- 1The Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment, Department of Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2Pedagog Christensen Perle Forlag, Oslo, Norway

- 3National Center for Learning Environment, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

Introduction: Inclusive education requires not only systemic change but also direct attention to the classroom experiences of minority students. This study investigates how instructional and emotional support from teachers influence minority students’ perceptions of inclusivity and their academic and emotional engagement.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was employed, involving survey responses from 305 minority students and participant observations across multiple educational settings. Quantitative data were analyzed to identify correlations, while qualitative observations provided contextual depth.

Results: Approximately 7% of students reported receiving little to no instructional or emotional support from teachers. Quantitative analysis revealed significant positive correlations between the level of perceived support and students’ academic engagement and emotional well-being. Observational data reinforced these findings by highlighting inconsistencies in inclusive practices across classrooms.

Discussion: The findings underscore the critical role of both emotional and instructional support in fostering inclusive learning environments. The study advocates for a redefinition of inclusive education that explicitly integrates these support dimensions. It further recommends targeted teacher training and systemic policy interventions to bridge identified gaps and promote equitable learning outcomes for minority students.

Background and rationale

Inclusive education has garnered growing attention as educational systems across the globe grapple with increasing cultural, linguistic, and ethnic diversity in schools. In Norway and other multicultural societies, inclusive education is both a pedagogical approach and a social imperative, aiming to ensure equitable learning opportunities for all students, including those from minority and migrant backgrounds (Kjos et al., 2021; OECD, 2019). Successful implementation of inclusive education depends on several interrelated dimensions, such as emotional and instructional support, adaptive teaching strategies, differentiated instruction, peer-assisted learning, and cooperative pedagogies (Alves et al., 2020; Florian and Black-Hawkins, 2011; Kuyini et al., 2018).

Central to inclusive teaching is the teacher’s role not only as an instructional guide but also as a cultural mediator and emotional anchor for students navigating unfamiliar educational landscapes. Research highlights that teachers’ cultural competence, attitudes toward diversity, and responsiveness to students’ socio-emotional needs are essential in promoting engagement, academic success, and psychosocial well-being (Gay, 2018; Sharma and Loreman, 2020).

In this study, minority students are defined as those with non-Norwegian ethnic or linguistic backgrounds, many of whom come from migrant, refugee, or second-generation immigrant families. These students often speak languages other than Norwegian at home, and their cultural values, migration histories, and social positioning influence how they experience schooling (Bakken, 2019; Vedøy and Møller, 2021). Educational inequalities persist despite inclusive policies, as minority students frequently encounter barriers related to language acquisition, cultural dissonance, and implicit bias in teacher expectations (Bakken and Hyggen, 2023; Lødding, 2015).

The lived experiences of these students remain underexplored in the Norwegian context, particularly regarding how they perceive inclusive practices and the extent to which teachers provide emotional and instructional support. While previous research has addressed inclusion in general terms, relatively few studies have incorporated minority students’ voices to reflect the complexity of their experiences within mainstream educational institutions (Klepp and Dobson, 2020; Nortvedt et al., 2022).

This study is grounded in Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory, which underscores the importance of social interaction, cultural tools, and language in shaping learning. According to this perspective, effective pedagogy must be embedded within students’ cultural and linguistic realities. Emotional support such as affirming student identity and fostering belonging is equally crucial in empowering minority students to navigate academic challenges (Hammond, 2015; van den Bos et al., 2021).

Teachers’ instructional practices must be sensitive not only to linguistic diversity but also to broader socio-cultural differences that shape student engagement and motivation. When inclusive education aligns with students’ lived realities by validating their identities, respecting their heritage languages, and adapting pedagogies to their learning needs—it becomes a transformative force in promoting equity and inclusion (Arnesen et al., 2022; Florian and Spratt, 2013).

By focusing on students’ perceptions, this study aims to advance understanding of how inclusive education is enacted and experienced from the ground up. It interrogates the role of teachers in shaping equitable learning environments and seeks to contribute to a more nuanced and culturally responsive discourse on inclusive education in multicultural societies.

In view of the above this research explores the following research questions:

1. How do minority students perceive inclusive education?

2. What are minority students’ views on the instructional and emotional support provided by their teachers to enhance learning?

Inclusive education and teacher support

Inclusive education is a globally recognized educational approach that ensures all students, irrespective of their backgrounds, abilities, or disabilities, learn together in the same environment. It aims to eliminate barriers to participation, providing equitable access to quality education. The implementation of inclusive education varies across countries, with teachers adapting curricular goals, modifying content, employing multi-level teaching strategies, and utilizing cooperative learning. However, these strategies are applied within policy frameworks that may be either explicit or ambiguous (Næss et al., 2024; Kuyini et al., 2018; Andersen and Thomsen, 2018). In Norway, inclusive education is a core principle, with an emphasis on integrating students with special educational needs (SEN) into mainstream classrooms. Teachers are trained to accommodate diverse learning styles, fostering an inclusive and accepting educational environment. However, challenges persist in differentiating instruction to meet student diversity, requiring close collaboration among educators to ensure equitable learning opportunities and a sense of belonging (Sigstad et al., 2021). Despite a strong political commitment to inclusive education, Norway lacks a standardized definition of inclusion and has limited insights into the efficacy of its commonly implemented inclusive practices for SEN students (Næss et al., 2024). Research indicates that many SEN and minority students are often placed in segregated settings and are taught by educators who may not possess the necessary expertise, paradoxically as a form of support (Næss et al., 2024).

The recognition of inclusive education as a fundamental right has been reinforced through international policy frameworks such as the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994), which has promoted inclusive education across various national contexts. Norway, committed to principles of equity and social justice, has aligned its educational policies with these international directives, particularly in relation to marginalized and minority students (Haug, 2017a; Haug, 2017b). This approach corresponds with UNESCO’s broader vision of creating adaptive and welcoming educational settings (Ainscow, 2007). Within this framework, several competencies and strategies have been identified as crucial for effective implementation, including differentiated instruction (Tomlinson, 2014), culturally responsive teaching (Gay, 2018), the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework (CAST, 2018), collaborative teaching (Friend and Cook, 2016), and social–emotional learning (SEL) competencies such as emotional support, classroom management, and instructional support (CASEL, 2020; Kuyini et al., 2018; Pianta et al., 2008), mostly from teachers point of view with less emphasis or focus on students` views.

The perceptions of minority students regarding inclusive education are significantly influenced by the instructional and emotional support provided by teachers. Studies highlight the positive correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy, attitudes toward inclusion, and the emotional support they offer to students. Research by Mudhar et al. (2024) indicates that teachers with high self-efficacy and a positive disposition toward inclusive education provide greater emotional support, leading to improved student outcomes. Similarly, Uli and Kurniawati (2019) found that teachers’ supportive attitudes contribute to enhanced social skills among SEN students. Furthermore, Hogekamp et al. (2016) emphasize that students’ perceptions of teacher emotional support play a crucial role in their social inclusion and academic development. Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of teacher support in fostering an inclusive learning environment that benefits minority students.

Norway has witnessed increasing student diversity due to immigration, which has introduced challenges related to language barriers, cultural differences, and discrimination, all of which can negatively impact minority students’ academic performance and overall well-being (Bakken, 2019). Despite the Norwegian educational system’s strong emphasis on equality and fairness, research suggests that minority students often perceive a lack of inclusivity in both curriculum content and classroom practices (Lødding, 2015). The effectiveness of inclusive education for minority students in Norway is largely dependent on the instructional and emotional support provided by teachers. Effective educators do not merely deliver subject matter knowledge; they also create emotionally supportive environments that foster a sense of belonging, safety, and respect (Vogt et al., 2019). Studies indicate that minority students who receive substantial emotional support from teachers are more engaged in classroom activities and achieve higher academic performance (Bakken and Elstad, 2012).

Teachers play an essential role in the successful implementation of inclusive education in their effort to support students. Instructional support involves guiding students through the learning process by scaffolding their understanding and providing meaningful feedback to enhance academic performance (Hamre and Pianta, 2006). For example, language modeling which refers to the explicit demonstration of academic language use, vocabulary, grammar, and discourse structures by teachers. It enables students especially English Language Learners (ELLs) or emergent bilinguals to acquire the linguistic tools needed to engage with academic content across subjects (Gibbons, 2015). Emotional support, in contrast, entails fostering a respectful and emotionally secure classroom environment that meets students’ psychological needs. These two dimensions of teacher support significantly influence students’ socio-emotional well-being and academic success (Pianta et al., 2008). In inclusive settings, instructional support is demonstrated through clear explanations, feedback, and scaffolding to enhance comprehension and skill development (Federici and Skaalvik, 2014). Teachers’ emotional support is characterized by warmth, respect, and empathy, ensuring that students feel valued and understood. These aspects can be measured through structured observations and student perception surveys, which assess teacher sensitivity and responsiveness (Hamre et al., 2013).

Norwegian context

While many educators in Norway express strong support for inclusive education in principle, they often lack the necessary training to address the specific needs of minority students, particularly in areas such as language acquisition and cultural adaptation (Haugen, 2017). Additionally, a disconnect exists between policy and practice, as schools frequently struggle to provide adequate support for minority students due to resource constraints and inconsistent teacher competencies (Andersen and Thomsen, 2018). Although Norwegian policies advocate inclusivity, practical challenges persist in fully realizing these ideals.

The perception of teacher support significantly shapes minority students’ academic experiences. For those grappling with language barriers or feelings of exclusion, instructional and emotional support can profoundly impact their engagement and learning outcomes (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2014). Norwegian minority students report varied experiences with teacher support. While some express concerns that their cultural backgrounds are overlooked and that instructional support is insufficient to address their specific learning needs (Lødding, 2015), others highlight positive interactions with teachers who demonstrate cultural awareness and adapt their teaching methods accordingly (Bakken, 2019). The link between teacher support and minority students’ academic performance is well-documented. Bakken and Elstad (2012) found that minority students who perceive high levels of emotional and instructional support exhibit greater motivation and improved academic outcomes. Conversely, inadequate support can exacerbate feelings of isolation and underachievement (Haugen, 2017). These findings emphasize the need for more targeted teacher training and systemic teaching practices as well as support mechanisms to ensure that inclusive education effectively meets the needs of minority students in Norway.

Theoretical framework

This study explores the influence of social and cultural contexts on learning by employing a sociocultural framework, drawing primarily on the theories of Vygotsky and Bronfenbrenner. These frameworks emphasize the interconnected roles of individual, social, and environmental factors in shaping educational experiences, particularly for minority students. Understanding how these contexts interact is crucial for fostering inclusive learning environments and supporting diverse learners effectively (Nasir et al., 2020; Rogoff, 2016).

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory serves as a central lens through which the role of social interaction in cognitive development is examined. Learning, in this perspective, is not an isolated process but is mediated by interaction with more knowledgeable others, including teachers, peers, and family members. These social interactions are vital in scaffolding students’ development of higher mental functions, making the social environment a critical factor in academic success (Vygotsky, 1978; Daniels, 2022).

A key concept within Vygotsky’s theory is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which refers to the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can accomplish with guidance. For minority students adapting to new cultural and linguistic environments, the ZPD highlights the value of personalized support. Instructional scaffolding tailored to cultural and language needs has been shown to improve engagement and learning outcomes (Hammond, 2015; García and Kleifgen, 2018).

Teachers, therefore, play a pivotal role as mediators in students’ learning journeys. Through culturally responsive teaching practices, they help bridge gaps in comprehension and access to curriculum. In Norway, where increasing cultural diversity has challenged monolingual educational traditions, culturally responsive pedagogy has been emphasized as a necessary strategy for inclusion (Andersen and Kulbrandstad, 2022; Hilt, 2017). Emotional and instructional support from educators can mitigate the effects of exclusion and foster a sense of belonging.

To expand the scope beyond the classroom, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a broader framework for understanding the developmental environments of minority students. This theory emphasizes the importance of nested systems—from immediate contexts like home and school to larger societal structures that collectively influence development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006; Tudge et al., 2016). This systems perspective underscores the complexity of inclusive education efforts.

Within the microsystem, the relationship between teachers and students is especially impactful. Research has shown that supportive teacher-student interactions significantly enhance academic motivation and emotional security, particularly among culturally diverse students (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2019; Reyes et al., 2021). A positive classroom climate grounded in trust and mutual respect is foundational to achieving inclusive educational outcomes.

At the macrosystem level, societal values and national educational policies further influence students’ experiences. In Norway, inclusive education is officially supported through policy, yet disparities persist in how these ideals are realized at the classroom level. Studies reveal a disconnect between inclusive policy frameworks and teachers’ preparedness to address the needs of minority learners, pointing to systemic barriers (Haug, 2017a; Haug, 2017b; Lødding and Aamodt, 2015).

Vygotsky’s theory emphasizes that scaffolding should be responsive to the learner’s background and abilities, allowing them to navigate academic content with support. This dynamic process fosters cognitive development and bridges linguistic and cultural gaps, especially when implemented with an understanding of students’ social worlds (Hammond, 2015). Bronfenbrenner’s theory, meanwhile, contextualizes these instructional relationships within broader institutional, political, and societal influences that shape everyday learning (Tudge et al., 2016).

Combining the insights of Vygotsky and Bronfenbrenner offers a more holistic lens for analyzing educational inclusion. While Vygotsky focuses on how interpersonal interactions foster learning, Bronfenbrenner highlights how these interactions are embedded in institutional structures and cultural norms. Together, they reveal how micro-level interventions and macro-level reforms must work in tandem to remove barriers to equitable education (Nasir et al., 2020).

In conclusion, learning is deeply embedded in social, cultural, and environmental contexts. Effective inclusion depends on both immediate classroom practices and the larger systemic structures that support or hinder them. The combined theoretical insights of Vygotsky and Bronfenbrenner offer educators and policymakers a comprehensive approach to fostering environments that support the academic success and emotional well-being of all learners, especially those from minority backgrounds (Rogoff, 2016; García and Kleifgen, 2018).

Materials and methods

Research design

This study employed a mixed-methods design to explore minority students’ perceptions of inclusive education, with particular attention to the emotional and instructional support provided by teachers. The integration of quantitative and qualitative methods allowed for both breadth and depth of understanding, enhancing the validity and contextual richness of the findings (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). Quantitative data were collected through structured surveys to capture self-reported student experiences, while qualitative data were derived from systematic classroom observations, enabling the triangulation of reported perceptions with observed pedagogical practices.

Participants and sampling strategy

The study sample consisted of 305 minority students drawn from five secondary schools and two universities located in Oslo and Akershus, Norway. A stratified random sampling technique was employed to ensure representation across key demographic variables, including educational level, gender, age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background. Eligibility required participants to have resided in Norway for at least 2 years, ensuring sufficient exposure to the Norwegian educational system and avoiding confounding results related to recent migration.

Of the 305 participants, 100 students (32.8%) were from lower secondary schools, 120 (39.3%) from upper secondary schools, and 85 (27.9%) from universities. The gender distribution included 180 females (59%) and 125 males (41%). In terms of age, 210 students (68.9%) were between 16 and 24 years old, 70 students (23.0%) were aged 25 to 33, and 15 students (4.9%) were 34 or older. The final sample size exceeded the minimum threshold identified by an a priori power analysis for detecting medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.5) at α = 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.80 (Faul et al., 2009). This ensured robust inferential analyses and enabled subgroup comparisons across educational levels and demographic categories.

Participant recruitment was facilitated through school and university administrators, who distributed invitations and consent forms. Surveys were made available in both digital and paper-based formats to maximize accessibility and account for varying levels of digital literacy and access. Participation was entirely voluntary, with students provided the opportunity to opt out at any time without penalty.

Instrumentation

Two original survey instruments were developed to assess students’ experiences: the Students’ Perceptions of Inclusive School Practices (SPISP) and the Students’ Perceptions of Instructional and Emotional Support (SPIES). Each instrument contained 15 items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The SPISP scale measured dimensions of inclusive education such as differentiated instruction, curriculum adaptation, cooperative learning, and peer collaboration, grounded in literature on inclusive pedagogical frameworks (Florian and Black-Hawkins, 2011). The SPIES scale assessed the emotional climate of classrooms and the extent of instructional responsiveness shown by teachers, in alignment with frameworks emphasizing teacher support as a critical factor in minority student engagement and academic resilience (Roorda et al., 2011; Gay, 2018).

Instrument development was informed by existing validated measures, including those by Joshi A. et al. (2015) and Joshi M. et al. (2015) and recent findings in the literature on culturally responsive pedagogy. Sample items included “Teachers adapt curricular goals to meet student needs” and “Teachers use positive behavior strategies to encourage learning.” Prior to full implementation, a pilot study involving 30 minority students was conducted to evaluate item clarity, face validity, and internal consistency. Results indicated high reliability for both instruments, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.86 for the SPISP and 0.81 for the SPIES.

Observational procedures

To supplement and contextualize survey findings, structured classroom observations were conducted using two researcher-developed tools: the Inclusive School Practices Checklist and the Instructional and Emotional Support Checklist. Both protocols were developed in alignment with international best practices for inclusive and emotionally supportive pedagogy (Schuelka et al., 2019; OECD, 2021). Observations took place across 10 classrooms in secondary schools and spanned five core subject areas: Norwegian, English, Mathematics, Science, and Social Studies. Each subject was observed twice to ensure variability and reduce observer bias.

Observation criteria included teacher-student interactions, evidence of differentiated instruction, classroom climate, and levels of student engagement. The observers—trained researchers with expertise in inclusive education—employed standardized rubrics and engaged in calibration exercises to maintain inter-rater reliability.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection occurred over a six-week period during the academic year. Survey data were entered into SPSS (Version 28) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to profile the demographic characteristics of the sample and to summarize students’ perceptions of inclusion and support. Inferential statistics, including independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVAs, were conducted to identify statistically significant differences across demographic groups. Multiple regression analyses further explored the predictive relationships between instructional/emotional support and students’ perceived inclusion, controlling for relevant background variables.

For Research Question 1, descriptive statistics were used to provide an overarching view of students’ experiences across school types and demographic categories. To address Research Question 2, t-tests and ANOVA were applied to examine differences in the overall scores of the SPISP and SPIES instruments based on school level, gender, and age. Each observed teacher was also scored on key variables associated with inclusive and emotionally supportive practices, allowing for triangulated analysis of observed and reported data.

Qualitative observational data were analyzed using thematic analysis with an inductive coding approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Observed patterns in teacher behavior, classroom engagement, and student-teacher relationships were coded and categorized. Emergent themes were then cross-referenced with survey data to deepen interpretation and ensure consistency across data sources.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with established ethical principles governing research with human participants, including respect for autonomy, voluntary participation, informed consent, and the safeguarding of confidentiality. As the study involved non-sensitive topics and exclusively anonymized data, formal approval from a research ethics committee was not mandated under Norwegian regulations. Nonetheless, institutional permissions were obtained from all participating educational institutions. Participants were provided with comprehensive information sheets detailing the study’s aims, procedures, and their right to withdraw without consequence. No identifiable data were collected; responses were anonymized upon entry. All participants, including those aged 16, gave informed, autonomous consent.

Results

Instructional and emotional support in inclusive education

Observational data closely aligned with students’ questionnaire responses, affirming a consistent perception of instructional and emotional support in inclusive classroom settings. Minority students reported generally positive experiences, particularly in terms of engagement, curriculum adaptation, and emotional climate.

Instructional support in inclusive education

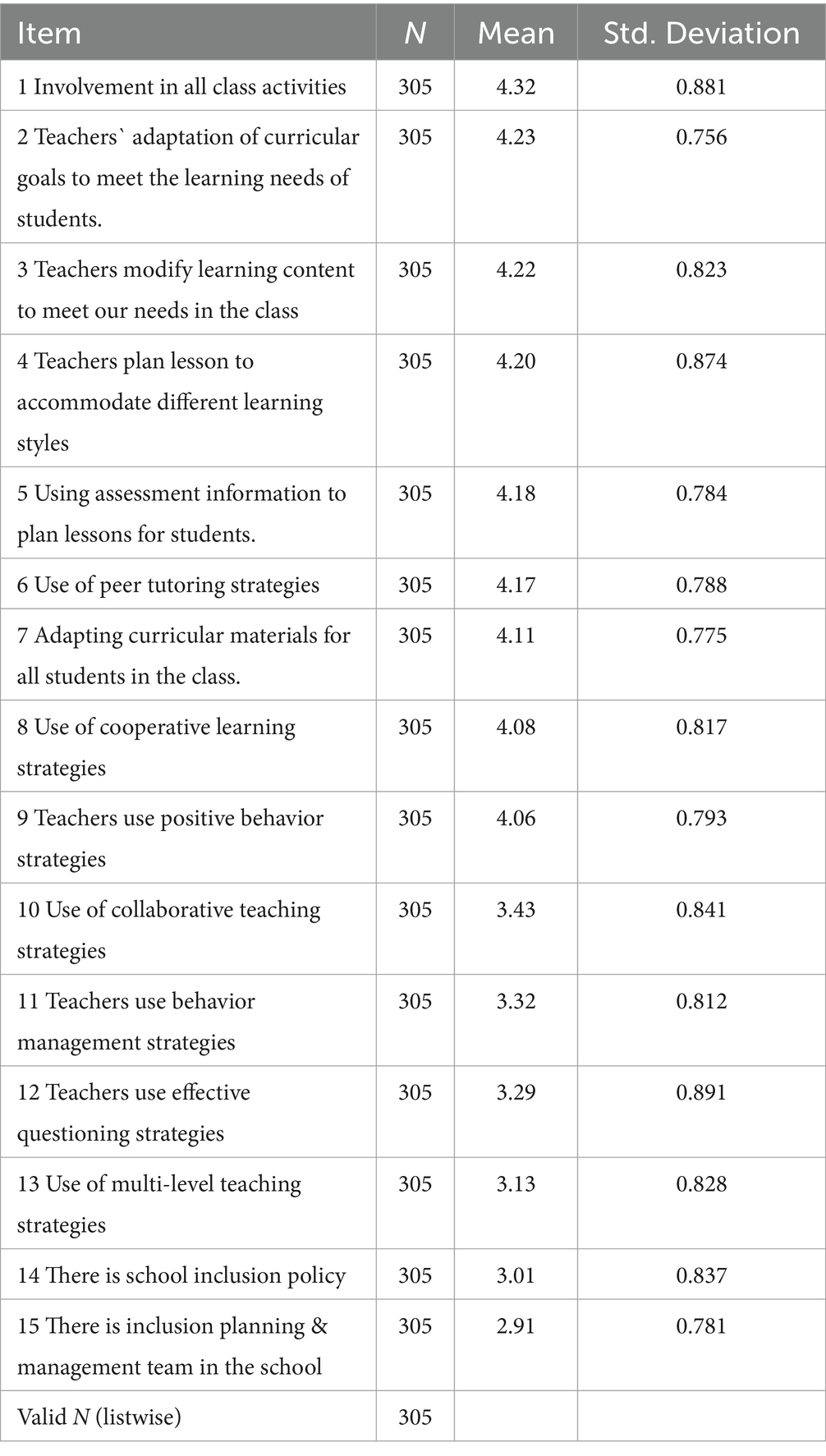

Descriptive statistics from the Student Perceptions of Inclusive School Practices (SPISP) instrument (Table 1) indicated high mean scores in areas reflecting differentiated instruction and classroom inclusion. The highest-rated practices were: Involvement in all class activities (M = 4.32, SD = 0.88), Adaptation of curricular goals to meet diverse learning needs (M = 4.23, SD = 0.76), Modification of learning content (M = 4.22, SD = 0.82), Planning lessons to accommodate different learning styles (M = 4.20, SD = 0.87) and use of peer tutoring strategies (M = 4.17, SD = 0.79). These responses suggest that students perceive teachers as actively working to create accessible and responsive learning environments. However, moderate ratings were observed for cooperative learning, collaborative teaching, and multi-level strategies, suggesting these inclusive instructional practices are applied inconsistently. The lowest rating was given to the presence of an Inclusion Planning and Management team (M = 2.91, SD = 0.78), indicating limited institutional infrastructure to support systematic inclusion.

Emotional support and classroom climate

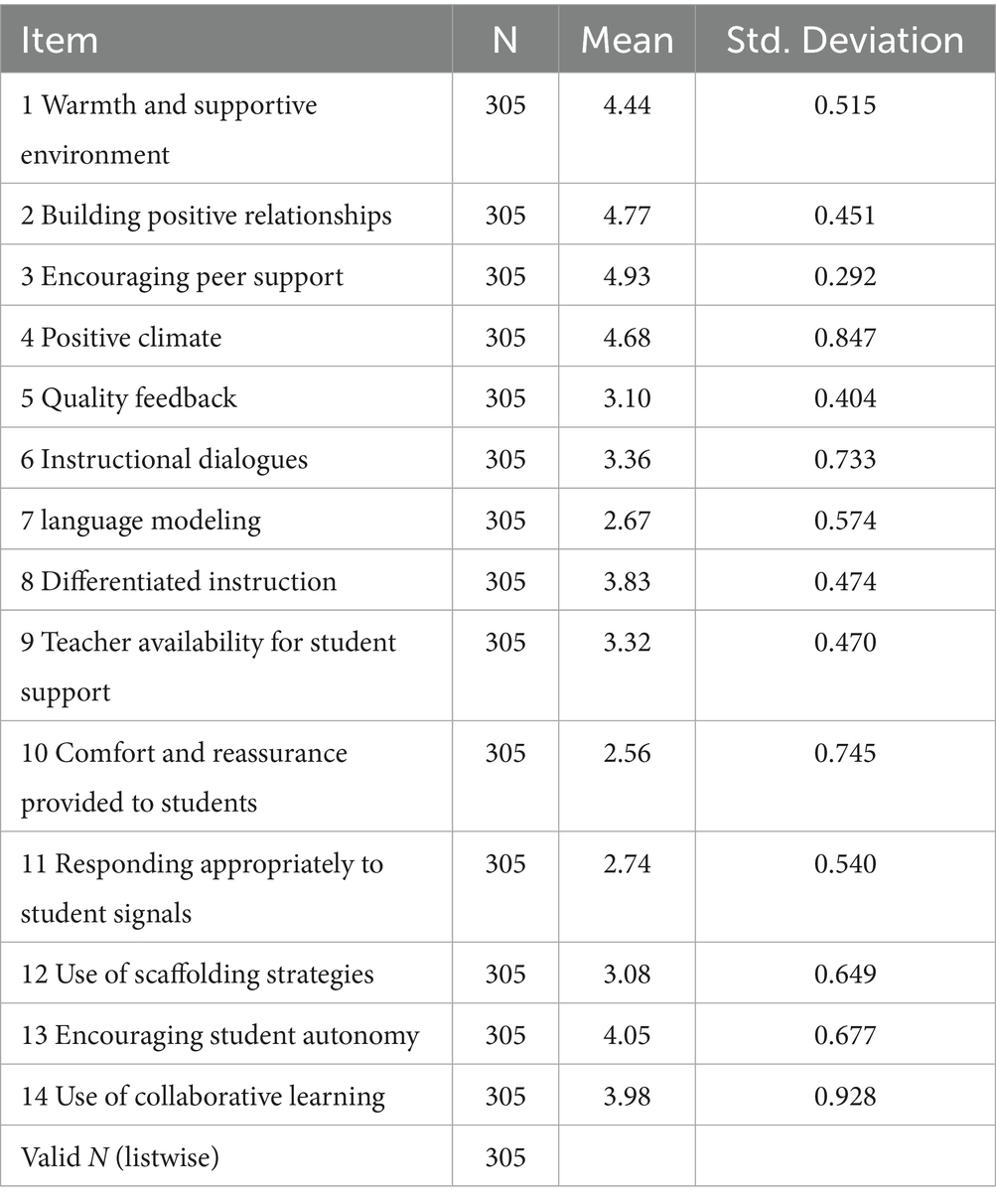

Responses from the Student Perceptions of Instructional and Emotional Support (SPIES) tool (Table 2) underscored the central role of emotional support in fostering inclusive learning environments. Students reported particularly high levels of agreement with statements related to encouraging peer support (M = 4.93, SD = 0.29), building positive teacher-student relationships (M = 4.77, SD = 0.45), establishing a positive classroom climate (M = 4.68, SD = 0.85), and providing a warm and supportive environment (M = 4.44, SD = 0.52). These quantitative findings were reinforced by classroom observations, which revealed that teachers frequently promoted collaboration, exhibited attentiveness to student needs, and cultivated respectful interactions. Such practices were consistently evident across observed classrooms and appeared foundational in shaping emotionally supportive and inclusive educational experiences for minority students.

However, while emotional climate indicators were strong, several instructional components that intersect with emotional support received only moderate ratings. Students indicated less frequent experiences with receiving quality feedback (M = 3.03, SD = 0.82), engaging in instructional dialogues (M = 3.36, SD = 0.73), perceiving teacher availability (M = 3.32, SD = 0.47), and benefiting from scaffolding strategies (M = 3.08, SD = 0.65). The lowest-rated item was related to language modeling (M = 2.67, SD = 0.57), revealing a critical gap in the instructional support of multilingual learners. Observational data corroborated these findings, showing that explicit scaffolding of academic language and individualized linguistic feedback were inconsistently implemented. This disconnect points to a broader issue in teacher preparedness, emphasizing the need for professional development in differentiated instruction and linguistically responsive pedagogy to ensure that instructional practices are aligned with the emotional and academic needs of diverse learners.

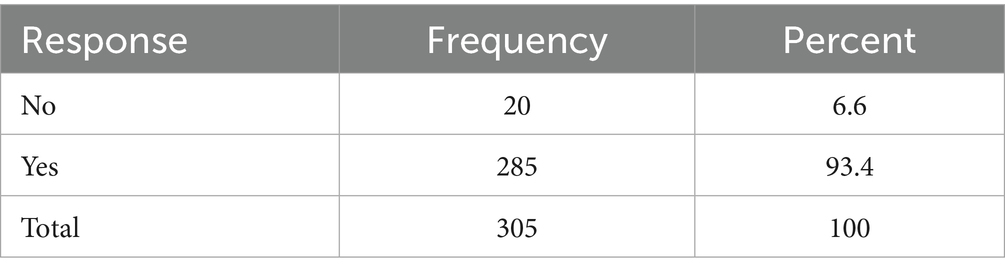

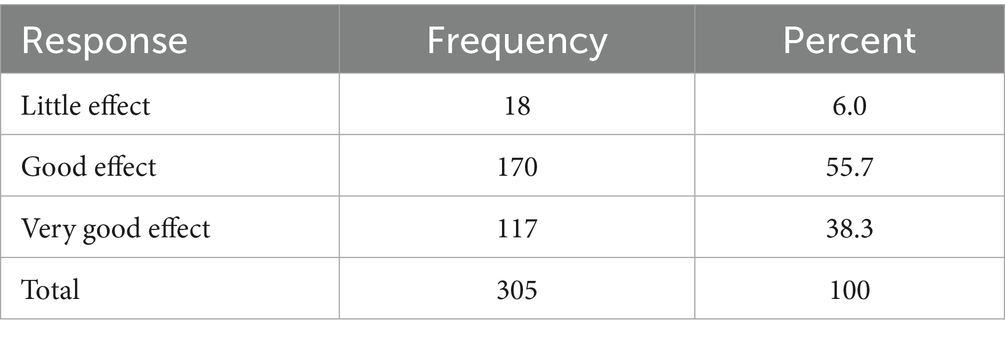

Student perceptions of impact

When directly asked about their experiences with instructional and emotional support, a substantial majority of students—93.4% (n = 285)—affirmed that they had received such support (see Table 3). This high level of reported support underscores the pervasiveness of these practices within the participating schools and universities. Furthermore, students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of this support were overwhelmingly positive. Over half of the respondents, 55.7% (n = 170), reported that the support had a good effect on their learning, while 38.3% (n = 117) described the effect as very good. Only a small minority, 6% (n = 18), indicated that the support had little effect (see Table 4).

These findings suggest that not only is instructional and emotional support widely implemented, but it is also perceived by students as having a meaningful and beneficial impact on their educational experiences. The predominance of positive evaluations reinforces the critical role such support plays in promoting student engagement, academic confidence, and well-being. Importantly, these results also align with existing literature emphasizing that students’ perceptions of teacher support are closely linked to improved academic motivation and inclusive learning outcomes (Roorda et al., 2011; Wang and Eccles, 2012). Consequently, sustaining and enhancing these support structures is vital to fostering equitable and inclusive educational environments, particularly for minority students navigating complex sociocultural contexts.

The overall scores for all participants on the three themes was also calculated regarding the effects of the three themes of inclusion, instructional and emotional support on their learning. The analysis showed that most of the participants 170 (55.7%) viewed the three themes to have good effect on their learning followed by those who found inclusion, instructional and emotional support to have very good effect on their learning n = 117 (38.3%) while the rest n = 18 (6.0%) rated as having little effect (see Table 4).

Instructional and emotional support and (SPISP) scale scores

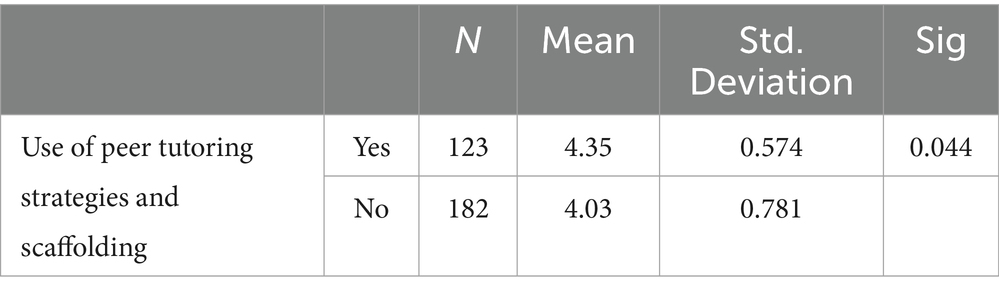

The analysis revealed that instructional support and inclusion had a significant influence on the Use of peer tutoring strategies/scaffolding (p = 0.04) (see Table 5). Peer tutoring fosters a sense of community and cooperation among students, which can help break down social barriers. All the other items on SPISP showed no significant differences with institutional support (see Table 5).

School type: ANOVA with scale items scores

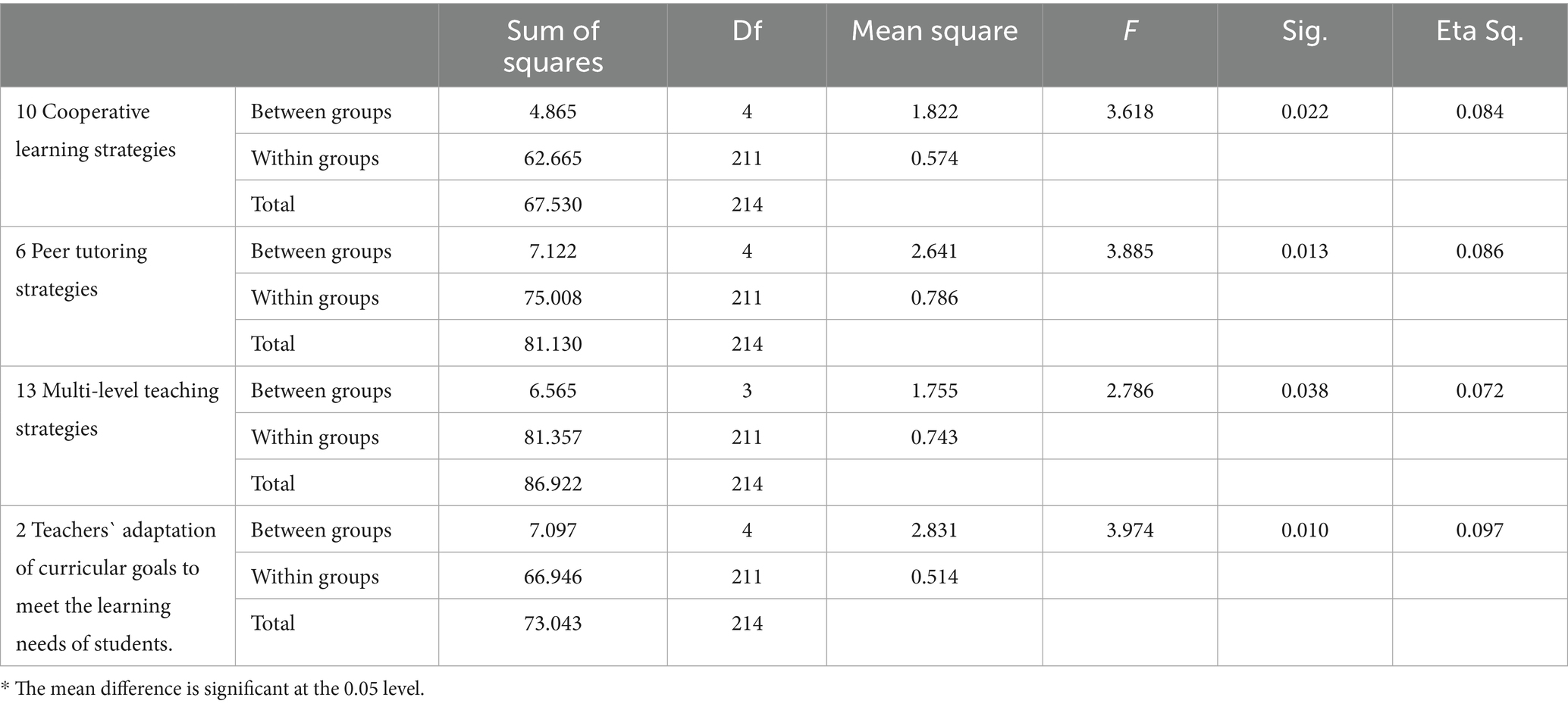

The One-way Between Groups ANOVA for individual items in relation to school types shows that there are significant differences regarding students in lower secondary, upper secondary and universities. Minority students with high emotional and instructional support from their teachers are those in lower secondary schools followed by upper secondary school students. Minority students in the universities score least on instructional and emotional support at the p = 0.05 level (see Table 5). These significant differences relate to the following items: Use of cooperative learning strategies (p = 0.02), Use of peer tutoring strategies (p = 0.01), Use of Multi-Level teaching strategies (p = 0.04), Teachers` Adaptation of curricular goals to meet the learning needs of students (p = 0.01) (see Table 6).

Emotional support and SPISP scale scores

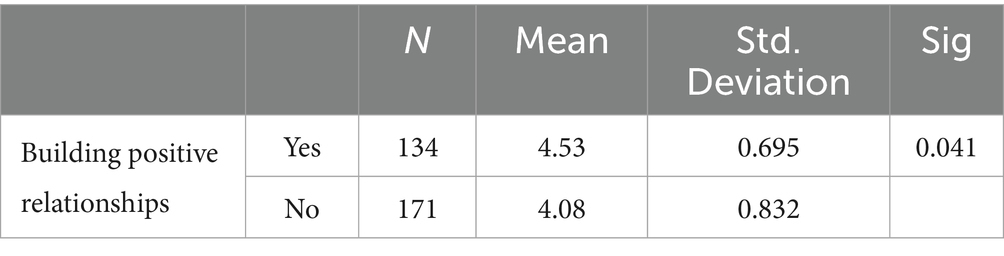

The analysis revealed that emotional support had a significant influence on secondary school students (p = 0.04). The effect size is small (0.048). Students in secondary schools considered emotional support useful in enhancing their learning (see Table 7).

Variables of age, gender and school type

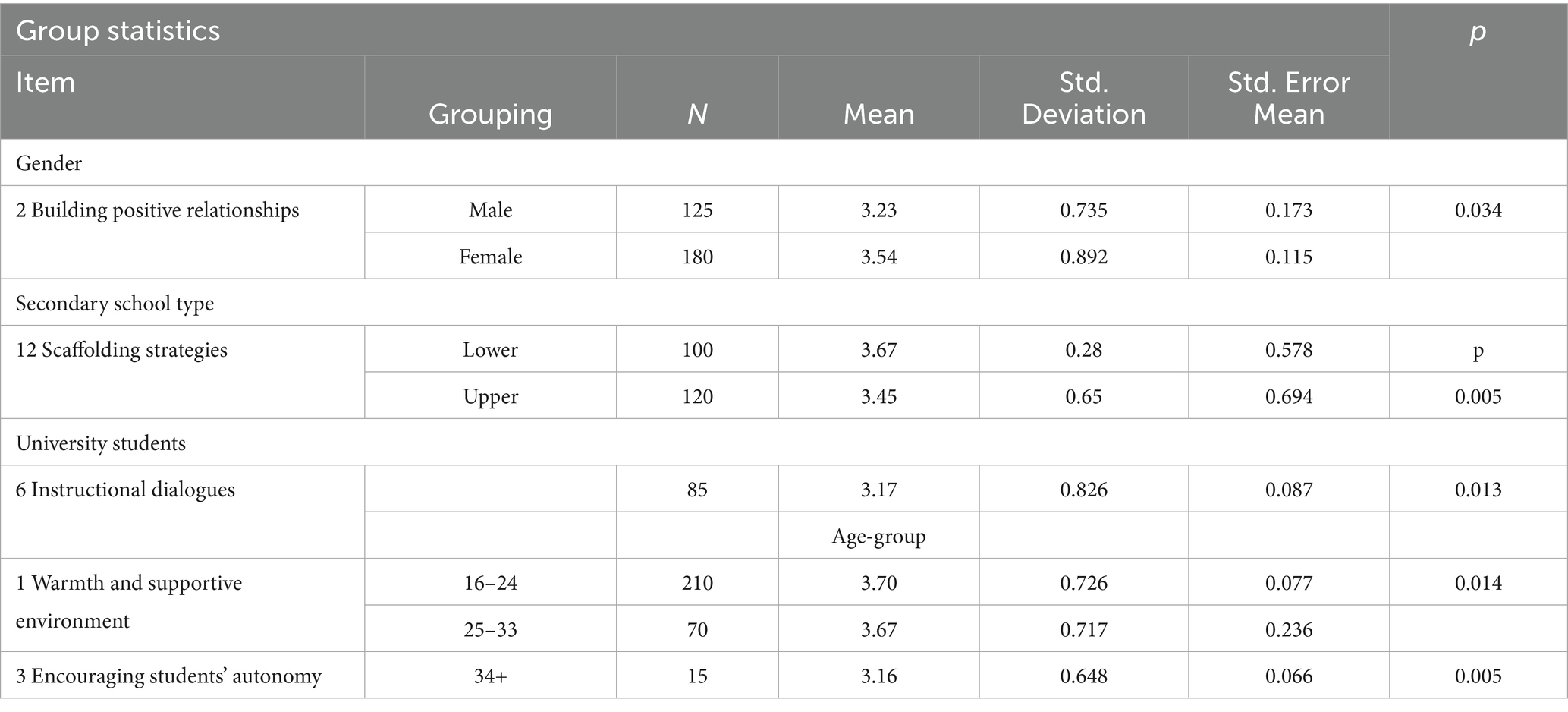

The t-tests conducted for background variables revealed that gender, age group and school type attended influenced students instructional and emotional support of their teachers about inclusion on some specific items.

Gender influenced instructional and emotional support for inclusion relating to Building positive relationships at p = 0.05 level. Female students were more supported than males. Again, lower secondary school students influenced institutional support about Scaffolding strategies while students at the university had the least scores on Encouraging students’ autonomy (see Tables 8, 9).

Relationship between teachers’ instructional and emotional support and inclusive school practices

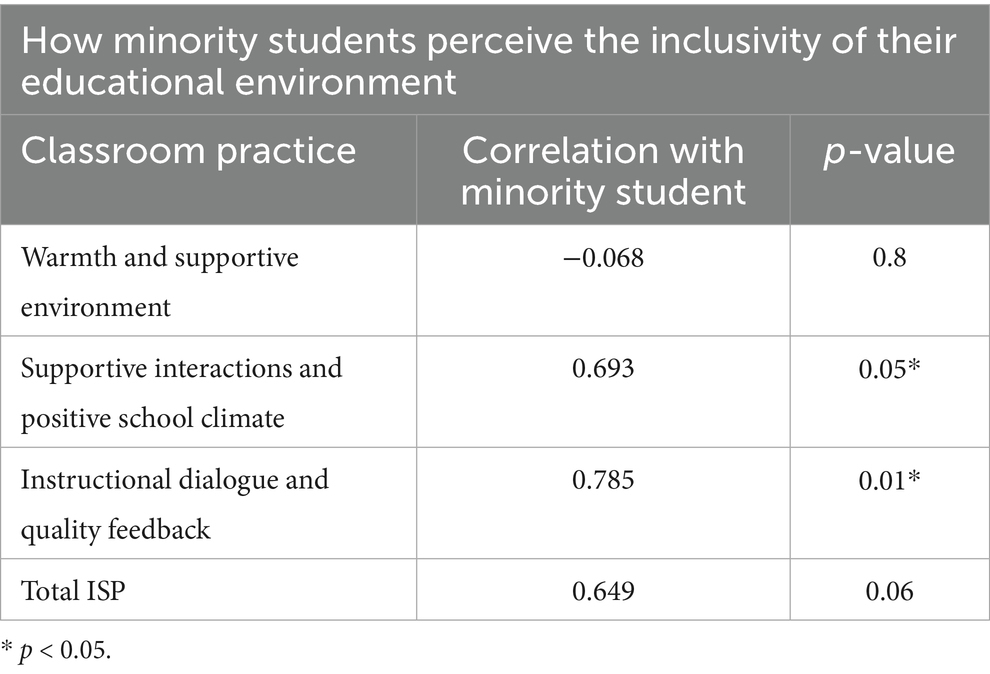

In terms of SPISP being predictive of instructional and emotional support of minority students, a correlation was carried out with SPIES (see Table 9). This multiple regression included warmth and supportive environment, Supportive interactions and positive school climate, Instructional dialogues and quality feedback. However, the background variables of gender, age and school type attended were omitted to give a clear picture of the regression equation.

The results showed that even though the total SPISP score was not significant (p = 0.07), supportive interaction/positive school climate and instructional dialogues were positively correlated (p = 0.04 and p = 0.01 respectively) with minority students` inclusion. This is a clear indication that instructional and emotional support of teachers have a significant role in enhancing minority students learning.

In summary, results indicated from high to low mean scores for inclusiveness, instructional, and emotional support items, showcasing positive student perceptions. Multiple regression analysis revealed significant correlations on certain inclusive school practices, confirming that teachers’ instructional and emotional support significantly enhance minority students’ learning. The data underscores the crucial role teachers play in fostering an inclusive and supportive educational environment.

Discussion

The quantitative data from 305 minority students reveal that a notable proportion (6.6%) perceive insufficient instructional and emotional support from teachers. While this percentage may appear modest, it underscores a critical concern for equity, particularly for those affected. Recent research emphasizes that minority students often encounter unique barriers in educational settings, necessitating culturally responsive teaching approaches (Gay, 2018; Howard, 2020a; Howard, 2020b).

Studies indicate that inadequate instructional support can stem from cultural misunderstandings or implicit biases, leading to lower academic performance and reduced engagement among minority students (Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007; Peguero and Bondy, 2011). Moreover, emotional support plays a pivotal role in fostering a sense of belonging and safety within the school environment, which is essential for academic success (Bottiani et al., 2017). The lack of such support may contribute to feelings of alienation and exclusion, adversely impacting students’ educational experiences.

The notably low score for language modeling (M = 2.67, SD = 0.57) in this study highlights a critical gap in inclusive teaching practices particularly in supporting multilingual learners. In multicultural classrooms, where students may speak a variety of home languages and possess varying degrees of proficiency in the language of instruction, effective language modeling is not optional but essential for equitable participation and learning. Research shows that without consistent and intentional language modeling, multilingual learners are likely to struggle with both content comprehension and classroom communication (Gibbons, 2015; Zwiers, 2014; García and Wei, 2014).

In inclusive settings, language modeling serves as a bridge between students’ existing linguistic repertoires and the demands of academic discourse (Schleppegrell, 2013). For instance, modeling how to construct scientific explanations, argue from evidence, or write reflective narratives provides learners with cognitive and linguistic scaffolds necessary for success.

The observational data in this study highlighted significant gaps in explicit language modeling within multicultural classrooms. Teachers rarely engaged in structured modeling of key academic language forms, and feedback tended to be general rather than linguistically targeted. Scaffolding strategies, such as sentence frames, visual supports, and syntax modeling, were inconsistently employed. These findings echo those of Eik et al. (2020), who identified a lack of teacher preparation in supporting linguistic diversity in multicultural schools, leading to missed opportunities for scaffolding language development. Similarly, García and Kleyn (2016) contend that failing to recognize students’ home languages as resources often hinders the development of additive bilingualism, reinforcing language deficits rather than fostering linguistic growth. This systemic shortfall underscores the urgent need for professional development that equips teachers with the tools and strategies to support language acquisition, including translanguaging (García and Wei, 2014), dynamic assessment, and the use of visual aids and sentence stems.

The study also found a significant positive correlation between teachers’ instructional and emotional support and inclusive school practices, as perceived by minority students. This suggests that higher levels of both instructional guidance and emotional encouragement contribute to more effective inclusive practices. Students who felt supported in both academic and emotional terms were more likely to report a sense of inclusion and support in their learning environments. These findings align with recent research highlighting the crucial role of teacher empathy and emotional competence in fostering inclusive education (Curran Mansouri et al., 2024; Howard, 2020a; Howard, 2020b). To address the observed gaps in language modeling, a shift toward linguistically responsive pedagogy is essential, ensuring that all students, not just native speakers, can fully engage with and succeed in academic settings.

Conclusion and implications

The findings of this study underscore the critical role that teachers’ instructional and emotional support play in fostering the academic achievement and overall well-being of minority students in multicultural learning environments. While educators serve as key agents in promoting inclusive practices, the challenges faced by minority students cannot be addressed through individual effort alone. Sustainable change requires a systemic and coordinated response that moves beyond the classroom. Enhancing teacher competencies in culturally responsive pedagogy and emotional intelligence is vital, yet such professional development must be embedded within broader institutional reforms that confront longstanding educational inequities.

Anchored in Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory and Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, the findings emphasize the dynamic interplay between micro-level classroom practices and macro-level social structures. For educators, this necessitates the implementation of Vygotskian scaffolding techniques that are responsive to students’ cultural identities, lived experiences, and linguistic diversity, while upholding rigorous academic expectations. Instructional approaches must be inclusive and asset-based, recognizing students’ backgrounds not as deficits but as resources for learning. Curriculum design, in particular, should reflect diverse cultural narratives and histories, fostering both critical thinking and identity development among students from marginalized communities.

The implications of these findings extend to institutional leadership and educational policymaking. Schools must transcend superficial diversity initiatives and instead adopt structurally transformative policies aimed at promoting systemic equity. A comprehensive strategy should begin with curriculum reform, ensuring that content across disciplines is inclusive, culturally sustaining, and capable of challenging dominant narratives that perpetuate marginalization. Equally important is the development of equitable assessment practices that move away from standardized, one-size-fits-all approaches. Assessments should be culturally relevant, holistic, and attuned to the diverse knowledge systems and strengths that students bring into the classroom.

Furthermore, building a diverse teaching workforce is essential. This entails implementing targeted recruitment, retention, and professional support strategies that increase the representation of educators from minoritized backgrounds, aligning the teaching population more closely with student demographics. Institutional equity must also be pursued through explicit anti-racist policies and the dismantling of structural biases in school systems. Integrating restorative justice frameworks into disciplinary practices can help reshape school culture in ways that affirm students’ dignity and promote social–emotional well-being.

Equitable resource allocation remains a cornerstone of inclusive education. Schools serving historically marginalized populations must receive the academic, emotional, and extracurricular support necessary to meet students’ needs. These include access to high-quality teaching, mental health services, enrichment programs, and safe learning environments. Adopting an ecological model of student support also involves cross-sector collaboration. Educational institutions should actively engage families, community organizations, and health providers to deliver wraparound services that are culturally responsive and developmentally appropriate. Such partnerships can enhance student resilience and strengthen ties between schools and the communities they serve.

To ensure these strategies yield lasting improvements, institutions must prioritize continuous evaluation and accountability. This involves systematically collecting and analyzing disaggregated data on students’ experiences with instructional and emotional support by race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other relevant indicators. These insights should be used to drive iterative improvements in policy and practice. Moreover, student, family, and educator voices must be central to these evaluative processes, ensuring that interventions are contextually grounded and equity-focused.

Ultimately, the findings call for a paradigm shift in educational policy and practice: from isolated, teacher-centered interventions to institution-wide strategies that recognize and address the complex, systemic factors shaping minority students’ learning experiences. This transformation requires not only pedagogical innovation but also structural commitment to justice, inclusion, and the holistic development of all learners.

Limitations and future research

While this study offers meaningful insights into minority students’ perceptions of teacher support, its reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias. Nonetheless, the consistency observed between students’ reported experiences and classroom observations supports the validity of the findings. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to assess the sustained impact of culturally responsive pedagogies and institutional reforms on the academic trajectories and well-being of minority students. Additionally, further investigation into intersectional variables such as migration history, linguistic diversity, and socioeconomic background can provide a more nuanced understanding of the factors shaping inclusive education. Such research will be crucial in advancing equitable and effective educational practices in increasingly multicultural societies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Permission from institutional heads. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because no children and vulnerable humans were involved and data and writing process was anonymous.

Author contributions

AA: Formal analysis, Resources, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. MC: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, KS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. BM: Methodology, Data curation, writing – review and editing, Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ainscow, M. (2007). From special education to effective schools for all: A review of progress so far. Educ. Rev. 59, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/00131910600748153

Alves, I., Campos, B. P., and Batista, J. (2020). Inclusive education and inclusive pedagogies: a critical analysis. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 353–367. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.20.20216424

Andersen, C. E., and Kulbrandstad, L. A. (2022). Multilingual learners and inclusive teaching in Norwegian schools: Practices and perceptions. Nordic J. Comp. Int. Educ. 6, 24–40. doi: 10.7577/njcie.4709

Andersen, F. C., and Thomsen, P. (2018). Educational policies and inclusive practices. J. Educ. Policy 33, 413–427. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2017.1351351

Arnesen, A.-L., Allan, J., and Simonsen, E. (2022). Equity and inclusive education in Nordic schools: Concepts, policies, and practices. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 66, 1–14. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v66.8242

Bakken, A. (2019). Educational transitions and challenges. Nordic J. Educ. 35, 135–150. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3576-1

Bakken, A., and Elstad, E. (2012). Pedagogical change and teacher efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 740–749. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.02.001

Bakken, A., and Hyggen, C. (2023). Minoritetsungdom i skolen: Hvem trives og hvem sliter? NOVA Rapport 2/2023. Oslo: OsloMet.

Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., and Mendelson, T. (2017). Inequality in school discipline and its effect on students. J. Sch. Psychol. 65, 87–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.08.004

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). “The bioecological model of human development” in Handbook of child psychology. ed. R. M. Lerner, vol. 1. 6th ed (New York: Wiley), 793–828.

CASEL (2020). The CASEL guide to schoolwide social and emotional learning : Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines, version 2.2. Retrieved from Wakefield, MA USA: CAST UDL Guidelines.

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA USA: Sage.

Curran Mansouri, M., Miller, A. L., Kurth, J. A., Ruhter, L., Wilt, C. L., and Morningstar, M. E. (2024). Teachers’ insights on cultivating inclusive education for students with complex support needs. Teach. Coll. Rec. 126, 118–145. doi: 10.1177/01614681241302637

Eik, L. T., Steinnes, G. S., and Ødegård, E. (2020). Fra intensjon til handling i barnehagen: Dilemmaer som omdreiningspunkt for kompetansebygging (1. utg.). Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., and Buchner, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Federici, R. A., and Skaalvik, E. M. (2014). Students’ perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: Relations with motivational and emotional responses. Int. Educ. Stud. 7, 21–36. doi: 10.5539/ies.v7n1p21

Florian, L., and Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. Br. Educ. Res. J. 37, 813–828. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

Florian, L., and Spratt, J. (2013). Enacting inclusion: A framework for interrogating inclusive practice. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 28, 119–135. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2013.778111

Friend, M., and Cook, L. (2016). Interactions: Collaboration skills for school professionals. Boston, MA, USA: Pearson.

García, O., and Kleifgen, J. A. (2018). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

García, O., and Kleyn, T. (Eds.) (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments. New York, NY: Routledge.

García, O., and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Palgrave Macmillan.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom. 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Heinemann.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. San Francisco, CA: Corwin Press.

Hamre, B. K., Hatfield, B. E., Pianta, R. C., and Jamil, F. M. (2013). Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher–child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Dev. 85, 1257–1274. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12184

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2006). Student-teacher relationships and learning. Educ. Res. Rev. 1, 61–77. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2006.03.002

Haug, P. (2017a). Inclusive education and its challenges in Scandinavia. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 32, 125–136. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2016.1254968

Haug, P. (2017b). Understanding inclusive education: Ideals and reality. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 19, 206–217. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2016.1224778

Haugen, G. M. D. (2017). The shifting role of special education in modern schooling. Spec. Educ. J. 25, 221–234. doi: 10.2737/FS‑RU‑125

Hilt, L. T. (2017). Education of newly arrived students in Norway: A critical examination of rights and opportunities. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 7, 172–180. doi: 10.1515/njmr-2017-0027

Hogekamp, A., Wilde, M., Bögeholz, S., and Urhahne, D. (2016). Gender-specific effects of out-of-school laboratory experiences on self-concept and motivation. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 38, 184–206. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2015.1123002

Howard, T. C. (2020a). Why race and culture matter in schools: Closing the achievement gap in America's classrooms. 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Teachers College Press.

Joshi, A., Eberly, J., and Konzal, J. (2015). Global perspectives on teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 66, 308–320. doi: 10.1177/0022487115594563

Joshi, M., Konold, T. R., Smith, J. L., and Cornell, D. (2015). Teacher perceptions of school climate as predictors of student risk. Sch. Psychol. Q. 30, 457–469. doi: 10.1037/spq0000109

Kjos, H., Nilsen, T., and Sølvberg, A. M. (2021). Exploring inclusive practices in Norwegian schools. Front. Educ. 6:707056.

Klepp, K., and Dobson, S. (2020). Student voices in multicultural classrooms in Norway. Intercult. Educ. 31, 558–573.

Kuyini, A. B., Desai, I., and Sharma, U. (2018). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, attitudes, and concerns about implementing inclusive education in Ghana. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 1509–1526. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1544298

Lødding, B. (2015). Educational practices and student engagement. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 59, 425–441. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2014.974586

Lødding, B., and Aamodt, P. O. (2015). Educational inclusion of minorities in Norway: An analysis of challenges and policy responses. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget NIFU.

Mudhar, G., Ertesvåg, S. K., and Pakarinen, E. (2024). Patterns of teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward inclusive education associated with teacher emotional support, collective teacher efficacy, and collegial collaboration. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 165–181. doi: 10.1080/08856257

Næss, K.-A. B., Hokstad, S., Furnes, B. R., Hesjedal, E., and Østvik, J. (2024). Inclusive education for students with special education needs in Norway. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Remedial and Special Education. Advance Online Publication.

Nasir, N. S., Lee, C. D., Pea, R. D., and McKinney de Royston, M. (2020). Handbook of the cultural foundations of learning. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Routledge.

Nortvedt, G. A., Riise, K., and Santos, L. R. (2022). Inclusive education in Norway: A scoping review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 623–641. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1699602

OECD. (2019). OECD future of education and skills 2030: OECD learning compass 2030. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ (Accessed January 20, 2025).

OECD. (2021). Empowering students through assessment: OECD learning compass 2030. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/education/empowering-students-through-assessment-efa190c2-en.htm (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Peguero, A. A., and Bondy, J. M. (2011). Immigration and students’ relationships with teachers. J. Educ. Sociol. 84, 95–114. doi: 10.1177/0038040710392716

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., and Stuhlman, M. W. (2008). “Relationships between teachers and children” in Blackwell handbook of early childhood development. eds. K. McCartney and D. Phillips (Baltimore, MD USA: Blackwell Publishing), 365–386.

Reyes, R., Da Silva Iddings, A. C., and Feller, N. (2021). Equity in teaching and teacher education. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

Rogoff, B. (2016). Developing understanding of the idea of communities of learners. Mind Cult. Act. 23, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/10749039.2016.1166944

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., and Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2013). The role of metalanguage in supporting academic language development. Lang. Learn. 63, 153–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00742.x

Schuelka, M. J., Johnstone, C. J., Thomas, G., and Artiles, A. J. (2019). The SAGE handbook of inclusion and diversity in education. New York, NY: SAGE Publications.

Sharma, U., and Loreman, T. (2020). Factors contributing to the implementation of inclusive education in Pacific Island countries. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 23, 65–78. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1514751

Sigstad, H. M. H., Myklebust, J. O., and Engebretsen, E. (2021). Teachers’ conceptualisations of inclusive education in Norway. Educ. Inq. 12, 251–269. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2020.1843267

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychol. Rep. 114, 68–77. doi: 10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2019). Teacher burnout and relationships with students: A literature review. Int. Educ. Stud. 12, 1–11. doi: 10.5539/ies.v12n6p1

Tenenbaum, H. R., and Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 253–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: responding to the needs of all learners. 2nd Edn. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tudge, J. R. H., Mokrova, I., Hatfield, B. E., and Karnik, R. B. (2016). Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 8, 427–445. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12165

Uli, N. H., and Kurniawati, F. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education in Indonesia. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 34, 157–168.

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. UNESCO. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (Accessed January 20, 2025).

van den Bos, W., Kool, W., and McClure, S. M. (2021). Understanding development through a computational lens. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 48:100939. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100939

Vedøy, G., and Møller, J. (2021). School leadership for equity and inclusion: Lessons from Norwegian schools. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 25, 272–286. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1708473

Vogt, F., Rogalla, M., and Pelz, P. (2019). Scaffolding—A model for teacher support of student learning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 503–522. doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0401-2

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Harvard University Press.

Wang, M. T., and Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement. Dev. Psychol. 38, 1541–1553. doi: 10.1037/a0027031

Keywords: inclusive education, minority students, instructional and emotional support, culturally responsive pedagogy, language modeling

Citation: Alhassan AM, Christensen MH, Solheim K and Mellemsether B (2025) Empowering minority voices: how inclusive teaching and support foster multicultural learning. Front. Educ. 10:1595106. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1595106

Edited by:

Israel Kibirige, University of Limpopo, South AfricaReviewed by:

Sanjeev Kumar Jha, National University of Educational Planning and Administration, IndiaSupianto Supianto, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Alhassan, Christensen, Solheim and Mellemsether. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Awal Mohammed Alhassan, YXdhbC5tLmFsaGFzc2FuQHVpcy5ubw==

†ORCID: Ksenia Solheim, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7745-0478

Awal Mohammed Alhassan

Awal Mohammed Alhassan Margrethe Hall Christensen2

Margrethe Hall Christensen2