- 1Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

- 2Department of Education, Volda University College, Volda, Norway

This systematic review examines students' perceptions and outcomes of teacher feedback in elementary and lower secondary education (ages 10–16). The study explores how different feedback types and personal and relational factors influence students' achievement and their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. Following PRISMA guidelines and the PICO framework, 96 empirical studies were analyzed, focusing on feedback-related student outcomes and moderating factors. Findings indicate that high-quality, tailored, and action-oriented feedback positively affects student achievement, motivation, and engagement, while negative or vague feedback can lead to demotivation and avoidance behaviors. Students prefer direct and individualized feedback, and trust in the teacher-student relationship is crucial for effective feedback uptake. Social dynamics, gender differences, and feedback interpretation influence student outcomes, emphasizing the need for adaptive feedback strategies. The review suggests that future research should focus on finding specialities and commonalities across various groups as well as on integrating AI with human feedback systems.

1 Introduction

1.1 The purpose of this review

Formative assessment in elementary and lower secondary schools is challenging for both students and teachers. It requires processes that integrate received feedback and enhance the learning experience (Black and Wiliam, 1998; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Van der Kleij, 2022). Formative feedback is information aimed at modifying the learner's thinking or behavior to improve learning (Shute, 2008). While feedback significantly influences achievement, its effects can vary, highlighting the complexity of its optimal use (Hattie, 2009; Shute, 2008). Shute (2008) identifies various feedback types (e.g., correct answer explanations, hints), modalities (e.g., written, oral), and timings (e.g., during learning, immediately after a response). Additionally, variables like learner characteristics and task aspects interact with feedback's effectiveness. Wisniewski et al. (2020) found that high-information feedback, including self-regulation information, is most effective (d = 0.99).

Traditionally, teachers were solely responsible for providing evaluative feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Shute, 2008). However, the paradigm has shifted to recognize the social context of learning, where students actively seek, receive, and apply feedback (Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Lipnevich and Panadero, 2021; Van der Kleij, 2022). Van der Kleij (2022) advocates for a student-centered approach, giving students agency. Feedback is a dynamic interaction between teacher and student aimed at facilitating learning (Andrade, 2010; Gamlem and Munthe, 2014), but it is effective only when used.

To understand how feedback impacts learning, it is essential to study the relationships among teacher feedback, student beliefs, motivation, interpretation, and responses (Yang et al., 2021). It is still unclear what kind of teacher feedback is most beneficial and what moderating factors enhance learning. This study systematically reviews empirical research on students' perceptions and outcomes related to teacher feedback for ages 10–16.

1.2 Feedback in elementary and lower secondary school

Teacher feedback is vital but insufficient without student engagement (Van der Kleij, 2022). Understanding students' perspectives is crucial to grasp how feedback is received, interpreted, and used. This approach helps identify what types of feedback work best and why (Shute, 2008). Including students' views makes research more democratic and relevant (Fielding, 2004).

We focus on students aged 10–16, a period of significant cognitive, emotional, and social development (Eccles et al., 1993). Feedback during this transitional phase from primary to secondary school is critical for adapting to new learning environments and expectations (Black and Wiliam, 1998). Understanding students' feedback perceptions can guide effective interventions to boost learning and engagement (Wigfield and Eccles, 2000). Effective feedback usually answers three questions: Where am I going? How am I going? Where do I go next? It operates at four levels: task, process, self-regulation, and self (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Despite its potential, feedback often fails to enhance learning (Shute, 2008). Effective feedback should be part of the teaching process, be comprehensible, be actionable, and stimulate critical thinking (Andrade, 2010; Black and Wiliam, 2018; Hattie and Gan, 2011). It should align with learning objectives (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Gamlem and Munthe, 2014). However, not all feedback types are beneficial. Evaluative feedback like scores and rewards can hinder learning (Guskey and Brookhart, 2019; Kluger and DeNisi, 1996). Grades and scores can decrease crucial metacognitive strategies (Boekaerts and Corno, 2005). Volitional engagement is essential for persistence and managing self-esteem threats (Black and Wiliam, 2009; Boekaerts and Corno, 2005). Moreover, former research found that feedback effects vary among students, indicating diverse feedback needs (e.g., Shute, 2008; Lipnevich et al., 2016). Feedback interpretation and response involve psychological states and dispositions (Butler and Winne, 1995; Perrenoud, 1998). Prior knowledge, beliefs, and thought processes mediate feedback effectiveness (Smith et al., 2016). For feedback to be effective, it must be processed through the learner's unique cognitive lens.

1.3 The present study

In this study, we attempt to fill a gap in the assessment literature by systematically reviewing empirical research on feedback in the age group 10–16. This is based on the fact that most feedback research has been done on students in higher education and the need to systemize research on younger students. Furthermore, because we are particularly interested in what works for students, we have focused on student outcomes. Related to this is also an interest in what causes or influences student outcomes, which we have chosen to name moderators.

Much of the research and theory development in the formative assessment field has occurred over the past 25, and because we wanted to avoid being history-less and forgetting good research that goes back a bit in time, we chose the last 30 years as the search period. Since we started the work on this review in 2021, it includes articles dating back to December 1991. Furthermore, as we did not know how artificial intelligence would influence feedback processes and, consequently, the research related to feedback, we decided to end the review when ChatGPT launched in November 2022.

Given this point of departure, the following research questions have guided the review.

1. What student outcomes are measured in studies concerning teacher feedback?

2. What factors are assumed to moderate students' outcomes of teacher feedback?

3. Do the results of the studies indicate that some factors are more important than others in moderating students' various outcomes of teacher feedback?

2 Method

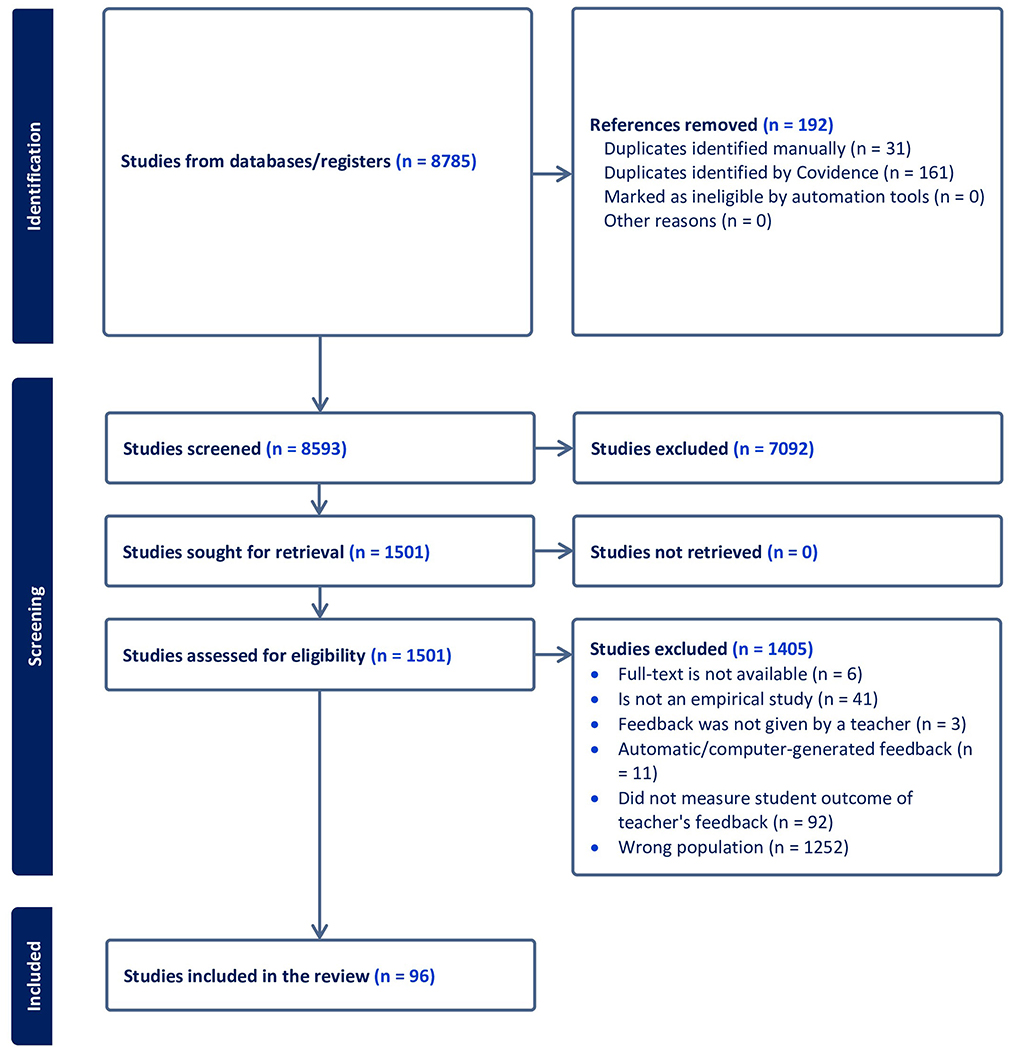

In this review, we followed the PRISMA guidelines and the PICO framework as far as applicable. This means that we followed the PRISMA guidelines as our primary framework for reporting. Additionally, we used the PICO framework to assess each included study, focusing on population, intervention/measure, type of comparison, and outcome. However, since this review goes beyond strictly defined interventions and includes observational and small-scale qualitative studies, the comparison component (C) and outcome components (O) of the PICO framework were not always applicable. The literature search was conducted in two rounds in the databases Eric, PsychINFO, Educational Research Complete, and Scopus, resulting in a total of 8,593 hits that went on to the title and abstract screening. The first search contained studies from December 1991 until December 2021. Later, an updated search was made for the period up to November 2022, which is the time when ChatGPT was made generally available.

In developing the search protocol, key areas of teacher feedback were identified and categorized. These areas included teacher feedback itself, encompassing different feedback types (e.g., achievement feedback, performance feedback) and processes in which feedback occurs (e.g., formative assessment, assessment for learning). Another key area was students' perceptions of feedback, which covered general perception terms as well as cognitive and emotional responses. Additionally, the outcomes of teacher feedback were considered, including improvements in knowledge and changes in various beliefs, changes in motivation, behavioral changes or regulation of learning, and various achievement descriptors. Lastly, possible moderating variables of teacher feedback were identified, incorporating feedback content and types, task requirements, feedback mode, feedback context, individual differences, and social relation variables. Altogether, this process resulted in 138 descriptors. In the next phase, we were supported by a librarian at the Medical Library at the University of Oslo to specify and conduct the first trial search, which we scrutinized regarding the relevance of the hits, and then a final search. Further, the search criteria required that articles (a) should relate to education, (b) be published in English, (c) be peer-reviewed, and (d) for empirical studies include data from or about students (search documentation is available in the Supplementary material).

The authors and three trained research assistants used the Covidence software for the title and abstract screening. Two blinded independent reviewers had to agree on all decisions on whether the study should be included. However, some conflicts arose due to the great diversity in both content and methodological approaches and the clarity of the abstracts. These conflicts were solved through an extra round of review and discussions that included one or both authors. Inclusion criteria were “educational context, teacher feedback, feedback given through digital media by a teacher, student outcome, student achievement (tests, performance), cognitive outcome (e.g., learning, understanding, beliefs), motivational outcome (e.g., change in goals, student engagement), relational or social outcome, judgment of feedback, students' perceptions and reactions on feedback”. Exclusion criteria were “lack of students' perspectives, empirical studies that do not include data from or on students, studies do not include student outcome, feedback was not given by a teacher, and computer-generated feedback.” The title and abstract screening resulted in 1,501 records proceeding to the full-text review.

Through the long process of title and abstract screening, we realized the need to narrow the present study's focus. This was based on the interest in producing manageable data material. Therefore, we changed the inclusion and exclusion criteria before starting the full-text review. The narrowing involved only including empirical studies and focusing only on studies that examined the age group 10–16. The last criterion emerged after recognizing that we lack systematized knowledge about this age group. The two authors and one trained research assistant conducted the full-text review. Furthermore, we used the procedures previously described to resolve conflicts. The full-text screening resulted in 100 included records. However, four more records were excluded during the extraction process because it became clear that the feedback was not given by a teacher, or the sample exceeded the defined age range (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

2.1 Extraction, coding and presentation

All key information about the studies was gathered in a spreadsheet in the extraction phase. We used the Data Analyst function in ChatGPT to extract the most significant information from each study. A PDF file of each article was uploaded to the service, after which we provided prompts to extract information. Typical prompts were “…given an overview of the study, …what study design was used, … main findings concerning feedback”. The information was then manually coded into four main outcome categories (achievement, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcome), which are based on common categories from educational psychology. In addition, we coded potential moderators or causes related to the outcome (feedback mode and type, task-related, personal factors, relational factors, and contextual factors). It should be mentioned that each main category had several subcodes to ensure consistency in coding. The cognitive category was clearly the largest because it contained almost all types of motivation, perceptions, and beliefs. The emotional category was clearly the smallest because it was reserved for more purely emotional outcomes.

It should be noted that several terms are used to represent students' academic engagement. This is because the included studies differ in descriptions, conceptualization, and grain sizes regarding the operationalization of student engagement. As a point of departure, we consider student engagement a multidimensional construct containing cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects (Fredricks, 2011; Sinatra et al., 2015). From our perspective, cognitive engagement refers to psychological investment when a student uses cognitive effort beyond the minimal requirements to understand a subject matter, use flexible problem-solving or choose a challenging task (Sinatra et al., 2015). Emotional engagement refers to students' reactions to academic activities, such as enjoyment related to tasks, that can lead to high engagement and attention (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012; Sinatra et al., 2015). Behavioral engagement refers to actions such as attendance and participation in academic activities and includes effort, persistence and overt parts of self-regulation and the use of learning strategies (Fredricks, 2011; Sinatra et al., 2015). In our presentation of the studies, we have adhered to the terminology used in the original papers. When the type of engagement is not explicitly stated, we have used the general term engagement and categorized it based on contextual information within the respective study. Additionally, we use the term “student engagement” as an overarching term in our discussion (Marks, 2000).

It should also be noted that not all the included studies had clear moderators or causes for specific outcomes. Some studies were primarily descriptive and did not define causes or outcomes. We also analyzed these studies and tried to extract key insights and conclusions that could contribute to the discussion of the current study's topics. We have nevertheless chosen to retain moderators and outcomes as the main categories in our presentation, as this has been fundamental in the thinking throughout the work with the study.

In presenting our results, we distinguish between interventions, observational studies, and small-scale qualitative studies, building on the rationale that these represent different forms of evidence. Intervention studies offer strong insights into causality, while observational studies, though weaker in establishing causality, can help identify relevant variables, correlations and trends over time (Shadish et al., 2002; Rosenberg, 2020). Qualitative studies can better understand complex phenomena and subjective experiences (Carey, 2012). Even though the quality of the studies may vary within these categories, we have treated them rather uniformly, acknowledging this approach's limitations. Finally, we have marked the studies included in the review (*) in the reference list.

3 Results

3.1 Teacher feedback and student achievement

3.1.1 Teacher feedback and student achievement in intervention studies

In total, 17 intervention studies included one or more measurements of student achievement (see Table 1). For most of these studies, the manipulation (moderator) was related to the feedback per se and with variation in form, content, or both. Further, twelve of these studies report a positive effect on student achievement, four report no effect, and one report a mixed effect. Several studies that report a positive impact emphasize the content quality of the feedback given. This might be more comprehensive or explicit information about the task, task criteria, learning goals and advice on possible strategies to enhance the learning process (Al-Darei and Ahmed, 2022; Eckes and Wilde, 2019; Ozan and Kincal, 2018; Ruiz-Primo and Furtak, 2007; Siero and van Oudenhoven, 1995). One study also included a kind of student activation as part of the feedback process (Ruiz-Primo and Furtak, 2007). This can take the form of the students having to decide on and process their feedback, either as an explicit assignment or as a task solved together with peers. Another highlighted dimension is the opportunity to discuss and elaborate on the feedback with the teacher (Mikume and Oyoo, 2010), which can scaffold the students' understanding of both the feedback and the requirements of the learning task.

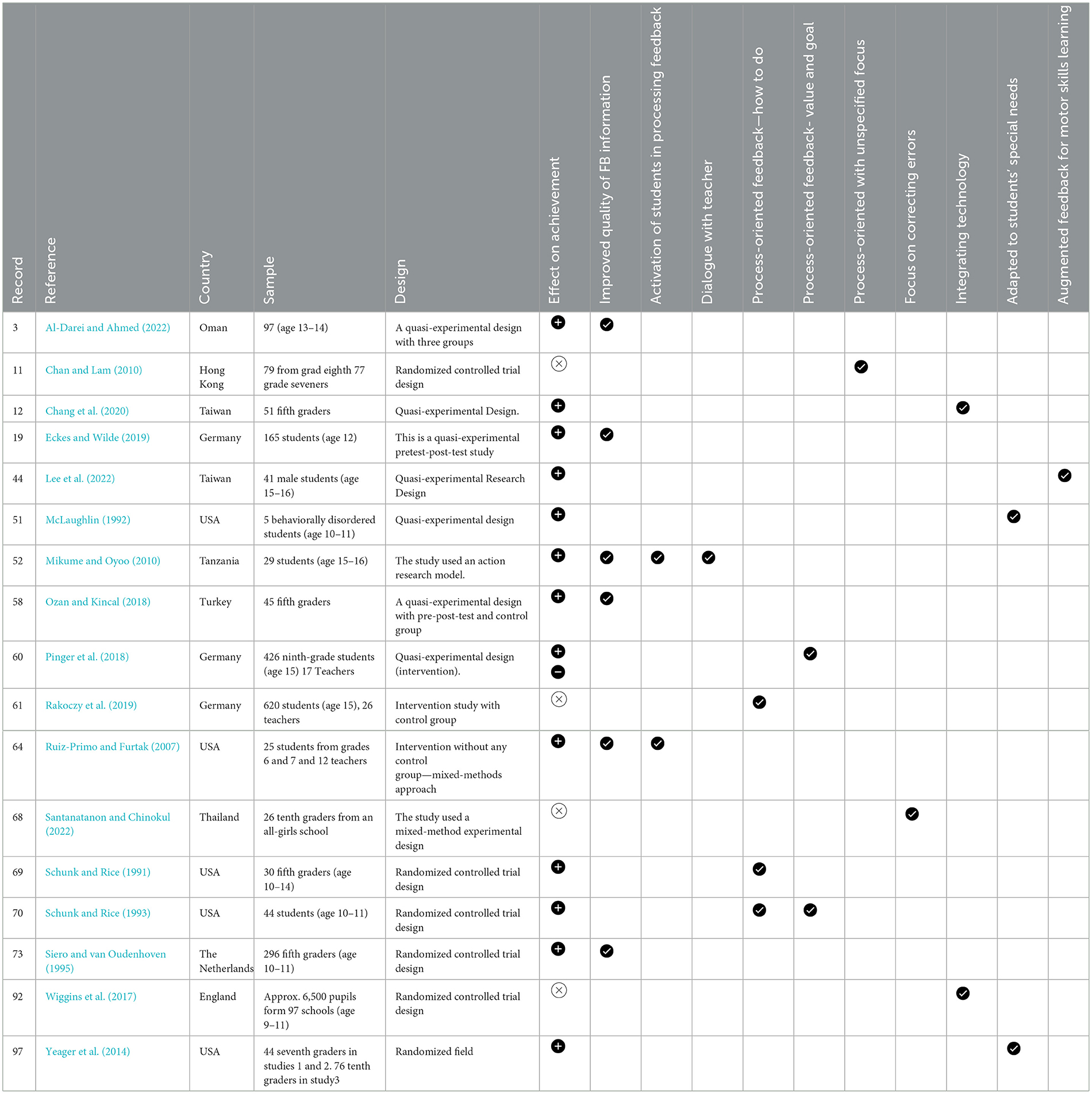

Table 1. Overview of the included invention studies that relate teacher feedback with student achievement.

Several studies emphasize process-oriented feedback, but the findings regarding such feedback's influence on achievement are inconsistent. Process-oriented feedback with a clear message about strategies or how or where to go next is positively associated with achievement (Schunk and Rice, 1991, 1993). In addition, process-oriented feedback highlighting the utility of strategy use and process goals appears to influence achievement positively (Pinger et al., 2018; Schunk and Rice, 1993). However, some studies that emphasize process-oriented feedback do not find such effects. In a study where students received feedback encouraging them to make effort and self-improvement (Chan and Lam, 2010), a positive effect was seen on students' motivation and control beliefs but not on achievement. In another study made in the context of a mathematics class, the teachers did almost all the measures recommended by the assessment literature; the feedback was individualized, weaknesses and points of improvement were identified, recommendations on strategies were given, and the learning goals were highlighted (Rakoczy et al., 2019). Still, they only gained an effect on motivational variables.

A discussion related to corrective feedback is about balancing pointing out errors and recommending how to avoid such mistakes in future work. In one study conducted in the context of English language learning, the students received detailed written grammar feedback in the form of error codes and corrected sentences, but the researchers could not find any improvement in students' achievement despite increased student engagement (Santanatanon and Chinokul, 2022).

Two of the included studies explored new technology in the process of teacher feedback. In one study conducted in the context of a virtual reality design (in natural science), students who took part in a virtual reality design activity incorporating a peer assessment learning approach showed significantly better achievements in natural science than those using a conventional VR design system (Chang et al., 2020). The conventional VR design group received teacher-centered feedback to guide students in improving their VR projects and achieving better learning outcomes. In another study, an electronic handheld device that allowed teachers and pupils to provide immediate feedback during lessons was tested in 49 primary schools across several subjects (Wiggins et al., 2017). Even though both students and teachers had largely positive experiences with the system, there were no improvements in mathematics or reading performance compared to the control schools.

Two of the studies examined the effect of teacher feedback on students with learning challenges. One study on behaviorally disordered children found that positive written comments tailored to their performance and effort during reading tasks positively affected their reading accuracy in the short and long term (McLaughlin, 1992). Another study examined adapted feedback to students who had low trust in school and teachers (Yeager et al., 2014). The form of feedback they gave, named “wise feedback”, reflected criticism paired with the teacher's high standards and belief in the student's potential to meet those standards. The students who received the “wise feedback” improved their performance on essay writing and revising as well as their general academic outcome compared to the control group. Finally, one study examined teacher feedback in a vocational setting. This study found that augmented teacher feedback combined with self-estimation of errors (enforced metacognitive reflection) improved students' motor skill learning and the quality of their final welding product (Lee et al., 2022).

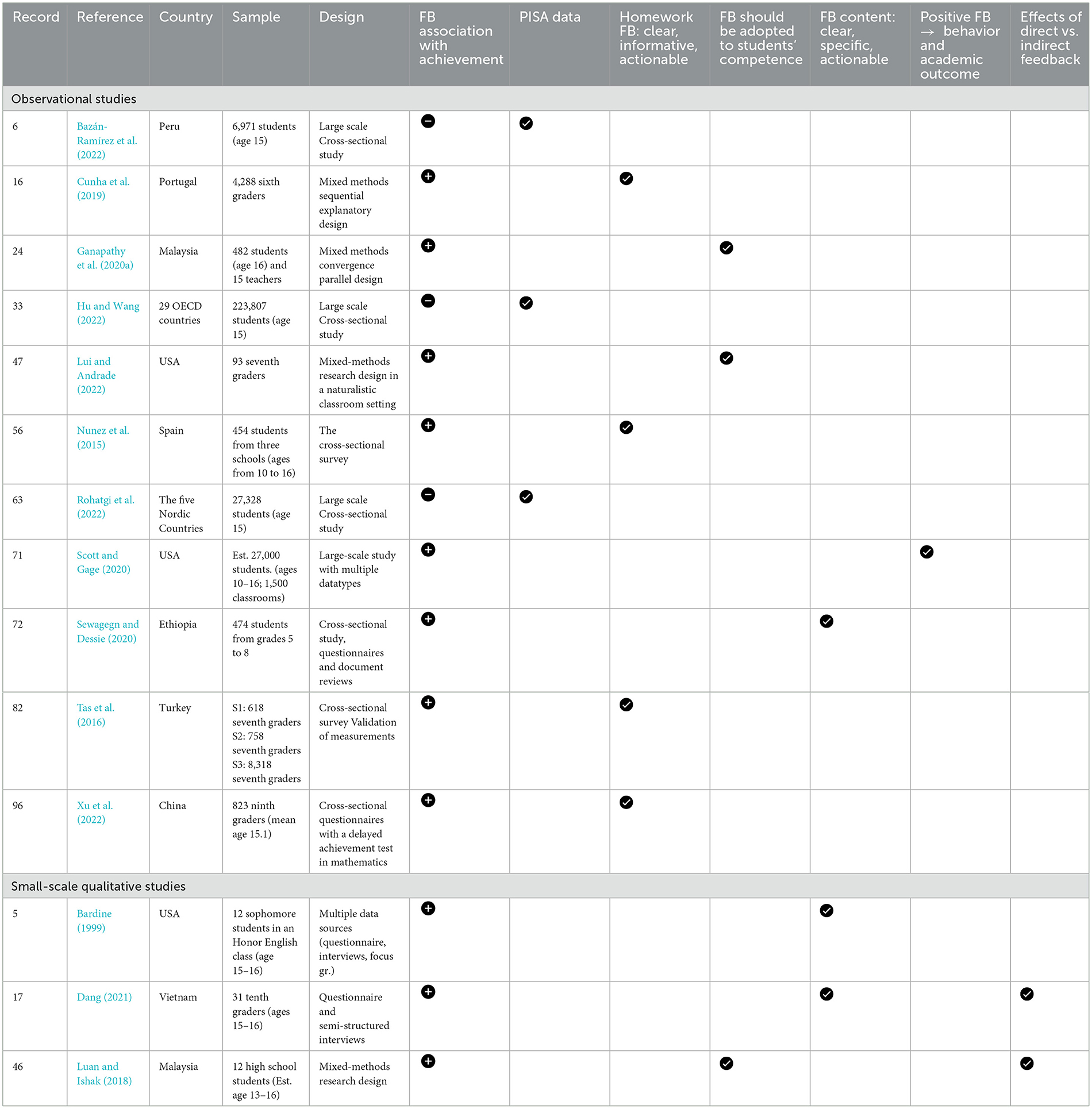

3.1.2 Teacher feedback and student achievement in observational studies

Eleven studies used observational designs to examine teachers' feedback's relation to student achievement (see Table 2). Three of these studies were based on secondary analyzes of PISA data1 (Cunha et al., 2019; Hu and Wang, 2022; Rohatgi et al., 2022) on 258,196 students from more than 30 countries. Furthermore, these studies consistently found a negative relationship between the teacher feedback reported by students and their achievement in science on the PISA 2015 assessment and reading on the PISA 2018 assessment. This negative association can probably be explained by the PISA items' response scale asking how often the student receives various forms of teacher feedback and that students with lower competence receive feedback more frequently than high-achieving students (Rohatgi et al., 2022).

Table 2. Overview of the included observational and small-scale studies that relate teacher feedback with student achievement.

Four studies explore teacher feedback related to homework, and their findings are pretty consistent (Cunha et al., 2019; Nunez et al., 2015; Tas et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2022). The more informative, accurate, meaningful, timely, and action-oriented the feedback is, the stronger associations are found with achievement in math (Cunha et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022), science (Tas et al., 2016) and a collection of several subjects (Nunez et al., 2015). It should, however, be noted that several of these studies highlight student engagement as a mediating factor between feedback and achievement. If the homework feedback is clear and easily transferable into action, it supports students in engaging in the given tasks and assignments, which, in the next step, boosts their learning and performance.

However, two studies indicate that the clarity of feedback messages might be challenging. In one study where a determined system of written correcting feedback was implemented in English second language classes, most students improved their writing skills and motivation (Ganapathy et al., 2020a). However, a challenge was that some students did not always understand the feedback correctly; consequently, their performance suffered. Another study (Lui and Andrade, 2022) found that students with higher levels of achievement tended to make more constructive decisions about using the feedback they received. This included plans to reread feedback, review requirements, and make revisions, reflecting their engagement with the feedback process. These findings underscore that the perceived clarity of a feedback message can vary depending on students' individual differences, emphasizing the importance of adapting the feedback to each student's competence level to ensure it becomes meaningful and has an impact.

Finally, is there a balancing point regarding how comprehensive the feedback must be to affect students' learning and achievement? The answer, of course, would depend on many factors, such as the intention of the feedback, how the feedback is orchestrated, in which context, the mental state of the learner, etc. Two studies illustrate this complexity. In a descriptive study (Sewagegn and Dessie, 2020), the students reported that teachers often provided judgemental feedback (e.g., “excellent,” “very good”) or grades, which they found less effective in addressing specific learning gaps or guiding improvement. The feedback they found effective in improving their self-reported achievement was clear, specific, and constructive, highlighting learning gaps and containing actionable steps for improvement, which aligns with the other findings of this review. However, in another large-scale study, where the first 15 min of the lessons were observed in ~1,500 classrooms, they found that an instructional practice of giving students positive feedback and an opportunity to respond significantly predicted school-wide outcomes (Scott and Gage, 2020). Higher rates of positive teacher feedback were associated with lower school-wide suspension rates and higher percentages of students scoring proficient or distinguished on the state academic assessments in math and reading. This association was stronger among the elementary students than secondary students. Consequently, the researchers suggest that early and frequent positive reinforcement can have long-lasting preventive effects on behavior and academic success.

3.1.3 Teacher feedback and student achievement in small-scale studies

Only three small-scale studies explored the relationship between teacher feedback and achievement (see Table 2). One study examined teachers' written feedback on students writing and found that praise could be good for their motivation, but more comprehensive feedback was needed to improve their performance (Bardine, 1999). Valuable feedback should contain constructive comments that can help students understand their mistakes and areas for improvement and help them see writing as an iterative process. The study found that teachers' feedback directly influences achievement when it is clear, actionable, and aligned with opportunities for revision.

Another study that also focused on writing found that teacher feedback played a critical role in guiding students through the discovery, correction, and rewriting processes (Dang, 2021). The students reported that teacher feedback helped them improve their grammatical accuracy and link ideas logically within their writing. However, some students indicated that over-reliance on teacher feedback could reduce independent critical thinking.

In the last study, direct vs. indirect written corrective feedback was explored in a class of English second language learners (Luan and Ishak, 2018). The researchers concluded that a blended approach with direct (e.g., marking errors and providing the correct response) and indirect (e.g., just marking the error with code without giving the correct response) feedback was the best option for improving students' writing achievement. They found that direct feedback helped students improve their revision accuracy, especially for low-proficiency students. On the other hand, the indirect feedback encouraged the students to actively engage in the feedback by cognitive processing as they worked to identify and correct errors themselves.

3.1.4 Brief summary of the findings concerning feedback and achievement

Altogether, most studies indicate that the content and quality of teacher feedback are the most important predictors of student achievement. Feedback should be tailored, informative, accurate, timely, and action-oriented. Praise and general encouragement can have a positive effect on student motivation but appear to have less direct impact on achievement. Corrective feedback should be balanced with offering guidance for improvement. For underachieving students, moderate expectations from the teacher about what they can achieve may affect both motivation and achievement.

3.2 Teacher feedback and cognitive outcome

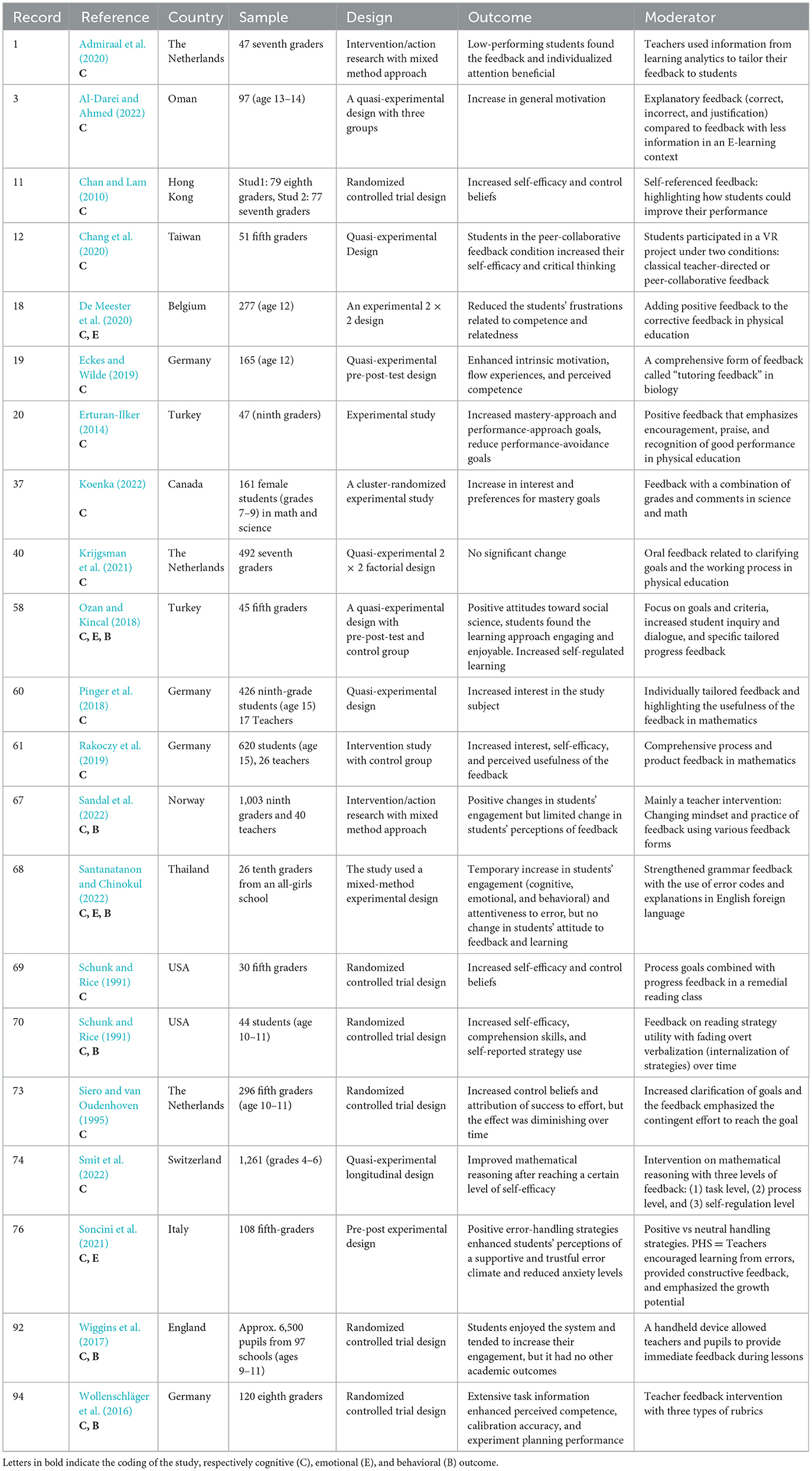

3.2.1 Teacher feedback and cognitive outcome in intervention studies

Twenty-one intervention studies examined how teacher feedback is related to various cognitive outcomes (see Table 3). Moreover, motivation, in some form or another, was the most reported outcome (18 studies). Three studies were theoretically grounded in self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2017) and with concepts such as intrinsic motivation, competence, and relatedness as outcomes (De Meester et al., 2020; Eckes and Wilde, 2019; Krijgsman et al., 2021). One study in physical education found that adding positive feedback to the corrective feedback reduced the students' frustrations related to competence and relatedness (De Meester et al., 2020). This was particularly prominent among students at low achievement levels. Conversely, another study in physical education found that oral feedback related to clarifying goals and the working process did not change students' need satisfaction (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) (Krijgsman et al., 2021). Nevertheless, a study that explored a more comprehensive form of feedback called “tutoring feedback”—which included support for strategic problem-solving, error detection and correction, reflective questioning, and encouragement for independent elaboration—found that it significantly enhanced students' intrinsic motivation, flow experiences, and perceived competence in a biology class setting (Eckes and Wilde, 2019).

Table 3. Overview of the included intervention studies on students' cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcome of teacher feedback.

Several studies have identified process-oriented feedback as significant for promoting students' self-efficacy for learning and performance. In an experimental study, self-referenced feedback (which highlighted how students could improve their performance) was tested against norm-referenced feedback (which highlighted how their performance compared to others in their group) in the context of language learning (Chan and Lam, 2010). While the self-referenced feedback had a positive effect on both students' self-efficacy and their control beliefs, the norm-referenced feedback led to a reduction in self-efficacy and lower control beliefs. Another study combined various goals with different kinds of teacher feedback in remedial reading (Schunk and Rice, 1991). The students who received process goals and progress feedback demonstrated the highest self-efficacy and control beliefs. In another experiment that targeted strategic reading, the combination of feedback on strategy utility with fading overt verbalization over time (internalization of strategies) significantly improved students' self-efficacy, comprehension skills, and self-reported strategy use (Schunk and Rice, 1993). However, self-efficacy could also serve as a mediator of the relationship between feedback and another learning-related outcome. This was illustrated in a 10-week-long intervention on mathematical reasoning with three levels of feedback (task level, process level, and self-regulation level). The study revealed that the learning outcome first appeared after the students had reached a certain level of self-efficacy (Smit et al., 2022).

Several studies indicate that feedback may also positively affect students' interests and attitudes when the feedback is sufficiently comprehensive, specific enough, and perceived as valuable (Al-Darei and Ahmed, 2022; Pinger et al., 2018; Rakoczy et al., 2019; Nunez et al., 2015). For example, in a quasi-experimental study of ninth graders in mathematics that focused on providing individually tailored feedback and highlighting the usefulness of the feedback, students showed increased topic interest (Pinger et al., 2018). In a more comprehensive intervention study, where feedback was individualized, weaknesses and areas for improvement were identified, strategic recommendations were provided, and learning goals were emphasized, researchers found positive effects on students' interest, self-efficacy, and perceived usefulness (Rakoczy et al., 2019). A similar comprehensive intervention study, which emphasized explaining learning objectives and success criteria, fostering inquiry and dialogue among students, providing targeted comments on assignments, and offering individualized feedback on progress, found that students developed more favorable attitudes toward social science studies, perceiving studies as more engaging and enjoyable (Nunez et al., 2015). These studies indicate that if feedback is clear and understandable for the students and perceived as valuable for one's progress, the feedback alone (or in combination with other instructional measures) may contribute to increased engagement and interest in the subject being studied.

Although we have briefly touched on how students' goal orientation can relate to teacher feedback, several studies have looked more specifically at this. In an experimental study in math and science with lower-secondary girls, four conditions of feedback (grades, comments, grades and comments, no feedback) were tested upon various motivational outcomes (Koenka, 2022). The results revealed that intrinsic motivation increased among students who received comments only. For those students who received grades and comments, their intrinsic motivation and their preferences for mastery goals increased. However, the latter group also tended to experience a decrease in self-efficacy, which was explained by the fact that many students perceived receiving grades and critical comments as overwhelming. The students who received grades only had less favorable motivational outcomes than those receiving comments, while those who did not receive any feedback highlighted performance approach goals. In another six-week intervention (Erturan-Ilker, 2014) conducted in the context of physical education, the researchers tested the relationship between positive and negative feedback and different goal orientations. Positive feedback emphasized encouragement, praise, and recognition of good performance, effort, and ability, while negative feedback highlighted deficiencies or underperformance, focusing on individual effort, ability, and outcome. Not so surprisingly, positive feedback led to increased preferences for mastery goals (focus on improving yourself) and performance approach goals (outperform others), a reduction in performance-avoidance goals (focus on avoiding failure), and a more mastery-oriented climate in the class. Negative feedback increased the student's performance-avoidance goals and reduced their preferences for mastery goals.

Results from several studies indicate that changing students' and teachers' beliefs, attitudes, or practices more permanently is challenging. For instance, four different conditions were tested in a study of contingent feedback (making the connection between the feedback and task performance more visible to the student) (Siero and van Oudenhoven, 1995). In the most successful condition, which contained increased visibility, explicit references to the effort as a cause for performance outcomes, and introduction of clear goals, students boosted their control beliefs and improved their achievement. However, the positive effect seemed to diminish over time. In another intervention focusing on improving grammar in English writing, the researchers found an immediate increase in student engagement and use of strategies (Santanatanon and Chinokul, 2022). Still, the effect eventually waned because students forgot the strategies they had learned, and the new practice was not maintained. Finally, in a more extensive intervention study with 40 teachers and more than 1,000 students, the researchers aimed to change teachers' and students' perceptions and beliefs of feedback from the more traditional summative thinking to formative thinking (Sandal et al., 2022). The project included teacher seminars, school-based workshops on goal setting, and various formative feedback forms/activities (e.g., formative use of tests, planned dialogues, and use of learning partners). During the 7-month intervention period, one revealed improved practices and changes in the teachers' awareness of formative feedback's function to enhance learning, self-regulation, and student engagement. Even though an increased engagement was seen among the students, their attitude toward feedback did not change. They still primarily viewed feedback as summative, focusing on grades rather than as a tool for learning.

Several studies have included technology or tools to assist with the feedback, and the outcomes are mixed. In one study (Admiraal et al., 2020), teachers used information based on learning analytics to tailor students' learning tasks and their feedback. The results revealed that the adapted tasks and feedback benefited low-performing students, as they experienced improved understanding, increased engagement, and effort, and they valued the feedback more. On the other hand, high-performing students did not see adapted tasks and feedback as much value added. However, the results indicated that these students improved their self-confidence and pride by helping their peers. Another common tool in formative assessment and feedback is rubrics (Wollenschläger et al., 2016). A study tested three variations of rubrics in science education, ranging from the most limited—providing only the learning goal (Condition 1)—to the most extended (Condition 3), which included specific feedback on the student's current performance, explicit instructions for improvement, and a rubric indicating achieved levels while leaving uncompleted levels unmarked. The results revealed that the students in the third condition improved their planning ability over time, increased their perceived competence, and improved their ability to evaluate their performance. Moreover, the researchers concluded that task improvement information was the most critical component for successful teacher-given rubric feedback.

Finally, we want to mention two studies (also mentioned in the achievement section) where technology is a key feature or encapsulates the feedback. In the first study, an electronic handheld device that allowed teachers and students to provide immediate feedback during lessons was tested across several subjects in a large number of schools (Wiggins et al., 2017). Even though both students and teachers had largely positive experiences with the system, and one saw short-term positive effects on student motivation, particularly in terms of engagement and enjoyment, these were insufficient to overcome the broader challenges or lead to sustained improvements in academic performance. Lastly, we want to mention the study made in the context of a virtual reality design in natural science, where researchers tested a peer assessment instructional design upon a more classical instructional design with teacher feedback (Chang et al., 2020). Their findings indicated that the teacher feedback approach provided clear and directed support, but the peer assessment approach yielded better outcomes in fostering critical thinking, self-reflection, and deeper engagement. These latter findings may indicate that the success of feedback also might depend on the learning content and how the instruction is orchestrated.

3.2.2 Teacher feedback and cognitive outcome in observational studies

Overall, 47 of the included observational studies dealt with cognitive phenomena (see Table 4), and due to the large number of studies in this category, we cannot, for reasons of space, elaborate on all of the studies but rather present the main features of these studies. Though most observational studies are based on students' perceptions through the data (e.g., self-reported data, questionnaires, interviews), 17 studies focused specifically on students' perceptions or experiences of feedback. This is, for instance, about how students with different personal characteristics and backgrounds experience various types of feedback. In addition, some studies compare students' and teachers' feedback experiences.

Table 4. Overview of the included observational studies on students' cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcome of teacher feedback.

Four studies indicate that males and females may perceive the feedback differently or actually receive different feedback. A Chinese study found that female students felt they received more directive feedback and less criticism than males (Guo, 2021). Another study from France (Nicaise et al., 2007) revealed that girls reported more encouragement after errors, while boys noted more criticism and felt ignored. Moreover, two studies from Denmark reported that girls sensed that they received less feedback than boys (Sortkaer, 2019; Sortkær and Reimer, 2021), which the authors explained by unconscious teacher bias. The studies from Denmark also indicated that students with higher SES and high-achieving students received less feedback than those with lower SES and low-achieving students.

Two studies compared teachers' and students' perceptions of feedback (Pat-El et al., 2015; Van der Kleij, 2019) and found that teachers often believe they provide clear and constructive feedback, but students may not perceive it similarly. Instead, the students often find the feedback insufficiently tailored and actionable or too focused on grades. An interesting finding in one of these studies (Pat-El et al., 2015) was that students with higher language proficiency experience feedback more similarly to teachers, which may indicate a challenge in communication and individual adaptation.

Several studies explored students' perceptions of a specific feedback form and linked them to particular outcomes. One study focused on students' conception of feedback (Lee, 2021) and found that students linked process feedback to formative and summative assessment. In contrast, corrective feedback was associated with summative assessment, while outcome feedback was related to surface-level learning. Another study (Krijgsman et al., 2019) linked process feedback to the satisfaction of students' basic psychological needs (the concepts of self-determination theory, Ryan and Deci, 2017). However, other studies indicate that corrective feedback can also positively impact students' basic psychological needs if the feedback holds sufficiently high quality (Vergara-Torres et al., 2021, 2020). In these latter studies, students' judgement of the feedback's legitimacy was conceptualized as a mediator between the feedback given and the psychological outcome. Two studies linked positive perceptions of teacher feedback to the use of cognitive strategies (He et al., 2023) and intrinsic motivation (Koka and Hein, 2006), while another study linked the perceptions of individualized feedback to academic self-concepts (Helm et al., 2022). Finally, one study linked perceived learning goal support, subject interest and perceived self-regulation skills in English to students' perceived usefulness of teacher feedback (Vattøy and Smith, 2019). Although these findings are interesting in their own right, we will remark that many of them reveal from explorative studies, appear isolated or are made in specific contexts, making it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions.

Thirteen studies concern students' own preferences for feedback, and a consistent finding is that students prefer direct, individualized, comprehensive, and detailed feedback with suggestions for improvement (Brooks et al., 2019; Burner, 2016; Cowie, 2005a; Ganapathy et al., 2020b,a; Lee, 2008; Sewagegn and Dessie, 2020; Tay and Lam, 2022; Williams, 2010; Zohra and Fatiha, 2022; Zumbrunn et al., 2016). According to some studies, students rate explicit feedback focused on improvement over prompts for self-reflection and self-regulation (Brooks et al., 2019), which might be the type of feedback teachers often prefer. However, studies also indicate that more indirect feedback, e.g., prompting self-reflection or further processing, can also be valued by students if it's given systematically and the students are made familiar with the type of processing it requires (Mak, 2019). Some studies indicate that students sometimes struggle to understand teachers' feedback (Burner, 2016; Cowie, 2005a), and consequently, the possibility of dialogue between teachers and students is about the things the students value (Tan et al., 2019). Such a dialogue provides opportunities to elaborate on the feedback and clarify the message. Furthermore, in some studies, mutual respect and trust between teacher and student are highlighted as essential to translating feedback into action (Cowie, 2005a). When it comes to feedback students dislike, they highlight error-focused feedback or criticism they don't understand or consider unfair (Cowie, 2005a; Lee, 2008). Such feedback is considered demotivating, particularly for low-performing students (Lee, 2008). Conversely, highlighting strengths is seen as motivating (Tay and Lam, 2022). However, it should be mentioned that some studies conducted in the context of language learning reveal that students appreciate correcting feedback and marking errors (Ganapathy et al., 2020b,a; Lee, 2008; Zohra and Fatiha, 2022).

Several studies relate feedback to motivation. For example, studies indicate that constructive critique (Cunha et al., 2019), a high preference for mastery goals (Jang et al., 2015), and clear and comprehendible feedback (Sokmen, 2021) are positively associated with cognitive engagement with feedback. On the other hand, performance-oriented students tend to see feedback as a competence measure, expressing a fixed view of intelligence and being less likely to engage in improvement (Jang et al., 2015). One study suggests effective feedback should target both the task level, the process level, and self-regulation. Furthermore, the results indicate that such feedback can enhance students' autonomy, self-efficacy, the use of learning strategies and foster a supportive classroom environment (Monteiro et al., 2021). Another study suggests that feed-forward (e.g., Hattie and Timperley, 2007) enhances growth goal setting and academic engagement. Studies also indicate that positive feedback in the form of praise can enhance students' perceived competence and effort, particularly in physical education (Koka and Hein, 2003; Nicaise et al., 2007). Finally, we would like to highlight a large-scale study (Jiang et al., 2021, data from PISA 2015) that examined the relationship between perceived feedback and various motivational beliefs among students in East-Asian and Western countries. For students from both hemispheres, the most substantial relation was found with intrinsic motivation. In Western countries, this was followed by self-efficacy, instrumental motivation, and achievement motivation, while in East-Asian countries, the order was instrumental motivation, self-efficacy, and achievement motivation. These findings suggest that some relations between teacher feedback and student motivation are valid across diverse cultures.

The last topic we will address in this section is feedback related to homework, which is the focus of five studies (Cunha et al., 2019; Nunez et al., 2015; Tas et al., 2016; Xu, 2022; Xu et al., 2022). Three studies indicate that regular or frequent teacher reviews of students' homework can increase cognitive engagement and completion rates (Cunha et al., 2019; Nunez et al., 2015; Tas et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2022). Furthermore, if feedback is tailored and of high quality, it can contribute to a higher degree of self-regulation and influence the student's beliefs about the homework purpose (Nunez et al., 2015; Tas et al., 2016; Xu, 2022). Consequently, teachers' engagement in feedback seems to be a key factor that can positively affect students' homework outcomes.

3.2.3 Teacher feedback and cognitive outcome in small-scale studies

In total, 20 small-scale studies explored the relationship between teacher feedback and cognitive outcomes (see Table 5). One study found that students prefer specific, timely, clear, and actionable feedback with opportunities to revise and improve. General praise might be frustrating, while a lack of feedback is demotivating or confusing (Torkildsen and Erickson, 2016). Three studies (Ruthmann, 2008; Tan et al., 2019; Tay and Kee, 2019) pointed to findings where students' knowledge and understanding could increase based on teacher feedback. The first study was a cross-sectional case study highlighting several key factors in music education (Ruthmann, 2008). It emphasized the importance of teachers' feedback style and respect for student agency. Additionally, the study noted the significance of negotiating creative intent, the classroom environment, and the pedagogical design of composing experiences. These factors supported the development of musical knowledge, creative expression, reflective and metacognitive skills, and problem-solving skills in music technology. The second study, an instrumental case study, showed that students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder benefitted from teachers' precision in questioning, step-by-step guidance, extended wait time, use of visual supports, and capitalizing on interests (Tay and Kee, 2019). In addition, students benefitted from affirmative and personalized teacher feedback as it enhanced their focus and engagement, increasing the student's knowledge and understanding. The third study (Tan et al., 2019), built on self-determination theory, emphasized that in addition to teachers' asking thought-provoking and open-ended questions, the use of attentive listening was valued and increased students' metacognitive knowledge and understanding (knowledge and regulation of cognition).

Table 5. Overview of the included small-scale studies on students' cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcome of teacher feedback.

One small-scale quasi-experimental study examined the effects of direct and indirect written corrective feedback on students' written performance in English and found that students' attitudes toward feedback, beliefs about what the corrections entailed, and types of scaffolding increased students' knowledge and motivation in writing (Luan and Ishak, 2018). Another quasi-experimental study that focused on reading performance among behaviorally disordered students found that when teachers provided positive written comments on reading assignments each day, in addition to emphasizing contingent upon improved performance and maintained high outcomes, the students improved the accuracy of reading performance, and developed a favorable attitude toward the written feedback process (McLaughlin, 1992).

Three studies (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Honora, 2003; Mikume and Oyoo, 2010) found that teacher feedback could enrich students' cognitive-motivational changes. One action research study found that using self-correction and conferencing to supplement teacher written feedback improved the quality of students' written compositions and increased motivation and confidence in writing English as a second language (Mikume and Oyoo, 2010). Another qualitative study found that students who identify with the school's academic culture were more motivated to achieve and experience higher educational gains (Honora, 2003). This could be moderated based on students' gender and achievement level, positive or negative identification with the school and their perceptions of teacher feedback, support and accessibility. The third study, based on a descriptive research design (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022), found that teacher feedback that fosters self-correction helped students develop metacognitive skills, allowed them to analyze their thought processes and learn more effectively. Explicit oral corrections directly addressed gaps in knowledge and helped students understand their mistakes and learn the correct form or approach. This study also found that positive reinforcement boosted student motivation by fostering a supportive atmosphere and encouraging engagement without fear of criticism. Feedback that involved the student actively (e.g., self-correction) made the process collaborative and increased their sense of ownership and intrinsic motivation.

Two studies found the activation of students' beliefs about learning by the provisions of teacher feedback (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Murtagh, 2014). One of these studies, a Multiple Case Study Design, found that math-anxious students can benefit from effective feedback and clear learning objectives (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022). This study emphasized that especially three main factors were moderators. These were environmental factors: teacher's instructional practice, parental attitudes and beliefs in their child's math ability. Intellectual factors: Cognitive abilities and spatial reasoning skills, and personal factors: Self-efficacy and attitudes toward mathematics. The other study, a cross-sectional case study, investigated students' experiences of teacher feedback and found that it could enhance students' activation of beliefs about learning, knowledge, and the learning process (Murtagh, 2014). These improvements included understanding of learning objectives, self-regulation, and specific literacy skills (grammar, punctuation, writing style).

Two studies emphasize students' preferences for dialogic feedback interactions (Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Kerr, 2017). One small-scale qualitative study found that students' preferences for teacher feedback were dialogic feedback interactions that support their perceptions of learning and understanding (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). The participating students explained that the classroom climate, including honesty and objective feedback, is essential for the uptake. In addition, the teacher's feedback practice of providing opportunities and time to apply feedback, feedback type, and information about assessment criteria becomes central to students' perceptions of the quality of this feedback. The second multi-case study found that students prefer dialogue with the teacher, where the students can seek clarity through verbal feedback (Kerr, 2017). This study emphasized that variables like emotion, atmosphere, and expectations impacted the feedback process.

Two studies found how teacher feedback can strengthen students' perceptions of self-confidence (Bansilal et al., 2010; Bardine, 1999). One of these studies, an explorative naturalistic case study design in mathematics, found that students perceived teachers' assessment feedback as important in scaffolding their learning process and the teachers' feedback as instrumental in either building or breaking their self-confidence (Bansilal et al., 2010). The effect the feedback may have in building or breaking a student's self-confidence emphasizes the need for educators to provide constructive feedback that focuses on students' progress while avoiding derogatory comments that harm self-esteem. Another study, built on a multiple qualitative methods design, examined students' perceptions of written teacher comments on their papers and found that the teachers' feedback empowered students' self-confidence and encouraged active participation in learning tasks (Bardine, 1999). This study emphasized that the teachers' written feedback was clear, descriptive, and actionable and that the teachers managed to balance between praise and criticism. In addition, the students were given opportunities for revision and redrafting, and the teacher's tone and attitude were perceived as supporting. Similar results were found in an action research study (Torkildsen and Erickson, 2016). They found that students prefer specific, timely, clear, and actionable feedback with opportunities to revise and improve. General praise might be frustrating, while a lack of feedback is demotivating or confusing.

Two case studies focusing on classroom interactions and dialogues, probably based on the same data material, found that teachers and students often perceive feedback differently and that students do not always understand teachers' intentions (Van Der Kleij and Adie, 2020; Van der Kleij, 2023). Over 30% of the feedback went unrecognised by students. Math feedback was more often correctly understood than English feedback, likely due to its factual nature. Students often saw teachers' questioning as attention checks and themselves as feedback recipients rather than active participants. Students preferred clear, corrective explanations over open, discussion-based feedback.

Finally, three studies on teachers' feedback and students' engagement are found (Cowie, 2005b; Dang, 2021; Lefroy, 2020). One study, a sequential qualitative design in science, found that teacher feedback influenced students' self-perception as competent knowers of science and engagement with learning (Cowie, 2005b). This study revealed that the level of trust and respect in teacher-student interactions was essential for students' engagement and classroom social dynamics. Regarding students' self-perception and identity, this study found that students' beliefs about learning and identification with school culture affected engagement with feedback. Another study, a mixed methods research design, found that students' engagement with teacher feedback in a correcting process increased understanding (accuracy improvement) and increased learning motivation (Dang, 2021). This study found that the collaborative correcting process, incorporating teacher mediation and peer collaboration, led to positive student cognitive outcomes. In addition, it was emphasized that student engagement with teacher feedback was the most crucial variable contributing to students' learning outcomes. A third study, with a qualitative case study design with a sample of high-achieving English students, found that teachers' audio feedback and overwritten feedback enhanced students' resilience and active participation in learning English (Lefroy, 2020). The students explained that a sense of being valued, in addition to a positive and trusting relationship between teacher and student, was important for their value of the type of teacher feedback.

3.2.4 Brief summary of the findings concerning feedback and cognitive outcome

Overall, the review of the studies on cognitive outcomes indicates that teacher feedback can influence students' motivation and learning in several ways. Process-oriented and individualized feedback appears to strengthen students' competency-based motivation, such as self-efficacy and control beliefs. Clear, detailed, and actionable feedback can increase students' interest and positive attitudes toward learning. Self-referenced feedback (focusing on one's development) increases students' confidence more than norm-referenced feedback (compared with others/grades). Feedback tailored to goal orientation may shape learning preferences, with positive feedback promoting mastery goals and negative feedback increasing avoidance tendencies. In general, harsh critique and negative feedback destroy students' motivation and engagement. Most students prefer direct, constructive, and actionable feedback. Teacher engagement in the feedback appears to be important for student engagement and follow-up on feedback, as is trust and respect in the relationship between student and teacher. Dialogic feedback can also increase student engagement and is considered helpful for clarifying and elaborating the feedback message and increasing students' understanding. Feedback may also indirectly influence the classroom climate through student's behavior. Gender, achievement level, and student perceptions may impact students' uptake and outcome of feedback. Finally, students and teachers may sometimes perceive the quality of feedback differently.

3.3 Teacher feedback and emotional outcome

3.3.1 Teacher feedback and emotional outcome in intervention studies

Only four of the intervention studies present explicit emotional outcomes. One study (De Meester et al., 2020) shows that including positive comments in corrective feedback can reduce students' frustrations. Another study shows that the pupils enjoyed improved assessment practice with explicit criteria, rewards, more student activity, dialogue and interaction (Ozan and Kincal, 2018). The third study found that strengthened grammar feedback with error codes and explanations in English foreign language was associated with increased students' emotional engagement (Santanatanon and Chinokul, 2022). The last study found that a positive approach to error handling, like learning from errors, led to a more trustful classroom climate and reduced students' level of anxiety (Sokmen, 2021). Although the number of studies is limited, the findings are consistent with previous research and various motivation theories.

3.3.2 Teacher feedback and emotional outcome in observational studies

Twelve of the observational studies reported findings related to emotions. Most of these reported emotions as an outcome of a specific feedback type. Frequent feedback (Chi et al., 2021), positive general feedback (Koka and Hein, 2003), and praise and increased attention (Nicaise et al., 2007) were found to be positively associated with students' enjoyment. Conversely, criticism was negatively associated with students' enjoyment (Nicaise et al., 2007) and positively related to negative emotions (Zumbrunn et al., 2016). Constructive feedback (Harris et al., 2014) and positive comments (Oinas et al., 2021) were positively associated with positive emotions in students, while one study found that process feedback and goal clarification were negatively associated with need frustration (Krijgsman et al., 2019). Building on self-determination theory, one study suggests that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are mediators between corrective feedback and students' wellbeing (Vergara-Torres et al., 2021). Another study found that positive emotions were most frequent when students received feedback but that various emotions were at play, such as hope and calm (Lui and Andrade, 2022). Moreover, the same study found that positive emotions were positively related to favorable judgement of the feedback (e.g., the meaningfulness). One study found that the emotional outcome of the feedback was related to under- and overestimation of competence (Jang et al., 2015). If the student overestimated their competence, the feedback could cause negative emotions such as frustration, while the opposite could cause positive emotions like surprise and pride. Finally, positive feedback, like praise (Cunha et al., 2019) and clear and understandable feedback (Sokmen, 2021), was related to increased emotional engagement.

3.3.3 Teacher feedback and emotional outcome in small-scale studies

Eleven small-scale studies explored the relationship between teacher feedback and students' emotional responses. Across the eleven studies (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Bardine, 1999; Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Honora, 2003; Kerr, 2017; Lefroy, 2020; Luan and Ishak, 2018; Tay and Kee, 2019; Torkildsen and Erickson, 2016; Van Der Kleij and Adie, 2020), teacher feedback emerges as a multifaceted tool influencing students' emotional outcomes. Most of the studies reported several emotional outcomes. Thus, this text presents representative themes with integrated findings from the nine studies, providing a cohesive overview of emotional outcomes and their underlying causes.

Five studies demonstrate that clarity and specificity of feedback are fundamental to students' emotional responses to feedback and that clear, detailed feedback promotes confidence (Bardine, 1999; Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Lefroy, 2020; Luan and Ishak, 2018). One study highlights how ambiguous comments frustrate students, while detailed feedback fosters trust and confidence (Bardine, 1999). Similarly, two studies (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013) demonstrate that actionable feedback alleviates anxiety and reassures students about their abilities. One study found that while audio feedback can be motivating due to its relational tone, unclear messages can increase stress (Lefroy, 2020). Finally, one study found that direct feedback instills confidence but may sometimes undermine independent thought (Luan and Ishak, 2018).

Four studies found that positive vs. negative feedback is an essential theme for students' emotional outcomes (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Bardine, 1999; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Luan and Ishak, 2018). The tone and framing of feedback significantly influence students' emotional states. Positive and supportive teacher feedback reduces anxiety, as seen in Aedo and Millafilo (2022), where non-threatening feedback fosters positive emotions. One study found that specific praise validates effort, boosting motivation (Bardine, 1999), while another indicates that constructive feedback enhances competence (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). Conversely, as noted in Aedo and Millafilo (2022), Gamlem and Smith (2013), Luan and Ishak (2018), harsh or overly critical comments lead to frustration or discouragement, emphasizing the need for a constructive approach.

Five studies demonstrate that feedback's timing and delivery method affects how students process and respond to it (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Kerr, 2017; Lefroy, 2020; Luan and Ishak, 2018; Torkildsen and Erickson, 2016). Immediate feedback can increase stress, especially for younger learners, as indicated in Aedo and Millafilo (2022). Students' mood and readiness influence their receptiveness to teacher feedback, with one-to-one sessions reducing anxiety (Kerr, 2017). Audio feedback is often appreciated for its personal touch but may overwhelm students compared to written feedback (Lefroy, 2020). Timing and effort required to decode indirect feedback initially frustrate students but lead to satisfaction upon mastery (Luan and Ishak, 2018).

Three studies found that trust and emotional safety in the classroom are pivotal in shaping students' emotional responses (Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Honora, 2003; Lefroy, 2020). Studies show that a trusting teacher-student relationship fosters receptiveness to feedback, while distrust undermines this (Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Lefroy, 2020). One study underscores how a lack of teacher support or perceived differential treatment contributes to alienation and distrust, particularly among lower-achieving students (Honora, 2003).

Three studies demonstrate that students' emotional states and engagement readiness significantly influence feedback's impact (Kerr, 2017; Luan and Ishak, 2018; Van Der Kleij and Adie, 2020). One study highlights how personal stressors or a poor mood can block feedback processing, emphasizing the need for emotional readiness (Kerr, 2017). Similarly, another study suggests that alignment with students' expectations about feedback determines whether the response is positive or negative (Luan and Ishak, 2018).

Two studies found that perceived effort and self-appraisal are outcomes based on teacher feedback (Honora, 2003; Luan and Ishak, 2018). Feedback that challenges students' effort or supports self-appraisal elicits mixed emotional responses. One study shows how lower-achieving students often associate their worth with compliance rather than academic success, leading to disengagement (Honora, 2003). Another study found that students express frustration with indirect feedback but later report pride and satisfaction upon mastering its challenges, highlighting the importance of balancing effort and guidance (Luan and Ishak, 2018).

Two studies demonstrate that affirmative feedback reduces anxiety and fosters engagement (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Tay and Kee, 2019). One study demonstrates that specific feedback and reassessment opportunities reduce math anxiety by shifting focus from grades to mastery (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022). Another study emphasizes how affirming feedback, such as verbal praise or physical gestures, creates a safe environment that reduces stress and fosters confidence (Tay and Kee, 2019).

Finally, two studies demonstrate that feedback that integrates relational and social dynamics positively impacts students' emotional responses (Kerr, 2017; Lefroy, 2020). Audio feedback might strengthen motivation through its empathetic tone (Lefroy, 2020), while the value of informal feedback sessions in reducing intimidation and enhancing engagement (Kerr, 2017). Overly formal settings can create barriers, and thus, suggestions for a need for balance are argued for (Kerr, 2017).

3.3.4 Brief summary of the findings concerning feedback and emotional outcome

Teacher feedback significantly influences students' emotional outcomes, shaping confidence, engagement, and anxiety levels. Intervention studies highlight that positive comments reduce frustration, clear assessment criteria improve emotional engagement, and a constructive approach to errors fosters a supportive classroom climate. Observational studies find frequent, clear, and encouraging feedback enhances enjoyment, while criticism leads to negative emotions. Self-perception plays a role, with overestimated competence leading to frustration and underestimated competence fostering positive emotions. Small-scale studies emphasize the importance of clarity, tone, and timing in feedback delivery. Clear and actionable feedback builds confidence, while harsh or ambiguous feedback can cause stress. Trust in teacher-student relationships and an emotionally safe environment increase receptiveness to feedback. Personalized and relational feedback, including audio and informal sessions, can boost motivation and engagement. Ultimately, constructive and empathetic feedback fosters emotional wellbeing, while negative or unclear feedback risks alienation and disengagement.

3.4 Teacher feedback and behavioral outcome

3.4.1 Teacher feedback and behavioral outcome in intervention studies

Six of the intervention studies reported some form of behavioral outcome, and all these studies are previously mentioned in Section 2.1 and some in Section 3.1. Three of the studies reported increased engagement/behavioral engagement. In one study, the increased engagement was related to a comprehensive intervention to change students' beliefs about feedback (Sandal et al., 2022). In another study, engagement change was related to strengthened grammar feedback using error codes and explanations in English foreign language learning (Santanatanon and Chinokul, 2022). Lastly, one study found that feedback technology in the classroom, a handheld device for direct communication with the teacher, temporarily increased students' engagement (Wiggins et al., 2017).

Two studies reported improved strategic learning behavior. One study found increased self-regulated learning due to an intervention focusing on goals and criteria, increased student inquiry and dialogue, and specific tailored progress feedback (Ozan and Kincal, 2018). Another study found an increased use of reading strategies after feedback on reading strategy utility with fading overt verbalization (Schunk and Rice, 1993). In addition to these studies, a study tested three types of rubrics in science education and found that the most comprehensive rubric increased students' performance in planning experiments (Wollenschläger et al., 2016).

3.4.2 Teacher feedback and behavioral outcome in observational studies

Twenty-three observational studies reported some form of behavioral outcome; most studies are already mentioned in the previous sections (see Table 4). However, in this section, we will highlight these studies' behavioral aspects, hopefully without repeating too much information. We will start with six studies that report associations between teacher feedback and students' behavioral engagement and actions. In one study (Cunha et al., 2019), the researchers found that regular checking of homework combined with positive feedback increased students' homework engagement and effort. Similar results were reported in another study that found that teachers' homework engagement predicted homework effort and completion (Xu et al., 2022). A longitudinal study (Mak, 2019) found that an improved feedback practice, including clear criteria before, constructive input during, and reflection after writing assignments, increased students' engagement in writing. A fourth study found a positive relationship between clear, comprehensible, and constructive feedback and behavioral engagement (Sokmen, 2021), while a fifth study found that feed-forward enhanced students' engagement both directly and indirectly through growth goal setting (Martin et al., 2022). Finally, one study found that students' task value consideration influenced their actions on feedback (Lui and Andrade, 2022). Together, these studies highlight some properties of teacher feedback that hopefully can promote students' behavioral engagement. Conversely, a study found that a lack of understanding of the feedback message can lead to students not following up on feedback (Burner, 2016), and another study outlines that students' inclination to act on the feedback sometimes depends on trust in the teacher-student relationship (Cowie, 2005a). Finally, one study found that teachers' praise increased students' efforts in physical education, while criticism reduced their performance (Nicaise et al., 2007). These are aspects that may be worth taking note of.

We have previously presented findings indicating that girls and boys may perceive teacher feedback differently. A study thus finds that girls and boys also may act differently (Guo, 2021). In the setting of scaffolding feedback (hints or clues to help students arrive at the correct answers independently), male students reported higher use of critical thinking strategies. In comparison, females reported higher use of self-resource management strategies. This leads us to teacher feedback's function in relation to self-regulated learning.

Seven other studies report outcomes related to students' strategic learning. One study found that students' positive feedback perceptions promoted their use of self-regulation strategies in the context of science learning (He et al., 2023). Another study considered students' feedback perceptions as a mediator between self-efficacy and self-regulation in the context of writing (Zumbrunn et al., 2016). A third study found that comprehensive feedback targeting the task, process, and self-regulation level enhanced students' use of learning strategies and facilitated positive classroom behavior (Monteiro et al., 2021). Moreover, a fourth study reported that students found timely, detailed feedback most valuable for revising assignments and planning future strategies (Sewagegn and Dessie, 2020). Two studies found that regular homework reviews by the teacher with tailored and constructive feedback enhanced students' self-regulation (time management, deep learning strategies) and homework performance (Nunez et al., 2015; Tas et al., 2016). Finally, one study emphasized that two-way feedback could empower students to develop self-regulation skills (Tan et al., 2019).

Finally, we have five studies that are not so easy to categorize. One study reported that actionable feedback drove improvement, while success criteria checklists can enhance students' feedback processing (Tay and Lam, 2022). Another study found that the quantity of homework feedback predicts self-regulation and approval-seeking, while the quality of the feedback predicts students' motivation and purposes (Xu, 2022). One study found that the constructs of self-determination theory, autonomy, competence, and relatedness were mediators between corrective feedback and students' energy and enthusiasm (Vergara-Torres et al., 2021). Another study pointed out that technology-enhanced feedback may not contribute to students' self-regulation but rather make them externally regulated (Oinas et al., 2021). Finally, we would like to mention a large-scale study that found that systematic use of positive teacher feedback was associated with lower suspension rates across 1,500 classrooms (Scott and Gage, 2020).

3.4.3 Teacher feedback and behavioral outcome in small-scale studies

In total, 11 small-scale studies explored the relationship between teacher feedback and students' behavioral responses (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Bardine, 1999; Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Honora, 2003; Kerr, 2017; Lefroy, 2020; Luan and Ishak, 2018; Rathel et al., 2014; Sutherland et al., 2000; Tay and Kee, 2019). These studies found a variety of student behavioral outcomes such as engagement and participation, emotional and social impact, task completion and focus, gender, and individual differences.

Six studies found that positive and constructive teacher feedback plays a crucial role in fostering active participation and engagement among students (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Bardine, 1999; Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013; Lefroy, 2020; Tay and Kee, 2019). Two studies demonstrate that actionable and encouraging feedback enhances classroom participation, risk-taking, and a willingness to engage with tasks (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Bardine, 1999). Similarly, one study highlights how formative assessments promote self-assessment and active learning (Fergus and Petrick Smith, 2022), while another study shows that useful teacher feedback encourages task revision and deeper involvement in learning activities (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). Feedback provided in dynamic formats, such as audio feedback (Lefroy, 2020) and strategies tailored to students' interests (Tay and Kee, 2019), further strengthened participation and engagement. However, studies warn that negative or judgmental feedback can lead to avoidance and reduced classroom effort (Aedo and Millafilo, 2022; Gamlem and Smith, 2013).

Five studies demonstrate that the format and clarity of teacher feedback significantly shape students' behavioral responses (Bardine, 1999; Lefroy, 2020; Luan and Ishak, 2018; Rathel et al., 2014; Sutherland et al., 2000). One study found that clear, specific, and actionable feedback helps students effectively revise their work and understand expectations—and conversely, vague or ambiguous feedback can lead to task avoidance and superficial edits (Bardine, 1999). One study highlights that audio feedback encourages students' active engagement and resilience (Lefroy, 2020), whereas another study found that written feedback supports structured revisions for students who prefer clarity (Luan and Ishak, 2018). Two studies demonstrate how well-defined guidance improves task engagement and focus using behavioral-specific praise (Rathel et al., 2014; Sutherland et al., 2000). These findings indicate that teacher feedback's actionable nature and format directly influence how students respond and engage.