, evidence-based alternatives and require them to demonstrate efforts to reduce exclusionary discipline.

The school-initiated: other absences accounted for approximately 11% of all missed class time and involved students missing class due to activities initiated by school staff, such as make-up tests, mentoring sessions, and enrichment activities like Top Talent. While these activities offer students opportunities for support and enrichment, poor scheduling can lead to substantial loss of instructional time and disengagement from class peers.

To minimize these risks, schools should carefully schedule such activities to support students’ academic and social–emotional needs without increasing class absence. Holding these activities during non-instructional periods reduces learning disruptions while maintaining peer engagement. Anecdotal evidence from a GRIP study school with low absence rates suggests that strategically scheduling mentoring sessions and make-up tests outside class time helps minimize disruptions to learning. The school coordinates school-initiated absences with students, parents, and relevant institutions, ensuring thorough documentation. This proactive approach minimizes the impact of missed classes by facilitating advance planning, enabling make-up work, and preventing scheduling conflicts for those students who already have significant missed class time.

Absence registration systems should distinguish between the two types of school-initiated absences: those related to punishment and those classified as ‘other’. This distinction would allow for more targeted interventions, enabling schools to address exclusionary discipline practices while also ensuring that non-punitive school-initiated absences are scheduled in ways that minimize instructional disruptions.

4.1.4 The response to authorized absences

We found that schools rarely responded to authorized absences. In regular schools, only 0.1% of authorized absences prompted action, compared to 12% of unauthorized absences. In special education schools, over 99% of the data lacked information on whether action was taken in response to absences.

If the data from regular schools accurately reflects school practices, it suggests a major oversight in addressing authorized absences. One contributing factor may be policies that prioritize reporting unauthorized absences over authorized ones (Karel et al., 2022), leading busy school staff to allocate resources accordingly. Additionally, the misperception that authorized absences are less problematic may lead schools to not respond to them systematically. Alternatively, if schools did respond to authorized absences but did not document their responses, the lack of documentation prevents them from assessing how absences are addressed and whether interventions are effective. This, in turn, limits their ability to refine interventions and provide appropriate support.

Schools may need to enhance their systems for recording responses to absences. Technology-driven intervention management can support accurate, real-time monitoring of absences and responses, reducing the risk of students slipping through the cracks due to inconsistent documentation (Heyne and Gentle-Genitty, 2024). This helps schools identify students experiencing challenges that may be overlooked because their absences are authorized and not scrutinized for underlying causes or impact.

Educational policymakers should emphasize the importance of responding to authorized absences to ensure underlying issues affecting student attendance are not overlooked. Supporting schools in adopting technology-driven attendance management systems and training staff in effective data management can help ensure a more comprehensive approach to student attendance and well-being.

4.1.5 The process of effecting change across the school district

The GRIP study aimed not only to analyze district-wide data on authorized absences but also to drive meaningful change in schools’ attendance practices. Achieving such change required a carefully coordinated, multi-year process focused on three key phases. In the initial phase, the study identified patterns of absence, providing schools with a clear understanding of the challenges they faced. The second phase built on this foundation, as the consultants worked with schools to develop and implement tailored strategies, translating data insights into practical actions to improve attendance. In the third phase, a district-wide network was established to help schools develop and manage their own attendance taskforces, ensuring ongoing collaboration and sustainability. These three phases illustrate how deliberate efforts over time can build the capacity needed to address attendance challenges. We identified six key drivers that contributed to the positive engagement and actions observed during these phases.

First, the collaborative approach adopted throughout the study was instrumental in driving change across the district. From the outset, the consultants engaged interested parties2 at multiple levels – including administrators from the district board and school boards, as well as management and key school staff – fostering inclusivity and a shared commitment to improving attendance. The consultants maintained an open-door approach, encouraging school staff to seek guidance and support, and to share ideas for the study. They also presented a summary of the gathered absence data to the district and school boards before the launch event, ensuring key decision-makers were informed and that the district, as the study’s financier, remained supportive. This broad engagement, from administrators to frontline staff, was essential in securing the support needed for the successful implementation of attendance improvement strategies.

Second, the consultants’ commitment to continuous communication and a respectful approach was crucial in building trust and maintaining schools’ engagement throughout the process. By maintaining personal connections, providing regular updates, and respecting school autonomy, the consultants further strengthened trust in the initiative. They consciously used non-judgmental language in their communication, which encouraged schools’ participation without defensiveness and fostered productive discussions about actively finding solutions for absences. By sharing school-specific data only with each school and its board, the consultants created a constructive atmosphere that encouraged reflection without fear of being ‘named and shamed.’ At no point were schools made to feel they were ‘doing it poorly’. This respectful attitude fostered a positive district-wide environment and ensured a low threshold for attending the launch event. The approach to engaging schools in the study mirrors the approach used to promote student attendance: fostering a safe, supportive, and inspiring environment that encourages active participation.

Third, as noted in the Results, the ‘shock effect’ drove immediate action among schools. Presenting school staff with previously unnoticed absence patterns in their own data heightened awareness and prompted a prioritization of attendance. This realization, particularly regarding high rates of authorized absence, led schools to quickly reassess their practices and explore new strategies. The urgency was likely amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which intensified attention to attendance issues.

Fourth, the interactive afternoon session empowered schools to take ownership of their data and start translating findings into practice. Schools could engage hands-on with their data, which fostered collaboration among school staff, reflection, and the development of actionable steps to improve attendance. This approach also encouraged innovation and the tailoring of strategies to each school’s unique context.

Fifth, applying the pyramid framework – introduced during the morning presentations and explored in the interactive afternoon session – gave schools a structured tool to analyze their school-specific attendance data. While the ‘shock effect’ heightened awareness of overall absence rates, the framework helped schools recognize the value of Level 1 universal interventions to promote attendance and Level 2 targeted interventions to efficiently address emerging absence issues, rather than focusing solely on Level 3 absences. Providing schools with their data within this framework allowed them to analyze absence patterns through the lens of these intervention levels, fostering deeper reflection on school-specific absence patterns and resource allocation. With this structured approach, schools could integrate the framework into their ongoing attendance strategies, improving their ability to monitor absence patterns and tailor interventions. Additionally, the framework supports continuous evaluation, enabling schools to refine level-specific interventions based on data-driven insights and maintain intervention effectiveness (Heyne and Gentle-Genitty, 2024). For further guidance on applying the pyramid framework at school and district levels, readers may consult detailed discussions in Heyne (2024) and Heyne and Gentle-Genitty (2024).

Sixth, continuous reflection and adjustment throughout the action research process contributed to its positive impact. By critically evaluating assumptions and strategies at each stage – from data collection to intervention implementation – the consultants remained responsive to challenges and adaptable to feedback. This iterative approach allowed for real-time refinements, ensuring strategies remained effective and aligned with schools’ evolving needs. It fostered a culture of learning and adaptability, essential for sustaining attendance programs (Heyne and White, 2024). The taskforces formed since the launch event demonstrate how the action research groundwork continues to support improvements in attendance practices. The consultants continue to raise awareness about attendance among school professionals, parents, and students, and they outline future actions through attendance-themed newsletters, reinforcing the long-term commitment to attendance initiatives.

Drawing from the key drivers described above, practical considerations emerge for districts seeking to develop and sustain meaningful change in attendance programs. A coordinated, multi-level approach – where district leaders, school staff, and other interested parties collaborate – ensures that commitment is reinforced and strategies remain aligned. Transparent communication across all levels of the school district, supported by dedicated facilitators such as attendance consultants, fosters trust and enables all parties to fulfill their roles effectively. Maintaining attendance as a priority across schools helps sustain schools’ focus and propels linked activities that build and maintain momentum over time. Providing schools with actionable attendance data enables informed decision-making and encourages reflection on effective interventions, ensuring schools actively engage in improving attendance practices. The use of the pyramid framework further supports a data-driven approach by guiding schools in tailoring interventions at different levels of support. Finally, an ongoing commitment to evaluation and adaptation ensures that attendance interventions remain responsive and effective in the long term.

A strong policy foundation is essential for effective and sustainable district-wide attendance programs. In this study, documentation gaps limited schools’ ability to fully understand attendance patterns and provide tailored support – approximately 10% of absences were classified as ‘absences not specified.’ Clear guidelines for categorizing and recording authorized and unauthorized absences and their sub-categories promote consistency across schools in tracking reasons for absences. This enables early identification of attendance concerns and timely intervention.

Beyond classification, policies should encourage district-wide collaboration and equip school staff with the resources and training needed to use attendance data effectively. Establishing collaborative platforms where schools share best practices and engage in joint problem-solving can further strengthen attendance outcomes across the district.

4.1.6 The systemic implications of absence classification

While this discussion has largely focused on the prevalence of authorized absences and efforts to improve attendance, it is important to consider how the classification of absences as authorized or unauthorized both reflects and reinforces broader systemic factors. Extrapolating from the KiTeS framework (Melvin et al., 2019), we recognize that the application of these labels and the responses they elicit are influenced by various factors, such as school disciplinary policies, cultural beliefs, perceptions of disability, and government regulations. For example, families from minority groups may be more likely to have their child’s absences classified as unauthorized (Rosenthal et al., 2020), potentially undermining their sense of belonging in the school community and exacerbating educational disparities. Conversely, families with greater social capital may frame absences in ways that lead educators to label them as authorized, shielding their children from stigma or disciplinary action. Thus, absence classifications do more than document absences – they shape how educators, families, and students respond to absences.

By understanding how these systemic influences affect absence classifications, educators and policymakers can work to ensure labels do not obscure deeper issues or disadvantage specific student groups. One step is to review how absence codes are applied within a district and train staff in cultural sensitivity and the voluntary/involuntary absence distinction described by Birioukov (2015). This distinction moves schools beyond deficit-based views of absences by recognizing that some absences stem from uncontrollable factors like poverty or health issues, and others reflect students’ avoidance of negative experiences with peers, teachers, or curriculum. Applying this framework helps schools identify root causes of absence, implement appropriate interventions, and ensure that absence records support equitable attendance practices rather than reinforcing existing inequities.

4.2 Strengths and limitations of the study

4.2.1 Strengths

This study has several notable strengths. First, by focusing on secondary schools, the study addressed attendance patterns often shaped by the developmental and educational processes that can make attendance more challenging for adolescents, such as increased independence, a more complex school environment, and rising academic pressures (Heyne, 2022). Second, the study achieved a high participation rate, with 31 of 33 schools (94%) in the district providing data. This coverage enhances the generalizability of the findings within the district and offers insights into authorized absences that may be relevant for other districts with similar characteristics. Third, the use of daily recorded absence data collected by school staff minimizes recall bias, contributing to the reliability of the findings. Additionally, the sustainability of school attendance initiatives across the district was supported by the establishment of a district-wide network for attendance taskforces.

4.2.2 Limitations

Despite its strengths, the study has limitations that warrant attention, including variation in absence categories across schools, potential inconsistencies in how schools applied categories, and the timing of data collection.

First, the study relied on school-defined absence categories, which varied considerably and required systematization to allow for combined analyses. Although the consultants developed a standardized classification system informed by the literature, they remained constrained by the data provided by schools, potentially leading to gaps in capturing certain absences. For example, some categories found in the literature, such as ‘school withdrawal’ – where parents intentionally or inadvertently withdraw their child from school for short or extended periods (Heyne et al., 2019) – were not included in the study because the concept is not recognized in school registration systems. As a result, the study cannot offer insights into the prevalence of school withdrawal within the district.

Second, how schools applied absence categories may have introduced bias in prevalence estimates. For example, some schools may have assigned sickness/medical-related absences based solely on a parent’s or student’s initial explanation without further inquiry, even in cases where other reasons for absence may have been relevant. This could have led to over- or underestimation of the true prevalence of certain absence categories.

Third, the study used data from the 2018/2019 school year, predating the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic significantly altered school attendance patterns (e.g., UK Department for Education, 2023), with research indicating shifts in parent and youth attitudes, such as parents becoming more likely to keep children home for minor illnesses or safety concerns (Hancock, 2023). Therefore, the patterns of authorized absences reported in this study may not fully reflect current patterns. While the findings offer valuable insights into pre-pandemic authorized absences, caution is advised when generalizing these results to the post-pandemic context.

4.3 Suggestions for further research

Future research would benefit from involving community partners, parents, and young people in the research process. While this study did not include these groups, their involvement in future research would provide valuable perspectives on authorized absences, particularly in identifying local solutions and tailoring interventions to meet the needs of specific student groups. Qualitative methods, such as interviews with students, parents, and educators, could be employed to uncover the underlying factors driving both authorized and unauthorized absences, providing richer insights that inform more nuanced strategies for supporting student attendance.

Enhancing absence registration systems is also essential for ensuring accurate and actionable attendance data. Researchers could collaborate with schools to refine these systems, such as by incorporating categories like ‘school withdrawal’. Finding the right balance in the number of categories is important: too many categories can discourage accurate data entry and increase inconsistency, while too few may limit valuable insights for educators and researchers (Nederlands Jeugdinstituut, 2024). Input from interested parties, including students, parents, and educators, is necessary to ensure that the categories are balanced in number, practical for support purposes, and compliant with legal requirements. A validation study, as suggested by Hancock (2019), could explore how schools apply decision-making rules for absence codes and whether these codes accurately reflect the reasons provided by parents and students.

The field of school attendance would also benefit from a more multidimensional approach to data collection. Relying solely on attendance and absence metrics offers an incomplete view of the students in our care. Future studies should incorporate additional data points, such as belonging, engagement, well-being, and progress in learning and development, to provide a more holistic understanding of students’ experiences (Heyne and Gentle-Genitty, 2024). Such a comprehensive approach would help schools identify students who may be physically or virtually present but not fully participating or progressing, enabling earlier interventions that address their identified needs.

5 Conclusion

This study contributes to emerging research supporting district-level initiatives to address attendance challenges. Our findings demonstrate that collaborative engagement with school staff, administrators, and district leadership, combined with strategic data use and frameworks like the pyramid model, can drive improvements in schools’ attendance practices.

By partnering with nearly every secondary school in the district, we highlighted the notable prevalence of authorized absences, including two types of school-initiated absences: those related to disciplinary measures and those where students typically remain at school but miss class time. Recognizing schools’ influence over these absences presents opportunities to reduce unnecessary class time missed. Schools can reassess their use of punishment-related school-initiated absences, and for other school-initiated absences, a distinction can be made between those that support students’ development and those that are avoidable or potentially detrimental. Strengthening absence registration systems and incorporating qualitative research methods could further enhance understanding of authorized absences and inform more effective interventions.

All absences, including authorized ones, offer opportunities to understand and support students and families holistically. By thoughtfully examining absences—considering their underlying causes and their impact on students’ academic and personal development—schools can proactively address barriers to attendance and foster a more supportive learning environment. Strengthening this approach through the effective use of data ensures that schools and districts can translate insights into meaningful action, reinforcing their shared commitment to cultivating attendance practices that benefit students’ presence, participation, and progress.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they belong to the school district and the schools within the district. The schools granted permission to use their data for this study but did not consent to sharing the data beyond the scope of the study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Inge Verstraete, aXZlcnN0cmFldGVAc3d2LXZvLXprLm5s.

Author contributions

DH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The Samenwerkingsverband vo Zuid-Kennemerland (Collaboration of Secondary Schools in South Kennemerland) funded the GRIP study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Markus Klein (Strathclyde Institute of Education at the University of Strathclyde, Scotland) for his valuable review of the sections addressing the relative impact of authorized and unauthorized absences. We also thank Esther Pijl (GGD West-Brabant, the Netherlands) for her insightful feedback, which enriched our discussion of sickness-related absences. Dr. David Heyne, in his capacity as a freelancer, received payment for his role in preparing and submitting this paper. This payment was made solely for professional services rendered in support of the manuscript’s development and submission and did not influence the research findings or the content of the paper. No other conflicts of interest are declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT) was used to assist in the editing of this manuscript, specifically for refining the clarity and flow of the text. All content edited using generative AI was reviewed for factual accuracy and plagiarism.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We use ‘attendance data’ to refer to school records of both attendance and absence, as is common practice. However, since the GRIP study focused specifically on recorded absences, we use ‘absence data’ when discussing analyses related to the study.

2. ^We use the term ‘interested parties’ instead of ‘stakeholders’ because the latter has been criticized for its colonial connotations.

References

Addis, S., and Hawkins, T. (2025). Improving attendance by reducing suspensions: A practice guide. Publication of the National Dropout Prevention Center. Available online at: https://dropoutprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Suspension-Practice-Guide_2025.pdf

Attendance Works. (2023a). Attendance awareness campaign update: drive with data from September! Attendance Works. Available online at: https://myemail.constantcontact.com/Attendance-Awareness-Campaign-Update-for-October-4--2023.html?soid=1123160561841&aid=2o216hzKrq0 (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Attendance Works. (2023b). Health handouts: help reduce health-related absences. Attendance Works. Available online at: https://www.attendanceworks.org/resources/health-handouts-for-families/ (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Balfanz, R., and Byrnes, V. (2018). Using data and the human touch: evaluating the NYC inter-agency campaign to reduce chronic absenteeism. J. Educ. Students Placed Risk (JESPAR) 23, 107–121. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2018.1435283

Birioukov, A. (2015). Beyond the excused/unexcused absence binary: classifying absenteeism through a voluntary/involuntary absence framework. Educ. Rev. 68, 340–357. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2015.1090400

Boaler, R., Bond, C., and Knox, L. (2024). The collaborative development of a local authority emotionally based school non-attendance (Ebsna) early identification tool. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 40, 185–200. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2023.2300027

Brown, J. M. (2023). Administrator perceptions in reducing chronic absenteeism in an urban midwestern school district. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?q=administrator+perceptions+of&id=ED645061 (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Chang, H., Chavez, B., and Hough, H. J. (2024). Unpacking California's chronic absence crisis through 2022–23: seven key facts [infographic]. Policy Analysis for California Education. Available online at: https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/unpacking-californias-chronic-absence-crisis-through-2022-23 (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Cleary, M., West, S., Johnston-Devin, C., Kornhaber, R., McLean, L., and Hungerford, C. (2024). Collateral damage: the impacts of school exclusion on the mental health of parents caring for autistic children. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 45, 3–8. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2023.2280718

Conry, J. M., and Richards, M. P. (2018). The severity of state truancy policies and chronic absenteeism. J. Educ. Students Placed Risk 23, 187–203. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2018.1439752