- 1Global Advisors and Analysts, LLC, Grayson, GA, United States

- 2Department of Biology, Grinnell College, Grinnell, IA, United States

Many colleges and universities purport agendas involving strategies centered on the readiness to diversify the faculty, staff, and student bodies, modernize curricula, and promote innovation in research and discovery, among other advancements. However, higher education institutions remain reticent in addressing these variables over the long term and are slow to change. In this article, we argue that impediments to change continue to exist because many conflate willingness to change with readiness for change. We seek to support institutions in identifying and amplifying facilitators—both progressive leaders and stakeholders—who will be supported to assess an institution’s current state and to advocate, facilitate, and help lead the shift to a state of readiness for change to engender improved institutional performance and impact. True commitment to or readiness for change depends on an institution’s ability to accurately conduct a system-wide assessment to identify and safeguard strengths, recognize gaps, and maximize leverage points, i.e., points of likely effective intervention—all of which are necessary to reimagine a progressive and sustainable path forward that would drive an effective redesigning process and the development of system traits to promote meaningful change. Entities that are genuinely committed to change may need to implement interventions or mitigate constraints associated with human capital and personnel (talent identification, support, and retention), economic levers or financial barriers, environmental stewardship, cultural inertia or toxicity, policies and processes, leaders and stakeholders who maintain the status quo or act as gatekeepers, and traditional reward systems. Functional entities within institutions may exist in various disparate states of willingness and readiness, and may progress in a dissonant way, lacking the consensus of effective change-ready leadership. Institutions that can successfully pivot from willingness alone to willingness that facilitates readiness will achieve progressive institutional visions, processes, and implementation. Some may even transition beyond readiness for change to attaining a more dynamic, aspirational position.

1 Introduction

Many academic institutions lead on a premise of innovation and cutting-edge education, teaching, and research. However, many of these institutions are motivated by peer or aspirant higher education entities to employ evidence-based practices that are often based on a plug-and-play implementation of established strategies and policies. In practice, such an approach usually involves rote replication. Institutions need to look beyond the established narrative of comparisons to position themselves as viable enterprises that are worthy of investments and who can be trusted to use public (and private) funds to reliably provide quality education and services to the communities and constituents that they serve. To achieve this, institutions should go beyond the mere use of evidence-based practices and adopt evidence-based—as well as novel—innovations that take into account institutional context and history (Dryden-Palmer et al., 2020; Montgomery and Black, 2025; Whittaker and Montgomery, 2022). We have previously defined evidence-based innovation in the context of higher education as the implementation and “use of new parameters and metrics for assessing evolved frameworks of scholarship based on non-standard outputs and integrated collaborative and interdisciplinary efforts” (Whittaker and Montgomery, 2022).

The complexity of the higher education ecosystem has been associated with “cultural legacies, differences among disciplines, and resource disparities across institutions” (Lombardi et al., 2020). Many higher education institutions have historically not been appropriately prepared, equipped, or positioned to effectively compete in the academic landscape using either evidence-based replication or innovation. Moreover, the playing field is not level, with “flagship” institutions being most economically and, perhaps, politically well positioned to serve as comparator, aspirational entities—even within the context of their own struggles to traverse the (Carnegie or Global) institutional rankings or fully live up to the values and commitments that they espouse. Such institutions are generally buoyed by disproportionately higher amounts of investments of public (state and federal) as well as private (foundation and development) funds (Sav, 2010; Danner, 2020; Mugglestone et al., 2019). To mitigate the academic inertia that can be prevalent across the higher education landscape, institutions must be willing to reassess their practices and break barriers, and even some traditions, to enact or facilitate change. Consistent, disciplined effort will, therefore, be required to drive transformation and add value in a manner that is compatible with the relevant institutional contexts.

A significant challenge to realizing necessary change in the higher education ecosystem is that many institutions claim to be ready to change, but this does not appear to be the reality for some of them. In actuality, institutions exist on a continuum from being resistant to change to being willing to change to being truly ready for change. In order to approach true readiness, institutions need to be open to consistent self-reflection, strategic thinking and interventions, and an accurate assessment of where they currently are to prepare them for the efforts—and, most likely, transformations or reforms—needed to genuinely be ready for change.

2 Willingness and readiness defined

A “willing” institution is one that recognizes the importance of consistent self-assessment and its need to change. When change is appropriate, such organizations must move to assess their current state and identify clear steps to achieve the required change as well as commit time and resources for the same. However, even when organizations recognize a need for adaptation or change, cultural inertia may impede direct action and implementation and delay or hinder them from moving beyond the common cycle of education and engagement that can be separate from effective or lasting action and implementation, thus leading to a failure to appropriately engender and sustain change (Montgomery, 2018).

An institution that is “ready” is one that can face its challenges or deficits and is prepared to leverage capabilities and strengths to reinvent itself. Such organizations are distinct from those that are resistant to, not ready for, or only willing to change. In organizations that are willing but not ready to change, leaders may espouse commitments to particular values, prestige, or principles without employing practices that assess whether their lived experiences align with those commitments or without appropriately pursuing expertise or resources to support the achievement of this alignment (Montgomery and Whittaker, 2022). Such institutions can become stagnated or anchored in the willingness stage due to a lack of understanding or leadership aptitude for facilitating the needed change (Montgomery and Black, 2025). In contrast, institutions that are ready to change prioritize connecting the disconnected, are able to adopt a systems-oriented perspective to strategically navigate challenges, and actively work to drive cultural transformation to align their lived practices and policies with their stated values and commitments.

Numerous organizational change frameworks exist in the literature that have relevance in higher education settings for promoting systems level change (e.g., Fullan, 2020; Foster-Fishman et al., 2007; Meyer and Stensaker, 2006; Montgomery and Black, 2025; Redmond et al., 2008; Schein, 2008; Lewin, 1947). Lewin’s (1947) classic model for organizational change is built on three steps: unfreezing, moving, and refreezing (pp. 34–35). The unfreezing stage occurs when an organization recognizes a need for change and prepares to transition from a current state. The second step is a period of active change, or moving, during which new practices or behaviors are instituted. Schein (2008) identified a challenge during the change step in Lewin’s model as recognizing and navigating the reality of “having to unlearn something before something new can be learned” (p. 78). Relatedly, built on applying Edward Deming’s well-known organizational transformation principles to higher education, Redmond et al. (2008) highlight the importance of identifying and dismantling barriers to change and recognizing the importance of cultural change work for supporting overall organizational change efforts. The third step in Lewin’s (1947) model is refreezing, or the establishment of a new and improved equilibrium state. Additional approaches for institutional change include Foster-Fishman et al.’s (2007) recognition that “systems change is an episodic and transformative change pursuit that is fundamentally about shifting the status quo by altering the elemental form and function of a system” (p. 201). Fullan (2020) argues that effective organizational change more often than not involves proactively, rather than reactively challenging the status quo (p. 5). Furthermore, Foster-Fishman et al. (2007) assert the effectiveness of identifying pre-existing levers that can be used to cultivate needed change (p. 200). Ultimately, we argue that deciding on which organizational change approach may be most appropriate for a particular institution requires understanding an institution’s state of readiness for change.

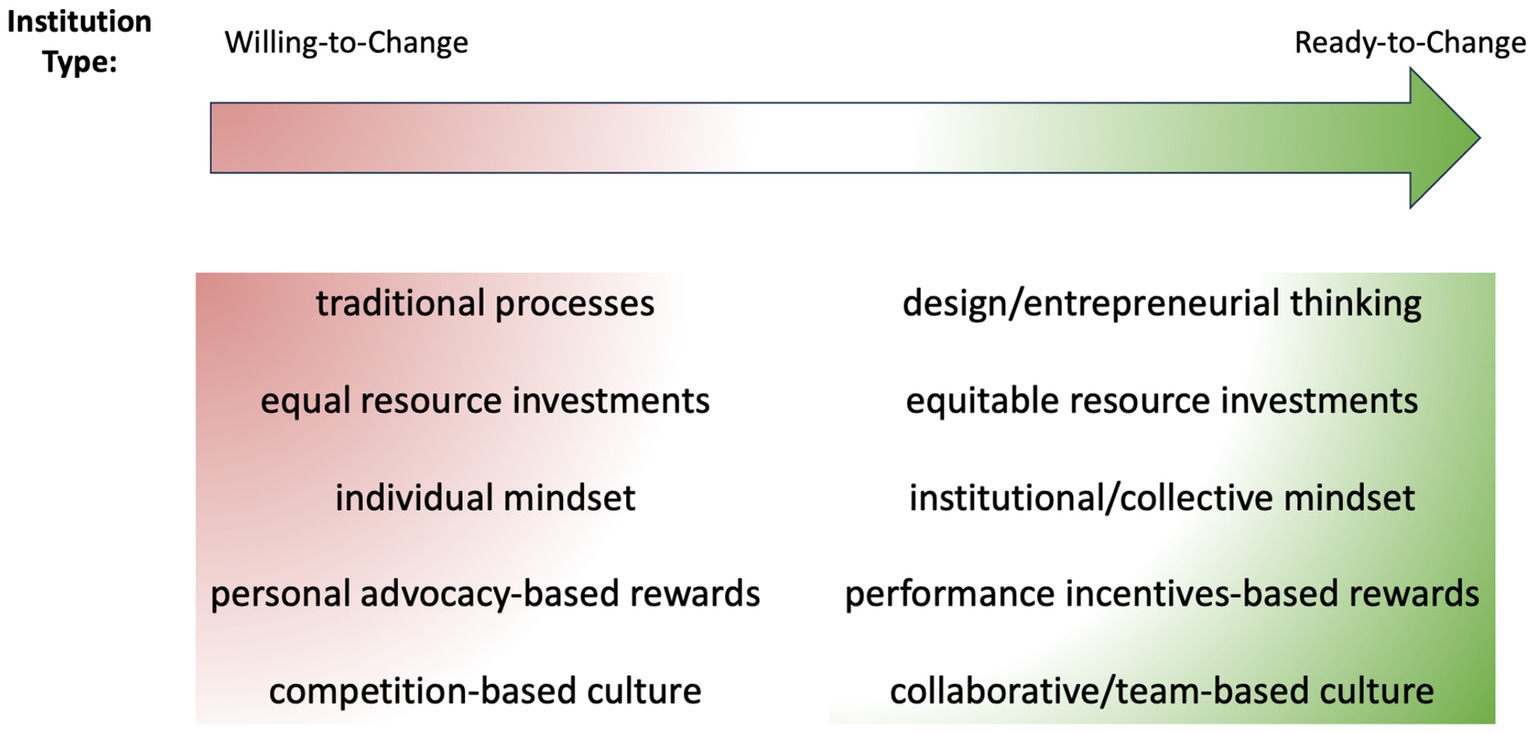

Independent of the strategy or approach chosen to implement organizational change, there are clear distinctions between organizations that are willing to change and those that are ready for change. Understanding these distinctions is critical as many of the well-known organizational change models point out the problems that arise when leaders do not pay attention to addressing the pushback or resistance to change that frequently exists in organizations (Meyer and Stensaker, 2006; Whittaker and Montgomery, 2022). The distinctions in organizations that are willing to change vs. ready to change occur across multiple dichotomies: traditional vs. design/entrepreneurial thinking, equal vs. equitable reward systems, individual vs. institutional/collective mindset, personal advocacy-based vs. performance incentive-based reward systems, and competition- vs. collaborative-based cultures (Figure 1). Workplace culture and leadership styles are critical variables for achieving transformation and success when moving from being willing to being ready for organizational change (e.g., Hanna, 2017; Knowles et al., 2023; Rieg et al., 2021; Xenikou, 2019).

3 Institutional factors correlated with readiness for change

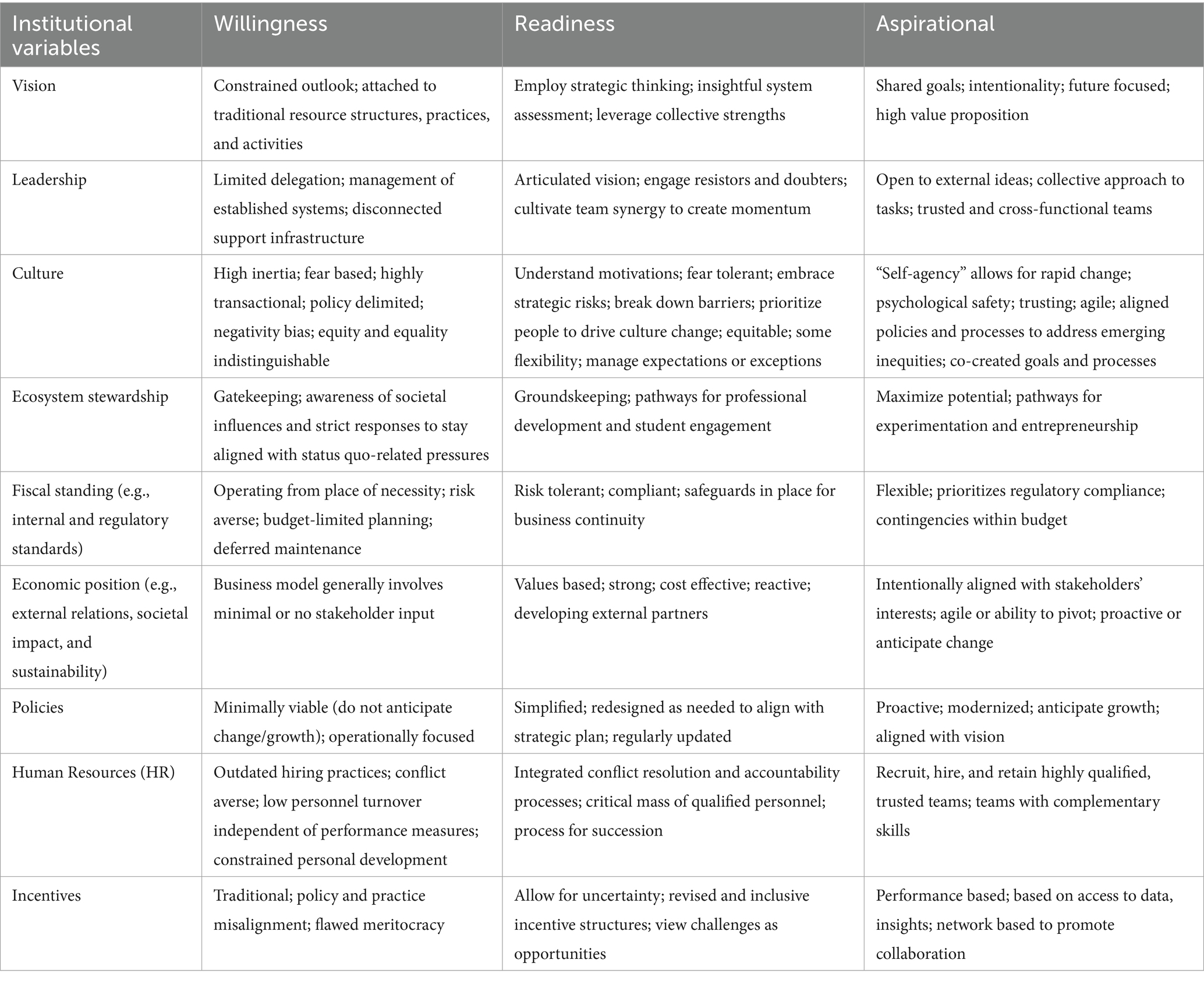

Academic institutions are inherently complex in terms of operations. Progress in these institutions is dependent upon the complex interactions between people, environment, systems, and processes, areas previously identified as critical for organizational stewardship and transformation (e.g., Caldwell et al., 2023; LaRoche and Yang, 2014). Several key institutional factors or variables in institutional ecosystems that are related to people, systems, environment, and processes and their current status in an institution reflect whether an entity is ready to change, willing to change, or in a state of aspirational dynamic functioning. These factors, also referred to as ecosystem variables, are discussed in this section and include vision, leadership, culture, ecosystem stewardship, fiscal functioning (e.g., internal and regulatory standards), economic position (e.g., external relations, societal impact, and sustainability), policies, human resources (HR), and incentive structures (Table 1).

3.1 Vision

Being ready for change requires leaders to articulate and obtain buy-in for an institutional vision (Cheruvelil and Montgomery, 2019; Kotter, 1996; Montgomery, 2020). Leaders should be mission- and purpose-driven and, thereby, avoid the sole pursuit of traditional short-term priorities, goals, and prestige. Indeed, in a meta-analysis of studies on organizational change for sustainability in higher education, Rieg et al. (2021) identified leader-driven and stakeholder-supported vision as a critical factor in supporting successful change efforts. In creating momentum toward envisioned change and transformation, academic leaders should recognize and possibly re-envision the human factors and the cultural contexts in which work is performed. Obtaining stakeholder buy-in and alignment with the shared goals and purpose is essential regardless of whether an institution is willing or ready to change. Nonetheless, strategic visioning must include action steps, benchmarks, and opportunities for experimentation as key roadmap markers for assessing progress toward the envisioned transformational outcomes. The inability of leaders to model and cultivate cohesion, trust, and clarity with regard to vision and purpose often results in fragmented, misaligned priorities, with resources being allocated to the domain functionalities of stakeholders rather than the system-wide stewardship that is necessary for all to thrive and advance.

3.2 Leadership

Frequently, well-intended programs and strategies for institutional progress and transformation lack appropriate leadership and necessary effectiveness. Relevant initiatives also can be hampered by traditional processes and get buried or hidden in campus silos. Institutional leaders must not only recognize potential barriers and understand inherent capabilities in the context of stakeholder needs but also need to exhibit the aptitude to appropriately choose between employing a consensus vs. direct decision-making leadership style when attempting to move from willingness to readiness and beyond (McGrath et al., 2019). They should also realize that strategic planning, solving complex problems, and fostering broad change with regard to organizational culture require consensus building, which may be slow and incremental. This can pose a major hinderance to entrepreneurial thinking at the highest levels, leading to unintended consequences for navigating challenges and traditions and sustaining the momentum of cultural change and progress (Shattock, 2018). In contrast, a direct decision-making approach is necessary for agility and adaptation and for responding to landscape and emergency disruptions, which require critical, rapid, and innovative actions.

Successful institutional transition and transformation depend on effective leadership, which requires strategic identification, engagement, and leveraging of stakeholder talent and capabilities while guiding visionary alignment and progress and ensuring necessary accountability. When facilitating institutional transitions, regardless of whether the entity is at the stage of willingness or readiness, leaders should be open to varying perspectives and remain focused on building a trust-driven environment to effectively engage constituents in reducing barriers and driving progress (Drew, 2010; Fernandez and Shaw, 2020). A perceived static leadership or management style would likely be contraindicated for transforming institutions that are aiming to sustain ecosystems that are inherently both structurally and functionally dynamic.

Leadership is interrelated with institutional vision, as a leader’s failure to establish or adopt a compelling aspirational vision could result in a persistent state of “willingness” stagnation, i.e., institutional inertia or inability to move beyond their current state towards readiness or an inability to engage forward-thinking acts to ensure progress towards a specified vision. It is critical for those leading a transformation and/or transition to communicate and optimize the operational infrastructure and a mission-aligned culture to facilitate an institutional strategic vision and direction for success (Fernandez and Shaw, 2020; Montgomery, 2020). Mobilizing constituents to take action while setting or establishing an ecosystem culture that will serve the mission, vision, and aspirational direction via a creative and evolving strategy is critical for transformation and progress. The broader process of transition must be viewed as a journey that is based on a keen awareness of the deep issues related to growth, success, and progress. It may be important to address certain internal contradictions and cultural traditions, which may not be compatible with socioeconomic/political sustainability (progress). In both willing and ready institutions, such contradictions are likely to have been reinforced over decades due to ill-conceived meritocracies and incentive systems/processes.

Institutional leaders should be open to new perspectives and ideas and understand the costs and other factors underlying the strategic actions, stakeholder behaviors, and operations being executed in an existing culture. They should also acknowledge and value inherent strengths and capabilities, understand emerging threats and disruptions as well as the consequences of failing to adapt, and develop a culture of trust, accountability, open communication, and transparency. According to Erlyani and Suhariadi (2021) who conducted a review of literature on readiness for organizational change, trust in leaders on the part of faculty and staff is critical to successfully implementing change in academia. Thus, leaders must work to build and sustain trust (Kezar and Eckel, 2002a). Indeed, upon recognizing existing gaps in organizational capacity, leaders must demonstrate a willingness to seek external resources, capabilities, and technologies that can be modified, adopted, or integrated directly to be effectively used in a local context to achieve and/or accelerate articulated institutional goals/objectives and transformation.

3.3 Culture

Any effective leadership, especially one that embraces change, can benefit from understanding the impact of culture and cultural frameworks on their intended efforts (Kezar and Eckel, 2002b; Naidoo, 2013; Phillips and Snodgrass, 2022; Tierney and Lanford, 2018). An institution’s culture impacts its functioning regardless of whether the culture has been intentionally recognized and cultivated or exists passively. Culture arises from the interactions that occur between individuals in a community and can be reified through traditions or socialization. As formally defined by Morris et al. (2015), culture is “a loosely integrated system of ideas, practices, and social institutions that enable coordination of behavior in a population.” Culture can exist in distinct forms at multiple levels in the case of a large institution, such as at the department, college, or administrative-unit level as well as at the level of the interactions that occur between distinct units or levels. There can be distinctions between the perceived culture and cultural norms and those experienced by the members of the community. High-functioning institutions should continuously assess where they stand, what changes or evolved practices they need to implement, and how they can obtain appropriate and constructive feedback as well as establish benchmarks to promote progress toward their intended goals and outcomes.

It is likely that certain steps need to be taken to avoid getting caught in the malaise or inertia associated with trying to please or fulfill the agendas of individual stakeholders and potentially losing sight of the broader institutional mission/purpose. It is vital for progressive institutions to develop critical and adequate infrastructure and operational resilience to keep them from getting stuck in reverberating negative feedback and to help their communities mitigate fear and embrace strategic risks that will enable progress toward the proposed desired change by allowing them to understand the motivations behind the change. Indeed, in a meta-analysis of change aversion studies, Hubbart (2023) identified a critical role for leaders in mitigating change aversion through cultivating openness, adaptability, and appropriate acceptance of risks in their ecosystems. Thus, institutions can promote change, address risks head on, and optimize functionality to sustain the aspects that work well in their current ecosystem. When formulating strategies for change, it is crucial to understand the trends, pressures, and priorities of the external community and the role of the university in providing potential solutions for workforce development and sociopolitical, business, and economic policies as well as other institutional and educational outcomes.

To be successful and effectively agile, organizations must first address cultural issues and shun the need for sole or undue control by leadership in an effort to overcome the general malaise associated with building trust (Drew, 2010; Naidoo, 2013). Operating in a constant state of urgency can jeopardize relationships, compromise the delivery of quality service, limit clarity and foresight as well as the recognition of consequences, and leave little capacity for learning and strategic thinking. Therefore, it is important to prioritize people over processes and meaningfully engage stakeholders to overcome resistance, gain diverse perspectives, and adapt to shifting ecosystem trends. It can be highly beneficial to build change-tolerant or change-resilient cultures as a way of embracing risks and adapting to new strategies that will guide organizational change and accelerate transformation (e.g., Hubbart, 2023).

3.4 Ecosystem stewardship

Leadership that seeks to facilitate change can benefit from operating through a framework of stewardship. Traditional frameworks, including those that may indicate a willingness to change, often function through the lenses of gatekeeping (Montgomery, 2021). Gatekeeping in leadership can manifest through a strict adherence to metrics that are aligned with status quo-related pressures and prestige seeking. In contrast, leaders who function as ecosystem stewards may operate through growth-promoting frameworks, such as a Groundskeeping framework rather than more prevalent gatekeeping approaches (Montgomery, 2021). Those who opt for the Groundskeeping method seek to identify the gaps, deficiencies, and necessary adaptations in an ecosystem and facilitate the required efforts to support change (e.g., Montgomery and Black, 2025; Packard et al., 2025). This approach will involve not defaulting to only plug-and-play methods of evidence-based replication practices that are typical when approaching leadership traditionally or through gatekeeping-associated practices, but, instead, is evidenced by leaders seeking to employ novel practices or evidence-based innovations, where they may look to aspirational institutions but specifically seek learnings, practices, and processes that can be adopted and/or adapted locally (Whittaker and Montgomery, 2022). To support institutions in their transition to becoming ready for change, both leaders and middle managers should be self-affirmed and institutionally supported to function as ecosystem stewards and facilitators.

3.5 Fiscal standing and economic position

The fiscal risk tolerance of institutions often differs for those willing to change compared to those ready for change. Institutions that are anchored in either resistance to change or in a willingness for change often operate from a place of necessity and tend to be risk averse. Facilitating institutional transformation requires a clear understanding of the mission and purpose of the university as well as its operational complexities and diverse revenue streams (Ecton and Dziesinski, 2021; van den Berg, 2021). Hence, leaders in ready-to-change institutions must be bold when challenging an institution’s business model and engage in the decision making necessary for altering internal processes and operational traditions to achieve economic positions that will ensure years of fiscal and managerial stability, risk mitigation, and growth (Phillips and Snodgrass, 2022). Such progressive leadership moves in terms of finances can show up in an institution’s financial history as a definitive and significant change after long periods of financial decisions that maintained the status quo (Ecton and Dziesinski, 2021). Building a community involving trust and collective action around fiscal accountability and transparency is critical for thoughtful and proactive resource allocation and impactful investments. Moreover, such decisions should support the overcoming of protracted challenges via rapid adaptation to shifting market trends and the recognition of unique opportunities as well as prevent spending on ill-conceived business plans not intended to serve the interests of stakeholders broadly.

The economic standing of an institution is dependent on many variables, including external relations, societal impacts, and sustainability, and can be a major contributor to operational complexities. Thus, the economic positions of institutions can be impacted by both their internal and external networks (Tamtik, 2009). The ability to continuously assess the comprehensive financial health of an organization and effectively operate in the context of market, regulatory, and stakeholder pressures as well as other economic forces is crucial when it comes to strategies that are intended to align growth and transformation with cost management and sustainable investment plans. Besides understanding revenue, expenditures, and stakeholder and market needs, both willing and ready institutions must have clarity regarding areas that need improvement and the potential best practices that could be adopted to enhance operational efficiencies and profitability—ready institutions then move from awareness to action. Establishing an institution’s value proposition and aligning its strategic goals with its fiscal capacity and operational efficiencies will be essential considerations for transformational decision making, organizational progress, sustainability, and profitability as organizations move from willingness to being ready for change.

3.6 Policies

The development and implementation of policies in higher education settings can be an extremely slow and often an incremental process, which contributes to the maintenance of the status quo or to incremental change (Mintrom and Norman, 2013). To support required change, institutional policies should ensure necessary accountability (while promoting creativity), freedom to generate ideas, and continuous learning as a part of an ecosystem that requires support for growth and risk taking (Mokher et al., 2019). Fullan (2020) also highlights the importance of promoting learning for change in that it is important for leaders to “create new settings conducive to learning and sharing that learning” (p. 93). Promoting a learning culture that facilitates change can be challenging in the higher education domain, which can be considerably traditional and status quo-oriented in its operational practices despite commitments to pursuing cutting-edge work in the research and teaching realms. Keeping tradition in perspective represents a way to shift from policies that are primarily focused on operations to those that are regularly updated to adjust to and, ideally, to anticipate the change and growth that are in alignment with the defined vision. It is also important to acknowledge and respond to the given context as institutions strive to promote maintaining elements that work and moving forward (beyond stagnation) to try new things and approaches.

Formulating effective approaches to ensure that local policies promote agility rather than stagnation requires regular ecosystem-wide policy assessment and efforts to ensure that policies are supporting the stated goals, including those intended to facilitate change. Assessing and cataloging the policy landscape can help leaders retain policies that support the stated goals and recognize when and where other policies need to be adopted or new policies need to be established to support the realization of goals and change (Harvey and Kosman, 2013; Montgomery and Black, 2025; Phillips and Snodgrass, 2022).

3.7 Human resources

Infrastructure quality and configurations can impact the quality of the personnel that is attracted to an institution as well as the efficiency of its operational processes. More traditional institutions that exhibit a willingness to change but are not ready for the same often have outdated hiring and promotion practices and are usually averse to conflict even if it is productive or constructive (Small, 2008; Veles et al., 2023). Institutions can regulate their qualitative academic and research offerings and, thereby, their potential to attract competitive funding resources, and personnel. In organizations that are ready for change, this affords agility and responsiveness to stakeholder and community needs. An institution’s fiscal and economic standing, academic and technical capabilities, and past performance will also be major variables for attracting highly qualified personnel. The evolved or aspirational environment of ready-to-change institutions must tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty and, therefore, must be open to experimentation, creativity, and innovation while being tolerant of failures—all of which will impact hiring and staff support structures in human resource practices. Hence, institutions are required to leverage the collective talents, skills, and capabilities of both internal and external stakeholders to efficiently address complex problems, capitalize on opportunities, and proactively plan for the future.

3.8 Incentives

Conventional academic incentives primarily focus on rewarding individual contributions and success, which, depending on the institution type, generally include peer-reviewed publications and grant funding, teaching excellence and awards, and prestigious service opportunities, such as serving on the editorial boards of highly ranked disciplinary journals, being invited as a reviewer or panel member by funding agencies, and participating in some disciplinary society engagement. Even when leaders and institutions purport a commitment to interdisciplinary or collaborative efforts, the same individuals may try to parse individual contributions and proffer individual incentives or rewards for them (Klein and Falk-Krzesinski, 2017; Whittaker and Montgomery, 2022). Realizing a need for change and leaning into readiness for change requires different modes of distributing incentives at the individual and collective levels. As change requires revised or new modes of thinking and functioning that will have some degree of risk, incentive structures in ready-for-change organizations accordingly will require the revision of the existing incentive models or, simply, the development and use of new models. Several models to address this in interdisciplinary research have been proposed (Boone et al., 2020; McLeish and Strang, 2016). Such change-tolerant incentives will help identify collaborative and/or collective action and incentive structures that recognize and reward effort or performance and learning instead of only outcomes, especially when those outcomes are strongly associated with the pursuit of prestige.

3.9 Institutional context

The factors that impact the transition of institutions from being willing to change to being ready for change may impact distinct sectors of the higher education landscape in different ways. In addition, individual institutions, particularly large and complex institutions, may have varied ecosystems internally where some units are resistant to change, others may be willing to change, and others still are ready for change. Such a varied landscape can provide significant challenges to progress for an institution as a whole but may also provide opportunities for intra-institutional learning when leaders work to position those in a state of readiness to influence those resistant to or only willing to change. The systems designed to catalyze change and the inherent multi-sector dynamics within institutions must be clearly understood to build functional strategies for progress.

Many, if not most, institutions have specific traditions, various stakeholders, and dedicated alumni that can also create challenges in relation to innovation and change. Indeed, institutions may be rife with bureaucratic traditions that give the impression that the leaders, faculty, and staff are constantly busy, but many of the associated unevaluated practices and traditions do not accomplish much in terms of overall organizational progress. The portrayal of busyness can result in everyone seeming productive, as if they are contributing in useful ways, but this is not necessarily the reality. Such a state can play into a paradox of each individual being part of a team, while the policies and incentives that are in place remain more individualistic. It is vital for ready-to-change or aspirational organizations to be aware of their practices, traditions, and policies and cultivate the ability to adapt to changing circumstances while staying true to their mission, goals, and values. Developing or engendering such inherent agility is of utmost significance in the current climate of disruptions in the higher education ecosystem. Part of future-proofing institutions must envision a resilient future state based on inherent capacities and ability to effectively navigate multi-sector dynamics such that contingencies become routine components of strategy development and risk mitigation considerations. Environmental landscape assessment can help in this regard by identifying which practices are beneficial for driving institutions toward necessary change (e.g., Montgomery and Black, 2025).

Some other factors can vary among different types of institutions, including teaching-focused entities compared to research-focused ones, historically or predominantly white institutions (PWIs) compared to those that have traditionally catered to minoritized individuals, such as historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) or Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs). HBCUs, for instance, have long been documented as being underfunded and under-resourced, which includes endowment values, relative to PWIs (Sav, 2010; Danner, 2020; Alexander, 2024). The impacts of these distinctions in terms of financial support, access to resources, and other critical factors may influence certain aspects of institutional readiness. However, even those institutions that are supported by large endowments or are otherwise well financed may choose to adhere to traditional operational cultures and models and face barriers to transformation. This resistance to change can arise due to cultural inertia, external pressures, or other factors.

4 Conclusion: institutional readiness across the higher education ecosystem

A critical requirement for institutions to become ready for change instead of being only willing to change is for their leaders to develop creative mechanisms to balance and navigate both the internal and the external pressures faced by their institutions regardless of their state of willingness or readiness. Being keenly aware of the trends shaping society and uncovering potential opportunities in response is a common way of engendering change. Amid the current global geopolitical tensions, economic shifts, and technological advancements, institutions must be prepared, i.e., be willing and ready, to rise as a collective driven to lead and to serve as resilient examples (e.g., Saul and Blinder, 2025; Speri, 2025; Weissman, 2025). Ready institutions must develop and/or adopt systems for self-reflection or evaluation within their ecosystems to assess the dynamics of their internal functional processes as well as to position themselves to drive the corresponding societal impacts reflected in the local/regional sociocultural, economic, or wealth-building activities, policies, workforce, and human capital development. The ability to do so is dependent on institutions’ internal capabilities and resources as well as external factors.

We recommend that key actions critical to organizations that are ready for change across the higher education ecosystem are as follows: (1) regular communication of organizational vision by leaders to support broad clarity and buy-in; (2) periodic cultural surveys to understand perceived versus lived organizational culture in order to promote readiness for change rather than cultural inertia that can lead to willingness stagnation; (3) a landscape analysis of current practices and policies, including those related to incentives, to determine where standing policies may support change or where new or evolved policies are needed to support readiness for change; and, (4) establishing fiscal contingencies and a critical mass of qualified personnel to support developing the flexibility to navigate the complexities associated with the relevant functions, policies, culture, and governance.

Current global political, social, and cultural factors continue to influence higher education practices, with some institutions’ ability to change being significantly impacted. It will take a timely recognition of these shared challenges, rapid adoption and mobilization of capabilities, and strategic collaborations to find relevant sustainable solutions in an increasingly chaotic and dynamic world. With the ever-evolving academic landscape, it is crucial for institutions to recognize and accept that the responsibilities of administrators and leaders must transcend traditional roles and expectations. Being adept at building strong, aspirational, and collaborative relationships will be paramount for catalyzing and reinforcing transformative cultural dynamism and driving positive, sustainable ecosystem change. Cultivating an ecosystem based on strong, reliable operational functionalities can yield competitive advantages and increased access to opportunities.

Ultimately, to effectively accomplish the change and innovation that institutions purport to pursue, institutions must employ self-reflection and strategic thinking to go from being oriented toward survival to being able to assess their needs and address competing priorities. Such efforts will require the recruitment and support of effective leaders to spearhead a relentless pursuit of shared goals by leveraging collective talents and capabilities while creatively utilizing all available resources. They will also require pivoting from the current and prevalent institutional practices of being in a constant state of reaction to persistent ecosystem change and moving toward practices and operations that are founded in confidence and that function proactively to help keep the institution one step ahead. To sustain progress, growth, and ongoing success, institutional leaders should be able to empower teams to anticipate and respond to change and challenges and to capitalize on emerging opportunities while maintaining their purpose and values-driven direction even in the midst of chaos and uncertainty.

Author contributions

JW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BM: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

JW was employed by Global Advisors and Analysts, LLC.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexander, R. (2024). Beyond affirmative action: HBCUs and the time for equitable funding. Available online at: http://www.cpreview.org/articles/2024/9/beyond-affirmative-action-hbcus-and-the-time-for-equitable-funding?rq=river%20alexander (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Boone, C. G., Pickett, S. T., Bammer, G., Bawa, K., Dunne, J. A., Gordon, I. J., et al. (2020). Preparing interdisciplinary leadership for a sustainable future. Sustain. Sci. 15, 1723–1733. doi: 10.1007/s11625-020-00823-9

Caldwell, C., Al Asmi, K., AlBusaidi, Z., and Esmaail, R. (2023). People, processes, systems, and leadership—keys to organizational performance. J. Values-Based Lead. 17:1504. doi: 10.22543/1948-0733.1504

Cheruvelil, K. S., and Montgomery, B. L. (2019). “Professional development of women leaders” in Women leading change in academia: Breaking the glass ceiling, cliff, and slipper. eds. C. M. Rennison and A. Bonomi (San Diego, CA: Cognella Academic Publishing), 235–254.

Danner, P. A. (2020). Disparities in enrollment, funding, and advanced degree patterns between historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and predominantly white institutions (PWIs): A replication study. Nashville, TN: Tennessee State University.

Drew, G. (2010). Issues and challenges in higher education leadership: engaging for change. Aust. Educ. Res. 37, 57–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03216930

Dryden-Palmer, K. D., Parshuram, C. S., and Berta, W. B. (2020). Context, complexity and process in the implementation of evidence-based innovation: a realist informed review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20:81. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4935-y

Ecton, W. G., and Dziesinski, A. B. (2021). Using punctuated equilibrium to understand patterns of institutional budget change in higher education. J. High. Educ. 93, 424–451. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2021.1985884

Erlyani, N., and Suhariadi, F. (2021). Literature review: readiness to change at the university. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 9, 464–469. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2021.6203

Fernandez, A., and Shaw, G. (2020). Leadership in higher education in an era of new adaptive challenges. INTED2020 proceedings, pp. 61–65.

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Nowell, B., and Yang, H. (2007). Putting the system back into systems change: a framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am. J. Community Psychol. 39, 197–215. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0

Hanna, S. (2017). Leadership as a driver for organizational change. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 1, 74–82. doi: 10.21272/bel.2017.1-09

Harvey, M., and Kosman, B. (2013). A model for higher education policy review: the case study of an assessment policy. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 36, 88–98. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2013.861051

Hubbart, J. A. (2023). Organizational change: the challenge of change aversion. Adm. Sci. 13:162. doi: 10.3390/admsci13070162

Kezar, A., and Eckel, P. D. (2002a). Examining the institutional transformation process: the importance of sensemaking, interrelated strategies, and balance. Res. High. Educ. 43, 295–328. doi: 10.1023/A:1014889001242

Kezar, A., and Eckel, P. D. (2002b). The effect of institutional culture on change strategies in higher education: universal principles or culturally responsive concepts? J. High. Educ. 73, 435–460. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2002.0038

Klein, J. T., and Falk-Krzesinski, H. J. (2017). Interdisciplinary and collaborative work: framing promotion and tenure practices and policies. Res. Policy 46, 1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.03.001

Knowles, J., Hunsaker, B. T., and Hughes, M. (2023). The role of culture in enabling change. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. Available online at: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-role-of-culture-in-enabling-change/#article-authors

Laroche, L., and Yang, C. (2014). Danger and opportunity: Bridging cultural diversity for competitive advantage. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: concept, method and reality in social science; equilibrium and social change. Hum. Relat. 1, 5–41. doi: 10.1177/001872674700100103

Lombardi, J. V., Johns, M. M. E., Rouse, W. B., and Craig, D. D. (2020). Complexities of higher education. The Bridge (Pittsburgh, PA.) 50, 70–72. Available at: https://cepcuyo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-Bridge-Winter-2020-1.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2025).

McGrath, C., Roxå, T., and Bolander Laksov, K. (2019). Change in a culture of collegiality and consensus-seeking: a double-edged sword. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 1001–1014. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1603203

McLeish, T., and Strang, V. (2016). Evaluating interdisciplinary research: the elephant in the peer-reviewers’ room. Palgrave Commun. 2:16055. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2016.55

Meyer, C. B., and Stensaker, I. G. (2006). Developing capacity for change. J. Change Manag. 6, 217–231. doi: 10.1080/14697010600693731

Mintrom, M., and Norman, P. (2013). “Policy entrepreneurship” in Public policy: The essential readings. eds. S. Z. Theodoulou and M. A. Cahn (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall), 164–173.

Mokher, C. G., Spencer, H., Park, T. J., and Hu, S. (2019). Exploring institutional change in the context of a statewide developmental education reform in Florida. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 44, 377–390. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2019.1610672

Montgomery, B. L. (2018). Pathways to transformation: institutional innovation for promoting progressive mentoring and advancement in higher education. Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for leadership excellence and ADVANCE working paper series. 1, pp. 10–18. Available online at: https://www.purdue.edu/butler/documents/3-Pathways-to-Transformation.pdf (Accessed December 12, 2024).

Montgomery, B. L. (2020). Academic leadership: gatekeeping or groundskeeping? J. Values-Based Leadership 13:16. doi: 10.22543/0733.132.1316

Montgomery, B. L., and Black, S. J. (2025). Ecosystem assessment and translating a groundskeeping framework into practice for promoting systemic change in higher education. Front. Educ. 10:1472703. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1472703

Montgomery, B. L., and Whittaker, J. A. (2022). The roots of change: cultivating equity and change across generations from healthy roots. Plant Cell 34, 2588–2593. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac121

Morris, M. W., Chiu, C. Y., and Liu, Z. (2015). Polycultural psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 631–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015001

Mugglestone, K., Dancy, K., and Voight, M. (2019) Opportunity lost: net price and equity at public flagship institutions. Available online at: https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/uploads_docs_pubs_ihep_flagship_afford_report_final.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Naidoo, D. (2013). Reconciling organizational culture and external quality assurance in higher education. High. Educ. Manag. Policy. 24, 85–98. doi: 10.1787/hemp-24-5k3w5pdwhm6j

Packard, B. W.-L., Montgomery, B. L., and Mondisa, J.-L. (2025). Synergy as a strategy to strengthen biomedical mentoring ecosystems. Frontiers in Education. 10:1474063. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1474063

Phillips, T. J., and Snodgrass, L. L. (2022). Who’s got the power: systems, culture, and influence in higher education change leadership. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies 3, 7–27. doi: 10.52547/johepal.3.2.7

Redmond, R., Curtis, E., Noone, T., and Keenan, P. (2008). Quality in higher education: the contribution of Edward Deming’s principles. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 22, 432–441. doi: 10.1108/09513540810883168

Rieg, N. A., Gatersleben, B., and Christie, I. (2021). Organizational change management for sustainability in higher education institutions: a systematic quantitative literature review. Sustainability 13:7299. doi: 10.3390/su13137299

Saul, S., and Blinder, A. (2025) Emerging from a collective silence, universities organize to fight trump. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/27/us/trump-university-presidents.html

Sav, G. T. (2010). Funding historically black colleges and universities: progress toward equality? J. Educ. Finance 35, 295–307. doi: 10.1353/jef.0.0017

Schein, E. H. (2008). “The mechanisms of change” in Organization change: A comprehensive reader. eds. W. W. Burke, D. G. Lake, and J. W. Paine (Chichester: Wiley), 78–88.

Shattock, M. (2018). “Entrepreneurial leadership in higher education,” in Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions, eds. J. C. Shin and P. Teixeira (Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media), 1–4

Small, K. (2008). Relationships and reciprocality in student and academic services. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 30, 175–185. doi: 10.1080/13600800801938770

Speri, A. (2025). Over 150 US university presidents sign letter decrying trump administration. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/21/us-university-presidents-trump-administration

Tamtik, M. (2009). An analysis of the factors that enhance participation in European university networks – A case study of the University of Tartu, Estonia. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto.

Tierney, W. G., and Lanford, M. (2018). “Institutional culture in higher education” in Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions. eds. J. C. Shin and P. Teixeira (Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media), 1–9.

van den Berg, M. (2021) Determinants of the changing funding burden of higher education. Mt. Plains J. Bus. Technol., 22, 51–74. Available online at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/mpjbt/vol22/iss1/7.

Veles, N., Graham, C., and Ovaska, C. (2023). University professional staff roles, identities, and spaces of interaction: systematic review of literature published in 2000–2020. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 7, 127–168. doi: 10.1080/23322969.2023.2193826

Weissman, S. (2025). The resistance is here. Inside Higher Ed. Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/politics-elections/2025/04/29/resistance-here

Whittaker, J. A., and Montgomery, B. L. (2022). Advancing a cultural change agenda in higher education: issues and values related to reimagining academic leadership. Discov. Sustain. 3:10. doi: 10.1007/s43621-022-00079-6

Keywords: higher education, institutional change, institutional readiness, institutional transformation, leadership

Citation: Whittaker JA and Montgomery BL (2025) Reimagining a path from institutional willingness to readiness: ecosystem variables that promote or impede sustainable transformation in higher education. Front. Educ. 10:1571030. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1571030

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Nikita Lad, George Mason University, United StatesItahisa Pérez Pérez, University of La Laguna, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Whittaker and Montgomery. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beronda L. Montgomery, YmVyb25kYW1AZ21haWwuY29t

Joseph A. Whittaker1

Joseph A. Whittaker1 Beronda L. Montgomery

Beronda L. Montgomery