- 1The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Humanities, Applied Linguistics Department, Lublin, Poland

- 2Department of Special Education, Institute of Pedagogy, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland

This article is dedicated to analyzing the learning styles, strategies, and ways of overcoming challenges in foreign language acquisition by D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students (DHH students). The ability of individuals with hearing impairments to acquire a foreign language effectively depends on various factors, such as the degree of hearing loss, the age at which language learning begins, and the availability of educational and environmental support. In research on this category of students, understanding specific learning styles and strategies that aid in the process of acquiring a new language is crucial. The article discusses diverse learning styles and strategies, as well as approaches to overcome difficulties preferred by D/deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals during foreign language learning. The quantitative study also examines educational strategies that support the development of language competencies in this group, including multimedia techniques, imagery, and visualizations that enhance and facilitate reading comprehension. The study aimed to identify dominant teaching styles and learning strategies for English among 55 DHH students from grades VII and VIII in selected primary schools. These schools follow the Core Curriculum for General Education, adapted for students with hearing impairments. A quantitative questionnaire was used, comprising three thematic sections on reading comprehension and learning difficulties. Participants answered closed questions using a three-point scale: I never do, sometimes do, always do. The key research questions explored: (1) The reading strategies DHH students use for comprehension; (2) Differences in strategy application based on gender, hearing loss degree, communication method, and onset time of hearing loss, (3) General difficulties DHH students face in learning foreign languages. The findings of a questionnaire were subjected to statistical analysis and indicate that appropriate adaptation of teaching methods and consideration of the individual preferences of deaf students can significantly improve their success in foreign language learning and their motivation to study.

1 Introduction

Learning a foreign language is a complex process that requires engaging various cognitive and sensory resources. For D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students, who experience varying degrees of hearing loss, this process becomes even more challenging, as the lack of full auditory perception hinders the acquisition of fundamental language elements such as pronunciation, intonation, and speech rhythm. Therefore, foreign language learning for D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students requires applying specific learning styles and teaching strategies that account for the limitations caused by hearing loss while leveraging their strengths, such as visual memory and analytical skills (Dłużniewska, 2016; Kamiński, 2021; Karpińska-Szaj, 2024).

In the last decade, we have witnessed an extremely intensive transformation for people with hearing impairments. These include specialist diagnostics, rehabilitation, and education, but also technical and technological support. All these developments are increasing the auditory and linguistic functioning of this group of people. The conditions for social inclusion are also improving, meaning that it is possible to ensure full participation in social life, work, education, and culture. To be more specific, the USA’s comprehensive support for Deaf and hard-of-hearing students is offered through individualized education programs (IEPs) and services mandated by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). These provisions ensure access to necessary accommodations and services, promoting inclusive education. Additionally, Canada upholds the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, advocating for education in sign language. The Canadian Association of the Deaf emphasizes the importance of primary communication methods before introducing additional languages, supporting tailored educational approaches for Deaf students.

As Krakowiak (2017) believes, being open to communicating with people with disabilities requires the able-bodied to know about the possibilities of communicating with them and to have a good understanding of how important it is for every person to communicate with others. Lack of communication may result in a blockage of the child’s psychological development and becomes a secondary cause of a worsening of the disability, regardless of the root causes that led to the communication difficulties and the symptoms of these difficulties. This is why it is so important for non-disabled people not only to open up to the needs of people with disabilities but also to take concrete action to break down communication barriers. This does not only support the development of people with disabilities but also builds a more inclusive and empathetic society.

The literature (Dłużniewska, 2016; Domagała-Zyśk, 2016; Krakowiak, 2017; Karpińska-Szaj, 2024) on language learning by DHH individuals highlights that these students can achieve significant success in acquiring foreign languages, provided they receive appropriate support and teaching methods tailored to their individual needs. There are numerous strategies and learning styles that can facilitate this process. This article discusses the diverse learning styles preferred by D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the context of foreign language acquisition. It also examines teaching strategies that support the development of language competencies in this group of students.

2 Learning styles and strategies in foreign language acquisition – theoretical foundations

2.1 Language learning strategies

Research on language learning by deaf and hard-of-hearing people, both in Poland and internationally, focuses mainly on analyzing the difficulties and evaluating the effectiveness of teaching methods aimed at developing communicative competence, primarily in written, but also in spoken communication (cf. Kamiński, 2021). Contemporary research shows that with appropriate preparation and support, it is possible to achieve satisfactory results in language teaching for deaf and hard-of-hearing learners in all language skills, including speaking skills (Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2012; Karpińska-Szaj, 2024). Domagała-Zyśk (2013) states that learning styles in the context of Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) students refer to the diverse ways in which individuals absorb, process, and retain information. These learning styles can be influenced by factors such as language modality (spoken language, sign language, lip-reading), the level of hearing loss, and the use of assistive technologies like hearing aids or cochlear implants. However, it is true that defining these styles in a more explicit manner could enhance the clarity and consistency of the findings, making them more accessible for educators looking to apply these strategies.

Oxford (1992/1993, p. 18) defines learning strategies as ‘specific actions, behaviors, steps or techniques that learners use to improve their skills in the language they are learning. These strategies may facilitate the internalization of language, the retention of acquired knowledge, the recall of messages, or the use of newly learned knowledge. Learning strategies are tools through which the learner is internally committed to developing their own language skills’.

The researcher classifies language learning strategies into direct ones, which are involved in conscious mental processes, and indirect ones, which are not used consciously but are important in the foreign language acquisition process among the direct categories.

Oxford (1990, p.37, p.137) highlights memory strategies that facilitate effective memorization of learned material, for example, by grouping similar objects or visualizations. She also lists cognitive strategies, such as summarizing and deductive reasoning, that enable understanding and use of language and help sustain interaction with others. She refers to compensatory strategies, like guessing or substituting synonyms, which help learners maintain communication when they encounter gaps in their knowledge.

A slightly different typology of strategies is distinguished by Marton and Saljo (after Aharony, 2006), dividing them into deep (mature) and surface (immature) strategies.

1. Students who use deep strategies are characterized by their ability to relate to newly learned information to previously held information, their need to learn about a given reality from different points of view, and their desire to connect the knowledge they learn to their applications in everyday life and personal experiences.

Biggs (1993) believes that students who use metacognitive strategies are innovative in their search for solutions and plan their next learning steps, are personally involved in the learning process, and are characterized by high levels of motivation.

2. Students using superficial strategies try to take the shortest route to reach their goal, do not ask questions that would help them to deepen their knowledge, and learn by heart even though they do not understand it. They focus primarily on avoiding failure, but the strategies they use are also effective learning tools (Domagała-Zyśk, 2016).

The conscious use of learning strategies increases the effectiveness of the process. Thanks to them, a person assimilates more information, has structured knowledge, has a better understanding of themselves and the surrounding reality, and has the opportunity to learn more about the world. Strategies bring the satisfaction of success. Although they do not eliminate the need for effort, they develop a sense of agency and give meaning to the actions undertaken (Czerniawska, 1994; Szymczak, 2012).

Learning style, on the other hand, is the adopted way of behaving in learning situations. It can also be seen as a preference ‘to use specific strategies, regardless of the demands of particular tasks’ (Czerniawska and Jagodzińska, 2007, p. 228). Knowledge of one’s learning style makes it possible to create conditions conducive to the achievement of intended goals. Therefore, it can be concluded that such knowledge is crucial for both the learner and the person who supports them. Learning styles are flexible and continuously adapt over time rather than being fixed or pre-established. This means that both the learner and their carers can actively shape learning situations that support the development of such a style, allowing for conscious, purposeful and structured participation in the learning process.

As Piłatowska (2008) writes, an important task for the teacher is not so much to discover the student’s learning style, whether through direct observation or by means of special tests, but to introduce a variety of activities that engage as many learning styles as possible.

2.2 Strategies for dealing with language difficulties

Kolodziejczyk (2021) identifies the coping mechanisms used by individuals with hearing impairments to overcome challenges in general language skills. She classifies these strategies based on their underlying triggers, grouping them into three categories: logico-linguistic, psychosocial, and rehabilitative-educational. Logical-linguistic strategies are those that are related to the students’ linguistic skills and are motivated by the same linguistic activities that also accompany the speech development of hearing children, hence they can be observed in all children who are at a similar stage of speech development, although in the case of hearing children at a much younger age and at an earlier stage of cognitive and social development. Logical-linguistic strategies may include:

– echolalia (repetitions) with a phatic and educational function; code-switching with natural gestures, mimicry, and pantomime as well as pointing to people, things, phenomena, and the use of graphics; substituting a form with an easier one; redundancy; linguistic analogy; logical analogies.

Psychosocial strategies result from the child’s individual personality traits and from certain social attitudes developed in the child’s educational environment. These can include:

– silence; all forms of avoidance, with the exception of silence; echolalia as avoidance; all types of emotional contact establishment and maintenance.

Rehabilitative-educational strategies are related to the way the student is educated, and to the choice and use of different methods of communication. Such strategies may include:

– mechanical echolalia; code-switching to sign language, dactylography, speech with phonogests; some types of code duplication; copies and borrowings from sign language.

Strategies can be divided into universal and individual strategies, taking into account the universality of their use. Most logico-linguistic strategies are universal, while psychosocial and rehabilitative-educational strategies are closely related to the individual characteristics of the child’s personality, specific educational environment and educational process, which gives them an individual character.

Considering the way in which language acquisition takes place and the conditions under which this process occurs in the case of children with hearing impairments, it is also worth dividing the strategies into developmental ones, observed in all children, typical of the natural process of language acquisition, and glottodidactic ones (Kołodziejczyk, 2021), resulting from insufficient language skills and experience, often observed at different stages of foreign language learning, i.e., typical of foreign language teaching in the didactic process. As Kołodziejczyk (2021) states, glottodidactic strategies include:

– all types of avoidance; mechanical echolalia and echolalia as avoidance; code-switching to other conventional systems, but also intensive use of natural gestures and facial expressions; some forms of substitution with easier forms: use of root forms of words, keywords, hyperonyms, close and related words, use of paraphrase and other parts of speech; all strategies from the redundancy category, taking into account the severity of these phenomena; borrowing and copies from a foreign language.

This division makes it possible to highlight the fact that the process of language mastery of the profoundly deaf child is an intermediate phenomenon between natural language acquisition and artificial language learning, since it presents features of, and uses strategies typical of, both the one and the other phenomenon. Such behaviour testifies to the fact that deaf children in the process of rehabilitation and education with some language education methods can acquire lexical units themselves, but have very limited access to grammatical information, contained in our language in the inflectional endings of words. This happens when the rehabilitation method is inappropriately matched to the child’s perceptual abilities.

2.3 Strategies for teaching and learning reading comprehension

Based on the findings of scholars (Krakowiak, 2012; Domagała-Zyśk, 2013; Dłużniewska, 2021), hearing impairment is not directly related to cognitive impairment. Deaf and hard-of-hearing people are characterized by varying levels of intelligence and knowledge, just like hearing people. This can be both high and below average, especially when other disorders co-occur. However, hearing impairment means having to overcome barriers to learn about the world, which deaf and hard-of-hearing people do with varying degrees of success. This is important in the process of learning and acquiring a foreign language, as difficulties in understanding texts can result both from a lack of general knowledge and from insufficient knowledge of the vocabulary and grammar of the foreign language. Krakowiak (2012), Domagała-Zyśk (2013), and Dłużniewska (2021) state that it is necessary to apply specific strategies for learning and teaching reading comprehension. In this process, it is worthwhile to use commonly used methods when working with deaf and hard-of-hearing students, but they should be supplemented with strategies that are typical of glottodidactics. The ability to read is directly related to how deaf people cope with language difficulties. The following strategies can be distinguished: keywords, prior activation of general knowledge, the ‘reading bath’ strategy, and the strategy of reading texts about the life of deaf and hard-of-hearing people.1 According to Domagała-Zyśk (2013, p. 257-262), the keyword strategy is to focus the learning and teaching process on preparing deaf people to receive the text, through exercises that test their comprehension of the language being taught. The development of keywords in the text allows for a full understanding of the content of the text.

Prior activation of general knowledge consists in the fact that it is necessary to activate or supplement the learner’s general knowledge before working with the text. This can be, for example, a short conversation in the national language or the preparation of materials on the topic (in the national language). In this strategy, it is important to encourage activity and responsibility for one’s own education. It is worth suggesting ways to seek information.

The “reading bath” strategy involves frequent and intensive reading of various texts, not only those in foreign language textbooks. This strategy serves to consolidate vocabulary that can appear in different contexts. The texts do not have to be analyzed, it is just a matter of contact with the written word. There may be some difficulty in convincing deaf people to read spontaneously, unforced.

Reading texts about the lives of deaf and hard of hearing people is a strategy that can result in increased motivation to read, but also positively affect self-esteem through identification with similar people, especially those who have been successful in life. These can be blogs or newspaper articles, texts on athletes participating in the Olympics for the hearing impaired are numerous.

As Dłużniewska (2016) claims previous research on the reading process in deaf and hard-of-hearing people indicates that the most serious obstacle to reading comprehension is the syntactic level. Mastery of the syntactic principles of the language is therefore crucial. In this context, it is worth returning to the basics, namely the phonological and morphological levels. In the case of inflectional languages such as Polish, the recognition of words and the determination of their syntactic function is based on the analysis of the main lexical morpheme and the word-forming and inflectional morphemes. Grasping the grammatical-logical structure of a sentence requires recognizing that its meaning can shift based on word order or alterations in word meanings, such as through prefixes and suffixes (459).

Researchers (Krakowiak, 1995, 2012; Dłużniewska, 2016, 2021; Miller, 2004, 2005) in the field of reading in deaf people unanimously emphasize that mastery of reading comprehension poses a particularly difficult challenge for this group. Although there is ongoing focus on the importance of developing this skill in the education system, efforts to create effective strategies so far have not yielded satisfactory results. The issue may lie in the excessive focus on the debate over selecting the primary communication system for the linguistic and cultural minority of deaf individuals, which distracts from the main concern—restricted access to spoken language. It is this lack that is a significant barrier to fully realizing the intellectual potential of many deaf people.

Linguistic competence plays a key role in reading, as it is what makes it possible to understand and interpret a text. Linguistic competence includes knowledge of vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, as well as the ability to recognize and interpret the meanings of words in different contexts. Without an adequate level of this competence, readers may encounter difficulties in reading the author’s intentions, understanding deeper content, or making inferences based on the information they have read. Linguistic competence also influences the ability to analyze a text, detect its structure, and distinguish important from less important information. Individuals with developed linguistic competence are able to process information fluently, which allows them not only to understand the text but also to critically evaluate it and apply the knowledge they have acquired. Moreover, linguistic competence is crucial for the development of reading comprehension skills at different levels, from simple narrative texts to complex, specialized material. Therefore, its development, especially in early childhood education, is the foundation for effective reading and subsequent learning.

3 Comparative case studies from different educational systems: the experiences of DHH students across various cultural contexts

To capture the diversity of D/deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) learners’ experiences across various cultural contexts, a broader range of comparative case studies could include the following:

A comparison between Deaf education in the United States and Finland highlights distinct educational frameworks. In the U.S., DHH students benefit from diverse approaches, such as mainstream schooling with sign language interpreters and specialized schools using American Sign Language (ASL). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) ensures DHH students receive tailored support and accommodations (Traxler, 2000). In contrast, Finland emphasizes inclusivity, offering bilingual education in Finnish Sign Language and written Finnish, and prioritizing the integration of DHH students into mainstream classrooms alongside individualized support (Mäki and Vuorinen, 2021).

The educational experiences of DHH students in Japan and Sweden also differ significantly. In Japan, students often attend specialized schools that focus on oral communication and lip-reading, though there is a growing acceptance of sign language (Muto and Hara, 2018). Sweden, on the other hand, provides a bilingual educational model, with Swedish Sign Language and Swedish as the mediums of instruction, and DHH students are integrated into regular schools with necessary accommodations, such as sign language interpreters and assistive technology (Rönnberg and Josefsson, 2019).

In the United Kingdom and New Zealand, both countries have diverse provisions for DHH learners. In the UK, DHH students can attend residential schools or mainstream schools with support services, with a focus on British Sign Language (BSL) and inclusion in mainstream classrooms (Gaskell and Seymour, 2018). New Zealand follows a bilingual-bicultural approach, offering education in both New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) and English, ensuring inclusion through either specialized schools or integrated mainstream classrooms (Knoors and Marschark, 2014).

Australia and Germany demonstrate contrasting approaches to educating DHH students. Australia has a mixed system that includes specialized institutions and mainstream schools offering access to Auslan (Australian Sign Language). The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) provides tailored support services (Monk and Sims, 2020). Germany, traditionally home to specialized schools using German Sign Language (DGS), is increasingly adopting more inclusive practices, integrating DHH students into mainstream classrooms with adaptations like sign language interpreters and speech-to-text services (Müller and Lütke, 2015).

In South Africa and Brazil, the educational provision for DHH students varies considerably. In South Africa, many DHH students attend specialized schools, with limited access to resources in rural areas. South African Sign Language (SASL) is integrated into the curriculum, although challenges remain (Polack, 2015). Brazil, focusing on bilingual education, emphasizes both Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and written Portuguese, but continues to face challenges in resource allocation and teacher training (Sanches and Lima, 2017).

Lastly, Canada and Norway offer differing models for DHH education. In Canada, DHH students have a range of educational options, including specialized schools and mainstream institutions with sign language interpreters, though the emphasis on bilingual education varies by province (Knoors and Marschark, 2014). Norway integrates DHH students into mainstream schools with support services, recognizing Norwegian Sign Language (NSL) as an official language, and offering education in both NSL and Norwegian, depending on individual needs (Tveit and Schreiber, 2018).

These comparative case studies illustrate how different cultural, educational, and legal frameworks impact the experiences of DHH learners. They underscore the successes and challenges of various educational approaches and show how different systems adapt their teaching methods, resources, and curricula to better meet the needs of DHH students.

4 Methodology—research aim, participants, and teaching context

The primary aim of the study was to determine which teaching styles and strategies for learning English to DHH students are dominant. The teaching styles and strategies were examined in relation to reading comprehension (1) and learning difficulties (2). The quantitative research tool was a questionnaire consisting of three thematic blocks covering the above-mentioned language skills. In each block, the participants were asked to answer closed questions, selecting one of the following options: *I never do **I sometimes do ***I always do.

The main research questions were:

1. What types of reading strategies do DDH students apply in developing reading comprehension?

2. What are the differences in reading strategies applications regarding the four variables, that is gender, degree of hearing loss, method of communication with the environment, and time of onset of hearing loss?

3. What kind of general difficulties do DHH students encounter in the process of acquiring foreign languages?

Fifteen primary schools that serve D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students were randomly chosen and invited to participate in the study. Responses with agreement to participate were received from ten schools located in Lublin, Greater Poland, and Masovian Voivodeships, and a snowball sampling method was employed to gather the expected results. The participants were 55 students from grades VII and VIII of a primary school, including 32 girls and 23 boys, who as part of the school’s offerings follow a curriculum in line with the Core Curriculum for General.

Regarding the gender categorization, respondents were provided with the option to select “other” allowing for flexibility in gender identification. However, since no participants selected this option, it was not included in the analysis. It is important to explicitly mention this aspect in the study to enhance clarity and inclusivity. Education in primary schools adapted to the needs and abilities of students with hearing impairments. English language lessons are conducted using methods tailored to the needs and capabilities of DHH children, with students systematically working on speech development, vocabulary enrichment, and articulation improvement. Classes are conducted with adjustments to the communication methods according to the student’s needs.

There are various educational challenges for DHH students in Poland. Firstly, the number of specialized schools is limited. In Poland, there are relatively few schools specifically designed for DHH students. These specialized schools are often located in larger cities, making access difficult for children from rural areas or small towns. While efforts have been made to integrate DHH students into mainstream schools, many schools lack adequate resources, such as trained teachers, interpreters, and assistive technology. As a result, many DHH students face significant barriers in mainstream education. Secondly, there are some communication barriers mostly represented by an insufficient use of sign language. Although Polish Sign Language is recognized, its use in education is not widespread. Many teachers are not proficient in using it, and teaching materials designed specifically for sign language users are scarce. Additionally, there is a problem with teacher training and support. Teachers in mainstream schools often do not have the specialized training needed to support DHH students. This includes training in Polish Sign language, understanding the cognitive and social needs of DHH students, and strategies for inclusive education. Moreover, there is a shortage of support staff. Schools often lack crucial support staff, such as interpreters, speech therapists, and special education counselors. Finally, there are issues regarding policy and legal framework. While Poland has laws ensuring the right to education for DHH students, implementation and enforcement of these laws vary. Many schools do not fully comply with accessibility standards, and funding for necessary accommodations is often insufficient. There are ongoing efforts to promote inclusive education, but significant disparities remain in the quality of education provided to DHH students in different regions (Oxford, 1990; Krakowiak, 1995; Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2012; Dłużniewska, 2021; Kołodziejczyk, 2021; Kamiński, 2021).

5 Results

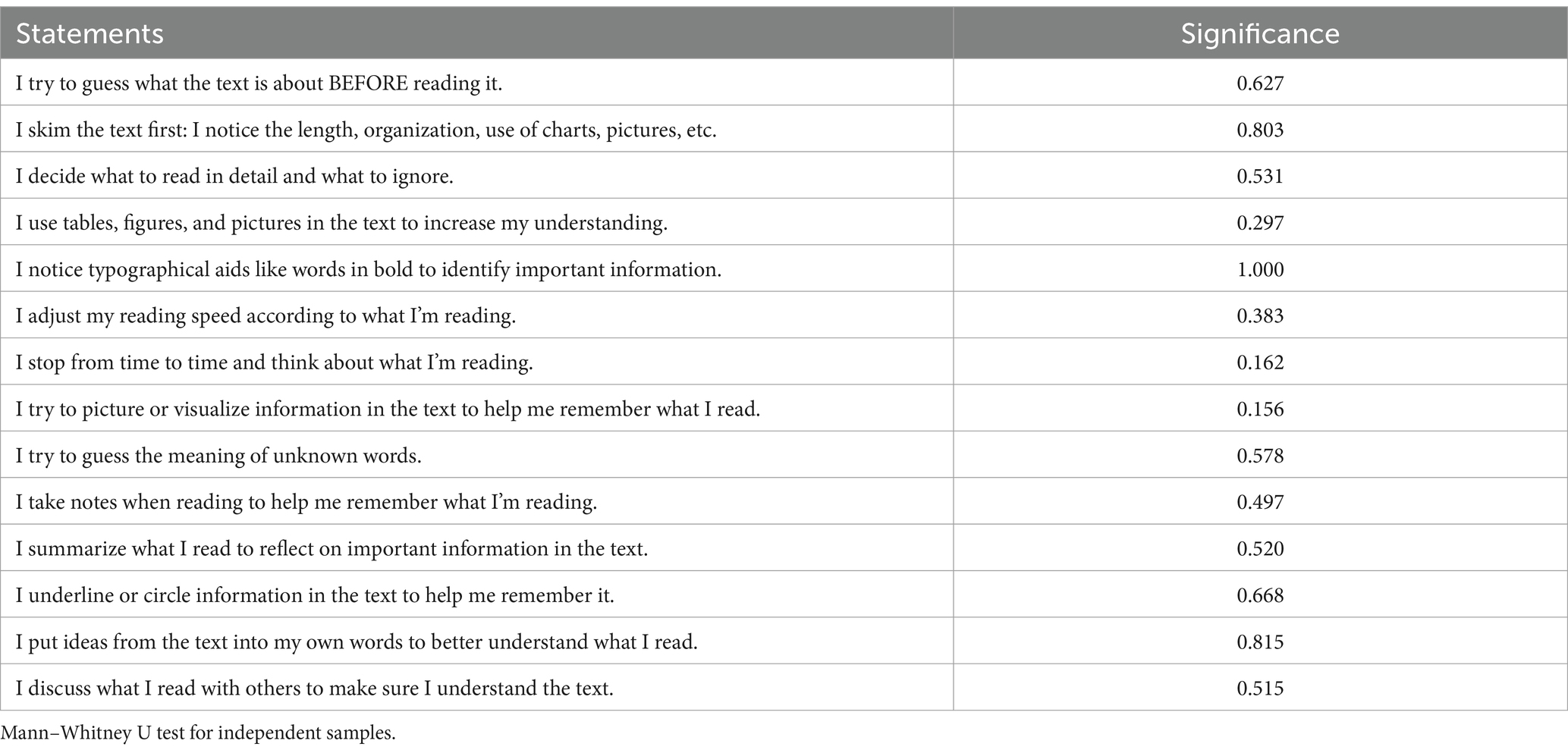

The study analysis assessed the significance of differences through statistical methods. The grouping variables were: gender, degree of hearing loss, method of communication with the environment, and hearing loss onset. The relevant tests for this analysis include the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples (used when the grouping variable divides participants into two groups) and the Kruskal-Wallis test for independent samples (used when the grouping variable divides participants into more than two groups). The significance threshold is set at p = 0.05. All data that was statistically significant is highlighted with an asterisk in the tables.

5.1 Reading strategies and gender

Based on the results from the Mann–Whitney U test presented in Table 1, the following analysis of the reading strategies across gender groups (male and female) can be made:

1. Pre-reading strategies:

These strategies focus on preparing for reading before engaging with the text. They include attempts to predict, skim, or analyze the structure of the text:

“I try to guess what the text is about BEFORE reading it” (p = 0.627); “I skim the text first: I notice the length, organization, use of charts, pictures, etc.” (p = 0.803); “I decide what to read in detail and what to ignore” (p = 0.531).

2. During-reading strategies:

These strategies are used while reading, such as engaging with the text through visual aids, adjusting reading speed, or taking time to reflect:

“I use tables, figures and pictures in text to increase my understanding” (p = 0.297); “I notice typographical aids like words in bold to identify important information” (p = 1.000); “I adjust my reading speed according to what I’m reading” (p = 0.383); “I stop from time to time and think about what I’m reading” (p = 0.162).

3. Post-reading strategies:

These strategies are used after reading the text, including activities like summarizing, visualizing, and discussing the content:

“I try to picture or visualize information in the text to help me remember what I read” (p = 0.156); “I try to guess the meaning of unknown words” (p = 0.578); “I take notes when reading to help me remember what I’m reading” (p = 0.497); “I summarize what I read to reflect on important information in the text” (p = 0.520); “I underline or circle information in the text to help me remember it” (p = 0.668); “I put ideas from the text into my own words to better understand what I read” (p = 0.815); “I discuss what I read with others to make sure I understand the text” (p = 0.515).

For all the reading strategies examined, the Mann–Whitney U test results show no significant differences between genders. Therefore, the null hypothesis is accepted for each statement, meaning that both male and female participants seem to employ these reading strategies in similar ways, regardless of gender.

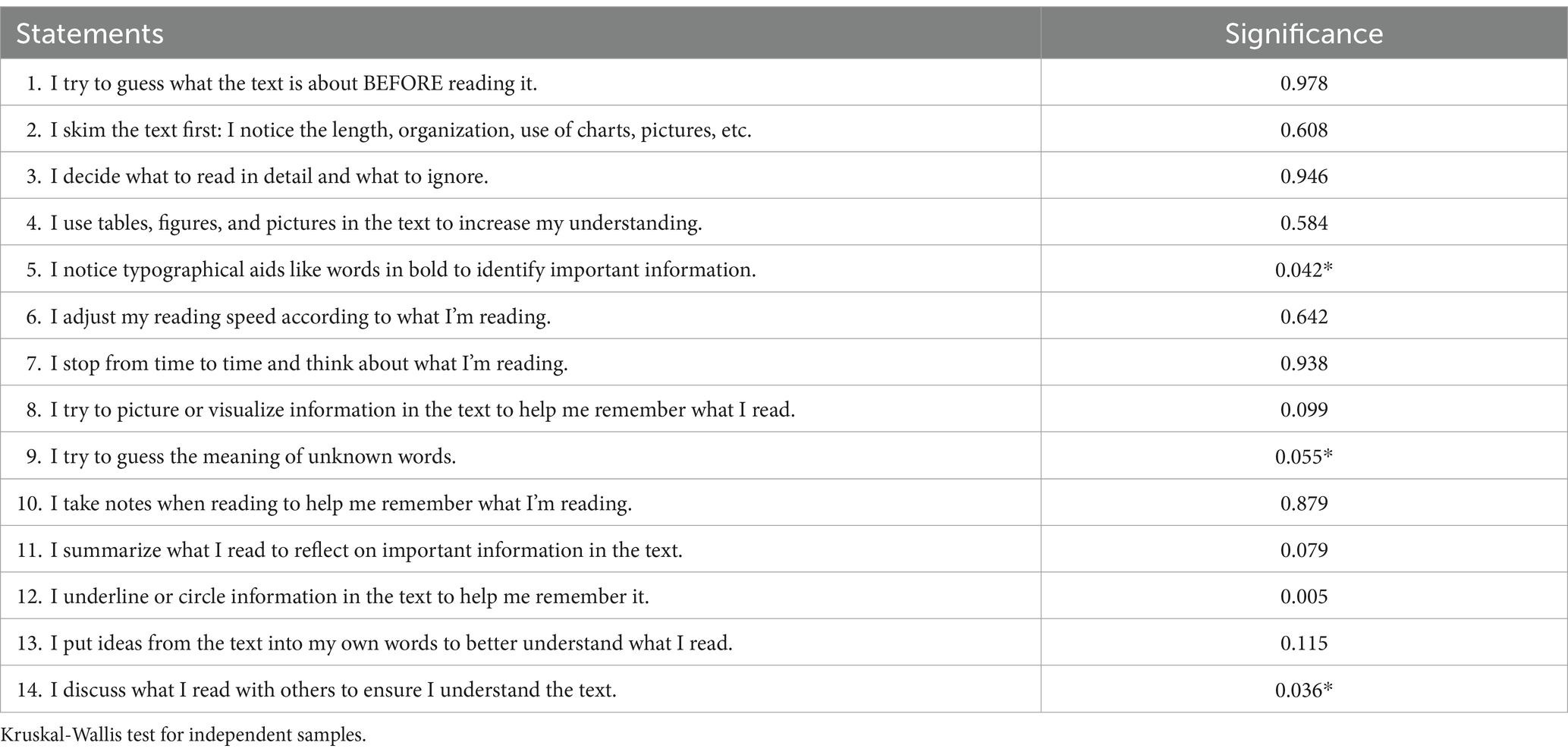

I. Degree of hearing loss and reading strategies

For the majority of the statements in the above table, the null hypothesis was accepted, indicating no significant difference in how participants with varying degrees of hearing loss approach these specific pre-, during, and post-reading strategies. However, there are also statements with significant statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05), indicating that participants with different degrees of hearing loss employed significantly different reading strategies in these cases:

• “I notice typographical aids like words in bold to identify important information” (p = 0.042) This suggests that the degree of hearing loss may influence how participants pay attention to typographical cues such as bold or italicized text to identify key information.

• “I try to guess the meaning of unknown words” (p = 0.055 – marginal significance, close to threshold). Although this result is just above the significance level, it still indicates a trend toward a difference in how participants infer the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary.

• “I discuss what I read with others to ensure I understand the text” (p = 0.036)

This implies that the degree of hearing loss may affect how frequently DHH participants engage in discussions about what they have read, potentially reflecting differences in communication preferences or opportunities (Table 2).

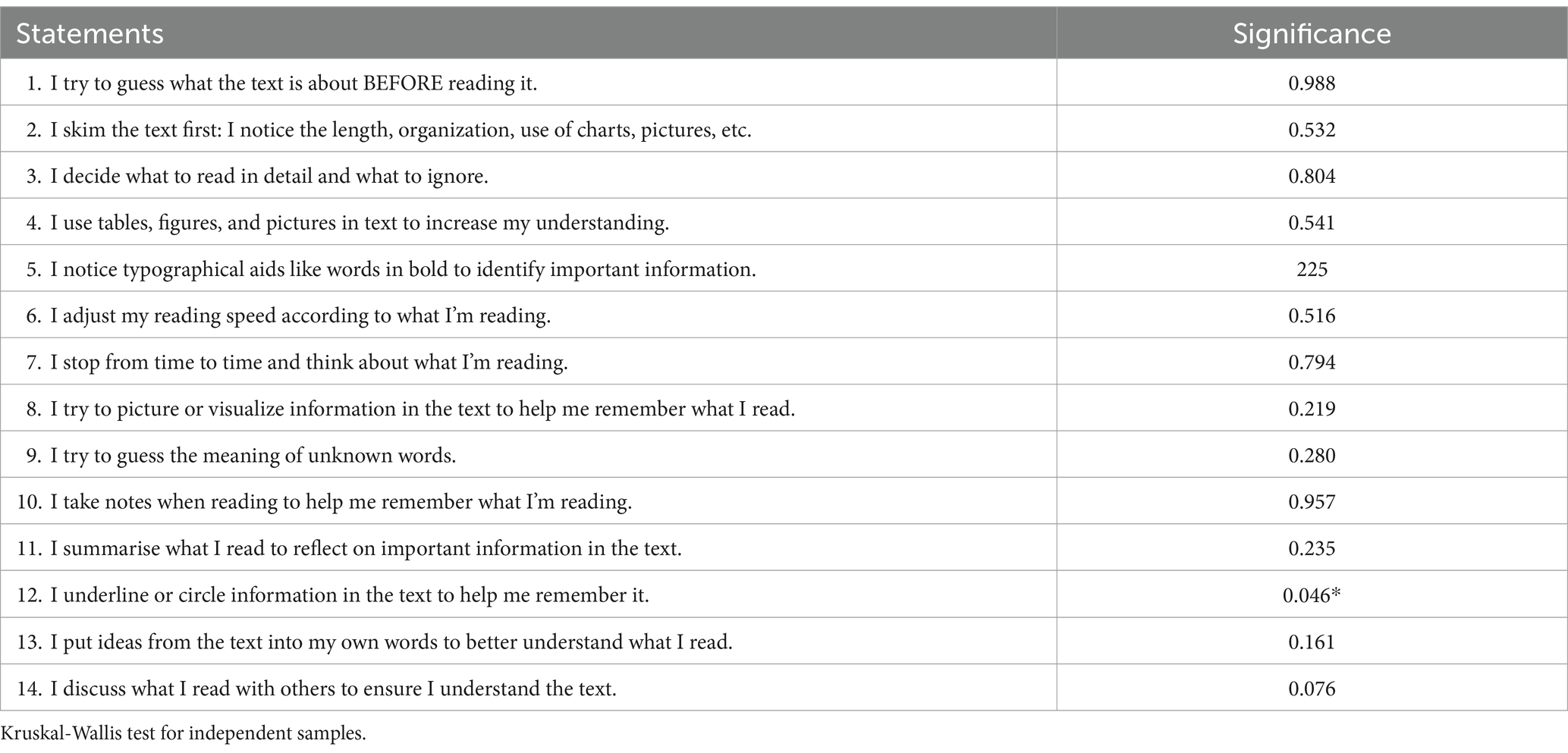

II. Method of communication and reading strategies

The table below presents the results of a Kruskal-Wallis test for independent samples, where the grouping variable is the method of communication with the environment (e.g., spoken language, sign language, or a combination of both). The test aims to determine whether the method of communication significantly affects the use of various reading strategies by D/deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students. For most reading strategies, the null hypothesis was accepted, meaning there were no significant differences in how students using different communication methods approach these strategies. However, there is one statement with a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05), Table 3.

Regarding the application of the pre-reading strategies:

“I try to guess what the text is about BEFORE reading it” (p = 0.988);

“I skim the text first: I notice the length, organization, use of charts, pictures, etc.” (p = 0.532); “I decide what to read in detail and what to ignore” (p = 0.804). The p-value in all strategies suggests that the method of communication does not significantly affect the decision-making process regarding which parts of the text to read in detail or ignore.

In terms of during-reading strategies:

“I use tables, figures, and pictures in the text to increase my understanding” (p = 0.541); “I notice typographical aids like words in bold to identify important information” (p = 0.225); “I adjust my reading speed according to what I’m reading” (p = 0.516); “I stop from time to time and think about what I’m reading” (p = 0.794); “I try to picture or visualize information in the text to help me remember what I read” (p = 0.219); “I try to guess the meaning of unknown words” (p = 0.280). The p-value suggests that students across communication methods use similar strategies for guessing the meaning of unfamiliar words, indicating no significant difference in this approach.

Concerning the post-reading strategies:

“I take notes when reading to help me remember what I’m reading” (p = 0.957); “I summarise what I read to reflect on important information in the text” (p = 0.235); “I put ideas from the text into my own words to better understand what I read” (p = 0.161); “I discuss what I read with others to ensure I understand the text” (p = 0.076); “I underline or circle information in the text to help me remember it” (p = 0.046). This strategy reveals a significant difference (p = 0.046), suggesting that students who use various communication methods may vary in their use of underlining or circling as a retention strategy. This implies that certain students may rely on this technique more than others, potentially due to variations in how visual or tactile strategies are applied depending on the communication method.

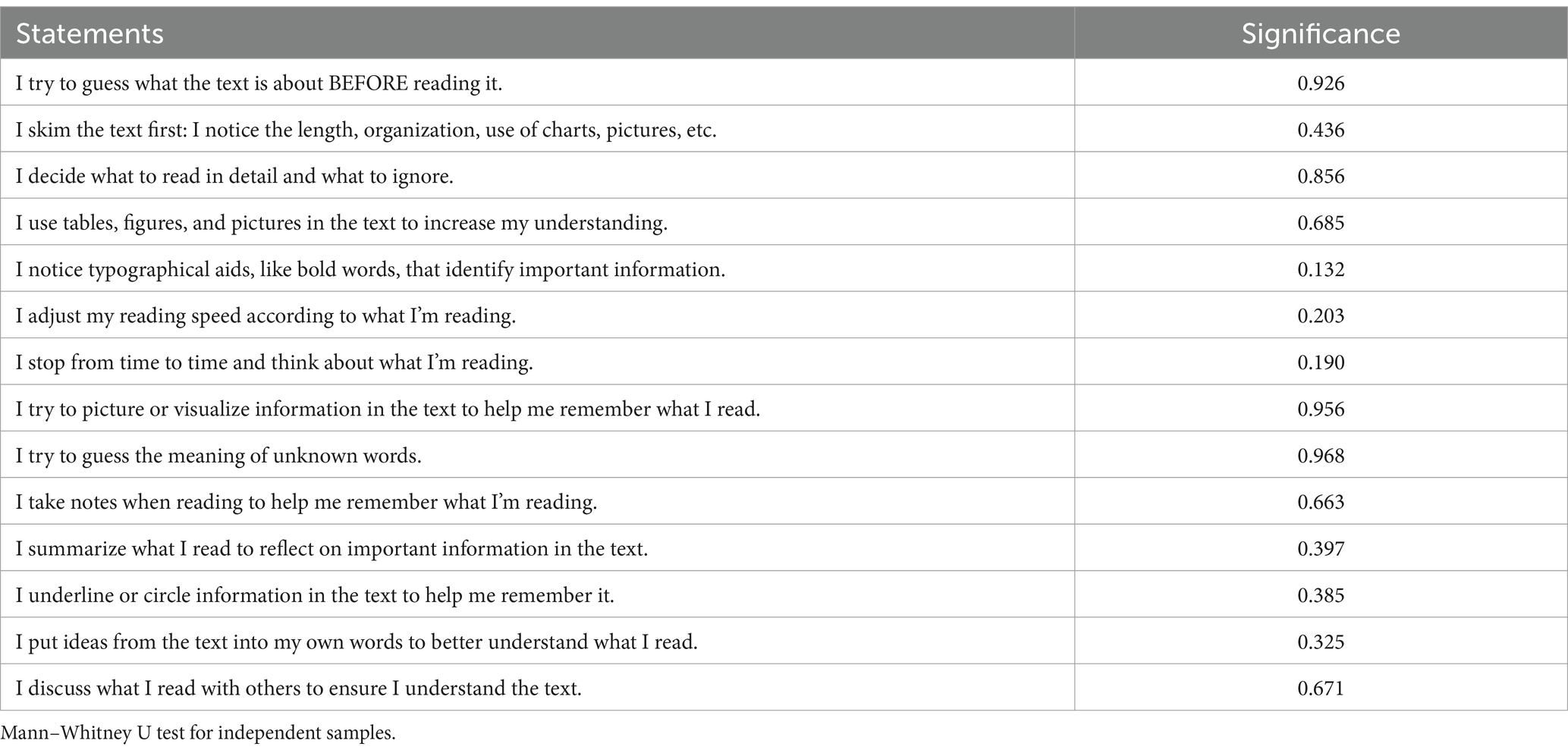

III. Hearing loss onset and strategy use

The null hypothesis for each statement assumes that there is no difference in strategy use based on the time of onset of hearing loss. For all reading strategies, the p-values are greater than the significance threshold of 0.05, leading to the acceptance of the null hypothesis in each case. This indicates that hearing loss onset does not have a statistically significant impact on the use of any specific reading strategy. However, the detailed findings indicate the what is the frequency of applying the pre-, during-, and post-reading strategies by DDH students. The results are as follows:

1. Pre-reading strategies:

“I try to guess what the text is about before reading it” (p = 0.926); “I skim the text first: I notice the length, organization, use of charts, pictures, etc.” (p = 0.436); “I decide what to read in detail and what to ignore” (p = 0.856).

There are no significant differences between students with pre-lingual and post-lingual hearing loss in terms of how they approach a text before reading. Both groups tend to use similar strategies for getting an initial sense of the content.

2. During-reading strategies:

“I use tables, figures, and pictures in the text to increase my understanding” (p = 0.685); “I notice typographical aids, like bold words, that identify important information” (p = 0.132); “I adjust my reading speed according to what I’m reading” (p = 0.203); “I stop from time to time and think about what I’m reading” (p = 0.190); “I try to picture or visualize information in the text to help me remember what I read” (p = 0.956); “I try to guess the meaning of unknown words” (p = 0.968).

The results show no significant variation in the use of strategies while reading. Both groups rely on visual aids, typographical cues, and self-monitoring techniques to a similar extent.

3. Post-reading strategies:

“I take notes when reading to help me remember what I’m reading” (p = 0.663); “I summarise what I read to reflect on important information in the text” (p = 0.397); “I underline or circle information in the text to help me remember it” (p = 0.385); “I put ideas from the text into my own words to better understand what I read” (p = 0.325); “I discuss what I read with others to ensure I understand the text” (p = 0.671). Post-reading strategies, such as note-taking, summarizing, and discussing, also show no statistically significant differences between students based on when their hearing loss occurred. Both groups appear to engage in similar reflective and interactive approaches to enhance reading comprehension (Table 4).

6 Discussion of the results

The study conducted reveals significant differences in the use of styles and strategies for developing reading comprehension among DHH students. In terms of the first research question (RQ1):

1. What types of reading strategies do DDH students apply in developing reading comprehension? (RQ 1.)

Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DDH) students often use a variety of reading strategies to develop reading comprehension. Some of the common strategies include:

• visualizing: DDH students may use mental imagery to create pictures or scenarios based on the text to improve understanding, especially since they often rely on visual cues for learning. e.g. “I try to picture or visualize information in the text to help me remember what I read (p = 0.156).”

• contextual clues: They often use the surrounding context of a word, sentence, or paragraph to infer meaning, particularly when encountering unfamiliar vocabulary or concepts. e.g. “I notice typographical aids like words in bold to identify important information (p = 1.000).”

• repetition and re-reading: Re-reading texts multiple times helps reinforce comprehension, allowing DDH students to process the information more thoroughly. e.g. “I skim the text first: I notice the length, organization, use of charts, pictures, etc. (p = 0.803).”

• graphic organizers: DDH students often benefit from using graphic organizers like charts, mind maps, or storyboards to structure information visually and clarify relationships between ideas. e.g. “I use tables, figures, and pictures in the text to increase my understanding (p = 297).”

• peer assistance: Collaborative reading with peers, including those who share the same language and experiences, helps in exchanging ideas and ensuring a clearer understanding of the text. e.g. “I discuss what I read with others to make sure I understand the text (p = 0.515).”

The research results confirm the scientific findings by Domagała-Zyśk (2013) and Dłużniewska (2016) who stated that implementing specific strategies for teaching and learning reading comprehension is essential. While commonly employed methods for working with deaf and hard-of-hearing students are valuable, they should be enhanced with strategies characteristic of glottodidactics. Notable strategies include the use of keywords, activating prior general knowledge, the “reading bath” technique, and reading texts focused on the experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. To conclude, researchers studying reading in deaf individuals consistently highlight that mastering reading comprehension presents a particularly significant challenge for this group. Despite ongoing emphasis within the education system on developing this skill, efforts to create effective strategies have yet to yield satisfactory outcomes. One possible reason for this is an overemphasis on debates surrounding the selection of the primary communication system for the linguistic and cultural minority of deaf people. This focus may divert attention from the critical issue—limited access to spoken language. This limitation poses a substantial obstacle to fully unlocking the intellectual potential of many deaf individuals (Krakowiak, 2017; Kamiński, 2021; Kołodziejczyk, 2021).

Regarding the second research question: What are the differences in reading strategies applications regarding the four variables, that is gender, degree of hearing loss, method of communication with the environment, and time of onset of hearing loss? (RQ 2.)

The obtained results indicate no statistically vital results regarding the gender and the time of onset of hearing loss variables of DDH students and the application of reading strategies. In the process of analysis, there are some crucial differences in terms of the degree of hearing loss and the method of communication with the environment.

Concerning the first mentioned, there are statistically significant results regarding the strategy “I notice typographical aids like words in bold to identify important information (p = 0.042).”

– Female students more often apply this strategy than male students.

– Students with severe hearing loss always apply this strategy.

– DHH students, who communicate via sign language or both (spoken and sign languages), apply the strategy “sometimes” or “always”

– Prelingually deaf use the strategy “sometimes”

Regarding the second mentioned variable, which is the method of communication with the environment, a significant number of DHH students who communicate via spoken language sometimes apply this strategy (60%). What is more, DHH students who communicate via sign language also state that this strategy is used quite often (64%).

Finally, as the scientific research by Czerniawska (1994) and Szymczak (2012) proves, the deliberate application of learning strategies enhances the efficiency of the DHH students’ learning process. These strategies enable individuals to absorb more information, organize their knowledge, gain deeper self-awareness, better understand their environment, and explore the world more extensively. They contribute to the satisfaction of achieving success. While they do not remove the need for effort, they foster a sense of agency and imbue actions with purpose.

Finally, concerning the third research question: What kind of general difficulties do DHH students encounter in the process of acquiring foreign languages based on the questions in the questionnaire? (RQ 3.) The results indicate that DHH students face a variety of challenges when acquiring foreign languages due to differences in auditory access, language processing, and educational support. Below are some general difficulties:

1. Limited Auditory Access

Almost all of the study participants (53 out of 55 participants) stated that they have difficulties with phonological awareness: DHH students often have limited exposure to the sounds of the target language, making it difficult to develop phonological awareness and reproduce sounds accurately. Additionally, significant challenges in developing listening skills were identified, with 30 out of 55 participants pointing out that difficulties in accessing auditory input impede the growth of listening comprehension, which is a crucial aspect of learning a foreign language.

2. Dependence on Visual Modalities

Some DHH students (21 out of 55 participants) indicated difficulties with lip-reading and sign language. They explained that relying too much on lip-reading or sign language may not accurately reflect the structure and grammar of a foreign language. Besides, a great number of study participants (45 out of 55 DHH students) pointed to visual overload as a major obstacle. The need to process information visually (e.g., reading, watching interpreters, or captions) often leads to cognitive overload.

3. Gaps in Foundational Language Skills

Several DDH students (22 out of 55) admitted that limited literacy skills in their native language impact their ability to learn grammar, syntax, and vocabulary in the foreign language.

4. Pedagogical Challenges

A large number of study participants (49 out of 55) pointed out the absence of tailored teaching materials as a challenge. Much of foreign language instruction depends largely on auditory methods, like listening exercises and oral practice, which may not be accessible to DHH learners. Additionally, some DHH students mentioned that certain foreign language teachers lack the training to modify their teaching methods for DHH students, such as incorporating visual aids, captioned videos, or sign language.

5. Social and Psychological Barriers

Finally, some DHH students (23 out of 55) admitted feeling excluded from group activities or conversations in the foreign language, reducing practice opportunities. Besides, there were some issues with motivation and confidence. Negative past experiences in language learning or a lack of role models fluent in multiple languages lead to reduction of motivation and self-efficacy.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, the study highlights significant insights into the reading strategies and challenges faced by Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) students in foreign language acquisition. The research confirms that DHH students employ a variety of strategies to develop reading comprehension, including visualizing, using contextual clues, repetition, graphic organizers, and peer assistance. These strategies align with prior research emphasizing the importance of tailored educational approaches for DHH students (Oxford, 1990; Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2012). However, the study also identifies gaps in current practices, particularly regarding the use of strategies for enhancing reading comprehension and the need for more inclusive teaching methods, such as incorporating visual aids and sign language (Dłużniewska, 2021; Kołodziejczyk, 2021).

Furthermore, the study reveals that the degree of hearing loss and the method of communication with the environment significantly influence the application of reading strategies. Notably, students with severe hearing loss and those using sign language or both spoken and sign language tend to apply certain strategies more frequently. However, no significant differences were found in relation to gender or the time of onset of hearing loss. These findings underline the need for customized strategies that consider the diverse communication methods and hearing profiles within the DHH student population (Krakowiak, 1995; Kamiński, 2021).

The study also outlines the general challenges DHH students encounter when acquiring foreign languages. Key difficulties include limited auditory access, dependence on visual modalities, gaps in foundational language skills, pedagogical challenges, and social and psychological barriers. These obstacles hinder the development of essential language skills, such as phonological awareness, listening comprehension, and grammar. Additionally, the lack of specialized teaching materials and insufficient teacher training further exacerbate these challenges (Karpińska-Szaj, 2024).

Overall, the results highlight the importance of developing more inclusive and accessible language learning strategies, as well as improving teacher preparation and support, to help DHH students overcome these barriers and achieve success in foreign language acquisition (Oxford, 1990; Dłużniewska, 2021). However, a more detailed exploration of practical classroom applications would greatly enhance the discussion for educators teaching DDH (Deaf and Hard of Hearing) students. For instance, teachers could implement differentiated instruction strategies by modifying the classroom environment with visual aids, sign language interpreters, and noise-reduction tools (Gaskell and Seymour, 2018; Mäki and Vuorinen, 2021). Bilingual approaches, such as using both sign language and spoken language, could be integrated into daily lessons, fostering inclusivity (Mäki and Vuorinen, 2021; Müller and Lütke, 2015). Collaborative learning activities, like peer tutoring or buddy systems, would encourage social interaction and academic support (Tveit and Schreiber, 2018). Additionally, using visual learning tools, adapted reading strategies, and formative assessments tailored to DDH students would promote engagement and understanding (Polack, 2015; Sanches and Lima, 2017). Emphasizing social–emotional support and self-regulated learning, alongside involving families and the community, would help create a holistic learning environment (Rönnberg and Josefsson, 2019; Traxler, 2000). Professional development and continuous training for educators in deaf education strategies would further equip them with the necessary skills to address the diverse needs of DDH students, ensuring that all students have equitable access to education and opportunities for success (Knoors and Marschark, 2014; Muto and Hara, 2018).

7.1 Limitations

The conducted research has its limitations – internal validity (differences among the participants resulting from their experiences in learning a foreign language, emotional maturity, as well as experience in acquiring knowledge) and external validity (small sample size). Bearing this in mind, the study sheds light on the styles and types of strategies used in foreign language learning by D/deaf and hard-of-hearing students and serves as a guide for teachers on how to work effectively.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it is personal data with no permissions obtained to share outside of the purposes for which it was collected. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to aXphYmVsYS5vbHN6YWtAa3VsLnBs.

Author contributions

IO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The reader will find a full description of the strategies in the publication: E. Domagała-Zyśk, Multilingual. Deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the process of learning and teaching foreign languages. Lublin, KUL 2013.

References

Aharony, N. (2006). The use of deep and surface learning strategies among students learning English as a foreign language in an internet environment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 851–866. doi: 10.1348/000709905X79158

Biggs, J. (1993). What do inventories of students’ learning process really measure? A theoretical review and clarification. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 63, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01038.x

Czerniawska, E., and Jagodzińska, M. (2007). Jak się uczyć? 1st Edn. Bielsko-Biała: Wydawnictwo Park Sp. z o.o.

Dłużniewska, A. (2016). “Rola języka w opanowywaniu umiejętności rozumienia czytanego tekstu przez dzieci i młodzież z uszkodzeniami słuchu w świetle Interaktywnego Modelu Czytania D.E” in Język i wychowanie. Księga jubileuszowa z okazji 45-lecia pracy naukowej Profesor Kazimiery Krakowiak. eds. W. E. Rumelharta, A. Domagała-Zyśk, and R. K. Borowicz (Lublin: KUL), 453–464.

Dłużniewska, A. (2021). Rozumienie tekstów literackich przez uczniów z uszkodzeniami słuchu. Kraków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls.

Domagała-Zyśk, E. (2013). Wielojęzyczni. Studenci niesłyszący i słabosłyszący w procesie uczenia się i nauczania języków obcych. Lublin: KUL.

Domagała-Zyśk, E. (2016). Głębokie i powierzchniowe strategie uczenia się języka obcego studentów niesłyszących i słabosłyszących. Rozpr. Społecz. 10, 31–35.

Domagała-Zyśk, E., and Podlewska, A. (2012). “Umiejętności polskich studentów z uszkodzeniami słuchu w zakresie posługiwania się mówioną formą języka angielskiego” in Student z niepełnosprawnością w środowisku akademickim. eds. K. Kutek-Sładek, G. Godawa, and Ł. Ryszka (Kraków: Wydawnictwo św. Stanisława BM), 147–159.

Gaskell, M., and Seymour, H. (2018). Deaf education in New Zealand: the role of New Zealand sign language. Deaf. Educ. Int. 20, 116–123. doi: 10.16953/dei.635

Kamiński, K. (2021). Teaching foreign languages to the deaf in Poland. Linguistische Treffen Wrocław 20, 217–226.

Karpińska-Szaj, K. (2024). Różnojęzyczność osób z uszkodzeniami słuchu w nauczaniu/uczeniu się języków obcych. Języki Obce w Szkole 2024, 123–128. doi: 10.47050/jows.2024.3.123-128

Knoors, H., and Marschark, M. (2014). Teaching deaf learners: psychological and developmental foundations. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Kołodziejczyk, R. (2021). Jak dzieci z uszkodzeniami słuchu radzą sobie z trudnościami językowymi? Nie głos, ale słowo (8). Lublin: KUL.

Krakowiak, K. (1995). Fonogesty jako narzędzie formowania języka dzieci z uszkodzonym słuchem. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

Krakowiak, K. (2012). Dar języka. Podręcznik metodyki wychowania językowego dzieci i młodzieży z uszkodzeniami narządu słuchu. Lublin: KUL.

Krakowiak, K. (2017). Niepełnosprawni we wspólnocie zmierzającej do solidarności i odpowiedzialności. Lublin: KUL.

Mäki, S., and Vuorinen, M. (2021). Educational inclusion of students with hearing impairments in Finland: the role of bilingual education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 502–516. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1622761

Miller, P. (2004). Processing of written words by individuals with prelingual deafness. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 47, 979–989. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/072)

Miller, P. (2005). What the word processing skills of prelingually deafened readers tell about the roots of dyslexia. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 17, 369–393. doi: 10.1007/s10882-005-6620-9

Monk, S., and Sims, E. (2020). Educational practices for deaf and hard of hearing students in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Deaf Educ. 24, 29–43. doi: 10.1002/dei.1215

Müller, F., and Lütke, H. (2015). Education of deaf students in Germany: a comparison of oral and bilingual approaches. Int. J. Deaf Stud. 19, 413–425. doi: 10.1093/deafed/env027

Muto, A., and Hara, T. (2018). Deaf education in Japan: challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 33, 143–156.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Oxford, R. (1992/1993). Language learning strategies in a nutshell: update and ESL suggestions. TESOL J. 2, 18–22.

Oxford, R. (2001). “Language learning styles and strategies” in Teaching English as a second or foreign language. ed. M. Celce-Murcia (Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle), 359–366.

Piłatowska, M. (2008). Świadomość stylów uczenia się - korzyści dla nauczyciela i studenta. Acta Univ. Lodz. 217, 121–132.

Polack, S. (2015). Education of deaf learners in South Africa: barriers to inclusion. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 20, 240–252. doi: 10.1093/deafed/env026

Rönnberg, J., and Josefsson, J. (2019). Swedish bilingual education for the deaf: policies and practices. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 24, 307–316. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enz010

Sanches, G. P., and Lima, J. D. (2017). Bilingual education for deaf students in Brazil: policies and practices. Rev. Bras. Educ. 22, 559–574. doi: 10.1590/S1413-24782017227025

Szymczak, J. (2012). Świadome i autentyczne uczestniczenie w procesie uczenia się. Specyfika i znaczenie strategii uczenia się. Forum Dydaktyczne 9-10, 133–149.

Traxler, C. B. (2000). The Stanford achievement test, 9th edition: national norming and performance of deaf and hard-of-hearing students. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 5, 337–348. doi: 10.1093/deafed/5.4.337

Keywords: learning styles, educational strategies, reading comprehension, foreign language learning, students with hearing impairments

Citation: Olszak I and Borowicz A (2025) Learning styles and strategies of D/deaf and hard of hearing students in foreign language acquisition–a research report. Front. Educ. 10:1553031. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1553031

Edited by:

Katarzyna Karpińska-Szaj, Adam Mickiewicz University, PolandReviewed by:

Angela Sileo, University of Milan, ItalyNuzha Moritz, Université de Strasbourg, France

Copyright © 2025 Olszak and Borowicz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Izabela Olszak, aXphYmVsYS5vbHN6YWtAa3VsLnBs

†ORCID: Izabela Olszak, orcid.org/0000-0002-8504-7814

Aleksandra Borowicz, orcid.org/0000-0003-0587-0665

Izabela Olszak

Izabela Olszak Aleksandra Borowicz2†

Aleksandra Borowicz2†