- Department of Social Studies Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

This study addresses prejudice and discrimination against ethnic minorities and examines their causes and solutions within the social studies classroom. Grounded on Social Identity Theory, this study highlights the significance of teaching students about multiple social identities to reduce bias. To enhance classroom applicability, this study proposes a teaching model for social studies curricula aligned with the inquiry design model (IDM) of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). Also, it presents a pedagogical format for high school instruction, which adheres to the C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards in the United States and the revised 2022 Social studies curriculum in South Korea. This model will empower students to contribute to building a society where diverse backgrounds are acknowledged and respected.

1 Introduction

1.1 Necessity and purpose of the study

In South Korea (hereafter Korea), the growing demand for foreign labor and marriages has led to a steady increase in the racially and ethnically diverse population. However, negative attitudes and hate speech towards ethnic minorities have also risen, fueling social conflict and tension. Protests accepting refugees from various conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War, the Afghan conflict, and the Russia–Ukrainian War has emerged, reflecting resistance to multicultural integration. Additionally, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, widespread petitions called for a ban on Chinese people from entering Korea. A controversy surrounding Korean high school students using blackface to recreate the “Dancing Pallbearers”1 meme led to online attacks against an African influencer who criticized their actions.

Hate speech against ethnic minorities is not confined to Korea. During the 2024 U. S. presidential election, hate rhetoric and anti-immigrant sentiment spread across social media, while the Israel–Hamas war intensified the prevalence of anti-Semitic and anti-Islamic hate speech. Such ethnic hatred content, which vilifies and discriminates against specific groups, has fuelled xenophobia. These messages reproduce and amplify conflicts within society, providing justifications for hate crimes against members of ethnic groups (Castaño-Pulgarín et al., 2021; Evolvi, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Watanabe et al., 2018).

To better understand the underlying mechanisms of such societal tensions, it is important to examine how ethnic hatred emerges. Social identity theory (SIT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding intergroup dynamics, categorizing the roots of prejudice and discrimination (Turner and Reynolds, 2012). While Realistic Conflict Theory (Sherif et al., 1961) emphasizes competition over scarce resources as a primary cause of intergroup conflict, Social Identity Theory suggests that such intergroup conflict can arise without direct competition for resources. To maintain positive social identities, people tend to favor members of their in-group (in-group favoritism) and negatively evaluating out-group members (out-group discrimination). These biased attitudes form the basis for discrimination and prejudice within society (Brewer and Gaertner, 2002).

However, individuals possess multiple social identities, shaped by nationality, ethnicity, religion, occupation and other factors, and nothing can be depreciated. Prejudice against ethnic groups not only threatens diversity and inclusivity, core democratic values, but also erodes opportunities to appreciate and celebrate a wide range of cultures (Banks, 2018).

This study raises the severity of ethnic hatred and proposes a social studies instructional model grounded in SIT. To ensure practical classroom application, this study presents a sample pedagogical format aligned with the inquiry design model (IDM) of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). This model adheres to the C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards in the United States and the 2022 revised Social studies curriculum in Korea.

Previous studies have mainly focused on negative attitudes and hate speech towards ethnic minorities from a macro perspective. UNESCO has proposed media and information literacy initiatives to combat ethnic hate speech (Gagliardone et al., 2015) and has published a guide for policymakers to assist them in developing strategies related to policies, curricula, and teacher training (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, 2023). The Council of Europe has also published a guide to human rights education that presents various classroom activities (Keen et al., 2020). In addition, numerous Korean and international nonprofit organizations implement various educational programs aimed at countering ethnic hate speech (Kim et al., 2019).

The aforementioned studies are significant in that they introduce various educational initiatives and action plans for preventing ethnic discrimination and online hate speech. However, few studies have presented lesson plans that are applicable to high school students or that can be integrated into national curricula (Eun, 2023; Kysia, 2024). Moreover, existing teaching models often fall short in guiding students to understand the root causes of ethnic hatred or in providing inquiry-based approaches to address it.

In summary, this study aims to reduce negative biases toward ethnic minorities by proposing a social studies instructional model that is both theoretically grounded and practically applicable in classroom settings. Aligned with national curricula, the model provides students with structured learning experiences to explore the causes and pedagogical approaches of ethnic hatred. Designed for adaptability, it offers a framework that can be implemented across diverse educational contexts worldwide. Ultimately, this model will empower students to contribute to building a society where diverse backgrounds are acknowledged and respected.

1.2 Method of research

The purpose of this study is to highlight the importance of teaching students about multiple social identities in addressing the issue of ethnic hatred and to proposes a teaching model for social studies curricula. To strengthen the theoretical basis and practical applicability of this model, this study was conducted using the following method.

First, previous studies were examined by referring to the procedures and elements emphasized in the research synthesis methodology (Cooper et al., 2019). This paper aims to reduce prejudice against ethnic minority groups by recognizing multiple social identities, and therefore, the researchers systematically reviewed existing studies according to the following procedures. First, using the academic databases such as Education Resources Information Center2 and web search engines, such as Google Scholar, the researchers searched for several key phrases, including “social identity theory” and “ethnicity,” “social identity theory” and “multicultural education,” as well as “multiple social identities” and “social studies.” For this research, studies in the disciplines of early childhood education, adult education and experimental social psychology were excluded because these disciplines are rather distant from elementary and secondary education. Criteria for selecting the literature are following. “Does the study focus on elementary, middle, or high school students or teachers?,” “Was the study conducted in a school context?,” and “Are the results of this study applicable to social studies instruction?” Next, the researchers selected studies with titles and content that were closely related to our research topic. Finally, the researchers analyzed the core content of the studies in terms of each subtopic item. Moreover, on the basis of this analysis, the researchers inferred the practical implications of applying the content in a classroom setting.

Second, based on the literature review, the researchers developed a social studies instructional model that addresses the issue of online hate speech directed towards ethnic minorities. To ensure that the instructional model can be utilized in actual classrooms, the researchers created a sample instructional model in accordance with the inquiry design model (IDM) of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). This instruction model follows an inquiry process that encompasses four dimensions. The instructional model facilitates student exploration of the problematic phenomenon of ethnic hatred and applies social identity theory (SIT) to the identification of causes and educational approaches.

Third, the study presents an example of the social studies instruction model. It is designed for high school level implementation within the 2022 revised national curriculum for social studies in Korea and the College, Career and Civic Life Framework for Social Studies State Standards (C3 Framework) developed by the NCSS in the United States. Furthermore, this model offers a framework that can be adapted for implementation in diverse educational contexts worldwide.

2 Ethnic hatred situation in South Korea

In 2024, the number of foreign nationals residing in Korea is expected to reach 2.570 million, exceeding 5% of the total population. According to the OECD definition, this makes Korea a multiracial and multicultural nation (Statistics Korea, 2023). While the multicultural composition of Korean society has grown, this shift has also led to discomfort among the population. According to the results of the World Value Survey Wave 7 (2017–2022), Koreans hold rather negative attitudes towards ethnic groups compared to citizens of other countries. Approximately 22% of Koreans responded, “I would not like to have immigrants/foreign workers as neighbors.” This percentage is significantly higher than in Germany (3.9%) and the United States (8.0%). Only 19.1% of Koreans answered, “I trust people of other nationalities.” This result was also lower than Germany (58.1%) and the United States (73.2%). These survey results indicate that Korean have difficulty accepting people of non-Korean ethnic backgrounds into Korean society.

Since the 2000s, anti-multicultural, anti-foreigner and xenophobic discourses have emerged in Korea. In particular, the arrival of Yemeni refugees on Jeju Island in 2018 triggered overt displays of hatred directed towards ethnic minorities, with the international community taking note of the situation in Korea. Moreover, anti-refugee rallies have been held across the country and people posted hateful messages about refugees on social media platforms. Yemeni refugees were stigmatized as potential criminals and terrorists due to their Islamic religious background and messages were circulated online warning that their arrival would threaten the safety and security of Korean society. These movements exacerbated feelings of fear and disgust towards ethnic minorities and the anti-refugee movement was even glorified as a patriotic movement seeking to defend and protect Korea (Kim et al., 2019). That is, Korean society is characterized by a group identity rooted in a sense of ethnic homogeneity. It also exhibits xenophobia based on the belief that contact with groups from different ethnic backgrounds poses a serious threat to society. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has warned that the atmosphere of hatred and distrust towards ethnic minorities in Korean society has reached a serious level and recommended that legal and institutional frameworks be established immediately. In its deliberations, the committee noted the need to take decisive action against racist hate speech and monitor mass media, the internet and social media while also identifying and punishing individuals and organizations that propagate ideas based on racial superiority or incite hatred against foreigners. It also called for proactive interventions to combat the spread of ethnic hatred, especially in online spaces (United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 2019).

3 Ethnic hatred based on social identity theory

3.1 Prejudice and social identities

One’s personal identity begins with the question, “Who am I?” As social beings, individuals do not independently form their own identities but rather explore their identities within social relationships (Erikson, 1968). Social identity refers to one’s sense of belonging to a particular social group, as well as the emotions, values and other factors associated with this belongingness –as part of the self-concept (Abrams and Hogg, 2010; Tajfel, 1972).

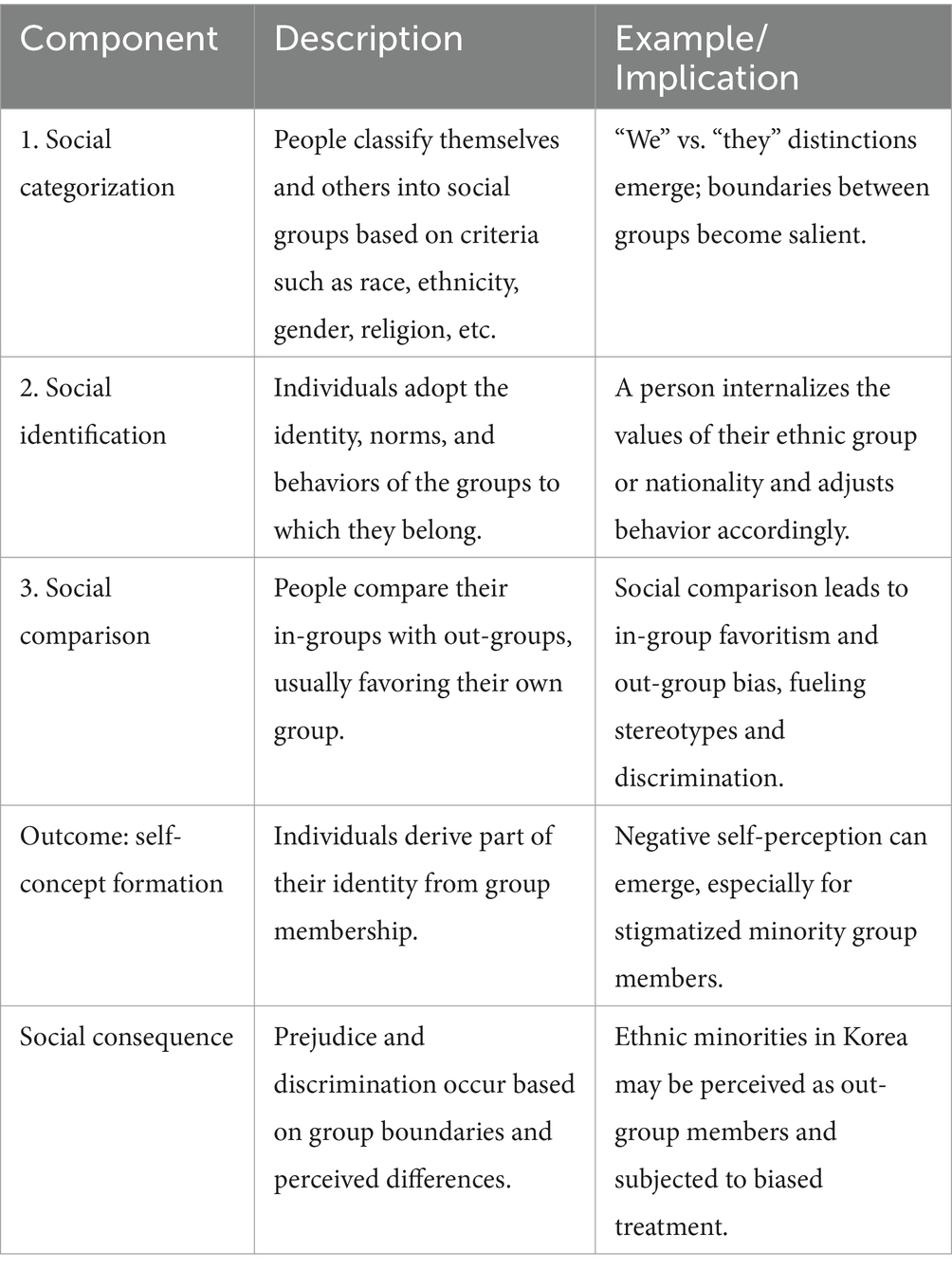

Social identity theory (SIT) focuses on intergroup relations within society and seeks to explore why discrimination occur among social groups. According to SIT, (a) social categorization: people establish boundaries between themselves and others on the basis of similarities and differences, classifying people according to certain criteria such as age, race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, religion, disability, socioeconomic status. (b) social identification: Once categorized, individuals tend to adapt their behaviors, attitudes and beliefs to conform with the norms of the groups to which they belong, forming their own sense of identity in the process (Tajfel and Turner, 2004). This social identification helps individuals who they are and where they belong. (c) Social comparison: In this process, people have in-group and out-group biases. People have a preference for people who belong to the same in-group as them. Individuals are evaluated by others according to the group to which they belong, with a tendency to view in-group members more favorably. In contrast, people tend to negatively evaluate people belonging to an out-group and these biased attitudes form the basis for discrimination and prejudice within society. The key concepts of Social Identity Theory are summarized in Table 1.

While realistic conflict theory (Sherif et al., 1961) emphasizes competition over scarce resources as a primary cause of intergroup conflict, SIT suggests that such intergroup conflict can arise without direct competition for resources. According to SIT, people derive self-concept from group membership, which often leads to the acquisition of a positive or negative identity for themselves (Brewer and Gaertner, 2002). To maintain positive social identities, people tend to favor members of their in-group and negatively evaluating out-group members. Indeed, ethnic minorities members are often stigmatized as out-group members who possess attitudes and behaviors perceived as different from those of the in-group (Abrams and Hogg, 2010). Such bias has also been directed towards ethnic minorities residing in Korea.

3.2 Social identities in a multicultural society

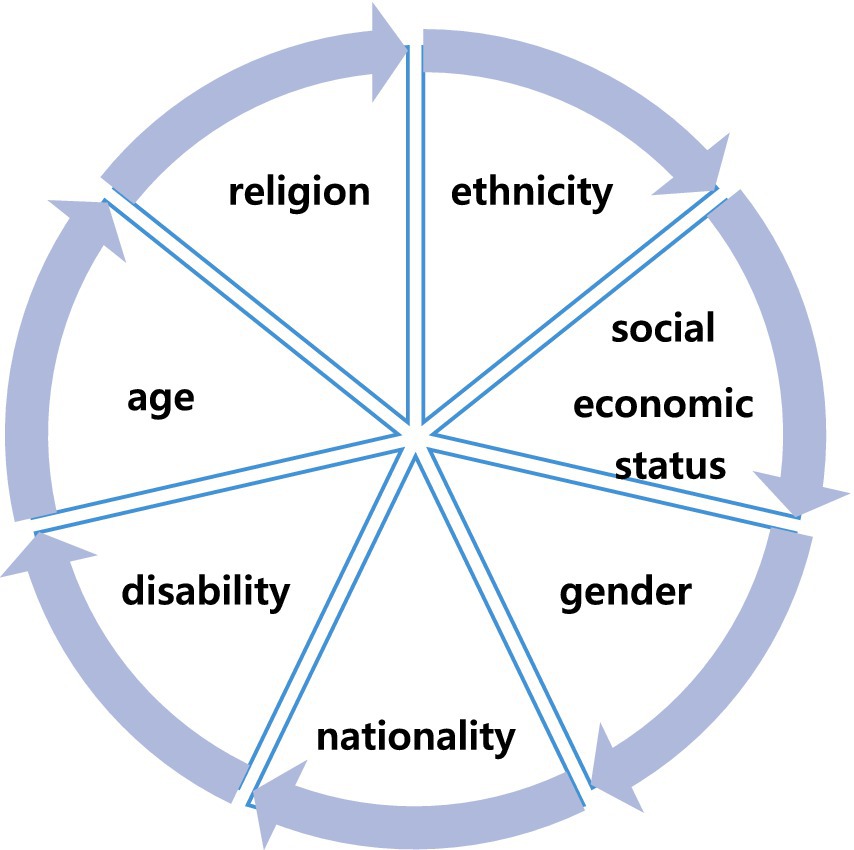

Social identities are neither singular nor fixed; rather, they are dynamic and multifaceted. Individuals are members of various social groups, and therefore, their social identities are shaped by a complex web of interconnections. In multicultural societies, three key characteristics of social identities-diversity, intersectionality, and fluidity-become particularly evident.

First, each person possesses diverse identity markers, such as gender, age, religion, occupation and nationality. People from these diverse backgrounds live together in multicultural society. Second, these social identities are intersecting and overlapping. For instance, an individual may simultaneously identify as a woman, Black, African-American, Christian, and a pilot. Third, these social identities are fluid and context dependent. A status of certain social identities can shift over time. For example, butchers, once a marginalized profession, no longer face the same level of discrimination. Additionally, an individual may be considered an out-group member in one aspect but an in-group member in another. For example, Korean and Japanese middle school students attending the same school would clearly consider each other to be members of an out-group based on nationality. However, they would see each other as in-group members due to their similarity in age and shared Asian ethnicity. In-group identity can be activated simultaneously across orthogonal criteria and individual social identity is shaped by diverse and intersecting factors.

This study proposes viewing individuals as beings who possess multiple social identities as a means of mitigating ethnic hatred stemming from social categorization. This approach advocates foregoing “us and them” distinctions based on ethnicity and instead looking at individuals as members of various categories. Diversifying categorization methods can be an effective way to reduce intergroup hatred (Crisp, 2010; Crisp and Hewstone, 2007). Conversely, transitioning to a more inclusive form of categorization can promote positive perceptions of others and reduce group bias.

In multicultural societies, individuals belong to multiple groups. One’s cultural, ethnic, and racial identities are all interconnected in a complex web of relationships. Consequently, a person’s social identities are diverse, multi-layered, and fluid –that is, they change over time and depends on context. And this approach can be applied to alleviate ethnic hatred on the internet, where hate rhetoric amplifies group-based discrimination.

3.3 Presenting a possible educational approach: recategorization and crossed categorization

Social identity theory assumes that individuals have multiple social identities and proposes recategorization and crossed categorization as methods for reducing prejudice and discrimination. While recategorization involves embracing individuals as part of more expansive categories, crossed categorization entails recognizing the diverse categories that individual members belong to.

First, during recategorization, it is crucial to decrease the salience of category distinctions between in-groups and out-groups to reduce intergroup bias. In this way, recategorization is intended to include a larger range of individuals under a common in-group identity, erasing previous “us and them” distinctions and establishing a more inclusive “we.” Consequently, individuals who were previously considered out-group members may experience a more favorable shift in the attitudes displayed towards them.

However, it is not possible to erase distinctions between individuals and even if it were possible, it would not be a socially desirable approach, as it could result in diversity being erased from society. It is also an unrealistic objective to make all prejudice disappear completely by covering top categories. Therefore, this study presents crossed categorization as a more favorable method.

Second, crossed categorization involves acknowledging both in-group and out-group distinctions, enabling individuals to recognize their diverse identities. Even while maintaining individual distinctiveness, crossed categorization can explore both shared in-group identities and non-shared identities. In essence, it involves both the convergence and divergence of identities, providing an opportunity to alleviate social division caused by specific categories.

According to the Social Identity Complexity Theory (Roccas and Brewer, 2002), individuals who perceive their multiple social identities are more likely to have acceptance of those who do not share in-group membership. In contrast, those with a more rigid, singular perception of identity are less likely to embrace diversity. Therefore, encouraging students to recognize their multiple social identities can help counteract the negative effects of social categorization and enhance understanding of their social identities as multifaceted and intersecting.

This study does not advocate for unconditional acceptance of all immigrants. Rather, it encourages individuals to recognize that individuals can simultaneously belong to both in-groups and out-groups depending on the social context. Bias and hostility towards specific groups will decrease when individuals acknowledge that they are unique and possess overlapping identity traits. When individuals assess each other in terms of their multiple social identities, it is possible to contribute to realizing a diverse yet inclusive society, which is a goal advocated by multicultural education (Banks, 2018).

4 Developing social studies instructions based on social identity theory to reduce ethnic hatred

This study developed a social studies instruction model that focuses on the issue of online ethnic hatred. This model, which is aligned with the Inquiry Design Model (IDM) of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), allows students to engage in a series of inquiry processes and explore the cases of ethnic hatred, as well as their causes and solutions.

To reduce intergroup bias and conflict, many pedagogical strategies have been developed based on contact hypothesis. According to contact hypothesis, individuals who are exposed to members of other groups in diverse contexts are more likely to develop more positive toward out-group members and less likely to exhibit prejudicial behavior (Dovidio et al., 2011). Educational activities involving both direct and indirect contact—such as cooperative learning, media-based approaches, and role-playing—have been implemented to improve intergroup relations. However, these approaches often fall short in providing students with opportunities to critically examine the root causes of ethnic hatred from a cognitive perspective. As the proposed model progresses sequentially through the inquiry process, students enable to recognize prejudice and deepen their awareness.

4.1 Dimensions of the inquiry design model (IDM)

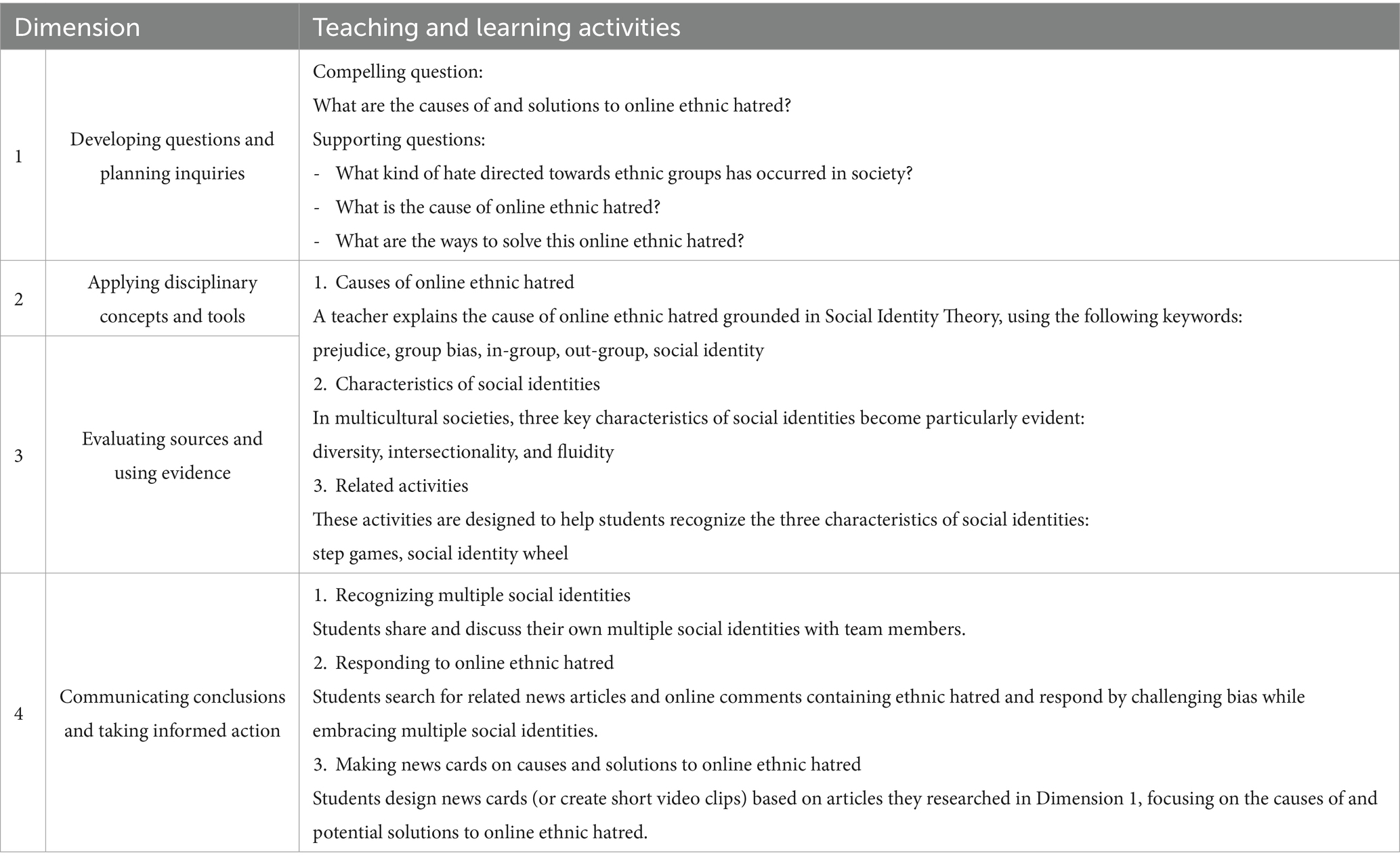

The IDM is a framework for creating teaching materials that was developed by the NCSS to facilitate inquiry-based learning in alignment with the C3 Framework for social studies state standards. The following inquiry arc is a framework that structures the investigation of a social issue in the specific context of a classroom lesson. This framework consists of four dimensions: (1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) evaluating sources and using evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action (Herzog, 2013).

For the first dimension, students are presented with two types of questions—compelling questions and supporting questions. Compelling questions are broad questions that ask about a particular social issue; supporting questions are intended to examine the issue in more detail. By presenting questions, students are prompted to develop an interest in the social issue at hand.

For the second dimension, which is the foundational step of the inquiry, students obtain the major disciplinary content they need to learn using this instruction model. Teachers select three to four key concepts from the disciplinary (civic, economic, geographical or historical) or multidisciplinary areas that are intimately related to the topic under inquiry.

For the third dimension, students participate in collecting and analyzing the information necessary to solve the inquiry problem. There are various types of data, such as direct observations, visual data, statistical figures, maps and legislation.

For the fourth dimension, the objective is to answer the questions presented in the first dimension and to practice actively engaging in problem-solving (Grant et al., 2017). Students can engage in group discussion, create visual materials or take various other forms of action based on the results of the inquiry.

The details of the instructional model developed according to the inquiry arc are shown in Table 2.

4.2 Sample inquiry design model for ethnic hatred

4.2.1 Learning objectives and social studies standards

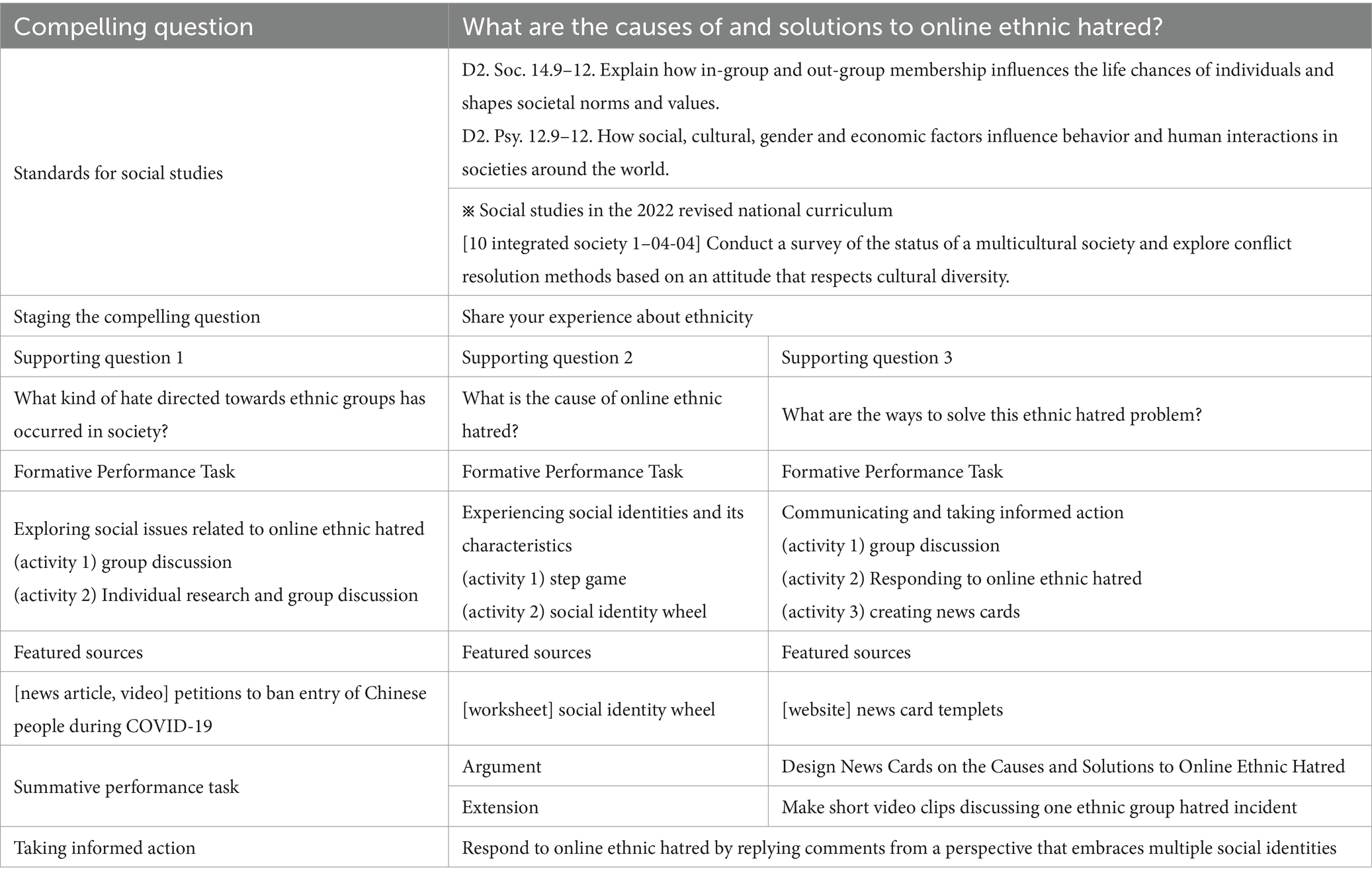

The instructional model developed for this study sets three educational objectives to help students recognize ethnic hatred based on the social identity theory. This study primarily aims to help students recognize the underlying causes of ethnic hatred and explore potential solutions followed by the inquiry process of IDM. Accordingly, the learning objectives are presented as follows.

1. Knowledge: students will explain the cause of the problem of online ethnic hatred focusing on the social identities.

2. Skills: students will explore their own and others’ multiple social identities across various criteria.

3. Value: students will reflect on online ethnic hatred and assess how their understanding of social identity has changed.

To ensure its applicability in classroom settings, this instructional model aligns with the national standards of social studies for high school students. Specifically, these are the sociology and psychology standards presented in the C3 Framework of NCSS in the United States and the 2022 revised national social studies curriculum in Korea.

D2. Soc. 14.9–12. Explain how in-group and out-group membership influences the life chances of individuals and shapes societal norms and values.

D2. Psy. 12.9–12. How social, cultural, gender and economic factors influence behavior and human interactions in societies around the world.

[10 integrated society 1-04-04] Conduct a survey of the status of a multicultural society and explore conflict resolution methods based on an attitude that respects cultural diversity.

4.2.2 Pedagogical format

The instructional model begins with the following general question: “What are the causes of and solutions to online ethnic hatred?” Following the IDM, the model presents students with a series of three follow-up supporting questions that examine online ethnic hatred. And these questions guide the inquiry processes through the four dimensions of the IDM.

[Dimension 1] Developing questions and planning inquiries.

The first supporting question asks: “What kind of hate directed towards ethnic groups has occurred in society?”

To explore discrimination towards ethnic groups in Korea, a teacher introduces relevant news articles or videos. For example, this model examines the anti-Chinese entry petitions during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using those featured sources, students analyze the situation in which Chinese were discriminated against due to their ethnic social identities during the pandemic. The teacher then facilitates group discussions (4–6 students per group) using the following guiding questions:

- What is the situation? (5W1H: Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How).

- What are the characteristics of the people experiencing discrimination in this case?

- How might they feel facing the discrimination?

Following the group discussion, students conduct individual research by searching for related news articles online. While reading articles and their comment sections, students critically assess the severity of the issue. The teacher further reinforces the importance of addressing online ethnic hatred by posing additional reflective questions:

- What is the situation? (5W1H: Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How).

- What are the potential consequences of this issue?

- If this problem remains unresolved, what could happen in the future?

Students share their insights with their group members, fostering collaborative discussions. To conclude the session, the teacher informs students that the next lesson will focus on analyzing the root causes of the problem in greater depth.

[Dimension 2–3] Applying disciplinary concepts and tools and Evaluating sources and using evidence.

The second supporting question asks: “What is the cause of online ethnic hatred?”

To help students understand the causes of online ethnic hatred based on the social identity theory, key concepts such as prejudice, group bias, in-group, out-group, and social identity are introduced. The teacher explains social identities by emphasizing three key points: (1) Social identity is classified based on various criteria, such as age, gender, ethnicity, nationality, religion, social economic status, and occupation. (2) Social identities are overlapping (e.g., an individual simultaneously be a woman, Black, African American, Christian, and a pilot). (3) Social identities are fluid and can change depending on the social context (e.g., women were denied the right to vote due to their social identity, but this is no longer the case).

To reinforce these points, the teacher facilitates the following activities:

(Activity 1) step game.

This activity is designed to help students recognize the diversity of their own social identities. The teacher asks students to stand in a line and step forward based on their responses to a series of statements. The teacher may guide the activity with prompts such as:

- If you are an only child, take a step forward.

- If you are a left-handed person, take two steps forward.

- If your first language is English, take a step forward.

By observing how their positions shift, students will see that even within the same environment, individuals have distinct experiences and identities.

(Activity 2) social identity wheel.

This activity encourages students to identify their various social identities and reflect on how these identities influence their self-perception and interactions with others. This activity is adapted from the Equitable Teaching Initiative at the University of Michigan4. Figure 1 provides an example of the social identity wheel worksheet. The teacher facilitates a discussion using the following reflective questions:

- Which identities do you think about most (or least) often? How has this changed over time? (compare now and future).

- Which identities do you think about most (least) important? How has this changed over time? (compare now and future).

- Which identities have the strongest effect on how you perceive yourself?

- Which identities have the greatest effect on how others perceive you?

[Dimension 4] Communicating conclusions and taking informed action.

The third supporting question asks: “What are the ways to solve this online ethnic hatred problem?”

In the final dimension 4, students are encouraged to consider how they can actively contribute to mitigating online ethnic hatred from the perspective of SIT. This stage emphasizes critical reflection, discourse, and practical engagement.

First, students share their multiple social identities and find out their common social identities with group members. Through discussion, students can explore how they may share identities with individuals who are often targets of ethnic hatred. This activity helps students move beyond rigid “us vs. them” categorizations and recognize the fluid and intersecting nature of social identities.

Second, students search the comments or posts containing ethnic hatred and write reply that challenge bias from a perspective that embraces multiple social identities (e. g. Go back to your country? This is their home too. Do not judge people by skin color—everyone’s different, and that is cool). This practice helps students take informed action to discriminatory rhetoric.

Third, students design news cards summarizing the article that they searched in dimension 1. If resources allow, making short video clips is also effective way to raise awareness and share with other students about online ethnic hatred. The pedagogical format was designed according to the IDM format and is shown in Table 3.

4.2.3 Evaluation

Assessment of student learning is conducted through a combination of peer, self, and teacher evaluations: peer and self-evaluation (dimension 1–3), peer and teacher evaluation (dimension 4). In the process of carrying out the formative performance tasks and summative performance tasks, students reflect on their performance based on the criteria which are critical thinking, creative thinking, data collection and utilization, and communication skills. Teachers can evaluate whether students present arguments and grounds appropriately (critical thinking), offer novel alternatives (creative thinking), search for appropriate information using the internet (data collection and utilization), and actively participate in the process of exchanging opinions with group members (communication skills). Since these criteria serve as a flexible framework, the teacher may modify the criteria according to the class situation, student levels, and learning objectives.

4.2.4 Learning environment

This teaching model is designed for 15–20 high school students and is expected to take approximately three to four class sessions, depending on instructional time and student engagement. Based on this sample, more detailed pedagogical formats and featured sources can be adapted to suit the classroom setting, student level, and individual characteristics.

Above all, before implementing the lesson, teachers should be mindful of the students’ ethnic backgrounds. If instructional materials (e.g., readings, videos) depict a particular ethnic group as the target of the hate and the students from that group are present in the classroom, the use of such materials may be inappropriate or emotionally challenging. In such cases, it is important to prepare alternative materials that address discrimination against other ethnic groups.

5 Conclusion

Individuals consistently evaluate their own group and its position and status within society. Members of marginalized ethnic groups may conceal or downplay their ethnic background to appear as members of mainstream society. Banks (2018) criticizes the preference for acculturation among immigrants because it results in a form of self-alienation whereby the individual rejects their ethnic and racial identity.

Given the increasing severity of ethnic hatred, it is crucial to provide students with educational experiences addressing this issue. This study develops a social studies teaching model grounded in social identity theory, aimed at reshaping students’ perceptions of the group that is target of such hate and reducing discrimination in multicultural societies. Using the framework of the Inquiry Design Model (IDM), developed by the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), this model guides students to explore causes and solutions to ethnic hatred, with a focus on multiple social identities. Additionally, this study presents a sample teaching model applicable to both Korean and U. S. social studies curricula, enhancing its adaptability across different educational contexts.

Through the instructional contents and activities proposed in this study, students can recognize that they are interconnected. Also, students can confront their own ignorance and biases and develop a broader understanding of diversity within the concept of “us.” While social identity theory primarily addresses the cognitive and social-psychological roots of prejudice at the individual level, it does not fully explain the ethnic hatred from an expanded socio-political perspective. In contrast, critical race theory argues that ethnic hatred is embedded in societal structures. Majority groups construct imbalanced social systems and enforce structural oppression against marginalized groups. This systematic form of discrimination ultimately persists at both the societal and interpersonal level. Future research could further explore issue of power imbalance and institutionalized injustice within society.

Above all, this study encourages students to work toward the ultimate goal of fostering a society where the diverse backgrounds of all individuals are acknowledged and respected. It also supports student in critically examining any unacknowledged privileges they may hold as members of a majority group, while fostering empathy toward marginalized group members. To further validate the effectiveness of the instructional model, follow-up studies should be conducted in real classroom settings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The “Dancing Pallbearers,” also known as the coffin dancers, are part of a Ghanaian funeral tradition where pallbearers dance to joyfully celebrate the life of the deceased. Some Korean high school students parodied this performance while wearing blackface, and photos of the events spread widely on social media. This led to mixed reactions online, with some people debating whether the performance was culturally acceptable or offensive (The Korea Times, 2020).

3. ^Featured Sources1. News article: As Coronavirus Spreads, So Does Anti-Chinese Sentiment (New York Times, 2020.1.30) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/30/world/asia/coronavirus-chinese-racism.html.2. Video: Chinese national complains about South Korea’s targeted Covid-19 curbs for arrivals from China (South China Morning Post Eun, 2023.1.12) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgOcqE3NtGE.

4. ^https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/equitable-teaching/social-identity-wheel/

References

Abrams, D., and Hogg, M. A. (2010). “Social identity and self-categorization” in The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. eds. J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, and V. M. Esses (London: SAGE Publications Ltd).

Brewer, M. B., and Gaertner, S. L. (2002). “Toward reduction of prejudice: intergroup contact and social categorization” in Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intergroup processes. eds. R. Brown and S. L. Gaertner (New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell), 451–472.

Castaño-Pulgarín, S. A., Suárez-Betancur, N., Vega, L. M. T., and López, H. M. H. (2021). Internet, social media and online hate speech. Systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 58:101608. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2021.101608

Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., and Valentine, J. C. (2019). “Research synthesis as a scientific process” in The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. eds. H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, and J. C. Valentine (London: Russell Sage Foundation), 3–16.

Crisp, R. J. (2010). “Prejudice and perceiving multiple identities” in The sage handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. eds. J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, and V. M. Esses (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 508–526.

Crisp, R. J., and Hewstone, M. (2007). Multiple social categorization. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 39, 163–254. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39004-1

Dovidio, J. F., Eller, A., and Hewstone, M. (2011). Improving intergroup relations through direct, extended and other forms of indirect contact. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 14, 147–160. doi: 10.1177/1368430210390555

Eun, J. (2023). A media criticism-based approach for designing critical multicultural instruction in social studies curricula. Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 31, 129–146. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2021.1891450

Evolvi, G. (2019). #Islamexit: inter-group antagonism on twitter. Inf. Commun. Soc. 22, 386–401. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1388427

Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T., and Martinez, G. (2015). Countering online hate speech. Paris: Unesco Publishing.

Grant, S. G., Swan, K., and Lee, J. (2017). Inquiry based practice in social studies education: Understanding the inquiry design model. London: Routledge.

Herzog, M. (2013). “The college, career and civic life (C3) framework for social studies state standards: a watershed moment for social studies” in Social studies for the next generation: Purpose, practices and implications of the college, career and civic life (C3) framework for the social studies state standards. ed. National Council for the Social Studies (Kaysville, UT: NCSS), 7–10.

Keen, E., Georgescu, M., and Gomes, R. (2020). Bookmarks-a manual for combating hate speech online through human rights education (2020 revised edition). Budapest: Council of Europe.

Kim, J. H., Kim, J. R., Kim, C. H., Kim, H. M., Park, Y. A., Lee, W., et al. (2019). A study on the status of racism in Korean society and the legislation for elimination of racism. Seoul: National Human Rights Commission of Korea.

Kysia, A. (2024). What is islamophobia? Teaching strategies for critical literacy. J. Liter. Res. 56, 379–399. doi: 10.1177/1086296X241300116

Nguyen, T., Huang, D., Michaels, E., Glymour, G., Allen, A., and Nguyen, Q. (2021). Evaluating associations between area-level twitter-expressed negative racial sentiment, hate crimes, and residents’ racial prejudice in the United States. SSM - Population Health 13:100750. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100750

Roccas, S., and Brewer, M. B. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 6, 88–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W., and Sherif, C. W. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The robbers cave experiment. Norman, OK: The University Book Exchange, 155–184.

Statistics Korea. (2023). “Domestic and foreign population projection reflecting future population projection in 2021: 2020-2040” Korean statistical information service, Statistics Korea. Available online at: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&&bid=207&act=view&list_no=417775 (accessed May 5, 2025).

Tajfel, H. (1972). “Social Categorization” in Introduction à la Psychologie Sociale. ed. S. Moscovici, vol. 1 (Paris: Larousse), 272–302.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (2004). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict” in Organizational identity: A reader. eds. M. J. Hatch and M. Schultz (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 56–65.

The Korea Times. (2020). Blackface’ high school yearbook photo sparks controversy. Available online at: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/society/20200805/blackface-high-school-yearbook-photo-sparks-controversy (Accessed May 5, 2024).

Turner, J. C., and Reynolds, K. J. (2012). “Self-categorization theory” in Handbook of theories of social psychology. eds. P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 399–417.

United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (2019). Concluding observations on the combined seventeenth to nineteenth periodic reports of the Republic of Korea. Geneva: United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect (2023). Addressing hate speech through education: a guide for policy-makers. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Watanabe, H., Bouazizi, M., and Ohtsuki, T. (2018). Hate speech on twitter: a pragmatic approach to collect hateful and offensive expressions and perform hate speech detection. IEEE Access 6, 13825–13835. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2806394

World Value Survey Wave 7 (2017–2022). World Values Survey Association. Available online at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp (Accessed May 5, 2024).

Keywords: ethnic hatred, social identity, multiple social identities, social studies education, multicultural education

Citation: Chun J and Eun J (2025) Countering ethnic hatred and its pedagogical approach in social studies: focusing on multiple social identities. Front. Educ. 10:1575926. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1575926

Edited by:

Woonsun Kang, Daegu University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Daehoon Jho, Sungshin Women’s University, Republic of KoreaJinhwan Ong, Sunchon National University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Chun and Eun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ji-Yong Eun, ZXVuank2OUBzbnUuYWMua3I=

Jabae Chun

Jabae Chun Ji-Yong Eun

Ji-Yong Eun