- 1Department of Curriculum Studies and Higher Education, Faculty of Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 2Faculty of Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 3Department of Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Technology Education, Faculty of Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

A theoretical and empirical grounded explanation is constructed on how primary school principals perceive and enact instructional leadership during curriculum reform. This study used a concurrent mixed-methods design to integrate data from 248 survey responses with insights from in-depth interviews and observations of three school principals. Findings indicate that while principals perceive themselves as actively engaged in instructional leadership, particularly through Principal Instructional Management dimensions in defining school missions, managing instructional programs, and fostering positive school climate—gaps exist between their self-perceptions and enacted practices. Thematic analysis shows that principals influence the establishment of school goals, facilitate instructional collaboration, and reinforce positive behaviors among teachers and learners. However, inconsistencies emerge in data-driven decision-making and direct instructional oversight. Role Perception and enactment in this study demonstrate how personal beliefs, contextual constraints, and systemic challenges influence leadership behaviors in schools. This study exposes the need for structured training, clearer role expectations, and sustained support to enhance principals’ leadership effectiveness. This study contributes to the global discourse on instructional leadership in developing and under-resourced contexts, offering insights for policymakers and educational stakeholders on strengthening leadership frameworks for sustainable curriculum reform.

Introduction

Instructional leadership is broadly recognized as a fundamental element in fostering high-quality teaching and learning across schools globally. This leadership approach is especially relevant in driving educational reforms that seek to reshape conventional teaching and learning methodologies (Hallinger et al., 2020; Ismail et al., 2018). Despite its prominence globally, research on instructional leadership continues to evolve, especially in the context of post-pandemic educational recovery, digital transformation, and equity in under-resourced schools (Ma and Marion, 2024; van der Meer, 2024). However, in Africa, such research remains underexplored (Hallinger, 2019), limiting its ability to contribute to global discourse on contemporary leadership challenges. Curriculum reforms rely heavily on effective school leadership to achieve their objectives (Abdullah et al., 2020; Alsaleh, 2018; Shaked and Schechter, 2019). Consequently, principals are often expected to assume instructional leadership roles that involve overseeing and supporting instructional changes mandated by national curriculum reforms (Bush, 2020). The success of such reforms hinges on principals’ ability to adopt and enact these roles effectively (Alsaleh, 2018; Ganon-Shilon et al., 2020; Loughland and Ryan, 2020). However, many principals face challenges in leading curriculum changes due to inadequate preparation for the instructional leadership responsibilities embedded within these reforms (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Ralebese et al., 2025).

In many contexts, the task of school leadership is often underprioritized in policy and practice, compounded by a lack of preparatory and developmental programs for principals (Pont, 2020; Moorosi and Komiti, 2020). For example, the reform process for Lesotho’s “new” curriculum, introduced in 2013 and improved in 2021, mandates substantial changes to teaching and learning without adequately addressing the leadership capacity required for its successful implementation. According to the Curriculum and Assessment Policy (CAP) of Lesotho, pedagogy must shift toward fostering learners’ creativity, independence, and survival skills. This shift involves moving from traditional teaching to a facilitative approach that prioritizes learning, transitioning from a teacher-centered model focused on knowledge transmission to a student-centered approach that emphasizes knowledge construction. Additionally, it requires replacing rote memorization with the development of advanced thinking skills, such as analysis and synthesis and the practical application of knowledge. Additionally, traditional subject-based instruction must evolve into integrated knowledge approaches, emphasizing participatory and activity-centred methodologies [MoET (Ministry of Education and Training), 2009].

The CAP imposes considerable expectations on principals, requiring them to take on a more engaged instructional leadership role. This shift significantly alters both the responsibilities and working conditions of primary school principals in Lesotho. Yet, research indicates that many principals in Lesotho are underprepared to lead such sweeping changes (Moorosi and Komiti, 2020; Ralebese et al., 2022). This underscores the importance of investigating how principals navigate the complexities of curriculum reform through instructional leadership. Currently, there is a lack of comprehensive knowledge base of how principals in developing countries interpret and fulfil their instructional leadership responsibilities, particularly in contexts where such leadership is not a policy priority and where principals often assume these roles without prior training. To bridge this gap, this study adopts the instructional leadership framework established by Hallinger and Murphy (1985). Their model, which is implemented through the widely recognized Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale (PIMRS), serves as a well-established tool for evaluating principals’ instructional leadership practices (Hallinger and Wang, 2015). This paper builds upon earlier research by Ralebese et al. (2025), which explored principals’ instructional leadership practices during curriculum reform through a single-case lens. The present study expands this inquiry by incorporating a mixed-methods approach to capture broader patterns across multiple schools and data sources.

Literature review

This literature review examines the significance of instructional leadership and its influence on curriculum reform. It is structured into key sections that explore: the theoretical underpinnings of instructional leadership and its evolving function in facilitating curriculum change; the dynamics of teacher-principal interactions and collaborative practices; the challenges and opportunities encountered during curriculum reform; and teachers’ perceptions of their principals’ leadership effectiveness.

The instructional leadership model created by Hallinger and Murphy (1985) offers a research-based framework for comprehending how principals can effectively enhance student achievement. This model is recognized as a seminal contribution to instructional leadership research and remains a key reference in contemporary scholarship (Hallinger et al., 2020; Fromm et al., 2017). Hallinger and Murphy (1985) conceptualized instructional leadership through three fundamental dimensions: developing the school’s mission, managing the instructional program, and promoting a positive school climate. Their framework has been extensively applied across various educational settings, offering valuable insights into the instructional leadership practices of principals.

In Lesotho, where educational reform policies do not explicitly incorporate instructional leadership, this model presents an opportunity to identify principals’ strengths and areas for growth. The three dimensions of this framework are particularly relevant for examining leadership practices within the framework of curriculum reform (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Day et al., 2000).

The first dimension, developing a school’s mission, underscores the necessity for principals to establish and communicate a clear instructional vision. This process entails ensuring the school’s mission aligns with the goals of curriculum reform and ensuring that all stakeholders comprehend the intended direction of teaching and learning (Gurr et al., 2006; Leithwood et al., 2020). The second dimension, managing the instructional program, highlights the principal’s role in overseeing and coordinating collaborative efforts to implement new instructional strategies mandated by reform initiatives. This responsibility entails guiding teachers in adapting their practices to meet evolving educational policies (Hallinger, 2011; Gurr et al., 2006). The third dimension, promoting a positive school climate, emphasizes the principal’s duty to cultivate an environment that supports collaboration and encourages experimentation with innovative teaching approaches (Leithwood et al., 2020).

Collectively, these dimensions provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the leadership strategies essential for effective curriculum reform implementation. In this study, Hallinger and Murphy’s (1985) instructional leadership model serves as the conceptual foundation for examining principals’ perceptions and enactment of this leadership in Lesotho’s curriculum reform context. This model guided the development of research instruments, including interview protocols and structured observations, and informed the analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data.

Research indicates that principals often hold positive views of their instructional leadership abilities, with female principals frequently outperforming their male counterparts due to their extensive classroom experience (Glanz et al., 2017; Hallinger and Lee, 2013). However, other studies have reported low ratings of instructional leadership among principals, often attributed to insufficient training and preparation (Basañes, 2020; Hallinger and Lee, 2013). A lack of formal training in instructional leadership affects principals’ perceived competencies, self-efficacy, and capacity to execute their instructional roles effectively. Paulhus (2017) cautions that individuals completing self-assessment questionnaires may present themselves in a favourable light, potentially introducing bias. To address this, Sinnema et al. (2015) recommends triangulating self-reports with complementary data sources, such as interviews and direct observations, to achieve a more valid and reliable evaluation of leadership practices.

Much research on instructional leadership is important, but it mainly uses survey data. This data often comes from self-reports by principals, which means the conclusions about their practices may not be fully accurate (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Wangchuck and Chalermnirundorn, 2019). While this approach provides valuable insights, it often neglects the deeper, context-specific understanding that can be gained from in-person observations. Grissom et al. (2013) emphasize that direct observation of leadership practices offers critical insights into how principals’ instructional leadership unfolds in real time. Similarly, Spillane et al. (2001) advocate for investigating leadership practice through observation and engaging leaders in discussions about their observed practices. Hallinger and Murphy (2013) contend that instructional leadership must be regarded as a policy imperative, providing a practice-based method to improve instructional quality in schools. However, research linking principals’ perceptions to their enactment of instructional leadership remains limited. This gap is particularly pronounced in developing contexts where curriculum reform is challenged by systemic constraints and evolving teacher expectations. Recent studies suggest that principals’ ability to adapt instructional leadership practices post-COVID-19 is central to sustaining reforms (Anderson and Weiner, 2023; Williams, 2023). Additionally, van der Meer (2024) emphasizes the importance of collaborative leadership and identity alignment in facilitating effective reform implementation.

Theoretical framework

This study utilizes Role Perception Theory (RPT) to examine how principals’ understanding of their roles impacts their leadership approaches and affects the effectiveness of curriculum reforms. According to Role Perception Theory, individuals define their roles based on their beliefs about their responsibilities, tasks, and goals (Parker, 2007). Recent empirical findings support the dynamic nature of role perceptions and their influence on instructional leadership, particularly in contexts of uncertainty and rapid change (Ma and Marion, 2024). These findings reinforce the need for flexible leadership models that acknowledge evolving professional identities and teacher-principal collaboration as critical to reform success. These perceptions are shaped by factors such as personal attitudes, past experiences, and the environment (Robbins and Judge, 2017). In the curriculum reform realm, principals’ perceptions of their roles as instructional leaders are crucial in shaping the success of these initiatives. The RPT highlights how principals’ role perceptions impact their behavior and, consequently, their effectiveness in implementing changes within the school. When principals clearly understand and actively embrace their role in instructional leadership, they are more inclined to interact with teachers, foster collaboration, and distribute resources effectively to facilitate the reform process. These actions are crucial in fostering an environment that supports curriculum innovation and helps overcome potential challenges to reform implementation.

Furthermore, Role Perception Theory emphasises the dynamic nature of role perceptions, which adapts in response to external changes, including implementing curriculum reforms (Grant and Hofmann, 2011). Principals who perceive themselves as active change agents of change are more likely to manage the complexities of these reforms with confidence and strategic direction. Conversely, those with ambiguous or passive role perceptions may inadvertently impede progress. This dynamic interaction between principals’ self-perceptions and their leadership practices highlights the critical need to explore how role perceptions influence the effectiveness of curriculum reform initiatives.

Additionally, this study utilized Role Theory to explore how principals implement instructional leadership practices. Role theory, developed by Robert Merton in 1957, posits that individuals’ behaviors are shaped by the roles they hold within social structures and the expectations linked to those roles. Social roles, such as “teacher” or “customer,” guide behavior by providing a framework for how individuals should act within different social contexts (Morrow-Howell and Greenfield, 2016). These roles, aligned with societal norms, not only help people navigate interactions but also offer access to resources, status, and security, enhancing one’s identity and well-being (Aartsen and Hansen, 2020). As individuals take on new roles, they adjust their behaviors to meet the associated expectations, demonstrating that behavior is flexible and context- dependent (Newman and Newman, 1995), emphasizing the dynamic interaction between roles and individual conduct.

As a social position, principalship comes with distinct role expectations and norms that individuals are expected to uphold when assuming this leadership role. This role instils a sense of security and ego-gratification and may motivate leaders to take on leadership responsibilities, sometimes even without formal training. Consistent with Role Theory, we argue that the instructional leadership practices demonstrated by the principals in this study are shaped by the social norms and expectations associated with their role, particularly because neither leadership framework nor systemic support for principals exists in Lesotho.

Problem statement

The success of curriculum reforms in schools heavily depends on the effectiveness of principals’ instructional leadership, as principals play a pivotal role in guiding, supporting, and motivating teachers to adopt new instructional practices (Hallinger, 2011; Leithwood et al., 2020). While the instructional leadership model provides a robust framework for assessing leadership effectiveness (Alsharija and Watters, 2021; Karacabey et al., 2022), principals often face significant challenges in fulfilling this role. These challenges are particularly acute in developing countries, where limited resources, inadequate professional development, and insufficient systemic support hinder their capacity to effectively implement curriculum reforms (Mphutlane, 2018; Manaseh, 2016). Scholars such as Chabalala and Naidoo (2021) and Fairman et al. (2023) argue that these barriers undermine the effectiveness and overall success of curriculum reforms. Existing research on instructional leadership is usually premised around either quantitative or qualitative approaches to investigation, possibly leading to a fragmented understanding of the phenomenon (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Wangchuck and Chalermnirundorn, 2019). Mixed-methods studies by design offer a more holistic and integrated insight into instructional leadership (Fetters, 2018; Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). Furthermore, few studies have explored the connection between principals’ role perceptions and their instructional leadership practices, particularly within the context of curriculum reform. Scholars highlight that this gap is particularly in resource-limited settings where principals must manage systemic challenges with insufficient support (Shaked, 2020).

This study seeks to bridge this gap by employing a concurrent mixed-methods approach to investigate principals’ perceptions of their instructional leadership roles and how they implement leadership practices during curriculum reform in Lesotho. By providing a theoretical and empirical explanation of these perceptions and practices, this research aims to enhance global insight into instructional leadership in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, it aims to emphasize the significance of incorporating instructional leadership frameworks into educational reform policies. According to the literature, this enhances the effectiveness and sustainability of curriculum reforms (Goldring et al., 2020; Shaked, 2020). By bridging the theoretical understanding of instructional leadership with empirical observations of its enactment, the findings contribute to the broader knowledge base and inform future policy and practice in Lesotho and beyond.

Study aim

How can principals’ perceptions and enactment of instructional leadership for curriculum reform in Lesotho be understood and explained? By addressing this question, the study aims to contribute to the global literature on instructional leadership while informing policy directions and professional development initiatives that could better equip principals for their pivotal roles in educational reform.

Based on the aim of this study, the following research question emerged:

1. How do principals perceive and enact their instructional leadership roles and its alignment with practices using PIMRS dimensions during curriculum reform?

Methodology

This paper is drawn from a larger mixed-methods study that examined the instructional leadership roles of primary school principals during curriculum reform in Lesotho. The study adopted concurrent mixed methods whereby quantitative and qualitative data sets were generated and analysed and the findings were compared. First, a survey within the descriptive design of quantitative research was employed to analyse principals’ perceptions of their instructional leadership practices in the context of curriculum reform in Lesotho. Secondly, a descriptive qualitative case study was used to investigate and illustrate how principals in Lesotho exercised instructional leadership while implementing curriculum reform, highlighting their unique viewpoints and actions within a specific cultural and educational context. The design brings breadth and depth of understanding of how principals facilitate the implementation of curriculum reform through instructional leadership (Fetters, 2018; Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017).

Sampling procedure

Mixed-methods studies incorporate non-probability and probability sampling techniques (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). For the quantitative phase, the sample included 248 primary school principals from ten districts in Lesotho. A stratified random sampling technique was employed, with each district serving as a stratum for proportional representation. Within districts, convenience sampling was used to select accessible principals, while snowball sampling identified additional participants through referrals. An online questionnaire created via Google Forms facilitated participation for principals in remote or hard-to-reach schools, with completed responses securely sent to the principal researcher’s email. For the qualitative phase, a purposive sampling technique was employed to select participants for semi-structured interviews and observations. Three principals from the Maseru district of Lesotho were chosen due to convenience and accessibility, as one of the researchers resides in this district and could easily contact participants and gatekeepers. This non-randomisation of participants allowed the researcher to intentionally select cases that would provide rich and comprehensive data (Cohen et al., 2018). Only principals with at least 4 years of experience leading the reform implementation in their schools were eligible for inclusion, ensuring they had sufficient experience to provide valuable insights.

To enhance methodological transparency, it is important to note that a purposive sampling technique was used for the direct observations during the qualitative phase. Principals were selected based on accessibility, willingness to participate, and leadership experience with curriculum reform implementation. This deliberate sampling strategy ensured that data were collected from experienced instructional leaders within the Maseru district who could provide rich, context-specific insights.

Instrumentation

To ensure data relevance and alignment with the study’s conceptual framework, the quantitative data collection employed a widely validated version of the PIMRS (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Hallinger and Wang, 2015). However, the qualitative instruments—the semi-structured interview protocol and observation blocks—were not subjected to prior formal validation. To mitigate this, the interview questions and observation items were developed based on the three PIMRS dimensions and reviewed by two experts in educational leadership for face and content validity. These instruments included thematic blocks that explored principals’ practices in (1) defining school mission, (2) managing instructional programs, and (3) fostering a positive school climate. Examples of guiding questions included: ‘How do you communicate instructional goals to your teachers?’ and ‘In what ways do you support professional development within your school?’

At the quantitative data collection phase, PIMRS (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Hallinger and Wang, 2015) was adopted to gather principals’ perceptions. The questionnaire contained 20 items aligned with the study’s framework, categorized into three dimensions: Developing a School Mission (5 items), Managing the Instructional Program (6 items), and Promoting a Positive School Climate (9 items). Principals rated how often they performed specific instructional leadership behaviors on a Likert scale (1–5), where 1 indicated “almost never” and 5 indicated “almost always.” Mean scores were interpreted using the following ranges: 1.00–2.50 (low level), 2.51–3.50 (moderate level), and 3.51–5.00 (high level). The qualitative data collection phase involved two instruments aligned with the three PIMRS dimensions to explore how principals implement instructional leadership in the context of curriculum reform. First, a semi- structured interview protocol captured in-depth insights on how principals- (1) develop their school mission, (2) manage instructional program, and (3) promote a positive school climate. Each interview, lasting about 45–60 min, took place in a quiet school setting to maintain privacy and ensure the participants’ comfort. The semi-structured format allowed for probing and the exploration of emergent themes.

Second, an observation protocol guided direct observations of principals. These observations also focused on the three PIMRS dimensions. The observations sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of how principals implement instructional leadership amid curriculum reform. Each principal participated in semi-structured interviews to outline their daily leadership practices. Then, each principal was observed in action, noting leadership activities, interactions, and contexts. Post- observation interviews provided additional clarity and depth to the data by incorporating the principals’ perspectives. Each observation session lasted 30 to 45 min and occurred at least three times per principal to capture a diverse range of activities. Observation notes were recorded during and after each session to ensure a detailed account of principals’ behaviors, interactions, and practices. Interview and observation data were stored in separate, appropriately named file locations for analysis.

Data analysis

To enhance clarity in the presentation of qualitative findings, each interview participant was assigned a pseudonym code (e.g., P1, P2, P3). These identifiers are used consistently throughout the data tables and narrative excerpts to preserve anonymity while enabling clear linkage between responses and themes. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS software to produce descriptive statistics, such as means and standard deviations, to provide an overview of principals’ responses. A t-test was also employed to examine potential gender differences in principals’ perceptions of their instructional leadership roles. These statistical methods provided a structured overview of how principals perceive their leadership practices concerning curriculum reform and implementation, focusing on the frequency and intent of specific behaviors. For qualitative data, the framework proposed by Lester et al. (2020) was utilized in the following manner. Interview recordings and observation notes were organized, transcribed word-for-word, and stored digitally. The data was reviewed multiple times to develop familiarity, with notes taken to highlight key statements and themes related to instructional leadership practices. Thematic analysis was used, with the three PIMRS dimensions serving as predetermined themes. Descriptive codes were applied to relevant data segments to illustrate how principals implemented instructional leadership. The descriptive statements were supported by quotations from interviews and notes taken during observations. The final stage entailed validating these statements by comparing them with existing literature to ensure the findings are based on evidence and relevant to the context.

Trustworthiness

A mixed-methods approach combines quantitative data (via questionnaires) and qualitative data (via interviews and observations), allowing for cross-verification of findings from multiple sources. This approach strengthens the validity and reliability of the research by corroborating evidence from diverse datasets. The use of the validated PIMRS questionnaire ensured that the quantitative instrument is both reliable and contextually appropriate for measuring instructional leadership behaviors (Hallinger and Lee, 2013; Hallinger and Wang, 2015). Prolonged engagement with participants during observations (over multiple days) ensured that comprehensive data on principals’ instructional leadership was gathered. Detailed descriptions of data collection and analysis procedures provide transparency and allow replication or evaluation of the process. Utilizing a thematic framework grounded in established dimensions of instructional leadership (PIMRS) ensures consistency in qualitative data interpretation. Rich, detailed descriptions of the study context, sampling procedures, and participants’ characteristics may help readers assess the applicability of the findings to other similar contexts. Direct quotes from interviews and observation notes are used to substantiate findings, ensuring that interpretations are rooted in the data. The researchers’ decisions are documented, allowing external reviewers to trace the analysis process and verify the alignment of findings with the data.

Ethical considerations

Ethical protocols were strictly followed both before and during data collection. The Lesotho’s Ministry of Education and Training granted the permission to conduct this research. The research’s ethical clearance was sought from the University of the Free State (Ethical Clearance number: UFS-HSD2021/1358/21/22). Additionally, permission to adopt the PIMRS instrument was requested from Philip Hallinger. Ethical considerations included ensuring participants’ anonymity, maintaining the confidentiality of their responses, and guaranteeing voluntary participation (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

Results and discussion

This section presents the findings from the concurrent analysis of the quantitative and qualitative datasets. The aim here is to present results and discuss findings within existing literature. The presentation is organized around three main predetermined themes derived from the PIMRS model: Developing a School Mission, Managing the Instructional Program, and Promoting a Positive School Climate.

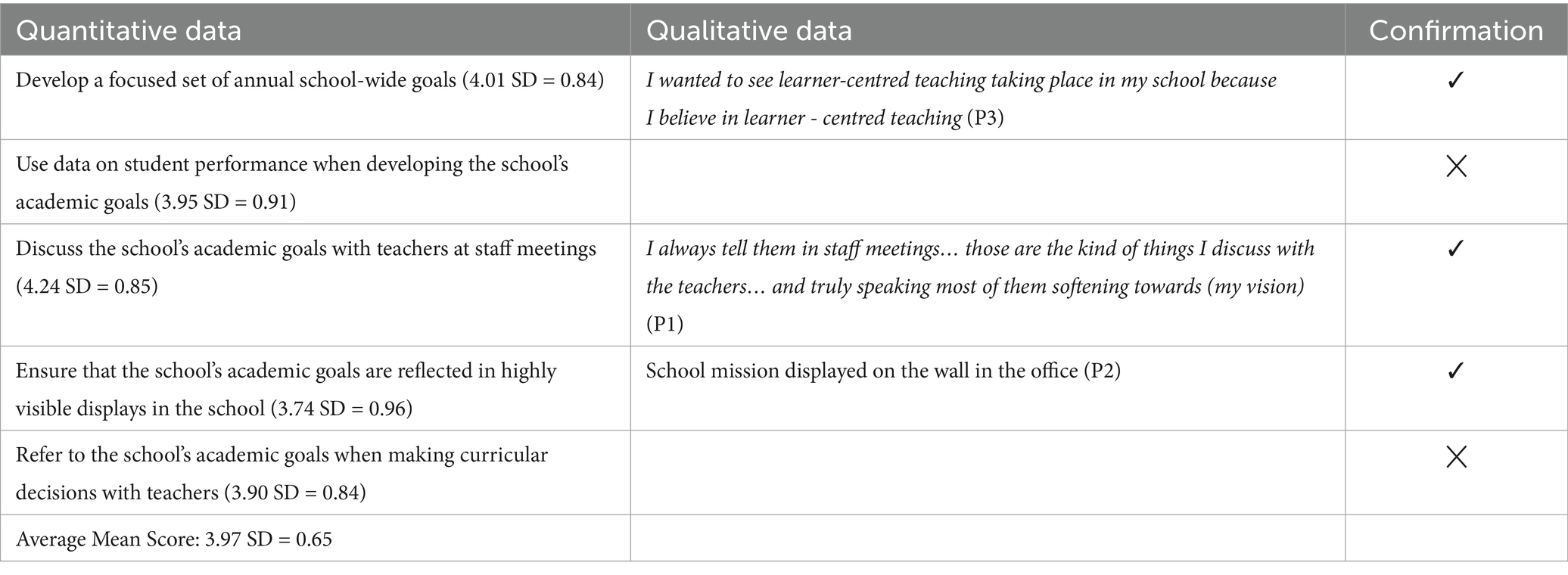

To address the research question of how principals perceive and enact instructional leadership roles and their alignment with practices during curriculum reform, the quantitative and qualitative findings were compared (see Table 1).

Developing school mission

Developing a focused set of annual school-wide goals had a mean score of 4.01 (SD = 0.84), indicating that principals perceive this leadership task to be crucial. Interviews further reveal that principals actively develop school missions centred on key educational goals. One principal stated, “I wanted to see learner-centred teaching taking place in my school because I believe in learner-centred teaching.” Another emphasized the holistic development of students, reading from the mission statement displayed in the school office. The high mean score suggests that principals have confidence in their ability to set focused, school-wide goals. This perception aligns with qualitative data, where principals articulate clear, mission-driven objectives aimed at fostering learner-centred approaches and holistic student development. Within the context of reforms, goal setting appears to be a priority in aligning instructional efforts with reform initiatives.

Additionally, a mean score of 3.74 (SD = 0.96) was recorded for ensuring the visibility of academic goals, reinforcing principals’ belief in displaying school goals. However, only one principal explicitly demonstrated this by having a mission statement displayed in the office, while others described their school mission more abstractly. The task of discussing academic goals with teachers at staff meetings had the highest mean score in this dimension (4.24 SD = 0.85), indicating it as a prevalent leadership practice. Interviews confirmed this enactment, with one principal explaining, “I always tell them in staff meetings… those are the kind of things I discuss with the teachers.” This highlights a strong alignment between perception and practice, as principals consistently communicate school goals with teachers.

Despite positive self-ratings, no evidence of enactment was found for using student performance data when setting academic goals (3.95 SD = 0.91) or referring to school goals when making curricular decisions (3.90 SD = 0.84). While principals viewed these tasks positively, their lack of implementation suggests that certain instructional leadership functions remain more rhetorical than enacted. This discrepancy may impact the effective implementation of reform initiatives. Overall, the quantitative findings show that principals have positive perceptions of Developing a School Mission (mean score = 3.97; SD = 0.65). The qualitative results reinforce these findings by illustrating the various ways principals implement this leadership dimension.

These findings collectively demonstrate how principals’ perceptions of the school mission influence their implementation of that mission. Additionally, positive perceptions and the practices they enact suggest that principals actively shape their schools’ missions. Other research indicates that clearly defining and communicating the school mission is crucial for successful reform (Hallinger and Lee, 2013). The role of principals in setting and reinforcing a clear school mission is fundamental to instructional leadership. Research by Hallinger and Murphy (1985) highlights that a well-defined school mission provides a strategic framework for guiding teaching and learning. Bush (2018) supports this, emphasizing that principals who actively engage teachers in goal-setting foster a shared vision that enhances curriculum reform efforts. However, challenges arise when mission statements lack tangible implementation strategies (Hallinger and Wang, 2015). In this study, while principals demonstrated positive perceptions in setting school goals, gaps existed in using student performance data to inform mission-related decisions. This aligns with findings from Goldring et al. (2020), who argue that data-driven goal setting is crucial for instructional leadership effectiveness but is often underutilized. Seemingly, these principals possess considerable confidence in their abilities as instructional leaders. According to Skaalvik (2020), the perceived self-efficacy of principals in instructional leadership predicts their performance and motivation to carry out their instructional responsibilities. As a result, they proactively handle situations unprepared for, due to their calibre which entails their beliefs, knowledge, and commitment when developing school missions (see Table 1).

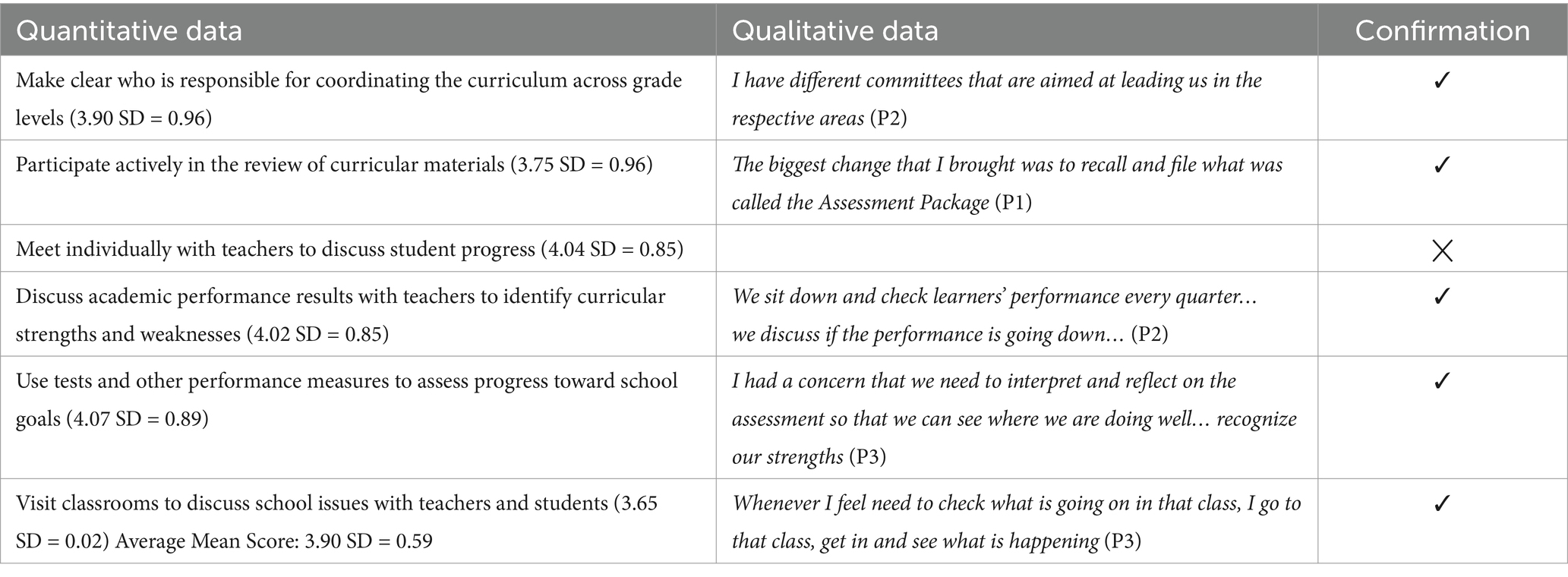

Managing the instructional program

The first leadership task in this dimension, clarifying who is responsible for coordinating the curriculum across grade levels, received a mean score of 3.90 (SD = 0.96), indicating that most principals rated themselves favourably in executing this task. The qualitative findings suggest that principals delegate this responsibility to teacher-led committees overseeing various curricular areas. P2 highlighted this approach, stating, “I have different committees that are aimed at leading us in the respective areas.” The alignment between perception and practice suggests that principals actively establish structured roles for curriculum coordination. The second task, participating actively in the review of curricular materials, produced a mean score of 3.75 (SD = 0.96), demonstrating a relatively positive perception among principals. P1 provided evidence of enactment by discontinuing the use of outdated assessment materials: “The biggest change that I brought was to recall and file what was called the Assessment Package.” This finding suggests that principals are likely to act upon their beliefs when reviewing and refining curricular resources. The third task, meeting individually with teachers to discuss student progress, scored 4.04 (SD = 0.85), showing strong perceived engagement. However, the absence of qualitative confirmation indicates that, while principals may recognize the importance of these interactions, they may not consistently implement them in practice. This gap highlights an area for potential improvement in ensuring direct instructional support.

Discussing academic performance results with teachers to identify curricular strengths and weaknesses received a high mean score of 4.02 (SD = 0.85). P2 confirmed this task’s implementation, explaining, “We sit down and check learners’ performance every quarter… we discuss if the performance is going down.” This demonstrates that principals perceive and enact this responsibility, emphasizing the role of data- driven discussions in instructional leadership. The use of tests and other performance measures to assess.

progress toward school goals received the highest mean score of 4.07 (SD = 0.89). P3 reinforced this perception, stating, “I had a concern that we need to interpret and reflect on the assessment so that we can see where we are doing well… recognize our strengths.” This suggests that principals actively integrate assessment data into their leadership strategies to track school-wide progress. The final task in this dimension, visiting classrooms to discuss school issues with teachers and students, had the lowest mean score of 3.65 (SD = 0.02). Despite this, qualitative evidence from P3 illustrated engagement: “Whenever I feel the need to check what is going on in that class, I go to that class, get in, and see what is happening.” This suggests that while principals recognize the importance of classroom visits, the frequency and consistency of this practice may vary. Generally, principals have positive perceptions regarding their role in managing the instructional program, as indicated by an average mean score of 3.90 (SD = 0.59). The qualitative data largely supports these perceptions, particularly in curriculum coordination, data-driven discussions, and assessment utilization. However, gaps remain in the enactment of individualized teacher meetings and classroom visits, indicating areas for further development in instructional leadership practices.

The active involvement of principals in this dimension suggests that they recognize and fulfil their role in overseeing the instructional changes brought about by reforms to maintain high instructional quality as supported by Horng et al. (2010). This also demonstrates principals’ commitment to coordinating and supervising curriculum-related activities, which is essential for transforming teaching and learning practices. Principals actively engage in overseeing curriculum coordination and performance assessments, aligning with Hallinger and Wang (2015), who highlight the importance of structured instructional leadership practices. Grissom et al. (2013) further argue that principals who engage directly in teacher professional development contribute to improved instructional outcomes. However, gaps were noted in individual teacher consultations on student progress, which suggests that some principals may struggle with balancing administrative duties with instructional leadership. This aligns with Sebastian et al. (2018), who found that time constraints and competing responsibilities often limit direct instructional oversight by school leaders (see Table 2).

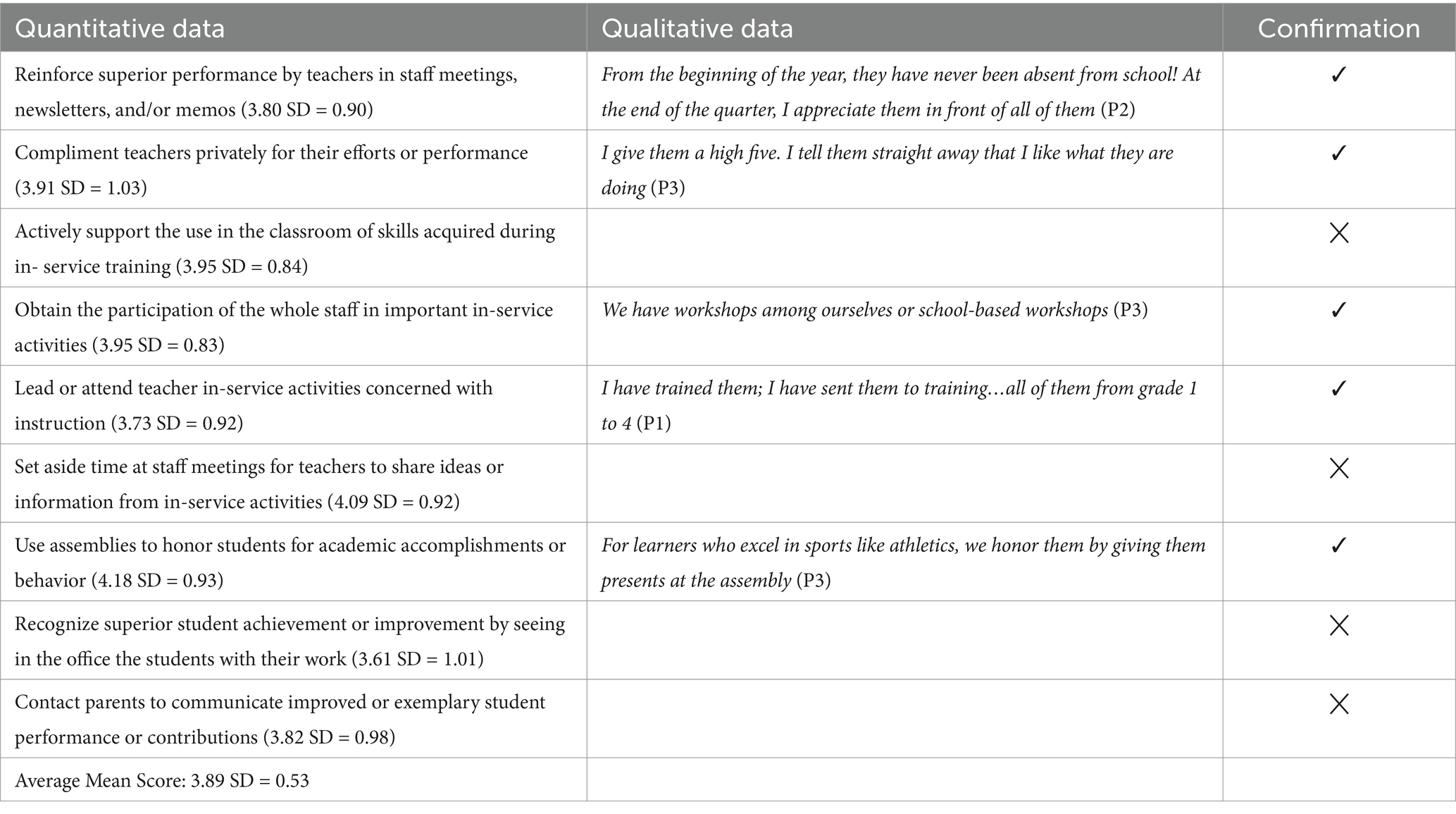

Promoting a positive school climate

The first leadership task in this dimension, reinforcing superior performance by teachers in staff meetings, newsletters, and/or memos, had a mean score of 3.80 (SD = 0.90). The qualitative data confirmed that principals actively implemented practices aligned with this task. P2 illustrated this by stating, “From the beginning of the year, they [teachers] have never been absent from school! At the end of the quarter, I appreciate them in front of all of them. “These findings highlight principals’ efforts to maintain teacher motivation by publicly recognizing their commitment. The second task, complimenting teachers privately for their efforts or performance, received a mean score of 3.91 (SD = 1.03), indicating a strong positive perception among principals. P3 supported this, stating, “I give them a high five. I tell them straight away that I like what they are doing.” This demonstrates that principals acknowledge and reinforce exceptional teacher performance through direct and immediate recognition. The third task, obtaining the participation of the whole staff in important in-service activities, had a mean score of 3.95 (SD = 0.83), showing a favourable perception of this task. P3 provided qualitative support, explaining, “We have workshops among ourselves or school-based workshops.” This alignment suggests that principals actively foster professional development through structured learning opportunities.

The fourth task, leading or attending teacher in-service activities concerned with instruction, scored 3.73 (SD = 0.92). P1 reinforced this perception, stating, “I have trained them; I have sent them to training… all of them from grade 1 to 4.” This indicates that principals engage in professional development to enhance instructional leadership. The fifth task, using assemblies to honour students for academic accomplishments or behavior, had the highest mean score of 4.18 (SD = 0.93). P3 confirmed this practice by stating, “For learners who excel in sports like athletics, we honour them by giving them presents at the assembly.” These findings suggest that principals actively use assemblies as a platform to acknowledge and reward student achievement. Despite alignment in most tasks, two leadership activities related to in-service training lacked qualitative confirmation. Supporting the use of in-service training skills in the classroom (mean score: 3.95, SD = 0.84) and setting aside time at staff meetings for teachers to share insights from in-service training (mean score: 4.09, SD = 0.92) were perceived positively. However, qualitative evidence was found to support their enactment. This suggests that time constraints may limit follow-ups on professional development activities.

Similarly, recognizing superior student achievement by inviting students to the office with their work had a mean score of 3.61 (SD = 1.01) but lacked qualitative support. A comparatively high standard deviation shows varied responses, implying that some principals rated themselves lower on this task. This discrepancy indicates inconsistencies in implementation. The final task, contacting parents to communicate improved or exemplary student performance or contributions, had a mean score of 3.82 (SD = 0.98) but was not supported by qualitative findings. This suggests that while principals value engaging with parents regarding student success, they may have limited opportunities to do so. Overall, the mean score for this dimension was 3.89 (SD = 0.53), reflecting principals’ positive perceptions of their efforts in promoting a positive school climate. The qualitative data largely confirmed these perceptions, indicating a strong commitment to fostering an encouraging and supportive environment. A positive school climate enables teachers to perform at their best, creating a nurturing space that benefits both staff and students.

A supportive school climate is essential for fostering both teacher and student success. One of the findings in this study indicates that principals prioritize teacher recognition and student reward systems. This supports research by Liu et al. (2021), who argue that positive reinforcement contributes to teacher motivation and student engagement. However, the lack of parental involvement identified in this study contradicts arguments by Ombonga and Ongaga (2017), who emphasize that school-home communication plays a vital role in sustaining student achievement. A positive and supportive environment helps teachers perform at their highest potential (Anderson and Weiner, 2023). With this practice, principals create a community where teachers feel appreciated and supported, which in turn contributes to the overall success of school reform efforts. Such a positive school climate not only enhances teacher satisfaction and well- being but also improves student outcomes (Liu et al., 2021). This suggests the need for structured parental engagement strategies to enhance collaboration between schools and families (see Table 3).

Conclusion

This study examined how principals perceive and enact their instructional leadership roles in three key dimensions: developing a school mission, managing the instructional program, and promoting a positive school climate. The findings reveal that while principals generally perceive themselves as effective instructional leaders, inconsistencies exist between their perceived and actual practices across these dimensions. In developing a school mission, principals demonstrated a strong commitment to setting school-wide goals and ensuring the visibility of the mission. However, gaps were noted in using student performance data to inform decision-making, indicating the need for a more data-driven approach to mission development. Regarding managing instructional the program, principals actively engaged in curriculum coordination, assessment utilization, and professional development initiatives. However, inconsistencies in direct teacher consultations on student progress suggest that instructional leadership responsibilities may sometimes be overshadowed by administrative duties. In promoting a positive school climate, principals were effective in reinforcing teacher performance and student achievements, creating a supportive environment. However, challenges in parental engagement and follow-ups on in-service training highlight areas that require further attention to enhance school-community collaboration and professional development sustainability. Overall, while principals perceive themselves as strong instructional leaders, strategic interventions may be needed to bridge the gap between perception and enactment. Future professional development programs may focus on strengthening data- informed decision-making, fostering deeper teacher-principal collaboration, and improving school-home partnerships to ensure a holistic approach to instructional leadership. Addressing these areas may enhance the effectiveness of principals in guiding curriculum reform and improving educational outcomes in schools.

Recommendations

This study recommends structured training to help principals better understand and implement effective instructional leadership practices. While principals feel confident in their roles, formal training can enhance their skills in managing curriculum changes based on best practices. Recent findings by Anderson and Weiner (2023) emphasize that post-pandemic school reform requires leaders who are prepared to address both pedagogical innovation and social–emotional needs. In under-resourced contexts like Lesotho, leadership training should be contextually responsive and informed by both global best practices and local realities (Williams, 2023). Additionally, better support systems are needed to offer resources, mentorship, and continuous professional development for sustained reform efforts. These systems should be embedded into broader education policy frameworks to ensure their scalability and sustainability. Ma and Marion (2024) highlight the role of school leadership in fostering effective collaboration and adaptability among staff, particularly when implementing systemic change. Support initiatives that promote distributed leadership models could further strengthen principals’ capacity to lead instructional improvement across diverse school settings.

Furthermore, clearer expectations and formal guidelines for principals’ leadership roles are essential, especially in contexts like Lesotho where such frameworks are often undefined. Establishing role-specific policies would help reduce ambiguity, improve accountability, and empower principals to make informed decisions. Van der Meer (2024) argues that aligning role perceptions with institutional expectations is key to improving both leadership performance and school outcomes. Finally, there is a need for continuous professional dialogue and policy engagement around instructional leadership. Ministries of education and teacher training institutions should collaborate to co-design training that equips school leaders with data literacy, curriculum management, and relational leadership skills — all of which are foundational for effective reform leadership. Future studies could expand the sample size and geographical coverage to include diverse school districts beyond Maseru, thereby enhancing generalizability. Longitudinal research may also be valuable in tracking the evolution of principals’ instructional leadership practices over the course of curriculum reform implementation. Additionally, comparative studies across developing countries could help identify context-specific versus universal leadership challenges and strategies. It would also be useful to conduct intervention studies that evaluate the impact of targeted training or support systems on principals’ leadership behaviors and school improvement outcomes.

Study limitations

While the study provides important insights into principals’ instructional leadership during curriculum reform, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the qualitative component involved only three principals from one district, which limits the generalizability of the findings across the broader national context. Second, the reliance on self-reported data in surveys and interviews may introduce social desirability bias, potentially overstating principals’ perceived leadership engagement. Although observations were included to triangulate findings, these were limited in scope and time. Third, the interview and observation instruments, while aligned with the PIMRS dimensions, were not formally validated prior to data collection. Future research involving larger, more diverse samples and validated tools would provide a more robust foundation for generalization and deeper analysis.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by General/Human Research Ethics Committee University of the Free State Bloemfontein South Africa. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. OB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by funding from the SANRAL Chair in Science and Mathematics Education in the University of the Free State.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1591106/full#supplementary-material

References

Aartsen, M., and Hansen, T. (2020). Social participation in the second half of life. Encyclopedia of Biomedical Gerontology, ed. S. I. S. Rattan (Oxford: Academic Press) 247–255. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.11351-0

Abdullah, J. B., Suprammaniam, S. S., Mohamed, N. A. S., and Yusof, S. I. M. (2020). The relationship of instructional leadership towards teachers’ development through instructional coaching among Malaysian school leaders. Int. Educ. Res. 3:9. doi: 10.30560/ier.v3n2p9

Alsaleh, A. (2018). Investigating instructional leadership in Kuwait's educational reform context: School leaders’ perspectives. School Leadersh. Manag. 39, 96–120. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2018.1467888

Alsharija, M., and Watters, J. J. (2021). Secondary school principals as change agents in Kuwait: principals’ perspectives. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 49, 883–903. doi: 10.1177/1741143220925090

Anderson, A. M., and Weiner, J. M. (2023). Equity-oriented leadership and post-pandemic schooling: Leading through uncertainty and complexity. Educ. Adm. Q. 59, 3–31.

Basañes, R. A. (2020). Instructional leadership capacity of elementary school administrators. Glob. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. Rev. 8, 113–123. doi: 10.35609/gjbssr.2020.8.2

Bush, T. (2018). Preparation and induction for school principals: Global perspectives. Manag. Educ. 32, 66–71. doi: 10.1177/0892020618761805

Bush, T. (2020). “How does Africa compare to the rest of the world?” in Preparation and development of school leaders in Africa. eds. P. Moorosi and T. Bush (New York: Bloomsbury Academic), 179–196.

Chabalala, G., and Naidoo, P. (2021). Teachers' and middle managers' experiences of principals' instructional leadership towards improving curriculum delivery in schools. S. Afr. J. Child. Educ. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.4102/sajce.v11i1.910

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn. London: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th Edn. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Day, C., Harris, A., Hadfield, M., Tolley, H., and Beresford, J. (2000). Leading schools in times of change. London: Open University Press.

Fairman, J. C., Smith, D. J., Pullen, P. C., and Lebel, S. J. (2023). The challenge of keeping teacher professional development relevant. Prof. Dev. Educ. 49, 197–209. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1827010

Fetters, M. D. (2018). Six equations to help conceptualize the field of mixed methods. J. Mixed Methods Res. 12, 262–267. doi: 10.1177/1558689818779433

Fromm, G., Hallinger, P., Volante, P., and Wang, W. C. (2017). Validating a Spanish version of the PIMRS: Application in national and cross-national research on instructional leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 45, 419–444. doi: 10.1177/1741143215617948

Ganon-Shilon, S., Tamir, E., and Schechter, C. (2020). Principals’ sense-making of resource allocation within a national reform implementation. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 49, 921–939. doi: 10.1177/1741143220921191

Glanz, J., Shaked, H., Rabinowitz, C., Shenhav, S., and Zaretsky, R. (2017). Instructional leadership practices among principals in Israeli and US Jewish schools. Int. J. Educ. Reform 26, 132–153. doi: 10.1177/105678791702600203

Goldring, E., Grissom, J., Neumerski, C. M., Blissett, R., Murphy, J., and Porter, A. (2020). Increasing principals’ time on instructional leadership: Exploring the SAM® process. J. Educ. Adm. 58, 19–37. doi: 10.1108/JEA-07-2018-0131

Grant, A. M., and Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Role Expansion as a Persuasion Process. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 1, 9–31. doi: 10.1177/2041386610377228

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., and Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educ. Res. 42, 433–444. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13510020

Gurr, D., Drysdale, L., and Mulford, B. (2006). Models of successful principal leadership. School Leadersh. Manag. 26, 371–395. doi: 10.1080/13632430600886921

Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Adm. 49, 125–142. doi: 10.1108/09578231111116699

Hallinger, P. (2019). Science mapping the knowledge base on educational leadership and management in Africa, 1960–2018. School Leadersh. Manag. 39, 537–560. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2018.1545117

Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S., and Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2020). Are principals instructional leaders yet? A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics 122, 1629–1650. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03360-5

Hallinger, P., and Lee, M. (2013). Exploring principal capacity to lead reform of teaching and learning quality in Thailand. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 33, 305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.03.002

Hallinger, P., and Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. Elem. Sch. J. 86, 217–247. doi: 10.1086/461445

Hallinger, P., and Murphy, J. F. (2013). Running on empty? Finding the time and capacity to lead learning. NASSP Bulletin 97, 5–21. doi: 10.1177/0192636512469288

Hallinger, P., and Wang, W. C. (2015). Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management Rating scale. Cham: Springer.

Horng, E. L., Klasik, D., and Loeb, S. (2010). Principal's time use and school effectiveness. Am. J. Educ. 116, 491–523. doi: 10.1086/653625

Ismail, S. N., Don, Y., Husin, F., and Khalid, R. (2018). Instructional leadership and teachers' functional competency across the 21st-century learning. Int. J. Instr. 11, 135–252. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.11310a

Karacabey, M. F., Bellibaş, M. Ş., and Adams, D. (2022). Principal leadership and teacher professional learning in Turkish schools: Examining the mediating effects of collective teacher efficacy and teacher trust. Educ. Stud. 48, 253–272. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1749835

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadersh. Manag. 40, 5–22. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

Lester, J. N., Cho, Y., and Lochmiller, C. R. (2020). Learning to do qualitative data analysis: A starting point. Hum. Resour. Dev. 19, 94–106. doi: 10.1177/1534484320903890

Liu, Y., Bellibaş, M. Ş., and Gümüş, S. (2021). The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 49, 430–453. doi: 10.1177/1741143220910438

Loughland, T., and Ryan, M. (2020). Beyond the measures: The antecedents of teacher collective efficacy in professional learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 48, 343–352. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1711801

Ma, X., and Marion, R. (2024). How does leadership affect teacher collaboration? Evidence from teachers in US schools. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 35, 116–141. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2024.2330533

Manaseh, M. A. (2016). Instructional leadership: The role of heads of schools in managing the instructional programme. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 4, 30–47. doi: 10.17583/ijelm.2016.1691

Moorosi, P., and Komiti, M. (2020). “Experiences of school leadership preparation and development in Lesotho” in Preparation and development of school leaders in Africa. eds. P. Moorosi and T. Bush (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 37–54.

Morrow-Howell, N., and Greenfield, E. A. (2016). “Productive engagement in later life” in Handbook of aging and the social sciences (Cambridge: Academic Press), 293–313.

Mphutlane, G. G. (2018). Lesotho secondary school principals’ perceptions of their sense of efficacy regarding their managerial competencies. M.Ed., Dissertation National University of Lesotho). Available online at: https://repository.tml.nul.ls/bitstream/handle/20.500.14155/1450/Thesis_Mphutlane_Lesotho_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Newman, B. M., and Newman, P. R. (1995). Development through life: a psychosocial approach. California: Brooks/Cole.

Ombonga, M., and Ongaga, K. (2017). Instructional leadership: a contextual analysis of principals in Kenya and southeast North Carolina. J. Educ. Pract. 8, 169–179.

Parker, S. K. (2007). "That is my job": how employees’ role orientation affects their job performance. Hum. Relat. 60, 403–434. doi: 10.1177/0018726707076684

Paulhus, D. L. (2017). “Socially desirable responding on self-reports” in Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. eds. V. Zeigler-Hill and T. K. Shackelford (New York: Springer), 1–5.

Pont, B. (2020). A literature review of school leadership policy reforms. Eur. J. Educ. 55, 154–168. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12398

Ralebese, M. D., Jita, L., and Badmus, O. T. (2025). Examining Primary School Principals’ Instructional Leadership Practices: A Case Study on Curriculum Reform and Implementation. Educ. Sci. 15:70. doi: 10.3390/educsci15010070

Ralebese, M. D., Jita, L. C., and Chimbi, G. T. (2022). "Underprepared" principals leading curriculum reform in Lesotho. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 7, 861–897. doi: 10.30828/real.1104537

Schoonenboom, J., and Johnson, B. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. Köln. Z. Soziol. Sozialpsychol. 69, 107–131. doi: 10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1

Sebastian, J., Camburn, E. M., and Spillane, J. P. (2018). Portraits of principal practice: Time allocation and school principal work. Educ. Adm. Q. 54, 47–84. doi: 10.1177/0013161X17720978

Shaked, H. (2020). Social justice leadership, instructional leadership, and the goals of schooling. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 81–95. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-01-2019-0018

Shaked, H., and Schechter, C. (2019). School middle leaders’ sense-making of a generally outlined education reform. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 18, 412–432. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2018.1450513

Sinnema, C. E., Robinson, V. M., Ludlow, L., and Pope, D. (2015). How effective is the principal? Discrepancy between New Zealand teachers’ and principals’ perceptions of principal effectiveness. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 27, 275–301. doi: 10.1007/s40869-015-0007-7

Skaalvik, C. (2020). School principal self-efficacy for instructional leadership: relations with engagement, emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 479–498. doi: 10.1007/s11218-020-09544-4

Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., and Diamond, J. B. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educ. Res. 30, 23–28. doi: 10.3102/0013189X030003023

van der Meer, J. (2024). Role perceptions, collaboration, and performance: Insights from identity theory. Public Manag. Rev. 26, 1610–1630. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2023.2203167

Wangchuck, D. K., and Chalermnirundorn, N. (2019). School principals’ perceptions towards instructional leadership practices. A case study from the Southern District of Bhutan. VRU Res. Dev. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 14, 10–22.

Keywords: curriculum reform, instructional leadership, perception, practices of principals, educational leadership

Citation: Ralebese MD, Jita LC and Badmus OT (2025) Perceptions and practices of principals: examining instructional leadership for curriculum reform. Front. Educ. 10:1591106. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1591106

Edited by:

Gisela Cebrián, University of Rovira i Virgili, SpainReviewed by:

William L. Sterrett, Baylor University, United StatesMilan Mašát, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czechia

Alison Cantos Egea, University of Rovira i Virgili, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Ralebese, Jita and Badmus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Moeketsi David Ralebese, ZG1yYWxlYmVzZUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Moeketsi David Ralebese

Moeketsi David Ralebese Loyiso Currell Jita

Loyiso Currell Jita Olalekan Taofeek Badmus

Olalekan Taofeek Badmus