- 1Laboratory of Scientific Research and Educational Innovation, Regional Center for Education and Training Professions, Rabat, Morocco

- 2Innovation in Education and Training, Regional Center for Education and Training Professions, Rabat, Morocco

- 3Didactics and Pedagogical Innovation in Teaching Language Learning, Regional Center for Education and Training Professions, Rabat, Morocco

- 4Center for Education and Training Professions, Khénifra, Morocco

This study examines the perception of teachers in initial training teachers regarding the gender approach and its application in their pedagogical practices. The main research question and the secondary questions explore several aspects: teachers’ representations of the gender approach, their level of knowledge of this approach, their attitude toward gender equality, and the influence of gender and the subject taught on their teaching approaches. The study used a descriptive-analytical method with a sample of 196 trainee teachers (73% women, 27% men) from various disciplines and from the Regional Centers for Education and Training Professions of Rabat and Khénifra, Morocco, during the 2023/2024 training year. Data was collected using scale with six Likert levels, which evaluates teachers’ effectiveness in terms of gender knowledge, implementation of gender-sensitive pedagogical methods, and development of equality attitudes. The first axis focused on the knowledge and awareness of gender among trainee teachers and revealed that this element is above the “Somewhat Agree” level for the majority of participants. The same result, slightly lower, is noted for axes 2 and 3; which suggests that the trainee teachers in the sample are in the process of developing their representations and their own views on gender issues. Therefore, verifying the initial hypothesis regarding gender awareness and knowledge shows that the goal is not fully achieved. To strengthen the achievements of teachers, whether trainees or certified, continuous training remains the most effective means in this regard. Similarly, initial training should place more emphasis on the gender approach, especially in modules where this theme can be freely addressed, such as legislation and ethics, school life, and research methodology.

Introduction

Maximizing the potential of human resources is a key objective for countries seeking to build and strengthen their economies. At the heart of progress lies the individual. Mastery of skills and active engagement are vital for ensuring that development projects are both sustainable and effective. Given the social interdependence and complementarity between men and women, the advancement of societies depends on the inclusion, culture, and active participation of both sexes in all programs (European Committee for Equality between Women and Men [ECEWM], 1996). To fully optimize human resources and enable every individual to reach their potential, it is crucial to consider and include all members of society.

Various cultural and social determinants, coupled with women’s education and training inadequacies, low levels of education and, consequently, lack of skills, jointly reduce their employment prospects. They hinder their competitive advantage in labor markets to obtain jobs that meet the needs of the family and their desire to achieve a certain social status.

In its 2023 annual report and based on data as of October 1, 2022, the World Bank affirms that only 14 countries—all high-income economies—have achieved total legal parity and that if women have access in the field of work on equality with men, world growth could be doubled (World Bank Group, 2024). In accordance with the principle of parity between the sexes within society, concerns related to gender equality or what is commonly called the gender approach, have recently attracted great attention from those responsible for policies in the field of country development, particularly since the 1970s.

Historically, the term “gender” was first introduced in its conceptual sense as a “gender role” by New Zealand psychologist and sexologist John Money in a scientific article in 1955. The “gender approach” later emerged with the rise of feminist movements and the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal work The Second Sex in 1949. Throughout this book, the underlying belief is that no woman is bound by a predetermined destiny. Simone de Beauvoir, rejecting any form of determinism in human existence, explores both the reality of women’s subjugation and its causes, which, as she asserts, cannot stem from any natural order (Lundgren-Gothlin, 1996). Since then, incorporating the “gender approach” has become essential, fostering social development and contributing to improved living conditions across all aspects of life.

In its texts, the UN (Monusco, 2024) defines “gender” as the sociocultural construction of masculine and feminine roles, as well as the relationships between men and women. It refers to social functions that are assimilated and culturally ingrained. Gender is therefore shaped by power dynamics within a society and evolves over time, influenced by the environment, specific circumstances, and cultural differences. While deeply tied to cultural contexts, gender remains relative, varying across eras and societies, thus shaping perceptions of roles, abilities, rights, and responsibilities of both women and men. A gender-sensitive approach aims to ensure that the benefits of development are distributed fairly, rather than being concentrated among those who hold the most privileged positions and play the most valued roles. The use of the term “gender” gained prominence on the international stage following the declaration of International Women’s Year in 1975 and became further entrenched during the United Nations Decade for Women (1976–1985).

In 1979, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women called for the elimination of “all stereotypical conceptions of the roles of men and women at all levels and in all forms of education.” It became an international treaty in 1981.

Indeed, in many developing countries, there is growing recognition of the need to address the discrimination between men and women across various sectors—social, health, education, professional, political, and more—in order to achieve gender justice. Thus, awareness of gender inequality has prompted societal changes that have had both direct and indirect effects on the family structure, particularly for women. This shift has introduced the concepts of equity and parity between the sexes.

At the national level, Morocco has demonstrated its commitment to the institutionalization of the “gender approach” since the 2000s. Many important legal advances have been identified over the last two decades. These include the promulgation of the Family Code in 2004, the revision of which is planned in accordance with royal directives. Then, in 2006, Morocco adopted a national strategy for the promotion of equity and equality between the sexes through the transversal integration of the gender approach in development policies and programs (Kingdom of Morocco, State Secretariat for Families, Children and Persons with Disabilities, 2006). In addition, progress has been confirmed such as the recognition of Moroccan nationality through the maternal line; the introduction of article 19 of the 2011 Constitution concerning gender equality, the establishment of law 103-13 (Kingdom of Morocco, Ministry of Family, Solidarity, Equality, and Social Development, 2018, law no. 103-13 relating to fight against violence against women) to combat violence against women as well as legislation promoting the participation of women in political life and their representation at local and parliamentary levels.

Furthermore, in the field of education, the 2011 Constitution established the creation of the High Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR), as a body for good governance and scientific research which has in turn developed the Strategic Vision for the reform of the education system 2015–2030. The HCETSR has in fact insisted on the establishment of a school of equity and equal opportunities, one of its missions being “Strengthening education for gender equality and the fight against discrimination, stereotypes and negative representations of women in school programs and textbooks” [Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco, 2015: p. 68].

During the recent revision of curricula and school textbooks in Morocco, a gender perspective was incorporated with the aim of eliminating gender stereotypes, sources of discrimination, and biased representations in educational materials. Efforts were made to ensure that images of women and girls, both in texts and illustrations, are no longer primarily linked to the private and domestic sphere, while men and boys continue to be depicted in the public and professional realms.

Furthermore, the Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR) published the thematic report on gender equality in and through education, which analyzes the progress and challenges of this equality in the educational context. This report focused on the beliefs, attitudes and aspirations of families regarding the education of boys and girls; access to education; curriculum and school life; school environment and climate; quality of learning and external results of the education system based on the analysis of the professional integration of higher education graduates [Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco, 2024, p. 91].

In view of these advances in the inclusion of the gender approach into Moroccan public policy, it is surely essential to consider what is known in English as “gender mainstreaming.” This is, broadly speaking, the integration of the gender approach across the board. It is “a strategy to promote gender equality and advance women’s rights by infusing gender analysis, gender-sensitive research, women’s perspectives and gender equality goals into all policies, projects and institutions” [Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), 2004, p. 1–11]. Insisting on this fact means that there is no question of being satisfied with current results, even if they are encouraging, given that several shortcomings are still present. Even though girls’ enrolment has risen sharply, many inequalities still persist, especially in rural areas. The integration of a gender perspective in education prompts an important question: How is the gender approach being applied among trainee teachers in Morocco?

In this study, this research question is broken down into five sub-questions:

1. What are the representations of trainee teachers regarding the gender approach and its implementation in class?

2. Do trainee teachers have sufficient knowledge of the gender approach?

3. Have the trainee teachers developed attitudes of parity and equality between the sexes, through consideration of the gender approach?

4. Do the variables of gender and discipline taught affect the gender approach in the field of education in Morocco?

These are the research questions that underlie the present study. Indeed, as trainers and given our close link with the initial training of teachers, and even with their continuing training, we were called upon to measure the degree of impregnation of trainee teachers with the gender approach and the relevance of its implementation in classroom practice, in the sense that this would contribute to reducing inequalities based on gender.

We start from the hypothesis that trainee teachers are fairly aware of the effectiveness of teaching that takes into account the gender approach and seeks parity and equality of the sexes, and we will measure this in order to arrive at the need or not to introduce training in the gender approach within the initial training of future teachers.

Conceptual framework

The gender approach

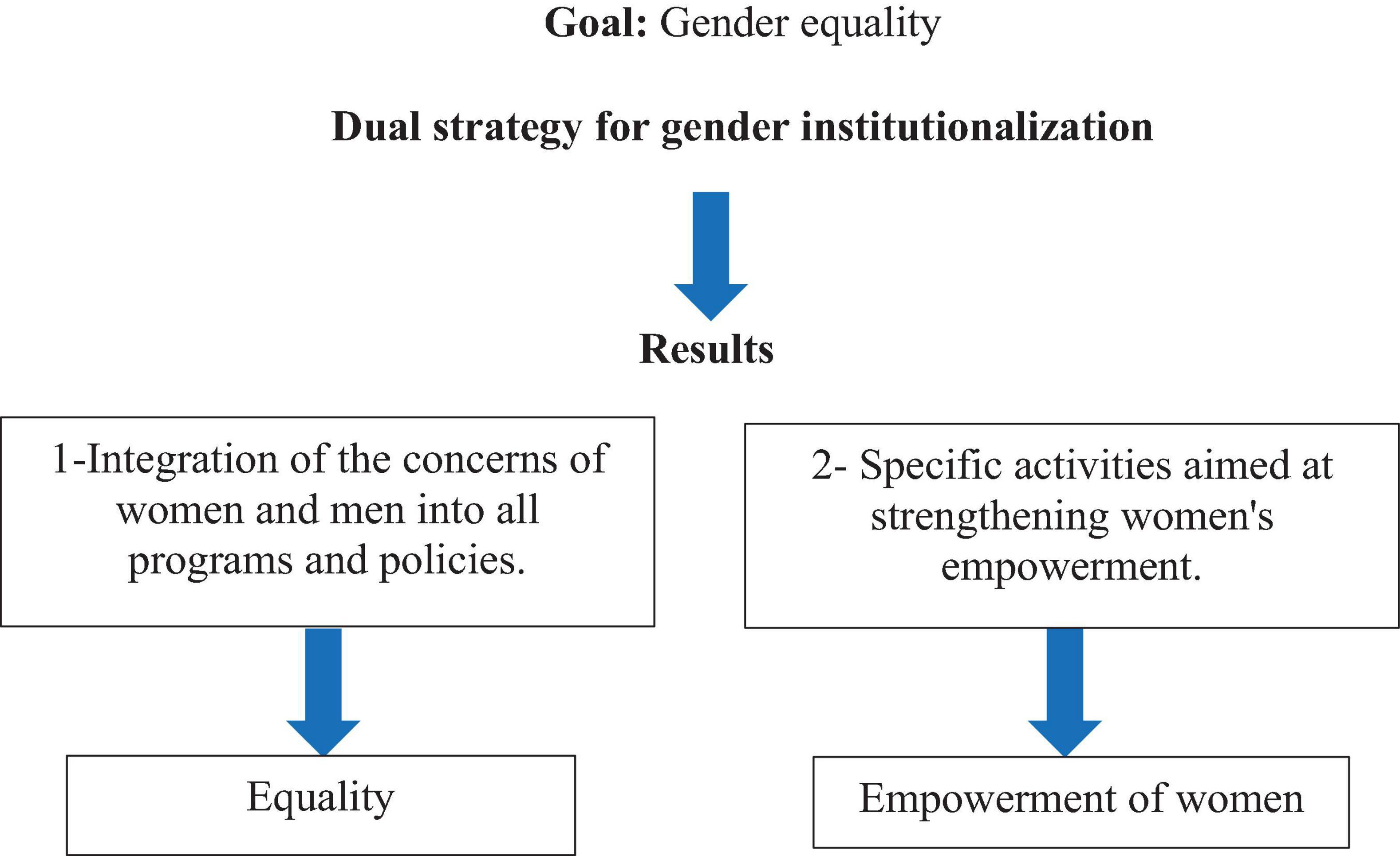

From the 1980s onward, the gender approach became a fundamental component of any initiative aimed at fostering the human development of a country or a community. This approach primarily emphasizes women’s rights and their active participation in their country’s economic development. Boserup (1970) highlighted the critical role of women in key economic sectors such as agriculture, industry, crafts, and commerce. During the 1980s, this concept evolved significantly, shifting from the issue of integrating women into development to the broader goal of gender equality [Québec Women and Development Committee (QWDC) of AQOCI., 2008]. This evolution marked a move toward the institutionalization of gender, as recommended by the fourth United Nations World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995. The action plan adopted at this conference strongly advocates for gender equality and the empowerment of women. This vision of things refers to two fundamental objectives schematized by the Quebec Association of International Cooperation Organizations–AQOCI, based on the work of Moser (2005), as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gender institutionalization strategy [diagram produced by the Quebec Association of International Cooperation Organizations—AQOCI based on the work of Moser (2005)].

This diagram clearly shows us that the gender approach affects two issues which have the same focal point, namely women. The first reflects on equality between men and women at the level of public policies and the second considers the possibilities of women’s empowerment; that is to say, more freedom of action for the latter. Such perspectives can, of course, only be implemented through education and teaching.

Education according to the gender approach

The revision of several codes by Moroccan legislation in this case the commercial code in 1996, civil status code in 2002, the labor code in 2003 (Sabbar, 2021, p. 103) was crowned by the establishment of the reform of the Kingdom of Morocco (2018) which stipulates that: “Man and woman enjoy, equally, rights and freedoms of a civil, political, economic, social, cultural and environmental, set out in this title and in the other provisions of the Constitution, as well as in international conventions and pacts duly ratified by the Kingdom, in compliance with the provisions of the Constitution, the constants and the laws of the Kingdom. The Moroccan State works to achieve parity between men and women. For this purpose, an Authority for parity and the fight against all forms of discrimination is created” (Kingdom of Morocco, 2011, article 19).

This legislative dynamic has led to deep reflection in relation to the field of education and teaching. The education of women, which was initially a discussion led by the cultured elite, has since become a public affair of a social nature. Thus, “the demand for the girl’s right to education was unanimous and constituted a lever for socio-political change among the female and male elite inspired by modernism” (Benadada and El Bouhsini, 2015).

This change in thinking regarding the education of girls is echoed in the National Charter for Education and Training (Special Education Training Commission-Morocco, 1999, p. 16) when it emphasizes the education of girls in general and those living in rural areas in particular by pushing stakeholders to:

make a special effort to encourage the schooling of girls in rural areas, by remedying the difficulties which continue to hinder it. In this context, it is imperative to support the generalization plan with local, operational programs for the benefit of girls, by mobilizing all partners, particularly teachers, families and local stakeholders.

This same concern is generally reflected by the majority of programs of the Ministry of National Education such as the emergency program, the medium-term strategic action plan for the institutionalization of gender equality in the education system 2009–2012 etc.

These strategies and plans in favor of girls’ education essentially aim to implement the following elements:

Equal rights between men and women: This equality has been promoted in the field of education and therefore within society. Indeed, this process began in Morocco from the first moments of independence and took off toward the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century. This momentum finds its explicit expression in the national charter for education and training. Thus, under the title “Rights and duties of individuals and communities” we read the following,

The education and training system works to realize the principle of equality of citizens, of equality of opportunity which are offered to them and the right of all, girls and boys, to education, whether in rural or urban areas, in accordance with the constitution of the Kingdom (Special Education Training Commission-Morocco, 1999, p. 9).

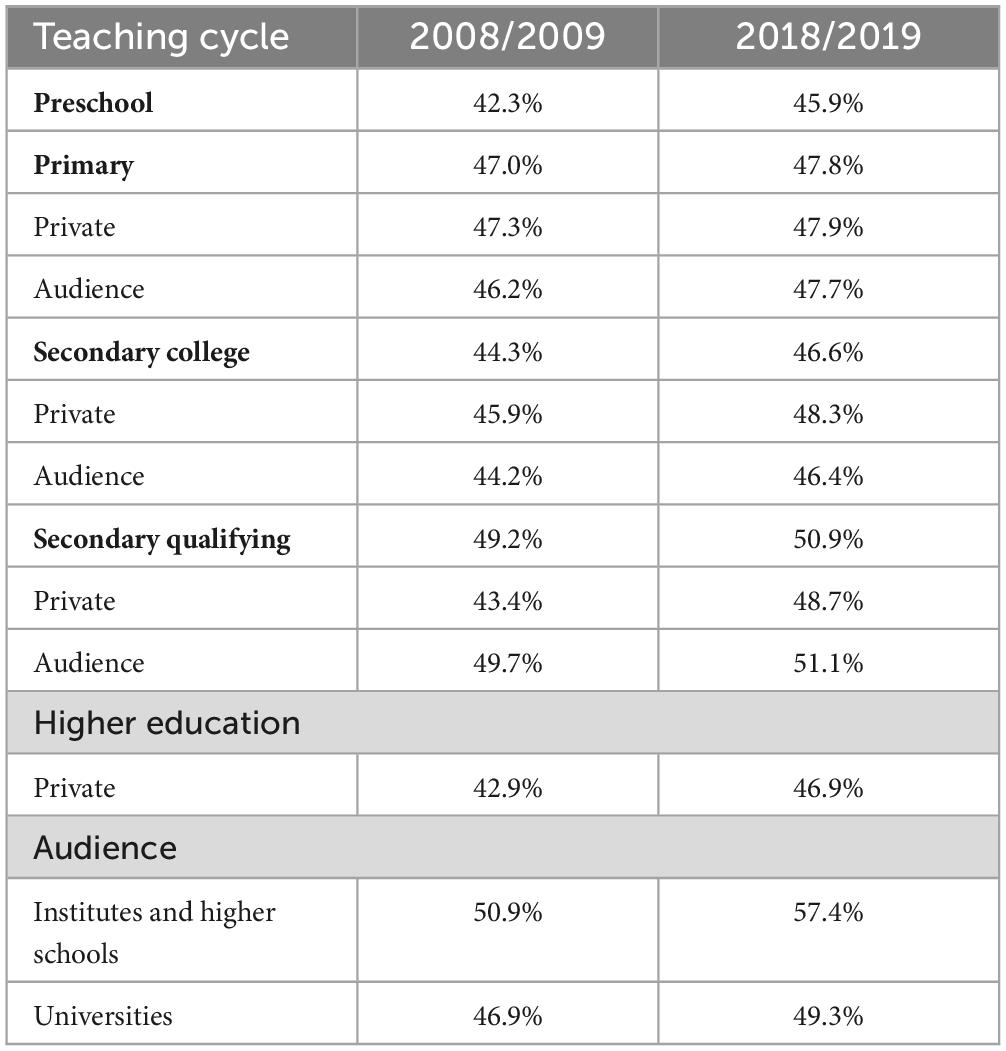

In this way, the national education reform launched the first milestone in the quest to eliminate disparities between boys and girls in their right of access to school. It is about strengthening the educational opportunities of girls and helping them acquire their right to education on the same footing as boys. These efforts were fruitful and the enrollment rate of girls at all levels, primary, lower secondary, qualifying secondary and higher education, experienced a notable breakthrough (Table 1).

Table 1. Feminization rate (in%) of those enrolled in the different education cycles according to the High Commission for Planning (HCP)-Morocco (2020: 51).

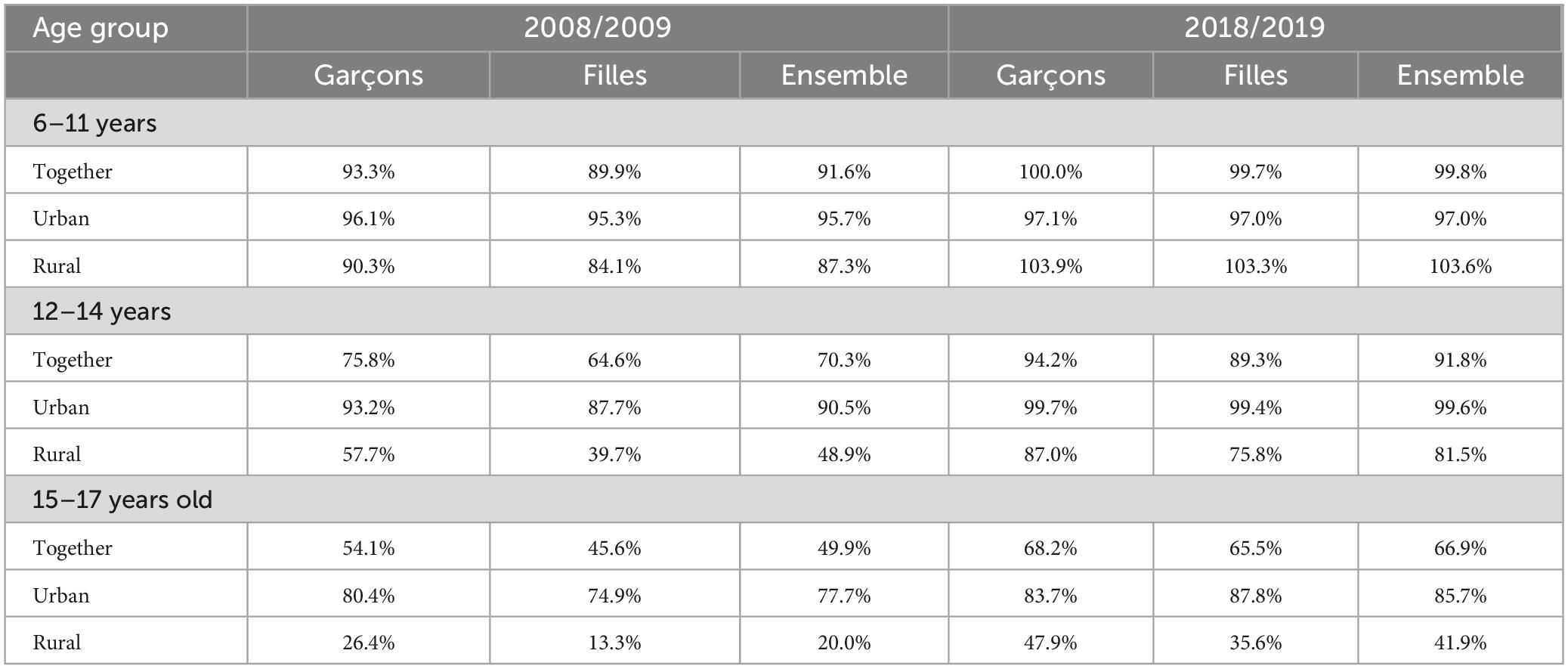

Equal opportunities and parity: This interest in the education of girls has led to a clear improvement in their chances of continuing their studies and assuming several responsibilities within society. The High Commission for Planning (HCP)-Morocco (2020, p. 49) specifies that the schooling rate of girls, especially in urban areas, is approximately close to that of boys, while in rural areas the schooling rate of girls has not yet reached the desired score (Table 2).

Table 2. Specific schooling rates (in%) according to age according to the High Commission for Planning (HCP)-Morocco (2020: 49).

Research methodology

Research design

The descriptive-analytical design was adopted to direct the analysis aimed at identifying the representations of trainee teachers concerning the gender approach, their implementation in class, as well as their correlation by sex of the participants and by discipline taught.

The participants

Simple random sampling was used for 196 Moroccan trainee teachers undergoing initial training, ensuring balanced representation of the main disciplines taught in Moroccan school education. Subject selection was based on the structure of the Moroccan school system, which is divided into two cycles, primary and secondary. Trainee teachers were selected from three key fields, primary education, science teaching and language teaching (French). It’s important to note that the CRMEF’s primary teacher training program covers all disciplines. In contrast, the secondary cycle is focused on a disciplinary approach, with a few cross-disciplinary modules relating to school life and the ethics of the profession. These trainees completed their training in the Regional Center for Education and Training Professions (RCETP) of Rabat and Khenifra cities, Morocco, during the 2023/2024 training year. Our sample is made up of three groups representing different disciplines including, sciences at qualifying secondary level (100 participants), French language at qualifying secondary level (47 participants) and primary education (49 participants). Among them, 53 (27%) are male trainee teachers and 143 (73%) are female. All participants who completed the questionnaire were fully informed of the study objectives and procedures prior to participation. Thus, participation was voluntary and anonymous. There was no incentive to take part in the study. Out of a total of 330 trainees, 196 responded to the questionnaire, which represents 60% of the three groups. The participants in the sample belong to an age range between 21 and 29 years old with an average of 24.04 years old (SD = 2.24).

Instrument and procedure

The Teacher Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice (TEGEP) scale by Miralles-Cardona et al. (2021) was used to collect data from participants. All sections of the instrument were first translated into Arabic by translation experts. We then reviewed the Arabic version of the instrument, making corrections to ensure maximum consistency with the original version.

The questionnaire consists of 26 items divided into three subscales: (a) effectiveness in knowledge and awareness of gender (11 items), (b) effectiveness in implementing gender-sensitive teaching methods (10 items) and (c) effectiveness in the development of gender attitudes (5 items). The question statements begin with one of the expressions “I can.”, “I have confidence.”, and “I am.”, respectively for the three subscales.

Responses are rated on a six-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” High scores on the TEGEP reflect a very positive perception of participants’ self-efficacy in implementing a gender perspective in their professional career. In the present study, the TEGEP scale showed very high reliability (the alpha coefficient for the entire scale was 0.92).

The research was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. After being informed of the objectives of the study, its voluntary character and the anonymous nature of the questionnaire, potential participants were invited to take part by giving their informed consent. Participants were expressly warned to read each item in the questionnaire carefully and respond truthfully. The questionnaire was administered via Google Form, and the link was shared in trainee teacher groups on WhatsApp. This process took approximately 20 min.

The limitations of this research lie in the fact that most participants took approximately one week to complete their responses to the questionnaire. This suggests that potentially some were able to exchange ideas regarding this subject with their colleagues or consult the internet before providing their answers, which could influence the reliability of their responses.

Processing of collected data

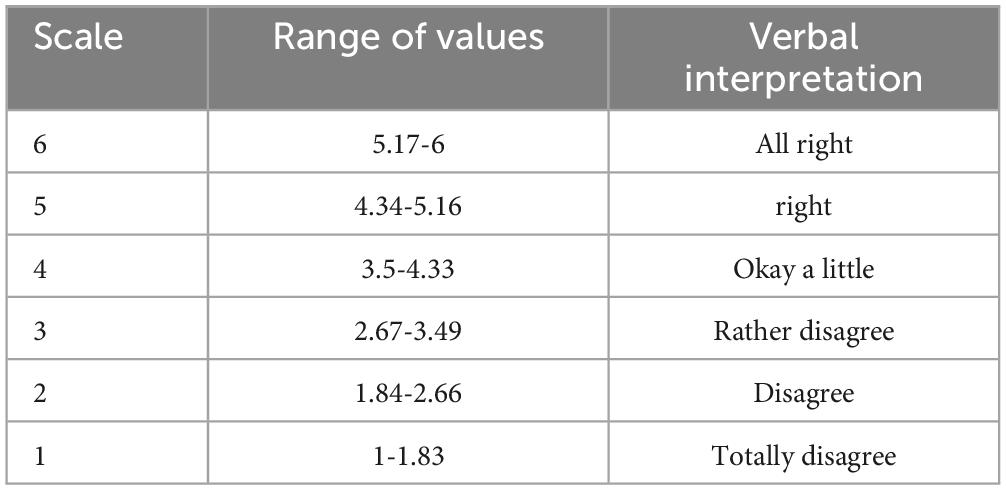

The data collected were processed by the statistical processing software, Statistical Package for Social Sciences, (SPSS) to calculate the mean value (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the different items and axes of the TEGEP scale. We used the evaluation form as the data collection tool and the weighted average as the statistical treatment. A 6-point Likert scale was used to determine the level of representation, as shown in Table 3.

Results

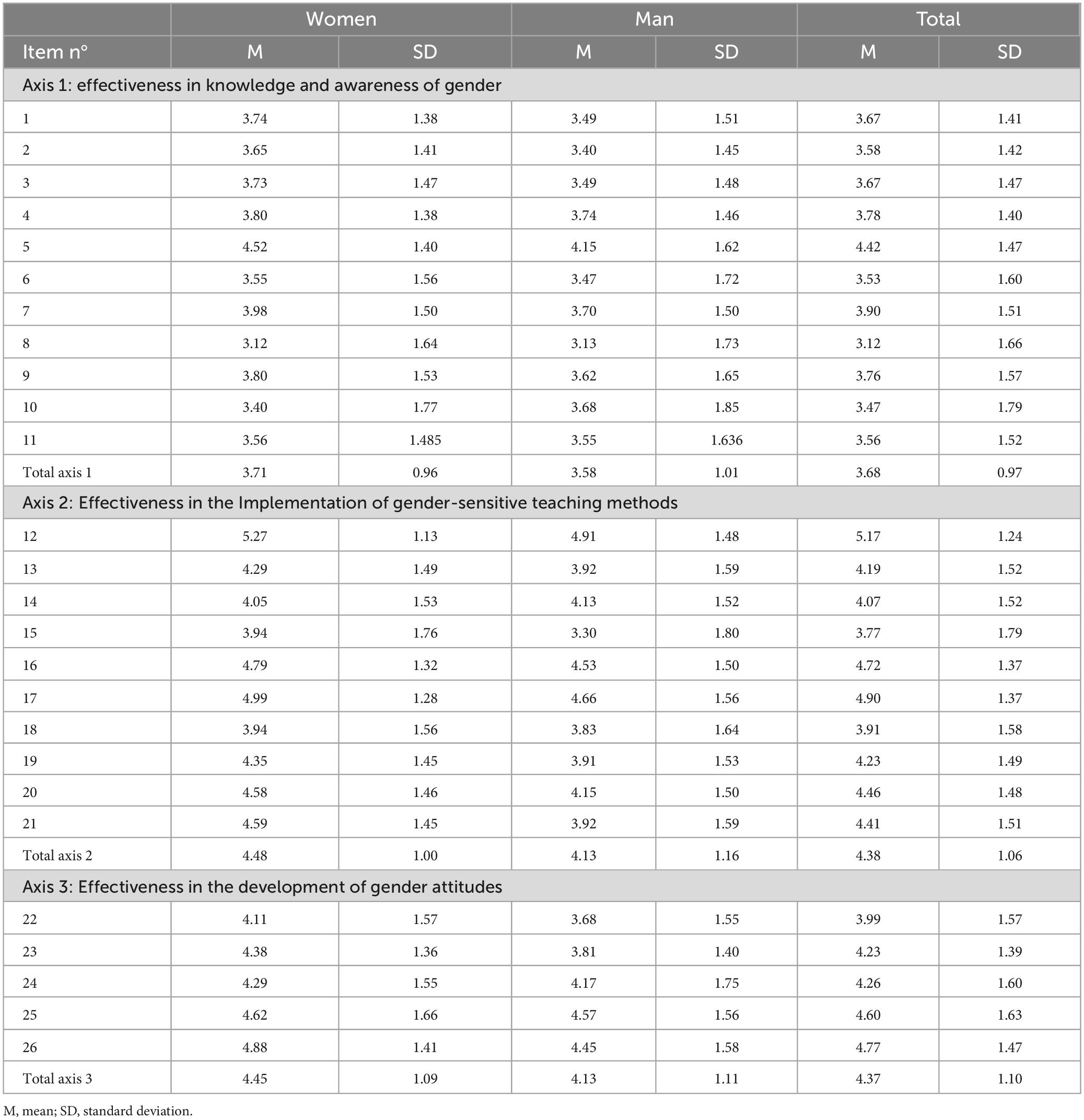

Table 4 presents the results of the means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for the 26 items and the corresponding axes of the Teacher Effectiveness of Gender Equality Practices (TEGEP) scale. The results are presented according to the three subscales (axes) for all participating trainees, by gender of participants and by disciplines taught.

Table 4. Perception by trainee teachers of the effectiveness of a teaching practice using the gender approach, by sex and for all participants.

According to all participants

In axis 1, concerning the effectiveness in knowledge and awareness of gender among trainee teachers, the average responses of trainee teachers is (M = 3.68). This indicates that respondents’ perceptions fall slightly above the midpoint of the scale (which is 3.5 on a scale of 1 to 6), signifying a general tendency to moderately agree “Agree a little” with the statements associated with this axis (Table 3). The standard deviation (SD = 0.97) suggests a moderate dispersion of responses around the mean, indicating some variability in respondents’ opinions. For effectiveness in the implementation of gender-sensitive teaching methods (axis 2) among the participants in this study, the average of the responses is (M = 4.34) with a standard deviation (SD = 1.06). According to Table 3, this value shows that respondents are, on average, rather “Agree” with the statements on this axis, being well above the midpoint of the scale. The standard deviation (SD = 1.06) indicates a slightly higher variability of responses compared to axis 1, suggesting that respondents’ opinions are a little more dispersed. For effectiveness in developing gender attitudes (axis 3) among respondents, the average response is (M = 4.37), similar to that of axis 2, indicating that respondents are, on average, rather “Agree” with the statements associated with this axis (Table 3). The standard deviation (SD = 1.10), slightly higher than that of axis 2, shows an even greater dispersion of responses, which means that the opinions of respondents on this axis vary more.

According to participants by gender

For axis 1, effectiveness in knowledge and awareness of gender, female and male participants have respectively averaged (M = 3.71) and (M = 3.58), which, according to Table 3 are “Okay a little.” On the other hand, we find that women have a slightly higher average compared to men, indicating that women agree a little more with the statements of this axis than men. The standard deviation is slightly lower for women (SD = 0.96) compared to men (SD = 1.01). This result suggests a slightly less dispersion of responses among women than among men. For axis 2, effectiveness in the implementation of gender-sensitive teaching methods, women have an average (M = 4.48); which is higher than that of men (M = 4.13). This shows that women are, on average, “Agree” with the statements of this axis than men “Agree a little” (Table 3). The standard deviation is (SD = 1.00) for women, which is lower than that of men (SD = 1.16), indicating greater uniformity in women’s responses compared to men. For axis 3 (effectiveness in the development of gender attitudes), the average response from women is (M = 4.45), compared to (M = 4.13) for men. This result means that women agree on average, more with the statements of this axis than men. The standard deviation is slightly lower for women (SD = 1.09) compared to men (SD = 1.11), indicating slightly less response variability among women.

According to the teaching specialty of the participants

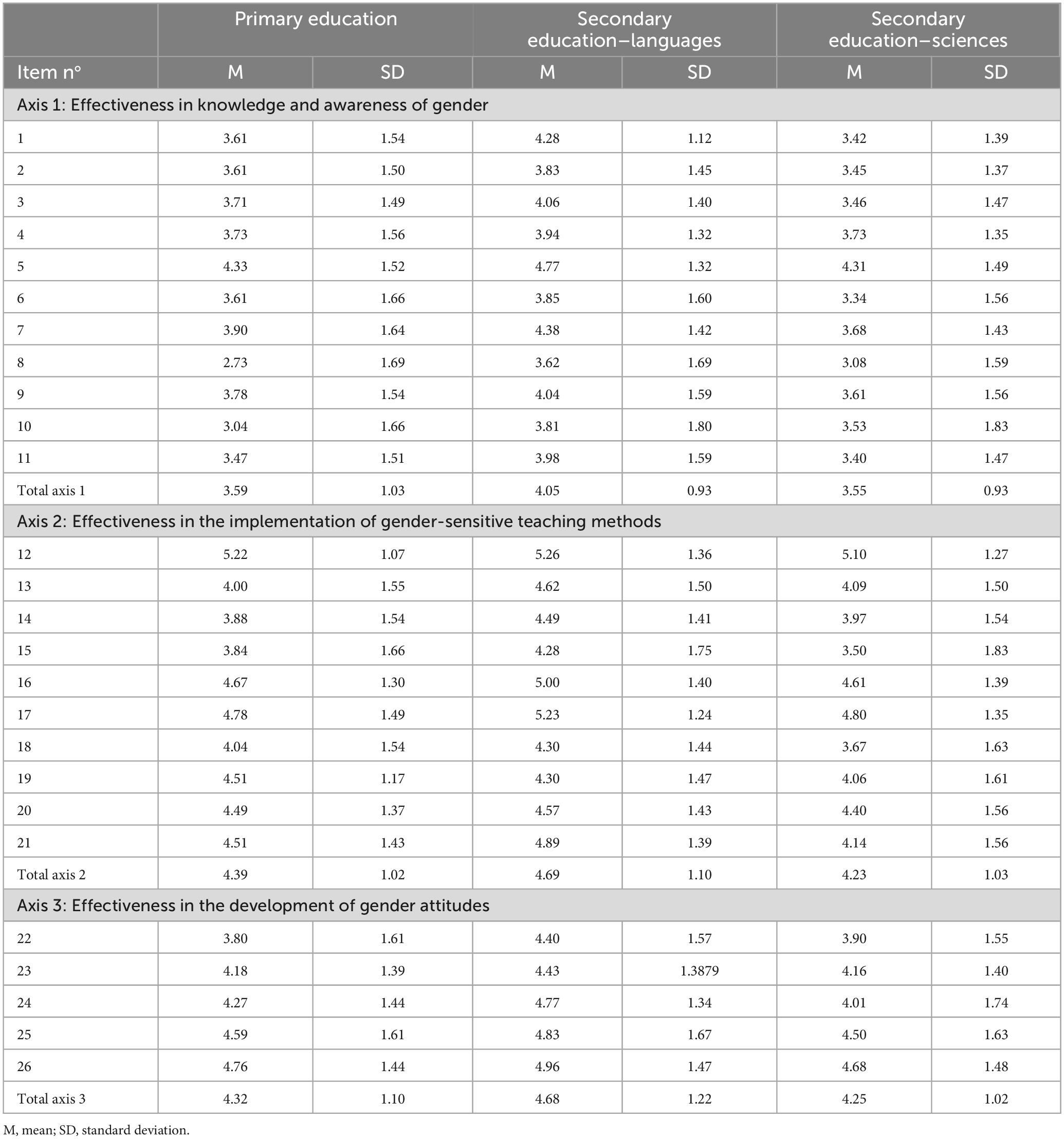

In this part, we present the results of the participants according to three groups (group 1 = Trainee teachers of primary education, group 2 = Trainee teachers of secondary education specialty: French languages and group 3 = Trainee teachers of secondary education specialty: Sciences; Table 5).

Table 5. Perception by trainee teachers of the effectiveness of a teaching practice using the gender approach, according to the teaching specialty of the participants.

For axis 1, concerning effectiveness in knowledge and awareness of gender, group 2 has the highest average (M = 4.05), therefore “Agree a little,” indicating that the participants of this group are, on average, more in agreement with the statements of this axis. Groups 1 and 3 have similar means, (M = 3.59) and (M = 3.55), respectively “Agree a little,” showing that they agree slightly less than group 2. The standard deviation is slightly higher for group 1 (SD = 1.03) compared to groups 2 and 3 (both SD = 0.93); which suggests a slightly greater variability of responses in group 1.

For axis 2, effectiveness in implementing gender-sensitive teaching methods, group 2 also has the highest average (M = 4.69; i.e., “Agree”), indicating a tendency to agree more with the statements of this axis compared to groups 1 and 3. Group 1 has an average of (M = 4.39), “Agree,” while group 3 has the lowest average (M = 4.23), “Agree a little” for this axis. The standard deviations are similar for groups 1 and 3 (SD = 1.02 and SD = 1.03, respectively), and slightly higher for group 2 (SD = 1.10), indicating a somewhat dispersion of responses greater in group 2.

Discussion

Observation of these results shows us that the gender approach acquires a particular place in the Moroccan educational system, which is gradually asserted through political, legislative and educational reforms,

Equality between men and women in education is one of the central elements of quality education, and is a question of social justice, granting the same rights in terms of access, content, school life, learning outcomes and opportunities in life and work [UNESCO, 2019 cited by Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco (2024), p. 17].

The collected data shows this progression in the assimilation of the gender approach in the educational environment. Indeed, most of the obtained data is between “agree a little” and “agree.” These results vary especially according to gender (man/woman) and according to the teaching specialty.

For axis 1 “Knowledge and awareness of gender among trainee teachers,” the results show that trainee teachers’ perceptions on this subject are moderately positive and fall in the “agree a little” interval. This is especially due to the evolution of the integration of the gender approach in Moroccan public policy and to the strong involvement of the Moroccan Ministry of National Education observable in the changes in curricula. Indeed, if we take the framework specifications for the primary cycle as an example, we’ll see that this document specifies that “the student’s textbook must be free of all forms of discrimination or anything that might suggest discrimination and consecrate it” and that it must “value the principles of equity, equality and contribute to the fight against all forms of violence (school violence, violence against women and children),” while seeking to “integrate the contributions of women into the content of school textbooks, in this case, thinkers, writers, novelists, poets, historians, researchers and artists” [Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco, 2024, p. 54]. Added to this is a perceptible general speech of its representatives,

Equality between men and women cannot therefore take place without this process of democratization, just as it cannot be achieved without collective awareness and a complete assimilation of the concepts and values which contribute to its construction, such as the concepts equality, equity, social justice or even parity (Echaabi, 2018).

However, it should be noted that the results of this research reveal a slight variation according to gender and a notable variation according to teaching discipline. Indeed, we see a uniformity of responses, with slightly higher scores among women compared to men. In addition, trainee teachers in the French language sector of the secondary cycle seem to have a slightly more positive and more homogeneous perception in relation to the gender approach. In contrast, trainee primary and science teachers show a greater diversity of opinions compared to their French language counterparts, suggesting more pronounced individual differences in the understanding and integration of gender-related concepts. Such results are in perfect homogeneity with the logic of the RCETP entry profiles for the two primary and qualifying cycles. Effectively, the profile of primary cycle trainees is very diverse because they come from several scientific, literary and human sciences university sectors. As a result, given the diversity of the range of their training which does not resemble one another, their knowledge and awareness of the gender approach is not expressed in the same way. In fact, this observation is underlined by several previous studies. As an example, we cite the study by Skelton et al. (2007) which emphasizes the influence of gender stereotypes on the representations of teachers and students. Conversely, trainees in the French language sector, given their openness to western culture, assimilate slightly better what relates to the gender approach given that the programs followed throughout their university curriculum closely touch on themes having a direct or indirect relationship with human rights, feminist literature, social justice, etc. This cultural background led them to build a certain conviction of the importance of including the gender approach in the field of education. Such beliefs, even if they manifest themselves in a modest way according to the present research, can lead, as Larkin (1994) points out, to the development of social justice toward girls at school. This wavering in the knowledge and awareness of gender among trainee teachers from various sectors and cycles participating in our exploratory survey shows that “the movement and dynamics of integration of the egalitarian paradigm, including the gender approach, through its application, is a constitutive moment” (Alami Mchichi et al., 2004, p. 279). Similarly, it informs us that training in the gender approach, which should be one of the pillars of the dissemination of gender awareness, is very limited at university and vocational training levels, and suffers from “a lack of standardization and great diversity in content and expectations” (Gillot and Nadifi, 2018, p. 79).

If we analyze the results of axis 2, effectiveness in the implementation of gender-sensitive teaching methods, we will see that they show that trainee teachers, on the whole, declare that they accept and apply gender-sensitive teaching methods. gender-responsive teaching in a positive way. Trainee teachers in the French language sector of the secondary education cycle are particularly effective in this area, with greater uniformity of responses among women. On the other hand, a greater diversity of opinions is observed among trainee primary and science teachers. First, the results of this axis are in harmony with those of axis 1. This congruence between the results of the two axes allows us to suppose by way of deduction, that the implementation of a method, such as that relating to gender, can only be realized through perfect knowledge and consciousness in relation to the latter. Moreover, several studies emphasize this fact; we cite, among others, that conducted by Alvesson and Billing (2009) which highlights the difficulty of applying the gender approach in the absence of training focused on practical strategies for its integration. Then, this obvious gap from one sector to another and between cycles, in addition to this difference in sensitivity toward the subject of gender noted between male and female trainee teachers reveals to us the need to pay attention particular to the standardization of perceptions and practices across all groups of trainees who access RCETP training; which standardization, as suggested by Younger and Warrington (2008) can be achieved through practical strategies, case studies, workshops, etc. This sensitivity which appears among a large number of trainees (see Tables 4, 5) to the implementation of educational methods taking gender into account, even if its level barely approaches the average according to the statistics of the present study, can be interpreted as being the result of a long process led by the Moroccan State which begins with the three levels of school education and finds its extension at the level of university education and in professional training through programs of continuing training aimed at raising teacher awareness gender equality (Report of the Kingdom of Morocco, Ministry of Family, Solidarity, Equality, and Social Development, 2018).

Axis 3, effectiveness in developing positive gender attitudes, reveals that teachers generally agree with the statements on the development of positive gender attitudes, although this acceptance is accompanied by greater diversity opinions in comparison with the other axes. Women feel slightly more effective than men in this area, with slightly greater consistency in their responses. Group 2, French-speaking teachers, stands out with a higher average but with a greater dispersion of opinions, reflecting a diversity of experiences and perceptions. Primary school teachers and science teachers show a similar but more homogeneous acceptance of their effectiveness in developing gender attitudes. These results, which are also in harmony with the above, show the efforts made to integrate the gender approach in the field of education. Indeed, at the primary level, there were, on many occasions, reforms carried out specifically to integrate this gender equality into school programs in order to eliminate any segregation affecting the image of women and how they are presented in materials. teaching-learning. Already The national charter for education and training, since 1999, has called for the revision and adaptation of programs, methods, school textbooks and teaching materials (Special Education Training Commission-Morocco, 1999, Lever 7, p. 45) and as Elammari (2018, p. 65–93) points out, this Charter sets two objectives of great importance for Moroccan society. The first consists of “eliminating by 2015, gender disparities at all levels of education” and the second asks “to contribute to the promotion of gender equality and equal opportunities within the education system in particular and at the national level in general.” All these interventions by the Ministry of National Education have led to an improvement in the perception of everything relating to the gender approach in the field of education in Morocco.

Conclusion and outlook

Our study sought to test the degree the sensitivity of trainee teachers to gender-related issues in education. Through their responses to a structured questionnaire, participants shared their perspectives on integrating the gender approach into teaching. The first axis of analysis focused on knowledge and awareness of gender, revealing that these aspects remain only moderately acquired by the majority of respondents. A similar trend was observed in the second and third axis, suggesting that while trainee teachers are aware of gender-related issues, their understanding is still developing, and their perspectives are not yet fully consolidated. Hence, verification of the initial hypothesis concerning awareness and knowledge of the gender approach shows us that the challenge is not entirely won and underlines the need for a more structured approach to gender education in teacher training programs.

To overcome these challenges, in-service training needs to be strengthened as a key mechanism for enhancing gender-related knowledge and fostering inclusive classroom teaching practices that challenge stereotypes and promote equal chances for all learners. At the same time, initial teacher training must place greater emphasis on gender-sensitive education. This can be achieved by embedding gender studies more explicitly in core training modules, particularly in those where the themes can be explored in depth, such as legislation and ethics, school life, and pedagogical research methodology. Incorporating practical case studies, interactive workshops, and reflective discussions on gender dynamics in the classroom would provide future teachers with the necessary tools to identify and address gender biases in their professional practice.

Beyond teacher training, there is an urgent need for a holistic approach combining training, institutional support and policy initiatives to ensure that gender sensitivity does not remain just an abstract concept but becomes a lived reality in classrooms and educational establishments.

In conclusion, while our study reveals an emerging awareness of gender issues among trainee teachers, it also underscores the need for sustained efforts to transform this awareness into concrete pedagogical practices. By reinforcing gender-sensitive training, fostering a culture of inclusivity, and integrating gender considerations into broader educational policies, we can move toward a more equitable and inclusive education system that benefits all learners, regardless of gender.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MB: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. BE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. SM: Data curation, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study has been made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alami Mchichi, H., Benradi, M., Chaker, A., Mouaqit, M., Saadi, M. S., and Yaakoubd, A. I. (2004). Féminin-Masculin. La marche vers l´égalité au Maroc: 1993–2003. Fes: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Alvesson, M., and Billing, Y. D. (2009). Understanding Gender and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781446280133

Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID),. (2004). Gender mainstreaming: Can it work for women’s rights? Spotlight 3, 1–11.

Benadada, A., and El Bouhsini, L. (2015). The Women’s Human Rights Movement in Morocco: Study Carried Out by the Center for the History of Present Times, January 2013–November 2014. Rabat: Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, Mohammed V University.

Echaabi, F. (2018). The Gender Issue in Education in MOROCCO, Education International. Available online at: https://www.ei-ie.org/fr/item/22385:8mars-la-question-du-genre-dans-lenseignement-au-maroc-par-fatima-echaabi (accessed July 17, 2024).

Elammari, B. (2018). Diagnosis of gendered education in Morocco: Evaluation and evolution. J. Multidisc. Stud. Econ. Soc. Sci. 3, 65–93. doi: 10.48375/IMIST.PRSM/remses-v3i2.12147

European Committee for Equality between Women and Men [ECEWM] (1996). Information forum on national policies in the field of equality between women and men proceedings, Budapest, 6–8 November 1995.

Gillot, G., and Nadifi, R. (2018). Gender and the University in Morocco. Current situation, Issues and Prospects. Paris: UNESCO.

High Commission for Planning (HCP)-Morocco. (2020). Moroccan Women in Figures: Evolution of Demographic and Socio-Professional Characteristics. Available online at: https://www.hcp.ma (accessed July 08, 2024).

Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco. (2015). Strategic Vision of the Reform 2015–2030. Available online at: https://www.csefrs.ma (accessed July 20, 2024).

Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (HCETSR)-Morocco. (2024). Gender Equality in and THROUGH Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Kingdom of Morocco (2018). Dahir n° 1-18-19 of 5 joumada II 1439 (22 February 2018) promulgating law n° 103-13 on combating violence against women, official Bulletin n° 6688. Available online at: http://www.sgg.gov.ma/BulletinOfficiel.aspx (accessed April 07, 2025).

Kingdom of Morocco, Ministry of Family, Solidarity, Equality, and Social Development. (2018). Report 2018: Challenges and Opportunities for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Rural Women and Girls, 62nd Session of the Commission on the Status of Women. New York: UN Women.

Kingdom of Morocco, State Secretariat for Families, Children and Persons with Disabilities. (2006). National Strategy for Equity and Gender Equality Through the Integration of the Gender Approach in Development Policies and Programs.

Kingdom of Morocco. (2011). Dahir No. 1-11-91 of 27 Chaabane 1432 Promulgating the Text of the Constitution. Official Bulletin, (5964 bis). Available online at: http://www.sgg.gov.ma/BulletinOfficiel.aspx (accessed April 1, 2025).

Larkin, J. (1994). Walking through Walls: The sexual harassment of high school girls. Gender Educ. 6, 263–280. doi: 10.1080/0954025940060303

Lundgren-Gothlin, E. (1996). Sex and Existence: Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, University Press of New England.

Miralles-Cardona, C., Chiner, E., and Cardona-Moltó, M.-C. (2021). Educating prospective teachers for a sustainable gender equality practice: Survey design and validation of a self-efficacy scale. Int. J. Sustainability High. Educ. 23, 379–403. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2020-0204

Monusco. (2024). What is Gender?. Available online at: https://monusco.unmissions.org/qu%E2%80%99est-ce-que-le-genre (accessed July 20, 2024).

Moser, C. (2005). An Introduction to Gender Audit Methodology: Its design and Implementation in DFID Malawi. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Québec Women and Development Committee (QWDC) of AQOCI. (2008). The institutionalization of gender: From Theoretical Conceptualization to Practice, Montréal, Canada. Available online at: https://www.csefrs.ma/publications/egalite-hommes-femmes-dans-et-a-travers-leducation/?lang=fr (accessed November 17, 2024).

Sabbar, M. (2021). Gender equality and education in Morocco: Current situation and perspectives. J. Educ. Adm. 10, 101–116. doi: 10.34874/PRSM.reade.28592

Skelton, C., Francis, B., and Valkanova, Y. (2007). Breaking Down the Stereotypes: Gender and Achievement in Schools. Hong Kong: Equal Opportunities Commission.

Special Education Training Commission-Morocco. (1999). National Education and Training Charter. Available online at: https://www.men.gov.ma/En/Pages/CNEF.aspx (accessed April 1, 2025).

UNESCO (2019). From access to empowerment: UNESCO’s strategy for gender equality in and through education 2019–2025 (accessed April 07, 2025).

World Bank, and Group. (2024). Women, Business and the Law 2024: Executive Summary. Washington, DC: The World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2063-2

Keywords: gender approach, perceptions, equality, equity, women’s empowerment, girls’ education, parity, effectiveness scale

Citation: Abid M, Bouali M, El Andaloussi B and Messaoud S (2025) The perceptions of Moroccan trainee teachers regarding the gender approach and its implementation in the classroom. Front. Educ. 10:1550413. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1550413

Received: 23 December 2024; Accepted: 26 March 2025;

Published: 14 April 2025.

Edited by:

Tanya Pinkerton, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kevin Davison, University of Galway, IrelandLindsie Spengler, Arizona State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Abid, Bouali, El Andaloussi and Messaoud. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Abid, cHJvZmFiaWRtZWRAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Mohammed Abid, orcid.org/0000-0002-7427-2215; Mostafa Bouali, orcid.org/0009-0003-8307-0708; Bouchra El Andaloussi, orcid.org/0009-0008-8839-8952; Said Messaoud, orcid.org/0009-0000-6390-6174

Mohammed Abid

Mohammed Abid Mostafa Bouali2†

Mostafa Bouali2†