- 1Queens College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

- 2Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

Background: In higher education, feedback has become a significant focus of study over the years. Despite established high-quality feedback criteria, the issue of students not utilizing feedback from instructors and peers persists. This study identifies key barriers to feedback utilization and offers insights that can inform more responsive and student-centered feedback practices.

Aims: This study investigated specific reasons behind feedback rejections in higher education and how individual characteristics (college students' gender, ethnicity, and academic level) predicted the reasons to reject teacher and peer feedback.

Methods: Undergraduate and graduate students (N = 200, 67.7% women) from various colleges within a large public university in the northeast of the USA were asked to describe possible reasons why they did not use feedback provided by their instructors and peers' feedback on an academic assignment. Students' responses were analyzed using a deductive approach with a coding system based on the Student-Feedback Interaction Framework.

Results: Students tend not to use or reject teacher feedback due to ambiguous or unclear messages, negative tone, lack of respect or trust in the teacher, and confidence in their performance. Peer feedback is commonly rejected because of a perceived lack of peer expertise, ambiguous messages, and negative emotional responses. Multiple logistic regressions found that gender and educational level are significant predictors of reasons for not utilizing feedback, with distinct patterns observed among male students and undergraduates.

Conclusion: This study underscores the need for feedback strategies addressing individual student characteristics and contextual factors. Recommendations include fostering positive teacher-student relationships, enhancing the clarity of feedback, and improving students' skills in peer feedback provision and utilization.

Introduction

Over three decades of research have demonstrated that effective feedback has the potential to significantly enhance students' learning and achievement (Black and Wiliam, 2009; Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Wisniewski et al., 2020). Feedback has been defined, explored, and situated within operational models, with much of the research in instructional settings focusing on teacher-provided feedback and its informational content. However, it has become increasingly clear that delivering information alone is insufficient without opportunities for purposeful application and improvement (Nicol et al., 2014). The student has always been integral to the feedback process, both as a recipient and as an active agent. This dual role is reflected in empirical studies and meta-analyses (e.g., Ajjawi and Boud, 2017; Heitink et al., 2016; Lam, 2017; Winstone et al., 2017). Importantly, even the most meticulously crafted feedback has no meaningful impact if the student is unwilling or unable to engage with it. To deepen our understanding of the conditions that foster effective feedback, this study examines higher education students' reasons for not utilizing teacher and peer feedback and explores the individual variables that underpin these decisions. Understanding the reasons why students do not effectively engage with feedback is essential for developing tailored strategies that enhance the effectiveness of instructional feedback provision. This study contributes to the field by identifying key barriers to feedback utilization and offering insights that can inform more responsive and student-centered feedback practices.

Student-feedback interaction

Feedback operates as a dynamic system, with its effectiveness determined by how its elements interact as the feedback moves from source to student processing. Several models have been developed to explain the feedback formation, delivery, and implementation of feedback within educational settings (e.g., Lipnevich and Panadero, 2021; Panadero and Lipnevich, 2022). This study is framed using the Student-Feedback Interaction Model (Lipnevich and Smith, 2022), which details the way students engage with feedback and identifies key factors influencing its uptake and application. Specifically, this model considers that feedback is not merely a transmission of information but unfolds within a dynamic interaction of context, feedback sources, message, learner characteristics, and outcomes (see Supplementary Figure S1).

Feedback context

The context in which feedback occurs shapes its impact, as variations in course structure, domain norms, and cultural factors play significant roles (Yang and Carless, 2013; Parkes, 2018). In higher education settings, feedback practices are often constrained by contextual factors such as time limitations and the educators' workload, which can impact the quality and timeliness of feedback provided (Henderson et al., 2019). As noted by Winstone et al. (2017), feedback is often delivered in ways that limit its applicability, such as being provided too late for use in future assessments, involving minimal follow-up, relying on standardized forms perceived as impersonal, or subordinated to other course processes. Moreover, Winstone and Boud (2020) highlighted that feedback is often entangled with assessment, leading to an emphasis on grades rather than learning. Similarly, Morris et al. (2021) showed that while schools prioritize academic progress through exam results, universities balance academic achievement with factors like student satisfaction and perceived value for money. While this emphasis on satisfaction may improve perceptions of feedback, it can sometimes detract from the development of practical feedback strategies and actionable insights for improvement (Price et al., 2011). Additionally, students encounter barriers to utilizing feedback effectively, primarily due to a lack of strategies or understanding of academic discourse (Jonsson, 2013). These conditions contribute to students' rejection of feedback, as students may view it as irrelevant, disconnected, or lacking effort. These findings underscore how contextual factors influence the feedback system at every level (Lipnevich and Smith, 2018, 2022).

Feedback source

Feedback can originate from diverse sources, including technology-based systems, teachers, peers, or self-assessment (Cutumisu et al., 2017; Lipnevich and Lopera-Oquendo, 2022; Nicol, 2020). Among these, the perceived credibility of the source significantly affects how students engage with feedback. Teacher feedback, for instance, is often more valued when the teacher is seen as knowledgeable and invested in the student's progress (Amerstorfer and Freiin von Münster-Kistner, 2021; Vareberg et al., 2023). A strong teacher-student relationship further enhances feedback's perceived fairness and utility (Pat-El et al., 2012).

Peer feedback, on the other hand, aligns with Vygotsky (1962) sociocultural theory, emphasizing learning through social interaction. Research highlights its benefits, such as improving academic performance (Double et al., 2020) but also emphasizes its challenges. Students often question the trustworthiness and accuracy of peer assessment and feedback (Dijks et al., 2018; Rotsaert et al., 2017). At the same time, anonymity in peer feedback can mitigate some of these concerns, although it may reduce opportunities for social learning and affect regulation (Panadero and Alqassab, 2019). Despite its complexities, peer feedback remains a valuable complement to teacher feedback, providing diverse perspectives and fostering a collaborative learning environment. Ensuring its effectiveness requires addressing students' concerns about evaluative capabilities and interpersonal dynamics. In sum, understanding the conditions under which feedback from teachers and peers is embraced (or not) can help educators design strategies that minimize rejection and maximize meaningful engagement, ultimately enhancing the feedback process.

Feedback message

Research has consistently emphasized that feedback's effectiveness depends on a combination of factors that shape how it is received and utilized. Moreover, there is a growing recognition that not all feedback is equally effective, so its impact also depends on how it is structured and delivered. In that sense, feedback features such as content, timing, tone, and orientation interact with the unique characteristics of each student. This interplay not only influences how feedback is perceived but also shapes students' learning outcomes.

Tailoring feedback to the individual student is a critical first step, as personalizing feedback to their specific work fosters greater engagement and allows them to see the relevance of the comments (Ferguson, 2011; Li and De Luca, 2012). However, personalization alone is not sufficient. Feedback must also be comprehensive and precise, providing students with clear insights into their performance and highlighting areas for improvement (Ferguson, 2011; Dawson et al., 2019). At the same time, clarity is key, as feedback that is overly vague or general can leave students uncertain about what changes to make (Máñez et al., 2024).

Equally important is the timing of the feedback. Delivering feedback soon after a task is completed ensures that students can apply it while the material is still fresh in their minds. Research has shown that timely feedback increases its likelihood of being acted upon, contributing to improved learning outcomes (Gibbs and Simpson, 2004; Poulos and Mahony, 2008). However, the question of whether feedback should be immediate or delayed is more complex than it may seem. While immediate feedback is often thought to lead to faster improvements, recent studies have demonstrated that the timing of feedback may not make as significant a difference as previously believed. A study conducted across 38 college classes found no overall learning benefit to immediate feedback, suggesting that other factors, such as the nature of the feedback and its alignment with learning objectives, are more crucial (Fyfe et al., 2021).

Furthermore, feedback must be based on clear, specific criteria to be truly effective. Students are more likely to use feedback to improve their work when they understand how it relates to predefined expectations and performance standards (O'Donovan et al., 2001; Poulos and Mahony, 2008). In this regard, feedback should not only assess past performance but also direct attention to how improvements can be made, encouraging students to think about future learning and growth (Dawson et al., 2019; Lizzio and Wilson, 2008). This future-oriented focus can help foster a growth mindset, where students view feedback as a tool for ongoing development rather than as a judgment of their abilities (Máñez et al., 2024).

The tone in which feedback is delivered also plays a significant role in how it is received. Research indicates that feedback with a supportive, constructive tone is more likely to engage students and promote positive learning behaviors, while overly authoritative or dismissive tones can hinder students' receptivity (Jonsson, 2013; Lipnevich et al., 2016; Winstone et al., 2016). Positive feedback is particularly effective in encouraging engagement, though it is important to strike a balance. Excessive praise, while initially motivating, may lead to complacency, as students may feel that they do not need to improve further (Jonsson, 2013; Lipnevich and Smith, 2022; Lipnevich et al., 2023). On the other hand, more critical comments, though initially difficult to accept, have been shown to drive meaningful improvement (Drew, 2001; Higgins et al., 2001).

The distinction between task-level and process-level feedback also merits attention (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). Task-level feedback addresses the specific content or details of the student's work, while process-level feedback focuses on the strategies and methods used to complete the task. Both types of feedback are important, but they serve different purposes. Feedback that focuses on the task itself is particularly valuable for clarifying performance expectations and helping students refine their work (Jonsson, 2013; Walker, 2009). In contrast, process-level feedback encourages reflection on the learning process, helping students develop the skills and strategies needed for future tasks (Winstone et al., 2016).

Despite the importance of detailed feedback, the sheer volume of comments can be counterproductive. Overly lengthy feedback risks overwhelming students, making it harder for them to identify the most critical aspects of their performance (Vardi, 2009). Moreover, while detailed feedback often leads to more revisions, it does not automatically guarantee that the revisions will improve the quality of the work (Ferris, 1997; Treglia, 2009). It seems, then, that quality feedback may be more important than quantity.

In summary, effective feedback is a dynamic and multifaceted process that requires careful attention to its content, timing, tone, and alignment with students' expectations. When feedback is personalized, clear, constructive, delivered at an appropriate time, and with an accessible tone, it can significantly enhance learning. However, this is not a one-size-fits-all approach. The interaction of these factors with the student's unique characteristics ultimately shapes their perception of feedback and its impact on their learning.

Student characteristics

Each student brings unique characteristics to the feedback process, influenced by their culture, subculture, community, family, peer group, and personal traits. Understanding how these factors intersect with feedback is crucial to recognizing how students respond emotionally and cognitively to feedback. Traits such as emotional stability, feedback receptivity, and self-regulation play a significant role in determining how feedback is processed and acted upon (Clark, 2012; Goetz et al., 2018). Over the past 15 years, research has identified various learner traits that mediate the feedback process, some directly related to feedback and others more tangential. These include achievement levels (Shute, 2008), optimism (Fong et al., 2018), subject-specific abilities, prior success, and receptivity to feedback (Lipnevich et al., 2016). Other factors such as intelligence, learning strategies, self-efficacy, and motivation also impact how feedback is approached (Lipnevich and Lopera-Oquendo, 2022; Schneider and Preckel, 2017; VandeWalle and Cummings, 1997).

However, the literature concerning how students' individual characteristics, such as their gender, ethnicity and academic level may influence their academic feedback experiences is limited. For instance, Sortkær and Reimer (2022) explored the potential impact of gender and found that boys received the highest amount of feedback from teachers, whereas girls received the most feedback from their peers. In relation to gender influences on the rejection of feedback, Lundgren and Rudawsky (1998) examined whether male and female college students differed in their responses to negative feedback from parents and peers, considering factors such as relationship closeness, feedback characteristics, and emotional reactions. While no direct gender effect was found on students' refusal to use feedback, women exhibited greater tendency to not act upon feedback due to indirect factors. For example, women were provided with feedback on more important topics (which typically reduced rejection) but also experienced more negative feedback and stronger emotional responses, both of which contributed to higher rejection rates. Moreover, for Black students, particularly men, trust in teachers was shown to be crucial. A lack of trust led to academic disidentification, where students disconnected their academic self-concept from their GPA, potentially leading to dismissing feedback (McClain and Cokley, 2017). Additionally, the results suggested that feedback practices were shaped by classroom composition, including the gender distribution and the overall socioeconomic background of students.

Students value feedback for a variety of reasons, which can shape their approach to it. Rowe (2011) identified seven key themes from a survey of over 900 undergraduate and graduate students: feedback as a guide to good grades, as a learning tool, as a form of academic interaction, as encouragement, as a means to regulate anxiety, as a sign of respect, and as a signal that the instructor cares about their work. These motivations highlight the multifaceted role that feedback plays in students' academic and emotional lives.

It is also crucial to consider how feedback interacts with students' expectations. When feedback aligns with students' prior expectations, whether based on previous feedback, rubrics, or their own goals, it is more likely to be well-received. However, mismatches between expected and received feedback can lead to confusion or frustration, diminishing the effectiveness of the feedback provided (Lipnevich et al., 2016). Similarly, the presence of grades as a form of feedback can complicate the process. Students often focus more on grades than the accompanying comments, which can detract from the value of the feedback itself. Studies have shown that anticipating grades can diminish motivation, especially when students expect positive reinforcement from feedback but instead receive an evaluative response (Lipnevich and Smith, 2009a,b).

Feedback processing

The key element of the Student Feedback Interaction Model (Lipnevich and Smith, 2022) involves how students perceive, interpret, and respond to the feedback they receive. This process is influenced by the context, source, and characteristics of both the feedback and the student (Lipnevich and Smith, 2022; Lui and Andrade, 2022; Nicol, 2020). The cognitive aspect of feedback processing involves students comprehending the feedback, reflecting on its applicability to their current and future work, and considering how it can be generalized to new contexts. The value and utility of feedback play a central role in shaping both students' emotional responses and their subsequent actions (Pekrun, 2006). Comparisons made between teacher comments, rubrics, and other feedback sources enable students to engage in self-assessment and internalize feedback, guiding future revisions and efforts (Nicol and McCallum, 2022).

Affective processing refers to the emotional reactions students have to feedback, which can impact both their motivation and their subsequent behavior. According to Cognitive-Behavioral Theory (CBT), feedback can evoke strong emotional responses, which in turn affect achievement-related behaviors (Pekrun, 2006). A positive emotional response to feedback, especially when the student understands and feels supported by it, increases the likelihood of engagement with the task. Negative emotional responses, however, can hinder this process and lead to disengagement or avoidance (Ajjawi and Boud, 2017; Brookhart, 2011; Carless and Boud, 2018; Evans, 2013).

Finally, behavioral processing involves students' specific actions in response to feedback. These actions may include rereading the feedback, making revisions, seeking additional help, or even choosing to disregard the feedback altogether. The effectiveness of these responses is influenced by factors such as the clarity of the feedback, its alignment with expectations, and the overall emotional tone (Lipnevich and Smith, 2009a; Price et al., 2017; Graham et al., 2015).

The Student-Feedback Interaction model emphasizes the interplay among the context, source, message, student, and their processing of feedback. Together, these elements shape how feedback is understood, accepted, and applied to improve learning outcomes. While this model offers a robust framework for designing and delivering effective feedback, it also highlights potential barriers to its acceptance. In the next section, we address the critical issue of reason for not using feedback, examining the factors that lead students to resist or dismiss feedback and its implications for learning.

Reasons for feedback rejection

In this study, feedback rejection refers to the deliberate or unintentional disregard, dismissal, or failure to engage with feedback provided by teachers or peers. This can manifest through explicit refusal, passive inaction, or misinterpretation that prevents meaningful incorporation of the feedback into subsequent learning or performance.

Among the most significant reasons is the negative emotional responses feedback can evoke (Lipnevich and Smith, 2009b). When students feel discouraged, upset, or overly criticized, they are more likely to ignore or reject the feedback provided. This challenge is particularly pronounced for international students, who often perceive feedback as harsher compared to their domestic peers (Zacharias, 2007). Similarly, students receiving grades lower than expected may experience feelings of sadness, shame, or anger, which further diminishes their willingness to engage with feedback. Negative emotional reactions, therefore, play a critical role in feedback rejection, as they inhibit constructive engagement and learning (Ryan and Henderson, 2018).

Cognitive barriers also hinder a students' ability to act on feedback. Many students struggle to understand the academic language and complex terminology often used in feedback, leading to frustration and disengagement. Feedback perceived as too effortful to decode or implement can deter students from seeing its value or applying it meaningfully (Winstone et al., 2017). Additionally, when feedback lacks relevance or specificity, such as general comments or guidance that does not align with their priorities, students may view it as unhelpful and dismiss it (Jonsson, 2013).

Psychological processes, including students' sense of agency and willingness to exert effort, further influence feedback acceptance. Students who feel powerless or unsupported in their learning may reject feedback as they see little connection between their actions and improvement. Social and contextual dynamics, such as the quality of the relationship with the feedback giver or the perceived fairness of the process, can also amplify resistance (Coombes, 2021). For instance, overly critical feedback from peers or parents or time constraints that limit meaningful discussion of feedback can exacerbate rejection.

While these factors provide valuable insights, research on the reasons to reject feedback remains limited and often lacks methodological rigor. Many studies rely on small sample sizes or do not fully capture the complexity of the feedback process (Van der Kleij and Lipnevich, 2021). To address these gaps, the present study was conducted.

Current study

Feedback is a critical component of the learning process, as it provides students with the necessary information to improve and develop their skills. However, for feedback to be beneficial, it must be effectively received and utilized by students. While a substantial body of research has identified what learners need to accept feedback, there is a gap in understanding the specific reasons behind students reasons for rejecting the feedback. Much of the existing literature on feedback assumes that the reasons for rejection are merely the inverse of those for accepting feedback. However, this approach may oversimplify the issue, especially given that rejecting academic feedback can often be emotionally driven. As Hernandez et al. (2018) noted, “well-being is not simply the flipside of negative affect or ill-being” (p. 20), suggesting that emotional responses to feedback should not be treated as opposites of positive acceptance.

To address this gap, the aim of our mixed methods study was 2-fold. First, through open-ended questions, we sought to gain a deeper understanding of why higher education students reject feedback provided by both teachers and peers about their academic assignments. Second, we explored how individual characteristics, such as gender and academic major, might influence students' reasons for rejecting feedback. By investigating these factors, we aimed to provide more nuanced insights into the complex dynamics of feedback rejection issues. To guide this study, we proposed three research questions:

(1) What reasons do college students have for rejecting the feedback provided by their instructors?

(2) What reasons do college students have for rejecting the feedback provided by their peers?

(3) To what extent do college students' gender, ethnicity, and academic level predict the reason to reject teacher and peer feedback?

Method

Participants

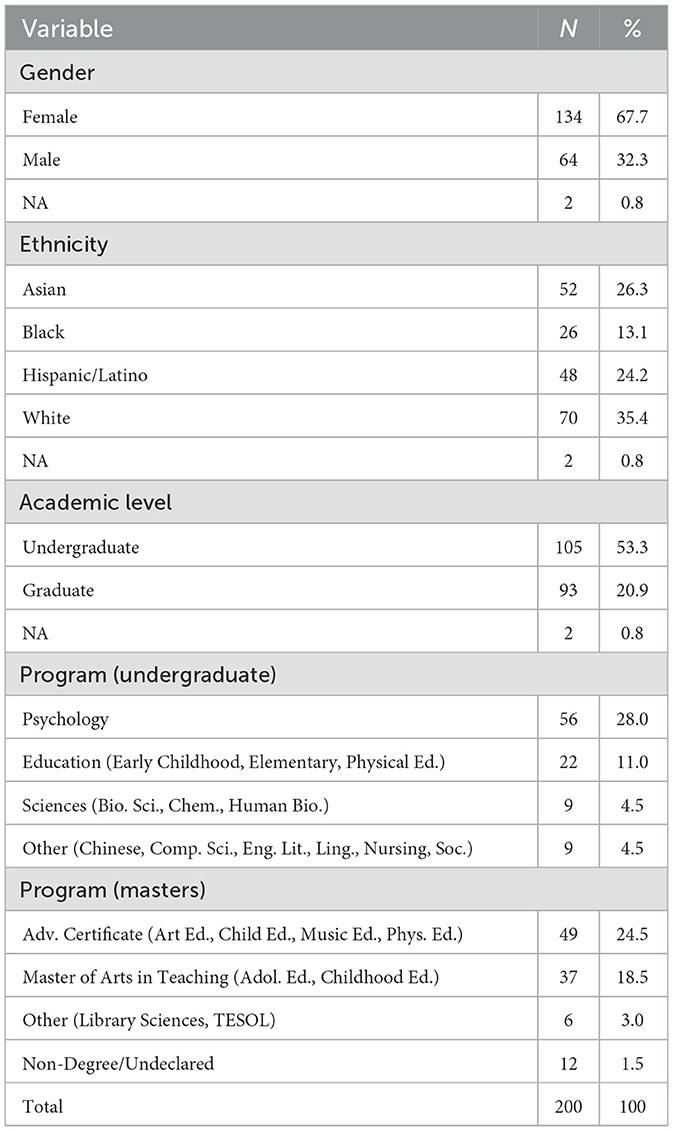

A total of 200 undergraduate and graduate students from various colleges within a large public university in the northeast of the USA participated in the study. Demographic information for 198 participants (99%) was obtained from academic records (Table 1). The sample consisted of 67.7% women (N = 143), 53% (N = 105) enrolled in undergraduate programs, and 35.4% identified as White. Among undergraduates, the most common majors were Psychology (28.0%), and Education (11 %). For graduate students, the most frequently pursued programs were the Advanced Certificate in Education (24.5%) and the Master of Arts in Teaching Childhood Education (18.5%).

Procedure

In this study, as part of an academic activity during class, participants were inquired with the following open-ended questions:

(1) Please think of academic situations in which you rejected the instructor's feedback. Why did you choose not to incorporate the instructor's comments? Describe three possible reasons why you did not use feedback.

(2) How about peer feedback? Please describe specific situations in which you rejected a peer's feedback on an academic assignment.

This task was part of the course requirements and was expected to be taken seriously by the students. While all students completed the task, only those who provided informed consent were included in the study. All participants received extra credit for their involvement in the activity. The Institutional Review Board approved the study (protocol number 2023-0661-QC).

Qualitative data coding

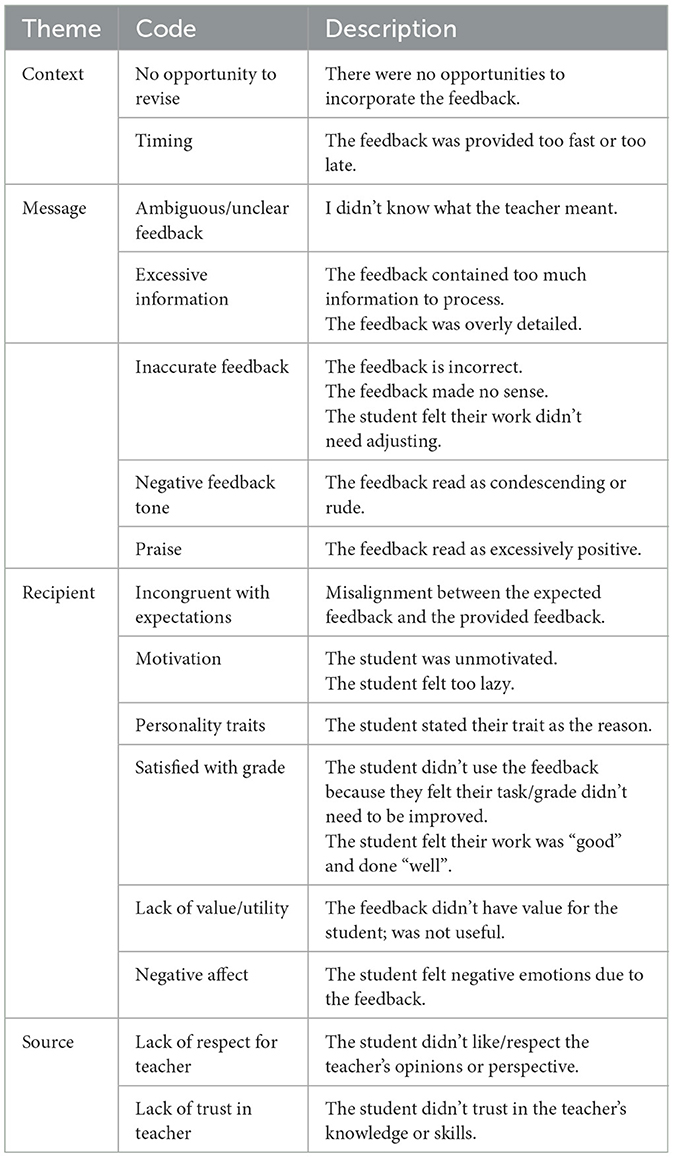

The participants' open-ended responses about the two dimensions of analysis (teacher feedback and peer feedback rejection reasons) were analyzed using a deductive approach with a coding system based on the feedback model provided by Lipnevich and Smith (2022). This model served as the theoretical framework for defining the dimensions of analysis and their respective codes. Tables 2, 3 present the definitions of codes by dimension. Supplementary Tables S1, S2 also display examples of sentences for each code.

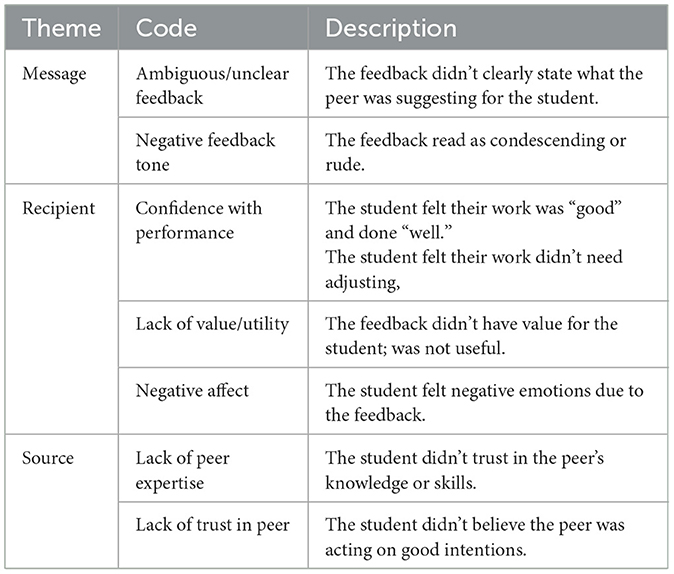

Table 3. Description of themes and codes used to code responses about reasons for rejecting peer feedback (question 2).

A total of four themes were defined to code the responses about the reason rejected teachers: context, message, source characteristics, and recipient's characteristics, while responses about peer feedback rejection were coded within the themes message, source, and recipient's characteristics. Fifteen codes were used to classify participants' responses regarding rejecting teachers' feedback, while eight codes were used to classify responses related to the reason for rejecting peer feedback. Open-ended response coding was conducted separately for teacher- and peer feedback-related reasons based on the task. The unit of analysis for coding was defined as a sentence rather than a complete participant response to ensure consistency across coders.1

A total of 185 and 123 participants provided responses regarding reasons for rejecting teacher and peer feedback rejection reasons, respectively. Two researchers from the team classified 706 sentences related to teacher feedback and 265 sentences related to peer feedback using ATLAS.ti (version 23.2.1) software. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Krippendorff's α coefficient, a nonparametric measure of agreement (Hughes, 2021) provided by ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH (2023). The coding process was divided into four rounds. First, the coders classified 10 common responses to calibrate and review the coding system (Krippendorff's α = 0.712). A meeting was held with all authors to discuss discrepancies and agree on final codes. Second, an additional set of 10 responses were jointly classified, showing and acceptable agreement (Krippendorff's α = 0.849). A third round, with 15 common responses, was additionally conducted, obtaining an acceptable agreement (Krippendorff's α = 0.899). Finally, the remaining responses were evenly distributed between the two coders, with 20 random responses coded jointly, leading to an acceptable agreement (Krippendorff's α = 0.800). Discrepancies were solved through discussions with coders.

Data analysis

First, we examined descriptive information about participants' responses regarding reasons for rejecting teacher and peer feedback and presented a qualitative analysis focusing on the rationality and examples behind each coding category derived from our thematic analysis approach. Second, to answer the first and second research questions, frequencies for each code for the total sample and by participant's gender and academic level were calculated. Z-tests to compare observed proportions were then estimated. Finally, we conducted multiple logistic regression to examine the third research question. Models using a binomial distribution were fitted to estimate the main effect of gender, ethnicity, academic level, and GPA on the probability of providing reasons for rejecting teacher or peer feedback due to aspects related to each dimension of analysis. The proportion of codes in each dimension was used as a dependent variable (which is an event/trial form variable rather than a binary observation), whereas student's gender, ethnicity, academic level, and GPA were used as predictors. Further, Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) and Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) distributions were estimated to deal with the overabundance of zero counts in some subcategories. Model goodness of fit statistics was calculated for selecting the best model fit by subcategory. Better models correspond to smaller Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Friendly and Meyer, 2015). Plot analyses were also generated to check model assumptions. All the analyses were conducted using R software version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021).

Results

Descriptive statistics

A total of 200 participants took part in the study, with 192 providing valid responses. Specifically, 185 participants responded to questions about rejecting teacher feedback, while 123 provided responses regarding peer feedback rejection reasons. In total, 706 sentences related to teacher feedback and 265 sentences related to peer feedback were identified and coded.

On average, participants gave 3.8 sentences when explaining reasons for rejecting teacher feedback (M = 3.8, SD = 2.5, range = 1–16) and 2.15 sentences (M = 2.15, SD = 1.26, range = 1–7) when addressing reasons for rejecting peer feedback. This resulted in a total of 806 codes being identified in the teacher feedback responses (M = 4.6, SD = 2.8, range = 1–16) and 287 codes (M = 2.33, SD = 1.35, range = 1–8) for the peer feedback responses.

Qualitative results

This study aimed to identify common themes in students' reasons for rejecting feedback from their peers and instructors (Tables 2, 3). By coding student responses, we identified overarching themes that align with the Student-Feedback Interaction framework (Lipnevich et al., 2023).

Students' reasons for rejecting instructor feedback in an academic setting

A major finding immediately stands out: of the 706 phrases coded regarding the reasons to reject teacher feedback, the “Message” accounted for the largest proportion of coded phrases (352), followed closely by “Recipient” (341), “Source” (112), and “Context” (43). Therefore, the dominance of the “Message” and “Recipient” categories, which together accounted for the majority of coded phrases, highlights that both the feedback content and the student's characteristics are imperative factors in feedback acceptance. It is noteworthy that participants responded based on their own experiences, without being unaware of any categories or seeking to assign responsibility to themselves or their instructor.

Context

The “Context” theme generated the fewest aggregate codes, with a total of 43, incorporating only instances where students reported inappropriate timing or no opportunity to revise. For the timing category, we focused on statements where the students complained about receiving feedback too early, at times not allowing the student to complete their assignment—“...a teacher gave me feedback before I even started my presentation.” or too late, for instance “Another reason why I didn't use the feedback was that I had done the assignment a month prior, and feedback was given a month later.” Moreover, statements coded in this theme also included instances in which the respondents focused on the issue of no opportunity to revise, as seen in: “wouldn't have even been able to apply the feedback” because it was the “final paper for our class.”

Source

This theme encompasses codes describing both the lack of respect for teacher and the lack of trust in teacher as it focuses on the students' perceptions regarding their instructor. The first code captures instances where students expressed dislike for the teachers themselves and their opinions or perspectives. The second focuses on a lack of trust in the teacher's knowledge or skills. The difference between those categories is evident when looking at examples of participants' statements. Fitting within the first code, one respondent stated, “...if I don't like them as a teacher then I also may not want to take their feedback.” This illustrates how students' negative perceptions of the teachers could lead to the rejection of instructional feedback. In contrast, for the latter code, responses included statements such as: “I chose not to implement their feedback since this teacher couldn't demonstrate their own concepts….” This example highlights a lack of trust in the instructors' competence and expertise. A total of 112 statements were coded within this theme, demonstrating that the student perception of the instructor is a critical factor in their decision to engage with instructional feedback.

Message

We identified five different codes that fit within the “Message” theme, and they accounted for a total of 352 of the coded sentences. Within this theme, the most prominent reason for rejecting feedback, cited by 161 respondents, was its lack of accuracy. Responses that addressed the correctness of the feedback or expressed students' disagreement with it were coded under Inaccurate Feedback. That is, statements coded as inaccurate feedback reflected instances where students identified discrepancies between their work and the feedback provided. For example, one respondent explained that they had misnumbered their responses, but after comparing answers with another student, they realized their work was correct, just in a different order. The respondent noted, “Another student had the same answer, and he said she was correct.”

The code, ambiguous/unclear feedback also emerged as a prominent reason for rejecting feedback, encompassing 115 responses, making this the second-most cited issue. Students' responses consistently highlighted how feedback lacked comprehensibility, with comments such as: “not clear enough,” “wasn't very detailed,” or “did not understand what they meant.” The respondents explained how this lack of comprehensibility led to them not engaging with the feedback.

Negative feedback tone emerged as a significant issue for rejecting instructor feedback. Respondents described experiences where instructors focused solely on the negative aspects of their work - “I had an instructor cross out an entire paragraph and only wrote negative things about it”; be worded negatively - “...completely negative especially the way it was worded…”; or use language that would be identified as negative - “What I had received were insults….” Unlike in the negative affect category, the statements coded as negative feedback tone did not necessarily evoke negative emotional responses in students (participants did not indicate how those situations affected them emotionally). Instead, they were deemed dismissive, rejective, or too pessimistic.

The amount of feedback received also emerged as a significant reason for participants to reject feedback and was coded as excessive information. Excessive feedback can make students feel overwhelmed and unsure of which aspect to address first. It can be difficult for them to focus on what matters, or they might not read the feedback because it appears lengthy. We identified 11 responses of excessive information, including instances such as “...too much information…” and “too many repetitive comments.”

The final code that fits into the “Message” theme was praise. Praise was a less frequently cited reason for rejecting feedback, appearing only in four responses, but still noteworthy. Participants reported rejecting feedback that contained “...positive praise…,” “...receiving compliments…,” or when they were said to be “...doing amazing….” but these assessments felt overly positive and made students doubt the authenticity of all feedback.

Recipient

Respondents frequently acknowledged personal factors as reasons for rejecting feedback, often taking responsibility for their decisions. A total of 341 sentences were coded in six categories within this theme, highlighting various individual characteristics that influenced their predisposition to reject feedback.

The most common reasons cited was satisfaction with grades, with 111 responses reflecting this idea. Students reported believing that their performance had met expectations or felt their work was “spot on,” and there was no need to engage with the feedback further. Participants statements include “I didn't feel the need to redo my work just to get it one point higher.” and “I was confident in my work and didn't feel that the suggestion was necessary.”

Emotional reactions also played a key role, with 68 responses reporting how negative affect influenced their rejection of feedback. Students described experiencing emotions such as fear, frustration, embarrassment, confusion, and sadness. These feelings often arose from feedback that made them feel judged or criticized. One respondent articulated the broader implications of this dynamic, stating, “This type of feedback gives a negative relationship between the teacher and the students.”

Another reason for rejecting feedback was its perceived lack of value or utility, with 54 responses indicating this issue. After processing the feedback, some students decided it was neither helpful nor necessary. For example, one student noted, “the feedback I received was useless – it doesn't help me any way.”

Individual personality traits were also cited as a reason for rejecting feedback in 50 responses. Participants described themselves using adjectives such as prideful, stubborn, shy, nervous, embarrassed, skeptic, and timid, attributing their aversion to feedback to inherent characteristics or traits shaped by their upbringing. Additionally, some students noted how their mental and emotional wellbeing at the time of receiving feedback impacted their ability to engage with it, as reflected in comments like, “I was struggling mentally and emotionally at the time.”

Lack of motivation was identified as another factor in 47 responses, with students describing how their low energy or interest influenced their decisions. For instance, one respondent admitted, “...too lazy… I did not want to give any additional effort to the assignment.” This lack of motivation was often tied to specific periods, such as the end of a semester or program “...it was my senior year of high school….” Relatedly, some students reported rejecting feedback due to a lack of interest in the course or grade, exemplified by the statement, “It was a required course that I had to take and forget about; I didn't care about it.”

Lastly 19 responses discussed feedback rejection due to its incongruence with students' expectations. Respondents noted situations where they believed they had adhered to guidelines but received lower grades than anticipated. One student expressed their frustration, saying, “Even though you follow the guidelines, they still give you a lower grade than what you expected.”

Students' reasons for rejecting peer feedback in an academic setting

Participants were asked about their reasons for rejecting peer feedback (RQ2), and their answers were coded following the same elements described in the Lipnevich and Smith (2022) model. When responding to their reasons for rejecting feedback from their peers, only three themes were identified: Source, Message, and Recipient. Neither inductive nor deductive coding led us to create codes for Context. It may be that because peers do not have control over the learning environment, there was no reason to assign responsibility in terms of context.

Participants indicated the source as the main reason for their decision to reject peer feedback, with 131 coded responses. Two primary reasons were identified: lack of trust in peer, with 70 coded responses and lack of peer expertise, including 61 statements. Students reported not believing that their peers were acting with good intentions, which was partially due to the fact that because peer feedback was required by the instructor and not offered freely by the peer – “...they gave feedback just because they had to/were forced to give feedback….” and the requirement led to comments that were overly critical comments– “...peers are just looking to find something to critique in order to complete the assignment.” The second code was assigned when they believed the peer did not have adequate knowledge or experience to provide feedback. Students see their peers as lacking expertise because they are “younger” or “less intelligent.” For instance, one participant wrote: “I tend not to take it because peers don't have teacher-level expertise.”

Recipient

The recipient also appeared as a major reason for peer feedback rejection, with 120 linked to this theme. Within this theme, the majority of codes referred to the lack of value/utility (59) and confidence with performance (49). For the first code, respondents stated their rejection due to feeling they “got nothing out of it,” whereas for the second code, participants affirmed that “if I'm confident in my work and I don't feel as though this person's contributions would help my work then I wouldn't want to use it.”

The last code within the Recipient Processing theme was negative affect, with 12 instances. Respondents explained that they feel anxious or attacked when receiving peer feedback. Their negative emotions would arise in response to the feedback, prompting their choice to reject it. The following coded paragraph provides a clear insight into this situation:

“This is not for any reason regarding a lack of trust or credentials, but more so from equating my peers to myself, and feeling that I should either already know how to do what I'm being given feedback on, or that my work is so poor, that even those in similar positions to myself have critiques.”

Message

The content of peer feedback was also indicated as a possible reason for rejection, with 36 responses coded in this theme and 2 identified codes: ambiguous/unclear and negative feedback tone. For the first code, which appeared in 21 responses, students' statements repeatedly mentioned peer feedback as being unclear, vague, not specific, very broad, not making sense, incoherent, and lacking explanation. In one response, the student stated several months had passed since receiving the feedback and, “I still don't know what he meant….” The second code, which included 15 instances, included messages that were perceived as having a negative tone, that were disrespectful, biased, polarized, or judgemental. One participant stated that the message was “...in a tone of disrespect and passive aggressiveness….”

Quantitative results

Reasons college students have for rejecting teacher and peer feedback

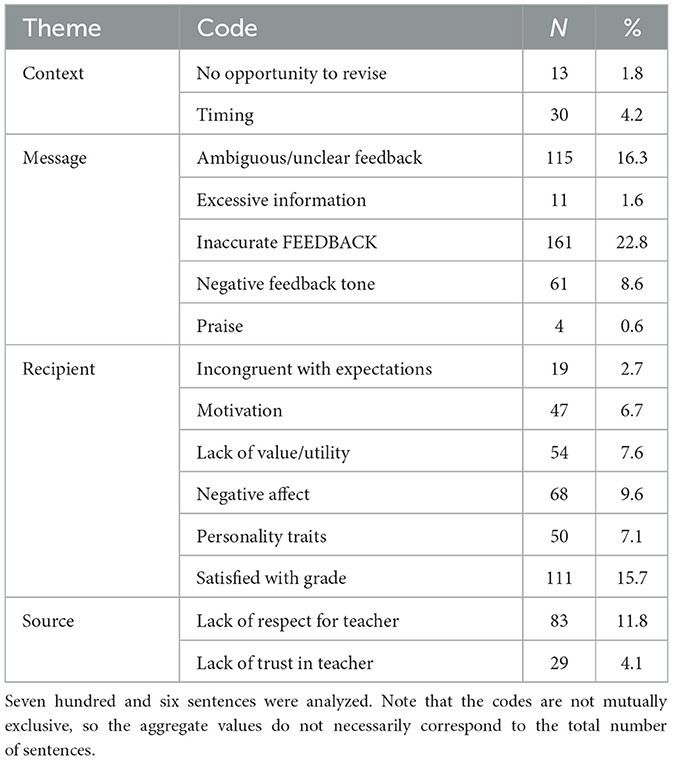

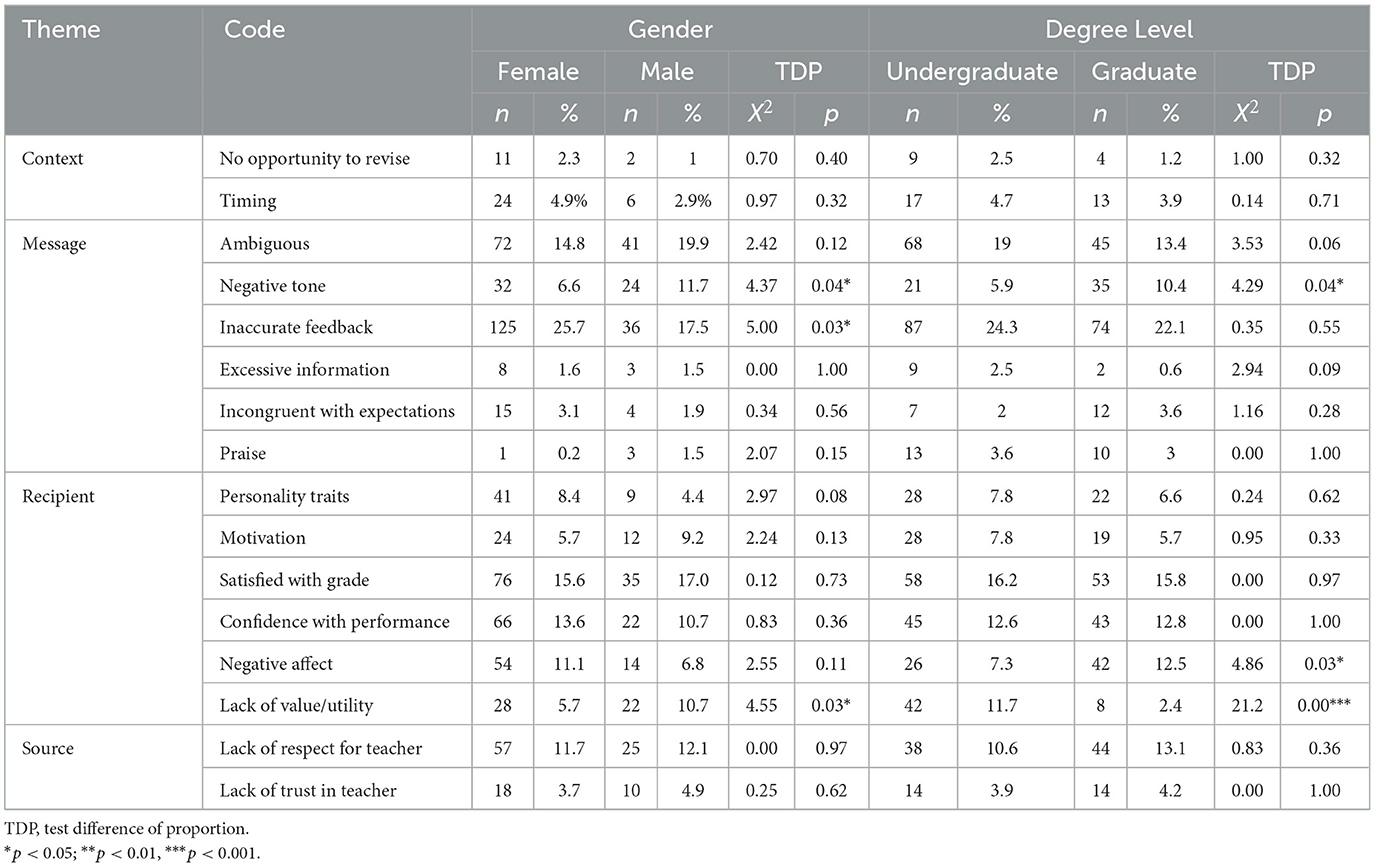

We first calculated the overall descriptive statistics for each reason (code) to reject teacher and peer feedback to draw a general picture of the comments provided and widely explained in previous sections. Regarding teacher feedback (Table 4), the most frequent reason to reject teacher feedback was related to the characteristics of the message (N = 352, 49.9% of all codes). Among these, inaccurate feedback (N = 161) and ambiguous or unclear feedback (N = 115) were the most commonly reported issues, representing 22.8 and 16.3% of the total codes, respectively, followed by negative feedback tone, which accounts for 8.6% (N = 61). Other concerns, such as message incongruent with expectation (2.7%), excessive information (1.6%) and praise (0.6%), were less prevalent. For the recipient theme (49.4.% of the total), satisfaction with grades (N = 111, 15.7%), and negative affect (N = 68, 69.6%) were the most frequent issues, suggesting that students' responses to feedback often center around their perceived performance and its effect on their overall satisfaction and mood.

The source theme, which includes how recipients perceive the person providing the feedback, accounts for 15.9% (N = 112) of the overall codes. The most prominent issue within this category is the lack of respect for the teacher, which represents 11.8% (N = 83) of the total responses. Finally, context themes only account for 6% of the overall codes.

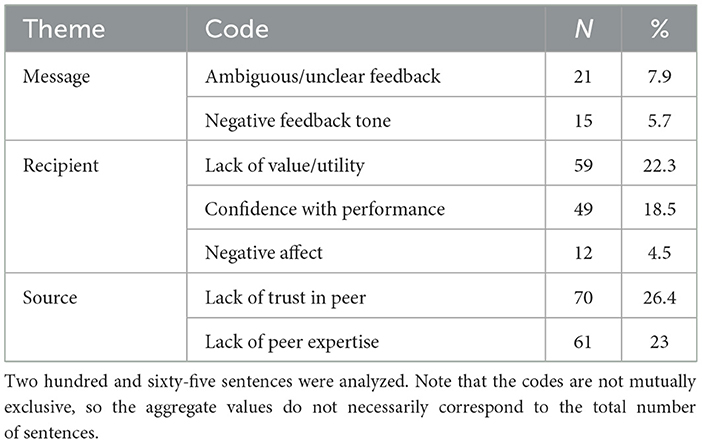

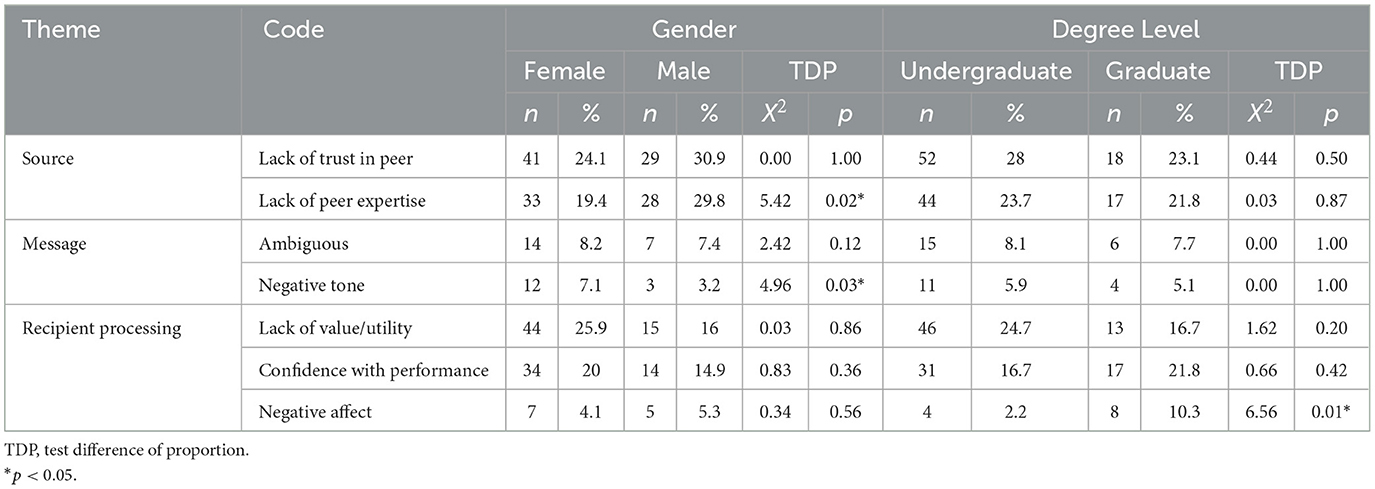

Table 5 presents the distribution of reasons to reject peer feedback by theme (message, recipient processing, and source). The most frequent theme identified to reject peer feedback was related to the characteristics of the source, which accounted for 49.4% (N = 131) of the total responses. Within this theme, lack of trust in peers emerged as the predominant code, representing 26.4% of all responses (N = 70). Similarly, lack of peer expertise accounted for 23% of the responses (N = 61), indicating that students often viewed their peers as insufficiently knowledgeable or qualified to provide valuable feedback. The second most prominent theme was recipient processing aspects, representing 45.3% of the total codes (N = 120). The most frequently cited reason to reject peer feedback within this theme was lack of value/utility of message (22.3%, N = 59), followed by confidence with performance (18.5%, N = 18.5), which indicates that students who were confident in their own work were less likely to regard peer feedback as beneficial. Finally, characteristics of the message accounted for 13.6% of the responses (N = 36), with ambiguous or unclear feedback identified in 7.9% (N = 21) of sentences and negative feedback tone in 5.7% (N = 15). Further explanation on the coding process and examples of students' responses for each code are presented in our qualitative findings.

Characteristics of responses regarding teacher and peer feedback rejection

The proportion of reasons to reject feedback as a function of respondent's gender and academic level and Z-tests to compare observed proportions were then estimated. Regarding teacher feedback (Table 6), female participants were less likely to state negative feedback tone (p = 0.04) and lack of value/utility (p = 0.03) as reasons for rejecting teacher feedback than males. Conversely, they were more likely to have inaccurate feedback as a reason to reject feedback than males (p = 0.03).

Education level also showed several significant differences. Undergraduate students more often claimed lack of value as a reason for rejecting teacher feedback than graduate students (p < 0.001). On the other hand, graduate students more often cited negative feedback tone (p = 0.04) and negative affect (p = 0.03) as reasons to reject teacher feedback.

Regarding peer feedback (Table 7), female students were less likely to claim a lack of peer expertise (p = 0.02) than their male counterparts. Conversely, male participants were less likely to say that negative tone was their reason for rejection (p = 0.03) than females. The only difference in academic level was related to negative affect, with undergraduates being less likely to cite this as a reason (p = 0.01) compared to graduate students.

Forecasting reasons to reject teacher and peer feedback: the effect of gender, race, educational level, and GPA

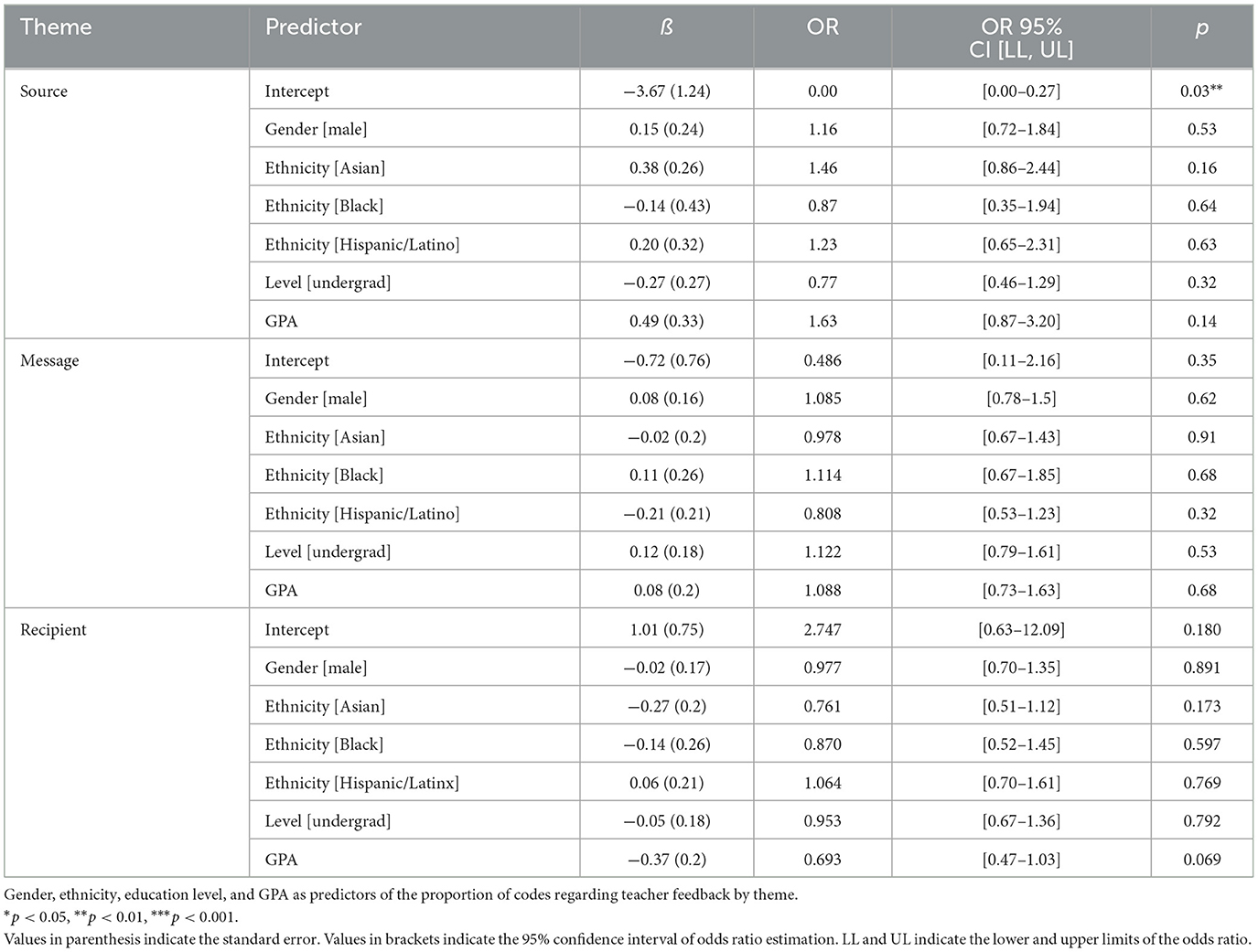

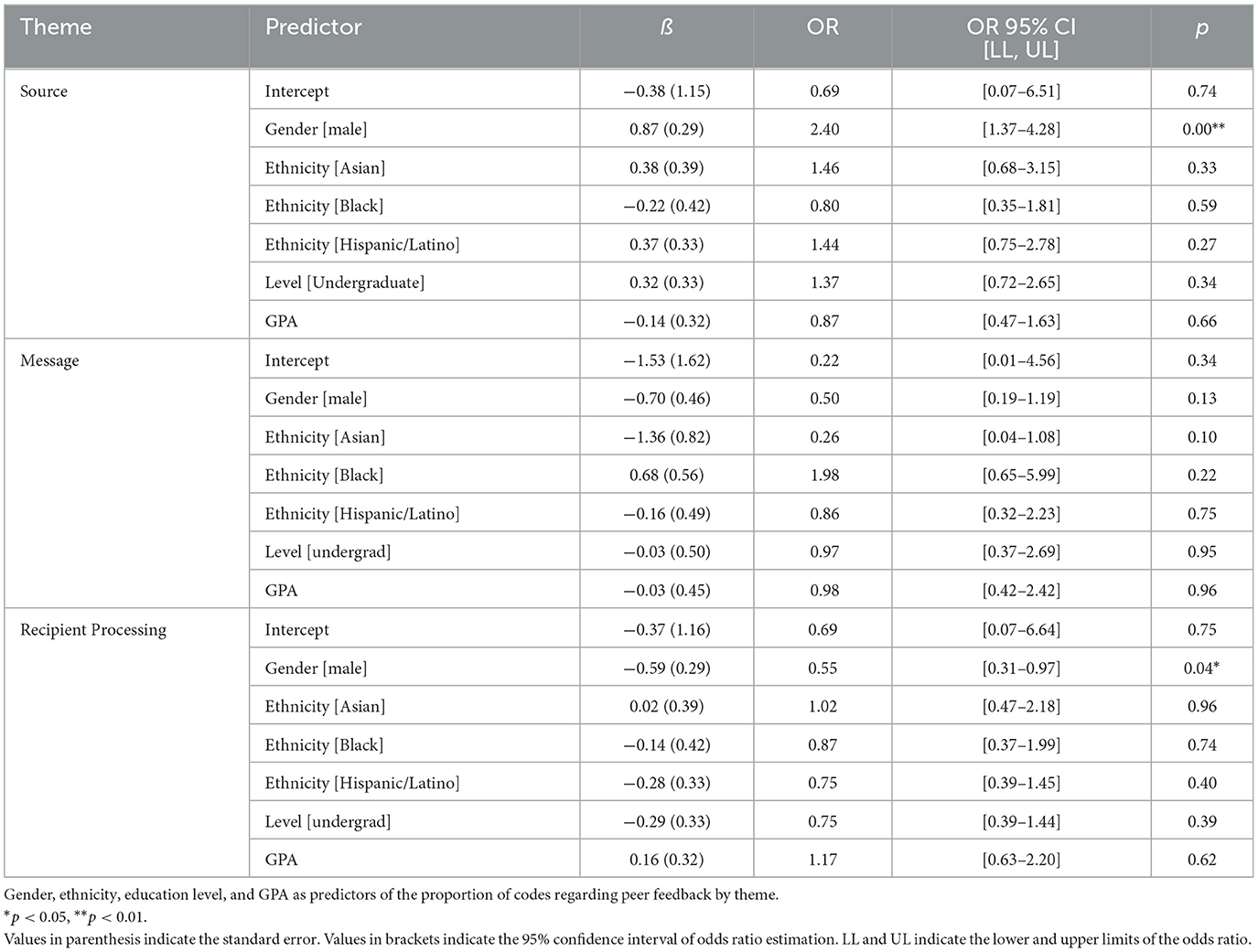

Multiple logistic regression models were conducted to examine the extent to which gender, race, educational level, and GPA predict the type of claims for rejecting teacher and peer feedback among students. Separate models were estimated for the total sample of participants who independently provided rejection claims for teacher and peer feedback. The dependent variable was the proportion of codes assigned to reject feedback by participants for each theme. Supplementary Table S3 displays the goodness-of-fit test statistics for all models conducted. Comparison of goodness-of-fit statistics for models conducted with categories with zero-inflated indicates that the best model for adjusted data were logistic regression models with a binomial link function (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). Plot analyses were also generated to check linear model assumptions (Supplementary Figures S1–S6), showing an overall acceptable adjustment of normality, outliers, and heteroscedasticity criteria.

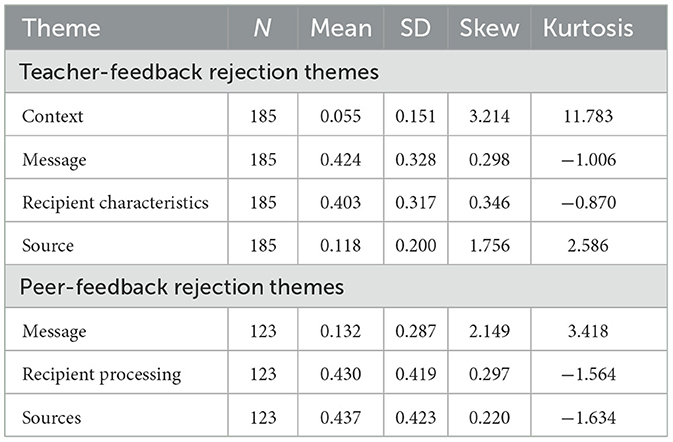

Table 8 presents descriptive information for the dependent variable for the total sample's teacher and peer feedback themes. With respect to teacher feedback, on average, 42.2% of the participants provided reasons to reject feedback related to the message characteristics, such as ambiguous/unclear feedback, excessive information, and inaccurate feedback. In comparison, 40.3% of participants provided reasons related to the recipients, such as motivation, satisfaction with grade and personality. Only 5.5% of participants claimed that a reason for rejecting feedback related to context, such as lack of opportunities to revise feedback and timing. This category was excluded from the subsequent analysis because the proportion of responses was very low (around 5%), and the overall model fit (F-test and p-value) was not statistically significant. With respect to peer feedback, on average, 43.7 and 43% of participants provided reasons to reject this kind of feedback due to aspects relating to the recipient processing (lack of value/utility, confidence in Performance, and negative affect) and the source (lack of trust and peer-expertise).

According to the results (Table 9) individual variables such as gender, ethnicity, level of education, and GPA did not predict the type of claims for rejecting teachers in our sample.

Regarding peer feedback rejection (Table 10), results indicate that male students were 2.40 (ß = 0.87, p < 0.01) times more likely to reject peer feedback due to aspects regarding sources aspects than females. Conversely, male participants were 0.55 times less likely (ß = −0.59, p = 0.04) to reject feedback for recipient-related aspects than female participants.

Discussion

This mixed methods study explored students' reasons for rejecting feedback from their instructors and peers. Through data obtained from open-ended questions, students' responses were coded in themes following the student-feedback interaction model (Lipnevich and Smith, 2022).

In relation to students' reasons for rejecting teacher feedback, a major finding stands out from the coded data. Among the 706 phrases coded, the “Message” theme accounted for the largest proportion of coded phrases (352), followed closely by “Recipient” (341). These results emphasize that both the content of the feedback and the characteristics of the student are crucial factors in feedback acceptance. These findings are important, as factors within the student (e.g., motivation, expectations, or personality traits) are often beyond instructors' direct control. However, the content and delivery of feedback (“Message”) are entirely within the instructor's command.

Diving deeper into the theme “Message,” which was unsurprisingly our largest theme, students expressed frustration with feedback that was unclear, ambiguous, excessive, rude, or focused on praise. These findings align with existing research (Winstone et al., 2017; Máñez et al., 2024), which emphasizes that clarity and tone are crucial for effective feedback. Feedback perceived as ambiguous or overly critical may fail to convey actionable steps for improvement, leaving students feeling unsupported. Interestingly, several participants in our sample reported rejecting feedback that was too extensive. While previous research suggests that students prefer detailed feedback (Blair et al., 2013; Lipnevich and Smith, 2009a,b), this finding highlights the fine balance between providing enough detail and overwhelming students. Many participants also reported rejecting feedback they perceived as inaccurate or misaligned with their work. Disagreement with the feedback by questioning its accuracy emerged as the primary reason for rejection, aligning with Fithriani (2018) findings, which highlight that L2 students often reject feedback when it conflicts with their own beliefs. This emphasizes an important point: students do not passively accept teacher feedback as inherently valid and correct. Instead, they actively evaluate the feedback, and when it does not align with their individual perceptions, they may reject it.

Within the “Recipient” theme, satisfaction with one's own performance emerged as a significant factor influencing feedback rejection. Many students reported rejecting feedback because they believed their work had already met expectations. This finding supports the negative impact of grades on student motivation (Koenka et al., 2019). When students feel their performance is “good enough,” they may be less inclined to engage with feedback, which is problematic as students' beliefs about performance sufficiency may conflict with instructors' standards. This finding stresses the importance of fostering a growth mindset and helping students see feedback as an opportunity for learning rather than a critique of their performance. Unexpectedly, many codes were related to participants' personality traits. Participants frequently described characteristics such as pride, skepticism, or nervousness as influencing their rejection of feedback. While personality traits are beyond the instructor's direct control, other aspects within the “Recipient” theme can be addressed. For instance, instructors can enhance the perceived value of feedback by explicitly connecting it to the task's objectives or providing clear rubrics to help students adjust their expectations. Still, within the theme of recipient processing, students reported having rejected feedback when feedback evoked negative emotions. The link between feedback and emotions is well-established in the literature (Fong and Schallert, 2023; Pekrun et al., 2014). For instance, Ryan and Henderson (2018) found that the lack of congruence between students' expectations and teacher feedback led to higher rates of experiences of negative emotions. Interestingly, reasons associated with the source of the feedback, such as lack of trust in the instructor's competence or respect for their perspective, were less prevalent but still noteworthy. As in previous research, the strength of the student-teacher relationship and students' beliefs in their teacher's credibility influence how the recipients interact with feedback (Amerstorfer and Freiin von Münster-Kistner, 2021; Hyland, 2013; Pat-El et al., 2012; Tuck, 2012). This finding further emphasizes the importance of building stronger student-teacher relationships and demonstrating expertise, as the student could reject even the most detailed and individualized feedback if their perception of the instructor were negative.

Finally, the context in which feedback was delivered accounted for the fewest codes. Rather than interpreting this result as minimizing the importance of context, we argue that structural and institutional factors, though present, are less evident to students. The lack of opportunity to apply feedback appeared as a recurring justification for rejection. Students often fail to recognize that even if they cannot implement feedback in the same assignment, it could still assist their learning and improve performance in future tasks. Therefore, providing students with opportunities to use feedback to revise their work is essential (Jonsson, 2013; Nicol et al., 2014). Additionally, the timing of feedback delivery matters greatly. Students value feedback that is delivered neither too early nor too late. While these issues are categorized under context, they fall within the instructor's command. When instructors are mindful of feedback timing and insert opportunities for revision in their practices, they can significantly enhance the effectiveness of feedback by increasing students' willingness to engage with it.

Our second research question focused on students' reasons behind their rejection of peer feedback. Neither inductive nor deductive coding led us to create codes for “Context”. It may be that because peers do not control the learning environment, there was no reason to assign responsibility in context.

In contrast to instructor feedback, the source emerged as a predominant theme in peer feedback rejection. Students frequently cited distrust in peers' intentions or expertise, perceiving peer feedback as less credible or valuable. These findings are consistent with previous research (e.g., Lam and Habil, 2020) that suggests students often mistrust their peer's ability to provide feedback or may perceive that their peers do not have sufficient expertise (Panadero, 2016). However, research consistently highlights the effectiveness of peer feedback in enhancing learning outcomes (Huisman et al., 2018; Simonsmeier et al., 2020). Thus, instructors should actively discuss the value of peer assessment in their classrooms and create opportunities for students to engage in meaningful feedback exchanges by encouraging students to regularly seek and provide constructive feedback.

Regarding the characteristics of the “Recipient,” students focused primarily on their confidence in their performance and the perceived lack of value in the feedback provided by their peers. Participants frequently noted that peer review activities were often structured as class requirements rather than autonomous exchanges, which influenced their perception of the feedback's real utility. The compulsory nature of providing feedback led some to doubt its sincerity or effectiveness in enhancing their work. This lack of autonomy diminished the perceived value of the feedback, as students felt it was given out of obligation rather than genuine intent to help. Interestingly, participants did not elaborate on individual characteristics in this context as much as they did in responses about instructor feedback. One possible explanation is that students had already described their personality and learning preferences when responding to the instructor feedback question, which immediately preceded the peer feedback question. Another potential reason is the more personal nature of peer interactions. Students may view their relationship with peers as one of shared responsibility, leading them to avoid assigning blame or acknowledging their own role in feedback rejection.

Similarly to the instructor feedback, issues with the message also contributed to peer feedback rejection. Ambiguity and negative tone were key factors, with students perceiving peer feedback as vague, broad, or judgmental. These findings suggest that students may benefit from training on how to provide specific, actionable, and respectful feedback.

Differences in reasons for feedback rejection related to student variables

In addition to exploring common themes in students reasons to reject teacher and peer feedback, we also investigated whether students' responses varied as a function of students characteristics (gender and educational level). The findings revealed interesting gender and academic level differences in students' reasons for rejecting teacher and peer feedback. For teacher feedback, female participants were less likely than male students to cite negative feedback tone and lack of value/utility as reasons for rejection, suggesting they may have a greater tolerance for tone or utility-related concerns. However, females were more likely to reject teacher feedback due to inaccuracies, indicating a potential heightened critical view of feedback quality.

In regards to peer feedback, gender differences were also found; females were less likely to attribute rejection to a lack of peer expertise, possibly reflecting greater trust in their peers' abilities. Interestingly, contrary to the teacher findings, female students were more likely than males to cite negative tone as a reason for rejecting peer feedback, emphasizing the importance of respectful and supportive communication in peer interactions. Previous literature also identified differences in male perception of peers: females valued peer assessment more than males (Rotsaert et al., 2017). Gender differences in the feedback experience overall have been evident since at least the nineties (Vattøy et al., 2021), and came up in other themes to be discussed in upcoming subheadings. These differences highlight the importance of considering diverse student characteristics when tailoring and delivering feedback. For instance, ensuring feedback accuracy and specificity may be particularly important for fostering acceptance among female students.

As for educational level, significant differences in reasons for rejecting feedback were also noted. For teacher feedback, undergraduate students were more likely than graduate students to cite a lack of value/utility as their reason for rejection, reflecting potential challenges in understanding the relevance or applicability of feedback at earlier stages of academic development (Lipnevich and Lopera-Oquendo, 2022). In contrast, graduate students more frequently cited negative feedback tone and negative affect as reasons for rejection, suggesting heightened expectations for professionalism and emotional support in feedback as they progress in their academic careers. Similarly, in peer feedback, graduate students were more likely than undergraduates to cite negative affect as a reason for rejection, which suggests greater emotional investment that graduate students may place in feedback interactions (Agius and Wilkinson, 2014).

The predictive analyses provided additional insights into the factors influencing feedback rejection. While we did not find any significance related to the rejection of teacher feedback, gender appeared as a significant predictor for rejecting peer feedback, with males being more likely to cite source-related reasons, such as a lack of trust or expertise in their peers, whereas females were more likely to reject feedback due to recipient-related factors, such as confidence in their own performance or perceived value of the feedback. These findings suggest that male students may focus more on external attributes of the feedback provider, while females may prioritize their internal perceptions of feedback relevance.

Limitations and future directions

While this study was exploratory, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our sample consisted solely of post-secondary students from various colleges within a large public university in the northeastern United States, limiting the generalizability of our findings to broader student populations. Future research should examine feedback rejection across diverse educational contexts, including secondary schools and international institutions, to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Second, the prompts required participants to recall past events, which may not have captured the full range of their feedback rejection experiences. Future studies could incorporate real-time data collection methods, such as experience sampling or diary studies, to reduce reliance on retrospective self-reporting.

Third, the prompts were broad and open-ended, allowing participants to interpret the term “feedback” in their own way. While this approach provided valuable insights, it also introduced variability in responses. Future research could refine prompts to ensure greater consistency while still allowing for individual perspectives.

Finally, the reliance on written language production may have posed challenges for non-native speakers or individuals with language-based differences. Future studies should explore alternative data collection methods, such as interviews or multimodal responses, to accommodate a wider range of participants and ensure inclusivity in feedback research.

Implications

Based on the findings of this exploratory study, we propose several next steps for enhancing feedback practices and advancing teacher professional development.

• Context: Institutions should provide teachers with ample time to provide feedback so students have the time to implement it. Providing guided opportunities for peers can enhance their feedback-giving skills, making them a more valued source;

• Source: The student-teacher relationship is an important aspect of feedback, and teachers should work on establishing a positive rapport with their students while demonstrating their content and pedagogical expertise. Since peers are seen as untrustworthy or lacking expertise, some steps may help alleviate these problems: assigning peers to provide feedback could be an ungraded task so that they do not feel compelled to be unnecessarily critical, and they can be given rubrics to use as guides for feedback;

• Message: The feedback message is often rejected due to being ambiguous and having a negative tone. With this in mind, it needs to precisely respond to student work, be actionable, and provide a genuine tone of support. This applies to both teacher and peer feedback;

• Recipient: Knowing how to recognize and adapt to students' different personalities and motivations will allow teachers to tailor feedback appropriately. This would require institutional practices and professional development that enhance and support interpersonal communication skills;

Conclusion

In conclusion, the dynamics of feedback rejection differ significantly based on the source of the feedback. Teacher feedback is primarily rejected due to issues related to the message or the student, whether it is clarity, relevance, or the student's emotional and cognitive responses. In contrast, peer feedback is overwhelmingly about the source, with students questioning the credibility, expertise, or value of their peers' input. This distinction underscores each feedback context's unique challenges and the need for tailored strategies to address rejection effectively.

Equally compelling are the gender and academic level differences, which remain underexplored in the broader discussion. Gendered patterns in emotional and cognitive responses to feedback suggest that male and female students may perceive and act on feedback differently, influencing rejection rates and engagement. Academic levels further complicate the picture, as younger or less experienced students may struggle more with decoding and accepting feedback compared to their senior counterparts. Addressing feedback rejection requires a nuanced understanding of these intersecting factors (i.e., source, message, gender, and academic level), paving the way for more targeted, equitable, and effective feedback practices.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by QC-23452023 Protocol of QC and GC, CUNY. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL-O: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. LT: Methodology, Writing – original draft. JG: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CF: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1567704/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Sentence was defined as a complete phrase, which ranges from several words to an entire paragraph, which begin with a capital letter and end with a period [.] as terminal punctuation.

References

Agius, N., and Wilkinson, A. (2014). Students' and teachers' views of written feedback at undergraduate level: a literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 34, 552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.005

Ajjawi, R., and Boud, D. (2017). Researching feedback dialogue: an interactional analysis approach. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 252–265. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863

Amerstorfer, C. M., and Freiin von Münster-Kistner, C. (2021). Student perceptions of academic engagement and student-teacher relationships in problem-based learning. Front. Psychol. 12:713057. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713057

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH (2023). ATLAS.ti Mac (version 23.3.0) [Qualitative Data Analysis Software]. Available online at: https://atlasti.com

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Blair, A., Curtis, S., Goodwin, M., and Shields, S. (2013). What feedback do students want? Politics 33, 66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01446.x

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educ. Meas. 30, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2010.00195.x

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 24, 205–249. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

Coombes, D. (2021). What is effective feedback? A comparison of views of students and academics. J. Educ. Pract. 12:25. doi: 10.33422/3rd.icnaeducation.2021.07.25

Cutumisu, M., Blair, K. P., Chin, D. B., and Schwartz, D. L. (2017). Assessing whether students seek constructive criticism: the design of an automated feedback system for a graphic design task. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 27, 419–447. doi: 10.1007/s40593-016-0137-5

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., et al. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 25–36. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Dijks, M. A., Brummer, L., and Kostons, D. (2018). The anonymous reviewer: the relationship between perceived expertise and the perceptions of peer feedback in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 1258–1271. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1447645

Double, K. S., McGrane, J. A., and Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2020). The impact of peer assessment on academic performance: a meta-analysis of control group studies. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 32, 481–509. doi: 10.1007/s10648-019-09510-3

Drew, S. (2001). Perceptions of what helps learn and develop in education. Teach. High. Educ. 6, 309–331. doi: 10.1080/13562510120061197

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 70–120. doi: 10.3102/0034654312474350

Ferguson, P. (2011). Student perceptions of quality feedback in teacher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 51–62. doi: 10.1080/02602930903197883

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. Tesol Q. 31:315. doi: 10.2307/3588049

Fithriani, R. (2018). Cultural influences on students' perceptions of written feedback in L2 writing. J. For. Lang. Teach. Learn. 3:3124. doi: 10.18196/ftl.3124

Fong, C. J., and Schallert, D. L. (2023). “Feedback to the future”: advancing motivational and emotional perspectives in feedback research. Educ. Psychol. 58, 146–161. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2134135

Fong, C. J., Schallert, D. L., Williams, K. M., Williamson, Z. H., Warner, J. R., Lin, S., et al. (2018). When feedback signals failure but offers hope for improvement: a process model of constructive criticism. Think. Skills Creat. 30, 42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.014

Friendly, M., and Meyer, D. (2015). Discrete Data Analysis with R: Visualization and Modeling Techniques for Categorical and Count Data, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. doi: 10.1201/b19022

Fyfe, E. R., de Leeuw, J. R., Carvalho, P. F., Goldstone, R. L., Sherman, J., Admiraal, D., et al. (2021). ManyClasses 1: assessing the generalizable effect of immediate feedback versus delayed feedback across many college classes. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 4:27575. doi: 10.1177/25152459211027575

Gibbs, G., and Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which assessment supports students' learning. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 1, 3–31.

Goetz, T., Lipnevich, A. A., Krannich, M., and Gogol, K. (2018). “Performance feedback and emotions,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback, eds. A. A. Lipnevich, and J. K. Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 554–574.

Graham, S., Hebert, M., and Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: a meta-analysis. Elem. Sch. J. 115, 523–547. doi: 10.1086/681947

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Heitink, M. C., Van der Kleij, F. M., Veldkamp, B. P., Schildkamp, K., and Kippers, W. B. (2016). A systematic review of prerequisites for implementing assessment for learning in classroom practice. Educ. Res. Rev. 17, 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.002

Henderson, M., Ryan, T., and Phillips, M. (2019). The challenges of feedback in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 1237–1252. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1599815

Hernandez, R., Bassett, S. M., Boughton, S. W., Schuette, S. A., Shiu, E. W., and Moskowitz, J. T. (2018). Psychological well-being and physical health: associations, mechanisms, and future directions. Emot. Rev. 10, 18–29. doi: 10.1177/1754073917697824

Higgins, R., Hartley, P., and Skelton, A. (2001). Getting the message across: the problem of communicating assessment feedback. Teach. High. Educ. 6, 269–274. doi: 10.1080/13562510120045230

Hughes, J. (2021). Krippendorffsalpha: an R package for measuring agreement using Krippendorff's alpha coefficient. R J. (2021) 13, 413–425.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van den Broek, P., and van Driel, J. (2018). The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students' academic writing: a meta-analysis. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 863–880. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1545896

Hyland, K. (2013). Faculty feedback: perceptions and practices in l2 disciplinary writing. J. Second Lang. Writing 22, 240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2013.03.003

Jonsson, A. (2013). Facilitating productive use of feedback in higher education. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 14, 63–76. doi: 10.1177/1469787412467125

Koenka, A. C., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Moshontz, H., Atkinson, K. M., Sanchez, C. E., and Cooper, H. (2019). A meta-analysis on the impact of grades and comments on academic motivation and achievement: a case for written feedback. Educ. Psychol. 41, 922–947. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2019.1659939

Lam, C. N., and Habil, H. (2020). Peer feedback in technology-supported learning environment: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 10:7866. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i9/7866

Lam, R. (2017). Enacting feedback utilization from a task-specific perspective. Curric. J. 28, 266–282. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2016.1187185

Li, J., and De Luca, R. (2012). Review of assessment feedback. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 378–393. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.709494

Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D. A., and Smith, J. K. (2016). “Toward a model of student response to feedback,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds. G. Brown, and L. R. Harries (New York, NY: Routledge), 169–185.

Lipnevich, A. A., Eßer, F. J., Park, M. J., and Winstone, N. (2023). Anchored in praise? Potential manifestation of the anchoring bias in feedback reception. Assess. Educ. 30, 4–17. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2023.2179956

Lipnevich, A. A., and Lopera-Oquendo, C. (2022). Receptivity to instructional feedback: a validation study in the secondary school context in Singapore. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 40, 22–32. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000733

Lipnevich, A. A., and Panadero, E. (2021). A review of feedback models and theories: descriptions, definitions, and conclusions. Front. Educ. 6:720195. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.720195