- Faculty of Psychotherapy Sciences, Institute for Training Research, Sigmund Freud Private University, Vienna, Austria

Despite a growing body of research on online teaching in psychotherapy training, existing studies focus on students’ experiences, leaving the perspectives of lecturers underexplored. This study addresses this gap by investigating lecturers’ views on the transition to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected through 13 semi-structured expert interviews with lecturers at the Faculty of Psychotherapy Science at Sigmund Freud Private University, conducted between November 2022 and December 2023. Thematic content analysis was employed to analyze the data. The findings indicate that online teaching is suitable for specific components of psychotherapy training, such as theoretical foundations, research methods, supervision, and individual self-experience. However, practice-oriented training and group self-experience, which depend on direct personal interaction, were significantly hindered by the online format. Lecturers identified challenges in fostering engagement, sustaining attention, and maintaining relational depth, largely due to the lack of non-verbal cues and shared physical spaces. The study concludes that relational skills, central to psychotherapy training, are best developed through in-person interaction. Nonetheless, a blended learning approach that combines online and face-to-face teaching is recommended. Online tools provide flexibility and efficiency, particularly for theoretical components, but their successful integration requires thoughtful course design and targeted lecturer training. The findings underscore the need for a balanced approach to optimize the strengths of both online and traditional teaching formats in psychotherapy training.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges to higher education, forcing universities worldwide to transition rapidly to online teaching formats (Aucejo et al., 2020). In Austria, the federal government’s lockdown regulations made face-to-face teaching impossible, prompting universities to adopt either fully online or hybrid formats, where courses are held on-site while simultaneously being streamed online (Ulla and Perales, 2022). The spontaneous transition from face-to-face teaching to online formats differs from planned online teaching as the pandemic required immediate measures (Hodges et al., 2020). The current study investigated emergency remote teaching in distinction to well-planned online teaching strategies.

Research on emergency online formats indicates that university lecturers had to rapidly adjust their pedagogical approaches to integrate new technologies (Hodges et al., 2020). The swift transition to online formats posed several challenges such as technical difficulties, inequalities in access to digital resources (Ali, 2020; Malewski et al., 2021), and lack of feedback from both students and lecturers (Krammer et al., 2020). The rapid shift also led to an increased workload for lecturers due to the need for more structured designs and had a negative impact on student motivation (Malewski et al., 2021). In contrast, students welcomed access to advanced learning resources (e.g., tutorials, online learning platforms), structured assignments, and the availability of teachers (Ali, 2020; Krammer et al., 2020).

The Sigmund Freud Private University (SFU) in Vienna, which offers a consecutive bachelor’s and master’s program in psychotherapy science, also transitioned to online formats for the first time during the summer semester of 2020. In a dual approach, the study programs combine academic studies in psychotherapy science with vocational training as a psychotherapist, aiming to integrate a solid theoretical foundation with practice-oriented aspects. This integration is achieved through a curriculum that balances five essential components of psychotherapy training: theoretical foundations and research methods, practice-oriented courses, individual and group self-experience, practical work with patients, and supervision (for a brief description of these components see the Supplementary materials).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all courses at the SFU were delivered in-person, and many lecturers had no experience with online teaching. While online formats are more established in other disciplines (Griesehop and Bauer, 2017), psychotherapy science has traditionally emphasized the importance of face-to-face interaction. This is particularly crucial for key components of the training, such as the integration of theoretical knowledge with practical skills, emotional learning, and personal development through self-experience and hands-on practice. These elements, along with collaborative interactions within training groups, are considered essential for high-quality psychotherapeutic work (Ferrel and Ryan, 2020; Griesehop and Bauer, 2017; Taubner and Evers, 2020) and are generally regarded as more effectively facilitated in a physical classroom setting.

Overall, studies on online teaching in psychotherapy training are limited. In a recent systematic review, Mikkonen et al. (2024) analyzed studies from 17 different countries comparing online learning programs with traditional training formats. The studies investigated the perspective of students on their learning outcomes, their satisfaction with the training format and the transfer of knowledge into clinical practice. The studies highlighted the value of integrating interactive elements such as case study analyses, simulations, role-plays, discussion forums, feedback, peer-support groups, or group projects into the online format. These elements fostered students’ acceptance of the online format and motivated them to actively engage in learning processes, contributing to a deeper understanding of the course subject and knowledge transfer into practice. Students demonstrated a positive attitude and acceptance of the online format when theoretical and practical courses were adapted through multimedia content (animations, games, audio, and video examples) or exchange forums (Mikkonen et al., 2024). An Austrian study by Akgün et al. (2023) explored psychotherapy students’ perspectives on online learning during the pandemic and revealed mixed reactions. According to the students, short theoretical courses were generally considered suitable substitutes for in-person teaching, and many reported that online learning improved their work-life balance. However, they perceived the lack of physical interaction as a significant barrier to building relationships and fostering a sense of community. Students also highlighted varying experiences with the quality of online teaching. They noted that effective communication and lecturers’ ability to adapt their teaching styles to the digital format helped mitigate challenges such as technical difficulties, monotonous lectures, and organizational issues (Akgün et al., 2023).

Despite the growing body of research on online teaching in psychotherapy training, existing studies focus solely on students’ experiences, leaving a significant gap in understanding the specific challenges and opportunities of online formats from the perspective of lecturers. To complete the picture, the present study explores the perspective of lecturers on the transition to online teaching in psychotherapy training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through qualitative interviews, the study provides insights into the opportunities and challenges of online teaching and how lecturers addressed these challenges. The findings contribute to a better understanding of how online teaching can be integrated into various course formats (theoretical and practical courses, supervision and self-experience) and may help inform the development of online teaching strategies in psychotherapy training.

2 Materials and methods

This study employed a cross-sectional design with a qualitative research approach.

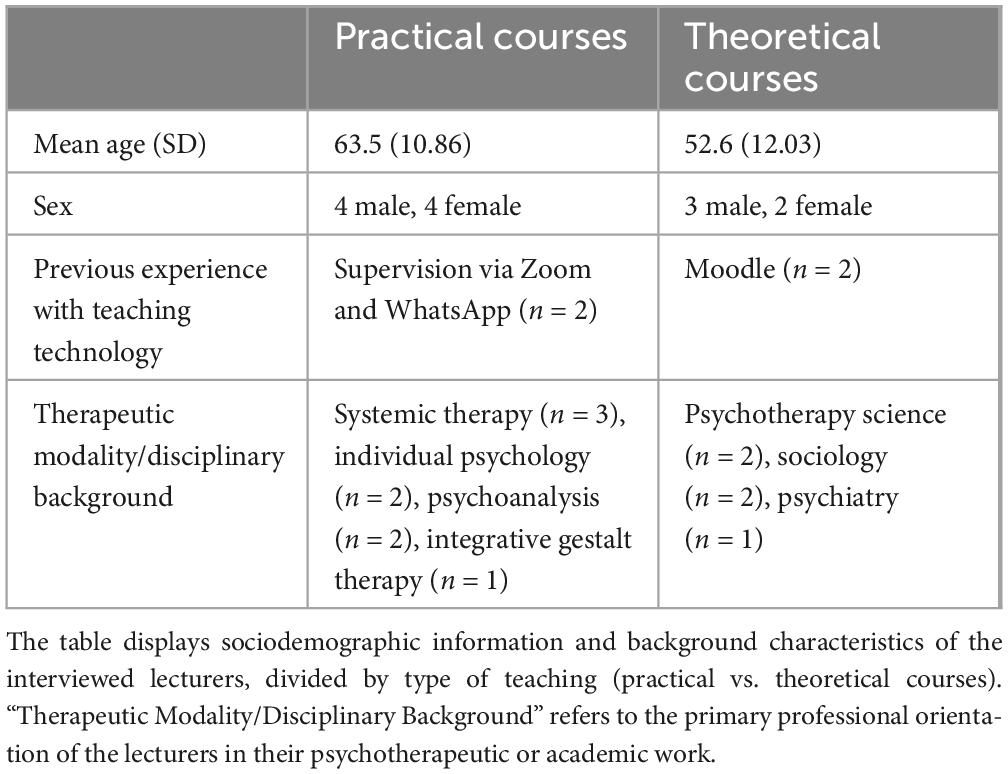

In November 2022, all lecturers at the Faculty of Psychotherapy Science at Sigmund Freud Private University (N = 172) were invited to participate in the study. A total of 13 lecturers (seven male, six female) between the ages of 42 and 73 with a mean age of 58.62 years (SD = 11.89) consented to participate in the study. The sample was composed of lecturers who taught exclusively in the theoretical part of training (n = 5) as well as those who taught practice-oriented components (n = 8). With the exception of two interviewees who had some experience with Moodle and two who had carried out online supervision before, none of the lecturers had used technology in teaching prior to the pandemic. The abovementioned characteristics as well as the lecturers’ therapeutic modalities and areas of expertise are shown in Table 1.

Data collection took place between November 2022 and December 2023, using semi-structured expert interviews. The interview guide was developed to explore the following areas: the transition from face-to-face to online teaching, the didactic implementation of theoretical content, technical requirements and the teaching setting, the self-perception of lecturers, and the implementation of practical training content, including self-experience and supervision. Each interview lasted approximately 30 min. Interviews were conducted in a one-to-one setting, except for interview 4, in which two lecturers were present. They were labeled person 1 and person 2 in the interview code.

The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Faculty for Psychotherapy Science, Psychology, Law at SFU Vienna, Austria (Ethical number: EDBNCXYDCAMBWX91288). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring that they were aware of their rights and the voluntary nature of participation. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

The data were analyzed using thematic analysis following the methodology of Braun and Clarke (2006), Clarke and Braun (2017). An inductive, semantic approach was employed, where codes and themes were generated directly from the data, focusing on explicit meanings rather than underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualizations. The analysis followed six iterative phases, including back and forth movement between phases as needed, enabling a reflective process and deep immersion in the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In the first phase of analysis, CS familiarized herself with the data by listening to the full-length audio recordings of all interviews before starting transcription. During and following transcription CS started marking ideas for coding. In the second phase, known as “generating initial codes,” CS worked through the entire transcript of each interview, coding text segments and identifying interesting aspects in the data that may form the basis of repeated patterns (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Accounts which departed from observed patterns were also included. In phase three, known as “searching for themes,” the codes were examined to identify broader patterns of meaning and combined into overarching themes and subthemes. At the same time, an initial narrative was created. In the fourth phase, the generated themes were revised and reassessed to ensure that they were meaningfully connected and clearly distinguishable. This iterative revision process was conducted within the research group to ensure the validity of the themes. In the fifth phase, the structure of each theme was further refined and adjusted. The working titles of the themes were adapted to the narrative the research group had started to develop. Finally, the refined themes and sub-themes were presented in a comprehensive report of the findings. To ensure that this report provides an argument which goes beyond an inductive, semantic analysis, we included a detailed discussion linking our findings to existing literature.

3 Results

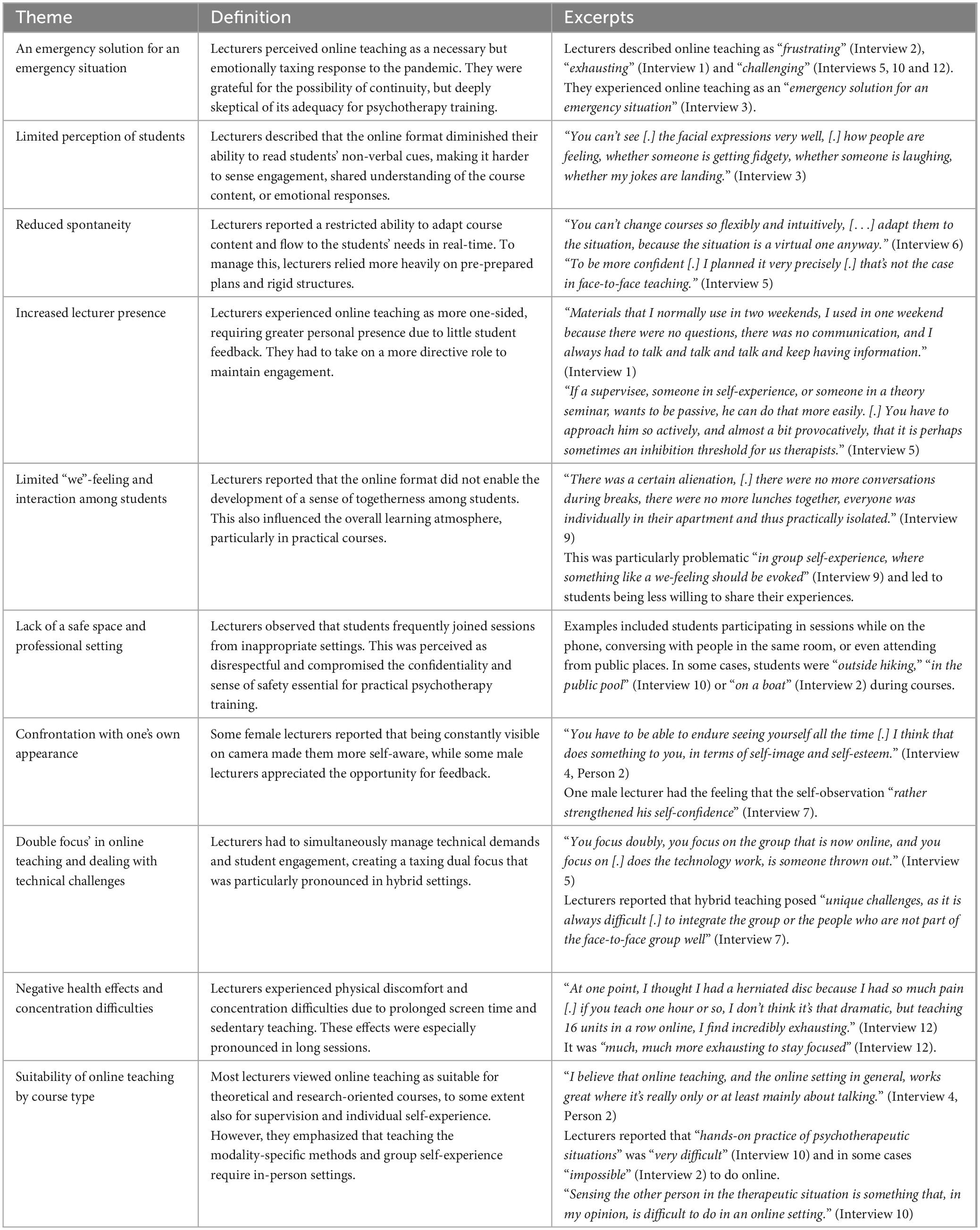

In the following, the lecturers’ experiences with specific aspects of online teaching are presented in detail. The respective sections first outline the difficulties lecturers encountered and then describe which factors were perceived as helpful regarding the aspect discussed. The first section summarizes the lecturers’ overall impressions of online teaching. The section “Suitability of online teaching by course type” discusses experiences with online teaching in distinct types of courses, drawing partly on results from earlier sections. A summary of the findings is shown in Table 2, which offers an overview of the themes identified in the interviews, including concise definitions and selected excerpts illustrating lecturers’ perspectives on online teaching during the pandemic.

3.1 An emergency solution for an emergency situation

In addition to describing the difficulties and opportunities of online teaching, the interviews provided a picture of how the lecturers felt about online teaching. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all courses that had previously taken place in person suddenly had to be switched to video conferencing without adequate preparation on the part of the universities. Against this background, most lecturers described online teaching as “frustrating” (Interview 2), “exhausting” (Interview 1) and “challenging” (Interviews 5, 10, and 12). They experienced online teaching as an “emergency solution for an emergency situation” (Interview 3); one lecturer compared the online medium to a hospital and said, “I am very glad that these facilities exist, but I prefer it even more if I don’t have to use them” (Interview 6). Although all lecturers emphasized the indispensability of face-to-face teaching, there were certain types of courses for which they felt online formats were very suitable. In some cases, these were maintained even after the COVID-19 measures were lifted. Many lecturers described that a combination of online and face-to-face teaching could make sense.

3.2 Limited perception of students

Due to the physical distance inherent in online teaching, many lecturers found it challenging to perceive and respond to students’ needs, making it difficult to establish a sense of connection. They reported that the limited visibility of students on screen hindered their ability to pick up on non-verbal cues such as facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, breathing, and tone of voice – elements crucial for conveying presence. As one lecturer noted, “You can’t see [.] the facial expressions very well, [.] how people are feeling, whether someone is getting fidgety, whether someone is laughing, whether my jokes are landing” (Interview 3). Another added, “Who is sitting where, how someone is looking – these are so many little things that just get lost online” (Interview 4, person 1). The lack of visual and situational awareness made it difficult for lecturers to gauge how students were doing during courses. They also struggled to interpret certain behaviors in the online environment, such as when a student looked away from the camera. As one explained: “Is he looking away because he’s checking his phone, or is he reflecting internally? [.] In person, if someone is sitting calmly but tapping their foot, I know something’s going on. Online, I can’t see that [.] and in a group, you have a different overall view compared to these boxes” (Interview 11). Additionally, two lecturers with hearing and visual impairments reported significant challenges in the online setting, highlighting that video conferencing tools were not fully accessible for their needs.

It was often only through a lack of interaction or deficiencies in subsequent deliverables, such as case reflections, that lecturers realized students were tired, bored, or unfocused, or that there was no “basic consensus” (Interview 8) on the course topics. This lack of immediate feedback was particularly challenging for the lecturers.

“Maybe in courses on site you notice it a bit more, aha, she’s zoned out or aha, she’s thinking about the curriculum and so on. You can see it a bit, actually you can see it online too, but it’s a bit more complicated and addressing people is one thing, but whether people actually respond is another. It’s so easy to slip away.” (Interview 8)

Lecturers also noted that the “emotional connection” (Interview 2) often got lost in the online setting. The shared experience of being in a physical room, engaging with the course content, and responding spontaneously – such as through laughter – was missing. The digital medium created a sense of distance that was difficult to bridge. As one lecturer put it, “For me, lecturing or teaching is very much a matter of personal contact, and if I have a filter in between, then it just doesn’t quite work.” (Interview 3)

3.3 Reduced spontaneity

Having limited perception of the students in the online setting diminished the spontaneity of lecturers during courses. In face-to-face teaching, frequent feedback and discussions allowed for increased flexibility and spontaneous adjustments to the course flow. However, in the online setting, lecturers found it more challenging to rely on intuition or adapt to the moment, as the connection between students and lecturers was less immediate and tangible.

“You can’t change courses so flexibly and intuitively, […] adapt them to the situation, because the situation is a virtual one anyway and in physical presence, in the real situation in the lecture hall [.] you can also [.] achieve much more with flexibility.” (Interview 6)

Lecturers reported that it was difficult for them to spontaneously tailor the course to the students’ needs. Problems arose, for example, when students were in breakout rooms.

“Let’s assume they take a little longer, when I do it on-site and I notice that two or three in a small group are working very intensively, I give them more time, while when I structure it [in online teaching], I have to [.] close the rooms and suddenly there they are, whether they want to or not [.] when they are in small groups on-site, I can see that and don’t go there right away and [.] interrupt them, but when I go into these rooms, I interrupt them, because they realize at that moment that I am there, and that [.] is a moment which I found unpleasant.” (Interview 5)

Lecturers described that more detailed preparation and structuring was necessary for online courses than for face-to-face courses. They felt it was important to schedule breaks and group work in advance and to organize themselves in such a way that they knew exactly which steps followed next. This preparation created security. It allowed lecturers to focus more on the students during courses while remaining open to changes in the process.

“To be more confident [.] I planned it very precisely [.] I timed it precisely, to give myself confidence, even if I didn’t quite stick to it [.] that’s not the case in face-to-face teaching.” (Interview 5)

One lecturer even saw it as an advantage of online teaching that structuring time was easier and he was able to keep to his schedule better than in person.

3.4 Increased lecturer presence

Almost all lecturers agreed that online teaching was “unilateral” (Interview 1) and required them to be more active and engaged. In face-to-face teaching, lecturers found it easier to keep students engaged and to encourage their active participation. In contrast, online teaching made it easier for students to participate passively or withdraw entirely.

“It requires more presence from the lecturer, because you have to […] encourage the students a lot. There were always students [.] who are difficult to bring in. If a supervisee, someone in self-experience, or someone in a theory seminar, wants to be passive, he can do that more easily. [.] You have to approach him so actively, and almost a bit provocatively, that it is perhaps sometimes an inhibition threshold for us therapists, […] and now you say something, it is a bit gagging, [.] if a student wants to hold back passively, then of course it’s easier for him in an online setting.” (Interview 5)

Lecturers expressed frustration with the lack of feedback from students and the growing difficulty in actively engaging them during online courses. This challenge was heightened when students kept their cameras off, leaving lecturers to interact solely with a photo or name, which created uncertainty about the students’ actual presence. In this context, the online format was often perceived as impersonal, as it failed to foster a sense of commitment.

“The more time passed, the more difficult it was. Because in the beginning I tried to have more contact, but later on you only see a name, sometimes without photos, and I was very frustrated, very frustrated. [.] Materials that I normally use in two weekends, I used in one weekend because there were no questions, there was no communication, and I always had to talk and talk and talk and keep having information [.] it was very difficult for me.” (Interview 1)

Lecturers described how difficult it was to make courses engaging, with some mentioning the risk of “falling into an endless monologue” (Interview 4, person 2), feeling the need to “fill the silence” (Interview 4, person 2) as an “entertainer” (Interview 7), unsure whether they had “an audience at all” (Interview 7).

Conversely, one lecturer found the unilateral setting comfortable when teaching theory. “In part it was as if I was giving a lecture for myself, so I always felt quite secure.” (Interview 10) Similarly, students told lecturers that they were more relaxed in the online setting, “when they give a presentation at home compared to when they stand in front of the group.” (Interview 12)

Two lecturers reported that teaching with a second person was “a huge support” (Interview 4, person 2) in the online setting. Teaching together helped them better handle situations with little feedback from students, especially when none of the students had their video turned on.

The lecturers also emphasized the importance of actively approaching students in online teaching and requesting their participation. However, some lecturers felt that actively prompting student participation conflicted with their teaching style, as it required being more directive than they preferred. This was also the case with video usage – while some lecturers found it helpful to request students turn on their cameras, others did not feel comfortable “to purposely control who is there or not” (Interview 1).

3.5 Limited “we-feeling” and interaction among students

Almost all lecturers highlighted that the online setting made it difficult for students to develop a sense of togetherness within the group of fellow students. “This energy that is inside a room, I missed it incredibly [.] this entire emotional connection was totally lost for me.” (Interview 2) Learning as a social situation changed as each student sat alone in front of their computer. The shared, physical space that facilitated interaction between individual students and in the group was missing, both during and outside of courses.

“There was a certain alienation, [.] there were no more conversations during breaks, there were no more lunches together, everyone was individually in their apartment and thus practically isolated.” (Interview 9)

“People hardly communicated with one another.” (Interview 3)

Lecturers observed a diminished sense of social cohesion. This was particularly problematic “in group self-experience, where something like a we-feeling should be evoked” (Interview 9) and led to students being less willing to share their experiences. Lecturers emphasized that psychotherapy training is fundamentally based on mutual awareness and emotional resonance.

They found it helpful to keep the online room open during breaks and after courses to facilitate informal student interaction. During these times, lecturers would exit the virtual space to allow students to connect freely. This approach was well-received by students.

Additionally, lecturers observed that emotional learning processes often required more time in the online format. It was helpful to reflect collectively on the unique aspects of online learning. “How is it now, with a screen and being in your own space” (Interview 4, person 1), how is it “that we only see each other so little now” (Interview 11).

3.6 Lack of a safe space and professional setting

Another topic that emerged in the interviews was the challenge of creating a safe and professional space in the online environment, particularly during the practical components of the training. Lecturers reported instances where students were not fully present or engaged inappropriately during courses. Examples included students participating in sessions while on the phone, conversing with people in the same room, or even attending from public places. In some cases, students were “outside hiking,” “in the public pool” (Interview 10) or “on a boat” (Interview 2) during courses.

Such behavior was perceived as a disruption, particularly when a confidential atmosphere was essential, such as during self-experience or supervision. To address these challenges, lecturers found it helpful to set conditions for participation in online courses, especially for self-experience and supervision. These conditions emphasized maintaining a confidential and distraction-free environment. One lecturer explicitly reminded students of their responsibility to secure their own space, something she could easily manage in a face-to-face setting but not online:

“Be aware, this is your space, I can’t protect it for you now, if someone enters at university I can protect it. You have to protect the space, is it possible that no one enters this space [.] everyone made sure that they had their protected space, yes, that was very important.” (Interview 11)

Another lecturer suggested that students use headphones if a private room was unavailable, particularly when discussing case studies, to maintain confidentiality and minimize disruptions.

3.7 Confrontation with one’s own appearance

Female lecturers noted a shift in focus during online teaching: whereas they were primarily “centered on the others” (Interview 11) in face-to-face settings, the online format often forced them to confront their own appearance continuously. This constant self-observation led to feelings of insecurity:

“You have to be able to endure seeing yourself all the time [.] this enduring yourself all the time, that’s really tough [.] I think that does something to you, in terms of self-image and self-esteem.” (Interview 4, Person 2)

The visibility of their own image throughout the sessions heightened their awareness of how they appeared to students. Some female lecturers admitted to experiencing doubts about their outward appearance:

“You have to come to terms with that, that you suddenly see every pimple [.] you’re more confronted with age (laughs). I didn’t put on any extra make-up or anything, but I made sure that the lighting is well adjusted.” (Interview 11)

To alleviate the discomfort, some lecturers and students found it helpful to keep their videos on but hide it from their own display. This allowed them to focus on the other participants and strengthened the feeling of being in dialogue with someone:

“In this first group, self-experience group, [.] they turned off the video for themselves so that they weren’t affected by the mirror image and the others stayed [.] it was an interesting suggestion to be freer.” (Interview 11)

In contrast, some male lecturers perceived self-observation as an opportunity for growth. They viewed it as valuable feedback, helping them identify areas for improvement in their teaching style. One male lecturer even had the feeling that the self-observation “rather strengthened his self-confidence” (Interview 7). Another lecturer mentioned that he would appreciate courses being recorded, as this would allow for reviewing them later for self-evaluation or providing feedback in a group of other lecturers.

3.8 “Double focus” in online teaching and dealing with technical challenges

Despite support from the university’s IT department, many lecturers found the transition to online teaching challenging. They had to manage both technical requirements and student engagement simultaneously, a task that required them to maintain a double focus:

“The challenge was [.] managing the technology, managing the technology alone and not having any help, and at the same time [.] focusing on the students, because you focus doubly, you focus on the group that is now online, and you focus on [.] does the technology work, is someone thrown out.” (Interview 5)

Hybrid teaching, which combined online and onsite participants, was particularly demanding. Lecturers described it as “extremely difficult” (Interview 5) and reported that it posed “unique challenges, as it is always difficult [.] to integrate the group or the people who are not part of the face-to-face group well” (Interview 7). Given the complexity and strain, lecturers agreed that hybrid teaching was adopted only out of necessity. In the future, they would prefer to conduct courses either entirely online or entirely face-to-face.

Technical issues added to these challenges, particularly in early stages of the pandemic, with lecturers reporting frequent access problems and system failures. Overall, they expressed a clear preference for Zoom over other tools like MS Teams. Successful online teaching, they emphasized, required “a certain technical understanding” (Interview 3), and those with prior experience using specific online tools found it easier to integrate them into their teaching.

Lecturers appreciated the university’s low-threshold support options. When confronted with technical issues they could not resolve independently, the university’s IT service provided assistance in both course preparation and during courses. This support often ensured the smooth continuation of courses. Lecturers also valued the video tutorials offered by the university, as they allowed for self-study and revisiting specific topics. For the future, they expressed a desire for further professional development opportunities in the area of online teaching. Additionally, two lecturers found it beneficial to teach in pairs, with one managing technical challenges while the other continued conveying the content.

3.9 Negative health effects and concentration difficulties

Lecturers reported that the online format posed physical challenges particularly due to prolonged periods of sitting in front of the computer, which led to complaints such as back pain. In longer courses, the online setting became physically taxing, and some lecturers expressed concerns about potential long-term health effects.

“At one point, I thought I had a herniated disk because I had so much pain [.] if you teach one hour or so, I don’t think it’s that dramatic, but teaching 16 units in a row online, I find incredibly exhausting.” (Interview 12)

The same lecturer compared the experience to being “like a caged animal” and mentioned she would “walk in circles” around the park during breaks to counteract the hours of sitting. Similarly, another lecturer reported, “I love the situation where you can get up under the pretext of having to urinate and go outside and move.” (Interview 3)

In addition to physical discomfort, lecturers also reported difficulty concentrating in the online setting. It was “much, much more exhausting to stay focused” (Interview 12), while another lecturer noted, “all that sitting in front of the computer [.] where you have to concentrate intensely and stare at the screen, that really takes it out of you” (Interview 4, Person 2).

Lecturers found that longer courses particularly strained both the body and concentration, making shorter sessions more suited to the online format. To mitigate these effects, one lecturer implemented physical or relaxation exercises during longer sessions. Others opted to teach from their office or practice, rather than from home, in order to create a clear boundary between work and personal life. Teaching from a professional setting “was extremely important” (Interview 4, Person 1) to them and they expressed a strong dislike for having “to sit at home” (Interview 4, Person 2) when teaching. As one lecturer reflected, “I was always dressed, not in sweatpants. I needed that for myself, yes, to be properly dressed because that was my professional outfit.” (Interview 11)

3.10 Suitability of online teaching by course type

Regarding the suitability of online teaching for specific areas of the curriculum, lecturers found that online teaching was well-suited for theoretical and research-oriented courses. Online supervision and individual self-experience were considered “unproblematic,” even if less optimal compared to in-person sessions. However, lecturers viewed videoconferencing as inadequate for teaching modality-specific methods and group self-experience.

3.10.1 Theoretical foundations and research methods

The lecturers agreed that online teaching is suitable for theoretical courses, including “scientific knowledge” (Interview 9), “theory” (Interview 10), “cognitive content” (Interview 7) and “theoretical craft” (Interview 5), and courses on research methods.

“I believe that online teaching, and the online setting in general, works great where it’s really only or at least mainly about talking, where you don’t necessarily need physical presence, that is, where it doesn’t go beyond language.” (Interview 4, Person 2)

Online settings simplified teaching activities involving technology, such as teaching statistics or guiding students through scientific databases. On-site teaching, in contrast, required additional logistical support, such as ensuring “that a computer room is available, or [.] that the students bring all the devices they need, which is often not so easy” (Interview 7).

Lecturers reported satisfactory exam results and very positive experiences with innovative course designs featuring group work, work packages, and self-study with Moodle, noting that “the pandemic really made it [online teaching] work” (Interview 4, Person 2). At least one theoretical course continued to be held online even after the COVID-19 measures ended.

3.10.2 Practice-oriented courses

Overall, lecturers felt that it was impossible to develop the practical skills necessary for successful psychotherapeutic work through online teaching alone. Most of them emphasized that teaching “practical skills” (Interview 10) and social skills, which are essential for psychotherapeutic work, requires a face-to-face setting. In particular, one lecturer stressed that “relational skills, [.] the ability to build relationships and to transform these relationships into healing and impactful relationships” while “maintaining the right distance” (Interview 2) cannot be acquired online. He highlighted that students need to acquire these skills in person, by building relationships with their fellow students and lecturers.

“Ultimately, online [.] cannot fully replace face-to-face teaching because it is not possible to form relationships, friendships or relationships of trust online. Yet psychotherapy in itself is precisely this: building relationships of trust. How are our students supposed to learn to build relationships of trust if they don’t experience for themselves how this works during their studies, if the lecturers are impersonal images on a screen rather than tangible people made of flesh and blood?” (Interview 2)

Another lecturer summarized, “psychological education, that is, mental, emotional education, is less well promoted by online teaching than by face-to-face teaching” (Interview 9).

In terms of didactic possibilities, lecturers reported that “hands-on practice of psychotherapeutic situations” was “very difficult” (Interview 10) and in some cases “impossible” (Interview 2) to do online.

“Intervention technique [.] also involves perceiving the other person in the room – reading their body language, facial expressions, gestures, a certain atmosphere that emerges in the psychotherapeutic space hard to describe with theoretical constructs in an online medium. [.] Sensing the other person in the therapeutic situation is something that, in my opinion, is difficult to do in an online setting.” (Interview 10)

However, they acknowledged that online teaching might be suitable for teaching skills such as “active listening” and “questioning techniques” (Interview 5).

In order to deliver the required competencies despite the COVID-19 regulations, lecturers found “ways around” the restrictions of in-person teaching. For example, one course was delivered online, but students met face-to-face in triads when meetings of three people were allowed.

3.10.3 Group self-experience

Carrying out group self-experience, which involves deep personal processes and interactions among students, was experienced as particularly challenging in the online setting. Lecturers reported that students often participated passively, and fostering meaningful interaction among them proved difficult. Breakout rooms were mentioned as a facilitating tool, but lecturers found them to provide only limited support.

“We introduced a topic, and then they [the students] went into breakout rooms to discuss with each other. But then again, when it was time for feedback, I noticed how the others were gradually falling asleep. It wasn’t possible to have a discussion.” (Interview 2)

One lecturer shared his experience of how tensions between group members “intensified through these online sessions,” leading to a “pretty frosty atmosphere” and leaving participants with an “uncomfortable feeling” – an outcome he had “never experienced in group self-experience before” (Interview 9). As a result, the group decided to stop further online self-experience sessions and to wait about a year until they could meet again in person. Only then were they able to resolve the conflicts.

Particularly for group self-experience, many lecturers felt the need to find ways to ensure that teaching could take place in person, or at least in a hybrid format, even during the pandemic. They felt that group self-experience courses underlined the importance of physical presence for meaningful interaction and emotional support.

3.10.4 Individual self-experience

In contrast to group settings, online self-experience in individual settings was generally perceived more positively by lecturers, although they still noted differences compared to face-to-face sessions. While “therapy and training analysis [.] are about a two-person relationship and primarily about the student or the patient” and the “shared experience” in the room is “advantageous,” one lecturer felt that the “training analyses and therapies that were already ongoing” were “certainly not a problem” (Interview 9) when conducted online. Another lecturer emphasized that “knowing each other [already] was the decisive factor” (Interview 2) for successful online sessions.

The online format brought both advantages, such as temporal and spatial flexibility, and disadvantages, including the loss of time structures and the absence of a safe space, for individual self-experience.

“With those I knew, it went relatively well because there was a much more active exchange possible online, in the sense of day, night, at any time, I wasn’t tied to whether my practice was available or not [.] on the other hand, my structures somehow fell a bit apart [.] if I already knew the people [.] even there, disruptions were often unavoidable.” (Interview 2)

Another lecturer shared that while she prefers in person individual self-experience sessions, she was “really fine with holding sessions via Zoom, for example if someone was further away or ill” (Interview 12). This view was shared by the other lecturers.

A psychoanalytic lecturer reflected on the use of telephone sessions, noting that “some patients were also able to talk about things precisely because we were more at a distance,” but qualified this by adding, “whether we could continue to work with it is another question” (Interview 11). Another psychoanalyst similarly observed that the absence of eye contact could be beneficial for psychoanalytic work. In some cases, individual self-experience sessions conducted via telephone appeared to enhance patients’ ability to connect with themselves and to address issues more openly.

3.10.5 Supervision

Lecturers reported particularly positive experiences with online supervision. One lecturer who lived outside Vienna reported that although he conducts training analysis sessions in-person, the supervision sessions are now exclusively held online at the request of his students. One of the reasons why this works so well, according to the lecturer, is that “it is less [.] about experiencing and working through a life story together, but really more about professional knowledge” (Interview 9).

“Of course, personal problems of the supervisee are also touched upon, when someone is, let’s say, in a countertransference trap, if they are upset about the patient [.] but this too is probably more possible in the online setting, because it is about a third party, it is about a third party and the isolation caused by the online setting should not be too much of a problem.” (Interview 9)

Another lecturer similarly noted that online “supervision for advanced students” was “not a problem” because it was “more about concrete knowledge transfer” (Interview 8). Two interviewees had already conducted online supervision prior to the pandemic, underlining the lecturers’ openness to teach online for accessibility reasons.

4 Discussion

The present qualitative study investigated how lecturers in Psychotherapy Science at the SFU Vienna experienced online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. To briefly summarize the findings, most lecturers reported similar overall experiences with the online format, describing it as both challenging and exhausting. Due to the limitations of non-verbal communication, they faced difficulties in perceiving and responding to their students’ needs. The lack of opportunities for mutual attunement in the relationship resulted in a loss of connectedness, undermining interactions between lecturers and students as well as among students themselves. Furthermore, the online environment created barriers to sustained attention for both lecturers and students. The dual focus on managing the setting and teaching made it difficult to maintain an active presence and foster engagement. Student participation declined over the course of the pandemic, and the online teaching environment was often perceived as “unilateral.” Finally, the study highlighted that online teaching can be suitable for certain components of psychotherapy training but is not appropriate for all types of courses. While lecturers valued online tools as useful for certain aspects of teaching, they argued that core relational skills can only be effectively taught face-to-face.

4.1 Limited perception and reduced connectedness

The online teaching environment limited the lecturers’ ability to perceive and respond effectively to their students. In particular, the absence of non-verbal cues made it difficult to gauge students’ engagement and adapt spontaneously to their needs. Struggles to resonate with each other during the courses can be seen as indicative of more distant relationships in online settings. Similarly, Lucas and Vicente (2023), who surveyed 1,144 teachers about online teaching, argue that the lack of engagement is partly due to the lack of human and social contact inherent in these environments. These findings echo conclusions drawn in the context of remote psychotherapy, where the absence of face-to-face contact has been shown to disrupt relationship depth and mutual attunement-processes which rely heavily on physical presence and non-verbal communication (Hickey and McAleer, 2017; Roesler, 2017; Höfner et al., 2021; Jesser et al., 2022). The parallels between teaching and psychotherapy highlight the critical role of embodied interaction in fostering meaningful connections.

Beyond lecturer-student relationships, the interviews revealed concerns about students’ connectedness with their peers. Participants noted that the online format could weaken students’ sense of belonging and shared identity. This observation is consistent with Griesehop and Bauer’s (2017) findings that online teaching can impede the formation of campus identity. Similarly, Akgün et al. (2023) reported that students felt a diminished collective “we” during early phases of online teaching. A reduction in social cohesion may not only impact personal relationships but also have professional implications. Militello’s (2021) study on networking during the pandemic demonstrated that online communication significantly hindered the establishment of new professional connections. Taken together, these insights suggest that the online teaching environment may limit both immediate interpersonal dynamics and long-term formation of supportive academic and professional networks.

4.2 Challenges of online presence and engagement

The online teaching environment brought significant challenges to maintaining focus and engagement for both lecturers and students. Prolonged periods in front of a screen were described as exhausting, resulting in physical discomfort and difficulties maintaining concentration. Female lecturers, in particular, found the constant awareness of their own appearance on camera uncomfortable. Technical and organizational demands further complicated efforts to maintain attention and presence, requiring lecturers to keep a “double focus”: they needed to engage meaningfully with students while simultaneously managing the technical aspects of the online format. As previous studies have shown (Mishra et al., 2020; Ulla and Perales, 2022), frequent technical difficulties disrupted the flow of teaching, forcing lecturers to shift their attention from pedagogical to technical tasks.

A pervasive issue for lecturers was the uncertainty about students’ genuine presence, particularly when cameras were off, and interactions felt one-sided. Students’ perspectives on online teaching in psychotherapy training confirm that they were distracted more easily and less focused when their cameras were off (Akgün et al., 2023). However, even with cameras on, engagement in online teaching was perceived as limited, with feedback, discussions, and active participation being reduced. Other research also showed that motivation and cognitive engagement decreased with the transition to online teaching (Patricia Aguilera-Hermida, 2020).

Findings on the challenges of online presence and engagement in teaching are consistent with research on online psychotherapy, where psychotherapists also reported increased effort to maintain focus (Mirkin, 2011), heightened distractions for both themselves and their patients, and disruptions to the therapeutic process due to technical issues (Backhaus et al., 2012; Huscsava et al., 2020; Jesser et al., 2022). The shared insights from both fields - online teaching and online psychotherapy - point to an intricate interplay between relational dynamics and the digital setting. They reveal how the online format can create barriers to sustained attention and reciprocal engagement, ultimately diminishing the quality of interaction in online learning environments.

4.3 Online format dependent on course type

The results of our study clearly demonstrate that online teaching works reasonably well in some areas, while being perceived as unsuitable in others. Theoretical foundations and research methods constitute one pillar of psychotherapy training. In this domain, lecturers reported positive experiences with the online format. Course content could be effectively delivered, and the possibilities offered by digital tools and applications (e.g., learning platforms and breakout rooms) were leveraged to engage students and encourage active participation.

However, therapeutic practice requires more than theoretical knowledge and technical skills; it also demands sensitivity to and expression of emotional processes (Heinonen and Nissen-Lie, 2019; Oerter and Weber, 1975). Socio-emotional learning, defined as the process through which students acquire competencies such as recognizing emotional responses, reacting to and reflecting on feelings, organizing emotional experiences, and integrating value systems (Krathwohl et al., 1964; McKown, 2019), is essential in psychotherapy training. Achieving socio-emotional learning outcomes is a cornerstone of the SFU curriculum. These outcomes are particularly emphasized in practice-oriented courses, group and individual self-experience, and supervision.

Research indicates that socio-emotional learning heavily depends on perceiving non-verbal cues and establishing a sense of connection with others (Levitt et al., 2022). Loewenthal and Snell (2008) highlight the importance of the learning community as a “container for growth and learning” (Loewenthal and Snell, 2008; p. 39). They argue that emotional learning cannot be “primarily skills- or knowledge-based but begins with questioning what it means to be in the world of and with others” (Loewenthal and Snell, 2008; p. 39).

Indeed, the results of our study revealed that practice-oriented courses and group self-experience were negatively affected by the online format. Lecturers emphasized that these courses rely on face-to-face interaction, the ability to perceive and sense the presence of the other person, and a shared physical space. The atmosphere created by being together in one room cannot be replicated online.

Existing research supports this observation, suggesting that not all course types or subjects benefit equally from an online format. Akgün et al. (2023) found that psychotherapy students perceived a purely online format as suboptimal for courses requiring interpersonal contact. Similarly, Hickey and McAleer (2017) argued that courses aiming to teach nuanced interpersonal aspects of psychotherapeutic practice are less suited for online formats. Practical classes requiring active teacher demonstrations, as well as excursions and reflective exercises, revealed limits of the online setting (Malewski et al., 2021; Mishra et al., 2020).

However, lecturers in our study highlighted that, in contrast to group self-experience, the online format was reasonably well suited for individual self-experience. This aligns with findings from studies on remote psychotherapy, which show that a positive and stable therapeutic relationship can also be achieved online (Knaevelsrud and Maercker, 2007; Mitchell, 2020). Roesler (2017) argues that such relationships are more likely to be established online when patients are capable of forming a secure bond with the therapist. This assumption can reasonably be made for psychotherapy students, as multiple interviews with experienced psychotherapists before being admitted to the training program ensure their ability to build trust and connection.

Of all practical components, supervision was considered most suitable for the online setting by the lecturers. This was attributed to it involving less emotional learning and more concrete knowledge transfer. These findings align well with a study by Gordon et al. (2015) who evaluated expert opinions on psychodynamic teaching, supervision, and therapy via videoconferencing. On a scale from “much less effective” to “no difference,” teaching, supervision, and therapy were all rated “slightly less effective” than face-to-face sessions, with supervision being rated as significantly more effective than teaching and therapy via videoconferencing. Moreover, participants rated that videoconference therapy is indicated when high-quality in person treatment is not accessible. Similarly, the lecturers in our study were open to conducting practical components of training online or in a hybrid format to ensure accessibility.

4.4 Potential strategies for enhancing online teaching and further perspectives

Despite the aforementioned challenges, our study also revealed opportunities for online teaching in psychotherapy training and strategies to overcome some of the mentioned difficulties. By emphasizing positive aspects and strategically applying these approaches, digital formats can be integrated into teaching in a meaningful and innovative way, particularly for those components of the psychotherapy curriculum identified by lecturers.

One notable advantage of online teaching is the increased convenience and improved time management it offers for both students and lecturers. Moreover, lecturers in our study observed that students felt more comfortable presenting online, as the home environment often reduced anxiety during presentations. However, while such an environment can help alleviate nervousness, it is essential to balance this with addressing avoidance behaviors (Lazos and Kredentser, 2021; Schaffler et al., 2023; Sobotka et al., 2024).

To fully realize the benefits of online teaching, a thoughtful and strategic approach to course design plays a crucial role (Baran et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2018; Van Wart et al., 2020). Research underscores that well-structured online courses can enhance engagement, build a sense of community, and promote learning outcomes. Effective course design should integrate dimensions of teaching presence, instructional support, interaction, connectedness, collaboration, and communication (Lee et al., 2011; Van Wart et al., 2020; Lucas and Vicente, 2023). In our study, lecturers reported positive experiences with interactive elements such as breakout rooms for small group discussions, group work, or role-play exercises to simulate therapeutic scenarios. They incorporated regular and movement breaks to alleviate cognitive and physical fatigue, set clear participation guidelines (e.g., requiring cameras to be on), addressed students personally during discussions, and fostered informal spaces for interaction before and after courses. These strategies not only enhanced the online learning experience but also addressed the relational dimension central to psychotherapy training.

Additionally, the adoption of online teaching practices requires comprehensive training for lecturers in pedagogical strategies suitable for the modality (Lucas and Vicente, 2023). The transition to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic often involved emergency remote teaching, characterized by improvised strategies designed to meet immediate needs (Hodges et al., 2020). As in many other higher education settings, lecturers at SFU had little if any prior experience with online teaching. Reports from various higher education institutions suggest a growing interest in maintaining online teaching formats even post-pandemic, provided that lecturers are adequately supported and trained (Guppy et al., 2022; Budde and Friedrich, 2024).

Our findings underscore blended learning approaches, which integrate the flexibility of online teaching and the relational depth of in-person learning, to hold promise for future psychotherapy training. By leveraging the strengths of both formats, such approaches can enhance accessibility while maintaining the experiential richness essential to developing therapeutic competencies.

4.5 Limitations and future directions

A limitation of this study lies in the structured nature of the interviews, which allowed limited scope for deeper exploration. The relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the findings. However, the heterogeneous sample offers a nuanced perspective on teaching experiences across various components of the curriculum.

The interviews were conducted between November 2022 and December 2023. Since then, lecturers’ technical expertise in online teaching may have improved, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Furthermore, the study focuses on emergency remote teaching implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may differ from well-planned online teaching experiences. Future evaluations must recognize these distinctions to avoid conflating temporary crisis responses with intentionally designed online education (Hodges et al., 2020).

Lastly, the study did not specifically address the impact of online teaching on learning objectives or therapeutic skills development, and how these evolved over time. This aspect, along with the long-term effects of online teaching on both lecturers’ methods and students’ competencies, should be explored in future research, particularly in the context of practical psychotherapy training.

5 Conclusion

This study highlights the complex experiences of Psychotherapy Science lecturers with online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. While online teaching offered flexibility and worked well for theoretical components, individual self-experience, and supervision, significant challenges arose in fostering engagement, sustaining attention, and maintaining relational depth. The absence of non-verbal cues and shared physical spaces hindered connectedness and socio-emotional learning, particularly in practice-oriented courses and group self-experience.

Despite these challenges, the findings suggest that online formats can complement psychotherapy training when applied selectively and supported by thoughtful course design and lecturer training. A blended learning approach, integrating online and in-person teaching, appears most promising for balancing flexibility with the relational and experiential needs of psychotherapy training. Future research should focus on long-term adaptations and distinctions between emergency remote teaching and well-planned online learning.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Sigmund Freud Private University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because participants provided oral consent that was recorded on audio tape.

Author contributions

CS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. NP: Writing – original draft. AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. VS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ET: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. JF: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. AJ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating lecturers for their time and efforts.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1573005/full#supplementary-material

References

Akgün, A., Roxane, F., Jutta, F., and Elitsa, T. (2023). Auswirkungen der online-lehre auf die psychotherapieausbildung. Eine mixed-method-studie an der sigmund freud privatuniversität wien. Psychotherapie Forum 27, 38–45. doi: 10.1007/s00729-023-00223-1

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 10:16. doi: 10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Aucejo, E., French, J., Ugalde Araya, M., and Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Public Econ. 191:104271. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

Backhaus, A., Agha, Z., Maglione, M., Repp, A., Ross, B., Zuest, D., et al. (2012). Videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review. Psychol. Serv. 9, 111–131. doi: 10.1037/a0027924

Baran, E., Correia, P., and Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: Critical analysis of the literature on the roles and competencies of online teachers. Distance Educ. 32, 421–439. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2011.610293

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706QP063OA

Budde, J., and Friedrich, J. -D. (2024). Monitor digitalisierung 360°. Wo stehen die deutschen Hochschulen? Working Paper No. 83. Berlin: Hochschulforum Digitalisierung.

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. J. Positive Psychol. 12, 297–298. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Ferrel, M., and Ryan, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus 12:e7492. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7492

Gordon, R., Wang, X., and Tune, J. (2015). Comparing psychodynamic teaching, supervision, and psychotherapy over videoconferencing technology with chinese students. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 43, 585–599. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2015.43.4.585

Griesehop, H., and Bauer, E. (2017). Lehren Und Lernen Online. Lehren Und Lernen Online. Berlin: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-15797-5

Guppy, N., Verpoorten, D., Boud, D., Lin, L., Tai, J., and Bartolic, S. (2022). The post-COVID-19 future of digital learning in higher education: Views from educators, students, and other professionals in six countries. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 53, 1750–1765. doi: 10.1111/BJET.13212

Heinonen, E., and Nissen-Lie, H. (2019). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychother. Res. 30, 417–432. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366

Hickey, C., and McAleer, S. (2017). Competence in psychotherapy: The role of E-learning. Acad Psychiatry 41, 20–23. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0443-5

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Available online at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed May 4, 2025).

Höfner, C., Mantl, G., Korunka, C., and Straßer, M. (2021). Psychotherapie in zeiten der Covid-19-pandemie: Veränderung der arbeitsbedingungen in der versorgungspraxis. Feedback. Zeitschrift Für Gruppentherapie Und Beratung 2021, 23–37.

Huscsava, M. M., Plener, P., and Kothgassner, O. (2020). Teletherapy for adolescent psychiatric outpatients: The soaring flight of so far idle technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital Psychol. 1, 32–35. doi: 10.24989/DP.V1I2.1867

Jesser, A., Muckenhuber, J., and Lunglmayr, B. (2022). Psychodynamic therapist’s subjective experiences with remote psychotherapy during the COVID-19-Pandemic-A qualitative study with therapists practicing guided affective imagery, hypnosis and autogenous relaxation. Front. Psychol. 12:777102. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.777102

Knaevelsrud, C., and Maercker, A. (2007). Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-13

Krammer, G., Pflanzl, B., and Matischek-Jauk, M. (2020). [Aspects of online teaching and their relation to positive experience and motivation among teacher education students: Mixed-method findings at the beginning of COVID-19]. Z Bild Forsch. 10, 337–375. doi: 10.1007/s35834-020-00283-2

Krathwohl, D., Bloom, H., and Maria, B. (1964). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Lazos, G., and Kredentser, O. (2021). Resilience of psychotherapists and the relationship between their personal and professional characteristics. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 10:162. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20211006.15

Lee, S., Srinivasan, S., Trail, T., Lewis, D., and Lopez, S. (2011). Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning. Int. High. Educ. 14, 158–163. doi: 10.1016/J.IHEDUC.2011.04.001

Levitt, H., Collins, K., Morrill, Z., Gorman, K., Ipekci, B., Grabowski, L., et al. (2022). Learning clinical and cultural empathy: A call for a multidimensional approach to empathy-focused psychotherapy training. J. Contemp. Psychother. 52, 267–279. doi: 10.1007/s10879-022-09541-y

Loewenthal, D., and Snell, R. (2008). The learning community and emotional learning in a university-based training of counsellors and psychotherapists. Int. J. Adv. Counselling 30, 38–51. doi: 10.1007/S10447-007-9043-8/METRICS

Lucas, M., and Vicente, P. N. A. (2023). double-edged sword: Teachers’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of online teaching and learning in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 5083–5103. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11363-3

Malewski, S., Engelmann, S., and Peppel, L. (2021). Erleben, herausforderungen und zukünftige lehrszenarien in der online-lehre. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift Für Theorie Und Praxis Der Medienbildung 40, 97–117. doi: 10.21240/mpaed/40/2021.11.12.x

Martin, F., Wang, C., and Sadaf, A. (2018). Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Int. High. Educ. 37, 52–65. doi: 10.1016/J.IHEDUC.2018.01.003

McKown, C. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in the applied assessment of student social and emotional learning. Educ. Psychol. 54, 205–221. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1614446

Mikkonen, K., Helminen, E., Saarni, S., and Saarni, S. (2024). Learning outcomes of e-learning in psychotherapy training and comparison with conventional training methods: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 26:e54473. doi: 10.2196/54473

Militello, J. (2021). Networking in the time of COVID. Languages 6:92. doi: 10.3390/languages6020092

Mirkin, M. (2011). Telephone analysis: Compromised treatment or an interesting opportunity? Psychoanal. Q. 80, 643–670. doi: 10.1002/j.2167-4086.2011.tb00100.x

Mishra, L., Gupta, T., and Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 1:100012. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

Mitchell, E. (2020). Much more than second best”: Therapists’ experiences of videoconferencing psychotherapy. Eur. J. Qual. Res. Psychother. 10, 121–135.

Oerter, R., and Weber, E. (1975). Der Aspekt des Emotionalen in Unterricht und Erziehung. Germany: Auer.

Patricia Aguilera-Hermida, A. (2020). College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 1:100011. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011

Roesler, C. (2017). Tele-analysis: The use of media technology in psychotherapy and its impact on the therapeutic relationship. J. Anal. Psychol. 62, 372–394. doi: 10.1111/1468-5922.12317

Schaffler, Y., Bauer, M., Schein, B., Jesser, A., Probst, T., Pieh, C., et al. (2023). Understanding pandemic resilience: A mixed-methods exploration of burdens, resources, and determinants of good or poor well-being among Austrian psychotherapists. Front. Public Health 11:1216833. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1216833

Sobotka, M., Kern, T., Haider, K., Dale, R., Wöhrer, V., Pieh, C., et al. (2024). School students’ burdens and resources after 2 years of COVID-19 in Austria: A qualitative study using content analysis. Front. Public Health 12:1327999. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1327999

Taubner, S., and Evers, O. (2020). “Der effiziente therapeut in therapie und ausbildung,” in Effizienz und effektivität in der psychotherapie, 1st Edn, eds S. Trautmann-Voigt and B. Voigt (Psychosozial-Verlag), 205–226. doi: 10.30820/9783837976007

Ulla, M. B., and Perales, W. F. (2022). Hybrid teaching: Conceptualization through practice for the post COVID19 pandemic education. Front. Educ. 7:924594. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.924594

Keywords: psychotherapy training research, online teaching, blended learning, psychotherapy training, qualitative research

Citation: Springinsfeld C, Pfatrisch N, Akgün A, Scholtus V, Tilkidzhieva E, Fiegl J and Jesser A (2025) Online teaching in psychotherapy training: a qualitative study revealing challenges and strategies from lecturers’ perspectives. Front. Educ. 10:1573005. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1573005

Received: 08 February 2025; Accepted: 28 April 2025;

Published: 15 May 2025.

Edited by:

José Gijón Puerta, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Robert M. Gordon, Institute for Advanced Psychological Training, United StatesMarcela Tiburcio, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente Muñiz (INPRFM), Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Springinsfeld, Pfatrisch, Akgün, Scholtus, Tilkidzhieva, Fiegl and Jesser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Jesser, YW5kcmVhLmplc3NlckBzZnUuYWMuYXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Constanze Springinsfeld

Constanze Springinsfeld Nina Pfatrisch†

Nina Pfatrisch† Andrea Jesser

Andrea Jesser