- 1Faculty of College of Education Science, Hubei Normal University, Huangshi, China

- 2Faculty of Education, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3School of Education, Social Work and Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States

- 4Faculty of Educational Graduate Studies, Department of Special Education, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

This study employed a qualitative thematic analysis approach to investigate Chinese-American parents’ perspectives on early literacy development (ELD) in infants/toddlers and their home literacy environments (HLE), as well as how these environments influence emergent literacy skills. Data collection involved in-depth interviews with 12 Chinese parents residing in the United States. Findings reveal that HLE significantly shapes ELD, underscoring the critical importance of primary caregivers’ home-based engagement. The study highlights the significance of immigrant/bilingual family contexts for ELD, examining how diverse approaches to implementing bilingual or English-monolingual literacy practices within immigrant households yield differential effects. Crucially, variations in parental impact beliefs and sociolinguistic perspectives were found to shape distinct pathways of emergent literacy development in infants and toddlers. This study holds important implications for both practitioners and researchers in the field of literacy development and education. Also, it supports the use of a bilingual home environment, particularly for Chinese American families, as strategies to promote infants’ ELD.

1 Introduction

Literacy, as a fundamental mode of communication involving writing and reading (Owens, 2016), plays a critical role in shaping a child’s academic potential (Wang et al., 2020a). There is mounting evidence that underscores the significant impact of infants’ early literacy experiences on future reading skills (Duff et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2019; Lerkkanen, 2019; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2019; Van Tonder et al., 2019). A robust early literacy development (ELD) has been proven to significantly contribute to a child’s future overall development (Matvichuk, 2015; Zwass, 2018; Iverson, 2021).

Meanwhile, the significance of a child’s early years on their overall development is underscored by extensive studies (Liu et al., 2020), particularly highlighting the home literacy environment(HLE) as a crucial determinant affecting the “what, why and how” aspects of a child’s early literacy development (Carroll et al., 2019; De Houwer, 2021; Lamb et al., 2002; Owens, 2016; Piaget, 1962; Zwass, 2018). A substantial body of research indicates that the home environment plays a crucial role in children’s overall cognitive development (Baker, 2008; Harris and Goodall, 2007; Sylva et al., 2004), exerts a significant influence on preschoolers’ emergent literacy skills (Duff et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2019; Suggate et al., 2018), and is critically important for their subsequent overall literacy acquisition (Cole, 2011; Hunt et al., 2011; Melhuish et al., 2008).

Despite extensive research on its effects on reading accuracy, comprehension, and vocabulary, limited attention has been given to the influence of the HLE during infancy, with notable exceptions such as Sinclair et al. (2018) and Iverson (2021). Furthermore, there exists a research gap concerning bilingual homes, where young children navigate multiple languages for literacy development (Feng et al., 2014; De Houwer, 2021; Wright et al., 2022).

In addition to the relationship between HLE and children’s ELD, researchers began to consider the bilingual families. Studies explored young children from Chinese American families and found out that children from these families are still facing challenges, barriers, and issues academically, psychologically (King et al., 2021), culturally (Walker et al., 2020), and socioemotionally (Curtis et al., 2020). Many of researcher have demonstrated the importance of HLE in young children’s ELD, fewer studies have explored on its influence on infants and toddlers, especially within bilingual contexts. This study aims to bridge this gap by examining how the HLE influences the ELD of bilingual infants from Chinese American families, a minority group in the United States. By investigating the perspectives and experiences of these parents, the study seeks to shed light on this underexplored area.

1.1 ELD and HLE

Young children’s interactions with their living environment are instrumental in their learning process. They build connections, adapt, and grow through these experiences (Piaget, 1962; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Wright et al., 2022). At present, the significance of ELD has gained increasing recognition among researchers (Carroll et al., 2019; De Houwer, 2021; Ferjan Ramírez et al., 2020; Mascarenhas et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020a).

The quality of the HLE, as a proximal factor within the microsystem positively contributed to young children’s literacy development (Duff et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2019; Suggate et al., 2018) and were linked to children’s future achievements (Walker et al., 2020). To investigate the connections between the language input provided by parents and infants’ language achievement, Ferjan Ramírez et al. (2020) conducted a longitudinal study involving 71 infants. Results emphasized the crucial role of HLE in fostering language skills and encouraged parents to pay greater emphasis on the social aspects of their interactions with infants. Their findings demonstrated that infants can benefit significantly from a supportive HLE, which enhances their literacy skills. Chen-Hafteck (2021) conducted a comprehensive analysis of multiple components of the HLE and their effects on the development of emerging literacy skills in infants, further emphasizing the critical importance of a rich home literacy setting. Findings in this study underscoring its predictive value for children’s future linguistic capabilities. De Houwer (2020) delved into young children’s literacy development within bilingual environment, emphasized the importance of the HLE in fostering young children’s literacy interests. The result highly emphasized the importance of parents’ language usage and input. Overall, researchers have found empirical evidence supporting the assumption that the HLE is associated with the child’s ELD.

Notably, newborns exhibit a distinct preference for human speech—particularly their mother’s voice and native-language prosody—over other sounds (Baker, 2008). Echoing the principle that “extensive exposure is foundational to language mastery” (Hoff, 2015), lexical input constitutes a critical substrate for literacy development. Consequently, numerous scholars have focused on how caregivers’ vocabulary input within the HLE shapes infants’ and toddlers’ lexical output. In a landmark study, Hart and Risley (1995) tracked 42 families of varying socioeconomic status (SES) in Kansas City, recording home interactions from children aged 7–9 months over 2.5–3 years (yielding thousands of hours of dialog). Their findings revealed that by age 4, children from high-income families had been exposed to nearly 45 million words—a staggering 32-million-word gap compared to low-SES peers. This aligns with robust evidence indicating reduced linguistic stimulation for low-SES children (Hoff, 2003). Beyond quantity, research also highlights lexical quality. Weizman and Snow (2001) demonstrated that caregivers’ use of sophisticated vocabulary positively predicts children’s lexical acquisition, asserting that input quality outweighs mere quantity.

Nevertheless, Hoff (2015) and other scholars [e.g., Mason and Allen (1986) and Zellman and Watermann (1998)] contend that SES does not solely determine HLE’s impact. They emphasize two key factors. First, language acquisition requires interactive engagement (e.g., responsive dialog) rather than passive exposure (e.g., television). Second, relationship quality and affective dimensions of learning experiences mediate outcomes (Sylva et al., 2004). Additionally, researchers have noted that cultural factors like parental beliefs and educational backgrounds are also crucial in shaping infants’ literacy development (Wang et al., 2020a). It is evident that how the HLE influences ELD and what constitutes an effective HLE for promoting ELD require further ongoing investigation to achieve a broader consensus.

1.2 ELD and HLE in bilingual families

In addition to the significance of HLE in infants’ literacy development, some researches explored the relationship between HLE and ELD in a bilingual home environment (Curtis et al., 2020; Pemberton et al., 2006; Zhan, 2020). Tabors and Snow (2001) noted that the languages used at home, influenced literacy development, highlighting the importance of understanding the unique needs and challenges faced by bilingual families. They found out that young children acquire their first language from home as early as 6 months old and believed that the language what family members and community context used would have influence on ELD. It is noted that different people used different languages at home can have differential impacts on infants’ and toddlers’ literacy development.

For example, some studies had pointed out that some grandparents interact with their grandchildren in Mandarin in Chinese American families (Zhan, 2020) because most of these grandparents are non-English speaking (Pemberton et al., 2006). Pemberton et al. (2006) noted that these non-English speaking grandparents may influence their grandchildren culturally and linguistically. Within this bilingual HLE, the ELD for young children could be also shaped by their all caregivers at home. Thus, it is vital for educators being aware of all potential challenges and barriers of Chinese American families and understanding students’ particular needs culturally and linguistically (Zhan, 2020).

1.3 Empirical studies on the impact of HLE on ELD in bilingual families

The nurturing context of the family serves as fertile ground for cultivating bilingual abilities in children from immigrant families. De Houwer, a leading figure in bilingualism research, has meticulously explored the field of bilingual development through over three decades of sustained investigation. In her 2020 literature review addressing the question “Why do so many children exposed to two languages acquire only one?,” she systematically synthesized contributing factors including: Parental language input patterns; Quantity of language input; Parental discourse strategies; Children’s language attitudes; The role of institutional settings (e.g., daycare centers and kindergartens). In sum, approximately 25% of children (1–20 years) exposed to dual languages become monolingual in the societal language (e.g., school language), with non-societal languages at high risk of attrition. Monolingual strategies (e.g., Minimal Grasp) promote bilingualism but require sensitivity to children’s affective states. Monolingual policies in daycare/schools devalue non-societal languages, and 22–24% of educators advise families to abandon them, which has a negative impact on bilingual learning. This study drew upon this analytical framework to develop the interview protocol.

Scholars emphasize the critical importance of parent–child literacy activities in bilingual or multilingual immigrant families—specifically those where infants/toddlers have first-generation immigrant parents (excluding grandparent-immigrant households). Weldemariam (2025) employed a qualitative case study to deeply examine an Ethiopian-Norwegian immigrant family in Oslo, Norway. Centered on the home venue, the research focused on Daniel, the family’s second child (age 5), as the target participant. Within a sociocultural theoretical framework, Daniel as an incipient bilingual, his parents played an intentional and proactive role in enriching the HLE and embedded social practices. Daniel’s HLE was rich and culturally specific. For example, his father engaged in literacy activities with the children, the family regularly attended Ethiopian religious-cultural gatherings, and they celebrated traditional Ethiopian festivals. These practices significantly contributed to Daniel and his siblings’ trajectory toward balanced bilingualism.

Weldemariam also highlighted the influence of parental impact belief. In this case, the father and mother exhibited contrasting beliefs. The mother’s impact belief was comparatively low; she doubted her own efficacy in teaching literacy and her ability to influence Daniel’s development. This skepticism, in turn, resulted in limited investment of time and energy in home literacy practices. Meanwhile, she feared that learning the heritage language would compromise his acquisition of the majority language, thereby hindering his social acceptance and equal treatment. Her anxiety reduced motivation to support heritage language acquisition, leading to inconsistent provision of bilingual opportunities—unlike the father’s sustained efforts.

Impact belief in bilingual/multilingual development research refers to the conviction that the frequency of verbal engagement with children influences their language development. This necessitates parents to play an active role by providing attentive responsiveness and sufficient interaction to create adequate learning opportunities. Parents should embrace this belief, perceive themselves as proactive agents in fostering dual-language and biliteracy competencies from infancy onward, and align their daily practices accordingly (De Houwer, 1999, 2020). From an Early Childhood Education (ECE) perspective, this relates to parental self-efficacy (PSE) in caregiving. PSE refers to parents’ judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute the tasks related to parenting a child (Johnston and Mash, 1989). When parents exhibit high parenting self-efficacy, they should embody strong impact belief—confident that their actions effectively influence young children’s ELD. Such parents should actively engage in ELD by providing attentive responsiveness and sufficient interaction to create optimal learning opportunities, thereby cultivating a dynamic HLE.

Scholars also emphasize the influence of parental linguistic-cultural ideologies within immigrant bilingual HLEs on children’s bilingual development. These ideologies encompass parents’ perceptions of the heritage language versus the majority language of their current residence, reflecting deeper sociocultural valuations embedded in both linguistic systems. Tse (2001), in her study of successful bilinguals, linked language attitudes to ethno-linguistic vitality—defined as speakers’ perceived status and prestige of a language—identifying peer groups that value the heritage language as a critical enabling factor. This insight was corroborated by Li (2006) qualitative study of three upper-middle-class Chinese immigrant families in Canada, employing language socialization theory. All three families resided in a community with high ethno-linguistic vitality for Mandarin (where Chinese was highly valued), their children all attended English-only schools, yet exhibited divergent trajectories. Evidently, parents’ choices and beliefs concerning bilingualism, along with the practices they implement, profoundly shape their children’s ELD.

In summary, these studies offer invaluable methodological guidance for this research. Nevertheless, despite extensive evidence indicating the positive effect of a robust HLE on young children’s ELD, there is a dearth of research specifically targeting infants from bilingual families, such as infants from Chinese American families. Given that the developmental environment of infants and toddlers is more home-centric than that of preschoolers, investigating the HLE and ELD in this age group holds distinct research significance. Therefore, to address this gap, this study adopted a qualitative research approach to explore how the HLE influences the ELD of Chinese American infants and toddlers. This exploration was achieved by conducting semi-structured interviews, which served as the primary method of data collection, to gather parents’ perspectives and firsthand experiences regarding their children’s literacy activities within the home setting.

2 Research questions

To facilitate a structured and comprehensive exploration of the topic, this study is guided by three main research questions.

• RQ1: In the context of a bilingual environment, what are the parental beliefs regarding the influence of the HLE on infants’ early literacy progress?

• RQ2: What specific strategies and activities do parents employ to foster infants’ literacy development within the home environment?

• RQ3: Within the context of the bilingual environment, what are challenges or obstacles do parents face in nurturing infants’ literacy development?

3 Methodology

A qualitative research approach was selected for this study as it allowed researchers to deeply understand participants’ unique experiences in a chosen setting or regarding a particular case (Patton, 1999; Yin, 2017). To explore how the HLE influences children’s ELD in infancy in Chinese American families, in-depth interviews were chosen to collect data from 12 Chinese parents of infants. Patton (1999) considered in-depth interviews to be an appropriate method to use with a smaller sample size, thus, enabling us, in this case, to deeply understand infants’ literacy related development in a bilingual home environment.

3.1 Data sources

This study adopted semi-structured interviews and informal conversations as the primary data sources. This study involved engaging with 12 parents of infants in individual interviews.

3.1.1 Recruitment of participants

The recruitment process for participants was carried out using a purposeful sampling technique, targeting individuals who met specific criteria. To qualify for participation, all potential participants were required to:

• In the household environment, the primary family members communicate using both English and Chinese;

• Identify as Chinese American or Chinese nationals residing in the United States;

• Be aged between 18 and 50 years old;

• Be actively raising or have recently raised children (aged 0 to 3 years) within the context of the United States.

The lead researcher was invited by a colleague to join an online chatting group specifically composed of Chinese parents of infants living in America. This group was established as part of a larger research project on infant and toddler care, with all members living in Ohio. In the chat group, the lead researcher introduced the research topic in English, shared a brief overview of the study, and emphasized that all names in research materials would remain anonymous to encourage open and honest sharing, thereby initiating volunteer recruitment. Participants were informed that each would undergo at least one in-depth interview, lasting approximately 30 to 60 min. All interview questions were designed to elicit their perspectives on: The relationship between HLE and their infants’ emergent literacy development; firsthand experiences of how their infants develop literacy skills at home.

As the interviewer, the principal investigator—a doctoral candidate and researcher with 8 years of residency in the United States—shared cultural roots with participants (originating from China) and possessed bicultural (Chinese-American) understanding. Interviews were conducted primarily in English, leveraging the investigator’s native-level fluency in both Mandarin and English.

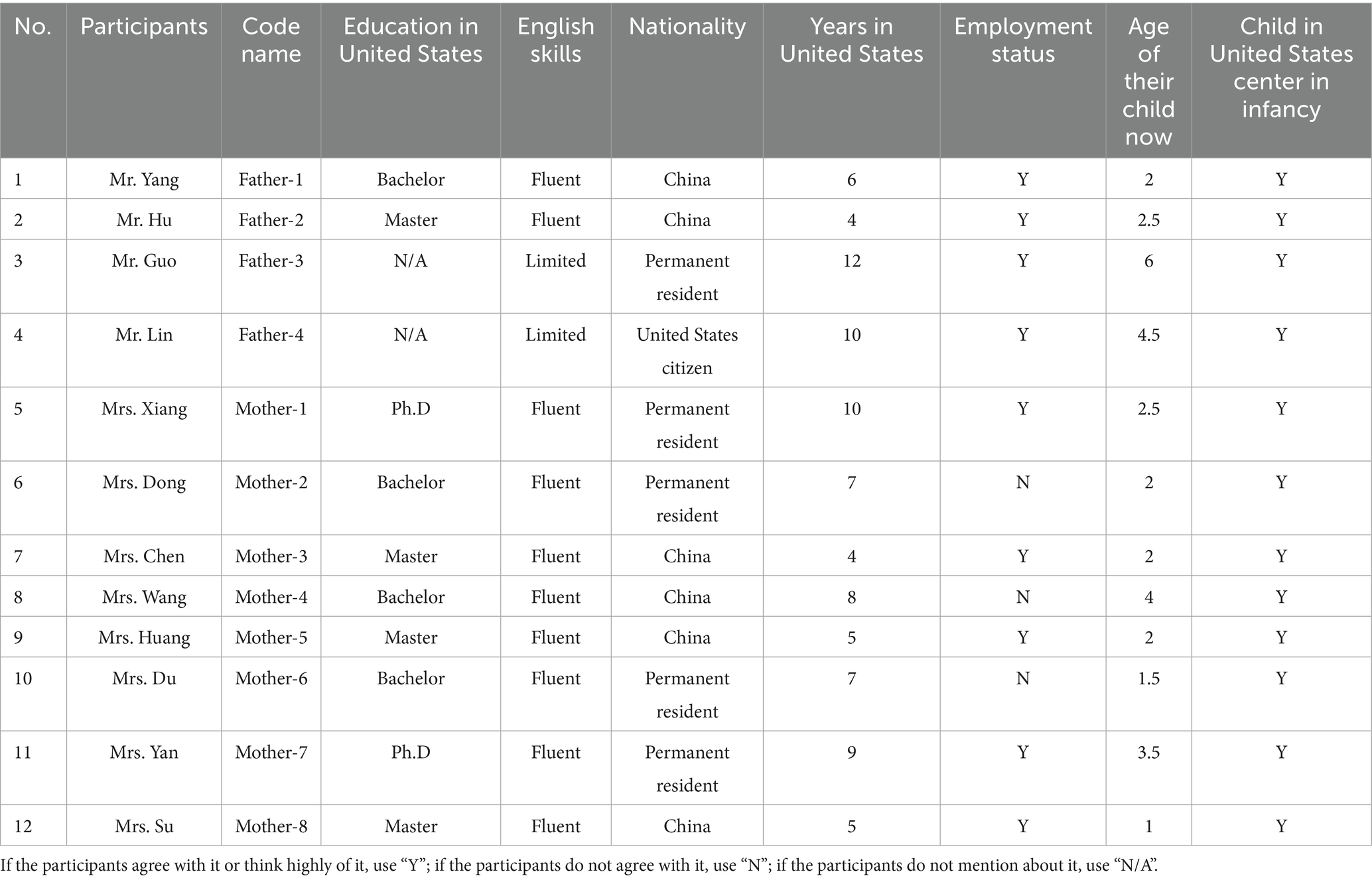

Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, defined as three consecutive interviews generating no new themes or sub-themes, with a stabilized thematic map. After analyzing the 8th interview, a preliminary framework of four core themes emerged. Interviews 9–11 further enriched thematic details within this framework. The 12th interview replicated existing patterns, confirming data saturation. Given this saturation outcome and the researcher’s practical constraints, recruitment was halted. Data from all 12 participants were retained for analysis (see Table 1). To protect the confidentiality of the participants, we used pseudonyms and implemented strict data security protocols, including password-protected storage and encrypted file sharing.

3.2 Interviews

In this study, interviewing served as the major method for data collection. Interviewing is widely recognized for its efficacy in gathering rich insights (Byrne, 2004). To gain a deeper insight into how infants’ early literacy ability develops within Chinese American families, in combination with the research purpose and literature review, a careful crafted list of semi-structured interview questions was devised.

Following the finalization of the interview protocol, the lead researcher first conducted a pre-interview with a randomly selected participant (Father-3). Subsequently, the transcript was discussed with two other researchers. Based on this discussion and incorporating Father-3’s feedback, two minor refinements were made to the interview protocol. For instance, within the second main question concerning “strategies,” a clarification of the term ‘strategy’ was added. This included providing illustrative examples to assist participants in answering should they express uncertainty about the concept. A follow-up interview was subsequently conducted with Father-3 to ensure the quality of the subsequent interviews.

Before the formal interview, we sent individual consent forms via email and requested each participant to return them electronically. All interviews were audio-recorded with the explicit permission granted by each participant before we started.

During the interviews, the interviewer made sure that participants were in a quiet environment that was both physically and mentally comfortable. In terms of interview techniques, the interviewer prioritized listening as much as possible, allowing participants to express themselves fully. When participants struggled to articulate certain content, the interviewer encouraged them to describe specific events—such as memorable experiences while communicating with their children or moments they felt were most significant in their child’s ELD. This approach avoided asking participants, as non-education professionals, to make specialized educational judgments. Instead, the researchers, as professionals, later analyzed and interpreted the information provided. Meanwhile, given that our study focuses on the infancy and toddler periods, during the interviews, we guided participants to concentrate on ELD and the HLE they established as parents during this specific timeframe. If participants wished to discuss how their earlier actions (when their children were 0–3 years old) influenced their children’s current behaviors, we were also attentive to such narratives.

Furthermore, supplementary follow-up interviews and informal conversations were scheduled whenever there were instances of ambiguity or additional questions that needed clarification by participants. Upon collating all interview transcripts, the researcher sent each transcript to its respective participant for verification of accuracy and confirmation that it faithfully represented their intended meaning. Thereby, the data collection phase of the study was completed.

3.3 Data analysis

Qualitative research methods enable researchers to delve into the inner thoughts and subjective experiences of participants, thereby providing a profound understanding of their perspectives and experiences on specific phenomenon (Creswell and Poth, 2016). To ensure the validity and trustworthiness of the data in this study, we employed member checking as promoted by Creswell (2007).

This study employed the thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006), systematically organizing the data into four distinct themes including: (a) parents’ perspectives of the HLE in infancy; (b) the significance of frequency and quality of literacy activities at home; (c) the importance of communication at home; (d) challenges and barriers for parental involvement in infant’s home literacy activities. The process encompassed the following six phases as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): familiarization with the data; generating initial codes; developing preliminary themes; reviewing and refining themes to ensure coherence with the dataset; defining and naming finalized themes; Producing the analytical report to interpret phenomena through the identified themes. Theme identification involved collaborative triangulation, with three researchers (Liu, Zhou, and Li) engaging in critical discussion to reach consensus on the final thematic structure. When differing opinions arose among the three of us, we engaged Helfrich, Chen, and Sulaimani as consulting reviewers, ultimately deferring to Liu for final decision. Throughout the research process, collective consensus was achieved in most cases. This methodological rigor—incorporating multiple coders and diverse data sources—enhanced the trustworthiness of the findings (Marshall and Rossman, 2011).

In presenting the findings, each theme is substantiated through verbatim participant quotations. These illustrative quotes preserve the authenticity of the data, faithfully capturing the multiplicity of perspectives while enabling in-depth interpretation. This analytical approach illuminates the practices and meanings underlying Chinese American parents’ approaches to ELD and HLE. Furthermore, thick description is achieved through detailed contextualization of the research setting and participant backgrounds—including their educational trajectories and socio-cultural perspectives—thereby strengthening the transferability of the study’s insights.

4 Findings

Findings of this present study were extracted from interview statements and they indicated that Chinese American families believe that HLE is crucial to infants’ ELD and people who spend more time with infants would play a significant role in their children’s literacy development. As all participators reported, they concurred on the significance of both the HLE and ELD. Notably, parents with infants over four months of underscored the critical nature of ELD as a determinant for their children’s future growth. The following sections elaborate each theme in sequence:

4.1 Parents’ perspectives of the HLE in infancy: I definitely think it is important…my baby, she is learning things

Though decades of researches have emphasized the significance of a rich HLE in early childhood education (Carroll et al., 2019; Ferjan Ramírez et al., 2020; Mullis et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020b; Vernon-Feaganset al., 2019), there is relatively less emphasis on its role specifically during infancy (Liu, 2020) whereas Suggate et al. (2018) assert that an individual’s earliest literacy development at birth. When participants were queried about their views of the significance of the HLE for infants’ growth, they unanimously expressed strong endorsement and positive attitudes toward engaging in literacy activities in infancy at home. Mother-1, who holds a Ph.D. and consistently implements high-frequency literacy activities within her home, exemplifies this perspective. She stated,

“I think it (HLE) is very important at home. I think it is a good way for us, for parents to build connections with our kid. They can learn things and we may find ways to understand them better. We always communicated with our baby, I need to work, but whenever I am at home, I would talk to my baby, and you know, my baby tried to talk back when she was around one. And I always brought books or other materials with sounds, and she really likes it. I think I know somehow, she is interested in voice, you know, all kinds of sounds, music, piano or something, I just need to make her feel the material that I brought is interesting.”

Other parents, including those who admitted to not engaging in literacy activities at home as regularly, also shared their insights and rationale. They explained,

“I definitely think it is important. I think what we do in the literacy activities, my baby, she is learning things. I always communicated with my baby, you know, she could pronounce “Mama” when she was just 4-month-old, and it surprised me. You know, I was told by one of my friends that kids are smart, and they learned things fast. So, even I was very busy, I would like to spend time with my baby and communicate with her.” (Mother-7’s Interview).

“The literacy environment is very important. We always find good materials, like books, you know, books with music and sounds, he likes it when he was a little. We also found that he is very sensitive to all kinds of sounds, you know, so we always tried to buy books or materials with music or sounds. We think it can attract him and make him feel interested in. Later, he always remembered what we read together, remember the music, I mean, he is also showed he is interested in books and readings.” (Mother-8’s Interview).

“I think it is important, when my child’s grandparents were here to help us, they took the major role to take care of our child, because we need to work, so we found that our kid understand Chinese better than English, you know, my parents could not speak English at all. If we were home, we would like to speak English, how to say, we tried to speak English cause we want our child to also understand English.” (Mother-5’s Interview).

Regarding successful experiences with parents’ perspectives on the HLE, one father recounted how his child’s behavior and development changed after they initiated a bedtime story routine,

“I think a good environment at home for kids, I mean, for. Them to read, is very important. My kid did not like readings when he was a little, maybe around 2 to 3, now I kind of think it is because we never did readings before he went to bed. I had a conversation with my friends, you know, my kid is really hard to put to sleep, because he always wants to play toys. So many of my friends told me that reading books before they go to bed is very good to, you know, to help them to sleep, I was trying to use this reading time to put him to sleep. But later I found that he is very interested in books after we had this activity, and he always asked us to read with him. Later, so now, he likes reading books, for example, he always tried to read books to his toys, he pretended his toys as his friends, he reads with toys, and all kinds of activities he would like to have books, or reading materials. So, I think the home literacy environment is very useful, you know.” (Father-3’s Interview).

As reflected in participants’ responses, it is evident that they unanimously recognized the importance of a HLE and expressed a desire to establish an enriching one for infants. Father-3 and Mother-1 both found that their children showed a fondness for literacy activities after they cultivate a conducive home literacy setting, particularly when these activities aligned with their child’s interests. As with all these Chinese parents, they all hold a common view of the importance of HLE in infancy, and like Mother-7 said, “even I was very busy, I would like to spend time with my baby and communicate with her.” However, what they believed cannot ensure that they know what types of literacy activities to do or how best to implement them with their infants at home.

4.2 The Significance of frequency and quality of literacy activities at home: play with them and talk often is really great

Researchers had indicated that the frequency and quality of home literacy activities played a vital role during early years and could predict children’s future language and literacy skills (Zimmerman et al., 2009; Salley et al., 2020). Responsiveness to children’s cues is also identified as a key element in this process. When participants were questioned about their engagement in literacy-related interactions with their kids at home, it was noted that those who had earned degrees in the United States reported a high or moderate frequency of such literacy activities at home. They shared that their children typically began speaking earlier than the other two participants without an American educational background. These latter two participants disclosed that they engaged in low-frequency literacy activities at home. Despite this, they mentioned that their children were capable of clearly pronouncing both Chinese and English words before the age of two.

Participants who conduct literacy related activities with a high and medium frequency at home indicated that the quality of literacy activity is an essential, Father-1 said,

“I think parents should make sure the quality of literacy activity. What we did, you. Know, we always checked with infant teachers about, uh, materials, like, what kind of materials should we buy or what they recommend. It is very important to have, you know, appropriate materials for children to learn. I think this is the reason that we continue to involve in reading activities with kid, and she began to talk very early, like 4-month-old.”

Mother-2 also shared,

“I always search things online, and I read other parents’ experience and. Recommendations. I want to provide my child a good language learning environment so that they can be good at speaking English. I need to find good toys, books or something, you know, we always tried to find materials according to my child’s interests and curiosity. I believe that talk, often with some question-based topics with child can improve something, join the, I mean, play with them and talk often is really great.”

Despite the fact that two participants reported engaging in literacy-related activities at home with a lower frequency, they also provided insights and implicitly acknowledged the importance of both the frequency and quality of such engagements. Father-3 expressed this sentiment when he said,

“My English is not very good, we came here very early. We always use Chinese at home. We need to go out to work, earn money, uh, so we do this (literacy activity) not a lot at home. But I believe it is very important because my friend’s kids can speak English very well, my child can only speak Chinese, you know, because our family often communicate in Chinese at home, my parents cannot speak English at all.”

Another parent, Father-4 also shared,

“I came to America 10 years ago. We all need to work all day and we cannot spend a lot of time with our baby at home……Both of us only have one day rest during a week, and my kid does not speak well when she was three. I think it is because we did not give her activities, we do not spend a lot of time with her, you know. Later, we worried about it, you know, she did not talk a lot, so we tried to hire somebody, a native speaker, who, uh, really can take care of her at home when we are working. After several weeks, we found, she talked, she communicated very well with the one we hired. We are very excited. So I think communication is really important to our baby’s development, literacy development.”

These two parents highlighted the pivotal role of communication within the home environment in relation to their children’s literacy development, recognizing it as an integral aspect of their daily interactions. The languages they used to communicate with their infants at home varied, and they acknowledged that this could significantly influence their child’s language acquisition and overall development progress.

4.3 The importance of communication at home: they gave my son the ipad…no communication at all

Regarding the early years’ literacy development at home, numerous researchers have emphasized the critical importance of communication between primary caregivers and children at home (Abels, 2020; Piazza et al., 2020; Van Schalkwyk et al., 2020). When participants were asked about the language they employed to communicate with their child at home, they uniformly shared their unique experiences and expressed a strong conviction that family communication significantly influence their child’s literacy development. As one mother shared:

“My parents were here to help us, and they could only speak Chinese, and sometimes, you know, they used the local dialect. Later, we found that our child also used the local dialect to express.” (Mother-5’s Interview).

It was also demonstrated in the interview with Mother-3,

“My child’s grandparents always used mandarin, and it was not standard, sometimes they used the northeast dialect to communicate, I found that my child can also use the northeast dialect.”

Furthermore, upon inquiry about any challenging experiences encountered during their children’s ELD in infancy, Father-4 identified a particular issue,

“Sometimes I needed to work and go outside to buy things for the whole family. Everytime I got back and found that grandparents were doing separate things but accompanying with my boy……His grandma was cooking, grandpa was watching the phone, and they gave my son the ipad, you know, my son was sitting on the couch, and, no communication at all. And I found that my son’s vocabulary was poor.”

In regard to dealing with their child’s Chinese grandparents, Mother-8 pointed to some differences in using dialects to communicate with her son. She said, “I found that my son can remix the languages that we used at home, and sometimes, I kind of think it is creative and shall be supported by family members. But what we can do is communicate more often with my boy.”

4.4 Challenges and barriers for parental involvement in infant’s home literacy activities: I need to work and my English level is not good

When asked about their challenges or barriers for parents to support their children’s literacy development in infancy, Father-3 pointed to a specific barrier,

“I think the biggest barrier for us is time and English skills. I need to work and my English level is not good. No one is helping us to take care of our baby, so we really do not have enough time to interact with my son. And I feel unsure about my English, you know, so we always said Chinese and dialect at home. I know that it is not good for him to go to school in America later. But we had no choice.”

Regarding the allocation of time for infants’ literacy activities, Father-3 recounted noticeable changes following their introduction of bedtime stories with their son during infancy. He shared, “I found some books based on his interests, like, he likes trucks and cars, so we would buy some books that include cars and trucks, and it is easy for us to read with him. I noticed that my son started to find books instead of toys sometimes, and he likes to read with us after we had this [bedtime story].”

Mother-2, another infants’ mother who had been in America for 7 years, highlighted the challenge posed by grandparents in her child’s early development period. She mentioned, “Grandparents often spent time on their phones and rarely interacted with my son. Sometimes I found a chance to discuss this issue with them, and they ignored it. I think we all do not have the same view about child rearing. This is the most struggling time for me. But I always interact with my son, and provide various reading materials, or I just talked to him all the time when I was at home.”

It also should be noted that Father-4 did not have time to interact with their daughter at home in infancy. Moreover, he lacked knowledge about suitable materials for fostering literacy skills. To address this, they hired a caregiver who could provide interaction and attention while they were working. Surprisingly, they found rapid progress in their daughter’s literacy development under the care provider’s guidance.

In Mother-7’s interview, she believed that the family environment is vital in young children’s literacy development. She said, “I realize that the language environment is very important, and I also think my child’s mood is also very important, so I always pay much attention to her attitude, and I found that she was very confident when we were interacting.” On the contrary, Father-1 revealed a contrasting experience, “My wife and my child’s grandma, they were unstable and moody. If the kid did not have a right pronunciation, and made mistakes, they would yell at her. I noticed that she [my daughter] was afraid of speaking and communicating. So every time she talked, she would like to be watchful and alert because she was afraid of making mistakes and they [her mom and grandma] would yell at her. I do not like their way, and I do not think it is good for her [his daughter], and I found she was shy, timid.”

5 Discussion

The dynamic relationship between the HLE and ELD in infants and toddlers has been the subject of extensive research. This study corroborates prior findings (De Houwer, 2020; Li, 2006; Weldemariam, 2025; Hoff, 2015), demonstrating that Chinese American parents value ELD and recognize HLE’s facilitative role. Specifically, stocking the HLE with picture books and educational play materials, coupled with active verbal engagement, significantly promotes infant ELD. Conversely, limited interaction and engagement during infancy may hinder ELD progression. Furthermore, the critical question of why children in bilingual households ultimately emerge as either bilingual or monolingual speakers remains a persistent focus in linguistic and sociological inquiry. This section addresses this complex issue.

5.1 Parental Perspectives and choices on bilingualism: do our child speak like we speak?

This study identifies two distinct sociolinguistic orientations among participants. The first cluster, exemplified by Mother-1, Mother-7, Father-2 and Mother-8, primarily comprises highly educated immigrants with elevated socioeconomic status. These parents hold professionally respected positions within both Chinese and American cultural contexts, representing upper-middle-class households or above. Fluent in both languages, they exhibit selective acculturation—consciously adopting cultural elements aligned with their values while rejecting incompatible practices regardless of origin.

These parents view bilingualism as critical for their children’s advancement and actively foster dual-language acquisition. They resist sacrificing Chinese literacy for English immersion despite recognizing its utility in American educational settings. Their enrichment of the HLE includes: Systematic acquisition of English picture books; Interactive audio toys (featuring English greetings/nursery rhymes); Father-2 illustrates this pattern: “My wife and I have purchased at least one new educational toy weekly since birth. By age one, Lucas [his son] owned dozens of English picture books—some of our s colleague’s gifts.” Furthermore, they strategically expand linguistic input environments through regular socialization with bilingual professional networks, purposeful exposure to cultural institutions (museums, parks), and curated immersion in public spaces that foster bicultural awareness. Those parents exposed their babies to an environment rich in vocabulary and listening comprehension. This kind of environment is closely related to early literacy learning (Bowman et al., 2021).

5.1.1 The “let it be” phenomenon: parental laissez-faire attitudes toward bilingualism often result in children becoming monolingual in the societal dominant language

Highly educated immigrant parents’ ELD practices bifurcate into distinct approaches. The first subtype, coded “vividly,” exemplifies “Let It Be” parenting. Mother-7, Mother-8 typifies this orientation, expressing confidence in their families’ capacity to support their children’s flourishing regardless of eventual monolingual or bilingual outcomes. This cultural self-assurance fosters a relaxed approach toward ELD and holistic development. During infancy, they predominantly use Chinese at home while implementing structured English exposure—such as dedicated English story time sessions before bed.

After nursery enrollment, when the child began absorbing English cultural codes and producing English vocabulary, Mother-7 and her husband adopted child-directed responsiveness: continuing parental speech in Chinese/English while accepting the child’s English replies. She articulates this philosophy:

Mother-7: “I absolutely value ELD and hope she becomes bilingual. Yet I resist coercive tactics—we follow her interests. Which story she chooses tonight determines which language I’ll use. My own studying was hard, came at the cost of childhood ease, even my parents always support me. Before my child was born, my husband and I committed to not push our baby. If literacy is not her strength, other legitimate passions are ok. Let it be.”

Post-preschool immersion in English-dominant environments (print-rich settings, peer interactions), with Chinese limited to overheard parental conversations, her child demonstrates accelerating English monolingualism. Mother-7 reports emerging English literacy (listening/speaking/reading/beginning writing) alongside only functional Chinese recognition. Consequently, they plan calibrated Chinese exposure—not for immediate proficiency, but to sustain cultural curiosity. She maintains optimism: “The cultural allure of Chinese will eventually call her home. When ready, she’ll embrace it.”

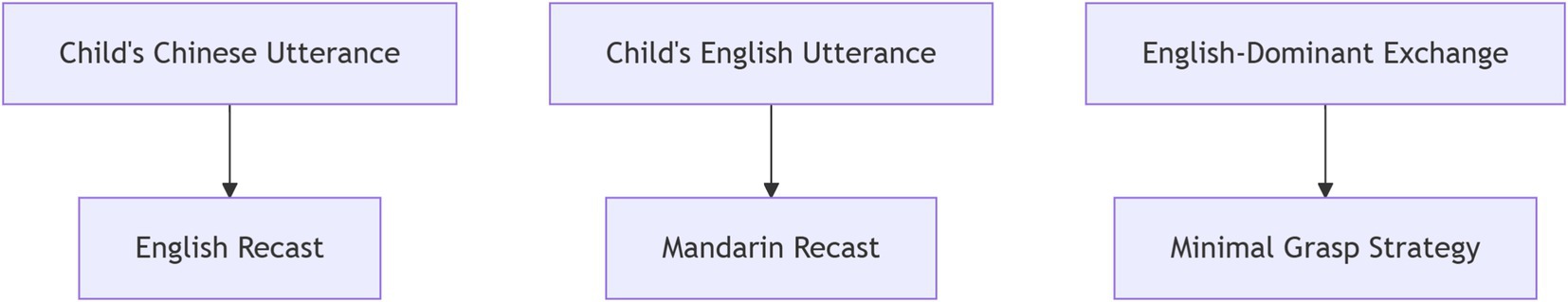

5.1.2 Highly competitive parents: strategic bilingual cultivation

The second subtype comprises highly competitive parents (e.g., Father-2, Mother-1) who view bilingualism as critical capital for global competitiveness. As Mother-1 asserted: “Mastering an additional language unlocks opportunities for greater success in our competitive world.” As Non-Interventionist Parents, they make Chinese-dominant home communication, structured English story time sessions. They had other competitive strategies: early academic orientation, introducing dual-language literacy cards during infancy, guided finger-pointing exercises (cf. Chinese “aspiring for exceptional achievement” parenting ethos). Mother-1 mentioned institutional reinforcement planning, let child go to weekend Chinese literacy school after kindergarten. They also persisted in implementing systematic input–output management (details in Figure 1).

About implementation of Minimal Grasp Strategy (Lanza, 1992, 1997), mother-1 often said “Could you say that in Chinese/English?” in gentle elicitation during comfortable interactions.

“But you cannot always use this talking method (the ‘ask-in-Chinese’ thing). You know, sometimes when my kid’s really wanting something right now, or she’s super excited telling me or my husband something – if I do that then, she’ll just get annoyed with us. I know this, I mean, I really know when it’s the right time to help her practice both languages.” (Mother-1’s Interview).

Despite current lag in age-normed English production compared to monolingual peers, mother-1 and father-2 reported that kids are on the road to being bilinguals emerging bilingual processing patterns. They would maintain consistent investment in biliteracy development across all domains (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), demonstrating strong confidence in their children’s attainment of balanced Chinese-English proficiency.

Now, let us discuss the second pattern of language and socio-cultural orientation and choice. This orientation is observed among another group of individuals, such as Father-3, Father-4, and Mother-4. They lack advanced U.S. degrees or formal education, engage in self-employment or informal work (e.g., being a full-time homemaker). Through personal effort or marriage, they now belong to the middle class or a higher socioeconomic stratum.

Though Father-3 and Father-4 have lived in the United States for over a decade, their English proficiency remains limited. Both run small businesses—Father-3 operates a grocery store, while Father-4 manages a restaurant—with demanding schedules that often keep them working long hours in their shops. Although their businesses stabilized before their children were born, their heavy workloads, coupled with traditional Chinese beliefs like “men work outside while women manage the household,” have limited their involvement in child-rearing and education. Primary caregiving responsibilities thus fall to the grandparents. Mother-4, a full-time homemaker who has resided in the U.S. for eight years, cares for her 4-year-old daughter Rebecca. Rebecca never attended nursery and was solely under her mother’s care before starting preschool. Their approach to navigating Chinese and American languages and cultures reflects a go-with-the-flow mentality. Believing their children will settle and thrive in the U.S., they prioritize mastery of the dominant local language for ELD to foster integration into community life and lay an academic foundation. While bilingualism is seen as ideal, monolingual English is also deemed acceptable. As Father-3 remarked: “It’s fine, if it does not affect daily life—my English is not great, but I’ve lived here [the U.S.] all these years.”

Mother-4 shared that before Rebecca entered preschool, she frequently taught her English listening, speaking, and reading skills. She also actively encouraged Rebecca to socialize with neighborhood peers, hoping she would form local friendships to better adapt to her environment. “Making friends is crucial. I want her to build many friendships. You know, children love to imitate—they imitate their parents and their friends,” she explained.

Then, we will categorize and examine the early home literacy practices associated with this language-cultural orientation.

5.1.3 Busy working parents: care by Chinese-speaking grandparents leading to children becoming passive emergent bilinguals

Father-3 and Father-4 recognize that the HLE is crucial for ELD and consider their children’s ELD extremely important. Having limited English proficiency themselves, they observed friends’ children speaking English well and thus strongly desire the same for their own children. However, as they run “mom-and-pop shops” requiring them to work long hours almost every day to support the family, their children are primarily raised by grandparents who speak no English. While they seem concerned about their children’s ELD, they take little action—a manifestation of lacking impact belief.

As mentioned earlier, both fathers acknowledged drawbacks of grandparent caregiving. For instance: The home environment primarily uses Mandarin or dialects, grandparents provide basic supervision and care rather than engaging in educational dialog or rich interaction. Consequently, their children spoke almost exclusively Chinese or dialects before entering preschool or kindergarten. Father-3 noted his child’s disinterest in reading, while Father-4 mentioned limited family communication resulting in his child barely speaking by age three.

Humans are social beings, developing through interaction with the world around them. Both fathers discussed the role of people outside the immediate family in aiding their children’s ELD. For example, Father-3 learned from a friend about the practice of reading English stories at bedtime. After implementing this, he observed his child gradually developing an interest in reading.

“Boys, you know, they usually love cars, trucks, diggers… all that stuff. Tom’s (his son) the same. So we went out and got him some cartoon books just about cars. They’ve got pictures and simple info about different trucks and cars, plus some stories about little cars too. At bedtime, we let him pick which one he wants, and we read it to him. Sometimes, though, if we are just too tired, we’ll put on an English cartoon for him instead – like Thomas the Tank Engine. Oh yeah, and they make picture books for that Thomas show too! We bought him some of those, and he’s really into them.” (Father-3).

By enriching the HLE based on the child’s interests and providing quality interaction through shared reading, they helped Tom overcome some ELD disadvantages. After Tom entered kindergarten—an environment saturated with English symbols—Father-3 noted they still primarily speak Chinese at home, Tom sometimes responds in English, and Father-3 believes Tom can now communicate fairly well in English with peers his age.

In contrast to Father-3’s approach, Father-4 chose to hire a native English-speaking nanny to help care for his child. Within weeks, they were excited to observe their child communicating effectively with the nanny. This experience made them fully realize the importance of interactive communication with their child. The nanny cared for Olivia (Father-4’s daughter) for nearly a year until she entered preschool. Currently, Father-4 believes Olivia’s ELD is slightly behind her peers, explaining, “Maybe she’s just not be naturally good at these.” Olivia’s Chinese listening and speaking skills are slightly stronger than her English, while her English reading and writing are somewhat better than her Chinese.

5.1.4 High-impact belief: mother’s consistent, high-quality interaction supports child’s mastery of dominant language

As a full-time mother, Mother-4 dedicates ample time to nurturing and educating Rebecca, investing significant energy and passion into her development—including but not limited to ELD. She firmly believes children require active guidance, stating, “Kids do not just grow up on their own if left alone.” Even before Rebecca’s birth, she proactively sought out prenatal and parenting books to self-educate.

“Children love to imitate… My husband and I mostly speak English at home, so Rebecca started using simple English words very early. For example, when she was tiny, I’d say ‘here’ while handing her a bottle. She remembered it and would try to say ‘here’ when passing things to me—that really encouraged me! I talked to her constantly, even knowing she might not understand. Whenever we encountered something new, I’d repeat its name several times. I found this works well—babies love repetition!”(Mother-4).

Through these daily interactions, Mother-4 developed her own practical “theory” of education, which she finds highly effective. This reflects strong parental self-efficacy (PSE), fueling her joy in sustained engagement with Rebecca and motivating her to refine her approach. Now preparing for kindergarten, Rebecca speaks English fluently and interacts naturally with local peers, according to Mother-4. Rebecca’s Chinese, however, remains limited to basic greetings and simple vocabulary, as intentional Chinese literacy activities were rarely prioritized.

6 Limitations and future research

This study examines the perspectives and practices of 12 Chinese American parents regarding ELD and HLE, demonstrating the profound influence of HLE on ELD. This study employed purposeful sampling to identify participants, ultimately selecting 12 Chinese American parents based on predetermined criteria. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. Hence, the recommendations arising from this research may have limited applicability when generalized to broader contexts.

First, regarding data collection methodology. While infants and toddlers may not yet possess strong, self-determined cultural preferences like adults, their parents—constituting the primary agents within the child’s immediate environment—hold distinct linguistic, cultural, and socio-cultural orientations. These parental orientations imperceptibly shape the infant’s developing cultural inclinations from birth. Before children independently engage beyond the home and community, parental choices in language and culture effectively become the child’s own. Consequently, this study did not directly assess children in immigrant bilingual households. Instead, we gathered data on HLE and ELD in Chinese American families primarily through interviewed only parents. We contend that well-structured interview protocols render parental reporting developmentally appropriate for this age group.

Upon reflection, we recognize that when detailing how specific parental decisions may influence child development, incorporating multi-modal data (e.g., photographs, artifacts) would have enriched the analysis. Such materials could complement the thematic analysis by enabling narrative techniques to foreground participants’ internal perspectives. This integrated approach might offer novel insights for both readers and future researchers.

Second, regarding sample characteristics. All participating parents in this study were raising only children, precluding examination of sibling effects. Given the established significance of siblings in children’s ELD, this sample limitation represents a substantive gap. Furthermore, maternal and paternal practices often diverge substantially, and relying solely on one parent’s report of household literacy practices risks introducing reporting bias. Additionally, child gender significantly mediates parenting behaviors—research indicates mothers engage in more verbal interactions with daughters than sons, while fathers communicate less with temperamentally inhibited children compared to sociable ones (Leaper et al., 1998; Patterson and Fisher, 2002). While participant selection prioritized Chinese American parent identity and engagement willingness, insufficient attention was given to: (a) distinctions between maternal and paternal practices, and (b) differential parenting patterns based on child gender. Future studies should address this by recruiting both parents within households for co-reporting on ELD and HLE, while explicitly examining the moderating effects of child gender on observed interaction patterns.

Finally, regarding study duration. Although this qualitative research aimed to analyze Chinese American parents’ early literacy practices and perspectives across extended timeframes, its cross-sectional design inherently limits our ability to pinpoint developmental milestones or trace the progression of literacy acquisition. Consequently, we recommend longitudinal investigations in future research on ELD within Chinese American families. Such designs could elucidate developmental trajectories and identify critical junctures, ultimately enabling deeper exploration of HLE influence mechanisms and ELD pathways.

7 Conclusion

This study highlights the significance infants’ individual needs and interests inherent Bilingual immigrant families’ HLE pose more challenges and barriers to caregivers, especially those who are non-English speakers or unable to allocate sufficient time. These circumstances often result in a lack of skills necessary to foster infants’ literacy development through an appropriate home setting. To better involve caregivers in infants’ literacy development, the foremost strategy should be to establish a tailored HLE that caters to each infant’s unique requirements and interests. It is imperative for caregivers to recognize and embrace their pivotal role throughout this entire development process. By doing so, they can effectively contribute to creating a conducive atmosphere that facilitate infants’ ELD.

Notably, infants and toddlers in Chinese American immigrant families may not become emergent bilinguals. Without parents’ proactive cultivation of the HLE, consistent engagement in early literacy activities, and firm bilingual impact belief, children are highly likely to develop as English monolinguals. Thus, “our children may not be able to speak our heritage language.”

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Hubei Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YaL: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. XZ: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Resources. YiL: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation. SH: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. FC: Validation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Resources. MS: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Educational Department of Education, Key Project, 2022GA066, Ecological Systems Approach to Nurturing Healthy Development: Constructing Coordinated Education Mechanisms among Family, Preschool and Community.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abels, M. (2020). Triadic interaction and gestural communication: Hierarchical and child-centered interactions of rural and urban Gujarati (Indian) caregivers and 9-month-old infants. Dev. Psychol. 56:1817. doi: 10.1037/DEV0001094

Bowman, B. T., Donovan, M. S., and Burns, M. S. (2021). Eager to learn: Educating our Preschoolers. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design : Harvard University Press.

Byrne, B. (2004). Qualitative interviewing. In: Seale C. Eds. Researching society and culture (pp.179–192). Sage Publications.

Carroll, J. M., Holliman, A. J., Weir, F., and Baroody, A. E. (2019). Literacy interest, home literacy environment and emergent literacy skills in preschoolers. J. Res. Read. 42, 150–161. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12255

Chen-Hafteck, L. (2021). “Music and language development in early childhood: integrating past research in the two domains” in Music in the lives of young children (London, UK: Routledge), 179–192.

Cole, J. (2011). A research review: the importance of families and the home environment. Originally written by Angelica Bonci, 2008, revised June 2010 by Emily Mottram and Emily McCoy and March 2011 by Jennifer Cole. National Literacy Trust. Available online at: http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/assets/0000/7901/Research_reviewimportance_of_families_and_home.pdf (Accessed 8 April 2025)

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing. Among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Curtis, K., Zhou, Q., and Tao, A. (2020). Emotion talk in Chinese American immigrant families and longitudinal links to children’s socioemotional competence. Dev. Psychol. 56:475.

De Houwer, A. (2020). Why do so many children who hear two languages speak just a single language? Cambridge, United Kingdom: Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht 25, 7–26.

De Houwer, A. (1999). “Environmental factors in early bilingual development: the role of parental beliefs and attitudes” in Bilingualism and Migration. eds. G. Extra and L. Verhoeven (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 75–95.

Duff, F. J., Reen, G., Plunkett, K., and Nation, K. (2015). Do infant vocabulary skills predict school‐age language and literacy outcomes? J. Child Psychology Psychiatry 56, 848–856. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12378

Feng, L., Gai, Y., and Chen, X. (2014). Family learning environment and early literacy: A comparison of bilingual and monolingual children. Econom. Educ. Rev. 39, 110–130. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.12.005

Ferjan Ramírez, N., Lytle, S. R., and Kuhl, P. K. (2020). Parent coaching increases conversational turns and advances infant language development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 3484–3491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921653117

Harris, A., and Goodall, J. (2007). Engaging parents in raising achievement: do parents know they matter? London: Department for Children, Schools and Families. Available at: www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/DCSF-RW004.pdf

Hart, B., and Risley, T. R. (1995). The early catastrophe: the 30 million word gap by age 3. Am. Educ. 17, 4–9.

Hoff, E. (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Dev. 74, 1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612

Hoff, E. (2015). What explains the correlation between growth in vocabulary and grammar? New evidence from parent-child discourse. J. Child Lang. 42, 1–24. doi: 10.1111/desc.12536

Hunt, S., Virgo, S., Klett-Davies, A. P., and Apps, J. (2011). Provider Influence on the Home Learning Environment. Department for Education. Research Report. Available at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/3998/1/3998_DFE-RR142.pdf (Accessed July 13, 2025).

Iverson, J. M. (2021). Developmental variability and developmental cascades: lessons from motor and language development in infancy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 30, 228–235. doi: 10.1177/0963721421993822

Johnston, C., and Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting self-efficacy. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 18, 167–175.

Jung, S., Choi, N., and Jung, S. (2019). The effects of the initial Reading experience of infancy on the Reading and Academic Achievement of Elementary First Graders. On Early Childhood Development (ICECD 2019), 1.

King, L. S., Querdasi, F. R., Humphreys, K. L., and Gotlib, I. H. (2021). Dimensions of the language environment in infancy and symptoms of psychopathology in toddlerhood. Dev. Sci. 24:e13082. doi: 10.1111/desc.13082

Lamb, M., Bornstein, M., and Teti, D. (2002). Development in infancy: An introduction. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Lanza, E. (1997). Language contact in bilingual two-year-olds and code-switching: Language encounters of a different kind? International Journal of Bilingualism 1, 135–162.

Leaper, C., Anderson, K. J., and Sanders, P. (1998). Moderators of gender effects on parents' talk to their children: a meta-analysis. Developmental psychology 34:3.

Lerkkanen, M. K. (2019). “Early language and literacy development in the Finnish” in The SAGE handbook of Developmental Psychology and early childhood education, 403–417. Sage Publications.

Li, G. (2006). Biliteracy and trilingual practices in the home context_ case studies of Chinese-Canadian children. J Early Childhood Literacy 6. doi: 10.1177/1468798406069797

Liu, Y. (2020). Reconsidering parental involvement: Chinese parents of infants in American child development center. (Doctoral dissertation, Ohio University).

Liu, Y., Sulaimani, M. F., and Henning, J. E. (2020). The significance of parental involvement. In the development in infancy. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 10, 161–166. doi: 10.5590/JERAP.2020.10.1.11

Marshall, C., and Rossman, G. (2011). Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publication.

Mascarenhas, S. S., Moorakonda, R., Agarwal, P., Lim, S. B., Sensaki, S., Chong, Y. S., et al. (2017). Characteristics and influence of home literacy environment in early childhood-centered literacy orientation. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare 26, 81–97.

Mason, J., and Allen, J. B. (1986). A review of emergent literacy with implications for research and practice in reading. Rev. Res. Educ. 13, 3–47.

Matvichuk, T. (2015). The influence of parent expectations, the home literacy environment, and parent behavior on child reading interest. Paper: Senior Honors Theses, 436.

Melhuish, E., Phan Mai, B., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I, and Taggart, B. (2008). Effects of the home learning environment and preschool center41experience upon literacy and numeracy development in early primary school. Journal of Social 64, 95–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00550.x

Mullis, R. L., Mullis, A. K., Cornille, T. A., Ritchson, A. D., and Sullender, M. S. (2004). Early literacy outcomes and parent involvement. Florida State University. Available at: https://www.earlyliteracyweb.com/pdf/EarlyLitNParentInvolvement.pdf (Accessed July 13, 2025).

Patterson, G. R., and Fisher, P. A. (2002). Recent developments in our understanding of parenting: Bidirectional effects, causal models, and the search for parsimony. Handbook of parenting 5, 59–88.

Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health services research 34:1189.

Pemberton, J., Rademacher, J., and Anderson, G. (2006). Grandparents raising grandchildren: What educators should know. 232–253. Available at: https://twu-ir.tdl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/da657b83-5174-4fc1-ae41-6a7b298573bb/content (Accessed July 13, 2025).

Piazza, E. A., Hasenfratz, L., Hasson, U., and Lew-Williams, C. (2020). Infant and adult brains. Are coupled to the dynamics of natural communication. Psychol. Sci. 31, 6–17. doi: 10.1177/0956797619878698

Salley, B., Brady, N. C., Hoffman, L., and Fleming, K. (2020). Preverbal communication complexity in infants. Infancy 25, 4–21. doi: 10.1111/infa.12318

Sinclair, E. M., McCleery, E. J., Koepsell, L., Zuckerman, K. E., and Stevenson, E. B. (2018). Home literacy environment and shared reading in the newborn period. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 39, 66–71. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000521

Suggate, S., Schaughency, E., McAnally, H., and Reese, E. (2018). From infancy to adolescence:The longitudinal links between vocabulary, early literacy skills, oral narrative, and reading comprehension. Cognitive Develop 47, 82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.04.005

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., and Taggart, B. (2004). The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project technical paper 12: The final report-effective pre-school education.

Tabors, P. O., and Snow, C. E. (2001). Young bilingual children and early literacy development. Handbook Early Literacy Research 1, 159–178.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Luo, R., McFadden, K. E., Bandel, E. T., and Vallotton, C. (2019). Early home learning environment predicts children’s 5th grade academic skills. Appl. Develop. Sci. 23, 153–169.

Tse, L. (2001). Resisting and Reversing Language Shift: Heritage-language Resilience among U. S. Native Biliterates, Harvard Educational Review 71, 676–708.

Van Schalkwyk, E., Gay, S., Miller, J., Matthee, E., and Gerber, B. (2020). Perceptions of. Mothers with preterm infants about early communication development: a scoping review. South African. J. Commun. Disord. 67, 1–8. doi: 10.4102/sajcd.v67i1.640

Van Tonder, B., Arrow, A., and Nicholson, T. (2019). Not just storybook reading: Exploring the relationship between home literacy environment and literate cultural capital among 5-year-old children as they start school. Austral. J. Lang. Liter., 42, 87–101.

Walker, D., Sepulveda, S. J., Hoff, E., Rowe, M. L., Schwartz, I. S., Dale, P. S., et al. (2020). Language intervention research in early childhood care and education: a systematic survey of the literature. Early Child Res. Q. 50, 68–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.02.010

Wang, Y., Jung, J., Bergeson, T. R., and Houston, D. M. (2020a). Lexical repetition properties of caregiver speech and language development in children with cochlear implants. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63, 872–884. doi: 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00227

Wang, Y., Williams, R., Dilley, L., and Houston, D. M. (2020b). A meta-analysis of the predictability of LENA™ automated measures for child language development. Dev. Rev. 57:100921. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2020.100921

Weizman, Z. O., and Snow, C. E. (2001). Lexical input as related to children's vocabulary acquisition: effects of sophisticated exposure and support for meaning. Dev. Psychol. 37, 265–279. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.265

Weldemariam, K. (2025). The home literacy environment as a venue for fostering bilingualism and biliteracy: the case of an Ethio-Norwegian bilingual family in Oslo, Norway. J. Early Child. Lit. 25, 3–28. doi: 10.1177/14687984221109415

Wright, T. S., Cabell, S. Q., Duke, N. K., and Souto-Manning, M. (2022). Literacy learning for infants, toddlers & preschools: Key practice for educators. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Zellman, G. L., and Watermann, J. M. (1998). Understanding the impact of parent 46 school involvement on children’s educational outcomes. J. Educ. Res. 91, 370–380.

Zhan, Y. (2020). The role of agency in the language choices of a trilingual two-year-old in conversation with monolingual grandparents. First Language 40, 13–32. doi: 10.1177/0142723720923488

Zimmerman, F. J., Gilkerson, J., Richards, J. A., Christakis, D. A., Xu, D., Gray, S., et al. (2009). Teaching by listening: the importance of adult-child conversations to language development. Pediatrics 124, 342–349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2267

Keywords: qualitative, early literacy development, home literacy environment, infant, toddler, Chinese American families

Citation: Liu Y, Zou X, Li Y, Helfrich S, Chen F and Sulaimani MF (2025) “Do our children speak like we speak?” A qualitative study on Chinese American parents’ perspectives and practices regarding early literacy development and home literacy environment in infants and toddlers. Front. Educ. 10:1598693. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1598693

Edited by:

Germán Zárate-Sández, Western Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jeffrey Liew, Texas A&M University, United StatesRachelle Johnson, Florida State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Zou, Li, Helfrich, Chen and Sulaimani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yifan Li, bGl5aWZhbmhvbWVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Yanhui Liu

Yanhui Liu Xuecheng Zou

Xuecheng Zou Yifan Li

Yifan Li Sara Helfrich3

Sara Helfrich3 Feifei Chen

Feifei Chen Mona F. Sulaimani

Mona F. Sulaimani