- The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Introduction: The views of school staff on student non-attendance have scarce representation in the existing literature. This systematic literature review explores the perspectives of school staff on student non-attendance, synthesizing findings from eleven qualitative and mixed-method papers.

Methods: Using a thematic synthesis approach, the review investigates how non-attendance is conceptualized by school staff and the extent to which their perspectives reflect its multidimensional nature.

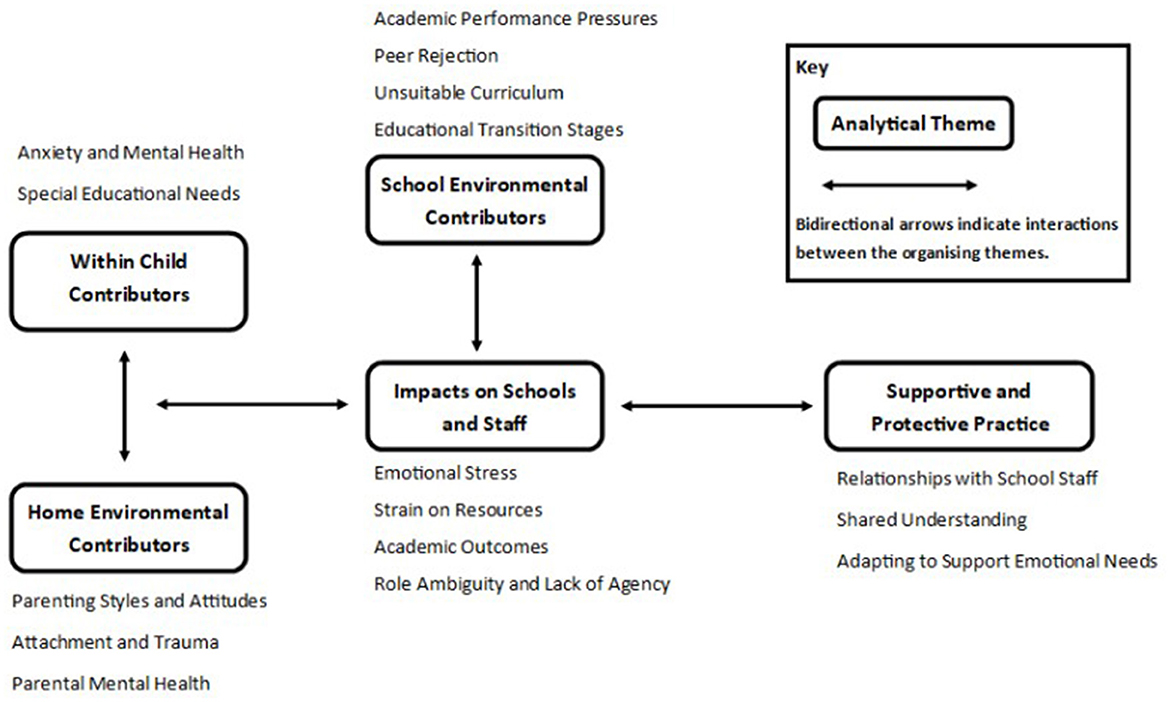

Results: School staff described the factors contributing to student non-attendance as: (1) within-child, such as anxiety, mental health, and special educational needs; (2) home environmental influences, including parenting styles and attachment needs; (3) school-related factors such as academic pressures, unsuitable curricula, and peer rejection; and (4) the emotional and resource strain experienced by school staff.

Discussion: Findings suggest that conceptualizations of non-attendance, such as “emotionally based school avoidance” (EBSA) or “school refusal,” may influence staff interpretations and strategies for intervention. Eco-systemic approaches emphasizing collaborative relationships between schools, families, and external agencies are highlighted by school staff. This review underscores the need for flexible, context-sensitive approaches to support attendance, informed by clear, strengths-based terminology and increased collaboration between stakeholders. Future research should explore the integration of systemic models into school policies and address the well-being of staff supporting student non-attendance.

Introduction

School non-attendance has long been a focus of concern within education and psychology, as its complex and multifaceted nature impacts not only students and their families but also school systems and broader society (Bond et al., 2024b). Understandings of school non-attendance have evolved considerably over the past few decades, moving from a narrow focus on individual behavioral factors, framed as “truancy” or “school refusal,” to a more nuanced, systemic understanding that considers the interplay of personal, family, and school-related influences (Elliott and Place, 2019; Bond et al., 2024a). This shift reflects a growing recognition of the need for contextually grounded approaches that account for the variety of factors driving school attendance problems (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020). This recognition has led to the development of systemic models that emphasize the interaction of individual, family, school, and societal factors. Notably, the Kids and Teens at School (KiTeS) Framework (Melvin et al., 2019) conceptualizes school attendance and absenteeism within nested environmental systems. Similarly, Enderle et al. (2024) adopt an ecological systems approach to analyse school attendance difficulties, highlighting the dynamic interplay of proximal and distal factors that shape attendance behavior. These models reinforce the importance of viewing attendance issues as embedded within broader ecological contexts, thus moving beyond individual-level explanations. In recent years, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the urgency surrounding school attendance issues has intensified. This urgency has underscored a need for research that explores how school staff understand non-attendance, offering insights critical to effectively addressing this growing challenge (Bond et al., 2024b).

A critical aspect of understanding and addressing school non-attendance lies in the terminology and conceptual frameworks used by researchers and practitioners. In the literature, terms such as “school refusal,” “truancy,” “school withdrawal,” and “school exclusion” have been prevalent. More recently, terms like “emotionally based school avoidance” (EBSA) and “emotionally based school non-attendance” (EBSNA) have emerged to reflect situations where anxiety and emotional distress significantly contribute to students' difficulties attending school (West Sussex Educational Psychology Service, n.d.; Corcoran et al., 2022). Yet, as noted by Corcoran and Kelly (2023) this terminology has its limitations; potentially implying a within-person deficit and overlooking broader systemic factors, as well as assuming anxiety as the primary cause of non-attendance. It can be seen that different terms each hold distinct implications regarding the perceived causes and responsibilities associated with non-attendance (Heyne et al., 2019). For example, conceptualizations of non-attendance as a multi-systemic issue tend to advocate for functional, multi-system approaches to address the root causes of attendance problems. Kearney and Graczyk's (2020) multi-dimensional, multi-tiered model highlights the need to examine attendance problems at the individual, family, and school levels, allowing for targeted interventions that respond to unique contextual factors. In addition to addressing absenteeism reactively, the model advocates for proactive, universal supports aimed at promoting engagement and preventing attendance problems. These Tier 1 interventions include fostering positive school climates, strengthening teacher-student relationships, enhancing social-emotional competencies, and regularly screening for early signs of disengagement (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020). The prevailing frameworks and definitions that inform current understandings of non-attendance influence understandings of how to support attendance problems. However, while recent reviews have considered school staff perspectives within broader analyses of professional or multi-stakeholder views (Hamadi et al., 2024; Hejl et al., 2024), a dedicated synthesis focusing specifically on how school staff understand, and support attendance issues has not yet been undertaken.

Qualitative research has potential to inform policy and practice (Thomas and Harden, 2008), this review therefore seeks to draw on school staff perspectives on attendance issues and their reflections on intervention to support improved attendance by answering the following questions: (1) How is school non-attendance conceptualized across research exploring school staff views? and (2) To what extent does the current research on school staff views of non-attendance reflect the multidimensional nature of the issue?

Addressing these questions may help to bridge the gap between theoretical frameworks and practical applications, illuminating how conceptual understandings of non-attendance influence day-to-day practices and shaping future research, policy, and intervention strategies aimed at reducing school non-attendance.

Methods

Systematic literature review

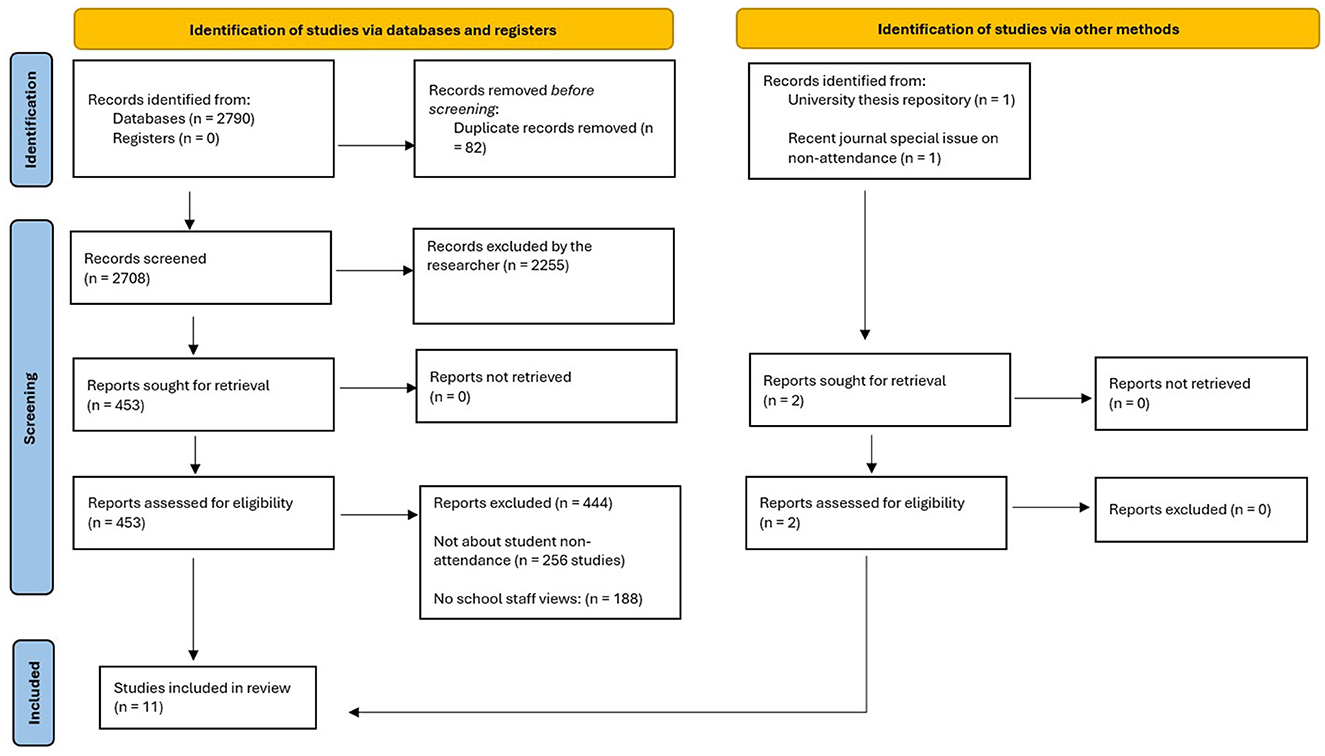

To structure the review process, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al., 2021) was used with a thematic synthesis to integrate findings and generate insights beyond the individual included studies (Flemming and Noyes, 2021).

Search strategy and information sources

In October 2024, systematic searches were conducted of relevant databases including: PsycInfo, Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Web of Science, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), EBSCO host, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (see Figure 1). The search terms were developed through consultation with the existing literature to reflect the broad and evolving terminology used to describe school attendance problems (Boaler and Bond, 2023; Corcoran and Kelly, 2023). Terms such as “emotionally based school avoidance”, “truancy”, or “school exclusion” were considered, but ultimately not used as primary search terms in order to maintain a wide scope and avoid over-narrowing the search to specific subtypes. For instance, while EBSA has become a prominent term in the UK context, its use is not consistent internationally or over time, limiting its utility for a systematic search (Boaler and Bond, 2023). Similarly, “truancy” and “school exclusion” are typically associated with discrete or policy-defined attendance behaviors, which may not fully capture the broader range of attendance difficulties explored in this review. As such, more inclusive and frequently used umbrella terms like “school non-attendance” and “school absenteeism” were prioritized to ensure coverage of relevant literature across educational and geographical contexts.

Figure 1. Screening Process, from Page et al. (2021).

The following terms were therefore used to search the databases:

(“school refusal” OR “school absenteeism” OR “school non-attendance” OR “school attendance problems” OR “chronic school absenteeism” OR “school refusal behavior”)

AND (“school staff” OR “teacher” OR “assistant” OR “educator”)

AND (“view*” OR “perspective*” OR “perception*” OR “experience*”).

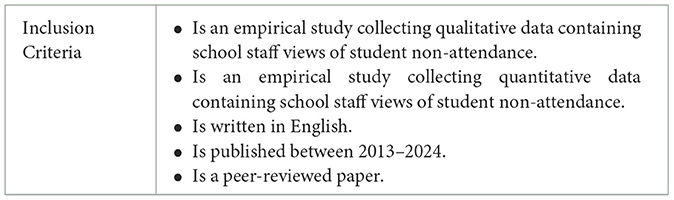

Inclusion criteria

Papers were filtered by title to remove those not related to school staff views of school non-attendance, leaving 453. The abstracts and keywords in the remaining articles were used to identify any that did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Inclusion criteria were developed referring to criteria used in existing systematic reviews on school attendance (e.g., Boaler and Bond, 2023). There were two reviewers; the first reviewer searched for information sources independently and assessed studies for inclusion. Each paper was assessed against each of the eligibility criterion as “eligible/not eligible/might be eligible (full-text screen needed).” The full text was also retrieved when abstracts contained insufficient information. Eleven reports were sought for retrieval and all could be accessed. Articles were included when inclusion criteria were met from the full text. The second reviewer independently assessed 3 of papers. Disagreements or ambiguities were resolved through discussion. Data was extracted by the first reviewer and independently checked for consistency and clarity by the second reviewer.

The quality assessment process was implemented using the Weight of Evidence (WoE) framework, specifically focusing on WoE A and WoE C criteria, as outlined by Gough et al. (2017). WoE A evaluates the methodological quality of each study, a checklist (Woods, 2020) examining factors such as research design, sample selection, and data analysis techniques to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings was used, scoring each paper out of 20. A sample of papers (27%) were also assessed by second author and any disagreement resolved through collaborative discussion. Papers were categorized into high (16–20), medium (11–15) and low quality ( ≤ 10). WoE A assessment indicated that all studies scored medium or high for methodological quality, reflecting positively upon the work conducted in this area. WoE C assesses the relevance of each study to the specific research questions of the review, specific criteria were developed by the authors determining how well the study's focus aligns with the context of school staff perspectives on school non-attendance (see additional material for WoE C criteria). By applying these criteria, the researcher assessed whether the included studies were both methodologically sound and relevant to the research objectives.

Results

Study characteristics and summary of findings

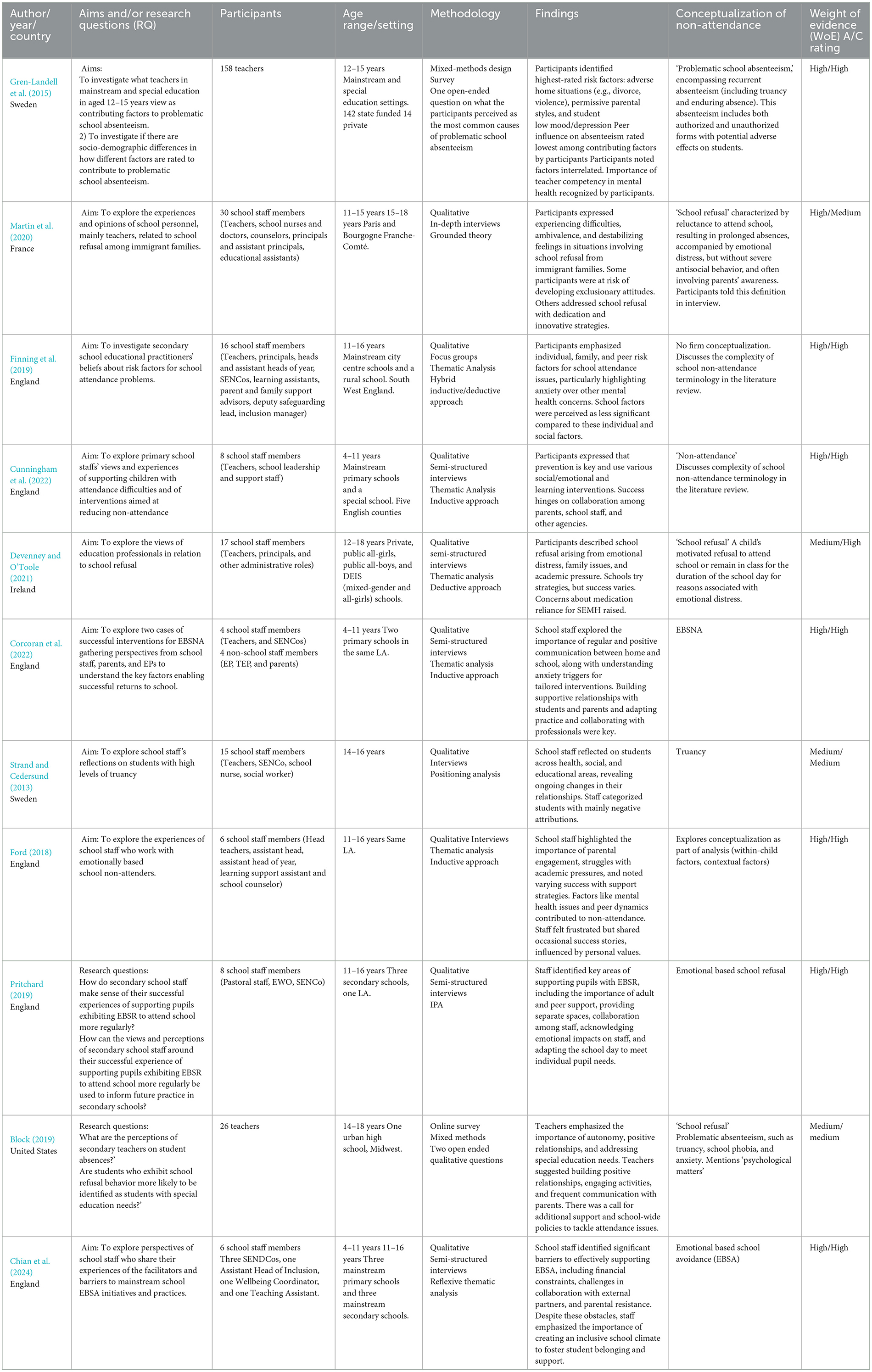

The included papers were published between 2013 and 2024. Six were based in England and two in Sweden, with one study each from the USA, France and Ireland (see Table 2).

While most studies did not report detailed demographic data, several provided information relevant to participant gender or school SES. For example, Chian et al. (2024) included six school staff members (five female, one male) working in primary and secondary mainstream schools, with some schools serving boroughs with significant social and emotional mental health (SEMH) needs. Cunningham et al. (2022) reported on eight participants across seven schools with varied attendance profiles and socioeconomic contexts; some schools were situated in urban areas with below-average attendance, suggesting links to socioeconomic disadvantage. In Devenney and O'Toole's (2021) study, the final sample included 17 professionals (eight male, nine female) working across various Irish secondary schools, including those participating in the Delivering Equality of Opportunity In Schools (DEIS) scheme, a government initiative targeting low socioeconomic status schools. Such details are important for understanding the contexts in which school staff perspectives are formed and applied.

Thematic synthesis followed the three-stage process outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008). In the first stage, line-by-line inductive coding was conducted on the findings and discussion sections of each included study, generating 112 initial codes. This process involved assigning codes based on meaning and content. The first researcher independently coded each line of text according to its meaning and content. Codes were then structured in a hierarchical “tree form” or as “free” codes in NVivo 12 if they did not fit within the superordinate grouping.

In the second stage, codes were grouped and refined into 16 descriptive themes, which remained close to the original data and summarized patterns across studies. These themes captured shared perspectives or experiences reported by participants or interpreted by study authors. In the third stage, analytical themes were generated by interpreting the descriptive themes at a higher level of abstraction. This involved asking interpretive questions of the data (e.g., “What are the underlying processes or mechanisms at play?”) and identifying patterns of interaction and implication. The five analytical themes represent a conceptual understanding of the processes influencing school attendance and staff responses, moving beyond description to generate novel insights (see Figure 2). Bidirectional arrows in the thematic map reflect the iterative nature of the relationships between organizing themes.

The thematic synthesis and coding were primarily conducted by the first author, who approached the data from a constructivist perspective, acknowledging the active role of the researcher in interpreting meaning. Each stage of the process was discussed with the second author. The coding process included regular meetings to review code structures and emergent themes. Consensus on theme development was achieved through reflexive discussion with the second author offering oversight on theme development and interpretation (see Thomas and Harden, 2008). Disagreements or uncertainties were resolved through discussion, revisiting source data, and checking for consistency with the inclusion criteria and the wider literature.

Each analytical theme and its descriptive themes will be presented in turn.

Within child contributors

Anxiety and mental health

The mental health of children was referenced as a contributing factor to student non-attendance in all but one of the studies reviewed. Gren-Landell et al. (2015) highlighted that school staff view mental health difficulties, particularly anxiety and depression, as prominent factors linked to school non-attendance. Similarly, Finning et al. (2019, p. 20) identified anxiety as a leading cause of non-attendance, noting: “it starts with a simple panic attack at school and then it escalates until it's full-blown school anxiety.” Ford (2018) echoed these findings, with school staff referencing that children's anxiety can feel somewhat fixed. One teacher explained: “it can be difficult to kind of get them [children] to change their mindset and see things from a different point of view” (Ford, 2018, p. 102).

Special educational needs

School staff perceived that children with special educational needs (SEN) are particularly vulnerable to non-attendance. Across this studies, SEN was characterized by neurodevelopmental needs, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Devenney and O'Toole, 2021) and physical health needs (Finning et al., 2019). Many school staff perceived that the standard curriculum is ill-equipped to cater for students with such needs (Finning et al., 2019; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2022) increasing the risk of non-attendance and helplessness from school staff: “no matter how hard you try, school is just not the right place for them [children with SEN], they need something different” (Finning et al., 2019, p. 20).

Home environmental contributors

Parenting styles and attitudes

Across the studies, school staff often perceived that parenting styles play a critical role in influencing student attendance. Gren-Landell et al. (2015) found that inconsistent or permissive parenting can contribute to patterns of absenteeism, while Ford (2018) observed that children from homes lacking structure or clear expectations are more likely to miss school. One teacher explained: “sometimes it comes down to, like, parenting, people not being, like, strict enough and getting them in” (Ford, 2018, p. 105). School staff perceiving a negative parental view toward education influencing non-attendance was present across four studies under review (Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Ford, 2018; Finning et al., 2019; Cunningham et al., 2022). This was frequently viewed as barrier to school supporting children finding it challenging to attend school: “the parents aren't backing us, they might say that they are while on the phone but they're not backing us up” (Finning et al., 2019, p. 21). This finding was echoed by teachers in Cunningham, Cunningham et al. (2022) study struggling to engage parents who were perceived to not value school attendance.

Attachment and trauma

Attachment needs and traumatic experiences were perceived as significant contributors to student non-attendance. School staff note that children exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as family separation and violence often struggle with attachment-related anxieties, making it difficult for them to attend school regularly (Strand and Cedersund, 2013; Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Ford, 2018; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). The absence of secure attachments and the presence of unresolved trauma are seen as key factors in school non-attendance by many school staff across the studies under review (Strand and Cedersund, 2013; Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021).

Parental mental health

School staff frequently recognized parental mental health as a significant factor contributing to student non-attendance (Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Ford, 2018; Cunningham et al., 2022; Chian et al., 2024) They observed that children with parents experiencing mental health challenges often feel compelled to stay home to protect or care for their parents. For example, one staff member noted that a student “feels like she has to look after [her mother] and things like that” due to the mother's mental health challenges (Ford, 2018, p. 106). Similarly, it was noted that children may refuse to separate from their parents because of excessive worry about their health (Chian et al., 2024). Additionally, teachers viewed low parental mood and depression as significant contributors to absenteeism (Gren-Landell et al., 2015).

School environmental contributors

Academic performance pressures

The pressures placed on children to perform well academically by schools was referenced as a key contributor to school non-attendance by over half of the papers under review (Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Ford, 2018; Block, 2019; Finning et al., 2019; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2022). School staff highlighted that performance and exam success can create intense stress, particularly during critical periods like the GCSEs. For instance, one practitioner highlighted that “the pressure on achievement in the older years can be massive,” especially when combined with other life stressors' (Finning et al., 2019, p. 22). Teachers observe that this pressure often leads to student burnout, self-harm, and anxiety, which were directly linked to absenteeism (Gren-Landell et al., 2015). Some staff expressed frustration at the intense focus on academic results, noting that it can overshadow students' emotional wellbeing, leaving children who struggle academically feeling less valued (Ford, 2018).

Peer rejection

School staff frequently identify peer rejection and conflict as significant contributors to attendance difficulties. Negative peer relationships, including bullying and social exclusion, were viewed as creating a hostile school environment (Cunningham et al., 2022; Ford, 2018). Staff noted that even minor incidents, such as name-calling, can lead to severe attendance issues, particularly for students who dwell on these negative interactions (Finning et al., 2019). Non-attenders were often perceived as “lonely” or “isolated” which contributed to their reluctance to engage with the school environment (Cunningham et al., 2022). Additionally, school staff often felt that children who felt excluded or bullied were more likely to experience a diminished sense of belonging (Ford, 2018).

Unsuitable curriculum

School staff frequently viewed their respective national curriculums as a significant factor contributing to student non-attendance due to its lack of engagement and suitability for all students, particularly those with SEN (Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Block, 2019; Finning et al., 2019; Cunningham et al., 2022). For example, one group of practitioners highlighted that offering more vocational subjects and a curriculum tailored to individual needs could improve attendance, but noted that many schools are unable to do so due to cost and pressure constraints (Finning et al., 2019). Similarly, teachers observed that when education is not adapted to address students' learning difficulties, it can lead to disengagement and avoidance behaviors (Gren-Landell et al., 2015). Children who were uninterested in the material being taught or who found it irrelevant are often seen as “unwilling to engage” which was perceived to further contribute to their attendance difficulties (Block, 2019; Cunningham et al., 2022).

Educational transition stages

School staff across three studies viewed transitions, particularly the move from primary to secondary school, as significant contributors to student non-attendance (Ford, 2018; Finning et al., 2019; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). Staff also noted that the transition from having one teacher to managing multiple teachers and navigating a larger school environment can be “mind blowing” for some students (Finning et al., 2019, p. 22). This major change can trigger anxiety, as students struggle with new routines, a different school culture, and the pressures of a more exam-driven environment (Ford, 2018; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2022).

Impacts on schools and staff

Emotional stress

Emotional stress for school staff manifested as feelings of frustration, helplessness, and emotional exhaustion when supporting children with attendance difficulties (Ford, 2018; Cunningham et al., 2022). Some staff described the work as an “emotional drain”, particularly when students miss carefully planned lessons, leading to increased workload and pressure to catch up on assessments and having difficult conversations with “irate parents” (Cunningham et al., 2022, p. 73). Additionally, staff often feel a deep sense of responsibility and “genuine concern” for the academic progress of non-attending students, which adds to their stress, especially when curriculum demands are not met (Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). These challenges can evoke a parental-like worry for the students' wellbeing, heightening the emotional burden (Ford, 2018).

Strain on resources

Non-attendance was mostly characterized as “resource drainer” across the studies (Ford, 2018; Cunningham et al., 2022; Chian et al., 2024). Financial constraints exacerbate these challenges, leading to staffing shortages and limiting the ability to provide necessary support, such as adequate teaching assistant (TA) coverage (Chian et al., 2024). Teachers also faced increased workloads and time pressures, feeling the burden of catching up on missed curriculum and managing the complex needs of these students without sufficient external support (Ford, 2018).

Academic outcomes

School staff recognized that student non-attendance can have significant negative effects on academic outcomes for schools (Ford, 2018; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2022). School staff felt that non-attendance directly impacts the number of students meeting “age-related expectations” and diminishes overall progress figures, which are crucial for school performance inspections (Cunningham et al., 2022). The emphasis on data and targets exacerbated this issue, as school staff felt they are evaluated on attendance and academic performance, leading to a focus on numbers rather than student wellbeing (Ford, 2018).

Role ambiguity and lack of agency

School staff often experienced role ambiguity and a lack of agency in addressing student non-attendance, leading to frustration and feelings of helplessness (Ford, 2018; Finning et al., 2019). Educators struggle to define their responsibilities, questioning whether they should act as “care providers” or focus solely on education, which creates uncertainty in handling complex issues like mental health (Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). This lack of clarity and the pressure of limited resources leave many feeling disempowered, with some staff acknowledging that they must “leave it to the professionals” due to feeling unable to influence emotional outcomes positively (Ford, 2018; Finning et al., 2019).

Supportive and protective practice

Relationships with school staff

Five studies consistently highlight that school staff believe that when children feel connected to and cared for by teachers, attendance difficulties reduce (Ford, 2018; Block, 2019; Pritchard, 2019; Corcoran et al., 2022). Teachers and staff who invest time in rapport-building activities, such as shared classroom tasks, create a sense of belonging and trust, which was perceived as central to consistent attendance (Corcoran et al., 2022). Additionally, staff who maintained consistent, supportive contact, even outside the classroom, built strong, trusting relationships that encouraged children's willingness to attend school (Strand and Cedersund, 2013). School staff often felt that this approach fosters a supportive environment where children felt valued and understood, enhancing their engagement with school (Ford, 2018; Pritchard, 2019).

Shared understanding

A shared understanding between home and school, as well as among school staff, was crucial in effectively supporting students with attendance difficulties (Pritchard, 2019; Corcoran et al., 2022; Cunningham et al., 2022). This was felt to enable school staff and parents to identify and address difficulties, leading to earlier and more effective interventions and environmental adjustments (Corcoran et al., 2022). Consistent communication with parents, such as daily contact, was noted to be help ensure an aligned approach, preventing problems from escalating (Pritchard, 2019). Within schools, knowledge about families and sensitive communication among staff members were key to choosing appropriate strategies and ensuring a unified response to each child's needs (Cunningham et al., 2022).

Adapting to support emotional needs

Adapting to support children's emotional needs was seen as central to protecting against attendance difficulties (Pritchard, 2019; Corcoran et al., 2022; Cunningham et al., 2022). School staff felt that when schools were able to work flexibly, tailoring their practices and expectations to meet individual needs, attendance difficulties were ameliorated (Corcoran et al., 2022; Cunningham et al., 2022). This included adjusting the school day, providing personalized timetables, and offering additional academic support, such as slowing down work or using scaffolds to reduce anxiety (Corcoran et al., 2022; Cunningham et al., 2022). Emotional support was also key, with staff maintaining a calm and positive approach, helping students articulate their feelings, and reframing challenges to reduce their anxiety (Pritchard, 2019).

Discussion

This review examined school staffs' perspectives of student non-attendance. There were varied terminology and conceptual models used to describe school non-attendance by researchers, such as EBSA and “school refusal”. This appeared to influence how school staff and practitioners describe and interpret non-attendance, often then driving the nature of support offered or deemed appropriate, based on those interpretations. The findings also underscore the complex interplay of within-child and systemic factors impacting attendance and highlight how these are perceived by school staff.

How is school non-attendance conceptualized across research exploring school staff views?

In line with existing literature, varied terminologies, such as EBSA, school refusal, and chronic non-attendance were used by researchers in framing studies and gathering participants' views, reflecting subtle conceptual differences in understanding attendance difficulties (Kearney et al., 2019). For example, in Gren-Landell et al. (2015) the term “problematic school absenteeism” is presented to participants, and school staff identified factors such as adverse home environments, including permissive parenting styles and exposure to family conflict or violence, as primary contributors. Conversely, the concept of “EBSA” in studies by Corcoran et al. (2022) and Chian et al. (2024) situated non-attendance as emotionally driven, and staff described within child and environmental factors. Staff in these studies emphasized the importance of building supportive relationships, understanding triggers, and adapting school routines to ease students' anxieties. This framing correlated with staff describing close collaboration with families and external professionals, working collectively to create an environment that fosters belonging and reduces stress. Furthermore, “emotionally based” conceptualisations appeared to facilitate staff describing students' non-attendance as intrinsically aligned with anxiety (Ford, 2018). This led to therapeutic approaches being described as a core facet of addressing student non-attendance (Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). When no firm non-attendance conceptualization was established in the rationale of the studies under review, school staff still viewed non-attendance as a complex, eco-systemic issue, aligning with existing research (Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Kearney et al., 2019). While it remains unclear how much of the researcher's conceptualisations of non-attendance were shared with participants, increased reflexivity about non-attendance terminology is needed (Havik and Ingul, 2021): this review has found the theoretical positioning of school non-attendance by researchers is likely to influence how other professionals and school staff interpret the causes of student non-attendance, and therefore, how they may respond to them.

To what extent does the current research on school staff views of non-attendance reflect the multidimensional nature of the issue?

The increased focus on school attendance issues in England is illustrated by Department for Education (2023) data, which highlights a significant rise in persistent non-attendance rates, from 10.9% before the COVID-19 pandemic to over 21% in 2022/23. For students with special educational needs, the rate is even more pronounced, with 36.6% reported as persistently absent in the same period. These statistics suggest a need to address attendance issues across diverse student populations, particularly those with additional needs, who may be at heightened risk for negative long-term outcomes associated with attendance difficulties (Sonuga-Barke and Fearon, 2021). Current attendance monitoring systems, however, often fail to capture the underlying reasons for non-attendance, underscoring the importance of qualitative, school-based perspectives that offer valuable insights into the complex, varied factors influencing student attendance (Corcoran et al., 2024; Sawyer and Collingwood, 2024).

Within-child factors, particularly anxiety and mental health difficulties, were consistently identified by staff as critical barriers to school attendance, an enduring trend reflected in existing literature (Kearney and Albano, 2004; Lereya et al., 2019). School staff frequently describe attendance difficulties as originating in episodes of panic or prolonged anxiety, an interpretation that resonates with findings from Havik and Ingul (2021), who discuss the relationship between anxiety-related avoidance and prolonged absenteeism. Additionally, special educational needs were seen by staff as intensifying attendance difficulties. SEN students often face academic environments that lack the necessary accommodations (Nnamani and Lomer, 2024), for example curricula which fail to account for neurodevelopmental needs exacerbating disengagement (Azpitarte and Holt, 2024). This review also reveals school staffs' frustrations with limited resources and curriculum rigidity, which they felt can restrict their ability to adapt classroom environments to fully support students with additional needs.

The role of family environment in influencing attendance is also a well-established theme in the literature (Kearney, 2008). Staff frequently attribute non-attendance to permissive or unstructured home environments, suggesting that a lack of routine or support for school routines can destabilize students' commitment to school. Within the wider literature, school staff often perceive home-life as a primary driver of challenging student behavior (Carroll et al., 2023). The findings of this review offer some challenge to this assertion: while some school staff emphasized factors external to school (e.g., Gren-Landell et al., 2015), others gave a more eco-systemic conceptualization of school non-attendance, despite initial focus on home-life factors (e.g., Ford, 2018). This divergence may reflect differences in teacher attributions, as highlighted in the broader literature on educator perceptions. For instance, Weiner's (1985) attribution theory suggests that teachers may frame challenges like non-attendance based on perceived controllability and locus of causality. Educators who attribute non-attendance to external factors, such as home-life challenges, may perceive these issues as beyond their control, leading to less focus on school-based interventions. Conversely, those adopting an eco-systemic view may be influenced by growing awareness of the interplay between systemic and individual factors, as suggested by Havik and Ingul (2021) prompting them to consider broader contextual influences. Increasingly, school staff share many of the frustrations about the school environment itself reflected by parents and families (Lissack and Boyle, 2022). This positions parent-school partnerships as crucial for supporting children and young people experiencing attendance difficulties, as effective collaboration would seem to be a key factor in bridging the gap between home and school expectations (Corcoran et al., 2022).

Among school-based factors, academic pressures were cited as significant contributors to student absenteeism by school staff, echoing findings that link the pursuit of high-stakes academic performance with increased student stress (Pascoe et al., 2020). Staff frequently observed that students become overwhelmed by testing pressures, leading to avoidance behaviors that escalate into consistent absenteeism. This aligns with Gulliford's (2015) assertion that secondary students, in particular, face heightened risks of school refusal linked to examination-related stress, which can ultimately impact their overall health and wellbeing. The curriculums school staff were working within were noted as attendance to particularly for students with SEN or those who struggled with traditional academic content. This review reveals that staff often see the curriculum as misaligned with the diverse needs of their students, a challenge previously identified by Liasidou (2012) who argues that curriculum diversification, including vocational and experiential learning opportunities, can enhance engagement. Staff perceive that rigid curricular structures exclude some students, reinforcing the importance of more adaptable educational pathways to improve attendance.

Peer rejection and social isolation were also highlighted as attendance barriers, with staff noting that bullying or lack of social belonging often pushes students away from the school environment. Korpershoek et al.'s (2020) meta-analytic review underscores the role of positive peer and adult relationships and school belonging in reducing attendance difficulties. The participants in the studies reviewed here spoke about the power of taking a relational approach with students. Building positive relationships with families is also referenced across the literature as important in providing useful EBSA support (Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014) and building positive relationships with parents and carers assists with identifying the emerging signs of EBSA, which in turn can facilitate early interventions at a school and familial level (Ingul et al., 2019).

The review highlights how supporting non-attenders can take an emotional toll on school staff, manifesting in stress, role ambiguity, and resource strain. Staff reported that non-attendance support often demands a parental-like role, creating confusion around professional boundaries and stretching their emotional capacities, especially when they lack the training to navigate mental health issues. The reported barriers to student support within teacher roles are similar to those found by previous research (Graham et al., 2011; Mazzer and Rickwood, 2015), including excessive workloads, inflexible curriculums and external pressures on student attainment; limited support from school leaders about these pressures were found to further compound the negative effect of these factors on teachers' self-efficacy to support the wellbeing of children at school.

The findings of this review therefore map closely onto the Multi-Dimensional Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MD-MTSS) model proposed by Kearney and Graczyk (2020), particularly at Tier 1 and Tier 2 levels. School staff consistently described practices such as fostering strong relationships, adapting expectations, identifying early signs of distress, and maintaining close home–school communication, which are core features of Tier 1 prevention and engagement. Likewise, targeted responses for students with emerging needs, including individualized timetables, tailored emotional support, and curriculum adaptations, reflect Tier 2 selective interventions aimed at preventing escalation. While many of these practices are consistent with the MD-MTSS model, they were often informal or fragmented, rather than embedded in a formalized multi-tiered system. Few studies explicitly referenced a systemic framework for supporting attendance, suggesting a gap between implicit practice and structured implementation. Embedding MD-MTSS principles more formally in school policy could help strengthen coherence, ensure equity of support, and sustain staff capacity to respond proactively to attendance difficulties.

While this review focuses on school staff perspectives, it is important to consider how these align with student views. Research by Corcoran and Kelly (2023) and Hejl et al. (2024) has synthesized the voices of students experiencing school attendance problems, highlighting feelings of anxiety, social isolation, and a lack of understanding from adults. Students frequently report difficulty articulating their needs and often describe a sense of being pushed without support (e.g., “They just wanted to know why I didn't go to school, but I didn't know why, and I still don't know” Åhslund, 2021). These findings echo concerns raised by school staff in the current review, particularly around relational breakdowns, academic pressure, and insufficient systemic flexibility. However, students have also challenged the deficit-based framing of their experiences (e.g., “refusal”; Corcoran and Kelly, 2023), suggesting a disconnect in how their behaviors are interpreted. This underlines the need for greater co-construction of attendance support and more participatory approaches that include student voices when addressing school attendance difficulties. Future research could explore points of convergence and divergence between staff and student perspectives to support more holistic, context-sensitive interventions.

Limitations

A primary limitation of this systematic literature review lies in the potential lack of representativeness in the perspectives of school staff included across the studies. Many studies rely on voluntary or convenience sampling, meaning that the views represented may be skewed toward staff members who are more invested in or have specific views on school non-attendance. This selection bias could exclude the perspectives of staff less directly involved in attendance difficulties or those in roles with less direct student contact, such as administrative staff, which may limit the scope of insights gathered.

Another limitation is that the professional roles of school staff participants vary considerably across studies, from teachers and teaching assistants to school leaders and special educational needs coordinators (SENCos). Each of these roles entails distinct responsibilities, influencing how attendance issues are perceived and addressed. For instance, pastoral staff may emphasize relational and emotional aspects of attendance, whereas administrative staff may focus on procedural issues. These role-specific perspectives may affect the types of themes identified in the literature, as individual studies may not account for the full spectrum of staff experiences. Furthermore, most studies focus on secondary school staff, limiting the possible transferability of findings to other school contexts. As attendance-related challenges may manifest differently at various educational stages, particularly with younger children, this emphasis on secondary settings may not capture the nuances relevant to primary school staff. Future research should therefore include a more balanced representation across different educational stages to better understand age-specific challenges and strategies in managing school non-attendance.

Furthermore, many studies include participants from particular regions, which could further limit the transferability of findings to geographical contexts. For example, research conducted in urban schools may capture different challenges and resources than studies in rural settings, which may influence staff perspectives on attendance difficulties. Future research should aim for a diverse sampling of school contexts to better capture how regional, demographic, and cultural factors might influence staff views on non-attendance.

In addition to the limitations of the included studies, several methodological considerations relate to the systematic review process itself. While the search strategy aimed to be comprehensive, it is possible that relevant studies were missed due to the exclusion of gray literature or variations in terminology that limited retrieval (e.g., alternative framings of non-attendance not captured by core search terms). The screening and selection of studies were primarily undertaken by the first author, with consultation from the second author. This may introduce a risk of subjectivity in study inclusion and theme generation. Additionally, due to the qualitative nature of the synthesis, the interpretive construction of themes reflects the reviewers' perspective and may be shaped by their positionality and professional background. While efforts were made to ensure rigor and reflexivity, these limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the review's findings.

Conclusion

Given the complex, multi-layered influences on attendance, the review findings emphasize that eco-systemic, multi-level approaches are essential in understanding and responding to non-attendance. Existing research advocates for systemic frameworks that consider the child's entire environment—home, school, and broader community—to address root causes of non-attendance effectively (Elliott and Place, 2019). Staff descriptions of attendance barriers support this approach, suggesting that strategies such as family engagement, adaptive curricula, and supportive relationships between adults and peers alike are crucial for safeguarding against attendance difficulties. Furthermore, how school staff describe non-attendance, reveals insights into the challenges they encounter when trying to support students with attendance issues. Studies by Prosser and Birchwood (2024) and Ward and Kelly (2024) suggest that school staff often face barriers in implementing effective support for non-attendance. These barriers include systemic challenges such as resource constraints, the need for leadership support, and the complexities of aligning school practices with family and community expectations. The importance of a collaborative, multi-systemic approach has been highlighted by this review, indicating that non-attendance is best addressed through ongoing dialogue among school staff, families, and the students themselves, ensuring that interventions are both effective and respectful of individual needs (Boaler et al., 2024; Sawyer and Collingwood, 2024).

This review also illustrates the significant role that researcher conceptualizations seem to play in shaping how participants interpret and respond to non-attendance. Varied terminologies appear to influence a focus on specific factors, with open-definitions devoid of deficit focused language prompting a more eco-systemic understanding. Similarly, the conceptualizations used by professionals working with attendance issues, such as educational psychologists or external agencies, are likely to shape how school staff and parents perceive and address non-attendance. For example, deficit-focused language, such as such as “school refusal” or “persistent absentee” may reinforce within-child attributions, leading to interventions targeting the individual rather than the broader system. Conversely, eco-systemic or strengths-based terminology “school attendance barriers” or “supporting school attendance” can encourage collaborative, multi-agency approaches that consider environmental and relational factors, potentially resulting in more effective, context-sensitive strategies to mitigate attendance issues (Havik and Ingul, 2021). The findings provide support from a school staff perspective for an integrated model of non-attendance, one that combines therapeutic responses with school-level adaptations, family engagement, and child-centered strategies to create a supportive environment conducive to attendance.

Addressing the complex needs of non-attenders also requires consideration of staff wellbeing, as the emotional toll of supporting high-need students impacts their wellbeing, Clearer role definitions, mental health and wellbeing training, and external support would enable staff to manage attendance-related challenges with more agency. As attendance challenges increase globally, emphasizing both student-centered and staff-supportive strategies may promote more sustainable improvements, ultimately fostering a school culture where both students and educators feel valued and supported.

Overall, the review aligns with existing literature suggesting that multi-level, ecosystemic approaches to non-attendance are essential in both understanding and addressing school non-attendance.

Author contributions

GA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CK: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was funded through England's Department for Education (DfE) ITEP award 2020-2022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Åhslund, I. (2021). How students with neuropsychiatric disabilities understand their absenteeism. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 8, 2148–2225.

Azpitarte, F., and Holt, L. (2024). Failing children with special educational needs and disabilities in England: new evidence of poor outcomes and a postcode lottery at the local authority level at key stage 1. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 414–437. doi: 10.1002/berj.3930

Block, N. (2019). School refusal behavior: examining teachers' perceptions of school refusal behavior of secondary students. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2838332358

Boaler, R., Bond, C., and Knox, L. (2024). The collaborative development of a local authority emotionally based school non-attendance (EBSNA) early identification tool. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 40, 185–200. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2023.2300027

Boaler, R., and Bond, C. (2023). Systemic school-based approaches for supporting students with attendance difficulties: a systematic literature review. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 39, 439–456. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2023.2233084

Bond, C., Kelly, C., Atkinson, C., and Gulliford, A. (2024a). School non-attendance. Educ. Child Psychol. 41, 5–8. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2024.41.1.5

Bond, C., Munford, L., Birks, D., Shobande, O., Denny, S., Hatton-Corcoran, S., et al. (2024b). A Country that Works for all Children and Young People: An Evidence-Based Plan for Improving School Attendance.

Carroll, M., Baulier, K., Cooper, C., Bettini, E., and Greif Green, J. (2023). U.S. middle and high school teacher attributions of externalizing student behavior. Behav. Disord. 48, 243–254. doi: 10.1177/01987429231160705

Chian, J., Holliman, A., Pinto, C., and Waldeck, D. (2024). Emotional based school avoidance: Exploring school staff and pupil perspectives on provision in mainstream schools. Educ. Child Psychol. 41, 55–72. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2024.41.1.55

Corcoran, S., Bond, C., and Knox, L. (2022). Emotionally based school non-attendance: two successful returns to school following lockdown. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 38, 75–88. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2022.2033958

Corcoran, S., and Kelly, C. (2023). A meta-ethnographic understanding of children and young people's experiences of extended school non-attendance. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 23, 24–37. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12577

Corcoran, S., Kelly, C., Bond, C., and Knox, L. (2024). Emotionally based school non-attendance: Development of a local authority, multi-agency approach to supporting regular attendance. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 51, 98–110. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12497

Cunningham, A., Harvey, K., and Waite, P. (2022). School staffs' experiences of supporting children with school attendance difficulties in primary school: a qualitative study. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 27, 72–87. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2022.2067704

Department for Education (2023). Pupil absence in schools in England, autumn and spring term 2022/23. Available online at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england

Devenney, R., and O'Toole, C. (2021). “What kind of education system are we offering”: the views of education professionals on school refusal. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 10, 27–47. doi: 10.17583/ijep.2021.7304

Elliott, J. G., and Place, M. (2019). Practitioner review: school refusal: developments in conceptualisation and treatment since 2000. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 60, 4–15. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12848

Enderle, C., Kreitz-Sandberg, S., Backlund, Å., Isaksson, J., Fredriksson, U., and Ricking, H. (2024). Secondary school students' perspectives on supports for overcoming school attendance problems: a qualitative case study in Germany. Front. Educ. 9:1405395. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1405395

Finning, K., Waite, P., Harvey, K., Moore, D., Davis, B., and Ford, T. (2019). Secondary school practitioners' beliefs about risk factors for school attendance problems: a qualitative study. Emot. Behav. difficulties J. Assoc. Work. Child. with Emot. Behav. Difficulties 25, 15–28. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2019.1647684

Flemming, K., and Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative evidence synthesis: where are we at? Int. J. Qual. Methods 20, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406921993276

Ford, C. (2018). The experiences of school staff who work with emotionally based school non- attendance: a psycho-social exploration. Available online at: https://repository.essex.ac.uk/22880/

Gough, D., Oliver, S., and Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews, 2nd edn. Psychol. Teach. Rev. 23, 95–96. doi: 10.53841/bpsptr.2017.23.2.95

Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., and Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: teacher views. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 17, 479–496. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2011.580525

Gren-Landell, M., Ekerfelt Allvin, C., Bradley, M., Andersson, M., and Andersson, G. (2015). Teachers' views on risk factors for problematic school absenteeism in Swedish primary school students. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31, 412–423. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2015.1086726

Gulliford, A. (2015). “Coping with life by coping with school? School refusal in young people,” in Educational Psychology, 2nd Edn, eds. T. Cline, A. Gulliford, and S. Birch (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 283–305.

Hamadi, S. E., Furenes, M. I., and Havik, T. (2024). A systematic scoping review on research focusing on professionals' attitudes toward school attendance problems. Educ. Sci. 14:66. doi: 10.3390/educsci14010066H

Havik, T., and Ingul, J. M. (2021). How to understand school refusal. Front. Educ. 6, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.715177

Hejl, C., Fryland, N. E., Hansen, R. B., Nielsen, K., and Thastum, M. (2024). A review and qualitative synthesis of the voices of children, parents, and school staff with regards to youth school attendance problems in the Nordic countries. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2024.2434822

Heyne, D., Gren-Landell, M., Melvin, G., and Gentle-Genitty, C. (2019). Differentiation between school attendance problems: why and how? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 8–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.006

Ingul, J. M., Havik, T., and Heyne, D. (2019). Emerging school refusal: a school-based framework for identifying early signs and risk factors. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 46–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.005

Kearney, C. A. (2008). Helping School Refusing Children and Their Parents: A Guide for School-Based Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195320244.001.0001

Kearney, C. A., and Albano, A. M. (2004). The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: diagnostic aspects. Behav. Modif. 28, 147–161. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259263

Kearney, C. A., Gonzálvez, C., Graczyk, P. A., and Fornander, M. J. (2019). Reconciling contemporary approaches to school attendance and school absenteeism: toward promotion and nimble response, global policy review and implementation, and future adaptability (Part 1). Front. Psychol. 10:2222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02222

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. (2014). A response to intervention model to promote school attendance and decrease school absenteeism. Child Youth Care Forum 43, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9222-1

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. A. (2020). A multidimensional, multi-tiered system of supports model to promote school attendance and address school absenteeism. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 23, 316–337. doi: 10.1007/s10567-020-00317-1

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., and de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students' motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: a meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 35, 641–680. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Lereya, S. T., Patel, M., dos Santos, J. P. G. A., and Deighton, J. (2019). Mental health difficulties, attainment and attendance: a cross-sectional study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 1147–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-01273-6

Liasidou, A. (2012). Inclusive Education, Politics and Policymaking: Contemporary Issues in Education Studies. London: Bloomsbury. doi: 10.5040/9781350934252

Lissack, K., and Boyle, C. (2022). Parent/carer views on support for children's school non-attendance: 'how can they support you when they are the ones who report you?' Rev. Educ. 10:e3372. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3372

Martin, R., Benoit, J. P., Moro, M. R., and Benoit, L. (2020). A qualitative study of misconceptions among school personnel about absenteeism of children from immigrant families. Front. Psychiatry 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00202

Mazzer, K. R., and Rickwood, D. J. (2015). Teachers role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 8, 29–41. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2014.978119

Melvin, G. A., Heyne, D., Gray, K. M., Hastings, R. P., Totsika, V., Tonge, B. J., et al. (2019). The kids and teens at school (KiTeS) framework: an inclusive bioecological systems approach to understanding school absenteeism and school attendance problems. Front. Educ. 4:61. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00061

Nnamani, G., and Lomer, S. (2024). 'What is the problem represented to be' in the educational policies relating to the social inclusion of learners with SEN in mainstream schools in England? J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 24, 1046–1059. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12692

Nuttall, C., and Woods, K. (2013). Effective intervention for school refusal behaviour. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 29, 347–366. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2013.846848

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., and Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 104–112. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823

Pritchard, P. (2019). Supporting pupils exhibiting emotionally based school refusal to attend school more regularly: an Interpretative phenomenological analysis exploring the experiences of secondary school staff (dissertation). University of Nottingham, United kingdomK.

Prosser, R., and Birchwood, J. (2024). A systematic review identifying factors associated with emotionally based school non-attendance in autistic children and young people. Educ. Child Psychol. 41, 31–54. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2024.41.1.31

Sawyer, R., and Collingwood, N. (2024). SPIRAL: parents' experiences of emotionally-based school non-attendance (EBSNA) informing a framework for successful reintegration. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 40, 141–158. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2023.2285457

Sonuga-Barke, E., and Fearon, P. (2021). Do lockdowns scar? Three putative mechanisms through which COVID-19 mitigation policies could cause long-term harm to young people's mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 62, 1375–1378. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13537

Strand, A.-S. M., and Cedersund, E. (2013). School staff's reflections on truant students: a positioning analysis. Pastor. Care Educ. 31, 337–353. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2013.835858

Thomas, J., and Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Ward, S., and Kelly, C. (2024). Exploring the implementation of whole school emotionally based school non-attendance (EBSN) guidance in a secondary school. Educ. Child Psychol. 41, 111–123. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2024.41.1.111

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 92, 548–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

West Sussex Educational Psychology Service (n.d.). Emotionally based school avoidance good practice guidance for schools and support agencies. Available online at: https://schools.westsussex.gov.uk/Pages/Download/c5b4a7c0-81b1-4d5e-a3ae-aa0ebe689b05/PageSectionDocuments

Keywords: school staff perspectives, supporting school attendance, school non-attendance, emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA), attendance intervention, systematic literature review, school wellbeing

Citation: Alaimo G and Kelly C (2025) School staffs' views on student non-attendance: a systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 10:1599065. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1599065

Received: 24 March 2025; Accepted: 20 May 2025;

Published: 13 June 2025.

Edited by:

Carolina Gonzálvez, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Caroline Deltour, University of Liège, BelgiumChiara Enderle, Leipzig University, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Alaimo and Kelly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: George Alaimo, Z2FsYWltb0BsaXZlLmNvLnVr; Catherine Kelly, Y2F0aGVyaW5lLmtlbGx5QG1hbmNoZXN0ZXIuYWMudWs=

George Alaimo

George Alaimo Catherine Kelly

Catherine Kelly