- Department of Education Policy and Leadership, Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Introduction: This study aimed to explore the PhD student-supervisor relationship and its impacts on students and supervisors from a qualitative perspective.

Methods: A total of 50 PhD students and 11 supervisors from Hong Kong were approached using focus groups and individual interviews. Based on the interpersonal relationship model, this study conducted interviews with students to examine their perceptions of eight styles of relationships and their impact on students.

Results: The results highlighted that the PhD student-supervisor relationship affected student academic achievement, well-being, and career and social network development. The interviews with the supervisors showed the impact on supervisors related to well-being, reflection on coaching style, and selection for future students.

Discussion: Findings provide theoretical insights and conceptual and practical implications for understanding the eight styles of PhD student-supervisor relationships. This study also offers recommendations on university policies aiming to enhance the PhD student-supervisor relationship in order to boost positive impacts and hinder negative impacts.

1 Introduction

The PhD student-supervisor relationship has drawn increasing attention (Kusurkar et al., 2022) as doctoral enrolments have expanded rapidly worldwide (e.g., Gruzdev et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2022; University Grants Committee, 2022). Research has found that the relationship between doctoral students and their supervisors is one of the most influential factors for their graduate school experiences (Sverdlik et al., 2018). More specifically, supportive supervision has been identified in the literature as the most important contributor to doctoral experience and students’ well-being (e.g., Byrom et al., 2022; Cowling, 2017). Despite its crucial significance, the status of the PhD student-supervisor relationship does not seem well investigated. Moreover, negative stereotypes have been reported in the limited evidence. For instance, over 19% of students ranked their relationship with supervisors among the top three most stressful aspects of their graduate school in Canada (Park et al., 2021). Likewise, Cardilini et al. (2022) found that 20% of candidates reported not being satisfied with their supervision in Australia.

Furthermore, despite the critical role of the PhD student-supervisor relationship, the existing literature has only focused on its impacts on students and from students, but left out the impacts on supervisors and supervisors’ voices. For example, most studies have examined PhD students’ perspectives on how student-supervisor relationships affect well-being (e.g., Dhirasasna et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2022), study progress (e.g., Gill and Burnard, 2008; Gunnarsson et al., 2013), and performance (e.g., Cardilini et al., 2022; Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019). The existing literature has largely overlooked its impacts relevant to the supervisor, a key stakeholder of the student-supervisor relationship. However, along with an increase in the number of doctoral enrolments, there has been a corresponding increase in research supervisors, who face increasing complexities and research diversities with their PhD students (Gatfield, 2005; Gruzdev et al., 2020).

Indeed, existing studies of the PhD student-supervisor relationship have key limitations. First, most studies related to the PhD student-supervisor relationship have been conducted in Western societies, and there is little research in Asia, particularly in the Hong Kong context. Second, as mentioned above, existing studies have mainly focused on interpersonal relationships from the student perspective (e.g., Gruzdev et al., 2020). Third, the majority of studies focused on the impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationships on students (e.g., Cardilini et al., 2022; Dhirasasna et al., 2021), but not on supervisors. However, in terms of the interactive and interpersonal nature of the student-supervisor relationship (Mainhard et al., 2009), excessive focus on or neglect of either party can lead to an imbalance in the relationship. Therefore, it is essential to explore and understand the relationship from a bidirectional perspective. Fourth, the downstream consequences of the relationship are not well understood. To address these gaps, this study aimed to examine the PhD student-supervisor relationship and its consequences on students and supervisors guided by the model of PhD student-supervisor relationship (Mainhard et al., 2009) using a sample of both PhD students and supervisors from Hong Kong.

2 Theoretical framework and literature review

2.1 Theoretical framework: the model for PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior

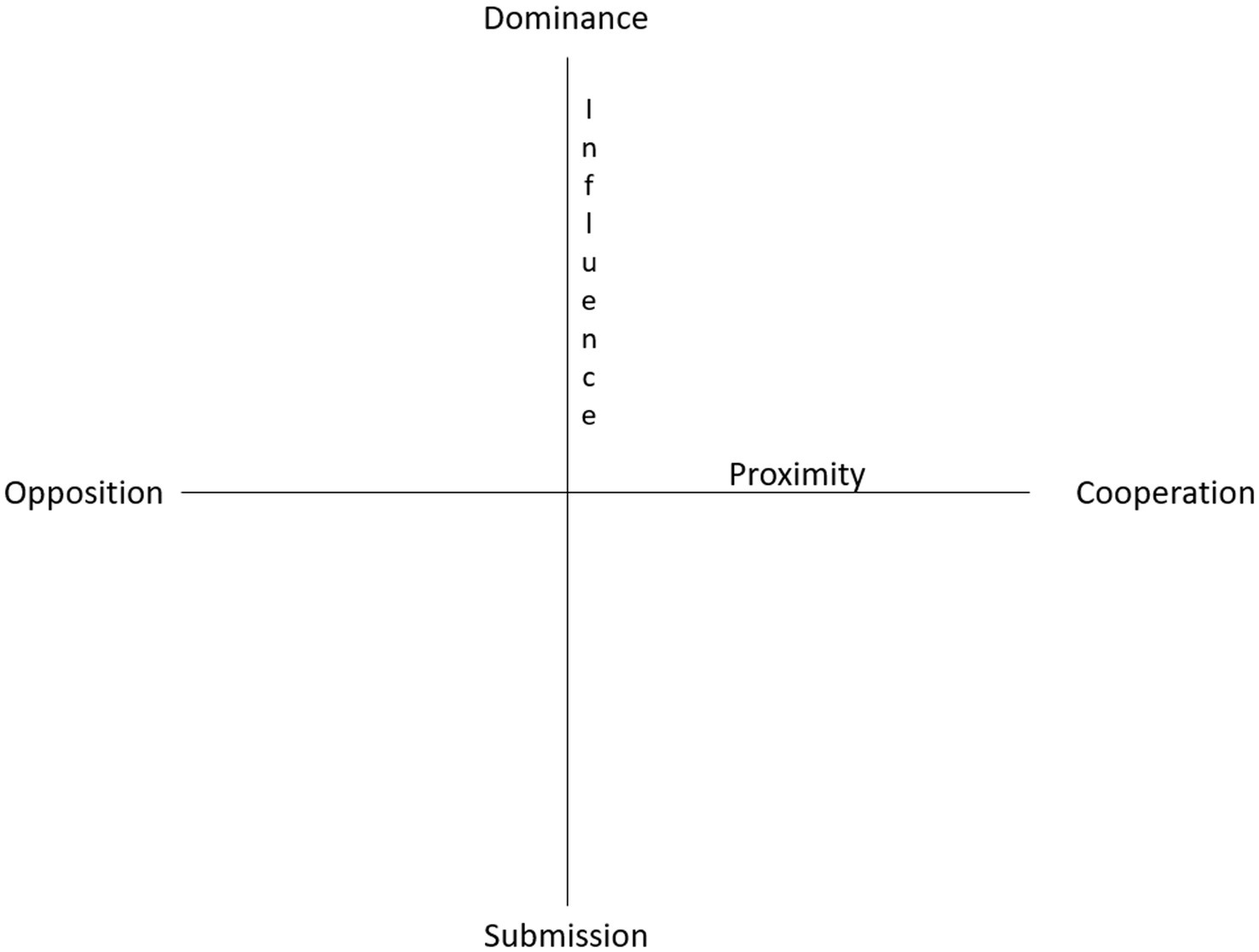

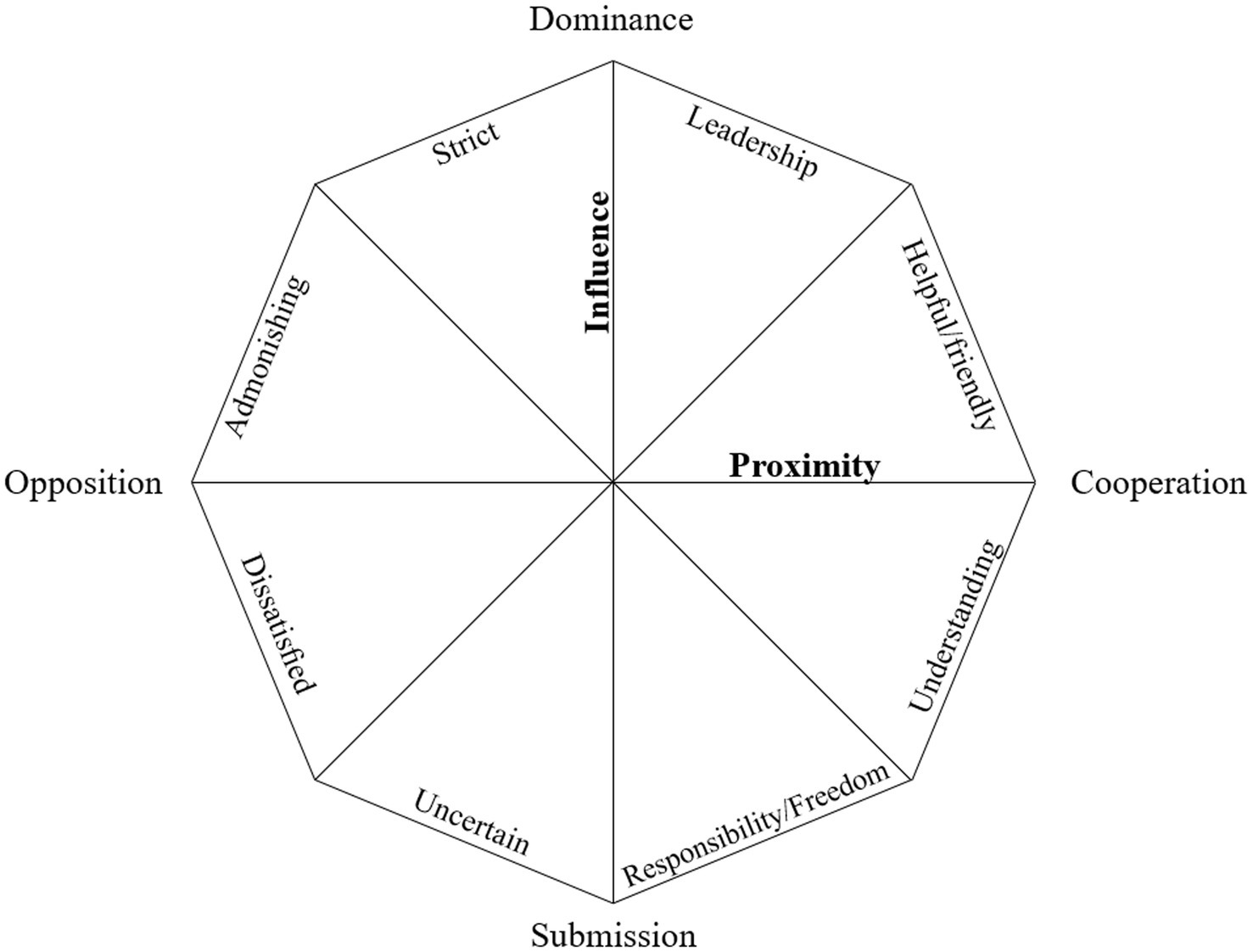

The model of interpersonal supervisor behavior was utilized as the theoretical framework to investigate the PhD student-supervisor relationship in this study (Mainhard et al., 2009). Leary (1957) originally constructed such a model, which described and measured specific human interpersonal behaviors. This model captured both normal and abnormal behavior on the same scale, and the relationship aspect of behavior is described using a two-dimensional matrix (see Figure 1). Derived from this model, Wubbels et al. (1993) framed an analysis of the interpersonal aspect of teacher behavior and labeled two dimensions, namely Proximity (Opposition-Cooperation) and Influence (Dominance-Submission). Based on adapting the Leary model (Wubbels et al., 1993), Mainhard et al. (2009) developed a relationship model that describes specific interpersonal behaviors between PhD students and supervisors. This two-dimensional model for the supervisor-doctoral student relationship, represented as two axes, proposes eight types of relationship: leadership, helping/friendly, understanding, student freedom and responsibility, uncertain, dissatisfied, admonishing, and strict (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. The coordinate system of the Leary model (Goh, 1994, p. 33).

Figure 2. The model for PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior (Mainhard et al., 2009, p. 363).

Leary’s model and its descendant models have been widely used in clinical and psychological settings for a long time (Goh, 1994) before being transferred to education (i.e., Mainhard et al., 2009; Wubbels et al., 2006). Mainhard et al. (2009) utilized the model to explore the relationship aspect of supervisor behavior (Figure 1). In more detail, Mainhard et al. (2009) proposed eight categories of student-supervisor relationships are: Leadership (e.g., the supervisor acts confidently and give clear guidance to PhD students); Helping/friendly (e.g., the supervisor always cooperates, supports and helps PhD students); Understanding (e.g., supervisor trusts and listens to PhD students); Student Responsibility/Freedom (e.g., supervisor follows students proposals and allows them to make their own decisions); Uncertain (e.g., the supervisor acts unconvincingly and ambiguity to PhD students); Dissatisfied (e.g., supervisor disbelieves and dissatisfied about PhD students skills and progress); Admonishing (e.g., the supervisor is impatient and anger toward PhD students) and Strict (e.g., the supervisor is quick to criticize students and critical of their work). Research shows these styles are highly associated with student satisfaction (Kremer-Hayon and Wubbels, 1993), academic performance, and study progress (Cardilini et al., 2022; Jackman and Sisson, 2022). Therefore, this study utilized the model as a theoretical framework to investigate the relationship style between doctoral students and supervisors in Hong Kong, as well as its impacts on both students and supervisors.

2.2 Literature review: the PhD student-supervisor relationship

The student-supervisor relationship of doctoral students has become a research focus in the doctoral literature. Here we review studies examining student-supervisor relationships from the perspective of supervisor leadership styles (e.g., Dhirasasna et al., 2021; Gatfield, 2005; He and Zhu, 2022; Levecque et al., 2017). For instance, Gatfield (2005) established a two-dimensional (i.e., structure and support) model, namely, Laissez-faire Style, Pastoral Style, Directorial Style, and Contractual Style. In line with most scholars in personality theory development, the four descriptors used are best termed “preferred operating styles.” Moreover, Levecque et al. (2017) drew on research into organizational and workplace behavior in order to unpack the supervisory relationship. This large-scale study distinguished between “autocratic,” “inspiring,” and “laissez-faire” leadership styles of supervisors. Furthermore, He and Zhu (2022) demonstrated an alternative approach for outlining the relationships between doctoral students and supervisors. They reported four primary relationships between doctoral students and supervisors, namely doctoral students leading the dance (Ling Wu), co-dancing (Gong Wu), supervisor supporting the dance (Ban Wu), and solo dancing (Du Wu). Although Liang et al. (2021) discussed the relationship styles from student and supervisor perspectives, this study only focused on two aspects, namely the reciprocity level relationship and the trust level of the relationship. However, to obtain fuller picture of the eight types of PhD student-supervisor relationships relevant to this study namely, leadership, helping/friendly, understanding, student freedom and responsibility, uncertain, dissatisfied, admonishing and strict, we will review the literature findings relating to each style separately.

First, the leadership sector is characterized by dominance and cooperation. Supervisors who display a leadership style demonstrate professionalism by organizing research groups and assigning tasks to PhD students. For instance, Davis (2019) identified three key issues of student perceptions of their supervisors: the availability to discharge supervisory duties, the timeliness and quality of feedback, and their supervisors’ professional responsibility and characteristics. Likewise, Gill and Burnard (2008) recommended that students and supervisors create a timeline from the present to the future so that both can see a clear path forward. Moreover, it is critically important for supervisors to perform administrative and expert functions such as recommending experts, organizing communication with students, and helping conduct field research (Gruzdev et al., 2020).

Second, the helping/friendly sector includes behaviors of a more cooperative and less dominant character than the leadership style, and the supervisor might be seen as assisting students, acting friendly, or being considerate. Some studies highlight the importance of PhD students and supervisors explicitly communicating about the responsibilities and expectations of their roles (Cardilini et al., 2022), of the quality and impact of intercultural exchanges (Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019), and of the inspirational atmosphere (Levecque et al., 2017) among student-supervisor relationships.

Third, the understanding sector, characterized by cooperation and submission, includes the behaviors of a more cooperative and less submissive type, and the supervisor might understand, respect, and trust students. The dialogue between the supervisor and PhD student should be honest and open (Thompson et al., 2005). In addition, the supervisor should demonstrate more understanding and empathy for their students and more engagement in their work (Ryan et al., 2022).

Fourth, the student responsibility/freedom sector involves more submissive and less cooperative behaviors than the understanding sector. The supervisor may follow students’ proposals and allow them to make decisions. For example, supervisors see the symmetrical relationship as a critical first step toward fostering students’ independent thinking and self-regulated learning, and ultimately as a precondition for fostering critical thinking (Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019). Likewise, Gill and Burnard (2008) found that the student should also be prepared to take direction and be advised by the supervisor.

Fifth, the uncertain sector involves submission and opposition. The supervisor displaying uncertain behavior might act unconvincingly, with ambiguity regarding student initiatives. PhD students experience a poor supervisory experience in that the supervisor did not set up well-organized meeting arrangements (e.g., Gill and Burnard, 2008) and work timelines (e.g., Beaudin et al., 2016). Moreover, students claimed supervisors sometimes did nothing (Gruzdev et al., 2020) or gave dubious advice (Gunnarsson et al., 2013).

Sixth, the dissatisfied sector also consists of submission and opposition but includes more oppositional and less submissive behaviors. The supervisor may feel disbelieving, dissatisfied, and disappointed in PhD students. Gunnarsson et al. (2013) found that supervisors acknowledged transient disagreements occurred between students and themselves, but no major conflicts. However, disagreement between student and supervisor could aggravate and arouse strong emotions (Gunnarsson et al., 2013).

Seventh, the admonishing sector is characterized by opposition and dominance. The supervisor displaying admonishing behavior might act impatient, irritable, and angry toward PhD students. Han and Xu (2021) found that supervisors got angry when students violated either written or unwritten rules and conventions. This study also identified that the supervisor was irritated when a student missed deadlines repeatedly, informing neither the supervisor nor fellow students of his difficulties in doing research.

Finally, the strict sector, though characterized by opposition and dominance, includes more dominant and less oppositional behaviors. The supervisor may be strict with students, but immediately corrects their mistakes. For instance, Gill and Burnard (2008) found that putting too much pressure on PhD students can be counterproductive, though many students ask for time limits to be set. Moreover, some supervisors are very focused on the research outcome, and not as much focused on the personal development of the PhD student (Berry et al., 2020).

2.3 Literature review: the impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship

The PhD student-supervisor relationship is highly complex and multifaceted (e.g., Gill and Burnard, 2008; Han and Xu, 2021). In this section, literature dealing with the impacts of this relationship will be discussed from two perspectives: the impacts on PhD students and supervisors.

2.3.1 The impacts on students

Scholars have proved that student-supervisor relationships have an impact on well-being (e.g., Cardilini et al., 2022; Dhirasasna et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2022), student performance (e.g., Cardilini et al., 2022; Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019), and study progress (e.g., Gill and Burnard, 2008; Gunnarsson et al., 2013). For instance, PhD students reported that supervisor-student relationships have significantly influenced their well-being (Cardilini et al., 2022; Dhirasasna et al., 2021). Moreover, Elliot and Kobayashi (2019) found that the quality and impact of intercultural exchanges in student-supervisor relationships affect students’ academic performance. Furthermore, Cardilini et al. (2022) highlight the importance of PhD students and supervisors explicitly communicating the responsibilities and expectations of their roles in helping candidates promote research skills and performance. In addition, PhD students claimed that supervisors sometimes gave dubious advice, leading to lost time and affecting their study progress (Gunnarsson et al., 2013). However, research also indicated that a too student-centred relationship may lead to sloppy scholarship and methodology (Gill and Burnard, 2008).

2.3.2 The impacts on supervisors

Although the importance of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on students has been widely examined, the impacts on supervisors have been less investigated (e.g., Hagenauer and Volet, 2014; Spilt et al., 2011). Among the limited evidence, Han and Xu (2021) have identified that supervisory relationships may take a heavy toll on supervisors’ emotions. At school levels, research has revealed that the student and teacher relationships have a great influence on teachers’ personal accomplishment (Corbin et al., 2019), emotional exhaustion (Corbin et al., 2019), work enthusiasm (Rafsanjani et al., 2019), self-efficacy (Lukesh, 2022), and well-being (Spilt et al., 2011) in different contexts. Hence, understanding the impact of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors is a pressing need.

3 Method

This study aimed to explore the PhD student-supervisor relationship and the impacts of this relationship on students and supervisors from both students’ and supervisors’ perceptions. Three research questions were proposed:

RQ1. What are the perceptions of the styles of the PhD student-supervisor relationship?

RQ2. What are the impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on students?

RQ3. What are the impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors?

3.1 Selection of participants

This study targeted both PhD students and their academic supervisors as participants. For PhD students, the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants have to be enrolled in a Doctor of Philosophy program at one of the eight government funded universities in Hong Kong; (2) participants are required to have at least one supervisor overseeing their doctoral journey; and (3) there are no restrictions regarding participants’ age, academic discipline, or year of study.

For supervisors, the inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) participants have to be employed at one of the eight government funded universities in Hong Kong; (2) participants are required to have at least 1 year of experience supervising PhD students; and (3) participants need currently be supervising at least one PhD student.

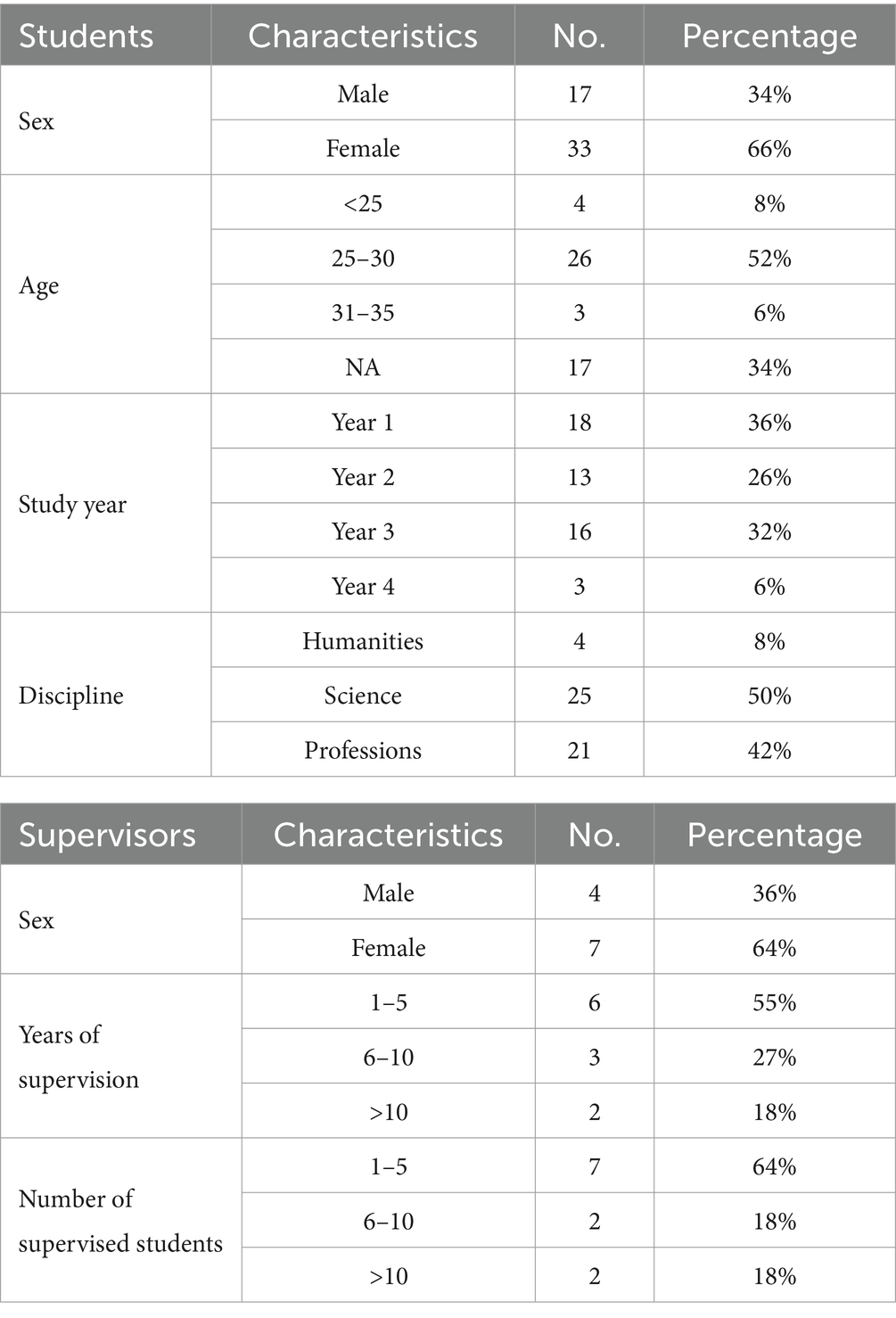

Finally, a total of 50 PhD students and 11 supervisors from eight government-funded universities in Hong Kong were approached in this study. There were 33 female and 17 male students. The majority (83%) were aged from 25 to 30 years with an average of 27 years. Approximately 36% (n = 18) of them were from Year 1, 26% (n = 13) from Year 2, 30% (n = 16) from Year 3, and 6% (n = 3) from Year 4. In terms of discipline, 50% (n = 25) of responders majored in Science, 42% (n = 21) in Professions, and 8% (n = 4) in Humanities (Table 1). As for supervisors, 63.6% (n = 7) were females, and there were 4 males with an average of 7 years of supervision experience. They have mentored an average of five PhD students as principal or associate supervisors.

3.2 Data collection and instruments

For data collection, the convenience sampling strategy and snowball strategy (Edmonds and Kennedy, 2016; Handcock and Gile, 2011) was adopted in this paper. In particular, the research team sent invitation emails to potential participants through a network of contacts established with other universities. Those who met the inclusion criteria and expressed interest were invited to participate. Meanwhile, participants were also encouraged to share the invitation with eligible peers, facilitating additional recruitment through a snowball strategy.

For the interview instruments, the interview protocol was designed to address the research questions and ensure consistency and systematic data collection. In addition to providing participants with the coordinate system of the Leary model and the model of PhD student–supervisor interpersonal behavior for reference, the interview protocol consists of the following three main perspectives. The first perspective aims to explore the status of the PhD student-supervisor relationship from both students and supervisors’ perspectives. Example questions include “How would you describe your overall relationship with your PhD students/supervisors?” and “According to the model for PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior, which type of relationship do you think best describes your interaction with your student/supervisor? Why?” The second perspective focuses on the impact of PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior on students. One example question such as “How does your current relationship with your student/supervisor affect the students’ study?” The third perspective relates to the impact of PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior on supervisors. One example question is “What impact do you think your current relationship with your student/supervisor has on the supervisors.” The interview protocol is guided for both in-depth semi-structured focus group interviews with students and individual interviews with supervisors.

3.3 Study implementation and ethical issues

All interviews were jointly conducted by the first and second authors. For PhD students, 50 participants were first divided into six focus groups and participated in group interview online via Zoom. Then, 11 supervisors were invited to conduct individual interview face to face. The interview locations were selected based on the supervisor’s convenience, with the majority conducted in their offices. Scheduling was arranged according to each participant’s availability. Most interviews lasted approximately 1 hour, with all sessions completed within 90 min in this study. After interview, after the interviews, all audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and subsequently translated into English. The translated transcripts were reviewed by two researchers to ensure accuracy to the original content.

In addition to study implementation, this study strictly followed the ethical issues. Prior to the interviews, all respondents received a participation information sheet and consent form before the interview. They were informed of the background, process, potential risks, and benefits of the research project prior to participating. In particular, participants were made aware of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. All information mentioned during the interview will be kept confidential and will be identified by a code known only to the researchers. All the participants gave their ethic consent for this study.

3.4 Data analysis

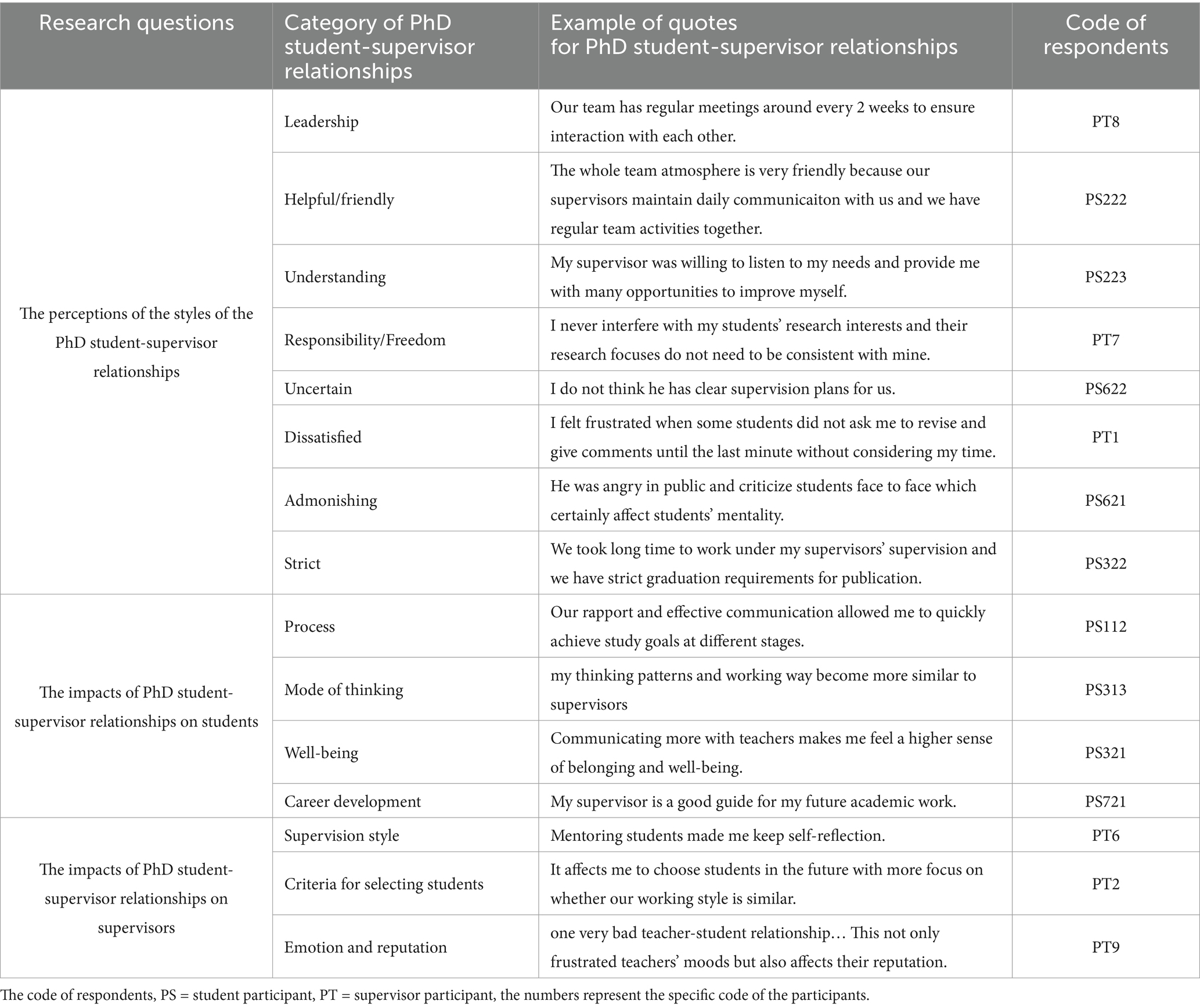

This qualitative study used content analysis, a systematic process of coding textual data for determining trends and themes (Grbich, 2012). A deductive approach was used for data analysis in this study based on the theoretical framework of the model for PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior. In detail, the eight styles of PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior were first identified from the theoretical framework and were used as predefined categories for data coding. The theoretical framework was used to guide the interpretation of the data, which demonstrated a top-down process (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Patton, 1990). During the analysis, the related meaning units of transcriptions were labeled with codes and clarified as corresponding categories and sub-categories. The segments from the interview data were recorded in accordance with these theoretical constructs. To enhance the traceability of the quotes, the respondent code was provided after each citation. Specifically, the prefix “PS” refers to student participants, while “PT” denotes supervisor participants. The accompanying number identifies the specific respondent. Finally, the results that linked to the framework and responded to the research questions were presented (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Sandelowski, 2010) (Table 2 for coding details). Several strategies were implemented to mitigate possible biases and ensure the validity and reliability of data analysis. First, the interviewer engaged in reflective practice following each interview, recording observations and reflections to maintain openness to participants’ viewpoints. Second, the research team utilized double coding to enhance the reliability of the analysis. Third, interviewees were invited to review and provide feedback on the analysis results, thereby ensuring the accuracy of their represented statements.

4 Result

In this section, the results are presented based on the three research questions. Specifically, the perceptions of the eight styles of the PhD student–supervisor relationship are presented first, followed by the results on the impact of the PhD student–supervisor relationship on students, and finally the impact of the relationship on supervisors. Table 2 provides an overview of excerpts addressing the research questions.

4.1 The perceptions of the styles of the PhD student-supervisor relationship

The results concerning eight PhD student-supervisor relationships are outlined below.

4.1.1 Leadership

The leadership type meant that supervisors participated in the planning and management of the learning procedure together with PhD students. Data showed that supervisors tried to maintain communications with their students and adjust the frequency according to the study year and progress of PhD students. One extract from a supervisor supported this perspective:

I learned about my PhD students’ career plans after their graduation at first. I normally provide targeted advice to them in order to serve their purpose during our regular meeting. One of my students would like to pursue working as a researcher in higher education. I told her the related requirements and expectations that she may need to meet, like participating in authoritative conferences and publishing more articles. Then I suggested a specific timeline to achieve the goal, and I will remind them from time to time to make sure their learning is on track. [PT11]

Moreover, the leadership type revealed that supervisors could actively give students clear and comprehensive feedback during their interaction. The feedback from supervisors is diverse in form including formal or casual feedback, written or audio feedback. As one student reported:

My supervisor usually responds to me within a short time. Most comments were written while some feedback toward simple questions I received via audio. It is good for me to receive clear comments so that I can accelerate my study progress. [PS512]

Meanwhile, most supervisors believe they can professionally and confidently express their comments while giving feedback:

I did not receive any questions I cannot respond to so far and I will give advice clearly based on various confusions. There are some commonalities in educational research, especially research methods, even though some students’ specific topics were not very similar to my research focus, I can professionally give core direction and guidance for them to explore. [PT5]

Interestingly, supervisors of the leadership type demonstrated flexibility in their supervision. In detail, they adjust guiding coping strategies depending on the characteristics of PhD students. As one supervisor mentioned:

Some students have higher learning abilities and are clear about what they need to do next, so they just need the general direction and do not need to go into that detail, so that they can get more training. On the other hand, you need to provide guidelines step by step if students have no idea how to cultivate their research competence and confidence. [PT10]

In conclusion, the leadership type showed that supervisors maintain close interaction with their students. They provide professional guidance strategically in different learning procedures, which can satisfy students’ learning needs.

4.1.2 Helping/friendly

The helping/friendly style refers to supervisors who can support and cooperate with their students. Supervisors and students might cooperate to attend conferences and co-write publications under a harmonious and equal team atmosphere. The following extract from a supervisor reveals this view:

When my students come to consult with me, I provide some references and introduce them to some related big potatoes in that field. It can help them to explore solutions on the right track. Emotionally, I always encourage my students without criticism, which can release students’ learning pressure. We brainstorm together and discuss together because learning new things means you need to overcome various difficulties and repeat exploration. [PT2]

I attend some conferences with my PhD students and present together, although I take the majority of the responsibility. On the publication side, I made sure each of my PhD students published articles with at least one piece as the first author and me as the corresponding author. Besides, I would ask them to participate with me in sampling collection and other academic activities. Students would feel a high sense of safety and strengthen their confidence under this supervision. [PT10]

In addition, this relationship is also reflected in the interaction of daily life. Supervisors and students could get along as friends and care for each other. It apparently reduced the reverence and awe with which students treat their supervisor and inspired student well-being. As one student expressed:

Our team will organize different activities to improve communication with each other. We had dined together with our supervisor and hiked together not long ago; these kinds of interactions made us feel at ease and shortened the distance with our supervisor. I felt lucky and happy in such a team. [PS1]

Thus, this helping/friendly sector showed amicable and equal communication mode between supervisors and PhD students, not only in the learning procedure but also in daily life.

4.1.3 Understanding

The understanding mode refers to a supervisor’s ability to cultivate a caring atmosphere within the team. These kinds of supervisors put themselves in students’ shoes and attach importance to listening and empathy. Students’ individual needs are considered by their supervisors. The following scenario may reflect:

It is very difficult for me to balance study and family, which really depressed me some time ago. My supervisor noted that and communicated with me immediately. She shared experiences with me and advised me not to set companionship against learning. Then we scheduled the new timeline considering my family issue, which made me feel less perplexed. [PS223]

Understanding mode emphasizes that instructors are willing to patiently respect and listen to a student’s interests and confusion. They consider appropriate development guidance from the student’s perspective. Students and supervisors also trust each other in this process.

4.1.4 Responsibility/freedom

Responsibility/freedom type refers to giving higher opportunities for independent work to students. Specifically, such supervisors provided a space for students to decide their research topic, methodology, and working schedule. One student shared the experience:

My supervisor gave me lots of freedom to pursue what I was interested in. When I have new ideas, I feel free to talk with him. Besides, he gave us a chance to take risks and allowed us to make mistakes under control. Gradually, we become clear about the direction we put the effort in and become more confident to make decisions by ourselves. [PS231]

Interestingly, this kind of freedom does not mean that supervisors allow students to freely decide all actions. Supervisors would conduct risk assessments on their students during the study process and remind them well before students went completely off track or had diametrically opposed standpoints. As one supervisor shared:

I will estimate the feasibility of my students’ proposals and encourage them to explore the next step on their own if it makes sense. Also, I told them the possible consequences and the costs when they obviously made a wrong decision. A timely reminder can help students adjust their decisions. [PT3]

Responsibility/freedom type relationship suggests that supervisors give students rights and freedom, especially regarding their research project. Meanwhile, they make sure students dance freely on the stage area under control.

4.1.5 Uncertain

The uncertain PhD student-supervisor relationship refers to supervisors who do not appropriately invest in the supervision. These kinds of supervisors lack clear and logical instruction guidance and act ambiguously. Students were confused about their studies to some extent:

My supervisor is too chilled, and he does not seem to have any strong pursuit. I do not think he has clear supervision plans. He does not care about when you graduate and what research outcome you grade with. Sometimes you will be frustrated and helpless because of supervisors’ vague response. [PS622]

Different from the leadership style, students with an uncertain style supervisor reported that they could not receive comprehensive feedback, although their supervisors supported their ideas. Some comments were blurred or unconvincing, which really upset students:

Although he supported my research ideas, we did not keep in close touch and have effective consultation. I do not think I received satisfying feedback from my supervisors, and I had to spend some time trying to figure out what it meant. It is very difficult for me to overcome the bottleneck on my own. [PS212]

Uncertain style reflected that supervisors were short of management and leadership skills. They were unable to provide constructive advice, which easily discouraged students and slowed down their progress.

4.1.6 Dissatisfied

The dissatisfied type of PhD student-supervisor relationship emphasized supervisors’ discontent from two perspectives - personal character and learning performance. As the following quotation from a supervisor expresses:

When some students pursue a PhD just for the degree without being strongly interested in academic research, they perform a low level of intrinsic motivation. They do not initiate to promote progress, and it is resented when you need to remind and push them constantly. Also, I felt frustrated when some students did not ask me to revise and give comments until the last minute without considering my time. My coping strategy is to convey my dissatisfaction with the student face-to-face and discuss a better solution. [PT1]

Unlike the classical type of dissatisfied sector, in which supervisors prefer to keep quiet and wait for silence, our findings indicated that supervisors would point out students’ drawbacks and criticize directly in this kind of interaction.

4.1.7 Admonishing

The admonishing PhD student-supervisor relationship tends to emphasize opposition between students and supervisors. These kinds of supervisors prefer to take pupils to task, showing impatience or even losing their temper when giving feedback. They tend to blame students instead of encouraging them:

My supervisor has a lot of projects, so he asked me to follow up. I mainly take responsibility for data collection, proposal writing, and other trivial matters. We need to tolerate his temper during his supervision because he easily becomes impatient and irritable. Once I helped to arrange a conference, and I got chewed out by him because he thought I did not perform well. His words were so mean and he can blame for a long time. I really think he should control his temper. [PS213]

According to students’ comments, the supervisors’ reproachful words and the tense atmosphere within the team made them extremely stressed. As one participant shared:

Sometimes I think our supervisor is going too far. He was angry in public and criticized students face-to-face, which certainly affects students’ mentality. One of my team members sobbed secretly and was very depressed after the meeting. [PS621]

Supervisors’ impatience and anger toward PhD students obviously aggravate the tension of the student-supervisor relationship and have a negative influence on students’ mental health development.

4.1.8 Strict

The strict PhD student-supervisor relationship involves supervisors exacting norms and setting explicit rules during tutoring. They keep reins tight to ensure students achieve scheduled goals. The following extracts supported it:

We must be serious about academic ethics-related issues and require the quality of the publications. Only strict requirements can distinctly establish student foundation. Pointing out problems solemnly and criticism can let students realize the importance and avoid mistakes again. [PT5]

Interestingly, some students did not reject this kind of relationship. Students thought it could enhance their capacity eventually and graduate successfully, even though they sometimes received judgments from supervisors. For instance, one participant shared:

Our team has strict regulations and we need to report each process of the tasks to our supervisors. My supervisor had a higher standard and sometimes would criticize students if we did not meet expectations. However, I made great progress compared to before. Being dominated by supervisors is not such a bad thing if you have a high level of bounciness. [PS523]

Thus, strict type emphasized the domination of supervisors as an authority. This kind of relationship was acceptable for some students.

Overall, the results reveal eight different types of PhD student-supervisor relationships as described in the model for PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior. Based on the coding record and findings, the first four types of relationship (i.e., Leadership, Helpful/Friendly, Understanding, and Responsibility/Freedom) were predominant among the respondents. Collectively, the findings in this study amplify our understanding of eight styles of PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior, mapping a diverse picture of academic communication between teachers and students. The significance of how supervisors get along with students is increasingly recognized.

Interestingly, in addition to experiencing eight specific styles, some participants reported mixed styles out of these eight styles. For instance, some supervisors have strict requirements in terms of academic issues, but they are friendly to help students with daily life issues:

Our supervisor emphasized the principles, such as academic integrity and ethics issues. He also very much cared about commitment. One group member has been criticized in public for not meeting the deadline. I can understand his rigor in research…He would ask us if we needed help in daily life. He even helped us to rent the apartment, which prevented us from being cheated by the housing agents. [PS233]

It can be concluded that the PhD student-supervisor relationship is complex in nature rather than simply classified into eight styles. The findings in this study support that the PhD student-supervisor relationship could be at any location on the continuum matrix.

4.2 The impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationship on students

The impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationship on students were understood. First, both students’ learning progress and academic achievement were directly influenced. Specifically, healthy and positive relationships accelerated student progress to complete learning tasks on time, while negative relationships hindered them:

My supervisor communicated well with me and we planned each short-term goal together. It gave me clear direction and big confidence that each goal is achievable. Now I have completed the data collection for my own project and published one article. Everything is in the plan. [PS111]

He was more concerned about his project than putting himself in my shoes. His comments were too general, and it took me a longer time to solve the problem by myself. [PS622]

Second, interactive relationships between students and supervisors were found to affect students’ mode of thinking and their professional literacy. As one student participant mentioned:

When cooperating with supervisors, you can learn more from them. Their rigorous academic norms, open-minded attitude, and broad academic vision, for example, impressed me deeply. Gradually, my thinking patterns and working ways became more similar to those of my supervisors. [PS313]

Third, student-supervisor interpersonal behavior also significantly influenced students’ emotions and well-being. Pleasant relationships alleviated students’ learning pressure but enhanced happiness and learning motivation. Unpleasant relationships might have opposite functions. These could be seen from the following scenarios:

My high level of well-being came from my supervisor’s clear and logical guidance. I am confident that I will produce a rich harvest when working with him, which makes me feel less anxiety compared with other PhD students. [PS232]

I often fall into emotional frustration after meetings with my supervisor. I felt I was useless and depressed all day long. I tend to burnout from my research under this kind of vicious circle and even thought of quitting. [PS821]

Fourth, the PhD student-supervisor relationship also affected students’ career development and academic interpersonal network building. One student reported:

A good relationship between supervisors and students continues to be cooperative and helps each other even after graduation. The resources provided by my supervisor gave me more opportunities to contact other experts in our research field. These benefits will enable me to pursue academic research in the near future. [PS412]

Overall, the PhD student-supervisor relationship in this study apparently affected student learning progress, skill development, academic outcomes, well-being, and career plans in the future.

4.3 The impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors

The consequences of PhD student-supervisor behavior on supervisors were also examined. The most frequent impact mentioned by supervisors was that it encouraged them to reflect on their communication and supervision style. As one supervisor shared:

Supervisors and students learn from each other during the supervision process. Mentoring students made me practice self-reflection, like when I should establish authority and provide detailed guidance, or when I should let students take the initiative. Rethinking and adjusting the instruction way appropriately can promote efficient communication and save each other time. [PT6]

Besides, it cannot be neglected that supervisors’ criteria for selecting students would be affected. Supervisors identified and summarized different students’ personalities and working styles during past supervision experiences. After that, they knew how to select the most suitable type of student to supervise in the future:

I certainly reflected and learnt lessons from past experience, especially negative experience, with students and know what kind of students we might not get along well with each other. I then try not to recruit these kinds of students so it will prevent unpleasant supervision to the maximum extent. [PT2]

Some supervisors also mentioned the influence that the student-supervisor relationship had on their emotions and reputations. One supervisor participant conveyed:

I think a good teacher-student relationship is a happy process for teachers. Frankly speaking, it may not have much influence on teachers’ emotions. However, one very bad teacher-student relationship will greatly worry the teacher compared with a good one. This not only frustrates teachers’ moods but also affects their reputation. [PT9]

In conclusion, the impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors were mainly reflected in three aspects, namely, supervisors’ reflection on coaching style, standards of selecting students, and supervisors’ emotions and reputation.

5 Discussion

This section outlines the major findings regarding the PhD student-supervisor relationship based on the model of interpersonal supervisor behavior (Mainhard et al., 2009), and its impact on students and supervisors by intertwining with the existing literature.

5.1 PhD student-supervisor relationship

Guided by the interpersonal behavior model, this study illuminated eight types of PhD student-supervisor relationships. As expected, four out of the eight interpersonal PhD student-supervisor relationship types were more frequently mentioned in this study, namely leadership, helping/friendly, understanding, and student responsibility and freedom. Which is consistent with previous studies (Mainhard et al., 2009). This result also resonates with Levy et al.'s (1993) finding that the ideal or best teachers preferred more cooperative and fewer oppositional behaviors.

First, the participant supervisors showed leadership-type interpersonal behaviors such as communicating with students frequently, giving clear and comprehensive feedback, and expressing their comments professionally and confidently, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Davis, 2019; Gill and Burnard, 2008). As well as these normal leadership style behaviors, this study found that supervisors demonstrated flexibility in their supervision management. This is an important finding in understanding and enriching knowledge about the leadership type interpersonal behaviors. Second, in line with previous studies (e.g., Gruzdev et al., 2020), the results indicated that the helping/friendly type of interpersonal behavior of both supervisors and students not only includes cooperation in conferences and publications but also the interaction of daily life. Interestingly, supervisors and students in this relationship type are like friends and care for each other. A possible explanation for this might be that Confucius’ thought (e.g., good teachers and helpful friends) has a great impact on students and supervisors in the Chinese context (Waley, 2012). Third, the results revealed the understanding type behaviors in which supervisors demonstrated understanding and empathy for their students’ individual needs, which echoes with previous studies (e.g., Ryan et al., 2022). Moreover, some PhD students in this study also indicated that their supervisor considered appropriate development guidance from the student’s perspective. This echoes with the finding that a supervisor’s compassion is viewed as a pro-social process (Lundgren and Osika, 2021), leading to an understanding and caring atmosphere between supervisors and students. Fourth, the participant supervisors demonstrated the responsibility/freedom type of interpersonal behavior, including giving PhD students certain autonomy to make decisions in their research project, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019). This result also resonates with a finding in the Chinese context that doctoral students are leading the dance and conduct research with autonomy, while the supervisor plays a role as a facilitator (He and Zhu, 2022). One possible explanation is that the objectives of a PhD program may focus on advancing knowledge for professional improvement, critical thinking, and practical innovation (Graduate School, 2025).

The other four interpersonal PhD student-supervisor relationship types that were also explored in this study were not as frequent as the first four styles. This also reflects the specific manifestation of the interpersonal model within the Hong Kong context. For instance, the first style, the uncertain type, indicated that the supervisor provided incomprehensive, blurry, and insufficient comments to PhD students, which is consistent with earlier studies (e.g., Berry et al., 2020). In this case, PhD students performed a solo dance and had to engage in the research enterprise on their own (He and Zhu, 2022). A possible explanation for this might be that supervisors believed they gave more guidance to candidates than candidates perceived they received (Cardilini et al., 2022). Second, the participant supervisors showed dissatisfied type interpersonal behaviors such as discontent with PhD students’ personalities and learning performance, which resonates with previous studies (e.g., Gunnarsson et al., 2013). Third, this study found that supervisors showed impatient and tantrum-like behaviors to PhD students as part of the admonishing type of interpersonal behavior. This may be because a supervisor with a low capacity for compassion could react with admonishing behavior and an increase in submissive behavior (Lundgren and Osika, 2021). Finally, the participant supervisors demonstrated strict type interpersonal behaviors such as setting explicit rules and a rigid goal for research outcomes (e.g., publications), which is in accord with recent studies (e.g., Berry et al., 2020) indicating that this kind of behavior puts too much pressure on students (e.g., Gill and Burnard, 2008). Surprisingly, some PhD students in this study identified that they can adapt to this type of relationship with their supervisor. This may be because the PhD student-supervisor relationship in Chinese societies is embedded in socio-cultural traditions, such as the “well-known Chinese sayings, zunshi zhongdao (honour the teacher and respect his teacher) and yanshi chugaotu (harsh teachers produce good students), predominate” (Tsui and Ngo, 2016, 366–367).

Interestingly, this study also found that PhD student-supervisor relationships are not always static, sometimes they are dynamic and changing by mixing different styles. For instance, supervisors demonstrate strict type or freedom type interpersonal behaviors based on PhD students’ individual capabilities and personalities. On the other hand, some supervisors showed several types of interpersonal behavior such as leadership and helping/friendly type, which resonated with earlier studies (Levy et al., 1993). The findings have extended our knowledge of the interpersonal relationship between students and supervisors in a doctoral context, but also provide implications for other educational levels.

5.2 The impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationship on students

This study found that the PhD student-supervisor relationship had impacts on students, including study progress and academic outcomes, individual professional capacity, career orientation and networks, and emotion and well-being. Particularly, a friendly and harmonious student-supervisor relationship has a positive impact on students’ academic experiences through increases in professional literacy, learning experience, and research outcomes, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Dhirasasna et al., 2021; Mosley et al., 2014). Moreover, the PhD student-supervisor relationship affects students’ career development and academic social networks, which resonates with recent studies (e.g., Cardilini et al., 2022). Surprisingly, only a few PhD students indicated the impacts of the relationship on their well-being and emotions. This finding goes exactly counter to the growing body of research that has revealed the consequences of PhD student-supervisor relationships on students’ well-being (e.g., Cowling, 2017; Kusurkar et al., 2022). A possible explanation for this might be that Hong Kong PhD students, like those in other Chinese societies, are pressured to study hard and prepare well for the high-pressure academic atmosphere (Tsang and Lian, 2021), resulting in a resilient awareness of their well-being and happiness.

5.3 The impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors

This study also investigated the impact of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on the supervisors ‘response to the identification of a research gap in the doctoral literature (Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019). The impacts of the PhD student-supervisor relationship on supervisors may involve supervisors’ emotions, reputations, reflection on coaching style, and selection criteria for students. For instance, the participant supervisors indicated that a negative student-supervisor relationship not only destroyed their well-being but also affected their reputation, which echoes findings from other studies (e.g., Han and Xu, 2021). Furthermore, based on the PhD student-supervisor relationship and experiences, the supervisors are prompted to rethink and adjust their supervision styles and the criteria for selecting students. The results in this study contribute to the knowledge of the impacts of PhD student-supervisor relationships on supervisors in the Asian context and beyond.

6 Contributions and implications

This study draws several conceptual, theoretical, and practical implications. First, the study confirms and broadens knowledge about eight styles of PhD student-supervisor relationships, including both positive and negative interpersonal behaviors from students and supervisors’ perceptions. The findings contribute to a deeper conceptual understanding of some different types of student-supervisor relationships in the Hong Kong context. Future studies may empirically examine the ideal student-supervisor relationship in different contexts to accelerate its positive impact on students and supervisors in real life. Second, the doctoral supervision relationship between student and supervisor is like that of any team in an organizational setting (Gunasekera et al., 2021). Hence, drawing from the interpersonal relationship model (Mainhard et al., 2009), this study offers a theoretical basis to explore multidimensional student-supervisor relationships. Such a theoretical base can provide exemplars for supervisors and students to identify more appropriate styles for their own use, such as more cooperation and fewer oppositional behaviors (Levy et al., 1993). Third, in the fragile and high-pressure academic atmosphere of PhD students, the impact of supervisors’ frequent communications, clear and comprehensive feedback (e.g., Davis, 2019) on students’ research experience, research outcomes, and their professional capacity should not be underestimated. Fourth, this study also offers recommendations on university policies aiming to enhance the PhD student-supervisor relationship in order to boost positive impacts and alleviate negative impacts in the Hong Kong context and provide implications for other contexts.

7 Limitations and directions for future research

Despite the significant contributions, there are a few limitations associated with this study. First, the sampling strategy primarily utilized convenience sampling through the professional networks, with a limited sample size. This might constrain the generalization of the findings. Future studies may try to use a random sample and expand the sample size to alleviate this drawback. Second, this study used self-reported and focus group interviews. Future studies may utilize multiple data sources, such as longitudinal, experimental studies, or case studies, to explore a fuller picture of the PhD student-supervisor interpersonal behavior. Third, this article provided a comprehensive analysis of the perspectives of PhD students and supervisors on their relationship. Future research may examine them separately to uncover potential differences in viewpoints and enhance comparative understanding. Fourth, this study only focused on supervision styles and their impacts on students and supervisors. Future studies may pay attention to the influential drivers (Lundgren and Osika, 2021) of the supervision styles and the impacts on students and supervisors. In doing so, preventions and interventions might be developed to promote positive supervision relationships, which would boost positive impacts and alleviate negative impacts on students and supervisors.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Education University of Hong Kong. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the University Grants Committee of Hong Kong under Grant number 18612119.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Beaudin, A., Emami, E., Palumbo, M., and Tran, S. D. (2016). Quality of supervision: postgraduate dental research traineesperspectives. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 20, 32–38. doi: 10.1111/eje.12137

Berry, C., Valeix, S., Niven, J. E., Chapman, L., Roberts, P. E., and Hazell, C. M. (2020). Hanging in the balance: conceptualising doctoral researcher mental health as a dynamic balance across key tensions characterising the PhD experience. Int. J. Educ. Res. 102:101575. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101575

Byrom, N. C., Dinu, L., Kirkman, A., and Hughes, G. (2022). Predicting stress and mental wellbeing among doctoral researchers. J. Ment. Health 31, 783–791. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1818196

Cardilini, A. P., Risely, A., and Richardson, M. F. (2022). Supervising the PhD: identifying common mismatches in expectations between candidate and supervisor to improve research training outcomes. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 613–627. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1874887

Corbin, C. M., Alamos, P., Lowenstein, A. E., Downer, J. T., and Brown, J. L. (2019). The role of teacher-student relationships in predicting teachers personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion. J. Sch. Psychol. 77, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.001

Cowling, M.. (2017). Happiness in UK post-graduate research in UK HEIs. Higher Education Academy. Available online at:https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/happiness-uk-post-graduate-research-uk-heis. [Accessed October 7, 2022].

Davis, D. (2019). Students perceptions of supervisory qualities: what do students want? What do they believe they receive? Int. J. Doctoral Stud. 14, 431–464. doi: 10.28945/4361

Dhirasasna, N., Suprun, E., MacAskill, S., Hafezi, M., and Sahin, O. (2021). A systems approach to examining PhD students well-being: an Australian case. Systems 9:17. doi: 10.3390/systems9010017

Edmonds, W. A., and Kennedy, T. D. (2016). An applied guide to research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Elliot, D. L., and Kobayashi, S. (2019). How can PhD supervisors play a role in bridging academic cultures? Teach. High. Educ. 24, 911–929. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1517305

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Gatfield, T. (2005). An investigation into PhD supervisory management styles: development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 27, 311–325. doi: 10.1080/13600800500283585

Gill, P., and Burnard, P. (2008). The student-supervisor relationship in the PhD/doctoral process. Br. J. Nurs. 17, 668–671. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.10.29484

Graduate School (2025). Prospective Students. The University of Hong Kong. Available online at: https://gradsch.hku.hk/prospective_students/programmes/doctor_of_philosophy (Accessed June 4, 2025).

Gruzdev, I., Terentev, E., and Dzhafarova, Z. (2020). Superhero or hands-off supervisor? An empirical categorization of PhD supervision styles and student satisfaction in Russian universities. High. Educ. 79, 773–789. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00437-w

Gunasekera, G., Liyanagamage, N., and Fernando, M. (2021). The role of emotional intelligence in student-supervisor relationships: implications on the psychological safety of doctoral students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 19:100491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100491

Gunnarsson, R., Jonasson, G., and Billhult, A. (2013). The experience of disagreement between students and supervisors in PhD education: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 13:134. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-134

Hagenauer, G., and Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher–student relationship at university: an important yet under-researched field. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 40, 370–388. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

Han, Y., and Xu, Y. (2021). Unpacking the emotional dimension of doctoral supervision: supervisors emotions and emotion regulation strategies. Front. Psychol. 12:651859. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651859

Handcock, M. S., and Gile, K. J. (2011). Comment: on the concept of snowball sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 41, 367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01243.x

He, F., and Zhu, Z.Y.. (2022). Learning from others: An alternative approach for doctoral students to traditional mentoring. Educating postgraduates on educational management and administration in the new times: Diverse perspectives and practices. China (online). [conference presentation].

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Jackman, P. C., and Sisson, K. (2022). Promoting psychological well-being in doctoral students: a qualitative study adopting a positive psychology perspective. Stud. Grad. Postdoc. Educ. 13, 19–35. doi: 10.1108/SGPE-11-2020-0073

Kremer-Hayon, L., and Wubbels, T. (1993). “Supervisors interpersonal behavior and student teachers satisfaction” in Do you know what you look like? Interpersonal relationships in education. eds. T. Wubbels and J. Levy (London: The Falmer Press), 135.

Kusurkar, R. A., Isik, U., van der Burgt, S. M., Wouters, A., and Mak-van der Vossen, M. (2022). What stressors and energizers do PhD students in medicine identify for their work: a qualitative inquiry. Med. Teach. 44, 559–563. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.2015308

Leary, T. (1957). An interpersonal diagnosis of personality. United States: The Ronald Press Company.

Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J., and Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Res. Policy 46, 868–879. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.008

Levy, J., Créton, H., and Wubbels, T. (1993). “Perceptions of interpersonal teacher behavior” in Do you know what you look like? Interpersonal relationships in education. eds. T. Wubbels and J. Levy (Brighton, England: Falmer Press), 29–45.

Liang, W., Liu, S., and Zhao, C. (2021). Impact of student-supervisor relationship on postgraduate students subjective well-being: a study based on longitudinal data in China. High. Educ. 82, 273–305. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00644-w

Lukesh, A. R. (2022). Teacher-leader, teacher-teacher, and teacher-student relationships: Which makes a difference in teacher self-efficacy in US middle schools [doctoral dissertation]. Lincoln, Nebraska: The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Lundgren, O., and Osika, W. (2021). Cultivating the interpersonal domain: compassion in the supervisor-doctoral student relationship. Front. Psychol. 12:567664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.567664

Mainhard, T., Van Der Rijst, R., Van Tartwijk, J., and Wubbels, T. (2009). A model for the supervisor–doctoral student relationship. High. Educ. 58, 359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8

Mosley, C., Broyles, T., and Kaufman, E. K. (2014). Leader-member exchange, cognitive style, and student achievement. J. Leadersh. Educ. 13, 50–69. doi: 10.12806/V13/I3/R4

Park, K. E., Sibalis, A., and Jamieson, B. (2021). The mental health and well-being of masters and doctoral psychology students at an urban Canadian university. Int. J. Doctoral Stud. 16, 429–447. doi: 10.28945/4790

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

Rafsanjani, M. A., Pamungkas, H. P., and Rahmawati, E. D. (2019). Does teacher-student relationship mediate the relation between student misbehavior and teacher psychological well-being? J. Account. Bus. Educ. 4, 34–44. doi: 10.26675/jabe.v4i1.8411

Ryan, T., Baik, C., and Larcombe, W. (2022). How can universities better support the mental well-being of higher degree research students? A study of students suggestions. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 867–881. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1874886

Sandelowski, M. (2010). Whats in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 33, 77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M., and Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: the importance of teacher–student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 457–477. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L., and Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: a review of the factors influencing doctoral students completion, achievement, and well-being. Int. J. Doctoral Stud. 13, 361–388. doi: 10.28945/4113

Thompson, D. R., Kirkman, S., Watson, R., and Stewart, S. (2005). Improving research supervision in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 25, 283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.01.011

Tsang, K. K., and Lian, Y. (2021). Understanding the reasons for academic stress in Hong Kong via photovoice: implications for education policies and changes. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 41, 356–367. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2020.1772719

Tsui, A. P. Y., and Ngo, H. Y. (2016). Social-motivational factors affecting business students cheating behavior in Hong Kong and China. J. Educ. Bus. 91, 365–373. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2016.1231108

University Grants Committee. (2022). About our universities. https://cdcf.ugc.edu.hk/cdcf/statEntry.action. [Accessed October 7, 2022].

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., and van Tartwijk, J. (2006). “An interpersonal perspective on classroom management in secondary classrooms in the Netherlands” in Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. eds. C. Evertson and C. Weinstein (New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 1161–1191.

Keywords: PhD students, supervisor, student-supervisor relationship, interpersonal relationship model, interpersonal behavior

Citation: Li Y, Xu W and Chen J (2025) PhD student-supervisor relationship and its impacts: a perspective of the interpersonal relationship model. Front. Educ. 10:1570137. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1570137

Edited by:

Eva Hammar Chiriac, Linköping University, SwedenReviewed by:

Theophilus Adedokun, Durban University of Technology, South AfricaSuhalia Parveen, Aligarh Muslim University, India

Copyright © 2025 Li, Xu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junjun Chen, ampjaGVuQGVkdWhrLmhr

†ORCID: Yingxiu Li, orcid.org/0000-0002-8555-842X

Wendan Xu, orcid.org/0000-0002-2312-9478

Junjun Chen, orcid.org/0000-0002-1549-7991

Yingxiu Li

Yingxiu Li Wendan Xu

Wendan Xu Junjun Chen

Junjun Chen