- 1Interdisciplinary Research Laboratory in Didactics, Education, and Training, Higher Normal School, Marrakech, Morocco

- 2Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Marrakech, Morocco

- 3Faculty of Sciences Semlalia, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech, Morocco

College counseling plays a vital role in supporting students’ academic success, mental health, and overall well-being. To date, no research has examined this topic among Moroccan students. This study investigates gendered patterns and needs among 401 Moroccan students accessing the country’s oldest college counseling center, located at the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences. This is a retrospective, quantitative study based on case file data collected from counseling records spanning 2015–2018. Descriptive and comparative analyses were conducted to explore visit patterns among the study participants. Men tend to seek counseling at a later age, primarily for academic-related concerns, whereas women are more likely to pursue non-pedagogical support and to participate in multiple counseling sessions. Furthermore, students’ origin, housing situation, and year of study are associated with differences in their counseling needs. Local students, those residing with family, and first-year students predominantly seek academic support, while non-local students, those living in shared housing, and students in advanced years are more inclined to request non-pedagogical assistance. These findings offer insights into gender disparities in student counseling, enhance the understanding of student support needs, and highlight the role of Morocco’s pioneering college counseling center in promoting students’ well-being. This study also lays the groundwork for future research on broader student populations and evolving counseling approaches.

Introduction

College counseling is a multifaceted service provided by university and college counseling centers to support students in navigating the academic and personal challenges of higher education (Kivlighan et al., 2021). In particular, college counseling centers address both academic challenges, such as major selection, study skills, and academic stress (Bishop, 2016), as well as non-academic issues, such as mental health and overall well-being (Bashir et al., 2023). Specifically, services include direct interventions like therapy, consultation with faculty and staff, and academic support (Bvunzawabaya and Rampe, 2024). They aim to enhance student well-being, foster academic success, and support personal development. Furthermore, research shows that counseling improves retention, graduation rates, academic performance, and student coping skills, highlighting its critical role in addressing the diverse needs of college students and promoting their overall success (Scofield et al., 2017). Additionally, college counseling can prevent dropout by offering support and resources to help students address social, emotional, and academic challenges. Through targeted interventions, counseling assists students with transitioning to college life, managing stress and anxiety, building social connections, and enhancing academic performance (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015). As higher education continues to evolve, particularly with growing attention to student well-being, counseling centers play a crucial role in fostering an inclusive learning environment where students from diverse backgrounds can access the support they need to thrive (Bizuneh, 2022).

In Morocco, educational counseling faces limitations due to an insufficient number of counselors to address student needs (Amini et al., 2023). Mental health services in Morocco remain limited and often stigmatized, with perceptions shaped by the interplay of traditional religious beliefs and Western perspectives, further influencing help-seeking behaviors (Zango-Martín et al., 2022). Gendered roles in Morocco significantly influence how individuals perceive and seek mental health support (Ouazzani et al., 2021). Traditional expectations often encourage women to express emotional distress, while men may face stigma when seeking mental health support, leading to differences in help-seeking behaviors (Mzadi et al., 2022). As a result, these norms shape counseling patterns and perceptions of well-being, as what constitutes “good mental health” is not universally defined (Wren-Lewis and Alexandrova, 2021). In particular, dominant definitions of “good mental health” may reflect Westernized, individualistic perspectives, necessitating a culturally sensitive approach to investigating gendered patterns in Moroccan college counseling (Ouazzani et al., 2021). The issue of university integration and student well-being differs for men and women, as women experience more mental health challenges (Erdmann et al., 2023). Access to counseling services is influenced not only by gender but also by students’ socioeconomic backgrounds, emphasizing the necessity of fostering educational inclusivity (Castleman and Goodman, 2018). Factors such as students’ origin, housing status, and financial constraints can influence their ability to seek support (Castleman and Goodman, 2018). Despite their importance, limited research exists in Morocco examining how gendered, demographic, and contextual factors influence counseling service utilization. This gap is especially noticeable in understanding gendered differences in help-seeking behaviors and how factors such as origin, housing, and academic year shape students’ use of these services.

The Semlalia Faculty of Sciences, located in central Morocco, is one of the country’s largest institutions by student enrollment. It attracts a diverse student body from various socio-economic backgrounds, including both urban and rural areas nationwide. The Semlalia Faculty of Sciences also houses Morocco’s oldest college counseling center. Given its diverse student body and long-standing counseling services, it serves as an ideal setting to examine how gender, socioeconomic factors, and student needs interact within the broader framework of educational inclusivity and mental health support in higher education. This study aims to investigate the demographic patterns and the nature of needs of students at the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences counseling center. Furthermore, it seeks to explore gendered trends in the utilization of counseling services. Research questions are:

• What are the gendered differences in counseling service utilization?

• What are the factors associated with the use of the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences counseling center?

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This quantitative retrospective study was conducted at the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences in Morocco, focusing on beneficiaries of the College Counseling Center between 2015 and 2018, based on case file data documenting students’ counseling visits, stated needs, and demographic information. Established in 2009 as Morocco’s first college counseling center, the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences’ center has developed significant experience in addressing both pedagogical and non-pedagogical student needs, though its pioneering status also means it operates with limited staff and resources—factors that may influence patterns of service utilization. Pedagogical support includes academic counseling, time management, exam preparation, university procedures, and career orientation. Non-pedagogical support focuses on mental health issues such as anxiety and emotional distress, as well as financial difficulties, housing concerns, and family-related problems, and the center is staffed by trained professionals. By responding to these diverse needs, the center plays a key role in fostering student retention and holistic development within the university setting.

Participants and sampling

A total of 401 participants were included in the study using a comprehensive and exhaustive sampling approach, in which all college students who received counseling services during the specified timeframe were included.

Data collection

Data were collected using an author-developed checklist including the sociodemographic factors: gender (man or woman), age, origin (local or non-local to the college city), housing (extended family or shared housing), and year of enrollment (first, second, or third year of a three-year program).

In addition to sociodemographic data, we collected variables related to counseling service utilization: counseling need nature (pedagogical or non-pedagogical issues) and visit frequency (single or multiple). The checklist was reviewed by experts for content relevance and clarity, and pilot-tested on a small subsample to ensure consistency and usability.

Missing data were handled using pairwise deletion, allowing each analysis to include all available data for the variables involved. Some entries were incomplete because certain students did not fully complete their intake forms during their visit to the center, leaving specific questions unanswered. Data were collected by the first author between July and August 2022, using records archived for institutional and research purposes. To ensure data quality, only clearly legible and complete information was extracted for analysis.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software v26 (IBM Corp., 2019). Qualitative variables were analyzed using frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were analyzed using mean and standard deviation. Furthermore, comparative analyses using chi-square and t-tests were conducted to identify significant associations between variables. For all statistical analyses, the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

A post hoc statistical power analysis was conducted using the G*power software (Faul et al., 2007). with an α = 0.05, a minimum of 149 participants would be sufficient to detect a medium effect size (w = 0.3) in chi-square an t-tests with 1 degree of freedom to achieve a statistical power of 95%. Given that our actual sample (N = 401) exceeds this threshold substantially, the study is adequately powered to detect medium-to-small effects and supports the robustness of the statistical analyses performed.

Ethical considerations

Institutional approval was obtained, and although formal ethical approval was not required under local regulations, strict confidentiality measures were upheld. No identifying information, such as names or specific geographic details, was included in the dataset. To ensure confidentiality, the counseling records were anonymized by center staff, and only the first author had access to the anonymized archive, which was stored on a secure, password-protected computer.

Results

Population characteristics

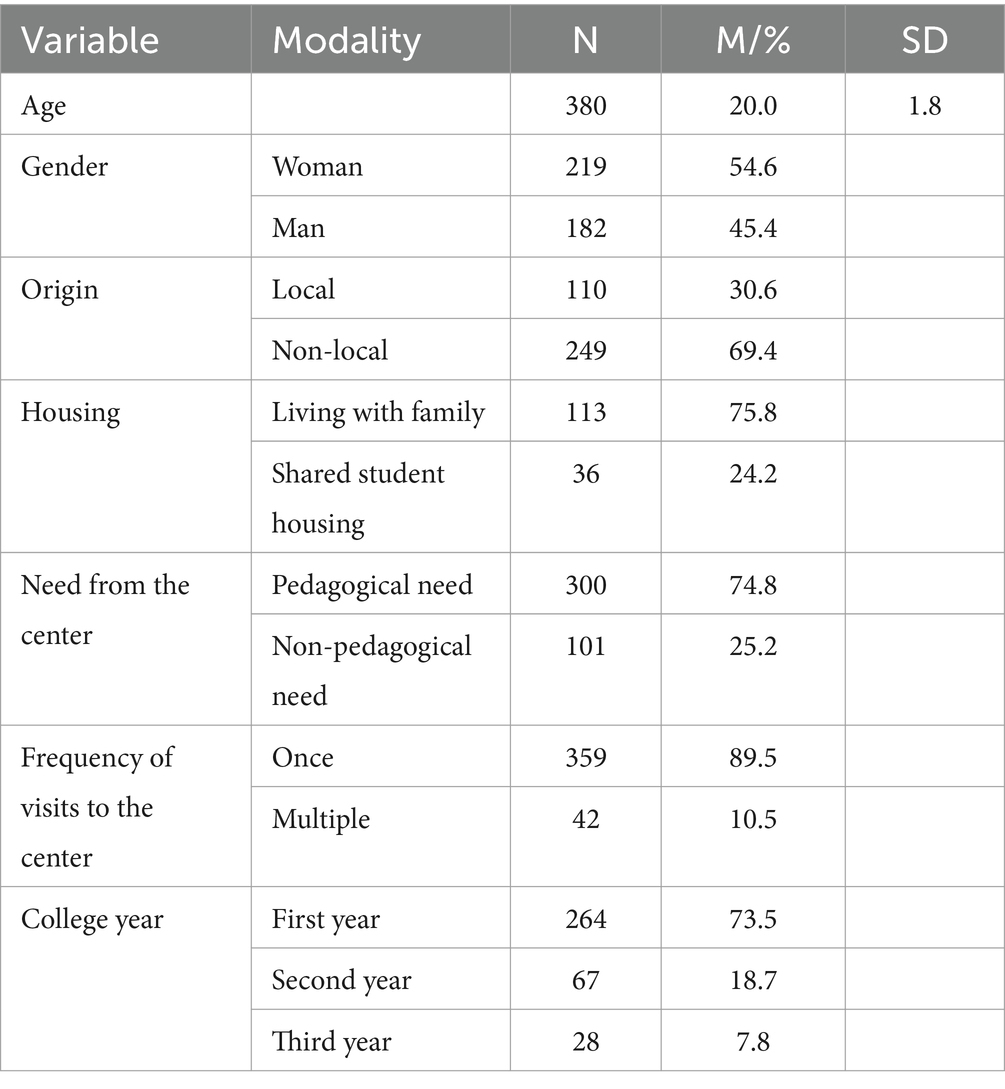

Table 1 presents the descriptive data of the population:

The study included 401 participants, with a gender distribution slightly favoring women (54.6%) over men (45.4%). The average age was 20 years (SD = 1.8), ranging from 17 to 26. Most participants (69.4%) came from outside the college city. Among 149 participants who reported their housing status, 75.8% lived with family, and 24.2% lived in shared or university housing. The primary counseling need identified was pedagogical (74.8%), with other needs (25.2%) related to mental health, financial, or familial issues. Most participants (89.5%) visited the counseling center once. First-year college students were the majority (73.5%).

Comparative statistics of the study

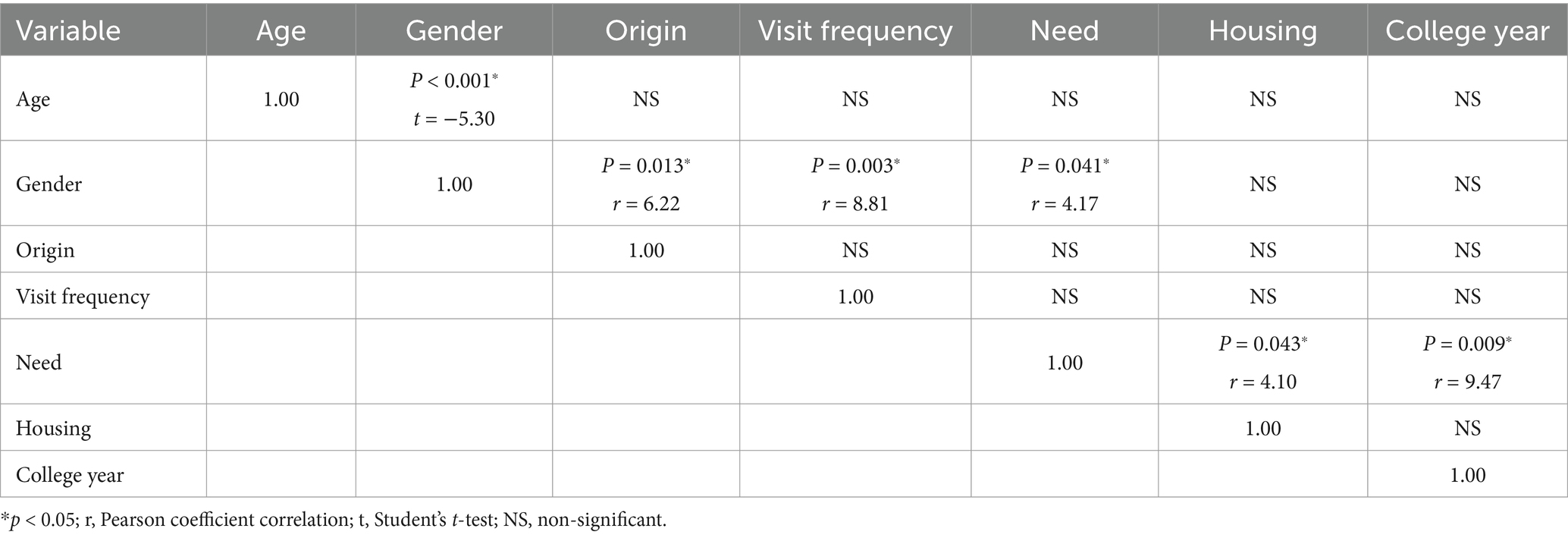

Table 2 presents the comparative statistics of the study.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in mean age between women (20.29 ± 1.6) and men (21.26 ± 1.9), (t = −5.3, Cohen’s d = −0.56, p < 0.001). This suggests that, on average, men tend to visit the counseling center at a slightly older age compared to women.

The study results indicate a statistically significant association between gender and origin (r = 6.22, Cramer’s V = 0.132, p = 0.013). Local women were more likely to visit the counseling center than those originally from outside the college city.

In addition, a statistically significant association between gender and counseling center visit frequency was found (r = 8.81, Cramer’s V = 0.148, p = 0.003). This result suggests that counseling visit frequency differs significantly by gender. Specifically, among women, 32 out of 219 (14.6%) visited the counseling center frequently, whereas only 10 out of 182 men (5.5%) returned multiple times.

Furthermore, a statistically significant association between gender and counseling need nature (pedagogical vs. other) was observed (r = 4.17, Cramer’s V = 0.102, p = 0.041). The study results indicate that 74.8% of participants sought pedagogical support, with a slightly higher proportion of men (145 out of 182, or 79.7%) compared to women (155 out of 219, or 70.8%). Meanwhile, among those presenting non-pedagogical needs, 35.2% were women (64 out of 183), compared to 20.3% of men (37 out of 182).

A statistically significant association between students’ housing arrangements and their type of need (pedagogical vs. other) was found (r = 4.10, Cramer’s V = 0.166, p = 0.043). This suggests that housing type is significantly associated with students’ counseling needs. Among those who presented pedagogical needs, the majority (83 out of 103, or 80.6%) lived with family members, while a smaller portion (20 out of 103, or 19.4%) resided in shared or university housing. Conversely, among students presenting non-pedagogical needs, 65.2% (30 out of 46) lived with family, while 34.8% (16 out of 46) resided in shared or university housing. These results indicate that students living in family housing are more likely to report pedagogical needs, whereas those in shared or university housing show a comparatively higher rate of non-pedagogical needs.

A statistically significant association between college year and type of need was also found (r = 9.47, Cramer’s V = 0.162, p = 0.009), suggesting that the nature of students’ needs varies significantly depending on their academic year. Cross-tabulation results reveal that the majority of first-year students (206 out of 264, or 78%) had pedagogical needs, compared to 58 students (22%) who reported other types of needs. This trend persists in the second year, where 60% of students sought pedagogical support and 40% reported other needs. By the third year, the proportion of students with pedagogical needs decreases further to 71% (20 out of 28), while 29% sought support for other concerns.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the gendered patterns and needs of students utilizing counseling services at Morocco’s oldest college counseling center, housed within the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences. The findings contribute to an understanding of how gender, socio-demographic factors, and educational context shape counseling utilization, emphasizing the importance of inclusive support frameworks in higher education.

Descriptive characteristics of participants

The distribution of gender among the participants was slightly more female (54.6%) than male (45.4%). This pattern aligns with existing literature indicating that women are more likely than men to seek counseling services (Huenergarde, 2018; Awol Amado and Shiferew, 2022; Bashir et al., 2023). This difference may be due to sociocultural influences that shape gendered help-seeking behaviors, as women are often socialized to be more emotionally expressive and to seek help when they are struggling (Irawan et al., 2024). While stigma surrounding mental health impacts both genders, men may face additional stigma for seeking help, as it can be seen as a sign of weakness (Irawan et al., 2024). Moreover, women may be more aware of mental health issues and the benefits of counseling (Huenergarde, 2018). This awareness may be influenced by greater media focus on women’s mental health (Rice et al., 2021), or by personal exposure to friends and colleagues who have sought counseling. Additionally, the presence of female counselors in the study setting counseling center may have influenced the gendered distribution among the participants, as a study found that the predominance of female counselors in the field may make women more comfortable seeking services (Alcée, 2017). This finding underscores the need for interventions that normalize help-seeking behaviors among men and reduce stigma surrounding mental health support.

The average age of participants at the time of their visit to the center was 20 years (SD = 1.80), with ages ranging from 17 to 26. This age range is typical of college students, highlighting that the counseling center serves crucial developmental stage where students are transitioning to greater independence and facing academic, social, and psychological challenges (Avcı, 2024). At this stage, students are also more likely to encounter mental health issues (Hill et al., 2024).

In addition, the university counseling center attracted a higher percentage of students from outside the college city (69.4%) compared to local students (30.6%). Students who are new to a college city may face challenges integrating into the social fabric of the campus and city (Awol Amado and Shiferew, 2022), they may be less likely to have established support systems in place, such as family and friends, which could lead them to seek out the counseling center for social connection and support. Thus, moving away from home and adapting to college life can be particularly stressful for students from outside the college city. They may be more likely to experience homesickness, anxiety, and difficulty adjusting to the academic and social demands of college (Huenergarde, 2018). These challenges could therefore increase their likelihood of seeking support from the counseling center.

Furthermore, a significant majority of students (75.8%) live with extended family or family members compared to 24.2% in shared or student housing. Students living at home may experience stress related to family expectations and responsibilities, which can impact their mental well-being and academic performance (Hallett and Freas, 2018). On the other hand, students in shared housing may experience dissatisfaction with their living arrangements, including conflicts with roommates, poor housing quality, noise levels, and unpleasant or unsafe neighborhoods, all of which can contribute to stress and negatively impact mental well-being. Conversely, satisfaction with one’s living environment can foster good mental health (Deb et al., 2016). These findings emphasize the role of socio-economic factors in shaping students’ experiences and reinforce the necessity of inclusive, context-sensitive counseling interventions.

Regarding the types of needs, the primary need identified by participants was pedagogical support (74.8%), with other types of needs (e.g., financial or mental health-related) constituting 25.2%. Counseling centers often address issues related to academic performance, such as study skills, time management, and test-taking skills (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015), but students also seek counseling for help with relationships, self-esteem, and transitioning to college (Bashir et al., 2023). In fact, mental health challenges among college students have become increasingly prevalent, highlighting the critical role of counseling services in effectively addressing these concerns (Avcı, 2024). Students frequently use counseling services for mental health concerns like anxiety, depression, and stress (Huenergarde, 2018). In response, counseling centers often offer a holistic approach to student support (Meek, 2023; Bvunzawabaya and Rampe, 2024). This finding suggests that counseling centers must adopt a holistic support model that integrates both academic guidance and mental health services to comprehensively address student well-being.

Additionally, only 10.5% of the participants had made multiple visits to the center, indicating that the majority (89.5%) had single-session engagements. Literature shows that the majority of students utilizing university counseling services engage in single-session consultations, while a smaller proportion accounts for more frequent usage (Shefet, 2018). This suggests that students might find resolution for their concerns outside of the counseling center, due to factors like strong social support networks, self-reliance, and the perception that their problems aren’t serious enough for professional intervention.

Finally, a large proportion of the participants were in their first year (73.5%), with fewer in the second (18.7%) and third years (7.8%). First-year college students have a greater need for counseling services compared to students in later years, as first-year students experience significant psychosocial and academic transitions, including adjusting to a new environment, managing increased academic demands, and navigating new social situations (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015). Counseling services can provide support and guidance during this critical period. In particular, the counseling center can facilitate first-year students’ social adjustment in their new environment by providing a space for students to address personal and familial issues (Avcı, 2024). Research suggests that first-year students, particularly those facing numerous problems, may experience greater mental health distress (Wei et al., 2022). This distress, combined with their unfamiliarity with the university environment, might lead them to seek help from the counseling center more readily. In contrast, students in their second and third years might have adapted to the college environment and developed coping strategies, as well as a better understanding of available resources and support systems, potentially leading them to seek help from other sources (Bashir et al., 2023).

Comparative results of participants

The study results suggest that, in general, men tend to visit the counseling center at a slightly older age compared to women. Traditional gendered norms often deter men from seeking counseling, as they may perceive it as a threat to their masculinity or fear stigma from peers, family, or counselors. This societal expectation can leave male college students more vulnerable to mental health issues (Agochukwu and Wittmann, 2019). Such findings are consistent with research indicating that men are generally less inclined to seek help from counseling services, often due to societal or cultural discouragement (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015). Research also suggests gendered differences in counseling needs, with women typically seeking help earlier for mental health issues like depression and anxiety (Welsch and Winden, 2019).

The results indicate a statistically significant association between gender and origin (χ2 = 6.22, p = 0.013). The significant p-value suggests that gender and origin are not independent; local women are more likely to visit the center than women who are originally from outside the college city. Local students may be more familiar with counseling centers due to prior exposure through outreach programs or community events, reducing apprehension. In addition, local women often have stronger social support networks within the college city, encouraging help-seeking behaviors. Established local networks of friends, family, and community provide emotional and practical support, facilitating access to counseling services (Osborn et al., 2022). This highlights the importance of conducting comprehensive local needs assessments and tailoring services to address the specific needs of the local student population (Campion et al., 2022), while also underscoring the need for targeted outreach efforts to ensure equitable access to counseling services for all students, regardless of their background.

In this context, the results suggest that women may be more inclined to seek support for non-pedagogical needs. Meanwhile, their male counterparts predominantly presented pedagogical needs. Men are more likely to present pedagogical needs, such as orientation and major selection. This could suggest that they prioritize academic success and view seeking help in this domain as more acceptable or necessary than seeking help for personal issues (Bashir et al., 2023). Men may avoid counseling when it involves disclosing vulnerabilities or perceived weaknesses due to the stigma (Alcée, 2017; Irawan et al., 2024). For example, disclosing personal struggles, like financial or family issues, could lead to feelings of shame and embarrassment, further discouraging them from seeking help (Hallett and Freas, 2018), while counseling can also assist students in choosing their college major (Erdmann et al., 2023).

Moreover, the results indicate that students living in family housing are more likely to report pedagogical needs than those in shared or university housing, who have a comparatively higher rate of non-pedagogical needs. Students living in family housing may benefit from greater family support, which could alleviate non-pedagogical needs related to finances, mental health, and family issues. In contrast, financial instability and housing insecurity can be significant stressors for students (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015), potentially contributing to a higher prevalence of non-pedagogical needs among those not living in family housing.

The results indicate that pedagogical needs are especially prominent in the first year, possibly due to new students seeking orientation, academic support, and guidance. However, as students’ progress through their college years, there is a slight increase in the diversity of their needs, with a growing proportion reporting non-pedagogical issues. First-year students often face challenges adapting to the college environment, including adjusting to rigorous coursework, new teaching methods, and increased responsibility (Wei et al., 2022). As students’ progress through college, their challenges and stressors often evolve, leading to changing support needs. For instance, financial difficulties, housing insecurity, health concerns, or family issues may arise later in their academic journey, significantly impacting their well-being and prompting a greater demand for non-pedagogical support (Deb et al., 2016).

The findings of this study suggest several key recommendations to enhance the effectiveness of the counseling center. The higher engagement of women, particularly in seeking non-pedagogical support, underscores the need for gender-sensitive interventions, such as stigma reduction initiatives for men and expanded well-being support tailored to women’ needs. Additionally, the greater utilization of services by local students suggests that nonlocal students may face logistical or awareness barriers, highlighting the importance of targeted outreach programs and improved accessibility measures. Housing differences further reveal distinct patterns, with students in family housing primarily requiring academic support, while those in shared housing predominantly seek non-pedagogical assistance. Tailoring services to these needs could optimize counseling effectiveness. In a complex world, the education field must embrace innovative learning challenges that drive the creation of disruptive, differentiated proposals to address the unique needs of students. This work presents a tool that identifies and categorizes distinct elements in the university system, aiming to build new educational solutions that meet diverse student needs and future challenges. However, these innovations must be implemented with careful attention to ethical concerns, such as data privacy.

The perspectives of this study highlight the need for broader research on counseling services in Morocco. A key limitation of this study is its focus on a single university counseling center, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Caution is therefore advised in extrapolating the results to other Moroccan universities, especially given potential shifts in student needs in the post-pandemic context since the 2015–2018 data collection period. We acknowledge the limitation that cross-checking was omitted due to confidentiality constraints. Future research should pursue comparative, multi-site studies—including rural and private institutions—to capture a broader range of student needs and institutional responses. Mixed-method approaches, such as surveys and interviews, could offer deeper insight into student experiences. Studies should also examine the impact of counseling on academic performance and mental health, and develop targeted interventions to reduce stigma, particularly among male and out-of-town students. Finally, research across multiple institutions is needed to determine whether the gendered counseling patterns and needs observed at the Semlalia Faculty of Sciences are indicative of national trends.

Conclusion

This pioneering study of Morocco’s oldest college counseling center reveals significant gendered differences in counseling service usage. Men tend to seek support at an older age, primarily for academic concerns, while women are more likely to seek non-pedagogical support, particularly for mental health, and attend multiple sessions. Additionally, factors such as origin, housing, and academic year shape counseling needs—local students, those in family housing, and first-year students predominantly seek academic support, whereas non-local students, those in shared housing, and upper-year students more often seek non-pedagogical assistance. Future research should adopt a multicentric approach with a larger sample to deepen insights into gendered patterns and counseling needs among Moroccan college students. The study recommends integrating predictive analytics to enhance counseling services by anticipating future student needs, offering a foundation for future studies on data-driven approaches to student support.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NE-S: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. KT: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Validation. LR: Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. LO: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MA declared a shared affiliation with the author(s) KT to the handling editor at time of review.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agochukwu, N. Q., and Wittmann, D. (2019). “Chapter 3.2 - stress, depression, mental illness, and men’s health” in Effects of lifestyle on men’s health. eds. F. A. Yafi and N. R. Yafi (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 207–221.

Alcée, M. D. (2017). The importance of a male presence in college counseling. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 31, 180–191. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2017.1283973

Amini, N., Sefri, Y., and Radid, M. (2023). Factors affecting students’ career choices in Morocco. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 12, 337–345. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v12i1.23795

Avcı, D. (2024). First year and adjustment in university life: a qualitative study to determine the needs of first year university students. Educ. Res. Implement. 1, 51–68. doi: 10.14527/edure.2024.04

Awol Amado, A., and Shiferew, B. (2022). Perceived need to counseling service and associated factors among higher education institutions: the case of Dilla University, southern Ethiopia. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2022/7307306

Bashir, S., Khan, M. I., and Mushtaq, A. (2023). Investigation of counseling services at universities: perceived students’ needs. Available online at: http://jies.pk/ojs/index.php/1/article/view/84 (Accessed November 24, 2024).

Bishop, K. K. (2016). The relationship between retention and college counseling for high-risk students. J. Coll. Counsel. 19, 205–217. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12044

Bizuneh, S. (2022). Belief in counseling service effectiveness and academic self-concept as correlates of academic help-seeking behavior among college students. Front. Educ. 7:834748. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.834748

Bvunzawabaya, B., and Rampe, R. (2024). Meeting the university counseling centers demand with outreach competencies. J. Coll. Stud. Mental Health 38, 897–923. doi: 10.1080/28367138.2024.2343487

Campion, J., Javed, A., Lund, C., Sartorius, N., Saxena, S., Marmot, M., et al. (2022). Public mental health: required actions to address implementation failure in the context of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 169–182. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00199-1

Castleman, B., and Goodman, J. (2018). Intensive college counseling and the enrollment and persistence of low-income students. Educ. Finance Policy 13, 19–41. doi: 10.1162/edfp_a_00204

Cholewa, B., and Ramaswami, S. (2015). The effects of counseling on the retention and academic performance of underprepared freshmen. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 17, 204–225. doi: 10.1177/1521025115578233

Deb, S., Banu, P. R., Thomas, S., Vardhan, R. V., Rao, P. T., and Khawaja, N. (2016). Depression among Indian university students and its association with perceived university academic environment, living arrangements and personal issues. Asian J. Psychiatr. 23, 108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.07.010

Erdmann, M., Schneider, J., Pietrzyk, I., Jacob, M., and Helbig, M. (2023). The impact of guidance counselling on gender segregation: major choice and persistence in higher education. An experimental study. Front. Sociol. 8:1154138. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1154138

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Hallett, R. E., and Freas, A. (2018). Community college students’ experiences with homelessness and housing insecurity. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 42, 724–739. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2017.1356764

Hill, M., Farrelly, N., Clarke, C., and Cannon, M. (2024). Student mental health and well-being: overview and future directions. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 41, 259–266. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.110

Huenergarde, M. (2018). College students’ well–being: use of counseling services. Am. J. Undergrad. Res. 15, 41–45. doi: 10.33697/ajur.2018.023

Irawan, A. W., Yulindrasari, H., and Dwisona, D. (2024). Counseling stigma: a gender analysis of mental health access in higher education. Bull. Couns. Psychother. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.51214/00202406837000

Kivlighan, D. M., Schreier, B. A., Gates, C., Hong, J. E., Corkery, J. M., Anderson, C. L., et al. (2021). The role of mental health counseling in college students’ academic success: an interrupted time series analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 68, 562–570. doi: 10.1037/cou0000534

Meek, W. D. (2023). The flexible care model: transformative practices for university counseling centers. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 37, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2021.1888365

Mzadi, A. E., Zouini, B., Kerekes, N., and Senhaji, M. (2022). Mental health profiles in a sample of Moroccan high school students: comparison before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psych. 12:752539. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.752539

Osborn, T. G., Li, S., Saunders, R., and Fonagy, P. (2022). University students’ use of mental health services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s13033-022-00569-0

Ouazzani, S. E., Zanga-Martin, I., and Burgess, R. (2021). “Culture and mental healthcare access in the Moroccan context” in Health communication and disease in Africa. eds. B. Falade and M. Murire (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 249–270.

Rice, S., Oliffe, J., Seidler, Z., Borschmann, R., Pirkis, J., Reavley, N., et al. (2021). Gender norms and the mental health of boys and young men. Lancet Public Health 6, e541–e542. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00138-9

Scofield, B. E., Stauffer, A. L., Locke, B. D., Hayes, J. A., Hung, Y.-C., Nyce, M. L., et al. (2017). The relationship between students’ counseling center contact and long-term educational outcomes. Psychol. Serv. 14, 461–469. doi: 10.1037/ser0000159

Shefet, O. M. (2018). Ultra-brief, immediate, and resurgent: a college counseling paradigm realignment. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 32, 291–311. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2017.1401790

Wei, C., Ma, Y., Ye, J.-H., and Nong, L. (2022). First-year college students’ mental health in the post-COVID-19 era in Guangxi, China: a study demands-resources model perspective. Front. Public Health 10:906788. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.906788

Welsch, D. M., and Winden, M. (2019). Student gender, counselor gender, and college advice. Educ. Econ. 27, 112–131. doi: 10.1080/09645292.2018.1517864

Wren-Lewis, S., and Alexandrova, A. (2021). Mental health without well-being. J. Med. Philos. 46, 684–703. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhab032

Keywords: college counseling, education, counseling need, gendered patterns, future studies, student support

Citation: Es-Sahib N, Takhdat K, Rafouk L and Okhaya L (2025) Exploring gendered patterns and students’ needs at Morocco’s oldest college counseling center: implications for inclusive support services. Front. Educ. 10:1600154. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1600154

Edited by:

Lola Costa Gálvez, Open University of Catalonia, SpainReviewed by:

Ahmed Nafis, Université Chouaib Doukkali, MoroccoMounia Amne, ISPITS-Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques of Marrakech, Morocco

ANIBA Rafik, Sultan Moulay Slimane University, Morocco

Abdelali El Gourari, École marocaine des sciences de l’ingénieur, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Es-Sahib, Takhdat, Rafouk and Okhaya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nabil Es-Sahib, ZXNzYWhpYm5hYmlsMjAxNkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nabil Es-Sahib

Nabil Es-Sahib Kamal Takhdat

Kamal Takhdat Leila Rafouk3

Leila Rafouk3