- 1Didactics and School Organization, International University of La Rioja (UNIR), Logroño, Spain

- 2Didactics and School Organization, Calle Prof. Vicente Callao, University of Granada, Granada, Spain

- 3SLATE, Centre for the Science of Learning and Technology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Ensuring learning for all and by all in urban schools is a major challenge. It is therefore necessary to rethink schools and teacher performance to respond adequately to these challenges, especially in secondary education. In this respect, the extended professional learning communities model may be a viable alternative. This article presents data from the study of three secondary schools working to improve their educational outcomes. We adopt a case study methodology with an intrinsic, ethnographic, and autobiographical perspective to contextualize and understand the topic under study. The results reveal the degree of presence and development—at different levels of depth—of the dimensions that define an extended professional learning community. In these cases, they value the growth of their social and professional capital, with a sense of community, while weaving collaborative networks inside and outside the school around a shared purpose, i.e., liberating learning and ensuring learning for all. We conclude that the key conditions for achieving this goal are relational trust, professional interrelationship, co-responsibility, and clear shared leadership for learning, guided by the environment and underpinned by principles of care and social justice.

Introduction

Various reports, such as TALIS (2018) emphasize that, while the Spanish educational system (especially Andalusia) has seen substantial progress in recent decades, problems still persist in reaching the expected educational outcomes, equity, inclusion, and advances in the professional capital of schools, particularly at the Secondary Education level. In the Spanish context, the constructs ‘Professional Learning Community’ or ‘Community of Professional Practice’ are not usually used in professional practice. Therefore, they are absent from Spanish teachers’ discourse and routine practice, which is a significant limitation (Bolívar and Bolívar-Ruano, 2016).

There is an emergence need to reverse this situation by transforming schools and communities into safe and stimulating environments that encourage educational improvement and success for all and among all. Schools must be set up as privileged learning spaces for students and teachers. Furthermore, transforming school cultures, especially in secondary schools, into inclusive communities requires redesigning the workplace and changing roles and structures. Such a task calls for pedagogical leadership shared by other intermediate leadership, forming a more collaborative professional culture characterized by organizational modes where everyone feels increasingly included as protagonists (Hargreaves and O'Connor, 2018).

In complex or adverse contexts, this challenge becomes even more apparent. Schools must transform and add value to their environment, culture, and practice to respond to current challenges and improve their educational outcomes. It is a matter of looking for schools capable of initiating and sustaining systemic self-revision, improvement, and educational innovation processes. For such changes to occur, new forms of school governance are essential, and should include leaders that create projects, cultures, and community-driven environments committed to good learning for all.

It is thus important to analyze schools that advance as ‘communities’ to transform this reality in complex and vulnerable contexts. It is necessary to detect contextual, internal, and external factors that contribute toward achieving higher levels of collaboration and participation to build a sense of community and co-responsibility in educational processes, especially in a complex scenario such as secondary education. Combining these two premises, that is, ensuring good learning for all in this challenging scenario and at this educational stage, is a major task for schools, and for which an appropriate response is not always evident. Against this backdrop the present study seeks to provide situated knowledge (in Andalusia, in this case) on how schools moving towards extended professional learning communities can favor learning in challenging contexts.

In this study, we aim to understand how secondary improve educational outcomes in challenging contexts using an extended Professional Learning Community organizational and functional model to respond to their challenges.

Professional learning communities and learning enhancement in challenging contexts

Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) are widely understood through the definition provided by DuFour (2004), who describes a PLC as an organizational framework guided by critical questions focused on student learning outcomes: what do we want students to learn, how will we know when they have learned it, and how will we respond when they experience difficulty in learning?» (DuFour, 2004, p. 6) A recent comprehensive literature review on PLCs (see Nat et al., 2024) also underscores these fundamental aspects, emphasizing shared leadership, collaborative inquiry, and collective responsibility as central characteristics.

As a conceptual starting point, the prevalent literature (Bolam et al., 2005; DuFour and Eaker, 2008; Hargreaves and Fullan, 2020; Stoll and Louis, 2007; Stoll et al., 2006) exists on communities of professional practice or professional learning communities. This literature describes many organizational and structural conditions that support teachers’ professional learning in their workplace (e.g., times, spaces, proximity and interrelatedness, openness, support and leadership).

There is a broad consensus on the conditions that constitute a particular scenario called Professional Learning Community (PLC), which have been used to determine state of the art in Spain. These conditions are shared and supportive leadership; shared values and vision; collective learning and application; shared personal practice; and supportive conditions that include relationships and structures.

From an integrative perspective, Admiraal et al. (2021, p. 685), building on the contributions of Stoll and Kools (2017), propose a perspective articulated around seven core themes that refine and develop those described previously. They propose the following: developing and sharing a vision focused on learning for all students; creating and supporting continuous learning opportunities for all staff; promoting team learning and collaboration among staff; establishing a culture of inquiry, innovation, and exploration; integrating knowledge, learning collectively, and sharing systems; learning with and from the external environment; and developing leadership for learning. De Jong et al. (2021) pointed out that the concept could be extended to encompass five elements (professional development outside of school, school-based professional development, knowledge sharing, co-design, and inquiry-based working) and seven conditions (shared support, professional autonomy, leadership of the principal, leadership of middle management, human resource management, communication in school and collegial support).

Combining all of these, together with a systematic vision, enables practices and processes, the heart of which is the sense of ‘community’ (Kools and Stoll, 2016; Stoll and Kools, 2017) that optimizes learning and makes the PLC more sustainable and focused. This body of work suggests that, to enhance the learning of all students, schools must develop internal capacities for improvement and learning, work on building a professional community with a common purpose characterized by collaborative professional practices and collectively assume personal and institutional commitment to improve the learning of all and among all. It is important, therefore, to organize and energize schools to generate collective professional capacity within schools and with networks (Nat Gentry et al., 2025). The drivers of change must be collaboration, mutual support, and trust in staff, that is, what Hargreaves and O'Connor (2018) have called ‘collaborative professionalism’, which also requires the professional commitment of all and among all.

Society has become more complex, and it is necessary to rethink what types of education and learning should be promoted to ensure that it is competent, meaningful, and valuable for all. We are also becoming more aware of the learning losses and equity gaps in education, especially in challenging contexts that are at risk of exclusion. Therefore, the PLC model must be rethought from different and complementary avenues of reflection (Hargreaves and O'Connor, 2018; Stoll and Kools, 2017). Thus, a community of this type only makes sense if it has a profound impact on increasing the learning of all students (in terms of quality, depth, equity, and integrity). As Osmond-Johnson et al. (2020) point out, the question is to contextually identify ‘what conditions must exist for students to learn and for teachers to teach, and how will system leaders adapt to support these conditions?’

Next, the model goes beyond the learning of teachers and schools to advance along other more committed lines of interactive professionalism aimed at achieving the best learning for all and among all. The challenge is to create a new framework for reinventing the school (Darling-Hammond, 2021; UNESCO, 2021) and to contextually construct the meaning of such change (DeMatthews, 2015).

However, we should not ignore the fact that the true heart of a PLC is the sense of ‘community’ (Admiraal et al., 2021; Kools and Stoll, 2016; Stoll and Kools, 2017), and that it is energized by the professional capital it can mobilize around a shared purpose. As Hargreaves (2016) argues, social capital includes, among other activities, collaborative working; shared decision-making; collaborative teaching; collective responsibility for all students’ success across grades, schools, and classrooms; mutual trust and support; distributed leadership; knowledge groups; professional learning communities; professional networks and federations; and many kinds of collaborative inquiry.

All of this entails a school that shifts from merely serving as a professional space to one that is community-oriented with a true sense of shared purpose with meaning for all. Hence the importance of the ‘increase of social and professional capital’ (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2020) and the ‘added value’ of the processes of social and professional interrelation in the construction of knowledge and the educational response to the challenges that it must face.

This professional capital that includes the school, its socio-cultural context, and the community in complex and vulnerable contexts also implies collaboratively uniting capacities and actions around a common project of transformation and improvement of learning from a social justice perspective, in short, building and developing a school culture capable of involving the entire community to promote more and better opportunities for learning for all and among all.

Data collection

Objective

To understand how secondary schools improve educational outcomes in challenging contexts using an extended Professional Learning Community organizational and functional model to respond to their challenges.

Methodology

We employed an intrinsic case study methodology with (auto) biographical, ethnography and dialogic-participatory perspective as exemplified.

Sample

A total of 43 participants were involved in this study (10 in School 1, 20 in School 2, and 13 in School 3), including teachers, school leaders, counselors, and community members. Data saturation was achieved once additional interviews and observations ceased to yield new meaningful insights or thematic variations, occurring after 51 interviews and 24 months of participatory observation per school. This methodological rigor ensured the depth and reliability of the findings.

The selection of cases was made with the intention of gathering experiences worthy of study. As a criterion of homogeneity, we looked for cases with the following characteristics: (1) being secondary schools (with the particularity that this entails); (2) located in challenging contexts, with a low socioeconomic and cultural index (SCI) and at risk of social and educational exclusion; (3) building a shared community purpose; and (4) gradually improving their educational outcomes. In order to meet the criterion of diversity or uniqueness without limiting the scope of study, three different schools were chosen. The first (hereafter C1) is in a remote deprived rural area; the second (C2) is in a peri-urban area (with a vulnerable diverse population that includes ethnic minorities and a population of small scattered rural nuclei); and a third (C3) in a working-class neighborhood of a city with a great variety of cultures, ethnicities, and immigrants. Therefore, each of these experiences, in addition to responding to the basic typology of the study, presents its challenges and circumstances while advancing, (following its own path and pace) as Professional Learning Communities committed to improving learning for all and among all.

Data analysis

The participants’ voices are collected through cascades of reflexive deepening that integrate cycles of in-depth (auto) biographical interviews, dialogic argumentation processes, ethnographic development due to the researcher’s involvement in the school and its durability over time, in order to understand the school at very deep levels, and participant observation. Thematic analysis was used for the data analysis, supported by Nvivo software, involving contextualization and a recurrent reflective deepening and dialectical validation until the information was saturated.

The analytical framework was grounded in the widely accepted dimensions of Professional Learning Communities (e.g., Stoll and Kools, 2017; Admiraal et al., 2021), and served as a guiding structure to interpret the data. This framework informed both the initial coding scheme and the thematic analysis, allowing us to systematically relate emerging categories to established conceptual dimensions, while identifying new themes specific to the studied contexts.

Thematic analysis was used considering two basic principles. First, the information and themes were emergent and not induced without leading questions. A strategy of active listening was employed where participants were invited to tell their life stories based on their school experiences. Throughout the communicative research processes, informants were also asked to describe their stories in relation to milestones, leitmotifs, characters, and critical moments. Second, we systematically aimed to contextualize the stories, searching for ‘other’ informants or perspectives, until achieving information saturation and dialectical validation of the information by the informants themselves.

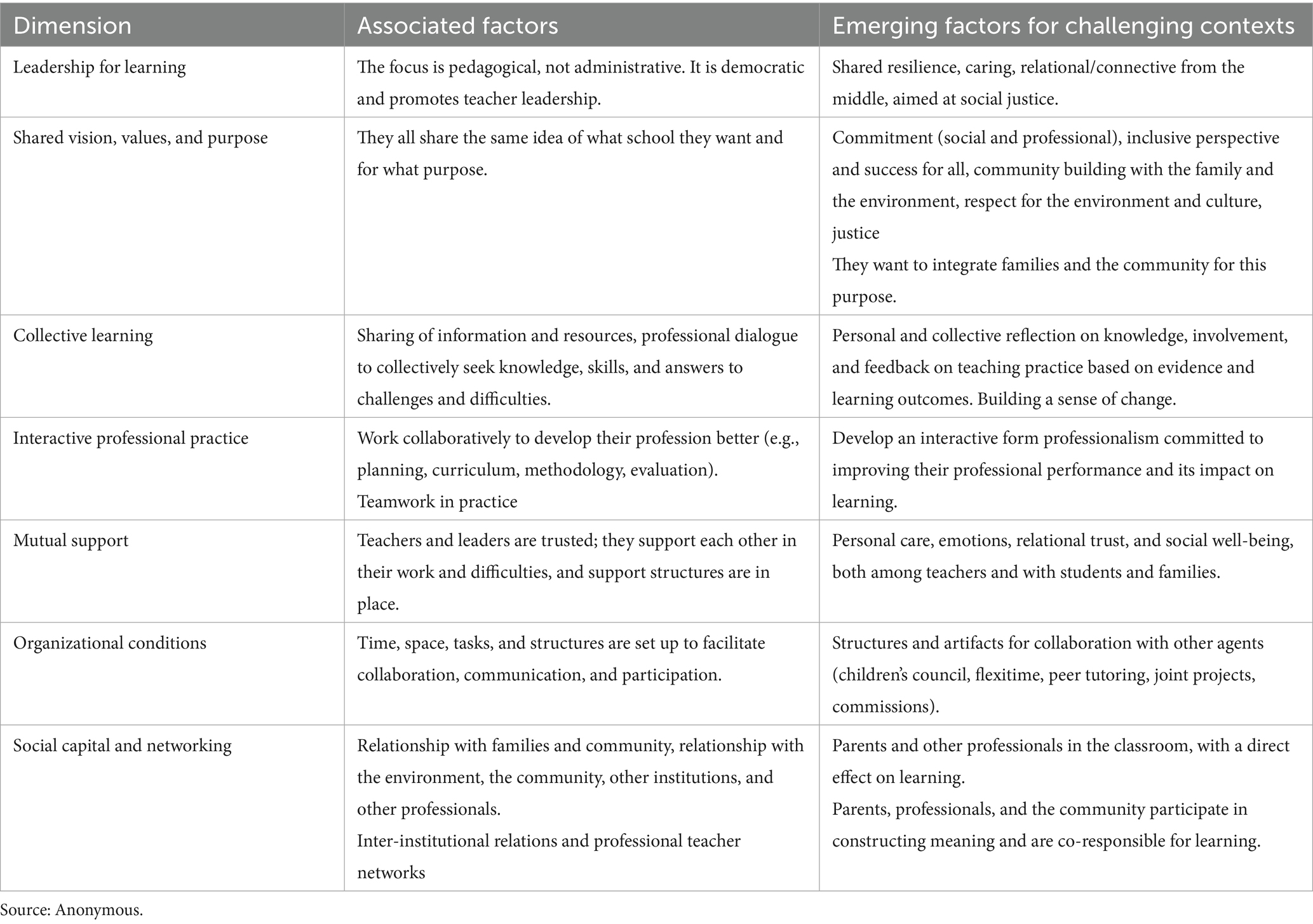

A grid described in the previous section was used to organize and contextualize the evidence obtained and discuss it in relation to current knowledge on the subject (see Table 1). This grid is organized around the commonly accepted basic dimensions and descriptors, along with other factors and dimensions that emerged from the study and which are loaded with the meanings expressed by the informants themselves.

Table 1. Dimensions of a PLC according to the literature and the emerging themes of the present study.

Triangulation of data was systematically ensured by cross-checking individual in-depth interviews, participant observations, and group discussions, consistently contrasting internal perspectives (teachers and school leaders) with external viewpoints (families, students, and community stakeholders). The emergent analytical framework explicitly aligns with and extends established conceptual categories from the literature on Professional Learning Communities (Stoll and Kools, 2017; Admiraal et al., 2021), emphasizing both consistencies and novel expansions driven specifically by the studied contexts.

Results

The results are clustered around the following seven major emerging themes: leadership for learning, shared vision, shared values and purpose, collective learning, interactive professional practice, mutual support, organizational conditions, and social capital and networking.

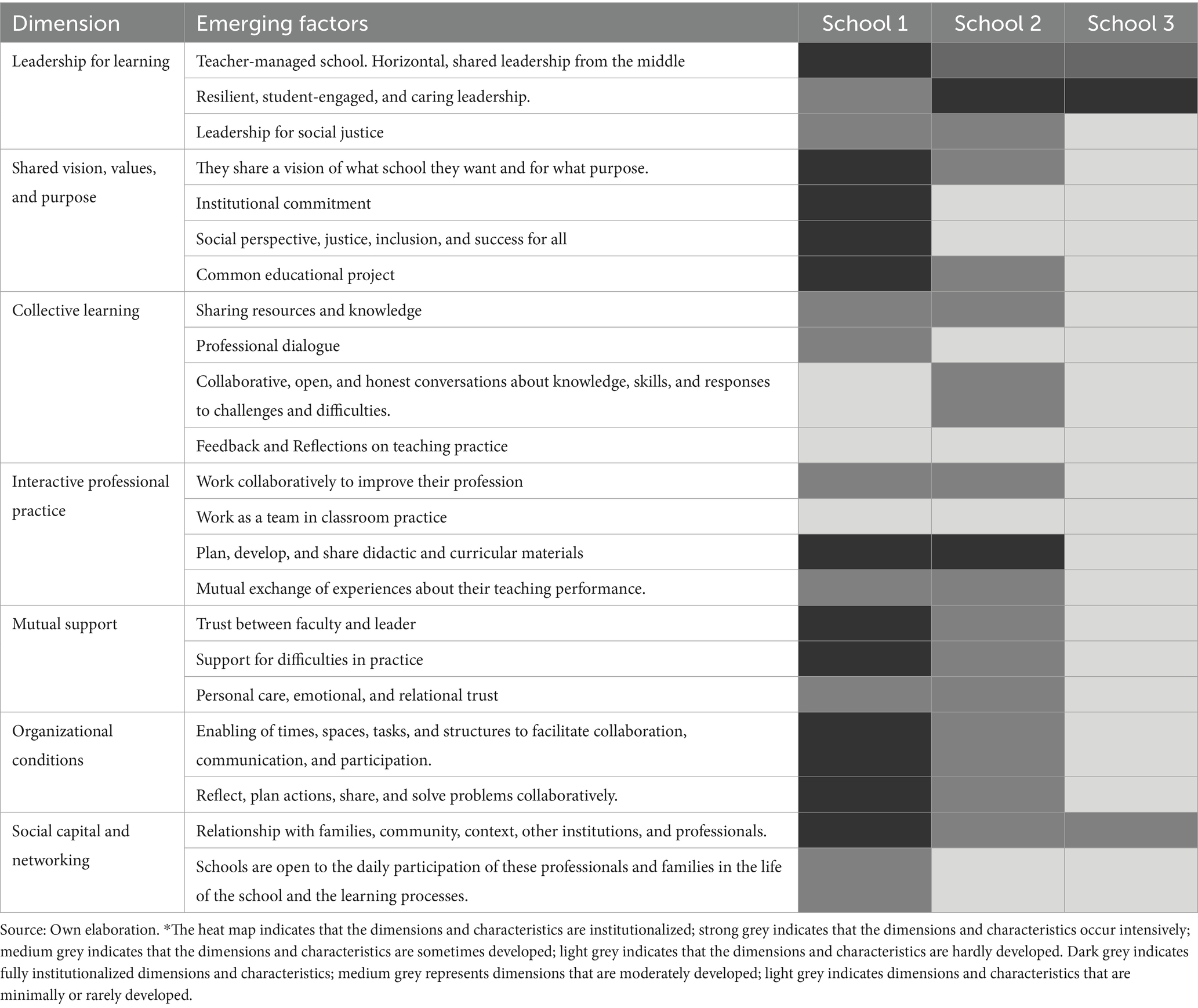

Table 2 shows the development of the various dimensions of a PLC in the three schools studied. Each school has its peculiarities, challenges, and possibilities, showing different stages of development in fulfilling the dimensions and factors that define a PLC committed to its students’ learning and integral development. Nevertheless, despite their challenges, all three cases are moving forward and collectively seek to face adversity and improve.

Table 2. Dimensions and factors of a PLC based on the literature and emerging themes of the present study.

The three cases under study show commonalities—albeit at different levels of achievement—in the different dimensions and factors. Overall, they show clear signs of resilience, actions for promoting social justice, and a commitment to professional development aimed at increasing teachers’ awareness of the type of educational school in which they are working. A joint educational project is driven by mutual support to achieve the objectives. Likewise, in all of the centers, there is a driving force that energizes the life of the school and shapes the development of the educational project. Care, trust, and the search for social capital prevail (mainly from their school management).

A gradation can be observed in the three cases regarding global differences. The first of them, cases (C1) present more solid and stable PLC features, which, unsurprisingly, are aligned with the model of Learning Communities endorsed by the educational administration. The second case (C2) participates to a lesser extent in this model; however, their purpose is to achieve this model, and to do so they have created an agile steering group consisting of the management team and several teachers, although their context is more complicated. Finally, the third case (C3), in which the challenges and difficulties are more acute, the processes are more costly and are in the initial stages since they have a newly formed management team.

A more detailed analysis according to dimensions highlights the following:

A. Leadership for learning

A clear and solid dimension of leadership for learning is evident, which directly impacts learning improvement. Moreover, this leadership is characterized by a high degree of resilience focused on the integral development of the students to the extent that care for the students’ and teachers’ emotional well being prevails. The various narratives show how the schools have strong management teams with well-defined pedagogical goals and objectives with the resilience needed to face challenges.

‘It has been a very positive evolution since we have had this principal. Through his leadership, many aspects of student development have improved; compensatory education, school coexistence, teacher commitment, new relationships with the school community’ (Teacher, C2).

‘For me, leadership must be pedagogical, especially in this context. We want the student to develop in an integral way and for that, we not only focus on the academic part, but also on the emotional part. If you are not emotionally well, you will find it difficult to perform in your studies’ (Principal, C1).

‘If anything defines the management team, it is resilience and the ability they have to respond and face challenges’ (Guidance Counselor, C3).

At a second level of reflection, it can be considered that Cases 1 and 2 present a style of leadership focused on learning, with leadership traits that are clearly horizontal, shared, and aimed at social justice. In both schools, tasks, responsibilities, and actions that require decisions and co-responsibility are delegated. Likewise, they comprehensively promote deep learning and improve their expectations and possibilities for educational and social success. The different narratives highlight aspects such as:

‘In this school with more than seven hundred and fifty students, seventy teachers, plus the external people who participate in the school, we either make a team and share leadership or you go crazy’ (Principal, C2).

‘Teachers make decisions for themselves, they lead their classrooms (…), our job is to energize, support and see that everything makes pedagogical sense and is in tune with our commitment to social justice’ (Head of Studies, C1).

Case 3 shows leadership for learning with great resilience and care for the students and the educational community. However, this cannot be fully considered shared leadership with a common purpose that promotes social justice. This aspect is due to two factors. On the one hand, the management team has only been in place for a short time, although it is recognized by the community, and has not yet achieved solidity in its actions or the engagement of teachers working toward a common goal. But on the other hand, the teaching team is not a team as such, since a group of teachers appear to resist change and are reluctant to adapt to the type of school in which they are working, that is, a school with a student body that presents great challenges and needs that are primarily related to emotional and coexistence issues. This profile implies that leadership should be driven by the need to show resilience, support, and emotional care.

‘Here there are teachers who are on leave due to burnout. Many are depressed because it is hell to support this student body’ (Teacher, C3).

A. Shared vision, values, and purpose

Regarding shared vision, values, and purposes, Case 1 responds entirely to this dimension. In this school, its educational agents share what kind of school they want and for what purpose. For this reason, they work as a Learning Community, this being a philosophy that underpins their daily tasks, requiring an institutional commitment from all their staff. In addition, they define themselves as an inclusive school that seeks success for all and promotes social justice. They present a joint educational project open to innovation and proposals from their teachers, including the students. One of the main objectives of this project is to achieve an inclusive school where students can develop integrally through a school culture open to be connected to the learning and development of students, as well as a school that caters for their needs and creates an identity where the students themselves feel visible. Social justice entails equality, respect, and acceptance of others, inside and outside the school. Despite the peculiarities of the school, it promotes a school culture that learns with the students and seeks their emotional well-being.

‘We didn't like the way the students were distributed, in a segregated way. So we decided to carry out a project based on inclusion and social justice. At the beginning, we didn't know how we were going to do it, but it was clear to us that we wanted to change that segregated culture. We were very afraid at the beginning, but we decided to take a risk’ (Principal, C3).

‘Working through the Learning Community implied a new way of seeing the classroom, of working, of evolving and improving’ (Teacher, C3).

While Cases 2 and 3 have teachers willing to exercise their role as a driving force for transformation, several hurdles must be overcome to develop a vision of shared values and purposes from a perspective of social and professional commitment. First, many teachers think their role is to teach their curricular subjects even though their students present other types of needs of a more primary nature. Some are even directly involved for professionally ‘questionable’ reasons.

‘I come here to teach my material, not to tell students how to behave and how to relate to others. That's what parents are for’ (Teacher, C3).

‘I am in this school because of its proximity to my home. If I had to bring my children here, I would not bring them. I teach my biology classes, but I don't see my students mixing with my children’ (Department head, C3).

‘How do you explain to a child who has not had breakfast in the morning, who went to bed at 5:00 a.m. and who comes unwashed and starving, the equations of first grade? Do you think the childcares about that learning? We have other needs that must be guaranteed’ (Teacher, C2).

‘Because of the type of students we have, there are teachers who take doing things with them for granted. They get frustrated when they see that they can't teach their material the way they want to and that they have to adapt the content to their level. They even go so far as to disengage. So, how are we going to improve’ (Head of Studies, C3).

A section of the teaching staff remains resistant to becoming aware of the type of educational school in which they are working. Instead, they persist with traditional didactic practices stuck in old routines, fears, and insecurities in the face of diversity and the magnitude of the challenges. This resistance also causes them frustration when they do not manage to teach their curricular subject, and students show demotivation and disinterest in learning. With this panorama, it becomes difficult to share what kind of school is desired and for what purpose, to have an institutional commitment on the part of its school agents, or to carry out actions distinguished by the quest for social justice or inclusion.

‘The improvements in this school are very long term. They are small, difficult to achieve and require a lot of patience. There are many teachers who are resistant to becoming aware of the type of school where they are, to sharing objectives, to participating in the educational project, which makes it more difficult to make progress’ (Principal, C3).

Case 2 presents a joint educational project. At the very least, all its staff are aware of the objectives and goals to be achieved, which facilitates the project’s implementation and generates a sense of security while helping to tackle the resistance shown by some members of the teaching staff.

‘We are committed to an inclusive school in all its varieties, formats, and ideas that we can come up with. I like to fight for the people and for the students. I think everyone has their limitations and exceptions, but we can all move towards the same goals and purposes’ (Principal, C2).

The challenge is to make progress regarding teachers’ ‘professional and social commitment’. In all three cases, there are many references to the importance of students having a voice and being the opportunity for real participation in the life and decision-making of their schools. They should feel that their school is a place where they can grow, learn, and evolve, that is, they should feel empowered within a common project full of meaning for all.

‘We have so much cultural diversity in the school that coexistence becomes very difficult. That is why our project is based on respect for diversity and coexistence. The school is full of images that help people get to know each other and feel part of it. With landscapes of the different nationalities present in the community, flags, different music is played every time we go out for recess, and we have cultural weeks focused on these different countries so that our students get to know those who coexist with them’ (Teacher, C3).

A. Collective learning

The schools are aware of difficulties faced in their teaching practice and join forces to combat these difficulties. They share resources and knowledge on how to make learning more attractive and easier for their students. They engage in professional dialogue and create spaces to discuss successful teaching tools and experiences that can be used in other courses and with other groups. They also reflect upon and discuss their teaching practice and its effectiveness in responding to the characteristics and needs of their students. Finally, teachers are open to feedback on their teaching and classroom practices, as they want to improve their teaching functions to achieve greater student learning success.

‘Our teachers are constantly asking us if what we learn is useful to us and what happens to us in and out of school. We like that, that they take our opinion into account’ (Student, C1).

The three cases seek to achieve — firstly from their teaching staff and from families and community — a shared purpose when it comes to tackling community problems. They provide help, activate communication channels to make them fluid and efficient, and face challenges, sharing points of view and experiences in an organized manner in their quest for appropriate and possible solutions. To do so, they use particular artifacts and themes that bring together meaning and intentions.

‘It is very common to have chats among colleagues to share experiences, problems or follow-ups of children or agreements. And this is more than institutionalized among the members of the management team and the steering group that supports the project’ (Guidance Counselor, C2).

A. Interactive professional practice

In the three cases, there are evident signs that progress is being made in teachers working collaboratively to achieve the proposed objectives and that students have a voice and space to participate in the development and operation of the school.

‘I feel good working at this school. The management is open and willing to support new projects. We work together, help each other with didactic materials and even share classroom experiences that have worked so that they can be used with other groups’. (Teacher, C2)

‘Thanks to the feedback on our teaching practice we improve. There is a very constructive working team that is willing to help each other when it comes to didactic, teaching, and learning aspects in order to help our students learn and move forward’. (Secretary, C3).

Interactive professional practice is more common and consolidated in Cases 1 and 2, while Case 3 presents more difficulties and discrepancies. In the former, teachers work collaboratively to improve their professional practice and foster their students’ interest in learning. To this end, they exchange experiences, doubts, and successes and discuss teaching strategies, educational outcomes, and the degree of adaptation to students’ needs. They even create new knowledge in accordance with their educational contexts, which includes knowing how to coexist, creating positive school climates, and resilient spaces to advance and grow in the face of adversity. Moreover, the evidence shows that there is dialogue among teachers in which they share pedagogical ideas and are constantly striving to find ways to be of service to the students.

‘We share didactic tools and classroom experiences that have been successful with one group and we carry them out with another. We reflect on why we teach this way or that way, what motivates our students to learn. Of course, we are inventing all day long’ (Teacher, C 1).

‘When I arrived new to this school I was lost. Everything was controversial and costly. So, I asked other colleagues for help, advice, tools, knowledge, I talked a lot with those who had more experience and that helped me a lot. Today, I can say that I like my class, my students, and my subject’ (Teacher, C2).

Case 2, with difficulty, and especially Case 3, do not show an interactive professional practice. The work in the classroom remains in the personal space with a distrust of others and a reluctance to observe what happens in their daily practice. This is no simple task; there is a perceived fear of change, of daring to do other things, other dynamics and learning situations, and of normalizing conflict and professional questioning.

A. Mutual support

The support provided by the management team and the steering group to the teaching staff is a dimension shared in all three cases. There is palpable evidence that they explicitly support everything that can lead to increased relational trust, bonding over tasks and responsibilities, while — albeit very cautiously — they are open to the potential of social capital. Therefore, leadership, in addition to resilience and caring, fosters institutional resilience and professionalism, providing time and continuity. Mutual support among teachers, on the other hand, is more common in Cases 1 and 2.

Given the conditions and challenges presented by the contexts where the three schools are located, the main focus of support is centered around personal, emotional, and social aspects instead of curricular, academic, and knowledge factors. They focus almost entirely on empathy and emotional competence.

The same is true for student support. Objectives are proposed that transcend learning, which include human development. Workshops on emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, and accepting diversity are supported for these purposes.

‘Working with these students is not about getting good results, it is about going beyond that, it is about connecting with them, empathizing with them, listening to them, knowing what they feel or what they need. Sometimes this is achieved and sometimes it is not. However, the management promotes these objectives in order to influence student development’ (Head of Studies, C2).

Feeling supported in difficult times strengthens internal security, generates bonds of trust, and gives the confidence to dare to grow. For this reason, in the cases studied, it is possible to observe how there is structural and relational support among teachers, the management team, students, and other agents collaborating with the school. Thanks to this, facing challenges is an easier and less cumbersome task.

These schools promote resilience as a resource to overcome adversity and create opportunities for success. Resilience is learned from the management team through teachers, coordinators, and students. In other words, this is collective community resilience. It is present transversally in the different improvement and transformation actions, such as learning to love oneself, taking care of oneself, having an orderly daily life, asking for help, or knowing how to trust.

‘In this school we support each other a lot. This is how you can survive here (…) when you have a problem in the classroom you can call another classmate to help you or someone from the management team, or even the janitors. I don't know, here being there for each other is essential, otherwise you sink’ (Teacher, C2).

‘In this school there is support, attentive listening, helping you, welcoming you when you need it most. There is always: I am here for whatever you need, how can I help you, don't worry, everything will be fine, let's go for it…’ (Teacher, C1).

However, Case 3 reveals another reality regarding this dimension. The experiences lived by the teachers with the former school management generated spaces of distrust and a lack of mutual support in such a way that it undermined the school culture and still persists today. Breaking with this tradition requires time, patience, and the formation of new relationships grounded in trust. In the face of this, the new management says it is fighting against this reality and striving to achieve an educational school with a culture and coexistence based on trust and mutual support. Evidence shows that a style of leadership is emerging based on supporting staff, students, and families, from an open and dialogical approach to rebuilding relationships and trust, which had been eroded by previous controversial experiences.

‘We have a complicated history that has left some quarrels. Sometimes there is a tense atmosphere and mistrust. This new management comes with other goals and attitude… Now things are not like that, on the contrary, but it is difficult to trust again, it takes time’ (Teacher, C3).

A. Organizational conditions

The cases studied — although at varying levels and with particular conditions — are concerned about the organizational conditions supporting their project and its implementation. These are both institutionalized and formal (but loaded with content and meaning), as well as more natural and informal. Their main role is to support the necessary dynamics of coordination and collaboration between teachers and the management team.

‘In the teaching team or department meetings, we make decisions, but the follow-up and support are more daily. It is very common to have chats among colleagues to share experiences, problems, or follow-ups of children or agreements. This is institutionalized among the members of the management team and the steering group that supports the project’ (Guidance Counselor, C2).

They also have structures, support, and programs to make the teaching-learning processes more operative and functional or to support them. They work to maintain an adequate school and institutional climate, developing different educational support programs. However, the three management teams and the guidance departments are especially vigilant so that these support structures do not serve as an excuse to take students out of class or to dualize the school.

A. Professional capital

All three cases know the importance of increasing social capital and networking with the community, other institutions, and professionals to improve students’ learning. Therefore, they define themselves as schools with open doors to the community and the context, albeit to varying degrees. While in the first case, it is a daily practice, for the other two, it is more an occasional occurrence or task reserved for the management team rather than a common practice among the teaching staff.

All three invite families to participate in their various actions and activities and build relationships with nearby associations and other professionals and institutions that can add value to their projects. The first case (C1) encourages family participation in work commissions, pedagogical gatherings, interactive groups with their children, international cooking workshops, and popular festivals. Positive responses to these calls are not always received in the other two cases, especially in the most vulnerable and complex cases. Many resist going to school and want to know more about what is being done there, and what is more, with their experiences of exclusion and accumulated failure, they do not believe that they can contribute value to their children’s education through participation. Nevertheless, all three cases continue to offer and encourage this engagement.

From another perspective, the collaboration and support of other institutions and professionals is something already ingrained, which in one way or another, occurs in each case with effective programs and actions. For example, Case 3 has the collaboration of an association of older adults in the same neighborhood; Case 1 has the help and collaboration of the town’s municipal library; and Case 2 works with the Gypsy Secretariat foundation or the social worker of the department of education.

‘The wrinkles project was beautiful. You had to see how the students interacted with the older people, they hugged them, they laughed together… they both had the opportunity to come into contact with each other, to live that experience. It was very rewarding for everyone’ (Principal, C3).

‘We have even had a group of fifty parents. All of them participating with their respective books. That was a miracle’ (Principal, C1).

‘The Gypsy Secretariat Foundation is a bridge of connection and communication between the school and the families. Many times we are not successful, it is very difficult to deal with the Gypsy people and I tell you that I am a Gypsy’ (Agent, Gypsy Secretariat, C2).

Discussion of results and conclusions

With this work, we looked closely at the cases of three secondary schools progressing toward improving their educational outcomes in challenging circumstances. Our objective was to determine to what extent these educational institutions adopt an organizational and functional PLC model and if they show certain features or particularities to respond to their challenges.

The findings (Table 2) reveal that the three cases show traits and evidence to suggests that they are moving forward in the basic dimensions that define the PLC model (Bolívar and Bolívar-Ruano, 2016, Stoll and Louis, 2007; Stoll et al., 2006), even expanding its meaning and purpose (De Jong et al., 2021; Hargreaves and O'Connor, 2018; Stoll and Kools, 2017), to address the special challenges posed by Secondary Education (Admiraal et al., 2021). Currently, these schools are not PLCs per se. Rather, they are at different levels of development or advancement, which indicates that in difficult contexts — where pressure, controversy, and the degree of professional involvement increase, and everything is magnified or accelerated — it will also be necessary to pay attention to two particularly relevant variables.

In this regard, our findings reveal that both the contexts and the processes of development and sustainability of these experiences must be considered (Bolam et al., 2005; DeMatthews, 2015; Keuning et al., 2016). This can be decisive in observing their complexities, challenges, and real possibilities for progress along with the areas that provide relevant meaning at that time and context.

Our results have also revealed a set of nuances, extensions, and approaches necessary to ensure learning for all and among all from a perspective of quality and equity. Without these elements, the PLCs would be merely formal and directed towards the technical learning of teachers without affecting their involvement and commitment.

There are constant references to advancing, building, and strengthening the community and its teaching staff’s degree of involvement/cohesion to respond to a challenging context that requires social and educational justice. Thus, the data are always nuanced in this sense. Our participants discuss proximity among colleagues, common spaces, availability, and collegial support for learning processes and resources. However, these are always nuanced, with an emphasis on emotional support in constructing meaning and conditions that impact improvements for their students and in making them feel good and involved in their learning.

Therefore, the case studies have revealed nuances in each dimension, and a new dimension has emerged with full meaning:

• The leadership of these PLCs must be fully pedagogical and social justice-oriented (DeMatthews, 2015), but it must also be distributed from the middle and care and resilience-driven.

• The shared purpose must align with the guidelines of UNESCO’s (2021), created from expansive teaching teams and new school governance. And this community project must emphasize both the liberation of learning that is of quality for all (Rincón, 2019), as well as the emergence of two basic premises: co-responsibility and professional commitment.

• Collective learning goes beyond knowledge, relationships, and mastery of resources and successful strategies. It directly impacts professional reflection (individual and collective) and the consideration of teaching practices that show evidence of improving educational outcomes.

• Professional practice aims to go beyond doing things together or collectively agreeing on decisions to become increasingly interactive, interrelated, and co-responsible, which is consistent with current knowledge in this regard (Hargreaves and O'Connor, 2017, 2018, Sleegers et al., 2018). This point is recurrent in the accounts of the leaders interviewed.

• The dimension of mutual support is very important, given the complexity of the cases and the challenges involved in ensuring a good education for all in these circumstances. However, it can be broadened to encompass different aspects, including resilience, community, and emotional competence, emphasizing a dual perspective, that is, caring for the teaching staff, teachers, and participation (including families), but also the well-being of students.

• They seek to create programs and organizational conditions by redesigning spaces and tasks in which everyone feels included and supported as a protagonist.

Finally, the idea of expanding the community to new scenarios, audiences, and agents makes total sense (Dempster, 2019). In these cases, beyond the nuances provided in the different dimensions, they constantly emphasize the need and value of increasing their social and professional capital and creating collaborative networks with other professionals and institutions. This is consistent with the readjustment proposal put forward by Hargreaves (2016), in which it is precisely the increase of professional capital with a sense of community that is the soul and main asset of a PLC. An open derivative after this reflection is the importance of the steering group, shared leadership, and the environment necessary for these contexts so that everything develops and advances in harmony, is aligned with social justice, and promotes the development of newly committed professionalism. And in this regard, our findings have also been conclusive.

A limitation of the present study is the absence of formal academic performance metrics (e.g., grades, standardized test scores, graduation rates) to empirically quantify educational improvements reported qualitatively by educators and school leaders. Future research should incorporate these formal indicators to validate and complement qualitative findings on perceived school improvement. While this study is primarily qualitative in nature, relying on triangulated data from diverse stakeholders, it offers valuable insights into perceived improvement, relational dynamics, and organizational change. The absence of standardized academic metrics limits empirical generalizability, but the depth of contextualized understanding contributes meaningfully to the field. Future studies should consider mixed-methods designs to combine the richness of qualitative analysis with quantitative validation.

This study identifies several avenues for future research on PLCs in challenging educational contexts. First, further empirical studies integrating quantitative indicators such as standardized tests or student performance data would strengthen the validity and generalizability of qualitative findings. Second, longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into the sustainability and long-term impacts of PLC frameworks. Additionally, future research could explore comparative international contexts to further validate and refine the extended PLC model presented in this study, particularly examining cross-cultural applications and adaptations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and its supplementary materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals and/or the minors’ legal guardians for the publication of any potentially identifiable data included in this article.

Author contributions

MO-E: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper was supported by the R + D + i Projects “Comunidades de práctica profesional y mejora de los aprendizajes: liderazgos intermedios, redes e interrelaciones. Escuelas en contextos complejos” [Communities of professional practice and learning improvement. Middle leadership, networks and interrelations. Schools in complex contexts] (Reference: PID2020-117020GB-I00) Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spanish Government within the State Programme for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., De Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., and Sligte, H. (2021). Schools as professional learning communities: what can schools do to support the professional development of their teachers? Prof. Dev. Educ. 47, 684–698. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1665573

Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Stoll, L., Thomas, S., Wallace, M., Greenwood, A., et al. (2005). Creating and sustaining effective professional learning communities. DfES Research Report RR637.

Bolívar, A., and Bolívar-Ruano, R. (2016). Individualism and professional community in schools in Spain: limitations and possibilities. Educar em Revista 62, 181–198. doi: 10.15366/reice2012.10.1.009

Darling-Hammond, L. (2021). “Organizing for success. From inequality to quality” in Transforming multicultural education policy and practice: Expanding educational opportunity. ed. J. A. Banks (Cambridge, MA: College Press), 326–276.

De Jong, L., Wilderjans, T., Meirink, J., Schenke, W., Sligte, H., and Admiraal, W. (2021). Teachers' perceptions of their schools are changing toward professional learning communities. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 6, 336–353. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-07-2020-0051

DeMatthews, D. (2015). Making sense of social justice leadership: a case study of a principal's experiences to create a more inclusive school. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 14, 139–166. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2014.997939

Dempster, N. (2019). “Leadership for learning: embracing purpose, people, pedagogy and place” in Instructional leadership and leadership for learning in school. ed. T. Townsend (Springer Nature), 403–421.

Dufour, R., and Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2016). The place for professional capital and community. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 1:10. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-11-2015-0010

Hargreaves, A., and Fullan, M. (2020). Professional capital after the pandemic: revisiting and revising classic understandings of teachers' work. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 3, 327–336. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0039

Hargreaves, A., and O'Connor, M. T. (2017). Cultures of professional collaboration: their origins and opponents. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 2, 74–85. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-02-2017-0004

Hargreaves, A., and O'Connor, M. T. (2018). Collaborative professionalism: when teaching together means learning for all. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Keuning, T., Geel, M. V., Visscher, A., Fox, J. P., and Moolenarr, N. M. (2016). The transformation of schools' social networks during a databased decision-making reform. Teach. Coll. Rec. 118, 1–33. doi: 10.1177/016146811611800908

Kools, M., and Stoll, L. (2016). What makes a school a learning organization?. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Nat Gentry, A., Martin, J. P., and Douglas, K. A. (2025). Social capital assessments in higher education: A systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1498422. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1498422

Nat, A., Martin, J. P., and Douglas, K. A. (2024). Social capital assessments in higher education: a systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1456031. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1456031

Osmond-Johnson, P., Campbell, C., and Pollock, K. (2020). Moving forward in the Covid-19 era: Reflections for Canadian education Publicación canadiense. Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina / Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy.

Rincón, S. (2019). Liberating learning: Educational change as a social movement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sleegers, P., Moolenaar, N., and Daly, A. (2018). “The interactional nature of schools as social organizations: three theoretical perspectives” in Handbook of school organization. eds. M. Connolly, D. H. E. Spicer, C. James, and D. Sharon (Sage), 45–56.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., and Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: a review of the literature. J. Educ. Chang. 7, 221–258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Stoll, L., and Kools, M. (2017). The school as a learning organization: a review revisiting and extending a timely concept. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 2, 2–17. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-09-2016-0022

Stoll, L., and Louis, K. S. (2007). “Professional learning communities: elaborating new approaches” in Professional learning communities: Divergence, depth, and dilemmas. eds. L. Stoll and K. S. Louis (Maidenhead and NY: Open University Press), 1–13.

TALIS (2018). Estudio internacional de la enseñanza y el aprendizje. Informe español. Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa.

Keywords: professional learning communities, quality of education, secondary education, educational improvement, leadership

Citation: Olmo-Extremera M, Domingo Segovia J, Khalil M and De La Hoz Ruíz J (2025) Professional learning communities in secondary schools and improvement of learning in challenging contexts. Front. Educ. 10:1598133. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1598133

Edited by:

Gisela Cebrián, University of Rovira i Virgili, SpainReviewed by:

William L. Sterrett, Baylor University, United StatesAnnisa Lutfia, Jakarta State University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Olmo-Extremera, Domingo Segovia, Khalil and De La Hoz Ruíz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Javier De La Hoz Ruíz, amRlbGFob3pydWl6QHVnci5lcw==

†ORCID: Marta Olmo-Extremera, orcid.org/0000-0001-6282-4038

Jesús Domingo Segovia, orcid.org/0000-0002-8319-5127

Mohammad Khalil, orcid.org/0000-0002-6860-4404

Javier De La Hoz Ruíz, orcid.org/0000-0001-7670-5662

Marta Olmo-Extremera1†

Marta Olmo-Extremera1† Mohammad Khalil

Mohammad Khalil Javier De La Hoz Ruíz

Javier De La Hoz Ruíz