- Talpiot College of Education, Holon, Israel

This policy brief explores how a shift in perspective changed the educational environment for EFL educators to improve student teachers’ oral performance. Grounded in action research, we present reflective, practice-based policies. A key finding of action research was the central role of social–emotional factors, specifically foreign language anxiety. The department began a process of expansive learning to integrate the ACCESSES framework (Autonomy, Collaboration, Communication, Empowerment, Scaffolding and Emotional Safety). This shift fostered a collaborative culture, addressed emotional needs in language learning, and led to instructional redesign. Core practices refined through ongoing professional development, transformed the departmental culture into a space of experimentation and applied theory. We redefined our teaching and learning, which became a model for broader institutional change.

1 Introduction

This brief1 shows how EFL teacher educators reformed their pedagogy by studying their own practice and adapting to their students’ needs. This reform stemmed from the findings of three cycles of action research,2 which revealed which factors promoted the oral performance3 of EFL student teachers following an intervention (Speak Up, Appendix 1). Findings from interviews post-intervention revealed that oral performance was more impacted by social–emotional elements such as foreign language anxiety (FLA) than by knowledge of grammar and vocabulary (Telor-Reize et al., 2023). Another finding was the trade-off of accuracy and fluency; an incline in one boosts a decline in the other. As a result, we created a framework that addresses social–emotional needs to alleviate FLA and improve spoken English.

2 The theoretical framework

In the fourth cycle, the department underwent a process of expansive learning. The theory of expansive learning is the construction and implementation of new professional knowledge (Engeström, 1987; Engeström and Sannino, 2010). This theory of expansive learning has been applied in different educational and professional contexts to support systemic transformation. Engeström et al. (2022) describe formative interventions that promote facilitative learning and institutional change across six continents. In Norway, Smith (2020) documents the use of expansive learning to develop research skills in teacher educators. Similarly, Engeström and Pyörälä (2020) used this approach to transform medical education with healthcare experts.

Expansive learning theory is a framework to effect change. The department expanded by using ACCESSES, which consisted of Autonomy, Collaboration, Communication, Empowerment, Scaffolding and Emotional Safety. Expansive learning involves learners “constructing and implementing a radically new, wider and more complex object and concept for their activity” (Engeström and Sannino, 2010) p. 2. In this regard, the “learners” were the department members.

This type of transformation aligns with the broader shift in teacher education toward expansive learning models that generate both innovation and pedagogical renewal (Guberman et al., 2021).

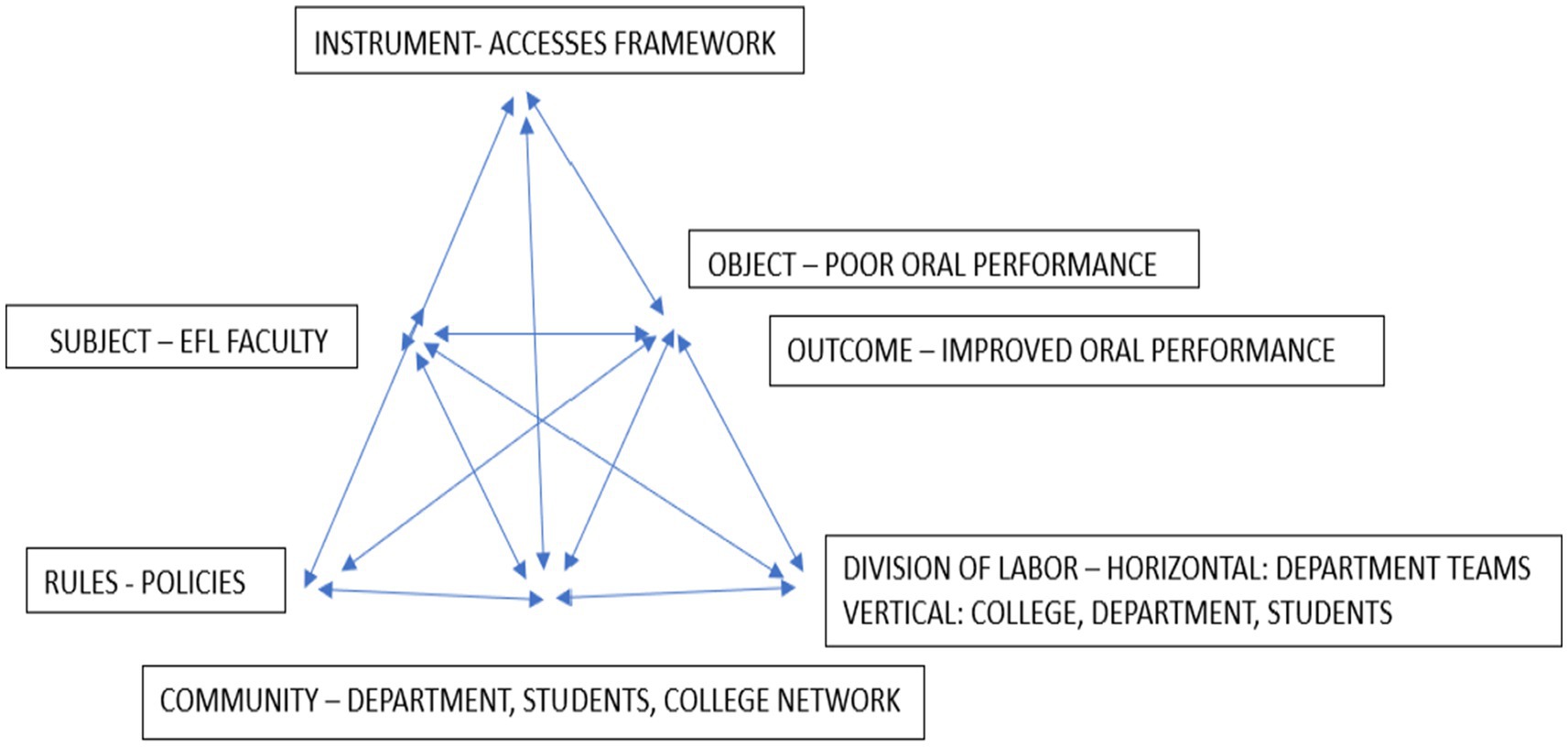

The following illustration depicts the reform process the department underwent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Departmental reform process (based on Engeström, 1987, p. 78).

In Figure 1, subject refers to the EFL faculty who comprise the subgroup being analysed. The object refers to the poor oral performance of student teachers which is the problem being addressed. This object will turn into the outcome of the improved oral performance of the student teachers with the help of the instrument which is the ACCESSES framework. Community refers to the department, students and college network who all share the same object. Division of labor refers to the expert teams (horizontal level) within the department and to the hierarchy of the college, department, and students (vertical level). Finally, rules refer to policies that are now standard practice within the department.

The department underwent a significant transition in its mindset and practices which we will refer to as “culture.” Previously, lecturers had been creating syllabi and teaching individually according to college and departmental general mandates. The prevailing belief was that each lecturer decided independently how to plan and convey his/her content. A need for change arose when we were required to adopt the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) in (2018) as our standard of assessment for English proficiency. Consequently, we began administering entrance and exit oral proficiency exams using the CEFR. The results of these exams provided a clearer and more standardized picture of most of our student teachers’ poor oral performance in English (Appendix 3).

The English department staff realized that in order to improve student teachers’ oral performance there was a need for change. Using expansive learning theory led to the formulation of three governing policies:

1. Fostering a new departmental culture of collaboration.

2. Recognizing the importance of emotional needs.

3. Designing new instructional tenets.

3 Policies and practices

3.1 Fostering a new departmental culture of collaboration

The first change the staff made was recognizing the need to collaborate and acknowledge a shared responsibility for our students’ success. The next change was the development of teams. Each team assumed a collective responsibility for the various proficiencies taught in English such as oral, written and academic. The heretofore individual agency of each lecturer became the collective agency of each team. This new teamwork rendered the English program cohesive and as a result more effective. A crucial change was that the staff embraced the idea that significant progress requires substantial effort. Lecturers (and eventually students), acknowledged that improving oral English proficiency would demand a lot of work and dedicated practice. In other words, the lecturer’s role required a redefinition which involved perceiving students differently; not as students striving for a grade, but as learners engaged in a process of growth and development. This perception included the idea that students must be viewed individually and catered to by adopting personalized learning. As Rust (2020) noted, teacher education must enable prospective teachers to grapple with their own experiences as learners. Consequently, it was important to foster an empathic attitude and belief in our student teachers.

In order to implement the collaborative departmental culture, the staff underwent a process of expansive learning. The expansive learning theory emphasizes a transformation from individual to collective, network-based learning, where members collaboratively redefine and model new practices (Engeström and Sannino, 2010). In the department’s case, expansive learning took place when the staff adopted the ACCESSES framework (Autonomy, Collaboration, Communication, Empowerment, Scaffolding and Safety zones)4 which had been previously used for an oral proficiency intervention (Appendix 1). The use of this methodology enabled each team to exercise autonomy, create peer collaboration, and employ scaffolding for empowerment in activities such as syllabus planning and alignment with other syllabi used for courses that teach the same proficiency.

Core values such as shared ideas, collective responsibility, and staff agency became integral, fostering a sense of partnership and shared responsibility for teacher training. However, transitioning from staff to a cohesive team required time, a common goal, and collective effort.

Teamwork and collaboration are now guiding tenets (Tessier, 2022). The department holds regular team meetings and collaborative planning sessions, ensuring all members are well-informed and engaged in decision-making processes and idea pioneering. This collaborative atmosphere has transformed our lecturers into instructional “design makers and negotiators,” with teams working together to ensure accuracy, effective language/linguistics instruction, and appropriate AI integration.

Over the past 5 years, we have focused on aligning teaching methods and course content, revising oral proficiency assessment rubrics, and developing accuracy core programs leading to C1 proficiency (CEFR). Adopting Vygotsky (1978) zone of proximal development has guided our efforts, creating modular, tailored programs and flexible syllabi. This approach has not only facilitated a more personalized learning experience but has also encouraged a department-wide commitment to continual improvement and collective success. Our teacher educators, as the physicians in the intervention led by Engeström and Pyörälä (2020), “…were challenged to develop collaborative and transformative expertise”.

3.2 Recognizing the importance of emotional needs

3.2.1 Understanding foreign language anxiety (FLA)

Among the emotions associated with second language acquisition (SLA), language anxiety has received the most attention—possibly because it is both intense and frequent (MacIntyre, 2017). MacIntyre and Gardner (1994) define language anxiety as “the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second language contexts, including speaking, listening, and learning” (p. 284). Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), in a large-scale study (n = 1764), emphasized the central role that oral proficiency plays in generating foreign language classroom anxiety. FLA often manifests in hesitations, fragmented speech, and visible discomfort. It is intensified by fear of judgment, especially in performance-based activities like speaking (Sımsek and Capar, 2024). Interestingly, research links high anxiety to lower oral proficiency, regardless of underlying knowledge (Jin and Dewaele, 2018).

3.2.2 Confidence, self-esteem, and performance

Oral proficiency is closely tied to learners’ confidence when speaking. That confidence is influenced by vocabulary knowledge, grammar control, and perceived proximity to native-like standards. Dewi et al. (2022) found that Indonesian EFL learners with high self-esteem performed better than peers with lower self-esteem. Pizarro (2019) also found that lower levels of FLA were strongly associated with higher self-confidence among Spanish prospective EFL teachers. He identified fear of speaking as the main source of anxiety. Findings from interviews (see Appendix A) held with third year students in our department post intervention (Speak Up) corroborate the above findings (Pizarro, 2019; Dewi et al., 2022).

3.2.3 Challenging the “native speaker” ideal

The pursuit of native-like fluency in English has long been considered the ultimate goal for L2 language learners and teachers. However, this “nativeness” standard is a fallacy (Phillipson, 1992); a non-native speaker cannot truly speak and sound like a native. Nevertheless, nativeness continues to influence how EFL teachers perceive their professional identity (Gonzalez, 2016; Mannes and Katz, 2020) and how learners evaluate their own abilities. This very pursuit of nativeness often increases FLA and impedes participation (Telor-Reize et al., 2025). In today’s globalized world, where multiple “Englishes” coexist (Kachru and Smith, 2008), the majority of English speakers are non-native (Davies, 2013). The CEFR Companion Volume (Council of Europe, 2020) in fact explicitly said that “Level C2 [highest level] while it has been termed “Mastery,” is not intended to imply native-speaker or near native-speaker competence” (p. 37). Thus, the department is aligned with the CEFR which does not set nativeness as its highest standard. The department adopted a more inclusive view of linguistic identity, valuing fluency and self-expression.

3.2.4 Creating an emotionally supportive environment

“When I saw that even if I made a mistake, no one raised an eyebrow or reacted negatively. So, I wasn’t afraid to speak. So, I felt more comfortable speaking and tried again, and that’s how my English improved.” (see text footnote 2)

In response to the emotional barriers discussed, the department embedded emotional safety into course, syllabi and assessment design. The ACCESSES framework enabled this emotional support because it centered on emotional safety, autonomy, and scaffolding. A key aspect of this approach involved forfeiting the standard of native-like ability and perceiving errors more positively. By understanding that grammatical mistakes are an integral part of the learning process, students could speak more fluently without pressure to achieve native-like perfection. While this new approach was initially challenging for lecturers, they eventually acknowledged the trade-off; abandoning the nativeness myth created an environment where students felt more comfortable expressing themselves fluently.

Pedagogical practices included:

• Successive speaking tasks (based on TBL approach, see 3.3)

• Flexible feedback and correction opportunities.

• De-emphasizing accuracy during fluency tasks.

These practices are not limited to language learning. Students in other subjects such as math, art, science (STEM) also benefit from environments that tolerate error, support self-expression, and lower performance pressure.

3.3 Designing new instructional approaches

“After the SC [Speak Up Cycles intervention], I really had more confidence. Even if you make mistakes here [in the intervention], no one will eat you alive. It’s not a firing squad here, it’s all good.” (see text footnote 2)

Fluency relies on increased automaticity in speaking (Tavakoli and Wright, 2020). Saville-Troike and Barto (2022) state that “frequency and practice lead to automaticity in processing, freeing up learners’ cognitive capacity” (p. 186). Therefore, an L2 methodology utilizing frequent communicative activities can promote fluency development. Therefore, we decided to adopt a task-based language (TBL) approach (Skehan, 2009; Ellis, 2003) which uses repetition due to its beneficial impact on performance (Bui and Skehan, 2018).

Maximizing our efforts to have the students practice their oral proficiency meant providing them with ample opportunities to automize English using classroom interaction (Dubiner, 2019). This shift translated into a rigorous reconstruction of the program, including all syllabi and curricula. The following components were included:

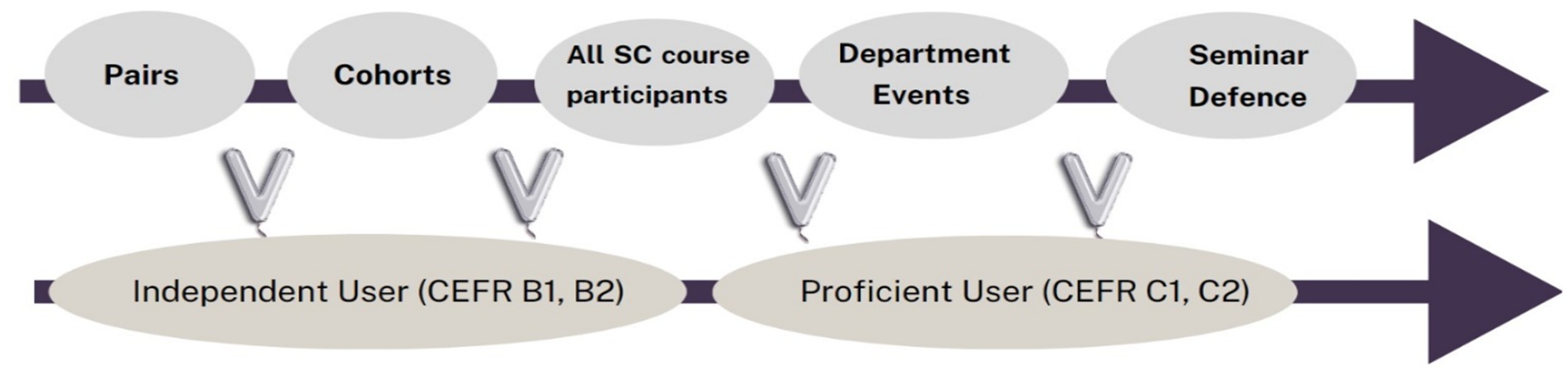

• The “Speak Up” programme featured a new conceptual construct, the Pedagogical Oral Proficiency Training Process, which was designed to provide scaffolding. Using five steps, learners can make gradual and effective progress in their language skills (see Figure 2).

• An accessible approach to grammar, the Renaming Grammar Methodology (RGM) (Gluck, 2024), which focused on renaming grammatical structures making them easier to understand and use.

• Individually designed speaking chatbots to cater to individual needs using AI.

• Departmental collaborative learning events providing opportunities to speak in English and connect.

• The addition of four new proficiency courses to the existing six courses, based on the ACCESSES framework.

4 Actionable recommendations

Based on the three governing policies mentioned above, the following are potential adaptations for different contexts:

Teacher-education departments

• Ensure the individual agency of each lecturer infuses the collective agency of the entire department.

• Schedule regular meetings for shared planning and peer feedback.

• Integrate affective and collaborative strategies into syllabus design taking both students and lecturers into account.

• Foster learner-centered methodologies by implementing personalized learning

• Implement task-based methodologies

Institutional leaders

• Allocate time for whole faculty collaboration and reflective practices.

• Embrace a culture supporting emotional well-being as a priming component of student and faculty success.

• Experiment with and implement instructional programs based on collaboration and learner autonomy.

Policymakers

• Develop policy guidelines that support emotional safety, collaborative design, empowerment and professional reflection in teacher education.

• Opt for flexible theoretical and pedagogical constructs (such as expansive learning), as alternatives to traditional frameworks.

• Embrace the critical and useful implementation of AI.

4.1 Limitations

This policy brief examines a department-led initiative to reform instructional practices within a higher education context. However, this model was developed and conducted within one institutional setting, which may affect the generalizability of the outcomes. A different contextual adaptation elsewhere would require the following underpinning conditions: time for team planning and institutional support for reflection practices including a shared willingness to grow and experiment with the new methods as well as grapple with the leading principle of emotional safety.

5 Conclusion

The departmental transformation has been far-reaching. It has reshaped the approach to education by embracing expansive learning theory, collaborative core values, and a teamwork-driven environment. The department evolved into an experimental space for collective growth, knowledge accumulation, and translating theory into actionable tools.

As Guberman et al. (2021) emphasize, expansive learning is not merely a process of change but a catalyst for systemic transformation. They argue that it fosters “transformed practices, novel theoretical conceptualizations, and an empowered sense of agency” (p.1). This perspective strongly resonates with the ongoing process of expansive learning in our department, where implementing the ACCESSES framework enabled faculty to shift from individual efforts to collaborative innovation, turning theory into shared, sustainable practice.

The English department defined core instructional practices fundamental for student teacher success. The college has begun extending those practices to other teacher training departments by using the ACCESSES framework in professional development. We also expanded the core instructional practices to the neighboring schools where our teachers train (pedagogical clinics). Similar to the TCOOL (Teachers Community of Ongoing Learners) project led by Rust (2020), we are disseminating our practices beyond our department.

We claim that educators must be positioned as agents of change, redefining their roles to become mediators for students. Reframing professional identity means seeing oneself as a collaborative educator, engaging in dialogue with colleagues and students rather than delivering content unilaterally.

Future policy makers and institutional leaders who strive for sustainable change, long-term commitment, and success might benefit from the expansive learning framework and the three governing policies we formulated: (1) fostering a new departmental culture of collaboration (2) recognizing the importance of emotional needs and (3) designing new instructional tenets.

Author contributions

DTR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1588265/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^While grounded in action research, this brief is a reflective policy document, focused on practice-based insights aiming to inform institutional learning and policy rather than serve as formal empirical research.

2. ^See link to ISAAT conference presentation July 2023 (Telor-Reize et al., 2023).

3. ^Oral performance refers to oral proficiency (speaking) in layman’s terms. In addition, educators, lecturers, staff and faculty all refer to groups of people in the college

4. ^The ACCESSES framework was initially termed ACCESS in the oral proficiency intervention. The addition of ES (emotional safety) became a necessary expansion based on the 3rd cycle findings (Appendix 1).

References

Bogdan, R., and Biklen, S. K. (1997). Qualitative research for education. 3rd Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bui, G., and Skehan, P. (2018). Complexity, accuracy, and fluency. The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 1–7.

Council of Europe (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment—Companion volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Davies, A. (2013). Is the native speaker dead? Hist. Epistemol. Lang. 35, 17–28. doi: 10.3406/hel.2013.3455

Dewaele, J.-M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 237–274. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewi, I. A., Widiyani, E., and Kurniawan, A. (2022). The relationship between students’ speaking skill and students’ self-esteem of mover F class of NCL Madiun. J. Eng. Teaching 8, 267–281. doi: 10.33541/jet.v8i2.3743

Dubiner, D. (2019). Second language learning and teaching: from theory to a practical checklist. TESOL J. 10:e00398. doi: 10.1002/tesj.398

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y., Bal, A., Sannino, A., Morgado, L. P., de Gouveia Vilela, R. A., and Querol, M. A. P. (2022). “Expansive learning and transformative agency for equity and sustainability: formative interventions in six continents,” in Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the Learning Sciences-ICLS 2022, pp. 1731–1738. International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Engeström, Y., and Pyörälä, E. (2020). Using activity theory to transform medical work and learning. Med. Teach. 43, 7–13. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1795105

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 1, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Gluck, S. (2024). Delta 2024. The Science of Classroom Learning [Conference presentation] Delta Convention. Available online at: https://drsandygluck.substack.com/p/dont-be-tense-about-the-tenses-the?r=5rsdzs (accessed December 30, 2024).

Gonzalez, J. J. V. (2016). Self-perceived non-nativeness in prospective English teachers' self-images. Rev. Bras. Linguist. Apl. 16, 461–491. doi: 10.1590/1984-639820169760

Guberman, A., Avidov-Ungar, O., Dahan, O., and Serlin, R. (2021). Expansive learning in inter-institutional communities of practice for teacher educators and policymakers. Front. Educ. 6:533941. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.533941

Jin, Y. X., and Dewaele, J.-M. (2018). The effect of positive orientation and perceived social support on foreign language classroom anxiety. System 74, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.002

Kachru, Y., and Smith, L. E. (2008). Cultures, contexts, and world Englishes. New York, NY: Routledge.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2017). “An overview of language anxiety research and trends in its development” in New insights into language anxiety: Theory, research and educational implications. eds. C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, and J.-M. Dewaele (Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 11–30.

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang. Learn. 44, 283–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

Mannes, A., and Katz, Y. J. (2020). The professional identity of EFL teachers: the complexity of nativeness. Curr. Teaching 35, 5–24. doi: 10.7459/ct/35.2.02

McDonough, J., and McDonough, S. (1997). Research methods for English language teachers. London: Routledge.

Pizarro, M. A. (2019). Do prospective primary school teachers suffer from foreign language anxiety (FLA) in Spain? Vigo Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 16, 9–30. doi: 10.35869/vial.v0i16.91

Rust, F. (2020). Expansive learning within a teacher’s community of ongoing learners (TCOOL). Front. Educ. 5:67. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00067

Saville-Troike, M., and Barto, K. (2022). Introducing second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sımsek, G., and Capar, M. C. (2024). A comparison of foreign language anxiety in two different settings: online vs classroom. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 25, 289–301. doi: 10.17718/tojde.1245534

Skehan, P. (2009). Modeling second language performance: integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexes. Appl. Linguist. 30, 510–532.

Smith, K. Expansive learning for teacher educators-the story of the Norwegian national research school in teacher education (NAFOL). Front. Educ. 5:43. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00043

Tavakoli, P., and Wright, C. (2020). Second language speech fluency: From research to practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Telor-Reize, D., Ostrizki, L., and Gluck, S. (2023). Living and learning in the next era: Connecting teaching, research and citizenship [conference presentation] ISATT 2023 convention. Bari: ISATT.

Telor-Reize, D., Ostrizki, L., and Gluck, S. (2025). Empowering EFL Pre-Service Teachers Utilizing an Oral Proficiency Intervention.[Manuscript in preparation].

Tessier, V. (2022). Expansive learning for collaborative design. Des. Stud. 83:101135. doi: 10.1016/j.destud.2022.101135

Keywords: educational policies, expansive learning, second language, applied linguistics, speaking, EFL teacher training

Citation: Telor Reize D, Gluck S and Ostrizki L (2025) Change in perspective, change in educational policy. Front. Educ. 10:1588265. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1588265

Edited by:

Samantha Curle, University of Bath, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ali Hamed Barghi, Texas A&M University, United StatesMir Abdullah Miri, University of Bath, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Telor Reize, Gluck and Ostrizki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dorit Telor Reize, ZG9yaXR0ckBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Dorit Telor Reize

Dorit Telor Reize Sandy Gluck

Sandy Gluck Luba Ostrizki

Luba Ostrizki